Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 53

December 28, 2010

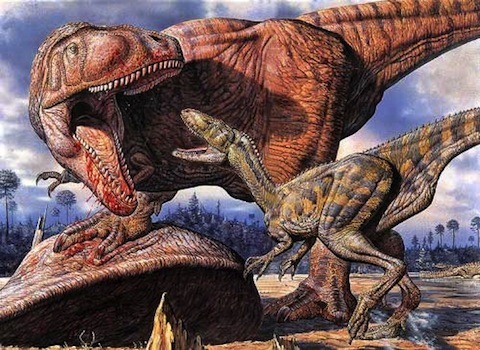

The Fine Art of Terrible Lizards

On Christmas Night, the ingestion of too much fine red wine led the Grand Empress and I to spend a pleasant few minutes researching Thrinaxodon, one of the many Therapsids to be found in mankind's evolutionary tree. We were intrigued to find great disagreement on what this critter looked like; due to a paucity of fossil evidence, artists have been free to imagine the mammal-like reptile as either a lovable otter-like creature or something akin to a slimmed-down wolverine. Will we ever be able to determine which artistic interpretation is closest to the way Thrinaxodon really looked?

Sealed inside by the snow on Boxing Day, I decided to do a little digging into the creative process for paleoartists. I didn't have to dig very deep, fortunately, thanks to this great collection of interviews with contemporary masters of the form. Lots of great stuff here, including links to the works of such paleoart stars as Mark Hallett (see above) and Mike Skrepnick. But what I really zeroed in on was the Q&A with Mark Witton, who did an excellent job of explaining what makes a piece of paleoart worth your while:

The success of a palaeoart piece is determined through both its scientific and artistic merit, and the science is often the easier part to get right. With a complete skeleton, we can probably assume the rough body contours of an extinct animal to a reasonable degree of accuracy. Our record of soft-tissues is improving markedly, too, so even the detailed external anatomy of some long-dead animals can be restored in some detail. The science of palaeoart, then, simply relies on paying attention to the data available on given taxa: proportions, soft-tissues where known, footprint and trackway data and whathaveyou. We're going to have some of this data superseded by other finds later, but we can definitely be 'correct' when we're putting paint on the canvas.

Thing is, anyone who can use a ruler and a pencil can bring this information together and knock up a basic reconstruction of an extinct animal: in some respects, it almost has more in common with technical drawing than it does artistry. It has, indeed, led to the Dreaded Recurrence of Flat Views flowing through a fair amount of palaeoart: there's a whole bunch of palaeoart images with dead-on lateral or anterior views of animal heads or bodies. Inspired, I suppose, by Paul-esque reconstructions of skeletons in multiple views, they look more like technical reconstructions dropped on top of painted landscapes than natural scenes. They're great bits of art, mind: they look like 2D cutouts arranged on a stage, with even the backgrounds having a similar theatre-set feel to them, but they're too stylised to persuade the viewers, even if only in a minor way, that the artist was actually there, witnessing these ancient scenes himself. This is where the artistic prowess of the best palaeoartists comes in: they take the schematic technical work of scientists and turn it into something dynamic and vital. Something composited into a realistic environment and interacting convincingly with other animals. Purely artistic skills – a sense of composition, use of shading, the position of the PoV, the colour palate – are what gives the picture presence and really grab the imagination of the viewer. Even the most striking, fantastic-looking critters will lose their effect in artwork if they're poorly lit, positioned awkwardly within the frame or postured in an obscuring way. In this respect, palaeoart is identical to other forms of representative art: the artist needs to understand the form of their subject, how they would appear in a realistic environment, and then wrap it all up in a dramatic, stylish way. Think about John Gurche's work, for instance: his knowledge of form, use of light and depth of field makes it look like he's photographing enormous animals from 75 million years ago: it's like he's there, man. If you can trick your audience into that (and his work did, indeed, do this to a younger version of myself), you know you've done your job.

As someone who was deeply influenced by the dinosaur art of Rudolph Zallinger as a young'un, it's tough to realize that Microkhan Jr. will grow up with a very different mental picture of what ancient animals looked like. And that's due not only to changes in paleontology, but also to the rapid evolution of paleoart. The big question, then, is how the artists influence the scientists—there's just no way that a paleontologist can avoid being influenced by the painting and drawings that first got him or her interested in the field.

