R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 68

June 19, 2018

Catherinesque

Kate Bush, even at 19, was an astounding singer/songwriter. Look at how she arrived in 1976: "Out on the wiley, windy moors/ We'd roll and fall in green./ You had a temper like my jealousy:/ Too hot, too greedy." The Kick Inside more than lived up to the promise of her first single. It was a glorious combination of intrigue and mystery; it was intelligent, fresh and compulsive. It's funny that critics brand novels willy-nilly with the adjective that's launched a thousand blurbs—Dickensian, yet if ever there was a modern writer who deserves the accolade on a modern level, it's KB. Dickensian, in my mind, signifies sentimentality, attentiveness to social mores and to the human condition, or it creates a cast of comically hyperbolic characters. Rock and pop singer/songwriters rarely get the literary respect they deserve, yet what indeed is more Dickensian than The Kick Inside? And I'm not talking some Steampunk façade in sepiatone, but a truly 20th Century British perspective of a woman’s maturation. That to me is Dickensian.

Kate Bush, even at 19, was an astounding singer/songwriter. Look at how she arrived in 1976: "Out on the wiley, windy moors/ We'd roll and fall in green./ You had a temper like my jealousy:/ Too hot, too greedy." The Kick Inside more than lived up to the promise of her first single. It was a glorious combination of intrigue and mystery; it was intelligent, fresh and compulsive. It's funny that critics brand novels willy-nilly with the adjective that's launched a thousand blurbs—Dickensian, yet if ever there was a modern writer who deserves the accolade on a modern level, it's KB. Dickensian, in my mind, signifies sentimentality, attentiveness to social mores and to the human condition, or it creates a cast of comically hyperbolic characters. Rock and pop singer/songwriters rarely get the literary respect they deserve, yet what indeed is more Dickensian than The Kick Inside? And I'm not talking some Steampunk façade in sepiatone, but a truly 20th Century British perspective of a woman’s maturation. That to me is Dickensian. Even without the cultural context of the time, Bush would have been special, yet it was painfully obvious in the 1970s just how male-dominated the British pop world was. Females sang, of course, but never their own material and women hardly ever played instruments. America had Joni Mitchell and Laura Nyro and Carol King, but British women were the trained monkeys of the music industry, or they were pretty and petite (early Marianne Faithful comes to mind). And never did they write of or sing about their vaginas (indeed, Kate's bush). Seriously, it took the 19, scratch that, the 16 year old Kate to take on the literary world, and still there were critics who tossed the phenomenon away as "squeaky." 40 years later the impact of Kate's accomplishment is lost in the normalcy of the strong female (even in Britain). Someday we will be searching for an adjectified critical association like Dickensian or Kafkaesque, but what, Bushian? Katean? High praise indeed for anyone in our future labeled Catherinesque.

Published on June 19, 2018 04:24

June 18, 2018

Kate Bush - An Early History

East Wickham Farm was as magical a place as one could find outside of Hobbiton. Picture it 150 years ago sitting off by itself, a seeming Bridadoon, but by Catherine Bush's childhood, it was a part of the sub-urban landscape with just one side of the property looking out on an England that's hardly there anymore. East Wickham Farm was the stuff that the Dreaming was made of. There was a duck pond, a dovecote, a circular rose garden and a ramshackle barn (that later would become Kate's recording studio). Think for a moment of that feeling as a kid on Peter Pan's Flight at Disneyland. It was that kind of fanciful imagery that created what Kate Bush would become.

East Wickham Farm was as magical a place as one could find outside of Hobbiton. Picture it 150 years ago sitting off by itself, a seeming Bridadoon, but by Catherine Bush's childhood, it was a part of the sub-urban landscape with just one side of the property looking out on an England that's hardly there anymore. East Wickham Farm was the stuff that the Dreaming was made of. There was a duck pond, a dovecote, a circular rose garden and a ramshackle barn (that later would become Kate's recording studio). Think for a moment of that feeling as a kid on Peter Pan's Flight at Disneyland. It was that kind of fanciful imagery that created what Kate Bush would become. By 1971, embryonic versions of "The Man With the Child in His Eyes" and "Saxophone Song" began to emerge as Kate developed her poetry; her piano playing an outlet for her girlhood frustrations. But the music and its intensity was real, fanciful though in-your-face, and Kate's family knew. Ricky Hopper, a friend with music business connections, tried to shop demo tapes of Kate's songs all the major companies; none were interested. Kate's songs were "morbid" or "boring" and "uncommercial." Kate considered the alternatives: psychiatry or social work.

Unable to help further, Hopper contacted David Gilmour, who he knew at Cambridge University. Gilmour, spotting for talent, was persuaded to listen to the demos and then to hear Kate perform. He was immediately impressed and agreed to help. In 1973 Kate recorded at Gilmour's home studio, with Gilmour on guitar, and Peter Perrier and Pat Martin of Unicorn on drums and bass. The songs included "Passing Through Air" (later to surface on the B-side of the 1980 single "Army Dreamers") and a song now known as "Maybe." Still, no one but Gilmour was impressed.

Unable to help further, Hopper contacted David Gilmour, who he knew at Cambridge University. Gilmour, spotting for talent, was persuaded to listen to the demos and then to hear Kate perform. He was immediately impressed and agreed to help. In 1973 Kate recorded at Gilmour's home studio, with Gilmour on guitar, and Peter Perrier and Pat Martin of Unicorn on drums and bass. The songs included "Passing Through Air" (later to surface on the B-side of the 1980 single "Army Dreamers") and a song now known as "Maybe." Still, no one but Gilmour was impressed.A year later, Gilmour decided that the only way to interest the record companies in Kate's talent was to make a short three-song demo to full professional standards. Kate went into Air Studios in London's West End with Gilmour as producer, Andrew Powell as arranger, Geoff Emerick as engineer, three masters of their trade (nice way to start). The three songs recorded were"Saxophone Song," "The Man With the Child in His Eyes," and the aforementioned "Maybe."

In July 1975 while Pink Floyd were at Abbey Road recording Wish You Were Here, Gilmour played the three-track demo to Bob Mercer, General Manager of EMI. Kate simultaneously got a small inheritance, and left school to concentrate on music. A publishing contract was settled and then a recording deal. Kate received a £3,000 advance and £500 for publication rights and EMI was content for Kate to have time to "grow up." During the first year of the contract Kate makes two more demo tapes while resisting EMI's attempts to "commercialize" her songs. In March, 1977 "Wuthering Heights" was written at the full moon. A month later Kate's brother, Paddy, formed a band with his friends Del Palmer, Brian Bath and Charlie Morgan. Kate was asked to be the vocalist. First at the Rose of Lee Public House in Lewisham, and then in pubs and clubs in and around London, The KT Bush Band performed rock-and-roll standards ("Honky Tonk Woman," "Heard It Through the Grapevine," "Come Together")), although Kate included "Saxophone Song" and "James and the Cold Gun" from her own repertoire.

