R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 86

February 25, 2018

Pynchon and Wilson

Rubber Soul was the catalyst for Pet Sounds. Pet Sounds for Sgt. Pepper. Indeed, McCartney has stated more than once that "God Only Knows" is the most beautiful song ever written. But it was more than a beautiful song that influenced Paul. "It was Pet Sounds that blew me out of the water. First of all, it was Brian's writing. I love the album so much. I've just bought my kids each a copy of it for their education in life. I figure no one is educated musically 'til they've heard that album. I was into the writing and the songs.

Rubber Soul was the catalyst for Pet Sounds. Pet Sounds for Sgt. Pepper. Indeed, McCartney has stated more than once that "God Only Knows" is the most beautiful song ever written. But it was more than a beautiful song that influenced Paul. "It was Pet Sounds that blew me out of the water. First of all, it was Brian's writing. I love the album so much. I've just bought my kids each a copy of it for their education in life. I figure no one is educated musically 'til they've heard that album. I was into the writing and the songs."The other thing that really made me sit up and take notice was the bass lines on Pet Sounds. If you were in the key of C, you would normally use...the root note would be, like, a C on the bass (demonstrates vocally). You'd always be on the C. I'd done a little bit of work, like on 'Michelle,' where you don't use the obvious bass line. And you just get a completely different effect if you play a G when the band is playing in C. There's a kind of tension created.

"I don't really understand how it happens musically because I'm not very technical musically. But something special happens. And I noticed that throughout that Brian would be using notes that weren't the obvious notes to use. As I say, 'the G if you're in C---that kind of thing. And also putting melodies in the bass line. That I think was probably the big influence that set me thinking when we recorded Pepper, it set me off on a period I had then for a couple of years of nearly always writing quite melodic bass lines."

While McCartney would go on with The Beatles to Magical Mystery Tour, The White Album, Let It Be and Abbey Road, Wilson would wander recklessly from manic genius to depression. While there are sublime moments that survived the Smile years ("Friends," "Surf's Up," Sunflower and snippets Holland, Wilson's fractured genius would never again emerge like it did on Pet Sounds.

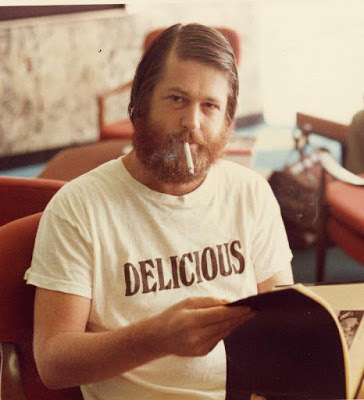

Although the competitive battle between Beach Boy and Beatle is commonly reported, Wilson's genius affected many other artists as well, from Pink Floyd to Wilco, and most oddly, writer Thomas Pynchon, a writer known for his nearly avant-garde experimentation in literature, most famously in the novel, Gravity's Rainbow.

I took him to my apartment in Laurel Canyon, got him royally loaded and made him lie down on the floor with a speaker at each ear while I played Pet Sounds, their most interesting and least popular record. It was not then fashionable to take The Beach Boys seriously. ‘Ohhhhh,” he sighed softly with stunned pleasure after the record was done. ‘Now I understand why you are writing a story about them.’

In 1966, writer Jules Siegel brought Pynchon to Brian Wilson's home on Laurel Avenue in Coldwater Canyon, just a canyon east of Laurel, where it is reported that the famous hipster novelist sat in stunned, unhappy silence while the nervous, stoned pop star — who had dragged him into his Arabian tent to get high — kept kicking over the oil lamp he was trying to light. "Brian was kind of afraid of Pynchon," Seigel wrote in Playboy, "because he'd heard he was an Eastern intellectual establishment genius. And Pynchon wasn't very articulate. He was gonna sit there and let you talk while he listened. So neither of them really said a word all night long. It was one of the strangest scenes I'd ever seen in my life.

One night we all went up to Brian Wilson’s Babylonian house in Bel-Air. Brian then had in his study an Arabian tent made of crimson and purple Persian brocade. It was like being inside the pillow of a shah. There was one light, fashioned from a parking meter. You had to put pennies in it to make it stay on. Brian brought in an oil lamp and tried to light it. The parking-meter light kept going out and Brian kept dropping the oil lamp and stumbling over it. Neither he nor Pynchon said anything to each other. Another night, we went to Studio A at Columbia Records, only to find our way barred by one of Brian’s assistants, Michael Vosse, who explained that we couldn’t come in anymore, because Chrissie [Jules’ wife who was with him and Pynchon] was a witch and fucking with Brian’s head so heavy by ESP that he couldn’t work.

