R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 71

May 27, 2018

Fac

Some things are fabulous for a day, they snag their fifteen minutes and that's cool enough, but then there are Beatles and Coco Chanel, Audrey Hepburn and Truman Capote. Things iconic range from The Tempest to Death Cab. 400 years separate Ben Gibbard and Shakespeare, but not for me. Each is perfect.

Some things are fabulous for a day, they snag their fifteen minutes and that's cool enough, but then there are Beatles and Coco Chanel, Audrey Hepburn and Truman Capote. Things iconic range from The Tempest to Death Cab. 400 years separate Ben Gibbard and Shakespeare, but not for me. Each is perfect. The 80s were my era, and I was lucky enough to have embraced them and to have squeezed out the sublime (the quality of greatness), a huge part of which was Joy Division, a band that would become, following the death of singer/songwriter Ian Curtis, New Order. The music was dark and self-absorbed, dance-able, infectious and all consuming. New Order invented self-absorption, not to mention club music, sampling, bass lines as melody, and the automobile (maybe I exaggerate).

Factory Records emerged from out of a club of the same name in 1978. A year later, Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus were joined by Peter Saville and Martin Hannett to form Factory Records, and released their first EP, A Factory Sampler in 1979.

Factory Records emerged from out of a club of the same name in 1978. A year later, Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus were joined by Peter Saville and Martin Hannett to form Factory Records, and released their first EP, A Factory Sampler in 1979. The first LP released by Factory was Unknown Pleasures (Fac10) in 1979. The album received critical acclaim, the band subsequently appearing on the cover of NME and on the BBC's Peel Sessions; the album cover becoming as iconic as Sgt. Pepper. (Although the Factory emphasis is always on JD and NO, Factory Records signed Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark ("Electricity," Fac6), the Durutti Column and A Certain Ratio.)

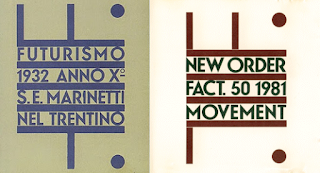

The 1980s were graphic art's heyday and Peter Saville turned album covers into artwork. You wanted to hang them on the wall or carry them around. They were stark and industrial, a symbol of a new digital age, of things that didn't exist before. They are so iconic and intrinsically aesthetic that Microsoft commissioned the artist to create the first in a line of limited edition Zune mp3 players utilizing the Unknown Pleasures album cover. (Many of you, of course, don’t even know what a Zune is.) Note the Movement album cover sitting side by side with the original art deco design from Fotunato Depero in the 1920s. I think it was TS (Tough Shit) Eliot who said, "Good writers borrow. Great writers steal." I guess it holds true for artwork as well. Saville would go on to capture more of Depero's work as his folio of Factory Records covers was assembled. Factory Records, New Order and Peter Saville made artwork and design an integral part of 80s music; design that speaks for itself.

The images that Peter Saville created for Joy Division, New Order and, later, Suede and Pulp were so compelling that they struck the same emotional resonance with the people who bought those albums and singles as the music. Just as the musicians in those bands wrote and produced their songs as catalogs of their thoughts and feelings, so Saville has conceived his images – for fashion and art projects as well as music – as visual narratives of his life.

Born in Manchester in 1955, Saville was brought up in the affluent suburb of Hale. Having been introduced to graphic design with his friend Malcolm Garrett by Peter Hancock, their sixth form art teacher, Saville decided to study graphics at Manchester Polytechnic, where he was soon joined by Garrett. At the time Saville was obsessed by bands like Kraftwerk and Roxy Music, but Garrett encouraged him to discover the work of early modern movement typographers such as Herbert Bayer and Jan Tschichold. He found their elegantly ordered aesthetic more appealing than the anarchic style of punk graphics. Tschichold was the inspiration for Saville’s first commercial project, the 1978 launch poster for The Factory, a club night run by a local TV journalist Tony Wilson whom he had met at a Patti Smith gig. Having long admired the ‘found’ motorway sign on the cover of Kraftwerk’s Autobahn, the first album he bought for himself, Saville based the Factory poster on a found object of his own – an industrial warning sign he had stolen from a door at college.

Published on May 27, 2018 05:34

May 26, 2018

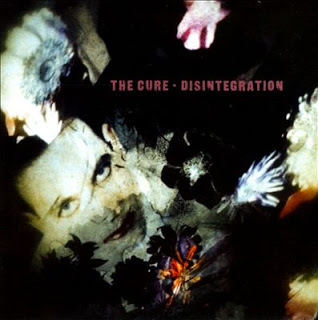

The Cure - Disintegration

In the same way that Fun's "We Are Young" isn't about being young, The Great Gatsby isn't about the recklessness of youth, but the recklessness at the end of youth; it's less about pursuing the dream than when dreams begins to fray. The moment that Gatsby has Daisy in his grasp is the moment when the green light - the symbol of his youthful desires - loses its luster: "His count of enchanted objects had diminished by one," Nick Carraway croons, with the dread promise of more to follow. The members of Fun had turned 30 when they sang "We Are Young," as had Nick at the novel's climax: "I was thirty. Before me stretched the portentous, menacing road of a new decade... Thirty - the promise of a decade of loneliness, a thinning list of single men to know, a thinning brief-case of enthusiasm, thinning hair." That's about as brutal a sentences as any 30-year-old can stand. Similarly, The Cure's Disintegration was conceived during the annus horribilis of Robert Smith. In April 1988 he'd hit 29, and was depressed and obsessed with delivering a "masterpiece" before the big 3-0.

In the same way that Fun's "We Are Young" isn't about being young, The Great Gatsby isn't about the recklessness of youth, but the recklessness at the end of youth; it's less about pursuing the dream than when dreams begins to fray. The moment that Gatsby has Daisy in his grasp is the moment when the green light - the symbol of his youthful desires - loses its luster: "His count of enchanted objects had diminished by one," Nick Carraway croons, with the dread promise of more to follow. The members of Fun had turned 30 when they sang "We Are Young," as had Nick at the novel's climax: "I was thirty. Before me stretched the portentous, menacing road of a new decade... Thirty - the promise of a decade of loneliness, a thinning list of single men to know, a thinning brief-case of enthusiasm, thinning hair." That's about as brutal a sentences as any 30-year-old can stand. Similarly, The Cure's Disintegration was conceived during the annus horribilis of Robert Smith. In April 1988 he'd hit 29, and was depressed and obsessed with delivering a "masterpiece" before the big 3-0.  In some ways, Smith's despondency was at odds with the The Cure's status as a globally-renowned alternative rock band. Their previous LP, 1987's poppy though melancholy Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me was a celebration of the band's first decade and helped The Cure crack mainstream America, the ultimate prize. Robert Smith, however, was not a happy puppy. Believing that most bands delivered their masterpiece by the time they were thirty, he set about writing "the most intense thing The Cure have ever done." In many ways, Disintegration was the prototype of a Robert Smith solo album. "I would have been quite happy to make those songs on my own, if that band hadn't liked them."