In July 1975 while Pink Floyd were at Abbey Road recording Wish You Were Here, Gilmour played the three-track demo to Bob Mercer, General Manager of EMI. Kate simultaneously got a small inheritance, and left school to concentrate on music. A publishing contract was settled and then a recording deal. Kate received a £3,000 advance and £500 for publication rights and EMI was content for Kate to have time to "grow up." During the first year of the contract Kate makes two more demo tapes while resisting EMI's attempts to "commercialize" her songs. In March, 1977 "Wuthering Heights" was written at the full moon. A month later Kate's brother, Paddy, formed a band with his friends Del Palmer, Brian Bath and Charlie Morgan. Kate was asked to be the vocalist. First at the Rose of Lee Public House in Lewisham, and then in pubs and clubs in and around London, The KT Bush Band performed rock-and-roll standards ("Honky Tonk Woman," "Heard It Through the Grapevine," "Come Together")), although Kate included "Saxophone Song" and "James and the Cold Gun" from her own repertoire. In August 1977 Kate was finally called in to record material for an album. Though the songs recorded were Kate's, her role was confined to vocals, piano and a few simple piano arrangements. It was decided to use eleven songs from this session and two from the 1975 Gilmour demo on the album. In September, EMI wanted to release "James and the Cold Gun" as the first single. Kate instead wants "Wuthering Heights," and got her way, but Christmas was approaching and EMI was unwilling to launch the new artist into the pre-Christmas maelstrom. Many promos of the single, nonetheless, had been sent out to radio. Eddie Puma, producer of Capital Radio's Late Show, and Tony Myatt, the host, decided to play it, and continued to play it throughout November and December. Other radio stations follow. "Wuthering Heights" was an airplay hit two months before its release.

In August 1977 Kate was finally called in to record material for an album. Though the songs recorded were Kate's, her role was confined to vocals, piano and a few simple piano arrangements. It was decided to use eleven songs from this session and two from the 1975 Gilmour demo on the album. In September, EMI wanted to release "James and the Cold Gun" as the first single. Kate instead wants "Wuthering Heights," and got her way, but Christmas was approaching and EMI was unwilling to launch the new artist into the pre-Christmas maelstrom. Many promos of the single, nonetheless, had been sent out to radio. Eddie Puma, producer of Capital Radio's Late Show, and Tony Myatt, the host, decided to play it, and continued to play it throughout November and December. Other radio stations follow. "Wuthering Heights" was an airplay hit two months before its release. On January 20, 1978, "Wuthering Heights" was finally released. February 14th, the single moved up to number 27; having cracked the top forty, the floodgates opened wide. Kate, though, appeared on Top of the Pops in a performance that could have marked the end. "It was like watching myself die...a bloody awful performance." On February 17th, The Kick Inside was released, and by March, "Wuthering Heights" reached the No. 1 position on the British singles chart. In April the LP peaked at No. 3, and a month later "Wuthering Heights" went gold. EMI allow Kate to have her way over the choice of the follow-up single, "The Man With the Child in His Eyes," which even made a dent stateside. At just 19 years of age, a star wasn't born, a whole galaxy was.

On January 20, 1978, "Wuthering Heights" was finally released. February 14th, the single moved up to number 27; having cracked the top forty, the floodgates opened wide. Kate, though, appeared on Top of the Pops in a performance that could have marked the end. "It was like watching myself die...a bloody awful performance." On February 17th, The Kick Inside was released, and by March, "Wuthering Heights" reached the No. 1 position on the British singles chart. In April the LP peaked at No. 3, and a month later "Wuthering Heights" went gold. EMI allow Kate to have her way over the choice of the follow-up single, "The Man With the Child in His Eyes," which even made a dent stateside. At just 19 years of age, a star wasn't born, a whole galaxy was.

Published on June 18, 2018 05:23

Kate Bush in '77

A year before "Wuthering Heights" made her an international phenom, and two years before the Tour of Life, a 17-year-old Kate Bush, as a part of the hastily named KT Bush Band, toured London and its environs in Morris Minor panel van. She performed classic songs like, of all things, "Honky Tonk Woman" and "Come Together," alongside early renditions of "James and the Cold Gun" and "Kite." It was there as well that she may have tried out obscure tunes like the haunting and unreleased "Something Like a Song," which was recorded as early as 1973, but more likely 1975.

A year before "Wuthering Heights" made her an international phenom, and two years before the Tour of Life, a 17-year-old Kate Bush, as a part of the hastily named KT Bush Band, toured London and its environs in Morris Minor panel van. She performed classic songs like, of all things, "Honky Tonk Woman" and "Come Together," alongside early renditions of "James and the Cold Gun" and "Kite." It was there as well that she may have tried out obscure tunes like the haunting and unreleased "Something Like a Song," which was recorded as early as 1973, but more likely 1975. Kate, with the help of David Gilmour signed to EMI in 1976, but the label execs felt she wasn't yet accomplished enough to record single, let alone an LP. Accustomed to performing only at the family home at Wickham Farm in Welling, she had never performed in front of an audience. Brian Southall, EMI's head of talent development said, "We'd heard demos in the office, we knew she was a prolific songwriter, but we hadn't seen her perform. So we suggested she gain some live experience." Sounds like The Beatles sent off to Hamburg. On a Tuesday night in March 1977, Bush played her first ever gig at the Rose of Lee pub in Lewisham. She performed two 45-minute sets to roughly 20 in attendance. The band was paid £27.

Kate, with the help of David Gilmour signed to EMI in 1976, but the label execs felt she wasn't yet accomplished enough to record single, let alone an LP. Accustomed to performing only at the family home at Wickham Farm in Welling, she had never performed in front of an audience. Brian Southall, EMI's head of talent development said, "We'd heard demos in the office, we knew she was a prolific songwriter, but we hadn't seen her perform. So we suggested she gain some live experience." Sounds like The Beatles sent off to Hamburg. On a Tuesday night in March 1977, Bush played her first ever gig at the Rose of Lee pub in Lewisham. She performed two 45-minute sets to roughly 20 in attendance. The band was paid £27."Her mum was there," Southall said. "She seemed to be doing the catering... The gig was slightly odd, a rock-and-roll set with songs you really didn't expect her to be doing, but I remember being very impressed by her. She already had an extraordinary voice and she really could perform."

I'm trying to picture the 17 year old Kate performing the dramatic "James and the Cold Gun" and the fledgling gunslinger routine (Kate shooting pubgoers with a cocked finger), which would become the highlight of the Tour of Life.

I'm trying to picture the 17 year old Kate performing the dramatic "James and the Cold Gun" and the fledgling gunslinger routine (Kate shooting pubgoers with a cocked finger), which would become the highlight of the Tour of Life.Strangely enough, upon first meeting David Gilmour in 1975, Kate had never even heard Pink Floyd. She stated, "I was not really aware of much contemporary rock music at that age. I had heard of them, but hadn't actually heard their music. It wasn't until later that I got to hear stuff like Dark Side of the Moon. And I just thought that was superb – I mean they really did do some pretty profound stuff." Gilmour would become the executive producer of The Kick Inside and sing on "Pull Out the Pin" from The Dreaming and Pink Floyd would become a startling influence on her subsequent music. Indeed, she liked The Wall so much that she borrowed the helicopter sequence to use on "Waking the Witch," and one can certainly hear the influence in the track's opening, kind of staccato Morse code, as Floydian as it gets. Of it Kate said, "That’s an effect that we managed to muck around with. It was a very experimental idea, a sort of trick really, that took us a long time to do. I wanted to give the impression of a very desperate attempt to communicate." It's a funny statement from someone who has so easily communicated these past 40 years.

Published on June 18, 2018 04:26

June 17, 2018

To Cut a Long Story Short...

