R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 63

July 22, 2018

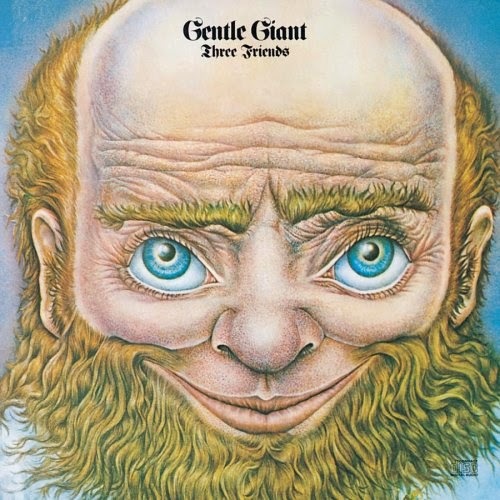

A Brief History of the Gentle Giant

Woe to the musician who can actually play his or her instrument. In that direction ridicule lies, or so the three chord purist would have you believe. In this regard: consider the plight of Gentle Giant, among the most reviled of prog-rock outfits from the 70s. So sorry, purists, I'm calling bullshit. Reality is, 4/4 time gets pretty boring pretty quickly; counterpoint is challenging and aesthetically pleasing to the ears, music with texture and complex instrumentation is far more interesting then the bland purist backbeat (think Please Please Me Vs. Sgt. Pepper).

Woe to the musician who can actually play his or her instrument. In that direction ridicule lies, or so the three chord purist would have you believe. In this regard: consider the plight of Gentle Giant, among the most reviled of prog-rock outfits from the 70s. So sorry, purists, I'm calling bullshit. Reality is, 4/4 time gets pretty boring pretty quickly; counterpoint is challenging and aesthetically pleasing to the ears, music with texture and complex instrumentation is far more interesting then the bland purist backbeat (think Please Please Me Vs. Sgt. Pepper).

Gentle Giant, founded by three brothers with a Glasgow Blues background (yeah, it's a thing), succeeded in a daring fusion of jazz, classical and rock. The strength of the sextet was Kerry Minnear's keyboards (Minnear had a degree in music from the Royal Academy), the guitar virtuosity of Gary Green (a blues veteran) and Phil Schulman’s rococo woodwinds, with each member a multi-instrumentalist. Besides the complex scores, their sound was light years removed from even the most progressive or fusion oriented bands, particularly Derek Schulman's nearly inhuman (giant) vocals, so aseptic they more resembled conservatory solfeggios and Gregorian chant. This wasn't rock; it was some other medieval concoction.

The first album, Gentle Giant (AM5, Vertigo, 1970), only points to who they would or could become with the dissonant counterpoint, the nearly eponymous peculiarity that made them renowned not materializing until Acquiring The Taste (AM6, Vertigo Records, 1971). Each Giant played a miscellany of instruments with massive use of keyboards lending a symphonic quality to the album. Kerry Minnear's role included electric piano, organ, mellotron, vibraphone, synthesizer, celesta, harpsichord and vocals, while bassist Ray Schulman added violin and viola, and Tony Visconti, David Bowie's producer, added flute. There are typanis, skulls, claves, recorders, jawbones and cowbells. Acquiring the Taste is exactly that, a veritable taste of complex honey.

Three Friends (AM 7, Columbia, 1972), essentially a "rock opera," contains six long ballads with "Mister Class And Quality" and "Working All Day" the most accessible. "Prologue," "Schooldays" and "Peel The Paint" were like cryptic chamber-music. The harder-edged Octopus (AM8, Columbia, 1972), with the exception of "Think of Me With Kindness," is almost dauntingly complex, with counterpoint and opposing melodies riddled with dead air and aural or negative space, the rest as intoxicating as the note. Generally it's more math-rock, Bach-rock than art-rock in which each instrumental passage is layered and interwoven and complete unto itself. In particular, the vocal harmonies of Knots, inspired by psychologist RD Laing's enigmatic poems (?), were an antithesis to the British tradition both musically and thematically, and the clumsy "Dog's Life," is an eccentric paean to giant's best friend.

In A Glass House (AM8, Vertigo/WWA, 1973 - not initially released in the US), another concept album, is probably their most ambitious work. The exuberant experimentation took particular advantage of Phil Schulman’s departure from the band earlier in the year. The socio-political concept, The Power And The Glory (AM7, Capitol, 1974) is less ambitious yet still fluid and classy and possibly their roughest edge, tempered only by Kerry Minnear's beautiful "Aspirations."

Free Hand (AM8, Capitol, 1975) is Gentle Giant’s "medieval" album. Nearly all the songs ("Just The Same," "On Reflection," "Free Hand," "Time To Kill," "His Last Voyage") reached a formal perfection in their attempt at reinventing the rock song.

And then it was over. Record company pressures, a changing listenership, a new sense that progressive rock was not only passe but that it had done a disservice, led to albums that didn't make sense except as contractual obligations. Part jazz-rock, part folk, part medieval polyphony or renaissance dance music, Gentle Giant was a crazy hybrid of music that shouldn't have worked on any level, but instead, in perfect counterpoint, worked on them all.

Published on July 22, 2018 04:07

July 21, 2018

The Yes Solo LPs

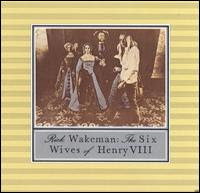

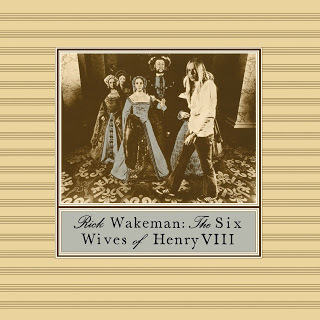

Following the tour that accompanied Relayer, the five current members of Yes '76 each released a solo LP (though the trend began before the departure of Rick Wakeman in 1974 with the aforementioned Six Wives of Henry VIII, the best of the Yes solo efforts. Wakeman would follow it up with the equally successful live LP, Journey to the Centre of the Earth.) Patrick Moraz was the first of the new line up to release a solo, The Story of I, in June 1976 (it was not his first solo release). The Story of I was a fusion of progressive rock and world music remarkably ahead of its time.

