R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 82

March 20, 2018

The Radical Muse

The Laurel Canyon artists, among them Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, David Crosby and John Phillips, took a naturalistic bent, a Steinbeckian way of looking at things, one that someone would film steeped in burnt sienna. It was a far cry from The Beatles, further still from their neighbor down the way on Love Street, but it was Mitchell who fashioned the words into insolences and attitudes, words that could cut.

The Laurel Canyon artists, among them Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, David Crosby and John Phillips, took a naturalistic bent, a Steinbeckian way of looking at things, one that someone would film steeped in burnt sienna. It was a far cry from The Beatles, further still from their neighbor down the way on Love Street, but it was Mitchell who fashioned the words into insolences and attitudes, words that could cut.In "Woman of Heart and Mind," Joni Mitchell relies on her intellect and rhetorical prowess to assert her identity and defy masculine objectification. In verse one, she sings: "You think I'm like your mother/ Or another lover or your sister/ Or the queen of your dreams." Herein she recognizes the masculine tendency to physicalize the feminine, to view women as objects of psycho-sexual desire. In response, she declares: "I am a woman of heart and mind/ With time on her hands/ No child to raise..." Mitchell defies the male-defined feminine paradigm by identifying as an emotionally and intellectually liberated being, rather than as a woman bound by her carnality and physicality. She readily criticizes the hubristic excesses of her male lover, essentially calling them fruitless and unfulfilling: "After the rush when you come back down/ You're always disappointed/ Nothing seems to keep you high/ Drive your bargains/ Push your papers/ Win your medals/ Fuck your strangers/ Don't it leave you on the empty side?" "You want stimulation," she ponders, "nothing more, that's what I think." Meanwhile, she cleverly understates her own desires, asking only for "a little passion." Like Steinbeck, Mitchell’s characters are simplistic, everyday lovers and others; the complexity hidden deep within, with hiddena key term. Joni’s character seems to love himdespite a laundry list of selfishness.

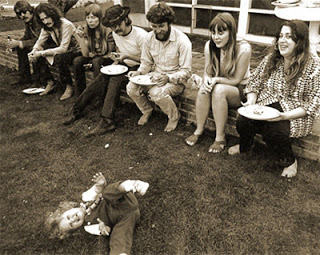

Pic Dawson, Eric Clapton, Joni, David Crosby, Gary

Pic Dawson, Eric Clapton, Joni, David Crosby, GaryBurdon, Annie Burden and Cass Elliot.While The Beatles were immersing themselves in a British pastiche, and Morrison was off on a mindbender that could rival Carlos Casteneda, Joni and her contemporaries were creating their own cinema verite, but unlike The Beatles’ plunge into Modernism, Joni whittled down relationships in a manner that women chalked off and men misconstrued ("Fuck your strangers," is like a badge of honor to this guy – or so it seems – we never get his side of the story).

We can’t conclude, though, that The Beatles' broad strokes are less complex than Joni’s. Think once again of the nuances afforded "She's Leaving home" (here we indeed find the ability to capture both sides of the story). The listener is hard pressed not feel pulled from side to side, the sorrow and angst of the parents or the soul searching of an oppressed young woman (coupled with the intense beauty of Paul's tearful melody) shows we have heart, and, like the Scarecrow, we know, because it is breaking. No, Joni’s is a different sorrow, deeper, again like a cut, a paper cut. It’s Joni who follows Hemingway's lead, sits down at the typewriter and cuts her wrists.

Published on March 20, 2018 04:09

March 19, 2018

The Muse, Loneliness and Monterey Pop

There is no arguing the shiny patina that AM perpetuates, a policy that focuses on how rock music has elevated our lives, and not on how much so many factions of the industry suck. We don't talk about Drakes's mediocrity or Beyonce's ridiculous celebrity, or even how overrated Adele is, we just feel bad that that's all the masses want, nothing more than Disney girls and sophomoric rap (thank God for Kendrick Lamar). Instead we focus on rock's Belle Époque or the 21st Century's version of the Laurel Canyon sound so obvious in Lord Huron or Fleet Foxes.

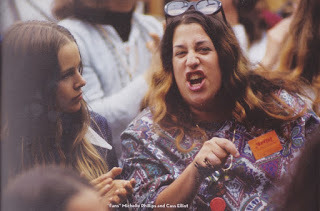

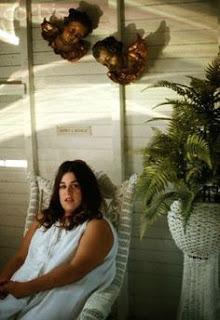

There is no arguing the shiny patina that AM perpetuates, a policy that focuses on how rock music has elevated our lives, and not on how much so many factions of the industry suck. We don't talk about Drakes's mediocrity or Beyonce's ridiculous celebrity, or even how overrated Adele is, we just feel bad that that's all the masses want, nothing more than Disney girls and sophomoric rap (thank God for Kendrick Lamar). Instead we focus on rock's Belle Époque or the 21st Century's version of the Laurel Canyon sound so obvious in Lord Huron or Fleet Foxes.We do tend erroneously to gloss over factors that puncture the mythology. For Mama Cass that gloss-over was her inherent loneliness. Despite the throngs that surrounded Cass, her weight curtailed her romantic endeavors. Couple that with the supermodel beauty of Michelle Phillips and we find in Cass the plight of the "fat girl" in high school who everyone liked, but who never had the romance she so desired. When I was little, I got the H.R. Pufinstuf soundtrack for Christmas. My favorite song was Mama Cass's "Different," in which she laments being a fat witch (video). I'd sing along: "Different is hard, different is lonely/ Different is trouble for you only/ Different is heartache, different is pain/ But I'd rather be different than be the same." Cass's weight would lead to depression despite her successes and despite her friends; the Queen of Laurel Canyon was different, and lonely. That depression metastasized in both drugs and work, and would kill her all too soon, of heart failure (not choking on a sandwich as the myth would dictate) at the age of 32, in the midst of a sold out series of shows at the London Palladium (July 29, 1974). Some would point to continued drug use (the official cause of death listed as heart failure).

In a 1988 memoir, David Crosby said, "Me and Cass Elliot were closet junk takers and used to get loaded with each other a lot. We loved London because there was pharmaceutical heroin available in drugstores; Government dope, in these injectable tablets that you crushed and dissolved in order to shoot them. Me and Cass used to just mash them up and snort the powder. Cass took lots of pills, usually from the opiate family: Dilaudid, Demerol, Percodan, downers of all sorts, and we did a lot of coke together." There was indeed a dark side to the Queen of Laurel Canyon – she was no Gertrude Stein (Gertrude Stein was no Gertrude Stein). AM is guilty of perpetuating a myth, but justify it as highlighting the positives.

