Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 41

June 24, 2011

How They Saw Us

All the time I spent delving into the Soviet sports machine for my hammer-throw saga got me thinking a lot more about the "Evil Empire" my youth. One of the first truly adult books I read was Hedrick Smith's The Russians, because I as so curious about what daily life was like in the nation that (according to the politicians and entertainment moguls of the day) desired nothing more than to turn us into slaves. The book was way, way over my grade-school head, but there are certain details I still recall—like this one part about how young Soviets had to hide their affection for The 5th Dimension, since all Western music was considered decadent.

Another facet to my early fascination with the Soviet perspective was how their propaganda differed so markedly from our own—to the point that it seems nothing short of laughable, no matter how beautifully presented. The prime example here is Vladimir Tarasov's Shooting Range (above), a truly gorgeous animated short with a message that is basically the the polar opposite of the one conveyed by the Wendy's Soviet fashion show. A fan of Tarasov's artistry explains here:

No two ways about it, Shooting Range is pure unadulterated propaganda. Its story is also simple; a young man wanders the bustling metropolis desperately looking for a job, a mere innocent peasant in the hands of corporate evil and greed. So naturally, our hero eventually finds a job from a lasciviously kind tycoon, as a human target in a shooting range. Live in a capitalist world, and you are setting yourself up as a walking bullseye. It's essentially The Most Dangerous Game for the set who found that film to be a bit too subtle. But once again, the animation is stunning to behold, a sense of movement that really does convey a level of panic in the viewer. That, and it's hilarious. Intended effect be damned, it's hilarious.

There's a question here of how much a laughable message compromises our ability to appreciate the art. Everything about this film is so expertly done—as some YouTube commenters have noted, it almost makes you wish that the Russian style of animation had triumphed over Japanese anime as the go-to obsession for geeks. But as is so famously the case with Triumph of the Will, the political dimension of the film vastly complicates our ability to appreciate it.

I'd love to dig up an interview with Tarasov to see how he came to create such head-thunkingly obvious propaganda, and whether he has any regrets about taking his career in that direction. The anti-Americanism in the film seems to virulent to have simply been put there due to government marching orders; Tarasov's heart was in this project, for better and for worse.

June 23, 2011

Where in the World is The Human Fly?

Inspired by The New York Times' successful effort to crowdsource a solution to a Nazi mystery, I've decided to try something similar in these slightly less august digital pages. Instead of identifying a photographer who documented the brutality of war, my goal is to find out whatever became of Rick Rojatt, a Canadian stuntman who performed daredevil feats under the moniker The Human Fly.

Inspired by The New York Times' successful effort to crowdsource a solution to a Nazi mystery, I've decided to try something similar in these slightly less august digital pages. Instead of identifying a photographer who documented the brutality of war, my goal is to find out whatever became of Rick Rojatt, a Canadian stuntman who performed daredevil feats under the moniker The Human Fly.

Perhaps you're familiar with Rojatt's alter ego, as it was the basis for a short-lived Marvel Comics series in the late 1970s. While the comics made the rounds, Rojatt cashed in by traveling around North America, walking on airplanes and piloting jet-powered motorcycles. He also created for himself quite a mythical backstory, as related in this 1976 People profile:

Rojatt, a Canadian, says he once was a Hollywood stunt man—although the California union has no record of him. He also says he was in an auto accident in North Carolina six years ago which killed his wife and 4-year-old daughter and badly injured him. He had 38 operations in four years, he says, which allowed him to walk again but left him with a body that is "60 percent steel parts." He says he conditions himself by rising at 3 a.m., running six miles and then plunging into a bathtub full of ice cubes.

But at the very height of his fame, Rojatt suddenly disappeared. The fact that he never appeared without his trusty mask made his incredibly difficult to track—he kept his face concealed even when collected his appearance fees from event promoters. Rojatt's fate has been the subject of much speculation, the best of which is compiled here. I'm rather fond of the theory that he swapped daredevilry for folk rock, but I fear that the true explanation isn't quite so pleasant.

