R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 61

August 10, 2018

n. slang, the image of a person, usually with only the head and upper body visible, talking to the camera, as in a documentary, news show, or similar work

Talking Heads

Early in 1976, RISD students, Talking Heads (David Byrne, Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth), made their first demo, recording "Psycho Killer," "First Week, Last Week/Carefree" and "Artists Only" for Beserkeley Records. The result, completed with a live version of "1,2,3 Red Light" (which didn't surface as a bootleg EP until the early eighties), revealed the group to have had a simple, eclectic charm that was vanishing by the time they made their first LP. Later demo sessions followed in the summer of '76, and in November, the group signed with Sire Records - home of the Ramones and the Flamin' Groovies. In December, the three-piece line-up recorded its first single, "Love Goes To Buildings On Fire"/"New Feeling" - issued early in the new year. Neither track has appeared on a Talking Heads LP, although "New Feeling" was re-cut for the debut album, and the A-side was included on Sire's New Wave Sampler. By the time the single was released, Talking Heads had become a four-piece. Jerry Harrison, guitarist in the original Modern Lovers behind Jonathan Richman, had been recommended to the group; after a couple of trial gigs late in 1976, he agreed to join the band as soon as his other commitments were fulfilled.

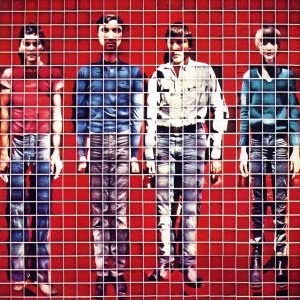

In April, the foursome began recording their first LP, which was completed in July after a series of gigs in Europe. Talking Heads 77 was issued in September 1977 in the States, a month later in the U.K. The album was a minor triumph. While other New York acts concentrated on getting across their emotions with raw power, Talking Heads made gentle, almost placid music, saving their killer punch for the lyrics.

For my father, it was one of the simplest billboards he had ever painted; simply a red orange background with yellow letters 4½ feet high that said "Talking Heads 77." As an Angeleno, and just a kid at the time, I had no exposure to the New York Scene at CBGBs – no Blondie, no Ramones, no Talking Heads. L.A. was about jazz and a lighter, more accessible rock (Weather Report, The Eagles, Fleetwood Mac and Steely Dan, and the myriad of amazing music from an amazing year), and somehow it glossed over the New York scene. Conversely London's new wave, from Elvis Costello and Joe Jackson to the Clash made it to the clubs. Out of it would come L.A. punk, with New York playing little role in L.A.'s evolution. Talking Heads were the exception.

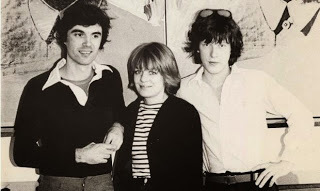

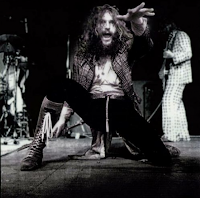

Talking Heads at the Factory, 1977Six months later, July 1978, the band released More Songs About Buildings and Food, and struck it big with the hit "Take Me to the River," a cover of the 1974 Al Green tune. Of the album, Salon wrote: "More Songs About Buildings and Food [is] a backwards exorcism of frozen-brittle guitars, smeared textures and super-ecstatic vocals. The record brought forth an essential darkness and didn’t try to extinguish it. These were songs about emotions that lurk, about the secret part of ourselves that knows people can see right through us on buses, planes and subways, all sung by a disjointed, ferocious, manic, shivering guy named David Byrne It was a kind of State of the Union address, examining the nation’s health from a dozen different angles, including the sky." Talking Heads were the art rock to come.

Talking Heads at the Factory, 1977Six months later, July 1978, the band released More Songs About Buildings and Food, and struck it big with the hit "Take Me to the River," a cover of the 1974 Al Green tune. Of the album, Salon wrote: "More Songs About Buildings and Food [is] a backwards exorcism of frozen-brittle guitars, smeared textures and super-ecstatic vocals. The record brought forth an essential darkness and didn’t try to extinguish it. These were songs about emotions that lurk, about the secret part of ourselves that knows people can see right through us on buses, planes and subways, all sung by a disjointed, ferocious, manic, shivering guy named David Byrne It was a kind of State of the Union address, examining the nation’s health from a dozen different angles, including the sky." Talking Heads were the art rock to come.

The Heads' sophomore effort saw the first of their production/collaborations with Brian Eno, who adds a smoothness and depth to the angular and jerky-yet-machinistic moves from the Heads' practica, while Byrne's songwriting starts to merge with the growing atmospheric sensibilities that would emerge as this creative partnership evolved. Here Byrne's lyrics enhance their look at a dark world, a pattern that would grow to overwhelming levels on the subsequent two albums. I can't tell you how many times I listened to this album in my youth. Good to the last drop. Their masterpiece? Perhaps. Indispensable? You know it. Another side of the seventies; 40 years ago.

"What are you painting?" I asked him. He never knew.

"It says, 'Talking Heads '77'." He didn't know Elton John, he surely wouldn't have known Talking Heads. Nor did I, but he took me to Tower Records and I bought it with birthday money; a cassette. He took me to Ben Frank's. I had a chili-size and a chocolate Coke. He had breakfast. - From Jay and the Americans

Early in 1976, RISD students, Talking Heads (David Byrne, Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth), made their first demo, recording "Psycho Killer," "First Week, Last Week/Carefree" and "Artists Only" for Beserkeley Records. The result, completed with a live version of "1,2,3 Red Light" (which didn't surface as a bootleg EP until the early eighties), revealed the group to have had a simple, eclectic charm that was vanishing by the time they made their first LP. Later demo sessions followed in the summer of '76, and in November, the group signed with Sire Records - home of the Ramones and the Flamin' Groovies. In December, the three-piece line-up recorded its first single, "Love Goes To Buildings On Fire"/"New Feeling" - issued early in the new year. Neither track has appeared on a Talking Heads LP, although "New Feeling" was re-cut for the debut album, and the A-side was included on Sire's New Wave Sampler. By the time the single was released, Talking Heads had become a four-piece. Jerry Harrison, guitarist in the original Modern Lovers behind Jonathan Richman, had been recommended to the group; after a couple of trial gigs late in 1976, he agreed to join the band as soon as his other commitments were fulfilled.

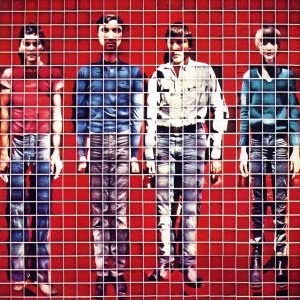

In April, the foursome began recording their first LP, which was completed in July after a series of gigs in Europe. Talking Heads 77 was issued in September 1977 in the States, a month later in the U.K. The album was a minor triumph. While other New York acts concentrated on getting across their emotions with raw power, Talking Heads made gentle, almost placid music, saving their killer punch for the lyrics.

For my father, it was one of the simplest billboards he had ever painted; simply a red orange background with yellow letters 4½ feet high that said "Talking Heads 77." As an Angeleno, and just a kid at the time, I had no exposure to the New York Scene at CBGBs – no Blondie, no Ramones, no Talking Heads. L.A. was about jazz and a lighter, more accessible rock (Weather Report, The Eagles, Fleetwood Mac and Steely Dan, and the myriad of amazing music from an amazing year), and somehow it glossed over the New York scene. Conversely London's new wave, from Elvis Costello and Joe Jackson to the Clash made it to the clubs. Out of it would come L.A. punk, with New York playing little role in L.A.'s evolution. Talking Heads were the exception.

