R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 73

May 14, 2018

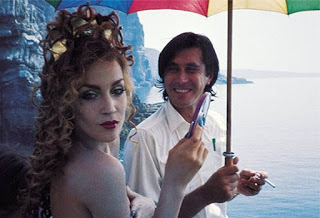

Wish Everybody Would Leave Me Alone - Stranded - Roxy Music

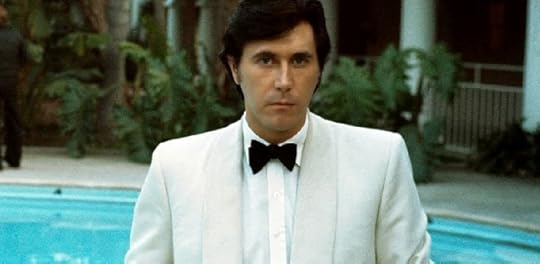

Bryan Ferry: For me, 1973 was an exceptionally busy year. Looking back, it seems like a whirlwind of events. For Your Pleasure was quickly followed by my first solo album, These Foolish Things. For Your Pleasure was a dark and important album for me to make, and These Foolish Things was much lighter, and cleared the air of all that angst. It was a great success and suddenly I was on tour. I can't quite remember how many live shows we did in '73, both solo and as Roxy, but I do have a hazy memory of rushing into the Royal Albert Hall with a very under-rehearsed band and it all going surprisingly well.

Bryan Ferry: For me, 1973 was an exceptionally busy year. Looking back, it seems like a whirlwind of events. For Your Pleasure was quickly followed by my first solo album, These Foolish Things. For Your Pleasure was a dark and important album for me to make, and These Foolish Things was much lighter, and cleared the air of all that angst. It was a great success and suddenly I was on tour. I can't quite remember how many live shows we did in '73, both solo and as Roxy, but I do have a hazy memory of rushing into the Royal Albert Hall with a very under-rehearsed band and it all going surprisingly well. Phil Manzanera: It was a very creative, prolific time. Our management would be booking the next Roxy tour while we were still making the album, and if the album wasn't finished, we’d have to go back to the studio after the gig, do a bit more, then go off to the next gig. We were really energized and firing on all cylinders.

Paul Thompson: It seemed normal to us. Albums didn't take long back then. We cut them in a couple of weeks. These days it would be a couple of years.

Andy Mackay: It wasn't the happiest time in Roxy’s history. There was something of a battle going on between Bryan and everyone else. Bryan's solo success was threatening to blur the line between Roxy and him. Bryan definitely felt that Roxy was his band and he could push it in the directions he wanted. He didn't realize that your best work tends to come from a bit of struggle, rather than having things all your own way.

Andy Mackay: It wasn't the happiest time in Roxy’s history. There was something of a battle going on between Bryan and everyone else. Bryan's solo success was threatening to blur the line between Roxy and him. Bryan definitely felt that Roxy was his band and he could push it in the directions he wanted. He didn't realize that your best work tends to come from a bit of struggle, rather than having things all your own way.Bryan Ferry: I was on a bit of a roll, so I started planning, writing and recording the next Roxy album, Stranded.

Andy Mackay: There was a degree of plotting going on. Even now, I don't know exactly how much. There's a famous occasion when we were playing a gig in York, and Bryan, without telling anyone, invited Eddie Jobson to come and watch. That was Eno’s last performance with us. It all seemed slightly underhand. Eno had been my friend before I met Bryan, and I was concerned about what might happen if he left. I considered leaving as well. I was going to join Mott The Hoople.

Phil Manzanera: I guess everybody thought the band was over. I was upset that Eno had to go. But things had been getting a bit dodgy on the European tour, and the band obviously wasn’t big enough for two Brians. Stranded moved us into different territory. The one thing we always knew was that Roxy had to keep changing. It would be like, "Right, everyone else is doing glam? OK, we'll start wearing suits." Of course, it did confuse our fans, because they'd turn up with the old look at the start of each tour. But after three or four gigs, they'd cotton on and you'd see them change.

Bryan Ferry: I often wonder how I could have produced so much work in 1973. I can only assume that I'm one of those people who thrives on approval, and the instant success of the first Roxy Music album in 1972 had been a great shot in the arm for me. Since the age of 10 I had loved music so much, and had absorbed so many influences from so many genres, that I was bursting with ideas, and now I felt I had an audience who was willing to listen to them.

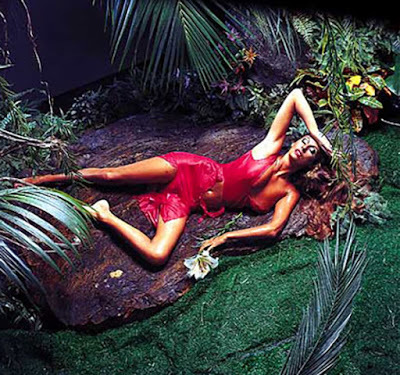

Bryan Ferry: I often wonder how I could have produced so much work in 1973. I can only assume that I'm one of those people who thrives on approval, and the instant success of the first Roxy Music album in 1972 had been a great shot in the arm for me. Since the age of 10 I had loved music so much, and had absorbed so many influences from so many genres, that I was bursting with ideas, and now I felt I had an audience who was willing to listen to them.Stranded: This is the coolest overall album from Bryan Ferry's once-crazy-enough-to-be-hip band: something quite different from the post-Siren records, which are often soft and friendly enough to listen with your grandmother. The mood on Stranded isn't as downer-hallucinatory as on the all-time-sexiest-rock-album contender Country Life, (Avalon, though it wants to be, is far less cool than Stranded, and cool is more important in my book! - which of course, is Jay and the Americans, available at Amazon by clicking the graphic to your right) but in a much more funky, upbeat-hallucinatory, hyperactive, almost Sly Stonish 'rocking out' mode. "Street Life," "Amazona" and "Mother of Pearl," are among my all-time favorite Roxy tunes, loud enough to be rock 'n' roll, funky, yet driven by distorted guitars, musically sophisticated though not pretentious. And of course Roxy's ultimate tune, "A Song for Europe," hovers over ruckus with quiet abandon.