December 24, 2010

The Cure for Workaholism

Can't believe I'm about to do this, but actually gonna take a few days off starting right now. Big plans for the holiday weekend: ice skating, Staten Island, and Ayinger Celebrator (not necessarily in that order). I leave you with a comically inappropriate snippet from Yogi's First Christmas, arguably the greatest ursine-themed holiday movie of all time. Given Boo-Boo's tender age, Cindy is definitely flirting with some serious violations of state laws here. Also, her crush on Yogi is pretty inexplicable. The dude's woefully out-of-shape (thanks to his twin obsessions with hibernation and picnic baskets) and pretty darn lazy—though, granted, he has excellent taste in hats.

Raucous holidays to all, and see you back here in a bit.

December 23, 2010

Saints and Sinners

In the midst of researching an upcoming post on the cigarette economy in prisons, I came across this image of juvenile prisoners in Russia. I was struck by the extreme youth of these convicts, and thus motivated to look a bit more deeply into how Russia handles criminals who've yet to become adults. As I expected, the situation ain't a happy one—juvenile offenders are often stashed in the "junior wings" of maximum-security prisons, where they come under the influence of hardened criminals.

This grim policy inspired painter Yana Payusova to do a series on Russia's young convicts, whom she renders as Orthodox icons. The boys in her paintings are lifted from black-and-white photographs that she took while visiting several juvenile detention facilities. She talks about the experience of capturing those images here:

I was truly shocked when I saw the teenage convicts in person. When we arrived they were in their cells, mostly sleeping and passing time. They were brought out in front of us into the main hallway for lineup. I was expecting to see tough guys and intimidating criminal types, but instead I saw a group of scrawny, pale, shaven-headed young boys, many of whom were covered in warts and sores. I knew that all of them had to be ages 14 to 21, but the majority seemed like they could not be older than twelve (as I later learned, an indication of malnourishment in childhood). Many had tattooed limbs and torsos. A few of the tattoos were masterfully executed, but most were crude amateur drawings. Many of the tattoos were grossly infected. Ironically, the tattoo designs displayed harsh arrogance and aggression, which was markedly missing from most of the boys' faces. Also, many of them spoke 'blatnaya fenya' (special cryptolanguage used among criminals) partially out of habit and partly to show off and flaunt their connections to the criminal culture.

Definitely check out the whole series; this one is a personal favorite.

Hope to have the cigarette-economy post wrapped up next week. And I'll probably also have to do something on blatnaya fenya, too.

December 22, 2010

Packing Up the Turtle Doves

Taking a day to wrap up pending projects, so that I can unplug for 96 hours starting on Christmas Eve. Stevie Wonder will see you through; a great remix of this tune leads the latest installment of Microkhan fave Fresh Produce.

December 21, 2010

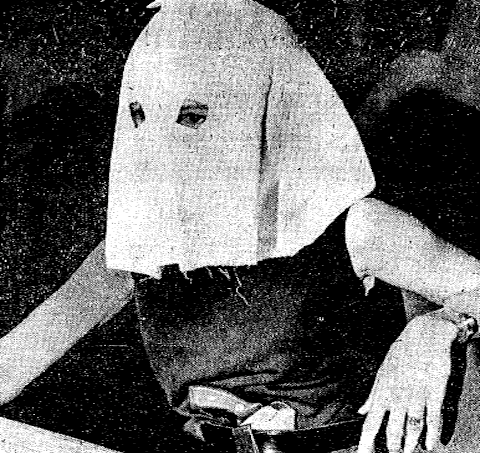

Theater of the Absurd

The hooded lady above was not a bandit, but rather a New York City detective who worked the 21 Jump Street beat in the early 1970s. Kathleen Conlon earned her gold shield after surviving a scary incident in the Bronx: While working on an undercover narcotics unit, she was dragged into an alley, assaulted, and robbed. One attacker placed a gun to Conlon's head and pulled the trigger twice, but the .25 misfired both times. After that, the NYPD reckoned that the young policewoman was ready to explore the drug scene in the New York City school system.

