R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 55

November 5, 2018

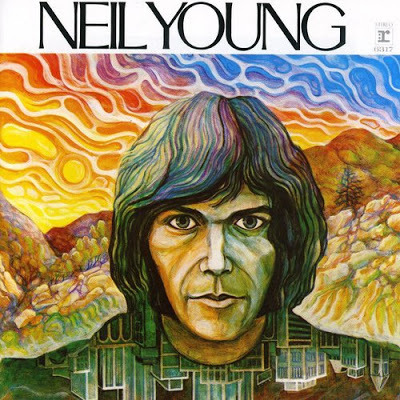

Neil Young Debut LP

By 1968, Neil Young already had a stellar musical history behind him. Young released his self-titled solo debut on Nov. 12, 1968, his 23rd birthday. The LP featured many of Young's trademarks, including biting guitar work and his signature vocal style. But within that context, he also used a variety of colors to paint one of the most distinctive and eclectic records in his long, storied career.

By 1968, Neil Young already had a stellar musical history behind him. Young released his self-titled solo debut on Nov. 12, 1968, his 23rd birthday. The LP featured many of Young's trademarks, including biting guitar work and his signature vocal style. But within that context, he also used a variety of colors to paint one of the most distinctive and eclectic records in his long, storied career.It all kicks off with "The Emperor of Wyoming," a country-style instrumental that launches into "The Loner," which remains one of Young's greatest songs and one of the earliest showcases for his signature sound. The beautiful ballad "If I Could Have Her Tonight" follows, taking cues from Buffalo Springfield. Meanwhile, the underrated "I've Been Waiting for You" features one of Young's greatest arrangements, especially the instrumental centerpieces – like the fuzz guitar. It's one of the album's most potent, and unheralded, tracks.

The LP ends with "The Last Trip to Tulsa," a psychedelic narrative that revolves around Young's voice and acoustic guitar. The song builds as its story unfolds, making it one of his most engaging numbers and a fitting conclusion to his solo debut.

The album was released with no name or title on the cover, just a painting of Young. In fast-moving '60s fashion, the LP was recorded in the summer of '68 and released in November to a muted response, apart, that is, from Young himself. At some point after his work on the album was completed but before it was pressed, Reprise ran the mixes through the Haeco-CSG process, altering the sound from what Young was expecting. CSG was a short-lived work-around utilized after the demise of mono records. Basically, it phase-shifted the channel info so that when stereo records were played back over a mono radio signal they emulated the mono mix. A side-effect of the process was a softening and muddying of the sonic properties of the recording evident on the original pressings of Neil Young. When Young heard the result, he decided the Haeco-CSG had to go. In the process he heavily remixed three tracks additional creating an instant rarity for collectors. At the same time, the cover art was changed to include his name. Adding to the discographic confusion, the original jackets lasted longer than the first run of LPs, so the remixed LPs often showed up in the no-name covers.

[Even more fun for collectors is that in the early '70s, a pressing plant grabbed the wrong stamper for side two, and the CSG mix made a brief, accidental reappearance. To a certain extent this mistake makes sense, as when the remixed sides were created, only side one notated it as such in the deadwax (the area without music around the label) with a RE-1. After many years of hunting for the original mix, I've never seen a side two that says RE-1, indicating the remix. (Confused yet?) So, collectors note, the original pressing and the initial run of the remixed LPs both use the two-tone orange and tan Reprise label. To identify an original mix, just check the deadwax on side one: the etching in the deadwax will not include RE-1 anywhere. Finding the mispressing from the '70s of side two is trickier, since that side apparently never indicated RE-1 and were issued with a Reprise label (not WB as later pressings were). After that, look at the number/letter code at the end of the matrix info in the deadwax. If it has a variation of -1 and a letter it should be the original mix; the remixes end with -2.]

Despite all the collector fun, this is Neil Young's moving and breathtaking debut. Every time I listen to it, I become more and more certain that it's among Neil Young's finest, if a far cry from LPs like Harvest and After the Gold Rush (kind of like comparing the Grateful Dead’s Debut with any of their other studio LPs). It's worth repearing, the tracks "The Loner", "If I Could Have Her Tonight", and "The Old Laughing Lady" are all stellar, but the best tracks are the deeply moving "I've Been Waiting For You" and the psych epic "The Last Trip to Tulsa."

Published on November 05, 2018 05:12

November 4, 2018

1968

While 1968 is the year we lost Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, and the average age of a young man in Vietnam was 19, it was a year of phenomenal music that rivaled 1967 and 1972 and [pick a year]. A week after RFK was shot, my dog, Taffy, ran up the steps in our apartment complex skidded on the smooth deck and slid under the upstairs railing. I ran screaming into the house imagining the worst. The song on the radio was "Hurdy Gurdy Man." Taffy licked my hand and my brother ran into the apartment. He said, "I've never seen such a thing."

While 1968 is the year we lost Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, and the average age of a young man in Vietnam was 19, it was a year of phenomenal music that rivaled 1967 and 1972 and [pick a year]. A week after RFK was shot, my dog, Taffy, ran up the steps in our apartment complex skidded on the smooth deck and slid under the upstairs railing. I ran screaming into the house imagining the worst. The song on the radio was "Hurdy Gurdy Man." Taffy licked my hand and my brother ran into the apartment. He said, "I've never seen such a thing."While psychedelia was still in full bloom with Donovan and "Pictures of Matchstick Men," there was a back-to-the-basics reaction to it in 1968: Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding (released in the final days of 1967, his first single being waylaid by a motorcycle accident in '66), the Byrds' country-tinged Sweetheart of the Rodeo and the debut album by the band called The Band reflected a way to escape the craziness and live a simpler life. Three refugees from other bands, simply calling themselves Crosby, Stills and Nash, got together to explore harmony and, along with emerging singers like Joni Mitchell and James Taylor, launch the singer-songwriter genre that would flower in the 70s.

Meanwhile, the earliest stirrings of hard rock and progressive rock marked a desire among musicians to push beyond psychedelia into new territories: Bands formed in 1968 included Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, King Crimson, Rush, Yes and the New Yardbirds, who would soon become Led Zeppelin.

While all this was happening, AM radio still played the hits. Some of them were admittedly lightweight: the term bubblegum music was coined to describe purposely frothy tunes like "Yummy, Yummy, Yummy" and "Sugar, Sugar" that couldn't be any further from the turbulence that ruled the news. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Steppenwolf clamored up the charts with "Born to Be Wild" and The Rolling Stones released the genre-bending "Jumpin' Jack Flash."

Motown was still turning out gold and platinum seemingly weekly, with hit after hit from Diana Ross and the Supremes, the Temptations, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder and others. James Brown and Sly and the Family Stone pointed the way toward funk.

And of course, we still had the Beatles, whose self-titled double-LP let us know that they were drifting apart even as they continued to collaborate on some of the most diverse and brilliant music in their canon.