To anyone new to Roxy's early period, I'd suggest Stranded first, then Country Life or For Your Pleasure, rather than Siren, or the bursting-with-ideas but sloppy debut record. It's these three that represent the best the early band had to offer, whereas Siren is a polished, less immediately real attempt at reaching a larger U.S. audience. The 'post-punk' period after Manifesto, (and Roxy Music, being a creation that implied some sort of connection with glitz and glamour, were one of the bands most hated by Punk Rockers even as they thoroughly influenced the entire post-Punk 'New Wave" movement) is actually a very different band, a refined, elegant, tuxedo-wearing, perfectionist sound.

Stranded is concrete evidence that Brian Eno's departure was by no means the death knell for Roxy. Eddie Jobson is a top notch musician, if not of Eno's caliber, who nonetheless put his own stamp on the band's sound, bringing the violin and his own brand of keyboard stylings into the mix. Eno himself touted Stranded as the band's masterpiece.

Stranded is concrete evidence that Brian Eno's departure was by no means the death knell for Roxy. Eddie Jobson is a top notch musician, if not of Eno's caliber, who nonetheless put his own stamp on the band's sound, bringing the violin and his own brand of keyboard stylings into the mix. Eno himself touted Stranded as the band's masterpiece.Given the trajectory of their later careers, it would be reasonable to assume that it was Eno rather than Ferry who sparked the immense creative drive that was early Roxy Music. But here Eno is gone, and Stranded is a blindingly good LP. Some of the restlessness in the songs is gone - no longer do you feel that two or three or ten separate ideas have been packed into each song, yet far from relaxing into formula, every track explores new musical ground. With "Mother of Pearl," Ferry spins an ode at once literate, glamorous and meaningless, in true aesthetic style: "Serpentine sleekness/ Was always my weakness/ Like a simple tune./ But no dilettante/ Filigree fancy/ Beats the plastic you." Still, the most surprising song here is the religious track "Psalm," a slow-moving rocker which builds inexorably to its supremely camp climax. Messianic themes are particularly germane to glam rock (Bowie was particularly aware of the way rock stars are worshiped like gods in Ziggy Stardust). But, in its apparent earnestness, "Psalm" summons up a sense of everything glam in Christianity itself - those kinky martyr stories, the opulence of the Catholic church, the rock-star pull of the charismatic preacher. Sumpin' eh?

Published on May 14, 2018 03:35

May 13, 2018

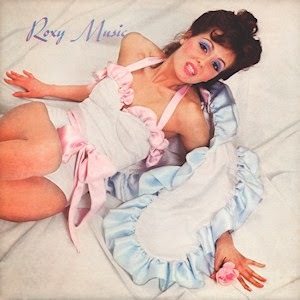

Roxy Music

Roxy Music

(AM7)

Roxy Music

(AM7)Artist: Roxy Music

Released: June 16, 1972

Produced by: Pete Sinfield

Tracks: 1) Remake/Remodel (5:10); 2) Ladytron (4:21); 3) If There is Something (6:33): 4)2HB (4:34); 5) The Bob (5:48); 6) Chance Meeting (3:00) 7) Would You Believe? (3:47); 8) Sea Breezes (7:00); 9) Bitters End (2:02)

Band Members: Bryan Ferry: Vocals, piano, mellotron; Brian Eno: Electronics, tape effects, backing vocals; Phil Manzanera: guitars; Andy Mackay: sax, oboe, backing vocals; Paul Thompson: drums; Graham Simpson: Bass (Rik Kenton, bass on "Virginia Plain;" not included on the original album - 45 only)

The first Roxy Music album must have seemed visionary in 1972; even today, it packs a mighty punch. The vibe is willfully eclectic mixing psychedelia, art-rock, rockabilly, 30s croonings and Velvets-inspired proto-punk. The band posited style as substance and in the process made their arty experimentation cool and glam. There are triple doses of camp and irony, but look for the serious hidden within. Another aspect of Roxy Music - and every Roxy Music effort until Siren - is that each band member shines, while no one hogs the spotlight. Among the great cache of hummable pop are "Remake/Remodel," "Ladytron," and of course, "Virginia Plain" (AM10), arguably the greatest pop song of the decade (while not on the album, the single was released simultaneously). The overall sound and production is quite rough and under-produced (particularly for Pete Sinfield), and by side two the concept drags, but Roxy Music is an essential addition to anyone's collection.

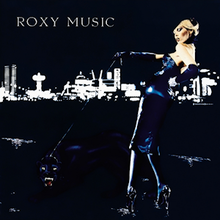

For Your Pleasure

(AM8)

For Your Pleasure

(AM8)Artist: Roxy Music

Released: March 23, 1973

Produced by: Chris Thomas, John Anthony, Roxy Music

Tracks: 1) Do the Strand (4:04); 2) Beauty Queen (4:41); 3) Strictly Confidential (3:48): 4) Editions of You (3:51); 5) In Every Dream Home, A Heartache (5:29); 6) The Bogus Man (9:20) 7) Grey Lagoons (4:13); 8) For Your Pleasure (6:51)

Band Members: Bryan Ferry: Vocals, piano, mellotron; Brian Eno: Electronics, tape effects, backing vocals; Phil Manzanera: guitars; Andy Mackay: sax, oboe, farfisa; Paul Thompson: drums

Roxy Music took a darker turn on their second album. If their debut painted a lounge singer lost in Limbo, For You Pleasure crosses the river Styx to the other side of unfulfilled desires, isolated souls crushed by the weight of emptiness between them, and sinners relegated to an eternity of cruel irony. At least that's the impression songs like "In Every Dream Home A Heartache," "The Bogus Man" and "For Your Pleasure" give. Half of the album is simply the next step of the revolutionary romance of their first LP, but it's not enough to shake the nightmarish pull created by the weightier epics. Serving two masters (love and art) makes for an uneasy musical alliance on For Your Pleasure, but it's a riveting tug of war.

The album begins with the fan favorite "Do The Strand." Deliciously fun and frollicking, dance rock anthem features rather psychotic vocals from Ferry, as well as excellent keyboard, guitar & sax work, but the highlights are indeed the drumming and the weird lyrics - "Wary of the waltz, mashed potato schmalz, rhododendren!". Slightly ridiculous, but that's what the band's all about.

One of Roxy Music's better "rock" moments, and up there with “Virginia Plain,” "Editions of You" is a great slice of mad Roxy art-pop. It lasts just under 4 minutes, but what an engaging 4 minutes they are: the instrumental solos leap from Andy Mackay's frantic sax, to Eno's positively berserk synth. Add to that some great guitar breaks from Manza, and some silly organ towards the end, and you have a sure fire winner! "Don't play yourself for a fool....too much cheesecake too soon!" Yes indeed.

