R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 58

September 13, 2018

The European Canon is Here

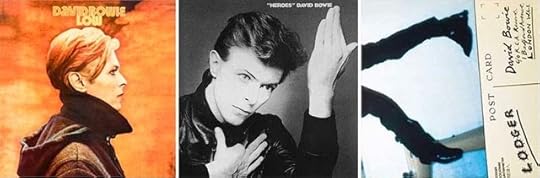

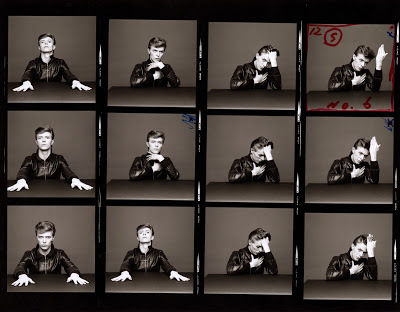

The ideology and soundscape of Bowie's Station to Station was recycled and honed for Low, for many the best album of the 70s (a bold statement indeed). The first of three albums in the Berlin Trilogy collaborations with Brian Eno, the album reflects the state of mind of its creator due primarily to drug abuse. Many of the songs reflect how depressed, lethargic and self-destructive Bowie was at the time. As an example, in "Breaking Glass," he tells a story of how his wife, Angie Bowie, appeared in Berlin with her boyfriend, Roy Martin, leading to a harsh discussion between the triad; while in "Always Crashing in the Same Car," the Thin White Duke references a motor vehicle accident he'd had in his Mercedes. Low was released in 1977, and the track "Sound and Vision" reached number 3 in the U.K. charts. With songs relatively simple, repetitive, unadorned and almost entirely instrumental on the B-side, Low was a perverse reaction to punk rock; an album decades ahead of its time.

The ideology and soundscape of Bowie's Station to Station was recycled and honed for Low, for many the best album of the 70s (a bold statement indeed). The first of three albums in the Berlin Trilogy collaborations with Brian Eno, the album reflects the state of mind of its creator due primarily to drug abuse. Many of the songs reflect how depressed, lethargic and self-destructive Bowie was at the time. As an example, in "Breaking Glass," he tells a story of how his wife, Angie Bowie, appeared in Berlin with her boyfriend, Roy Martin, leading to a harsh discussion between the triad; while in "Always Crashing in the Same Car," the Thin White Duke references a motor vehicle accident he'd had in his Mercedes. Low was released in 1977, and the track "Sound and Vision" reached number 3 in the U.K. charts. With songs relatively simple, repetitive, unadorned and almost entirely instrumental on the B-side, Low was a perverse reaction to punk rock; an album decades ahead of its time. Ten months after Low, Heroes was recorded with the same musicians (though Robert Fripp replaced Ricky Gardener on lead guitar), and again produced by Tony Visconti. The album was more user-friendly and romantic than its predecessor; the title track telling the story of two lovers who meet at the Berlin Wall, while in "V-2 Schneider," Bowie makes reference to the weaponry of Nazi Germany. Heroes is a resplendent album in its own right (if overrated), though not as structured as Low. Together the two brought to the listener the sentiment of the Cold War, symbolized by the divided city that inspired them. In 1978, the entire troupe embarked on a world tour that included songs from both albums as well as several from Ziggy, "Stay" and "Station to Station," with "TVC15" as an encore.

Released in 1979, Lodger was actually recorded in Switzerland not Berlin and was the last album of the trilogy or "Triptych" as Bowie referred to it. Lodger, a bit top heavy in its construct contained the singles "Boys Keep Swinging," "DJ" and "Look Back in Anger," and unlike the previous LPs, did not have instrumental tracks or ambient soundscapes. Though underrated, Lodger is probably not an LP for the Bowie novice; it is indeed a "fan's album." This was the last collaboration with Eno and Eno's influence is apparent: musicians switched instruments to sound amateurish on purpose, chord progressions were changed deliberately or turned backward to create something completely new, yet, and despite the heavy use of experimentation, Lodger was a return to a more straightforward rock format. Where the album truly falters is in its recording; this is a poorly mastered disc in any of its iterations.

Released in 1979, Lodger was actually recorded in Switzerland not Berlin and was the last album of the trilogy or "Triptych" as Bowie referred to it. Lodger, a bit top heavy in its construct contained the singles "Boys Keep Swinging," "DJ" and "Look Back in Anger," and unlike the previous LPs, did not have instrumental tracks or ambient soundscapes. Though underrated, Lodger is probably not an LP for the Bowie novice; it is indeed a "fan's album." This was the last collaboration with Eno and Eno's influence is apparent: musicians switched instruments to sound amateurish on purpose, chord progressions were changed deliberately or turned backward to create something completely new, yet, and despite the heavy use of experimentation, Lodger was a return to a more straightforward rock format. Where the album truly falters is in its recording; this is a poorly mastered disc in any of its iterations. Some background: Burnt from the excesses of Los Angeles, "the most vile piss-pot in the world," Bowie was at a breaking point in 1976. Having completed the recording of Station To Station, in a mere two weeks through a blizzard of cocaine (he often now claims he cannot even remember making the record), Bowie left Los Angeles forever. Realizing that much of the money he had made in his career (including the massively successful Ziggy and Young Americans LPs) had gone to support his corrupt manager, Tony Defries, as well as float the MainMan company, Bowie opted out as a tax exile in a small, quaint Swiss town, Vevey.

