Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 48

March 11, 2011

Degrees of Fragility

I was all set to end the week with a post about a particularly egregious patent-medicine fraud, but it somehow seems wrong in light of the catastrophe in Japan. We often forget how much our species is at the mercy of the planet, and how quickly everything we treasure can be snatched away. For the moment, I can only take small comfort in the fact that my Japanese friends appear to be present and accounted for.

The silver lining here, though, is that the death toll in Japan would have been much, much worse had the nation not committed long ago to sound engineering. As previously discussed on Microkhan, it is disturbingly easy to predict an earthquake's death toll based on both the magnitude of the tremor and, more important, the quality of the building stock. Scarred by several 19th-century earthquakes that decimated its population, Japan started taking earthquake safety seriously once it attained the requisite level of prosperity to enforce building codes. There is no way to calculate how many thousands of lives were saved today by the bureaucracy ensures that constructions firms don't cut corners, and that private builders are appropriately punished for using sub-standard materials or ill-conceived designs.

One point to reiterate from my earlier earthquake post: A Nobel Prize certainly awaits the man or woman who can come up with a low-cost building material capable of mimicking timber's strength. Japan is prosperous enough to afford materials that can bend and sway when rocked by the Earth; less fortunate nations are stuck with concrete, which is the last thing you want your house to be made of when a mega-tremor strikes.

(Photo from The Great Earthquake of Japan, 1891, via Baxley Stamps)

March 10, 2011

Lost in Translation

Though English may be gaining an ever-greater toehold in the rest of the world, the United States appears to becoming increasingly polyglot. At the same time, first-generation immigrants are making landfall in far-flung locations throughout the U.S., rather than concentrating in a handful of urban centers. Those two trends spell trouble for courts with slim linguistic resources, not to mention non-English-speaking parties who must navigate the justice system.

We must thus expect more situations such as the recent case of Weston Ludrick, a native of Pohnpei who found himself accused of vehicular homicide in Arkansas. Ludrick's primary tongue is Kiti, and he requested a translator who could assist in his defense. The court provided him with a woman who was a certified translator of Marshallese, but appeared to have only a rudimentary familiarity with Kiti. Ludrick used this fact as grounds for appeal:

Mr. Ludrick contends that he was forced to sit in total incomprehension as the trial went on around him. He asserts that his interpreter, Mrs. Joel, had never been an interpreter of Kiti nor had she interpreted in a jury trial. Moreover, Mr. Ludrick points out that on one occasion during the proceedings he gave an indication that he did not understand Mrs. Joel's explanation of the proceedings, and he questions whether Mrs. Joel was interpreting the proceedings word for word as opposed to merely providing summaries or explanations. Mr. Ludrick further asserts that prior to the September 21, 2009, hearing, he was scheduled for a forensic evaluation but refused to speak to the psychiatrist because, as explained through Mrs. Joel, Mr. Ludrick did not think she could interpret well for him because she was born on the Marshall Islands. Finally, Mr. Ludrick contends that subsequent to that hearing Ms. Simmons reconsidered Mrs. Joel's qualifications and believed she was no longer qualified to be a non-certified interpreter. Mr. Ludrick maintains that under these circumstances, the accuracy and scope of the translation during the proceedings were subject to grave doubt and that his due process rights were violated. Due to the trial court's error in failing to make available a qualified and certified interpreter, Mr. Ludrick requests a new trial.

Ludrick lost his appeal because an Arkansas appeals court found that sufficiently diligent efforts had been made to locate a certified translator of Kiti, to no avail. But might this be a situation in which affordable technology could have come to the rescue? Granted, it's going to be hard to find speakers of obscure languages in certain corners of the country where immigrant communities are small. But there is scant effort required these days to set up a video link to a distant locale; it seems Ludrick would have been better off communicating with a competent translator via Skype than being baffled by his court-appointed intermediary.

March 9, 2011

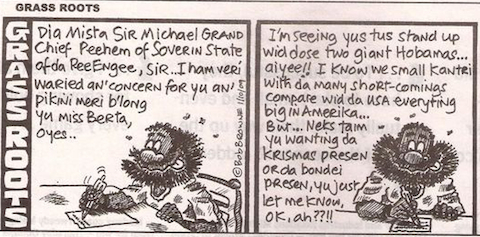

The Garry Trudeau of Papua New Guinea

Sad news out of Port Moresby, as cartoonist Bob Browne has passed on well before his time:

He was the creator of Mr Grass Roots, perhaps Papua New Guinea's most loved comic character, which the magazine Islands Business once called "the social conscience of PNG"…

Roots became the Papua New Guinean Everyman, the knock-about character with a heart of gold, a belly full of beer and a thick skull where his long-suffering wife, Agnes, berated his foolishness with her famous "sospen".

