R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 56

October 14, 2018

The White Album Track by Track

I'm a terrible insomniac. I'll get out of bed at midnight or so and wander around the house. At times, I'm productive – I just finished a re-edit of my novel Miles From Nowhere and I'm working on the cover art – but when I'm not writing, I read or binge watch TV. I get spoiled though. Once I've seen something great, I have trouble settling into something else. I mean how good was Blade Runner 2049 and the new season of Black Mirror? And doesn't Game of Thrones make everything else pale in comparison?

I'm a terrible insomniac. I'll get out of bed at midnight or so and wander around the house. At times, I'm productive – I just finished a re-edit of my novel Miles From Nowhere and I'm working on the cover art – but when I'm not writing, I read or binge watch TV. I get spoiled though. Once I've seen something great, I have trouble settling into something else. I mean how good was Blade Runner 2049 and the new season of Black Mirror? And doesn't Game of Thrones make everything else pale in comparison?Long story short, I find myself moving in odd directions once 3am rolls around. I read all the Harry Potter books backward, for instance (what a different perspective it created). I've never seen all the Star Wars films in order chronologically (Prequels, Rogue 1, original trilogy, 7, 8 – so I’m working on that), but to sum up my sleep issue, I watched Breaking Bad backwards. It's the story of a Drug Lord who becomes a chemistry teacher without cancer. Doesn't have the same impact.

Paul is dead, man; miss him, miss him: Anyway, all that backward thinking reminded me of the backmasking in The Beatles' White Album. While the phenomenon began with "Rain" from the Revolver sessions (Beatles '65 in the U.S.), it's The Beatles when all the hoopla began. As "Revolution No. 9" begins you hear, over and over again, a creepy British voice saying "Number 9 .... Number 9 ... Number 9 ..." (Ringo, I think) along with screaming, crying, the sounds of a crash, and other disturbing sounds. It had to mean something, right? And then some Beatle fanatic somewhere made the stunning decision to play the song backward. In the days of record players and reel-to-reel tape, that wasn't so hard to do. The results were even more disturbing. "Number 9" backward sounds suspiciously like "Turn me on, dead man." Instantly, rumors appeared that Paul McCartney was dead. Go find better publicity than that. Check it all out on youtube if you want – if you're up like me in the middle of the night, you have plenty of time – but if you're more into the music itself, here instead is a rundown of 1968's seminal LP, The Beatles:

Side One.

Back in the USSR: The best evidence of the tension between members of the group was Ringo quitting the Beatles for about 2 weeks. Ringo was always caught in the middle, and on August 22, 1968, he walked out of the studio. In his absence, the Beatles began recording one of their finest rock songs. Basic track drums were played by Paul although they were later completed by John and George while Paul played other instruments. The song was by Paul, written while in Rishikesh with Mike Love of The Beach Boys who commented that The Beach Boys sound, Particularly "Surfin' USA" was owed to Chuck Berry. The end result fused the incredible backing vocals by George and John, in a pure Beach Boys style, a first class lead guitar line and Paul's thrilling vocal, all introduced with jet plane sound effects!

Dear Prudence: Prudence Farrow, sister of actress Mia Farrow, was in India with all four Beatles following the same course. However, Prudence seemingly took it more seriously than anyone else and tried to meditate more and better "trying to reach God quicker" as John later explained. The song was a bit of coaxing on John’s part for Prudence to maybe lighten up a bit.

Glass Onion: John would wax historical on God a few years later, but the introspective Beatle on Glass Onion took his oftentimes cryptic lyrics and explained them away. In the track he referred to as many previous Beatles songs as he could to make it even more difficult than before to understand the connection between them. The reference to Paul being the walrus indeed added to the blossoming McCartney death hoax.

Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da: One of those songs you ended up singing to your kids, the “life goes on” idea is Paul’s attempt to produce a reggae song. I doubt that it works as a reggae song, but remains Beatle fun.

Wild Honey Pie: An impromptu jam in the ashram led to Paul writing and recording the track on his own by overdubbing a bass drum, his vocals and several acoustic guitars. Paul said that it was a "fragment of an instrumental we weren't sure about. But Pattie Harrison liked it very much, so we decided to leave it on the album"

The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill: Bungalow Bill was really Richard A. Cooke III, a young college graduate from U.S.A who was visiting his mother in Rishikesh. Nancy Cooke was in India following the same course as the Beatles, and one day they both went tiger hunting. Richard did indeed shoot a tiger, and he happened to tell the Maharishi in front of John and Paul. Of course, John didn't like the story a bit (he had indeed shot the animal hidden in a tree in a wooden platform) and the song came along. The name Bungalow Bill was an amalgamation of "Buffalo Bill" and the bungalows in which they lived in India. Despite its political bent, the recording of the song was seemingly a lot of fun, as almost everyone at the studio joined in for the chorus.

While My Guitar Gently Weeps: George got the idea for the track from the "I Ching" (Chinese book of changes) and decided to write a song with the first line he got out of a book. The line was "gently weeps". The song demonstrates that George had already grown considerably as a composer. Take one of the sessions was a magical acoustic version of the song, yet it was difficult for Harrison to achieve the same magic with more instruments. For the first time, The Beatles brought in an 8-track machine to record a song in Abbey Road, but George wasn’t satisfied. He attempted some backward riffs ala Revolver, but on day two of the recording, while sharing a cab with Eric Clapton, George convinced Eric to play with The Beatles. Clapton initially refused, stating that “no one plays with The Beatles," but George's insistence and the ready availability of his Gibson Les Paul was too big a temptation for Clapton.

Happiness is a Warm Gun: John saw on the cover of a magazine belonging to George Martin the phrase "Happiness is a Warm Gun In Your Hand". Obviously, a song followed. It was a part of Paul’s bent to piece little songs into bigger ones (Uncle Albert and Band on the Run exemplified the trait in later years), but here it was all John. The three distinct parts and the lyrics came out of Lennon’s tripping one night with Derek Taylor, Neill Aspinall and Pete Shoton. Out of this acid brainstorming came the remarkable closer for Side One.

Side Two:

Martha My Dear: Recorded in its entirety by Paul with Martin adding the impeccable scoring at a later date, the track, despite the rumors, was not about Paul's sheepdog Martha. Only the name itself belongs to the shaggy canine. A bit of fun vaudeville along the lines of "When I'm 64."

I'm So Tired: John began to feel so tired while in India. Meditating didn't take that much of an effort, but it sure led to sleepless nights that left as a result, tiring days. The Academy of Meditation was also alcohol and drug-free. John missed both drinks and cigarettes. The song was recorded from beginning to end the same night as Bungalow Bill, adding a bit of realism to the mix. The line muttered at the end of the song by John is "Monsieur, monsieur, how about another one?” which leads straight into -

Blackbird: Simply a blackbird Paul had heard in India, he simply transcribed what the blackbird sang into music. An incredible acoustic track and simply beautiful, just Paul, an acoustic guitar, the ticking of a metronome and some blackbirds. Perfect.

Piggies: Quite in the line of Taxman, George used the Piggies to express his ideas, with piggies as the middle classes. All four Beatles were in the session, though John only participated by putting together some pig sounds in the control room. Remarkable is the baroque feeling of the song with the harpsichord skillfully played by the producer of the session, Chris Thomas, and the string section. Paul's plucking of the bass strings was meant to mimic a pig’s grunting.

Rocky Raccoon: Rocky Raccoon is another example of a wonderful acoustic song written by the Beatles during the India period. In fact, Paul recalled that when he wrote the song he was "sitting on the roof at the Maharishi's". He first got the chords, to later co-write the lyrics with John and Donovan of what was then "Rocky Sasoon." They later decided that Raccoon was a better last name for a Cowboy living in Dakota. It is said that the doctor "sminking" of gin (Paul’s flub of the lyrics), was a real-life character. When Paul chipped his tooth and cut his lip, the doctor that assisted him smank of gin, and that was why Paul's lip was a bit nasty looking in subsequent photos (all of it adding to the Paul is Dead substitution hoax).

