Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 55

November 29, 2010

Signifying Nothing

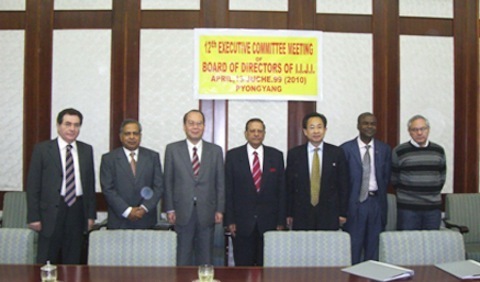

The human rays of sunshine above are academics devoted to the study of juche, the nonsensical North Korean ideology that stresses self-reliance above all else. You would think that men and women in possession of advanced degrees would recognize the flaws in an economic theory that denies the basic sociability of our species—or, at the very least, would have the critical thinking skills required to realize that North Korea staggers by thanks to foreign aid and smuggling, two major juche no-nos. But that doesn't appear to be the case for the select group of Ivory Tower dwellers who belong to the International Institute of the Juche Idea, which is sort of the Modern Language Association for Maoist fantasy.

The human rays of sunshine above are academics devoted to the study of juche, the nonsensical North Korean ideology that stresses self-reliance above all else. You would think that men and women in possession of advanced degrees would recognize the flaws in an economic theory that denies the basic sociability of our species—or, at the very least, would have the critical thinking skills required to realize that North Korea staggers by thanks to foreign aid and smuggling, two major juche no-nos. But that doesn't appear to be the case for the select group of Ivory Tower dwellers who belong to the International Institute of the Juche Idea, which is sort of the Modern Language Association for Maoist fantasy.

Background on the Institute's history can be found in this debriefing of a North Korean defector. Kim Il-sung evidently thought that he could strengthen North Korea's international standing by legitimizing juche as a scholarly topic. Not a wholly illogical plan, perhaps, as universities have always been a source of revolutionary agitation. But as you might expect, few professors were willing to devote their careers to studying an idea that is only slightly more coherent than Jonah Hex.

There have been a few takers, though, most notably in Nigeria, where the national juche committee recently got 530 college students to turn out for a lecture series. (I'm guessing there were free snacks.) And the IIJI's journal, Study of the Juche Idea, continues to publish semi-regularly; the latest issue actually features an article by an American, Anthony DiFilippo, a sociologist at Lincoln University.

I am most aggrieved to learn that the Institute has now established a beachhead in our beloved Mongolia, too—and at the venerable Chinggis Khan University, no less. How sad to think that a single Mongolian mind will be wasted pondering a philosophy that is essentially meaningless—a truism that even nifty clip art can't counteract.

November 24, 2010

The Only Way to Fly

I've long refused to travel during the holidays, a stance that makes even more sense in this era of rampant junk touching. I might change my mind, however, if modern air travel bore any faint resemblance to what's on offer in the Khrushchev-era Aeroflot commercial above. Dancing flight attendants in futuristic pink mini-skirts and white go-go boots? Free hand cream and wine? Yes and yes.

Okay, granted, the reality probably didn't live up to the Madison AvenueTretyakovsky Proyezd ideal. The flight attendants were probably surly, the pilots drunk. Still sounds better than having to fly Delta out of LaGuardia on the day before Thanksgiving.

Have a tremendous holiday, and see you back here in a few days.

November 23, 2010

Music is Our Underwater Torch

While I enjoy a good sci-fi concept album as much as the next khan, few bands are adept at creating mythologies that measure up to their music. Ziggy Stardust's backstory has always struck me as prosaic, for example, while the "Red Star of the Solar Federation" from Rush's 2112 is only a tad less schlocky than The Wild, Wild Planet.

The same cannot be said, however, for Detroit techno legends Drexciya, who built an entire career around a single unifying fantasy: the notion that there exists an underwater kingdom populated by the descendants of West Africans who were tossed overboard during the Middle Passage, yet somehow survived and learned to breath like fish. Primarily a one-man show steered by the late James Stinson, who refused to show his face publicly, Drexciya created lyric-less songs that fleshed out the imaginary history of this Atlantis-like world, occasionally expanding the narrative to show how the Drexciyan race evolved over the centuries (for example, by establishing diplomatic relations with a distant star called Clone). It's daft stuff, but it works because of the sonic textures of Stinson's work—so much so, in fact, that his music inspired painter Ellen Gallagher to do an entire series devoted to the mythology of Drexicya.