In the mid-60s, both Pynchon and Wilson were forging new creative paths in their respective art forms. Both artists, fueled by visions partially — or significantly — enhanced by the ingesting of psychedelics, were attempting to capture these visions in their work. Pynchon, in Gravity's Rainbow, and Wilson, trying to further extend his idea of "a teenage symphony to God" with the highly anticipated follow-up to Pet Sounds, Smile.

In the mid-60s, both Pynchon and Wilson were forging new creative paths in their respective art forms. Both artists, fueled by visions partially — or significantly — enhanced by the ingesting of psychedelics, were attempting to capture these visions in their work. Pynchon, in Gravity's Rainbow, and Wilson, trying to further extend his idea of "a teenage symphony to God" with the highly anticipated follow-up to Pet Sounds, Smile.Pynchon was able to wrangle his deep and complex vision into an incredible novel, winning the National Book Award in 1974 and almost garnering a Pulitzer Prize (rather than select such a controversial novel, the jurors gave out no prize for literature in 1974). Wilson, however, facing pushback from his father, The Beach Boys and his record company, as well as a psyche increasingly destabilized by his drug intake and mental health, was unable to bring Smile to fruition.

And that's it. That’s all I have: an encounter. Two voices of a generation meeting at the peak of their creative powers, sitting in an Arabian tent smoking pot, not saying a damned word to each other. It's almost perfect.

Published on February 25, 2018 17:44

Surf's Up - Step by Step

Pet Sounds was Brian Wilson's ultimate achievement, but it shouldn't have been. The distinction should have gone to SMiLE (whatever "should haves" are worth). For this writer, SMiLE doesn't even exist, except as "the most famous unreleased album of all time." It's release in 2004 as Brian Wilson Presents SMiLE wasn't what we wanted. (Purists, like me, just want it to go away.) It's interesting, though, how much we still need to talk about it, or write about it and speculate; if wishes were fishes, we'd all have aquariums.

Pet Sounds was Brian Wilson's ultimate achievement, but it shouldn't have been. The distinction should have gone to SMiLE (whatever "should haves" are worth). For this writer, SMiLE doesn't even exist, except as "the most famous unreleased album of all time." It's release in 2004 as Brian Wilson Presents SMiLE wasn't what we wanted. (Purists, like me, just want it to go away.) It's interesting, though, how much we still need to talk about it, or write about it and speculate; if wishes were fishes, we'd all have aquariums. When you get as messed up as Brian during the SMiLE sessions, doctors and psychologists, or our own personal gurus, are bound to suggest that you "take it easy" and "step back from the edge," and that's what we got. Over a long stretch that included the LPs Smiley's Smile, Sunflower and Surf's Up, we got a watered-down version of what we wanted. This was Brian Wilson's sturm und drang, and if we're fair (mostly to ourselves), we'd be best served to go back and listen, to find the storm and stress, and to realize just how good what we got was. The point being, we didn't get SMiLE, we got Surf's Up, Sunflower and Smiley's Smile, with Wild Honey thrown in on the side, and each is a joy in themselves; but more than anything else, we got "Surf's Up."

On the Inside Pop television special in 1967, Leonard Bernstein described "Surf's Up": "There is a new song, too complex to get all of first time around. It could come only out of the ferment that characterizes today's pop music scene. Brian Wilson, leader of the famous Beach Boys, and one of today’s most important pop musicians, sings his own 'Surf’s Up.' Poetic, beautiful even in its obscurity, 'Surf’s Up' is one aspect of new things happening in pop music today. As such, it is a symbol of the change many of these young musicians see in our future…" Pretty high praise from an American master.

In Jules Siegel’s 1967 article, "Goodbye Surfing, Hello God!" Brian plays Siegel an acetate dub of the song on his bedroom hi-fi and tries to explain the words (Wilson and Van Dyke parks collaborated on the lyrics).

A diamond necklace played the pawnHand in hand some drummed along, ohTo a handsome man and batonA blind class aristocracy

"It's a man at a concert. All around him there's the audience, playing their roles, dressed up in fancy clothes, looking through opera glasses, but so far away from the drama, from life."

Back through the opera glass you seeThe pit and the pendulum drawn

"The music begins to take over."

Columnated ruins domino

"Empires, ideas, lives, institutions; everything has to fall, tumbling like dominoes."

Hung velvet overtaken meDim chandelier awaken meTo a song dissolved in the dawn

"He begins to awaken to the music; sees the pretentiousness of everything."

The music hall a costly bowThe music all is lost for nowTo a muted trumpeter swan

"Then even the music is gone, turned into a trumpeter swan, into what the music really is."

Columnated ruins dominoCanvass the town and brush the backdropAre you sleeping, Brother John?

"He's off in his vision, on a trip. Reality is gone; he's creating it like a dream."