I thus appeal to Microkhan readers who may have deep contacts in Canadian stuntman circles. Any idea of what Rojatt did after he ditched the mask for good?

June 22, 2011

Try, Try Again

There are few more hallowed legal principles than the protection against double jeopardy, which is enshrined in various constitutions and codes throughout the world. But as allegedly unimpeachable DNA evidence has become more common in courtrooms, a backlash has developed against the centuries-old prohibition against trying a person again after they've been acquitted. In Scotland, for example, a new bill has allowed for the retrial of certain suspects if very strong evidence comes to light after an acquittal. And now there's a serious reform movement afoot Down Under, too:

There are few more hallowed legal principles than the protection against double jeopardy, which is enshrined in various constitutions and codes throughout the world. But as allegedly unimpeachable DNA evidence has become more common in courtrooms, a backlash has developed against the centuries-old prohibition against trying a person again after they've been acquitted. In Scotland, for example, a new bill has allowed for the retrial of certain suspects if very strong evidence comes to light after an acquittal. And now there's a serious reform movement afoot Down Under, too:

The father of one of the victims of the Walsh Street police killings has backed the Victorian government changing the state's double jeopardy laws.

Frank Eyre, the father of Damian Eyre who was gunned down in 1988 along with colleague Steven Tynan, said he supported changing double jeopardy rules, which prevent acquitted suspects from being retried for the same crime.

According to reports one of the four people acquitted of the Walsh Street killings, Peter John McEvoy, allegedly told police in NSW that the sweetest thing he ever heard was the dying words of one of the young constables…

The coalition government pledged during the November election campaign to shake up double jeopardy rules, with legislation expected to be introduced to parliament before the end of this year.

The legislation will open the way for retrials when there is new and compelling evidence that a person acquitted of a serious crime was in fact guilty.

Attorney-General Robert Clark has said the Walsh Street killings could be one of the cases where a retrial is possible.

I understand the urge to chip away at the double-jeopardy ban, but it makes me pretty uneasy. True, the Founding Fathers and other long-ago lawgivers couldn't have foreseen how DNA would alter the criminal-justice process. It must be horrific for the families of murder victims to learn years later that some scrap of skin or hair finally nails an acquitted suspect.

But if the ban is scrapped in part, how do we ensure that governments play fair? Double jeopardy was initially done away with because the people didn't trust their rulers to pursue each case honestly—there was always the fear that on the second attempt, a prosecutor might magically discover some piece of evidence that had previously escaped his attention. Are we at the point where we no longer think that such misconduct is possible?

And perhaps more important, is our faith in scientific evidence a bit too total? My longform take on that issue can be read here. Suffice to say, I think any technology operated by humans is subject to error—and that's doubly the case when the analysis comes from only one source (that is, from the prosecution). Such evidence needs to be given the most serious consideration at trial, of course, but is it such a gamechanger that it justifies the upending of roughly 900 years of legal tradition? Legislators must ponder that question very carefully.

June 21, 2011

The Most Invincible Record in Sports

For those loyal Microkhan readers who've been wondering why I've been posting so much about the hammer throw, consider the mystery solved: my long-gestating ESPN the Magazine piece about Yuriy Sedykh's 1986 world record is finally out. I'm particularly excited about the story because it grew out of a Microkhan post—back in this ongoing project's earliest days, I expressed my admiration for Sedykh's achievement, along with my puzzlement over why it hasn't been bested in well over two decades. So glad I got the chance to delve deep into the brawny Ukrainian's backstory, as well as the science of elite athletic achievement. A snippet to whet you appetite:

At 6'1″ and a fleshy 240 pounds, Sedykh was neither the biggest nor the strongest thrower in the Soviet system. But he possessed an attribute that is far more critical to hammer success than mere muscle. "I understand my body," he says. "I give orders to my body and make everything coordinate." That skill was key because the hammer throw heavily penalizes the most microscopic of errors. When the ball and wire are whipping around at maximum velocity, every tic is amplified until it threatens to become ruinous. The difference between a gold medal and 28th place is often a matter of a foot pulled a few degrees off-center, or a shoulder dipped an inch too low. Bondarchuk had Sedykh practice with 10- and 12-pound hammers until he understood every nuance of "the dance."