Following the tour that accompanied Relayer, the five current members of Yes '76 each released a solo LP (though the trend began before the departure of Rick Wakeman in 1974 with the aforementioned Six Wives of Henry VIII, the best of the Yes solo efforts. Wakeman would follow it up with the equally successful live LP, Journey to the Centre of the Earth.) Patrick Moraz was the first of the new line up to release a solo, The Story of I, in June 1976 (it was not his first solo release). The Story of I was a fusion of progressive rock and world music remarkably ahead of its time. Alan White's LP Ramshackled was released at about the same time. Though better than critics and fans alike gave it credit, the album sold poorly. The lack of a progressive slant and an odd mix of musical styles was poorly received. One song, though, with Jon Anderson in the vocal lead, is a beautiful and haunting track. The song, a William Blake poem called "Spring-Song of Innocence," was set to music by guitarist Peter Kirtley and could easily have fit Anderson's own solo effort Olias of Sunhillow.

We've learned over the years that a little Jon Anderson outside of Yes goes a loooong way, particularly if we're not on the same spiritual wavelength, but this album stands up after more than 40 years. The science-fiction fantasy, while quaint, is secondary to the layered vocal harmonies, swirling keyboard and acoustic-laden melodies. It makes for a heady, intoxicating listen, and a great example of what progressive means in the right hands. Olias of Sunhillow was a true example of a solo effort, with Anderson playing all the instruments.

We've learned over the years that a little Jon Anderson outside of Yes goes a loooong way, particularly if we're not on the same spiritual wavelength, but this album stands up after more than 40 years. The science-fiction fantasy, while quaint, is secondary to the layered vocal harmonies, swirling keyboard and acoustic-laden melodies. It makes for a heady, intoxicating listen, and a great example of what progressive means in the right hands. Olias of Sunhillow was a true example of a solo effort, with Anderson playing all the instruments. Squire's Fish Out of Water was another excellent entry into the prog canon and a unique opportunity to enjoy a true bass virtuoso. Squire's playing is impeccable on the 5 songs here, with able support from Patrick Moraz and Bill Bruford. Squire makes a courageous stab at the vocals, which somehow work, despite the questionable frontman stance. Real prog aficionados look to this as the best of the Yes solos. It is clearly the most accessible release excluding Wakeman's.

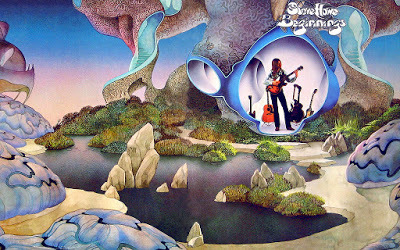

Finally, there's the guitarist's guitarist Steve Howe's effort (speaking of shaky vocals), Beginnings. The best thing about the first batch of Yes solo albums was that they allowed us to peer into the Yes compositional process. We could glimpse each of Yes' primary composers by themselves – as a prism separates light into colors. Howe's first album holds up over time with an energy and brashness that is rather stunning. One would have thought that here was the iconoclastic confounder of the Yes Stable, while instead, Howe proves a traditional songsmith. His voice, while appallingly bad, worthy of Yes backups and little more, is "forgivable" though one can imagine how exceptional the album would have been had Jon handled the vocals.

Finally, there's the guitarist's guitarist Steve Howe's effort (speaking of shaky vocals), Beginnings. The best thing about the first batch of Yes solo albums was that they allowed us to peer into the Yes compositional process. We could glimpse each of Yes' primary composers by themselves – as a prism separates light into colors. Howe's first album holds up over time with an energy and brashness that is rather stunning. One would have thought that here was the iconoclastic confounder of the Yes Stable, while instead, Howe proves a traditional songsmith. His voice, while appallingly bad, worthy of Yes backups and little more, is "forgivable" though one can imagine how exceptional the album would have been had Jon handled the vocals.

Published on July 21, 2018 04:30

July 20, 2018

Relayer Comments

My comment that I would "go out on a limb" to state that Relayer was Yes' penultimate LP sparked a bevy of email; one that said, "You haven't gone out on a limb, you've fallen out of a tree." Another implied that my post "crumbled" the subjective nature of AM's purpose, that of being objective. Both (and there were others less kind), are fair. Readers questioned how Relayer could possibly be better than The Yes Album or Fragile. Noted. The post was indeed emotional rather than objective, and yet I stand by the notion that Relayer is a Yes highpoint and the one Yes LP that rocks like a caveman. That emotionalism may subside and I will "come to my senses, man," as one reader pleaded, but after sitting through Tales and then thoroughly enjoying Relayer in succession, one may see my point. Others of you commented on my negative statements about Rick Wakeman. Though I stand by them, they were pointedly focused on Tales and not on Wakeman, the real Wakeman, and not the one who found more interest in Indian Take Out than his job, you know, as Rock's Gandalf.

My comment that I would "go out on a limb" to state that Relayer was Yes' penultimate LP sparked a bevy of email; one that said, "You haven't gone out on a limb, you've fallen out of a tree." Another implied that my post "crumbled" the subjective nature of AM's purpose, that of being objective. Both (and there were others less kind), are fair. Readers questioned how Relayer could possibly be better than The Yes Album or Fragile. Noted. The post was indeed emotional rather than objective, and yet I stand by the notion that Relayer is a Yes highpoint and the one Yes LP that rocks like a caveman. That emotionalism may subside and I will "come to my senses, man," as one reader pleaded, but after sitting through Tales and then thoroughly enjoying Relayer in succession, one may see my point. Others of you commented on my negative statements about Rick Wakeman. Though I stand by them, they were pointedly focused on Tales and not on Wakeman, the real Wakeman, and not the one who found more interest in Indian Take Out than his job, you know, as Rock's Gandalf.I will mention, though, that the poem on the gatefold of the LP is just plain dumb.