In some ways, Smith's despondency was at odds with the The Cure's status as a globally-renowned alternative rock band. Their previous LP, 1987's poppy though melancholy Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me was a celebration of the band's first decade and helped The Cure crack mainstream America, the ultimate prize. Robert Smith, however, was not a happy puppy. Believing that most bands delivered their masterpiece by the time they were thirty, he set about writing "the most intense thing The Cure have ever done." In many ways, Disintegration was the prototype of a Robert Smith solo album. "I would have been quite happy to make those songs on my own, if that band hadn't liked them." The atmosphere around him was particularly toxic. Smith was in a depressed, non-communicative state ("one of my non-talking modes"), as he fretted over creating an LP that contained the doom-laden gravitas of 1982's brilliant Pornography. "I actually wanted an environment that was unpleasant," he recalled, and a combination of his own truculence and keyboard player Lol Tolhurst's raging alcoholism ensured that the creation of Disintegration was a miserable experience. (Smith was concerned that his old school friend would steadily drink himself to death, and despite Tolhurst attending a brief stint in rehab, things came to a head during a mixing session for Disintegration at RAK Studios in London, during which Smith and a drunk Tolhurst had a stormy exchange, Lol expressing his oblique dissatisfaction with the LP.)

Tolhurst was sacked in February 1989 and replaced by Roger O'Donnell, a more proficient keyboardist whose cinematic use of "walls of synthesizers" would become the cornerstone of the record's dense, cakey feel, from the Gothic funeral/wedding march in the opening mood-setter "Plainsong," onward.

The LP's first single, "Lullaby," is perfectly twisted pop for which Smith took inspiration from creepy lullabies his own father sang to him. The song's video, directed by Tim Pope, is an arachnophobic vision of hell in which Smith is eaten by a giant spider. Yep, quite the lullaby.

The LP's first single, "Lullaby," is perfectly twisted pop for which Smith took inspiration from creepy lullabies his own father sang to him. The song's video, directed by Tim Pope, is an arachnophobic vision of hell in which Smith is eaten by a giant spider. Yep, quite the lullaby. Visceral self-flagellation is at the core of Disintegration. The dense "Closedown" is a laundry list of personality failings, while the portentous "Last Dance" aches with memories of fleeting happiness. Even the pristine "Pictures Of You" – a positively upbeat ditty (relative of course to the surrounding gloom) – saw Smith chiding himself about failed relationships ("If only I'd thought of the right words/ I could have held onto your heart"), and while his desire to torment himself via lyrics wasn't a new concept, Disintegration saw Smith perfect the craft of self-mutilation.

Amid the turmoil, though, is a moment of redemption. "Lovesong" is indeed a straight up love song that Smith wrote to his wife, Mary Poole. The couple married in August 1988, and the song was a wedding gift. "I couldn't think of what to give her," Smith would later (half) joke about a song that sounded at odds with the rest of the album. "It took me ten years to get to the point where I felt comfortable singing a straightforward love song." Yet even "Lovesong" revealed the scars that fueled Disintegration, the obsession of approaching 30 ("Whenever I'm alone with you / You make me feel like I am young again.").

While The Cure's American record label (Elektra) hated Disintegration on first listen ("There was just this look of absolute dismay on their faces," Smith confirmed), the album was a worldwide hit. Selling in excess of 3 million copies, Disintegration ensured that despite Smith's best efforts The Cure had "become everything I didn't want us to become - a stadium rock band." And a miserable stadium rock band at that. Chris Roberts' glowing Melody Maker review offered up a perplexing conundrum: "How can a group this disturbing and depressing be so popular?" Pretty easily, if the truth be known, and Roberts needn't have looked further than the peerless title track. Clocking in at eight-and-a-half minutes, "Disintegration" is a sprawling, reeling act of desperation, on which Smith unlocked a Pandora's Box of self-loathing. "I miss the kiss of treachery/ The shameless kiss of vanity," he begins before lurching into "I never said I would stay to the end/ I knew I would leave you with babies and everything," a line I always felt particularly harsh on his newlywed status. By the song's heart stopping crescendo, the singer seemed to be bumping along rock bottom as he screams, "Now that I know that I'm breaking to pieces/ I'll pull out my heart and feed it to anyone."

My mother was a back-up singer for the likes of Burt Bacharach and Ray Conniff, and so music was a constant in our lives. I recall having an 8-track player in our Ford Falcon and my mother playing only one side of People by Barbra Streisand. The title song was on Side 4 with "Love is a Bore" and "Don't Like Goodbyes" (an unusual Harold Arlen song with lyrics by Truman Capote). My mother would skip sides 1-3 and we'd listen to Side 4 over and over, just so that she could sing "People." It wasn't long afterwards that she got a new old car with a cassette, and she'd play "People" and rewind and say, "Listen to this part." It was when I realized the power of rewind; it was when I realized that little bits of songs, snippets of melody or vocals, could have such an impact. Since then I've listened to music that way: rewinding. Disintegration is that album on which every rewind reveals something new, something unexpected or something else sublime, about People.

Published on May 26, 2018 05:29

Disintegration

Never has misery sounded so hauntingly beautiful as on Disintegration, a mopey masterpiece that many consider among the greatest LPs of all time (this writer included). In mood the album is a confident, elaborate, evolution of 1981's Faith, dealing with those oft-mined themes of loss, despair and being eaten by giant spiders, yet this is an altogether new type of bleakness, blackness, distortion; a listening experience akin to being submerged by wave upon wave of melancholia. A daunting 70-minutes in length, Disintegration begins with the hypnotic wind chimes of "Plainsong," and lulls the listener in with the relatively radio-friendly single "Pictures of You" before dragging us further into the darkness with every passing track. By the time we reach "The Same Deep Water as You" and "Prayers for Rain" at the heart of the album, both epic, dense in sound and each weighing in at around seven minutes, we're completely submerged. (Anyone who is not should have their black mascara confiscated.) Few albums hammer home an atmosphere as thoroughly as this one, injecting hopelessness into your veins like a drug you've always craved, yet, somehow, this album doesn't make you want to slash your wrists; the music so fascinating, so unstoppable in its circling, extended anthems, it begs you instead to join so relentlessly that one takes comfort in the hurt rather than seeking relief from the pain. Wonderful, thick, beautiful stuff. Sad, bitter tales can comfort us, too.