As he struggled to develop the most seamless throwing motion possible, Sedykh came to view the hammer as having more in common with ballet than the discus. "When you see a ballerina jump, she's like a bird, how she flies so easy," he says. "People are always excited when they see this. They cannot imagine how hard it is to come to this easy, the hundreds of hours of practice, practice, practice. This is also true for hammer."

With so many thousands of throws required to hone technique, the sport's best competitors are typically in their early 30s. But at 21, Sedykh won gold at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal with a throw of 77.52 meters. Four years later, in the Black Sea resort town of Leselidze, he broke the world record twice at a single meet, raising the top mark to 80.64 meters.

His first reign as world-record holder lasted a mere eight days. On May 24, 1980, a 22-year-old Soviet thrower named Sergey Litvinov stunned the track-and-field world by besting Sedykh's mark by more than one meter.

The nemesis had arrived.

At some point, I should probably post video of my own attempt to throw the hammer. As I note in the story, it was a pretty disastrous affair, which makes it an awful lot of fun to watch. I just consider myself lucky that I didn't pull an arm free from a socket.

June 20, 2011

Tempting, But…

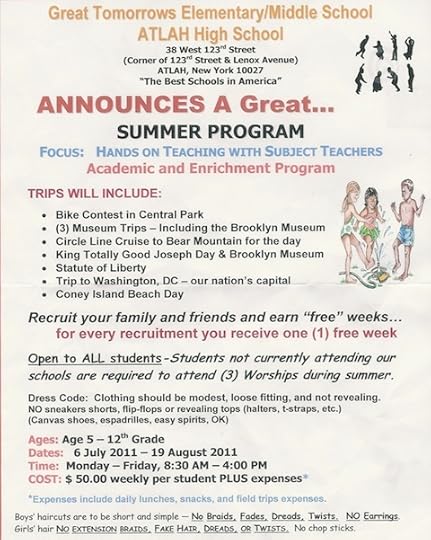

Banging out these words from the new global headquarters in Sunnyside, having left Harlem in the dust after seven wondrous years. As Microkhan Jr. and I headed for the 125th Street subway stop for the very last time, we passed one of the neighborhood oddities I'll truly miss: the ATLAH World Missionary Church, infamous for its virulent anti-Obama stance. (Straight from the source here.) Standing outside was a girl of about eight, who handed the boy and I the flyer above. Yes, these folks have a day camp, and our progeny could take part for the low, low price of $50 per week (minus unspecified expenses).

As fate would have it, we are looking for some way to occupy Microkhan Jr.'s time now that his preschool has called it a year. But as much fun as that clip art makes the ATLAH camp appear, a few things on this flyer give me pause. For starters, the bold claim at the top regarding the church's schools being among America's best. Then there is the completely unexplained reference to "King Totally Good Joseph Day," which compelled me to look up the holiday's origins in James David Manning's delightfully zany The Oblation Hour, which is subtitled "This is a time-proven method to receive tailor-made, real-time, and fail-proof information on a daily basis to guide your life." (Points for correct use of serial comma, penalty for repetition of the word "time."–copy editor).

To briefly summarize: King Totally Good Joseph is a chess-playing angel who Manning met in Prospect Park about 25 years ago. This angel instructed Manning to use only "good words" from that point forward, a commandment that the pastor has evidently violated in his political discourse. KTGJ also displayed a penchant for combat boots and long overcoats—a slightly more badass look that we normally expect from heavenly visitors.

I'm crazy curious about how KTGJ's holiday is celebrated. But that alone is not reason enough to send Microkhan Jr. to ATLAH's summer camp. If any readers have the inside scoop on the day's festivities, please advise.

