Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 46

April 8, 2011

In Praise of Ugly Robots

For robot designers, the natural inclination has always been to make their creations look more and more human over successive generations. After all, isn't it safe to assume that we ultimately want our artificial analogues to reflect their makers' biological perfection? But there is a danger in this trend, depending on the sorts of applications one expects the robots to be used for. As I argue in this month's Wired, sometimes an ugly, utilitarian robot is the smarter way to go—at least when it comes to combat:

For robot designers, the natural inclination has always been to make their creations look more and more human over successive generations. After all, isn't it safe to assume that we ultimately want our artificial analogues to reflect their makers' biological perfection? But there is a danger in this trend, depending on the sorts of applications one expects the robots to be used for. As I argue in this month's Wired, sometimes an ugly, utilitarian robot is the smarter way to go—at least when it comes to combat:

Rest assured, robots that resemble their flesh-and-blood creators are on their way to the world's battlefields. According to a 2004 Darpa survey, US military officers believe that humanoid robots will begin filling out infantry units as early as 2025. Those android grunts will likely be descendants of Petman, a bipedal Boston Dynamics robot funded by Darpa that walks more gracefully than C-3PO. And they may take aesthetic cues from Vecna Robotics' BEAR, a military prototype that features a rounded head studded with soulful Bette Davis eyes.

Yet despite our love of science fiction, this coming trend in robo-aesthetics is a bad idea. By anthropomorphizing their products, robot designers may unwittingly be encouraging needless bloodshed. Because, as recent research shows, the more human a robot looks, the more likely the Homo sapiens at its controls may be tempted to make the droids go Rambo on their foes.

"Robots don't need to look like people to get a job done," says Leila Takayama, a research scientist at the robotics company Willow Garage. "Actually, sometimes it's better if they don't."

The meat of the anti-humanoid argument is that we want to encourage self-extension among robot operators—that is, we want them to really feel as if it's them on the battlefield, not some million-dollar bucket of bolts and wires. Because the more present the operator feels, the less likely he or she will be to commit morally despicable acts. And researchers have determined that this sort of self-extension happens a lot more when a robot looks like a vehicle rather than an animal or human.

I was a bit saddened to make this discovery, as I would prefer to live in a future where my wars were fought by robots that look like this rather than this. But I'll admit that my mind has been poisoned by a lifetime of science fiction, so my opinion should count for nothing.

April 7, 2011

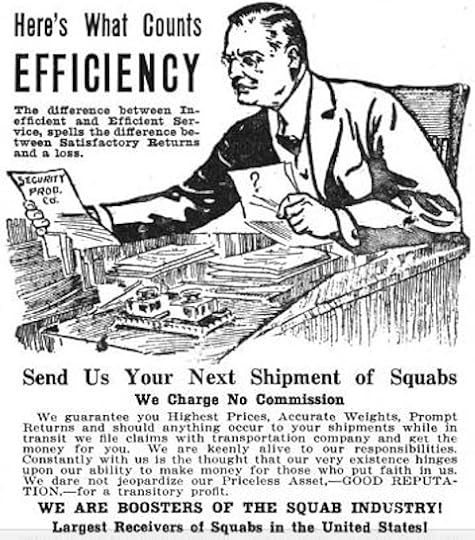

Edible Pigeons and the Misuse of Technology

One of my favorite Ponzi schemes of recent vintage was Pigeon King International, which convinced thousands of cash-strapped farmers to raise so-called "rats of the sky" in backyard pens. The scam's mastermind, Arlan Galbraith, claimed that poultry-loving North Americans were on the verge of falling in love with roasted squab, and that farmers who bred his birds would soon be rich beyond their wildest dreams.

Had the scheme's victims bothered to look back at the history of squab farming, they would have quickly realized that Galbraith was a con man. This was not the first time that men and women had been artfully duped by salesman stating that the Squab Renaissance was about to occur. In the 1920s, there was a massive squab bubble in the United States, as dozens of companies popped up to offer their services as bird brokers. Newspapers published regular reports on squab prices, and passed along the U.S. Department of Agriculture's assurances that this time, the forthcoming squab boom would really, truly happen:

Many years ago, a wave of enthusiasm over squab raising swept the country. Fabulous profits were told of and many people bought breeding stock and expected to make a fortune with little work in a short time. When they discovered that these figures were overestimated and that to reap a profit regular care must be given the birds, their interest slackened and they talked as much against the proposition as they had for it in the beginning.