Through Roots – who started as a character called Lu promoting Isuzu trucks – Browne was able to reflect on PNG life through an eerily indigenous perspective and criticise its shortcomings in a gentle but incisive way.

The great strength of cartooning is the ability to take pot-shots at the gross, the venal, the dishonest, the lazy or the plain foolish from behind the protective ramparts of humour. Browne seldom let this advantage descend into bitterness or cruelty, thanks mainly to Grass Roots himself, a man both naive and aware, a hale and hearty innocent wandering through a confused and confusing world. In Australia, Roots would be called "a good bloke", in the US "a good ol' boy", someone you felt drawn to protect even though you'd also harbour the suspicion he was in some mysterious way already ahead of you.

Browne's work was collected in several volumes available Stateside. Don't be frightened by the use of pidgin—the political edge shines through regardless. Samples here and here.

March 8, 2011

The Curtain Drops

Though I frequent Broadway shows about as often as I indulge in White Castle—that is, once in a blue moon—I'll admit to taking undue pleasures in the travails of Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. Not in the various serious injuries that the production has incurred, mind you, but rather in seeing what happens when unchecked egos are permitted access to endless gobs of money. There is something to be said for the usefulness of limits.

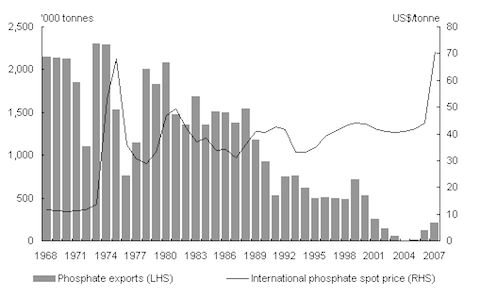

Yet I find myself disagreeing with pundits who've already declared Spider-Man the greatest flop in the history of musical theater. Assuming that things don't pan out for the show, that contention might hold water in terms of the sheer amount of money lost. But as I understand it, the only folks who stand to suffer from Spider-Man's demise are people who won't exactly be relegated to eating Top Ramen as a result. The same cannot be said for the money behind the 1993 mega-flop Leonardo da Vinci: A Portrait of Love, which washed off the London stage in a matter of weeks. That doomed production was backed by a shady operator named Duke Minks, who obtained his $4 million-plus investment from the Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust, one of the first sovereign wealth funds in the world. The trust was charged with investing the hundreds of millions of dollars that Nauru earned from the harvesting of its bird guano; unfortunately for the island republic's 10,000 or residents, those at the controls did an incredibly lousy job of picking projects to bet on:

Unscrupulous foreigners have played a large part in Nauru's post-independence catastrophe. A series of shysters and con-artists persuaded Nauruans to fritter away their money. One Australian financial adviser persuaded Nauru to shell out £2m for a musical he had written about the life of Leonardo da Vinci, which folded after four weeks on the London stage. Another conned the government into spending $60m on "prime banknotes", a sort of derivative that turned out to be just as dodgy as it sounds. Much of the money was eventually recovered, but only after lengthy court cases spanning several continents.

Nauruans, too, wasted their fair share. Many investments were made for reasons other than economic merit. The island, whose remoteness in the middle of the Pacific is impossible to exaggerate, makes an improbable air-travel hub. Yet the government backed Air Nauru, which for a while boasted a fleet of five 737s. (It is now down to one.) It did not help that former presidents used to commandeer the airline's planes for holidays, leaving paying customers stranded on the tarmac. Similarly, a cruise ship based in Nauru did more for the people who worked on it than for the country's bottom line. Prime pieces of property have languished, undeveloped, for decades. The government of Fiji recently repossessed a hotel in its capital that Nauru had bought years ago and then left to rot. Another hotel, in the Marshall Islands, has been under construction for more than 20 years. Over A$50m (US$36.6m) was spent on a site in Melbourne that Nauru later sold for less than A$20m.