"In Every Dream home a Heartache” is the premiere example of Art Decadent Sci-fi Rock. In essence, it's a poem where a rich rich rich man chortles on about how fantastic his inflatable doll is (certainly a celebration of the whole "money can't buy you happiness" maxim), set to some fluid synth-treated guitar; all very low-key until about 3 minutes in, when the guitar and synth are unleashed and play merry hell with one another, with Ferry chanting "Dream home heartache" as if someone's torturing him with a screwdriver. One of rock's stellar false endings, the song makes a fantastic return, again with the guitar and synth fighting for prominence. One of Roxy's greatest pieces of art rock - even if one only has a passing interest in the genre, treat yourself at least once!

Published on May 13, 2018 15:09

Art Pop

What was the single greatest year in rock history? As with most critical thought experiments, it's a question without an answer, but fun to argue about anyway. The way we respond to it probably says more about music's present than its past. Do we revisit the primordial ooze of 1951, when Ike Turner’s Kings of Rhythm recorded "Rocket 88," a contender for the first rock and roll song? What about 1956 or 1964, when Elvis’ and then the Beatles' Ed Sullivan performances heralded successive tidal waves of youth culture? Or '67, or '69, when hippie culture coalesced at Woodstock, a generation-defining event of the boomers' own making? And of course there are the definitive moments of the 70s; the one that may get fewer accolades than it deserves is 1971.

In his recent book Never a Dull Moment: 1971—The Year That Rock Exploded, British music critic David Hepworth argues that 1971 "saw the release of more influential albums than any year before or since." (Hepworth happened to be 21 at the time, which either kills his credibility or renders it unimpeachable.) Led Zeppelin IV, Joni Mitchell's Blue, Marvin Gaye's What's Going On, David Bowie's Hunky Dory, Carole King's Tapestry, Sly & the Family Stone's There’s a Riot Goin' On, Leonard Cohen's Songs of Love and Hate, and Black Sabbath's Master of Reality are only the beginning of the list.

Despite the fact that 1971 began with the legal dissolution of the Beatles, a moment Hepworth identifies as the end of the pop era and the beginning of the rock era (not buying into that one), what's remarkable here isn't the boldness of declaring a post-Beatles year the apotheosis of a genre they're credited with perfecting, so much as the fact that the opinion no longer reads as contrarian or even particularly controversial. Hepworth sets out to "shatter the cliché that the early ’70s were a mere lull before the punk rock storm." Without many of us even noticing, the ’70s—funk and glam's early years included—have carved out as exalted a place in the pop-music canon as the 60s. In many ways, their masterpieces speak more powerfully to the present than the highlights of any other decade in the 20th century; yeah, Sinatra included.

Despite the fact that 1971 began with the legal dissolution of the Beatles, a moment Hepworth identifies as the end of the pop era and the beginning of the rock era (not buying into that one), what's remarkable here isn't the boldness of declaring a post-Beatles year the apotheosis of a genre they're credited with perfecting, so much as the fact that the opinion no longer reads as contrarian or even particularly controversial. Hepworth sets out to "shatter the cliché that the early ’70s were a mere lull before the punk rock storm." Without many of us even noticing, the ’70s—funk and glam's early years included—have carved out as exalted a place in the pop-music canon as the 60s. In many ways, their masterpieces speak more powerfully to the present than the highlights of any other decade in the 20th century; yeah, Sinatra included.

In the mid 1960s, British and American pop musicians began incorporating the ideas of the pop art movement into their recordings. English art pop musicians drew from their art school studies, while in America the style intersected with the Beat Generation and folk music's subsequent singer-songwriter movement. After its "golden age," art pop would thrive as post-punk, industrial, and synthpop, as well as the British New Romantic scene of the 1980s. The genre further developed with artists who rejected conventional rock instrumentation and structure in favor of dance styles and the synthesizer; bands like Depeche Mode and The Pet Shop Boys. The Teens saw new art-pop trends develop, such as hip-hop artists drawing on visual art and vaporwave artists exploring elements of contemporary capitalism. Paul Lester, from The Guardian and Melody Maker, stated, “…the golden age of adroit, intelligent art-pop, to the days when 10cc, Roxy Music and Sparks themselves were mixing and matching from different genres and eras, well before the term 'postmodern' existed in the pop realm." Certainly no one would argue the carefree and stylized hippie ideology, but there was something in the 70s air far more disconcerting to parents than long hair and Renaissance Faire wardrobes: Glam was just weird. When my father saw the album covers for Transformer and Aladdin Sane, and, heavens, Jobriath or Klaus Nomi, I never heard the end of it. From his POV, Jim Morrison was just a young Marlboro Man, but Bowie in a dress? I don't think he was ever the same; at least not until I got married.

In the mid 1960s, British and American pop musicians began incorporating the ideas of the pop art movement into their recordings. English art pop musicians drew from their art school studies, while in America the style intersected with the Beat Generation and folk music's subsequent singer-songwriter movement. After its "golden age," art pop would thrive as post-punk, industrial, and synthpop, as well as the British New Romantic scene of the 1980s. The genre further developed with artists who rejected conventional rock instrumentation and structure in favor of dance styles and the synthesizer; bands like Depeche Mode and The Pet Shop Boys. The Teens saw new art-pop trends develop, such as hip-hop artists drawing on visual art and vaporwave artists exploring elements of contemporary capitalism. Paul Lester, from The Guardian and Melody Maker, stated, “…the golden age of adroit, intelligent art-pop, to the days when 10cc, Roxy Music and Sparks themselves were mixing and matching from different genres and eras, well before the term 'postmodern' existed in the pop realm." Certainly no one would argue the carefree and stylized hippie ideology, but there was something in the 70s air far more disconcerting to parents than long hair and Renaissance Faire wardrobes: Glam was just weird. When my father saw the album covers for Transformer and Aladdin Sane, and, heavens, Jobriath or Klaus Nomi, I never heard the end of it. From his POV, Jim Morrison was just a young Marlboro Man, but Bowie in a dress? I don't think he was ever the same; at least not until I got married.