As a matter of fact, pigeon raising can be conducted successfully as a special business, but is better adapted to serve as a side issue on a small scale in towns and cities and on general farms. The demand for squabs, especially in large cities, is increasing. Squabs are often used to replace dressed game, which is decreasing in this country.

We all know how this story turns out, of course: the chicken became king of America's dinner table, while the squab remained a curiosity—perhaps because people aren't too eager to consume the cousins of the birds they see eating garbage at the park.

So why does each generation seem to fall for the squab scam anew? I think a big part of the explanation is our willingness to believe that the march of technology will inevitably smooth out all problems. A big part of PKI's come-on was that new breeding and feeding techniques had made it possible for farmers to squeeze out more meat per invested dollar. This is exactly what the USDA told squab hopefuls back in the 1920s—that past failures of the squab industry were attributable to the fact that breeders lost too many pigeons to disease, or didn't have the genetic know-how to create the fattest birds possible. People fall for these lines, even in the absence of evidence, because we do trust that science is not only constantly advancing, but that it's advancing in all areas, no matter how obscure. And their assumption is that at some point, amateurs will inevitably be able to get the same results as committed professionals—and, in the process, be able to overcome the laws of supply and demand, to boot.

Should any aspiring squab breeders reach this post in the course of your research, I encourage you to check out this Jazz Age publication. And then consider why its author, F. Arthur Hazard, appears to have no other indelible mark on history.

April 6, 2011

Squabs TK

Got way mired in some morning reporting, and now the rest of the day is blocked off to attack the next monthly Wired column. Back tomorrow with a report on the squab bubble of the 1920s, and how investors too seldom learn from the missteps of the past.

April 5, 2011

To the Teeth

Granted, I haven't been following the whole "rebirth of piracy" story as closely as I should be. But I nevertheless floored to read this assessment of just how bad the situation has gotten, particularly for sailors who lack the personal financial resources to wriggle free of captivity:

Some 600 seafarers are at present held for ransom, and the average time in captivity has extended to around eight months. No nation had a strategy to tackle the problem, and seafarers were daily running the gauntlet of armed pirates, with ships' superstructures being penetrated by rocket propelled grenades, said Mr Hinchliffe. Unfortunately most flag states did not have the resources at their finger tips to provide military guards in the theatre of operation. "In these exceptional circumstances, it is our belief that the use of armed guards, private security, be permitted by the flag state when considered appropriate."

The riddle of how to stop a crime wave of this nature is near-and-dear to my heart, as it's central to the book I'm currently working on (often referred to in this space as "my next major project"). My reporting has taught me that when private concerns run the cost-benefit analysis on implementing meaningful security measures, they often conclude that it's cheaper to lose a certain percentage of their business to crooks. Lost loads can be covered by insurance, and if a shipping company waits long enough, it can doubtless win its employees' freedom for a relative song. (Somali pirates obviously hope to stumble upon sailors whose families have the means to pay sizable ransoms, but that is a huge gamble given that the majority of modern ship staff are Filipinos and Bangladeshis who come from exceedingly modest means.)

In lieu of hiring pricey armed guards, then, the easy solution would be to arm the sailors themselves. Yet would this lead to a noticeable uptick in on-board violence between sailors? It's extremely difficult to come by data regarding sailor-on-sailor crime aboard container ships. But I did find one study, which concludes that such violence is relatively rare:

Out of a total of 200 deaths in flags of convenience shipping, illnesses caused 68 deaths, accidents 91, homicide 3, suicide 7, drug and alcohol intoxication 4, and disappearances at sea and other unknown causes 27. Deaths from non-natural causes and, in particular, maritime disasters accounted for a significantly higher proportion of all deaths in flags of convenience than in British shipping. The maritime disasters largely involved small cargo ships foundering or disappearing in bad weather.

I actually feel that arms distribution wouldn't create significantly more sailor-on-sailor crime, since the cramped environment of a vessel provides no chance of escape, thereby ruling out most premediated assaults and homicides. But handing out guns would certainly given crew members more leverage in dealing with abusive captains, which is something that shipping companies don't want to encourage. For the moment, then, sailors entering the Gulf of Aden or other risky waters better keep their fingers crossed that their ensuing eight months won't be spent chained to a basement furnace in Mogadishu.