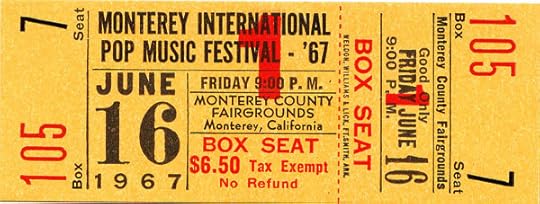

In a 1988 memoir, David Crosby said, "Me and Cass Elliot were closet junk takers and used to get loaded with each other a lot. We loved London because there was pharmaceutical heroin available in drugstores; Government dope, in these injectable tablets that you crushed and dissolved in order to shoot them. Me and Cass used to just mash them up and snort the powder. Cass took lots of pills, usually from the opiate family: Dilaudid, Demerol, Percodan, downers of all sorts, and we did a lot of coke together." There was indeed a dark side to the Queen of Laurel Canyon – she was no Gertrude Stein (Gertrude Stein was no Gertrude Stein). AM is guilty of perpetuating a myth, but justify it as highlighting the positives. In 1967, after a disastrous Las Vegas show (that was ultimately cancelled after just one night due to medical issues and poor reviews), Cass would immerse herself in Monterey Pop. Monterey was the first great outdoor rock concert and the precursor to Woodstock two years later. Over the weekend of June 16, 100,000 festival goers would converge on a disused fairground 50 miles south of San Francisco (near Carmel, California). The brainchild of John Phillips and Lou Adler, Cass, at first reluctant to get involved, would play an instrumental role in the festival's success, which would feature The Who, Hendrix, Janis, Jefferson Airplane and, of course, The Mamas and the Papas. Cass's longtime boyfriend at the time, Lee Kiefer of The Hard Times Band, summed it up: "It was a couple days of absolute camaraderie. There are just no words. Motorcycle policemen running around with their bikes covered in flowers with thirty foot strings of pink and white balloons off the back of their bikes. We stayed up for the whole thing and didn't miss anything. Ravi Shankar's performance was incredible, but we liked them all. All the performances by everyone were supercharged. There were no fights, no murders, no deaths, no bludgeonings, you know what I mean? No dwarves ran away with the ring. No human sacrifice! And she went to see everybody."

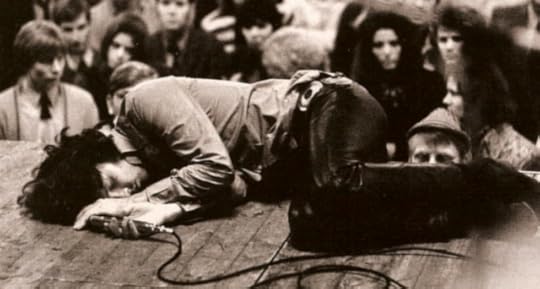

In 1967, after a disastrous Las Vegas show (that was ultimately cancelled after just one night due to medical issues and poor reviews), Cass would immerse herself in Monterey Pop. Monterey was the first great outdoor rock concert and the precursor to Woodstock two years later. Over the weekend of June 16, 100,000 festival goers would converge on a disused fairground 50 miles south of San Francisco (near Carmel, California). The brainchild of John Phillips and Lou Adler, Cass, at first reluctant to get involved, would play an instrumental role in the festival's success, which would feature The Who, Hendrix, Janis, Jefferson Airplane and, of course, The Mamas and the Papas. Cass's longtime boyfriend at the time, Lee Kiefer of The Hard Times Band, summed it up: "It was a couple days of absolute camaraderie. There are just no words. Motorcycle policemen running around with their bikes covered in flowers with thirty foot strings of pink and white balloons off the back of their bikes. We stayed up for the whole thing and didn't miss anything. Ravi Shankar's performance was incredible, but we liked them all. All the performances by everyone were supercharged. There were no fights, no murders, no deaths, no bludgeonings, you know what I mean? No dwarves ran away with the ring. No human sacrifice! And she went to see everybody." In the Audience for JanisThe party, and the Salon, continued between performances, as Cass held court in a backstage tent, truly in her element. These were all friends and many of them had gained their success at least partially due to Cass. These salon sessions were the keystone to Monterey, even if The Mamas and the Papas' performance was not. Hours before the gig, Denny Doherty, the singing lead of the quartet, was nowhere to be seen. He'd had no stock or interest in Monterey Pop, resenting even the time and effort put into its organization by John and Michelle. Based on their hectic schedule, the band hadn’t rehearsed as a unit in more than three months. Cass and Michelle, clearly nervous but passing the time before their appearance just offstage for Hendrix, found themselves in awe of Jimi’s stage antics. Hendrix' sublime performance (one far better than what would follow at Woodstock), eased the girl’s minds: it wouldn’t really matter how well The Mamas and the Papas performed – no one would remember anything but Hendrix. Just 45-minutes prior their performance, Doherty finally arrived, just in time to see The Who destroy the stage and Hendrix light his guitar on fire.

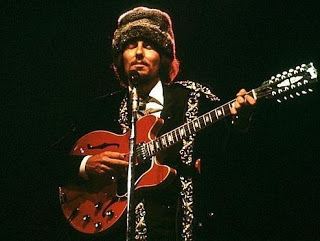

In the Audience for JanisThe party, and the Salon, continued between performances, as Cass held court in a backstage tent, truly in her element. These were all friends and many of them had gained their success at least partially due to Cass. These salon sessions were the keystone to Monterey, even if The Mamas and the Papas' performance was not. Hours before the gig, Denny Doherty, the singing lead of the quartet, was nowhere to be seen. He'd had no stock or interest in Monterey Pop, resenting even the time and effort put into its organization by John and Michelle. Based on their hectic schedule, the band hadn’t rehearsed as a unit in more than three months. Cass and Michelle, clearly nervous but passing the time before their appearance just offstage for Hendrix, found themselves in awe of Jimi’s stage antics. Hendrix' sublime performance (one far better than what would follow at Woodstock), eased the girl’s minds: it wouldn’t really matter how well The Mamas and the Papas performed – no one would remember anything but Hendrix. Just 45-minutes prior their performance, Doherty finally arrived, just in time to see The Who destroy the stage and Hendrix light his guitar on fire. The Mamas and the Papas performance was lackluster at best, the harmonies flat, the audience distracted, but it didn’t matter. It was their presence that culminated the show. John had finally relented in his insistence that the quartet dress the hippie role, the girls without make-up, the guys in jeans, but The Beatles, with Sgt. Pepper, had made hippie chic. Cass, who'd always wanted to glam it up, dressed in a silk, brightly colored caftan similar to an Indian sari. Michelle, alongside the elite hipsters of the time, like Mia Farrow, shopped at a smart little boutique in Hollywood called Profile du Monde, and wore a similar caftan in copper silk and gold lame. Doherty wore a knee length silk paisley Nehru jacket, and John a hipster's suit and tie with a fur hat like a trapper. While the performance was far from the band's best, the aura of the moment prevailed. The quartet, sans Doherty, had orchestrated what few would argue as the best of the outdoor superconcerts, including Woodstock. For Cass, it was the unrealized culmination of what she had "worked" for all these years as the Queen of Laurel Canyon.