Don't Pass Me By: Ringo’s first recorded song has a marked country feeling, much like Ringo's tastes. The final touches to the tune were a sleigh-bell and a fiddle played by a session musician (and not by George Harrison as it has sometimes been written).

Why Don't We Do It In The Road?: AM covered this track as a repetition piece in a series on rock lyrics as poetry. McCartney recorded most of the track on his own with Ringo on drums. Paul's vocals never sounded so Lennon-like).

I Will: Another example of Paul's talent to produce mythical tunes with just an acoustic guitar. Just two acoustic guitars played by Paul, Maracas and Cymbals by Ringo, and John hitting a piece of wood are all the instruments "I Will" needed. Paul’s bass line, the perfect counterpoint to the melody, is actually another layer of the vocals! "I Will" was the first song Paul dedicated to Linda.

Julia: If Paul had shown how exquisite he could be with an acoustic guitar, John was to prove at the end of Side Two that along with his rockers, he was able to write the most intimate, simple and beautiful song dedicated to his mother. At the age of 5 John went to live with his aunt Mimi, and although they were quite distant for years, just as John was becoming an adult, they began to get closer again. John used to do rehearsals with the Quarry Men in her house, and Julia taught him how to play banjo and piano. In 1958 Julia died in a road accident.

- The graphics are from the collection of Rutherford Chang

Published on October 14, 2018 04:34

October 13, 2018

The Beatles

Fifty years ago today, the Beatles wrapped up the recording of The Beatles, known colloquially as The White Album, the first album released on the fledgling Apple label. The two-disk set was a potpourri of cleverness, masterful individual songwriting ("Dear Prudence," "Blackbird," "Mother Nature’s Son") humor ("Rocky Raccoon," "Happiness is a Warm Gun"), social satire ("Piggies," "Revolution") rock 'n' roll ("Helter Skelter," "Back in the USSR"), throwaway fun ("The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill," "Why Don't We Do It In the Road?") and but one difficult to listen to ("Revolution #9"); it was 30 songs worth of pure listening pleasure. Rolling Stone ranked The White Album number 10 among all rock albums ever (the Beatles merely filling up five spots in the top ten). This is all the more amazing considering that Paul McCartney called it "the tension album."

Fifty years ago today, the Beatles wrapped up the recording of The Beatles, known colloquially as The White Album, the first album released on the fledgling Apple label. The two-disk set was a potpourri of cleverness, masterful individual songwriting ("Dear Prudence," "Blackbird," "Mother Nature’s Son") humor ("Rocky Raccoon," "Happiness is a Warm Gun"), social satire ("Piggies," "Revolution") rock 'n' roll ("Helter Skelter," "Back in the USSR"), throwaway fun ("The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill," "Why Don't We Do It In the Road?") and but one difficult to listen to ("Revolution #9"); it was 30 songs worth of pure listening pleasure. Rolling Stone ranked The White Album number 10 among all rock albums ever (the Beatles merely filling up five spots in the top ten). This is all the more amazing considering that Paul McCartney called it "the tension album." In February 1968, the Beatles traveled with their wives or girlfriends to Rishikesh, India, to learn Transcendental Meditation from the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The details of their growing disillusionment with the Maharishi are unimportant here. (The song, "Sexy Sadie," says it all.) The fact is, they were back in Abbey Road Studios by May. On the one hand, John, Paul and George had written a ton of songs during those hot, lazy Indian days and nights, interestingly free from the influence of drugs and alcohol. On the other hand, something had drastically changed in the individual Beatles' demeanors. Geoff Emerick, the recording engineer at Abbey Road, described the change in his book about recording The Beatles, Here, There and Everywhere:

In February 1968, the Beatles traveled with their wives or girlfriends to Rishikesh, India, to learn Transcendental Meditation from the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The details of their growing disillusionment with the Maharishi are unimportant here. (The song, "Sexy Sadie," says it all.) The fact is, they were back in Abbey Road Studios by May. On the one hand, John, Paul and George had written a ton of songs during those hot, lazy Indian days and nights, interestingly free from the influence of drugs and alcohol. On the other hand, something had drastically changed in the individual Beatles' demeanors. Geoff Emerick, the recording engineer at Abbey Road, described the change in his book about recording The Beatles, Here, There and Everywhere:They had come back from their trip to India completely different people. They had once been fastidious and fashionable; now they were unkempt. The had once been witty and full of humor; now they were solemn and prickly. They had once bonded together as life-long friends; now they resented each other’s company.

To make matters worse, there was be a fifth entity roaming about who didn't have, uh, much musical experience. We'll skip the details of John Lennon's romantic entanglements, but during the recording of The White Album, Yoko Ono not only accompanied John in the studio, but followed him wherever he went. Emerick: "If [John] went to the toilet, she'd walk him down the hall and wait outside, hunched down on the floor." The Beatles' producer, George Martin, remarked to Emerick, "What on earth is John thinking?"

But it was the effect on the other Beatles that mattered most.

But it was the effect on the other Beatles that mattered most. Emerick: You could tell from the icy chill and the looks on the faces of Paul, George and Ringo that they didn’t like it one bit. Their ranks had always been closed, and it was unthinkable that an outsider could penetrate their inner circle so quickly and so thoroughly.There was one “outsider,” however, who would be most welcome. In fact, one could speculate that his presence at Abbey Road at least temporarily salved the festering wounds of India and perhaps made the four realize that there was a part of a larger musical community. (indeed, the Beatles were the ones leading it.)

On Friday, September 6, 1968, Cream guitarist Eric Clapton stepped into Studio Two at Abbey Road to play lead guitar on George Harrison's new song, "While My Guitar Gently Weeps." It almost didn’t happen. In a car together from their homes in Surrey to the London studio, George asked his good friend to help out. According to Mark Lewisohn, Clapton exclaimed, "No one plays on Beatles sessions!" George answered, "So what? It's my song."Eric Clapton’s powerful performance on his Les Paul guitar made the song one of the many memorable moments of The White Album. And, according to George Harrison, there was the intangible benefit: It made them all try a bit harder. They were all on their best behavior.

Brilliance had indeed overcome adversity…with a little help from a friend.

Published on October 13, 2018 11:36

October 12, 2018

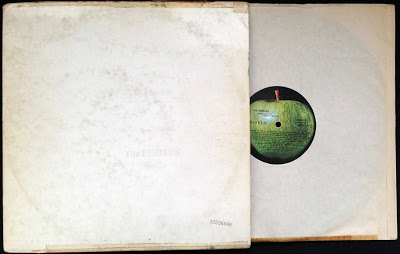

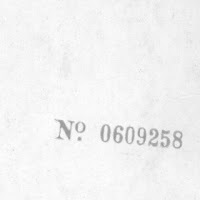

The Beatles - No. 0000etc.

I have a relatively low-numbered American Apple release of the Beatles' self-titled album, nick-named the White Album due to its iconic all-white sleeve. The double LP is, of course, a monumental rock LP and one of the best-loved albums of all time. But what about your copy? Valuable? Of course; it's nearly 80 minutes of The Beatles – but cash? Depends.

I have a relatively low-numbered American Apple release of the Beatles' self-titled album, nick-named the White Album due to its iconic all-white sleeve. The double LP is, of course, a monumental rock LP and one of the best-loved albums of all time. But what about your copy? Valuable? Of course; it's nearly 80 minutes of The Beatles – but cash? Depends.Examine the sleeve. The sleeve for the original U.K. only pressings of the White Album is a gatefold with the openings on top of the sleeve, not on the sides (called "Open Top"). Later pressings have the openings on the sides (the American, Capitol manufactured release has the outlets on the sides). The Open Top flaps were on the inside of the gatefold. The text "The Beatles" is embossed, not printed, on the front cover; this holds true for both versions. The sleeve has a number stamped in the lower right quadrant. Generally speaking, copies with lower numbers are more valuable. If the number is absent, it's a reissue.

