R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 57

September 27, 2018

Rock Lyrics as Poetry

A colleague asked another for his favorite poem (we are an eclectic collection of English teachers, mind you). My colleague’s fave is "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and immediately upon his admission of the T.S. (that's Tough Shit) Eliot tome, I blurted out, as a fellow English teacher will do: "I have measured out my life in coffee spoons." Though hardly lighthearted, "Prufrock" is one of Eliot's most accessible poems (aside from Cats), a far cry from the preposterously sullen The Waste Land, his most critically acclaimed work. I would agree that "Prufrock" is an astute choice.

A colleague asked another for his favorite poem (we are an eclectic collection of English teachers, mind you). My colleague’s fave is "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and immediately upon his admission of the T.S. (that's Tough Shit) Eliot tome, I blurted out, as a fellow English teacher will do: "I have measured out my life in coffee spoons." Though hardly lighthearted, "Prufrock" is one of Eliot's most accessible poems (aside from Cats), a far cry from the preposterously sullen The Waste Land, his most critically acclaimed work. I would agree that "Prufrock" is an astute choice.The other teacher's response to the question was "Sounds of Silence." I forget the word my colleague used to describe the choice; pedantic, maybe, or sophomoric. His response to me was that no rock lyric could rate beside Eliot or Dylan Thomas, et al. Despite his opinionated brilliance, I couldn't disagree with him more. I took the defense of the other teacher to heart, quoting Springsteen, "The screen door slams,/ Mary's dress waves./ Like a vision she dances across the floor as the radio plays/ Roy Orbison singing, 'For the Lonely.'" Eliot, the disenfranchised American from Ohio, may indeed expertly capture the Brit soul, but "Thunder Road" is pure Americana, and like "Prufrock," plays with words and phrasing in an equally stylistic manner. The subtle rhyme, the enjambment within the lines making "as the radio plays" an American expression of incidental background music in general, but then, in the next line peppering the small town feel with Roy Orbison's iconic single, is genius.

My colleague's view is that it's always the music, and not the lyrics that provide the greater emotional impact, and yet the phatic is common to both song lyrics and poetry; music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry – forever – while poetry is its own pseudo music, damning it to a netherworld without melody. That in mind, maybe the choice of "Sounds of Silence" is indeed pedantic. The lyrics themselves sophomoric; one might call it kitsch. It’s not Simon's strongest lyric by any means, but that doesn’t discount Simon. From his play with John Donne in "I am a Rock," dismissing Donne’s ideology that no man is an island, to the sublime "America," which, like "Thunder Road" captures American Youth in its most restless, the twenty-five-year-old Simon was equal at least to the worst of Dylan Thomas, himself a drunken rock star, and rivals at times Thomas at his most okay, that “second chair” that Thomas, based on his alcohol distraction, sat in on many occasions.

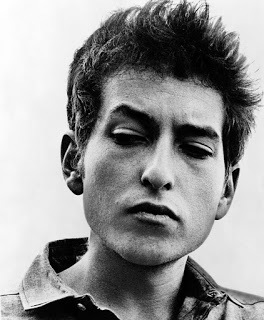

My colleague's view is that it's always the music, and not the lyrics that provide the greater emotional impact, and yet the phatic is common to both song lyrics and poetry; music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry – forever – while poetry is its own pseudo music, damning it to a netherworld without melody. That in mind, maybe the choice of "Sounds of Silence" is indeed pedantic. The lyrics themselves sophomoric; one might call it kitsch. It’s not Simon's strongest lyric by any means, but that doesn’t discount Simon. From his play with John Donne in "I am a Rock," dismissing Donne’s ideology that no man is an island, to the sublime "America," which, like "Thunder Road" captures American Youth in its most restless, the twenty-five-year-old Simon was equal at least to the worst of Dylan Thomas, himself a drunken rock star, and rivals at times Thomas at his most okay, that “second chair” that Thomas, based on his alcohol distraction, sat in on many occasions. The songwriter who captures best the idea of the poet is Bob Dylan (whose name, of course, comes from Dylan Thomas). Dylan is such an idiosyncratic genius that it's perilous to imitate him; his faults, at worst annoying, at best invigorating, ruin lesser talents. But contrary to the mythology (and to the Nobel Prize), the man did not revolutionize modern poetry, American folk, popular music, or the whole of modern thought; and the Village Voice, prattling on about "new plateaus for poetic, content-conscious songwriters" and "the bastard child of Chaplin, Celine and Hart Crane," is nothing, if not ludicrous. However inoffensive (at worst) or haunting (at best) "The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face" sounds on vinyl, it's plain silly without the music. Conversely, "My Back Pages" is a bad poem, though it's a great song with an unforgettable refrain. Music softens our demands, the importance of what is being said somehow overbalances the flaws, and Dylan's delivery adds an edge not present in the words. Add to that the premise that if the words don't work, one can always mumble, and you've realized the perfect formula. (That said, when Dylan won the Nobel Prize every poet and novelist in the world, myself included, threw up a little in his mouth. I mean really? Solzhenitsyn, Steinbeck, Kipling, Hemingway, Camus, Faulkner, Eliot, Churchill?)

In the same vein, The Mamas and Papas are full of diversions: contrapuntal arrangements, orchestral improvisations, odd rhyme schemes and John Phillips' trick of drawing out words with repetitions and pauses. In songs like "California Dreamin'," "12:30" and so many others, Phillips is obviously a good lyricist, though his lyrics are rarely easy to understand. I wonder how many are aware that "Strange Young Girls" is about LSD. No secret about it; it's right there out in the open in the first stanza: "Walking the Strip, sweet, soft, and placid/ Off'ring their youth on the altar of acid." But no one notices because there's so much within the song’s stellar arrangement. On a crude level, this vagary permits the kind of one-to-one symbolism of pot songs like "Along Comes Mary."

In the same vein, The Mamas and Papas are full of diversions: contrapuntal arrangements, orchestral improvisations, odd rhyme schemes and John Phillips' trick of drawing out words with repetitions and pauses. In songs like "California Dreamin'," "12:30" and so many others, Phillips is obviously a good lyricist, though his lyrics are rarely easy to understand. I wonder how many are aware that "Strange Young Girls" is about LSD. No secret about it; it's right there out in the open in the first stanza: "Walking the Strip, sweet, soft, and placid/ Off'ring their youth on the altar of acid." But no one notices because there's so much within the song’s stellar arrangement. On a crude level, this vagary permits the kind of one-to-one symbolism of pot songs like "Along Comes Mary." All this in mind, one is indeed hard-pressed to take a stance for rock music as poetry. Morrison’s "The End" is pedantic, to use my colleague's words, and The Police's "Don't Stand So Close to Me," sophomoric. But I can indeed go back to Simon: "What a dream I had… Pressed in organdy/ Clothed in crinoline of smoky burgundy/ Softer than the rain/ I wandered empty streets down past the shop displays/ I heard cathedral bells tripping down the alleyways/ As I walked on…" It’s Simon but it could be Shelley; alter the demeanor or the known cadence, it could be Emily Dickenson.