June 15, 2011

Beneath the Elevated

Little time for Microkhan-ing between now and the weekend, as the Golden Horde is in the midst of packing up its yurts for points not-too-far-afield. After seven years in the blessed Paradise known as Atlah, we're moving across the East River to a land with a slightly Brave New World-ish name. Always bittersweet to move, but looking forward to at least one fantastic perk: Henceforth, I will be writing in my own private throne room, rather than on the floor of Microkhan Jr.'s chamber.

Hope to get back at y'all sooner rather than later. For now, though, watch the above to learn a bit more about how the Soviet Union managed to so thoroughly dominate the sport of hammer throwing for the better part of the Cold War. As far as I can tell, it was all about balletic footwork, practiced by men just a shade smaller than grizzlies.

June 14, 2011

Bucking the Trend

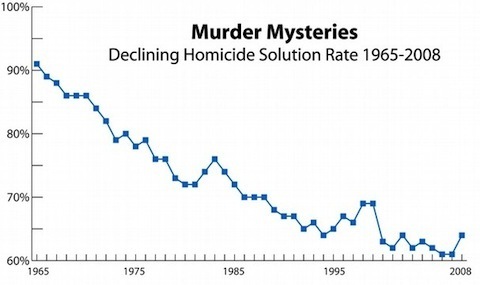

There is great wisdom to be gleaned from studying anomalies, which is why the El Paso Police Department's homicide unit deserves our attention. It is the rare squad that appears to be solving an ever-greater percentage of its cases, thereby defying the nationwide trend illustrated in the graph above:

Since 2004, unit detectives have investigated 106 slayings and solved all but four of them. Two homicides this year have yet to result in an arrest. However, detectives said they're closing in on possible suspects in those killings.

According to FBI statistics, 91 percent of the murders investigated by the Police Department between 2000 and 2008 have been solved. On average since 1980, the department has had an 87 percent homicide clearance rate, compared with the national average of 63 percent.

The article goes on to credit the detectives' tireless dedication, but that's probably not a very good explanation—plenty of city's have homicide investigators who give it their all. My hunch is that there is something about the nature of the cases in El Paso that makes them easier to solve. The story does flick at the fact that the city's cops enjoy an unusual amount of cooperation from witnesses, though it doesn't offer a convincing reason as to why that's the case. Do El Paso residents feel more immune to intimidation than people in comparably sized cities? And if so, is that a product of a social mechanism that condemns omertà? Someone with criminological chops far greater than Microkhan's, please shed some light.

June 13, 2011

A Light from Njoro

Revising the latest Wired opus all day, then segueing into some hardcore packing for Queens. And so I give you one of the best Biggie remixes of recent vintage, which first crossed my ears last night courtesy of the always-on folks at WEFUNK. While you're listening, give this update on the fight against Ug99 a quick read; my take on the lethal fungus is here.

June 10, 2011

The Ponchos: Sean Young in Wall Street

After a long hiatus, it's finally time for the esteemed Microkhan jury to hand out another Poncho, an award given to supporting actors who utter memorable throwaway lines that often outclass everything else in their film. You might recall that the first-ever Poncho went to its namesake, Richard Chaves, who played one of The Arnold's doomed compatriots in Predator. Has any actor ever expressed the will to live in such transcendent fashion? I think not.

After a long hiatus, it's finally time for the esteemed Microkhan jury to hand out another Poncho, an award given to supporting actors who utter memorable throwaway lines that often outclass everything else in their film. You might recall that the first-ever Poncho went to its namesake, Richard Chaves, who played one of The Arnold's doomed compatriots in Predator. Has any actor ever expressed the will to live in such transcendent fashion? I think not.