A year later, Conlon made a masked appearance in Congress, testifying before the House Select Committee on Crime. Obviously blessed with a flair for the dramatic, Conlon completed her outfit with a .38 on her hip—not to mention a saucy short-sleeved shirt, still a rarity among those who appear on Capitol Hill. (Even that blunted lifeguard who testified about the Jack Abramoff scandal opted for a classic shirt-and-tie look.) Bewitched by her showmanship, the committee didn't seem to bother pressing Conlon about the absurd tales she shared:

She told of students buying, selling and using all forms of drugs in the schools and said many teachers actually "condoned" the use of narcotics in school. At some of the schools she was in, Miss Conlon asserted, 90 per cent of the students were on drugs of one form or another…

The detective said that late in 1969, when she was working at Springfield Gardens High School, one student would sell $500 worth of drugs before school in the morning, $500 worth at lunchtime, and still more when the second-session students arrived in the afternoon.

At this school, in a middle-income community, students would regularly "nod out" in class and be ignored by the teachers. One teacher, she said, told a troublemaker to "go out and take something to quiet you down." She said three-quarters of the students there used narcotics and as many as 50 per cent of the students were on heroin.

That last statistic caught the attention of a skeptical New York Times reader, who responded the following week:

As a former faculty member at Springfield Gardens (who was there during the time she served as an undercover agent) I can assure you that this is patent nonsense. "Emphatically, yes!" to the question of whether there are narcotics users at S.G.H.S. and indeed, whether there is a large-scale narcotics problem among New York's students, but half of the student body?

If this were true, one might expect the daily attendance to reflect this figure, the graduating classes to have shrunk to minuscule size and education to have come to a standstill. Such is not the case.

In some ways, Conlon's showmanship makes me nostalgic for an era of more exciting Congressional testimony. There used to be more theatricality to the endeavor, particularly from the side of the testifiers' table. Mark McGwire talking about his allergy to the past doesn't quite compare to the whole Joseph Valachi affair. But the fact that Colon was permitted to hyperbolize at will hints at a problem that continues to this day: The willingness of politicians to accept half-truths if they're packaged nicely, and if they appear to be in the service of some greater moral good.

I have no idea what happened to Conlon after her Congressional appearance, as he basically disappears from the public record thereafter. If anyone knows, please advise—I'd be interested to know where her career led her. I wouldn't be surprised in the least if she ended up as a cop-show consultant.

December 20, 2010

Battledrome

I've previously written about the odious racism of the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, where various peoples from around the world were displayed like zoo animals. For the most part, these folks were asked to inhabit ersatz villages, so that their clothes and customs could be gawked at by paying customers. But some of the Fair's international participants were instead cast as actors in a massive recreation of the Anglo-Boer War, which had concluded just two years prior. It was an enormous production, as a contemporary paper noted:

I've previously written about the odious racism of the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, where various peoples from around the world were displayed like zoo animals. For the most part, these folks were asked to inhabit ersatz villages, so that their clothes and customs could be gawked at by paying customers. But some of the Fair's international participants were instead cast as actors in a massive recreation of the Anglo-Boer War, which had concluded just two years prior. It was an enormous production, as a contemporary paper noted:

The Anglo-Boer war exhibition at the World's Fair, St. Louis, in which General Croje is the leading figure, is the largest and most realistic outdoor entertainment ever seen. It is as though 20 acres of South frica had been carried across the Atlantic and dumped down at St. Louis…

A representation of the capture of Colonel Long's guns at Colenso is shown. Men and horses drop until hardly one is left standing, deeds of heroism are performed, stray horses gallop wildly about. At last, with a loud cheer, the Boers, led by General Ben Viljoen, rush from rocks and kopjes, and the day is won…

The entertainment is a military tournament on a large scale, and one is brought face to face with war and all its horrors.

I was initially struck by the extreme oddness of this production, given how conflict's freshness. It's one thing for Civil War reenactors to take part in mock battles that are well over a century old, quite another to recreate a war that had ended two years earlier. Vietnam War reenactment might be a better comparison, but that pastime didn't start until a good decade after the fall of Saigon. And it's never been put on as a mass entertainment; instead, it is largely for the enjoyment of the participant themselves.

One might be tempted to say that folks of the early 20th century were more inclined to view warfare as spectator sport, but I'm not sure that's what's going on here. We have to keep in mind that in the pre-newsreel era, Americans who weren't directly involved in warfare knew about the terrible practice solely through the written word (and, perhaps, the oral histories passed down by Civil War vets in their families). Think about that for a second—you're fully aware that much of world history has been shaped by violent conflict, but you have never witnessed even a close approximation of the phenomenon. Curiosity is only natural.