Some background: Burnt from the excesses of Los Angeles, "the most vile piss-pot in the world," Bowie was at a breaking point in 1976. Having completed the recording of Station To Station, in a mere two weeks through a blizzard of cocaine (he often now claims he cannot even remember making the record), Bowie left Los Angeles forever. Realizing that much of the money he had made in his career (including the massively successful Ziggy and Young Americans LPs) had gone to support his corrupt manager, Tony Defries, as well as float the MainMan company, Bowie opted out as a tax exile in a small, quaint Swiss town, Vevey. After learning that Iggy Pop had been released from rehab at a "mental asylum" (Bowie was one of the only people to have visited him there, bringing with him cocaine as a gift) and looking to record a new album, Bowie was once again on the move; this time to France. Before even playing a note on his own Berlin trilogy, Bowie and Iggy co-wrote the songs that appeared on Iggy's The Idiot at the Chateau d'Herouville studio outside of Paris. After a quick stint on Iggy's subsequent tour, Bowie returned to Herouville and cut most of the tracks for Low, completing the albums closing instrumentals at Berlin's Hansa studio, next to the wall. From the comfort of his new apartment in Berlin, a recovering Bowie wrote and recorded Heroes and assisted Pop with his next LP Lust For Life (once again, co-writing many of the tracks).

With a now trademark change of heart, Bowie upped-stakes after completing the Stage tour in 1978, went travelling and adopted the theme for his final "Berlin" album, Lodger. The great irony is that like the majority of Low, Lodger was not recorded in Berlin, instead Bowie arranged sessions around globetrotting holidays, laying down tracks in Montreux, Switzerland and New York, making the Berlin Trilogy a more varied beast than its name suggests. As if making good on the line "The European canon is here" from Station to Station, Bowie had recorded a trilogy of albums that took much of their influence from Berlin, yet also took on the many-faceted influence of the continent as a whole. The best of the three, Low, is an AM9, fabulous, but not Ziggy.

Published on September 13, 2018 06:57

The Man Who Fell To Earth

"Released the year before Spielberg and Lucas changed the genre and thus hippie sci-fi's last hurrah, this typically fragmented Nicholas Roeg production stars David Bowie in the role he was born (or perhaps reborn) to play — a distinguished visitor from another world." —J. Hoberman, The Village Voice (1976, 138 min, 35mm).

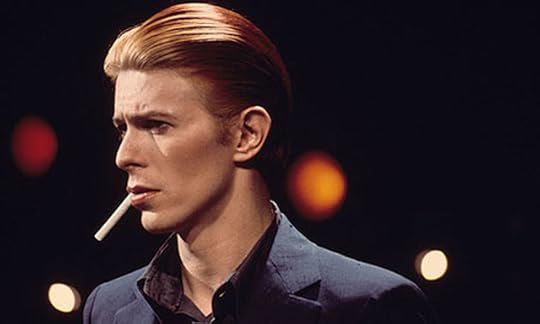

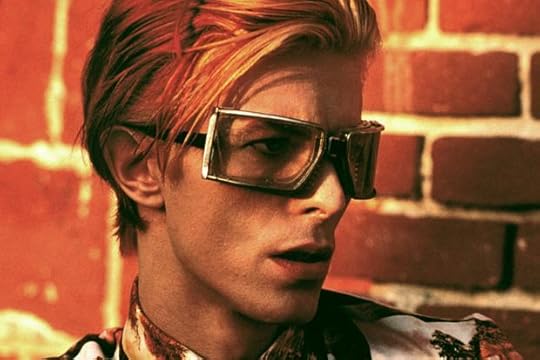

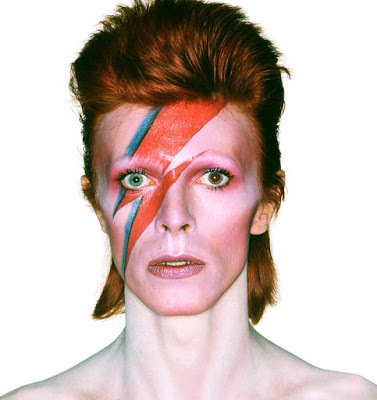

"Released the year before Spielberg and Lucas changed the genre and thus hippie sci-fi's last hurrah, this typically fragmented Nicholas Roeg production stars David Bowie in the role he was born (or perhaps reborn) to play — a distinguished visitor from another world." —J. Hoberman, The Village Voice (1976, 138 min, 35mm).David Bowie is no stranger to film. From Tony Scott's underrated vampire flick The Hunger to Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ (as Pontius Pilate), Bowie’s gaunt, skeletal physique, his otherworldly aura, indeed his alluring alien nature, was the perfect complement to Nicholas Roeg's real-deal alien in the trippy 1976 feature film The Man Who Fell to Earth. Roeg was compelled to cast Bowie as his leading extraterrestrial after watching him in Alan Yentob's way-out-there documentary, Cracked Actor, in which the singer truly resembles an alien life force more than any flesh-and-blood human being.

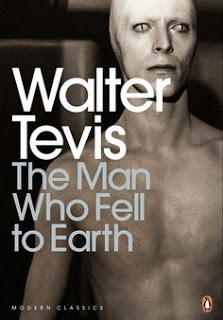

Roeg's hugely ambitious and imaginative film transforms a straightforward science fiction story (from the 1963 novel by Walter Tevis) into a rich kaleidoscope of contemporary America. Thomas Jerome Newton (Bowie), an alien whose understanding of our world is limited to monitoring TV stations, arrives on earth, builds the largest corporate empire in the U.S. to further his mission, and then becomes increasingly frustrated by human emotion and the surreality of [American] life. What follows is as much a love story as sci-fi. Newton becomes involved in an almost pulp-like romance with Mary Lou (Candy Clark), played out to the pop hits of middle America, which culminates in the man's "fall" from innocence. No other pop sci-fi novels (or films), with the exceptions of Stranger in a Strange Land, Childhood's End and Kurt Vonnegut's Sirens of Titan, truly explore the connection between what is speculative about the future and the pop culture in which we live.