This time around, the hallowed statuette shall be shipped to Sean Young, best known these days for (and how do I put this gently?) several fries short of a Happy Meal. The inevitable "what happened?" articles about Young's career always mention No Way Out as her crowning achievement, but that's only because the critics haven't been paying enough attention to her glorious (and exceedingly brief) appearance in Wall Street, where she played Gordon Gekko's over-privileged, possibly Valium-addled wife. It was meant to be a larger role, but Oliver Stone reportedly disliked Young so much that he booted her from the set after a couple of scenes and wrote her out of the plot. (Familiarize yourself with the lines that Kate Gekko might have uttered by reading the original screenplay.) Still, Young did the best she could with her limited screentime, especially in the great pool scene.

Young is barely a presence in this scene, as it basically focuses on plot-driving banter between Gekko and his protege Bud Fox. But if you listen closely, you can hear Young talking to the nanny in the background, regarding the afternoon's plans for her son. And that is when she utters this Poncho-worthy line:

Put him in that cute little sailor suit.

The delivery is key here—the obviously put-on posh accent, the callous attitude that clearly indicates that the Gekkos consider their child little more than an expensive plaything. The boy is there for their amusement, to toy with as they see fit, until more important business (particularly making and spending money) comes around.

It's a heartbreaking line, one that I've been thinking about a lot these days as I observe my fellow parents here in New York City. How many of them view their children simply as accoutrements of their fabulous success, rather than real, live human beings? More than I'd care to know, I fear.

I could easily award Young a double Poncho for a line she spouts at a cocktail party earlier in the movie—her "Are you staying for dinner?" is so dreamily drugged-out, as if she'd spent all day popping Xanax and ordering expensive handbags over the phone. But the official rules bar such double dips, so Ms. Young will have to content herself with a lone trophy.

June 9, 2011

Skin in the Game

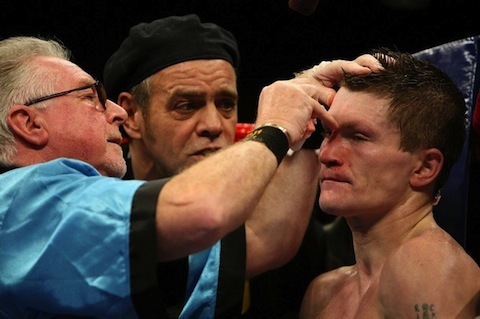

Given all we know about the wonders of the placebo effect, I'm always deeply skeptical about alternative medical practices that have never been the subject of peer-reviewed scrutiny. Yet I'm also deeply fascinated by the techniques employed by legendary boxing cutmen, many of whom had the ability to stanch geysers of blood—without sutures—in less than 60 seconds. I suspect that there is real medical wisdom to be gleaned from their experiences, but the secretive nature of their craft has prevented it from being seriously studied. Cutmen tend to guard their methods and potions as trade secrets of the highest order, a fact that may add to their romantic allure, but which frustrates anyone who might be interested in learning how pugilistic medicine might be adopted for everday ER use.

But every once in a while, a cutman opens up about a few of the craft's proprietary secrets. Such was the case with Milt Bailey, the former cutman for Sonny Liston and Joe Frazier, who dished a little dirt to the Philadelphia Inquirer two decades ago:

Bailey's modern tools include a small, oblong, stainless-steel press that he uses to apply pressure to cuts. Before the press, cut men used silver dollars to stop the blood.

"I don't do much talking in the corner," Bailey said. "I go in and immediately hit him with a cold cotton swab. If it's a vein that's like bleeding real bad, that's when you try and compress it. You push down with one hand, put the medication on with the other hand. Sometimes I get blood on my jacket."

In his ringside bucket, Bailey carries a water bottle; a bottle of adrenalin, which acts a coagulant; Vaseline, and three bottles of secret solutions. In the past, Bailey has used a mixture of ammonia, water and peppermint schnapps to revive fighters.

"It's illegal today," Bailey said.

Another interview with a celebrated Philadelphia cutman, Joey "Joey Eye" Intrieri, can be found here. Note his caution regarding the blood-thinning effects of energy drinks, which make a cutman's job that much harder.

(Image via British Boxers)