Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 52

January 12, 2011

Where the Gaudy Wheels Went

I'm a few months late in noting a milestone in American cult history: the 25th anniversary of the collapse of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh's commune in Oregon, after his followers' unsuccessful attempt to tilt a local election by tainting some local salad bars. Though I was still in grade school when this all happened, I have vivid memories of the 60 Minutes exposé that showed the commune's orange-clad denizens lining up to greet their leader as he trundled by in one of his 90-odd Rolls-Royces. Even at that young age, I could tell that something was amiss. The residents of Antelope, the Oregon town that Rajneesh's disciples tried to take over, certainly agreed; they considered the cultists to be invaders, and celebrated the commune's disintegration in a fashion typically reserved for military triumphs.

When the cult finally did fall apart (at least on these shores), there was plenty of detritus to sift through. As the trailer for the Swiss documentary Guru makes clear, the Oregon commune boasted considerable stockpiles of both cash and weapons; the settlement's police, euphemistically known as the "Peace Force," all brandished late-model Uzis, for example. But the Bhagwan's most visible asset was his Rolls-Royce collection, and it became an object of desire for a Dallas auto dealer named Bob Roethlisberger—as well as a footnote in the massive savings and loan crisis of the 1980s. An old Texas Monthly story has the goods:

Three days before Thanksgiving of 1985, Dallas luxury-car dealer and Sunbelt Savings client Bob Roethlisberger landed in a private jet at Rancho Rajneesh, Oregon. The ranch was home to the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and Roethlisberger had come to the remote desert community to buy more than seventy cars from the Bhagwan's Rolls-Royce collection. It would be a difficult deal to finance, because the final sticker price for that many exotic cars would run into the millions. Selling the cars would be equally difficult once they were purchased; 36 of them had been painted by one of the Bhagwan's staff artists, designed with peacocks and geese in flight and decorated with two-toned metal flake and cotton bolls. That many luxury cars painted in that way would be hard for any market to digest. But Roethlisberger bought 84, and the deal was financed with a note of more than $6 million from a wholly-owned subsidiary of Sunbelt Savings.

Roethlisberger did manage to sell a fair number of the cars, but not nearly enough to pay back his debt obligations. (He died in April 1986, at the age of 40.) Among the vehicles he was unable to unload was a green-and-gold-lace number with teargas guns secreted beneath the fender. Here's to hoping that it would up in the hands of someone who could appreciate its bizarre lineage.

And by the way, if anyone knows how I can see Guru here in the States, please advise. I'm especially keen to hear the tale of the former Ma Anand Sheela (now Sheela Birnstiel), who was either the Bhagwan's Lady Macbeth or his convenient scapegoat. She now runs a couple of nursing homes in Switzerland, which is presumably how the Swiss filmmakers got access to her.

January 11, 2011

Crumbs on the Table

Running late on a monthly deadline, plus putting the finishing touches on the soon-to-drop Jazz Age yarn. Back tomorrow with some commentary on gang life in Port Moresby. Or perhaps some commentary on the mystery of Ma Anand Sheela.

January 10, 2011

A Disease of Special Knowledge

My line of work has brought me in contact with more than a few schizophrenics over the years, both as story subjects and as correspondents. I've become quite familiar with the seemingly impenetrable logic by which such people try to make sense of the world, and how their off-tangent worldviews occasionally lead to the commission of terrible acts. I have great sympathy for those who are cast adrift in their own delusions; as the schizophrenic mathematician John Nash once observed, the men and women who suffer from this disease do not view themselves as ill, but rather as lucky souls who've been blessed with "special knowledge" about the world.

My line of work has brought me in contact with more than a few schizophrenics over the years, both as story subjects and as correspondents. I've become quite familiar with the seemingly impenetrable logic by which such people try to make sense of the world, and how their off-tangent worldviews occasionally lead to the commission of terrible acts. I have great sympathy for those who are cast adrift in their own delusions; as the schizophrenic mathematician John Nash once observed, the men and women who suffer from this disease do not view themselves as ill, but rather as lucky souls who've been blessed with "special knowledge" about the world.

I though of Nash's quote while trying to process Saturday's tragic events in Tuscon, which were obviously the handiwork of a schizophrenic young man. Vast seas of digital ink have been spilled in an effort to identify Jared Lee Loughner's politics, but I think that's ultimately a mug's game. He appears to have much less in common with past political assassins than he does with Nathan Gale, the schizophrenic former Marine who killed the great guitarist Dimebag Darrell Abbott in 2004. The motives of both killers will never truly make sense to the rest of us, because we will never have first-hand access to the deluded realms in which these two men lived. Gale, for example, had a fixation on Abbott, to the point that he believed that the musician was stealing lyrics out of his brain. My hunch is that Loughner's motives, if they're ever wholly revealed, will be similarly nonsensical—though not, of course, to him.