By the time Nauru was on the financial brink, it was too late—the island's phosphorous production had dropped to all-time lows (see above), with little chance of meaningful recovery over the long term. What should have been the most prosperous nation in the South Pacific has since been reduced to hosting an Australian detention center in order to make ends meet.

The Leonardo musical obviously played a relatively tiny part in the Nauru's financial woes. But alarm bells should have sounded when that investment went sour. At the very least, it betrayed terrible judgment on the part of those accountable for doling out the trust's funds. But when you have something on the order of $800 million in the bank account, seven-figure mistakes are too easy to ignore.

March 7, 2011

Architectural Antipsychotics

I'd wager that there isn't a single state in the nation that lacks an architectural oddity dubbed something like "The Strangest House in the World." You know what I'm talking about—that random tourist attraction that lies somewhere between two medium-sized towns, and is a testament to mankind's ability to develop total (and somewhat frightening) tunnel vision when a project captures the imagination.

My personal favorite has long been Wisconsin's House on the Rock, which grew out of a frustrated architect's desire to one-up Frank Lloyd Wright. But it sounds as if I would have been an even greater sucker for New Jersey's aptly named Palace of Depression, built during the Great Depression by George Daynor, a man who could charitably be described as being one can short of a six-pack. Daynor maintained a psychologically even keel during the Palace's early years, as the challenge of building and maintaining the place acted as a sort of Colzapine. But he lost the plot during the 1950s, and his desperate attempt to maintain the Palace's fame led to his bizarre downfall:

In 1956, Daynor gave the FBI a false tip as it was pursuing the kidnappers of a lost four-year-old boy. He said the suspects had recently been to the palace; his bald lie garnered him a year behind bars. By his own reckoning Daynor was 98 years old when he was sprung in 1958. Too feeble to keep up the palace, he wandered about Vineland wearing rouge on his cheeks and bobby pins in his hair. Even before his death in 1964 his home was slowly disintegrating.

From a psychological perspective, I'm interested in how dedication to specific tasks can help counter the symptoms of mental illness. I'm currently working on a major project that involves a similar situation—a person who dealt with multiple serious mental disorders by losing himself in intricate planning. I reckon that there is probably a pretty simple neuroscientific explanation for this—perhaps one can quiet rebellious parts of the mind by making sure that all the neurons are firing elsewhere.

March 4, 2011

The Devil Collects

Whenever I find myself running behind on a major project, my thoughts turn to a certain passage from Easy Riders, Raging Bulls that discusses Michael Cimino's utter disdain for logistical constraints. When infamous director started shooting Heaven's Gate in the spring of 1979, he did so with orders to stay within a $10 million budget (c. $29.2 million today) and to wrap up principal photography in 10 weeks. But once Cimino was out by his lonesome in Montana, that plan went all to smithereens:

Cimino's perfectionism knew no bounds, and it soon became clear that he was shooting at an exceedingly slow pace. While the budget visualized two script pages a day of a 133-page script, the actual rate was closer to five-eighths of a page. After the first twelve days, he was ten days and fifteen pages behind. He started losing ground at the rate of one a day for every day shot. He was building, tearing down, and rebuilding sets, as well as piling on extras by the cartload. Cimino was shooting ten, twenty, thirty takes of every shot and printing almost every one, ten thousand of feet of film a day (two hours plus of film), which cost $200,000 per day or about $1 million a week. By June 1, a month and a half into the shoot, Cimino had reached the $10 million mark, equal to the original budget. But there were still 108 pages to go.

Whether the finished product deserves mention in Microkhan's Bad Movie Friday series is up for debate; there are some killer visuals in the movie, but the pacing is weirdly lethargic and the constant speechifying is absolutely annoying. One thing we can all agree on, though, is that Heaven's Gate elicited one of the all-time greatest slams in the history of film criticism, from The New York Times' Vincent Canby:

"Heaven's Gate," which opens today at the Cinema One, fails so completely that you might suspect Mr. Cimino sold his soul to the Devil to obtain the success of "The Deer Hunter," and the Devil has just come around to collect.

The grandeur of vision of the Vietnam film has turned pretentious. The feeling for character has vanished and Mr. Cimino's approach to his subject is so predictable that watching the film is like a forced, four-hour walking tour of one's own living room.

Is Cimino at peace with his historic cinematic disaster and the fact that it basically turned his name to mud in Hollywood? Read this 2002 Vanity Fair profile and decide for yourself. The man claims to be at peace with his life, but there's definitely a deep sadness burbling beneath his radically altered appearance.