I don't even have to say a thing about Sincerely, L. Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat": "It's four in the morning, the end of December/ I'm writing you now just to see if you're better/ New York is cold, but I like where I'm living/ There's music on Clinton Street all through the evening. - I hear that you're building your little house deep in the desert/ You're living for nothing now, I hope you're keeping some kind of record. - Yes, and Jane came by with a lock of your hair/ She said that you gave it to her/ That night that you planned to go clear./ Did you ever go clear?

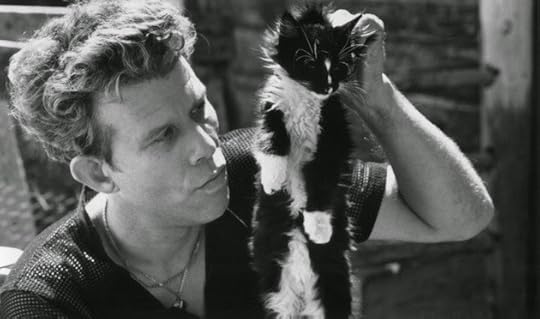

I don't even have to say a thing about Sincerely, L. Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat": "It's four in the morning, the end of December/ I'm writing you now just to see if you're better/ New York is cold, but I like where I'm living/ There's music on Clinton Street all through the evening. - I hear that you're building your little house deep in the desert/ You're living for nothing now, I hope you're keeping some kind of record. - Yes, and Jane came by with a lock of your hair/ She said that you gave it to her/ That night that you planned to go clear./ Did you ever go clear?Tom Waits wrote "Tom Traubert's Blues" after visiting Skid Row in Los Angeles, drinking a pint of rye and throwing up: "Wasted and wounded, it ain't what the moon did, I've got what I paid for now/ See you tomorrow, hey Frank, can I borrow a couple of bucks from you/ To go waltzing Mathilda, waltzing Mathilda,/ You'll go waltzing Mathilda with me." It’s Bukowski, that (but does it fly without the Aussie nursery rhyme?).

For simplicity through repetition on the basic human desire, maybe McCartney did it best: "Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ No one will be watching us,/ Why don't we do it in the road?" It's Twain simplicity and honesty, and daring for the 60s, with the next progression of theme and style going to Anthony Kiedis of Red Hot Chili Peppers: "Let me shine your diamond/ The girl got a scratch/ Slap that cat/ Have mercy - I want to party on your pussy, baby/ I want to party on, party on your pussy/ I want to party on your pussy, baby/ I want to party on your pussy, yeah, yeah, yeah."

From Joni Mitchell's Blue to Dark Side of the Moon, the poetry is there, often hidden within the music or the arrangements; what an unfair advantage. Poetry without it is a dying art. Ho-hum. I guess we will be seeing a lot more Dylans joining the 113 recipients of the Nobel (hopefully there are budding Plaths and Cummings out there to prove me wrong). In the meantime: "My head is my only house unless it rains." Yep, sheer poetry.

My favorite rock lyrics? Fleetwood Mac's "Landslide." I have no delusions about Nicks' lyrics vs. any "great" poetry, but the question was my favorite lyrics; not the greatest. My favorite poem, btw? "Shake and shake the ketchup bottle,/ None'll come and then a lot'll."

Published on September 27, 2018 05:05

September 25, 2018

Jay and the Americans - Tom Waits and the House of Pies

The House of PiesMy grandmother was all about The House of Pies. It was what you did. You did your chores, your due diligence, then you treated yourself to the banana cream or the rhubarb and a cup of coffee. She liked the one on Sunset. We'd spend a lot of time there, sitting in a pink and orange booth. It was when my mother was in Synanon. I didn't know what that was; just that she was getting her rest.

The House of PiesMy grandmother was all about The House of Pies. It was what you did. You did your chores, your due diligence, then you treated yourself to the banana cream or the rhubarb and a cup of coffee. She liked the one on Sunset. We'd spend a lot of time there, sitting in a pink and orange booth. It was when my mother was in Synanon. I didn't know what that was; just that she was getting her rest.The House of Pies closed in 1974. My grandmother's philosophy was that nothing good survived. It affected her adversely. "Nothing's good like it was."

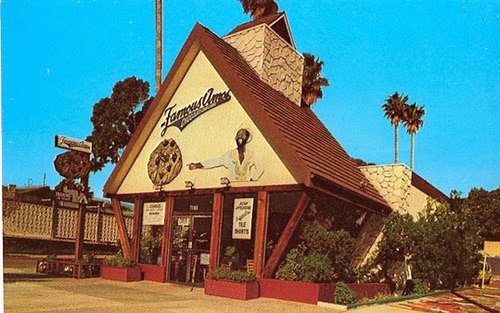

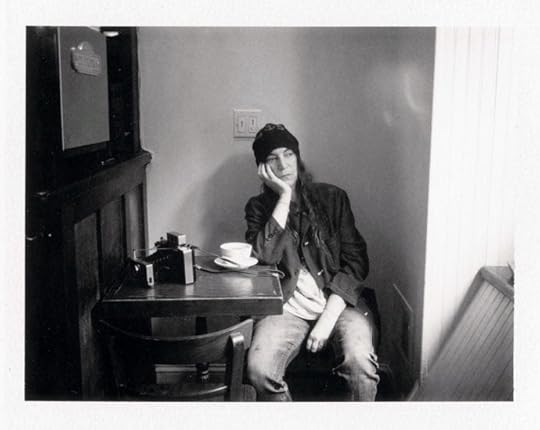

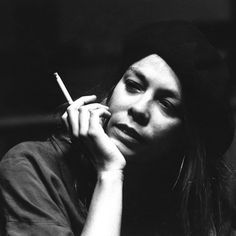

Famous AmosIn '75, in the fanciful building that was The House of Pies, Wally Amos opened Famous Amos Cookies. It was there that I went to some big deal soiree in the parking lot. Andy Warhol was there. He looked hot in his wig. Patti Smith was there in a Guinea T. Everyone was talking about her. I didn't know who she was. When she began to release albums in the mid-70s, Patti seemed to have eluded the shackles imposed on women in rock 'n' roll. She was neither angelic muse nor bad-girl sexpot; she was instead a tomboy willing to be photographed in a pale pink slip, flashing a patch of unshaven armpit hair that shocked the record-store boys more than just about anything any girl had ever done. So afraid of her was I at Famous Amos, that I avoided her all day. (Several years later I turned out to see this intimidating person at an in-store appearance at Tower on Sunset, only to have my copy of Easter signed by a soft-spoken urchin with a luminous smile.)