It's that diversity that is most impressive about 1968's rock, pop and soul. But it's also the tenacious quality of the music that amazes — so much of what we listened to 50 years ago sounds fresh and innovative. 50 years ago in November, we were privy to The Beatles and if that wasn't enough we got "Lady Madonna" to boot and the biggest selling single of the year in "Hey Jude." The Monkees' Head was released and the debut Neil Young LP. It was the year of "On the Road Again" from Canned Heat and Hendrix' "All Along the Watchtower." It was "Magic Bus" and "MacArthur Park" and "Tiptoe Through the Tulips;" we were that diverse, and all still on AM radio.

Published on November 04, 2018 03:04

November 3, 2018

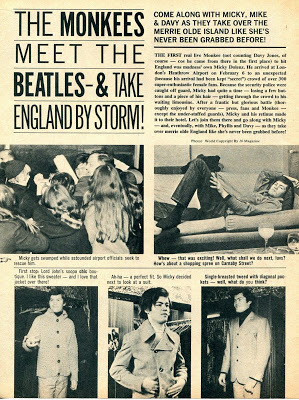

The Pre-Fab Four - The Beatles on The Monkees

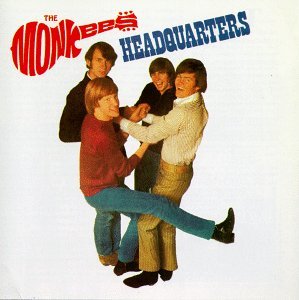

The relationship between the Beatles and the Monkees was casual, and at times, close. The American ghetto of rock "friends" centered on Laurel Canyon, and the Monkees, particularly Peter Tork and Mickey Dolenz, were often the enclave's go-to party guys. Musical purists and Beatles' devotees are quick to point out the boy-band qualities of the primates, but the reality is, as particularly demonstrated in the self-produced Headquarters, the Monkees weren't second-rate Beatles copycats but talented musicians and songwriters. Indeed, Mike Nesmith and Mickey Dolenz were both a presence at Abbey Road during the recording of Sgt. Pepper. It was at this time that Dolenz was encouraged by Lennon to write "Randy Scouse Git" and out of that, Mickey's first recorded song became one Headquarters' highlights and a killer track in general. In it appear the lyrics, "The four kings of EMI sitting stately on the floor," a direct reference, of course, to the Fab Four. (Imagine those kings sitting there Indian-style on the checkered tile floor at EMI.) In Britain, the song, under the assumed name "Alternate Title" to appease the risqué slant, went to No. 2. It was at those sessions ("A Day in the Life" - February 10, 1967) that Nesmith, the most talented of the four, asked Lennon, "Do you think we're a cheap imitation of the Beatles; your movies and your records?" Lennon replied, "I think you’re the greatest comic talent since the Marx Brothers;" maybe not what Nesmith was looking for, but pretty high praise.

The relationship between the Beatles and the Monkees was casual, and at times, close. The American ghetto of rock "friends" centered on Laurel Canyon, and the Monkees, particularly Peter Tork and Mickey Dolenz, were often the enclave's go-to party guys. Musical purists and Beatles' devotees are quick to point out the boy-band qualities of the primates, but the reality is, as particularly demonstrated in the self-produced Headquarters, the Monkees weren't second-rate Beatles copycats but talented musicians and songwriters. Indeed, Mike Nesmith and Mickey Dolenz were both a presence at Abbey Road during the recording of Sgt. Pepper. It was at this time that Dolenz was encouraged by Lennon to write "Randy Scouse Git" and out of that, Mickey's first recorded song became one Headquarters' highlights and a killer track in general. In it appear the lyrics, "The four kings of EMI sitting stately on the floor," a direct reference, of course, to the Fab Four. (Imagine those kings sitting there Indian-style on the checkered tile floor at EMI.) In Britain, the song, under the assumed name "Alternate Title" to appease the risqué slant, went to No. 2. It was at those sessions ("A Day in the Life" - February 10, 1967) that Nesmith, the most talented of the four, asked Lennon, "Do you think we're a cheap imitation of the Beatles; your movies and your records?" Lennon replied, "I think you’re the greatest comic talent since the Marx Brothers;" maybe not what Nesmith was looking for, but pretty high praise.

Of the Monks, George Harrison said, "It's obvious what's happening; there's talent there… when they get it all sorted out, they might turn out to be the best. "Harrison even invited Tork to play banjo on Wonderwall. "The Monkees are still finding out who they are, and they seem to be improving as performers each time I see them." Paul said, "I'm sure that the Monkees are going to live up to a lot of things many people didn't expect...I like their music a lot...and you know, their personalities. I watch their tv show and it is good." Lennon rounded it out with,"Monkees? They've got their own scene, and I won't send them down for it. You try a weekly television show and see if you can manage one half as good!"

Those encounters in L.A. and at Abbey Road, though, were not the first encounters that Davy Jones had with the Fab Four. At the age of 18, Davy performed a solo on the same famous episode of The Ed Sullivan Show in which The Beatles made their monstrously successful U.S. live television debut (on February 9, 1964). Jones was appearing on Broadway in Oliver! in the role as the Artful Dodger, for which he received a Tony nomination. Interestingly, no one, of course, paid any attention to Davy that night, but I'd assume there was a great deal of satisfaction on the Monkees' part when, in rock's greatest year, they outsold The Beatles.

Those encounters in L.A. and at Abbey Road, though, were not the first encounters that Davy Jones had with the Fab Four. At the age of 18, Davy performed a solo on the same famous episode of The Ed Sullivan Show in which The Beatles made their monstrously successful U.S. live television debut (on February 9, 1964). Jones was appearing on Broadway in Oliver! in the role as the Artful Dodger, for which he received a Tony nomination. Interestingly, no one, of course, paid any attention to Davy that night, but I'd assume there was a great deal of satisfaction on the Monkees' part when, in rock's greatest year, they outsold The Beatles. A brief rundown: The Stones released Between The Buttons (one of their finest moments), which peaked at No. 2, briefly; Flowers, an American compilation with a plethora of hits that peaked at No. 3, and then Their Satanic Majesties Request, which arrived late in the year (December 8), peaked at No. 2, then faded quickly. They scored just one No. 1 US single that year with "Ruby Tuesday," and that for merely a week.

A brief rundown: The Stones released Between The Buttons (one of their finest moments), which peaked at No. 2, briefly; Flowers, an American compilation with a plethora of hits that peaked at No. 3, and then Their Satanic Majesties Request, which arrived late in the year (December 8), peaked at No. 2, then faded quickly. They scored just one No. 1 US single that year with "Ruby Tuesday," and that for merely a week.The Beatles issued two US albums: Sgt. Pepper was #1 for 15 weeks (throughout the Summer of Love), while Magical Mystery Tour, released December '67, had an 8-week chart-topping run in early 1968. The Beatles' U.S. single output – "Penny Lane"/"Strawberry Fields Forever" – "All You Need Is Love"/"Baby You’re A Rich Man" and "Hello Goodbye"/"I Am The Walrus" EACH enjoyed a week at No. 1 that year.