Take both disks out of the sleeve and examine the labels. The original pressing of the LP uses the original Apple Records logo. The outside of a green apple on the A side of each disk and an apple cut in half on the B side. The Apple Records label for the original pressing should also have the Capitol Records logo on the outside edge of the b-side label. Other labels indicate later or foreign pressings.

Find the catalog number on the right-hand side of the label. The catalog number for the first U.K. pressing is PMC 7067/8 for the mono edition and PCS 7067/8 for stereo, with all black inner sleeves. The first American pressing has the catalog number SWBO 101. The record was not released in mono in the United States. The inner sleeves of the American release are white.

Find the catalog number on the right-hand side of the label. The catalog number for the first U.K. pressing is PMC 7067/8 for the mono edition and PCS 7067/8 for stereo, with all black inner sleeves. The first American pressing has the catalog number SWBO 101. The record was not released in mono in the United States. The inner sleeves of the American release are white.The mystery is just how many copies were printed of each number. Nobody seems to have a definitive answer to this question. The first two million copies of the LP (approx.) had an edition number that was not necessarily unique. Copies were numbered utilizing the same system used at all 12 pressing plants (so there are 12 No. 1s, 12 No. 2s, etc. - maybe). Also, due to a dispute over banding (where the space between songs is visible on the record disc), some copies are banded and some are not – even between copies pressed at the same plant. The consensus is that those LPs printed in the U.K. were numbered and had "No." as a prefix, while American pressings eliminated the "No." but added an "A." Lennon got copy No. 0000001 "because he shouted the loudest," at least according to Paul.

Any Guesses What This is Worth?The music publisher's name for George's and Ringo's songs was printed "Apple Publishing Ltd." on the first printing and was changed afterward to "Harrisongs Ltd." and "Startling Mus." The albums design and art direction are officially credited to Richard Hamilton, Gordon House and Jeremy Banks, with photography by John Kelly. Paul asked Hamilton to create something that directly contrasted the flamboyancy of Pepper.

Any Guesses What This is Worth?The music publisher's name for George's and Ringo's songs was printed "Apple Publishing Ltd." on the first printing and was changed afterward to "Harrisongs Ltd." and "Startling Mus." The albums design and art direction are officially credited to Richard Hamilton, Gordon House and Jeremy Banks, with photography by John Kelly. Paul asked Hamilton to create something that directly contrasted the flamboyancy of Pepper.While AM has tried to simplify the releases, the numerous presses, as well as versions made and released in countries other than the U.K. and the U.S., make it impossible to provide a definitive clarification. With this kind of mystery involved, it's no wonder that a version marked as No. 0000001, initially owned by John and then Ringo, sold at auction in 2016 for more than $60,000. Your copy? A U.S. release numbered in the millions, $15 - $30. As with all LPs, condition of the cover and vinyl is essential, but any White Album in any condition is worth $5.00 easy - probably $10.

Published on October 12, 2018 05:55

October 5, 2018

50 Years Ago

1968. I was 7. Based on the dysfunction of my family (please read Jay and the Americans on Kindle Unlimited for free! – oh, and leave a review on Amazon), my 7th B-Day was overlooked. We were supposed to take the bus to see Dr. Doolittle in Hollywood; instead, my grandmother gave me an LP, Anthony Newley Sings the Songs From Dr. Doolittle and my mother made excuses. Funny, Newley's odd vibrato and phrasing (which I would mimic to my mother's chagrin), would be the basis for my love for Bowie, who I am positive also took a cue from Newley. (I digress, but I guess even 50 years later I still harbor resentment, it seems.)

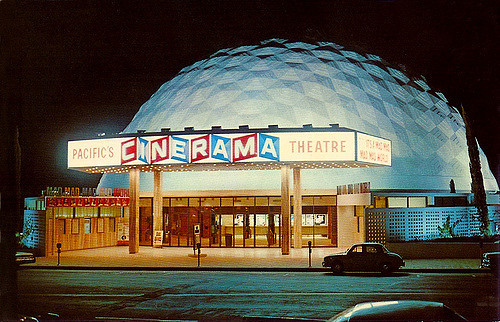

1968. I was 7. Based on the dysfunction of my family (please read Jay and the Americans on Kindle Unlimited for free! – oh, and leave a review on Amazon), my 7th B-Day was overlooked. We were supposed to take the bus to see Dr. Doolittle in Hollywood; instead, my grandmother gave me an LP, Anthony Newley Sings the Songs From Dr. Doolittle and my mother made excuses. Funny, Newley's odd vibrato and phrasing (which I would mimic to my mother's chagrin), would be the basis for my love for Bowie, who I am positive also took a cue from Newley. (I digress, but I guess even 50 years later I still harbor resentment, it seems.) My estranged father got me nothing, but then, months later during one of my parents' relentless eight-day reconciliations, he took me to the Cinerama Dome to see 2001. The tickets were $6. Cinerama was an early IMAX-like format in specialized theaters. Its screens were taller and considerably wider than normal. 2001 was filmed in Super Panavision with an exclusive surround sound. He got me the souvenir program that mimicked the widescreen format. I'd only learned about it because, when they were together, we always ate at the Howard Johnson's on Sundays; my father enjoyed the all you can eat fried clam strips. The children's menu this go-round was the 2001 edition.

My estranged father got me nothing, but then, months later during one of my parents' relentless eight-day reconciliations, he took me to the Cinerama Dome to see 2001. The tickets were $6. Cinerama was an early IMAX-like format in specialized theaters. Its screens were taller and considerably wider than normal. 2001 was filmed in Super Panavision with an exclusive surround sound. He got me the souvenir program that mimicked the widescreen format. I'd only learned about it because, when they were together, we always ate at the Howard Johnson's on Sundays; my father enjoyed the all you can eat fried clam strips. The children's menu this go-round was the 2001 edition.Before then, science fiction cinema was largely limited to B-Movies and the occasional sci-fi epic like This Island Earth or the spectacular Forbidden Planet, a spacy version of Shakespeare's The Tempest. Those early science fiction features were big hits; still, science fiction was for kids. Then came Kubrick, Clarke and 2001.

The Cinerama Dome was like a spaceship; the theater drenched in gold, the screen wrapping 180⁰. It couldn't have been a better day. (Screw Dr. Doolittle.) The theater went dark, the gold velvet screen still closed, and the strains of Ligeti’s Atmospheres slowly built. The curtain opened and then, the most dramatic opening sequence in film, "Also Sprach Zarathustra" in the background, and I could have wet myself. I'm sure for the first 25 minutes or so, you know, the monkey thing, my father had Rock Hudson's impression, only buying in with Dr. Heywood Floyd’s arrival on the space station. By intermission, my father, too, was hooked. He gasped as the curtains closed and said, "HAL was reading their lips." I was 7; I don’t know that I really got the connection.

I had no idea what I was seeing but knew it was very different. No ray guns or bug-eyed monsters? It was a strange new world by the time people built spaceships—apes became people and we conquered the environment with the aid of a big black box, but at what cost? And by intermission, the machinery people built to conquer that environment was ready to fight back! Woah, that's a lot for a 7-year old to process! As a child who grew up with Gemini missions and space walks (I had a poster of Ed White on my wall), 2001 was up there with Tomorrowland. 2001 has been a part of my life now, for 50 years; though I now watch it snuggled up on the couch in Blu Ray, and with the advent of the internet's secrets, I'll occasionally sync up Pink Floyd's Echoes and the Star Gate sequence; high, of course.

