R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 53

November 22, 2018

50 Years On - The Beatles' White Album

Yep, Ob-La-Di. 50 years to the day since The Beatles was released, it's back in the LP top ten. Landing at No. 5 on November 22, 1968, the album colloquially known as The White Album would rise to No. 1 and stay there from late December through March 1969.

Yep, Ob-La-Di. 50 years to the day since The Beatles was released, it's back in the LP top ten. Landing at No. 5 on November 22, 1968, the album colloquially known as The White Album would rise to No. 1 and stay there from late December through March 1969. The White Album features the band's most straightforward, if eclectic, collection, of hits since Help. Giles Martin, the son of Beatles producer George Martin, dove into the Abbey Road archives to remix and repackage the LP in much the same way he did with Sgt. Pepper last year. The set also features Martin's production of the acoustic "Esher" Sessions, recorded not at Abbey Road but at George Harrison's home in May 1968, and several unreleased tracks such McCartney's outrageous first take of "Hey Jude" and the 102nd take of Harrison's "Not Guilty." It is by far The Beatles most far-reaching album, but unlike the psychedelic and heavy-handed production of Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour, this is Beatles rock 'n' roll picking up where "Hey, Jude" left off.

Within the plain white wrapper are references to earlier songs (brilliant in "Glass Onion," especially the touch of recorders from "Fool on the Hill"), Bob Dylan ("Yer Blues"), Chubby Checker and the Beach Boys ("Back in U.S.S.R.") and the Ska of Desmond Decker and the Aces on "Life Goes On." It's a collection rather than a concept that takes on rock, rock 'n' roll (especially Elvis Presley), Nashville Country and Western, Latin America, Calypso, Indian traditional music (inevitably), musique concrete and the avant-garde. From the first track, "Back in the U.S.S.R.," with the line "Let me hear your balalaikas ringing out, come and keep your comrade warm," the listener is instantly wrapped in something brand new. So many songs, so many directions, and so far ahead of its time. "Yer Blues" was a favorite of the band during the sessions. Ringo recalled that just the four of them went into a small studio room and recorded the opener. Just the four of them. While Paul referred to the LP as the "tension album" based on Yoko following John around the studio, there remains a sense that this was the only direction the band could take as they matured from mop tops to young men.

Published on November 22, 2018 07:34

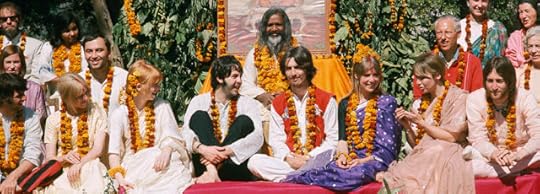

Won't You Come Out to Play?

"Dear Prudence" written by Lennon and credited to Lennon/McCartney is the second track from the double LP The Beatles (colloquially known as The White Album). The White Album is The Beatles' licorice (as Jerry Garcia said, not a lot of people like licorice, but those who like licorice, really like licorice), an anti-concept with each track taking an individualized approach, with only one concurrent theme: most of the tracks were written in India. The track's subject is actress Mia Farrow's sister, Prudence, who was at the ashram when the Beatles studied with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi early in 1968. Farrow became so serious about her meditation that she became a recluse and rarely venturing out of the cottage in which she was living. Someone asked Lennon make sure she came out more often to socialize.

In the song, Lennon asks Prudence to "open up your eyes" and "see the sunny skies" reminding her that she is "part of everything." The song was a simple plea to a friend to snap out of it. Lennon said later that "She'd been locked in for three weeks and was trying to reach God quicker than anyone else." According to Farrow: "I would always rush straight back to my room after lectures and meals so I could meditate. John, George and Paul would all want to sit around jamming and having a good time and I'd be flying into my room. They were all serious about what they were doing, but they just weren't as fanatical as me."

Lennon didn't play the song for Farrow while they were in India together. Prudence later said that "George was the one who told me about it," as The Beatles were leaving the ashram. According to Farrow: "I was flattered. It was a beautiful thing to have done." The lyrics of the song are simple and innocent and praise the beauty of nature: "The sun is up, the sky is blue, it's beautiful, and so are you, Dear Prudence."

Lennon didn't play the song for Farrow while they were in India together. Prudence later said that "George was the one who told me about it," as The Beatles were leaving the ashram. According to Farrow: "I was flattered. It was a beautiful thing to have done." The lyrics of the song are simple and innocent and praise the beauty of nature: "The sun is up, the sky is blue, it's beautiful, and so are you, Dear Prudence."

While on the surface the song could be seen as a kind rebuke to excessive spirituality, but at its heart "Dear Prudence" makes a powerful statement for an integral contemplative perspective: where Prudence (and by extension, anyone who listens to the song) is "part of everything" and is/are invited to "look around, round, round" and see the beauty in all things. The song is a reminder that there is really no line separating "spirituality" from the rest of life: it's all connected. The point behind a contemplative practice, after all, is not merely to lose ourselves in meditation, but rather to find, through the disciplined attention of silent awareness, that we really are "part of everything" and it's all beautiful — and so are we. Now that's some hippie shit right there.

In the song, Lennon asks Prudence to "open up your eyes" and "see the sunny skies" reminding her that she is "part of everything." The song was a simple plea to a friend to snap out of it. Lennon said later that "She'd been locked in for three weeks and was trying to reach God quicker than anyone else." According to Farrow: "I would always rush straight back to my room after lectures and meals so I could meditate. John, George and Paul would all want to sit around jamming and having a good time and I'd be flying into my room. They were all serious about what they were doing, but they just weren't as fanatical as me."

Lennon didn't play the song for Farrow while they were in India together. Prudence later said that "George was the one who told me about it," as The Beatles were leaving the ashram. According to Farrow: "I was flattered. It was a beautiful thing to have done." The lyrics of the song are simple and innocent and praise the beauty of nature: "The sun is up, the sky is blue, it's beautiful, and so are you, Dear Prudence."