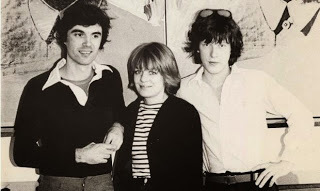

Talking Heads at the Factory, 1977Six months later, July 1978, the band released More Songs About Buildings and Food, and struck it big with the hit "Take Me to the River," a cover of the 1974 Al Green tune. Of the album, Salon wrote: "More Songs About Buildings and Food [is] a backwards exorcism of frozen-brittle guitars, smeared textures and super-ecstatic vocals. The record brought forth an essential darkness and didn’t try to extinguish it. These were songs about emotions that lurk, about the secret part of ourselves that knows people can see right through us on buses, planes and subways, all sung by a disjointed, ferocious, manic, shivering guy named David Byrne It was a kind of State of the Union address, examining the nation’s health from a dozen different angles, including the sky." Talking Heads were the art rock to come.

Talking Heads at the Factory, 1977Six months later, July 1978, the band released More Songs About Buildings and Food, and struck it big with the hit "Take Me to the River," a cover of the 1974 Al Green tune. Of the album, Salon wrote: "More Songs About Buildings and Food [is] a backwards exorcism of frozen-brittle guitars, smeared textures and super-ecstatic vocals. The record brought forth an essential darkness and didn’t try to extinguish it. These were songs about emotions that lurk, about the secret part of ourselves that knows people can see right through us on buses, planes and subways, all sung by a disjointed, ferocious, manic, shivering guy named David Byrne It was a kind of State of the Union address, examining the nation’s health from a dozen different angles, including the sky." Talking Heads were the art rock to come.The Heads' sophomore effort saw the first of their production/collaborations with Brian Eno, who adds a smoothness and depth to the angular and jerky-yet-machinistic moves from the Heads' practica, while Byrne's songwriting starts to merge with the growing atmospheric sensibilities that would emerge as this creative partnership evolved. Here Byrne's lyrics enhance their look at a dark world, a pattern that would grow to overwhelming levels on the subsequent two albums. I can't tell you how many times I listened to this album in my youth. Good to the last drop. Their masterpiece? Perhaps. Indispensable? You know it. Another side of the seventies; 40 years ago.

"What are you painting?" I asked him. He never knew.

"It says, 'Talking Heads '77'." He didn't know Elton John, he surely wouldn't have known Talking Heads. Nor did I, but he took me to Tower Records and I bought it with birthday money; a cassette. He took me to Ben Frank's. I had a chili-size and a chocolate Coke. He had breakfast. - From Jay and the Americans

Published on August 10, 2018 13:08

August 9, 2018

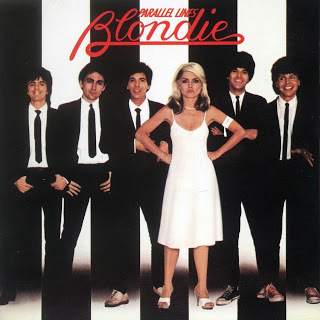

Parallel Lines

In L.A. we didn't discover Blondie until Parallel Lines (AM9) in 1978. '78 had been another stellar and eclectic, evolutionary year (Devo-lutionary as well). Blondie, like Talking Heads, first appeared at CBGB in '75 and was immediately dismissed as a '60s throwback pop group. Few could anticipate that Debbie Harry & Co. would become the most successful band from that scene.On their 1976 debut, Blondie offered a fully realized version of what they were all about: equal parts girl-group pop, British Invasion rock 'n' roll, B-movie kitsch and classic sex appeal all rolled into one. The unmistakable focal point was Debbie Harry, who knew her strengths and played them to the max. But the rest of the band provided the solid musical backing she needed to reach superstardom; not a simple task for a punk band.

In L.A. we didn't discover Blondie until Parallel Lines (AM9) in 1978. '78 had been another stellar and eclectic, evolutionary year (Devo-lutionary as well). Blondie, like Talking Heads, first appeared at CBGB in '75 and was immediately dismissed as a '60s throwback pop group. Few could anticipate that Debbie Harry & Co. would become the most successful band from that scene.On their 1976 debut, Blondie offered a fully realized version of what they were all about: equal parts girl-group pop, British Invasion rock 'n' roll, B-movie kitsch and classic sex appeal all rolled into one. The unmistakable focal point was Debbie Harry, who knew her strengths and played them to the max. But the rest of the band provided the solid musical backing she needed to reach superstardom; not a simple task for a punk band.On 1977's follow-up album, Plastic Letters, Blondie added more aggression to punk mix and by the time the started working on their third album they were branching out, experimenting with the music. Released in September '78, Parallel Lines was the culmination of everything Blondie was working toward, both musically and stylistically: a modern pop record nodding to the past and looking to the future and kicking off with a killer track — a cover of Los Angeles rockers the Nerves' "Hanging on the Telephone." Blondie completely owned the song, turning into a power-pop gem and a punk anthem.

It's followed by the popular raunchy rocker "One Way or Another," which features one of Harry’s best vocal performances, as well as some great guitar riffing. Parallel Lines takes a left turn by track 4 with "Fade Away and Radiate," featuring the album’s most haunting synth lines (in a punk band?), pounding drums and one of Harry's most sultry vocals. King Crimson's Robert Fripp helps set the mood with a guitar line that spins Blondie in a totally new direction. At the end of the song, it drifts into a reggae groove, something the band would explore in detail later in its career.

Blondie eventually return to their pop roots on "Sunday Girl," written by guitarist Chris Stein. The song looks back on the great pop songs of the past decade while keeping firmly placed in 1978. And then comes the bomb. "Heart of Glass," dates back to CBGB in 1975, when it was known as "Once I Had a Love" and played as a reggae shuffle. Producer Mike Chapman suggested that the band rework the song as a disco track, and it became their first No. 1 hit. This monster propelled Parallel Lines to the upper region of the charts. It sold a million copies. And it remains Blondie’s most popular (and arguably best) album.

Many of us were in recovery mode. High School over, Blondie was just in time for our college radio years. It was hard giving up our stuffy prog, but it was time to go wild.

Published on August 09, 2018 06:17

August 6, 2018

Nothing Really Matters

From a treatise on the Catholic Church and the repercussions of Galileo's dispute with Cardinal Bellarmine to the most transparent of all interpretations – a young man pleading to an unsympathetic jury after murdering a man – "Bohemian Rhapsody" may instead simply be the nonsense that Freddie Mercury typically claimed it was. (Though in a more lucid moment Mercury stated, "It's one of those songs which has such a fantasy feel about it. I think people should just listen to it, think about it, and then make up their own minds as to what it says to them. 'Bohemian Rhapsody' didn't just come out of thin air. I did a bit of research although it was tongue-in-cheek and mock opera. Why not?")

From a treatise on the Catholic Church and the repercussions of Galileo's dispute with Cardinal Bellarmine to the most transparent of all interpretations – a young man pleading to an unsympathetic jury after murdering a man – "Bohemian Rhapsody" may instead simply be the nonsense that Freddie Mercury typically claimed it was. (Though in a more lucid moment Mercury stated, "It's one of those songs which has such a fantasy feel about it. I think people should just listen to it, think about it, and then make up their own minds as to what it says to them. 'Bohemian Rhapsody' didn't just come out of thin air. I did a bit of research although it was tongue-in-cheek and mock opera. Why not?")The epic radio opera need not be analyzed in such a fashion. On a cursory level, we can instead course the trajectory of the song through its emotional content. At first, for instance, there is Confusion: "Is this the real life?/ Is this just fantasy?" Nonchalance: "Because I'm easy come, easy go,/ Little high, little low,/ Any way the wind blows doesn't really matter to me, to me." Next comes Cognition: "Mama, just killed a man,/ Put a gun against his head, pulled my trigger, now he's dead," and Regret: "Mama, life had just begun,/ But now I've gone and thrown it all away." There is Acceptance: "Too late, my time has come…/ Gotta leave you all behind and face the truth," followed by Fear and Sorrow: "Mama…I don't wanna die,/ I sometimes wish I'd never been born at all."