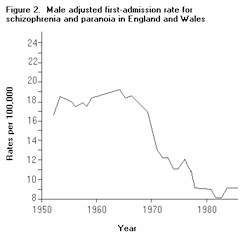

Rather than sift through Loughner's screeds in search of political clarity, my first research impulse was to look into the historical prevalence of schizophrenia. I wondered whether the Tuscon tragedy was a harbinger of things to come, a sign that incidents of schizophrenia-related violence might soon be on the ascent. But my hypothesis looks to have been way off base; diagnoses of schizophrenia have actually been plummeting in the Western world, despite greater awareness of the disease's symptoms. This paper makes the argument that better care before and during childbirth has made a huge statistical difference:

Obstetric complications are related to the subsequent development of schizophrenia, the risk for people born with complications being two to three times greater than that for people born without. Complications of delivery, rather than of pregnancy, are more likely to occur with increased frequency in schizophrenia samples; and oxygen deprivation, especially owing to prolonged labor, appears to be the common denominator among these complications. In four studies cited by McNeil (1988), prolonged labor occurred in 17 to 40 percent of schizophrenia samples compared with 8 to 19 percent of control subjects.

Yet schizophrenia is an ancient disease, and one we're unlikely to ever excise through mere obstetric caution. Attention must be paid, then, to those most at risk for the malady—and, curiously, that often means migrants in big cities:

A coherent and consistent body of research has emerged in recent years demonstrating that migrants have an increased risk of schizophrenia. Two recent systematic reviews have confirmed that migrants have a significantly increased risk of developing schizophrenia (approximately

a three- to fivefold risk ratio)…

Several high-quality studies have indicated that those born in cities have approximately a twofold increased risk of developing schizophrenia, compared to those born in rural regions. As a large proportion of individuals

in the developed world are born in cities, the population-attributable fraction for this exposure is substantial (about 30%). A systematic review recently

reported that those living in cities also had significantly higher incidence rates of schizophrenia compared to those living in mixed urban–rural sites.

The bottom line is that someone needed to step in and get Loughner the treatment he so obviously needed. But as was the case with Nathan Gale, no one seemed to recognize that a man who claims to be in possession of "special knowledge" can become a monster—even though, in his own eyes, he is simply acting as nature intended.

January 7, 2011

Cindy's Dreadful Second Act

For the year's first installment of Microkhan's much-beloved Bad Movie Friday feature, I was sorely tempted to call out Cindy Crawford's disastrous attempt to evolve from model to mactress: 1995′s Fair Game, not to be confused with the recent Plame Affair dramatization of the same name. But I decided to shift course upon reading Crawford's credits and realizing that she actually went to the feature-film once more after Fair Game's flop—though she did have the good sense to do so overseas. The not-so-pretty result was Guardie del copo (Bodyguards), a slice of Italian slapstick that (to be charitable) doesn't quite translate. The clip above reels off a succession of the film's key pratfalls; a more salacious trailer can be found here, and should only be played if you're in a place where gratuitous semi-nudity won't get you fired.

You can also do a close read on Crawford's dubbed-in acting chops by watching this clip. To her credit, I kind of like the way she reels off the proper noun "Napoli." And I have to surmise that this movie does a surprisingly good job of summarizing the trashy aesthetics of Berlusconi-era Italy—a topic thoughtfully explored in 2009′s Videocracy (also NSFW, alas).

January 6, 2011

No Sense of Time

I've recently taken a lot of comfort from this Paris Review Q&A with John McPhee, in which the non-fiction master confesses that his writing remains a day-to-day struggle. (Celebrities—just like us!) But while most of the interview is dedicated to the creative process and the occasional madness it engenders, there is also this dead-on snippet about what McPhee learned from hanging out with geologists for a series of books (now collected as Annals of the Former World):

There's a line in the book: "If you free yourself from the conventional reaction to a quantity like a million years, you free yourself a bit from the boundaries of human time. And then in a way you do not live at all, but in another way you live forever." And I certainly developed this sense of time. I was fascinated by the intersection of human time and geologic time…The fact is that everything I've written is very soon going to be absolutely nothing—and I mean nothing. It's not about whether little kids are reading your work when you're a hundred years dead or something, that's ridiculous! What's a hundred years? Nothing. And everything, it doesn't evanesce, it disappears. And time goes on, and the planet does what it's going to do. It makes you think that you're living in your own time all right. It makes the idea of some kind of heritage seem touching, seem odd.