The Mamas and the Papas performance was lackluster at best, the harmonies flat, the audience distracted, but it didn’t matter. It was their presence that culminated the show. John had finally relented in his insistence that the quartet dress the hippie role, the girls without make-up, the guys in jeans, but The Beatles, with Sgt. Pepper, had made hippie chic. Cass, who'd always wanted to glam it up, dressed in a silk, brightly colored caftan similar to an Indian sari. Michelle, alongside the elite hipsters of the time, like Mia Farrow, shopped at a smart little boutique in Hollywood called Profile du Monde, and wore a similar caftan in copper silk and gold lame. Doherty wore a knee length silk paisley Nehru jacket, and John a hipster's suit and tie with a fur hat like a trapper. While the performance was far from the band's best, the aura of the moment prevailed. The quartet, sans Doherty, had orchestrated what few would argue as the best of the outdoor superconcerts, including Woodstock. For Cass, it was the unrealized culmination of what she had "worked" for all these years as the Queen of Laurel Canyon.

One final vignette of note. Cass, like Gertrude Stein, welcomed all into her entourage, and whether you were Jackson Browne or Joe Schmo, you got the same focus and attention. But Cass wasn't always the "Fat Angel" and her outcast experiences in grade school left their mark. After a Mamas and the Papas show in New York, a bevy of sophisticated, one-time sorority girls from Forest Park came backstage, their wealthy husbands in tow. When one, Mimi Seligman, greeted Cass as if they were old pals, Cass responded, "You didn’t know me then, and you don’t know me now." In reality, there aren't many of the bullied who truly get to exact their revenge. Cass would tell that story the rest of her life.

Published on March 19, 2018 19:03

Jay and the Americans - $1.99! - All this week!

Once again AM is running a Kindle promo starting March 19! For a limited time, you can read Jay and the Americans on your handheld device for just a $1.99. Just click on the Kindle sidebar.

Please don't forget to leave a review on Amazon! For those of you who want the real deal, Jay is available on Amazon world wide and on CreateSpace, and those of you who have Kindle Unlimited can still read the novel for free. Sales of Jay go directly back into the website and into the publication of my next novel Miles From Nowhere. More than sales, your reviews help AM grow. Please help to support the novel and your fave rock 'n' roll website!

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UK

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UKAmazon France - Amazon Russia

Published on March 19, 2018 19:03

The Muse of Liverpool and L.A.

When the Beatles finished the recording of Sgt. Pepper in late April 1967 (the 21st to be exact), they retired, the mythology goes, to Mama Cass's flat in Chelsea at around 2am. We’ve talked before about the Gertrude Stein of Laurel Canyon, but Cass Eliot’s hand in music is far reaching. With acetate of the LP in hand, the Beatles piled into the apartment, Cass sprawled across the settee – can you picture it? – the mustachio'd Fab Four sitting cross-legged on the floor. Ringo, I'm speculating the details here, put the LP on the phonograph, opened the windows and the incredible strains of Sgt. Pepper & Co. wafted magically, Peter Maxily down onto the streets of sleepy London. It's one of rock's beautiful vignettes, and maybe it's even true. The Beatles immersed London, and the world at large, in an incredible feat of psychedelic realism. (Indeed, I'm coining the phrase right now.)

When the Beatles finished the recording of Sgt. Pepper in late April 1967 (the 21st to be exact), they retired, the mythology goes, to Mama Cass's flat in Chelsea at around 2am. We’ve talked before about the Gertrude Stein of Laurel Canyon, but Cass Eliot’s hand in music is far reaching. With acetate of the LP in hand, the Beatles piled into the apartment, Cass sprawled across the settee – can you picture it? – the mustachio'd Fab Four sitting cross-legged on the floor. Ringo, I'm speculating the details here, put the LP on the phonograph, opened the windows and the incredible strains of Sgt. Pepper & Co. wafted magically, Peter Maxily down onto the streets of sleepy London. It's one of rock's beautiful vignettes, and maybe it's even true. The Beatles immersed London, and the world at large, in an incredible feat of psychedelic realism. (Indeed, I'm coining the phrase right now.)  The realism of Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields brought home on a 40 minute endeavor (39:52). McCartney’s Fixin' a Hole is a psychedelic masterpiece, as is Lennon's Lucy, but the undercurrent in the LP is the realism of a girl leaving home ("She's Leaving Home" so expertly weaving the tale from both sides of the generation gap) and a meter maid and the mundane episodes of the News of the Day. The LP's inspiration, whether stemming from out of dance halls or Lonely Hearts Clubs or Lennon's disassociation from family, are firmly rooted in a British Realism that wouldn't be lost on Emily Bronte. There are naysayers of course. Aimee Mann, you know the "voices carry' girl said, "I'm burnt out on it [that part I'll buy]. It's influence has been so vast and profound, but it lacks emotional depth." She prefers the stylings of Elliot Smith and Fiona Apple. So she’s stupid – hush, hush, Aimee – despite AM's fondness for both Smith and Apple. Mostly though, you and I know, this is the rock masterpiece.

The realism of Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields brought home on a 40 minute endeavor (39:52). McCartney’s Fixin' a Hole is a psychedelic masterpiece, as is Lennon's Lucy, but the undercurrent in the LP is the realism of a girl leaving home ("She's Leaving Home" so expertly weaving the tale from both sides of the generation gap) and a meter maid and the mundane episodes of the News of the Day. The LP's inspiration, whether stemming from out of dance halls or Lonely Hearts Clubs or Lennon's disassociation from family, are firmly rooted in a British Realism that wouldn't be lost on Emily Bronte. There are naysayers of course. Aimee Mann, you know the "voices carry' girl said, "I'm burnt out on it [that part I'll buy]. It's influence has been so vast and profound, but it lacks emotional depth." She prefers the stylings of Elliot Smith and Fiona Apple. So she’s stupid – hush, hush, Aimee – despite AM's fondness for both Smith and Apple. Mostly though, you and I know, this is the rock masterpiece. That same year, The Doors followed a different muse. Within the tracks of The Doors, Morrison unleashes Greek tragedy (and the mother thing, no less, from Oedipus Rex), Willie Dixon-styled let's fuck ambiguities, millennial Celtic myths and a psychedelia the challenged us all to break on through to the other side and to read the likes of Artaud, Brecht and Huxley. Of course, The Doors owe even their name to Morrison's muse, a nod to Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, which chronicles the author's experience of taking the mind-altering drug mescaline. The literary reference goes even deeper as Huxley's title is taken from a line in William Blake's "The Marriage of Heaven and Hell": "If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite."