Published on July 20, 2018 04:47

July 19, 2018

CHA CHA CHAA CHA CHA!

It's time to go out on a limb (as we beat this Yes thing to death), and you can quote me on this - if you ever find yourself interviewing me for some bizarre reason: Relayer is the second best Yes album. We all know that Close to the Edge is number one, and most folks agree that Fragile is right there behind it; but not me. I mean at 13, "We Have Heaven" was just so out there and frankly the girls didn't care for Yes, but they liked that you did, and Fragile had "Roundabout," the one song they were into. But forty years on it's no longer about girls but about Patrick Fucking Moraz! Wakeman quit the band because he felt that Tales was out of hand and Yes, who effectively killed the genre with that four sided bombastic journey, recouped and hooked up with a Swiss jazzman into some heavy, hardcore fusion. None of that hippy dippy, mellotron smellotron shit for him, no sir, he was gonna patch in the most jarring synths he had and let 'em rip. What we end up with is the least characteristic Yes album since the The Yes Album.

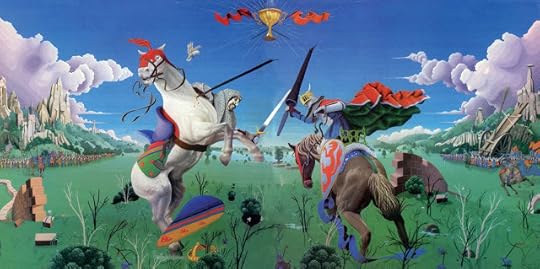

It's time to go out on a limb (as we beat this Yes thing to death), and you can quote me on this - if you ever find yourself interviewing me for some bizarre reason: Relayer is the second best Yes album. We all know that Close to the Edge is number one, and most folks agree that Fragile is right there behind it; but not me. I mean at 13, "We Have Heaven" was just so out there and frankly the girls didn't care for Yes, but they liked that you did, and Fragile had "Roundabout," the one song they were into. But forty years on it's no longer about girls but about Patrick Fucking Moraz! Wakeman quit the band because he felt that Tales was out of hand and Yes, who effectively killed the genre with that four sided bombastic journey, recouped and hooked up with a Swiss jazzman into some heavy, hardcore fusion. None of that hippy dippy, mellotron smellotron shit for him, no sir, he was gonna patch in the most jarring synths he had and let 'em rip. What we end up with is the least characteristic Yes album since the The Yes Album.  "The Gates of Delirium" demolishes all memory of Siddartha and Yogananda and gets us right back to something that, quality-wise, is as good as anything from '71-'72 era Yes. And this shit is violent. Violent, that’s the word for it. Anderson sounds deranged, leading his imaginary troops into a vicious, bloody battle that's depicted in a lengthy instrumental break where keyboards and guitars crash into one another and come spiraling down to saw your brain in half. It really is jaw-dropping, especially to hear it from a bunch of guys who just an album ago sounded like they were hippies who showed up at the party a couple years too late. Then the third part rolls around, and if they haven't gotten you then, the magnificent desolation on display will. That's the aftermath. You know, when a small band of surviving soldiers wanders about the carnage and blood and corpses and asks themselves what was the point of it all. It blows my socks off.

"The Gates of Delirium" demolishes all memory of Siddartha and Yogananda and gets us right back to something that, quality-wise, is as good as anything from '71-'72 era Yes. And this shit is violent. Violent, that’s the word for it. Anderson sounds deranged, leading his imaginary troops into a vicious, bloody battle that's depicted in a lengthy instrumental break where keyboards and guitars crash into one another and come spiraling down to saw your brain in half. It really is jaw-dropping, especially to hear it from a bunch of guys who just an album ago sounded like they were hippies who showed up at the party a couple years too late. Then the third part rolls around, and if they haven't gotten you then, the magnificent desolation on display will. That's the aftermath. You know, when a small band of surviving soldiers wanders about the carnage and blood and corpses and asks themselves what was the point of it all. It blows my socks off.

I am sockless through "Sound Chaser." Steve Howe does his usual flamenco guitar thing in the middle somewhere, but plays it on some heavy, dirty-sounding guitar, and that's after the most jarring, harshest synths in the universe bounce around the speakers and tug you around from one side of your room to the other, and Jon shouts out the derisive chant, "CHA! CHA CHA CHA! CHA CHA CHA!" as the crazy synthesizer shit continues. If you thought that "The Gates of Delirium" was the craziest crazy in crazyville, you hadn't HEARD crazy yet. Then, "To Be Over" strides in a melancholy and tasteful and soothing, because after all the wackiness, you need some cool- down time. It's the weakest tune on the album (but only in comparison) until the 7:30 mark when suddenly it becomes the most beautiful shit ever with Howe and a sitar and angel Anderson and the tears come down and Moraz leaves and prog rock goes out, not with a wimper, but a CHA! CHA CHAA CHA CHA! Relayer is far from the place to start listening to Yes, but it's somewhere on the journey you'll get to and won't leave.

Published on July 19, 2018 03:45

July 18, 2018

Rick Wakeman, Session Man

Rick Wakeman is one of rock's foremost keyboardists. Obviously any Yesfan looks upon Wakeman as one of the core musicians in the band's storied half-century, but fewer realize that, aside from his initial band, Strawbs, Wakeman was a key incidental session player, most famously for David Bowie's "Life on Mars"; the song would lose its luster without that iconic piano. For Bowie, Wakeman also contributed to Space Oddity, playing the mellotron and electric harpsicord, Elton John's Madman Across the Water, Cat Steven's Teaser and the Firecat, the piano for T-Rex's "Bang a Gong" and Lou Reed's debut LP.