Roeg's hugely ambitious and imaginative film transforms a straightforward science fiction story (from the 1963 novel by Walter Tevis) into a rich kaleidoscope of contemporary America. Thomas Jerome Newton (Bowie), an alien whose understanding of our world is limited to monitoring TV stations, arrives on earth, builds the largest corporate empire in the U.S. to further his mission, and then becomes increasingly frustrated by human emotion and the surreality of [American] life. What follows is as much a love story as sci-fi. Newton becomes involved in an almost pulp-like romance with Mary Lou (Candy Clark), played out to the pop hits of middle America, which culminates in the man's "fall" from innocence. No other pop sci-fi novels (or films), with the exceptions of Stranger in a Strange Land, Childhood's End and Kurt Vonnegut's Sirens of Titan, truly explore the connection between what is speculative about the future and the pop culture in which we live.  Ultimately revealing his alien form to Mary Lou, who is overwhelmed and terrified, the couple split. Betrayed by confidant, Dr. Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), Newton is imprisoned by the government in a luxury condo. Intermittent cutscenes show a wife and child slowly dying on Newton's home planet. By film's end, his family has perished and Newton is marooned on earth. We cried when Earth nearly killed E.T., but E.T., in contrast, made a friend and found his way home. In Roeg's space opera, Earth becomes the alien's home, but the result is a broken spirit. (Imagine Spielberg making something like that.) The Man Who Fell to Earth is a sci-fi Days of Wine and Roses for the art-house crowd. The cinematography by Anthony B. Richmond looks fantastic and Bowie's androgynous screen presence is never less than fascinating.

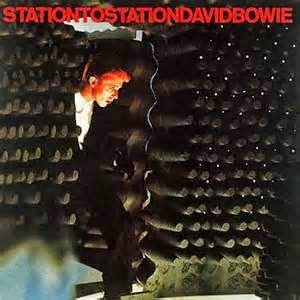

Ultimately revealing his alien form to Mary Lou, who is overwhelmed and terrified, the couple split. Betrayed by confidant, Dr. Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), Newton is imprisoned by the government in a luxury condo. Intermittent cutscenes show a wife and child slowly dying on Newton's home planet. By film's end, his family has perished and Newton is marooned on earth. We cried when Earth nearly killed E.T., but E.T., in contrast, made a friend and found his way home. In Roeg's space opera, Earth becomes the alien's home, but the result is a broken spirit. (Imagine Spielberg making something like that.) The Man Who Fell to Earth is a sci-fi Days of Wine and Roses for the art-house crowd. The cinematography by Anthony B. Richmond looks fantastic and Bowie's androgynous screen presence is never less than fascinating. To be sure, Bowie is top notch as Thomas Jerome Newton, but ironically, he was never consulted on the film's soundtrack. That honor went to another rock star, John Phillips, former leader of '60s folk troubadours the Mamas & the Papas, who hand-picked the OST from a selection of pop, classical and original compositions. It's a soundtrack that truly works, in the same way that Kubrick's 2001 soundtrack, as it appears in the film, is superior to the Alex North film score that Kubrick scrapped (imagine 2001 without "Also Sprach Zarathustra"). Who knows what Bowie would have chosen for incidental music, but interestingly, 1976 simultaneously gave us the Thin White Duke in Bowie's pseudo-masterpiece Station to Station. The LP's cover further convolutes the issue by featuring the alien in his spacecraft. Many made the obvious association, surprised when no Bowie music appears in the film. A wise choice on Roeg's part, Station to Station just didn't fit the Man Who Fell to Earth premise. We're left instead with an interesting if accidental, marketing ploy.

To be sure, Bowie is top notch as Thomas Jerome Newton, but ironically, he was never consulted on the film's soundtrack. That honor went to another rock star, John Phillips, former leader of '60s folk troubadours the Mamas & the Papas, who hand-picked the OST from a selection of pop, classical and original compositions. It's a soundtrack that truly works, in the same way that Kubrick's 2001 soundtrack, as it appears in the film, is superior to the Alex North film score that Kubrick scrapped (imagine 2001 without "Also Sprach Zarathustra"). Who knows what Bowie would have chosen for incidental music, but interestingly, 1976 simultaneously gave us the Thin White Duke in Bowie's pseudo-masterpiece Station to Station. The LP's cover further convolutes the issue by featuring the alien in his spacecraft. Many made the obvious association, surprised when no Bowie music appears in the film. A wise choice on Roeg's part, Station to Station just didn't fit the Man Who Fell to Earth premise. We're left instead with an interesting if accidental, marketing ploy.The New York Times had praise for the film, if not high praise, stating, "There are quite a few science-fiction movies scheduled to come out in the next year or so. We shall be lucky if even one or two are as absorbing and as beautiful as The Man Who Fell to Earth."

Published on September 13, 2018 04:25

September 12, 2018

Station to Station (AM8)

Bowie's vocal tour de force is a restless album jumping genres from track to track. The Thin White Duke is like a manic host insisting you see all the city's clubs in just one night. Epic mounds of cocaine-induced genre jitters, they say, but can vocals this restrained and cadenced be achieved in a dopamine frenzy? You wouldn't think. Bowie moves from funk to funky and ties it all up with his WW ballads, "Word on a Wing" and Dimitri Tiomkin’s Oscar nominated "Wild is the Wind," which drip with enough melodrama to make Roy Orbison cry. What's missing here? Nothing, and that is the issue. We've got funky, we've got Motorik; it's Philly R&B though Euro-centric. It's Earl Slick and Roy Bitten and Carlos Alomar who said, "It was one of the most glorious albums that we've ever done ... We experimented so much on it," and hardly knew when to stop. NME described it as having "an air of regret for missed opportunities and past pleasures." It's just all over the place: it's great then it's not, then it apologizes and makes up for it, overdoes it again. It was indeed drug-induced genius, but does that belittle it? Face it, Dark Side of the Moon was all the more fabulous because you were just so high. Bowie stated that he only "knew he was in L.A., because he had read that he was in L.A." It's an album that came out of a stupor. So do most of our best memories.

