R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 75

May 2, 2018

I saw the best minds of my generation...

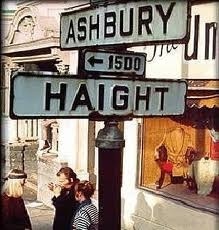

Things are cyclical. (Things. Funny word. Means everything and anything. Other words have come and gone, from "shit" to "junk" to "jawn," yet we always colloquially revert back to "things.") The word "hippie," as well, derives from "hip" and "hipster," (which of course is the millennials' lazy incarnation of the hippie) and was initially used to describe Beatniks who'd moved into Greenwich Village, Venice, and the Haight. The origins of the terms "hip" and "hep" are uncertain, yet by the 1940s both had become part of jive slang and meant "fashionable or up-to-date." The Beats adopted the term "hip," and early hippies inherited the language and counter-cultural values of the Beat Generation. They created their own communities, listened to psychedelic music, embraced the sexual revolution, and used drugs such as cannabis, LSD, and psilocybin mushrooms to explore altered states of consciousness. Since the 1960s, hippie culture has been assimilated by mainstream society, including health food, music festivals, contemporary sexual mores, and the cyberspace revolution.

Things are cyclical. (Things. Funny word. Means everything and anything. Other words have come and gone, from "shit" to "junk" to "jawn," yet we always colloquially revert back to "things.") The word "hippie," as well, derives from "hip" and "hipster," (which of course is the millennials' lazy incarnation of the hippie) and was initially used to describe Beatniks who'd moved into Greenwich Village, Venice, and the Haight. The origins of the terms "hip" and "hep" are uncertain, yet by the 1940s both had become part of jive slang and meant "fashionable or up-to-date." The Beats adopted the term "hip," and early hippies inherited the language and counter-cultural values of the Beat Generation. They created their own communities, listened to psychedelic music, embraced the sexual revolution, and used drugs such as cannabis, LSD, and psilocybin mushrooms to explore altered states of consciousness. Since the 1960s, hippie culture has been assimilated by mainstream society, including health food, music festivals, contemporary sexual mores, and the cyberspace revolution. George Harrison in San FranciscoIn 1967, the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco and the Elysian Fields' Love-in popularized hippie culture, leading to the Summer of Love on the Left Coast, and Woodstock in the East. Hippies in Mexico, known as jipitecas, formed La Onda and gathered at Avándaro, while in New Zealand, nomadic housetruckers practiced alternative lifestyles and promoted sustainable energy at Nambassa. In the United Kingdom, mobile "peace convoys" of new age travelers made summer pilgrimages to free music festivals at Stonehenge and later (in 1970) to the gigantic Isle of Wight Festival with a crowd of around half a million. In Australia, hippies gathered at Nimbin for the 1973 Aquarius Festival and the annual Cannabis Law Reform Rally or MardiGrass. "Piedra Roja Festival", a major hippie event in Chile, was held in 1970.

George Harrison in San FranciscoIn 1967, the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco and the Elysian Fields' Love-in popularized hippie culture, leading to the Summer of Love on the Left Coast, and Woodstock in the East. Hippies in Mexico, known as jipitecas, formed La Onda and gathered at Avándaro, while in New Zealand, nomadic housetruckers practiced alternative lifestyles and promoted sustainable energy at Nambassa. In the United Kingdom, mobile "peace convoys" of new age travelers made summer pilgrimages to free music festivals at Stonehenge and later (in 1970) to the gigantic Isle of Wight Festival with a crowd of around half a million. In Australia, hippies gathered at Nimbin for the 1973 Aquarius Festival and the annual Cannabis Law Reform Rally or MardiGrass. "Piedra Roja Festival", a major hippie event in Chile, was held in 1970. A July 1968 Time magazine study on hippie philosophy credited the foundation of the hippie movement with historical precedent as far back as the counterculture of the Ancient Greeks, espoused by philosophers like Diogenes of Sinope and the Cynics as early examples of hippie culture. It also named as notable influences the religious and spiritual teachings of Henry David Thoreau, Hillel the Elder, Jesus, Buddha, St. Francis of Assisi, Gandhi, and J.R.R. Tolkien. The first signs of modern "proto-hippies" emerged in fin de siècle Europe. Between 1896 and 1908, a German youth movement arose as a countercultural reaction to the organized social and cultural clubs that centered on German folk music. Known as Der Wandervogel ("migratory bird"), the movement opposed the formality of traditional German clubs, instead emphasizing amateur music and singing, creative dress, and communal outings involving hiking and camping. Inspired by the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Goethe, Hermann Hesse, and Eduard Baltzer, Wandervogel attracted thousands of young Germans who rejected the rapid trend toward urbanization and yearned for the pagan, back-to-nature spiritual life of their ancestors.