Less Than Zero was a chronicle of our lives; Bret Easton Ellis merely wrote it down (I didn’t have a pencil). Gen X was the new wave, young enough to have escaped disco and punk - like starting over - as if we were in an episode of Behind the Music. We were cool like there had never been cool, fashioning a restless style, as if it had to go to the bathroom. The Cult With No Name, post punk, disaffected electronic crooners in outfits that channeled Bowie and Bolan (Spandau Ballet, Ultravox, Steve Strange), morphed into vintage-clean-cut, L.A. kids shopping at Cowboys and Poodles for Permapress slacks and clip on bowties (Haircut 100, Orange Juice, ABC); seconds later it was motorcycle chic (Depeche Mode, Heaven 17) – all of it obsessively clean, photographable, pretty. Quickly, there were too many girls/boys (“Which do you choose, a hard or soft option?”)/strangers, too many drugs, too many intoxicated drives home at dawn; calling out sick; that time you woke up in a phone booth by Danny’s Oki-Dog (“How’d I get here?”); that kid who died at the Lhasa from too much amyl.

Less Than Zero was a chronicle of our lives; Bret Easton Ellis merely wrote it down (I didn’t have a pencil). Gen X was the new wave, young enough to have escaped disco and punk - like starting over - as if we were in an episode of Behind the Music. We were cool like there had never been cool, fashioning a restless style, as if it had to go to the bathroom. The Cult With No Name, post punk, disaffected electronic crooners in outfits that channeled Bowie and Bolan (Spandau Ballet, Ultravox, Steve Strange), morphed into vintage-clean-cut, L.A. kids shopping at Cowboys and Poodles for Permapress slacks and clip on bowties (Haircut 100, Orange Juice, ABC); seconds later it was motorcycle chic (Depeche Mode, Heaven 17) – all of it obsessively clean, photographable, pretty. Quickly, there were too many girls/boys (“Which do you choose, a hard or soft option?”)/strangers, too many drugs, too many intoxicated drives home at dawn; calling out sick; that time you woke up in a phone booth by Danny’s Oki-Dog (“How’d I get here?”); that kid who died at the Lhasa from too much amyl.Some of us escaped the worst and blotted out that Oki-Dog thing and finished college and somehow balanced it all (Clay Easton and Blair), and some of us died trying (Julian Wells). Less than Zero was the fictional chronicle of our lives, River Phoenix was our poster child – and whereas Robert Downey Jr. made it through – River Phoenix, like Downey’s fictional character Julian, did not.

Music then, was more like soundtrack; it was incidental and in the background; it was a singles age (to be specific, it was the 12 in. singles age), and because of that, it is often, too often, critically overlooked and even dismissed. Yet there are many more 80s AM10s than in the 90s or naughts, so sit down and listen. The obvious:

Disintegration – The Cure (AM10)

After the scatter-shot glories of the too lengthy Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me, the Cure put forth their most cohesive work in Disintegration, an album of deep, introspective moods and textures that roll the listener in a Persian rug of melancholy. During these sessions, Robert Smith kept scraps of paper - on which he wrote his thoughts - in a box. Out of that box, says Smith, came Disintegration. The first half of which, from "Plainsong" to "Fascination Street," has a thematic and textural coherence, while Side Two is more individualistic and episodic, yet overall the mood is dramatic and evocative with Hitchcock pacing. This is a lush and moody album and signature Cure; one need only hear the chimes and the two minute intros to feel something uniquely Curish. Disintegration, alongside Blue and Revolver, Aja and After the Gold Rush, is a desert island disk, one that hasn’t aged at all in 25 years.

After the scatter-shot glories of the too lengthy Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me, the Cure put forth their most cohesive work in Disintegration, an album of deep, introspective moods and textures that roll the listener in a Persian rug of melancholy. During these sessions, Robert Smith kept scraps of paper - on which he wrote his thoughts - in a box. Out of that box, says Smith, came Disintegration. The first half of which, from "Plainsong" to "Fascination Street," has a thematic and textural coherence, while Side Two is more individualistic and episodic, yet overall the mood is dramatic and evocative with Hitchcock pacing. This is a lush and moody album and signature Cure; one need only hear the chimes and the two minute intros to feel something uniquely Curish. Disintegration, alongside Blue and Revolver, Aja and After the Gold Rush, is a desert island disk, one that hasn’t aged at all in 25 years.Black Celebration – Depeche Mode (AM10)

Though Violator was Depeche Mode's greatest commercial success, Black Celebration was the group's most cohesive effort. A concept album that takes the listener on a journey through the societal underbelly of sex, drugs, depression and betrayal, it is a dark affair indeed. The title cut is a synth masterpiece, with eerie sounds building until the song explodes, the protagonist wailing, "Your optimistic guise/looks like paradise/to someone like/me..." - haunting. The album ebbs and flows between soundscapes and tempos that serve only to make it more unsettling. "Black Celebration" segues effortlessly into "Fly On The Windscreen - Final," seething with a sense of urgency that is suddenly scaled back by the sequencing of "A Question Of Lust," "Sometimes" and "It Doesn't Matter Two." The flip side carries on with the sexual tension of "A Question Of Time" and "Stripped" giving way to "Here Is the House," a beautiful contemplation of what it means to be home; a song somewhat out of place amidst these melancholy dirges and a sorrowful prequel to the deceptively upbeat closer, "But Not Tonight." Here we find, not a house, but a song depicting those magical nights when you realize that life is about you and the universe, that the stars and the moon are billions of years old and all those societal expectations, responsibilities and anxieties are tiny in the grand scheme of things. You feel for a moment that a great weight has been lifted from your shoulders and you are wiser than you were just 5 minutes ago… BULLSHIT. It's not about that at all. “But Not Tonight” is the greatest of songs, of poems (take that Bysshe-Shelley!) about regret and denial, the lyrics diametrically opposed to Dave Gahan’s exceptional and heart-wrenching vocals. Black Celebration is an album of interpretation; one of those dichotomies in which the meaning of each song is so clearly apparent until you talk with someone else, and realize you were so very wrong. If it's not, that should be the definition of poetry.

Though Violator was Depeche Mode's greatest commercial success, Black Celebration was the group's most cohesive effort. A concept album that takes the listener on a journey through the societal underbelly of sex, drugs, depression and betrayal, it is a dark affair indeed. The title cut is a synth masterpiece, with eerie sounds building until the song explodes, the protagonist wailing, "Your optimistic guise/looks like paradise/to someone like/me..." - haunting. The album ebbs and flows between soundscapes and tempos that serve only to make it more unsettling. "Black Celebration" segues effortlessly into "Fly On The Windscreen - Final," seething with a sense of urgency that is suddenly scaled back by the sequencing of "A Question Of Lust," "Sometimes" and "It Doesn't Matter Two." The flip side carries on with the sexual tension of "A Question Of Time" and "Stripped" giving way to "Here Is the House," a beautiful contemplation of what it means to be home; a song somewhat out of place amidst these melancholy dirges and a sorrowful prequel to the deceptively upbeat closer, "But Not Tonight." Here we find, not a house, but a song depicting those magical nights when you realize that life is about you and the universe, that the stars and the moon are billions of years old and all those societal expectations, responsibilities and anxieties are tiny in the grand scheme of things. You feel for a moment that a great weight has been lifted from your shoulders and you are wiser than you were just 5 minutes ago… BULLSHIT. It's not about that at all. “But Not Tonight” is the greatest of songs, of poems (take that Bysshe-Shelley!) about regret and denial, the lyrics diametrically opposed to Dave Gahan’s exceptional and heart-wrenching vocals. Black Celebration is an album of interpretation; one of those dichotomies in which the meaning of each song is so clearly apparent until you talk with someone else, and realize you were so very wrong. If it's not, that should be the definition of poetry.