The myth that is the Berlin Trilogy (Low was recorded in France and Lodger in Switzerland) tends to negate this author's insistence that Station to Station, Low and Heroes are a continuum and a much more cohesive trilogy. Lodger is a different album altogether, despite its production.

David Bowie was guilty of a lot of AM9s (Diamond Dogs, Hunky Dory, Low), and an AM10 in Ziggy, but Station to Station (AM8) is the little engine that didn't, try as it might. There is too much crammed into 38 minutes – 38 minutes of cocaine bliss. It is just a wee bit too wild in the wind.

Published on September 12, 2018 03:57

September 11, 2018

Young Americans

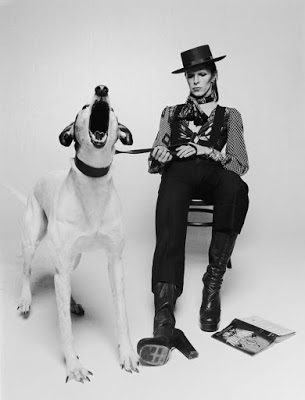

You're walking down the street, minding your own business. Suddenly, a lavender Cadillac pulls up alongside you. The tinted window rolls down and it's Soulboy Dave beckoning to you from his leopard skin upholstery. You get in and minutes later you're at his bachelor pad, a 50s throwback in Old City. Others arrive. The glam-set is down the street still dressed like Ziggy, but you’re here in your soulful finest amidst the beautiful people, mounds of cocaine on a coffee table and everyone drinking cocktails. Bowie had gone plastic soul. For Young Americans, Bowie's Glam edifice was reclad in Philly soul slacks and swapped London's West End for the Tower. During his two-year North American drive-thru, performing Glitter-caked heavy metal at night, Bowie was by day absorbing the sounds of Philadelphia. By 1974, he had already signposted his change of direction on his Orwellian 'concept' album, Diamond Dogs. Listen to "When you rock and Roll with me" and "1984" and you'll get the picture.

You're walking down the street, minding your own business. Suddenly, a lavender Cadillac pulls up alongside you. The tinted window rolls down and it's Soulboy Dave beckoning to you from his leopard skin upholstery. You get in and minutes later you're at his bachelor pad, a 50s throwback in Old City. Others arrive. The glam-set is down the street still dressed like Ziggy, but you’re here in your soulful finest amidst the beautiful people, mounds of cocaine on a coffee table and everyone drinking cocktails. Bowie had gone plastic soul. For Young Americans, Bowie's Glam edifice was reclad in Philly soul slacks and swapped London's West End for the Tower. During his two-year North American drive-thru, performing Glitter-caked heavy metal at night, Bowie was by day absorbing the sounds of Philadelphia. By 1974, he had already signposted his change of direction on his Orwellian 'concept' album, Diamond Dogs. Listen to "When you rock and Roll with me" and "1984" and you'll get the picture. Just in case no one took the hint, Bowie embarked on another jaunt around the states with a convoy of trucks containing a post-apocalyptic cityscape stage set, from which he sang soulful renditions of his back catalog. Listen to David Live and you can hear radically reworked versions of, most notably, "Moonage Daydream," "All the Young Dudes" and a spectacular camp-soul version of "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide." When his convoy of props ended up in the Florida swamps thanks to a road incident, he reconvened at the Curtis Hixon Hall. The Diamond Dogs tour was over and the Philly Dogs tour had begun.

When Young Americans hit the shelves then, nobody should have been surprised. As the album kicks off with the awesome title track, you know that you are in for something special, and 180 diff. He managed to paint a picture of cosmopolitan urban street life and varnishes it with a veneer of contemporary political bile. There is even some prototype rapping at the end. "Win" is a late-night candlelit dinner at the bachelor pad given a dark underbelly by Bowie's deep swimming vocals and decadent phrasing. (Where did Ziggy get that voice? - Think Back to "The Wide-Eyed Boy of Freecloud") "Fascination" is a taster for his later multi-layer production techniques with Eno. Here, they are used to convey an urgent and sexy groove with Luther Vandross superbly played on backing vocals. "Right" continues the theme in a slightly choppier manner and gives way to "Somebody Up There Likes Me,' which, as well as being astoundingly good, conjured up soul images of "The Candidate."

When Young Americans hit the shelves then, nobody should have been surprised. As the album kicks off with the awesome title track, you know that you are in for something special, and 180 diff. He managed to paint a picture of cosmopolitan urban street life and varnishes it with a veneer of contemporary political bile. There is even some prototype rapping at the end. "Win" is a late-night candlelit dinner at the bachelor pad given a dark underbelly by Bowie's deep swimming vocals and decadent phrasing. (Where did Ziggy get that voice? - Think Back to "The Wide-Eyed Boy of Freecloud") "Fascination" is a taster for his later multi-layer production techniques with Eno. Here, they are used to convey an urgent and sexy groove with Luther Vandross superbly played on backing vocals. "Right" continues the theme in a slightly choppier manner and gives way to "Somebody Up There Likes Me,' which, as well as being astoundingly good, conjured up soul images of "The Candidate." "Across the Universe" should be awful, but I love it. Compare Lennon's' original wispy vocals with Bowie's swirling vocal gymnastics and it's plain to see that the whole ethos of the song is bulldozed (only Fiona Apple gets it better). Still, I love it. "Can you hear me" was the song that I used to play in my teens when trying to be sophisticated with the girl of the hour (alongside Tim Curry's 1st LP). The fact that I didn't score once does not detract from the sheer shaggability factor of this song. Then there's "Fame." One night with Lennon on a James Brown trip and you have the King of dancefloor Strutters. It is so cool it's positively arctic.

