Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 47

March 25, 2011

The Art of Catching Lampreys

Following up on an earlier post about the decline of England's enthusiasm for eels, I spent (wasted?) a fair bit of time this morning digging into America's long-standing hatred for lampreys. These parasitic fish, widely held responsible for the death of King Henry I, were once on the verge of conquering the Great Lakes; they were essentially the Asian carp of their day, inspiring conservationists to dream up all manner of zany schemes to stop their invasion. We eventually stopped the lamprey from becoming too great a nuisance with the invention of TMF, an effective lampricide that has been dumped into the Great Lakes since 1958.

I did wonder, however, whether there were any serious efforts to convince the American public that lampreys were a delicacy on par with cod or halibut. They were enjoyed not only by English kings, but also by generations of Maori, who called the fish piharau and used ingenious means to ensnare them. Perhaps all the lampreys needed was better PR—or, perhaps, a pact between the U.S. government and Long John Silver's to develop a tasty breading-and-frying method.

By the way, yes, I realize that I cheated with the image above—lampreys are not eels. I just wanted a nice excuse to point your toward this fantastic trove of materials related to Maori eeling techniques and technologies. I found the eel spears to be particularly impressive.

March 24, 2011

Messing with the Bull

I have mixed feelings about Ross Dunkley, the Australian who co-founded the Myanmar Times in 2000. It's impossible not to admire his moxie; rare is the publishing soul brave enough to open a new information venture in a totalitarian state. But Dunkley obviously had to make some bargains to earn that opportunity, and that meant partnering with some rather unsavory characters—men with strong ties to Burma's sinister ruling junta, who demanded a 51 percent stake in Dunkley's media company. When one of his first partners ended up in prison after a 2005 political purge, Dunkley kept chugging along with the replacement offered up by the generals: Tin Tun Oo, a wealthy operative from the government's information ministry. I have no doubt that such ties have occasionally affected the way in which the Times reports news.

But now Dunkley is learning just how easily he, too, can be squeezed out of the picture, thanks to Burma's utter lack of transparent due process:

At the fifth hearing in the case against the Australian founder of the Myanmar Times, Ross Dunkley, a Burmese court on Wednesday again denied him bail and set a sixth hearing for Tuesday, March 29…

Dunkley has been charged with violating the Immigration Act, assaulting a woman, giving her drugs and holding her against her will. He was arrested on February 10 and taken to Insein Prison the next day. Dunkley's business associates said in an earlier statement that the alleged female victim testified in a previous hearing that she wished to withdraw her complaint that alleged she had been drugged by Dunkley but the Burmese authorities would not allow the complaint to be withdrawn…

Rangoon media observers said that Dunkley and the Myanmar Times' new CEO, Dr. Tin Tun Oo, were involved in a business dispute at the time of his arrest. Tin Tun Oo was named the new CEO four days after Dunkley's arrest.

Perhaps Dunkely is, indeed, guilty of the charges levied against him. But my gut tells me otherwise; it instead whispers that this is all a part of the junta's growing campaign to clamp down even tighter on the nation's information flow—a campaign that has also included a ban on Skype and other VoIP services. The generals have no intention of getting ambushed by technology, like their dictatorial brethren in the Middle East.

March 23, 2011

Are You Reeling in the Years?

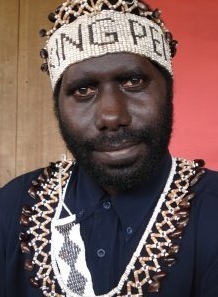

Those commendable souls who frequent this space may have noticed Microkhan's recent obsession with Papua New Guinea. This is by accident more than design, I assure you; the endlessly fascinating linchpin of Oceania simply has a lot going on these days, to the point that it has become a topic of much conversation in America's halls of power.

Those commendable souls who frequent this space may have noticed Microkhan's recent obsession with Papua New Guinea. This is by accident more than design, I assure you; the endlessly fascinating linchpin of Oceania simply has a lot going on these days, to the point that it has become a topic of much conversation in America's halls of power.

Expect Papua New Guinea's name to become ever-more prominent in Western circles, due to the possibility that the long-shuttered Panguna copper mine on the island of Bougainville may finally be reopening. One of the richest mines in the world in terms of reserves, Panguna closed down 22 years ago, amidst a supremely violent conflict between a Bougainville liberation movement and the PNG government. Now that conflict has simmered down, and key power players on the island seem willing to make peace in exchange for a cut of the mine's future revenues. Needless to say, both the U.S. and China are keenly interested in this development, as they battle each other to be first in line for the world's mineral wealth.