Lennon didn't play the song for Farrow while they were in India together. Prudence later said that "George was the one who told me about it," as The Beatles were leaving the ashram. According to Farrow: "I was flattered. It was a beautiful thing to have done." The lyrics of the song are simple and innocent and praise the beauty of nature: "The sun is up, the sky is blue, it's beautiful, and so are you, Dear Prudence."While on the surface the song could be seen as a kind rebuke to excessive spirituality, but at its heart "Dear Prudence" makes a powerful statement for an integral contemplative perspective: where Prudence (and by extension, anyone who listens to the song) is "part of everything" and is/are invited to "look around, round, round" and see the beauty in all things. The song is a reminder that there is really no line separating "spirituality" from the rest of life: it's all connected. The point behind a contemplative practice, after all, is not merely to lose ourselves in meditation, but rather to find, through the disciplined attention of silent awareness, that we really are "part of everything" and it's all beautiful — and so are we. Now that's some hippie shit right there.

Published on November 22, 2018 07:16

November 21, 2018

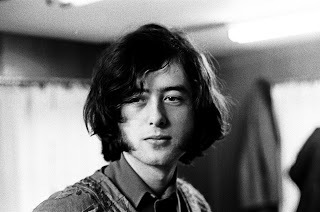

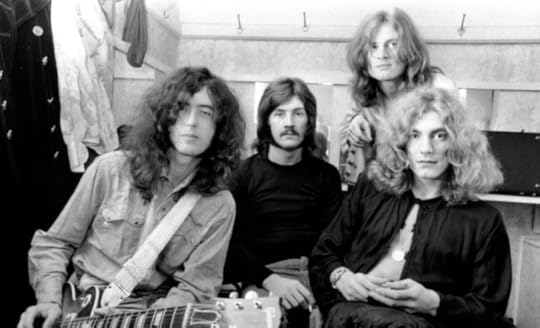

Zeppelin: Let's Get This Out of the Way - Part 3, Page

In 1965, Burt Jansch first learned the traditional Irish ballad "Blackwaterside" from folkie friend Anne Briggs. Jansch went on to record his very stylized version for the 1966 solo LP Jack Orion. Purportedly, the singer/guitarist Al Stewart of "Year of the Cat" fame followed Jansch's live shows and learned the arrangement, which he taught to Jimmy Page in the studio while the two were recording Stewart's second album, Love Chronicles. While Stewart admits to teaching the arrangement to Page, there is conflict as to when, Stewart insisting that his session with Page was in 1965. On Led Zeppelin, Page recorded the song, calling it "Black Mountain Side," giving Jansch no credit while adding himself, rather than crediting it as "Trad." as many artists did with such songs (including Jansch: "Traditional, arranged Jansch.") There is a case to be made that Page was doing nothing different than what Jansch did with his sources, and what has been traditionally blues/folk protocol. Of course the conflicting dates conflagrate the scenario further.

In 1965, Burt Jansch first learned the traditional Irish ballad "Blackwaterside" from folkie friend Anne Briggs. Jansch went on to record his very stylized version for the 1966 solo LP Jack Orion. Purportedly, the singer/guitarist Al Stewart of "Year of the Cat" fame followed Jansch's live shows and learned the arrangement, which he taught to Jimmy Page in the studio while the two were recording Stewart's second album, Love Chronicles. While Stewart admits to teaching the arrangement to Page, there is conflict as to when, Stewart insisting that his session with Page was in 1965. On Led Zeppelin, Page recorded the song, calling it "Black Mountain Side," giving Jansch no credit while adding himself, rather than crediting it as "Trad." as many artists did with such songs (including Jansch: "Traditional, arranged Jansch.") There is a case to be made that Page was doing nothing different than what Jansch did with his sources, and what has been traditionally blues/folk protocol. Of course the conflicting dates conflagrate the scenario further.Janschites will insist that Page absconded Burt Jansch's arrangement, but I would contend that the evolution of the traditional Irish tune begins in 1959 with Isla Cameron’s recording, moving onward through Winnie Ryan, Liam Clancy, Paddy Tunney and ebbing with Briggs and Jansch. What Page failed to do is to acknowledge the "Trad.," though in many ways, Jimmy's version broke tradition by incorporating an alternate musical framework (the Celtic, Indian and Arabic connection that he called "CIA") while emphasizing his arrangement with tablas and the accent you get by using DADGAD, instead of the drop D Jansch used. It's quite ingenious really, and of course beautifully played as well. So who's right here? The press and the world has turned on Plant and Page and Zeppelin, when there is room in AM's focus for both "Blackwaterside" and "Black Mountain Side," "Taurus" and "Stairway."

But back to the original premise: Spirit is long forgotten and Pentangle (Burt Jansch’s jazz rock outfit) suffered under the insufferable vocals of Jacqui McShee. Jansch’s Jack Orion LP is a great historic look into British folk, but far from listenable, with "Blackwaterside" the obvious exception. Zeppelin on the other hand did what they did with more pomp and circumstance, originality, sexuality and innovation than any other rock band of its era. 100 years from now, we will all still be reading Shakespeare and listening to "Stairway to Heaven."

Published on November 21, 2018 05:06

November 20, 2018

Zeppelin: Let's Get This Out of the Way - Part 2, Page and "Stairway"

Led Zeppelin did not steal a riff for the introduction to its classic rock anthem "Stairway to Heaven," a federal court jury decided on June 23, 2016 in Los Angeles. Experts for both sides dissected the compositions, agreeing mainly that they shared a descending chord progression that dates back three centuries as a building block in countless songs.