I had no idea what I was seeing but knew it was very different. No ray guns or bug-eyed monsters? It was a strange new world by the time people built spaceships—apes became people and we conquered the environment with the aid of a big black box, but at what cost? And by intermission, the machinery people built to conquer that environment was ready to fight back! Woah, that's a lot for a 7-year old to process! As a child who grew up with Gemini missions and space walks (I had a poster of Ed White on my wall), 2001 was up there with Tomorrowland. 2001 has been a part of my life now, for 50 years; though I now watch it snuggled up on the couch in Blu Ray, and with the advent of the internet's secrets, I'll occasionally sync up Pink Floyd's Echoes and the Star Gate sequence; high, of course.We all know that when you cue up The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon (1973) and play them together? You get something magical. Or, to be more precise, you get Dark Side of the Rainbow. One could believe that Floyd wrote Dark Side as a stealth Wizard of Oz soundtrack - something the band firmly denies. But bury one rumor, and another emerges. Two years before producing Meddle, featuring the 23-minute 'Echoes,' Pink Floyd worked on the More film soundtrack, utilizing film synchronization equipment. From there the rumors blossomed, with Roger Waters being misquoted as saying the band was offered the opportunity to provide the soundtrack (they had, in fact, turned down an offer to feature the "Atom Heart Mother" suite in Kubrick's Clockwork Orange). Whether or not the rumors have validity, there is an undeniable beauty when watching the combination of Kubrick's intricate multiverse coupled with the spacey psychedelia of Pink Floyd. The mashup is vibrant and unified. The emotional tone of the music and the images work in harmony; the movie and the music feed into and expand the sense of mystery and unknowability that each explores independently. Go ahead, you know you want to.

Published on October 05, 2018 05:45

October 4, 2018

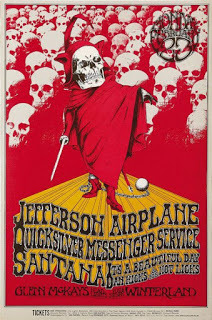

The Airplane Takes Off - The Space Time Mother Fucking Continuum

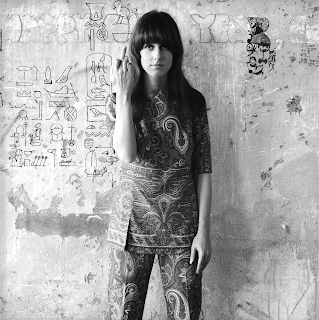

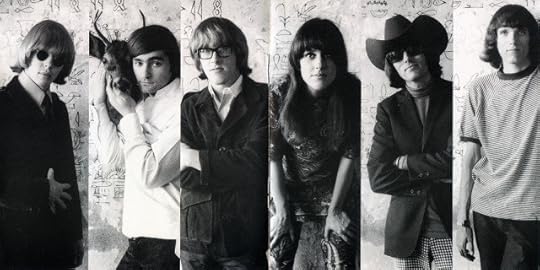

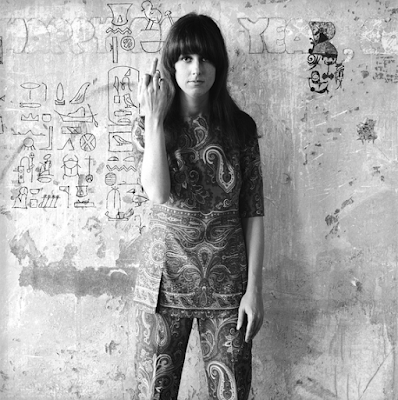

With Signe AndersonPaul Kantner was introduced to marijuana around 1959 by Jorma Kaukonen as students at Santa Clara University. A year older than Kantner, Kaukonen was an accomplished guitarist. Kantner, inspired by Kaukonen (and maybe weed) picked up the guitar and began performing in folk clubs. At a club called The Offstage, Kantner and some folkies set up the Folklore Center, "selling guitar picks, strings and marijuana." He also started booking acts for the club, including Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions (with future members of the Grateful Dead) and David Crosby. JFK's assassination in 1963 "proved the linchpin point of our generation," said Kantner, and "almost switched the universe – What R. Crumb calls the Space-Time Motherfucking Continuum – over 180 degrees. Everything that was before, was not after that." (AM points to "Satisfaction" and "Like a Rolling Stone" from 1965 as the “switch,” but certainly JFK was the political tipping point.) In 1964 Kantner was introduced to LSD by someone who brought it to The Offstage along with a Fender guitar and amplifier. "Went off into the cosmos," Kantner recalls. In the Spring of 1965 Bob Dylan's new album added electricity to folk and Kantner met Marty Balin at the Drinking Gourd on Union Street in San Francisco, not long before Marty opened The Matrix. The Drinking Gourd a bar and sandwich shop decorated like Pier One Imports. Bill Thompson, who would become Jefferson Airplane's manager in 1968, said, “Paul Kantner came in one night and he had a 12 string guitar and a banjo. Marty liked the way he looked, so he asked Kantner to join the band." Signe Anderson was a solo artist who performed at the Gourd. She became the Airplane's singer on Jefferson Airplane Takes Off (1966).

With Signe AndersonPaul Kantner was introduced to marijuana around 1959 by Jorma Kaukonen as students at Santa Clara University. A year older than Kantner, Kaukonen was an accomplished guitarist. Kantner, inspired by Kaukonen (and maybe weed) picked up the guitar and began performing in folk clubs. At a club called The Offstage, Kantner and some folkies set up the Folklore Center, "selling guitar picks, strings and marijuana." He also started booking acts for the club, including Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions (with future members of the Grateful Dead) and David Crosby. JFK's assassination in 1963 "proved the linchpin point of our generation," said Kantner, and "almost switched the universe – What R. Crumb calls the Space-Time Motherfucking Continuum – over 180 degrees. Everything that was before, was not after that." (AM points to "Satisfaction" and "Like a Rolling Stone" from 1965 as the “switch,” but certainly JFK was the political tipping point.) In 1964 Kantner was introduced to LSD by someone who brought it to The Offstage along with a Fender guitar and amplifier. "Went off into the cosmos," Kantner recalls. In the Spring of 1965 Bob Dylan's new album added electricity to folk and Kantner met Marty Balin at the Drinking Gourd on Union Street in San Francisco, not long before Marty opened The Matrix. The Drinking Gourd a bar and sandwich shop decorated like Pier One Imports. Bill Thompson, who would become Jefferson Airplane's manager in 1968, said, “Paul Kantner came in one night and he had a 12 string guitar and a banjo. Marty liked the way he looked, so he asked Kantner to join the band." Signe Anderson was a solo artist who performed at the Gourd. She became the Airplane's singer on Jefferson Airplane Takes Off (1966). Grace Wing was raised in an upper middle class family in San Francisco. Feeling like an oddball, she suppressed her interests in classical music and art and took up comic books and R&B, drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes (by the age of 16). She enrolled in Finch College in New York in 1957 and transferred to the University of Miami in her Sophomore year to study art. In 1961 she married Jerry Slick, a film student at San Francisco State College. The two rented a house in Potrero Hill where "we'd grow dope in the backyard, for our own entertainment," said Grace. The couple met a British chemist named Baxter in 1964 who introduced them to peyote, and they soon tried LSD as well. Grace found the Beatles early songs “childish” and prefered Bartok, Prokofiev, the musical "South Pacific," and jazz, in particular Miles Davis's "Sketches of Spain." She played guitar, provided soundtrack music for one of Jerry's films, and soon began spending time smoking pot and making music with Jerry’s guitarist brother, Darby. The three Slicks formed a band in the Summer of 1965 called "The Great Society," after LBJ's failed social program. One morning, while coming down from an acid trip, alone and depressed because his girlfriend had spend the night with another man, Darby wrote, “When the truth is found to be lies/ And all the joy within you dies/ Don't you want somebody to love?”