In comparison, though, The Monkees' juggernaut was unstoppable. Though two of the year's three singles stopped short of No. 1 ("A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You" and "Pleasant Valley Sunday" peaked at Nos. 2 and 3 respectively), 1966's "I'm A Believer" had a seven-week run at the top, in the early part of '67, and became the year's biggest selling single, while "Daydream Believer" had a four week run, for a combined ten weeks atop the US charts for 1967. Ten weeks; not three (Beatles), not one (Stones), and Monkee LPs faired even better: The Monkees, More of The Monkees, Headquarters and Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn and Jones, Ltd combined held the top U.S. slot for 29 weeks in 1967. Compare that to the Beatles' 15 for Pepper. (In fact, The Monkees STILL hold the record for having four albums atop the Billboard LP chart in a single year – not even the Beatles beat them.)

And, of course, when push comes to shove, Lennon did say, "Everybody's got something to hide, except for me and my Monkee."

Published on November 03, 2018 09:11

The Monkees on The Beatles

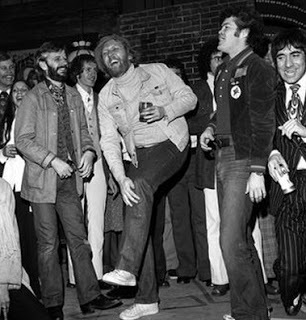

Ringo, Nilsson, Mickey Dolenz and Keith Moon1967 was seemingly everyone's year, from the Association to the Zombies, but it was the Beatles and the Monkees that shared the top spots, with Sgt. Pepper easing out Headquarters. So what was the relationship between the two bands?

Ringo, Nilsson, Mickey Dolenz and Keith Moon1967 was seemingly everyone's year, from the Association to the Zombies, but it was the Beatles and the Monkees that shared the top spots, with Sgt. Pepper easing out Headquarters. So what was the relationship between the two bands?Peter: Micky and I are meeting the Beatles at a London club called the Speakeasy. And in come George and John singing to the tune of "Hare Krishna," "Micky Dolenz, Micky Dolenz, Dolenz, Dolenz, Micky, Micky." And Paul is with Jane Asher, and the other guys didn't bring anybody, and I had just done some STP which was an LSD-type psychedelic drug. I mentioned it to John and he said, "We heard that's no good. Mama Cass told us not to take it." But he said, "Okay." So I went back to the hotel and I got some. Popped one down his throat. I guess he was all right because he seemed to survive. I don't think I'm responsible for "Strawberry Fields" though.

Davy: I was performing a song from Oliver! on The Ed Sullivan Show when the Beatles made their American debut. I saw this amazing reaction and I thought, "I want a bit of this - this is good." I remember getting into the lift with Ringo Starr. I was always a cheeky little guy. He had a cold at the time and I remember saying, "Let me blow your nose for you, I'm closer than you are." Ringo said, "I know."

Mike: I was a Beatles fan. When I had my newfound fame as a television star, I thought I'd figure out if I could broker this into a meeting with some people I wanted to meet. One of them was John Lennon. I flew to London and sent him a telegram that said, "I'm at the such and such hotel and I would very much like to meet you." I signed it, "God is Love, Mike Nesmith." Now, "God is Love" was an utterly radical thing to say in the 60s, especially on a telegram. He called me at the hotel. He said, "I'll send a car for you. Come stay with me instead." That was the beginning of the friendship. We maintained it from a distance. Every time I went to London I would look him up, and he would call me when he came here.

Mike: I was a Beatles fan. When I had my newfound fame as a television star, I thought I'd figure out if I could broker this into a meeting with some people I wanted to meet. One of them was John Lennon. I flew to London and sent him a telegram that said, "I'm at the such and such hotel and I would very much like to meet you." I signed it, "God is Love, Mike Nesmith." Now, "God is Love" was an utterly radical thing to say in the 60s, especially on a telegram. He called me at the hotel. He said, "I'll send a car for you. Come stay with me instead." That was the beginning of the friendship. We maintained it from a distance. Every time I went to London I would look him up, and he would call me when he came here.Mike on "A Day in the Life" recording session: I was staying with John Lennon during the recording of the Sgt. Pepper album. He would come home and play the acetates from the day's sessions. "What do you think of that sound? Do you think there's too much bass on there?" And of course, I just didn't have any way to talk to him because he was just rearranging my musical realities at the time. I said, "This is just miraculous. This is some of the most innovative and creative and interesting stuff I've ever heard." And he showed me a picture of the album cover. So when he said, "Do you want to come down and hang?" I was there. The only thing I can really remember about the sessions, however, was Marianne Faithfull--whoa. I thought, "This is the rock and roll mama of all time." And I was unabashedly just stricken. She was with Jagger. When she wandered into the room I thought, "Oh, this is what the fuss is all about." She was some stone fox, I'll tell you."

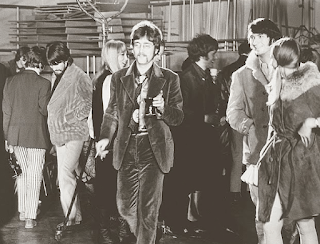

Micky: "I was invited to a recording session. So I dressed up in all my caftans and beads and glasses with sparkly stuff, and I was sure I was gonna go to this unbelievable-pop-historical-Andy Warholesque-Fellini event with the Beatles and groupies and God knows what. I walk into EMI Recording Studios on Abbey Road and it's like a doctor’s office-- bright fluorescent lights. The guys are sitting there in shirts and t-shirts and slacks with their instruments, and George Martin is in the booth. "Right, once again, and three, four...." I was so stoned and stunned. I was just walking around, "Ohhhh." "Right, okay, once again...Right, cut it, time for tea lads." And the guy comes in with a big tray of tea and sits it on the card table and they all sit around and we had tea for 20 minutes. And I'm blown away. I couldn't believe it. And then they went right back to work; they were working lads from the north. They just did this 16 hours a day for years. That's where all that stuff came from. So I floated out about an hour later."

Micky: "I was invited to a recording session. So I dressed up in all my caftans and beads and glasses with sparkly stuff, and I was sure I was gonna go to this unbelievable-pop-historical-Andy Warholesque-Fellini event with the Beatles and groupies and God knows what. I walk into EMI Recording Studios on Abbey Road and it's like a doctor’s office-- bright fluorescent lights. The guys are sitting there in shirts and t-shirts and slacks with their instruments, and George Martin is in the booth. "Right, once again, and three, four...." I was so stoned and stunned. I was just walking around, "Ohhhh." "Right, okay, once again...Right, cut it, time for tea lads." And the guy comes in with a big tray of tea and sits it on the card table and they all sit around and we had tea for 20 minutes. And I'm blown away. I couldn't believe it. And then they went right back to work; they were working lads from the north. They just did this 16 hours a day for years. That's where all that stuff came from. So I floated out about an hour later."

Published on November 03, 2018 05:07

November 2, 2018

The Naked Party House

Poet, TS Eliot popularized the "objective correlative;" the idea that in order for a work to gain value moving forward, emotional content must be non-specific. Here, as an example, is a scene from a cheesy melodrama: Fade in - a cemetery filled with weather-worn headstones, droplets of rain cascading down stone angel faces; a small congregation of people dressed in black holding umbrellas. An old woman raises a veil, takes off a ring, places it on a coffin; faint sobbing is audible. Slowly the clouds break and a shaft of sunlight shines on a single blooming yellow marigold. Credits. The viewer's emotional response, which starts off somber, ends with renewed hope, though the filmmaker provides nothing tangible to conjure this analysis. Sunlight induces joy as readily as it causes skin cancer; a marigold by itself is pretty, but one doesn’t necessarily sense optimism in its presence. The emotional response originates, not in a word, image, action or reaction, but in the combination of all; a sort of emotional algebra. The objective correlative is the formula for creating a specific emotional reaction merely by the juxtaposed presence of common words, objects, or items. The sum is greater than the parts.