Rick Wakeman is one of rock's foremost keyboardists. Obviously any Yesfan looks upon Wakeman as one of the core musicians in the band's storied half-century, but fewer realize that, aside from his initial band, Strawbs, Wakeman was a key incidental session player, most famously for David Bowie's "Life on Mars"; the song would lose its luster without that iconic piano. For Bowie, Wakeman also contributed to Space Oddity, playing the mellotron and electric harpsicord, Elton John's Madman Across the Water, Cat Steven's Teaser and the Firecat, the piano for T-Rex's "Bang a Gong" and Lou Reed's debut LP.Classically trained at the Royal College of Music, Wakeman found himself in such high demand as a session player that he dropped out of the College in 1969 to concentrate on his career. Wakeman recalls the mellotron session for "Space Oddity:" It was early 1969; I was 19 coming up on 20. I'd worked with the producer Tony Visconti that year on the Junior's Eyes album. I was playing a Mellotron, which was a relatively new instrument and difficult to keep in tune, but I'd found a crafty way. Tony asked: 'How'd you do that?' and I said: 'It's just a fingering technique' and that was that.

"Soon after, Tony called me up and said, 'Rick, I need you to come up to London to play some Mellotron on David Bowie's new single, "Space Oddity." I drove up to London and parked on Wardour Street and went over to Trident Studios to meet David. 'Tony says you can keep this bloody thing in tune,' he said. 'Well yeah, hopefully,' I replied. It was before David was famous, so I wasn't nervous about meeting him – it was just another bit of session work.

"We knocked it out in about 20 minutes. I think it got to number five first time around in '69 and then in '75 when it was rereleased it went to number one. A year later David called and asked me if I'd play some piano on some new songs. So I went round to his house in Beckenham, Kent. I nicknamed it Beckenham Palace because at the time I was living in a tiny little terraced house in West Harrow and his kitchen was bigger than my entire place.

"We knocked it out in about 20 minutes. I think it got to number five first time around in '69 and then in '75 when it was rereleased it went to number one. A year later David called and asked me if I'd play some piano on some new songs. So I went round to his house in Beckenham, Kent. I nicknamed it Beckenham Palace because at the time I was living in a tiny little terraced house in West Harrow and his kitchen was bigger than my entire place."I sat at the piano while he played songs on his battered old guitar. Things had really changed for him. He was a successful artist and he had a young family. I sat at the piano while he played a load of songs to me on his battered old 12-string guitar. "Life on Mars" stuck out as being something very special. He wanted a piano solo, he wanted the album to be very piano-orientated. I was given complete freedom by him."

In 1971, having just joined the band, Yes was on tour for Fragile, interestingly as the opening band for Black Sabbath. "Yes supported Black Sabbath in America in the early days, and me and Ozzy always got on great. Because of my various alcoholic diseases, I haven't been able to drink for 20-odd years, but back then I was a serious drinker, as were all of Sabbath, so we got on like a house on fire, matching each other drink for drink. When we supported 'em on Yes’s Fragile tour, they had a spare seat on their private plane, so a lot of the time I'd travel with them. You literally couldn't move for booze on that plane. Ozzy was probably putting away as much as me – which was as much as humanly possible."

In the book, Caped Crusader, Rick Wakeman in the 1970s, Elton John writes in the book's foreward, "Rick's mastery of electronic instruments only adds to his abilities, and I think it is fair to say he was one of the reasons I stuck to the piano. I also admire his attitude to stage shows - always willing to take a gamble, but never sacrificing his musical ideals. Just as important, never losing his sense of humour and his sense of the ridiculous. Anyone who can put on an ice show at Wembley must be all right. I must add that Rick loves cars and is a fanatic when it comes to soccer. Therefore, he and I have an unbreakable bond.

"It has become fashionable to knock musicians who have been around a while, and who are still determined to persevere in what they believe in. It is very easy to be misunderstood along the way, but it is vital to ignore trends and get on with what you want to do. Rick will always do this because, quite simply, he's that much better than everyone else."

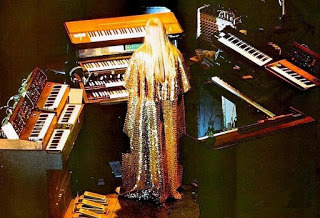

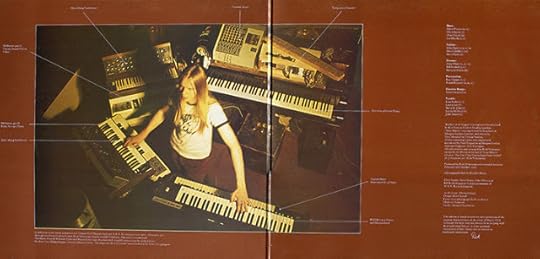

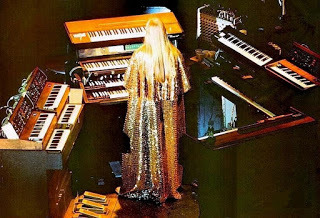

The photo above is from the gatefold of The Six Wives of Henry VIII and shows the variety of keyboards that Wakeman has used. Starting on the upper left is Wakeman's confessed favorite, the Mini Moog. Clockwise you'll note a custom mixer and a frequency counter sitting on a Steinway Grand Piano. Rick's left hand is playing the RMI electric piano, which sits atop a custom Hammond C3. With his right hand he plays another Mini Moog that sits upon a Mellotron 400D.