That same year, The Doors followed a different muse. Within the tracks of The Doors, Morrison unleashes Greek tragedy (and the mother thing, no less, from Oedipus Rex), Willie Dixon-styled let's fuck ambiguities, millennial Celtic myths and a psychedelia the challenged us all to break on through to the other side and to read the likes of Artaud, Brecht and Huxley. Of course, The Doors owe even their name to Morrison's muse, a nod to Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, which chronicles the author's experience of taking the mind-altering drug mescaline. The literary reference goes even deeper as Huxley's title is taken from a line in William Blake's "The Marriage of Heaven and Hell": "If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite."  In 1969, Morrison would write (and distribute to concert goers at the Aquarius Theater in the form of a flyer – July 21st) "Ode to L.A., While Thinking of Brian Jones, Deceased," which, in addition to depicting the first truly publicized death of the rock era, was a throwback to Willy the Shake. Morrison writes, "I'm a resident of a city/ They’ve just picked me to play/ the Prince of Denmark…" The poet feels himself Hamlet – and although in our modern age the idea may seem banal, the existential problem of to-be-or-not-to-be, to exist or not, is one of poetry's essentials. And indeed, death is central in Morrison's poetry.

In 1969, Morrison would write (and distribute to concert goers at the Aquarius Theater in the form of a flyer – July 21st) "Ode to L.A., While Thinking of Brian Jones, Deceased," which, in addition to depicting the first truly publicized death of the rock era, was a throwback to Willy the Shake. Morrison writes, "I'm a resident of a city/ They’ve just picked me to play/ the Prince of Denmark…" The poet feels himself Hamlet – and although in our modern age the idea may seem banal, the existential problem of to-be-or-not-to-be, to exist or not, is one of poetry's essentials. And indeed, death is central in Morrison's poetry. Morrison as a true visionary poet forsaw (word?) volumes (at least in his own mind) and predicted his own death (or talked about it a lot - how'd that for vaguery?). "Ode to L.A.," devoted to Brian Jones, whose mysterious death in a swimming pool influenced Morrison, provoked him into writing a poem languorous with images of water, pools and dead bodies: "…Poor Ophelia/ All those ghosts he never saw/ Floating to doom/ On an iron candle/ Come back, brave warrior/ Do the dive/ On another channel". I make no reference to brilliance here, there is none, only to Morrison's use of the muse.

Another reticent image in Morrison's poetry is the "Far Arden." Far Arden is known to the reader from Shakespeare's As You Like It. In Morrison's poetry Far Arden symbolizes freedom, joy and music, a mystic forest where songs and dances rule: "Ladies & gentlemen:/ please attend carefully to these words & events/ It’s your last chance, our last hope./ In this womb or tomb, we’re free of the swarming streets." Morrison interpreted Shakespeare's images through his own scope of vision as a poet born in the 20th century whose poetic style was worked out in existential philosophy combined with the tradition of visionary poets, Indian religion and the American avant-garde of the 50s. Morrison was worlds away from the Brit Realism of Lennon/McCartney, but equally far away from the naturalist style of the Laurel Canyon set with whom he lived among, often venturing up the canyon to Mama Cass’s house, the two having known one another since high school in Alexandria Virginia. Though not particularly chummy in the Canyon, one can imagine the same muse in Cass that the Beatles encountered.

Another reticent image in Morrison's poetry is the "Far Arden." Far Arden is known to the reader from Shakespeare's As You Like It. In Morrison's poetry Far Arden symbolizes freedom, joy and music, a mystic forest where songs and dances rule: "Ladies & gentlemen:/ please attend carefully to these words & events/ It’s your last chance, our last hope./ In this womb or tomb, we’re free of the swarming streets." Morrison interpreted Shakespeare's images through his own scope of vision as a poet born in the 20th century whose poetic style was worked out in existential philosophy combined with the tradition of visionary poets, Indian religion and the American avant-garde of the 50s. Morrison was worlds away from the Brit Realism of Lennon/McCartney, but equally far away from the naturalist style of the Laurel Canyon set with whom he lived among, often venturing up the canyon to Mama Cass’s house, the two having known one another since high school in Alexandria Virginia. Though not particularly chummy in the Canyon, one can imagine the same muse in Cass that the Beatles encountered.

Published on March 19, 2018 11:02

March 18, 2018

The Muse and Me

On a personal note, one would think, as a writer, that my muse would be Hemingway or Steinbeck, and in a way, particularly with Steinbeck, these are the writers who sparked my interest in prose, but it has always been music that proves the muse. I play no instrument. I own a guitar and I've picked it up seven or eight times over the years, then I realize that we're out of milk and I have to go to the A&P. On my way there, and I take the long way, it's Lord Huron or Neil Young or Talking Heads on Spotify.

On a personal note, one would think, as a writer, that my muse would be Hemingway or Steinbeck, and in a way, particularly with Steinbeck, these are the writers who sparked my interest in prose, but it has always been music that proves the muse. I play no instrument. I own a guitar and I've picked it up seven or eight times over the years, then I realize that we're out of milk and I have to go to the A&P. On my way there, and I take the long way, it's Lord Huron or Neil Young or Talking Heads on Spotify. I remember my stepfather picking up his old Gretsch, strumming a few chords and then playing a familiar riff. I have no idea what it was, and I don't suppose, particularly with his passing, that I ever will, but it's stuck with me, it pervades my senses. I hear it in my mind, but then instantly instead, a more familiar, though similar, riff overtakes my senses. My stepfather's arpeggio mimicked the picking in Led Zeppelin's beautiful "The Rain Song." And for the rest of the day, indeed right now, it will play in my mind, beautiful sticky music.

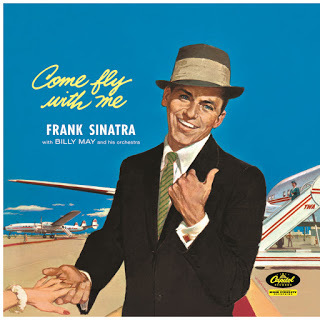

Unlike Keith Richards whose exposure to music was limited based on the two London radio stations and his mother's whims, music pervaded our home. Despite a contentious, on again, off again relationship between my parents, when the fighting ceased, there was music. My father had bought my mother a fine Magnavox console stereo, a beast in the guise of Mediterranean furniture, and leaning against it were Bobby Vinton's Greatest Hits and Johnny Mathis and Frank Sinatra's Come Fly With Me. Because I was such a great fan of Bobby Vinton when I was four, I got Saturday Night Is the Loneliest Night of the Week for Christmas in 1965 and an LP of rock nursery rhymes; the only one I remember is "Old King Cole." My older brother's music was in the form of 45s: "What's New, Pussycat?" and The Outsider's "Time Won't Let Me." Those of you who have read the snippets of my novel Jay and the Americans are aware of my love for The Beach Boys' "In My Room," the B side to "Be True to Your School." I was four years old, but the music was pervasive.

