Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 44

May 6, 2011

"He Stayed to Write a Grander Legend"

Since I can scarcely imagine life without the biological rocket fuel known as caffeine, I'm counting my lucky stars this morning that I'm not a Cuban. That's because sky-high coffee prices have forced the government to cut rations, meaning that Cuba's java addicts must now satisfy their urges with a beverage partly concocted from roasted peas. One can only hope that easy access to sugar cane will be the poor coffee drinkers' saving grace.

Yet these deprivations have rarely fazed the Cubans; in fact, the Castro regime has survived for so long because of its ability to convince the populace that triumph over such hardships represents triumph over those who wish the nation ill. And the government is aided in this communications endeavor by those increasingly rare souls who made even greater sacrifices for the revolutionary cause—chief among them Teofilo Stevenson, the greatest heavyweight boxer who never quite was, at least in the professional sense.

Pugilistic enthusiasts never tire of speculating on whether Stevenson, a great Olympic champion, could have taken the heavyweight crown from Muhammad Ali in the 1970s. We never got a satisfactory answer to that question because Stevenson refused to defect, despite being presented with many an enticing opportunity. His reward for that willpower has been adulation in Cuba, rather than anything material comfort. As this great 2002 profile reveals, Stevenson's privileges are scant compared to what he would have received in any other country:

The man who could have fought Muhammad Ali – no, more than that: who could have been Muhammad Ali, famous throughout the world and rich beyond imagining – was fully awake after a drowsy morning. He said he'd be ready to go to lunch as soon as he washed up and changed his clothes. Here's what Teofilo Stevenson did next: He took a big galvanised bucket out to the front yard, filled it with water from the garden tap, lugged the bucket inside, hoisted it on top of the kitchen range and turned on the flame…

Stevenson went inside twice to check the water on the stove. When it was hot, he carried it to the bathroom and poured it into the tub. Now he could take a bath. There's no hot water from the tap at the house of the man who could have been Muhammad Ali, just cold…

The house is far from sumptuous, but comfortable – spotless linoleum floors, casement windows framed by floral curtains, utilitarian furniture. There is even a small swimming pool filling the little back yard, though it contains just a couple of feet of black, brackish water. Stevenson explained that it was far too expensive to fill and maintain the thing.

I wonder how many of Stevenson's houses could fit inside Mike Tyson's abandoned Ohio manion.

May 5, 2011

Nonlinear Athletic Niches

I'm heading upstate today to attend a workout with a world-class track-and-field athlete, as part of my reporting for a story about the limits (or lack thereof) of human performance. In the course of my research, I've had occasion to give a lot of thought to nonlinear athletic niches, a spin on the economic phenomenon previously discussed on Microkhan. Why do some nations tend to dominate certain off-the-beaten-path sports? There are clues to be found in this examination of Finnish javelin throwers, who have long ranked at the top of that sport's tables. One of the more convincing pieces of theorizing:

I'm heading upstate today to attend a workout with a world-class track-and-field athlete, as part of my reporting for a story about the limits (or lack thereof) of human performance. In the course of my research, I've had occasion to give a lot of thought to nonlinear athletic niches, a spin on the economic phenomenon previously discussed on Microkhan. Why do some nations tend to dominate certain off-the-beaten-path sports? There are clues to be found in this examination of Finnish javelin throwers, who have long ranked at the top of that sport's tables. One of the more convincing pieces of theorizing:

It is by no means a secret that there was money around in Finnish sports as early as the 1920s. Paavo Nurmi's hectic racing schedule on his home tracks as well as in Europe and the United States was the firm background for his later success as a business man and building contractor.

As for the javelin throw, sportswriter Urho Salo tells an interesting story. The late Yrjo Nikkanen – a magnificent natural talent, whose world record of 78.70m from 1938 stood for 15 years – told him he sometimes earned 'an equivalent of an army officer's monthly wages in one meet as an under-the-table payment – and there were many meets like that during the summer'.