Led Zeppelin did not steal a riff for the introduction to its classic rock anthem "Stairway to Heaven," a federal court jury decided on June 23, 2016 in Los Angeles. Experts for both sides dissected the compositions, agreeing mainly that they shared a descending chord progression that dates back three centuries as a building block in countless songs.From a legal perspective (and for me, this is of lesser importance), there is a contractual business arrangement referred to as "work for hire." Musicians, particularly black musicians in the early part of the 20th Century and young artists eager to get a foot in the door in the 1960s, often fell victim to the "work for hire" approach of the major labels, meaning that intellectual property belongs to the label. Such is the case with Spirit's "Taurus," the instrumental piece that was purportedly ripped by Jimmy Page for "Stairway to Heaven." Though not a real Spirit fan, this writer has a particular affinity for the rock instrumental, with "Taurus" among my favorites, alongside "Mood For a Day," "Embryonic Journey" and "Sparks" from Tommy. Despite my affection for the song, Spirit's case against Page should have, from a legal standpoint, been "dismissed with prejudice," in that the composer has no legal rights to the song (these belong to Ode Records). In addition, a statement by the composer, Randy California, in 1991 states, "I'll let them have the beginning of 'Taurus' for their song without a lawsuit." Finally, based on a legal understanding called "laches," a contract's equivalent to the statute of limitations, the 43 years that transpired between the release of "Stairway to Heaven" and the recent lawsuit should negate the legal action.

In the case, Led Zeppelin argued, "The similarity between 'Taurus' and 'Stairway' is limited to a descending chromatic scale of pitches resulting from 'broken' chords or arpeggios and which is so common in music it is called a minor line cliché. There is no substantial similarity in the works' structures, which are markedly different. Neither is there any harmonic or melodic similarity beyond the unprotected descending line." Despite the mumbo-jumbo associated with legalese, the opening notes to "Stairway to Heaven" are indeed similar to what is played 45 seconds into Spirit's "Taurus." Both are arpeggiated A Minor chords in the fifth fret barre position. The first three notes of the arpeggiated figure are close to each other and the descending bass is also similar until the end, when Page adds a note. Page's guitar line is more sophisticated, in that he's finger-picking and playing two notes at the same time. As the bass line descends, Page plays a simple but effective counter melody on the high E string;"Taurus"simply plays out the notes of the chord. Does Randy California truly believe that he has exclusivity to arpeggiating a minor chord? Should he subsequently go after Tom Petty for the guitar part for "Into the Great Wide Open?" The simple answer is, of course not; he died in 1997. The Case regarding "Stairway" was not filed by Randy Wolfe (California), but by an attorney for his estate, 43 years after the fact. None of this really matters, though. What does matter is that four seconds of a similar riff does not constitute authorship for the most iconic song in the rock canon.

In the case, Led Zeppelin argued, "The similarity between 'Taurus' and 'Stairway' is limited to a descending chromatic scale of pitches resulting from 'broken' chords or arpeggios and which is so common in music it is called a minor line cliché. There is no substantial similarity in the works' structures, which are markedly different. Neither is there any harmonic or melodic similarity beyond the unprotected descending line." Despite the mumbo-jumbo associated with legalese, the opening notes to "Stairway to Heaven" are indeed similar to what is played 45 seconds into Spirit's "Taurus." Both are arpeggiated A Minor chords in the fifth fret barre position. The first three notes of the arpeggiated figure are close to each other and the descending bass is also similar until the end, when Page adds a note. Page's guitar line is more sophisticated, in that he's finger-picking and playing two notes at the same time. As the bass line descends, Page plays a simple but effective counter melody on the high E string;"Taurus"simply plays out the notes of the chord. Does Randy California truly believe that he has exclusivity to arpeggiating a minor chord? Should he subsequently go after Tom Petty for the guitar part for "Into the Great Wide Open?" The simple answer is, of course not; he died in 1997. The Case regarding "Stairway" was not filed by Randy Wolfe (California), but by an attorney for his estate, 43 years after the fact. None of this really matters, though. What does matter is that four seconds of a similar riff does not constitute authorship for the most iconic song in the rock canon.The only certainty here is that Led Zeppelin utilized those seconds far more effectively than Spirit. "Taurus" starts with a soft 45 second barrage of "Nights in White Satin" orchestration, pretty and lilting, before the guitar floats in and out of the song without going anywhere. The song didn’t go anywhere either, despite having a three-year head start on "Stairway." To be frank, there's a reason "Stairway to Heaven" is a big stupid rock epic that the whole world is sick of (I mean the most iconic song in the rock canon) and "Taurus" is a deep album cut for a band that has largely been forgotten (except by Randy California's lawyers). (Check. This is indeed the same argument used to elevate "Whole Lotta Love" over Willie Dixon's "You Need Love.")

Another interesting legal aspect with regard to plagiarism lies with culpability. R. Gary Klausner, District Court Judge on the case ruled that, "The Court finds that the Plaintiff has not proffered sufficient evidence to raise a triable issue of fact that Led Zeppelin members had direct access to 'Taurus.'" Essentially, based on the precedence of earlier cases involving lyrics and music, similar pieces by disparate artists can be created simultaneously. "Taurus" is a simple, beautiful instrumental; "Stairway" a rock anthem. Two songs, two styles, two separate entities.

Published on November 20, 2018 05:22

November 19, 2018

Zeppelin: Let's Get This Out of the Way - Part 1

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. Othello: Shakespeare. MacBeth: Shake. No, no and no: Arthur Brook/Ovid (R+J); Hecatommithi, a novella by Cinthio (Othello); Holinshed's Chronicles ("The Scottish Play") - but if you said so, you'd sound like an idiot. Because you would be. According to Ecclesiastes, there is nothing new under the sun, so frankly, shut the hell up already about Led Zeppelin. The allegations have indeed brought lawsuits, mostly (five to be exact) settled out of court discretely with the evidence truncated, and in the most famous case, "Whole Lotta Love," the song credits amended to include Willie Dixon, who claimed that Robert Plant used lyrics from his song "You Need Love." Here we go: "You've got yearnin' and I got burnin'/ Baby you look so sweet and cunnin'./ Baby way down inside, woman you need love." Willie Dixon obviously was the first person ever to say what guys say in the heat of the moment (wait, did I just steal that from Asia?).