March 3, 2011

Quicksilver's Last Stand

News of the mercury thermometer's imminent demise got me wondering about where, exactly, our quicksilver comes from these days. Much to my surprise, I discovered that there is but a single mine in the world dedicated solely to the production of mercury. It is in Khaidarkan, a village in southwestern Kyrgyzstan, where the poor soil has made profitable agriculture a near impossibility. So despite the obvious threat to the local environment, the mine carries on much as it has since the early 1940s, when it was founded to replace Ukrainian mines that had fallen into Nazi hands.

Khaidarkan remains a lone holdout despite powerful international pressure to shutter the operation. Or, to put things more accurately, powerful international pressure from governments and environmentalists. Businesses, on the other hand, remain quite pleased about Kyrgyzstan's lone-wolf status as a primary mercury producer. This Norwegian report (PDF) explains why:

So why is Khaidarkan the only one still mining mercury for the global market? The main reason is the economic challenges facing Kyrgyzstan, particularly the region where the mine is located. The company that

manages the complex has been struggling with fluctuating mercury prices and continuous technical difficulties such as low ore grades and flooding of shafts with underground water. Many times the state-owned company has had to request subsidies and state support for continuing its operations and the initial efforts to privatize the mine did not yield results. Due to a lack of international regulations and control, Khaidarkan primary mercury is still in demand on the international market which contributes to the continuation of mining operations.

The bottom line is that, when it's functioning at peak efficiency, the Khaidarkan mine can produce mercury much more cheaply than operations where mercury is culled as a byproduct of other processes. And so businesses that require mercury for their products keep on going back to Kyrgyzstan.

The Norwegian report goes on to recommend that international money go toward retraining the inhabitants of Khaidarkan to perform other jobs (such as gold mining and handicraft production). But has anyone considered outright bribery? It is very difficult to tell a lifelong miner that he must abandon his profession at a relatively advanced age and learn a new trade. Lump sums of cash may be much more enticing for the locals, rather than funneling the aid through middlemen who might not have the local population's best interest at heart.

The whole Norwegian report is worth a read, if only for the spooky abandoned ferris wheel on page fourteen.

March 2, 2011

Behold the Pyramids

Something went terribly awry this morning when Microkhan Jr. dismounted from a shoulder ride; my glasses snapped in half as his size eights kicked against my nose, and I now find myself staring through crooked, taped-together frames that make me feel as if I'm wandering through a funhouse. I have a late-morning appointment to get a fresh pair, plus (gulp) my first-ever pair of contacts, so I gotta be brief here. But let me direct you to a slab or reportage that very much demands your attention: Dan Morrison's multi-part Slate series on "The Bernie Madoff of Sudan." I had no idea that Darfur had been victimized by a epic Ponzi scheme, one that ended up bilking roughly 50,000 people out of their meager life savings. Morrison (occasionally known around these part as "our man in Dhaka") got one victim to summarize the depressingly familiar particulars of the scheme:

The pyramid scheme began in early 2009 when Ismael, then a police officer who sold used cars on the side, opened an investment fund in Rahma Souk, or Mercy Market, not far from the state police headquarters in El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur state. The fund promised alarming returns. Investors would make in-kind payments of real estate or vehicles and receive, four to six weeks later, a check with a value of 150 percent of their initial investment.

To riff off of H.L. Mencken, no one ever went broke by underestimating a public's zeal to get rich quick. The Albanians can certainly confirm that bit of folk wisdom.

March 1, 2011

Charlie Don't Surrender

Over the past day or so, I've once again been flooded with mail regarding my Alcoholics Anonymous opus from last July's Wired. The reason, of course, is Charlie Sheen's recent decision to come out hard against the organization, which he accuses of being (and I paraphrase) a fraudulent mind-control cult with an abysmal success rate. Skeptics have rejoiced over adding such a high-profile figure to their ranks, while 12-step devotees have bemoaned the damage that Sheen's rants might do to addicts who require help. Epistles from members of both cliques have shown up in my inbox recently—some to mock, others to plead for help.