The Velvet Underground, which interpolated raw Garage Rock and psychedelia with lengthy drone and noise passages, unorthodox guitar tunings and feedback, and subject matter generally centered around stark lyrical topics, are considered the starting point of art rock. Where the VU were art rock's Genesis, Roxy was its catalyst alongside Bowie and Iggy and Lou, though the movement wasn't all glam and androgyny, it included jazz, western classical, funk, avant-garde and electronica, including in its grasp Pink Floyd, Peter Gabriel, John Cale, David Sylvian, Sparks and the myriad of incarnations that have been and will be King Crimson. Today, bands/artists like Radiohead, The Mars Volta, Muse and Sufjan Stevens have picked up any slack and the artistry carries on.

In his recent book Never a Dull Moment: 1971—The Year That Rock Exploded, British music critic David Hepworth argues that 1971 "saw the release of more influential albums than any year before or since." (Hepworth happened to be 21 at the time, which either kills his credibility or renders it unimpeachable.) Led Zeppelin IV, Joni Mitchell's Blue, Marvin Gaye's What's Going On, David Bowie's Hunky Dory, Carole King's Tapestry, Sly & the Family Stone's There’s a Riot Goin' On, Leonard Cohen's Songs of Love and Hate, and Black Sabbath's Master of Reality are only the beginning of the list.

Despite the fact that 1971 began with the legal dissolution of the Beatles, a moment Hepworth identifies as the end of the pop era and the beginning of the rock era (not buying into that one), what's remarkable here isn't the boldness of declaring a post-Beatles year the apotheosis of a genre they're credited with perfecting, so much as the fact that the opinion no longer reads as contrarian or even particularly controversial. Hepworth sets out to "shatter the cliché that the early ’70s were a mere lull before the punk rock storm." Without many of us even noticing, the ’70s—funk and glam's early years included—have carved out as exalted a place in the pop-music canon as the 60s. In many ways, their masterpieces speak more powerfully to the present than the highlights of any other decade in the 20th century; yeah, Sinatra included.

Despite the fact that 1971 began with the legal dissolution of the Beatles, a moment Hepworth identifies as the end of the pop era and the beginning of the rock era (not buying into that one), what's remarkable here isn't the boldness of declaring a post-Beatles year the apotheosis of a genre they're credited with perfecting, so much as the fact that the opinion no longer reads as contrarian or even particularly controversial. Hepworth sets out to "shatter the cliché that the early ’70s were a mere lull before the punk rock storm." Without many of us even noticing, the ’70s—funk and glam's early years included—have carved out as exalted a place in the pop-music canon as the 60s. In many ways, their masterpieces speak more powerfully to the present than the highlights of any other decade in the 20th century; yeah, Sinatra included. In the mid 1960s, British and American pop musicians began incorporating the ideas of the pop art movement into their recordings. English art pop musicians drew from their art school studies, while in America the style intersected with the Beat Generation and folk music's subsequent singer-songwriter movement. After its "golden age," art pop would thrive as post-punk, industrial, and synthpop, as well as the British New Romantic scene of the 1980s. The genre further developed with artists who rejected conventional rock instrumentation and structure in favor of dance styles and the synthesizer; bands like Depeche Mode and The Pet Shop Boys. The Teens saw new art-pop trends develop, such as hip-hop artists drawing on visual art and vaporwave artists exploring elements of contemporary capitalism. Paul Lester, from The Guardian and Melody Maker, stated, “…the golden age of adroit, intelligent art-pop, to the days when 10cc, Roxy Music and Sparks themselves were mixing and matching from different genres and eras, well before the term 'postmodern' existed in the pop realm." Certainly no one would argue the carefree and stylized hippie ideology, but there was something in the 70s air far more disconcerting to parents than long hair and Renaissance Faire wardrobes: Glam was just weird. When my father saw the album covers for Transformer and Aladdin Sane, and, heavens, Jobriath or Klaus Nomi, I never heard the end of it. From his POV, Jim Morrison was just a young Marlboro Man, but Bowie in a dress? I don't think he was ever the same; at least not until I got married.

In the mid 1960s, British and American pop musicians began incorporating the ideas of the pop art movement into their recordings. English art pop musicians drew from their art school studies, while in America the style intersected with the Beat Generation and folk music's subsequent singer-songwriter movement. After its "golden age," art pop would thrive as post-punk, industrial, and synthpop, as well as the British New Romantic scene of the 1980s. The genre further developed with artists who rejected conventional rock instrumentation and structure in favor of dance styles and the synthesizer; bands like Depeche Mode and The Pet Shop Boys. The Teens saw new art-pop trends develop, such as hip-hop artists drawing on visual art and vaporwave artists exploring elements of contemporary capitalism. Paul Lester, from The Guardian and Melody Maker, stated, “…the golden age of adroit, intelligent art-pop, to the days when 10cc, Roxy Music and Sparks themselves were mixing and matching from different genres and eras, well before the term 'postmodern' existed in the pop realm." Certainly no one would argue the carefree and stylized hippie ideology, but there was something in the 70s air far more disconcerting to parents than long hair and Renaissance Faire wardrobes: Glam was just weird. When my father saw the album covers for Transformer and Aladdin Sane, and, heavens, Jobriath or Klaus Nomi, I never heard the end of it. From his POV, Jim Morrison was just a young Marlboro Man, but Bowie in a dress? I don't think he was ever the same; at least not until I got married. The Velvet Underground, which interpolated raw Garage Rock and psychedelia with lengthy drone and noise passages, unorthodox guitar tunings and feedback, and subject matter generally centered around stark lyrical topics, are considered the starting point of art rock. Where the VU were art rock's Genesis, Roxy was its catalyst alongside Bowie and Iggy and Lou, though the movement wasn't all glam and androgyny, it included jazz, western classical, funk, avant-garde and electronica, including in its grasp Pink Floyd, Peter Gabriel, John Cale, David Sylvian, Sparks and the myriad of incarnations that have been and will be King Crimson. Today, bands/artists like Radiohead, The Mars Volta, Muse and Sufjan Stevens have picked up any slack and the artistry carries on.