Unlike Keith Richards whose exposure to music was limited based on the two London radio stations and his mother's whims, music pervaded our home. Despite a contentious, on again, off again relationship between my parents, when the fighting ceased, there was music. My father had bought my mother a fine Magnavox console stereo, a beast in the guise of Mediterranean furniture, and leaning against it were Bobby Vinton's Greatest Hits and Johnny Mathis and Frank Sinatra's Come Fly With Me. Because I was such a great fan of Bobby Vinton when I was four, I got Saturday Night Is the Loneliest Night of the Week for Christmas in 1965 and an LP of rock nursery rhymes; the only one I remember is "Old King Cole." My older brother's music was in the form of 45s: "What's New, Pussycat?" and The Outsider's "Time Won't Let Me." Those of you who have read the snippets of my novel Jay and the Americans are aware of my love for The Beach Boys' "In My Room," the B side to "Be True to Your School." I was four years old, but the music was pervasive. I'd spend one day per week at my father's apartment, a cool 60s bachelor pad in Van Nuys. He listened to lounge music, the soft sounds of KOST FM, Burt Bacharach and Anne Murray, and he'd sing "Snowbird" in a bassy monotone. On our week together one summer he took me to Arizona, to Sedona, the Grand Canyon and Monument Valley. In the car, they were always playing The Doors' "Riders on the Storm." It's my Arizona song.

I'd spend one day per week at my father's apartment, a cool 60s bachelor pad in Van Nuys. He listened to lounge music, the soft sounds of KOST FM, Burt Bacharach and Anne Murray, and he'd sing "Snowbird" in a bassy monotone. On our week together one summer he took me to Arizona, to Sedona, the Grand Canyon and Monument Valley. In the car, they were always playing The Doors' "Riders on the Storm." It's my Arizona song.My mother was a singer and would sing along, beautifully, to everything. Her favorite, though, was Barbra Streisand's "People." She would sing in in the car when it came on the radio, or sing it to herself in the Thriftimart. I know all the lyrics.

For me, though, the most influential of songs, a song that taught me rhyme and speculation and emotion, was Richard Harris's "McArthur Park," the Jimmy Webb classic about God-knows-what. My father liked that one, as well. I'll never forget, some ten years later, his hearing the Donna Summer version. "What the hell is that," he said.

Published on March 18, 2018 20:34

Jay and the Americans - $1.99! - Starts at Midnight

Once again AM is running a Kindle promo starting March 19! For a limited time, you can read Jay and the Americans on your handheld device for just a $1.99. Just click on the Kindle sidebar.

Please don't forget to leave a review on Amazon! For those of you who want the real deal, Jay is available on Amazon world wide and on CreateSpace, and those of you who have Kindle Unlimited can still read the novel for free. Sales of Jay go directly back into the website and into the publication of my next novel Miles From Nowhere. More than sales, your reviews help AM grow. Please help to support the novel and your fave rock 'n' roll website!

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UK

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UKAmazon France - Amazon Russia

Published on March 18, 2018 11:46

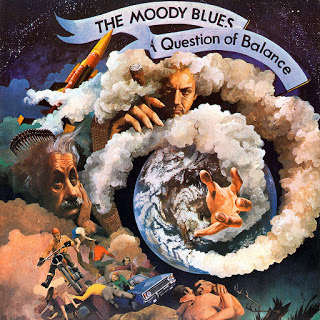

The Moody Blues and Phil Travers

I wasn't cool enough to be a part of the 60s, and not just because I wasn't old enough. I was there, born early in the decade, and, as you'll find when you finally read Jay and the Americans, my informative early years were shaped by 60's TV and rockets to the moon, by Space Food Sticks (you have to remember those) and The Monkees, but had I been in my teens, or in high school as the Summer of Love fell like fall leaves (and not the pretty yellow ones; the brown crumbly ones), I still wouldn't have been cool enough to immerse myself in this mesmerizing culture. I was cool enough in the 80s, for R.E.M. and New Order, but as it lay, I was The Monkees and not The Beatles, let alone The Moody Blues. And yet…

While my brother was cool enough to embrace Days of Future Passed, I didn't understand it. The songs were hidden amidst all that old people music (while my grandmother loved Nancy Sinatra's "These Boots Are Made For Walkin'," the music coming out of the Magnavox console stereo in our home was more likely Montovani and Ferrante and Teicher or 101 Strings' versions of Beethoven; and Days of Future Passed sounded more like that to me than the pop strains of Headquarters. And yet…

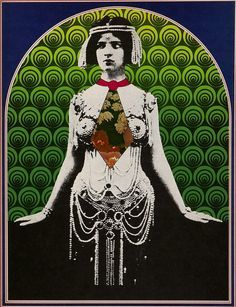

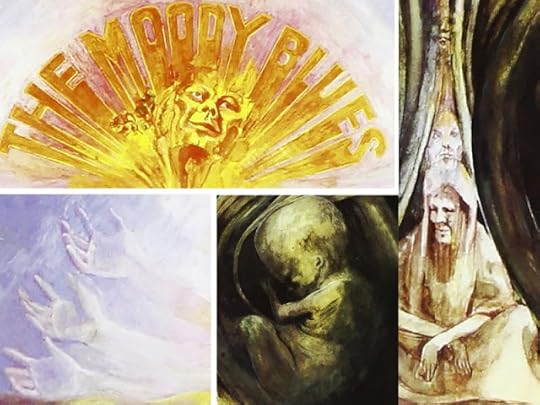

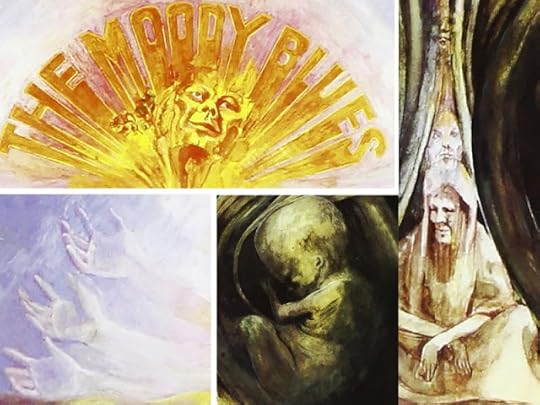

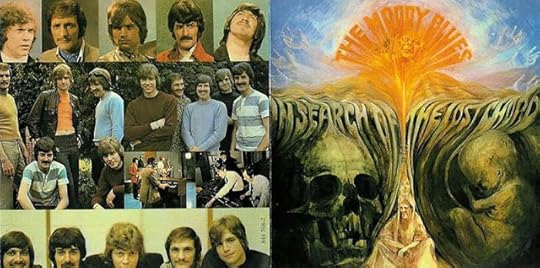

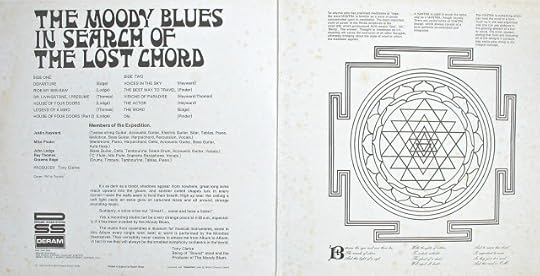

My brother got me In Seach of the Lost Chord for my birthday in 1968. I didn't want it, of course; he did, and he bought it in stereo so that I couldn't play it in my room and only on the Magnavox. (He got me Blood, Sweat and Tears too. Didn't want that either.) But I couldn't take my eyes off the cover, that hypnotizing painting by Phil Travers, who would work with the Moodys on six occasions. Like Hipgnosis' Storm Thorgerson and Pink Floyd, Travers was like another member of the band.

