R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 64

July 16, 2018

Round by the Corner, Close to the Edge, Down by the River

There’s a term for being indecisive when faced with too many choices: "overchoice." Can you imagine, then, what it must have been like in the years between 1967 and 72 or 73. Close to the Edge comes out, for example, and a month later, Foxtrot.

There’s a term for being indecisive when faced with too many choices: "overchoice." Can you imagine, then, what it must have been like in the years between 1967 and 72 or 73. Close to the Edge comes out, for example, and a month later, Foxtrot. A counterpart of overchoice is an inability to actually to move on to the next plateau. How hard, for instance, it was to pry Yes off the turntable, but then, how lucky, to be privy, that very first time, to discover "Supper's Ready."

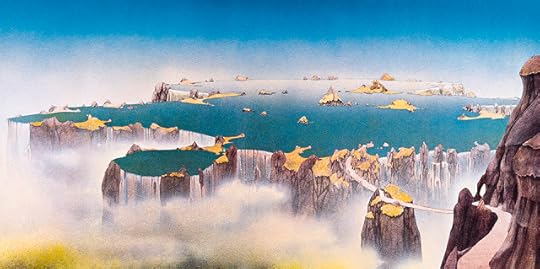

The three songs that makeup Close to the Edge, recorded over a three-week period in early 1972, reflect significant contributions from each Yes members, particularly in the title track. "Close to the Edge" was essentially recorded live in the studio with overdubs and edits made on the fly. Jon Anderson said of the process, "We'd get the basic sketch of something, and then it was a matter of refinement. A piece would start to feel complete, but then I'd look to Steve and say, 'We need a very poignant 12-string guitar introduction.' He'd come up with it, it would be great, and we'd be off." The opening track, credited to Anderson and Howe, represents four movements over 18 minutes. The lyrics, written mostly by Jon Anderson, were inspired by the Hindu/Buddhist mysticism based on the book Siddhartha, and while the piece is credited to Anderson and Howe, its plain to see that each of the members wrote or improvised their own creative niche.

The three songs that makeup Close to the Edge, recorded over a three-week period in early 1972, reflect significant contributions from each Yes members, particularly in the title track. "Close to the Edge" was essentially recorded live in the studio with overdubs and edits made on the fly. Jon Anderson said of the process, "We'd get the basic sketch of something, and then it was a matter of refinement. A piece would start to feel complete, but then I'd look to Steve and say, 'We need a very poignant 12-string guitar introduction.' He'd come up with it, it would be great, and we'd be off." The opening track, credited to Anderson and Howe, represents four movements over 18 minutes. The lyrics, written mostly by Jon Anderson, were inspired by the Hindu/Buddhist mysticism based on the book Siddhartha, and while the piece is credited to Anderson and Howe, its plain to see that each of the members wrote or improvised their own creative niche. The first section, "The Solid Time of Change," is mostly instrumental and covers numerous key and time signature changes. Howe's Gibson 335 provides a foil to Rick Wakeman's Hammond, while Bill Bruford provides a complicated interaction with Chris Squire's bass, neither satisfied with the role as percussion. (Squire's 1964 Rickenbacker 4001 is so unique, particularly here, based on his ever-present use of a pick.) Howe provides the main musical theme of the song in this section before an abrupt switch in timing and timbre as Anderson joins in.

The first section, "The Solid Time of Change," is mostly instrumental and covers numerous key and time signature changes. Howe's Gibson 335 provides a foil to Rick Wakeman's Hammond, while Bill Bruford provides a complicated interaction with Chris Squire's bass, neither satisfied with the role as percussion. (Squire's 1964 Rickenbacker 4001 is so unique, particularly here, based on his ever-present use of a pick.) Howe provides the main musical theme of the song in this section before an abrupt switch in timing and timbre as Anderson joins in.For "Total Mass Retain," the song switches mood quickly as Howe leads the band into a roiling stew amidst Bruford's tom-tom fill. Anderson and Squire sing in tandem during the section with uncanny precision. Again, the pace and key changes. Remarkably, Chris Squire plays a sliding and punctuated bass part while he and Anderson sing a vocal together in a different time signature than the music! Wakeman effortlessly integrates Moog and mellotron into the mix, the most striking aspect of the song's ethereal nature captured within the keys.

The lovely and ethereal "I Get Up, I Get Down" follows in rapid succession. Again, the pace changes as Steve Howe’s electric sitar compliments Wakeman’s Hammond organ and mellotron orchestration. The shift is dramatic and stunning. "Close to the Edge" eschews the conventions that were commonplace in prog rock epics, even by 1972 (echoed, maybe in "Supper's Ready"). Rather than choosing to welcome the listener with an overture, Yes erupt into a chaotic swirl of guitar-based jamming and synthesizer-fueled madness. When the band brings the chaos down to earth to focus on a more mainstream rock format, the melodies and symphonic warmth are refreshing, thanks to the jarring contrast. It is the prog rock equivalent to watching a Hitchcock film; the pacing is sublime.

The track is considered by many the quintessential prog rock piece. It is everything about progressive music that critics and fans alike either adore or abhor. Like "Firth of Fifth," "Tarkus," and the two-sided "A Passion Play, "Close to the Edge," while over the top and the antithesis of what many believe rock music should be, is among rock's finest moments. I would suggest instead that the "bombast" that progressive rock is accused of, particularly Yes, is apparent in everything from The Velvet Underground’s side-filling "Sister Ray" to the Allman Brothers' "Mountain Jam." So, suck it, naysayers; "Close to the Edge" is sheer brilliance.

Published on July 16, 2018 08:20

Close to the Edge (AM10)

Another of Bill's Signs - One of my father's favorites.Close to the Edge is the zenith of fantasy rock, with all the stars aligned. It's all here - power, pretension, indulgence, bombast, grandiloquence, grace, conspicuousness, beauty - blended into one daring, majestic, ridiculously beautiful LP. Antonin Dvorak, meet the Beatles. This was Yes' high watermark and their most ambitious and cohesive album. For the third record in succession, Yes proved critics wrong in their generalized assessment of the band's chosen genre as emotionless, dry and empty. 40 years on, it's as crisp as a fresh head of lettuce. And the ease in which the quintet accomplished the extreme dynamics and shifting meters is mind boggling.