Grace Wing was raised in an upper middle class family in San Francisco. Feeling like an oddball, she suppressed her interests in classical music and art and took up comic books and R&B, drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes (by the age of 16). She enrolled in Finch College in New York in 1957 and transferred to the University of Miami in her Sophomore year to study art. In 1961 she married Jerry Slick, a film student at San Francisco State College. The two rented a house in Potrero Hill where "we'd grow dope in the backyard, for our own entertainment," said Grace. The couple met a British chemist named Baxter in 1964 who introduced them to peyote, and they soon tried LSD as well. Grace found the Beatles early songs “childish” and prefered Bartok, Prokofiev, the musical "South Pacific," and jazz, in particular Miles Davis's "Sketches of Spain." She played guitar, provided soundtrack music for one of Jerry's films, and soon began spending time smoking pot and making music with Jerry’s guitarist brother, Darby. The three Slicks formed a band in the Summer of 1965 called "The Great Society," after LBJ's failed social program. One morning, while coming down from an acid trip, alone and depressed because his girlfriend had spend the night with another man, Darby wrote, “When the truth is found to be lies/ And all the joy within you dies/ Don't you want somebody to love?”  Drawing on her love of Spanish songs, Grace fashioned a bolero rhythm for a new song of her own. Then, thinking back on her childhood fantasies, she suggested a correlation between the mystical worlds of those timeless tales and the quests that she and her fellow seekers were undertaking as young adults: "One pill makes you larger and one pill makes you small/ And the ones that Mother gives you don't do anything at all/ Go ask Alice, when she's ten feet tall."

Drawing on her love of Spanish songs, Grace fashioned a bolero rhythm for a new song of her own. Then, thinking back on her childhood fantasies, she suggested a correlation between the mystical worlds of those timeless tales and the quests that she and her fellow seekers were undertaking as young adults: "One pill makes you larger and one pill makes you small/ And the ones that Mother gives you don't do anything at all/ Go ask Alice, when she's ten feet tall." "What I was trying to say was that between the ages of zero and five the information and the input you get is almost indelible. In other words, once a Catholic, always a Catholic. And the parents read us these books, like Alice in Wonderland, where she gets high, tall, and she takes mushrooms, a hookah, pills, alcohol. And then there's the Wizard of Oz, where they fall into field of poppies and when they wake up they see Oz. And then there's Peter Pan, where if you sprinkle white dust on you, you could fly. And then you wonder why we do it? Well, what did you read to me?"

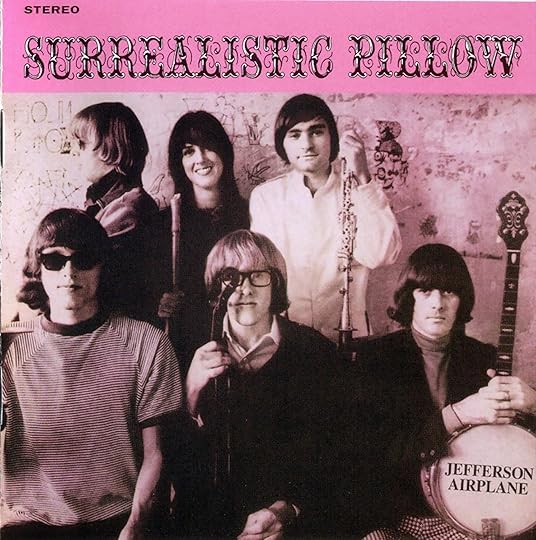

The Great Society actually recorded "Somebody to Love" and "Go Ask Alice" with Grace on vocals in November 1965, a year before the Jefferson Airplane version hit the charts. After The Great Society broke up and Slick joined the Jefferson Airplane, the band recorded Surrealistic Pillow. Marty Balin contributed his composition "Comin' Back to Me" written in one sitting after smoking some potent weed: "The summer had inhaled and held its breath too long/ The winter looked the same as if it had never gone/ And through an open window where no curtain hung I saw you,/ I saw you Comin' back to me."

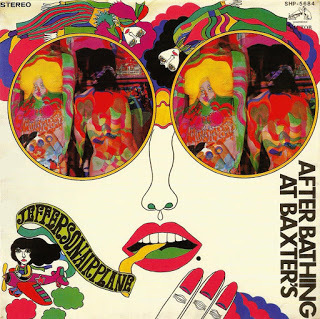

The Great Society actually recorded "Somebody to Love" and "Go Ask Alice" with Grace on vocals in November 1965, a year before the Jefferson Airplane version hit the charts. After The Great Society broke up and Slick joined the Jefferson Airplane, the band recorded Surrealistic Pillow. Marty Balin contributed his composition "Comin' Back to Me" written in one sitting after smoking some potent weed: "The summer had inhaled and held its breath too long/ The winter looked the same as if it had never gone/ And through an open window where no curtain hung I saw you,/ I saw you Comin' back to me."Another song on the Album, DCBA-25 refers to the tune's chord progression and to LSD-25. A year later, in 1967, the band graced the cover of the first issue of Rolling Stone and recorded After Bathing at Baxter's, a reference to taking LSD, for which the band's nickname was Baxter.

The Jefferson Airplane website says of Kantner: "As the '60s wore on, the Airplane became a symbol of the burgeoning counterculture, and Paul reflected this in songs such as "Crown of Creation" (1968) and "We Can Be Together" (1969). To Paul, the "Establishment" included everything from cops who unplugged the band during curfew to the band's own record company, RCA. In "We Can Be Together," he included the line, "Up against the wall, motherfucker," which launched a bitter contest of wills between the band and RCA over its inclusion; the company finally backed down. So much more than contemporaries The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane were the litmus test of mid-60's youth.

Published on October 04, 2018 04:14

October 3, 2018

Surrealistic Pillow Revisited - AM10 - i.e. I changed My Mind

Plenty will argue the validity of Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. Dark Side of the Moon, Sgt. Pepper, Pet Sounds and Led Zeppelin IV are beyond reproach, yet there’s no doubt that certain LPs don’t get a fair shake (The Cure’s Disintegration in the 300s, beat out by Sleater-Kinney's Beat Me Out? Really?). There are those who debate the top 20, but no one will doubt the arguability of each. What's interesting, though, is that what truly sets the bar is longevity. The top 20 have proven their value over time; new generations have discovered these LPs and each sounds as if it could have been released yesterday. LPs from the 60s have the distinct disadvantage that early film faces, mostly in a lack of recording quality. The Mamas and the Papas suffer based on antiquated recording techniques (or prohibitive costs) that often hamper John Philips complex arrangements. Abbey Road falters a bit in its sophomoric use of early synths (Sgt. Pepper and Revolver do not). All this in mind, Dark Side and Blood on the Tracks will be debated years to come, and by far younger critics than me.

Plenty will argue the validity of Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. Dark Side of the Moon, Sgt. Pepper, Pet Sounds and Led Zeppelin IV are beyond reproach, yet there’s no doubt that certain LPs don’t get a fair shake (The Cure’s Disintegration in the 300s, beat out by Sleater-Kinney's Beat Me Out? Really?). There are those who debate the top 20, but no one will doubt the arguability of each. What's interesting, though, is that what truly sets the bar is longevity. The top 20 have proven their value over time; new generations have discovered these LPs and each sounds as if it could have been released yesterday. LPs from the 60s have the distinct disadvantage that early film faces, mostly in a lack of recording quality. The Mamas and the Papas suffer based on antiquated recording techniques (or prohibitive costs) that often hamper John Philips complex arrangements. Abbey Road falters a bit in its sophomoric use of early synths (Sgt. Pepper and Revolver do not). All this in mind, Dark Side and Blood on the Tracks will be debated years to come, and by far younger critics than me.What's forgotten often is the impact of a recording in its time period, an oversight that AM hoped to address in its year to year reviews from a few months back. With that kind of impetus, for this writer, Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow is AM's choice for album of the decade (rated by RS as the 146th Greatest Album of all time. Indeed, not The Beatles, not Pet Sounds, not Dylan. Surrealistic Pillow, more than any other title, is the 60s). The group's hippie ethos was omnipresent, the very core of its sociomusical importance. Thus it is that the Airplane's most celebrated LP sounds a lot more dated now than many other classic records from 1967. Yet, as even a cursory listen proves, the flower children had a lot more to offer than free love and cheap acid.