But Panguna's reopening is no foregone conclusion, as there are remnants of Bougainville's insurgency who are unlikely to get on board with whatever plan emerges. Chief among these is Noah Musingku, who calls himself King David Peii II and clams to rule a royal kingdom on Bougainville. Though commonly dismissed as a con artist, Musingku strikes me as something more irrational—a man who, though certainly interested in bilking investors out of money, earnestly believes he can reinvent Bougainville as some sort of utopia. Exhibit A in this lunacy is his ongoing effort to get Bougainville to ditch the Grigorian calendar in favor of one of his own design. As he explained in a speech last year:

Let me summarize my short speech by giving a brief explanation of the new U-Vistract calendar system. Many of you still do not seem to understand our calendar system although we are already in the midst of its third phase. The names for the 12 months were taken directly from the Book of Revelations Chapter 21. There are 12 foundational stones of the New Jerusalem City. The first month is Jasper, second is Sapphire, third is Agate, fourth is Emerald, fifth is Onyx, sixth is Carnellian, seventh is Quartz, eighth is Beryl, ninth is Topaz, tenth is Chalcedony, eleventh is Turquoise, and twelfth is Amethyst.

The first day (Lightday) falls on Wednesday of the conventional calendar. Second day (Skyday) falls on Thursday; third day (Plantsday) falls on Friday; fourth day (Solarday) falls on Saturday; fifth day (falls on Sunday; sixth day falls on Monday; seventh day (Restday) falls on Tuesday…

The UV calendar starts in the month of Jasper (July). Here in Siwai district where the UV system originated/is headquartered, the word 'year' is called 'Moi' in our local tongue. Eg. If you are 30 years of age you are said to have '30 Moi '. This year is 2010 AD. In the Siwai /Motuna language we would say "this Moi is 2010 AD". The word for Moi is derived from the Siwai word for "Galip Nut" tree which bears fruit every year in June/July depicting a new year. A year or Moi in Siwai/Bougainville therefore, begins in the month of July (Jasper) and ends in the month of Amethyst (June).

You can download the whole calendar here, if you're so inclined. Suffice to say, rulers who have attempted to make arbitrary changes to the calendar have not fared particularly well over the long haul. I'm thinking of the folks behind the French Republican Calendar and, more recently, the revolting Turkmenbashi. A wise man accepts that certain innovations have lasted for a reason, even if said innovations were created by a detested "other." Plus the small psychological benefits of showing the world your mastery over time surely pale in comparison to the drawbacks of being out of temporal sync with every source of capital on the planet.

In any event, have a nice Lightday today, which I believe falls in the month of Chalcedony.

(Image via Ilya Gridneff)

March 22, 2011

Scrolls and Combinations

Apologies, but squeezed for time today—have to bolt early to record a segment for Here & Now, as well as arrange a trip out to East Texas for next week. A classic above to tide you over, as you surely count the minutes 'til tomorrow's post about the new Great Game and the madness it's inspiring.

March 21, 2011

A Pocketful of Eels

Modern slang is full of gastronomical synonyms for money: dough, bread, cabbage, cake. Notably absent from the long list, however, is a foodstuff that once actually functioned as a form of currency: the humble eel, a traditional English delicacy often served in jellied form. Nine centuries ago or thereabouts, eels were more than just a form of sustenance for the inhabitants of post-Norman Conquest England; they were a way for vassals to pay their lords. The authors of 1906′s The History and Law of Fisheries explain:

Eels at this period were considered the choice fish, and throughout Domesday Book we continually find this rent of eels as rent of fisheries, e.g. Evreham (Bucks), "De iiij piscariis 1,500 eels et pisces per diem veneris ad opus prepositi ville"; Medmenham (Bucks), "De piscar mille anguillas," and in this county the rent or value of all the seventeen fisheries is returned in eels. The case is the same in Cambrideshire. In Hertfordshire all the rents or values of fisheries are in eels…In Kent we find rents in eels and rents in money for fisheries…In Northamtonshire there is no mention of any fishery, but many returns of mills valued and money and eel rents.

English waterways no longer teems with eels, of course, an environmental mystery that greatly upsets conservationists. But it is not scarcity that seems to have diminished the eel's central position in the English diet (not to mention English economics); there are plenty of farmed eels to be imported from Southeast Asia, and the the eels that are harvested domestically are mostly exported to the European continent. The eel's value to England declined because tastes changed, so that the slithery fish is now considered somewhat revolting by the nation's majority.

Why, then, do food habits—and even food taboos—change so drastically over the centuries? It's no secret that our affinity for certain foods over others doesn't have much grounding in logic. But we do drift toward foods that we regard as commensurate with our inflated image of ourselves. Eels were the mainstay of England during some truly rough times; once prosperity arrived with the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, people no longer wanted to eat what had sustained their less fortunate forbears. Beefsteaks were the right food for the growing bourgeoisie, and so the flesh of cows became the nation's go-to dish.

One must wonder, though, whether the staple meats of today will someday be looked back upon in the same manner that most English now regard the eel. Will hamburgers be reduced to carnival fare, much like jellied eels in Brighton?