In researching Stinson's universe, I came across this intriguing tidbit from his obituary:

Although a jazz and hip-hop listener, Stinson also deliberately isolated himself from other electronic music, especially when recording, for the simple reason that he didn't want to be unduly influenced by other peoples' ideas.

I've often wondered about the wisdom of doing this—of isolating one's self from new ideas and modes of expression while in the thick of the creative process, so that you don't end up wearing your influences on your sleeve. A big part of being an artist is opening yourself up to as many ideas as possible, but there's also something to be said for trusting the visions that are rattling around your head, however odd they may seem. It probably helps to know thyself a bit before deciding whether or not to work in isolation, though; giving the brain too much alone time probably isn't the best idea for certain neural types.

Many more Drexciya tunes here; I'm partial to "Sea Snake."

November 22, 2010

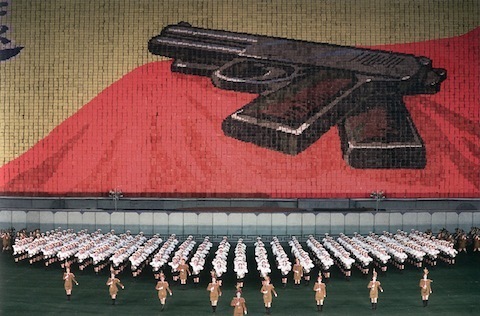

Tone Deaf

I spent much of the weekend zipping through The Reluctant Communist, former Army sergeant Charles Robert Jenkins' memoir of the 39 years he spent living in North Korea after walking across the demilitarized zone in 1965. It's a harrowing read, primarily because it reveals the North Korean establishment to be even more deluded than I'd previously realized. There is actually a nice parallel in the story between Jenkins' mindset before defecting and that of Kim Jong-il's regime. As Jenkins explains it, he was afraid of being deployed to Vietnam, and reckoned that he would surely be court-martialed if he went AWOL in South Korea. So he figured that he'd hand himself over to the North Koreans, who would then hand him over to the Soviets, who in turn would send Jenkins back to America as part of a Cold War prisoner swap. An absolutely bonkers plan, especially since there was no love lost between Pyongyang and Moscow. But it made sense in Jenkins' beer-addled mind, just as North Korea's seemingly daft scheming must feel logical to Kim and his frightened underlings.

There is one passage from the book that really gets to the heart of this logical dysfunction. It is Jenkins' account of North Korea's 1978 abduction of his Japanese wife, Hitomi Soga, from Sado Island. After being assaulted and stuffed in a sack, Soga was loaded onto a ship and put out to sea. That's when things got really strange:

They sailed the whole rest of the day and landed in Chongjin, North Korea, on the evening of the thirteenth. The next morning, they gave her breakfast and took her to the beach to look for clams. That is typical of how strange the North Korean cadres are, how out of touch they are with the emotions normal people have. Here they have just kidnapped you and your mother and separated you, they have ripped you from your home street in your own country without any explanation or any idea of what is going to become of you, and they are so out of touch with what they have just put you through and how you might hate them and fear them at that moment that they see nothing weird in saying, "Now that we have a few moments, maybe it would be fun for you to go to the beach to look for some clams?" They are that crazy.

This anecdote makes me wonder if a nation's entire elite can suffer from emotional tone deafness, simply because they were raised and educated in isolation from the world beyond their borders. Or perhaps it wasn't the isolation that deprived these cadres of their ability to pick up on social cues, but rather the fact that North Korean education is exclusively about indoctrination rather than socialization.

The bottom line is that human beings are far more malleable than we typically realize. The little things we take for granted—the capacity to recognize another person's pain, the logical prowess to link cause to effect—are not instinctual, but the product of early reinforcement. If a warped system gets its hooks into a child, it's equivalent to a virus embedding itself in a piece of software: The complete product may still look the same to the untrained eye, but it malfunctions in a precise and dreadful way.

(Photo via Philippe Chancel; more of his North Korean work here)

November 19, 2010

The Grandeur of Glory

(Cross-posted to/from PLoS Blogs)

(Cross-posted to/from PLoS Blogs)

All the recent chatter over the dangers of professional football compelled me to look up one of my favorite snippets of Greek mythology: the tale of Achilles' choice, from Book Nine of the Iliad. For those who have only foggy memories of high-school English, the story goes like this: the gods of Olympus gave Achilles the option of leaving Troy alive, in which case he would live to a ripe old age and die in anonymity. If he stayed in Troy, by contrast, he would be killed in battle, but his name would be renowned for all eternity. The fact that you're reading these words makes clear which fate Achilles selected; the parallel with debilitated former football players is tough to miss.