According to sports historian Anttoi O. Arponen, 'thanks to his javelin capacity, a poor country boy could become a member of a leading club, at the same time getting better-paid work and climbing higher on the social ladder'.

And a hypothesis that I don't quite buy, though I certainly appreciate its poetry:

'The Finns have been moulded psychologically by the extremes of their climate,' says Turner. 'Long dark winters and short glorious summers have produced the archetypal strong but silent national character. The javelin suits the Finns, providing an emotional release for all their pent-up feelings. It's the dual release of spear and emotion which the Finns so much enjoy.'

Current world rankings for men's javelin here. The top American is a good 10 meters off the pace.

May 4, 2011

The Hazards of Herding Blitzen

In case you don't keep regular tabs on Scandinavian jurisprudence, I'd like to draw your attention to a recent legal triumph by a group of Sami reindeer herders who operate in Sweden's forbidding north. After 14 years of litigation, the herders have finally won the right to let their animals graze in the forests around Nordmaling, which are privately owned. Sami activists claim that the victory ensures the survival of their traditional profession, and thus continued sustenance for those who enjoy a nice slice of reindeer every now and then.

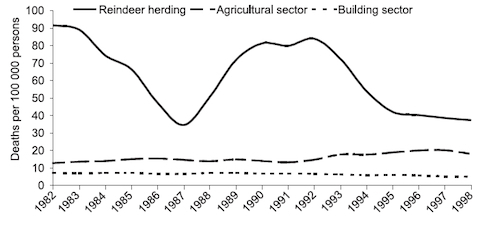

But while future generations of Sami herders might now be guaranteed grazing rights, their profession will continue to be far from stable. That is because tending to reindeer remains a fantastically perilous way to make one's living—so much so that it has attracted plenty of attention from occupational safety researchers, who are keen to reduce the endeavor's sky-high fatality rate. This 2004 study details the perils:

Reindeer herding implies many hazardous situations, especially during the gathering of the reindeer for migration or slaughter. During these periods the herders use vehicles to gather the reindeer (i.e. motorcycles, snowmobiles, helicopters, airplanes and boats), and the work is often executed during long working hours in harsh climate. For instance, it has been shown that most reindeer-herding men spend approximately 800 hours per winter on snowmobile. The increasing number of work-related fatal accidents among the reindeer herders is probably related to an increasing pressure from the Swedish society to develop profitable reindeer herding companies with less dependence on governmental support. This has resulted in external socio-economic pressure and competition between the family companies within the Sami communities, which in turn has forced the enterprises to make costly investments in vehicles to save time and personnel expenses…

The high number of work-related accidents among reindeer herders puts reindeer herding at the top among the most hazardous occupations in Sweden. A comparison of the present results and official statistics on work-related accidents in different occupations shows that work-related fatal accidents are more than twice as common among reindeer herders than within the agricultural and the building- construction sectors.

Still, it does seem a fair bit safer than elephant training.

May 3, 2011

Hiding in Plain Sight

I somehow doubt we'll ever hear the full story regarding what Pakistan's intelligence apparatus knew about Osama bin Laden's whereabouts these past five years. It is totally naïve to think they knew naught, of course; the big question is who in the spook food chain was in on the conspiracy, and (perhaps most important) what they stood to gain from keeping the matter under wraps.

My pessimism about the eventual resolution of these mysteries stems from past experience. Time and again, big-name fugitives have been found hiding in plain sight, obviously having enjoyed the protection of powerful figures. Yet no one ever seems to suffer any consequences for this sort of aiding and abetting—to mod an infamous Leona Helmsley quote, only the little people get pinched for helping evildoers. My favorite example of this truism pertains to the case of Salvatore Riina, the onetime boss of the Sicilian Mafia, who made bin Laden's time on the lam seem like child's play. Bin Laden, at least, reportedly kept to himself indoors; when he wasn't luxuriating in his massive hilltop villa, Riina milled about downtown Palermo at will:

During the 23 years that Salvatore Riina lived as a fugitive, he married in the church, fathered four children born in the same clinic, circulated freely in Palermo and ruled as dictator over the Mafia.