(Image via sallysue)

March 18, 2011

Made in America

I somehow went almost an entire month without pimping , which appears in the March issue (alongside Joel Johnson's excellent cover story on the Foxconn suicides). The piece is a deeply reported essay that tackles a tricky business proposition: For companies that make products out of atoms, does manufacturing in China and other low-cost countries still make sense?

The answer depends on where your firm exists in the economic food chain. As I make clear in the story, I have no expectation that that iPad 3 will be made in the U.S.A.; Apple and other titans of industry have the muscle to make Chinese outsourcing work in their favor. But the equation is a lot muddier for smaller companies—"the innovative guts of America's technology industry," as I term them in the piece. Though American manufacturers still can't compete on price alone, the math is evening out to the point that smart companies are carefully weighing the pros and cons of staying home. And the biggest pro, of course, is the ability to control quality:

"If you're a huge company like Apple, you can get the whole factory to work for you," says Paul King, founder of Hercules Networks, a New York company that makes charging kiosks for mobile devices. "You can put your own process in place, you can have your own quality control. But without that kind of power, you're just another customer, and they don't really care." King cycled through three Chinese factories from 2008 to 2010 before giving up on offshoring due to persistent manufacturing errors—LCDs that winked out after six months, lights that broke when tapped even gently. The quality woes have disappeared now that Hercules is making its kiosks in the US, King says, and the company is thriving.

To deal with their production backlogs, many Chinese factories have started subcontracting work to facilities located in the center and western areas of the country, where labor costs are cheaper than on the industrialized coasts. But this usually makes the problems even worse. "They'll subcontract your work without providing the subcontractor with the same training that you provided to them," says George T. Haley, a professor of industrial and international marketing at the University of New Haven who specializes in Chinese business. "Then all of a sudden, your quality assurance goes all to hell."

On a personal note, this piece grew out of some of the Grand Empress's experiences manufacturing lingerie abroad. I've seen firsthand how production delays and quality flaws can set back a young business, often at the worst possible time. As it turns out, Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson was on the same wavelength; his side company, 3D Robotics, now manufactures in the U.S., and couldn't be happier with its decision. We both felt there was a story here, and plenty of lessons to be learned for American start-ups.

If you have even the vaguest interest in the business realm, I hope you'll check out and offer some feedback in comments. Unlike the typical Microkhan fare, there is no mention of Papua New Guinea, livestock management, or pyramid schemes. But that's not necessarily a bad thing.

(Image of Diego Rivera's River Rouge Mural via dfb)

March 17, 2011

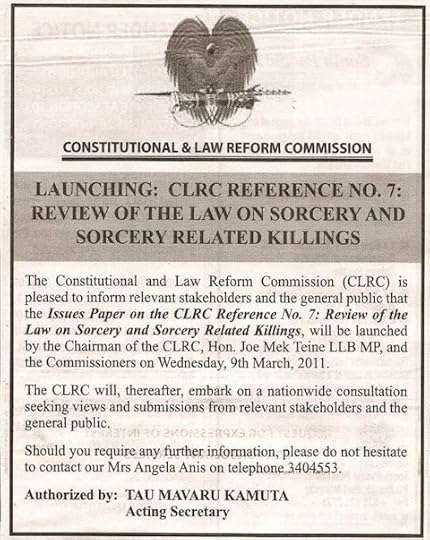

Hocus Pocus, Cont'd

I've previously written about the continued existence of anti-sorcery laws in the Vanuatuan penal code, so I felt compelled to post about the current debate in Papua New Guinea over similar statutes. The PNG government has grown increasingly alarmed over a rash of murders linked to beliefs in witchcraft:

In Papua New Guinea (PNG), the law on sorcery and sorcery related killings is being reviewed in an attempt to either repeal the Sorcery Act or make amendments to the Act by Parliament to make it more enforceable, and to help courts of law deal appropriately with such cases.

This is because sorcery and its related killings have escalated recently, and needs to be addressed as part of the law and order problems in the country.

Yesterday, Joe Mek Teine, Chairman of the Constitutional and Law Reform Commission (CLRC) which is tasked to collect information to create laws, described sorcery and sorcery related killings as a "dreaded disease" that needs to addressed, contained and regulated because it is eating into the fabrics of society.

Mr. Teine is also the Member for Kundiawa/Gembogl in the Chimbu Province, where this issue is part of their lives, and where, according to him, people have now lost the respect of the rule of law.

There are some fascinating aspects of legal philosophy that come into play here. Sorcery by itself is bunk, of course—you'll never convince me that its practitioners actually possess any supernatural powers. But it's clear that significant portions of PNG's population believe in the practice, to the point that they regard the murder of suspected witches as a form of self-defense. To reduce the number of slayings, then, the government may need to toughen penalties against what is, in effect, an imaginary pursuit.