Another of Bill's Signs - One of my father's favorites.Close to the Edge is the zenith of fantasy rock, with all the stars aligned. It's all here - power, pretension, indulgence, bombast, grandiloquence, grace, conspicuousness, beauty - blended into one daring, majestic, ridiculously beautiful LP. Antonin Dvorak, meet the Beatles. This was Yes' high watermark and their most ambitious and cohesive album. For the third record in succession, Yes proved critics wrong in their generalized assessment of the band's chosen genre as emotionless, dry and empty. 40 years on, it's as crisp as a fresh head of lettuce. And the ease in which the quintet accomplished the extreme dynamics and shifting meters is mind boggling. The music can be tense and unyielding one moment, cavernous and spacey the next. And not a seam showing. A novella could be written about the title track alone, which cultivates more ideas than most bands have in its career. The intro is a kinetic locomotive that dances dangerously close to jumping the tracks, followed by a tightly wound verse and a sweet yet powerful Jon Anderson vocal. Mid-way through, Anderson takes to repeating the dreamy "I get up, I get down" mantra, calming, soothing, until the skies open into a rhapsodic keyboard soliloquy by Rick Wakeman. The band reawakens, plowing into an intricate combative groove featuring another Wakeman solo that rivals his brilliant turn on Fragile's "Roundabout." But it's Steve Howe who drives this airship. His fusion of chops, innovation, and instinct contradicts any allegations of dispassionate precision. It's Howe who also takes front and center on track two, "And You and I," with his lush 12-string acoustic work. Wonderful melodies and a gradual building of mood from soft and meditative to gloriously exalted, layer upon layer, slowly adding elements of sonic complexity. "Siberian Khatru" evolves from an uncomplicated theme that expands to an apex of pointed dissonant harmonies and a double time coda of frantic but agile jamming. Top it off with Squire's inimitable fretless bass and the brilliance of Bill Bruford's drums. The album is indeed as bombastic as this article: overblown, gorgeous, compelling. The best album of a band’s canon is often called its "Sgt. Pepper." For the whole of the prog genre, the Sgt. Pepper may be Close to the Edge.

Published on July 16, 2018 04:30

July 15, 2018

Mountains come out of the sky and they stand there.

Fragile

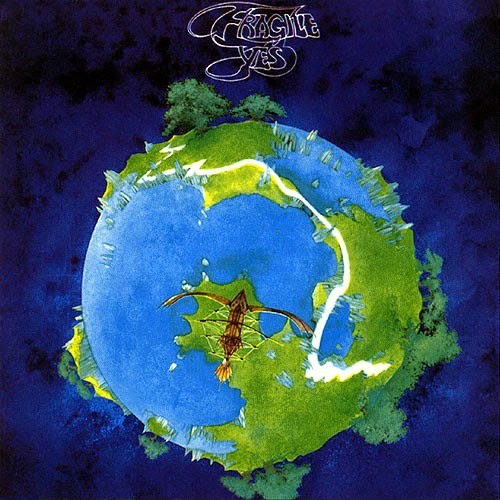

(AM9)Artist: YesRelease Date: January 4, 1972Label: AtlanticProducer: Yes, Eddie OffordLength: 39:52Tracks: 1) "Roundabout" (8:30); 2) "Cans and Brahms" (1:38); 3) "We Have Heaven" (1:40); 4) "South Side of the Sky" (8:02); 5) "Five Percent for Nothing" (0:35); 6) "Long Distance Runaround" (3:30); 7) "The Fish; Schindleria Praematurus" (2:39); 8) "Mood for a Day" (3:00); 9) "Heart of the Sunrise" (11:27)Personnel: Jon Anderson, Vocals; Steve Howe, electric and acoustic guitars; Chris Squire, bass; Rick Wakeman, Hammond organ, grand piano, RMI 368 electra-piano, harpsichord, mellotron, Moog; Bill Bruford, drums, percussion.

Fragile

(AM9)Artist: YesRelease Date: January 4, 1972Label: AtlanticProducer: Yes, Eddie OffordLength: 39:52Tracks: 1) "Roundabout" (8:30); 2) "Cans and Brahms" (1:38); 3) "We Have Heaven" (1:40); 4) "South Side of the Sky" (8:02); 5) "Five Percent for Nothing" (0:35); 6) "Long Distance Runaround" (3:30); 7) "The Fish; Schindleria Praematurus" (2:39); 8) "Mood for a Day" (3:00); 9) "Heart of the Sunrise" (11:27)Personnel: Jon Anderson, Vocals; Steve Howe, electric and acoustic guitars; Chris Squire, bass; Rick Wakeman, Hammond organ, grand piano, RMI 368 electra-piano, harpsichord, mellotron, Moog; Bill Bruford, drums, percussion.Sprawling; precise; adventurous; that otherworldly guitar of Howe, the behemoth bass of Chris Squire, Wakeman's dazzling keyboards, the jazz-inspired drumming of Bill Bruford, and that voice of Jon Anderson's; no other like it, a voice as moving as when the Whos down in Whoville sang without packages, boxes, or bags. (Nahoo Dooray!) Fragile is musical alchemy. Orchestrationally orgasmic.

Fragile contains the greatest rock hit ever written in "Roundabout;" rock not pop, AOR that made it to the top 40. The song has everything. A signature intro, hard driving riffs, unbelievable musicianship, a dramatic bridge of quiet vocal harmonies, and a landmark guitar solo to boot. In general, the Rolling Stone Top 500 list has a lack of love for Prog Rock that borders on the inexcusable, but snubbing Fragile for the likes of Labelle or, here's another one, Sleater Kenny, F-ing really? (Somebody really likes Portlandia.) Two words: SHARP! DISTANCE!

Fragile contains the greatest rock hit ever written in "Roundabout;" rock not pop, AOR that made it to the top 40. The song has everything. A signature intro, hard driving riffs, unbelievable musicianship, a dramatic bridge of quiet vocal harmonies, and a landmark guitar solo to boot. In general, the Rolling Stone Top 500 list has a lack of love for Prog Rock that borders on the inexcusable, but snubbing Fragile for the likes of Labelle or, here's another one, Sleater Kenny, F-ing really? (Somebody really likes Portlandia.) Two words: SHARP! DISTANCE!The LP contrasts five shorter individual impressions with four generally longer group collaborations. The solo works are clever but not exhaustive examples of each member's virtuosity and encompass themes from the overtly academic to the abstract and sublime, including an inspiring example of Steve Howe's musical prowess in "Mood For A Day". The four group collaborations are superbly crafted pieces that display impeccable musicianship circumscribed on exacting arrangements that ebb and flow, are at once melodious and abstruse, that surge to powerful crescendos before suddenly subsiding - an engrossing experience for the listener, particularly in its prog-lite accessibility. The Anderson vocals are lush, graceful and majestic, highlighting an increasingly metaphysical lyric base that builds on a theme of earthly and universal affiliation (like Anderson, I'm not really sure what I'm talking about). Whatever the cryptic meaning, the lyrics warrant debate. Overall Fragile has a an artistic rancor that counterpoints intense collusion, leaving the impression that the band is moving in an even more ambitious, adventurous direction, which, of course, it was.

Published on July 15, 2018 04:49

July 14, 2018

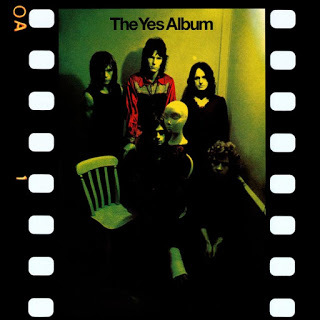

The Yes Album

Yes' incredible trilogy (The Yes Album, Fragile and Close to the Edge), almost didn't happen. Atlantic, following the dismal sales of the 2nd Yes LP, nearly dropped the band from the label. (How many of you, be honest now, have ever really heard the first two Yes LPs?) Were it not for the Yesterdays compilation, the incredible cover of Simon and Garfunkel's "America" would be obscure, even to this writer who, in his teens followed Yes around like the Grateful Dead. The first phase of Yes, the Peter Banks' Yes, was essentially a psychedelic band, a decent one, but by 1971, no one cared (in the same way that no one cared about Tull's English folk). The band was somehow able to respond to this unknown threat with the addition of Steve Howe and Jon Anderson's switching up his focus and taking the writing reigns like a boss.