"I met the Moodys," he said, "in a London pub, and we worked out the details of the commission. They invited me down to the studio shortly after that first meeting to listen to the album. So I got an early taste for what they were doing. I liked it. And that's the way it always worked with them. I'd get to listen to the record, then discuss the themes and ideas behind it, before any art concepts were developed.

"The band wanted me to illustrate the concept of meditation. This was not something that I had much personal experience of, and so my early thoughts about the subject were, unfortunately, insubstantial. My first rough designs really reflected a lack of ideas. I began to panic a bit as time was running out, when that image I mentioned in the glass window, of a figure ascending, came back to me and everything then fell into place. I had days rather than weeks to complete the illustration, and submit it for approval. I used Gouache and some water colour to get the effect I was after."

Sometimes it’s the aesthetics of an LP that sparks our interest ( I can still visualize Nancy Sinatra in her go-go boots), and while we can argue over the validity of modern music (the tepid pop charts, the insufferable rap and its lack of musicality), one of the greatest losses that I've found since the advent of the CD and now MP3s and Spotify, is the disassociation of music with the visual. In the 60s, you wanted to peel that Velvet Underground banana or unzip Jagger's Levis, you had the Dark Side post cards on your bulletin board and you displayed Goodbye Yellow Brick Road like it was artwork, only to pick it up, open it and use the gatefold to roll a joint.

Sometimes it’s the aesthetics of an LP that sparks our interest ( I can still visualize Nancy Sinatra in her go-go boots), and while we can argue over the validity of modern music (the tepid pop charts, the insufferable rap and its lack of musicality), one of the greatest losses that I've found since the advent of the CD and now MP3s and Spotify, is the disassociation of music with the visual. In the 60s, you wanted to peel that Velvet Underground banana or unzip Jagger's Levis, you had the Dark Side post cards on your bulletin board and you displayed Goodbye Yellow Brick Road like it was artwork, only to pick it up, open it and use the gatefold to roll a joint.

Anyway, it was a birthday present, but it was its cover that brought my attention to the highly overlooked Moodys. In retrospect, they'd done the symphony thing and pulled it off with flying colors, but this follow-up was 100% Moody Blues. Of the 33(!) different instruments used on the LP, each was played by the band. They earned the nickname of "the world's smallest symphony orchestra."

The LP is a journey, from beginning to end, in search of the chord and ephemeral whatnot. There is a heavy Eastern Philosophical influence, especially on the Mike Pinder contributions ("Best Way to Travel," "Om") and the tracks flow into each other seamlessly, making it one contiguous work of early world music. In every song, the singer yearns for something that cannot be defined. Mike Pinder's searing mellotron and Ray Thomas's soaring flute are the definitive sounds of the album, while the lyrics are a fanciful journey like Coleridge or Shelley.

Of course, this is the album that yielded two of the Moody's most enduring concert pieces, "Ride My See-saw" and the psychedelic "Legend of a Mind." Another standout is "The Actor," a Justin Hayward penned ballad so haunting it matches "Nights in White Satin." Then there's the lovely "Voices in the Sky," and John Lodge's epic, expermental "House of Four Doors," which samples musical styles throughout history. When I was 7, that one was key for me. Lost Chord is loaded with beautiful, experimental music. Why this band is so often overlooked, especially as a part of the Prog Rock era, I'll never know.

An aside: Other LPs bought because of their covers: the velvet wrapped Odessa, by the BeeGees, Brain Salad Surgery, Coltrane's Blue Train, Sinatra's In the Wee Small hours of the morning, Unknown Pleasures, Houses of the Holy, Captain Fantastic. Just a smattering.

While my brother was cool enough to embrace Days of Future Passed, I didn't understand it. The songs were hidden amidst all that old people music (while my grandmother loved Nancy Sinatra's "These Boots Are Made For Walkin'," the music coming out of the Magnavox console stereo in our home was more likely Montovani and Ferrante and Teicher or 101 Strings' versions of Beethoven; and Days of Future Passed sounded more like that to me than the pop strains of Headquarters. And yet…

My brother got me In Seach of the Lost Chord for my birthday in 1968. I didn't want it, of course; he did, and he bought it in stereo so that I couldn't play it in my room and only on the Magnavox. (He got me Blood, Sweat and Tears too. Didn't want that either.) But I couldn't take my eyes off the cover, that hypnotizing painting by Phil Travers, who would work with the Moodys on six occasions. Like Hipgnosis' Storm Thorgerson and Pink Floyd, Travers was like another member of the band.

"I met the Moodys," he said, "in a London pub, and we worked out the details of the commission. They invited me down to the studio shortly after that first meeting to listen to the album. So I got an early taste for what they were doing. I liked it. And that's the way it always worked with them. I'd get to listen to the record, then discuss the themes and ideas behind it, before any art concepts were developed.

"The band wanted me to illustrate the concept of meditation. This was not something that I had much personal experience of, and so my early thoughts about the subject were, unfortunately, insubstantial. My first rough designs really reflected a lack of ideas. I began to panic a bit as time was running out, when that image I mentioned in the glass window, of a figure ascending, came back to me and everything then fell into place. I had days rather than weeks to complete the illustration, and submit it for approval. I used Gouache and some water colour to get the effect I was after."

Sometimes it’s the aesthetics of an LP that sparks our interest ( I can still visualize Nancy Sinatra in her go-go boots), and while we can argue over the validity of modern music (the tepid pop charts, the insufferable rap and its lack of musicality), one of the greatest losses that I've found since the advent of the CD and now MP3s and Spotify, is the disassociation of music with the visual. In the 60s, you wanted to peel that Velvet Underground banana or unzip Jagger's Levis, you had the Dark Side post cards on your bulletin board and you displayed Goodbye Yellow Brick Road like it was artwork, only to pick it up, open it and use the gatefold to roll a joint.

Sometimes it’s the aesthetics of an LP that sparks our interest ( I can still visualize Nancy Sinatra in her go-go boots), and while we can argue over the validity of modern music (the tepid pop charts, the insufferable rap and its lack of musicality), one of the greatest losses that I've found since the advent of the CD and now MP3s and Spotify, is the disassociation of music with the visual. In the 60s, you wanted to peel that Velvet Underground banana or unzip Jagger's Levis, you had the Dark Side post cards on your bulletin board and you displayed Goodbye Yellow Brick Road like it was artwork, only to pick it up, open it and use the gatefold to roll a joint.Anyway, it was a birthday present, but it was its cover that brought my attention to the highly overlooked Moodys. In retrospect, they'd done the symphony thing and pulled it off with flying colors, but this follow-up was 100% Moody Blues. Of the 33(!) different instruments used on the LP, each was played by the band. They earned the nickname of "the world's smallest symphony orchestra."