Published on May 13, 2018 05:19

May 12, 2018

The Ghosts of My Life

Japan formed in 1974 when David Sylvian (David Alan Batt) was just 16 and listening to Roxy's Stranded; Brother, Steve Jansen, was 15. Heavily inspired by Bowie and Bolan, the band's greatest influence was obviously Roxy Music. With a similar vocal range and nasal vibrato, David Sylvian was often compared (and often negatively) to Bryan Ferry, though the similar vocal styles are surface level at worst. Sylvian wouldn't argue the influence of Ferry, but the copycat press that Japan received was unwarranted. The first two albums, and even to a degree Quiet Life, have a more proto-punk tinge than a true Roxy influence, if anything sounding like "Virginia Plain" Roxy sans Eno. With Gentlemen Take Polaroids any hint of a Roxy influence was diminished.

Japan formed in 1974 when David Sylvian (David Alan Batt) was just 16 and listening to Roxy's Stranded; Brother, Steve Jansen, was 15. Heavily inspired by Bowie and Bolan, the band's greatest influence was obviously Roxy Music. With a similar vocal range and nasal vibrato, David Sylvian was often compared (and often negatively) to Bryan Ferry, though the similar vocal styles are surface level at worst. Sylvian wouldn't argue the influence of Ferry, but the copycat press that Japan received was unwarranted. The first two albums, and even to a degree Quiet Life, have a more proto-punk tinge than a true Roxy influence, if anything sounding like "Virginia Plain" Roxy sans Eno. With Gentlemen Take Polaroids any hint of a Roxy influence was diminished. Having hardly given the first two albums a tumble, Quiet Life (AM6 - 1979) came as a great surprise. It was the first LP on which the band created its own distinctive aesthetic of atmospheric, ambient pop. "Quiet Life," "In Vogue" and "Fall in Love With Me" are the album's signature tunes, moody electronic pop, while "Alien" is superb atmospherics painted on an eerie electronic canvas. "All Tomorrow's Parties" is an exceptional cover of the Velvet's original, while the album's other cover, "I Second that Emotion" (only originally available on the B side of the "Quiet Life" 45), is less distinctive, while still effective. Sylvian was but 19 upon its release.

Having hardly given the first two albums a tumble, Quiet Life (AM6 - 1979) came as a great surprise. It was the first LP on which the band created its own distinctive aesthetic of atmospheric, ambient pop. "Quiet Life," "In Vogue" and "Fall in Love With Me" are the album's signature tunes, moody electronic pop, while "Alien" is superb atmospherics painted on an eerie electronic canvas. "All Tomorrow's Parties" is an exceptional cover of the Velvet's original, while the album's other cover, "I Second that Emotion" (only originally available on the B side of the "Quiet Life" 45), is less distinctive, while still effective. Sylvian was but 19 upon its release.  Gentlemen Take Polaroids (AM8 - 1980) was the LP that most encapsulated what Japan was about. It oozes plastic cool; modern, clinical sophistication at the dawn of the digital age (although the synths were mostly, if not entirely, analogue). In fact, the synths are one of the factors that make this a stand-out LP. Rarely are keyboards used as effectively - thanks to Richard Barberi's wizardry, they effortlessly alternate from icy New Wave to warm, gooey analogue lusciousness - which happens to fit perfectly with the fluid purring of Mick Karn's fretless bass, and Sylvian's austere vocals. The most affecting track on the album is the mystical and desolately romantic piano ballad "Nightporter;" eerie as all hell. This was a breakthrough album and its influence can still be noted.

Gentlemen Take Polaroids (AM8 - 1980) was the LP that most encapsulated what Japan was about. It oozes plastic cool; modern, clinical sophistication at the dawn of the digital age (although the synths were mostly, if not entirely, analogue). In fact, the synths are one of the factors that make this a stand-out LP. Rarely are keyboards used as effectively - thanks to Richard Barberi's wizardry, they effortlessly alternate from icy New Wave to warm, gooey analogue lusciousness - which happens to fit perfectly with the fluid purring of Mick Karn's fretless bass, and Sylvian's austere vocals. The most affecting track on the album is the mystical and desolately romantic piano ballad "Nightporter;" eerie as all hell. This was a breakthrough album and its influence can still be noted.When artists idolize their predecessors, they take on the nuances of the original. One doesn't readily recognize the influence of Robert Johnson on Clapton or Keith Richards; similarly there isn't much in the way of Beatles or Beach Boys in Billy Corgan's Smashing Pumpkins (Corgan’s professed heroes), but the influence is there. When a young artist like David Sylvian takes on the persona of Bryan Ferry, one cannot fault the press for saying so disparagingly, and yet Ferry was merely a catalyst for Sylvian. He metamorphosed from funk at 14, elevated synthpop to synth sophistication during his 20s, and evolved from avant-garde wordsmith-songstylist in the 90s to whatever he is with the release of There is a Light That Enters Houses With No Other House in Sight (which, if you are so inclined, you can check out here - link corrected from original post).

Published on May 12, 2018 06:00

May 11, 2018

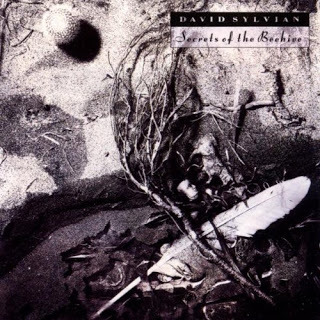

David Sylvian - Secret of the Beehive

In honeybee populations, males are insignificant. Thousands vie for their shot at the virgin queen, while only a lucky(?) few succeed. They mount the queen in flight, who stores the semen from her midair tryst the rest of her life. When the drone pulls away, his barbed penis rips from his body, and he dies shortly thereafter — what a buzz kill.

In honeybee populations, males are insignificant. Thousands vie for their shot at the virgin queen, while only a lucky(?) few succeed. They mount the queen in flight, who stores the semen from her midair tryst the rest of her life. When the drone pulls away, his barbed penis rips from his body, and he dies shortly thereafter — what a buzz kill.None of this means anything in relation to Secrets of the Beehive, David Sylvian's most haunting LP, but the odd reality of it. Sylvian's 1987 LP is a tour de force of life's heady realities. Listening to it earlier, I was about to say, "Why, there's even a kettle boiling in the background to track 3," when I realized it was my own kettle whistling on the stove, which provides some idea of how this beautiful album can entrance one away from reality.

Sylvian's voice is the LP's most important element, balanced perfectly amidst the intricate string and percussion arrangements of Ryuichi Sakamoto; it's a warmer Nick Cave — still shadowy, but not so intensely dark — yet it's instrumentation remains sparse, allowing the music to rise to fore in jazzy improvisation, particularly Mark Isham's atmospheric brass. Secret of the Beehive is lovely, sculptured ambient music, each side with its own ethereal groove. Side One begins with the instant fiction of "September," setting the pace. By Side Two we are lost in the flamenco-tinged "When Poets Dreamed Of Angels." One can nearly feel the dancers stamping their feet to the music, as if we were in Catalonia having a drop of Cava.