I actually doubt that constitutional change, even if backed up by strict enforcement, can eliminate centuries' worth of folk tradition. The only real cure for this irrational ailment is the introduction of knowledge, and that must be a genuine grassroots effort.

(Image via David Wall)

March 16, 2011

Hydrofoil Engaged

If I don't get some serious writing done on my behind-schedule Wired feature today, I fear that all will be lost. Wish me luck, and brace for tomorrow's post about gambling in the highlands of Papua New Guinea.

March 15, 2011

The Exclusion Zone

Having grown up in fear of nuclear catastrophe, the post-earthquake turmoil at the Fukushima reactors has really knocked me for a loop. From the moment the plants' administrators started issuing mealy-mouthed explanations about the situation, I knew that disaster was imminent. The big question now is not only how much radiation will blow toward Japan's major population centers, but what will become of the area around the plants. Land is an incredibly precious resource in Japan, given its relatively tiny size and large population. Let's assume that, whether by official edict or mere consumer prefer, a terrestrial semi-circle behind the plant becomes devoid of inhabitants for several years. Let's also assume that the radius of this semi-circle is 30 kilometers, equivalent to that of the "exclusion zone" around Chernobyl. That comes out to around 1,413 square miles, or roughly 1 percent of Japan's total land mass. (No, I'm not controlling for national parks, inland lakes, and other variables—go with it.) In the American terms, the equivalent would be roping off a piece of property the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined (plus a few hundred miles more).

It's heady stuff to contend with, but I've found some comfort by thumbing through Haruki Murakami's Underground, one of my all-time favorite works of non-fiction. An oral history of the Tokyo gas attacks of 1995, Underground provides a slew of tiny moments that attest to the Japanese public's ability to cope with the unthinkable. I've previously written about the subway attendant who took time to fix his tie and hair despite suffering the ill effects of sarin; now I'd like to turn your attention to the recollections of an accountant whose daily ritual once consisted of buying milk in Shinjuku. Nothing, it seems, could keep him from that appointed task on the day of the attacks:

It was around Yotsuya Station I first felt sick. My nose ran all of a sudden. I thought I'd caught a cold, because I started to feel empty-headed, too, and everything before my eyes grew dark, like I had sunglasses on.

At the time, I was scared it was some kind of brain hemorrhage. I'd never experienced anything like it before, so I naturally thought the worst. This wasn't just a cold; it was a lot more serious. I felt as though I might keel over any minute.

I don't remember much about the others in the car. I was too concerned about myself. Anyway, somehow I made it to Shinjuku-gyoemmae and got off. I was dizzy; everything was black. "I'm done for," I thought. Walking was a terrific struggle. I had to grope my way up the steps to the exit. Outside it might as well have been nighttime. I was in pain, yet I still bought my milk as usual. Strange, isn't it? I went into the AM/PM store and bought some milk. It didn't even occur to me not to. Thinking back on it now, it's a mystery to me why I'd buy milk like that when I was in such agony.

Actually, I sort of get it. Routines serve an important function—they're evidence that all is normal. And when things go awry, you try to stick to that routine to convince yourself that the chaos around you is an illusion, that you're still in control. Such a strategy has little chance of working on an individual level—this poor accountant collapsed soon after purchasing his milk. But if an entire population commits to continuing to go through the motions of daily life, however difficult, virtually any catastrophe can be overcome.

March 14, 2011

The Ultimate Tribute

I just split my morning between two fruitless tasks: the first an investigation of pending nuclear projects in the developing world, the second an attempt to understand naming conventions in the world of cattle breeding. My curiosity about the latter issue was piqued by news of a bull auction in North Platte, Nebraska, where bovines with such tongue-twisting names as SLGN Copperlass Tiara 7101T X SLGN Stockman 632S will soon change hands. I feel like there must be some method to the naming madness, but I don't have nearly enough time to put in the proper research. Perhaps later in the week…

I did, however, run across this nifty breakdown of Estonian cow names. Good to see that our dairy-farming friends in the Baltics have a sense of humor about their herds:

In all, 7,161 cow names are listed. The uninspiring but solid "Mustik", which translates roughly as "black cow", comes out on top, accounting for well over half the total. Other popular choices include common Estonian female names, such as Ursula, Piret and Kadri.

Other monikers exhibit the "unique" Estonian brand of humour. Some 205 cows go by "Keku", meaning someone who is vain. Thirty-five are named "Mammut" (mammoth). Whether by accident or by design, Estonian celebrities are also accounted for. The name "Kiku" appears 438 times on the list. Besides being a slang word for baby teeth, it's also the nickname of Olympic skiing star Kristiina Shmigun.

I will not rest until a cow or bull bears the name Microkhan. That is truly the only real metric for success for these days.