That freedom ended with his arrest in the Sicilian capital Friday. Amid the banner headlines and expressions of joy, many Italians asked how the country's most wanted man could have avoided capture so long…

Asked why it took so long to capture Riina, Carabinieri commander Antonio Viesti said he was protected by a "network of cover."

It's easy to see why the members of that network were never brought to account: They likely controlled the very apparatus charged with investigating the affair. I have no doubt that the people complicit in protecting bin Laden wield similar authority in Pakistan. In fact, those who provided cover for bin Laden will likely be the same officials who now crow the most loudly about the benefits of his demise. In corrupt systems such as early 1990s Sicily or modern-day Pakistan, the elites who last are those most adepts at playing both sides of the coin.

May 2, 2011

Let it All Come Down

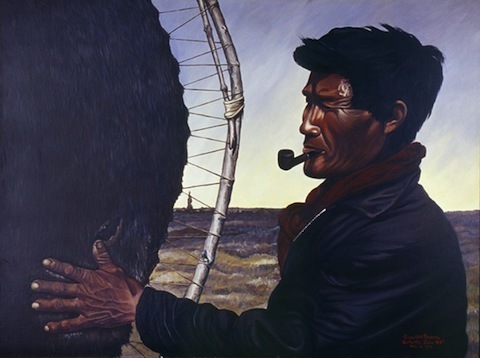

If you desire a brief respite from today's deluge of bin Laden-related news and punditry, take a sec to check out the work of Bern Will Brown. He's sort of the Paul Gaugin of the frozen north, having settled into the tiny Arctic hamlet of Colville Lake many decades ago. Though he originally journeyed up to Canada's northern climes as a Catholic missionary, he's now best known for his depictions of daily life in the Northwest Territories' remotest corners; along with his paintings, his 16mm film of Beluga whale hunting comes highly recommended.

April 29, 2011

Over the Bridge

Have a date with the American bureaucracy this morning, so zipping out with a lil' vintage Turkish funk. First got turned on to the tune above by a sample from Action Bronson's decidedly NSFW "The Madness", which I initially mistook for a new Ghostface cut. Not sure I'm tempted to sift through Ferdi Özbğen's entire back catalog, since it seems like a lot of it tends toward a Turkish Tom Jones vibe. But great to see producers following Madlib's lead and digging through ever more far-flung crates. I'm all for ditching those overused Isley Brothers' samples in favor of more Ivo's Group.

April 28, 2011

Requiem for the Slug Kings

A surprising number of tears were shed when the world's last manual-typewriter factory announced its shuttering a few days back. Once again, generations of technological know-how are set to evaporate as a once state-of-the-art invention tumbles into museum mode.

The manual typewriter industry's long-anticipated demise got me thinking about engineering wizards whose skills have been outmoded by the relentless march of technology. As a New Yorker, the first folks who popped to mind were Kim Gibbs and Alan Campbell, the so-called Slug Kings, who made minor fortunes in the '80s and early '90s by manufacturing counterfeit subway tokens. Operating behind a Midtown front business called KG Delivery Service, Gibbs and Campbell churned out untold thousands, if not millions, of brass discs that would permit their bearers to enter the city's subway system for a relative song. In 1991, Campbell described the technology and expertise invovled:

Around 1970 – the year the fare increased from 20 to 30 cents, triggering a mad run on all available slug supplies – Campbell was introduced, by chance, to the wonders of the reciprocating press, an industrial-strength hole puncher. He bought his own.

"The metal is slipped into long coils – really big ones are 300 pounds – and fed through the press," he recalled. "I believe it was Russians who figured out that a submachine gun could be made from a reciprocating press. Making a slug is the easiest and simplest use of the reciprocating press. You could make up to a million if you kept the machine going."

How many was he selling? "As far as the total, I didn't want documents like that in my possession," he said. "Sometimes I used newspaper articles to track it." In those early years, one could read that 2,000, 8,000, 10,000, slugs a day were being collected from turnstiles. On his prices, he is vague – "variable rates; at one point I raised it to 15 cents" – and while he has a diary somewhere, he believes any figures would sound deceptively large.