The LP is a journey, from beginning to end, in search of the chord and ephemeral whatnot. There is a heavy Eastern Philosophical influence, especially on the Mike Pinder contributions ("Best Way to Travel," "Om") and the tracks flow into each other seamlessly, making it one contiguous work of early world music. In every song, the singer yearns for something that cannot be defined. Mike Pinder's searing mellotron and Ray Thomas's soaring flute are the definitive sounds of the album, while the lyrics are a fanciful journey like Coleridge or Shelley.

Of course, this is the album that yielded two of the Moody's most enduring concert pieces, "Ride My See-saw" and the psychedelic "Legend of a Mind." Another standout is "The Actor," a Justin Hayward penned ballad so haunting it matches "Nights in White Satin." Then there's the lovely "Voices in the Sky," and John Lodge's epic, expermental "House of Four Doors," which samples musical styles throughout history. When I was 7, that one was key for me. Lost Chord is loaded with beautiful, experimental music. Why this band is so often overlooked, especially as a part of the Prog Rock era, I'll never know.

An aside: Other LPs bought because of their covers: the velvet wrapped Odessa, by the BeeGees, Brain Salad Surgery, Coltrane's Blue Train, Sinatra's In the Wee Small hours of the morning, Unknown Pleasures, Houses of the Holy, Captain Fantastic. Just a smattering.

Published on March 18, 2018 05:10

The Magnificent Moodies

You flip through the vinyl at your fave record shop and come across The Zombies. You know the songs, "Tell Her No," "She's Not There" and "Time of the Season," among the best singles the 60s have to offer, but you've never heard the misspelled LP called Oddessey and Oracle. Turns out to be one of the stellar albums of 1968, and you pick it up for a couple bucks because no one's ever heard of it. Like S.F. Sorrow, another dismissed tour de force, you figure it's a score and now you're privy to what others are not. Someday you'll happen upon Blue Cheer's Vincebus Eruptus or you'll find Badger's debut, a live LP, and buy it simply because of the incredible Roger Dean cover. So, it's dumb luck, but how can a band whose first seven LPs (discounting the fledgling debut), be so readily dismissed? Of course I'm referring to The Moody Blues. No doubt, die hard fans still flock to Red Rocks, but when we read of the greatest LPs of all time, the Moodys are mostly forgotten. Our little website can't fix that, but we can acknowledge a ten year stint that embraced pop and psychedelia like a boss. What follows may seem but a boring list. It's my justification for the elevation of The Moodys as one of the greatest bands in the rock canon, purveyors of the concept and the catalyst of art rock.

You flip through the vinyl at your fave record shop and come across The Zombies. You know the songs, "Tell Her No," "She's Not There" and "Time of the Season," among the best singles the 60s have to offer, but you've never heard the misspelled LP called Oddessey and Oracle. Turns out to be one of the stellar albums of 1968, and you pick it up for a couple bucks because no one's ever heard of it. Like S.F. Sorrow, another dismissed tour de force, you figure it's a score and now you're privy to what others are not. Someday you'll happen upon Blue Cheer's Vincebus Eruptus or you'll find Badger's debut, a live LP, and buy it simply because of the incredible Roger Dean cover. So, it's dumb luck, but how can a band whose first seven LPs (discounting the fledgling debut), be so readily dismissed? Of course I'm referring to The Moody Blues. No doubt, die hard fans still flock to Red Rocks, but when we read of the greatest LPs of all time, the Moodys are mostly forgotten. Our little website can't fix that, but we can acknowledge a ten year stint that embraced pop and psychedelia like a boss. What follows may seem but a boring list. It's my justification for the elevation of The Moodys as one of the greatest bands in the rock canon, purveyors of the concept and the catalyst of art rock.May 4, 1964: The Moody Blues, consisting of Denny Laine (lead vocals, guitar), who would go on to play guitar for Wings, Ray Thomas (vocals, tambourine, flute), Mike Pinder (vocals, mellotron, piano), Clint Warwick (vocals, bass guitar), and Graeme Edge (vocals, drums), form in Birmingham.

Spring, 1964: The single "Steal Your Heart Away/Lose Your Money(But Don't Lose Your Mind)" is released to commercial failure in the UK. The Moody Blues appeared on the UK TV series Ready, Steady, Go to promote the B side.

October, 1964: The Moody Blues record their debut The Magnificent Moodies at Decca Studios in West Hampstead, London.

October 30, 1964: The Moody Blues perform at the Crawdaddy Club in London, England.

November, 1964: The single "Go Now," is released to critical and commercial success. The single peaked at No. 1 on the UK Singles Chart, and at No. 10 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the US.

July 22, 1965: The Magnificent Moodies, is released to regional, critical and commercial success. The album peaked at No. 5 in the UK, but failed to chart in the US.

October, 1966: Rod Clark departs from the Moody Blues. Denny Laine departs as well.

November, 1966: After a brief hiatus, The Moody Blues re-form, with John Lodge replacing Rod Clark on Bass Guitar and Justin Hayward replacing Denny Laine on lead vocals and guitar. Here then is where it gets good. For the next year, the Moodys face a lack of success that would have split the average band, but…October 8, 1967: The Moody Blues go into Decca Studios in West Hampstead, London, England, to record their second album, the concept album Days of Future Passed. Initially conceived as a merging of classical music and rock, the LP was meant as a stylized version of Antonín Dvořák's Symphony No. 9, also known as the New World Symphony. Of their own volition and despite Decca's new label, Deram, dismissing the idea,the concept LP was born (many will point to Pet Sounds and In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning, but that's splitting hairs) The concept of this album, a day in the life of everyman, features the London Festival Orchestra.

November 11, 1967: Days of Future Passed, featuring the songs "Tuesday Afternoon," and "Nights in White Satin," is released to critical and commercial success. The album peaked at No. 27 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 3 on the Billboard 200 in the US. "Tuesday Afternoon" peaked at No. 24 on the Billboard Hot 100, while failing to chart in the UK, and "Nights in White Satin" rose to No. 9 on the UK Singles Chart and No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the US, respectively.

January, 1968: The Moody Blues record In Search of the Lost Chord at Decca Studios in West Hampstead, London. The concepts of the LP are quest and discovery.

July 26, 1968: In Search of the Lost Chord, featuring the single "Ride My See-Saw," and cult fave "Legend of a Mind," is released to critical and commercial success.

November 8, 1968: The Moody Blues perform at the Electric Factory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

November 24, 1968: The Moody Blues perform at the Fillmore West in San Francisco, California.

January 12, 1969: The band head back to Decca Studios to record their fourth album, the concept LP On the Threshold of a Dream. The concept, duh, is dreams.

April 25, 1969: On the Threshold of a Dream peaks at No. 5 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 23 on the Billboard 200 in the US.