Famous AmosIn '75, in the fanciful building that was The House of Pies, Wally Amos opened Famous Amos Cookies. It was there that I went to some big deal soiree in the parking lot. Andy Warhol was there. He looked hot in his wig. Patti Smith was there in a Guinea T. Everyone was talking about her. I didn't know who she was. When she began to release albums in the mid-70s, Patti seemed to have eluded the shackles imposed on women in rock 'n' roll. She was neither angelic muse nor bad-girl sexpot; she was instead a tomboy willing to be photographed in a pale pink slip, flashing a patch of unshaven armpit hair that shocked the record-store boys more than just about anything any girl had ever done. So afraid of her was I at Famous Amos, that I avoided her all day. (Several years later I turned out to see this intimidating person at an in-store appearance at Tower on Sunset, only to have my copy of Easter signed by a soft-spoken urchin with a luminous smile.)In the hallway at school the next day Max Ten said, "Jay, picking you up Saturday." It wasn't a question, it was matter of fact. "Tom Waits. You've gotta hear this guy. Got a voice like an emery board. Fantastic."

Max Ten had a 1969 gold Austin America. Max could have driven a four door Datsun and it would still be cool, but the Austin America was over the top. It had a Deadhead sticker on the back window. Paige was in the back seat and at first I was a little taken aback. I sat in the passenger seat and we picked up Belinda Pocket and Paigeboy. The girls sat in back. Belinda wore a mini dress that was pretty indescribable. Imagine a gypsy-style white top, pretty see through, then below the elbows and below the waist it was a black and white paisley print. It was pretty stunning, and I’ve got to admit, Paigeboy looked like a million bucks in a pale green knitted dress, real short, her hair parted in the middle, curled real nice.

Max Ten had a 1969 gold Austin America. Max could have driven a four door Datsun and it would still be cool, but the Austin America was over the top. It had a Deadhead sticker on the back window. Paige was in the back seat and at first I was a little taken aback. I sat in the passenger seat and we picked up Belinda Pocket and Paigeboy. The girls sat in back. Belinda wore a mini dress that was pretty indescribable. Imagine a gypsy-style white top, pretty see through, then below the elbows and below the waist it was a black and white paisley print. It was pretty stunning, and I’ve got to admit, Paigeboy looked like a million bucks in a pale green knitted dress, real short, her hair parted in the middle, curled real nice. We headed out over Sepulveda Pass into Santa Monica to a venue that wasn’t much of anything but a converted storage space in the back of McCabe’s Guitar Shop. It looked like the kind of place that would catch fire. There were a hundred guitars hanging on the walls, Gibsons and Fenders and Rickenbackers. There was a makeshift stage and a wall of amplifiers. Tom Waits was crazy and drunk and sang songs like "Ol' '55" and "Rosie." Leave it to Max Ten; the music was absolutely diabolical. It was always 2am in Waits’ music and a bottle of Jack was paying you back, whispering loneliness. I wrote that in my red journal. Long ago I’d bought another journal and then another, but I kept that first one, the one from Gaia for the stuff I never wanted to forget. I don’t know if I said it or if it was Max Ten, but I at least was the one who wrote it down. It was 1974. Patti Smith was there. She scared the shit out of me. I wrote that down too.

I never mentioned my father dancing. We were in Joe and Aggie's Café in Holbrook, Arizona. We had chili con carne with onions and my father had a couple Coors. We were playing a pinball machine called Gottlieb's Bowling Queen and my father went to the bar for another beer. A pretty lady in a cowboy hat started talking to him and the next thing I knew he was out on the floor dancing a cowboy line dance. He didn't know what he was doing. I was so distracted that I let the fifth ball slip down between the flippers without enough for a replay, but I matched numbers and still got a free game. I didn't play it. I went and sat in the booth and watched my father dance. He was laughing the whole time and carrying on and when it was time for everybody in the line to tap the tip of their boots, he thought that was grand. It was the only part he really got down, otherwise he kept doing the wrong thing. It was real nice to see him have fun.

Tom Waits didn't sing cowboy music, but there was an accordion and a cello in a couple of the numbers and I couldn't help but think about the dance my father did so poorly. Music can transport you places, so I was like back there in Arizona with my father. Tom Waits can take you places.

Jay and the Americans is available all over the world!

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UK - Amazon France - Amazon Russia

Published on September 25, 2018 04:19

September 24, 2018

Jay and the Americans - Rickie Lee

Upstairs at the RoxyJay and the Americans. is a fictional memoir. Most of it's true, like 90%, though I've stretched things a bit here and there. It's what storytellers do. Jay and the Americans is available on Amazon and CreateSpace, just click on the links in the sidebar.

Upstairs at the RoxyJay and the Americans. is a fictional memoir. Most of it's true, like 90%, though I've stretched things a bit here and there. It's what storytellers do. Jay and the Americans is available on Amazon and CreateSpace, just click on the links in the sidebar.The eighties were incidental, like music for films. I graduated from college and took a job; a job-job with the Hollywood Reporter. I got paid and everything; I hob-nobbed with the elite; I went to people's parties. As a part of the press I was part of the fringe, the outskirts of the privileged. It wasn't like work at all. Thank God.

I met Andy Warhol at Famous Amos on Sunset, maybe I mentioned this. He had on the biggest wig I'd ever seen. He said, "Nice to meet you." I met Bud Cort at a mixer. He was very quiet. I said, "I enjoy your work." He said, "Thank you." That's what I mean by the fringe. I met people. They said, "Nice to meet you" and "Thank you."

I saw Rickie Lee Jones at the Roxy and wrote a review for the L.A. Weekly. Tom Waits was in the audience, shitfaced. So was Chuck E. Weiss. Rickie too, was drunk as a skunk, but the funky songs were funky and the beautiful ones were beautiful. The show was over, the crowd dispersed; the curtain was drawn when she pushed her way through. She said, "Where’s my hat? Where's my fucking beret?" I was sitting at a table taking notes. She looked at me. "Jou take my hat? Hey, hey, where's my fucking hat?"

Tom Waits came out from behind the curtain. In his gruff voice he said, "Hey, you seen the lady's hat?"

Tom Waits came out from behind the curtain. In his gruff voice he said, "Hey, you seen the lady's hat?"I looked around. A beret was on the table next to mine. I handed it to her. She said, "Well, thanks, then. I though' you stole my hat."

I said, "'Company' was beautiful." It was. So melancholy and so sad.

I used that story in my review, the gist of it. It colored it; it said in words what I heard, the beauty of her melodies; the discord of the lyrics.

I saw Tom Waits at the Troubadour. Rickie Lee was in the audience. She said, "I know you." Lots of people knew me; not about me; not my name, just my face. I was familiar, like a little brother: I was there but it didn't matter. It was as if, at any moment, someone would send me off to bed, and yet, I was writing about them, I wasn't benign in their lives; they just didn't know it. It was kind of funny.

I said, "I love your work."

She said, "Thank you," and asked if I had change for a dollar.