All of this leads to a trial or sentencing (whether real or imagined) in which reality is shattered: "I see a little silhouetto of a man,/ Scaramouche, Scaramouche [a character from Punch and Judy], will you do the fandango?/ Thunderbolt and lightning, very, very frightening." There is a Plea: "I'm just a poor boy, nobody loves me./" And a choral response: "He's just a poor boy from a poor family,/ Spare him his life from this monstrosity." And finally Judgment: "Bismillah! [The first word of each chapter in the Quran, meaning 'In the name of Allah']/ No, we will not let you go./ [The chorus replying:] Let him go."

From this comes Anger, steps, as if this were the stages of grief: "So you think you can stone me and spit in my eye/ So you think you can love me and leave me to die/ Oh, baby, can't do this to me, baby,/ Just gotta get out, just gotta get right outta here." And since getting "right out of here" is not possible, there is final Resignation: "Nothing really matters, Anyone can see,/ Nothing really matters, nothing really matters to me."

From this comes Anger, steps, as if this were the stages of grief: "So you think you can stone me and spit in my eye/ So you think you can love me and leave me to die/ Oh, baby, can't do this to me, baby,/ Just gotta get out, just gotta get right outta here." And since getting "right out of here" is not possible, there is final Resignation: "Nothing really matters, Anyone can see,/ Nothing really matters, nothing really matters to me."Said Brian May, "Freddie was a very complex person: flippant and funny on the surface, but he concealed insecurities and problems in squaring up his life with his childhood. He never explained the lyrics, but I think he put a lot of himself into that song."

Indeed there is an interminable amount of ballyhoo over this, the greatest of rock singles and arguable the most iconic rock song of all time (if that is what it is), and meaning is indeed up to the interpreter, yet from an emotional standpoint, "Bohemian Rhapsody" is no mere anthem (leave that for "We Are the Champions"), it is an epic track with an epic emotional content that better than I will contemplate. Will it really matter?

Published on August 06, 2018 04:21

August 5, 2018

Killer Queen

Pompus? Yes. Pretentious? Of course. Over the top? Undoubtedly. "Bohemian Rhapsody?" No, actually I meant Peter O'Toole's performance in Lawrence of Arabia. O'Toole was one of the greatest movie actors of his (or any) time because he could be all those things and make it work. Brilliantly. Queen was the Peter O'Toole of rock, pushing the envelope in every direction, and (mostly) pulling it off. Unfortunately, A Night At The Opera suffers from an issue similiar to that of Bowie's Hunky Dory or Lennon's Imagine: A Night At The Opera is so much more than "The Album With 'Bohemian Rhapsody.'" It's an epic, beautifully composed rock album, with all the pieces - including "Rhapsody" - in the right places. A Night At The Opera is to the seventies what Sgt. Pepper was to the sixties, a tour de force that happens to encompass the most famous song in the world! What makes the LP shine is how well the album works as a musical whole. It functions as ONE perfectly structured piece of rhapsodic music rather than a mere collection of songs. One track logically leads to another, and even "silly" tunes like "Lazing on a Sunday Afternoon" or "Seaside Rendezvous." fit perfectly in the larger framework of the album. A Night at the Opera (AM9) has been ablaze on our turntables for forty years!

Pompus? Yes. Pretentious? Of course. Over the top? Undoubtedly. "Bohemian Rhapsody?" No, actually I meant Peter O'Toole's performance in Lawrence of Arabia. O'Toole was one of the greatest movie actors of his (or any) time because he could be all those things and make it work. Brilliantly. Queen was the Peter O'Toole of rock, pushing the envelope in every direction, and (mostly) pulling it off. Unfortunately, A Night At The Opera suffers from an issue similiar to that of Bowie's Hunky Dory or Lennon's Imagine: A Night At The Opera is so much more than "The Album With 'Bohemian Rhapsody.'" It's an epic, beautifully composed rock album, with all the pieces - including "Rhapsody" - in the right places. A Night At The Opera is to the seventies what Sgt. Pepper was to the sixties, a tour de force that happens to encompass the most famous song in the world! What makes the LP shine is how well the album works as a musical whole. It functions as ONE perfectly structured piece of rhapsodic music rather than a mere collection of songs. One track logically leads to another, and even "silly" tunes like "Lazing on a Sunday Afternoon" or "Seaside Rendezvous." fit perfectly in the larger framework of the album. A Night at the Opera (AM9) has been ablaze on our turntables for forty years! What makes the early 70s rock's golden years is its incredible diversity. While the Laurel Canyon set embellished their folk risings with jazz and orchestration, Gentle Giant and Jethro Tull peppered their progressive slant with madrigals and mandolins. The Eagles made country a top seller as Zeppelin rocked like no one had before (or maybe will again). Small wonder that Queen was able to capture our collective imagination with vaudeville, mock operas and theatrics.

What makes the early 70s rock's golden years is its incredible diversity. While the Laurel Canyon set embellished their folk risings with jazz and orchestration, Gentle Giant and Jethro Tull peppered their progressive slant with madrigals and mandolins. The Eagles made country a top seller as Zeppelin rocked like no one had before (or maybe will again). Small wonder that Queen was able to capture our collective imagination with vaudeville, mock operas and theatrics.Sheer Heart Attack (AM8) is the strongest LP in Queen's storied career (the stronger album does not necessarily suggest that it had more impact or longer legs). Capturing the first major transition of their career, the album incorporates aspects of prog-like hard rock (Queen II) and the more eclectic arena rock of A Night at the Opera to produce the band's catchiest set of melodies. The album lacks anything as timeless as "Bohemian Rhapsody," but pretty much every album in the history of the world fails in this respect. Where Sheer Heart Attack vastly outperforms A Night at the Opera is in its consistency. In fact, when Sheer Heart Attack does opt for shorter "filler" pieces ("Lily of the Valley," "Dear Friends," "Misfire") the results are some of the LP's finest moments.

Sheer Heart Attack is much more diverse than the band's first two LPs, a shift that allows May and (especially) Mercury to flex their musical muscle for the first time. Campy glam rock ("In the Lap of the Gods"), Aerosmithy hard core ("Stone Cold Crazy"), and even atmospheric proto-dream pop (May's stunning "She Makes Me") are all ably performed. That, coupled with the fact that many of the best selections here weren't huge "hits" ("Killer Queen" being the only exception), makes Sheer Heart Attack an excellent entry point into the band's early discography for a listener looking to explore beyond a greatest hits compilation.

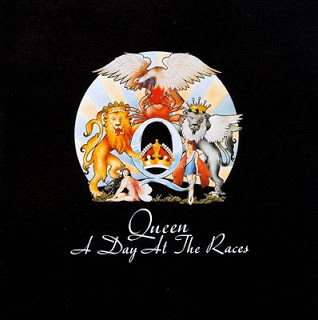

Released shortly after the blockbuster, genre-defining success of A Night at the Opera, A Day at the Races (AM7) was constructed, not as something to try and top it, but to refine what A Night at the Opera accomplished, a "sister album," so to speak. The title of each LP, taken from the titles of Marx Brothers' films suggest that the latter was a mere sequel the other, when in fact it's a very different kind of album and stands individually by its own right. An important difference is in the album's structure: no more long, sophisticated epics like Bohemian Rhapsody and the Prophet's Song, or short little anecdotes like Lazying On A Sunday Afternoon; ten songs, all of them of standard radio lenghth, roughly between three and five minutes, with only two exceptions. Not only does it end Queen's progressive opera-rock era, it also ends Freddie Mercury's domination of the band. Not only did Freddie and guitarist Brian May supply the same number of songs, which is a first by itself; the album clearly belongs mostly to Brian. Songs of his open and close the album, and it also starts with an instrumental introduction which is something of a medley of only his own contributions to the album. These changes should have made it much more commercialy appealing than the band's previous albums, but strangely enough it did poorly compared to 'A Night At The Opera' and 'Sheer Heart Attack' (except for in Japan, where 'A Day At The Races' was Queen's first no. 1 album).