Leo Tolstoy explored similar philosophical terrain in The Two Brothers, a brief parable about siblings who choose very different paths through life. One is a stand-in for Achilles, a risk taker who prefers the peaks-and-valleys model of existence; the other is content to live in peace. The former brother gets the last word in the story, which suggests that Tolstoy's sympathies, like those of Homer, lay with the bold.

And that makes sense for men of letters, who typically need strong characters in order to create drama. (Okay, maybe not Arthur Miller, but you get the point.) But should populations at large similarly favor risk takers? While bold individuals certainly play a key role in advancing any species' fortunes, no population can afford to have too many members bent on glory at all costs. There has to be a balance between those with a predisposition to sally forth, and those who hang back in the rear and provide stability. What, then, is the optimal ratio between the two types?

There are some clues to be found in one of my favorite papers of recent vintage: "Effects of group size and personality on social foraging: the distribution of sheep across patches" from Behavioral Ecology. The paper describes an experiment in which researchers split their ovine subjects into two groups: one consisting of sheep notable for their boldness, the other of meeker compatriots. (The personality determinations were made based on how the sheep responded to various inanimate objects.) They then observed the animals' grazing habits over time, in order to discern how temperament might affects the sheep's' willingness to wander toward new patches of grass.

It came as no surprise that the bold sheep were more willing to break away from their groups in order to exploit fresh turf. But as the researchers noted, this doesn't mean that risk-taking individuals are necessarily more valuable to a population's survival than their meeker counterparts; it is the interplay between these two personality types that creates a population with the best long-term odds of success:

Our results demonstrate that individual variability can also promote behavioral plasticity at the level of groups within populations. It is possible that much of the variation in the spatial organization of groups may depend on fairly small phenotypic differences between a few individuals. Different personality types may also act as complementary forces at the scale of the flock or herd, with bold individuals contributing to the spread of the group and their ability to explore new resource sites and shy animals contributing to the maintenance of group cohesion.

The question then becomes, What is the ideal ratio between shy and bold individuals? Perhaps someday we'll be able to get a better sense of the answer by evaluating the distribution of so-called risk-taking genes—though, to be honest, I remain deeply skeptical of such methods, which strike me as too dismissive of nurture's role. Or maybe there is wisdom to be gleaned from the realm of military science, which has long been fascinated with the concept of the tooth-to-tail ratio—that is, the correct proportion of combat to support troops.

Above all, I'm curious about the role that narratives play in shaping the bold-to-shy balance. The Iliad's commendation of Achilles' choice or Sports Illustrated's frequent paeans to gridiron heroes reinforce the notion that it's always more noble to opt for glory over comfort. Does this suggest that humans are too predisposed toward meekness, so that we require cultural encouragement to develop a sufficient number of risk takers to sustain the species? If so, one might argue that storytelling has been more integral to our collective success than opposable thumbs.

November 18, 2010

I Want You to Want Me

There's a scene in My Best Fiend in which Werner Herzog reveals what made him believe that Klaus Kinski possessed rare talent. It was a brief moment in a film whose title now escapes me, about a German soldier who is executed for deserting the army to be with his girlfriend. (A Time to Love and a Time to Die, perhaps?) Kinski plays a lieutenant who is taking a nap with his head atop a wooden table, and is woken up by a subordinate. He stirs, snorts, and checks his watch, a series of actions that takes no longer than two seconds. But Herzog claims that the way Kinski awakens in the scene is dramatic genius, and something that still haunts his imagination to this day. My Best Fiend shows the clip again and again, until you can't help but see the great German director's point—there is something so unusual about Kinski's motion and body language that it's difficult to shake the cinematic moment.