Published on July 18, 2018 19:06

Indian Takeaway - More Tales

The order, Rick Wakeman said, was for chicken vindaloo, rice pilau, six papadums, bhindi bhaji, Bombay aloo, and a stuffed paratha. This was November 1973 and Yes had sold out the Manchester Free Trade Hall for a performance of Tales From Topographic Oceans. The album consisted of four songs that rolled gently together, over four sides of vinyl, for 83 minutes. "There were a couple of pieces where I hadn't got much to do, and it was all a bit dull. During every show, a keyboard tech reclined underneath Wakeman's Hammond organ, ready to fix broken hammers or ribbons and to "continually hand me my alcoholic beverages." That night in Manchester, the tech asked the bored Wakeman what he wanted to eat after the show. Wakeman, the lone carnivore in Yes, ordered the curry. "Half the audience were in narcotic rapture on some far-off planet," Wakeman wrote in his 2007 memoir, "and the other half were asleep, bored shitless."

The order, Rick Wakeman said, was for chicken vindaloo, rice pilau, six papadums, bhindi bhaji, Bombay aloo, and a stuffed paratha. This was November 1973 and Yes had sold out the Manchester Free Trade Hall for a performance of Tales From Topographic Oceans. The album consisted of four songs that rolled gently together, over four sides of vinyl, for 83 minutes. "There were a couple of pieces where I hadn't got much to do, and it was all a bit dull. During every show, a keyboard tech reclined underneath Wakeman's Hammond organ, ready to fix broken hammers or ribbons and to "continually hand me my alcoholic beverages." That night in Manchester, the tech asked the bored Wakeman what he wanted to eat after the show. Wakeman, the lone carnivore in Yes, ordered the curry. "Half the audience were in narcotic rapture on some far-off planet," Wakeman wrote in his 2007 memoir, "and the other half were asleep, bored shitless."Wakeman kept on at the keyboards, adding gossamer organ melodies and ambient passages to the songs. And then, around 30 minutes later, his tech started handing up "little foil trays" of curry, and Wakeman began placing them on the keyboards. "I still didn't have a lot to do," he wrote, "so I thought I might as well tuck in." The food was obscured by the instrument stacks, further obscured by Wakeman's cape, but the aroma danced over to Yes's lead singer, Jon Anderson. He took a good look at the culinary insult. Shrug. Papadum in hand, he returned to his microphone to sing his next part.

Published on July 18, 2018 05:41

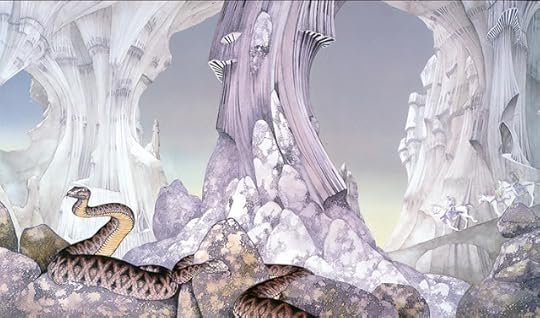

Tales From Topographic Oceans (AM7) or 3am AM10

Tales was the Yes LP I'd chuck on at 3am when my thoughts and sensibilities left the beaten track looking for goblins in the thickets. The Lord Of The Rings were my favorite books in the 70s for no other reason than that they transported me to alternate landscapes; the same applied to Tales From Topographic Oceans. Tales was the proggiest, most ethereal thing that didn't contain the words King or Crimson.

The idea for the album's concept came about in March 1973 in Anderson's hotel room in Tokyo during the Yessongs tour. He was pondering a theme for a "large-scale composition" and found himself "caught up in a lengthy footnote on page 83" of the Autobiography of a Yogiby Paramahansa Yogananda that described four classes of Hindu scripture known as the Shastras. Anderson was introduced to Yogananda's work at Bill Bruford's wedding by Jamie Muir, the percussionist for King Crimson, on March 2, 1973. When the tour hit America in April, Anderson described the concept to Howe who liked the idea of four interlocking pieces based around these scriptures. Anderson and Howe held candlelight writing vigils in their rooms, completing the lyrics and instrumentation after a single six-hour writing session in Savannah, Georgia. Anderson described the experience as a "magical" one, "which left both of us exhilarated for days." Notice, by the way, that Anderson's recollections fail to mention either Squire or Wakeman (with White a fledgling member joining the Yessongs troupe just three days prior to the tour due to Bruford's defection to King Crimson).

Wakeman took a dislike to the album's concept and structure from the beginning, making only minimal musical contributions, and often spending his time drinking at a local pub and playing darts. Black Sabbath was recording Sabbath Bloody Sabbath down the hall, and Wakeman took time off to play synth on "Sabbra Cadabra." According to Sabbath guitarist, Tony Iommi, Wakeman refused payment from the band and was compensated with beer.

For me, the sessions for Tales were the ultimate surreal indulgence for a rock band - at least Brian Wilson had crazy on his side. From Anderson's decorating the studio like a barnyard, replete with life-sized plastic cow, to the image of Howe and Anderson weaving a tale of Indian spiritualism in an airport Holiday Inn, Tales From Topographic Oceans may indeed deserve all its negative press. And though I too can see the possibilities for an AM10 were the tales edited to one LP, my 3ams were all the more spiritual because of it (maybe I was high, or drowning in topographic oceans).

Published on July 18, 2018 03:40

July 17, 2018

The Wakeman 70s

Rick Wakeman described himself at grammar school as "a horror." Due to his lack of discipline he needed to pass 8 music exams to earn his A-levels, which required him, as his mother remembered, "to do two years' work in ten months". Wakeman's music teacher gave him determination after betting him ten shillings that he would not succeed. With that, Wakeman secured a place at the Royal College of Music, where he studied piano, clarinet, orchestration, and modern music. His intention was to become a concert pianist, yet the reality was a relaxed attitude with regard to his studies that included drinking in pubs, missing lectures and spending his spare time at a music shop in Ealing. Still, early in 1968 Wakeman met producers Tony Visconti, Gus Dudgeon, and Denny Cordell, and was offered studio session work for Regal Zonophone Records.