Released shortly after the blockbuster, genre-defining success of A Night at the Opera, A Day at the Races (AM7) was constructed, not as something to try and top it, but to refine what A Night at the Opera accomplished, a "sister album," so to speak. The title of each LP, taken from the titles of Marx Brothers' films suggest that the latter was a mere sequel the other, when in fact it's a very different kind of album and stands individually by its own right. An important difference is in the album's structure: no more long, sophisticated epics like Bohemian Rhapsody and the Prophet's Song, or short little anecdotes like Lazying On A Sunday Afternoon; ten songs, all of them of standard radio lenghth, roughly between three and five minutes, with only two exceptions. Not only does it end Queen's progressive opera-rock era, it also ends Freddie Mercury's domination of the band. Not only did Freddie and guitarist Brian May supply the same number of songs, which is a first by itself; the album clearly belongs mostly to Brian. Songs of his open and close the album, and it also starts with an instrumental introduction which is something of a medley of only his own contributions to the album. These changes should have made it much more commercialy appealing than the band's previous albums, but strangely enough it did poorly compared to 'A Night At The Opera' and 'Sheer Heart Attack' (except for in Japan, where 'A Day At The Races' was Queen's first no. 1 album). An aside: It's interesting to note that there are many observers from the Indian intelligentsia who place the achievements of Freddie Mercury (nee Farrokh Bulsara) on the same plateau as that of Salman Rushdie and Vikram Seth, in essence taking the colonizer's art form and representing it in a manner richer and more dazzling than many Anglophones thought possible. Right on, Freddy!

An aside: It's interesting to note that there are many observers from the Indian intelligentsia who place the achievements of Freddie Mercury (nee Farrokh Bulsara) on the same plateau as that of Salman Rushdie and Vikram Seth, in essence taking the colonizer's art form and representing it in a manner richer and more dazzling than many Anglophones thought possible. Right on, Freddy!And another: Many would insist that in Queen, The Tubes and Kiss there is proof that glam wasn't dead. So be it. If Queen is glam then indeed Jethro Tull deserved their Grammy for Best Hard Rock/Heavy Metal performance. The Tubes were theatrics and parody, and a Kiss is still a Kiss (a sigh is just a sigh) - no categorization necessary.

And yet another: The early 70s are touted by many as a renaissance. Wrong word. A renaissance is a period of rebirth, like the phoenix re-spawning from its ashes, like Europe emerging from the dark ages. The Renaissance in Europe, arguably began with the bronze doors of the Florentine Baptistery, when art was given a time and place. From a 20th Century music vantage point, there had been no dark ages, nothing to rise above or out of. If anything, the early 70s were a golden age, a belle époque, the apogee, a culmination - long live the Queen.

Published on August 05, 2018 04:55

August 4, 2018

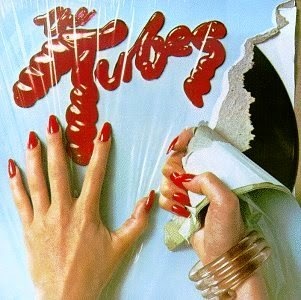

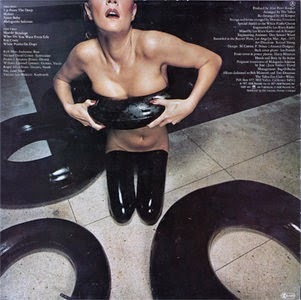

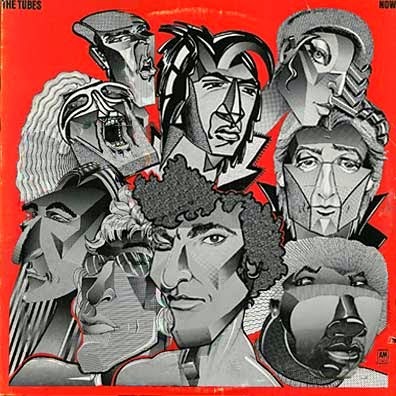

The Tubes

Meanwhile.

Meanwhile.Amidst all the bally-hoo and pretentiousness of prog, the music of my teen years wasn't limited to 20 minute songs that would feel at home in the Italian Rennaisance. There was the blues of Humble Pie, The whole Laurel Canyon scene, of course (although I hadn't fully discovered it yet), there was Led Zeppelin and Elton John and a plethora of music that wasn't even remotely proggy. And then there was The Tubes.

Spawned in the arid nothingness of late-60s Arizona, Fee Waybill and his band wove a crazed concoction of twin guitar harmonies, weird noises, flamenco diddles, castanets, and angelic choirs into an instantly lovable debut. Not unlike The Dictators' Go Girl Crazy! and Godley Creme, the eponymous debut album provides a bridge between multiple rock styles with comedic zigzags at every turn.

The bright spots for The Tubes were very bright. "Haloes" in particular and "Space Baby" sparkle with a Ziggy-esque strut and a myriad of guitar histrionics. Blurts of synth-funk and boogie-woogie piano make man's search for meaning a lot more fun in "What Do You Want from Life?" And of course, the iconic "White Punks on Dope" eclipses every anthem since cavemen began banging on rocks. If there is criticism, it's obvious that this is a soundtrack to performance art; much of it simply had to be experienced in a visual medium for full appreciation. Simply put, they garnered none of the reputation yet the Tubes broke as many barriers as Iggy, Bowie and Zappa. They may well be the most underrated band in rock history.

The Tubes were discovered by the legendary Al Kooper, who also produced the album. Kooper is the most influential person in rock 'n' roll that no one has ever heard of. Without him The Tubes wouldn't exist, nor would Lynyrd Skynyrd. Dylan's "Like A Rollin' Stone" wouldn't have its classic organ, "You Can't Always Get What You Want" would pale without the piano and French horn at its ontset, and [umpteen other examples]. In the mid 70s such complex, background rich production was uncommon (replaced by synthesizers and tricks), and this, coupled with the band's, "strange bend" made The Tubes a standout debut. While many knew and remember the Tubes for their over the top outrageousness, there was a plethora of awesome musicians: Prairie Prince on drums, Roger Allen Steed and the incomparable Bill Spooner on guitars, and of course, Fee Waybill's lyrics and delivery were one of a kind.

The Tubes were discovered by the legendary Al Kooper, who also produced the album. Kooper is the most influential person in rock 'n' roll that no one has ever heard of. Without him The Tubes wouldn't exist, nor would Lynyrd Skynyrd. Dylan's "Like A Rollin' Stone" wouldn't have its classic organ, "You Can't Always Get What You Want" would pale without the piano and French horn at its ontset, and [umpteen other examples]. In the mid 70s such complex, background rich production was uncommon (replaced by synthesizers and tricks), and this, coupled with the band's, "strange bend" made The Tubes a standout debut. While many knew and remember the Tubes for their over the top outrageousness, there was a plethora of awesome musicians: Prairie Prince on drums, Roger Allen Steed and the incomparable Bill Spooner on guitars, and of course, Fee Waybill's lyrics and delivery were one of a kind.

Though panned by critics, The Tubes second LP, Young and Rich, was a stunning if flawed sophomore follow-up, continuing the complexities while retaining the humor. "Young and Rich," though, suffers from the plight of a performance band: it's hard to decipher the Zappa-influenced brilliance of "Tubes World Tour" amidst the dark, Waitsian tragedy in tunes like "Pimp" and "Brighter Day." Maybe it's overstimulus, too much going on at once, but the comedy is there and What Do You Want From Live would proof the pudding. Couple Young and Rich in a mixed tape with Now to piece together the real brilliance of the Band; indeed, Zappa brilliance. From off Now take "Smoke," "You’re No Fun," "My Head Is My Only House Unless it Rains" (from Captain Beefheart), "Strung Out on Strings" and "Hit Parade" and mix them up with "Pimp," "Brighter Day" and "Young and Rich" and you've got a complex album that exemplifies L.A. in the 70s: cars, cigarettes, cocaine, decadence; this is Henry Miller pop, or Bukowski - truly strung out on strings.