Published on June 17, 2018 05:16

June 16, 2018

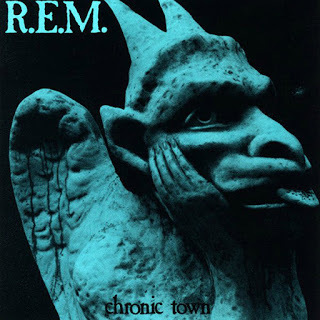

R.E.M. and the Incredible Shrinking Legacy

The word on the street (not sure which street) is that by not breaking up with the departure in 1997 of Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, and Mike Mills saddled their band with The Incredible Shrinking Legacy. With each passing year, R.E.M.'s piece of rock history real estate grew smaller. Honestly, when drunk at your favorite bar at 2am, is this the band you punch up on the jukebox? Are they even on there? Do I hear crickets? The question is WHY? When, in the 80s, it was poppy British new wave vs. hair metal (yeah, yeah, Smiths, New Order, gotcha), R.E.M. stayed the rock course. In an era where we're all ballyhoo over alt. folk and Americana, when Johnny Cash is god, R.E.M. should be revered as the defender of the faith. Reality, R.E.M is iconic. Not just to fans (those who remain), but to history. It's impossible to overstate the significance of the band. R.E.M. has influenced the very fabric of American culture, music, morality and politics. From its meager beginnings in small town Georgia to playing the biggest stages in the world, R.E.M. pulled off something nearly unthinkable: it maintained its integrity and kept making great American music.

The word on the street (not sure which street) is that by not breaking up with the departure in 1997 of Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, and Mike Mills saddled their band with The Incredible Shrinking Legacy. With each passing year, R.E.M.'s piece of rock history real estate grew smaller. Honestly, when drunk at your favorite bar at 2am, is this the band you punch up on the jukebox? Are they even on there? Do I hear crickets? The question is WHY? When, in the 80s, it was poppy British new wave vs. hair metal (yeah, yeah, Smiths, New Order, gotcha), R.E.M. stayed the rock course. In an era where we're all ballyhoo over alt. folk and Americana, when Johnny Cash is god, R.E.M. should be revered as the defender of the faith. Reality, R.E.M is iconic. Not just to fans (those who remain), but to history. It's impossible to overstate the significance of the band. R.E.M. has influenced the very fabric of American culture, music, morality and politics. From its meager beginnings in small town Georgia to playing the biggest stages in the world, R.E.M. pulled off something nearly unthinkable: it maintained its integrity and kept making great American music. Since 1980, the band was a constant. That's not to say that it never evolved. Both the band members and the music grew with grace, never repeating a proven formula, always claiming new ground. From the mid-tempo jangle on Murmur to the rock blast of Monster and on through the sun-soaked twinkling in Reveal, the band exhibited a remarkable ability to morph its sound while still retaining its essence.

Since 1980, the band was a constant. That's not to say that it never evolved. Both the band members and the music grew with grace, never repeating a proven formula, always claiming new ground. From the mid-tempo jangle on Murmur to the rock blast of Monster and on through the sun-soaked twinkling in Reveal, the band exhibited a remarkable ability to morph its sound while still retaining its essence. A shy poet and photographer, singer Michael Stipe seemed frequently uncomfortable in his roll on stage. At the band's early shows, he spent much of his time on stage hiding behind a big curtain of curly hair, but ended his tenure as a dancing, eyeliner-wearing, confident front man. Mike Mills on bass and keyboards added the absolutely essential R.E.M. backing vocals. His distinctive voice is one of the main pillars of the R.E.M. sound. Peter Buck is one of the most important rock guitarists and the man who plays that instantly recognizable mandolin. Hard times befell the band in 1997 with the departure of original drummer Bill Berry. This was a crucial, emotional time for the band. Still, its members remained like brothers. Berry, still recovering from a brain aneurysm, said that he would not quit unless the other three would continue on without him. After 17 years together, Stipe compared this to a three-legged dog learning to run again.

A shy poet and photographer, singer Michael Stipe seemed frequently uncomfortable in his roll on stage. At the band's early shows, he spent much of his time on stage hiding behind a big curtain of curly hair, but ended his tenure as a dancing, eyeliner-wearing, confident front man. Mike Mills on bass and keyboards added the absolutely essential R.E.M. backing vocals. His distinctive voice is one of the main pillars of the R.E.M. sound. Peter Buck is one of the most important rock guitarists and the man who plays that instantly recognizable mandolin. Hard times befell the band in 1997 with the departure of original drummer Bill Berry. This was a crucial, emotional time for the band. Still, its members remained like brothers. Berry, still recovering from a brain aneurysm, said that he would not quit unless the other three would continue on without him. After 17 years together, Stipe compared this to a three-legged dog learning to run again.It's impossible to hear "Losing My Religion," "The One I Love" or "Everybody Hurts" with fresh ears. These songs are so much a part of our lives that they've been unfairly relegated to the land of boring, played-out FM schmaltz, instead of standing as strong, statement-making singles as they were intended. But it's not the singles that reverberate timelessly, instead, songs like “Fall On Me,” “Radio Free Europe” and the beautiful “Nightswimming” are the tracks that should answer the why. Like Neil Young and Pearl Jam, R.E.M. are rock Americana.

Published on June 16, 2018 04:19

R.E.M.

One of the enigmatic aspects of Cocteau Twins was the indecipherability of the lyrics. One can pick out a "cherry cola" here and there, maybe, yet the decline of the conceptual trio was tantamount to annunciation; once we understood the lyrics, it was over (and we verily dismiss the last two LPs). The same is no doubt true of R.E.M. Comedian Stewart Lee gave an interview to the online magazine The Quietus and said, "I don't think there's anyone whose career trajectory has been so disappointing," he opined, "starting so brilliantly and ending up so dreadful. They're just awful."

R.E.M. buffs can argue the night away about when the decline began, but I even question a decline. Maybe instead (and AM is eternally optimistic), the early LPs were just that good, but if that sublimity is assessed, the decline happened way back, 1986, just after Lifes Rich Pageant (sic). Debut LP, Murmur, provides R.E.M. with its place on the greatest albums of the 80s list, but there's a pervasive sense that Lifes Rich Pageant may represent the band at their apex. The Guardian states that “they never sounded more perfectly poised. From opener "Begin the Begin" to the joyous closing cover of "Superman," Lifes Rich Pageant is an album imbued with a swaggering confidence absent from its murky predecessor, Fables of the Reconstruction, but with the mystery of their debut and follow-up still intact. There's a beautiful opacity about "Fall On Me" (AM10, single), a protest song that lures us in, not with the directness of its message, but the sumptuousness of its melody. Indeed, the lyrics, poignant as they are, don’t really matter, they don't guide the song but merely punctuate it, leaving the listener wondering joyously. From there it was all downhill.*

Afterparty, Radio City Music Hall, October 6, 1987, the Document Tour: Despite my dismay, LeeAnn was infatuated with Jefferson Holt; the lanky manager of R.E.M. didn't stand a chance. "Do I look all right?" I was so the last person to ask. Like a million bucks, I thought, but out loud I replied, "Yes, of course, fine." She never looked fine. It was like saying she looked presentable. I felt like Ducky in Pretty in Pink, like I should sing "Try a Little Tenderness," such was her ability to crush me like a petal.