Never has misery sounded so hauntingly beautiful as on Disintegration, a mopey masterpiece that many consider among the greatest LPs of all time (this writer included). In mood the album is a confident, elaborate, evolution of 1981's Faith, dealing with those oft-mined themes of loss, despair and being eaten by giant spiders, yet this is an altogether new type of bleakness, blackness, distortion; a listening experience akin to being submerged by wave upon wave of melancholia. A daunting 70-minutes in length, Disintegration begins with the hypnotic wind chimes of "Plainsong," and lulls the listener in with the relatively radio-friendly single "Pictures of You" before dragging us further into the darkness with every passing track. By the time we reach "The Same Deep Water as You" and "Prayers for Rain" at the heart of the album, both epic, dense in sound and each weighing in at around seven minutes, we're completely submerged. (Anyone who is not should have their black mascara confiscated.) Few albums hammer home an atmosphere as thoroughly as this one, injecting hopelessness into your veins like a drug you've always craved, yet, somehow, this album doesn't make you want to slash your wrists; the music so fascinating, so unstoppable in its circling, extended anthems, it begs you instead to join so relentlessly that one takes comfort in the hurt rather than seeking relief from the pain. Wonderful, thick, beautiful stuff. Sad, bitter tales can comfort us, too.Hellish and heavenly, urban and pastoral, Disintegration was meant to satisfy Smith's urge to create "something autumnal" — a study in muted atmosphere suspended in twilight. Often pegged as monochromatic, Disintegration has only grown more subtly shaded — and lingeringly complex — over time.

"Plainsong" veers straight ahead into The Cure’s darkest, most depressive writings since Pornography. "'I think it's dark and it looks like rain,' you said./ 'And the wind is blowing like it's the end of the world,' you said./ 'And it's so cold it's like the cold if you were dead," and then you smiled for a second." Depressing to the point of ennui, but for the tag, "Then you smiled for a second." So painfully beautiful, like Barber’s Adagio or Rickie Lee Jones' "Company." One need not critique another track, as each is this good, each following a path that the cure embraced so skillfully, the extended, atmospheric intro. We'd heard it before, all the way back to Seventeen Seconds and as recently as Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me's "A Thousand Hours" and "Just One More Kiss," but here the intro is perfected. "Plainsong" refers to a type of music, a body of traditional songs which used the liturgies of the Roman Catholic church, "a monophonic consisting of a single, unaccompanied melodic line. It often uses the lengthy reverberations and resonant modes of cathedrals to create harmonies," which explain’s the lengthy reverberations and resonant modes for the Cure's rendition. I don’t know about monophonic, but certainly something cathedral-like and gothic has infused the atmosphere of Disintegration from this very first dark step. One of the greatest opening songs ever.

"Plainsong" veers straight ahead into The Cure’s darkest, most depressive writings since Pornography. "'I think it's dark and it looks like rain,' you said./ 'And the wind is blowing like it's the end of the world,' you said./ 'And it's so cold it's like the cold if you were dead," and then you smiled for a second." Depressing to the point of ennui, but for the tag, "Then you smiled for a second." So painfully beautiful, like Barber’s Adagio or Rickie Lee Jones' "Company." One need not critique another track, as each is this good, each following a path that the cure embraced so skillfully, the extended, atmospheric intro. We'd heard it before, all the way back to Seventeen Seconds and as recently as Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me's "A Thousand Hours" and "Just One More Kiss," but here the intro is perfected. "Plainsong" refers to a type of music, a body of traditional songs which used the liturgies of the Roman Catholic church, "a monophonic consisting of a single, unaccompanied melodic line. It often uses the lengthy reverberations and resonant modes of cathedrals to create harmonies," which explain’s the lengthy reverberations and resonant modes for the Cure's rendition. I don’t know about monophonic, but certainly something cathedral-like and gothic has infused the atmosphere of Disintegration from this very first dark step. One of the greatest opening songs ever.In the same way that Fun's "We Are Young" isn't about being young, The Great Gatsby isn't about the recklessness of youth, but the recklessness at the end of youth. The moment when Gatsby has Daisy in his grasp is the moment when the green light - the symbol of his youthful desires - loses its luster: "His count of enchanted objects had diminished by one," Nick Carraway croons, with the dread promise of more to follow. The members of Fun had turned 30 when they sang "We Are Young," as had Nick at the novel's climax: "I was thirty. Before me stretched the portentous, menacing road of a new decade... Thirty - the promise of a decade of loneliness, a thinning list of single men to know, a thinning brief-case of enthusiasm, thinning hair." That's about as brutal a sentences as any 30-year-old can stand. Similarly, The Cure's Disintegration was conceived during the annus horribilis of Robert Smith. In April 1988 he'd hit 29, and was depressed and obsessed with delivering a "masterpiece" before the big 3-0.

In some ways, Smith's despondency was at odds with the The Cure's status as a globally-renowned alternative rock band. Their previous LP, 1987's poppy though melancholy Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me was a celebration of the band's first decade and helped The Cure crack mainstream America, the ultimate prize. Robert Smith, however, was not a happy puppy. Believing that most bands delivered their masterpiece by the time they were thirty, he set about writing "the most intense thing The Cure have ever done." In many ways, Disintegration was the prototype of a Robert Smith solo album. "I would have been quite happy to make those songs on my own, if that band hadn't liked them."

The atmosphere around him was particularly toxic. Smith was in a depressed, non-communicative state ("one of my non-talking modes"), as he fretted over creating an LP that contained the doom-laden gravitas of 1982's brilliant Pornography. "I actually wanted an environment that was unpleasant," he recalled, and a combination of his own truculence and keyboard player Lol Tolhurst's raging alcoholism ensured that the creation of Disintegration was a miserable experience.

The atmosphere around him was particularly toxic. Smith was in a depressed, non-communicative state ("one of my non-talking modes"), as he fretted over creating an LP that contained the doom-laden gravitas of 1982's brilliant Pornography. "I actually wanted an environment that was unpleasant," he recalled, and a combination of his own truculence and keyboard player Lol Tolhurst's raging alcoholism ensured that the creation of Disintegration was a miserable experience. While The Cure's American record label (Elektra) hated Disintegration on first listen ("There was just this look of absolute dismay on their faces," Smith confirmed), the album was a worldwide hit. Selling in excess of 3 million copies, Disintegration ensured that despite Smith's best efforts The Cure had "become everything I didn't want us to become - a stadium rock band." And a miserable stadium rock band at that. Chris Roberts' glowing Melody Maker review offered up a perplexing conundrum: "How can a group this disturbing and depressing be so popular?" Simple really; there's a dark side in all of us (had Star Wars taught Roberts nothing?), a part of us that relishes the underbelly of our psyche, the part of us that likes the room when its dark, a part that savors the monsters.

