Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 57

November 1, 2010

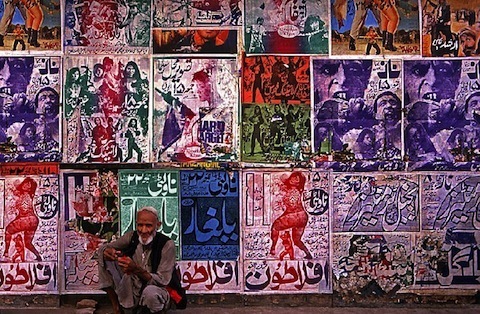

A Perfect System, Soaked in Blood

Though my gambling amounts to little more than the occasional hand of $5 blackjack while in Vegas, I'm fascinated by the work of oddsmaking. It takes a special kind of genius to create a system in which the house will always win in the long run, though by just enough to preserve the game's entertainment value. Adding to the challenge is that constant interference of players who constantly probe these systems for weaknesses—if you're not careful enough when writing the house rules, a bunch of math whizzes from Miami are bound to take you to the cleaners.

But there needn't be a wizard behind the curtain in order to develop "perfect" betting systems. This has happened organically for centuries, presumably through years' worth of trial and error. That's the lesson I took away from reading Clifford Geertz's Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight, a true classic of anthropology. In attempting to describe how this bloody "sport" reinforces Bali's strict social hierarchy, Geertz describes the various types of wagers that are placed on cockfights. These basically break down into two categories: "center" bets, which are between the bird owners and are governed by official rules, and side bets between spectators, which are completely unregulated. Geertz found that despite this wagering chaos, the center and side bets worked in tandem to create the sort of system that Vegas casinos consider ideal:

The higher the center bet, the more likely the match will in actual fact be an even one. In a large-bet fight the pressure to make the match a genuinely fifty-fifty proposition is enormous, and is consciously felt as such. For medium fights the pressure is somewhat less, and for small ones less yet, though there is always an effort to make things at least approximately equal, for even at fifteen ringgits (five days work) no one wants to make an even money bet in a clearly unfavorable situation. And, again, what statistics I have tend to bear this out. In my fifty-seven matches, the favorite won thirty-three times over-all, the underdog twenty-four, a 1.4 to 1 ratio. But if one splits the figures at sixty ringgits center bets, the ratios turn out to be 1.1 to 1 (twelve favorites, eleven underdogs) for those above this line, and 1.6 to 1 (twenty-one and thirteen) for those below it. Or, if you take the extremes, for very large fights, those with center bets over a hundred ringgits the ratio is 1 to 1 (seven and seven); for very small fights, those under forty ringgits, it is 1.9 to 1 (nineteen and ten).

The paradox of fair coin in the middle, biased coin on the outside is thus a merely apparent one. The two betting systems, though formally incongruent, are not really contradictory to one another, but part of a single larger system in which the center bet is, so to speak, the "center of gravity," drawing, the larger it is the more so, the outside bets toward the short-odds end of the scale. The center bet thus "makes the game," or perhaps better, defines it.

Somewhere up there, Charles K. McNeil is smiling at the genius of Balinese bookmakers. Though maybe not if he was into animal rights.

(Image via Tariq Sulemani)

October 29, 2010

Carry Your Cup in Your Hand

It felt weird leaving an abysmal Sidney Sheldon mini-series atop the blog for the weekend, so let me instead outro with a brief poem from the latest issue of Granta—one of the publication's best in recent memory. It is by the Peshawar-based writer Hasina Gul, and translated from Pashto:

We grow up

but do not comprehend life.

We think life is just the passing of time.

The fact is,

life is one thing,

and time something else.

Words to chew over this weekend, as we temporarily assume whole new identities. (I'm gonna be Darth Vader; Microkhan Jr. is gonna be Spider-Man.)

(Image via Izzet Keribar)

From the Department of the Obvious

This week's Bad Movie Friday entrant bends the rules a bit: it's actually a network mini-series, a once glorious TV genre that has sadly fallen out of favor in the modern era. Rage of Angels: The Story Continues was one of many Sidney Sheldon potboilers to appear on the small screen during the 1980s, and it possesses the same overcooked quality as the cafeteria carrots of yore. As you can see in the clip above, the writing is big on emphatic declarations uttered by gun-wielding members of the global elite. This vintage New York takedown cites some other howlers:

I will forever treasure one snide line: "I'd kill you, Margot, if you hadn't already died of face-lift poison." But it won't make up for "I gave you a son, I can't give you a home." Or "I cry for Catherine, my tiny, wounded Madonna." Or "It's strange, Adam—the places we remember best are the ones we never see." Or "I've been unfaithful to my life. I've used our love as a substitute for living." Or "What's left after tears, Jeremy?" Followed by "I don't know. Dignity, maybe."