And yet the pervasive melancholy is sly and ironic. In "Let The Happiness In," like Depeche Mode’s "But Not Tonight" or The Cure's "A Thousand Hours," the listener is gripped with rip your heart out foreboding (add in Talk Talk's Spirit of Eden). Beautiful. (There's a handful of soulfully miserable music to fill a night of sadness – we all appreciate those with our Prozac.)

And yet the pervasive melancholy is sly and ironic. In "Let The Happiness In," like Depeche Mode’s "But Not Tonight" or The Cure's "A Thousand Hours," the listener is gripped with rip your heart out foreboding (add in Talk Talk's Spirit of Eden). Beautiful. (There's a handful of soulfully miserable music to fill a night of sadness – we all appreciate those with our Prozac.)Still, atmospherics and mood vie in Beehive with the literary. In "When Poets Dreamed Of Angels," Sylvian writes, "She rises early from bed, Runs to the mirror, The bruises inflicted in moments of fury. He kneels beside her once more, Whispers a promise, Next time I'll break every bone in your body." Certainly horrid imagery, but beautiful writing that exposes our often difficult humanity. For honeybees, the "little death"

(look it up) is a reality and part and parcel to the big death. The reality is our friends the dolphins are bullies; cute little sea otters, I won't even go into it. Life is cruel and beautiful, carefree, like our Cava in Spain, harsh like breaking bones. Beehive is haunting and gorgeous and an LP often glossed over.

Published on May 11, 2018 05:28

Caedmon and Sylvian

The tradition of English poetry began with Caedmon–an illiterate seventh-century layman, ashamed of his inability to "versify" when the harp was passed around at a feast. Caedmon fell asleep in a stable among the animals and dreamed of an angel (a story not so far removed from Robert Johnson's). The angel, too, bade him sing, and again Caedmon protested that he did not know any songs, yet inexplicably, he found himself obeying the angel's dictum. Upon waking, he wrote a eulogy to the world and its maker transmitted to him through his dream. Today, the nine-line "Caedmon’s Hymn" is the earliest known English poem–a product of what poets now often call "dictation." Poetry is at its best from somewhere "other" – a source beyond the poet's ego and conscious mind. Sometimes the poem appears in dreams, as with Caedmon; sometimes during autohypnosis, as with William Butler Yeats or in the case of James Merrill, the Ouija board. No one would argue that for David Sylvian the muse is a bit of a waif, a gypsy, a banshee, a jazz moll, Venus, a dark alley. While Beehive is far from a pop LP, Sylvian has eased further and further away from the pop sensibility. His isn't music that one puts on at dinner, save that for James Taylor. David Sylvian is a hard listen, alone at 3am. Like Joyce or Yeats, Sylvian is difficult. I don't know that Sylvian was thinking of Caedmon when he wrote "When the Poets Dreamed of Angels," but that is exactly what poetry should do, allow its reader, or music its listener, to interpret and to dream.

There is a long path from Adolescent Sex to Tin Drum to There's a Light That Enters Houses With No Other House in Sight, but Sylvian's existential mark hasn't wavered, despite his collaborations with Fripp or Holgar Czukay or Sakamoto, or even with Caedmon.

Published on May 11, 2018 05:27

May 10, 2018

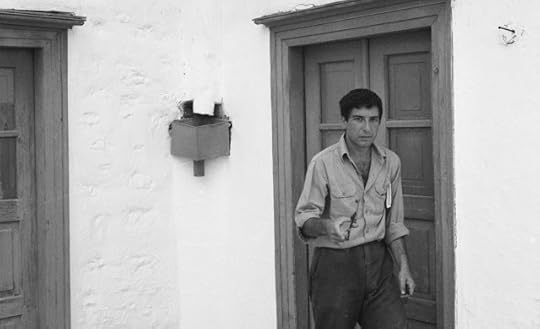

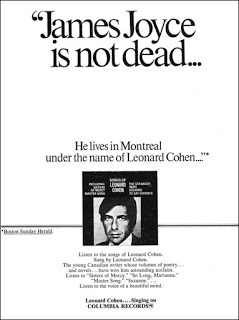

Leonard Cohen - Suzanne - AM10

The Songs of Leonard Cohen, Cohen's first release, is as close to a ten as one can get without being there. There's a disconnect that nicks away its perfection, the way that the over-embellished orchestration of Let It Be upstages the songs themselves. Let It Be - Naked proved that familiarity trumps what could have been, but I'd nonetheless like to hear Songs trimmed down to a more primitive level. Still, it's the freshman delivery that fails here. Songs is somewhat William-Shatneresque, if...you...think.....about it. That said, Cohen's debut is as tenny as a nine can get. The lyrics are nothing less than evolutionary, and "Suzanne," the AM10 single from the collection is the penultimate Cohen tune (only surpassed by the nearly 11 "Famous Blue Raincoat").

The Songs of Leonard Cohen, Cohen's first release, is as close to a ten as one can get without being there. There's a disconnect that nicks away its perfection, the way that the over-embellished orchestration of Let It Be upstages the songs themselves. Let It Be - Naked proved that familiarity trumps what could have been, but I'd nonetheless like to hear Songs trimmed down to a more primitive level. Still, it's the freshman delivery that fails here. Songs is somewhat William-Shatneresque, if...you...think.....about it. That said, Cohen's debut is as tenny as a nine can get. The lyrics are nothing less than evolutionary, and "Suzanne," the AM10 single from the collection is the penultimate Cohen tune (only surpassed by the nearly 11 "Famous Blue Raincoat").

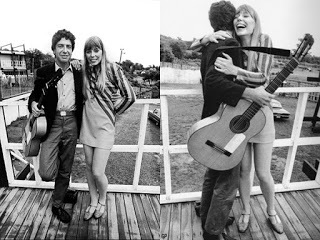

For a few months in 1967 and 1968, Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen had a fling, the consequences of which continued to echo in their work. Introduced backstage at Judy Collins' songwriter's workshop at the 1967 Newport Folk Festival by Collins herself, Cohen and Mitchell were officially an item by the time the two of them co-hosted a workshop at the Mariposa Folk Festival. Their romance ignited, flared, and exhausted itself within months.