I couldn't help but think of McPhee's dose of perspective while reading this account of the Cameroonian elite's campaign against pidgin, the use of which is discouraged on many university campuses. the sign at the top of this post is part of a campaign to get Anglophone students to stop speaking pidgin, lest they fail to attain their promise in life:

The underlying message is a fairly simple one: In order to fit in, English-speaking Cameroonians must shun their inferior culture and language(s) which are obstacles to their integration into the national (read Francophone) mainstream, and gravitate towards French which is the language of access, success and power. Pidgin in particular is therefore portrayed as a language of confinement (in the "Anglophone Ghetto"), of exclusion (from "national mainstream") and of inferiority (vis-a-vis the French language).

Yet this elitist campaign only reveals its orchestrators' ignorance of the true nature of time. Do they not realize that English was once considered a sort of pidgin, a mishmash of northern European dialects that was spoken by a conquered class subordinate to a French-speaking elite?

Language, like the tectonic plates that shift beneath our plates, is a fluid thing. And though its shifts may be imperceptible to those who cannot see beyond their own lifespans, it is always fated to evolve into a melange of various sources. In that way, pidgin is actually quite futuristic—a glimpse of what might happen as English spreads and mutates after coming in contact with thousands of local dialects.

More Microkhaning on the history of pidgin here.

January 5, 2011

The Sound of St. Georges Cross

Major projects day here at Microkhan HQs, which means lots of reading up on Eldridge Cleaver's interest in juche and cold-calling retired Naval officers. I trust that you can get through the next 24 hours with the aid of MC Soom T, one of Glasgow's finest songstresses. Full interview here if you'd like to learn more about her (and have a knack for understanding Scottish accents).

January 4, 2011

Cancer Sticks in the Clink

One of my favorite economics story of the millennium is the Wall Street Journal's 2008 A-head about the use of tinned mackerel as prison currency. It's a fantastic testament to the primacy of money; even when removed from ordinary society, humans always find a way to regulate their commerce by creating tangible symbols of achievement. When I initially read the piece, I could only think of the cover of the Federal Reserve's infamous (but strangely awesome) The Story of Money comic book. The four-paneled illustration seems to be making the argument that bartering is a relic of our cavepeople past, and that currency is a hallmark of civilization.

The mackerel story surprised because it seemed to illustrate a shift in prison economics akin to America's changeover from the gold standard. Cigarettes have traditionally been the currency of choice for the incarcerated, partly because, when push comes to shove, such "money" can be consumed like a commodity. The mackerel can, too. at least in theory, but the inmates would prefer not to; the WSJ makes clear that the fishy treat is universally unbeloved in prison, and so the vast majority of cans are never popped open.

Mackerel became money after prisons started cracking down on tobacco use, but cigarettes have by no means disappeared as a form of alternative currency. The bans have simply pushed the cigarette trade deeper underground, as explained in Smoke 'Em If You Got 'Em: Cigarettes in U.S. Prisons and Jails. The paper points out that cigarettes, like gold bullion in the outside world, remain a highly prized fallback currency because, presumably unlike mackerel, they have great value beyond their functional role in the prison economy. And the official crackdown on tobacco has forced inmates to engage in riskier behavior in order to maintain their "wealth":

Just as the criminalization of cocaine and heroin gives rise to impure drugs and a scarcity of sterile drug paraphernalia, cigarettes sold on the black market are often more harmful than those sold legally and are combined with less healthy smoking practices. For instance, because rolling papers were scarce, some inmates resorted to rolling tobacco with toilet paper wrappers or with pages from a Bible. Both contain ink or dyes that are harmful when burned. Also, inmates reported removing the filters on manufactured cigarettes to increase the potency of each drag of tobacco. Furthermore, inmates who might otherwise have smoked a lower tar cigarette had little choice but to smoke higher tar cigarettes.

I'd love to have a moment to calculate the health-care costs associated with the outlawing of tobacco in American correctional facilities. My hunch is that prison officials would be better advise to regulate the market, given that bootleg cigarettes may cause long-term health problems that may eventually become the government's burden. Is there a lesson to be learned here about drug policy in the world outside the prison walls?

January 3, 2011

Bowled Over

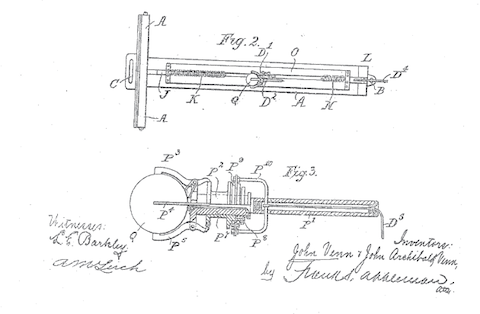

Let's begin the year by hailing the ingenuity of a man who has contributed much to both mathematics and Internet meme-ry: John Venn.