I want to point out that I consider myself neither an AA supporter nor a critic; I'm merely a writer who was curious enough to dig through the organization's history and methods, in an effort to figure out why Bill Wilson's system has endured and grown for over 75 years. I learned enough in the course of my reporting to know that Sheen's attacks are wholly unoriginal, especially his insistence that AA's "success rate" is a mere five percent. (That oft-quoted stat is based on a misreading of a 20-year-old AA member survey.) Yet Sheen is, indeed, correct in asserting that there are many paths to sobriety, and that one needn't follow the 12 Steps in order to recover.

My main takeaway from Sheen's tirades is that AA is unique in its ability to inspire such passionate love and hate. Those who stay in the program credit the Steps with, quite literally, saving their lives; those who choose another path to sobriety claim it's a cult every bit as creepy as the People's Temple. I spent a long time wrestling with the reasons for this sharp schism, and I don't think I ever came up with a satisfactory answer. But there is a quote from an early draft of "Secret of AA" that was left on the cutting-room floor, and I think it goes part of the way toward explaining why AA is do divisive:

The rigidity of the program is what turns off most prospective members, especially those who chafe at any tinge of religion. "You have to be pretty strong," says Lee Ann Kaskutas, senior scientist at the Alcohol Research Group in Emeryville, Calif. "You have to say, 'Okay, I'm going to smile and not get upset and not get hurt when someone tells me to get on my knees and pray. I'm not going to argue.' Because you really can't argue with them about the philosophy. It's not up for debate."

For AA members, the sacred nature of the Steps is precisely what makes the program work. But AA haters, that inflexibility is an insult to their autonomy and intelligence. That's why Sheen spent part of his Today Show interview mocking the language in the Big Book; he simply can't bring himself to buy into aspects of the system that he finds distasteful, for the sake of working toward a greater goal.

Again, let me stress that I take no sides in the AA debate—it works beautifully for some, and it skeeves out others. But no matter how an alcoholic or addict works toward sobriety, there is one common thread that runs through every successful recovery story: a sincere knowledge that one's old course was leading nowhere good. Does Sheen possess that wisdom? For the sake of his five kids, I sure as heck hope so.

Death and Honesty

Yesterday's Supreme Court decision in favor of the admissibility of deathbed hearsay has attracted a fair bit of attention, primarily because the two dissenters were an unlikely pair: Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Both justices objected to the fact that police officers were permitted to testify about a murder victim's last words, since doing so deprived the defendant of the ability to confront his accuser. But the court's majority stuck with centuries of common law, which have held that a dying person's last words deserve to be heard.

But is that bit of legal tradition rooted in faulty science? I raised the issue in a 2002 Legal Affairs piece that examined why, exactly, we feel that dying people are intrinsically honest—even when they spent their entire lives being quite the opposite. There is precious little research in this field, since experiments are impossible to construct. But one law professor with a medical background believes that dying declarations can't possibly be as faultless as we've long believed:

Rather than attacking a dead person's moral fiber, defense lawyers would be better off calling into question the reliability of a traumatized brain. In an era of DNA analysis, courts are keener than ever to hear scientific evidence based on laboratory studies. And medical research is fairly unanimous in asserting that murder victims often lack the physical ability to think or communicate rationally.

Bryan A. Liang, a University of Houston law professor, is the foremost advocate of this tactic. A medical doctor as well as a lawyer, Liang has spent considerable time in emergency rooms tending to trauma victims, witnessing firsthand the impaired mental functioning of the gravely injured. "When a person is opened up with a knife wound or is shot, we don't even think of taking their history, because we know we're not going to get anything out of it," he said. "When somebody is deprived of oxygen, when they're bleeding out of every orifice, [they] just simply are not going to be reliable and sharp-edged intellectually."

Conducting laboratory experiments on the neurological constancy of the dying is impossible, since their relative dementia before and after the mortal wound can't be gauged. But according to Liang, researchers have been able to mimic the effects of mild trauma on cognition by placing test subjects in barometric chambers, which simulate rapid, oxygen-depriving changes in altitude. A 1989 study in the journal Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine found that healthy young males who underwent such treatment suffered from severely limited functioning, particularly in "intelligence, reasoning, and short-term memory." It can sensibly be assumed that the effects would be even more extreme for a person whose hypoxia was due to a shotgun blast or extensive third-degree burns.

Read the whole thing and make up your own mind. I'm not saying that dying declarations don't have a role in the legal system. But each case is unique, and some last words may be more trustworthy than others. Unfortunately, the American legal system doesn't rarely takes such nuance into consideration.