My mother was a back-up singer for the likes of Burt Bacharach and Ray Conniff, and so music was a constant in our lives. I recall having an 8-track player in our Ford Falcon and my mother playing only one side of People by Barbra Streisand. The title song was on Side 4 with "Love is a Bore" and "Don't Like Goodbyes" (an unusual Harold Arlen song with lyrics by Truman Capote). My mother would skip 1-3 and we'd listen to Side 4 over and over, just so that she could sing "People." It wasn't long afterwards that she got a new old car with a cassette, and she'd play "People" and rewind and say, "Listen to this part." It was when I realized the power of rewind; it was when I realized that little bits of songs, snippets of melody or vocals, could have such an impact. Since then I've listened to music that way: rewinding.

Disintegration is that album on which every rewind reveals something new, something dark or something unexpected about People.

Published on May 26, 2018 05:28

May 25, 2018

Boys Don't Cry

Los Angeles, 1980. The scene: An apartment building by the Tar Pits; 2B, in the back, over the garage; three girls down the hall, Kenya, Cathy, Laura the runaway. There were Johnnie's across the street and an IHOP with a big blue roof next door; the constant odor of breakfast and hairspray. No one was doing what we were; our hair wild, our clothes, fashionably off-kilter and slept in, decadently-preppy in plaid wool trousers and loafers, badges and suspenders; punky without the edge. Closer was out and the Pretenders' debut, Peter Gabriel's third eponymous LP (Melt), and The Feelies' Crazy Rhythms - it wasn't new wave, yet, but soon, very soon, everyone would be coming on Eileen (Come on, Eileen).

Melrose Avenue - In There Somewhere

Melrose Avenue - In There Somewhere

Kenya was the granddaughter of newsman Walter Winchell, her father a game warden in Africa (today she's a marijuana advocate/filmmaker); Cathy was just rich, a disheveled Marilyn Monroe; Laura, 16, was hotter than a 16-year-old should be, and lost. For a moment we dressed like Lost Boys, like pirates and swashbucklers (Adam and the Ants), but when the costumes came off, it was all about The Cure.

Where the UK debut, Three Imaginary Boys, consisted of discontented, disconnected, punky pop only hinting at the band's talents, Boys Don't Cry (AM8; the American release) was uniformly sublime, the perfect punk-lite LP. This compilation of singles, B-Sides and the standout tracks from 3IB is the debut The Cure should have released (and it was marketed as such in the U.S). The tracks culled from 3IB are presented in a better light when nestled alongside tracks like their first hit single "Boys Don’t Cry" (AM10), the up-tempo "Jumping Someone Else's Train," and their debut 7", the existentialist pop masterpiece, "Killing An Arab." Additional gems are the B-side "Plastic Passion" and the brilliant "World War," the basic track of which the band would reinvent 5 years later as "Shake Dog Shake," (not on the reissued CD).

But 1980 was singularly about "Boys Don't Cry." With best friend, Robbie Freed, the five of us called ourselves the DepKids (it was all about the hair product); we didn't play any instruments, couldn't write, had no drive, but we called ourselves a band (all you needed was a name). We took the girls up to a cabin in Big Bear and Laura kept playing "Boys Don't Cry." She played it over and over again. Robbie would eject the tape to play Dirk Wears White Sox or "Atrocity Exhibit," and she'd reach over and punch it back out - then the tape got caught on the capstan. We had to stop in a record store in Pasadena to get her another.

But 1980 was singularly about "Boys Don't Cry." With best friend, Robbie Freed, the five of us called ourselves the DepKids (it was all about the hair product); we didn't play any instruments, couldn't write, had no drive, but we called ourselves a band (all you needed was a name). We took the girls up to a cabin in Big Bear and Laura kept playing "Boys Don't Cry." She played it over and over again. Robbie would eject the tape to play Dirk Wears White Sox or "Atrocity Exhibit," and she'd reach over and punch it back out - then the tape got caught on the capstan. We had to stop in a record store in Pasadena to get her another.

To this day, I can listen to it over and over. The early Cure were not the band that I worshiped later in the decade (I ponder, then usually back away, not willing to be so bold, whether Disintegration (AM10) is the greatest album of all time, The Cure's raison d'être; with "Plainsong" being the hands down best opening track on any LP), but "Boys Don't Cry" is the most important single of the 80s, bar "Blue Monday," and the one track that can transport me effortlessly into my youth.

Melrose Avenue - In There Somewhere

Melrose Avenue - In There SomewhereKenya was the granddaughter of newsman Walter Winchell, her father a game warden in Africa (today she's a marijuana advocate/filmmaker); Cathy was just rich, a disheveled Marilyn Monroe; Laura, 16, was hotter than a 16-year-old should be, and lost. For a moment we dressed like Lost Boys, like pirates and swashbucklers (Adam and the Ants), but when the costumes came off, it was all about The Cure.

Where the UK debut, Three Imaginary Boys, consisted of discontented, disconnected, punky pop only hinting at the band's talents, Boys Don't Cry (AM8; the American release) was uniformly sublime, the perfect punk-lite LP. This compilation of singles, B-Sides and the standout tracks from 3IB is the debut The Cure should have released (and it was marketed as such in the U.S). The tracks culled from 3IB are presented in a better light when nestled alongside tracks like their first hit single "Boys Don’t Cry" (AM10), the up-tempo "Jumping Someone Else's Train," and their debut 7", the existentialist pop masterpiece, "Killing An Arab." Additional gems are the B-side "Plastic Passion" and the brilliant "World War," the basic track of which the band would reinvent 5 years later as "Shake Dog Shake," (not on the reissued CD).

But 1980 was singularly about "Boys Don't Cry." With best friend, Robbie Freed, the five of us called ourselves the DepKids (it was all about the hair product); we didn't play any instruments, couldn't write, had no drive, but we called ourselves a band (all you needed was a name). We took the girls up to a cabin in Big Bear and Laura kept playing "Boys Don't Cry." She played it over and over again. Robbie would eject the tape to play Dirk Wears White Sox or "Atrocity Exhibit," and she'd reach over and punch it back out - then the tape got caught on the capstan. We had to stop in a record store in Pasadena to get her another.

But 1980 was singularly about "Boys Don't Cry." With best friend, Robbie Freed, the five of us called ourselves the DepKids (it was all about the hair product); we didn't play any instruments, couldn't write, had no drive, but we called ourselves a band (all you needed was a name). We took the girls up to a cabin in Big Bear and Laura kept playing "Boys Don't Cry." She played it over and over again. Robbie would eject the tape to play Dirk Wears White Sox or "Atrocity Exhibit," and she'd reach over and punch it back out - then the tape got caught on the capstan. We had to stop in a record store in Pasadena to get her another.To this day, I can listen to it over and over. The early Cure were not the band that I worshiped later in the decade (I ponder, then usually back away, not willing to be so bold, whether Disintegration (AM10) is the greatest album of all time, The Cure's raison d'être; with "Plainsong" being the hands down best opening track on any LP), but "Boys Don't Cry" is the most important single of the 80s, bar "Blue Monday," and the one track that can transport me effortlessly into my youth.