May, 1969: Just three months later, The Moody Blues record their fifth album, yes, indeed, a concept LP, To Our Children's Children's Children.

October, 1969: The single "Watching and Waiting" is released to commercial failure, selling about ten copies (half of which were purchased by the Moody Blues themselves).

November 21, 1969: To Our Children’s Children’s Children is released to critical and commercial success. The album peaked at No. 2 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 14 in America.

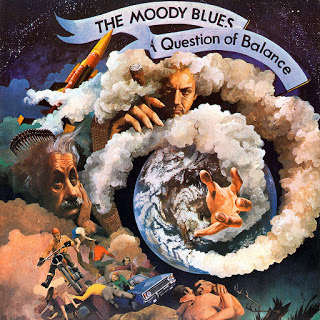

January 17, 1970: The band record their sixth album, A Question of Balance.

April, 1970: The single "Question" is released to critical and commercial success. The single peaked at No. 2 in the UK and No. 21 on the Billboard Hot 100.

August 7, 1970: A Question of Balance is released to critical and commercial success. The album is their most successful, reaching No. 1 in the UK and No. 3 in the US.

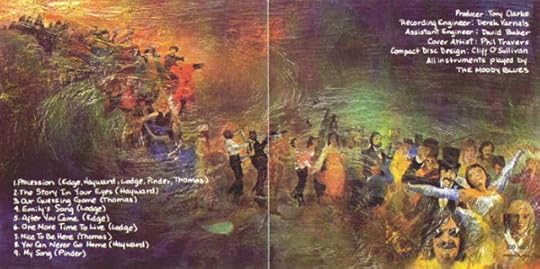

November, 1970: The Moodys head to Wessex Studios in London to record their seventh album, Every Good Boy Deserves Favour.

July 23, 1971: Every Good Boy Deserves Favour, featuring the songs "Procession" and "The Story in Your Eyes,"is released to critical and commercial success. The album rose to No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 2 on the Billboard 200 in the US. "The Story in Your Eyes" reached No. 23 on the Billboard Hot 100.

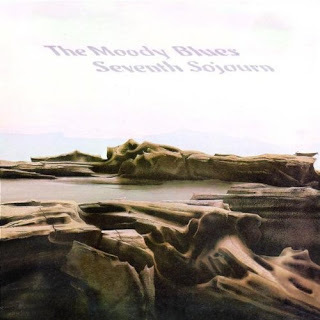

January, 1972: The Moody Blues go into Decca, Tollington Park Studios, London to record their eighth album, Seventh Sojurn.

April, 1972: The single "Isn’t Life Strange" is released to critical and commercial success.

November 17, 1972: Seventh Sojurn is released to critical and commercial success. The album makes No. 5 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 1 on the Billboard charts.

Published on March 18, 2018 05:10

March 17, 2018

In Search of the Lost Chord - The Moody Blues - AM8

After Days of Future Passed became a critical (if reluctantly financial) success, the Moody Blues were faced with the daunting task of following up the ground-breaking work. They did so in 1968 with In Search of the Lost Chord, which saw them further develop their mind-expanding sound and immerse themselves in psychedelic culture. This is probably the Moodys' most experimental and unusual album, if undeniably dated.

After Days of Future Passed became a critical (if reluctantly financial) success, the Moody Blues were faced with the daunting task of following up the ground-breaking work. They did so in 1968 with In Search of the Lost Chord, which saw them further develop their mind-expanding sound and immerse themselves in psychedelic culture. This is probably the Moodys' most experimental and unusual album, if undeniably dated.In Search of the Lost Chord is a concept album of quest and discovery as its expansive theme. While done with broad strokes, the LP encompassed space exploration, time travel, altered states, life's psychological journeys and self-actualization.

The Moodys created out of 33 instruments, their own mini-orchestra, without the aid a session-men or orchestra. Once again, every member of the band took a share of songwriting duties that include two spoken word pieces by Graeme Edge. The first of which, "Departure," melds nicely into the album's first single, "Ride My See-Saw" from John Lodge, a rocker with fine guitar from Justin Hayward. Lodge also provides "House of Four Doors Parts 1 and 2," a haunting pair of tracks with Part 1 featuring sound FX of each door creaking open. Mike Pinder contributes to the psychedelic mood of the album with the trippy "Best Way to Travel" and the sitar-drenched "OM"(which turns out to be the eponymous Lost Chord), while Justin Hayward is responsible for another beautiful pair of ballads in the shape of the "Voices in the Sky" and the dramatic "The Actor." The hippy vibe that suffuses the record is also in evidence on "Visions of Paradise," a lovely Hayward/Ray Thomas collaboration with some atmospheric flute work.

The most memorable song on the album, however, is Ray Thomas' epic "Legend of a Mind," about the LSD guru Timothy Leary. Once again featuring some excellent flute work from Thomas, this complex song is performed by the band with utter conviction and builds to a pulsating climax. Thomas died this past January.

To truly understand these early days of progressive rock, put yourself in 1968 listening to this album for the first time. The Moody Blues surpassed even the Beatles with their exquisitely complex orchestrations, using instruments that often were (and are) played only in obscure classical presentations.

Sessions for the album commenced in January 1968 with the recording of Thomas's "Legend of a Mind." Whereas the London Festival Orchestra had supplemented the group on Days of Future Passed, the Moodys played all instruments themselves. Indian instruments such as the sitar (played by guitarist Justin Hayward), the tambura (played by keyboardist Mike Pinder) and the tabla (played by drummer and percussionist Graeme Edge) made appearances on several tracks (notably "Departure", "Visions of Paradise" and "Om"). Other unconventional instruments were used, notably the oboe (played by percussionist/flute player Ray Thomas) and the cello (played by bassist John Lodge, who tuned it as a bass guitar). The mellotron, played by Pinder, produced the various string and horn embellishments.

Having already experimented with spoken word interludes on "Morning Glory" and "Late Lament" on Days of Future Passed, the group repeated the bookend idea with the Graeme Edge-penned "Departure" and "The Word." The latter was recited by Pinder, while "Departure," which escalates from mumbling to hysterical laughter, is a rare studio example of Edge reciting his own words.

In Search of the Lost Chord was released on 26 July 1968. It peaked at number 5 in the UK and reached number 23 on the US album charts.

Published on March 17, 2018 12:01

Jay and the Americans - $1.99!

Once again AM is running a Kindle promo starting March 19! For a limited time, you can read Jay and the Americans on your handheld device for just a $1.99. Just click on the Kindle sidebar.

Please don't forget to leave a review on Amazon! For those of you who want the real deal, Jay is available on Amazon world wide and on CreateSpace, and those of you who have Kindle Unlimited can still read the novel for free. Sales of Jay go directly back into the website and into the publication of my next novel Miles From Nowhere. More than sales, your reviews help AM grow. Please help to support the novel and your fave rock 'n' roll website!

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UK

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UKAmazon France - Amazon Russia

Published on March 17, 2018 07:46