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. Othello: Shakespeare. MacBeth: Shake. No, no and no: Arthur Brook/Ovid (R+J); Hecatommithi, a novella by Cinthio (Othello); Holinshed's Chronicles ("The Scottish Play") - but if you said so, you'd sound like an idiot. Because you would be. According to Ecclesiastes, there is nothing new under the sun, so frankly, shut the hell up already about Led Zeppelin. The allegations have indeed brought lawsuits, mostly (five to be exact) settled out of court discretely with the evidence truncated, and in the most famous case, "Whole Lotta Love," the song credits amended to include Willie Dixon, who claimed that Robert Plant used lyrics from his song "You Need Love." Here we go: "You've got yearnin' and I got burnin'/ Baby you look so sweet and cunnin'./ Baby way down inside, woman you need love." Willie Dixon obviously was the first person ever to say what guys say in the heat of the moment (wait, did I just steal that from Asia?). Sorry, I get it, intellectual property, blah blah blah, but this is simply fucking to music - the improv of sex - and it doesn't belong to Plant, nor does it belong to Dixon. The Small Faces' Steve Marriot has a far better case with Plant's lifted stylings, but push to shove reality: Romeo and Juliet: Shakespeare; "Whole Lotta Love:" Zeppelin. This (and only this) is the sexiest, dirtiest song ever recorded and not Willie Dixon's Song of the South rendition. Muddy Waters' take, bluesy and incredible as it is, holds nothing on Zeppelin's. (Not a soul, by the way, has challenged John Williams for lifting the Star Wars Theme straight from Erich Wolfgang Korngold's incidental music for King's Row. Why? Because Korngold's original pales in comparison.)

Sorry, I get it, intellectual property, blah blah blah, but this is simply fucking to music - the improv of sex - and it doesn't belong to Plant, nor does it belong to Dixon. The Small Faces' Steve Marriot has a far better case with Plant's lifted stylings, but push to shove reality: Romeo and Juliet: Shakespeare; "Whole Lotta Love:" Zeppelin. This (and only this) is the sexiest, dirtiest song ever recorded and not Willie Dixon's Song of the South rendition. Muddy Waters' take, bluesy and incredible as it is, holds nothing on Zeppelin's. (Not a soul, by the way, has challenged John Williams for lifting the Star Wars Theme straight from Erich Wolfgang Korngold's incidental music for King's Row. Why? Because Korngold's original pales in comparison.)More importantly, this writer's purview is not that Led Zeppelin (Plant in particular) can claim intellectual ownership of lyrics like those in "The Lemon Song," which clearly reconstruct "Killing Floor" by Chester Burnett (a.k.a. Howlin' Wolf), but that lawsuits and purported plagiarism are absurd when one analyzes both the history of the blues, and its construct. If Plant indeed needs to include Howlin' Wolf in the credits to "The Lemon Song," then Howlin' Wolf must also qualify "Killing Floor" by including Robert Johnson. By extension, Led Zeppelin, Howlin' Wolf and Robert Johnson must re-credit their sexually explicit "lemon" tracks with the addition of Joe Williams for his 1929 penned tune, "I Want it Awful Bad," which is, if not the original, at least the oldest existing lyrics to take the lemon in hand (so to speak): "You squeezed my lemon,/ Caused my juice to run." To emphasize the details: not Zeppelin, not Burnett, not Johnson, not Roosevelt Sykes ("She Squeezed My Lemon"), not Memphis Minnie nor Sonny Boy Williamson can lay claim to the lyrics of Joe Williams.

Equally compelling is the "Killing Floor" reference. The killing floor is classic/timeless blues phrasing that initially referred to the slaughterhouse. After the Civil War, many black migrants found work in the slaughterhouses on the "killing floor," a term that came to mean hitting rock bottom. Plant's use of the lyric as a white British lyricist in "The Lemon Song" is ridiculous, but again, it is far from plagiarism.

The point is simple. So much energy and clever naysaying on the web and in print goes into proving that Plant and Page plagiarized the blues greats, overlooking the inherent plagiarism in the genre's construct: blues borrows.

By the way, there really was a William Shakespeare who wrote 37 plays and 154 sonnets. Not a soul among us reads Sir Francis Bacon's Hamlet.

Published on November 19, 2018 05:47

November 18, 2018

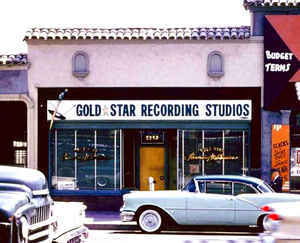

In the Studio - Rock's Most Productive Year

From 1965 through 1968, there were three distinct shifts away from rock 'n' roll and toward rock. Dylan crafted a focused socio-political bent electrifying the results; the bad boys of rock like The Who and The Stones took the stage in a JD stance of mayhem and volume, while The Beatles and The Beach Boys took to the studio.

From 1965 through 1968, there were three distinct shifts away from rock 'n' roll and toward rock. Dylan crafted a focused socio-political bent electrifying the results; the bad boys of rock like The Who and The Stones took the stage in a JD stance of mayhem and volume, while The Beatles and The Beach Boys took to the studio.  Simultaneously, a shift away from rock 'n' roll's country/blues roots arose alongside the complexities of the free jazz of Coltrane and Miles Davis. Rock was born at the confluence of blues and country, but after '66, blues and country/folk became mere ingredients (two among many) of a much more complex recipe. The lengthy "acid" jams of the Velvet Underground, of Jefferson Airplane, of the Grateful Dead and of Pink Floyd, relied on a loose musical infrastructure that was no longer related to rhythm 'n' blues (let alone country music). It was, on the other hand, very similar to the format of jazz music played in the lofts and the clubs that many psychedelic rock musicians attended. The indirect influence of free jazz gained prominence in the psychedelic era, fueling its musical revolution and emancipating rock music from its blues foundations.