Published on September 24, 2018 11:29

September 22, 2018

Chuck E.'s in Love (AM10)

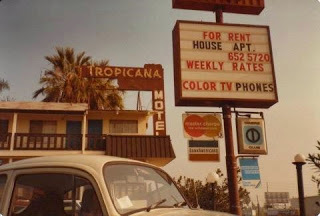

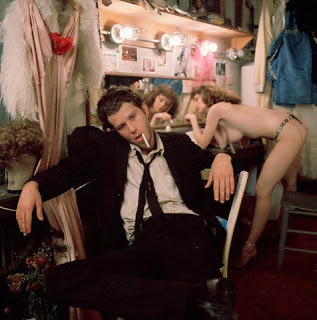

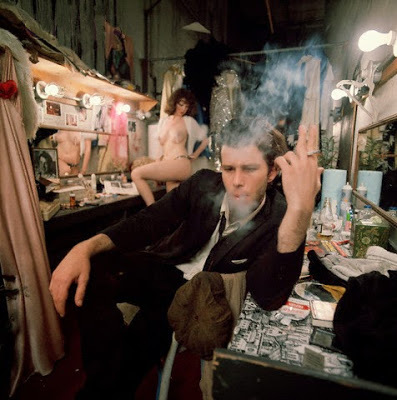

The Hollywood threesome that captured our attention in the late 70s was Tom Waits, Rickie Lee Jones and Chuck E. Weiss, who essentially became the most famous of the three, an accidental celebrity. In 1977, $65 bought a week at the seedy hipster paradise called the Tropicana on Santa Monica Blvd., just up the street from Barney's Beanery. Chuck E. slept on a couch, I suppose, or in the other bed. It's an assumption on my part, but as a compatriot hit up for quarters for the cigarette machine at the Troubadour on a regular basis, I can assume that he didn't have 65 bucks a week. "Chuck E.'s in Love" wouldn't be released for several more years, but the content of what may be the all time hippest single in pop history was already established. Waits, on the breadth of his first four LPs, but particularly on the success of Small Change, was already an established singer/songwriter, playing gigs at the Troub and at McCabe's in Santa Monica.

The Hollywood threesome that captured our attention in the late 70s was Tom Waits, Rickie Lee Jones and Chuck E. Weiss, who essentially became the most famous of the three, an accidental celebrity. In 1977, $65 bought a week at the seedy hipster paradise called the Tropicana on Santa Monica Blvd., just up the street from Barney's Beanery. Chuck E. slept on a couch, I suppose, or in the other bed. It's an assumption on my part, but as a compatriot hit up for quarters for the cigarette machine at the Troubadour on a regular basis, I can assume that he didn't have 65 bucks a week. "Chuck E.'s in Love" wouldn't be released for several more years, but the content of what may be the all time hippest single in pop history was already established. Waits, on the breadth of his first four LPs, but particularly on the success of Small Change, was already an established singer/songwriter, playing gigs at the Troub and at McCabe's in Santa Monica. Let's Rewind. Waits' previous album, Nighthawks at the Diner (1975), was recorded at the Record Plant studio with an audience to capture the ambiance of a live venue. It was a pretty telling album. Of it he said, "I was sick through that whole period. I'd been traveling quite a bit, living in hotels, eating bad food, drinking a lot — too much. There's a lifestyle that's there before you arrive and you're introduced to it. It's unavoidable."

Let's Rewind. Waits' previous album, Nighthawks at the Diner (1975), was recorded at the Record Plant studio with an audience to capture the ambiance of a live venue. It was a pretty telling album. Of it he said, "I was sick through that whole period. I'd been traveling quite a bit, living in hotels, eating bad food, drinking a lot — too much. There's a lifestyle that's there before you arrive and you're introduced to it. It's unavoidable." Small Change (1976) found Waits in a cynical and pessimistic mood, with songs like "The Piano Has Been Drinking (Not Me) (An Evening with Pete King)" and "Bad Liver and a Broken Heart (In Lowell)." These were the songs that established Waits as a rock icon (including, of course, "Tom Traubert's Blues"). With Small Change Waits became a poster child, a poet laureate for off-kilter American cool and took his act overseas. Rickie Lee wasn't yet a part of his life.

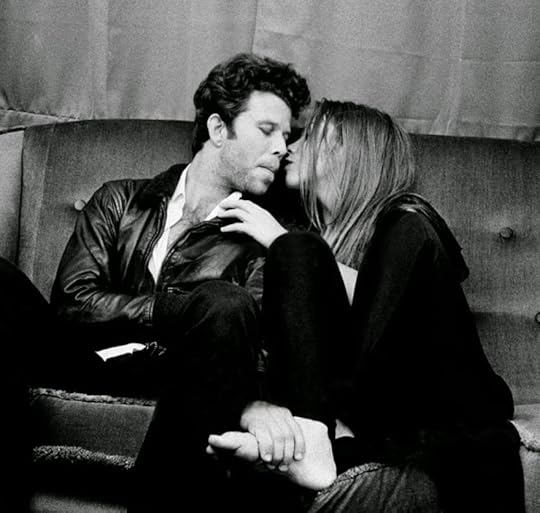

That would change one fateful night at Doug Weston's Troubadour. Rickie Lee sang a short set of songs (including "The Moon is Made of Gold," only recently recorded for the album Balm in Gilead) following the performance of an obscure singer-songwriter named Ivan Ulz, who was instrumental in introducing several members of The Byrds, but little else. That night led to Tom's room at the Trop and a lifelong friendship of collaboration (if only temporary intimacy). Rickie never left and somewhere along the line, Chuck E. showed up.

Then suddenly Chuck was gone, vanished. I went to the Troubadour and no one hit me up for a drink or for change. Every once in a while somebody'd say, "What happen to that guy?"

Then suddenly Chuck was gone, vanished. I went to the Troubadour and no one hit me up for a drink or for change. Every once in a while somebody'd say, "What happen to that guy?""Chuck E? I dunno."

Story goes that Chuck E. finally called Waits from Denver where he'd fallen in love with his cousin. When Waits got off the phone he said to Rickie, "Chuck E.'s in Love." Instrumental in the success of the Viper Room, just down from the Whiskey, Chuck E. Weiss's career as a singer/songwriter has never equaled his fame as that character in Rickie's story, the ending of which is fictional; there was never any relationship between the two. Chuck E. was "never in love with the little girl singin' this song."

Jay and the Americans is available all over the world!

Get Your Copy Today.

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UK - Amazon France - Amazon Russia

Published on September 22, 2018 04:53

September 21, 2018

Doug Weston's Troubadour

Elton John, beginning to make a name in England, played the Troubadour for six nights in August 1970. He came to consider that gig as the best move in his career. "My whole life came alive that night, musically, emotionally... everything. It was like everything I had been waiting for suddenly happened. I was the fan who had become accepted as a musician."