Dove nested towers the hour wasStrike the street quicksilver moonCarriage across the fog

"Europe, a long time ago."

Two-Step to lamp lights cellar tuneThe laughs come hard in Auld Lang Syne

"The poor people in the cellar taverns, trying to make themselves happy by singing. Then there's the parties, the drinking, trying to forget the wars, the battles at sea."

The glass was raised, the fired roseThe fullness of the wine, the dim last toastingWhile at port adieu or die

"Ships in the harbor, battling it out. A kind of Roman empire thing."

A choke of griefHeart hardened IBeyond belief a broken man too tough to cry

"At his own sorrow and the emptiness of his life. Because he can't even cry for the suffering in the world, for his own suffering. And then, hope."

Surf’s UpAboard a tidal waveCome about hard and joinThe young and often spring you gave

"Go back to the kids, to the beach, to childhood."

I heard the wordWonderful thingA children’s song

"The joy of enlightenment, of seeing God. And what is it? A children’s song! And then there's the song itself; the song of children; the song of the universe rising and falling in wave after wave, the song of God, hiding the love from us, but always letting us find it again, like a mother singing to her children."

"The joy of enlightenment, of seeing God. And what is it? A children’s song! And then there's the song itself; the song of children; the song of the universe rising and falling in wave after wave, the song of God, hiding the love from us, but always letting us find it again, like a mother singing to her children."Brian fails to mention the coda, the intricate and delicate interpolation of "child" repeated and "[That's why] A child is father to the man."

The song itself is an amazing concoction of troubled and complex lyricism amidst what may be the most beautiful arrangement in pop music. But for many it went even further. Jimmy Webb ("MacArthur Park") said, "It almost seems to me that 'Surf's Up' is like a premonition of what was going to happen to our generation, and what was going to happen to music; that some great tragedy, that we could absolutely not imagine, was about to befall our world. There are really some very disturbing clairvoyant images in 'Surf's Up' that seem to say, 'Watch out, this is not gonna last.'"

Published on February 25, 2018 14:30

February 24, 2018

The Last Great Beach Boys Song

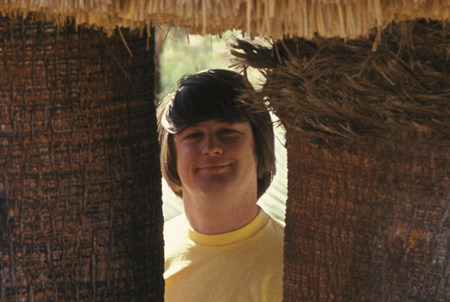

On a flight to Houston in 1964, Brian Wilson experienced a terrifying panic attack which led to his decision to stop touring with The Beach Boys and focus on his songwriting and studio work. Wilson dealt with the anxiety and the stress of live performance by taking to the studio to produce a canon of music on par with the greatest popular music of the 20th Century; as the story goes, Brian heard The Beatles' Rubber Soul and said, "We can't let them get ahead of us. I can take us further." The result was Pet Sounds, which Rolling Stone and AM rank the penultimate album of all time (after Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which was the Beatles response to the Beach Boys album).

On a flight to Houston in 1964, Brian Wilson experienced a terrifying panic attack which led to his decision to stop touring with The Beach Boys and focus on his songwriting and studio work. Wilson dealt with the anxiety and the stress of live performance by taking to the studio to produce a canon of music on par with the greatest popular music of the 20th Century; as the story goes, Brian heard The Beatles' Rubber Soul and said, "We can't let them get ahead of us. I can take us further." The result was Pet Sounds, which Rolling Stone and AM rank the penultimate album of all time (after Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which was the Beatles response to the Beach Boys album). Wilson said he began hearing voices after his first experience with LSD, probably in 1965. Eventually, he would be diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, before a final diagnosis of schizo-affective disorder. The symptoms and subsequent diagnoses of his illness are portrayed in the most poignant manner in the stellar biopic Love & Mercy. T.S. Eliot popularized the idea of the "Objective Correlative," a theory that music or poetry or painting, for instance, should be analyzed purely on its merits alone, with the artist's personal exploits left to the artist. Not buying it. No one will deny the virtuosity of the Beat Farmer's 9th Symphony, but how much more intriguing is Beethoven's 9th when one understands that Ludwig Van was deaf? A song like Lennon's "God" indeed has no meaning without a knowledge of Lennon's bio. With this in mind, the Brian Wilson of the late 60s, and his musical output as well, centered on his psychosis.

Some of the most powerful scenes in Love & Mercy are of Wilson being over-medicated and manipulated by quack therapist Eugene Landy, played in the film by Paul Giamatti. The historical record shows that Landy took advantage of his famous patient, using him to live out his own fantasies of artistic acclaim and celebrity, while Wilson acknowledges that Landy was not just a therapist, but a friend who helped him get out of bed at a time when everyone else had given up on him.