Simultaneously, a shift away from rock 'n' roll's country/blues roots arose alongside the complexities of the free jazz of Coltrane and Miles Davis. Rock was born at the confluence of blues and country, but after '66, blues and country/folk became mere ingredients (two among many) of a much more complex recipe. The lengthy "acid" jams of the Velvet Underground, of Jefferson Airplane, of the Grateful Dead and of Pink Floyd, relied on a loose musical infrastructure that was no longer related to rhythm 'n' blues (let alone country music). It was, on the other hand, very similar to the format of jazz music played in the lofts and the clubs that many psychedelic rock musicians attended. The indirect influence of free jazz gained prominence in the psychedelic era, fueling its musical revolution and emancipating rock music from its blues foundations.  Record PlantRock "festivals" played a major role as well in this (r)evolution with the "Human Be-in" in January 1967 the first of its kind. The music of the hippies was an evolution of folk-rock. It was renamed "acid-rock" because the original idea was that of providing a soundtrack to the LSD parties, a soundtrack that would reflect as closely as possible the effects of an LSD "trip." The Dead took it so far as to have an acid test (did you study?). Psychedelic music was the rock equivalent of abstract painting (Jackson Pollock), free-jazz (Ornette Coleman) and beat poetry (Allen Ginsberg).

Record PlantRock "festivals" played a major role as well in this (r)evolution with the "Human Be-in" in January 1967 the first of its kind. The music of the hippies was an evolution of folk-rock. It was renamed "acid-rock" because the original idea was that of providing a soundtrack to the LSD parties, a soundtrack that would reflect as closely as possible the effects of an LSD "trip." The Dead took it so far as to have an acid test (did you study?). Psychedelic music was the rock equivalent of abstract painting (Jackson Pollock), free-jazz (Ornette Coleman) and beat poetry (Allen Ginsberg). By Revolver, the psychedelic era came to prominence finding its zenith in Sgt. Pepper. In-between were rock freakouts like The Mothers, Kaleidoscope, Days of Future Passed, The Dead’s "That’s It For the Other One" and Pink Floyd’s Piper at the Gates of Dawn.

1968, though, was a year in which rock truly diversified. Psychedelia met its match with The Beatles (The White Album), a full reversal of its legendary predecessors Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour, by venturing more fully into rock; and Dylan fucked with our sensibilities yet again with the acoustic John Wesley Harding – a wishy-washy response to the negativity surrounding the electric Dylan of Blonde on Blonde, or Dylan once again more simply being defiant. In 1968, the acid wore off, and while the music would veer off into a myriad of experimentation and innovation, the concentration was seemingly hardcore "rockin' out," a term coined sometime that same year.

1968, though, was a year in which rock truly diversified. Psychedelia met its match with The Beatles (The White Album), a full reversal of its legendary predecessors Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour, by venturing more fully into rock; and Dylan fucked with our sensibilities yet again with the acoustic John Wesley Harding – a wishy-washy response to the negativity surrounding the electric Dylan of Blonde on Blonde, or Dylan once again more simply being defiant. In 1968, the acid wore off, and while the music would veer off into a myriad of experimentation and innovation, the concentration was seemingly hardcore "rockin' out," a term coined sometime that same year.  The shear wealth of 1967 far overshadows 1968, which, while still a stellar year (Bookends, Electric Ladyland, Music From Big Pink, Beggars Banquet, Cheap Thrills, White Heat/White Light and Waiting for the Sun), was more about the emergence of new music with the forming of Led Zeppelin, King Crimson, Alice Cooper, Joe Cocker, The Flying Burrito Brothers, CSN + Y and Yes. Indeed, something was brewing to bring about Abbey Road, Led Zeppelin I and II, Tommy, Let It Bleed, Hot Buttered Soul, In the Court of the Crimson King and Trout Mask Replica. With that said, 1968 may have been Rock's most important year in the studio.

The shear wealth of 1967 far overshadows 1968, which, while still a stellar year (Bookends, Electric Ladyland, Music From Big Pink, Beggars Banquet, Cheap Thrills, White Heat/White Light and Waiting for the Sun), was more about the emergence of new music with the forming of Led Zeppelin, King Crimson, Alice Cooper, Joe Cocker, The Flying Burrito Brothers, CSN + Y and Yes. Indeed, something was brewing to bring about Abbey Road, Led Zeppelin I and II, Tommy, Let It Bleed, Hot Buttered Soul, In the Court of the Crimson King and Trout Mask Replica. With that said, 1968 may have been Rock's most important year in the studio.

Published on November 18, 2018 05:51

November 17, 2018

Finn McCool and Houses of the Holy

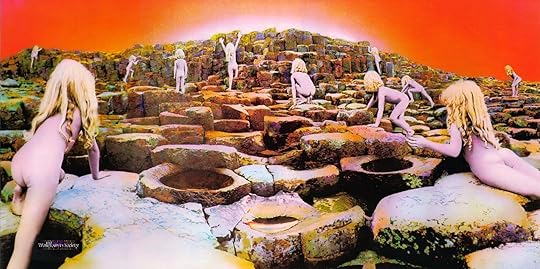

Led Zeppelin released their fifth studio album, Houses of the Holy, on March 28, 1973. The album cover is a collage of photographs taken at the Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland, by Aubrey Powell. The cover was inspired by the ending of Arthur C. Clarke’s novel Childhood's End in which thousands of naked children, only slightly resembling the human race in basic forms, metamorph into the Overmind.

Led Zeppelin released their fifth studio album, Houses of the Holy, on March 28, 1973. The album cover is a collage of photographs taken at the Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland, by Aubrey Powell. The cover was inspired by the ending of Arthur C. Clarke’s novel Childhood's End in which thousands of naked children, only slightly resembling the human race in basic forms, metamorph into the Overmind. The Giant's Causeway is a geologic oddity comprised of 40,000 interlocking basalt columns, the result of an ancient volcanic eruption, and is located in County Antrim on the northeast coast of Northern Ireland. The two children who modeled for the cover were siblings Stefan and Samantha Gates. The photoshoot was a frustrating affair over the course of ten days. Shooting was done first thing in the morning and at sunset in order to capture the light at dawn and dusk, but the desired effect was never achieved due to constant rain and clouds. The photos of the two children were taken in black and white and multi-printed to create the effect of 11 children as seen on the album cover.