Published on September 11, 2018 05:27

September 10, 2018

The Atrocity Circus

Diamond Dogs begins like a creeping sickness. Quickly after recording Pin Ups, Bowie's tribute to the music of his youth, he rented a villa in Italy and began writing songs centering on George Orwell's 1984. One obstacle laid in the way: getting permission from Orwell's widow. She refused to allow Bowie to produce a rock-opera of the novel and left Bowie with a suite of unuseable songs. With that, he reconfigured Orwell's dystopian Oceania into Hunger City, a crumbling post-nuclear metropolis with mutated "peoploids" roaming the city in search of food.

Diamond Dogs begins like a creeping sickness. Quickly after recording Pin Ups, Bowie's tribute to the music of his youth, he rented a villa in Italy and began writing songs centering on George Orwell's 1984. One obstacle laid in the way: getting permission from Orwell's widow. She refused to allow Bowie to produce a rock-opera of the novel and left Bowie with a suite of unuseable songs. With that, he reconfigured Orwell's dystopian Oceania into Hunger City, a crumbling post-nuclear metropolis with mutated "peoploids" roaming the city in search of food. "Future Legend" is the gothic funhouse intro to the title track, then things get direr (yes, that's a word)... This ain't rock n' roll, after all, this is genocide. "Diamond Dogs" should keep the proles entertained with its rocky swagger (dig that sax). "Sweet Thing" threatens more funhouse as Bowie goths out the lyrics over tender instrumentation. "Candidate" continues the theme but this time over swirly guitar and honky-tonk-lite piano. As the guitar gets more muscular, emulating the civic decay, the listener is faced with a reprise of "Sweet Thing," a gorgeously evil piece of pomp-rock, strutting its way through lyrics of fame and prostitution, gay sex and serial killers, and beyond into territories familiar to the likes of William Burroughs, Dennis Cooper or The Velvet Underground. The music is the sound of a spider web, with rotting remains of the past hanging from crystalized cocoons. Glam gone gorgeously sour, nightmare as beauty. Halfway through the song goes crunch, and some great gnashing grinding guitars come in for the kill.

From there, "Rebel Rebel" is pure fun, and "Rock N' Roll With Me" is like those false moments in Orwell when people seem "happy." "We Are The Dead" a likable dirge, along the lines of "The Bewley Brothers," then we get funky in "1984," a dark disco trip oozing with Studio 54 at its worst. The bubbly synthwork of "Big Brother" lends itself to its folky-hippy chorus. "Chant Of The Ever Circling Skeletal Family” is the LP's send-off, a chorus that while not really a song caps and reverberates the moral decay of Hunger City. Dogs is a beautiful LP with a less than beautiful concept.

From there, "Rebel Rebel" is pure fun, and "Rock N' Roll With Me" is like those false moments in Orwell when people seem "happy." "We Are The Dead" a likable dirge, along the lines of "The Bewley Brothers," then we get funky in "1984," a dark disco trip oozing with Studio 54 at its worst. The bubbly synthwork of "Big Brother" lends itself to its folky-hippy chorus. "Chant Of The Ever Circling Skeletal Family” is the LP's send-off, a chorus that while not really a song caps and reverberates the moral decay of Hunger City. Dogs is a beautiful LP with a less than beautiful concept.That's the nice part. Now for how I really feel: I always find it amazing when some of the greatest works of art receive unwarranted flack due to pretentious asshole(s) who feel inclined to regurgitate inane opinions in an attempt to indoctrinate everyone on what the ultimate paradigm of "noteworthy" art is. FUCK EM!! Dogs is a phenomenal recording that was light years ahead of its time. The Orwellian concept that permeates this album makes it all the more enthralling.

Published on September 10, 2018 05:54

Pin Ups - Bowie

Pin Ups was conceived as a way to introduce Bowie's audience to songs recorded by fellow English acts, including Pink Floyd, The Mojos, Them, Pretty Things and The Easybeats. "These songs are among my favorites from the '64-'67 period of London," he wrote in the liner notes.These weren't the artists that first made him pick up a guitar, but his friends and contemporaries. While Bowie wasn't the first to release a covers album, Pin Ups was one of the earliest by a rock artist, and to this day, one of the best. Why? Even if it didn't represent the last studio album by his classic backing band, The Spiders from Mars, Bowie didn't just go for the easy score. No, he (they) Ziggy'd the hell out of every track, enveloping each song in starman charisma and panic-in-Detroit urgency.And Bowie being Bowie didn't pick the obvious hits either. With studio technology unavailable to the original artists, including multitrack recording and stacks and stacks of Marshall amps to give it that signature Spiders glam-metal punch, you might mistake this for another Bowie story cycle.

Pin Ups was conceived as a way to introduce Bowie's audience to songs recorded by fellow English acts, including Pink Floyd, The Mojos, Them, Pretty Things and The Easybeats. "These songs are among my favorites from the '64-'67 period of London," he wrote in the liner notes.These weren't the artists that first made him pick up a guitar, but his friends and contemporaries. While Bowie wasn't the first to release a covers album, Pin Ups was one of the earliest by a rock artist, and to this day, one of the best. Why? Even if it didn't represent the last studio album by his classic backing band, The Spiders from Mars, Bowie didn't just go for the easy score. No, he (they) Ziggy'd the hell out of every track, enveloping each song in starman charisma and panic-in-Detroit urgency.And Bowie being Bowie didn't pick the obvious hits either. With studio technology unavailable to the original artists, including multitrack recording and stacks and stacks of Marshall amps to give it that signature Spiders glam-metal punch, you might mistake this for another Bowie story cycle.