Some of the most powerful scenes in Love & Mercy are of Wilson being over-medicated and manipulated by quack therapist Eugene Landy, played in the film by Paul Giamatti. The historical record shows that Landy took advantage of his famous patient, using him to live out his own fantasies of artistic acclaim and celebrity, while Wilson acknowledges that Landy was not just a therapist, but a friend who helped him get out of bed at a time when everyone else had given up on him. But more than Landy or medications or external therapy, Brian's recovery seems a product of his work. "I dread the derogatory voices… They say things like, 'You are going to die soon,' and I have to deal with those negative thoughts… When I'm on stage, I try to combat the voices by singing really loud. When I'm not on stage, I play my instruments all day, making music for people. Also, I kiss my wife and kiss my kids. I try to use love as much as possible."

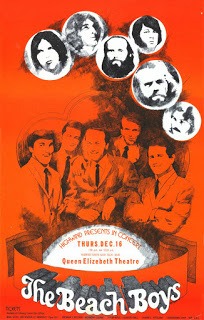

In 1967, of course, after Wilson challenged the very limits of the recording industry with Pet Sounds, the group began to lose its dynamic stranglehold on the very genre they defined. When SMiLE was abandoned, musical peers, critics and fans stopped listening overnight. While 1967's Smiley Smile featured "Good Vibrations" and "Heroes and Villains," these, like so many tracks in the early 70s Beach Boy canon, were rehashes of SMiLE. The Beach Boys would go on to create a bevy of accomplished LPs; LPs that were just not hip anymore, with Pet Sounds' genius, and not the lack of SMiLE responsible for the Boys' demise and loss of prestige. Indeed, Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone unfairly described The Beach Boys as "just one prominent example of a group that had gotten hung up trying to catch The Beatles."

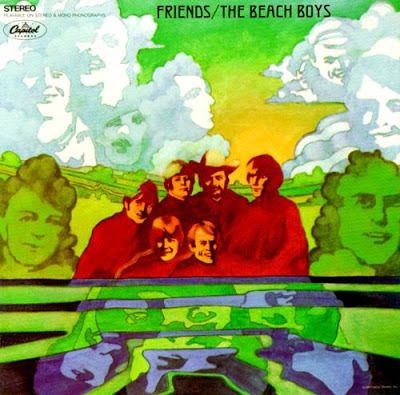

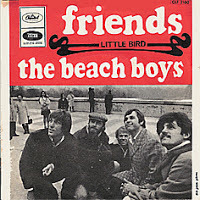

In 1967, of course, after Wilson challenged the very limits of the recording industry with Pet Sounds, the group began to lose its dynamic stranglehold on the very genre they defined. When SMiLE was abandoned, musical peers, critics and fans stopped listening overnight. While 1967's Smiley Smile featured "Good Vibrations" and "Heroes and Villains," these, like so many tracks in the early 70s Beach Boy canon, were rehashes of SMiLE. The Beach Boys would go on to create a bevy of accomplished LPs; LPs that were just not hip anymore, with Pet Sounds' genius, and not the lack of SMiLE responsible for the Boys' demise and loss of prestige. Indeed, Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone unfairly described The Beach Boys as "just one prominent example of a group that had gotten hung up trying to catch The Beatles." The Beach Boys — almost overnight — became dissident imagery in a time of eruptive change. In June 1968 — a period that clearly illustrates that America was in a state of dramatic disarray — Friends was released. The Beach Boys would go on to produce albums that find their way to my turntable 50 years later, Holland in particular, but should we handpick the canon, it ends gloriously with the greatest of rock waltzes, the title track, "Friends." For this writer, "Friends" is the last great Beach Boys track.

"Pet Sounds is by far my very best album, though my favorite is Friends," Wilson said. "I think that the Beach Boys sound was developing right along. I had developed a sixth sense for everybody’s voices." Sessions for the record started in February at Wilson's home studio, while the writing took place in the dog days of the Summer of Love. The album's title cut was released as a single in April 1968, making it to No. 47. Originally a standard 4/4 rock tune, Brian's genius transformed it into 3/4 time just to be different, and everything is there to extol the track as a Beach Boys masterpiece, particularly its incredible harmonies. Friendsholds a special place for many Beach Boys fans. After a period of discord, the group came together on the record in nearly the same way The Beatles did for Abbey Road, though music fans immersed in the latest records by Hendrix or Cream were no longer interested. There were no songs about revolution, drugs or politics on Friends. Times had changed, but the Boys hadn't, if anything taking a step back.