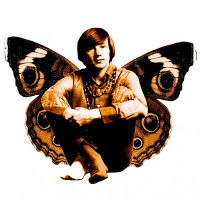

Poet, TS Eliot popularized the "objective correlative;" the idea that in order for a work to gain value moving forward, emotional content must be non-specific. Here, as an example, is a scene from a cheesy melodrama: Fade in - a cemetery filled with weather-worn headstones, droplets of rain cascading down stone angel faces; a small congregation of people dressed in black holding umbrellas. An old woman raises a veil, takes off a ring, places it on a coffin; faint sobbing is audible. Slowly the clouds break and a shaft of sunlight shines on a single blooming yellow marigold. Credits. The viewer's emotional response, which starts off somber, ends with renewed hope, though the filmmaker provides nothing tangible to conjure this analysis. Sunlight induces joy as readily as it causes skin cancer; a marigold by itself is pretty, but one doesn’t necessarily sense optimism in its presence. The emotional response originates, not in a word, image, action or reaction, but in the combination of all; a sort of emotional algebra. The objective correlative is the formula for creating a specific emotional reaction merely by the juxtaposed presence of common words, objects, or items. The sum is greater than the parts.  For our purposes in analyzing music, the theory maintains that the songwriter's itinerary cannot be so specific as to render the listener unable to respond without a backstory, indeed it may be better not to know anything at all. Throw all the Led Zeppelin plagiarism issues out the window and just listen; strip The Monkees from auditions and TV shows and again, simply enjoy. Certainly one cannot listen to Lennon's "God" without backstory, but this is the exception, not the rule. And of course, Peter Tork didn’t write music, with but a handful of Monkee exceptions. Although he is many a fan's favorite Monkee, the cute, goofy, often shy one, Peter was to L.A. what Capote was to New York.

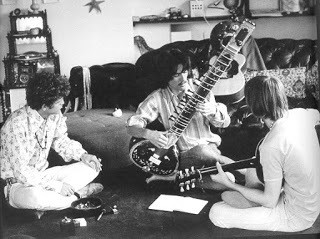

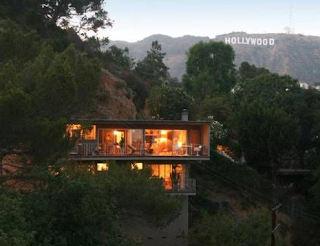

For our purposes in analyzing music, the theory maintains that the songwriter's itinerary cannot be so specific as to render the listener unable to respond without a backstory, indeed it may be better not to know anything at all. Throw all the Led Zeppelin plagiarism issues out the window and just listen; strip The Monkees from auditions and TV shows and again, simply enjoy. Certainly one cannot listen to Lennon's "God" without backstory, but this is the exception, not the rule. And of course, Peter Tork didn’t write music, with but a handful of Monkee exceptions. Although he is many a fan's favorite Monkee, the cute, goofy, often shy one, Peter was to L.A. what Capote was to New York. Peter's first big purchase, after the Monkees became a thing, was a house in the Hollywood Hills. When looking for the perfect bachelor pad, he had in mind "Hills and cool green." His place was the smallest of all of the Monkee mansions, and for most of 1967, he lived there with Joey Richards and Stephen Stills. Inside, the house was mainly orange (Peter's favorite color), with huge picture windows and Danish furniture. Along with Mama Cass's house and David Crosby's, Peter's was one of the biggest party houses in Laurel Canyon. Any day of the week you could find famous folks hanging about. Dave Clark stopped by when he came to America, as did Jimi Hendrix.

Peter's first big purchase, after the Monkees became a thing, was a house in the Hollywood Hills. When looking for the perfect bachelor pad, he had in mind "Hills and cool green." His place was the smallest of all of the Monkee mansions, and for most of 1967, he lived there with Joey Richards and Stephen Stills. Inside, the house was mainly orange (Peter's favorite color), with huge picture windows and Danish furniture. Along with Mama Cass's house and David Crosby's, Peter's was one of the biggest party houses in Laurel Canyon. Any day of the week you could find famous folks hanging about. Dave Clark stopped by when he came to America, as did Jimi Hendrix. By the end of 1967, Peter decided that he needed a bigger house, because "his house was too full of people!" Peter's second larger, more infamous home in the Hollywood Hills (3615 Shady Oak Road, Studio City), was the stuff wet dreams are made of, the legendary Naked Pool Party house. The home, on the Valley side of Laurel, had been owned by comedian Wally Cox and was built by bandleader, Carmen Dragon. It had 14 rooms, a sauna, a wet bar, a film room, and an Olympic Swimming Pool. In his master bedroom, the bed was eight feet by eight feet with a foam mattress six inches thick. He had a four person bathtub put in the master bathroom. The house had an uninterrupted view of the San Fernando Valley, and the living room had six by nine-foot picture windows. Since there weren't any pesky neighbors to worry about, the pool parties were usually skinny-dipping events.

Linda Jones (Davy's first wife) explains: "Whenever we would go over to Peter's house, generally, by the pool, naturally, there were a lot of unclothed people. And since we had our clothes on all of the time, we felt out of place." Not only that, but people often dived into the pool naked from Peter's bathroom window. Peter explains: "I'd rather have nude swimming. It's much easier. There's a certain charge to bodies if they're covered up, and if you remove that, it takes a lot of that extra energy out of things." Like his previous residence, his Studio City place became a hippie haven and a haven for celebrities. When in town to promote Yellow Submarine, George Harrison and Ringo Starr dropped by. The Hollies were personal guests of Peter's when they came to town, as was The Who. Stephen Stills was always there hanging out, as was Buddy Miles, John Sebastian, and members of the Buffalo Springfield. Like most houses of debauchery, Tork's second house had a reputation talked about to this day.

Linda Jones (Davy's first wife) explains: "Whenever we would go over to Peter's house, generally, by the pool, naturally, there were a lot of unclothed people. And since we had our clothes on all of the time, we felt out of place." Not only that, but people often dived into the pool naked from Peter's bathroom window. Peter explains: "I'd rather have nude swimming. It's much easier. There's a certain charge to bodies if they're covered up, and if you remove that, it takes a lot of that extra energy out of things." Like his previous residence, his Studio City place became a hippie haven and a haven for celebrities. When in town to promote Yellow Submarine, George Harrison and Ringo Starr dropped by. The Hollies were personal guests of Peter's when they came to town, as was The Who. Stephen Stills was always there hanging out, as was Buddy Miles, John Sebastian, and members of the Buffalo Springfield. Like most houses of debauchery, Tork's second house had a reputation talked about to this day.