Yes' incredible trilogy (The Yes Album, Fragile and Close to the Edge), almost didn't happen. Atlantic, following the dismal sales of the 2nd Yes LP, nearly dropped the band from the label. (How many of you, be honest now, have ever really heard the first two Yes LPs?) Were it not for the Yesterdays compilation, the incredible cover of Simon and Garfunkel's "America" would be obscure, even to this writer who, in his teens followed Yes around like the Grateful Dead. The first phase of Yes, the Peter Banks' Yes, was essentially a psychedelic band, a decent one, but by 1971, no one cared (in the same way that no one cared about Tull's English folk). The band was somehow able to respond to this unknown threat with the addition of Steve Howe and Jon Anderson's switching up his focus and taking the writing reigns like a boss. Howe joined an already immensely talented band, whose members each had distinctive styles, but things certainly change when the new guitarist's skillset is like nothing anyone ever heard before. I'm not one to have the "best ever" debate, Howe cannot be compared to Clapton or Townshend, or even Andre Segovia for that matter, but there was a time when Steve Howe was the most innovative and eclectic guitarist in the industry. Progressive rock gave us many incredible guitarists who studied musicians ranging from Wes Montgomery to Andrés Segovia, but Howe listened to Chet Atkins and the flatpickers and banjo players of American Appalachian music, adding the pedal steel guitar to his growing arsenal of instruments. That kind of innovation and leadership tied with Anderson's fanciful tunes was the catalyst as well for Chris Squire's ascent as one of rock's premiere bassists; arguably the musician who took the bass from out of the percussion section to have it vie for the lead.

The distinction of diverse sounds seems the key to the lineup, and one can't talk about the other band members with acknowledging an element that would not evolve later in the classic years of Yes, that of Tony Kaye's Hammond organ. Wakeman the following year would thoroughly embrace the Moog and a bevy of synthesizers, but the Hammond is integral to The Yes Album (so prevalent in "Starship Trooper).

The distinction of diverse sounds seems the key to the lineup, and one can't talk about the other band members with acknowledging an element that would not evolve later in the classic years of Yes, that of Tony Kaye's Hammond organ. Wakeman the following year would thoroughly embrace the Moog and a bevy of synthesizers, but the Hammond is integral to The Yes Album (so prevalent in "Starship Trooper). The Yes Album's, structures, even its complexities, are uncluttered and clear, despite a virtuosity of each band member that might otherwise be a sloppy stew, and while Eddie Offord's production helps here, the LP is syncopated by Bill Bruford's stunning jazz sensibility. Unlike Keith Moon who filled every available space with his patter, Bruford let the music breathe, to come up for air. He would leave the band for the far more eccentric King Crimson the following year, replaced by Alan White for the most classic Yes line up, but Bruford's subtle contributions are essential to The Yes Album sound.

After the relative tedium of their second album, Time And A Word, Yes had arrived, luckily dodging the corporate bullet. With the addition of Steve Howe, Chris Squire had the perfect foil for his bass leads and the songs were all the better for it. "Yours Is No Disgrace" is ten minutes of innovative time changes and "Starship Trooper" rocks harder than 95% of the prog-rock that isn't Crimson, and didn't "The Clap" make you want a guitar?

After the relative tedium of their second album, Time And A Word, Yes had arrived, luckily dodging the corporate bullet. With the addition of Steve Howe, Chris Squire had the perfect foil for his bass leads and the songs were all the better for it. "Yours Is No Disgrace" is ten minutes of innovative time changes and "Starship Trooper" rocks harder than 95% of the prog-rock that isn't Crimson, and didn't "The Clap" make you want a guitar? The Yes Album is an AM8.

Note: Interestingly "The Clap" is actually just called "Clap," though Jon Anderson's misstep introduction has forever retitled the tune.

Published on July 14, 2018 04:21

July 13, 2018

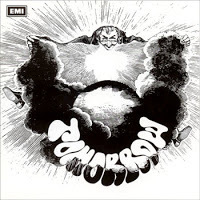

Tomorrow, Mabel Greer's Toyshop, Yes?

Clad in a cloak of psychedelic allusions, Tomorrow checks in as one of the best albums of its colorful kind. Released in February 1968, the LP rockets in with "My White Bicycle," which spins and sputters with backmasked guitars and sine wave oscillations. Its whispery vocals give the track a strange, spacey bent. Although "My White Bicycle" sports lysergically-cadenced lyrics, the opener is actually an ode to Dutch anarchists. Propelled by clanging sitars and racing rhythms, "Real Life Permanent Dream" is Tomorrow's "Incense and Peppermints." Commercial pop aspirations rise to the top on cuts like the bubbly dance hall flavored "Shy Boy" and "Auntie Mary's Dress Shop," which hops and skips along at a buoyant pace to tinkling piano fills and cheery melody lines.

Clad in a cloak of psychedelic allusions, Tomorrow checks in as one of the best albums of its colorful kind. Released in February 1968, the LP rockets in with "My White Bicycle," which spins and sputters with backmasked guitars and sine wave oscillations. Its whispery vocals give the track a strange, spacey bent. Although "My White Bicycle" sports lysergically-cadenced lyrics, the opener is actually an ode to Dutch anarchists. Propelled by clanging sitars and racing rhythms, "Real Life Permanent Dream" is Tomorrow's "Incense and Peppermints." Commercial pop aspirations rise to the top on cuts like the bubbly dance hall flavored "Shy Boy" and "Auntie Mary's Dress Shop," which hops and skips along at a buoyant pace to tinkling piano fills and cheery melody lines.

Reflections of the West Coast, like a cool collaboration of the Grateful Dead and Younger Than Yesterday-era Byrds, creep in the crevices of "Now Your Time Has Come," with its inspired improvisation and catchy earworm arrangement. The remaining tunes fritter away the moments that make up a dull day with their Pinky ambiance, eeking out a solid 40 minutes of hallucinatory fun.

Following their solitary album, Tomorrow went their separate ways with Drummer, Twink, joining the Pretty Things and guitarist, Steve Howe, eventually replacing Peter Banks in Yes.

In 1967, Tomorrow was as spacey as Pink Floyd, and along with The Soft Machine, a part of UFO's biggest draw. Coming in in the midst of the psychedelic craze, Tomorrow did it better than most, but it's hard to clearly envision the virtuoso guitars of Steve Howe as a psychedelic tool. Tomorrow is a clear AM5 on the general rubric, maybe an AM8 if one were to whittle it down to psychedelia, but I for one am thankful that the project, along with Chris Squire's stint in The Syn and Mabel Greer's Toyshop (with Jon Anderson, Bill Bruford - who answered an ad in Melody Maker - and Peter Banks) was shortlived. Are the names ringing any bells? Though Mabel Greer's Toyshop was the brainchild of Clive Bailey and Bob Hagger, sans the founding members, the remaining foursome changed their name to Yes in 1969 with Squire inviting Tony Kaye to join them shortly after. Mabel Greer's Toyshop never released an LP (until 2015!), yet they too became a staple at the Marquee and the UFO, opening for Hendrix, The Soft Machine and The Nice.