The Giant's Causeway is a geologic oddity comprised of 40,000 interlocking basalt columns, the result of an ancient volcanic eruption, and is located in County Antrim on the northeast coast of Northern Ireland. The two children who modeled for the cover were siblings Stefan and Samantha Gates. The photoshoot was a frustrating affair over the course of ten days. Shooting was done first thing in the morning and at sunset in order to capture the light at dawn and dusk, but the desired effect was never achieved due to constant rain and clouds. The photos of the two children were taken in black and white and multi-printed to create the effect of 11 children as seen on the album cover.Like Led Zeppelin IV, neither the band's name nor the album title was printed on the sleeve. However, manager Peter Grant did allow Atlantic Records to add a wrap-around band to UK copies of the sleeve that had to be broken or slid off to access the record. This hid the children's buttocks from general display; still the album was either banned or unavailable in some parts of the Southern United States for several years. Despite any ongoing controversy, it clearly stands alongside LP covers like Pepper, Tommy, King Crimson's In the Court of the Crimson King and Thick as a Brick.

While Childhood's End rises head and shoulders over nearly every other Science Fiction novel, we'll leave that to you. Instead, here’s the story of Fionn (Finn) McCool:

While Childhood's End rises head and shoulders over nearly every other Science Fiction novel, we'll leave that to you. Instead, here’s the story of Fionn (Finn) McCool:A giant named Benandonner lived on the Scottish coast. McCool and Benandonner did not see eye to eye and Finn challenged his Scottish nemesis to a fight as they threatened each other from across the water. Building a causeway so he could reach his enemy, Finn moves rocks from Antrim into the sea and completes his new pathway only to find that Benandonner is, in fact, much larger than he. Instantly regretting his trash talk, McCool hightails it back to Ireland.

Once home, Finn turns to his wife Oonagh who saves the day and Finn's life. Wrapping her husband in a sheet and telling him to settle himself into the baby's crib, she welcomes Benandonner to her door, apologizing that Finn is currently hunting deer in Co. Kerry.

Once home, Finn turns to his wife Oonagh who saves the day and Finn's life. Wrapping her husband in a sheet and telling him to settle himself into the baby's crib, she welcomes Benandonner to her door, apologizing that Finn is currently hunting deer in Co. Kerry.Cleverly, Oonagh asks if he would like to see the baby and the Scot is astounded and terrified when he meets their "son" who is, in fact, Finn wrapped up in a sheet. Assuming Finn is enormous if this is his child, Benandonner makes his excuses to Oonagh and flees back across the Causeway, destroying it in his wake. You can keep your geology, I'll take a good story any day.

Published on November 17, 2018 05:55

November 16, 2018

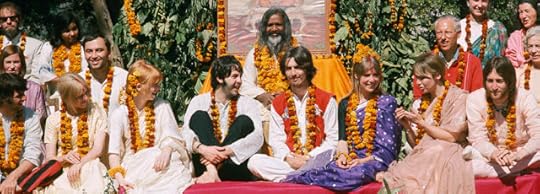

But Really, It's About Satan - "Stairway to Heaven"

Despite its Celtic feel, "Stairway to Heaven" opens with clearly modern imagery: a rich, specifically nondescript woman who places her wealth above all else, whether knowingly or through her naivete (and despite her surety). She's there on Rodeo Drive or in Palm Beach and well aware that if the stores are closed she will still get her way. Plant, when in the mood, acknowledges the simplicity of the first verse: "It was some cynical aside about a woman getting everything she wanted all the time without giving any thought or consideration. That first line begins with that cynical sweep of the hand …and it softened up after that," though in a later interview, Plant is less nebulous and fairly clear that "Stairway to Heaven" has no actual meaning. Plant said, "Depending on what day it is, I still interpret the song a different way - and I wrote it."

Despite its Celtic feel, "Stairway to Heaven" opens with clearly modern imagery: a rich, specifically nondescript woman who places her wealth above all else, whether knowingly or through her naivete (and despite her surety). She's there on Rodeo Drive or in Palm Beach and well aware that if the stores are closed she will still get her way. Plant, when in the mood, acknowledges the simplicity of the first verse: "It was some cynical aside about a woman getting everything she wanted all the time without giving any thought or consideration. That first line begins with that cynical sweep of the hand …and it softened up after that," though in a later interview, Plant is less nebulous and fairly clear that "Stairway to Heaven" has no actual meaning. Plant said, "Depending on what day it is, I still interpret the song a different way - and I wrote it." In the 2nd verse, there are signs, literally, that she may be wrong. The lady encounters confusion regarding her entry into Heaven. The "sign on the wall" is useless in that words have two meanings. "It makes me wonder" is sung here for the first time, suggesting the quandary we all face about making the right decisions.

The next verse addresses mortality and questions why things happen, how one may feel toward the end of life, ready to move on to the next stage in the spiritual world, but still immersed in the physical. Thornton Wilder's Our Town comes to mind. The speaker whose "Spirit is crying for leaving" may be facing a difficult or painful death, or simply fear the unknown; worse, fear the finality.

It makes me wonder.

The forth verse introduces the piper, who we all pay, and brings to mind Robert Browning's, "The Pied Piper of Hamelin," wherein the piper is hired to rid the town of rats by playing his magical pipe. When the town refuses pay, he uses his pipe to lead the children from town, presumably to their death. The legend certainly has an ominous ending, but the piper in "Stairway" hardly seems vindictive. Here the piper will "lead us to reason." The sentiment is furthered in the following verse, the spring clean for the May Queen. The lady's lesson is clear, "There's still time to change the road you're on." But is it clear for the lady (it makes me wonder)?

Our new character, the May Queen, the Queen of Light, is the girl who leads the parade for May Day celebrations wearing a white frock and a flower crown to symbolize her purity. However, in British folklore, the tradition has a sinister twist—the May Queen was put to death once the festivities ended. Like the piper, the May Queen has an ambiguous and ominous air, but personifies that death is a part of life and ultimately, hopefully, renewal: Heaven, incarnation, an afterlife.