Right from the heavily reverberated drums opening "She Has Funny Cars," Pillow is a powerfully expansive and entertaining experience, and its overt sense of its own time and place does nothing to weaken it. The hard-rocking "Somebody to Love" is still a rousing blend of psychedelic swagger and pop accessibility, "D.C.B.A. 25" a lovely folk-rock gem which can wring a nostalgia for the Summer of Love even from one who wasn't there. It's a pair of beautiful ballads, however - "Today" and the magnificent "Comin' Back to Me" - that are the album's highlights. Singer Marty Balin's lovely, emotive tenor has never quite gotten the credit it deserves; but his performances on these two songs make clear that it was he, rather than Grace Slick, who truly was the voice of Jefferson Airplane. Not that Slick doesn't do excellent work of her own, on flute and keyboards as well as at the mic, particularly with the aforementioned "Somebody to Love" and the LP's incredible psychedelic closer, "White Rabbit." The instrumental "Embrionic Journey" is to the 60s what "The Clap" and "Mood for a Day" were to every guitar player in the 70s, so there's another layer. Hippie or not, dated or not, you're sure to find something you like here, as people have been doing for fifty years.

Reverb and fuzz-guitar aside, even the lyrics point at Pillow's psychedelic iconicism:

Plastic Fantastic Lover

Plastic Fantastic LoverHer neon mouth with the bligitaw * smile

Is nothing but a 'lectric sign

You could say she has an individual style

She's a part of the carnival time.

Super-seal-a-ted * chrome-colored clothes

You wear 'cause you have no other

But I suppose no one knows

You're my plastic fantastic lover

Your rattlin' cough never shuts off

Is nothin' but a used machine

Your aluminum finish, slightly diminished,

Is the best I ever have seen

Cosmeta-gated *plugged into me

And never ever find another

And I realize no one's wise

To my plastic fantastic lover

The electrical dust is starting to rust

The electrical dust is starting to rustHer trapezoid thermometer taste

All the red tape is mechanical rape

Of the TV program waste

Data control and IBM

Science is mankind's brother

But all I see is drainin' me

On my plastic fantastic lover

1 Bligitaw - hit in the mouth with a sledge hammer

2- Super-seal-a-ted - a Marty Balin made up word past tense of super sealed

3 Cosmeta-gated - another made up word - combination of cosmetic and gated - gated as a plug and also logic circuit, and-gates, or-gates used in computers of the time

"Plastic Fantastic Lover" is just what it sounds like: science fiction from 1967, a futuristic precursor to Roxy Music's "In Every Dreamhome a Heartache."

Published on October 03, 2018 04:24

October 1, 2018

Repost: Surrealistic Pillow

Surrealistic Pillow

(AM9)

Surrealistic Pillow

(AM9)Artist: Jefferson Airplane

Produced by: Rick Jarrad

Released: February 1967

Length: 34:48

Tracks: 1) She Has Funny Cars (3:14); 2) Somebody to Love (3:00); 3) My Best Friend (3:04); 4) Today (3:03); 5) Comin' Back to Me (5:23) 6) 3/5 of a Mile in 10 Seconds (3:45); 7) D.C.B.A. (2:39); 8) How Do You Feel (3:34); 9) Embryonic Journey (1:55) 10) White Rabbit (2:32); 11) Plastic Fantastic Lover (2:39)

Players: Marty Balin – vocals, guitar; Jack Cassady – bass, guitars; Spencer Dryden – drums; Paul Kantner – guitar, vocals; Jorma Kaukonen– lead guitar, vocals; Grace Slick – vocals; with Jerry Garcia and Skip Spence

While the Airplane's luster has dimmed since its psychedelic heyday, more than any of their albums Surrealistic Pillow has remained fresh and crisp; here they turn the pillow over to the cool side. Not as overtly political as Volunteers or as jaggedly innovative as After Bathing At Baxter's, this album transports the listener to a particular place and time without a twinge of embarrassment at its naiveté (let's call it simplicity). The songwriting is at its most focused and the performances are free of the mannered affectations that mar later outings. Grace Slick is at her least strident, Marty Balin is at his most tender, and the rest of the band service the needs of the songs instead of their own egos while still subtly shining in their musicianship. Marty Balin's "Today" and "Comin' Back To Me" are two of the finest (and most haunting) love songs produced by any pop group in the 1960s. At the same time, the band's hardest-rocking tracks, "Plastic Fantastic Lover", "She Has Funny Cars" and "3/5 of a Mile in 10 Seconds," were penned by Balin as well. It was Grace Slick, however, who hit radio paydirt with "White Rabbit" and "Somebody To Love," which contains the most ferocious guitar solo to ever assault the Top 40. Naturally, she became the visual focus for the group, to Balin's chagrin. "Embryonic Journey" remains one of rock's stellar guitar instrumentals, standing alongside Steve Howe's "Mood For a Day." Surrealistic Pillow has a sleek, echoey Hollywood sheen due to commercial producer Rick Jarrard that, contrary to the band's expressed opinion at the time, contributes to its haunting, timeless quality. A definitive psychedelic LP.

Jerry Garcia is listed as the "Musical and Spiritual Adviser" on the LP's back cover. Hidden behind that vague credit, Garcia did quite a bit of work on Surrealistic Pillow, a couple months before the Dead even entered the studio for the first time – in fact, he spent more time on Surrealistic Pillow than he did recording The Grateful Dead. Kinda crazy since The Airplane were comparative veterans of the studio. They had more experience than the Dead, they'd gotten a record contract with RCA a year earlier, and they were already the most successful band in San Francisco, thanks in part to a stunning first album (Takes Off)from 1965. The Dead, meanwhile, had only signed with Warner Brothers in September '66 and wouldn't record till the end of the year. When asked about his pre-Dead recordings, Garcia vaguely replied, "I did some various sessions around San Francisco. Demos and stuff like that."

Jerry Garcia is listed as the "Musical and Spiritual Adviser" on the LP's back cover. Hidden behind that vague credit, Garcia did quite a bit of work on Surrealistic Pillow, a couple months before the Dead even entered the studio for the first time – in fact, he spent more time on Surrealistic Pillow than he did recording The Grateful Dead. Kinda crazy since The Airplane were comparative veterans of the studio. They had more experience than the Dead, they'd gotten a record contract with RCA a year earlier, and they were already the most successful band in San Francisco, thanks in part to a stunning first album (Takes Off)from 1965. The Dead, meanwhile, had only signed with Warner Brothers in September '66 and wouldn't record till the end of the year. When asked about his pre-Dead recordings, Garcia vaguely replied, "I did some various sessions around San Francisco. Demos and stuff like that."  In a less modest moment, Garcia was asked about Surrealistic Pillow in a mid-'67 interview: "Yeah, I played flattop on that. I didn’t play flattop in 'My Best Friend.' Skip Spence did – he wrote the song. Let's see, on 'Today' I played the high guitar line, and I played on 'Plastic Fantastic,' and I played on 'Comin' Back To Me.' I'm fond of the songs that Grace is in: I like 'Rabbit' a lot, I like 'Someone to Love' – the original on the album is more or less my arrangement, I kind of rewrote it. I've always liked the songs she used to do with The Great Society, but it didn't have - the chord changes weren't very interesting."

In a less modest moment, Garcia was asked about Surrealistic Pillow in a mid-'67 interview: "Yeah, I played flattop on that. I didn’t play flattop in 'My Best Friend.' Skip Spence did – he wrote the song. Let's see, on 'Today' I played the high guitar line, and I played on 'Plastic Fantastic,' and I played on 'Comin' Back To Me.' I'm fond of the songs that Grace is in: I like 'Rabbit' a lot, I like 'Someone to Love' – the original on the album is more or less my arrangement, I kind of rewrote it. I've always liked the songs she used to do with The Great Society, but it didn't have - the chord changes weren't very interesting." Garcia once said, "Our audience is like people who like licorice. Not everybody likes licorice, but the people who like licorice really like licorice." Seems The Jefferson Airplane really liked licorice.