Published on September 10, 2018 05:48

Pin UPs - Bowie

Pin Ups was conceived as a way to introduce Bowie's audience to songs recorded by fellow English acts, including Pink Floyd, The Mojos, Them, Pretty Things and The Easybeats. "These songs are among my favorites from the '64-'67 period of London," he wrote in the liner notes.These weren't the artists that first made him pick up a guitar, but his friends and contemporaries. While Bowie wasn't the first to release a covers album, Pin Ups was one of the earliest by a rock artist, and to this day, one of the best. Why? Even if it didn't represent the last studio album by his classic backing band, The Spiders from Mars, Bowie didn't just go for the easy score. No, he (they) Ziggy'd the hell out of every track, enveloping each song in starman charisma and panic-in-Detroit urgency.And Bowie being Bowie didn't pick the obvious hits either. With studio technology unavailable to the original artists, including multitrack recording and stacks and stacks of Marshall amps to give it that signature Spiders glam-metal punch, you might mistake this for another Bowie story cycle.

Pin Ups was conceived as a way to introduce Bowie's audience to songs recorded by fellow English acts, including Pink Floyd, The Mojos, Them, Pretty Things and The Easybeats. "These songs are among my favorites from the '64-'67 period of London," he wrote in the liner notes.These weren't the artists that first made him pick up a guitar, but his friends and contemporaries. While Bowie wasn't the first to release a covers album, Pin Ups was one of the earliest by a rock artist, and to this day, one of the best. Why? Even if it didn't represent the last studio album by his classic backing band, The Spiders from Mars, Bowie didn't just go for the easy score. No, he (they) Ziggy'd the hell out of every track, enveloping each song in starman charisma and panic-in-Detroit urgency.And Bowie being Bowie didn't pick the obvious hits either. With studio technology unavailable to the original artists, including multitrack recording and stacks and stacks of Marshall amps to give it that signature Spiders glam-metal punch, you might mistake this for another Bowie story cycle.

Published on September 10, 2018 05:48

September 9, 2018

Drive-in Saturday

Bowie, throughout his career, would never venture far from the oddities of space and sci-fi. From the Man Who Sold the World to "Oh, You Pretty Things!" there was always a glimpse into another dimension. By Aladdin Sane, the B-Movie 50s had invaded 70s pop with odd misconception. In essence, the style and content of 70s Glam was rooted in rock stars as mutants from the future trying to "blend in" by assembling "authentic" versions of period clothing and getting it wrong. They had 50s shoulder pads and Elvis lamé suits (check), eyeliner and lipstick (so much for blending in); the lyrics drummed up the clichés of 30s gangster flicks, spaceships, motorbikes, aliens and jukeboxes. Indeed a new 50s were invented in the off-kilter 70s. American Graffiti was a box off smash; Elvis, Chuck Berry and Ricky Nelson topped the charts; The Rocky Horror Show opened at the Roxy and Grease on Broadway. The actual 1950s, in all their shadow, were elevated to Eden: a sparklingly innocent contrast to the weariness, grime and open sexuality of the early ’70s.

Bowie, throughout his career, would never venture far from the oddities of space and sci-fi. From the Man Who Sold the World to "Oh, You Pretty Things!" there was always a glimpse into another dimension. By Aladdin Sane, the B-Movie 50s had invaded 70s pop with odd misconception. In essence, the style and content of 70s Glam was rooted in rock stars as mutants from the future trying to "blend in" by assembling "authentic" versions of period clothing and getting it wrong. They had 50s shoulder pads and Elvis lamé suits (check), eyeliner and lipstick (so much for blending in); the lyrics drummed up the clichés of 30s gangster flicks, spaceships, motorbikes, aliens and jukeboxes. Indeed a new 50s were invented in the off-kilter 70s. American Graffiti was a box off smash; Elvis, Chuck Berry and Ricky Nelson topped the charts; The Rocky Horror Show opened at the Roxy and Grease on Broadway. The actual 1950s, in all their shadow, were elevated to Eden: a sparklingly innocent contrast to the weariness, grime and open sexuality of the early ’70s. "Drive-In Saturday" is Bowie's 50s-pop pastiche, though as typical with Bowie there's a twist: "Drive-In Saturday" is a 50s song celebrating the freedoms of the subsequent decade, with Mick Jagger and Twiggy serving as erotic household gods. The premise is that a post-apocalyptic civilization, through fear or reactions from fallout, has forgotten how to have sex, so the kids watch Rolling Stones promos and old films to see how it's done.

"Drive-In Saturday" is Bowie's 50s-pop pastiche, though as typical with Bowie there's a twist: "Drive-In Saturday" is a 50s song celebrating the freedoms of the subsequent decade, with Mick Jagger and Twiggy serving as erotic household gods. The premise is that a post-apocalyptic civilization, through fear or reactions from fallout, has forgotten how to have sex, so the kids watch Rolling Stones promos and old films to see how it's done.It's the first Bowie song to reflect the challenge of Roxy Music, whose first LP (and hit single "Virginia Plain") had come out in the summer of '72. The phased synthesizer lines owe a debt to Brian Eno's squiggles and groans, while Bowie's approach to the material — parodic, subversive, yet done entirely straight-faced — is similar to Bryan Ferry's fractured takes on country-western ("If There Is Something") and torch songs ("Chance Meeting"). We don't often acknowledge Roxy as a Bowie influence, often mistakenly mixing it up.