Afterparty, Radio City Music Hall, October 6, 1987, the Document Tour: Despite my dismay, LeeAnn was infatuated with Jefferson Holt; the lanky manager of R.E.M. didn't stand a chance. "Do I look all right?" I was so the last person to ask. Like a million bucks, I thought, but out loud I replied, "Yes, of course, fine." She never looked fine. It was like saying she looked presentable. I felt like Ducky in Pretty in Pink, like I should sing "Try a Little Tenderness," such was her ability to crush me like a petal.

And then I met George. Not a coming out party; George was as hot as LeeAnn (not). She, yes she, thought I was Thomas Dolby (who am I to disagree?). Her superpower was that she could drink a whole bottle of beer without touching it with her hands. Hot (not as). I looked over. LeeAnn was tugging on Jefferson’s sleeve. She smiled at me. (Why?)

"You want to get out of here?" I didn’t hear her. "You want to get out of here?" George repeated in my ear. "I don’t know," I said in my mind. "Yes," I said, aloud.

To LeeAnn and Jefferson: "We’re taking off." LeeAnn: "You are? I don’t want to take the train by myself." Me: "I’m sorry." I spent the night with George (thank you, Thomas Dolby), and from there it was all downhill.

*I can hear the comments now about Automatic for the People (AM9), and it’s true – a 9 as a part of the downfall? And yet the disappointment is real; Automatic should be a 10. This acoustic album was subdued and beautiful; an LP about life knowing death is there in the same room. It is R.E.M.'s Rubber Soul, every song spot on; it fails only in its mid-tempo stall, yet imagine the album murmured by Stipe, the lyrics mumbled over and production values like Lifes Rich Pageant?

*I can hear the comments now about Automatic for the People (AM9), and it’s true – a 9 as a part of the downfall? And yet the disappointment is real; Automatic should be a 10. This acoustic album was subdued and beautiful; an LP about life knowing death is there in the same room. It is R.E.M.'s Rubber Soul, every song spot on; it fails only in its mid-tempo stall, yet imagine the album murmured by Stipe, the lyrics mumbled over and production values like Lifes Rich Pageant?

For this writer, R.E.M.'s decline begins with Document, bottoms out with Monster and recovers the extant of the band's career, but those glorious years of mumble, from the beginning through 1987, lead to Stewart Lee's dismay, leaving one with the constant question, what if only?

By the way, LeeAnn went home alone on the train. I never saw George again.

R.E.M. buffs can argue the night away about when the decline began, but I even question a decline. Maybe instead (and AM is eternally optimistic), the early LPs were just that good, but if that sublimity is assessed, the decline happened way back, 1986, just after Lifes Rich Pageant (sic). Debut LP, Murmur, provides R.E.M. with its place on the greatest albums of the 80s list, but there's a pervasive sense that Lifes Rich Pageant may represent the band at their apex. The Guardian states that “they never sounded more perfectly poised. From opener "Begin the Begin" to the joyous closing cover of "Superman," Lifes Rich Pageant is an album imbued with a swaggering confidence absent from its murky predecessor, Fables of the Reconstruction, but with the mystery of their debut and follow-up still intact. There's a beautiful opacity about "Fall On Me" (AM10, single), a protest song that lures us in, not with the directness of its message, but the sumptuousness of its melody. Indeed, the lyrics, poignant as they are, don’t really matter, they don't guide the song but merely punctuate it, leaving the listener wondering joyously. From there it was all downhill.*

Afterparty, Radio City Music Hall, October 6, 1987, the Document Tour: Despite my dismay, LeeAnn was infatuated with Jefferson Holt; the lanky manager of R.E.M. didn't stand a chance. "Do I look all right?" I was so the last person to ask. Like a million bucks, I thought, but out loud I replied, "Yes, of course, fine." She never looked fine. It was like saying she looked presentable. I felt like Ducky in Pretty in Pink, like I should sing "Try a Little Tenderness," such was her ability to crush me like a petal.

Afterparty, Radio City Music Hall, October 6, 1987, the Document Tour: Despite my dismay, LeeAnn was infatuated with Jefferson Holt; the lanky manager of R.E.M. didn't stand a chance. "Do I look all right?" I was so the last person to ask. Like a million bucks, I thought, but out loud I replied, "Yes, of course, fine." She never looked fine. It was like saying she looked presentable. I felt like Ducky in Pretty in Pink, like I should sing "Try a Little Tenderness," such was her ability to crush me like a petal.And then I met George. Not a coming out party; George was as hot as LeeAnn (not). She, yes she, thought I was Thomas Dolby (who am I to disagree?). Her superpower was that she could drink a whole bottle of beer without touching it with her hands. Hot (not as). I looked over. LeeAnn was tugging on Jefferson’s sleeve. She smiled at me. (Why?)

"You want to get out of here?" I didn’t hear her. "You want to get out of here?" George repeated in my ear. "I don’t know," I said in my mind. "Yes," I said, aloud.

To LeeAnn and Jefferson: "We’re taking off." LeeAnn: "You are? I don’t want to take the train by myself." Me: "I’m sorry." I spent the night with George (thank you, Thomas Dolby), and from there it was all downhill.

*I can hear the comments now about Automatic for the People (AM9), and it’s true – a 9 as a part of the downfall? And yet the disappointment is real; Automatic should be a 10. This acoustic album was subdued and beautiful; an LP about life knowing death is there in the same room. It is R.E.M.'s Rubber Soul, every song spot on; it fails only in its mid-tempo stall, yet imagine the album murmured by Stipe, the lyrics mumbled over and production values like Lifes Rich Pageant?

*I can hear the comments now about Automatic for the People (AM9), and it’s true – a 9 as a part of the downfall? And yet the disappointment is real; Automatic should be a 10. This acoustic album was subdued and beautiful; an LP about life knowing death is there in the same room. It is R.E.M.'s Rubber Soul, every song spot on; it fails only in its mid-tempo stall, yet imagine the album murmured by Stipe, the lyrics mumbled over and production values like Lifes Rich Pageant?For this writer, R.E.M.'s decline begins with Document, bottoms out with Monster and recovers the extant of the band's career, but those glorious years of mumble, from the beginning through 1987, lead to Stewart Lee's dismay, leaving one with the constant question, what if only?

By the way, LeeAnn went home alone on the train. I never saw George again.

Published on June 16, 2018 04:16

June 15, 2018

TfF

Great things happen in curious ways. Stephen King’s Carrie only saw the light of day because his wife Tabitha picked the manuscript out of the trash. Han Solo's "I know" to Princess Leia's "I love you" was gut instinct on behalf of Harrison Ford. While Tears for Fears' 1985 single "Everybody Wants to Rule the World" was a last-minute addition to their iconic sophomore album, Songs from the Big Chair, all thanks to two chords co-founder Roland Orzabal randomly played on his acoustic guitar for producer Chris Hughes. As the band's other half, Curt Smith, explained: "I came in one day, and they'd actually written this song around this beat and it was very commercial, so they said, 'Here it is, you’re singing it, go and do it.' So I did."

It's the sort of mind-bending folklore that chaos theoreticians might get off on. As a single for 1985, the UK outfit couldn’t have written a track more apropos for the times; it's a meditative commentary on an era that was so corrupt economically and spiritually, and the same was true in America – Less Than Zero was the catalyst; it wouldn’t be long until there was American Psycho.