A July 1968 Time magazine study on hippie philosophy credited the foundation of the hippie movement with historical precedent as far back as the counterculture of the Ancient Greeks, espoused by philosophers like Diogenes of Sinope and the Cynics as early examples of hippie culture. It also named as notable influences the religious and spiritual teachings of Henry David Thoreau, Hillel the Elder, Jesus, Buddha, St. Francis of Assisi, Gandhi, and J.R.R. Tolkien. The first signs of modern "proto-hippies" emerged in fin de siècle Europe. Between 1896 and 1908, a German youth movement arose as a countercultural reaction to the organized social and cultural clubs that centered on German folk music. Known as Der Wandervogel ("migratory bird"), the movement opposed the formality of traditional German clubs, instead emphasizing amateur music and singing, creative dress, and communal outings involving hiking and camping. Inspired by the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Goethe, Hermann Hesse, and Eduard Baltzer, Wandervogel attracted thousands of young Germans who rejected the rapid trend toward urbanization and yearned for the pagan, back-to-nature spiritual life of their ancestors. During the first several decades of the 20th century, Germans settled around the United States, bringing the values of the Wandervogel with them. Over time, young Americans adopted the beliefs and practices of the new immigrants. One group, called the "Nature Boys", took to the California desert and raised organic food, espousing a back-to-nature lifestyle like the Wandervogel.

During the first several decades of the 20th century, Germans settled around the United States, bringing the values of the Wandervogel with them. Over time, young Americans adopted the beliefs and practices of the new immigrants. One group, called the "Nature Boys", took to the California desert and raised organic food, espousing a back-to-nature lifestyle like the Wandervogel. Beats like Allen Ginsberg crossed over from the beat movement and became fixtures of the burgeoning hippie and anti-war movements. By 1965, hippies had become an established social group in the U.S., while the hippie ethos influenced The Beatles and others in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe, and they, in turn, influenced their American counterparts. Hippie culture spread worldwide through a fusion of rock music, folk, blues, and psychedelic rock; it found expression in literature, the dramatic arts, fashion, and the visual arts, including film, posters advertising rock concerts, and album covers.

...destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked.

Published on May 02, 2018 04:28

May 1, 2018

It's a Gas...