Though panned by critics, The Tubes second LP, Young and Rich, was a stunning if flawed sophomore follow-up, continuing the complexities while retaining the humor. "Young and Rich," though, suffers from the plight of a performance band: it's hard to decipher the Zappa-influenced brilliance of "Tubes World Tour" amidst the dark, Waitsian tragedy in tunes like "Pimp" and "Brighter Day." Maybe it's overstimulus, too much going on at once, but the comedy is there and What Do You Want From Live would proof the pudding. Couple Young and Rich in a mixed tape with Now to piece together the real brilliance of the Band; indeed, Zappa brilliance. From off Now take "Smoke," "You’re No Fun," "My Head Is My Only House Unless it Rains" (from Captain Beefheart), "Strung Out on Strings" and "Hit Parade" and mix them up with "Pimp," "Brighter Day" and "Young and Rich" and you've got a complex album that exemplifies L.A. in the 70s: cars, cigarettes, cocaine, decadence; this is Henry Miller pop, or Bukowski - truly strung out on strings.The next step, the perfect Tubesian playlist for those unfortunates who never saw them live: 1. "Haloes," 2. "Pimp," 3. "Brighter Day," 4. "Young and Rich," 5. "Space Baby," 6. "Hit Parade," 7. "My Head is My Only House When it Rains," 8. "Strung out on Strings," 9. "Boy Crazy," 10. "You’re No Fun," 11. "White Punks on Dope"

Published on August 04, 2018 06:58

August 3, 2018

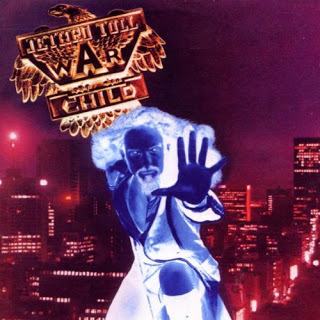

War Child and Minstrel in the Gallery - Tull

War Child is Jethro Tull's most orchestrated album, making good use of a string quartet (the Ladies in Platinum Wigs' would join them on tour over the next couple of years), so a large portion of the LP’s success is attributed to Tull's orchestral arranger - future band member David Palmer. That's not to belittle the band's contribution to the project, as here they demonstrate why they were highly respected by a range of other musicians from diverse genres. Of particular note is Martin Barre's hard edged guitar work, which erupts through the stately strings with impressive results. Again, Anderson played saxophones as well as his flutes and guitars. War Child also finds Anderson at the height of his powers as a vocalist, something for which he seems to get very little credit for.

War Child is Jethro Tull's most orchestrated album, making good use of a string quartet (the Ladies in Platinum Wigs' would join them on tour over the next couple of years), so a large portion of the LP’s success is attributed to Tull's orchestral arranger - future band member David Palmer. That's not to belittle the band's contribution to the project, as here they demonstrate why they were highly respected by a range of other musicians from diverse genres. Of particular note is Martin Barre's hard edged guitar work, which erupts through the stately strings with impressive results. Again, Anderson played saxophones as well as his flutes and guitars. War Child also finds Anderson at the height of his powers as a vocalist, something for which he seems to get very little credit for. Just a Reminder of the Chrysalis Green CassetteFor this project, Anderson's songwriting lightened somewhat since A Passion Play, which, given the fact that they deal with the same subject is intriguing. His patented sense of humor had returned as well, as songs like "Sealion" and "Bungle In The Jungle" demonstrate. Also benefiting from the injection of a sense of humor is "Two Fingers," which was the latest in a series of killer closing tracks for Tull albums. "Two Fingers" also demonstrated Anderson's ability to recycle previously discarded material, as the lyrics are largely taken from Tull's never released "Lick Your Fingers Clean" single. The arrangement and mood is quite different to the early rocking-prototype, but that doesn't prevent it being utterly superb and one of Tull's best songs. Another two tracks that were salvaged from abandoned material are "Skating Away On The Thin Ice Of A New Day" and "Only Solitaire," songs that were originally cut during the Chateau D'Isaster sessions, but put on ice in favor of A Passion Play. Again, the material was too good to be lost for any great length of time.

Just a Reminder of the Chrysalis Green CassetteFor this project, Anderson's songwriting lightened somewhat since A Passion Play, which, given the fact that they deal with the same subject is intriguing. His patented sense of humor had returned as well, as songs like "Sealion" and "Bungle In The Jungle" demonstrate. Also benefiting from the injection of a sense of humor is "Two Fingers," which was the latest in a series of killer closing tracks for Tull albums. "Two Fingers" also demonstrated Anderson's ability to recycle previously discarded material, as the lyrics are largely taken from Tull's never released "Lick Your Fingers Clean" single. The arrangement and mood is quite different to the early rocking-prototype, but that doesn't prevent it being utterly superb and one of Tull's best songs. Another two tracks that were salvaged from abandoned material are "Skating Away On The Thin Ice Of A New Day" and "Only Solitaire," songs that were originally cut during the Chateau D'Isaster sessions, but put on ice in favor of A Passion Play. Again, the material was too good to be lost for any great length of time. War Child demonstrates Tull's ability to merge genres to good effect, as evidenced on the often overlooked "The Third Hoorah" which incorporates rock, Elizabethan folk, a military marching band and classical structures. Like I said, it's heady stuff.

The reason Tull warrants continued discussion is that, unlike just about all other prog rock acts of the mid-‘70s, they were - in their businesslike, seemingly obligatory fashion - cranking out one masterful effort each year. By 1975, progressive rock was on its way to the dinosaur pit. Pink Floyd had released arguably their most cohesive and satisfying album, Wish You Were Here, but many other acts from core years were on the ropes, running out of steam or gone altogether. Yes was on hiatus, Emerson, Lake & Palmer and The Moody Blues were mere shells of their former glory, and King Crimson had called it quits. Genesis soldiered on, with Trick and Wuthering and made a string of respectable albums with Collins at the helm (and then a longer string of increasingly commercial, successful albums), though many would agree that things were not the same once Peter Gabriel rolled up his freak flag and went it alone.

All that in mind, Jethro Tull were the kings of the hill, in terms of consistency and quality, even in late '75 . The benefit of hindsight makes their proficiency, and the quality of the work, more obvious. Where some (much?) of the material from prog's heyday is decidedly of its time (for better or worse) and, lyrically, is often acknowledged with a wink and a shrug, Jethro Tull's work in general, and on Minstrel in the Gallery in particular, needs no defense nor any nostalgia to be appreciated. Minstrel has less of the sneering post-adolescent angst and rage and more of the wizened perspective of an adult who has toured the world, seen some things and is able to comment accordingly.

Discussion of Anderson's lyrical prowess is inevitable, and appropriate, and mentioned in previous reviews. Where he did not shy away from autobiographical elements (especially on Benefit), his specialty was linking the personal with a reporter's eye for both absurdity and the universal (think Aqualung); on Thick as a Brick he displayed a sociologist's eye for societal mores, and in his inimitably impish way, took his sledgehammer to all manner of very British sacred cows (class, religion, etc.); whereas on A Passion Play and War Child he used every tool in his musical and intellectual arsenal, essentially summing up all the LPs which preceded them (if arguably not as well).

On Minstrel in the Gallery, we have less of the sneering post-adolescent angst and rage and more of the wizened perspective of an adult who has toured the world, seen some things and is able to comment accordingly. The opening 8-minute-plus title cut has a minstrel-folk intro that then gives way to a classic hard rocker with some tasty guitar from Barre. Next is "Cold Wind to Valhalla," which starts out like a renaissance era folk tune but then turns into a hard but bluesy rocker (which has Barre doing both lead guitar and some great slide). Excellent use of violins in this song aid the thoughtful orchestration, just as it had done on Warchild. Who said strings and rock don't mix. Next is another classic, the epic "Black Satin Dancer" which features some hard rock riffs and the trademark Anderson folk influences. Its lyrics tell of sexual foreplay and intense longing.

The album's second side kicks off with another acoustic number called "One White Duck/0^10 = Nothing at All," s a great hook immersed in incredible musicianship. Next is the band's first 10-minute-plus track since the 1973 album-length epic A Passion Play, "Baker St. Muse." The song tells the story about a muse, a very down-to-earth fellow crying out that Jethro Tull wasn't the commercial group that War Child made them out to be. The lyrics state that we're still in the gutter singing about things that haven't changed. The other parts of the epic are stories of the street, likely stories of the "Baker St. Muse" (aka Jethro Tull). Each vignette is particularly sexual. Had they been released after 1986, they'd have a Parental Advisory label.