Published on October 01, 2018 04:29

September 30, 2018

Jefferson Airplane

In 1965, Marty Balin, a San Francisco pop singer, courted investors to help him convert a pizzaria at 3138 Fillmore Street in San Francisco into a nightclub, later called the Matrix. While investing no money of his own, Balin held 25% of revenues. His next venture was to find competent musicians in order to form a new folk-rock outfit, essentially the club's house band. Eventually he enlisted Paul Kantner (rhythm guitarist), Jorma Kaukonen (lead singer/guitarist), Signe Toly (singer), Bob Harvey (bass) and Jerry Peloquin (drums). The new band was christened Jefferson Airplane.

In 1965, Marty Balin, a San Francisco pop singer, courted investors to help him convert a pizzaria at 3138 Fillmore Street in San Francisco into a nightclub, later called the Matrix. While investing no money of his own, Balin held 25% of revenues. His next venture was to find competent musicians in order to form a new folk-rock outfit, essentially the club's house band. Eventually he enlisted Paul Kantner (rhythm guitarist), Jorma Kaukonen (lead singer/guitarist), Signe Toly (singer), Bob Harvey (bass) and Jerry Peloquin (drums). The new band was christened Jefferson Airplane. The band made their first official appearance at the Matrix in August 1965. Folk rock was dominating the charts at the time, and it was no surprise that a fledgling band under Balin's direction received positive attention from the press. Peloquin and Harvey were fired after only a month and replaced by drummer/guitarist Skip Spence and new bassist Jack Casady. Around the same time, Toly married Jerry Anderson, one of the members of Ken Kesey's "Merry Pranksters," who managed the lighting at the Matrix. This lineup of Anderson, Casady, Balin, Kantner, Kaukonen and Spence signed their first contract with RCA Victor (the first San Francisco band to sign with a major label), and late in '65 The Jefferson Airplane had their first recording session in Los Angeles. Their debut singles (all self-composed tracks) such as "It’s No Secret," and "Bringing Me Down," failed to chart. Their debut album Jefferson Airplane Takes Off (1966) peaked at No. 128 on the Billboard 200.

J.A. at the MatrixAs the band evolved, Spence was replaced by new drummer Spencer Dryden, while Anderson, gave birth to a daughter. Anderson's commitment to raising her family caused her to leave the band. Fortunately, The Airplane found a strong replacement in Grace Slick, the lead singer of San Francisco band The Great Society, who were on the verge of splitting up.

J.A. at the MatrixAs the band evolved, Spence was replaced by new drummer Spencer Dryden, while Anderson, gave birth to a daughter. Anderson's commitment to raising her family caused her to leave the band. Fortunately, The Airplane found a strong replacement in Grace Slick, the lead singer of San Francisco band The Great Society, who were on the verge of splitting up.Grace Slick would play a prominent role from then on, and the band released their second LP Surrealistic Pillow in 1967 with both Slick and Balin taking the lead. The album began its ascent up the charts with "Somebody to Love" (penned by Slick's brother-in-law, Darby Slick) Jefferson Airplane's first top ten hit, reaching No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100. "White Rabbit," meanwhile, using references from Alice in Wonderland while examining the effects of psychedelic drugs, peaked at #8 in mid-1967. Surrealistic Pillow reached #3 on the Billboard 200. It eventually went gold.

By that time, Jefferson Airplane realized the success they'd wanted. They performed at Monterey Pop, famed for its introduction of rock legends Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. They would go on to become the only band to play all three major rock festivals, rounding out the dacade with Woodstock and finally the ill-fated Altamont Free Concert. Their exposure was further augmented by TV appearances on such shows as The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and The Ed Sullivan Show. On the heels of the success of Surrealistic Pillow, the band decided to take a change of direction, like many other psychedelic bands. They adopted a more adventurous, heavier sound, as evident in their third LP, After Bathing at Baxter’s at the end of 1967. Baxter's remains a stellar achievement from the early rock era.

By that time, Jefferson Airplane realized the success they'd wanted. They performed at Monterey Pop, famed for its introduction of rock legends Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. They would go on to become the only band to play all three major rock festivals, rounding out the dacade with Woodstock and finally the ill-fated Altamont Free Concert. Their exposure was further augmented by TV appearances on such shows as The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and The Ed Sullivan Show. On the heels of the success of Surrealistic Pillow, the band decided to take a change of direction, like many other psychedelic bands. They adopted a more adventurous, heavier sound, as evident in their third LP, After Bathing at Baxter’s at the end of 1967. Baxter's remains a stellar achievement from the early rock era.

Published on September 30, 2018 15:00

September 29, 2018

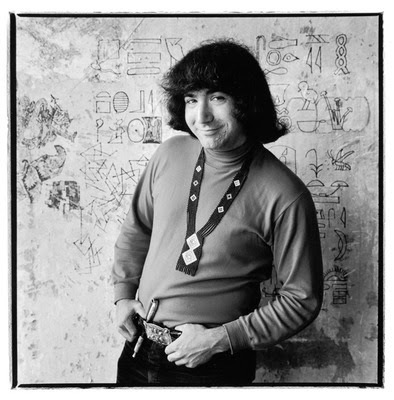

2400 Fulton Street - Calif. - A Tribute to Marty Balin

From the Marty Balin Website: "Michelangelo claimed that he did not create a sculpture. Rather, the form was contained within the block of marble; he merely removed the excess, revealing the work of art. 'I feel the same way about music, and about all the projects I’m involved in. The projects do themselves; the music comes through me.' The same vision Marty had when he launched the Jefferson Airplane is present today. In fact, nearly everything he has worked on over the years has been fueled with his vision of art and music as vehicles for expressing a positive message. 'I still have the same attitude. I still love the positive, uplifting songs, and I believe in songs with those qualities. I believe that music can help change the world for the better.'" Marty Balin died on September 27, 2018.

From the Marty Balin Website: "Michelangelo claimed that he did not create a sculpture. Rather, the form was contained within the block of marble; he merely removed the excess, revealing the work of art. 'I feel the same way about music, and about all the projects I’m involved in. The projects do themselves; the music comes through me.' The same vision Marty had when he launched the Jefferson Airplane is present today. In fact, nearly everything he has worked on over the years has been fueled with his vision of art and music as vehicles for expressing a positive message. 'I still have the same attitude. I still love the positive, uplifting songs, and I believe in songs with those qualities. I believe that music can help change the world for the better.'" Marty Balin died on September 27, 2018.The following excerpt is from Calif. R.J. Stowell's novel scheduled for publication in 2020.

1970: I stopped at a light and realized where I was. I'd come out of Golden Gate Park onto Haight Street. There were lots of groovy people, lots of long hairs and head shops and hippies sitting on the curb, and then I passed Ashbury Street and someone in an Econoline panel truck pulled out of a parking space.

I parked the V-dub and did a surprisingly good job. You didn't really parallel park in L.A., pave paradise and all, so I'd never learned. I was singing that the rest of the day. It was a new song by Joni Mitchell and that line about cutting down trees and putting them in a museum was echoing in my head. I grabbed my journal and started walking and taking notes.

A girl passed on the street. She sang, "Don't it always seem to go, you don't know what you've got till it’s gone." She kept walking, and I sang, "Paved paradise, put up a parking lot."

I got down by the park again where there were hippies loitering at 2400 Fulton Street, a big black columnated mansion with date palms out front and a wrought iron gate. It looked like the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland. I asked someone why they were all hanging out. A dude and a girl said simultaneously, almost as if they were one, "It's the Airplane House."