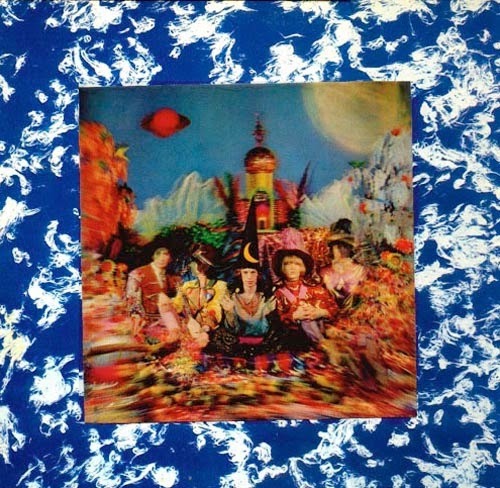

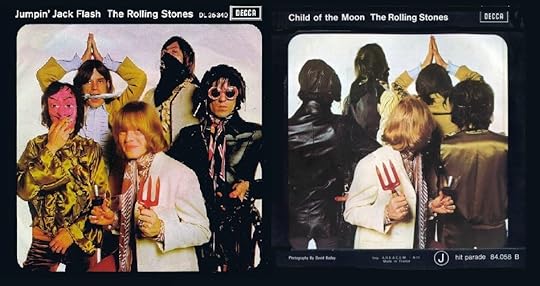

In an effort to mimic Sgt. Pepper, the Rolling Stones offered up Their Satanic Majesties Request (AM3), a fabulous album cover and a bookmark in time, but a disaster that could have marked the Stones' death throes. Relatively unlistenable, Their Satanic Majesties Request had decent tracks in "She's a Rainbow" and "200 Light Years From Home," though it is mostly doggerel that only enhanced the failure that was, and shouldn't have been, Between the Buttons. With 1966's Aftermath and hits like "Under My Thumb" and "Mother's Little Helper," it seemed the Stones had stepped out from under The Beatles' shadow. From a critical standpoint, Between the Buttons, the follow-up to Aftermath, was the album that exemplified the Stones' bluesy roots and elevated them beyond where The Beatles had already ventured. No one seemed to care; the mindset was still AM oriented (AOR and FM radio were yet to come) and the lack of radio play didn't fair well for the Stones. With Satanic Majesties, it seemed the end was near.

In an effort to mimic Sgt. Pepper, the Rolling Stones offered up Their Satanic Majesties Request (AM3), a fabulous album cover and a bookmark in time, but a disaster that could have marked the Stones' death throes. Relatively unlistenable, Their Satanic Majesties Request had decent tracks in "She's a Rainbow" and "200 Light Years From Home," though it is mostly doggerel that only enhanced the failure that was, and shouldn't have been, Between the Buttons. With 1966's Aftermath and hits like "Under My Thumb" and "Mother's Little Helper," it seemed the Stones had stepped out from under The Beatles' shadow. From a critical standpoint, Between the Buttons, the follow-up to Aftermath, was the album that exemplified the Stones' bluesy roots and elevated them beyond where The Beatles had already ventured. No one seemed to care; the mindset was still AM oriented (AOR and FM radio were yet to come) and the lack of radio play didn't fair well for the Stones. With Satanic Majesties, it seemed the end was near. Essentially, Their Satanic Majesties Request wasn't even the Stones. On no occasion was each member of the band at the studio simultaneously. This was all Mick pretending to be Wilson or McCartney, and failing miserably. The other members would record their input to be left for Jagger, despite the credit to The Rolling Stones as producer. From the excessive jam, "Sing This All Together (See What Happens)," to the horrid, even frightening, Bill Lyman song, "In Another Land," the LP should have never been released. "The Lantern" may as well be The Strawberry Alarm Clock or the gang from Scooby Doo, though it lacks the charm of either. I own the LP based solely on "She's a Rainbow" and the fabulous lenticular (3D) album cover.

Essentially, Their Satanic Majesties Request wasn't even the Stones. On no occasion was each member of the band at the studio simultaneously. This was all Mick pretending to be Wilson or McCartney, and failing miserably. The other members would record their input to be left for Jagger, despite the credit to The Rolling Stones as producer. From the excessive jam, "Sing This All Together (See What Happens)," to the horrid, even frightening, Bill Lyman song, "In Another Land," the LP should have never been released. "The Lantern" may as well be The Strawberry Alarm Clock or the gang from Scooby Doo, though it lacks the charm of either. I own the LP based solely on "She's a Rainbow" and the fabulous lenticular (3D) album cover.There are those who claim that it wasn't until the Beatles' demise that the Stones came into their own. This is not the case, as the Stones' best period comes from out of the ashes of all those who set Satanic Majesties alight. Like Elvis that same year, a comeback was in order; a reaffirmation of past successes that began April 20, 1968 with the recording of "Jumpin' Jack Flash" (AM10 – single).

"Jumpin Jack Flash" was written in Keith Richards' country home, at which Jagger was awakened by the sound of a gardener in the yard. Richards stated, "Oh, that's Jack – that's Jumpin' Jack." One almost has to say to himself, "Thank God!" the song is so monumental in the Stones' canon. In Rolling Stone magazine Jagger stated that the song came "out of all the acid of Satanic Majesties. It's about having a hard time and getting out. Just a metaphor for getting out of all the acid things." "Jumpin’ Jack Flash" was something brand new based on something old. It was re-imagined Robert Johnson that didn't follow the rules, it broke them and made new ones. It was the Genesis of the Stones who would go on to offer Beggar's Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers and Exile - all in a row.