April 4, 2011

Up from the Underground

Though I only recently became aware of the fact that Burkina Faso is a hotbed of film production, I was completely unsurprised to learn that the nation's movie industry is deeply troubled. The primary culprit, as you might surmise, is piracy; as cinemas have vanished with the proliferation of affordable DVD players, the markets in Ouagadougou have become flooded with $1-per-disc knock-offs of the latest domestic releases. Burkina Faso's government lacks the resources to enforce copyright laws on a wide scale, and so pirates risk relatively little by peddling illegal copies of movies.

Yet the situation may not be as hopeless as it seems. During the Burkina Faso's latest film festival, a Nigerian journalist visited a pirate's shop in Ouagadougou. He came away from the experience thinking that if the film industry is willing to be pliable on price, the pirates might well prefer to go legit than continue to exist in the shadows:

he video seller explained to me how his business worked. He would prefer to sell legal copies of the films, he claimed, but he didn't know how to get them. When he went to Lagos, he would go to the market and buy films from the marketers. He didn't know how to contact the producers personally. He had one legal copy of a Ghanaian film that the filmmaker had brought personally to Ouagadougou, which sold for three times as much as a pirated film. He went to Lome to buy pirated films brought from China, and if there was a video, such as a recording from a television programme, that he wanted more copies of to sell, he would take it to Lome. From there it would be taken to Lagos and reproduced there…

Pirates seem to be reaching much wider markets than the current legal distribution networks have been able to reach. If there were some way for producers or legal marketers to partner with the pirates and turn their business legal, they would instantly reach a far wider audience than they currently have access to. Burkina Faso's model of the holographic seal (which the National Film and Video Censor's Board in Nigeria is also trying to implement) is one way to go. On the one hand, this seems positive, that the artists are actually seeing the profits and not struggling with pirates. On the other hand, I wonder if the lack of piracy limits the proliferation of their product to other markets in Africa, and if the dramatically different price between the legal and the pirated materials discourages people from purchasing legal copies.

The pricing issue is key. We assume that over time, the market will set the appropriate prices for goods. But what if that time horizon is so great that an industry collapses before the market can determine the right level? This is something I worry about right now in my own field; apologies to whoever determines such matters, but there is no way the Kindle version of Now the Hell Will Start should cost $13.

I'm not totally convinced that every film pirate in Burkina Faso would come in from the cold if offered legal copies of movies at cut rates, but it's worth a shot. Everyone seems to know where the pirates operate, after all; it's just a matter of the film industry swallowing some pride and admitting that the present course is untenable. If it does so, then today's pirates might become tomorrow's ordinary salesmen.

April 1, 2011

Revege of the Cobra (Kai)

Felt weird to leave my political thoughts atop the blog for the weekend—I know you come here for more off-the-beaten-path fare, since my smarter fellow travelers already have that beat covered. So I'm gonna outro from this crazy week with a quick lil' Bad Movie Friday entry: the Pat Morita death scene from 1999′s beyond-dreadful King Cobra. What bothers me here isn't Morita's scenery chewing, but rather the proportion error: How could fangs those big make such small incisions on a human neck?

Laissez-Faire

One of the pluses of travel these days is that it affords me the opportunity to catch up on reading. (The parents in the audience know well that young'uns page-rate down by quite a bit.) On this latest Texas trip, when I wasn't busy finagling my way into a remote immigration detention facility, I stole some hours to plow through Eric Schlosser's Reefer Madness.

This was an unusual pick for me, mostly because I was already familiar with a good deal of the content. The book is essentially a collection of three expanded magazine pieces, all of which deal with different aspects of America's underground economy. The first one, about the marijuana trade and its consequences, holds a special place in my heart: I read it back in college, when it first appeared as a two-parter in The Atlantic Monthly, and was so taken with the reporting and writing that I began thinking seriously about getting into the non-fiction game someday. I had also previously encountered parts of the book's third section, about the porn industry, when my old employer U.S. News & World Report ran one of Schlosser's stories about the topic.

But Reefer Madness was still well worth the read—in part as an object lesson on how to use reporting in the service of narrative, but also because of the nifty way in which Schlosser ties together the strands with thoughtful commentary. This conclusion, from the middle section about migrant farm labor in California, really got my mental gears cranking:

We have been told for years to bow down before "the market." We have placed out faith in the laws of supply and demand. What has been forgotten, or ignored, is that the market rewards only efficiency. Every other human value gets in its way.

This, I think, is the central tension in much of the left-right debate these days. Schlosser's sympathies obviously lie with the former, though I believe he's more of a centrist than most folks believe. The latter faction, meanwhile, argues that allowing the market free reign ultimately enables those at the bottom to slowly ascend over the generations. But Reefer Madness makes a convincing case that such mobility is more fantasy than reality, primarily because the game is rigged; the cycle of indebtedness upon which the labor market depends means that the rising tide lifts only a handful of boats.