Published on May 25, 2018 03:57

May 24, 2018

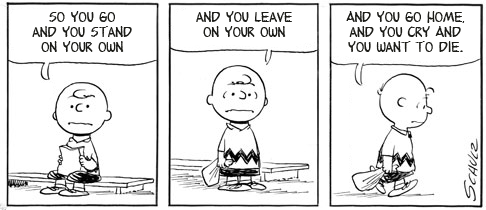

This Charming Charlie - The Philosophy of The Smiths

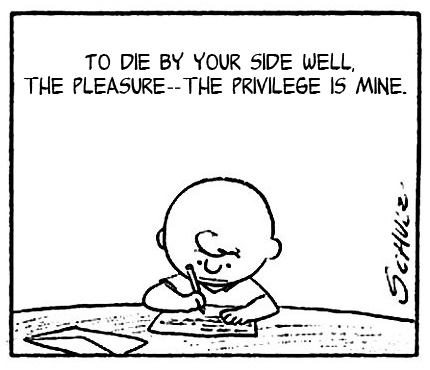

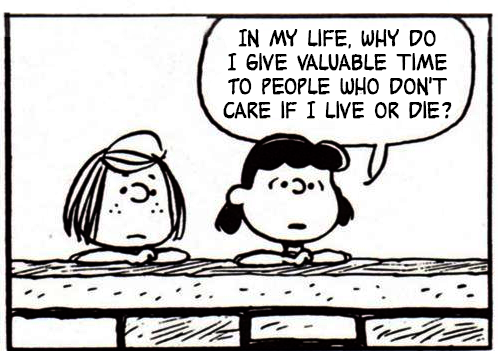

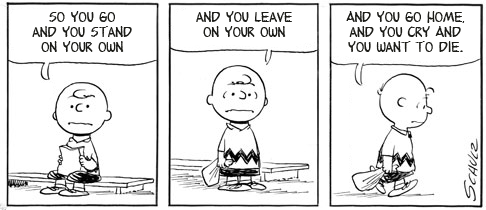

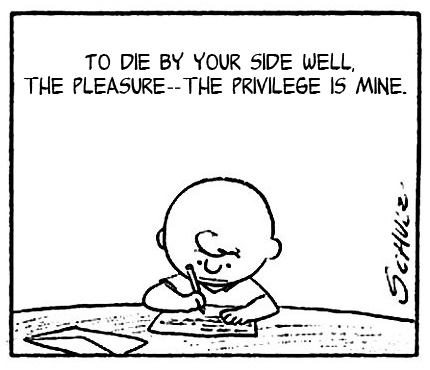

Still hanging philosophical, here's more proof The Smiths were genius. The following Charles Schultz Peanuts comics were reinvented by Loren LoPrete for her Tumblr, This Charming Charlie, incorporating Charlie Brown and The Smiths. I do not have any rights to these panels, but hopefully, AM can bring a little extra light to their poignancy.

Published on May 24, 2018 05:21

This Charming Man

Cranky Steven Patrick Morrissey was most comfortable in his childhood bedroom, firing off vitriolic missives to music magazines. Awkward and sexually ambiguous, he seemed neither frontman nor poster boy. Yet one day in 1982, Johnny Marr knocked on his door on a hunch that the 23-year-old misfit might become "this charming man." The partnership that ensued led to the most important music of the decade (if not the most influential). Marr was, alongside Robert Smith of The Cure, the most inventive guitarist of his generation, whether providing the jangle to "This Charming Man" the siren squall to "How Soon Is Now?" the cinematic scope of "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me," or the delicate solo to "Shoplifters of the World Unite." And Morrissey’s lyrics followed in the tradition of Oscar Wilde and Rimbaud — lovelorn, yes, but funny, literate, smart, alive.

Cranky Steven Patrick Morrissey was most comfortable in his childhood bedroom, firing off vitriolic missives to music magazines. Awkward and sexually ambiguous, he seemed neither frontman nor poster boy. Yet one day in 1982, Johnny Marr knocked on his door on a hunch that the 23-year-old misfit might become "this charming man." The partnership that ensued led to the most important music of the decade (if not the most influential). Marr was, alongside Robert Smith of The Cure, the most inventive guitarist of his generation, whether providing the jangle to "This Charming Man" the siren squall to "How Soon Is Now?" the cinematic scope of "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me," or the delicate solo to "Shoplifters of the World Unite." And Morrissey’s lyrics followed in the tradition of Oscar Wilde and Rimbaud — lovelorn, yes, but funny, literate, smart, alive. Tony Fletcher in his bio A Light That Never Goes Out says, "Those my own age, most of us parents now, some even with angst-ridden teenagers of our own, mostly greet a mention of the Smiths as if I was speaking of a former lover. I imagine they're the soundtrack for as many lovelorn teens now as they were back in the 1980s. They're cherished in a way that it's hard to cherish the Beatles or the Rolling Stones. Their songs might have charted higher and sold more, but they never had a 'How Soon Is Now?' with a line like 'I am human and I need to be loved/ Just like everybody else does.' The Smiths knitted together the people who knew them and loved them. "I think he was just waiting for the right person to knock on his door," Marr said of their first encounter. Morrissey was essentially 'discovered' by an 18-year-old kid, and lo and behold off they went to become the greatest partnership since Lennon/McCartney. And yet Marr had to pass a test: Morrissey had a huge collection of singles. He asked Johnny to play a song. Marr found a rare single by the Marvelettes, put on the B-side, "You're the One," and sang along to every word. A+, indeed, the right choice.

Tony Fletcher in his bio A Light That Never Goes Out says, "Those my own age, most of us parents now, some even with angst-ridden teenagers of our own, mostly greet a mention of the Smiths as if I was speaking of a former lover. I imagine they're the soundtrack for as many lovelorn teens now as they were back in the 1980s. They're cherished in a way that it's hard to cherish the Beatles or the Rolling Stones. Their songs might have charted higher and sold more, but they never had a 'How Soon Is Now?' with a line like 'I am human and I need to be loved/ Just like everybody else does.' The Smiths knitted together the people who knew them and loved them. "I think he was just waiting for the right person to knock on his door," Marr said of their first encounter. Morrissey was essentially 'discovered' by an 18-year-old kid, and lo and behold off they went to become the greatest partnership since Lennon/McCartney. And yet Marr had to pass a test: Morrissey had a huge collection of singles. He asked Johnny to play a song. Marr found a rare single by the Marvelettes, put on the B-side, "You're the One," and sang along to every word. A+, indeed, the right choice. Got Milk?Like REM from the same era, The Smiths' canon was chock full of poetry, poly-syllabic words (in Morrissey’' case you could understand them – Stipe is a different story), and intermittent moans and groans. The Smiths made you (make you) feel smarter, less pathetically alone, and more sexually excited than any band of any era. Marr's ability to make musical poetry worthy of Morrissey's twisted, elevated, and self-obsessed lyrics is irresistible.