"Pet Sounds is by far my very best album, though my favorite is Friends," Wilson said. "I think that the Beach Boys sound was developing right along. I had developed a sixth sense for everybody’s voices." Sessions for the record started in February at Wilson's home studio, while the writing took place in the dog days of the Summer of Love. The album's title cut was released as a single in April 1968, making it to No. 47. Originally a standard 4/4 rock tune, Brian's genius transformed it into 3/4 time just to be different, and everything is there to extol the track as a Beach Boys masterpiece, particularly its incredible harmonies. Friendsholds a special place for many Beach Boys fans. After a period of discord, the group came together on the record in nearly the same way The Beatles did for Abbey Road, though music fans immersed in the latest records by Hendrix or Cream were no longer interested. There were no songs about revolution, drugs or politics on Friends. Times had changed, but the Boys hadn't, if anything taking a step back."Friends" is far more naive and pedestrian than anything from Pet Sounds, but there was a return here to something simpler. "Friends" wasn't about teenage angst or "columnated ruins," it was about the simplicity of friendship.

Published on February 24, 2018 04:16

February 23, 2018

The Poetry Vs. Lyrics Thing

We settle into a seat on a train, at times forgetting the destination, enjoying the ride of its own accord. The train is its own world, even as it moves with purpose; if the train broke down, we'd be annoyed - the purpose of the train slips our minds only fleetingly - yet it allows us in its mesmerizing clickity-clack to forget the reason for the journey and to simply enjoy the experience. Expression is like this, too. We talk for a reason, and yet we also just enjoy talking. Poetry then is reticent expressiveness; it combines the enjoyable and the purposeful aspects of the train ride; at times rambling on, clickity-clackiting; at times direct and purposeful. As AM continues its little sabbatical on poetry, we've contemplated a myriad of songs, seeking out the journey, whether or not there is a destination. For this little aside (expect more over the next few days), we've constricted the poetry, with some exception, to 1968. The poetry of a song like Leslie Gore's "It’s My Party," therefore, pure Emily Brönte btw, doesn't make the cut, nor does The Stones' "Ruby Tuesday" or Rod Stewart's "Maggie Mae."

1968 features prominently in the music-as-poetry construct, a time which, artistically, happily, resembles the Romantic era: sensual and intellectual, though not overly so, and, because indulgence was miraculously tempered by a certain unstated restraint, popular. In the last post, we touched on the debate between poetry and lyrics: while music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry, poetry is its own music, condemning it to be naked, without music, forever. I don't know which I feel sorrier for. Some will say the two can never be reconciled. Madness and torture! Why do they exist, never to meet! Poetry and music! Divided heart! Divided mind! Poor, divided mankind! (Dramatic, huh?)

Oh, poppycock, of course, they do; they meet and have an illicit affair, and if an especially beautiful melody accompanies the words of a particular lyric, making the words even more lovely, do we assume the words are responsible or has the music inspired the words?

For the research here, and because Leslie Gore didn't qualify, I found myself in realism-mode, the Brönte factor, and in its simplicity and constructive realism, adding in a dose of repetition to make Mark Twain proud, I chose McCartney's aforementioned "Why Don’t We Do It In the Road."

Love it or hate it, celebrate it or be embarrassed by it, "Why Don't We Do It In The Road?" showed that the Fab Four were more than peace, love and flowers (or is the song the essence of the hippie trinity?). Some might call it bold (particularly from McCartney), yet something like this had to be expected, especially on an album with a plain white cover, as if something subversive was inside. After the furor caused by John's "We're bigger than Jesus" statement, and the banned songs by the BBC due to drug references, not to mention John and Yoko's full frontal on the cover of Two Virgins, why not compose a song about the most absurdly taboo subject imaginable and see how many feathers could be ruffled?

"The idea behind 'Why Don't We Do It In The Road' came from something I'd seen in Rishikesh," Paul explained. "I was up on the flat roof meditating and I'd seen a troupe of monkeys walking along in the jungle and a male just hopped on to the back of this female and gave her one, as they say in the vernacular. Within two or three seconds he hopped off again, and looked around as if to say, 'It wasn't me,' and she looked around as if there had been some mild disturbance but thought, 'Huh, I must have imagined it,' and she wandered off.

"And I thought, 'Bloody hell, that puts it all into a cocked hat.' That's how simple the act of procreation is, this bloody monkey just hopping on and hopping off. There is an urge, they do it, and it's done with. And it's that simple. We have horrendous problems with it, and yet animals don't.” While Paul’s account makes it simply rudimentary, it also takes out the romance. Frankly, doesn't the song express our basic instincts, not just in a physical manner, indeed in this respect we’re like animals, but in an obliquely human way as well: "WDWDIITR" is all about the romance of lust. How Byronic is that?