Published on November 02, 2018 04:29

The Monkees Blow Their Minds

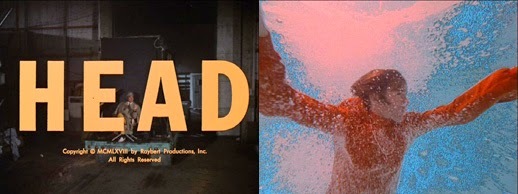

A day late… It was 51 years ago last night, 7:30 Eastern and Pacific, that The Monkees penultimate episode aired (not the second best; the second to last). The show was at the top of its game, but NBC pulled the plug. It wouldn't be for another week that The Monkees changed "Hey, hey" to "Bye, bye," but it was episode 57 when the "Monkees Blew Their Minds," the oddest and shortest episode of all.

A day late… It was 51 years ago last night, 7:30 Eastern and Pacific, that The Monkees penultimate episode aired (not the second best; the second to last). The show was at the top of its game, but NBC pulled the plug. It wouldn't be for another week that The Monkees changed "Hey, hey" to "Bye, bye," but it was episode 57 when the "Monkees Blew Their Minds," the oddest and shortest episode of all. Fittingly, the Fab Faux acknowledged their debt to the Fab Four in the finale, awakening to the Beatles' "Good Morning." It was the first time the Beatles allowed their music to be used in a project that had nothing to do with the band. (John Lennon, it seems, was a huge Monkee fan.) Peter stumbles upon a charlatan mentalist named Oraculo while searching for inspiration to write a song. The Monkees are up for an audition for a ten week gig, and Peter wants to knock everyone's socks off. Oraculo uses a potion to take over Peter's mind, then uses him to both sabotage the Monkees and nab the gig for his mentalist act instead. The guys figure Oraculo is controlling Peter's mind, and set out to save him. Mike distracts Oraculo by posing as an amnesiac who lost a briefcase filled with $50,000 while Micky and Davy rescue Peter. They boys wind up under Oraculo's control, but are unintentionally freed by Oraculo's assistant, Rudy.

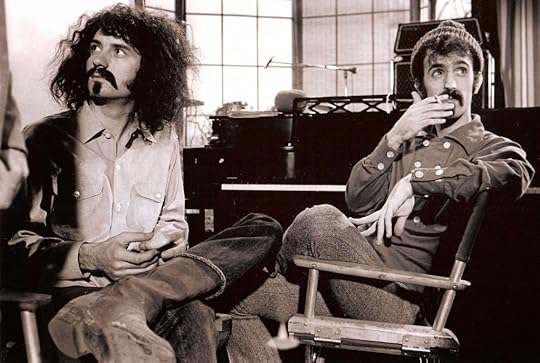

Burgess Meredith makes a cameo as Penguin, one of the club patrons watching Oraculo's act. The highlight of the episode, though, is the opening teaser in which Frank Zappa and Mike Nesmith play each other for a mock interview. Mock is the appropriate word, as they both rip on the Monkees' music as banal and insipid. The pair end up destroying a truck to the beat of a Mothers of Invention song.

"Quite frankly, we were getting a little jaded with the show as it existed," drummer Micky Dolenz said. "We were, to be quite honest, getting tired of the same format," he added, noting that the band contemplated the idea of doing a live variety show or a sketch series like "Laugh-In." "We wanted to do something a little more unusual, a little more out there."

"Quite frankly, we were getting a little jaded with the show as it existed," drummer Micky Dolenz said. "We were, to be quite honest, getting tired of the same format," he added, noting that the band contemplated the idea of doing a live variety show or a sketch series like "Laugh-In." "We wanted to do something a little more unusual, a little more out there."Later that year, Dolenz and bandmates Mike Nesmith, Peter Tork and Davy Jones starred in the bizarre cult classic movie, "Head," but they never did return to TV, except in reruns.

While this episode is the most bizarre, the final episode, while more typical Monkee fare, is equally remarkable in its non-sequitur appearance of Mickey’s friend, Tim Buckley. As the story part of the episode ends, on walks the late singer-songwriter Tim Buckley to perform a solo acoustic version of his classic "Song to the Siren." Buckley was a friend of Dolenz, who thought he should be introduced to the world. The beautiful song would go on to be covered by the Cocteau Twins, This Mortal Coil and Robert Plant. The appearance on the Monkees’ final show remains one of Buckley's finest moments.

While this episode is the most bizarre, the final episode, while more typical Monkee fare, is equally remarkable in its non-sequitur appearance of Mickey’s friend, Tim Buckley. As the story part of the episode ends, on walks the late singer-songwriter Tim Buckley to perform a solo acoustic version of his classic "Song to the Siren." Buckley was a friend of Dolenz, who thought he should be introduced to the world. The beautiful song would go on to be covered by the Cocteau Twins, This Mortal Coil and Robert Plant. The appearance on the Monkees’ final show remains one of Buckley's finest moments.

Published on November 02, 2018 04:17

November 1, 2018

People Say We Monkee Around

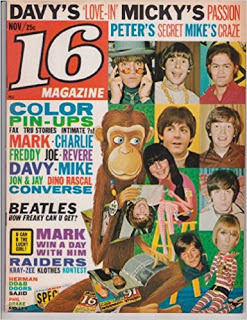

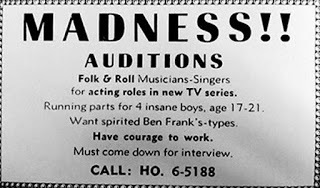

In September 1965, The Hollywood Reporter ran the advertisement to the left. Less than a week later, The Monkees were born.

In September 1965, The Hollywood Reporter ran the advertisement to the left. Less than a week later, The Monkees were born.Englishman Davy Jones was a former jockey who had achieved some initial success on the musical stage (in 1964, Jones appeared with the cast of Oliver! on The Ed Sullivan Show the night of the Beatles' live American debut).

Texan Michael Nesmith served a brief stint in the US Air Force and also recorded for Colpix under the name Michael Blessing. Nesmith was the only one of The Monkees who came in after seeing the trade magazine ad. He showed up to the audition with his laundry.

Micky Dolenz, son of screen actor George M. Dolenz, Sr., had prior screen experience (under the name Mickey Braddock) as the 10-year-old star of the Circus Boy series in the 1950s.

Peter Tork was recommended to producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider by friend Stephen Stills at his own audition. Tork, a skilled multi-instrumentalist, had performed at various Greenwich Village folk clubs before moving west, where he was a dishwasher before becoming a Monkee.

Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider (producers of Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces and The Last Picture Show) came up with an idea for a television series about a rock group. Inspired by Richard Lester's groundbreaking comedies with the Beatles, A Hard Day's Night and Help!, Rafelson and Schneider imagined a situation comedy in which a four-piece band had wacky adventures every week and occasionally burst into song.

The NBC television network liked the idea, and production began on The Monkees in early 1966. Don Kirshner, a music business veteran, was appointed music coordinator for the series, and Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, a producing and songwriting team, signed on to handle much of the day-to-day chores of creating music for the show's fictive band.