"The shuffle beat was alien to our normal way of doing things," Orzabal explained. "It was jolly rather than square and rigid in the manner of 'Shout,' but it continued the process of becoming more extrovert." Smith explained that they "were basically coerced by the record company to go in and do something to release quickly after The Hurting was successful." Though the production of the single strayed from their atypical style of writing — "what we prefer to do is just go away and make our own records" — it certainly sparked something within them.

Lyrically, Songs from the Big Chair remains their most focused effort. Inspired by the book and mini-series Sybil, about a woman with multiple personality disorder who finds comfort in the "Big Chair," the title was "kind of an 'up yours' to the English music press who really fucked [the band] up for a while," as Smith explained. "This is us now — and they can't get at us anymore." As such, the album touches upon their surroundings, from dusty Cold War paranoia ("Shout") to the corruption of power ("Everybody Wants to Rule the World") to parental guidance ("Mother's Talk") to the uncontrollable emotions that romance warrants ("Head Over Heels"). In keeping with its titular themes, "The Working Hour" and "Listen" play to the modes of therapy.

30 years ago. I need some therapy.

It's the sort of mind-bending folklore that chaos theoreticians might get off on. As a single for 1985, the UK outfit couldn’t have written a track more apropos for the times; it's a meditative commentary on an era that was so corrupt economically and spiritually, and the same was true in America – Less Than Zero was the catalyst; it wouldn’t be long until there was American Psycho.

"The shuffle beat was alien to our normal way of doing things," Orzabal explained. "It was jolly rather than square and rigid in the manner of 'Shout,' but it continued the process of becoming more extrovert." Smith explained that they "were basically coerced by the record company to go in and do something to release quickly after The Hurting was successful." Though the production of the single strayed from their atypical style of writing — "what we prefer to do is just go away and make our own records" — it certainly sparked something within them.

Lyrically, Songs from the Big Chair remains their most focused effort. Inspired by the book and mini-series Sybil, about a woman with multiple personality disorder who finds comfort in the "Big Chair," the title was "kind of an 'up yours' to the English music press who really fucked [the band] up for a while," as Smith explained. "This is us now — and they can't get at us anymore." As such, the album touches upon their surroundings, from dusty Cold War paranoia ("Shout") to the corruption of power ("Everybody Wants to Rule the World") to parental guidance ("Mother's Talk") to the uncontrollable emotions that romance warrants ("Head Over Heels"). In keeping with its titular themes, "The Working Hour" and "Listen" play to the modes of therapy.

30 years ago. I need some therapy.

Published on June 15, 2018 04:43

June 14, 2018

Kick Out the Style, Bring Back the Jam

Every bit as influential as The Clash, The Jam is the most significant forgotten British band (despite 18 consecutive top 40 singles; four No. 1's). Even in the U.K., their impact and sway is overlooked, even dismissed (meanwhile the insufferable hype over Oasis remains pervasive). The Jam are as British as Heinz baked beans, and as essential.

Every bit as influential as The Clash, The Jam is the most significant forgotten British band (despite 18 consecutive top 40 singles; four No. 1's). Even in the U.K., their impact and sway is overlooked, even dismissed (meanwhile the insufferable hype over Oasis remains pervasive). The Jam are as British as Heinz baked beans, and as essential.Comparison to the mods (a youth faction that, like the Teddy Boys, isn't a part of American cultural literacy) is inevitable, yet the Jam were far from a mod cover band, they were a punk reflection of it, and All Mod Cons (AM7) and Setting Sons (AM6) are exposes on a troubled Thatcher-era London. All Mod Cons, in particular, is a frightening album of urban decay and decline, an atmospheric trip around the forsaken midnight city streets told through punk and pop, acoustic and mod influences. This was the modern world.

Behind me/ Whispers in the shadows, gruff blazing voices/ Hating, waiting/ "Hey boy" they shout,/ "have you got any money?"/ And I said, "I've a little money and a take away curry,/I'm on my way home to my wife./She'll be lining up the cutlery,/You know she's expecting me/Polishing the glasses and pulling out the cork"/ And I'm down in the tube station at midnight.

Not released on any album, "Going Underground" was the Jam's first No. 1 single. It went straight to No. 1 and stayed there three weeks. The Kinks with switchblades, "Going Underground" combines a heady, irresistible admix of aggression and melody in a way unique to punky British new wave; this is Weller & Co. at the top of their game.

Even a cursory listen to Sound Affects (AM7) will strengthen the seemingly endless Revolver comparisons, but these are superficial at best. WhereasRevolver is generally an optimistic jawn, Sound Affects is claustrophobic and urban, not as inventive asRevolver but still very, very stylish. Sound Affects doesn't have quite the bite or the topical sense of All Mod Cons, yet with the exception of "That's Entertainment," the album’s standout track, this is a gritty post-punk affair.

Two lovers kissing amongst the scream of midnight./ Two lovers missing the tranquility of solitude./ Getting a cab and traveling on buses,/ Reading the graffiti about slashed seat affairs … That's entertainment...

Two lovers kissing amongst the scream of midnight./ Two lovers missing the tranquility of solitude./ Getting a cab and traveling on buses,/ Reading the graffiti about slashed seat affairs … That's entertainment...Haven't heard The Jam, check these out first: "The Modern World," "English Rose," "David Watts" (Kinks cover), "Down in a Tube Station at Midnight," "Going Underground," "Start," "That's Entertainment" and "The Bitterest Pill." But why haven't you? Doesn't even make any sense.

Published on June 14, 2018 05:14

June 13, 2018

Punk Vs. New Wave

Breathless - The French New WavePunk is easily definable, if not in words then in context. There's a simple narrative connecting surf and garage to three chord punk debauchery. Still, the genre is more definable by what it's not, so let's not and move on. New Wave on the other hand is less succinct, more difficult to pin down. The term's catalyst of course is French New Wave cinema which, like Fauvism and Impressionism in the art world, nixed the academic, rejecting classic filmic technique. This often leads to confusion, alongside the use of the term in the early days of Punk, when "Punk" had not yet risen to the platitude of genre. Indeed Malcolm McLaren, the poet laureate of all things Punk, insisted, before The Sex Pistols had ever recorded a note, that the music be referred to as New Wave (not long after, McLaren rejected the term). If that wasn't enough, the genre itself was compartmentalized long before the term became the catchall phrase we use today. By 1978, a plethora of sub-genres had emerged: No-Wave, New Romanticism, Art Rock, Synth-Pop, Ska. San Francisco based Chrome decided to "Mix our punk shit with weird, acid shit… Let's call it Acid Punk." Sums it up.