So, back to the train. Monkeys just do it in the road. We take our time. We get on a train. We sit together and chat, forget about the ride, forget about the destination; it's all, at least for now, about the journey. And yet, in the nuance of the encounter, you contemplate her smile, the fullness of her breasts, his scruffy cool, and in your mind you just want to push him/her up against... Those thoughts wind through your mind, come and go, the question building, insistent, louder and louder. First, it's a question; then it's a plea:

Why don't we do it in the road?No one will be watching us

Why don't we do it in the road?

Published on February 23, 2018 06:02

No one will be watching us,

The video above has nothing at all to do with our topic; just something interesting I found doing my research.

Published on February 23, 2018 06:00

February 22, 2018

Rock Lyrics as Poetry

A colleague asked another for his favorite poem (we are an eclectic collection of English teachers, mind you). My colleague’s fave is "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and immediately upon his admission of the T.S. (that's Tough Shit) Eliot tome, I blurted out, as a fellow English teacher will do: "I have measured out my life in coffee spoons." Though hardly lighthearted, "Prufrock" is one of Eliot's most accessible poems (aside from Cats), a far cry from the preposterously sullen The Waste Land, his most critically acclaimed work. I would agree that "Prufrock" is an astute choice.

A colleague asked another for his favorite poem (we are an eclectic collection of English teachers, mind you). My colleague’s fave is "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and immediately upon his admission of the T.S. (that's Tough Shit) Eliot tome, I blurted out, as a fellow English teacher will do: "I have measured out my life in coffee spoons." Though hardly lighthearted, "Prufrock" is one of Eliot's most accessible poems (aside from Cats), a far cry from the preposterously sullen The Waste Land, his most critically acclaimed work. I would agree that "Prufrock" is an astute choice.The other teacher's response to the question was "Sounds of Silence." I forget the word my colleague used to describe the choice; pedantic, maybe, or sophomoric. His response to me was that no rock lyric could rate beside Eliot or Dylan Thomas, et al. Despite his opinionated brilliance, I couldn't disagree with him more. I took the defense of the other teacher to heart, quoting Springsteen, "The screen door slams,/ Mary's dress waves./ Like a vision she dances across the floor as the radio plays/ Roy Orbison singing, 'For the Lonely.'" Eliot, the disenfranchised American from Ohio, may indeed expertly capture the Brit soul, but "Thunder Road" is pure Americana, and like "Prufrock," plays with words and phrasing in an equally stylistic manner. The subtle rhyme, the enjambment within the lines making "as the radio plays" an American expression of incidental background music in general, but then, in the next line peppering the small town feel with Roy Orbison's iconic single, is genius.

My colleague's view is that it's always the music, and not the lyrics that provide the greater emotional impact, and yet the phatic is common to both song lyrics and poetry; music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry – forever – while poetry is its own pseudo music, damning it to a netherworld without melody. That in mind, maybe the choice of "Sounds of Silence" is indeed pedantic. The lyrics themselves sophomoric; one might call it kitsch. It’s not Simon's strongest lyric by any means, but that doesn’t discount Simon. From his play with John Donne in "I am a Rock," dismissing Donne’s ideology that no man is an island, to the sublime "America," which, like "Thunder Road" captures American Youth in its most restless, the twenty-five-year-old Simon was equal at least to the worst of Dylan Thomas, himself a drunken rock star, and rivals at times Thomas at his most okay, that “second chair” that Thomas, based on his alcohol distraction, sat in on many occasions.

My colleague's view is that it's always the music, and not the lyrics that provide the greater emotional impact, and yet the phatic is common to both song lyrics and poetry; music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry – forever – while poetry is its own pseudo music, damning it to a netherworld without melody. That in mind, maybe the choice of "Sounds of Silence" is indeed pedantic. The lyrics themselves sophomoric; one might call it kitsch. It’s not Simon's strongest lyric by any means, but that doesn’t discount Simon. From his play with John Donne in "I am a Rock," dismissing Donne’s ideology that no man is an island, to the sublime "America," which, like "Thunder Road" captures American Youth in its most restless, the twenty-five-year-old Simon was equal at least to the worst of Dylan Thomas, himself a drunken rock star, and rivals at times Thomas at his most okay, that “second chair” that Thomas, based on his alcohol distraction, sat in on many occasions. The songwriter who captures best the idea of the poet is Bob Dylan (whose name, of course, comes from Dylan Thomas). Dylan is such an idiosyncratic genius that it's perilous to imitate him; his faults, at worst annoying, at best invigorating, ruin lesser talents. But contrary to the mythology (and to the Nobel Prize), the man did not revolutionize modern poetry, American folk, popular music, or the whole of modern thought; and the Village Voice, prattling on about "new plateaus for poetic, content-conscious songwriters" and "the bastard child of Chaplin, Celine and Hart Crane," is nothing, if not ludicrous. However inoffensive (at worst) or haunting (at best) "The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face" sounds on vinyl, it's plain silly without the music. Conversely, "My Back Pages" is a bad poem, though it's a great song with an unforgettable refrain. Music softens our demands, the importance of what is being said somehow overbalances the flaws, and Dylan's delivery adds an edge not present in the words. Add to that the premise that if the words don't work, one can always mumble, and you've realized the perfect formula. (That said, when Dylan won the Nobel Prize every poet and novelist in the world, myself included, threw up a little in his mouth. I mean really? Solzhenitsyn, Steinbeck, Kipling, Hemingway, Camus, Faulkner, Eliot, Churchill?)