Got Milk?Like REM from the same era, The Smiths' canon was chock full of poetry, poly-syllabic words (in Morrissey’' case you could understand them – Stipe is a different story), and intermittent moans and groans. The Smiths made you (make you) feel smarter, less pathetically alone, and more sexually excited than any band of any era. Marr's ability to make musical poetry worthy of Morrissey's twisted, elevated, and self-obsessed lyrics is irresistible.It's been 30 odd now since the first LP, yet it remains fresh and honest, sincere and overwhelming, just like yesterday. The best tracks:

"This Charming Man" - The Smiths' effortlessly catchy second single finds Morrissey getting a tempting proposition from an older, suave and "charming man" in a fancy car with smooth leather seats. There's a simultaneous sense of decadence and elegance. More so than any other riff on the album, Marr's glistening guitar-work encourages the listener to get up and dance, with Rourke's walking bass line injecting an even deeper groove.

"This Charming Man" - The Smiths' effortlessly catchy second single finds Morrissey getting a tempting proposition from an older, suave and "charming man" in a fancy car with smooth leather seats. There's a simultaneous sense of decadence and elegance. More so than any other riff on the album, Marr's glistening guitar-work encourages the listener to get up and dance, with Rourke's walking bass line injecting an even deeper groove."Hand in Glove" - The band's first single is still a truly beautiful song. Marr and Rourke weave their instruments in and out to create an ominous new wave soundscape, while Morrissey gives a dire vocal performance that's classic Smiths. He sings words of devotion, almost sure he's found love, but has that nagging feeling he'll soon lose it. The piercing wail of harmonica adds the perfect amount of torture to the mix.

"What Difference Does It Make?" - As the album's most direct "rock song" kicks into gear, it's clear that side B has outdone "The Smiths'" A side. With its prominent new wave guitars and strong hooks, this single is less challenging than much of the album's other cuts (perhaps that's why both Morrissey and Marr have since criticized it), though it's still one of the Smiths' most enduring songs. Morrissey's wailing falsetto in the outro remains deeply glamorous.

Published on May 24, 2018 05:21

May 23, 2018

The Privilege is Mine - 1987

Take me out tonight/ Where there's music and there's people/ Who are young and alive./ Driving in your car/ I never, never want to go home...

Take me out tonight/ Where there's music and there's people/ Who are young and alive./ Driving in your car/ I never, never want to go home...The start of the academic year, UCLA, my first semester living on campus; a crazy cute blonde sk8r, 2nd year, rich as all hell, pursuing me. (Fuck, yeah, but why?) Comes round my dorm to give me the Smiths' The Queen Is Dead, and my subsequent devotion is perfunctorily timeless, ageless, doting. As she plays "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out" and says how it reminds her of me, resistance is futile; it is the ultimate song of romance. We listen to the album and the song over and over, wrapped in each other's arms – the sublimity of our relationship: long lunches on the lawns ("I don't have to go to class, do you?"), evenings in my room, nights in Hollywood - Lhasa, Lingerie, Seven Seas, Ben Franks all hours. Inspired by Meat is Murder we venture into vegetarianism, but can't, burgers, after all, chili dogs.

Sorrowfully, the relationship doesn't last. Having secured my affections, her interest wanes, she loses respect. Took me home to Malibu. Swam out so far, couldn't touch bottom (not a strong swimmer), tangled in the kelp forest, laughs - at me; start of the end. Puts me down, pushing changes, noting imperfections: my clothing all wrong; my face too spotty; my laugh too loud. I am possessive and fear others.

I arrange to meet her at Ship's, to tell her it isn't working (always be the one to break it off - have I tried this before?). Foolishly I weaken ("I love you"). Two days hence, she dumps me. I am devastated, withdrawn, for shit. I send her notes, leave her messages, buy her things. Make a mixed tape - the songs we listened to - Heaven 17, New Order, Siouxsie. Two weeks later, I find out that she borrowed The Queen Is Dead from a girl down the hall and never gave it back. "This is mine" (girl down the hall). "Don't care. Keeping it." ("Asshole.") Still have it.

Called her. Message on machine. "'I know it's over.'"

If a double-decker bus

Crashes in to us,

To die by your side

Is such a heavenly way to die...

Published on May 23, 2018 04:17

The Queen is Dead and Other Fictions

The Smiths colored both inside and out of the lines. Johnny Marr's view of the world was shaped by the Stones and the Beatles, by the Beach Boys; that's pretty neat coloring there, but Morrissey added the literary and the offbeat; he was Oscar Wilde and Dorothy Parker and included an inexhaustible array of opinions and lifestyle choices that offered a radical break with Margaret Thatcher's (and Ronald Reagan's) 80s. He sings of love, knowing he'll lose it once again, or it will lose him. There is always a degree of torture added into the mix, a certain idealized hope and immediate frustration, a scribbling outside the lines.

The Smiths colored both inside and out of the lines. Johnny Marr's view of the world was shaped by the Stones and the Beatles, by the Beach Boys; that's pretty neat coloring there, but Morrissey added the literary and the offbeat; he was Oscar Wilde and Dorothy Parker and included an inexhaustible array of opinions and lifestyle choices that offered a radical break with Margaret Thatcher's (and Ronald Reagan's) 80s. He sings of love, knowing he'll lose it once again, or it will lose him. There is always a degree of torture added into the mix, a certain idealized hope and immediate frustration, a scribbling outside the lines.For a band that released only four full-length (real) albums, the Smiths’ catalog is a nightmare to untangle. In Britain, they were immediate and justifiable stars, with hits like "Hand in Glove" and "Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now," but in the States, it was holey pockets of devotees, 80s hipsters growing out of Depeche Mode and Haicut 100. While the inarguable manner in which the Smiths' music has aged over time has burnished their rep beyond dispute, it is not difficult to comprehend how alienating they were to American audiences. Even as ostensibly progressive bands like R.E.M. flourished on commercial radio, Americans weren't prepared to reckon with Morrissey's challenge: a dyed-in-the-wool rock star who never on any level referenced his adoration for the girls. George Michael did; so did Elton John. Even Boy George was easier to accept because he was a simple caricature, but Morrissey was something different altogether: icy, acid of wit, foreign in nearly every regard, and a man.