Published on May 01, 2018 12:15

April 30, 2018

Written Late at Night When I Was Supposed to Be Working On My Novel

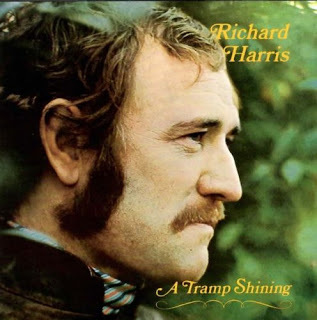

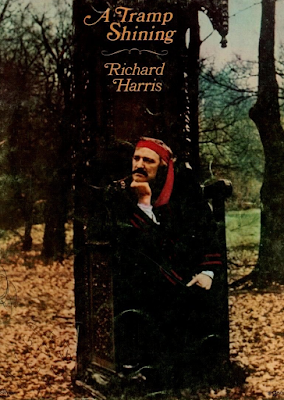

My father had a short list of favorite songs that included Glen Campbell's "Where's the Playground Suzie?", "Wives and Lovers" from Jack Jones and Andy William's "Moon River," but two of his favorites, the only songs in which he'd sing along in a deep off-key monotone, were "MacArthur Park" by Richard Harris and Ann Murray's "Snowbird." My mother, a backup studio singer for the likes of Burt Bacharach and Herb Alpert, did an LP with Ray Conniff and the Singers called Turn Around Look at Me, an album with a stunning 1960s-a-go-go-like blonde on the cover. One of the tracks was "MacArthur Park." Conniff would eventually fire my mother during the production of the LP We've Only Just Begun, but not before they recorded "Snowbird." Though my parents would divorce before either of those songs were ever released, this has for me always been a connection they shared.

My father had a short list of favorite songs that included Glen Campbell's "Where's the Playground Suzie?", "Wives and Lovers" from Jack Jones and Andy William's "Moon River," but two of his favorites, the only songs in which he'd sing along in a deep off-key monotone, were "MacArthur Park" by Richard Harris and Ann Murray's "Snowbird." My mother, a backup studio singer for the likes of Burt Bacharach and Herb Alpert, did an LP with Ray Conniff and the Singers called Turn Around Look at Me, an album with a stunning 1960s-a-go-go-like blonde on the cover. One of the tracks was "MacArthur Park." Conniff would eventually fire my mother during the production of the LP We've Only Just Begun, but not before they recorded "Snowbird." Though my parents would divorce before either of those songs were ever released, this has for me always been a connection they shared.So "MacArthur Park" at six years old was as simple as simple got: It was like this cake was, like, in the rain and it was, like, melting and the guy can't have another one ever because he doesn't know the recipe. Oh, no. We often associate songs with things that occurred in our lives. Brain research has shown the olfactory as the most memory inducing; I'd argue music. Sometimes there's a direct correlation: a love song that takes you back to a specific romance; a record that whisks you to some epic party in the Valley and you want to throw up when you hear it because that's what you did six times that night because the quaaludes were Lemmon and not Rorer. Other songs evoke an emotion only your subconscious comprehends. For a song like "MP," it's often both.

The setting is an iconic park in Downtown L.A. I was born and raised in California. My mother was born and raised in L.A. My family had been there since the year Zorro. The song was overly dramatic, and that was me, even at six.

"Between the parted pages and were pressedIn love’s hot, fevered ironLike a striped pair of pants."

"Between the parted pages and were pressedIn love’s hot, fevered ironLike a striped pair of pants."Deep, man! (And forget, btw, those turgid, ridiculous allusions to oral sex you may have heard – it’s just not true – it can't be Jimmy!) Many will point to the idiocy of Webb's lyrics, all that sweet green icing flowing down and all (I mean, seriously, green icing? What flavor is green?) And yet, in my pre-teen consciousness I learned in seven minutes the perspective of not taking anything too seriously, being able to spot and laugh at absurdity. More importantly, I learned about romance – those things that today, 50 years later, break my heart so profoundly that I need medication: "After all the loves of my life, you’ll still be the one." It seemed so romantic, so quixotic: finding that one special person who would always be "the one." Sigh. Today I can't even remember the names of half the girls who were "the one," but found another who is.

There's a whole stanza where Harris sings about the future course of his life, Webb-style. He'll win and lose "the worship in their eyes." He'll have dreams, he'll drink wine (Richard Harris drank a LOT of wine), he'll be up, he'll be down, he'll have stuff, he'll put this stuff into perspective, he'll be Dumbledore, etc. It's the fucking 2001 of pop songs!