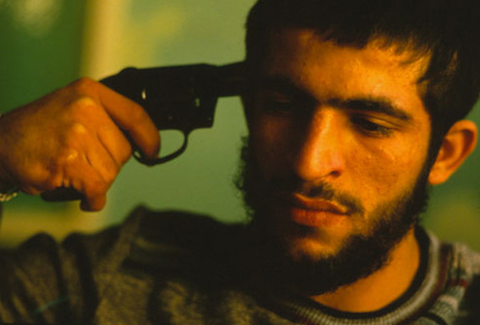

Herzog's championing of that scene came to mind recently when I stumbled upon this gallery of images by the great Turkish photojournalist Coskun Aral. Many years ago, I purchased an edition of The World's Most Dangerous Places that featured a brief article by Aral about his time in war-torn Lebanon. It was only a small sliver of a book that stretched over 1,000 pages, and the few accompanying photos were barely wallet-sized, black-and-white, and printed on newspaper-quality paper. Yet there was one image that immediately burned itself into my brain: the one above, of a Lebanese militiaman passing his leisure hours by playing Russian roulette. (According to Aral, the soldier died a week later when he gambled on the wrong chamber.)

I can't quite explain why this photo has stuck with me for over a decade now. There are certainly tons of Russian roulette images in popular culture, so it's not the sheer craziness of the situation that got to me. No, it was something much more subtle—the curl of grim resignation on the man's lips, the way in which the shadows already seemed to be claiming him for the grave. As a result, I've always made sure my tattered, coffee-stained copy of The World's Most Dangerous Places is within easy reach, so I can return to the photo whenever the memory of its initial impact flutters across my mind.

Aral took plenty more ultra-disturbing photos while on assignment in Lebanon, of course—there's one of Druze militiamen in Halloween masks that I've been dying to find online. But the Russian roulette image is his accidental masterpiece, a fleeting glimpse of raw desperation that deserves a place in the photjournalism canon.

Read more about Aral here, or watch an interview with the man here. And apologies if the Russian roulette photo gets its hooks into you—it's definitely not something you want hanging around your hippocampus when you want to be in a happy place.

November 17, 2010

Soul Points

Even by the most conservative estimates, Tonga is the most intensely Mormon nation on Earth. The official estimate is that roughly 15 percent of Tonga's population belongs to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but Mormons adherent place the figure much higher—typically around 32 percent, and sometimes even higher. This is par for the course in Polynesia, of course—of the ten nations with the highest concentrations of Mormons, six are in the South Pacific.

Even by the most conservative estimates, Tonga is the most intensely Mormon nation on Earth. The official estimate is that roughly 15 percent of Tonga's population belongs to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but Mormons adherent place the figure much higher—typically around 32 percent, and sometimes even higher. This is par for the course in Polynesia, of course—of the ten nations with the highest concentrations of Mormons, six are in the South Pacific.

Part of the LDS Church's success in Tonga is obviously due to tenacity of its missionaries, who first visited the kingdom in 1891. But there is another factor to consider, one that brings into question that nature of the conversion statistics: the fact that many Tongans adopt Mormonism for reasons that probably have less to do with spirituality than with bettering their family's fortunes:

Assembly line Mormon churches (with their inevitable basketball courts) are popping up in villages all over Tonga, as the children of Israel convert in droves to be eligible for the free buildings, schools, sporting facilities, and children's lunches. Many Tongans become "school Mormons," joining as their children approach high school age and dropping out as they complete college in Hawaii. Unlike Cook Islanders and American Samoans, Tongans don't have the free right of entry to a larger country, so church help in gaining a toehold in Honolulu or Salt Lake City is highly valued.

This doesn't necessarily mean that the Mormons' conversion strategy isn't clever. Even if a sizable percentage of Tongan adherents only gravitate toward the Church for the benefits, there is a good chance that many of their children, having passed through Mormon schools, will become more genuinely devout than their parents. This is similar to what happened in Nagaland, where American Baptist missionaries opened primary schools beginning in the late 19th century, and now the North-East Indian province is among the most earnestly Christian corners of the world—though, granted, the Nagas do embrace a form of Christianity that is more than a little tinged with tribal traditions.

But bribery and religion do make for strange bedfellows, don't they? It's clear that the LDS Church takes great pride in its conversion numbers from Tonga, using them as proof that its message resonates the world over—even with those who might not have been particularly welcome in the Church prior to 1978. But winning souls through material inducements strikes me as undermining one of a religion's key attributes: Its claim to offer an undeniable truth.

Is there something untoward about using bribery to attract converts, many of whose hearts are not truly changed by the proselytizers' message?