And then:

You will think that the first fifteen minutes of Rage of Angels: The Story Continues flaunts the worst acting you've ever seen on prime-time television, but that's because you haven't watched the next three hours and 45 minutes.

Terrible acting and writing, perhaps, but you can't argue with the film's morals, as articulated in our chosen clip: It is, indeed, not right to kill the vice-president.

October 28, 2010

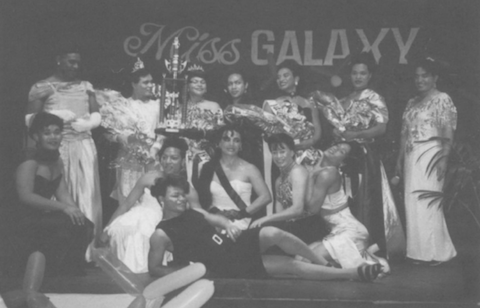

Miss Galaxy

In the course of researching the controversial career of Filipino basketball star Asi Taulava, I decided to look into the hoops scene in his native Tonga. That line of inquiry led me to this account of the sport that Tongans describe as "basketball," but really resembles something else entirely:

Basketball in Tonga is not like American basketball. It is more similar to netball which I don't really know anything about. Tongan Basketball is played on a field, there is no dribbling and the hoops do not have backboards…The field is divided in three sections with two goal areas around the hoops. The players are assigned to a section and they can only play in that section. Once a shooter has indicated that they will shoot and are in the goal area, the defense must let them shoot with no interference…It is only played by girls and fakaleiti's (semi-flamboyant to flamboyant gay guys).

That last part intrigued me, as Tongan culture has always struck me as deeply conservative—not to mention very macho. Yet that line suggests that gay men have a defined role in Tongan society, one that gives them an identity similar to that of the hjiras of South Asia.

Yet that identity has not come easily, as evidenced by the evolution of Tonga's annual Miss Galaxy pageant. This fakaleiti competition has become an international phenomenon in recent years, to the consternation of some Tongans who remember when such pageants were a cruel form of entertainment. From a great academic study of Miss Galaxy (sadly paywalled):

Fakaleiti pageants appear to have emerged in the 1970s. The early pageants probably resembled the lesser pageants of today in size and level of organization. They gradually gained notoriety, until 1991, when the first Miss Galaxy pageant was held in the capital's only international hotel. Along with increasing popularity and visibility came the greater respectability and assertiveness—an evolution that some Tongans bemoan. Finding that fakaleiti today "take themselves too seriously," some Tongans long for prior incarnations of hte pageant when "it was all a good laugh" at the expense of the fakaleiti.

Documentary footage here.

October 27, 2010

A Singer's Burden

I recently bought a bevy of vinyl off a guy in my building. He just showed up at my door with a crate full of records, which I purchased for a relative song after giving the contents only a cursory glance. Turns out there was a lot of junk in there—I am now the not-so-proud owner of two Barbara Streisand albums—but also some unbelievable gems. Among them is Esther Phillips' From a Whisper to a Scream, which I've been playing for Microkhan Jr. every chance I get. Just a classic slab of audio, and one that has led me to start exploring the underrated Phillips' full catalog.

That exploration also led me to this rare 1973 interview, in which Phillips talks about something I'd never really thought about: the emotional difficulties of performing songs that hit too close to home:

"For the first time", she says happily, "I've been able to select the songs myself. As a result, they are all things I really dig personally and many of them, like "Baby I'm for Real" and "To Lay Down Beside You" are things I've wanted to cut for years and never had the opportunity to. All the material relates to everyday life and people, and I can relate to it all myself, too."

That probably accounts for the great feel that comes across on her Kudu work but on no other recording is that more evident than the more evident that the controversial "Home Is Where The Hatred Is" from the "Whisper" LP which proved a big seller in the States when it was issued as Esther's first single for the label. Its stark lyrics are made that much more startling when one considers that the fight against drug addiction was one of the toughest problems that dogged Miss Phillips' career until she finally beat it with a spell of intensive hospital treatment.

As she put it: "Creed Taylor (from Kudu) asked me to do the song but, naturally, I went through quite a lot of emotional changes before I agreed to do it. After all, although everyone knew about the problems I'd faced, singing the song was just like being interviewed in public about it all. Yeah, I really didn't want to do it – fact is, I continually postponed recording it and it was the very last song we did for the album. I've now gotten used to the song after having sung it continually on stage, though."