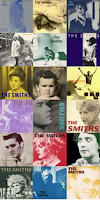

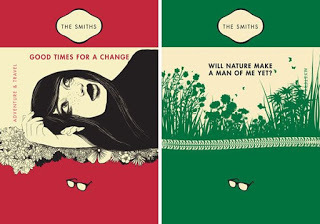

The Smiths can be easily defined, but create a rubric of their own, once again coloring outside the context of the lines, flipping off AM: Distinct Atmosphere and Era: The Smiths are an 80s band, a pissed off one, and yet still there was time for art and beauty, a time to wake up and smell the bus fumes. That sense of era is promulgated by Morrissey's album cover choices, a love a 60s actors and a general hollow feel, a whole hatful. Powerful Storytelling: So many of their songs derive their impact with the skilled simplicity with which the lyrics construct everything. Intrigue: The best Smithsongs create a brilliant counter-intuitive effect of being complex and simple, plain and fancy. There is clarity here. Some girls really are bigger than others. Humanity: The Smiths are penultimate to nothing in terms of staunch, raw feelings.

The Smiths can be easily defined, but create a rubric of their own, once again coloring outside the context of the lines, flipping off AM: Distinct Atmosphere and Era: The Smiths are an 80s band, a pissed off one, and yet still there was time for art and beauty, a time to wake up and smell the bus fumes. That sense of era is promulgated by Morrissey's album cover choices, a love a 60s actors and a general hollow feel, a whole hatful. Powerful Storytelling: So many of their songs derive their impact with the skilled simplicity with which the lyrics construct everything. Intrigue: The best Smithsongs create a brilliant counter-intuitive effect of being complex and simple, plain and fancy. There is clarity here. Some girls really are bigger than others. Humanity: The Smiths are penultimate to nothing in terms of staunch, raw feelings. The best of the albums is The Queen is Dead (AM10), but The Smiths and Meat is Murder are pure AM8s, and Strangeways Here We Come is undeniably an AM7. It's interesting that Rough Trade played so willy-nilly with the studio albums and the abundance of compilations. It's hard not to rate an album like Hatful of Hollow, another clear AM10 were it an album. Indeed if we as listeners were given the same liberties (and today we'd just make a playlist/mix tape), there'd be a struggle not to slap on an AM11. That in mind, here's mine; I call it 20 years, 7 months, and 27 days (AM11):

1. Hand in Glove 7. There is a Light That Never Goes Out

2. Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now 8. Girlfriend in a Coma

3. William, It Was Really Nothing 9. Back to the Old House

4. How Soon is Now 10. The Queen is Dead

5. The Boy With Thorn is His Side 11. This Charming Man

6. Big Mouth Strikes Again 12. Please, Please, Please

Published on May 23, 2018 04:17

May 22, 2018

The Smiths - The Hollywood Palladium - 1985

Of course there isn't complete disregard of historic venues; while many, like the Fillmore, live on, in spirit or tribute, many have been recognized for their cultural significance, others have just been lucky. The best example in L.A., more so even than The Whiskey or The Troubadour (their significance in rock history unparalleled), is The Hollywood Palladium. The Palladium building is a cornerstone example of L.A. art deco architecture. It was designed by Gordon Kaufmann, the legendary architect who also did the L.A. Times building downtown, the Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills and, most famously, Hoover Dam. The venue opened in 1940 and traces its history from the big band era through the filming of The Lawrence Welk Show in the 60s and on to decades of pop music concerts. From the 70s through the teens, the venue has hosted landmark performances by everyone from The Rolling Stones to Chuck Berry, The Smiths to Jay Z. In 2008, the venue was closed temporarily for renovations, and the front marquee and main "blade" signage were restored. In my youth, Hollywood was indeed a land of dreams – movie palaces and C.C. Brown's, Pig and Whistle and Musso and Frank's; the Walk of Stars. Growing up instead, Hollywood Blvd. was hustlers and drugs, Hari krishnas and Scientologists. While the Seven Seas was my haunt, Hollywood was haggard and dangerous. It's nice to know that glamour has returned, that the Chinese and the Egyptian and the Cinerama Dome are safe, but unlike Times Square, there’s still a grit to it, a seedy Tom Waits feel.

Of course there isn't complete disregard of historic venues; while many, like the Fillmore, live on, in spirit or tribute, many have been recognized for their cultural significance, others have just been lucky. The best example in L.A., more so even than The Whiskey or The Troubadour (their significance in rock history unparalleled), is The Hollywood Palladium. The Palladium building is a cornerstone example of L.A. art deco architecture. It was designed by Gordon Kaufmann, the legendary architect who also did the L.A. Times building downtown, the Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills and, most famously, Hoover Dam. The venue opened in 1940 and traces its history from the big band era through the filming of The Lawrence Welk Show in the 60s and on to decades of pop music concerts. From the 70s through the teens, the venue has hosted landmark performances by everyone from The Rolling Stones to Chuck Berry, The Smiths to Jay Z. In 2008, the venue was closed temporarily for renovations, and the front marquee and main "blade" signage were restored. In my youth, Hollywood was indeed a land of dreams – movie palaces and C.C. Brown's, Pig and Whistle and Musso and Frank's; the Walk of Stars. Growing up instead, Hollywood Blvd. was hustlers and drugs, Hari krishnas and Scientologists. While the Seven Seas was my haunt, Hollywood was haggard and dangerous. It's nice to know that glamour has returned, that the Chinese and the Egyptian and the Cinerama Dome are safe, but unlike Times Square, there’s still a grit to it, a seedy Tom Waits feel. For me, The Hollywood Palladium fit right into my new wave sensibility. I could easily see the evolution from Sinatra to Morrissey, from Zappa to Talking Heads.

For me, The Hollywood Palladium fit right into my new wave sensibility. I could easily see the evolution from Sinatra to Morrissey, from Zappa to Talking Heads. A Ho-Hum Interlude: While I regret the loss of what once was, from The New Florentine Gardens to Madame Wong's, I guess purgatory is worse. Just a brief history of what I still refer to as The Aquarius Theater. Opened in its art deco setting in the 1930, The Errol Carroll Theater was one of golden Hollywood's icons, like the sign and The Magic Castle. The theater's slogan is a gem of a by-gone era: "Through these portals pass the most beautiful girls in the world." The signage out front was a 39 foot neon of one of those beautiful girls, Beryl Wallace. When Errol Carroll died in 1948, the club became the even more famous Hollywood Moulin Rouge. By the 60's the club became the ABC studio for Hullaballoo, a teen dance program, before it was transformed into The Aquarius Theater for the musical Hair. The Doors played their most famous shows at the Aquarius (and also under its former banner The Kaleidoscope, which only lasted for a few months). The theater would have bursts of energy throughout the 80s, but, and here's where ho-hum begins, it was transformed in Nickelodeon's L.A. studios in the mid 90s. Today Nickelodeon has all but abandoned the property and the famous building's fate remains unknown.

Back to the good part: The Smiths played the Palladium in 1985. While the L.A. Times didn't appreciate the show, stating, "For someone who preaches an intense relationship between artist and audience, Morrissey was pretty remote," they still acknowledged the intensity of the band: "The Smiths are trying to be more than just a rock band. Under the leadership of the fragile flower known as Morrissey, the English group has taken on the air of a crusade, waving the banner of musical simplicity, naked emotion and fierce independence.