Bowie wrote "Drive-In Saturday" during a train ride from Seattle to Phoenix in early November 1972. He was unable to sleep and, looking out the window at night while the train was somewhere in the desert, saw a row of nearly 20 enormous silver domes off in the distance, moonlight dancing on their roofs. It intrigued him: what were they? Government post-nuclear-war prep facilities? Secret laboratories?

As with "Oh! You Pretty Things," Bowie"s sci-fi narrative is a cover for a more basic human predicament—how kids, who typically have no idea about sex, have to improvise and fake their way through it, often using film stars and pop music as cues and instructional guides. The idea of groups of teenagers in cars, watching erotic films at a drive-in, as if attending church, is one of Bowie's more melancholy and haunting images. As much as the past can be warped to serve the present's needs, it is equally toxic.

Let me put my arms around your head (dum-do-wah)Gee, it's hot, let's go to bedDon't forget to turn on the lightDon't laugh Babe, it'll be alright (dum-do-wah)Pour me out another phone (dum-do-wah)I'll ring and see if your friends are homePerhaps the strange ones in the domeCan lend us a book we can read up aloneAnd try to get it on like once before,When people stared in Jagger's eyes and scored,Like the video films we sawHis name was always BuddyAnd he'd shrug and ask to stayShe'd sigh like Twig the Wonder KidAnd turn her face away.She's uncertain if she likes himBut she knows she really loves himIt's a crash course for the ravers

It's a drive-in Saturday.

Published on September 09, 2018 11:47

September 8, 2018

Aladdin Sane

Aladdin Sane

(AM8)

Aladdin Sane

(AM8)Artist: David Bowie

Released: April 13, 1973

Produced by: David Bowie, Ken Scott

Tracks: 1) Watch That Man (4:30); 2) Aladdin Sane (5:06); 3) Drive-In Saturday (4:33): 4) Panic In Detroit (4:35); 5) Cracked Actor (3:01); 6) Time (5:15) 7) The Prettiest Star (3:31); 8) Let's Spend the Night Together (3:10); 9) The Jean Genie (4:07) 10) Lady Grinning Soul (3:54)

Band Members: David Bowie – guitar, harmonica, saxophone, vocals; Mick Ronson – guitar, piano, vocals, arrangements; Trevor Bolder – bass guitar; Mick "Woody" Woodmansey – drums; Mike Garson – piano, synthesizers

By the winter of 1972 Bowie was bored. Ziggy Stardust had caught the attention of a society in decline, touching the nerve of an England in meltdown and winning serious critical acclaim along the way. Eager to capitalize on this success Mainman targeted America. A U.S. tour was arranged and in a marketing technique to exaggerate Bowie’s status, no expense was spared. Despite the extravagance, less cosmopolitan states remained cautious and the poorly attended shows drained money. As the financial implications of the tour sank in, a depressed Bowie returned to England to confront the deadline for the next album. After the success of Ziggy, the music press were sharpening their knives expectantly. However, in a move that became typical, Bowie absorbed the pressure, channeling the nervous energy into a schizophrenic self-portrait for his new project, Aladdin Sane.

The schizophrenic nuances found on Aladdin Sane gave an insight into Bowie's mindset as he and the Spiders entered Trident Studios in January 1973 to record. Although Ziggy (the character) had achieved mass critical acclaim, the actor playing him was living in poverty. "A lad insane," as it became known, dealt with the stark contrasts dividing the life of an artist for whom impending stardom was inches out of reach. Although the U.S. tour had been anti-climatic, several switched-on American cities had been captivated by Bowie and, as he pondered the direction of the next record, America dominated his thoughts.

The influence of America saturated the album, with several tracks rooted lyrically in Bowie's American experiences as the bus groaned across the vast wastelands of the land of the free. This is clearly evident on "Panic In Detroit," which channels into the anxieties plighting the streets of Detroit in a Motown-esque call-to-arms, but also in "Watch Than Man" (New York), "Cracked Actor" (Hollywood) and "Time" (New Orleans). The title track with it's cryptic dates (1913, 1937, 197?) allude to the years before the two World Wars, with Bowie anticipating a third.

The most distinctive track on the LP (and certainly the most talked about due to the piano solo by Mike Garson) is indeed the title track. Bowie reportedly rejected Garson's initial solo attempts, one of which was in a blues style, the other with a Latin beat, instead asking for something akin to "avant-garde jazz." Garson thus decided to improvise, and the solo was recorded in just one take. Garson commented in 1999: "I've had more communication in the last 26 years about that one solo than the 11 albums I've done on my own, the six that I've done with another group that I'm co-leader of, hundreds of pieces I've done with other people and the 3,000 pieces of music I've written to date. I don't think there's been a week in those 26 years that have gone by without someone, somewhere, asking me about it!"

The most distinctive track on the LP (and certainly the most talked about due to the piano solo by Mike Garson) is indeed the title track. Bowie reportedly rejected Garson's initial solo attempts, one of which was in a blues style, the other with a Latin beat, instead asking for something akin to "avant-garde jazz." Garson thus decided to improvise, and the solo was recorded in just one take. Garson commented in 1999: "I've had more communication in the last 26 years about that one solo than the 11 albums I've done on my own, the six that I've done with another group that I'm co-leader of, hundreds of pieces I've done with other people and the 3,000 pieces of music I've written to date. I don't think there's been a week in those 26 years that have gone by without someone, somewhere, asking me about it!"