Much more here. I like how Gibbs and Campbell had a nickname for their counterfeiting ring: "The Ministry." Makes me think they spent way too much time studying the villains from Justice League.

April 27, 2011

Mushrooms for Strength

I'm currently up to my eyeballs in research on a piece about Soviet athletic excellence, which was a more enigmatic phenomenon than most folks realize. There really isn't one definitive explanation for the nation's sporting success throughout its last three decades of existence, though there are certainly plenty of theories. As I've become immersed in the topic, I've started to believe that the primary reason for the Soviets' athletic achievement was total dedication, made possible by a system that offered unusually special privileges to those who gave up their entire lives in pursuit of world records—many of which are still held by Soviets who competed in the 1980s. For a small glimpse of the devotion required to be an elite Soviet athlete during this time period, I encourage you to check out this interview with hockey star Anatoly Firsov, who discusses (in poorly translated English) the constant effort demanded by his coach, the legendary Anatoli Tarasov:

I'm currently up to my eyeballs in research on a piece about Soviet athletic excellence, which was a more enigmatic phenomenon than most folks realize. There really isn't one definitive explanation for the nation's sporting success throughout its last three decades of existence, though there are certainly plenty of theories. As I've become immersed in the topic, I've started to believe that the primary reason for the Soviets' athletic achievement was total dedication, made possible by a system that offered unusually special privileges to those who gave up their entire lives in pursuit of world records—many of which are still held by Soviets who competed in the 1980s. For a small glimpse of the devotion required to be an elite Soviet athlete during this time period, I encourage you to check out this interview with hockey star Anatoly Firsov, who discusses (in poorly translated English) the constant effort demanded by his coach, the legendary Anatoli Tarasov:

Lucky were those who were close to [Coach Tarasov]. All out free time with him we were going out. He especially liked to go for mushrooms. He had a place slightly farther than I now have my dacha. We arrived in the evening, went into forest while it is slightly going darker. He gave us some 15-20 minutes, and then we returned after a whistle. And then the most sweet began — preparation of mushrooms, in oil, in sour cream, in own juice. Then we laid down to rest. Early in the morning we wake up, he about 3:00 a.m., we a little bit later. And here I realized for the first time what it costs to me. When he saw, how I pick up mushrooms, — when you calmly came by, bend, cut, put it in, get a joy — he shouted for a half of the forest, "First, what are you doing! You must pick up mushroom! To sit down on one leg, on another leg, land on one buttock, and then tear off the mushroom, not only with one hand, but with another as well, and keep an eye to make sure, that nobody else could pick the mushroom up!" So he in every moment looked for an opportunity to train.

Once, when we after Olympic games, went by train was it to Sverdlovsk or where? Olympic champions, we went in a common 3rd-class carriage, together with everybody else, no special compartment, nothing. On one station, in Kazan, it seems, he suddenly says, "Well, boys, everybody quickly out and begin training. We have 10-minutes stop, and we must train very well." We had been going already about two days, and for him it was very fearsome that we are without training. So he forced us to jump on steps of a carriage, run, tumble, we were looked at like strange people. "Olympic champions, what they are doing?" But for us it was important to hold a training in any conditions, and when we were tumbling on a platform, people could not understand what are they doing, is it an Olympic team or they are being transported to a crazy house? How it is possible to jump, leap and tumble on a snow, on an asphalt? But for Tarasov there was nothing more important than training with a use.

These anecdotes, of course, remind me of how this East/West paradigm was flipped on his head by the training montage from Rocky IV, in which Ivan Drago uses the latest technology to prepare for the climactic bout, while Sylvester Stallone saws wood in foot-deep snow.

(Image via English Russia)

April 26, 2011

What's in Wyoming?