The NBC television network liked the idea, and production began on The Monkees in early 1966. Don Kirshner, a music business veteran, was appointed music coordinator for the series, and Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, a producing and songwriting team, signed on to handle much of the day-to-day chores of creating music for the show's fictive band.Avant-garde film techniques—such as improvisation, quick cuts, jump cuts—helped win the show two Emmy awards in 1967 and propelled its four stars to pop stardom. John Lennon called them "the Marx Brothers of rock", but in 1967, The Monkees outsold both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones combined, and went on to sell 50 million records.

Each of the four was given a different personality to portray: Dolenz was the funny one, Nesmith the smart and serious one, Tork the naive one, and Jones the cute one. Their characters were loosely based on their real lives, with the exception of Tork, who was actually a quiet intellectual. The character types also had much in common with the respective personalities of The Beatles, with Dolenz representing the madcap attitude of John Lennon, Nesmith affecting the deadpan seriousness of George Harrison, Tork depicting the odd-man-out quality of Ringo Starr, and Jones conveying the pin-up appeal of Paul McCartney. Generalizations? You betcha.

The Monkees resided in a two-story beach house at 1334 North Beechwood Blvd. in Malibu, California. The front of the first floor was a combination of the living room, dining room and kitchen. In the back, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, was an alcove where the Monkees kept their instruments and rehearsed songs. The walls were covered with various signs and posters, such as the "MONEY IS THE ROOT OF ALL EVIL" sign near the kitchen and the "IN CASE OF FIRE, RUN" sign with an arrow pointing to an old-fashioned fire extinguisher near the front door.

The Monkees premiered on NBC in September 1966; this was just the start of The Monkees phenomenon. "Last Train to Clarksville," the group's first single, was a number one hit a few weeks earlier.

The Monkees were the first group to exploit television and have songs written for them by classic Brill Building artists (Neil Diamond, Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, Harry Nilsson, Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, and Jeff Barry). And what great tunes they were: "Last Train to Clarksville", "Daydream Believer", "A Little Bit Me, a Little Bit You", "I'm a Believer" and "Pleasant Valley Sunday".

So what if the Monkees never played on their first two albums and that their 1968 psychedelic film Head was a turkey. And yes, in one of rock's all-time mismatches, Jimi Hendrix was a bizarre choice as the opening act on their 1967 tour. Forget about that. It hasn't stopped The Monkees' songs from standing the test of time and becoming classic guitar pop hits.

Published on November 01, 2018 08:33

The Monkees

Psychedelic-rock was a bonanza for Hollywood producers because it provided a vehicle to indulge themselves in a myriad of bizarre arrangements. Producer Ed Cobb, for instance, contributed to psychedelic-rock via an artificial combo, San Jose's the Chocolate Watchband, who are credited with Cobb's "The Inner Mystique." In all practicality, the band didn't even exist, though what Cobb created made them seem like The Moody Blues.

Psychedelic-rock was a bonanza for Hollywood producers because it provided a vehicle to indulge themselves in a myriad of bizarre arrangements. Producer Ed Cobb, for instance, contributed to psychedelic-rock via an artificial combo, San Jose's the Chocolate Watchband, who are credited with Cobb's "The Inner Mystique." In all practicality, the band didn't even exist, though what Cobb created made them seem like The Moody Blues. Similarly, David Axelrod penned the "Mass In F Minor" by The Electric Prunes, the first "rock mass." The Electric Prunes do not even appear on the album (the rights to the name "The Electric Prunes" having been signed over to Axelrod). Despite the ideology of the bands behind the music, it was still, a corporate game.

Who Could Forget?Nonetheless, in the mid 60s, TV producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider brought together two actors and two musicians to play a fictional bunch of well-groomed teens who share a house, form a band and hang out. The show was a smash hit, indeed The Monkees outsold The Beatles and The Stones in 1966 (it took Sgt. Pepper in 1967 to knock The Monkees out of the top spot). The Monkees first two albums had at their disposal the best Hollywood studio musicians, and songwriters like Neil Diamond, Carole King, Gerry Goffin and David Gates, not to mention Mike Nesmith (whose "Different Drum" sparked the career of Linda Ronstadt). By Headquarters, the band was producing, playing a myriad of instruments, writing many of the best songs and essentially doing what standards singers had done for the thirty years prior to the 60s without criticism. Despite The Monkees' artifice, they remain an integral part of the psychedelic music scene, and based on the Colgems TV production, each of the band's hits was filmed in a psychedelic setting, making The Monkees one of the key entrants into music video. It was about the music, and The Monkees, though not The Beatles, though manufactured and contrived, managed to produce hits like "Pleasant Valley Sunday," "Daydream Believer" and the ephemeral "Porpoise Song" (from Head).

Who Could Forget?Nonetheless, in the mid 60s, TV producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider brought together two actors and two musicians to play a fictional bunch of well-groomed teens who share a house, form a band and hang out. The show was a smash hit, indeed The Monkees outsold The Beatles and The Stones in 1966 (it took Sgt. Pepper in 1967 to knock The Monkees out of the top spot). The Monkees first two albums had at their disposal the best Hollywood studio musicians, and songwriters like Neil Diamond, Carole King, Gerry Goffin and David Gates, not to mention Mike Nesmith (whose "Different Drum" sparked the career of Linda Ronstadt). By Headquarters, the band was producing, playing a myriad of instruments, writing many of the best songs and essentially doing what standards singers had done for the thirty years prior to the 60s without criticism. Despite The Monkees' artifice, they remain an integral part of the psychedelic music scene, and based on the Colgems TV production, each of the band's hits was filmed in a psychedelic setting, making The Monkees one of the key entrants into music video. It was about the music, and The Monkees, though not The Beatles, though manufactured and contrived, managed to produce hits like "Pleasant Valley Sunday," "Daydream Believer" and the ephemeral "Porpoise Song" (from Head).The Monkees’ 2nd LP, More of the Monkees was a massive hit, though the band had no control over the release of the LP, objecting to the chosen tracks and the rush to market. As a corporate construct, nobody was listening. The TV show was a huge success, inching the Beverly Hillbillies out of the top TV spot, and on the strength of "I'm a Believer," released in November 1966 and selling upwards of two million copies, More of the Monkees rocketed to the top slot. Still The Monkees were labelled as talentless musicians portrayed by actors who had auditioned for their roles, and there was no arguing the point. Because of it, Don Kirshner and Colgems had complete artistic control. Until Headquarters.

David Crosby, Joni Mitchell, Eric Clapton, Owen Elliot, Mickey DolenzBased on the success of the 2nd LP and on "I'm a Believer," The Monkees were the biggest selling band in the world. Mike Nesmith, the most talented of the four, strenuously argued on behalf of the group, hoping to gain their independence from the corporate stanglehold, at one point putting his fist through a wall in Kirshner's office. "That," he told Kirshner, "could have been your face."