In the same vein, The Mamas and Papas are full of diversions: contrapuntal arrangements, orchestral improvisations, odd rhyme schemes and John Phillips' trick of drawing out words with repetitions and pauses. In songs like "California Dreamin'," "12:30" and so many others, Phillips is obviously a good lyricist, though his lyrics are rarely easy to understand. I wonder how many are aware that "Strange Young Girls" is about LSD. No secret about it; it's right there out in the open in the first stanza: "Walking the Strip, sweet, soft, and placid/ Off'ring their youth on the altar of acid." But no one notices because there's so much within the song’s stellar arrangement. On a crude level this vagary permits the kind of one-to-one symbolism of pot songs like "Along Comes Mary."

In the same vein, The Mamas and Papas are full of diversions: contrapuntal arrangements, orchestral improvisations, odd rhyme schemes and John Phillips' trick of drawing out words with repetitions and pauses. In songs like "California Dreamin'," "12:30" and so many others, Phillips is obviously a good lyricist, though his lyrics are rarely easy to understand. I wonder how many are aware that "Strange Young Girls" is about LSD. No secret about it; it's right there out in the open in the first stanza: "Walking the Strip, sweet, soft, and placid/ Off'ring their youth on the altar of acid." But no one notices because there's so much within the song’s stellar arrangement. On a crude level this vagary permits the kind of one-to-one symbolism of pot songs like "Along Comes Mary." All this in mind, one is indeed hard-pressed to take a stance for rock music as poetry. Morrison’s "The End" is pedantic, to use my colleague's words, and The Police's "Don't Stand So Close to Me," sophomoric. But I can indeed go back to Simon: "What a dream I had… Pressed in organdy/ Clothed in crinoline of smoky burgundy/ Softer than the rain/ I wandered empty streets down past the shop displays/ I heard cathedral bells tripping down the alleyways/ As I walked on…" It’s Simon but it could be Shelley; alter the demeanor or the known cadence, it could be Emily Dickenson.

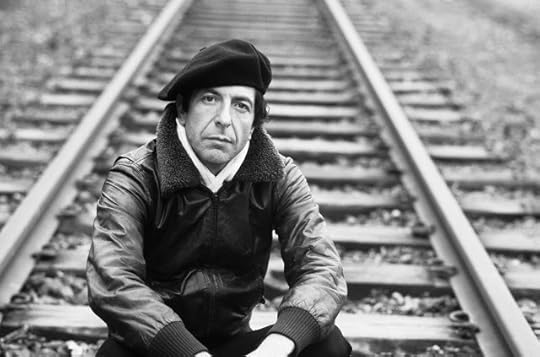

I don't even have to say a thing about Sincerely, L. Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat": "It's four in the morning, the end of December/ I'm writing you now just to see if you're better/ New York is cold, but I like where I'm living/ There's music on Clinton Street all through the evening. - I hear that you're building your little house deep in the desert/ You're living for nothing now, I hope you're keeping some kind of record. - Yes, and Jane came by with a lock of your hair/ She said that you gave it to her/ That night that you planned to go clear./ Did you ever go clear?

I don't even have to say a thing about Sincerely, L. Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat": "It's four in the morning, the end of December/ I'm writing you now just to see if you're better/ New York is cold, but I like where I'm living/ There's music on Clinton Street all through the evening. - I hear that you're building your little house deep in the desert/ You're living for nothing now, I hope you're keeping some kind of record. - Yes, and Jane came by with a lock of your hair/ She said that you gave it to her/ That night that you planned to go clear./ Did you ever go clear?Tom Waits wrote "Tom Traubert's Blues" after visiting Skid Row in Los Angeles, drinking a pint of rye and throwing up: "Wasted and wounded, it ain't what the moon did, I've got what I paid for now/ See you tomorrow, hey Frank, can I borrow a couple of bucks from you/ To go waltzing Mathilda, waltzing Mathilda,/ You'll go waltzing Mathilda with me." It’s Bukowski, that (but does it fly without the Aussie nursery rhyme?).