The Lady's head is humming. She's not sure why. The piper is calling to join him, summoning her to death. The lady is asked whether she thinks she did the right thing. Can she hear the wind blow? Does she know her where her stairway lies?

Here the tempo lifts in an anthemic charge, the drums enter, the guitar is electrified. When the vocals resume, they're intense, and the subject is no longer what the lady needs to do to get into heaven, but what we must do.

As we go through life, we accumulate baggage—all the bad things we've done, or things we failed to do by default; the "shadows taller than our souls." And they often outweigh the good. As the lady reemerges as the focus, she's passed on, presumably finding her way, a white light now guiding us all to heaven, but we must listen very hard. "To be a rock and not to roll" is the final lesson: be a rock for one's family, friends and those in need. Use one's talents for the good of all. Stand firm. The a capella final line is more a refrain than most would assume; ultimately the lady indeed buys, through her actions and not her pocketbook, "the" stairway to Heaven (not "a" stairway to Heaven). "Stairway to Heaven" is about everything and nothing, about finding the way, or losing it, about life and death and the afterlife - quite a bit more to it than the six notes allegedly lifted from "Taurus."

As we go through life, we accumulate baggage—all the bad things we've done, or things we failed to do by default; the "shadows taller than our souls." And they often outweigh the good. As the lady reemerges as the focus, she's passed on, presumably finding her way, a white light now guiding us all to heaven, but we must listen very hard. "To be a rock and not to roll" is the final lesson: be a rock for one's family, friends and those in need. Use one's talents for the good of all. Stand firm. The a capella final line is more a refrain than most would assume; ultimately the lady indeed buys, through her actions and not her pocketbook, "the" stairway to Heaven (not "a" stairway to Heaven). "Stairway to Heaven" is about everything and nothing, about finding the way, or losing it, about life and death and the afterlife - quite a bit more to it than the six notes allegedly lifted from "Taurus."Jimmy Page commented that, "The wonderful thing about 'Stairway' is the fact that just about everybody has got their own individual interpretation to it, and actually what it meant to them at their point of life. And that's what's so great about it. Over the passage of years people come to me with all manner of stories about what it meant to them at certain points of their lives. About how it's got them through some really tragic circumstances. Because it's an extremely positive song, it's such a positive energy."

"Stairway to Heaven," like "The Battle of Evermore," was written at Headley Grange. Page strummed out the chords while Robert Plant wrote the lyrics. Plant claims that while writing the song, something overcame him, causing him to write the lyrics he did. "My hand was writing out the words 'there's a lady is sure (sic) all that glitters is gold and she's buying a stairway to heaven.' I just sat there and looked at them and almost leapt out of my head."

Makes me wonder...

Published on November 16, 2018 08:51

But Really It's About Satan - "Stairway to Heaven"

Despite its Celtic feel, "Stairway to Heaven" opens with clearly modern imagery: a rich, specifically nondescript woman who places her wealth above all else, whether knowingly or through her naivete (and despite her surety). She's there on Rodeo Drive or in Palm Beach and well aware that if the stores are closed she will still get her way. Plant, when in the mood, acknowledges the simplicity of the first verse: "It was some cynical aside about a woman getting everything she wanted all the time without giving any thought or consideration. That first line begins with that cynical sweep of the hand …and it softened up after that," though in a later interview, Plant is less nebulous and fairly clear that "Stairway to Heaven" has no actual meaning. Plant said, "Depending on what day it is, I still interpret the song a different way - and I wrote it."

Despite its Celtic feel, "Stairway to Heaven" opens with clearly modern imagery: a rich, specifically nondescript woman who places her wealth above all else, whether knowingly or through her naivete (and despite her surety). She's there on Rodeo Drive or in Palm Beach and well aware that if the stores are closed she will still get her way. Plant, when in the mood, acknowledges the simplicity of the first verse: "It was some cynical aside about a woman getting everything she wanted all the time without giving any thought or consideration. That first line begins with that cynical sweep of the hand …and it softened up after that," though in a later interview, Plant is less nebulous and fairly clear that "Stairway to Heaven" has no actual meaning. Plant said, "Depending on what day it is, I still interpret the song a different way - and I wrote it." In the 2nd verse, there are signs, literally, that she may be wrong. The lady encounters confusion regarding her entry into Heaven. The "sign on the wall" is useless in that words have two meanings. "It makes me wonder" is sung here for the first time, suggesting the quandary we all face about making the right decisions.

The next verse addresses mortality and questions why things happen, how one may feel toward the end of life, ready to move on to the next stage in the spiritual world, but still immersed in the physical. Thornton Wilder's Our Town comes to mind. The speaker whose "Spirit is crying for leaving" may be facing a difficult or painful death, or simply fear the unknown; worse, fear the finality.

It makes me wonder.

The forth verse introduces the piper, who we all pay, and brings to mind Robert Browning's, "The Pied Piper of Hamelin," wherein the piper is hired to rid the town of rats by playing his magical pipe. When the town refuses pay, he uses his pipe to lead the children from town, presumably to their death. The legend certainly has an ominous ending, but the piper in "Stairway" hardly seems vindictive. Here the piper will "lead us to reason." The sentiment is furthered in the following verse, the spring clean for the May Queen. The lady's lesson is clear, "There's still time to change the road you're on." But is it clear for the lady (it makes me wonder)?

Our new character, the May Queen, the Queen of Light, is the girl who leads the parade for May Day celebrations wearing a white frock and a flower crown to symbolize her purity. However, in British folklore, the tradition has a sinister twist—the May Queen was put to death once the festivities ended. Like the piper, the May Queen has an ambiguous and ominous air, but personifies that death is a part of life and ultimately, hopefully, renewal: Heaven, incarnation, an afterlife.

The Lady's head is humming. She's not sure why. The piper is calling to join him, summoning her to death. The lady is asked whether she thinks she did the right thing. Can she hear the wind blow? Does she know her where her stairway lies?