Published on August 03, 2018 04:23

August 2, 2018

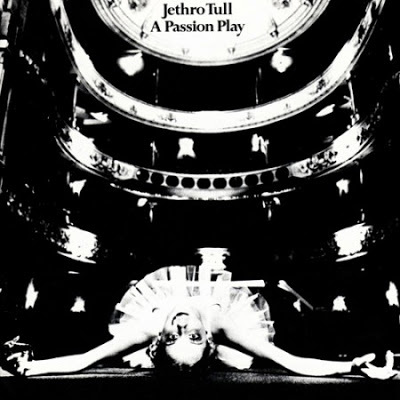

A Passion Play - Jethro Tull

Jethro Tull, hot on the heels of Thick as a Brick, quickly realized that true success in the industry meant breaking into the American market. While both Aqualung and Thick as a Brick were reasonably successful in the U.S., Tull was only just beginning to appear on the new FM AOR format. Living in the Past was a windfall idea and considered by many to be the first compilation LP. Rather than a greatest hits album, Living in the Past was a collection of songs from the early LPs, several popular U.K. singles and the No. 1 American title hit, still Tull's most successful venture into the pop radio airwaves. For a naïve ten-year old, my assumption was that this was an incredibly rich new LP, (the first that I heard from Tull), and led me to Thick as a Brick and then to A Passion Play, discovering Aqualung at a much later date. From 1969 to 1979 Jethro Tull put out at least one album each year, none of them less than very good, a handful of them great, and three of them, Aqualung, Thick as a Brick, and A Passion Play, alone merit the band's hall of fame coronation (still waiting).

Jethro Tull, hot on the heels of Thick as a Brick, quickly realized that true success in the industry meant breaking into the American market. While both Aqualung and Thick as a Brick were reasonably successful in the U.S., Tull was only just beginning to appear on the new FM AOR format. Living in the Past was a windfall idea and considered by many to be the first compilation LP. Rather than a greatest hits album, Living in the Past was a collection of songs from the early LPs, several popular U.K. singles and the No. 1 American title hit, still Tull's most successful venture into the pop radio airwaves. For a naïve ten-year old, my assumption was that this was an incredibly rich new LP, (the first that I heard from Tull), and led me to Thick as a Brick and then to A Passion Play, discovering Aqualung at a much later date. From 1969 to 1979 Jethro Tull put out at least one album each year, none of them less than very good, a handful of them great, and three of them, Aqualung, Thick as a Brick, and A Passion Play, alone merit the band's hall of fame coronation (still waiting).

Interestingly, Jethro Tull's "Holy Trinity" was recorded the same years as Yes's (The Yes Album, Fragile and Close to the Edge) and those from Genesis (Trespass, Nursery Cryme and Selling England by the Pound). Small wonder the early seventies are considered by many as the ultimate rock years. While England was immersed in the progressive sound that included Yes, Gentle Giant, ELP, ELO, Tull et al, there was also the harder edged Zeppelin, The Who and Deep Purple, even Black Sabbath, that brought the blues to a new generation and paved the way for heavy metal. There was the art rock of Bowie, Sparks and King Crimson and across the Atlantic Lou Reed and Patti Smith vying for the attention of a nation that had so fully embraced the West Coast sound of Joni Mitchell, Jackson Brown and The Eagles. The diversity is inarguable; the state of rock music at an all-time high. I understand that this paltry list omits so many greats, from Clapton to Rod Stewart to Jeff Beck, but I cannot list them all – these just came to mind.

And so, Tull's aforementioned Holy Trinity skips Living in the Past in that there was little in the way of new material, and while many would disagree with my inclusion of A Passion Play as among Jethro Tull's finest offerings, it conversely completes a trilogy that began with Aqualung. Inevitably, Jethro Tull lost some of their audience (more than a handful forever) with their follow-up to Thick as a Brick and the more challenging and, upon initial listen, less rewarding, A Passion Play. It was a shame, then, and remains regrettable, now that some folks don't have the ears or hearts (or the time) for this material, as it represents much of Anderson's finest work. His voice never sounded better, and he was at the height of his instrumental prowess: the obligatory flute, the always-impressive acoustic guitar chops and, for this album, the cheeky employment of a soprano saxophone. It's a gamble (and/or a conceit, depending upon one's perspective) that pays off in spades: a difficult, occasionally confrontational, utterly fulfilling piece of work.

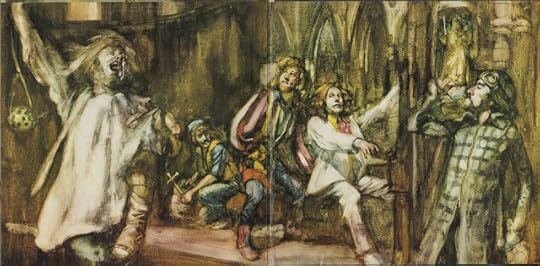

And so, Tull's aforementioned Holy Trinity skips Living in the Past in that there was little in the way of new material, and while many would disagree with my inclusion of A Passion Play as among Jethro Tull's finest offerings, it conversely completes a trilogy that began with Aqualung. Inevitably, Jethro Tull lost some of their audience (more than a handful forever) with their follow-up to Thick as a Brick and the more challenging and, upon initial listen, less rewarding, A Passion Play. It was a shame, then, and remains regrettable, now that some folks don't have the ears or hearts (or the time) for this material, as it represents much of Anderson's finest work. His voice never sounded better, and he was at the height of his instrumental prowess: the obligatory flute, the always-impressive acoustic guitar chops and, for this album, the cheeky employment of a soprano saxophone. It's a gamble (and/or a conceit, depending upon one's perspective) that pays off in spades: a difficult, occasionally confrontational, utterly fulfilling piece of work. The album's concept, designed as a stage performance, is centred on the death and afterlife of a guy called Ronnie. It's complexities are interrupted smack in the middle by a story, "The Hare Who Lost His Spectacles." Should one imagine imagine the story as a stage play, this short nonsensical Alice-like tome was meant as a break for the audience to recover a bit from the quite serious topic of the main story. The artistic performance of all band members is stunning here and the LP offers some of the best sections they've ever done during the lengthy Tull career. Of coursem, Rolling Stone hated it, though, for this writer, A Passion Play fits succinctly into the Tull masterworks trilogy.

Published on August 02, 2018 04:14

August 1, 2018

Thick as a Brick - 1972 - AM9

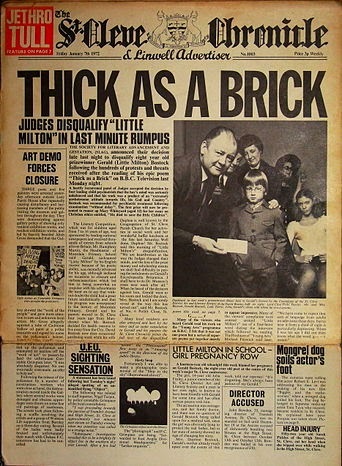

(Click Here to Read the St. Cleve Chronicle)In 1971, Jethro Tull had its biggest hit worldwide with the LP Aqualung that critics described as a concept album about religion, which Ian Anderson adamantly denied, indeed despised. Anderson decided to express his feelings about concept albums and prog-rock via parody, recording an album-length "song" called "Thick As A Brick," highlighting poetic passages that (as part of the album's concept) are put forth as the work of a precocious schoolboy who won a contest. Thick As A Brick has been slammed by haters as an example of the genre at its most excessive, while embraced by enthusiasts for the same reason. Few get the joke.