Published on September 08, 2018 09:12

September 7, 2018

Hunky Dory

Hunky Dory was the fourth album in Bowie's discography and his first for RCA Records. When he began recording the album in the summer of 1971, he was without a recording contract and was only several years removed from "dustbin shopping" for clothes on Carnaby Street with Marc Bolan of T-Rex. With the exception of the heavier sounding The Man Who Sold the World, his previous album, Bowie was more or less a folky singer-songwriter whose clever lyrics set him apart from his contemporaries and promised a bright future ahead.

Hunky Dory was the fourth album in Bowie's discography and his first for RCA Records. When he began recording the album in the summer of 1971, he was without a recording contract and was only several years removed from "dustbin shopping" for clothes on Carnaby Street with Marc Bolan of T-Rex. With the exception of the heavier sounding The Man Who Sold the World, his previous album, Bowie was more or less a folky singer-songwriter whose clever lyrics set him apart from his contemporaries and promised a bright future ahead. Hunky Dory represents the coming of age of a yet-to-be iconic superstar who used the album to tinker with the sounds and themes that he wanted and later explored on The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars (1972). The LP is also is the first in which he was backed by his Spiders From Mars (Mick Ronson on guitars, Trevor Bolder on bass guitar, and Mick Woodmansey on drums with a special appearance by Rick Wakeman on keyboards).

The opening track "Changes" is representative of the mood Hunky Dory evokes. It brings Bowie back to his breezy, Anthony Newley style of song craftsmanship that he was known for at the beginning of his career. The song is a subtle acknowledgment that he would not be occupying this particular artistic space for very long, as he sings, "Strange fascination, fascinating me / Changes are taking the pace I'm going through." The track remains his most iconic radio tune.

Impending fatherhood was another influence on this album with "Oh! You Pretty Things" as one example. In this song, Bowie muses about the superman race emerging in the form of his son Duncan, then called Zowie. Oddly enough, the song was covered by Peter Noone of Herman’s Hermits and became a hit in England. The other song inspired by his son is "Kooks," a nod to the works of Neil Young who Bowie happened to be listening to when he heard the news of his son's birth.

Impending fatherhood was another influence on this album with "Oh! You Pretty Things" as one example. In this song, Bowie muses about the superman race emerging in the form of his son Duncan, then called Zowie. Oddly enough, the song was covered by Peter Noone of Herman’s Hermits and became a hit in England. The other song inspired by his son is "Kooks," a nod to the works of Neil Young who Bowie happened to be listening to when he heard the news of his son's birth.Sandwiched in between these odes to his son are "Eight Line Poem" and the timeless "Life On Mars?," which Pitchfork named the best song of the 1970s in their recent list. While you would get many good arguments against Pitchfork's declaration (for me, of course, my guilty pleasures are "Bennie and the Jets," "Ventura Highway" and 10cc's "I'm Not in Love) there's no denying that it remains one of the best songs in Bowie's catalog and iconic radio fare. BBC Radio 2's Sold on Song describes it as "a cross between a Broadway musical and a Salvador Dali painting."

The genesis of "Life On Mars?" can be traced back to 1968. Bowie had written the English lyrics for a French song called "Comme, D'Habitude" and called his version "Even a Fool Learns to Love." Unfortunately, the song was never released, and shortly afterward Paul Anka heard the original version, bought the rights and rewrote it as "My Way." Anka passed the song along to Frank Sinatra and it became synonymous with Ol' Blue Eyes. Originally, out of anger at his misfortune, Bowie recorded "Life On Mars?" as a Sinatra parody. He eventually made his peace with it and in the liner notes, he wrote that the song was "inspired by Frankie.

The final track on side one is "Quicksand," a ballad that touches on some of Bowie's non-musical influences like Buddhism, Nietzsche, Aleister Crowley, and the occult. Co-producer Ken Scott had just finished engineering George Harrison's All Things Must Pass and wanted to create a very similar sound using multiple tracks of acoustic guitars.

Side two opens with a cover of the Biff Rose/Paul Williams composition "Fill Your Heart," which sort of acts as a buffer for the next three songs that pay homage to Bowie's three major influences, "Andy Warhol," "Song for Bob Dylan" and "Queen Bitch." The latter was written as a tribute to The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed in particular. If you listen closely, you can hear hints of "Sweet Jane." The song's arrangement is very similar to the style Bowie would display on The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust the following year.

Side two opens with a cover of the Biff Rose/Paul Williams composition "Fill Your Heart," which sort of acts as a buffer for the next three songs that pay homage to Bowie's three major influences, "Andy Warhol," "Song for Bob Dylan" and "Queen Bitch." The latter was written as a tribute to The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed in particular. If you listen closely, you can hear hints of "Sweet Jane." The song's arrangement is very similar to the style Bowie would display on The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust the following year. The final song is a ballad called "The Bewlay Brothers." It was one of the last to be written and recorded for the album. Bowie told producer Ken Scott that he wrote the song with the American market in mind because "the Americans always like to read into things, even though the lyrics make absolutely no sense."

Although it received high praise from the critics, Hunky Dory did not really take off until the middle of 1972, after the commercial breakthrough of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust. Even Bowie himself credits the album as one of the most important of his career. He told Chris Roberts of Uncut Magazine in 1999, "Hunky Dory gave me a fabulous groundswell. I guess it provided me, for the first time in my life, with an actual audience—I mean, people actually coming up to me and saying, 'Good album, good songs.' That hadn't happened to me before. It was like, 'Ah, I'm getting it, I'm finding my feet. I'm starting to communicate what I want to do. Now: what is it I want to do?' There was always a double whammy there."

1971 was a remarkably great year for music and Hunky Dory was a huge reason why. For David Bowie, it concluded phase one of a brilliant career that can only be rivaled by ?

Published on September 07, 2018 12:59