I have to wonder if other recovering musicians have had similar reactions to recording confessional songs about their misbehavior. Guess I should probably read that Anthony Kiedis memoir to find out whether he broke down while doing "Under the Bridge."

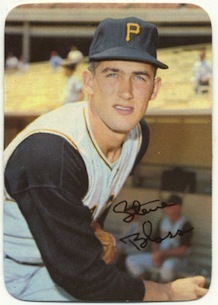

The Forgetting

I've been dealing with some mega writer's block these past few days, which has got me wondering whether it's possible for someone to spontaneously lose their most well-developed skills. That's obviously true in the athletic realm, where the dreaded Steve Blass Disease has ended more than a few baseball careers. The problem with such vexed athletes is fairly obvious, and best summarized by a quote from Bull Durham: "Don't think, Meat. Just throw." An egghead description is here:

I've been dealing with some mega writer's block these past few days, which has got me wondering whether it's possible for someone to spontaneously lose their most well-developed skills. That's obviously true in the athletic realm, where the dreaded Steve Blass Disease has ended more than a few baseball careers. The problem with such vexed athletes is fairly obvious, and best summarized by a quote from Bull Durham: "Don't think, Meat. Just throw." An egghead description is here:

Motor learning may initially rely on more explicit and prefrontal areas, but after extended practice and expertise, shift to more dorsal areas, but thinking about the movement can shift activity back to the less skilled explicit areas. Although many explanations may be derived, one could argue that these athletes show that even when years of practice has given the implicit system an exquisitely fine tuned memory for a movement, the explicit system can interfere at the time of performance and erase all evidence of implicit memory.

But how does this apply to more intellectual pursuits, in which motor skills are subordinate to less tangible assets such as creativity, tonal sense, and the comprehension of logic? Is the key to overcoming mental blocks the ability to extinguish conscious thought about process? That doesn't seem right, as creating something worthwhile—whether a piece of prose, a musical composition, or a really solid PowerPoint presentation—would seem to require lots and lots revision, and thus a degree of self-awareness that athletes (who only get one crack at each action) don't really need. But I do understand how "overthinking" can interfere with intellectual output—it's obviously detrimental to obsess over how each and every line, note, or slide will be received.

If anyone can offer advice on how to snap the brain back to its former state, those tips would be greatly appreciated. Just, please, no suggestions that I give up the Dragon Stout. Ain't gonna happen.

October 26, 2010

Justice for Paw Paw

I've previously examined the economics of Nigerian filmaking, a business that rewards both the prolific and the extremely cost-conscious. The industry's margins are typically razor thin because producers begin with the assumption that 70 percent of each movie's revenue will end up in the hands of pirates. The trick to longevity, then, is to create lots of films that enjoy massive initial demand—this isn't an environment in which movies are permitted to build audiences over time. And so Nigerian fillmakers are always keen to develop stars, whose movies always open solidly due to their fans' support.

Among those essential stars, few are more well-known than the comedic team of Paw Paw and Aki, two Little People actors who have become Nollywood's public face throughout much of Africa. Several years ago, in fact, the duo accidentally caused a riot in Sierra Leone after they failed to show for a promised engagement; the promoter tried to sub in local talent, to ill effect. And when the Nigerian Export Promotion recently decided to put together a series of trade missions aimed at bolstering the country's film industry, it naturally tapped Aki and Paw Paw to spread the word to Southern Africa.

Given how inseparable these two artists have been during their careers, it's baffling to learn that Nigeria's government recently decided to give Paw Paw the shaft. In doling out its version of the Kennedy Center Honors, the Lagos administration selected Aki while ignoring his equally famous partner. This is tantamount to giving a lifetime achievement Oscar to one Coen brother, but not the other. (I tried using an analogy that invoked the Paul brothers, but that seemed disrespectful to Aki and Paw Paw.)

Paw Paw can take some comfort, however, in the fact that the National Honour Awards appear to have rather bizarre criteria. Among those honored with Aki was Patricia Etteh, a disgraced politician best known for treating the Nigerian treasury like a personal piggy bank. A photograph of her holding her prize will someday be Nigeria's equivalent of this.

More Aki and Paw Paw here and here.