Joni said of Suzanne, "I'd met him and I went, 'I love that song. What a great song.' Really. "Suzanne" was one of the greatest songs I ever heard. So I was proud to meet an artist. He made me feel humble, because I looked at that song and I went, 'Woah. All my songs seem so naive by comparison.' It raised the standard of what I wanted to write."

Cohen, who was better known as a poet and novelist than as a musician, was 33 when they met; Mitchell was nine years his junior. Conveniently, Cohen was often in New York where he would spend time with Mitchell, who was living at the Earl Hotel in the Village, and Mitchell was routinely playing dates in Montreal, where Cohen lived. Cohen also spent a month at Mitchell’s Laurel Canyon home when he was recruited by Hollywood in 1968 to score a movie based on "Suzanne." (The movie project failed to materialize.) Joni’s "Rainy Night House" is her farewell account of that liaison. "I went one time to his home and I fell asleep in his old room and he sat up and watched me sleep. He sat up all the night and he watched me to see who in the world I could be."

The second verse is poignantly bittersweet:

The second verse is poignantly bittersweet:

I am from the Sunday school

I sing soprano in the upstairs choir

You are a holy man

On the FM radio

I sat up all the night and watched thee

To see, who in the world you might be

Mitchell points out, "There’s some poetic liberty with those two lines; actually it's "You sat up all night and watched me to see who in the world …" I turned it around. Leonard was in a lot of pain. Hungry ghosts is what it's called in Buddhism. I am even lower. Five steps down." Funny how we tend to associate lyrics in our own lives, hardly thinking about how songs relate to the lives of the songwriter. T.S. Eliot would love our ability to dismiss the poet, but I find so much intrigue in the understory. Suzanne, btw, is Suzanne Verdal (not his wife, Suzanne Elrod - many make this error), with whom Cohen had a friendship, though not an intimate one, long before Joni. Just a snippet of her story reveals the literal nature of Cohen's lyrics: "The St. Lawrence River held a particular poetry and beauty to me and I decided to live there with [my] daughter, Julie. Leonard heard about this place I was living, with crooked floors and a poetic view of the river, and he came to visit me many times. We had tea together many times and mandarin oranges." And as we know, they came all the way from China.

As a general rule, Leonard Cohen is about as cool as cool can be. Bob Dylan dedicates songs to him and wrote "I'm not there" in awestruck emulation of the man. Joni still talks like he's a "holy man." Can you imagine, the Norton Anthology says, "Suzanne" is one of the few songs which works as well as a song as it does as poetry. We've discussed rock lyrics as poetry in the past and that's a cool accolade. Still, it late; best to let those lyrics speak for themselves:

Suzanne takes you down to her place by the river

You can hear the boats go by You can spend the night beside her And you know that she's half crazy But that's why you want to be there And she feeds you tea and oranges That come all the way from China And just when you mean to tell her That you have no love to give her Then she gets you on her wavelength And she lets the river answer That you've always been her lover And you want to travel with her And you want to travel blind And you know that she will trust you For you've touched her perfect body with your mind.

And Jesus was a sailor When he walked upon the water And he spent a long time watching From his lonely wooden tower And when he knew for certain Only drowning men could see him He said "All men will be sailors then Until the sea shall free them" But he himself was broken Long before the sky would open Forsaken, almost human He sank beneath your wisdom like a stone And you want to travel with him And you want to travel blind And you think maybe you'll trust him For he's touched your perfect body with his mind.

Now Suzanne takes your hand And she leads you to the river She is wearing rags and feathers From Salvation Army counters And the sun pours down like honey On our lady of the harbor And she shows you where to look Among the garbage and the flowers There are heroes in the seaweed There are children in the morning They are leaning out for love And they will lean that way forever While Suzanne holds the mirror And you want to travel with her And you want to travel blind And you know that you can trust her For she's touched your perfect body with her mind.

Published on May 10, 2018 04:14

May 8, 2018

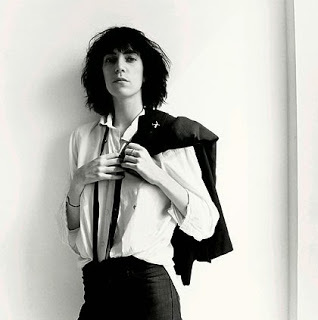

Patti Smith - Horses

Patti Smith by Robert MapplethorpeA poem has a backdrop of silence, while lyrics mesh with melody, rhythm, and instrumentation. It's that silence in poetry that has the most marked impact; a silence so noticeably missing in an album like Horses.

Patti Smith by Robert MapplethorpeA poem has a backdrop of silence, while lyrics mesh with melody, rhythm, and instrumentation. It's that silence in poetry that has the most marked impact; a silence so noticeably missing in an album like Horses."Gloria," the interpolation of Van Morrison's old chestnut with Smith's own "In Excelsis Deo," may be the single most audacious introductory statement in rock history. Opening with the line "Jesus died for somebody's sins, but not mine," Patti Smith's Horses was hell-bent on liberating rock 'n' roll from its structural and constraints. The debate on whether or not she succeeded is moot, simply because reaching for the moon and stars is the stuff of which great art is made.

The vigorous grandeur that is Horses comes from Patti Smith's persistent emphasis on lyrics, on the poetry without the silence. Dylan and Paul Simon had already brought poetry alive in their songs, but Patti took it a step further, to the point of using the lyrics and her singularly evocative delivery as a structuring principle for the rhythm and pace of the tracks. "Birdland" starts as a quiet piano-based ballad with Patti's narrative about a boy at his father's funeral looking at the sky:

It was as if someone had spread butter on all the fine points of the stars'Cause when he looked up they started to slip.Then he put his head in the crux of his armAnd he started to drii-iiift, DRII-IIIFT to-OOO the beeEElly of a shii-iiip.

With that one word, "drift," Smith goes from speaking to singing while the song drifts, rocking like a ship, the guitar building to Dionysian revelry - scattered "like roses" on top of the beat, the beat, the beat. Poetry is the sole rhythm, the soul rhythm - moving, moving towards the epiphany of the shaman bouquet, growing and exploding in furious repetition, repetition and then, the river of glass, the helium raven, and up up up up to the shaman's final incantation: "Sha da do wop, da shaman do way, sha da do wop, da shaman do way.”