Rick Wakeman described himself at grammar school as "a horror." Due to his lack of discipline he needed to pass 8 music exams to earn his A-levels, which required him, as his mother remembered, "to do two years' work in ten months". Wakeman's music teacher gave him determination after betting him ten shillings that he would not succeed. With that, Wakeman secured a place at the Royal College of Music, where he studied piano, clarinet, orchestration, and modern music. His intention was to become a concert pianist, yet the reality was a relaxed attitude with regard to his studies that included drinking in pubs, missing lectures and spending his spare time at a music shop in Ealing. Still, early in 1968 Wakeman met producers Tony Visconti, Gus Dudgeon, and Denny Cordell, and was offered studio session work for Regal Zonophone Records.Wakeman became a busy session musician, quickly gaining the nickname, "One Take Wakeman." In June 1969, he played mellotron on David Bowie's "Space Oddity," and joined progressive folk band Strawbs until his return to session work in 1971. At this time he bought a Minimoog synthesizer at half price from actor Jack Wild, who thought that it was defective since it only played one note at a time. Like Emerson, Wakeman took the Moog to places no one knew it could go.

Rick played the iconic piano on Cat Stevens' "Morning Has Broken," but was omitted from the credits and never paid. (Stevens later apologized and paid Wakeman for the error.) Other session tracks from the period include "Get it On," "Life on Mars" and three tracks for Elton John's Madman Across the Water. In July 1971, Rick was faced with "one of the most difficult decisions" of his career, after Bowie invited him to play keyboards for his new backing band, The Spiders from Mars, with guitarist Mick Ronson. Wakeman then received a phone call at 2am from Chris Squire, the bass player of Yes, who explained that the band wanted a new keyboardist. Wakeman agreed to sit in with the band as they rehearsed their fourth album, Fragile.

Rick played the iconic piano on Cat Stevens' "Morning Has Broken," but was omitted from the credits and never paid. (Stevens later apologized and paid Wakeman for the error.) Other session tracks from the period include "Get it On," "Life on Mars" and three tracks for Elton John's Madman Across the Water. In July 1971, Rick was faced with "one of the most difficult decisions" of his career, after Bowie invited him to play keyboards for his new backing band, The Spiders from Mars, with guitarist Mick Ronson. Wakeman then received a phone call at 2am from Chris Squire, the bass player of Yes, who explained that the band wanted a new keyboardist. Wakeman agreed to sit in with the band as they rehearsed their fourth album, Fragile. The newly formed and classic Yes lineup made Fragile in five weeks. The album featured five tracks written by each member of the group, with Wakeman recording "Cans and Brahms", an adaptation of the third movement of Symphony No. 4 in E Minor by Johannes Brahms. Wakeman has called the track "dreadful," as contractual disputes between Atlantic Records and A&M Records, who he was with as a solo artist, prevented him from writing his own compositions. Fragile was released in November 1971 and peaked at number 4 in the US and number 7 in the UK. IN the 1972 Melody Maker readers poll, Wakeman came in 2nd behind Keith Emerson.

Yes recorded their fifth album, Close to the Edge, in 1972. It featured Wakeman on church organ at St Giles-without-Cripplegate in London. He received a long overdue writing credit on the third track, "Siberian Khatru.". Close to the Edge peaked at number 4 in the UK and number 3 in the US where it sold over a million copies.

Yes recorded their fifth album, Close to the Edge, in 1972. It featured Wakeman on church organ at St Giles-without-Cripplegate in London. He received a long overdue writing credit on the third track, "Siberian Khatru.". Close to the Edge peaked at number 4 in the UK and number 3 in the US where it sold over a million copies.During his sojourn with Yes, he released his first studio album, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, in January 1973. Recording took place from February to October 1972 with an advance of £4,000 from A&M Records. On 16 January 1973, the album was previewed with Wakeman performing excerpts on the BBC's Old Grey Whistle Test, afterward reaching number 7 in the UK and 30 in the US.

By 1973, Wakeman came out first in the top keyboardist category in Melody Maker, and during a break in the Topographic Oceans tour, he performed his new work, Journey to the Centre of the Earth, based on Jules Verne's science fiction novella. Wakeman met with his manager Brian Lane to pitch the idea of performing Journey in concert with an orchestra, choir, and a rock band. As the cost of producing the album in a studio was too high, A&M Records agreed to record the album live. Wakeman held two concerts at the Royal Festival Hall in London in January 1974 with the London Symphony Orchestra, the English Chamber Choir and actor David Hemmings.

By 1973, Wakeman came out first in the top keyboardist category in Melody Maker, and during a break in the Topographic Oceans tour, he performed his new work, Journey to the Centre of the Earth, based on Jules Verne's science fiction novella. Wakeman met with his manager Brian Lane to pitch the idea of performing Journey in concert with an orchestra, choir, and a rock band. As the cost of producing the album in a studio was too high, A&M Records agreed to record the album live. Wakeman held two concerts at the Royal Festival Hall in London in January 1974 with the London Symphony Orchestra, the English Chamber Choir and actor David Hemmings.The album was poorly received among A&M management; however, as Wakeman was under contract with A&M in the US, Jerry Moss (the M in A&M) insisted on the album's release. On 18 May 1974, his twenty-fifth birthday, Wakeman confirmed his departure from Yes to manager Brian Lane. He had heard some of the band's material for what became Relayer and felt unable to contribute to the music. Later in the day, he received a call from A&M Records, informing him that Journey to the Centre of the Earth had just entered the UK charts at number one. Wakeman received an Ivor Novello Award for the album and a Grammy Award nomination, with the album going on to sell 14 million copies worldwide.