Breathless - The French New WavePunk is easily definable, if not in words then in context. There's a simple narrative connecting surf and garage to three chord punk debauchery. Still, the genre is more definable by what it's not, so let's not and move on. New Wave on the other hand is less succinct, more difficult to pin down. The term's catalyst of course is French New Wave cinema which, like Fauvism and Impressionism in the art world, nixed the academic, rejecting classic filmic technique. This often leads to confusion, alongside the use of the term in the early days of Punk, when "Punk" had not yet risen to the platitude of genre. Indeed Malcolm McLaren, the poet laureate of all things Punk, insisted, before The Sex Pistols had ever recorded a note, that the music be referred to as New Wave (not long after, McLaren rejected the term). If that wasn't enough, the genre itself was compartmentalized long before the term became the catchall phrase we use today. By 1978, a plethora of sub-genres had emerged: No-Wave, New Romanticism, Art Rock, Synth-Pop, Ska. San Francisco based Chrome decided to "Mix our punk shit with weird, acid shit… Let's call it Acid Punk." Sums it up.As a devotee of Joy Division, I equate the move from Punk to New Wave with the release of Unknown Pleasures (AM10), an essentially punk release accentuated with the synthesizer, a punk exclusion. The two distinct genres nonetheless developed side by side with New Wave taking on an open, far less dense sensibility that stripped bare the guitar of distortion and placed an emphasis on a single note rather than the chord. It may come down to the difference between a pick and strum, with any New Wave chording more closely associated with the jangly feel of the jazz guitar. The extreme of New Wave would of course dismiss the use of traditional instrumentation all together, a feat accomplished by early Depeche Mode, Gary Numan, The Human League and Soft Cell, with the predominant use of synth styled drum machines programmed like a metronome.

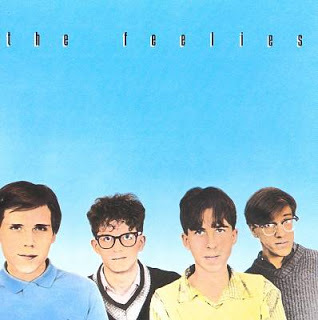

It's a simple task to categorize The Germs, The Sex Pistols, Circle Jerks, Dead Kennedys and The Misfits as Punk; just as simple to quickly name DM, Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark and Scritti Politti as New Wave, but where and how, then, to categorize The Clash's venture into Reggae or The Feelies' Punk Lite approach. The Feelies were among the bands that focused on translating the emotional tension of the in-betweens into a new song format. Formed in New Jersey by Glenn Mercer and Bill Million, they were a quiet, shy outfit that rarely behaved like a rock band, thus predating the snobby/hipster attitude of college-pop and bands like Weezer. 1977's Crazy Rhythms was unique, imbued with a controlled frenzy that employed psychedelic guitars, trance-like vocals, repetition of patterns and hypnotic beats. The resulting sound was hermetic, almost extraterrestrial. Songs shared an ascetic and a geometric quality that recalled Zen meditation rather than punk-rock. The mood was halfway between ecstatic transcendence and detached decadence. (Too much?) So where did it fit in?

It's a simple task to categorize The Germs, The Sex Pistols, Circle Jerks, Dead Kennedys and The Misfits as Punk; just as simple to quickly name DM, Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark and Scritti Politti as New Wave, but where and how, then, to categorize The Clash's venture into Reggae or The Feelies' Punk Lite approach. The Feelies were among the bands that focused on translating the emotional tension of the in-betweens into a new song format. Formed in New Jersey by Glenn Mercer and Bill Million, they were a quiet, shy outfit that rarely behaved like a rock band, thus predating the snobby/hipster attitude of college-pop and bands like Weezer. 1977's Crazy Rhythms was unique, imbued with a controlled frenzy that employed psychedelic guitars, trance-like vocals, repetition of patterns and hypnotic beats. The resulting sound was hermetic, almost extraterrestrial. Songs shared an ascetic and a geometric quality that recalled Zen meditation rather than punk-rock. The mood was halfway between ecstatic transcendence and detached decadence. (Too much?) So where did it fit in?Along that line of questioning, the most celebrated musician to emerge from the confusion was Elvis Costello. The quintessential "angry young man" incorporated a Buddy Holly look and feel with a quirky delivery and a vast spectrum of styles (the anthemic "Less Than Zero," the romantic ballad "Alison," the eccentric reggae of "Watching The Detectives"). The early singles led to the pub-rock of This Year's Model and to the 60s camouflage of Armed Forces, all before the end of '79. These albums were typical of Costello's ambiguity: subtly attacking the Establishment while openly endorsing its soundtrack. It wasn't a caricature, it was a full-hearted endorsement of Tin Pan Alley's aesthetic. Did it fit anywhere?

What never ceases to amaze is that in 1979 and 1982, amidst the diversity of the New – from The Angry Samoans to Duran Duran to Combat Rock, Pink Floyd's The Wall would manage to top the charts. I'm enamored by the digital age progressive rock of Steven Wilson, the singer songwriters like Andrew McMahon and Rivers Cuomo and the genius of Beck, but God, you gotta miss that.

Published on June 13, 2018 05:02

The Only Band That Matters

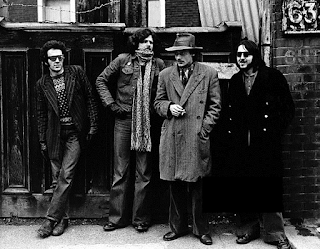

The 101ersFormed as the first shots of the punk revolution were fired, The Clash stormed onto the British scene with their debut performance on July 4, 1976, at The Black Swan in Sheffield, England, as the opening act for The Sex Pistols. While America celebrated the Bicentennial anniversary of its independence from Britain, the U.K. was in the midst of another revolution, this one staged on its very own shores. One eyewitness was Joe Strummer, then the frontman of a popular pub-rock band called the 101ers. Before a gig at a London club called the Nashville Room in April 1976, he watched as that night's opening act took the stage: "Five seconds into their first song, I just knew we were like yesterday's papers. I mean, we were over." The group was The Sex Pistols, and their effect on Strummer was life-altering. Within weeks, he'd accepted an invitation from guitarist Mick Jones and bassist Paul Simonon to leave the 101ers and join their as-yet-unnamed and drummer-less new band. Together, the three of them would form the core of a group their fans would call, with all sincerity, The Only Band That Matters. If you're doing the math, it took just three months for that catalytic first gig to be actualized.

The 101ersFormed as the first shots of the punk revolution were fired, The Clash stormed onto the British scene with their debut performance on July 4, 1976, at The Black Swan in Sheffield, England, as the opening act for The Sex Pistols. While America celebrated the Bicentennial anniversary of its independence from Britain, the U.K. was in the midst of another revolution, this one staged on its very own shores. One eyewitness was Joe Strummer, then the frontman of a popular pub-rock band called the 101ers. Before a gig at a London club called the Nashville Room in April 1976, he watched as that night's opening act took the stage: "Five seconds into their first song, I just knew we were like yesterday's papers. I mean, we were over." The group was The Sex Pistols, and their effect on Strummer was life-altering. Within weeks, he'd accepted an invitation from guitarist Mick Jones and bassist Paul Simonon to leave the 101ers and join their as-yet-unnamed and drummer-less new band. Together, the three of them would form the core of a group their fans would call, with all sincerity, The Only Band That Matters. If you're doing the math, it took just three months for that catalytic first gig to be actualized. That first live gig had its predictable rough patches, but their enthusiasm and commitment were there from the start, as were their unique musical and visual aesthetics. The Clash were instantly distinguishable from the Pistols by virtue of their sincere political bent, one that wasn't just a part of the problem, but a part of the solution. While The Sex Pistols sneered and preached anarchy, there was always a barely disguised element of lazy hucksterism in their social agenda. The Clash, on the other hand, quickly established themselves as the zealous and decidedly un-soft advocates of leftist causes. As U2 guitarist, The Edge later wrote, "This wasn’t just entertainment. It was a life-and-death thing. They made it possible for us to take our band seriously. It was the call to wake up, get wise, get angry, get political and get noisy about it."