Where I find myself most in agreement with Schlosser is in terms of our skepticism about philosophies that demand no deviation from core principles—no matter how much evidence piles up to the contrary. Both humans and history are complex, and so, too, should the systems that govern our behavior. This line nails it:

My own views tend toward suspicion of all absolute theories and a strong belief in thought that knows its limits.

What Schlosser is ultimately advocating for is something near-and-dear to Microkhan's heart: that we trust human judgment above inflexible systems of thought.

Apologies for the brief intellectual digression, which I reckon is very non-Microkhan-ish. Back to your regularly scheduled programming soon, with upcoming posts about the pig economy in Papua New Guinea, lighthouse development in Mozambique, and the pitfalls of electing coroners.

March 31, 2011

Let's Talk About Jesse

Flying home today on a supreme reporting high, one that will surely wear off as soon as I realize I now have to write the damn piece. Back tomorrow, after a night catching up with Microkhan Jr., the Grand Empress, and five dozen pressing emails. 'Til then, enjoy some political music from the '84 election—certainly the only song in existence to namecheck Lieut. Bobby Goodman. Big thanks to the soon-to-be-legendary Dr. Swerve-On for introducing me to this bit o' sonic history via his latest Fresh Produce broadcast.

March 29, 2011

Lone Star

Heading off to West Texas for a Wired reporting trip today, so light posting for the next lil' while. Until I manage to secure myself some dependable WiFi in the lightly populated triangle between Lubbock, Abilene, and Wichita Falls, please make do with highlights of the late-period Fly Girls. Sad to think such joyously athletic choreography has now vanished from the small screen, yet the depressing vapidity of Dancing With the Stars flourishes.

March 28, 2011

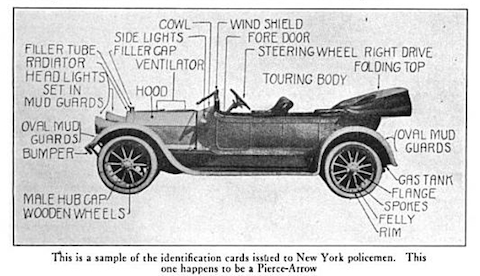

"One of the Greatest Evils of the Age"

I'm a huge believer in the notion that the good ol' days were not quite as halcyon as they're cracked up to be. That anti-nostalgia truism becomes especially clear when one examines crime data from bygone eras; Americans, it turns out, have been treating one another quite unkindly for generations. I made that point in a post last September regarding Jacksonville's once-astronomical homicide rate, which far exceeded that of Chicago at its early 1970s worst. Now I have another piece of evidence, in the form of automobile theft rates from Wilson Administration.

Take the case of Detroit, for example, which had a 1920 population roughly equivalent to what the decaying city claims today. There were roughly 3,360 automobile thefts in the Motor City in 1920, versus a tick over 13,000 in 2009. But you also have to factor in car ownership rates; only 3 percent of Americans owned autos in 1920. It is thus reasonable to surmise that a significant percentage of car owners back then had to suffer through at least one theft per year, despite the advent of various gadgets designed to frustrate thieves.

I initially thought that the majority of these bygone thefts were the work of joy-riders, who simply wanted to experience the magic of the internal combustion engine. But this account from Omaha's chief of police offers a different take:

I have found among the auto thieves who have been arrested here, many old time "Yegg" men, who have given up the blowing of safes and robbing of country stores and taken to the stealing of automobiles, as they figure they take less chances and make more money in the game when they have a "fence" in some other city who will handle stolen cars for them.

Then there are a lot of crooked chauffeurs, who, when they want to leave the city, generally figure on taking an auto with them. They usually find a sale for the car, as there is always someone in every city trying to buy something for half its value.

Not helping matters from a law-enforcement standpoint: the fact that there were just a handful of body styles, and thus no easy way to identify stolen vehicles.

Auto theft did decline precipitously during the 1920s, in part because of technological innovations, but also due to greater cooperation between police departments. It's easy to forget that America used to be far more provincial; the regional differences we notice today pale in comparison to the real animosity that formerly existed between states and cities. I wonder how much of that was due to the federal government muscling in on cases in which stolen goods were transported across state lines; if Hollywood has taught me anything, it's that city cops loathe nothing more than getting usurped by the Feds.