Despite his success, Wakeman's health had deteriorated, and in mid-1974, he suffered a heart attack. During his recovery in Wexham Park Hospital, he wrote the first song for his next concept album, The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Wakeman recorded King Arthur at Morgan Studios from October 1974 to January 1975, with the New World Orchestra, English Chamber Choir, and Nottingham Festival Vocal Group. The album was released in April 1975 and peaked at number 2 in the UK and number 21 in the US, earning Gold certification in Brazil, Japan, and Australia. A month later, Wakeman performed the album live for three sold out shows at Wembley Arena. As the arena floor was set up with ice, Wakeman decided to present the show on ice with fourteen skaters and a castle in the middle for the orchestra, choir, and his band. The eccentric shows were well received but expensive to produce, consuming much of the income from the album's sales. (The event came in at number 79 on the 100 Greatest Shocking Moments in Rock and Roll program by VH1.) The album sold over 12 million copies.

In these past 40 years, Rick Wakeman has produced a plethora of music, but it was the Wakeman 70s for which he will be remembered.

Published on July 17, 2018 14:53

Tales of a 13 Year Old - Yes in My Teens

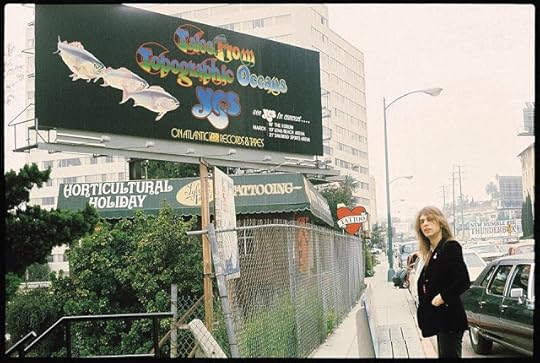

Steve Howe on the Sunset Strip, 1973Rock critics tend to harp on a single aspect of music and deride everything that doesn't fit their obsession. In the 70s, the predominant bent was a critic who, as a "purist," felt that rock derived its energy from its rebellious stance, embraced Iggy and the Ramones, and insisted that anything else was "for girls." Progressive Rock, therefore, was girly as all hell, it took its cues from symphonic girly music, and who had the energy to slam dance to a twenty-minute opus? There was nothing less rebellious than classical music. One can only imagine the critic sidled up to the bar at CBGBs drunk-talking about Lou Reed ready to punch anyone who listened to sissies like Camel or Yes. And indeed, fists flew when Yes released Tales From Topographic Oceans.

Steve Howe on the Sunset Strip, 1973Rock critics tend to harp on a single aspect of music and deride everything that doesn't fit their obsession. In the 70s, the predominant bent was a critic who, as a "purist," felt that rock derived its energy from its rebellious stance, embraced Iggy and the Ramones, and insisted that anything else was "for girls." Progressive Rock, therefore, was girly as all hell, it took its cues from symphonic girly music, and who had the energy to slam dance to a twenty-minute opus? There was nothing less rebellious than classical music. One can only imagine the critic sidled up to the bar at CBGBs drunk-talking about Lou Reed ready to punch anyone who listened to sissies like Camel or Yes. And indeed, fists flew when Yes released Tales From Topographic Oceans. Now keep in mind that in 1973 I was thoroughly immersed in progressive rock and as a teen, plunking down the funds for a double LP meant I was going to like it or else, so forget the fact that Tales comprised four 20+ minute rock songs about the meaning of life as derived from Eastern spirituality that assumed we had no homework and could sit around for 85 minutes to have the science of God revealed; I plain wasn't going to do my homework and Pamela Dumouchelle liked someone else, so yeah.

Now keep in mind that in 1973 I was thoroughly immersed in progressive rock and as a teen, plunking down the funds for a double LP meant I was going to like it or else, so forget the fact that Tales comprised four 20+ minute rock songs about the meaning of life as derived from Eastern spirituality that assumed we had no homework and could sit around for 85 minutes to have the science of God revealed; I plain wasn't going to do my homework and Pamela Dumouchelle liked someone else, so yeah.When I first heard it, it was admittedly a bit boring, but I was high and fell asleep and then there was that pretty French theme about the sun and that incredible guitar on "The Ancient,"- indeed Howe's riffs and finesse were endlessly inventive - and by listen number two (really angry over a Pamela phone call designed only to get my goat), I started to understand and appreciate the nuances hidden in within the heady incumbrances. But why would a young man with a girl on his mind find anything even remotely appealing about Tales when he could have easily sat for the same length of time and snuggled in the teenage angst of Quadrophenia? I had no clue, but I suddenly couldn't get enough of it. It was the same kind of feeling when in college, still high, I discovered that I understood A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (or more intrinsically Dylan Thomas' A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog). It was difficult, and that was ultimately intriguing. In retrospect, oddly, I find "The Revealing Science of God" to be nothing more than a simple rock song, dronelike in its adherence to rock's favorite E major. And that was Tales in general, simple, if oddly syncopated; rock songs with oodles of adornment.

While far from the greatest progressive rock LP, if you're looking for the ultimate prog album (penultimate maybe; I'm thinking Pictures at an Exhibitionmight have those bragging rights), look no further. Tales is quite simply awe-inspiring in its bombastic conception and delivery, which was no simple task considering that Wakeman hated the album and confessed to contributing little (still managing to offer some of the finest Yes keyboard work). One of the drags of the original LP was the muddled production that sounded like runny watercolors, merky and dull, but that's where we're in luck: two words – Steven Wilson. Here Wilson's remixes (Tales, 2016) make an overwhelming difference and truly bring the LP to life. Keep in mind that Tales is no AM10, and realistically only squeaks over a 7, but often what emerges from the LP is the best that Yes had to offer (the first two minutes of "Science" are sublime). Bottom line, to enjoy Tales of Topographic Oceans, one needs an attention span, patience with the repetition of themes and a bottle of wine. Jon Andersons lyrics are typically naff, impenetrable rubbish that only mean anything when you're high (is that a bad thing?), nonetheless these esoteric Tales are a great place to get lost.