Elton John, beginning to make a name in England, played the Troubadour for six nights in August 1970. He came to consider that gig as the best move in his career. "My whole life came alive that night, musically, emotionally... everything. It was like everything I had been waiting for suddenly happened. I was the fan who had become accepted as a musician." In the late 1960s and early 70s, Doug Weston's Troubadour was the most consistently important showcase of contemporary folk and folk-rock talent in the country. "Look at the list of performers," he said. "We like to think of that list as a sort of hall of fame." Weston first set up shop in the 1950s in a 65-seat coffeehouse on La Cienega. By 1957 he had made enough to open the 300-seat Troubadour at its current West Hollywood location, 9081 Santa Monica Blvd. Initially the venue did poetry readings and plays, but in the mid 60s, a very different faction of artists began to frequent the club. Whereas the Whiskey and the clubs on the Strip catered to a teen crowd and a more rambunctious brand of rock, the Troub featured a focused and musical set of singer/songwriters that by 1968 included Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Hoyt Axton, Laura Nero, Judy Collins, Mason Williams, Neil Diamond and the Smothers Brothers, with artists as diverse as Lenny Bruce and Nina Simone. "The people who play our club are sensitive artists who have something to say about our times. They are modern-day troubadours," Weston said.

By 1966, artists like The Association (who were the first "rock" oriented band to play), Judy Collins, Rod McKuen, Odetta, Muddy Waters and John Denver exemplify the diversity of acts on stage at the Troub. The success of the club lay in part with the fearlessness of its owner. Weston booked controversial, even blacklisted acts, such as Lenny Bruce, who was arrested in 1957 for using the obscenity "schmuck" on stage. Even though it was a 1st Amendment infringement, Lenny Bruce was handcuffed and taken away during his act.

Elton John, August 25, 1970

Elton John, August 25, 1970Weston was particularly fond of the Laurel Canyon set, showcasing acts like The Byrds (who met at the club's Monday open mic night in 1964), Buffalo Springfield (who played their first gig at the Troub in 1966, never having played live before), and James Taylor, as well as Joni Mitchell and Graham Nash. They would all come down from the canyon and hang out. Monday's became known as the Monday Night Hootenanny and Weston would allow whoever to audition on stage. Whoever was often Joni or Neil or David Crosby. A&R people would show up and literally sign artists from right off the stage. By the 70s, that list included Elton, Rickie Lee Jones and Tom Waits (signed on the spot). On November 29, 1970 James Taylor played Carole King's "You've Got a Friend" for the first time (he'd heard Carole sing it - she was his opening act and pianist); just another night at the Troubadour. The headliners and newcomers over the past fifty years read like a rock encyclopedia.

Lennon, Anne Murray, Nilsson, Alice Cooper, Mickey DolenzAnd it wasn't just about the performers on stage. The Eagles' Don Henley and Glenn Frey met at The Troubadour's bar in 1970 (later they'd write a song about the Troub called "Sad Cafe"). Janis Joplin was at the Troubadour the night before she died. In 1974 John Lennon and Harry Nilsson were ejected from the Troub for heckling the Smother's Brothers. As Lennon's story goes, "I got drunk and shouted. It was my first night on Brandy Alexanders; that's brandy and milk, folks. I was with Harry Nilsson, who didn't get as much coverage as me, the bum. He encouraged me. I usually have someone there who says, 'Okay, Lennon. Shut up." He went on to say, "When it's Errol Flynn the showbiz writers say, 'Those were the days when men were men.' When I do it, I'm a bum.'"

Lennon, Anne Murray, Nilsson, Alice Cooper, Mickey DolenzAnd it wasn't just about the performers on stage. The Eagles' Don Henley and Glenn Frey met at The Troubadour's bar in 1970 (later they'd write a song about the Troub called "Sad Cafe"). Janis Joplin was at the Troubadour the night before she died. In 1974 John Lennon and Harry Nilsson were ejected from the Troub for heckling the Smother's Brothers. As Lennon's story goes, "I got drunk and shouted. It was my first night on Brandy Alexanders; that's brandy and milk, folks. I was with Harry Nilsson, who didn't get as much coverage as me, the bum. He encouraged me. I usually have someone there who says, 'Okay, Lennon. Shut up." He went on to say, "When it's Errol Flynn the showbiz writers say, 'Those were the days when men were men.' When I do it, I'm a bum.'" Nilsson, LennonDespite Doug Weston's death in 1999, the club under new ownership hasn't changed. [About the only thing I can think of is you can't smoke. I remember when Chuck E. Weiss used to hit me up for change for the cigarette machine, but that's about it.] Since then the Troub has been the catalyst for Fiona Apple (live debut, September 10, 1999), The Killers and Franz Ferdinand (1st L.A. appearance), a return to the small club atmosphere for The Cure, Depeche Mode and Tom Petty, and a vital component in music promotion. When in L.A., see whoever is there; they are the next Elton, James or Rickie Lee.

Nilsson, LennonDespite Doug Weston's death in 1999, the club under new ownership hasn't changed. [About the only thing I can think of is you can't smoke. I remember when Chuck E. Weiss used to hit me up for change for the cigarette machine, but that's about it.] Since then the Troub has been the catalyst for Fiona Apple (live debut, September 10, 1999), The Killers and Franz Ferdinand (1st L.A. appearance), a return to the small club atmosphere for The Cure, Depeche Mode and Tom Petty, and a vital component in music promotion. When in L.A., see whoever is there; they are the next Elton, James or Rickie Lee. Tom Waits, August 16, 1975

Tom Waits, August 16, 1975

Published on September 21, 2018 05:51

September 19, 2018

Return to Forever

I mean, how lucky were we to have grown up in the early 70s? True that Kendrick Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize, and deservedly so, but by 1975, young people experienced a treasure trove, not unlike Ali Baba's; there plain weren't enough hours in a day. Simultaneously there was Pink Floyd, Steely Dan, Joni Mitchell, Springsteen, Bowie, Elton, Patti Smith, Eagles, Queen, Fleetwood Mac – each of these artists with among their best LPs. And just when you thought you could finally leave the house and give the solid state a rest, there was fusion on top of it. It had permeated the Dan, Joni Mitchell and JT by that point, but it had the teeth to make it on its own.