Published on July 13, 2018 10:42

The Origins of Prog

"But I don't like country." "You like the Eagles?" "Yeah." "Then you like country." It's simple to alienate people by categorizing their music in a bent with which they can't associate. Not recognizing the country and folk-rock (albeit psychedelic) aspects of bands like The Byrds, The Flying Burrito Brothers and CSN is absurd. That same kind of animosity abounds between those who do and don't appreciate progressive rock.

The mention of the term will result in blank stares that generally lead to the question, "What is progressive music?" We can generalize: Longer songs (or epics); time changes and odd time signatures; complex, sophisticated instrumentation and composition; conceptual ideas and heightened, lyrical content; classical and jazz influences. These general guidelines hold true now, as they did during prog's heyday in the mid-70s. Tracing prog's history is a bit more speculative. What may be confusing is mistaking what is avant-garde for progressive. While prog can be extremely experimental (think "We Have Heaven" from Yes or Gentle Giant's "Knots"), but I wouldn't think the utterly experimental and avant-garde Trout Mask Replica could be mistaken for progressive.

The mention of the term will result in blank stares that generally lead to the question, "What is progressive music?" We can generalize: Longer songs (or epics); time changes and odd time signatures; complex, sophisticated instrumentation and composition; conceptual ideas and heightened, lyrical content; classical and jazz influences. These general guidelines hold true now, as they did during prog's heyday in the mid-70s. Tracing prog's history is a bit more speculative. What may be confusing is mistaking what is avant-garde for progressive. While prog can be extremely experimental (think "We Have Heaven" from Yes or Gentle Giant's "Knots"), but I wouldn't think the utterly experimental and avant-garde Trout Mask Replica could be mistaken for progressive.

Picking a starting point is a bit like putting a pin in a globe to choose one's vacation. This writer sticks a pin in The Mothers of Invention's Freak Out from 1966, in particular, "Help, I'm a Rock." Zappa's sophomore release, Absolutely Free, may more specifically be progressive, but I'll stick with Freak Out as where it all began.

What appears today as run of the mill (hardly) was ground-breaking in 1967. The idea of fusing psychedelic rock with orchestral arrangements was an improbable marriage. The Moody Blues somehow made it work on the prog classic Days of Future Passed. A true concept album, Days of Future Passed is thematic in that it follows a day's activity. As "The Day Begins" Graeme Edge commands the sun to rise. The optimism of the early morning is reflected in Michael Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" and in Ray Thomas' "Another Morning". By the afternoon, the recording takes on a surreal quality typical of later psychedelic recordings; indeed, John Lodge's compositions ("Peak Hour", "Forever Afternoon") are truly inspired. Despite the "typical day," the symphonic arrangements with the London Festival Orchestra are far from ordinary. In essence, Days was a fluke, a mistake, but for scores of flower children, the LP was their first exposure to classical orchestration and soaring melodies. In actuality, the album is more proto-prog than prog: for all of its orchestral ambitions, the songs stick largely to pop song formats. And yet, the way the group tried to seriously meld themselves with the orchestra, rather than simply use it as a sweetening device as in earlier pop music, was important--it's the *intent* here that counts. Not to mention, the group's unabashedly "cosmic" aspirations which would be a more defining characteristic of prog than Zappa's more biting, punkish social satire.

What appears today as run of the mill (hardly) was ground-breaking in 1967. The idea of fusing psychedelic rock with orchestral arrangements was an improbable marriage. The Moody Blues somehow made it work on the prog classic Days of Future Passed. A true concept album, Days of Future Passed is thematic in that it follows a day's activity. As "The Day Begins" Graeme Edge commands the sun to rise. The optimism of the early morning is reflected in Michael Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" and in Ray Thomas' "Another Morning". By the afternoon, the recording takes on a surreal quality typical of later psychedelic recordings; indeed, John Lodge's compositions ("Peak Hour", "Forever Afternoon") are truly inspired. Despite the "typical day," the symphonic arrangements with the London Festival Orchestra are far from ordinary. In essence, Days was a fluke, a mistake, but for scores of flower children, the LP was their first exposure to classical orchestration and soaring melodies. In actuality, the album is more proto-prog than prog: for all of its orchestral ambitions, the songs stick largely to pop song formats. And yet, the way the group tried to seriously meld themselves with the orchestra, rather than simply use it as a sweetening device as in earlier pop music, was important--it's the *intent* here that counts. Not to mention, the group's unabashedly "cosmic" aspirations which would be a more defining characteristic of prog than Zappa's more biting, punkish social satire.

While The Moodies were busy attempting to meld rock and orchestral sounds, Keith Emerson, and The Move were busy incorporating classical and jazz elements within a tighter four-piece (later three-piece) rock band arrangement, using only his considerable virtuosity at the keyboard and a partnership with Robert Moog. The results would do more to influence prog-rock, and keyboards in general, than any other album for years to come. While "Emerlist Davjack" is more of a transitional album between psychedelia and prog, the LP is as progressive as much of ELP's later work.

Also in 1967, the Moodies were back with In Search of the Lost Chord. Here we may find the very first intrinsically progressive LP. A mini-suite opens with "House Of Four Doors," a solemn and somewhat mystical number that features the sound of different doors opening into different musical worlds: medieval guitar and flute, a baroque harpsichord, and a 19th century orchestra, leading to the fourth and final door which opens cleverly into the next song, "Legend Of A Mind." This psychedelic classic is a tribute to acid guru Tim Leary, which features a trippy mellotron hook played with a pitch bend. This upbeat track features a catchy melody and a series of exciting time changes, constantly building in strength until the piece quiets down for a mystical flute solo and more of the pitch-bended mellotron for maximum psych thrills. The break continues this mellotron/flute duet for a while, stretching the song way past pop boundaries and into solid prog territory, the track's orchestral grandeur becoming apparent as the band rejoins and gradually plays in a faster and faster tempo, soaring high until the chorus triumphantly returns. "House Of Four Doors" returns for a brief reprise, sounding moody and contemplative, a tambourine being stricken ritually as the group sings of different paths on the quest to enlightenment. And that's just side one.