While far from the greatest progressive rock LP, if you're looking for the ultimate prog album (penultimate maybe; I'm thinking Pictures at an Exhibitionmight have those bragging rights), look no further. Tales is quite simply awe-inspiring in its bombastic conception and delivery, which was no simple task considering that Wakeman hated the album and confessed to contributing little (still managing to offer some of the finest Yes keyboard work). One of the drags of the original LP was the muddled production that sounded like runny watercolors, merky and dull, but that's where we're in luck: two words – Steven Wilson. Here Wilson's remixes (Tales, 2016) make an overwhelming difference and truly bring the LP to life. Keep in mind that Tales is no AM10, and realistically only squeaks over a 7, but often what emerges from the LP is the best that Yes had to offer (the first two minutes of "Science" are sublime). Bottom line, to enjoy Tales of Topographic Oceans, one needs an attention span, patience with the repetition of themes and a bottle of wine. Jon Andersons lyrics are typically naff, impenetrable rubbish that only mean anything when you're high (is that a bad thing?), nonetheless these esoteric Tales are a great place to get lost.

Published on July 17, 2018 03:56

July 16, 2018

Or it could mean nothing...

The first verse of "Close to the Edge" alludes to the mundane punctuated by transcendent moments, the life each of us actually lives. "The time between the notes relates the color to the scenes." The "notes" are the instances of insight and understanding, but they are flanked before and after by mundane "time," the daily grind of our lives. Yet how else could such moments stand out as profound? This is the genius of life itself, long intervals of the mundane followed by moments of rapture and insight, immanence and transcendence. This movement is mirrored in CTTE: strong, ecstatic "notes" that jump out, sometimes astonishingly, from varying tempos of melody. Only with such variation can the song paint the beautiful picture it does, as it "relates the color to scenes." What emerges is an authentic reproduction of the spiritual tempo of life itself "A constant vogue of triumphs dislocate man so it seems." What a resonating line! If life were a series of triumphant moments, rather than the interweaving of happiness and sadness, insight and confusion, confidence and insecurity ("I get up, I get down . . ."), we would be "dislocated" from what is meaningful and important, caught up in false, worldly values or whatever is in "vogue."

The first verse of "Close to the Edge" alludes to the mundane punctuated by transcendent moments, the life each of us actually lives. "The time between the notes relates the color to the scenes." The "notes" are the instances of insight and understanding, but they are flanked before and after by mundane "time," the daily grind of our lives. Yet how else could such moments stand out as profound? This is the genius of life itself, long intervals of the mundane followed by moments of rapture and insight, immanence and transcendence. This movement is mirrored in CTTE: strong, ecstatic "notes" that jump out, sometimes astonishingly, from varying tempos of melody. Only with such variation can the song paint the beautiful picture it does, as it "relates the color to scenes." What emerges is an authentic reproduction of the spiritual tempo of life itself "A constant vogue of triumphs dislocate man so it seems." What a resonating line! If life were a series of triumphant moments, rather than the interweaving of happiness and sadness, insight and confusion, confidence and insecurity ("I get up, I get down . . ."), we would be "dislocated" from what is meaningful and important, caught up in false, worldly values or whatever is in "vogue."

"And space between the focus shape ascend knowledge of love." A powerful vision of what love is, what function it serves. We go through life searching for meaning, trying to get things in focus, but, again, those moments of insight are few and far between. It is when we’re in confusion, unclear about what it all means, that we truly understand and experience the importance of love, of compassion. When we are weak, confused, depressed, uncertain, vulnerable — that's when the love of others means more to us than anything. And it goes both ways: by giving love to others in their time of need, we experience spiritual meaning even during times of uncertainty and darkness. Love makes the "space between the focus shape" not only endurable but profoundly meaningful and important.

"As song and chance develop time loss social temperance rules above." This is a wide-eyed, sober view of the social oppression true artists and dreams must expect in this life. The pursuit of meaning through the course of the mundane puts the dreamer/artist at odds with social expectations. From society’s viewpoint, art is a waste of time, and the artist is a threat to the social order. This line makes me think of a disturbing passage in Plato’s "Republic," where Socrates himself disavows the role of the artist in the well-ordered republic, the awareness that the path of truth and beauty is one that attracts society’s wrath. It is the way of the cross ("I crucified my hate and held the word within my hand/ There's you, the time, the logic or the reasons we don’t understand").

The next few lines are more straightforward: "Then according to the man who showed his outstretched arm to space/ He turned around and pointed, revealing all the human race/ I shook my head and smiled a whisper, knowing all about the place." Every sage arrives at the same destination. Anderson humbly acknowledges that he has discovered the same thing. That "outstretched arm to space" again reminds me of the crucifixion. And the whole lyric here reminds me of a poem by Emily Dickinson: "Better than music, for I who heard it," about the ecstatic vision, which she analogizes to the most exquisite music. She ends her poem: "Let me not spill its smallest cadence/ Humming, for promise, when alone/ Humming, until my faint rehearsal/ Drop into tune around the throne."

Then the final ascendant verse: "On a hill, we viewed the silence of the valley/ Called to witness cycles only of the past/ And we reach all this with movements in between the said remark." What a powerful summing-up of the description of the spiritual journey that came before! The ultimate revelation is simply making final sense of life’s entire journey, pitfalls and all. All that has come before is revealed as a prelude for where it all leads, where we all end up. And, again, there’s the mystic’s speechlessness, the paradox of “the said remark” — the song lyrics themselves — as having been arrived at through “movements” through silence, "the time between the notes," etc. Incredible insight here. Again I think of Dickinson: "It is the ultimate of talk/ The impotence to tell."

Published on July 16, 2018 12:52