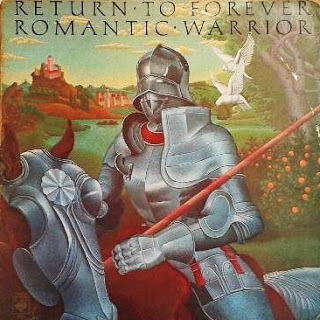

I mean, how lucky were we to have grown up in the early 70s? True that Kendrick Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize, and deservedly so, but by 1975, young people experienced a treasure trove, not unlike Ali Baba's; there plain weren't enough hours in a day. Simultaneously there was Pink Floyd, Steely Dan, Joni Mitchell, Springsteen, Bowie, Elton, Patti Smith, Eagles, Queen, Fleetwood Mac – each of these artists with among their best LPs. And just when you thought you could finally leave the house and give the solid state a rest, there was fusion on top of it. It had permeated the Dan, Joni Mitchell and JT by that point, but it had the teeth to make it on its own. Few LPs come close to Return to Forever's Romantic Warrior. If someone were to ask me about Jazz-Rock Fusion, I would simply hand them this compendium. It is flawless, exuberant, and timelessly delicious, a pharmacopeia of musical styles, enough to please the classical ear as well as the jazz aficionados. To get the most out of it, listen six times; one time through, focusing on each individual musician. The four of them are supremely talented, and each provides creative and virtuoso performances rarely rivaled. After those four listens, listen again to how they weave it all together. By the time you get to the sixth go-round, you're ready to interpret the music through your body. Dance, in other words. It is wondrously embodiable (oddly, a word). Purely magic.

The lineup of Chick Corea, Al Di Meola, Stanley Clarke, and Lenny White is impeccable with each adding their own sense of pure jazz, classical, flights of whimsy ("The Sorcerer and the Magician"), and elements of stylistic audacity coupled with a mastery of guitar and bass (especially in the "Duel of the Jester and the Tyrant"), along with the elegiac themes of "Majestic Dance." Alongside Mahavishnu Orchestra and Weather Report, here was a music that hit upon the elements of sophisticated progressive music that I'd learned of and grown up with in Yes and ELP, the medieval quirkiness of Gentle Giant and Tull, the smooth late at night feel of Hejira and Al Jarreau and the musicianship of Crimson. If you've never heard Romantic Warrior, don't wait any longer.

Published on September 19, 2018 04:02

September 17, 2018

Innervisions

The ideology behind AM is to create an objective forum. Based on time and space, this is a generally impossible task. As a critic, rubric or not, my omission of an album may make a very bold statement without formally criticizing the work. I personally disregard three musical artists, despite the fact that, based on the AM rubric, they may otherwise attain high marks. I simply don't like Van Morrison, Michael Jackson, and Creedence Clearwater. Van's music I go back to time and again and find it inaccessible (though I have an affinity for Them's "Here Comes the Night"). That's a subjective review based not on the rubric but on personal feelings. By not reviewing Morrison I'm off the hook, but my disregard through omission is glaringly obvious. Creedence I just don't care about. Michael Jackson, I find astronomically overrated. That indeed is true subjection. I like Michael, there are songs with which I have a great affinity, but Jackson was by no means, rubric or otherwise, The King of Pop, and I guess I resent the moniker.

The ideology behind AM is to create an objective forum. Based on time and space, this is a generally impossible task. As a critic, rubric or not, my omission of an album may make a very bold statement without formally criticizing the work. I personally disregard three musical artists, despite the fact that, based on the AM rubric, they may otherwise attain high marks. I simply don't like Van Morrison, Michael Jackson, and Creedence Clearwater. Van's music I go back to time and again and find it inaccessible (though I have an affinity for Them's "Here Comes the Night"). That's a subjective review based not on the rubric but on personal feelings. By not reviewing Morrison I'm off the hook, but my disregard through omission is glaringly obvious. Creedence I just don't care about. Michael Jackson, I find astronomically overrated. That indeed is true subjection. I like Michael, there are songs with which I have a great affinity, but Jackson was by no means, rubric or otherwise, The King of Pop, and I guess I resent the moniker.Unfortunately, omission often sends a false negative. AM has followed a historical trail over the past several months. We've made it into '74 and reviewed Court and Spark, Gram Parsons, Neil Young, Supertramp's Crime of the Century, Steely Dan, Queen, Elton John, Zappa, Dylan, Eno, Jackson Browne, Mott the Hoople; indeed a cavalcade of stellar artists and albums. But AM courses a path that is far from inclusive. I have to step back at times to recognize what I have missed, not through omission, but through forgetfulness or "into-ness." I've been obsessing of late on Roxy and Bowie and David Sylvian, the new Death Cab, and have simply overlooked one of the great albums of an era: Stevie Wonder's Innervisions (as I have overlooked many others. Among the AM10s: Marvin Gaye's What's Goin' On, Goodbye, Yellow Brick Road, Curtis Mayfield's Superfly Miles Davis's In a Silent Way). The point remains, the goal at AM be as objective as possible, but now my little secret is out: I will not be reviewing Michael Jackson or Creedence or Van, and you know why. On the other hand:

Innervisions (AM10) is flawless: the gurgling funk of "Too High," the lustrous quiet guitar of "Visions" (Dean Parks on nylon string and David T. Walker on a sweet electric), the punchy, raucous soul of "Living in the City" and its trademark riff in an off-time signature, the ascending Latin and jazzy tinged organ-drenched "Golden Lady" on side one alone. Side two: a demolishing wah-wah-filled propulsive beat in "Higher Ground," the jazzy and hum-able "Don't you Worry 'bout a Thing" and the lovely and teary ballad "All is Fair in Love." This is Stevie delivering proof of his multi-instrumentalist skills and his peculiar flair for making a beat irresistible and melodies memorable, and doing it all on his own. Innervisions was released in August 1973 and remained deservedly high on the charts throughout '74.

Published on September 17, 2018 03:58

September 16, 2018

Opinion

Pop radio in 2018 is enough to make you want to pull out your hair. An insipid girl army led by Taylor Swift, Drake-inspired mediocrity and Charlie Puth provide a colorless pastiche of ho-hum that's manifested by the likes of iTunes. But there are signs, maybe due to the fall of the format, that a renaissance is upon us. From Childish Gambino to Elle King, there is a new pop that's emerging and a sense that despite the corporate focus on the run-of-the-mill, pop (and rock as well) is not dead.

Pop radio in 2018 is enough to make you want to pull out your hair. An insipid girl army led by Taylor Swift, Drake-inspired mediocrity and Charlie Puth provide a colorless pastiche of ho-hum that's manifested by the likes of iTunes. But there are signs, maybe due to the fall of the format, that a renaissance is upon us. From Childish Gambino to Elle King, there is a new pop that's emerging and a sense that despite the corporate focus on the run-of-the-mill, pop (and rock as well) is not dead.AM provides a forum for the phenomenal output of rock and pop over the past 50 years with far less emphasis on the music that has befallen us since the 1990s. Indeed, if there was a decade that I would dismiss, it would be the 90s. Of course, there's Radiohead, Tool, and Weezer, but with Cobain's death and the passing of the rock torch to the disappointing Peal Jam (one phenomenal LP and a thousand to follow that sound exactly the same – note the difference in Bowie), pop music has hobbled along. We've discussed in the past the exceptions, with Kid A and Weezer's Blue LP as good as anything from the 80s – indeed, OK Computer ranks with Dark Side – but no one will argue for the 90s as the greatest rock era.