Also in 1967, the Moodies were back with In Search of the Lost Chord. Here we may find the very first intrinsically progressive LP. A mini-suite opens with "House Of Four Doors," a solemn and somewhat mystical number that features the sound of different doors opening into different musical worlds: medieval guitar and flute, a baroque harpsichord, and a 19th century orchestra, leading to the fourth and final door which opens cleverly into the next song, "Legend Of A Mind." This psychedelic classic is a tribute to acid guru Tim Leary, which features a trippy mellotron hook played with a pitch bend. This upbeat track features a catchy melody and a series of exciting time changes, constantly building in strength until the piece quiets down for a mystical flute solo and more of the pitch-bended mellotron for maximum psych thrills. The break continues this mellotron/flute duet for a while, stretching the song way past pop boundaries and into solid prog territory, the track's orchestral grandeur becoming apparent as the band rejoins and gradually plays in a faster and faster tempo, soaring high until the chorus triumphantly returns. "House Of Four Doors" returns for a brief reprise, sounding moody and contemplative, a tambourine being stricken ritually as the group sings of different paths on the quest to enlightenment. And that's just side one.

By 1968 the genre would fully emerge with bands like Tomorrow, Mabel Greer's Toyshop, Yes and King Crimson. Progressive Rock would find its niche in the early 70s and explode into the mainstream in the mid-70s with Tull, ELP and Genesis, finally self-engrandizing itself so fully that it fell by the wayside amidst the clash of punk and disco. It would reemerge in the 90s with bands like Porcupine Tree. Interesting that Steven Wilson would look back so fondly on LPs like Gentle Giant's The Power and the Glory, remaster and mix them and offer them up to a new generation.

The mention of the term will result in blank stares that generally lead to the question, "What is progressive music?" We can generalize: Longer songs (or epics); time changes and odd time signatures; complex, sophisticated instrumentation and composition; conceptual ideas and heightened, lyrical content; classical and jazz influences. These general guidelines hold true now, as they did during prog's heyday in the mid-70s. Tracing prog's history is a bit more speculative. What may be confusing is mistaking what is avant-garde for progressive. While prog can be extremely experimental (think "We Have Heaven" from Yes or Gentle Giant's "Knots"), but I wouldn't think the utterly experimental and avant-garde Trout Mask Replica could be mistaken for progressive.

The mention of the term will result in blank stares that generally lead to the question, "What is progressive music?" We can generalize: Longer songs (or epics); time changes and odd time signatures; complex, sophisticated instrumentation and composition; conceptual ideas and heightened, lyrical content; classical and jazz influences. These general guidelines hold true now, as they did during prog's heyday in the mid-70s. Tracing prog's history is a bit more speculative. What may be confusing is mistaking what is avant-garde for progressive. While prog can be extremely experimental (think "We Have Heaven" from Yes or Gentle Giant's "Knots"), but I wouldn't think the utterly experimental and avant-garde Trout Mask Replica could be mistaken for progressive.Picking a starting point is a bit like putting a pin in a globe to choose one's vacation. This writer sticks a pin in The Mothers of Invention's Freak Out from 1966, in particular, "Help, I'm a Rock." Zappa's sophomore release, Absolutely Free, may more specifically be progressive, but I'll stick with Freak Out as where it all began.

What appears today as run of the mill (hardly) was ground-breaking in 1967. The idea of fusing psychedelic rock with orchestral arrangements was an improbable marriage. The Moody Blues somehow made it work on the prog classic Days of Future Passed. A true concept album, Days of Future Passed is thematic in that it follows a day's activity. As "The Day Begins" Graeme Edge commands the sun to rise. The optimism of the early morning is reflected in Michael Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" and in Ray Thomas' "Another Morning". By the afternoon, the recording takes on a surreal quality typical of later psychedelic recordings; indeed, John Lodge's compositions ("Peak Hour", "Forever Afternoon") are truly inspired. Despite the "typical day," the symphonic arrangements with the London Festival Orchestra are far from ordinary. In essence, Days was a fluke, a mistake, but for scores of flower children, the LP was their first exposure to classical orchestration and soaring melodies. In actuality, the album is more proto-prog than prog: for all of its orchestral ambitions, the songs stick largely to pop song formats. And yet, the way the group tried to seriously meld themselves with the orchestra, rather than simply use it as a sweetening device as in earlier pop music, was important--it's the *intent* here that counts. Not to mention, the group's unabashedly "cosmic" aspirations which would be a more defining characteristic of prog than Zappa's more biting, punkish social satire.

What appears today as run of the mill (hardly) was ground-breaking in 1967. The idea of fusing psychedelic rock with orchestral arrangements was an improbable marriage. The Moody Blues somehow made it work on the prog classic Days of Future Passed. A true concept album, Days of Future Passed is thematic in that it follows a day's activity. As "The Day Begins" Graeme Edge commands the sun to rise. The optimism of the early morning is reflected in Michael Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" and in Ray Thomas' "Another Morning". By the afternoon, the recording takes on a surreal quality typical of later psychedelic recordings; indeed, John Lodge's compositions ("Peak Hour", "Forever Afternoon") are truly inspired. Despite the "typical day," the symphonic arrangements with the London Festival Orchestra are far from ordinary. In essence, Days was a fluke, a mistake, but for scores of flower children, the LP was their first exposure to classical orchestration and soaring melodies. In actuality, the album is more proto-prog than prog: for all of its orchestral ambitions, the songs stick largely to pop song formats. And yet, the way the group tried to seriously meld themselves with the orchestra, rather than simply use it as a sweetening device as in earlier pop music, was important--it's the *intent* here that counts. Not to mention, the group's unabashedly "cosmic" aspirations which would be a more defining characteristic of prog than Zappa's more biting, punkish social satire. While The Moodies were busy attempting to meld rock and orchestral sounds, Keith Emerson, and The Move were busy incorporating classical and jazz elements within a tighter four-piece (later three-piece) rock band arrangement, using only his considerable virtuosity at the keyboard and a partnership with Robert Moog. The results would do more to influence prog-rock, and keyboards in general, than any other album for years to come. While "Emerlist Davjack" is more of a transitional album between psychedelia and prog, the LP is as progressive as much of ELP's later work.

Also in 1967, the Moodies were back with In Search of the Lost Chord. Here we may find the very first intrinsically progressive LP. A mini-suite opens with "House Of Four Doors," a solemn and somewhat mystical number that features the sound of different doors opening into different musical worlds: medieval guitar and flute, a baroque harpsichord, and a 19th century orchestra, leading to the fourth and final door which opens cleverly into the next song, "Legend Of A Mind." This psychedelic classic is a tribute to acid guru Tim Leary, which features a trippy mellotron hook played with a pitch bend. This upbeat track features a catchy melody and a series of exciting time changes, constantly building in strength until the piece quiets down for a mystical flute solo and more of the pitch-bended mellotron for maximum psych thrills. The break continues this mellotron/flute duet for a while, stretching the song way past pop boundaries and into solid prog territory, the track's orchestral grandeur becoming apparent as the band rejoins and gradually plays in a faster and faster tempo, soaring high until the chorus triumphantly returns. "House Of Four Doors" returns for a brief reprise, sounding moody and contemplative, a tambourine being stricken ritually as the group sings of different paths on the quest to enlightenment. And that's just side one.