I got down by the park again where there were hippies loitering at 2400 Fulton Street, a big black columnated mansion with date palms out front and a wrought iron gate. It looked like the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland. I asked someone why they were all hanging out. A dude and a girl said simultaneously, almost as if they were one, "It's the Airplane House."I hedged. "Yeah, so, what's the airplane house?" I probably seemed a bit straight to them. I had on chinos, my Chucks, a t-shirt and a Hang Ten windbreaker. I guess, to be honest, and if I were to make an entry in my journal describing myself, I'd end up looking like Jimmy Olsen. In unison they said, "Jefferson Airplane, you know?" They even said "you know" together. "It's 17 rooms and three stories; they say the higher up you get, the higher you get."

I said, "I want to see them. They're playing tomorrow night."

The guy said, "You got tickets, man?" at the same time the girl said, "You better get a ticket, man." I told them I didn't even know where it was. He said, "The other end of," and she said, "the park."

The guy said, "You got tickets, man?" at the same time the girl said, "You better get a ticket, man." I told them I didn't even know where it was. He said, "The other end of," and she said, "the park."I heard someone point toward an upstairs window and say, "Jorma Kaukonen," but it was a false alarm; it was the wind and a ripple in the glass. It was interesting, this spectacle, but it was kind of odd, like this was the monkey house and the monkeys were hard to spot.

- From the upcoming novel Calif. by R.J. Stowell

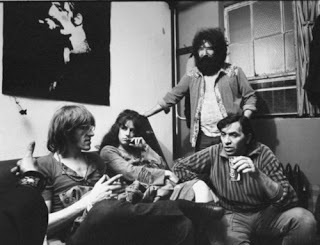

The 17-room mansion at the corner of Willard and Fulton, which lies across the street from Golden Gate Park and just over the western shoulder of Lone Mountain, was bought in May of 1968 by Jefferson Airplane. There aren't many other contenders in the Haight for places where the most LSD has probably been dropped. Called "The Airplane House," "2400 Fulton" (which would become the name of JA's greatest hits LP), or simply "The Mansion" was built in 1904 for a San Francisco lumber baron, the ornate manse became Frisco’s premier party house. Quickly the house would become a magnet for fans, musicians, groupies, dope dealers and celebrities. Part-time girlfriend to "player," Paul Kantner, Barbara Langer said, "I remember one banquet when there was a big fat joint on every plate, and a roasted suckling pig with an apple in its mouth." The Airplane’s manager, Bill Thompson had arranged the sale of the mansion for $70,000 (most recent purchase price nearly $8 million), and hired Jacky Watts to handle the many details. "Thompson sent his girlfriend Judy over to see if I was hip enough. I had a great little house, black light posters all over. I had a kitty car, I was wearing paisley. I passed the hipness test." Thompson gives Jacky all the credit for the find: “The lecherous old guy who lived there liked Jacky. It was the greatest investment we ever made."

The 17-room mansion at the corner of Willard and Fulton, which lies across the street from Golden Gate Park and just over the western shoulder of Lone Mountain, was bought in May of 1968 by Jefferson Airplane. There aren't many other contenders in the Haight for places where the most LSD has probably been dropped. Called "The Airplane House," "2400 Fulton" (which would become the name of JA's greatest hits LP), or simply "The Mansion" was built in 1904 for a San Francisco lumber baron, the ornate manse became Frisco’s premier party house. Quickly the house would become a magnet for fans, musicians, groupies, dope dealers and celebrities. Part-time girlfriend to "player," Paul Kantner, Barbara Langer said, "I remember one banquet when there was a big fat joint on every plate, and a roasted suckling pig with an apple in its mouth." The Airplane’s manager, Bill Thompson had arranged the sale of the mansion for $70,000 (most recent purchase price nearly $8 million), and hired Jacky Watts to handle the many details. "Thompson sent his girlfriend Judy over to see if I was hip enough. I had a great little house, black light posters all over. I had a kitty car, I was wearing paisley. I passed the hipness test." Thompson gives Jacky all the credit for the find: “The lecherous old guy who lived there liked Jacky. It was the greatest investment we ever made."

Published on September 29, 2018 06:02

September 28, 2018

Waits and Me - Ramblings From 3am

When I look at the gritty persona and the Bukowski stylings, I can't associate much with Tom Waits. His is a life I am both jealous and afraid of, but when he talks about the Sav-on and the heart of Saturday night, each of us finds a little wayward self. For me, it's the storytelling where we mesh. Indeed, Waits and I have told so many different stories that it's difficult to distinguish fact from fiction.

When I look at the gritty persona and the Bukowski stylings, I can't associate much with Tom Waits. His is a life I am both jealous and afraid of, but when he talks about the Sav-on and the heart of Saturday night, each of us finds a little wayward self. For me, it's the storytelling where we mesh. Indeed, Waits and I have told so many different stories that it's difficult to distinguish fact from fiction.Waits spent most of his youth in Whittier, California with his parents and two sisters. His father played Spanish guitar, his mother always singing; the house filled with music. First picking up the guitar from his father, Wait then learned piano from his neighbor. There is so much "Jay" in that (of course, a shameless plug for Jay and the Americans). My neighbor in 7th grade was a woman who taught piano and worked in a piano bar on Roscoe Blvd. in the Valley. She'd written a hit for Frank Sinatra (but still she worked late in a piano bar). She gave me free piano lessons and a key to her apartment, but I was as lazy as the day was long and her instruction never got me past Shaum's red book.

Like most of the kids, Waits had a gang of neighbor buddies and they were doing standard kid stuff - "Hanging around in the Sav-On parking lots and buying baseball cards". He mentions them and his neighborhood in "Kentucky Avenue." During one of his concerts in 1981, a wondrous performance at McCabe's, Waits mentioned those little meaningful things from his childhood like having a tree fort, his first cigarette when he was seven amd being the neighborhood mechanic and repairing everyone's bicycles. When he was ten, his parents were divorced, and he moved with his mother and sisters to Chula Vista. He was fascinated by neighboring National City, a grimy suburb of San Diego, and here is where Tom was indoctrinated into a whole new world - he started hanging out with "pool hustlers, vinyl-booted go-go dancers, traveling salesmen and assorted gangsters." He was spending whole days watching movies at the Globe, a local movie theater, or playing on an old piano (which he got from a neighbor) in his garage. Tom acquired his appreciation for the blues while he was attending an all-black junior high school. This is when he became a huge fan of Ray Charles.

So that's some romantic shit right there; I was too afraid of life for that. When he was fourteen, he worked at Napoleone's Pizza parlor. By then, music was the only thing that was important to Tom. He dropped out of school and began writing songs in earnest. Later he had a series of dead-end jobs like janitor, cook, dishwasher, cabdriver, fireman, delivery guy. Pretty much like all of us, but few of us have the opportunity to turn the mundane into genius.

Anyway, You know that kid who everyone liked and teacher thought was going to be a big star? The handsome guy who won the talent show and was popular with the ladies? Yeah, that isn’t him. Tom Waits said: "If I exorcise my demons, my angels may leave too" (from "Please Call Me, Baby"). When I wrote the character Maxwell Tennial (Max Ten), a young Waits was what I had in mind; a philosopher rogue who was popular despite himself – Tennial/Waits was who I wanted to be, my Tyler Durden, quoting Rimbaud and Hemingway. I didn’t even come close, of course, just close to people like him – I was a disciple not a guru, but Waits, too, had the disciple in him, though his gurus were Bacon and Bukowski; mine was Walt Disney instead. And the Haris on Hollywood Blvd. (read Jay and the Americans).

That in mind, "Champaign for my real friends, Real pain for my sham friends" was actually from Francis Bacon, and from Rainer Maria Rilke, who rejected psychotherapy with the words, we get, "If my devils are to leave me, I am afraid my angels will take flight as well." It’s the sign of a good storyteller, steal from others without anyone even knowing. Thanks, Tom. Thanks, Max.

Published on September 28, 2018 04:15