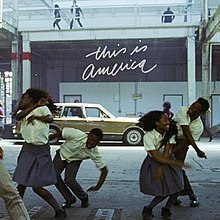

All this sounds as if there weren't Nicki Minaj equivalents in the 70s, while there certainly were, and yet the 70s cavalcade of posts here on AM in the past several months show a wealth of diversity unheard of since. So let's bring this back around to the positive. It's amazing to me that an LP like Stevie Wonder's Innervisions (AM10) could provide a base for both LP and pop formats. Here was music as art for the masses – conceptual, political, accessible and overflowing with stellar musicianship, unparalleled songwriting, wrapped in a pop sensibility. We're not back there yet, but with the death of iTunes as the barometer of modern music comes what – keep your fingers crossed – may be a new era of musical integrity. All that said, it's so refreshing to see the charts veer away from Justin Bieber and Maroon 5 to find singles like "This is America," Jack White's "Over and Over and Over" and Death Cab's "Gold Rush."

All this sounds as if there weren't Nicki Minaj equivalents in the 70s, while there certainly were, and yet the 70s cavalcade of posts here on AM in the past several months show a wealth of diversity unheard of since. So let's bring this back around to the positive. It's amazing to me that an LP like Stevie Wonder's Innervisions (AM10) could provide a base for both LP and pop formats. Here was music as art for the masses – conceptual, political, accessible and overflowing with stellar musicianship, unparalleled songwriting, wrapped in a pop sensibility. We're not back there yet, but with the death of iTunes as the barometer of modern music comes what – keep your fingers crossed – may be a new era of musical integrity. All that said, it's so refreshing to see the charts veer away from Justin Bieber and Maroon 5 to find singles like "This is America," Jack White's "Over and Over and Over" and Death Cab's "Gold Rush."My questions, though, remains, does this new renaissance have the legs to be remembered 40 years on the way that we relish in songs like "Livin' For the City," "What's Going On?" or my all-time favorite single, "Ventura Highway"? Indeed, look at the popularity of Weezer's cover of Toto’s "Africa;" never was there a more faithful tribute to the way it was.

The point, there's hope. Trump will be impeached; music, with the death knell of iTunes still ringing in our ears, will find its renaissance.

Published on September 16, 2018 06:12

September 15, 2018

Sparks are Gonna Fly

Everyone's got one. We all have our favorite great underrated band we love to ramble on about, fuming over the injustice of their omission, angered at their absence from the grand narrative of rock history, outraged at their exclusion from the hall of fame. I’m inclined to choose The Tubes or Nick Drake, yet Sparks, surely, are the ultimate. Oh, the Mael brothers had their moment. One huge hit, a couple of follow-ups, and - thanks to Russell’s pretty-boy looks, if not Ron's unsettling Victorian serial killer demeanor - the fickle fluttering hearts of the Jackie generation (including a young Steven Morrissey, who famously stalked the brothers to the extent of collecting uneaten toast from their hotel breakfast plates). Which is why, to the masses, Sparks - if the name triggers any recognition whatsoever - will always be the band who sang "This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us."

Everyone's got one. We all have our favorite great underrated band we love to ramble on about, fuming over the injustice of their omission, angered at their absence from the grand narrative of rock history, outraged at their exclusion from the hall of fame. I’m inclined to choose The Tubes or Nick Drake, yet Sparks, surely, are the ultimate. Oh, the Mael brothers had their moment. One huge hit, a couple of follow-ups, and - thanks to Russell’s pretty-boy looks, if not Ron's unsettling Victorian serial killer demeanor - the fickle fluttering hearts of the Jackie generation (including a young Steven Morrissey, who famously stalked the brothers to the extent of collecting uneaten toast from their hotel breakfast plates). Which is why, to the masses, Sparks - if the name triggers any recognition whatsoever - will always be the band who sang "This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us."  Those who are a little more in-the-know, however, will be aware that in the early 1970s, Sparks were neck and neck with Roxy as art-glam pioneers, and right up there with Queen for rock operatics. What few people other than hardcore adherents of Sparxism recognize, though, is that over the last four decades, Ron and Russell Mael have been superior even to Bowie in terms of long-term consistency. Their current record-breaking London residency, the 21-date Sparks Spectacular (in which they play every album from their career, one per night), is presumably intended to go some way towards redressing that injustice. It seems to be working. Suddenly - while they still remain underrated in relation to the true level of their genius - the Mael brothers are right back on the agenda.

Those who are a little more in-the-know, however, will be aware that in the early 1970s, Sparks were neck and neck with Roxy as art-glam pioneers, and right up there with Queen for rock operatics. What few people other than hardcore adherents of Sparxism recognize, though, is that over the last four decades, Ron and Russell Mael have been superior even to Bowie in terms of long-term consistency. Their current record-breaking London residency, the 21-date Sparks Spectacular (in which they play every album from their career, one per night), is presumably intended to go some way towards redressing that injustice. It seems to be working. Suddenly - while they still remain underrated in relation to the true level of their genius - the Mael brothers are right back on the agenda.

Published on September 15, 2018 05:50

September 14, 2018

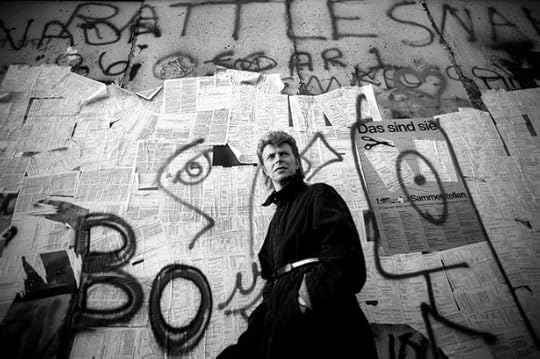

Bowie and the Wall - 1987

Long time readers will note that AM strives for connections; each post is in some way related to the last and the past. James Burke's 1978 British Television series Connections worked that premise into a theme. The ten part series was a linear look at how discoveries through time, scientific achievements and world events built one upon the other until, bam, it was 1978. The show, filmed in 1977 (there’s a connection to our recent posts) was a starting point for this writer's fascination with holistic thought and our little planet's journey through space and time.