Venn is, of course, best known for concocting the elegant diagramming system that now bears his name. Aside from elucidating the fundamentals of logic for generations of schoolkids, Venn diagrams have also provided structure for countless middlebrow-brow jokes. For this achievement alone, Venn deserves a place in the organizational pantheon alongside Melvil Dewey and Edwin G. Seibels.

But Venn was far from a one-trick pony, nor one who confined his genius to the realm of the theoretical. He was also quite the engineer, and used his tinkering skills to create one of the earliest mechanical robots: a cricket bowling machine that was sort of the Deep Blue of its day and sport. The machine was rumored to have bested the top batsman on the Australian national team, largely because of the way it created baffling break.

What's odd is that, despite the early hype over the machine's ability to best human players, Venn's cricket bowling contraption was quickly relegated to the status of training device—quite like the Jugs machines that now dominate the market. I, for one, would like to see a revival of the engineering race to design a machine capable of stumping the world's best batsmen. I can only guess that this quest was abandoned once humans adjusted to the machines' limited trickery. But I refuse to believe that machines can only triumph over humans in contests of mental acuity. At some point, the robots will prove that they can triumph in the athletic arena, too. How long will that take? The answer might depend on how much human competitors are willing to modify their bodies to keep their edge.

December 30, 2010

Borne Forward Ceaselessly Into MMXI

Cutting out a little early on 2010 to prep for 2011; today's all about wrapping up loose ends, drawing up New Year's resolutions, and game-planning for what's sure to be another madcap 12-month stretch. Lots in the works, starting with my long-promised Jazz Age yarn. As always, check this space for details—or simply because you have a hankering to learn more about kabaddi, the Solomon Islands, or trends in oxen usage.

For the record, these were the most-read Microkhan posts of 2010:

May your New Year's celebration be every bit as lavish as a top-notch Tsagaan Sar party, and hope you'll continue to patronize Microkhan throughout our planet's next revolution around the nearest yellow dwarf star.

December 29, 2010

The Measure of a Story

I toyed with the idea of doing a couple of "Best of…" lists in these waning days of MMX, much as I did last year. But in the course of trying to pull together some worthy candidates from the realms of filmdom, books, and booze, I got to thinking about the criteria I was employing—at least for the works of art. (The judging of beer, wine, and whiskey is fairly straightforward.) Why, exactly, do I find some narratives more praiseworthy than others?

As I pondered that question on Boxing Day, I started in on a New Yorker piece that I'd missed: Burhard Bilger's tale of underground foodies and their affection for Dumpster diving, rotten meat, and pungent fermentation. The story's main character is a bloke named Sandor Katz, who's created quite a career out of preaching the virutes of fermented victuals. Like most pundits, Katz has attracted his fair share of virulent critics, never more so than after he once advocated for the ethical production of meat. Bilger turns the response to this revelation into the article's absurdist pinnacle:

Needless to say, this argument didn't fly with much of [Katz's] audience. Last year, the Canadian vegan punk band Propagandhi released a song called "Human(e) Meat (The Flensing of Sandor Katz)." Flensing is an archaic locution of the sort beloved by metal bands: it means to strip the blubber from a whale. "I swear I did my best to insure that his final moments were swift and free from fear," the singer yelps. "But consideration should be made for the fact that Sandor Katz was my first kill." He goes on to describe searing every hair on Katz's body, boiling his head in a stockpot, and turning it into a spreadable headcheese. "It's a horrible song," Katz told me. "When it came out, I was not amused. I had a little fear that some lost vegan youth would try to find meaning by carrying out this fantasy. But it's grown on me."

Why do I love this passage so? Not necessarily for the use of the word "flensing," though that's certainly a bonus. Rather, it's because it leaves me wanting to read a whole 'nother piece, about the vegan punk rock scene in Manitoba and the "lost youths" who gravitate toward its rules, messages, and camaraderie. What I would give for Bilger or some other great reporter to spend the next few months in Winnipeg, checking out hardcore shows in an effort to understand the peculiar sort of angst that makes the musical culture so enticing.

And that, I've decided, is the measure of a great yarn: It has to leave me thirsty for a tale about the various minor players who cross the stage. Winter's Bone achieved this, too—as soon as it ended, I lamented the fact that I'd never find out more about laconic meth lord Thump Milton. So, too, did Big Fan—I, for one, would love to see an HBO series about the life of star linebacker/coked-out asshole Quantrell Bishop.

Rather than go through a list of books and movies I dug this year, I'd like to hear from y'all about stories that left you hungering for spin-offs featuring minor characters. But, please, no Joanie Loves Chachi jokes.