Here the tempo lifts in an anthemic charge, the drums enter, the guitar is electrified. When the vocals resume, they're intense, and the subject is no longer what the lady needs to do to get into heaven, but what we must do.

As we go through life, we accumulate baggage—all the bad things we've done, or things we failed to do by default; the "shadows taller than our souls." And they often outweigh the good. As the lady reemerges as the focus, she's passed on, presumably finding her way, a white light now guiding us all to heaven, but we must listen very hard. "To be a rock and not to roll" is the final lesson: be a rock for one's family, friends and those in need. Use one's talents for the good of all. Stand firm. The a capella final line is more a refrain than most would assume; ultimately the lady indeed buys, through her actions and not her pocketbook, "the" stairway to Heaven (not "a" stairway to Heaven). "Stairway to Heaven" is about everything and nothing, about finding the way, or losing it, about life and death and the afterlife - quite a bit more to it than the six notes allegedly lifted from "Taurus."

As we go through life, we accumulate baggage—all the bad things we've done, or things we failed to do by default; the "shadows taller than our souls." And they often outweigh the good. As the lady reemerges as the focus, she's passed on, presumably finding her way, a white light now guiding us all to heaven, but we must listen very hard. "To be a rock and not to roll" is the final lesson: be a rock for one's family, friends and those in need. Use one's talents for the good of all. Stand firm. The a capella final line is more a refrain than most would assume; ultimately the lady indeed buys, through her actions and not her pocketbook, "the" stairway to Heaven (not "a" stairway to Heaven). "Stairway to Heaven" is about everything and nothing, about finding the way, or losing it, about life and death and the afterlife - quite a bit more to it than the six notes allegedly lifted from "Taurus."Jimmy Page commented that, "The wonderful thing about 'Stairway' is the fact that just about everybody has got their own individual interpretation to it, and actually what it meant to them at their point of life. And that's what's so great about it. Over the passage of years people come to me with all manner of stories about what it meant to them at certain points of their lives. About how it's got them through some really tragic circumstances. Because it's an extremely positive song, it's such a positive energy."

"Stairway to Heaven," like "The Battle of Evermore," was written at Headley Grange. Page strummed out the chords while Robert Plant wrote the lyrics. Plant claims that while writing the song, something overcame him, causing him to write the lyrics he did. "My hand was writing out the words 'there's a lady is sure (sic) all that glitters is gold and she's buying a stairway to heaven.' I just sat there and looked at them and almost leapt out of my head."

Makes me wonder...

Published on November 16, 2018 08:51

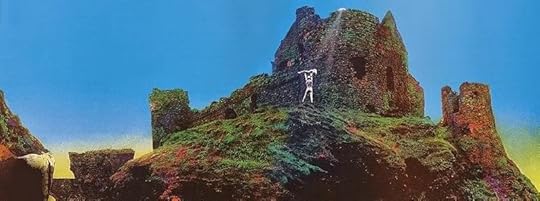

Childhood's End

Houses of the Holy

(AM9)Artist: Led ZeppelinProduced by: Jimmy PageReleased: March 28, 1973Length: 40:58Tracks: 1) The Song Remains the Same (5:32); 2) The Rain Song (7:39); 3) Over the Hills and Far Away (4:50); 4) The Crunge (3:17); 5) Dancing Days (3:53) 6) D’yer Mak’er (4:23); 7) No Quarter (7:00); 8) The Ocean (4:31); Players: Jimmy Page – lead guitar, acoustic guitar, 12 string, pedal steel, theramin; Robert Plant – vocals; John Paul Jones – bass, keyboards, synthesizer bass, backing vocals; John Bonham – drums, backing vocals

Houses of the Holy

(AM9)Artist: Led ZeppelinProduced by: Jimmy PageReleased: March 28, 1973Length: 40:58Tracks: 1) The Song Remains the Same (5:32); 2) The Rain Song (7:39); 3) Over the Hills and Far Away (4:50); 4) The Crunge (3:17); 5) Dancing Days (3:53) 6) D’yer Mak’er (4:23); 7) No Quarter (7:00); 8) The Ocean (4:31); Players: Jimmy Page – lead guitar, acoustic guitar, 12 string, pedal steel, theramin; Robert Plant – vocals; John Paul Jones – bass, keyboards, synthesizer bass, backing vocals; John Bonham – drums, backing vocals

Again, like Wish You Were Here and Joni Mitchell's Court and Spark, a follow-up to Led Zeppelin IV (ZOSO, Runes) was daunting, but although Houses of the Holy didn’t attain the lofty commercial success of its predecessor, a mature genius is scattered throughout to make it an arguably more fascinating and equally diverse listening experience. Led Zeppelin strove, generally successfully, to develop and advance their sound by consistently incorporating new ideas, from reggae (the often maligned, in particular by John Paul Jones, "D'yer Mak'er") to the James Brown inspired funk (the bottom heavy and tricky time signature of "The Crunge"). Jimmy Page's tough stomping lick, which opens "The Ocean," remains one of his finest, and the John Paul Jones showcase "No Quarter" with its dreamy, spooky piano and loud/soft dynamics was a concert showcase and one of the band’s most sublime moments. Adding strings to bring new textures to the acoustic "The Rain Song," at nearly eight minutes the disc's longest and most complex track, served to create what may be the most beautiful song in rock music (bar "God Only Knows"). From the Childhood’s End album cover (my all time favorite) to the sonic landscapes inured through impeccable musicianship, Houses of the Holy is Led Zeppelin's penultimate achievement. It shines often more brightly than ZOSO, but fails at times in its new direction and experimentation. ZOSO, on the other hand, is the pinnacle of who Led Zeppelin would become and carved the way for the confidence that Houses exemplified.

From the opening thrill of "The Song Remains The Same," Houses Of The Holy strikes one as the most intelligent and considered of all Led Zeppelin albums in that it doesn't always go straight for the most obvious approach, songs are allowed to unfold and breath before they take shape, indeed Houses Of The Holy is unique in the Led Zeppelin catalog in that the longest songs are the best things on the album.

Published on November 16, 2018 05:42