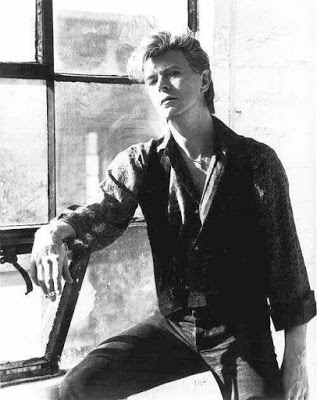

Long time readers will note that AM strives for connections; each post is in some way related to the last and the past. James Burke's 1978 British Television series Connections worked that premise into a theme. The ten part series was a linear look at how discoveries through time, scientific achievements and world events built one upon the other until, bam, it was 1978. The show, filmed in 1977 (there’s a connection to our recent posts) was a starting point for this writer's fascination with holistic thought and our little planet's journey through space and time.Often in the written history of rock, critics emphasize the ill-named "supergroup." One can find charts filled with arrows and squiggles that demonstrate how someone like Neil Young went from Buffalo Springfield to Crazy Horse to CSNY to solo artist to collaborating with Pearl Jam. But those kinds of connections (both in rock and here on AM) can reflect far headier importance. Rock music need not be as superficial in terms of its connections. Personally, I find the whole scenario fascinating: all those arrows and and algorithms that make up the supergroups and each evolution or revolution of an artist, and AM, of course, is designed to have a unique continuity, like putting together a party and wanting everything to look and sound just so. (For those of you who have noticed, thanks.) Over the past week, AM has evolved, at least momentarily, away from 1967 and explored the '77 of Talking Heads, Elvis Costello and those artists readily associated with David Bowie's most critically acclaimed period: Iggy Pop, Lou Reed and Brian Eno (don't worry, we'll back track at some point in our connections to Roxy Music). Now it's time to connect with 1987, an incredible 20 year span.

In 1977, Bowie not only released Low but the equally over-the-top part 2 of the Berlin Trilogy, “Heroes.” That said, “Heroes” is not my favorite Bowie album, nor is it my favorite Bowie era. Indeed, although I have issues with the Thin White Duke, I appreciate that era a bit more. More often than "Warzawa," I crave the Johnny Mathis stylings of "Wild is the Wind" and "Word on the Wing," get lost in the science fiction of "TVC 15" and mired in the soul of that incredible production of "Win" from Young Americans. My favorite Bowie era is, as it should be, from Ziggythrough Diamond Dogs (maybe including Pinups). I was a young teen, unsure of my sexuality and of my interests, but I wasn't unsure of music. Music was a constant and I had my cassette player and cassettes, those albums that I played simultaneously and incessantly. Aladdin Sane, The Who’s Quadrophenia, Zepplin's Houses of the Holy. I remember listening to humble pie quite a bit and then fully getting into my progressive years with Emerson Lake and Palmer, Jethro Tull or Gentle Giant, and don't forget Joni Mitchell's jazz tinkerings. I remember picking up Nico's Chelsea Girl and noting that one of the best songs on the album was by a kid from Californian by the name of Jackson Browne, "Fountain of Sorrow." There are connections everywhere; didn't the Beach Boys do backup vocals for Pink Floyd (well, in a way)?

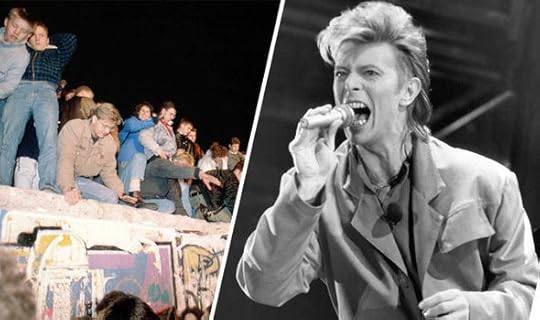

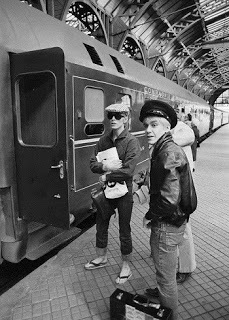

Anyhow, I started this segment with the intent of talking about Bowie and moving from the “Heroes” of 1977 to the performance of the iconic track in front of the Berlin wall in 1987, two years before the fall. Here's where rock plays a greater role, where there's an incredible amount more importance than just whether or not the band that Carl Palmer played in before Emerson, Lake and Palmer was Atomic Rooster.

Anyhow, I started this segment with the intent of talking about Bowie and moving from the “Heroes” of 1977 to the performance of the iconic track in front of the Berlin wall in 1987, two years before the fall. Here's where rock plays a greater role, where there's an incredible amount more importance than just whether or not the band that Carl Palmer played in before Emerson, Lake and Palmer was Atomic Rooster. And so, in 1987 Bowie set up shop in front of the wall in a divided city city of turmoil and severance. Berlin in 1987 was like Bowie's 1984; it had that sinister ideology and a wall down the middle; not a wall to keep people out, but to keep others in.

I, I can remember (I remember)

Standing, by the wall (by the wall)

And the guns, shot above our heads (over our heads)

And we kissed, as though nothing could fall (nothing could fall)

And the shame, was on the other side

Oh we can beat them, forever and ever

Then we could be heroes, just for one day

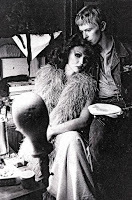

The "wall" in question was of course the Berlin Wall, which divided the city so ominously at the time. Bowie initially maintained that the song's protagonists were an anonymous couple who would meet by the Berlin Wall, but in 2003 he told Performing Songwriter the song was inspired by Tony Visconti, the record producer. Bowie recalls, "I'm allowed to talk about it now. I wasn't at the time. I always said it was a couple of lovers by the Berlin Wall that prompted the idea. Actually, it was Tony Visconti and his girlfriend. Tony was married at the time. And I could never say who it was [laughs]. But I can now say that the lovers were Tony and a German girl that he'd met whilst we were in Berlin. I did ask his permission if I could say that. I think possibly the marriage was in the last few months, and it was very touching because I could see that Tony was very much in love with this girl, and it was that relationship which sort of motivated the song.

The "wall" in question was of course the Berlin Wall, which divided the city so ominously at the time. Bowie initially maintained that the song's protagonists were an anonymous couple who would meet by the Berlin Wall, but in 2003 he told Performing Songwriter the song was inspired by Tony Visconti, the record producer. Bowie recalls, "I'm allowed to talk about it now. I wasn't at the time. I always said it was a couple of lovers by the Berlin Wall that prompted the idea. Actually, it was Tony Visconti and his girlfriend. Tony was married at the time. And I could never say who it was [laughs]. But I can now say that the lovers were Tony and a German girl that he'd met whilst we were in Berlin. I did ask his permission if I could say that. I think possibly the marriage was in the last few months, and it was very touching because I could see that Tony was very much in love with this girl, and it was that relationship which sort of motivated the song."I'll never forget that. It was one of the most emotional performances I've ever done. I was in tears. They'd backed up the stage to the wall itself so that the wall was acting as our backdrop. We kind of heard that a few of the East Berliners might actually get the chance to hear the thing, but we didn't realize in what numbers they would. And there were thousands on the other side that had come close to the wall. So it was like a double concert where the wall was the division. And we would hear them cheering and singing along from the other side. God, even now I get choked up. It was breaking my heart. I'd never done anything like that in my life, and I guess I never will again. When we did "Heroes" it really felt anthemic, almost like a prayer. However well we do it these days, it's almost like walking through it compared to that night, because it meant so much more.

And that is one of the greatest connections one could fathom.

Published on September 14, 2018 04:15