David Crosby, Joni Mitchell, Eric Clapton, Owen Elliot, Mickey DolenzBased on the success of the 2nd LP and on "I'm a Believer," The Monkees were the biggest selling band in the world. Mike Nesmith, the most talented of the four, strenuously argued on behalf of the group, hoping to gain their independence from the corporate stanglehold, at one point putting his fist through a wall in Kirshner's office. "That," he told Kirshner, "could have been your face."Ultimately, being the biggest band in the world does indeed have some clout, Kirshner was fired and the lunatics took over the asylum – which, in this case, was a wonderful thing. Headquarters, the resulting album, not only stands as one of the crowning jewels in the Monkees' catalog, but also as one of the finest albums of 1967. Did I say that? It's not just me. Keep in mind that Headquarters was an LP that nearly kept Sgt. Pepper out of the top slot in June 1967, having held the crown since its release in May, without the aid of a "hit." Headquarters is true garage rock, pre-psychedelia with tinges of pop and a bit of country, with nearly every note played by guitarist Nesmith, drummer Micky Dolenz, multi-instrumentalist Peter Tork and "percussionist" Davy Jones (Next to Ray Cooper, Elton John's 70's percussionist, Davy Jones is the best tambourine player around! I say that with a straight face, and Jones really is a decent percussionist, but keep in mind that we're talking tambourine here, you know, Tracy from The Partridge Family). The exception was bass, which played by Chip Douglas, who also produced the album. The songs were primarily by Nesmith, Dolenz and Tork, with two by Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, and one by Brill Building legends Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. Songs like "You Told Me," "You Just May Be the One" and "Sunny Girlfriend" showed Nesmith’s songwriting prowess. "For Pete’s Sake," written by Tork, became the closing theme music for the second season of the TV show, and Dolenz' "Randy Scouse Git" managed to name-check Andy Warhol, the Beatles and counterculture in general in one fell swoop. The song was a hit in the U.K., though the title was changed to "Alternate Title" as a jab at the U.K. label, which demanded it be swapped out since, in British slang, the title translated roughtly to "horny Liverpudlian bastard."

Headquarters was indeed toppled by the Sgt. In June of 1967, but it would toe the line as the planet's penultimate LP well into August. Obviously, as hardly a grade-schooler in ’67, I have a fondness for the LP based more on the fact that I'd discovered it on my own – it was not a hand-me-down from my older brother – but Headquarters, a solid 6 and approaching a 7 on the AM rubric, is an often overlooked gem of an LP. I call the Monkees' Headquarters their Rubber Soul.

The Monkees over the top success with the 3rd LP gave them free-reign to do whatever they chose. What was next, the fourth-wall-shattering, stream-of-consciousness black comedy Head, which mocks war, America, Hollywood, television, the music business and the Monkees themselves, is one of the weirdest and most intriguing rock movies ever made. Quentin Tarantino and Edgar Wright are both dedicated fans. DJ Shadow and Saint Etienne have sampled its dialogue. According to director Bob Rafelson, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones both requested private screenings, while Thomas Pynchon attended a showing disguised as a plumber. (You can't make this up.)

Mike as Frank Zappa; Zappa as MikeBut to the fans who had made the Monkees household names, it might as well never have existed. "The movie dropped like a ball of dark star," said bassist Peter Tork. "The simile of a rock in the water is too mild for how badly that movie did." Though they had produced the previous three albums, Headquarters; The Birds, The Bees and The Monkees; and Pieces, Aquarius, Capricorn and Jones, The Monkees had little artistic control over Head, that task went to producer/writer Bob Rafelson and Jack Nicholson. Over the years the film has become a cult and critical success with a soundtrack that contains music disappointing to teeny-bopper Monkee-fans, but may be among The Monkees' best work, with songs by Carole King and Harry Nilsson, and contributions by Frank Zappa, Leon Russell, Ry Cooder and Stephen Stills.

Mike as Frank Zappa; Zappa as MikeBut to the fans who had made the Monkees household names, it might as well never have existed. "The movie dropped like a ball of dark star," said bassist Peter Tork. "The simile of a rock in the water is too mild for how badly that movie did." Though they had produced the previous three albums, Headquarters; The Birds, The Bees and The Monkees; and Pieces, Aquarius, Capricorn and Jones, The Monkees had little artistic control over Head, that task went to producer/writer Bob Rafelson and Jack Nicholson. Over the years the film has become a cult and critical success with a soundtrack that contains music disappointing to teeny-bopper Monkee-fans, but may be among The Monkees' best work, with songs by Carole King and Harry Nilsson, and contributions by Frank Zappa, Leon Russell, Ry Cooder and Stephen Stills. Strip off the label and disguise the voices a bit and Head could be passed off as a Frank Zappa LP, with a touch of Captain Beefheart. Growing up, it was Headquarters that cemented this writer's relationship with the Pre-Fab Four, the LP that was the proof there was talent amongst the bunch (get it, a banana joke). While The Monkees would shine with two more LPs before their failed attempt at motion pictures, Head retrospectively shines as a psychedelic treat, if forbiddingly inaccessible.

With A Hard Days Night, The Beatles created meta-rock in their self-awareness that Beatlemania was surreal. The Monkees with Head capitalized on the idea by reimagining the self-parodying theme music: "Hey, hey, we are The Monkees,/ You know we love to please a manufactured image with no philosophies" ("Ditty Diego – War Chant"). There are essentially six "songs" on the album. "Porpoise Song (Theme From Head)," sung by Mickey Dolenz and Davy Jones with backing vocals by Leon Russell, and arrangement by Jack Nitzche. "Porpoise Song" was written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, as many Monkee classics were. Then there's Michael Nesmith's "Circle Sky," which accentuates how Nesmith was developing into the writer who would influence music – particularly country music – as much as more "legitimate" artists like Gram Parsons. Then there's Peter Tork's "Can You Dig It" (sung by Micky) with Buffalo Springfield's Dewy Martin on drums, another great Carole King song, "As We Go Along," co-written by Toni Stern, with Neil Young and Ry Cooder picking up the harmonies. Then there's Davy Jones's cover of Nilsson's "Daddy’s Song." The album concludes with "Swami Plus Strings Etc" which includes a reprise of "Porpoise Song" and strings arranged by Ken Thorne.

With A Hard Days Night, The Beatles created meta-rock in their self-awareness that Beatlemania was surreal. The Monkees with Head capitalized on the idea by reimagining the self-parodying theme music: "Hey, hey, we are The Monkees,/ You know we love to please a manufactured image with no philosophies" ("Ditty Diego – War Chant"). There are essentially six "songs" on the album. "Porpoise Song (Theme From Head)," sung by Mickey Dolenz and Davy Jones with backing vocals by Leon Russell, and arrangement by Jack Nitzche. "Porpoise Song" was written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, as many Monkee classics were. Then there's Michael Nesmith's "Circle Sky," which accentuates how Nesmith was developing into the writer who would influence music – particularly country music – as much as more "legitimate" artists like Gram Parsons. Then there's Peter Tork's "Can You Dig It" (sung by Micky) with Buffalo Springfield's Dewy Martin on drums, another great Carole King song, "As We Go Along," co-written by Toni Stern, with Neil Young and Ry Cooder picking up the harmonies. Then there's Davy Jones's cover of Nilsson's "Daddy’s Song." The album concludes with "Swami Plus Strings Etc" which includes a reprise of "Porpoise Song" and strings arranged by Ken Thorne. In an album pool beyond reproach, Head may not be one of the finest LPs of 1968, but remains highly underrated and a glimpse into what came out of the naked party house. Retrospectively, The Monkees and Head, pretty f-ing amazing.