November 16, 2010

Spinning in Molasses

Too sick to offer anything halfway intelligible this morning—to cop a line from Killing Zoe, I feel as if the rest of the world is in a bubble of glass and that I'm rubbing up against it like a bad windshield wiper. As I recuperate, please enjoy the classic Jamaican rocksteady cut above, later made famous by Sugar Minott.

November 15, 2010

An All-Too-True Fish Story

You probably already knew that times were rough in Camden, New Jersey, but this photo essay really drives home the sad reality. In a part of the nation chock full of towns that have seen much better days, the former home of RCA Victor has become the poster child for all that can go wrong when an industrial base evaporates.

You probably already knew that times were rough in Camden, New Jersey, but this photo essay really drives home the sad reality. In a part of the nation chock full of towns that have seen much better days, the former home of RCA Victor has become the poster child for all that can go wrong when an industrial base evaporates.

Yet the ordinary ebb and flow of economic activity isn't wholly to blame for Camden's demise. Local politicians deserve a share of the blame, as this story makes clear:

The state invested $175 million in Camden, but most of the money went to a few big projects — like expanding a hospital and an aquarium, and building a law school — that were backed by leaders of the Democratic political machine that runs South Jersey. Much less went into neighborhood improvements like removing abandoned houses that shelter drug users and rats.

The aquarium project is a particularly sore point in Camden, as it was botched in truly ludicrous fashion. The original managers, under pressure from politicians to show Garden State pride in exchange for public funding, elected to have the aquarium highlight species that are native to New Jersey—a rather ugly lot, to be sure. (Over 90 percent of the tank space was reserved for native fish.) That decision spelled doom for hopes that the New Jersey State Aquarium might revive the troubled city:

For years the accepted wisdom about the mad public love for fish under glass meant that anybody could build an aquarium, and people would turn out in the millions. Then the New Jersey State Aquarium tampered with the formula by specializing in local fish.

There are a lot of brown fish in New Jersey waters. Brown flounder. Brown cod. Even much of the water is dun. The aquarium almost single-handedly brought down the national statistics for aquarium attendance and worse, it failed to prove the engine of redevelopment envisioned for this impoverished city across the Delaware River from Philadelphia.

"I mean, fish in New Jersey are not very interesting, they are kind of drab looking," Wanda M. Bullion, a librarian in the Camden schools, said. "The Nintendo generation wants color, excitement — you have to get their attention."

The aquarium did shift gears, but it never fulfilled its early promise. No longer a state property, it is now on its second private-sector owner, the same Georgia-based company that operates Dollywood. That means the state never came close to enjoying a decent return on its $52 million initial investment, not to mention the tens of millions more it dumped into renovations upon realizing that visitors didn't want to see flukes and flounders. And, of course, the aquarium never did become the anchor for a planned $500 million waterfront improvement project that the optimists in Trenton once envisioned.

There's no telling whether that $52 million-plus outlay might have helped reverse Camden's fortunes if it had been spent more wisely. But I'm sure the city's citizens wish they could find out.

November 12, 2010

Battling Gaston vs. Pretty Pierre

Americans are not the only ones who question soccer's emergence as the world's favorite athletic pastime. The sport has also occasionally come under fire from anti-colonialists, who would prefer that their nations opt for the games that were popular before the Europeans came a-knocking with their guns and smallpox. The Tunisian historian Borhane Errais is one such opponent, having characterized the flowering of soccer as a "cultural genocide." If he had his druthers—not to mention any small shred of political power—Errais would like for his fellow Tunisians to compete like their forefathers did:

In Ethnography of physical exercise in pre-colonial Tunisia, Errais mentions El Koura (a game like football in which two teams try to kick a ball into a goal), El Egfa (a game like hockey using wooden sticks, however the aim is not a goal but one's coat), and La Rekla (a game in which competitors kick each other, resembling the French game Savate) in regard to the people's exercise culture in pre-colonial Tunisia during the Ottoman rule.

Try as I might, I couldn't find any images or video of these traditional Tunisian sports, which perhaps hints at the fact that the country's public doesn't want to run around depriving each other of coats simply because an academic considers it patriotic. The best I could come up with was the vintage clip above, showing a savate match from France. Granted, there may be some prejudice at work in the film—the British do love nothing more than to highlight the wussiness of their Gallic neighbors to the south. But if "Pretty Pierre" was, indeed, a respected savate master in his time, I can understand why such a sport hasn't flourished in modern Tunisia.