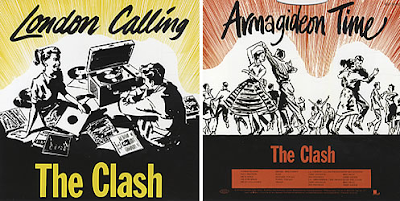

That first live gig had its predictable rough patches, but their enthusiasm and commitment were there from the start, as were their unique musical and visual aesthetics. The Clash were instantly distinguishable from the Pistols by virtue of their sincere political bent, one that wasn't just a part of the problem, but a part of the solution. While The Sex Pistols sneered and preached anarchy, there was always a barely disguised element of lazy hucksterism in their social agenda. The Clash, on the other hand, quickly established themselves as the zealous and decidedly un-soft advocates of leftist causes. As U2 guitarist, The Edge later wrote, "This wasn’t just entertainment. It was a life-and-death thing. They made it possible for us to take our band seriously. It was the call to wake up, get wise, get angry, get political and get noisy about it."It took some months following their debut gig for the Clash to work out the kinks and find Topper Headon (drums), who would complete their definitive lineup. Even 25 years later, Joe Strummer could still quote nearly verbatim one of their early reviews: "The Clash are one of those garage bands who should be swiftly returned to the garage, with the doors locked and with the motor left running." Undiscouraged, the Clash released an acclaimed, self-titled debut album in the spring of 1977, and over the next two-and-a-half years, they released a second album, Give 'Em Enough Rope (1978), that was Rolling Stone's pick for album of the year, and a third, London Calling (1979), that the same magazine chose as the ultimate LP of the 1980s.

The band’s first single “White Riot” was as punk as punk gets, demanding "a riot of our own," but even by the time their debut LP came around, they were embracing reggae and generally proving more musically visionary than their contemporaries, embracing the idea of punk as a liberating force, not a studded creative straitjacket. They were the existentialists to the Pistols' nihilism, a band who wanted to rebuild the world rather than cavort gleefully in its ruins. And so, while punk devolved into fundamentalism, a home for a gazillion bands with mohawks who mistook the "Here's three chords, now form a band" idea for a veneration of ineptitude and ignorance, The Clash expanded their horizons.

London Calling and Sandinista!, in particular, took the idea of deconstructing music and ran with it, finding the band romping adeptly through the history of rock 'n' roll. And, just as unfashionably, the band had something to say. Earnestness has long been seen as a death sentence in pop music, the polar opposite of a rock stance that's too cool to care about anything at all. But for a while, The Clash managed to transcend this, singing about the Spanish Civil War and capitalist alienation and a wealth of other topics, and did it with a degree of eloquence and intelligence that would be lost on the majority of their contemporaries.

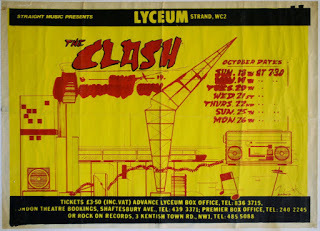

For me, The Clash remain a band of the era, difficult to embrace in our post-millennial world. The issues remain, but even London Calling loses something in the time translation. Doesn't matter; The Clash weren't about vinyl, but about being there, and for me, though it was just once, it was one of those moments "come unstuck in time." The Roxy, April 27, 1980. Oh my God, "Stay Free," "Somebody Got Murdered," "Safe European Home," Kenya crying that they didn't do "Lost in a Supermarket," everyone tripping. This was the venue where, not more than a month later, Rickie Lee Jones and Tom Waits accused me of stealing Rickie's beret, where The Go-Go's played on Sundays, where Darby Crash used my head instead of the banister while Laura gave me head on the stairs - I loved the Roxy). The Clash are a fixture of my nostalgia and all I have to hear is "Tommy Gun" and I'm right back there taking Laura by the hand, "Come on. Let's go back stage."

For me, The Clash remain a band of the era, difficult to embrace in our post-millennial world. The issues remain, but even London Calling loses something in the time translation. Doesn't matter; The Clash weren't about vinyl, but about being there, and for me, though it was just once, it was one of those moments "come unstuck in time." The Roxy, April 27, 1980. Oh my God, "Stay Free," "Somebody Got Murdered," "Safe European Home," Kenya crying that they didn't do "Lost in a Supermarket," everyone tripping. This was the venue where, not more than a month later, Rickie Lee Jones and Tom Waits accused me of stealing Rickie's beret, where The Go-Go's played on Sundays, where Darby Crash used my head instead of the banister while Laura gave me head on the stairs - I loved the Roxy). The Clash are a fixture of my nostalgia and all I have to hear is "Tommy Gun" and I'm right back there taking Laura by the hand, "Come on. Let's go back stage."Go easy, step lightly, Stay Free...

When I left L.A., I was listening to Gentle Giant and Jetro Tull, "Bohemian Rhapsody" was on the radio - so it was 40 years ago. My parents, meaning my mother and my step, were done with L.A., and my father'd already moved on, opened his studio in an old 5 & Dime in Jerome, Arizona (a ghost town resurrected by the art community), and he didn't have the time for me. I didn't want to go. Nicki Onstad was my first girl and she'd taught me things, lot of firsts revolve around my meeting Nicki, and I can still hear her today. "I just love marijuana." It was a part of the last conversation we had, the night before all our shit was crammed into a Dodge Dart and we drove off leaving L.A. behind. I was 16.

I wrote to her, sent her postcards, and I called from Yuma, Arizona and Fort Stockton, Texas; from the middle of nowhere. I was the one who left, but she'd already moved on. There was, nonetheless, this sense of sabotage in the back of my mind that the whole scheme to leave L.A. would implode, and we'd be back and Nicki and I would get high and stay that way happily ever after. In the meantime it was the back seat of the Dodge all to myself, like a traveling wigwam, me and my music and the Indian blanket my Father bought me in Monument Valley. I had four 8-Track tapes I'd made: Tull, Yes, ELP. The end of an era.

In 1980, I went home. Three years passed. I saved the money to buy a pale yellow 1973 Austin America. I took I10 all the way to Hollywood and checked into a cheap motel on La Cienega; then I drove straight to Sunset Blvd. It was a crisp, cool March evening and the billboards were lit up, yet everything had changed; it wasn't mine anymore. The sounds and visions in my head were somewhere in between 1968 and 1976. This was L.A. Where were the singer/songwriters driving old Porsches down from Laurel Canyon? Where were the GTOs? Hell, where was David Crosby? The billboards were lit up, but L.A. was dark. Punk made its mark and my Stoned-Pony hippie town gave way to X, The Plugs, Circle Jerks, and an assortment of post-punk jittery, hopped-up slam bands. Metallica was playing The Starwood. There was an erotic bakery next to the Whiskey. Piercings and black leather were everywhere (there wasn't a jeans jacket to be found). Clearly I'd have to adjust.

I called a girl I'd known since Van Nuys High, the singer in a band called Ella and the Blacks. I crashed at her apartment for a month, until she go sick of it. I contemplated leaving again, my city had turned its back. Then, on a Saturday in April at Danny's Oki-Dog, I met Kenya and Cathy and Laura. They were on the list at the Roxy; did I want to go? They liked my car. They needed a ride. The band was The Clash. The sun was going down on a hazy L.A. Fuck yeah, city in the smog, city in the smog; don't you wish that you could be here, too?

Published on June 13, 2018 04:16