"Rejecting punk's rage but embracing its rebellious idealism, replacing the image-making and show-biz manipulation of kindred acts like Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Boy George with a cultivated innocence, the Manchester quartet has built a following of fans seeking something that the cold synthesizer bands aren't providing: human contact."

"Rejecting punk's rage but embracing its rebellious idealism, replacing the image-making and show-biz manipulation of kindred acts like Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Boy George with a cultivated innocence, the Manchester quartet has built a following of fans seeking something that the cold synthesizer bands aren't providing: human contact."Despite the so-so review, this writer, meaning me, only remembers an atmosphere that must have resembled that of the crowd surrounding St. John the Baptist; spectators, like me, emotionally drained and yet somehow fulfilled.

How could it possibly be, then, that Morrissey's ten day stint at The Palladium twenty-two years later was that much more transplendent (is that a word, or just something I heard in Annie Hall?). I found it impossible to take my eyes from him, and as a displaced Angeleno living outside Philadelphia today, I could feel how much of an L.A. vibe Morrissey exuded. Songs like "How Soon Is Now" and "Stretch Out and Wait" had me ugly crying. Ten years later, I have my Morrissey tickets in hand for his show at The Philadelphia Fillmore. Guess I better bring tissues.

Published on May 22, 2018 04:21

Smiths

Morrissey

Morrissey

Terrence StampThe Smiths, as a rule, Morrissey in particular, dressed in ordinary street clothes, contrasting the exotic high-fashion imagery cultivated by New Romantic bands like Spandau Ballet and Duran Duran, or the costumey showmanship of Adam and the Ants. In 1986, when The Smiths performed on the British program The Old Grey Whistle Test, Morrissey wore a hearing aid to support a hearing-impaired fan ashamed of using one. He frequently sported thick-rimmed National Health Service glasses, not unlike Buddy Holly's.

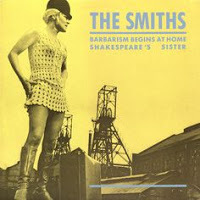

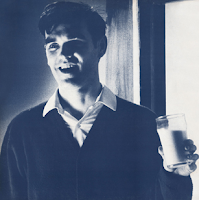

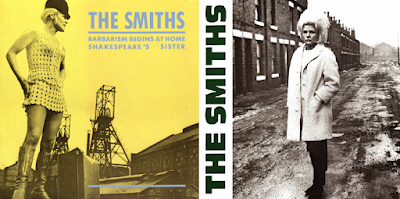

Terrence StampThe Smiths, as a rule, Morrissey in particular, dressed in ordinary street clothes, contrasting the exotic high-fashion imagery cultivated by New Romantic bands like Spandau Ballet and Duran Duran, or the costumey showmanship of Adam and the Ants. In 1986, when The Smiths performed on the British program The Old Grey Whistle Test, Morrissey wore a hearing aid to support a hearing-impaired fan ashamed of using one. He frequently sported thick-rimmed National Health Service glasses, not unlike Buddy Holly's. With this simplicity of character in mind, Morrissey designed the Smiths' album and single covers with Jo Slee of Rough Trade, utilizing a simple aesthetic: a duotone photo of a vintage pop star, cult hero or actor, tinted with a contrasting color for text in a sans-serif laden font. (Belle and Sebastien followed suit more recently with a similar format.) The band themselves did not appear on the outer cover of their UK releases. However, Morrissey appeared on the alternative cover shown for "What Difference Does It Make?," mimicking the pose of the original subject, actor Terence Stamp, holding a chloroform pad from the 1965 film The Collector, after the actor objected to the use of his image. Morrissey instead holds a glass of milk.

From Warhol's FleshThe cover stars were an indication of Morrissey's personal interests in obscure or cult film stars, including Stamp, Alain Delon, Jean Marais, Warhol protégé Joe Dallesandro and James Dean, as well as figures from 1960s British and American culture, including Coronation Street actress Viv Nicholson, playwright Shelagh Delaney and Truman Capote.

From Warhol's FleshThe cover stars were an indication of Morrissey's personal interests in obscure or cult film stars, including Stamp, Alain Delon, Jean Marais, Warhol protégé Joe Dallesandro and James Dean, as well as figures from 1960s British and American culture, including Coronation Street actress Viv Nicholson, playwright Shelagh Delaney and Truman Capote.The sleeve for The Smiths' eponymous debut features American actor Joe Dallesandro in a cropped still from Andy Warhol's 1968 film Flesh. In the uncropped version, Dallesandro appears to be masturbating a male co-star. The Smith's second album, Meat is Murder, featured an edited still from Emile de Antonio's 1968 documentary In the Year of the Pig. The legend on the soldier's helmet originally read "Make War Not Love," but Morrissey replaced it with his impassioned declaration of vegetarianism. The Queen Is Dead was the third studio album by The Smiths. The album cover features French actor, Alain Delon, from the 1964 film L'Insoumis.

Billie Whitelaw, 1967, Charlie BubblesThe sleeve for The Smith's final studio album, Strangeways, Here We Come, features a murky shot of James Dean’s East of Eden co-star Richard Davalos. Davalos is looking at James Dean, who is cropped from the image. Dean was a hero of Morrissey's, about whom the singer wrote a book called James Dean Is Not Dead. Morrissey had intended to use a still of Harvey Keitel in Martin Scorsese's I Call First, but Keitel declined to allow him use of the image. In 1991 Keitel relented, and the image was used on t-shirts and stage backdrops for Morrissey's 1991 solo tour.

Billie Whitelaw, 1967, Charlie BubblesThe sleeve for The Smith's final studio album, Strangeways, Here We Come, features a murky shot of James Dean’s East of Eden co-star Richard Davalos. Davalos is looking at James Dean, who is cropped from the image. Dean was a hero of Morrissey's, about whom the singer wrote a book called James Dean Is Not Dead. Morrissey had intended to use a still of Harvey Keitel in Martin Scorsese's I Call First, but Keitel declined to allow him use of the image. In 1991 Keitel relented, and the image was used on t-shirts and stage backdrops for Morrissey's 1991 solo tour. Louder Than Bombs was a compilation released as a double album in March 1987 by The Smiths' American distributor, Sire Records. The sleeve features British playwright Shelagh Delaney. The photograph was originally published in the Saturday Evening Post after Delaney, at the age of 19, had made a striking literary debut with her play A Taste of Honey. The play inspired many early lyrics written by Morrissey, particularly the song "This Night Has Opened My Eyes."

Viv Nicholson - "Spend, Spend, Spend"

Viv Nicholson - "Spend, Spend, Spend"

Published on May 22, 2018 04:18