Also in 1967, the Moodies were back with In Search of the Lost Chord. Here we may find the very first intrinsically progressive LP. A mini-suite opens with "House Of Four Doors," a solemn and somewhat mystical number that features the sound of different doors opening into different musical worlds: medieval guitar and flute, a baroque harpsichord, and a 19th century orchestra, leading to the fourth and final door which opens cleverly into the next song, "Legend Of A Mind." This psychedelic classic is a tribute to acid guru Tim Leary, which features a trippy mellotron hook played with a pitch bend. This upbeat track features a catchy melody and a series of exciting time changes, constantly building in strength until the piece quiets down for a mystical flute solo and more of the pitch-bended mellotron for maximum psych thrills. The break continues this mellotron/flute duet for a while, stretching the song way past pop boundaries and into solid prog territory, the track's orchestral grandeur becoming apparent as the band rejoins and gradually plays in a faster and faster tempo, soaring high until the chorus triumphantly returns. "House Of Four Doors" returns for a brief reprise, sounding moody and contemplative, a tambourine being stricken ritually as the group sings of different paths on the quest to enlightenment. And that's just side one.By 1968 the genre would fully emerge with bands like Tomorrow, Mabel Greer's Toyshop, Yes and King Crimson. Progressive Rock would find its niche in the early 70s and explode into the mainstream in the mid-70s with Tull, ELP and Genesis, finally self-engrandizing itself so fully that it fell by the wayside amidst the clash of punk and disco. It would reemerge in the 90s with bands like Porcupine Tree. Interesting that Steven Wilson would look back so fondly on LPs like Gentle Giant's The Power and the Glory, remaster and mix them and offer them up to a new generation.

Published on July 13, 2018 06:01

July 12, 2018

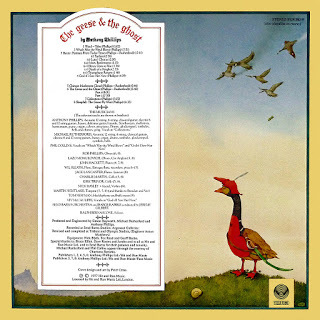

The Geese and the Ghost - Anthony Phillips - 1977

It was at the heart of the punk implosion, 1977, that Anthony Philips, guitarist for Genesis (before being replaced by Steve Hackett), released this little masterpiece. (Still my favorite three AM LP!) This concept-album is a concoction of haunting love songs with a hundred-year war backdrop during the reign of Henry VII. The result is progressive folk mingled with orchestral woodwinds straight out of medieval times. It contains long and beautiful guitar arpeggios, the hallmark of the Genesis of Trespass and Nursery Cryme. Indeed, several of the compositions were co-written as early as 1969 with Mike Rutherford, but didn't find a place in the Genesis canon. Anthony, despite the seeming snub, didn’t abandon what became a solo project, supported by his former companions of Genesis, namely Phil Collins, who sings on two tracks, and John Hackett (flute) brother of Steve.

It was at the heart of the punk implosion, 1977, that Anthony Philips, guitarist for Genesis (before being replaced by Steve Hackett), released this little masterpiece. (Still my favorite three AM LP!) This concept-album is a concoction of haunting love songs with a hundred-year war backdrop during the reign of Henry VII. The result is progressive folk mingled with orchestral woodwinds straight out of medieval times. It contains long and beautiful guitar arpeggios, the hallmark of the Genesis of Trespass and Nursery Cryme. Indeed, several of the compositions were co-written as early as 1969 with Mike Rutherford, but didn't find a place in the Genesis canon. Anthony, despite the seeming snub, didn’t abandon what became a solo project, supported by his former companions of Genesis, namely Phil Collins, who sings on two tracks, and John Hackett (flute) brother of Steve.Anthony Phillips best LP has the feel of a lost Genesis album (think Trespass crossed with Wind and Wuthering). And while not as strong as anything from Genesis' golden progressive era it's certainly recommended in between repeated plays of Nursery Cryme and Foxtrot.

Once again, I received such a positive pat on the back from our French friends with my feeble attempt to resurrect my francais, I've determined to try again (even if you are only humoring me):

Once again, I received such a positive pat on the back from our French friends with my feeble attempt to resurrect my francais, I've determined to try again (even if you are only humoring me):C'était au cœur de l'implosion punk, en 1977, que Anthony Philips, guitariste de Genesis avant d'être remplacé par Steve Hackett, sortit ce petit chef-d'œuvre. Toujours mon préféré trois am LP. Ce concept-album est basé sur l'intimité des chansons d'amour obsédantes sur un fond de guerre de cent ans à l'époque de Henri VII. Il en résulte un ensemble de Folks progressistes mêlés à des vents orchestraux. Il contient de longs arpèges de guitare, la marque de la genèse de l'intrusion et de la pépinière Cryme. En effet, plusieurs des compositions ont été co-écrites dès 1969 avec Mike Rutherford, mais n'a pas trouvé place dans le Canon Genesis. Anthony, en dépit de l'apparence snob, n'a pas abandonné ce qui est devenu un projet solo, soutenu par ses anciens compagnons de la Genèse, à savoir Phil Collins, qui chante sur deux pistes, et John Hackett (flûte) frère de Steve.

Avec des voix d'invité de Phil Collins, de fortes contributions de Mike Rutherford, et des lavages de guitare de 12 cordes ce premier album solo pastoral du guitariste original de Genesis Anthony Phillips a la sensation d'un album de Genesis perdu (pensez intrusion croisée avec le vent et Hurlevent). Et pas aussi forte que n'importe quoi de la Genèse'Golden progressive Era il est certainement recommandé aux fans de ce genre à écouter entre les pièces répétées de pépinière Cryme et Foxtrot.

Published on July 12, 2018 06:24

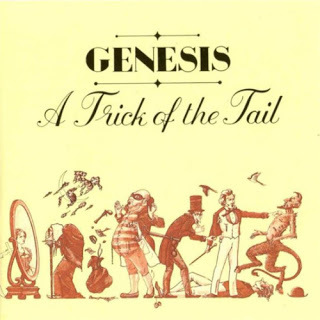

A Trick of the Tail

Trick of the Tail, by far the best of the post Peter Gabriel Genesis LPs, is a forgotten classic. Makes not sense. As immense as Gabriel was, he demanded control over Genesis songwriting, particularly with Lamb. As a result, the first LP sans Peter - where they were clearly under enormous pressure to prove that they could survive without him - ended up a songwriters' and instrumentalists' clinic, essentially with four George Harrisons (I'm thinking about the exceptional solo effort All Things Must Pass, of course, which, were it whittle down to two disks, would rival anything in the Beatles' canon). Tony Banks's songwriting, Mike Rutherford's and Steve Hackett's guitar, and Phil Collins' vocals and drumming get a great workout here, and there isn't a clinker in the bunch. "Squonk," "Dance on a Volcano," and "Entangled" are the clear winners, though Banks's keyboards shine on "Ripples" and "Mad Man Moon." Only "Robbery, Assault & Battery" ever strikes me as a bit dated or campy - but it's strong enough instrumentally to overcome the somewhat forced lyrics, and essentially mimics Gabriel's offhand ditties on PG1, with the new Gen beating him to the punch.