For simplicity through repetition on the basic human desire, maybe McCartney did it best: "Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ No one will be watching us,/ Why don't we do it in the road?" It's Twain simplicity and honesty, and daring for the 60s, with the next progression of theme and style going to Anthony Kiedis of Red Hot Chili Peppers: "Let me shine your diamond/ The girl got a scratch/ Slap that cat/ Have mercy - I want to party on your pussy, baby/ I want to party on, party on your pussy/ I want to party on your pussy, baby/ I want to party on your pussy, yeah, yeah, yeah."

From Joni Mitchell's Blue to Dark Side of the Moon, the poetry is there, often hidden within the music or the arrangements; what an unfair advantage. Poetry without it is a dying art. Ho-hum. I guess we will be seeing a lot more Dylans joining the 113 recipients of the Nobel (hopefully there are budding Plaths and Cummings out there to prove me wrong). In the meantime: "My head is my only house unless it rains." Yep, shear poetry.

My favorite rock lyrics? Fleetwood Mac's "Landslide." I have no delusions about Nicks' lyrics vs. any "great" poetry, but the question was my favorite lyrics; not the greatest. My favorite poem, btw? "Shake and shake the ketchup bottle,/ None'll come and then a lot'll."

Published on February 22, 2018 09:55

February 21, 2018

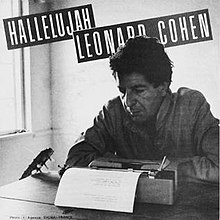

Hallelujah - Leonard Cohen

Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" is a complex, nearly indecipherable musical riddle that baffled even its composer. Originally released as a synth-laden dirge on 1984's Various Positions, Cohen spent years tinkering with the track during live performances in a relentless pursuit to unlock its full potential. By now, "Hallelujah" has become a cultural staple, covered by dozens of artists, most notably John Cale and Jeff Buckley (playing in the music loop as well as in the current Winter Olympics). Others to take up the hymn are Bon Jovi, Rufus Wainwright, Regina Spektor, Michael McDonald, Norah Jones, Justin Timberlake, k.d. lang, Bono and Willie Nelson.

Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" is a complex, nearly indecipherable musical riddle that baffled even its composer. Originally released as a synth-laden dirge on 1984's Various Positions, Cohen spent years tinkering with the track during live performances in a relentless pursuit to unlock its full potential. By now, "Hallelujah" has become a cultural staple, covered by dozens of artists, most notably John Cale and Jeff Buckley (playing in the music loop as well as in the current Winter Olympics). Others to take up the hymn are Bon Jovi, Rufus Wainwright, Regina Spektor, Michael McDonald, Norah Jones, Justin Timberlake, k.d. lang, Bono and Willie Nelson. The fascinating story of how "Hallelujah" transformed from disappointing album track to legendary status is the stuff of a myriad of articles from Rolling Stone to the New Yorker. It's interesting how popular the song has become despite our outwardly secular world. Cohen's song, is, after all, a mash-up of references to the biblical King David. The opening line evokes the tradition of David as a musician and composer "Now I heard there was a secret chord that David played and it pleased the Lord." But throughout Cohen's song, David the musician shares the stage with David the lover/adulterer as in a retelling of 2 Samuel 11-12: "Your faith was strong but you needed proof. You saw her bathing roof. Her beauty in the moonlight overthrew ya."

Cohen freely and creatively peppers his retelling of David's life with other biblical stories; Samson's relationship with Delilah, for instance, exercises a profound influence on Cohen's song, though when it comes to David's encounter with Bathsheba, Cohen's David is not the initiator of wrongdoing; he is a victim of forces beyond his own control:

Cohen freely and creatively peppers his retelling of David's life with other biblical stories; Samson's relationship with Delilah, for instance, exercises a profound influence on Cohen's song, though when it comes to David's encounter with Bathsheba, Cohen's David is not the initiator of wrongdoing; he is a victim of forces beyond his own control:Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew you.She tied you to a kitchen chair. She broke your throne, and she cut your hair. And from your lips she drew the Hallelujah.

In these stunning lines, the roles have been reversed and Bathsheba is the main actor, while everything happens to a passive David. It's a twist on Bathsheba more characteristic of Delilah, but you get the point.

While the reference to scripture is undeniable (this is not simply a symbolic tract), the song’s switch to first-person speech ("I did my best, it wasn’t much. I couldn’t feel, so I tried to touch") make it a personal confession wrapped in a powerful narrative that establishes an empathy that we couldn't otherwise share with the biblical David. Our vision of David, the giant slayer, is that of the overwhelming 17 foot statue by Michelangelo – Godlike in stature. Cohen's David instead is just about an unremarkable guy in a remarkable situation.

Published on February 21, 2018 14:29