(Click Here to Read the St. Cleve Chronicle)In 1971, Jethro Tull had its biggest hit worldwide with the LP Aqualung that critics described as a concept album about religion, which Ian Anderson adamantly denied, indeed despised. Anderson decided to express his feelings about concept albums and prog-rock via parody, recording an album-length "song" called "Thick As A Brick," highlighting poetic passages that (as part of the album's concept) are put forth as the work of a precocious schoolboy who won a contest. Thick As A Brick has been slammed by haters as an example of the genre at its most excessive, while embraced by enthusiasts for the same reason. Few get the joke.The LP opens with a familiar three-minute passage that's less lumbering art-rock than folk-pop ditty. From there, the heaviness bullies its way in, yet it remains a single coherent song, not a suite or a medley. Though Anderson's word salad isn't meant to tell a story, the lyrics do cohere around a single theme, about how one shouldn't be quick to put his faith in pulp heroes or "wise men." It is, in many ways, a coming of age story. Whether campy parody or excessive self-aggrandizement, the music remains spry and fresh and retrospectively one of the most iconic pieces of the era.

The LP cover appears as a weekly, chatty small town newspaper carrying little world or national news. There are plenty of Briticisms not readily understood by American readers, and written in a manner similar to Monty Python, with irreverent references to penguins, stuffed or otherwise, and a "non-rabbit" occur often, and the crossword puzzle is wonderful. So is the connect-the-dots drawing called "Children's Corner." Here it is before filling it out:

The St. Cleve Chronicle (dated Friday, January 7, 1972) features an article on prize winning adolescent poet Gerald (Little Milton) Bostock, his prize-winning poem and the scandal surrounding his disqualification on grounds that the boy is "seriously unbalanced" and the poem is "a product of an 'extremely unwholesome attitude towards life, his God, and country.'" Accompanying the front-page story is a photo in which Little Milton's 14-year-old girlfriend (Julia Fealey) can be seen in the background slightly lifting her shirt as she stares alluringly into the camera, her legs apart just enough to reveal her underpants.

The St. Cleve Chronicle (dated Friday, January 7, 1972) features an article on prize winning adolescent poet Gerald (Little Milton) Bostock, his prize-winning poem and the scandal surrounding his disqualification on grounds that the boy is "seriously unbalanced" and the poem is "a product of an 'extremely unwholesome attitude towards life, his God, and country.'" Accompanying the front-page story is a photo in which Little Milton's 14-year-old girlfriend (Julia Fealey) can be seen in the background slightly lifting her shirt as she stares alluringly into the camera, her legs apart just enough to reveal her underpants.  Ahh, That's Why

Ahh, That's WhyFluffy is SmilingThe St. Cleve Chronicle is densely packed with references that bear upon the lyrics to Thick as a Brick. Perhaps the most important to the basic theme of the "poem" is a small story on page 5 under the headline "Visiting Prof. Gives Talk." Here we learn that a certain Andrew Jorgensen tells his listeners that "man must learn to function as an independent observer of mass-behavior and develop the right of each individual to intellectual freedom on the particular level of which he is personally capable." The story goes on: "Unfortunately the lecture was terminated by flying bottles which hit Mr. Jorgensen below the left eye."

Considering the trouble and care lavished on this bogus community newspaper, it is curious that Anderson claimed that the album is not really a concept. Anderson's point seems to be that the lyrics provide a series of glimpses into the life of the average middle-class Englishman, dealing in turn with birth, youth (including sexual awakening), school, military service, and organized religion. Nonetheless, the song hangs together around a central theme, and indeed the elaborate sleeve design plays a crucial role in the way one understands the record. During an era in which album packaging seemed in many cases to have been as creative as the music inside (or at least as interesting), Tull set a new standard with Thick as a Brick.

Published on August 01, 2018 04:10

July 31, 2018

Salvation a la Mode

In 1967, Jethro Tull began their sojourn at the Marquee Club in London. Ian Anderson recalls, "We played once at the Marquee as the John Evan Band, went back, sort of hiding our faces from John Gee the manager, and became Navy Blue the second time we played the Marquee, and the third time we played at the Marquee we were Jethro Tull, and luckily that was the one that stuck." In January '68 the band released their first the pop-folk oriented single "Sunshine Day," released on MGM under the name Jethro Toe. The name of the band, of course, was Jethro Tull, after the 18th-century English inventor of the seed drill, but the record company misspelled the name after Derek Lawrence from MGM read their name misspelled in the Melody Maker. It was on this single that Ian Anderson debuted as flute player. "I began the flute just before we came from Blackpool down to London because I sold off, in order to raise some cash and to settle some debts, I sold an electric guitar that I had. Since Mick was going to join the group on guitar it seemed pointless keeping it, so I tried to sell it for cash, but the shop wouldn't take cash; they said 'We'll let you trade it in against something,' and the only things I could think worth having that were sufficiently portable, to put in a pocket during that rough and ready existence that was to follow, were a microphone and ... as I looked round the shop, I saw a flute hanging up and thought 'I'll have that.'"

In 1967, Jethro Tull began their sojourn at the Marquee Club in London. Ian Anderson recalls, "We played once at the Marquee as the John Evan Band, went back, sort of hiding our faces from John Gee the manager, and became Navy Blue the second time we played the Marquee, and the third time we played at the Marquee we were Jethro Tull, and luckily that was the one that stuck." In January '68 the band released their first the pop-folk oriented single "Sunshine Day," released on MGM under the name Jethro Toe. The name of the band, of course, was Jethro Tull, after the 18th-century English inventor of the seed drill, but the record company misspelled the name after Derek Lawrence from MGM read their name misspelled in the Melody Maker. It was on this single that Ian Anderson debuted as flute player. "I began the flute just before we came from Blackpool down to London because I sold off, in order to raise some cash and to settle some debts, I sold an electric guitar that I had. Since Mick was going to join the group on guitar it seemed pointless keeping it, so I tried to sell it for cash, but the shop wouldn't take cash; they said 'We'll let you trade it in against something,' and the only things I could think worth having that were sufficiently portable, to put in a pocket during that rough and ready existence that was to follow, were a microphone and ... as I looked round the shop, I saw a flute hanging up and thought 'I'll have that.'" A month later the band started its Friday residency at the Marquee as Jethro Tull. The band became a fixture in London's music scene and their image, headed by Ian Anderson's emblematic figure playing flute with a leg up and dressing like a beggar, made a lasting impression on the London hip. Jethro Tull played their last gig at the Marquee in November 1968, two months after the release of their debut album This Was. The album foreshadowed Tull's eclectic mix of rock, jazz and English folk. While many bands were experimenting with classical and jazz oriented sounds, only Tull was zeroing in on what was blatantly British (a forte established by The Beatles), creating an atmosphere that summoned up the ghosts of Blake and Willy the Shake.

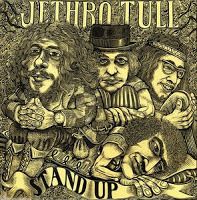

A month later the band started its Friday residency at the Marquee as Jethro Tull. The band became a fixture in London's music scene and their image, headed by Ian Anderson's emblematic figure playing flute with a leg up and dressing like a beggar, made a lasting impression on the London hip. Jethro Tull played their last gig at the Marquee in November 1968, two months after the release of their debut album This Was. The album foreshadowed Tull's eclectic mix of rock, jazz and English folk. While many bands were experimenting with classical and jazz oriented sounds, only Tull was zeroing in on what was blatantly British (a forte established by The Beatles), creating an atmosphere that summoned up the ghosts of Blake and Willy the Shake.  By Stand Up, released in August 1969, the Tull mystique was fully established, particularly with the inclusion of Bach's "Bouree." Ian Anderson's flute playing was huffy, puffy and full of breathy flourishes as he yanked out blues harmonica-like effects, with a gritty underpinning of what the flute was meant to be. It was the rock of side of fusion before jazz purists made "fusion" a dirty word.