October 25, 2010

Turn Off the Dark

The mere act of flicking on a light switch is something that can't be taken for granted on the Navajo reservation, where tens of thousands of homes still lack electricity. Nowhere else in America do so many live in darkness, a fact driven home by this eye-popping stat:

More than 18,000 households on the reservation are waiting in the dark. According to the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, the largest utility provider on the reservation, that number accounts for 75 percent of all U.S. households without electricity.

So who's to blame for this failure to provide basic infrastructure? Though New Mexico's senior senator says that the federal government has yet to deliver on a promised $60 million for Navajo electrification, I have to think that the tribal government hasn't exactly acted with alacrity. The Navajo Nation Council appears to be thoroughly corrupt, as evidenced by the fact that 75 percent of its sitting members have been charged with abusing discretionary funds.

Such official misbehavior is sadly nothing new in Navajo country: Between 1989 and 1999, for example, three Navajo Nation presidents were bounced from office due to ethics violations. Yet the culture of graft persists, in part because of Navajo resistance to the meddling of federal authorities—a posture that is partly understandable due to obvious historical tensions. Many Navajo leaders who've been called out for corruption have argued that their actions were defensible according to tribal customs, which permit the acceptance of ceremonial gifts and the appropriation of communal money when emergencies arise. David Eugene Wilkins, a leading expert on Indian politics, points out that Navajo tradition actually has some tolerance for arrangements that the American legal system considers corrupt:

Should Navajo politicians be held to the same ethical standards as state or federal officials? Is the corruption and scandal that brought down Arizona Governors Fife Symington and Evan Meacham comparable to that which toppled Peter MacDonald?

These are important questions, particularly if it is true, as tribal leaders ad their constituents often insist, that Indian nations adhere to different cultural values than their non-Indian neighbors. But it is true for another reason. Since the Navajo Nation receives much of its funding from the federal government, many Washington officials insist that Navajo politicians must adhere to American ethical standards whether or not they clash with traditional Diné cultural standards.

It's always tough to modernize political systems when a society places a high value on tradition. That said, I'd be willing to bet that many of those 18,000 Navajos who exist without electricity wouldn't mind a little more financial rigor among their elected officials. Slush funds tend to pay for expensive steaks and golf outings, rather than for turning on the lights.

October 22, 2010

The Uzbek in the Mirror

Sorry about dropping the blogging ball this week. The quick trip to Florida made things rough, and I just remembered that the Grand Empress and I have a pressing appointment in Sunnyside today. When this post goes live, then, I'll likely be on the 7 train, looking out at Five Pointz.

I'll leave you, then, not with the usual Bad Movie Friday treatment, but rather with the animated Uzbek short above. It is the product of an state-sponsored industry in crisis, which is now looking to Bollywood to add some much-needed financial spark.

The few Uzbek filmmakers who remain manage to produce their art with what can charitably be descried as a modicum of resources:

Most of the Uzbek hits have been made for $30,000 to $50,000, and earned three to five times as much. The profits seem astounding for a country with an average monthly income of less than $50, where copyright piracy is ubiquitous, and most of the box-office revenues come from just a handful of cinemas in Tashkent.

It takes about two or three months to make a movie. Locations are few, and characters are easily recognizable. "The good guy must always be good, and the bad guy real bad," said Ruslan Yarullin, a cinematographer and film editor. "Folks like love stories with twisty plots, discotheques, rapes and murders."

Often a pop star or two, regardless of acting skills, play the leads – as they have money to invest, buzz to build and fans who will pay to see them on screen.

As you might imagine, I'm already thinking of ways to do post about the Uzbek pop-star scene.

October 21, 2010

Filet-O-Skink

I'm scrambling to catch up after the whirlwind Florida jaunt, so today's polymathism shall consist of a mere reference back to an oldie-but-goodie: My 2003 Slate piece about the veracity of Eric Rudolph's nutritional claims. The serial bomber stated that he managed to live on the lam for five-plus years by dining on North Carolina's cornucopia of lizards. But the calorie math just doesn't add up:

The region's most abundant species are classified as skinks and include the five-lined skink. These slender critters rarely grow longer than a man's hand and can weigh as little as a tenth of an ounce. Lizard meat provides about 50 calories per ounce, putting it on par with chicken. Assuming that Rudolph needed to consume a bare minimum of 1,500 calories per day—a very generous assumption, since winter survival is particularly grueling—he'd need to dine on nearly two pounds' worth of lizards each day. That's somewhere between 100 and 300 skinks, which means he'd have to spend virtually every waking moment turning over rocks and peering into rotted logs.

Back soon with posts on coin counterfeiting, Tongan politics, and the world's most dangerous airports.

(Image via Ryan Photographic)