Jimmy Webb's arrangements are typical of the sixties: lavish, loud and simply too much as Harris's untrained voice creeks and deafens the trained ear, and the LP, A Tramp Shining, takes it to the upper limits with lush musical interludes and swingin' singles songs about girls. "MP," though, has to be the single weirdest song ever. Period. Little has been understood about its strange, incomprehensible lyric, but Harris sounds so very convincing, as if he knew indeed what was going on. His dramatic approach and the over-orchestration of the music has the listener waiting for an answer, a clue, a lesson… Everyone on the planet should own a copy of "MacArthur Park," or better yet, of A Tramp Shining; a late at night album when those party liggers simply will not leave. A Tramp Shining is sure to do the trick. Ah, then you'll be able to wallow in whatever this wonderful shit is.

The song, originally written at the request of producer Bones Howe for The Association. Howe had asked that Webb create a song with classical elements and time changes, but was unhappy with the result. "MacArthur Park" was released 50 years ago today.

Published on April 30, 2018 03:39

April 29, 2018

He's walkin' through the clouds...

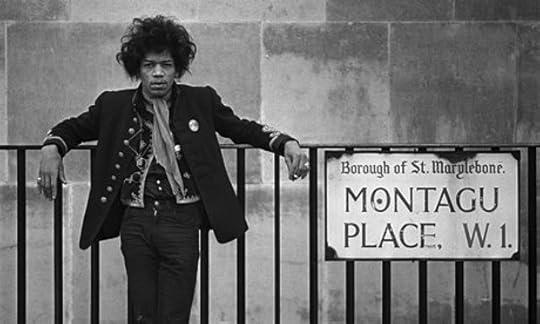

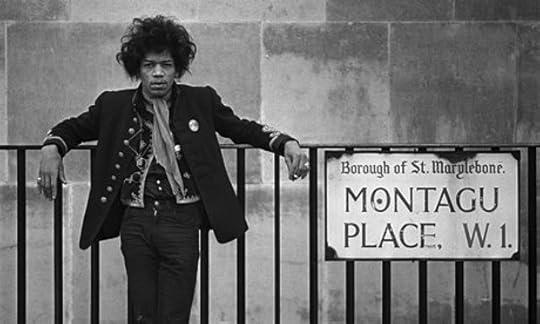

Lansdowne CrescentOn the morning of September 21, 1966, a Pan Am airliner from New York landed at Heathrow carrying among its passengers an American musician barely known in his own country and a complete stranger to England. His name was James Marshall Hendrix.

Lansdowne CrescentOn the morning of September 21, 1966, a Pan Am airliner from New York landed at Heathrow carrying among its passengers an American musician barely known in his own country and a complete stranger to England. His name was James Marshall Hendrix.On September 18, 1970, four years later, came a story of extreme urgency on the front page of the London Evening Examiner and a photo of Hendrix playing the Isle of Wight festival, only 18 days earlier. The text reported how Hendrix had died that morning in a hotel on Lansdowne Crescent in Notting Hill.

During those three years, 362 days living in London, Hendrix had conjured – with his vision and sense of sound, his personality and genius – the most extraordinary guitar music ever played, indeed the most remarkable soundscape ever created. Opinion varies only over the effect his music has on people: elation, fear, sexual stimulation, sublimation, disgust – all or none of these – but always drop-jawed amazement.

Nearly 50 years later, nothing really has changed. We ponder whether the true guitar master is Clapton or David Gilmour, Jack White or Steve Howe, but no one questions Jimi's impact, his mastery or sell-your-soul-to-the-devil virtuosity.

Published on April 29, 2018 15:02

Repost: He's walkin' through the clouds...

Lansdowne CrescentOn the morning of September 21, 1966, a Pan Am airliner from New York landed at Heathrow carrying among its passengers an American musician from a poor home. Barely known in his own country and a complete stranger to England, he had just flown first class for the first time in his life. His name was James Marshall Hendrix.

Lansdowne CrescentOn the morning of September 21, 1966, a Pan Am airliner from New York landed at Heathrow carrying among its passengers an American musician from a poor home. Barely known in his own country and a complete stranger to England, he had just flown first class for the first time in his life. His name was James Marshall Hendrix.On September 18, 1970, four years later, there was a story of extreme urgency on the front page of the London Evening Examiner and a picture of Hendrix playing the Isle of Wight festival, only 18 days earlier. The text reported how Hendrix had died that morning in a hotel on Lansdowne Crescent in Notting Hill.