By Stand Up, released in August 1969, the Tull mystique was fully established, particularly with the inclusion of Bach's "Bouree." Ian Anderson's flute playing was huffy, puffy and full of breathy flourishes as he yanked out blues harmonica-like effects, with a gritty underpinning of what the flute was meant to be. It was the rock of side of fusion before jazz purists made "fusion" a dirty word. Early the following year, Tull began working on what would prove to be, for many fans, the group's magnum opus, Aqualung. Anderson's writing had been moving in a more serious direction since the group's second album, but it was with Aqualung that he found the lyrical voice he'd been seeking. Suddenly, he was singing about the relationship between man and God, and the manner in which organized religion separated them. The blues influences were muted, but the hard rock passages were searing while the pastoral folk influence provided a refreshing contrast. And everybody, college prog-rock mavens and high-school time-servers alike, seemed to identify with the theme of alienation that lay behind the music. Aqualung includes the stylized liner note: "In the beginning Man created God; and in the image of Man created he him . But as all these things did come to pass, the Spirit that did cause man to create his God lived on with all men: even within Aqualung. And man saw it not. But for Christ's sake he'd better start looking." Ironically, Aqualung is one of the few Jethro Tull albums where the lyrics are not printed, despite the fact this is arguably the album where the lyrics mattereth most.

Published on July 31, 2018 15:21

July 30, 2018

Steven Wilson

I've said it time and again, the 90s, at least from a quality + quantity point of view, were a musical desert. We get Radiohead, who would produce what many feel is the greatest rock album bar none (although there's a battle royal over whether that's Kid A or OK Computer), and there was Weezer and Nine Inch Nails, and although the decade started off promising, Cobain had to go and ruin it for the rest of us. And there you have it, this writer's endless diatribe of why the 90s sucked. Yet, over time, I've warmed up to the decade, nostalgically, finally accepting into my canon The Pixies and My Bloody Valentine and, more than any other, Porcupine Tree. I only found the band accidentally one day on an 80s bent while listening to Japan's Gentlemen Take Polaroids. Having remained a great fan of David Sylvian, I ventured deeper into the audiophile quality of Japan's recordings and out of it came a new love and lust for guitarist Richard Barbieri, and from there to Porcupine Tree. The genius behind the band, Steven Wilson, is responsible for a collection of remastered progressive albums, each an audiophile's dream.

I've said it time and again, the 90s, at least from a quality + quantity point of view, were a musical desert. We get Radiohead, who would produce what many feel is the greatest rock album bar none (although there's a battle royal over whether that's Kid A or OK Computer), and there was Weezer and Nine Inch Nails, and although the decade started off promising, Cobain had to go and ruin it for the rest of us. And there you have it, this writer's endless diatribe of why the 90s sucked. Yet, over time, I've warmed up to the decade, nostalgically, finally accepting into my canon The Pixies and My Bloody Valentine and, more than any other, Porcupine Tree. I only found the band accidentally one day on an 80s bent while listening to Japan's Gentlemen Take Polaroids. Having remained a great fan of David Sylvian, I ventured deeper into the audiophile quality of Japan's recordings and out of it came a new love and lust for guitarist Richard Barbieri, and from there to Porcupine Tree. The genius behind the band, Steven Wilson, is responsible for a collection of remastered progressive albums, each an audiophile's dream.With analog recording, each generation of "dubbing down" loses fidelity. So while it sounded great before, in theory it could sound even better if the producers were able to go back to the individual tapes, transfer them to a modern, high resolution digital recording format and remix them without generational loss. This was accomplished to great effect by Wilson for artists like King Crimson, Jethro Tull, XTC and ELP. Leading his own band Porcupine Tree into the upper echelon of modern progressive rock royalty, he has clearly earned the respect of his prog forefathers due to a gift for remixes which honor the artist's original intent, intensifying the fidelity.

Close to the Edge

The best of his achievements for this writer is Yes' Close to the Edge. A 40-minute album with just three tracks—the side-long, epic and episodic title track, and a second side with two 10-minute tracks, the majestic "And You And I" and more hard-rocking but still utterly complex "Siberian Khatru"—Close to the Edge is almost over-brimming with ideas, and yet each piece feels complete, beautifully constructed and far more than the sum of its multitudinous parts. Jon Anderson's lyrics were never so oblique, his soaring voice never so pure, with an upper limit yet to be discovered. Howe's various guitars—from 12-string acoustics and pedal steel to hollow-body electric—are played with absolute precision, his solos some of the most unexpected to come from what was still considered a rock band, with the possible exception of Crimson's Fripp. Wakeman's plethora of keyboards, from multiple mellotrons to synthesizers, pianos and organs, facilitate rich underpinnings and searing solos. Bassist Chris Squire's treble-heavy Rickenbacker bass was far more than a mere anchor, instead managing to both serve that function and act as a contrapuntal foil to everything going on around him. And Bruford? One of the most recognizable snare drums in rock history, a drummer with an interest in jazz but capable of creating challenging polyrhythms, where left and right hands and feet played individual parts that coalesced into grooves of mathematical logic and precision, meeting sometimes only after many bars had passed.

And with Wilson's new mix, both in stereo and surround sound, we hear it all in crystal clarity. The immersion starts right from the get-go as you enter the album's cavernous world of chirping birds and atmospherics. It sounds as if layers of muck have been removed and in a way, they have. We are hearing here the entire album in the same fidelity as the master multi-track recordings. For the acoustic sections it' almost like sitting around a campfire, with Yes!

The Power and the Glory

The Power and the GloryThis is a classic Steven Wilson production which remains true to the sound and intent of the artists' original recording. The undulating vocals pop up around the listener, punctuating the music. Of course, the often quirky, jittery musical details fill the room. It's immersive and not particularly gimmicky. Gentle Giant's music casts a long shadow in that it's perhaps more powerful today, particularly with Wilson's guidance. This is not Gentle Giant's best LP, nor is it for beginners (with the exception of Kerry Minnear's lovely "Aspirations), and may not be the best GG starter kit. The obvious first step is the quirky Octopus, but for the long time Giant fan, what may have been pushed aside in the past, should now be one of your top choices. While I have a tendency to anthologize Gentle Giant, the Steven Wilson mastering trumps the thought and brings to life an album that in 1973 had far too little.

Nonsuch

NonsuchFeaturing sophisticated pop music with a distinctly British flair, Nonsuch is an LP worthy of a revisit and XTC at their finest. With Close to the Edge and The Power and the Glory, Wilson was hadcuffed by the primitive, if emerging, technology of its time. When Leonardo painted "The Last Supper," he was experimenting with the latest painting innovations of his era. By using an egg based tempera that was new and vibrant in its hues, Leonardo left the world a fading masterpiece doomed to time. With the recording of both LPs reviewed here, that same kind of innovation in the studio led again to a disappearance act, that, in the case of Close to Edge, was compounded by lost original master tapes. Such was not the case with 1992's Nonsuch.

The opening track, "Peter Pumpkinhead," spreads Dave Mattack's drums enormously wide, providing a massive sound, with harmonica and harmonies placed in the rear channels. Colin Moulding's bass is pronounced with a resilient grumble and warmly fills the bottom of the aural field. The surround mix of "My Bird Performs" is gently immersive with snare and tom tom drums percolating in the rear speakers. The guitars' mid tones are smooth losing the original mix's thin and overly bright sound. "Humble Daisy" takes us back to a melancholy Beach Boys vibe, with dreamy vocals placed around the room with the guitar hitting the downbeat from the front left channel and nicely plucked strings at the front right and the mellotron taking its spot centered in the rear. And all this in just the stereo mix! AM gives XTC's Skylarking an AM10, but this is the more accessible and enjoyable LP, particularly in the remaster.

Since 2009, Steven Wilson has remixed 42 classic LPs, most in the art or progressive rocks genre, though a few, like Chicago II and, most recently, Rush's A Farewell to Kings have also been adapted. Those adaptations, alongside the phenomenal remixes of the King Crimson Catalog, Jethro Tull's most important LPs and those by Gentle Giant and XTC make for a mighty line up. LPs like Yes' highly criticized Tales From Topographic Oceans are given a new life, indeed, a life they never had. Look for two new releases in the early parts of 2018, Jethro Tull's Heavy Horses and the eponymous Roxy Music debut.

Published on July 30, 2018 03:52