Trick of the Tail, by far the best of the post Peter Gabriel Genesis LPs, is a forgotten classic. Makes not sense. As immense as Gabriel was, he demanded control over Genesis songwriting, particularly with Lamb. As a result, the first LP sans Peter - where they were clearly under enormous pressure to prove that they could survive without him - ended up a songwriters' and instrumentalists' clinic, essentially with four George Harrisons (I'm thinking about the exceptional solo effort All Things Must Pass, of course, which, were it whittle down to two disks, would rival anything in the Beatles' canon). Tony Banks's songwriting, Mike Rutherford's and Steve Hackett's guitar, and Phil Collins' vocals and drumming get a great workout here, and there isn't a clinker in the bunch. "Squonk," "Dance on a Volcano," and "Entangled" are the clear winners, though Banks's keyboards shine on "Ripples" and "Mad Man Moon." Only "Robbery, Assault & Battery" ever strikes me as a bit dated or campy - but it's strong enough instrumentally to overcome the somewhat forced lyrics, and essentially mimics Gabriel's offhand ditties on PG1, with the new Gen beating him to the punch.

Trick's production is far, far better than that of The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. The sound quality is so superior that a good many, if not all, of the songs sound as if they could be released today, while many tracks on Lamb are stuck in the 70's. This timelessness is enhanced by Banks' choice to use good old-fashioned piano rather than dated 70's synths. Indeed, the simplistic piano melody that accompanies "Mad Man Moon" is nothing less than (dare I say it?) a master stroke of the highly underrated keyboard player. A Trick of the Tail is also the boldest and most successful of Genesis's post-Gabriel excursions into long-form composition. With all its funny meters, tempo changes, weird chord changes, oddball guitar tunings, medleys - all of the hallmarks of the Gabriel era (it is as Trespass-y as New Order's Movement is Joy Division-esque). Banks and Hackett stand out in a way that wasn't possible with Gabriel. The departure of Gabriel sent many a proghead into deep, deep depression, and overnight turned Genesis, at one time considered the most influential progressive rock band to emerge from England, into a critical colony of lepers. Yet when the smoke cleared, and cooler heads prevailed, it was discovered that , shit, the music retained the depth and musical complexity Genesis had been known for all along. Anyone born after 1975 might find this impossible to believe, but the 80’s Grammy-grabbing Disney schlockmeister, Collins, actually used to be very cool. Concurrent to his excellent drumming and later vocal work with serious symphonic proggers Genesis, Collins played with serious fusioners Brand X, and remained in demand by people like Brian Eno for his services.

Trick and Wind and Wuthering, were the last truly progressive studio albums by the band before the departure of Steve Hackett, and their subsequent pop stardom. The inevitable collapse of prog rock was indeed delayed at least by the new Gen. Pick this one up long before Abacab and the later nonsense, and even before Trespass and, dare I say it, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (Indeed, without "Humdrum," it out shines PG1 by far).

Published on July 12, 2018 05:03

July 11, 2018

The path is clear, though no eyes can see. The course laid down, loooong before! - Firth of Fifth - Genesis

Bank Note SouvenirWhat has been stuck in my head for a weeks now, ever since my daughter's bango teacher played me an acoustic version on his beautiful Ibanez is "Firth of Fifth," arguably the greatest 9½ minutes of music that Genesis ever made (it vies for the finest prog piece of all), making Selling England by the Pound a solid AM9. While often compared to ELP's "Tarkus" or Yes' "Close to the Edge," "Firth of Fifth's" structure is far less chaotic and a bit easier on the ears; no abrupt key changes or flippant new meters here. It also delivers (here much more like "Close to the Edge"), a crisp clean sound of which Emerson rarely indulged due to his affinity for the Hammond organ with its murky undertones. Tony Kaye's piece relies on its clean tenor, avoiding the distorted timbre of ELP, Tull or the Yes of "Starship Trooper." The same can be said for Steve Hackett's muted fuzztone giving a warm, comforting feel to it all.

Bank Note SouvenirWhat has been stuck in my head for a weeks now, ever since my daughter's bango teacher played me an acoustic version on his beautiful Ibanez is "Firth of Fifth," arguably the greatest 9½ minutes of music that Genesis ever made (it vies for the finest prog piece of all), making Selling England by the Pound a solid AM9. While often compared to ELP's "Tarkus" or Yes' "Close to the Edge," "Firth of Fifth's" structure is far less chaotic and a bit easier on the ears; no abrupt key changes or flippant new meters here. It also delivers (here much more like "Close to the Edge"), a crisp clean sound of which Emerson rarely indulged due to his affinity for the Hammond organ with its murky undertones. Tony Kaye's piece relies on its clean tenor, avoiding the distorted timbre of ELP, Tull or the Yes of "Starship Trooper." The same can be said for Steve Hackett's muted fuzztone giving a warm, comforting feel to it all.

While the song relies most heavily on Kaye's piano intro, one of the most famous in prog, the lengthy piece allows each of the musicians the opportunity to harmoniously contribute: Kaye's luscious display of keyboards, Gabriel's perfect lyrical delivery and flute, Collins' syncopated jazz beat, Mike Rutherford's underrated bass and Hackett's subtle guitar.

Of the epic piece, Steve Hackett said, "It's the same melody played three times with minimal variation. It's done like jazz, with the statement of the theme then you go off and improvise, and then return to the theme. On 'Firth of Fifth,' when it comes back, it's a larger arrangement. It's the tune as written, then 'let's take this to the mountains,' to a certain extent. I was playing it on electric guitar, then it struck me that it had certain similarities with other melodies that I had been playing that I liked. It ended up with aspects of Eric Satie, and aspects of King Crimson. The song had an aspect of blues, an aspect of gospel about it. It had something of English church music – but it also had an aspect of something Oriental or Indian, almost. So, it was a fusion of influences. But at the time, we weren't using the word fusion and we were using the word progressive. It would eventually be described as progressive, which was a catch all phase covering an awful lot of bases."

The Firth (River) of ForthIn Robert Macan's book Rocking the Classics, he describes the structure of "Firth of Fifth" as resembling "an arch form" (A B C A C B A). He simplifies it by referring to it as a sonata. The A section is a lengthy instrumental overture; the B section an "exposition," which contains the verses; and the C section is the instrumental "development," which contains a new theme. This section then returns and develops the A and C themes, before section B returns as the "recapitulation," and concluding with an instrumental coda that heavily borrows from the A section. OK, so I don't portend to fully grasp his introspection, but reaching back into my music theory days, I see it as the perfect mountainscape (thanks to Steve Hackett for the imagery), rising, falling, rising a bit further, falling, again rising, less this time, then back to whence we came, like a novel by Steinbeck that ends where it started; though you as the reader, as the listener, are different.