There is obviously something a wee bit unsettling about the notion of turning recent conflict into theater—tough to envision folks lining up to see the 2008 campaigns in Afghanistan recreated in a major American city. We turn instead to film and television to get our warfare fix, but the focus there is now more on the interior lives of soldiers than the logistics of battle. That's partly because contemporary warfare is chaotic, but also due to the fact that we've developed more empathy for the men and women who pay the price for officers' orders—at least if those men and women are wearing friendly uniforms. We want to know how they cope with an experience that we understand to be shattering in so many ways; back in 1904, spectators were far more interested in the grandeur of General Cronje's uniform.

December 17, 2010

As Dry as the Sahara

Absolutely nothing left in the tank today—not even enough mental bandwidth to squeeze out a Bad Movie Friday. Spent the bulk of yesterday recording the audio version of my upcoming Jazz Age yarn, an experience that has given me new respect for voice actors. You try saying "Critics and compatriots rarely stinted on superlatives" without tripping over the alliteration—not an easy feat, as I found out the hard way.

Outro-ing for the much-needed weekend with a gem from the best guitarist ever to emerge from Western Sahara. See you next week for the joyful run-up to the holidays.

December 16, 2010

The Only Way to Win is Not to Play

The fundamental premise of the American economic system is that competition is healthy. By extension, we generally assume that the greatest men and women are those in whom the competitive spirit burns brightest—individuals with "fire in the belly." These are the people who take play as seriously as work, and thus descend into deep depressions upon losing games of Monopoly or racquetball. We hail this mindset—how many 60 Minutes interviews with captains of politics or captains of industries have revealed that the subject absolutely hates to lose at anything?

But what about those who shy away from contests of skill because they find competition off-putting? Are they doomed to lives of mediocrity? I started thinking about this issue while reading this vintage New Scientist piece about the psychology of chess. The article includes a quote from Albert Einstein, who apparently didn't enjoy the sport's competitive element:

I always dislike the fierce competitive spirit embodied in that highly intellectual game.

As you might expect, Einstein was actually a pretty decent chess player, achieving a rating of 1800. (Check out a summary of his 1933 match against J. Robert Oppenheimer here.) But he insisted that the game brought him little to no enjoyment, and was one of the last things he liked to do with his free time:

Chess grips its exponent, shackling the mind and brain so that the inner freedom and independence of even the strongest character cannot remain unaffected.

As someone who enjoys solitary pursuits, I think that Einstein was on to something here. One can still achieve without engaging in constant competition. In fact, I'd wager that certain types of minds benefit by stepping away from competition for long stretches. Just because you don't spend every waking moment trying to embarrass your fellow humans at games doesn't mean you can't contribute anything to the grand American experiment—right?

December 15, 2010

Closing in on Dawn

Mere hours away from this killer Wired deadline that's been vexing me since last week, so please endure one last day of meh-ish posting. There's only so much mental bandwidth to spare, alas, and most of what I've got is currently dedicated to figuring out a way to end this piece. (I'm playing with several variation of that oh-so-classic kicker: "Only time will tell.") I thus give you a true sonic rarity: Africa's cover of "Louie Louie," which I believe actually surpasses the original. It's off of this little-known album, which also includes excellent takes on "Light My Fire" and "Paint It Black."

Back soon with real content. In the meantime, enjoy the music and maybe, just maybe, take a sneak peek at one of the long-rumored "major projects" that I sometimes mention in this space. Really excited about that one—should go live in early 2011. Rest assured, I'll be keeping y'all posted—as well as be offering bonus material in advance of the debut.

December 14, 2010

The Best Job in Show Business

Still cranking on this Wired deadline, so I can only offer you a pittance this morning. But what a pittance—a tribute to the Morris Day, a few hours too late to celebrate his 53rd birthday. Aside from absolutely owning Purple Rain, Day is responsible for one of the greatest on-stage gimmicks ever: Checking his reflection in a gilded mirror, to ensure that he is maintaining ultimate prettiness. Wielding that mirror seems to be the primary reason that Jerome Benton is part of the band; he doesn't actually play any instruments, though he is a rather excellent dancer. Given his role in The Time, Benton reminds me of another sideman whose contributions are more theatrical than musical: Bez, the maracas-shaking Happy Mondays oddity who is a master of exhibiting uninhibited joie de vivre. Benton is an infinitely better dresser, though.