Published on November 01, 2018 05:13

October 31, 2018

Rick Frank and Elephant's Memory

As a writer, you often find yourself on the fringe of celebrity. You speak with these people, you may have had a drink with these people, they may or may not know your name, but they know your face, and some of them know what you do and are extra nice because of it. I have spent my life on the fringe. Over the years, I have hoped to capture for this readership the history of rock music in a way that is beyond celebratory, indeed here at AM, we tend to gush, particularly over those artists from the 60s and 70s.

As a writer, you often find yourself on the fringe of celebrity. You speak with these people, you may have had a drink with these people, they may or may not know your name, but they know your face, and some of them know what you do and are extra nice because of it. I have spent my life on the fringe. Over the years, I have hoped to capture for this readership the history of rock music in a way that is beyond celebratory, indeed here at AM, we tend to gush, particularly over those artists from the 60s and 70s.With that in mind, it was 20 years ago tomorrow that this writer had an exclusive, one that unfortunately never came to fruition.

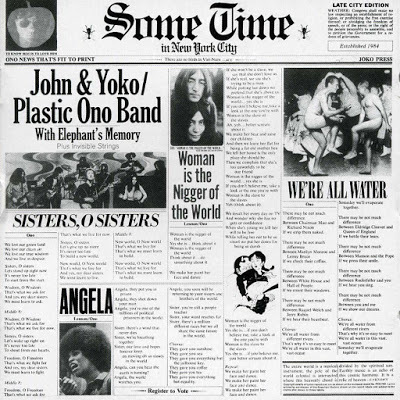

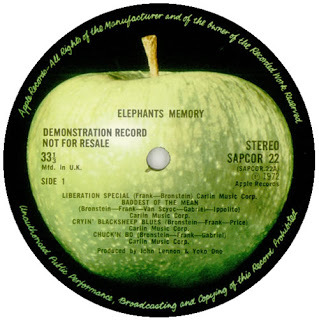

Rick Frank was the drummer for Elephant's Memory, a band that shared two claims to fame. The first was two songs on the Midnight Cowboy Soundtrack, but more importantly, Elephant's Memory was the backup band for John Lennon's Madison Square Garden gig known as Sometime in New York City, when Lennon's band was deported from the U.S. for illicit drug use.

I have never been much of a live album fan. I take an interest, wanting to hear the inconsistencies, those mistakes when left in providing character, but there are few LPs that I return to as essential in my canon; Rick Wakeman's Journey to the Center of the Earth being one incredible example and Lou Reed's Rock 'n' Roll Animal, which contains my all-time favorite guitar duet. I won't pretend to love Lennon at Madison Square, finding it overly abrasive at times, but it remains essential in my collection based on my association with Rick Frank.

AM tends to avoid controversy in general, but we've never shied away from the underbelly of rock music, we just prefer to address the music. Nonetheless, in 1996 I took a position in a mental health facility. Our clientele was what you would expect in a suburban New Jersey location. But the facility did indeed entertain its share of celebrity. From an incredible slap bassist to Rick Frank, I was witness to what the industry could do to one, particularly in a facility that addressed dual diagnoses.

Rick Frank was admitted to screening in 1998 with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. He checked himself into the medical center during an episode of extreme mania and anxiety coupled with his psychosis and drug use. When he appeared on my caseload I didn't know who he was. Slowly the bits and pieces began to emerge. I did my research and found his picture and his name and even an advert from an old Philadelphia underground newspaper called The Drummer. I got the CD at Sam Goody to find Rick Frank's photo on the back. Writing this today, of course, it was simpler; I just looked on Wikipedia.

Elephant's Memory as it turned out, was a big deal. Not a very big deal, but a big deal who at one time boasted Carly Simon as their vocalist and whose name was modified for the Lennon live LP as Plastic Ono Elephant's Memory Band.

Frank was mild-mannered and a gentleman. He spoke so softly at first that his voice was nearly imperceptible. He talked of Lennon and Ono and gibberish. He spoke of his depression and his drug use. What was more interesting was that here he was in screening, strung out, manic, suicidal, but he wanted to talk about me. He said to "get his mind off it all." I asked what he meant by "it all," and he said "all of it, man." The words made little sense, but you knew the meaning through his eyes.

At the medical center, mental health patients would cycle through, and some, like Frank, would check themselves in, detox, talk to the doc, get an increase in medication and in a week they'd be gone. I visited Rick twice daily for several weeks and in that time we talked about Lennon's rumored deportation and his home life, which was simple, Frank and his significant other sitting on a sofa watching TV. We talked about fame, about the industry, about the recording process and about syncopation. We talked about Star Wars and Harry Potter. We never did talk about Elephant's Memory, Frank seemingly reluctant. I guess he'd told his story endlessly. To me, he wanted to talk about anything else. In the short time that I knew him, he looked upon me as a friend he could open up to.

Formed in 1967 by Rick and saxophonist Stan Bronstein, who met on the New York City strip-joint circuit, the group was an eclectic Frank Zappa-like mix of psychedelia, jazz, and acid-rock, and delivered a truly bizarre stage show complete with inflatable stage sets. Their first album, Elephant's Memory, was released in 1969 on Buddah Records, a label more famous for bubblegum pop groups than whacked-out horn bands.

Formed in 1967 by Rick and saxophonist Stan Bronstein, who met on the New York City strip-joint circuit, the group was an eclectic Frank Zappa-like mix of psychedelia, jazz, and acid-rock, and delivered a truly bizarre stage show complete with inflatable stage sets. Their first album, Elephant's Memory, was released in 1969 on Buddah Records, a label more famous for bubblegum pop groups than whacked-out horn bands.Two tracks from the LP, "Jungle Gym at the Zoo" and "Old Man Willow," found their way onto the Midnight Cowboy movie soundtrack later that year, which gave the group some visibility, but didn't translate into sales. A second LP, 1970's Take It to the Streets, had even less commercial impact. Then came John Lennon and Some Time in New York City, and Elephant's Memory had their moment in the sun. They released a third album, also called Elephant's Memory and featuring David Peel, on Apple Records later that year, then backed up Yoko Ono on 1973's Approximately Infinite Universe. Angels Forever appeared in 1974, but no one noticed.

While my time with Frank was brief, I've spent all these years remembering those weeks together when I was able to simply sit with him and talk. I think he appreciated that. He was released from the hospital and returned home. I visited him once in an outreach and we sat and watched Jeopardy. He answered every question right.

Twenty years ago today I didn't know him. He checked into the hospital the next day and I was assigned to his case. Our association, indeed our friendship lasted only a month, and then, on December 7, 1998, Rick Frank died at his home in Long Branch. If I close my eyes I can see him sitting there in his living room playing Jeopardy.

Published on October 31, 2018 07:33

October 17, 2018

We'll Be Right Back...

AM is officially on vacation. We're off to Dublin and Belfast. Please don't forget about us. We will be back on the 25th! In the meantime, get out the portable hi-fi and a good book.

Published on October 17, 2018 12:52