With that one word, "drift," Smith goes from speaking to singing while the song drifts, rocking like a ship, the guitar building to Dionysian revelry - scattered "like roses" on top of the beat, the beat, the beat. Poetry is the sole rhythm, the soul rhythm - moving, moving towards the epiphany of the shaman bouquet, growing and exploding in furious repetition, repetition and then, the river of glass, the helium raven, and up up up up to the shaman's final incantation: "Sha da do wop, da shaman do way, sha da do wop, da shaman do way.” Horses is a deeply rooted and spiritual journey, even if it doesn't sound like one (iconic punk albums

I know Patti Smith only in retrospect, having just a cursory listen in the 70s and that on radio with the Springsteen cover "Because the Night." It wouldn't be until Wave that I really sat down and listened. I remember the moment when I first heard "Frederick" and "Dancing Barefoot." I was 15, smoking a bowl in a friend's garage, and suddenly everything paled in comparison. My heart will eternally belong to Joni Mitchell, but on that day, Patti Smith ripped out my soul. I listened to Easter next, and on the third day, Horses. I was young, but how had I missed it? Horses is an AM10.

Published on May 08, 2018 19:09

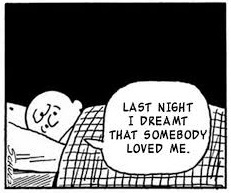

A Priori Like a Rolling Stone

Feelings of absurdity and emptiness are prevalent in rock music, from The Beatles to Counting Crows. With my iTunes on shuffle I was submerged this afternoon in a barrage of existentialism (and you’re telling me there's no God?). First, '''Round Here," a pensive, dreamlike piece in which Counting Crow's Adam Duritz begins by poetically expressing his feelings of invisibility with the quietly sung "Step out the front door like a ghost/ into the fog where no one notices/ the contrast of white on white." He mentions walking in the rain, being lost in thought and asks the question with double meaning, "Where? I don't know." He can't seem to figure anything out as he mentions the "crumbling difference between wrong and right" and then introduces Maria, a character as confused and dissatisfied as he. Maria is perplexed about sex and religion and feels "she's more than just a little misunderstood." Both he and Maria feel lost and confused in a muddled absurd reality. Their confusion is never resolved, and the song ends with Duritz's desperate cries that he "can't see nothin'" and that he's "under the gun 'round here." The song is the cry of young people trying to figure out their lives and find meaning in an absurd reality.

I need a phone call. I need a raincoat.

A less discouraging and seemingly more peaceful expression of life's absurdity came decades before with The Beatles' "Strawberry Fields Forever," second on my computer's little existential jaunt. Lennon shows no bitterness or anger at the fact that "nothing is real," though he seems critical of people who don't acknowledge the absurdity of reality: "Living is easy with eyes closed/ Misunderstanding all you see." He seems to be content when he sings, "But you know I know when it's a dream,” referring to Strawberry Fields, presumably a metaphor for life. He says that in this bizarre, meaningless life, "It's getting hard to be someone,/ But it all works out./ It doesn't matter much to me." Essentially, we are alone and existence is absurd.

Track 3 was a fusion of the two themes, this one again from The Beatles. "Eleanor Rigby," is but a haunting earworm about lonely people living meaningless lives. McCartney's voice, though sweet, is filled with anguish and despair, accompanied by a string orchestra of frustrated violins and melancholy cello. The song first describes Eleanor Rigby, a woman who "lives in a dream" and keeps up her looks as she keeps up her life. The next description is of Father MacKenzie, who writes sermons no one will listen to and keeps his socks darned (though no one will see them). McCartney asks "What does he care?" and ponders where "all the lonely people" belong. Not only do these people fail to draw meaning from outside, they seemingly have no meaning within themselves.

Track 3 was a fusion of the two themes, this one again from The Beatles. "Eleanor Rigby," is but a haunting earworm about lonely people living meaningless lives. McCartney's voice, though sweet, is filled with anguish and despair, accompanied by a string orchestra of frustrated violins and melancholy cello. The song first describes Eleanor Rigby, a woman who "lives in a dream" and keeps up her looks as she keeps up her life. The next description is of Father MacKenzie, who writes sermons no one will listen to and keeps his socks darned (though no one will see them). McCartney asks "What does he care?" and ponders where "all the lonely people" belong. Not only do these people fail to draw meaning from outside, they seemingly have no meaning within themselves.I wondered, "What can possibly be next, iTunes? 'Fool on the Hill'"? That man no one wants to know, living alone in a "world spinning 'round," totally disconnected from society? No one listens to him or likes him, and he doesn't seem to care... Or maybe Dylan and that rolling stone? Let's see, this woman used to be a rich socialite but has fallen from her aristocratic status; she is living alone on the streets and is presumably a prostitute. Dylan asks her how it feels to be "without a home/ Like a complete unknown/ Like a rolling stone." He calls her "Miss Lonely" and describes her wasted education at an expensive school. He seems to have little pity for her current situation because her past was empty and worthless. She has now been turned out into the cold, unfeeling streets, and doesn't have inside her what it takes to survive alone.

Caroline, No

But it got worse.

The next random choice from iTunes was The Beach Boys' "I Just Wasn't Made For These Times," from Pet Sounds. Brian Wilson sings in a soft, sad voice, "I keep looking for a place to fit/ Where I can speak my mind." The chorus consists of background vocals crying, "Can't find nothin' I can put my heart and soul into" in between the lead vocal's confession, "Sometimes I feel very sad... " And when he sings, "I guess I just wasn't made for these times," Brian is conveying both existential isolation and a lack of meaning in his life. The universe is void of a priori meaning, therefore, we can create and assign whatever meaning we want. And because we are free to create meaning, we are also responsible for the meaning we create, but that, dear friends, is often too hard and we turn to others or God or we put on some music, just not on shuffle.

Published on May 08, 2018 04:48

May 7, 2018

AM tries to create a Zen-like flow to its posts, one topi...

AM tries to create a Zen-like flow to its posts, one topic that leads seamlessly to the next. With our current focus on poetry that can lead to odd bedfellows. When I think about those artists who to me best exemplify poetry in lyrics, I think of Joni Mitchell and Morrissey, two poet-lyricists that have virtually nothing in common but the English language (and in Morrissey's case, at times that ventures onto different paths).

Published on May 07, 2018 06:10