During those three years, 362 days living in London, Hendrix had conjured – with his vision and sense of sound, his personality and genius – the most extraordinary guitar music ever played, the most remarkable soundscape ever created; of that there is little argument. Opinion varies only over the effect his music has on people: elation, fear, sexual stimulation, sublimation, disgust – all or none of these – but always drop-jawed amazement.

And today, 45 years later, nothing really has changed. We ponder whether the guitar master is Clapton or David Gilmour, Jack White or Steve Howe, but no one questions Jimi's impact, his mastery or sell-your-soul-to-the-devil virtuosity (a la Robert Johnson).

September 18th should be a day of celebration over shear remembrance, a day to pull out the vinyl, scratches and all – play it all day, and tonight, slow it down, think, put on "Little Wing"…

Well, she's walking through the clouds,

With a circus mind that's running wild,

Butterflies and Zebras,

And Moonbeams and fairy tales.

That's all she ever thinks about.

Riding with the wind.

When I'm sad, she comes to me,

With a thousand smiles she gives to me free.

It's alright, she says it's alright,

Take anything you want from me,

Anything.

Fly on little wing.

Published on April 29, 2018 15:02

From the Novel Miles From Nowhere - Hendrix

In the dawn's light we witnessed those who remained, the chemically disoriented throngs covered in dried mud. The knoll above the stage was scattered with people and garbage and muck. We retreated to the Hatfield's and found our way inside. People were sleeping, Hatfield was making scrambled eggs, there was coffee and we ate. I needed food. I'd left my medication in the van. I felt weak and my face felt rubbery, but no one said a thing.

In the dawn's light we witnessed those who remained, the chemically disoriented throngs covered in dried mud. The knoll above the stage was scattered with people and garbage and muck. We retreated to the Hatfield's and found our way inside. People were sleeping, Hatfield was making scrambled eggs, there was coffee and we ate. I needed food. I'd left my medication in the van. I felt weak and my face felt rubbery, but no one said a thing. I heard someone say, "Bethel's in the Bible, man. It's the place where Jacob envisioned a stairway to Heaven; the messengers of God going up it and down it." We curled up on an Indian blanket and fell asleep. "Up and down they tramped in the glory of God."

The music, like a dream soundtrack, was familiar, heavy and discordant. I opened my eyes. Farm Girl was drooling on my sleeve. "Come-on. Come-on." It was Hendrix. Jimi was playing "Foxy Lady." The time had come. My father told me all about the journey. He was a journeyman. But it was nice when you got there, when you arrived. Farm Girl and I slipped through the barrier that was now but an accordion of mangled wire mesh. The pyramid of storage boxes was in ruin, much of it poached or toppled, but the fences of Woodstock's DMZ were down and we ambled through the crowd unencumbered. There were throngs of people leaving. I was still perplexed. "Where are they going," I said. I found it disconcerting. "Why are they going?"

"It’s not about them," Farm Girl said, and then Jimi chimed in, "You can leave if you want to. We’re just jammin', that's all." Those who remained were huddled together, loosely, the band of brothers and sisters like the holocaust aftermath in a science fiction film. Hendrix played "Izabella" and "Gypsy Woman" and "Fire," and then the best; Jimi and the band in radical improvisation, offbeat and discordant, a cacophony both jarring and harmonious.

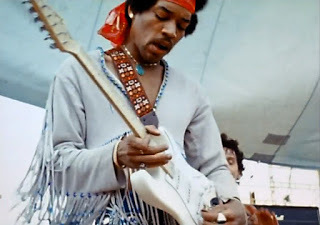

"It’s not about them," Farm Girl said, and then Jimi chimed in, "You can leave if you want to. We’re just jammin', that's all." Those who remained were huddled together, loosely, the band of brothers and sisters like the holocaust aftermath in a science fiction film. Hendrix played "Izabella" and "Gypsy Woman" and "Fire," and then the best; Jimi and the band in radical improvisation, offbeat and discordant, a cacophony both jarring and harmonious.I blocked it all out, the mud people, the stage, even Farm Girl or my father or Lori or my illness; it was all just Jimi, shining there before me in white leather fringe, his Stratocaster upside down and backward. He was the alpha and the omega. He launched into the "Star Spangled Banner," his guitar so pure and piercing, its dissonance all the news one needed to comprehend the times, the war, the assassinations. He initiated the fire of guns, the bombs bursting in air, all within the confines of a white Fender guitar. It said far more about the timber of America than a hundred partisan tirades.