Limited time to work today as Microkhan Jr. still has one day left of spring break, which he has apparently decided to spend attempting to coax me into serial games of hide-and-seek. Trying to grab a few hours here and there to focus on what pays the bills 'round this humble yurt, and that means half-assing it on the blog this morning. In lieu of the standard fare, then, enjoy the 39-year-old news clip above, about the bizarre Brooklyn bank heist that inspired Sidney Lumet's Dog Day Afternoon. Check out the lead robber's mannerisms in particular, as he gestures to the assembled crowd—Al Pacino just nailed the nuances of those arm waves in the movie.

April 25, 2011

The Folly of Youth

I'm just now getting cranking on a sports-related project—my first crack at writing about the athletic games that adults play since I covered the Nagano Olympics as a mere cub. To get into the right mindset for the challenge, I've been looking up the old Sports Illustrated stories that influenced me so deeply as young'un. Though I typically credit my college-age encounters with longform journalism for steering me down my current path, my love of in-depth storytelling actually dates back to my weekly consumption of SI in grade school and junior high. Looking back at some of those great SI pieces now, I'm struck by their artistry and detail; the best of the lot were darn near perfect, little jewels of the craft that deserve to be dissected and analyzed the same as any contemporary David Grann masterpiece.

One of the standouts is a story that I was able to found solely because a couple of lives have never left me. I couldn't remember anything about this piece save for the fact that it was about prison sports, and that it contained the tragic tale excerpted below—a tale in which the simple observation in bold managed to echo in my noggin' for the next 23 years:

During his first stint in prison, at the Georgia Training and Development Center in Buford, Leroy Fowler got a chance to go to an Atlanta Braves game as a trustee with Billy Shaw, a guard who also coached the prison baseball team. When they returned to Buford, Fowler told Shaw that he had a better fastball than anybody he had seen that night, and Shaw couldn't disagree. Fowler had a slider and an overhand curve in addition to what's reputed to have been a 95-mph heater.

"Fast? Oh, yes sir!" says Shaw, who is now deputy warden, when he's asked about Fowler's arm. "Our team barnstormed all over the state back in 1966 and '67, playing Georgia Southern and a lot of semipro teams. We never lost but a couple of games, and Leroy pitched them all."

The Cardinals and the Dodgers expressed interest in Fowler and told him to call when he was released. Then, just four days before he was to be paroled, Fowler, who was 20 at the time, escaped with one of his buddies. Why? "I was young and stupid," says Fowler, realizing even as he speaks that what he did extends beyond stupidity to self-destruction.

Fowler and his pal stole a prison officer's car and drove to Atlanta, where they watched a Braves game. Six months later Fowler was recaptured, but he escaped again in 1971. This time he went to a Cincinnati Reds try-out in Marietta, Ga., where he used a false name and took his turn with the other pitching hopefuls. Fowler says now of the scouts, "I think they were interested in me. I got to bringin' it pretty hard. I pitched three innings, and they asked me to come back the next day." Unfortunately, somebody in the stands who had seen him pitch on the prison team, recognized him, and Fowler ducked out, left town and didn't return.

A year later, he was recaptured after taking a blast from a policeman's shotgun in the right arm. He was in the prison hospital for six days before undergoing surgery, and, as he lay there, Fowler asked himself if he was a failure because of fate or bad luck or ignorance or maybe because his arm was an arbitrary gift that made him hope for more than he deserved.

The injury cost him the use of his little finger and caused nerve damage in the ring finger. He rehabilitated the arm as well as he could, but he was through as a prospect. A prospect needs it all. Fowler is now a star on the inmate Softball team, a power hitter with a really good arm and one of those sad stories nobody wants to hear.

I'm not sure why Fowler's unvarnished admission of idiocy made such an impression on my young brain. It's partly because even at that young age, I was astounded by the sheer stupidity of his decision to escape. But the line might've washed right over me if the writer, Rick Telander, hadn't somehow managed to make me care about a felon—and in such a modicum of space, to boot. And that is the great trick of nonfiction: To make the reader understand that every character, no matter how high or low, must cope with basic human needs and emotions.

Moving on now to another SI classic from my youth: Gary McLain's personal account of his cocaine abuse at Villanova. Yes, I have a thing for stories about wasted talent.