The Firth (River) of ForthIn Robert Macan's book Rocking the Classics, he describes the structure of "Firth of Fifth" as resembling "an arch form" (A B C A C B A). He simplifies it by referring to it as a sonata. The A section is a lengthy instrumental overture; the B section an "exposition," which contains the verses; and the C section is the instrumental "development," which contains a new theme. This section then returns and develops the A and C themes, before section B returns as the "recapitulation," and concluding with an instrumental coda that heavily borrows from the A section. OK, so I don't portend to fully grasp his introspection, but reaching back into my music theory days, I see it as the perfect mountainscape (thanks to Steve Hackett for the imagery), rising, falling, rising a bit further, falling, again rising, less this time, then back to whence we came, like a novel by Steinbeck that ends where it started; though you as the reader, as the listener, are different.While the piece's piano intro is among the most iconic in progressive rock, Hackett's solo is incredible, mostly because he picks a spine-tingling, beautiful guitar tone, a slightly psychedelic, highly sustained, highly lyrical one that's oddly creepy, like those heard all over The Court of the Crimson King - and he just lets it rip for several minutes, ironically like a gorgeous sorrow. My only gripe has always been, and this is merely a production decision aesthetically, the brevity of the piano's coda at the track's end.

Published on July 11, 2018 04:46

July 10, 2018

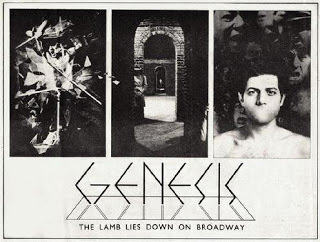

The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

The following notes are from the original souvenir program of The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway Tour in 1974, which began in November at the Auditorium Theater in Chicago and ran through May of the next year, closing with The Palais de Sports in Besançon, France (with a final cancelled show in Toulous). (I was fortunate enough to see the show at the Shrine Auditorium in L. A. in January 1975.) Like The Beatles (The White Album), a double album of similar stature, I first thought The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway was too scattered and inconsistent, especially after Selling England by the Pound. These days, I enjoy it because of its variance in sound: there is simply no denying the spectacular melodies present here throughout, even if the album drags a bit here and there. The first half of the album is nearly flawless, and while there are moments of doubt in the second half, it remains an essential piece of the classic-era progressive rock Genesis.

The following notes are from the original souvenir program of The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway Tour in 1974, which began in November at the Auditorium Theater in Chicago and ran through May of the next year, closing with The Palais de Sports in Besançon, France (with a final cancelled show in Toulous). (I was fortunate enough to see the show at the Shrine Auditorium in L. A. in January 1975.) Like The Beatles (The White Album), a double album of similar stature, I first thought The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway was too scattered and inconsistent, especially after Selling England by the Pound. These days, I enjoy it because of its variance in sound: there is simply no denying the spectacular melodies present here throughout, even if the album drags a bit here and there. The first half of the album is nearly flawless, and while there are moments of doubt in the second half, it remains an essential piece of the classic-era progressive rock Genesis.

PETER: Several ideas for the album were presented in order for the band to exercise a democratic vote. I knew mine was the strongest and I knew it would win - or, I knew that I could get it to win. The only other idea that was seriously considered was The Little Prince which Mike was in favour of - a kid’s story. I thought that was too twee. This was 1974; it was pre-punk but I still thought we needed to base the story around a contemporary figure rather than a fantasy creation. We were beginning to get into the era of the big, fat supergroups of the seventies and I thought, “I don’t want to go down with this Titanic”. Once the story idea had been accepted we had all these heavy arguments about writing the lyrics. My argument was that there aren’t many novels which are written by a committee. I said, “I think this is something that only I’m going to be able to get into, in terms of understanding the characters and the situations”. I wrote indirectly about lots of my emotional experiences in The Lamb and so I didn’t want other people coloring it. In fact there are parts of it which are almost indecipherable and very difficult which I don’t think are very successful. In some ways it was quite a traditional concept album - it was a type of Pilgrim’s Progress but with this street character in leather jacket and jeans. Rael would have been called a punk at that time without all the post-‘76 connotations. The Ramones hadn’t started then, although the New York Dolls had, but they were more glam-punk. The Lamb was looking towards West Side Story as a starting point.

MIKE: It was about a greasy Puerto Rican kid! For once we were writing about subject matter which was neither airy-fairy, nor romantic. We finally managed to get away from writing about unearthly things which I think helped the album.

TONY: All the lyrics were written by Peter, apart from one or two tracks, because he’d thought up the story line. He didn’t really want anyone else to do it. We also had a lot of work to do, because we had decided by that time that we were going to make a double album. This meant there was a division as Pete went off and wrote the lyrics, and everyone else wrote the music. By the time Pete had finished the lyrics, there were about two or three holes where there wasn’t a song, and we needed to write something. “Carpet Crawlers” was one and “The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging” was another.

PHIL: We were living at Headley Grange - this house that Led Zeppelin, Bad Company and the Pretty Things had lived in. it was a bit of a shambles - in fact they’d ripped the shit out of it. We were all living together and writing together and it went very well to start with. Pete had said he wanted to do all the words so Mike and Tony had backed off and we were merrily churning out this music. Every time we sat down and played, something good came out.

PETER: Around the time we started work on The Lamb I had this call from Hollywood by William Friedkin who’d seen the story I’d written on the back of the live album and he thought it indicated a weird, visual mind. He was trying to put together a sci-fi film and he wanted to get a writer who’d never been involved with Hollywood before. We were working at Headley Grange which I felt was partly haunted by Jimmy Page’s black magic experiments, and was full of rock and roll legend. I would go bicycle to the phone box down the hill and dial Friedkin in California with pockets stuffed full of 10p pieces.

PETER: Around the time we started work on The Lamb I had this call from Hollywood by William Friedkin who’d seen the story I’d written on the back of the live album and he thought it indicated a weird, visual mind. He was trying to put together a sci-fi film and he wanted to get a writer who’d never been involved with Hollywood before. We were working at Headley Grange which I felt was partly haunted by Jimmy Page’s black magic experiments, and was full of rock and roll legend. I would go bicycle to the phone box down the hill and dial Friedkin in California with pockets stuffed full of 10p pieces.

PHIL: Suddenly Peter came up and said, “Do you mind if we stop for a bit”, and we all said, “No. Of course we don’t want to stop.” It was a matter of principle more than anything else. So he said, “OK, I want to do the film, so I’m leaving.” I remember we were sitting in the garden by the porch saying “What are we going to do? We’ll carry on. We’ll have an instrumental group”, which for about five seconds was a serious idea because we had a lot of music written.

TONY: We were just going to carry on. We were going to write another story line. Not that I wanted Pete to leave because he was a very strong contributor and I really enjoyed working with him. I felt that the group needed all the energy we could possibly put into it because we still have a long way to go career-wise, and I thought musically it was still very interesting. If you are going to do it properly there’s no way that one person can suddenly go off like that leaving the rest to hang about for three months. We made that very clear and that’s why he left. It was all getting a little tedious, because the group was very much the main thing in our lives at that particular time. Peter kept saying if this William Friedkin offer came, he would do that in preference to working with us. And I thought, “This is absurd”. There came a point when he decided to write a screen play, so he left for a bit. Anyhow, higher authorities stepped in - I think it was Strat - to try and keep us together. So Peter made a definite commitment to finish the album before he did anything else. But I think it made all of us feel that he was getting fed up and it was only a matter of time before he left.

Published on July 10, 2018 04:33