But I didn't care about protest and bombs. It was just the sonic possibilities of music. Jimi didn't pluck strings, he whacked them and thwacked them and let the amp's reverberation recirculate through the pickups in a loop of feedback, the guitar virtually playing itself.

But I didn't care about protest and bombs. It was just the sonic possibilities of music. Jimi didn't pluck strings, he whacked them and thwacked them and let the amp's reverberation recirculate through the pickups in a loop of feedback, the guitar virtually playing itself.He played "Purple Haze" and "Hey Joe" and I burst into tears. I sat on the muddy knoll and cried; great tears of sorrow and of joy coursing through me simultaneously. I pulled my knees up and rested my head and that was that. Woodstock was over. I sat for a very long time.

The residue of acid and emotion flew from me suddenly, like a demon exorcised. I looked up and I was alone on Yasgur's Farm. Farm Girl was gone, there was no one on stage, the faithful retraced their steps back to their cars and their homes. I was adrift in a sea of garbage and swill.

And then I saw Farm Girl. In that magic bag of hers, she'd found another outfit, bell-bottomed dungarees and a halter top. She looked fresh and clean somehow and I was filthy like a pig in a sty. She took my mud-crusted mitt in hers and pulled me to my feet. She said, "I'm leaving with the Hatfields," or whatever their name was.

"Oh. You are," I said.

"I am. I have to get home. My family's waiting for me. They worry."

"'Kay."

"I enjoyed our time together. Really. You're a real nice guy." What do you say to that, "Thanks"? What was I going to do, cry out, No, wait, don't go? Of course not. Our parting was inevitable. It just would have been nice to have a little lunch or something, share a meal.

"It was nice." She smiled. "Prettiest smile."

"Hardly." She laughed. "Big ol' space in my teeth. Should of had braces."

"Don't."

"Can't afford it anyway."

"Don't." She hugged me and I kissed her and she walked down the knoll. She didn't turn back. Hatfield was meticulously loading a big bolt of green canvas onto the bed of a truck. He put up the tailgate and the truck pulled away. The little boy saw me up the hill and he waved. So did Hatfield. They got in an orange and white Econoline panel truck. I would have thought a wagon with two black mules. Mrs. Hatfield and Farm Girl got in the other side and they fell in line, the caravan slowly pulling onto the highway. I wasn't feeling sorry for myself, I'd been over that for a long time, but the song in my head was "Fool On the Hill."

It dawned on me that I didn't have any shoes. I watched as the Econoline sat at the intersection, its blinker on. And then it was gone. I walked down the hill and through the trenches. I crossed over the planks and the downed fence to where the tent had been. There was a cardboard box. In it were my shoes and a sandwich and a guitar pick. Maybe it was Jimi's. Maybe it was Hatfield's. Didn't matter. It was nice to have shoes and a sandwich and a souvenir.

- From the upcoming novel Miles from Nowhere

Published on April 29, 2018 15:01

Repost: Electric Ladyland - "1983...A Merman I Should Turn To Be"

Electric Ladyland sprawls over four sides, spinning with ambition, noble failures, and grand successes. Hendrix, like Brian Wilson, was using the studio as an instrument, stretching the ideas cycling through him. It was typical for a year that was less rich in its output than in its studio prep for '69, though Hendrix was so focused that, like the Beatles, he wasn't merely dragging his feet. Some of Jimi's most radio-friendly hits appear on Electric Ladyland ("All Along the Watchtower," "Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)," and "Crosstown Traffic"), if only on the new FM format, but on side 3, is found the album's jewel and centerpiece, "1983…(A Merman I Should Turn To Be)," a proto-prog epic on the art of walking away from the nonsense humanity inflicts upon itself, "not to die but to be reborn, away from the land so battered and torn." While "Watchtower" is the LP's one-two punch, "Merman" is a wild, left-field, Bolero-paced march where Hendrix overlaps the guitars and bass like a string section, affecting oceanic waves and surf, with Mitch Mitchell's oddly syncopated drumming as counterpoint, and the flute improvisations of Chris Wood (on loan from Traffic) offering a spacey ambiance.

Electric Ladyland sprawls over four sides, spinning with ambition, noble failures, and grand successes. Hendrix, like Brian Wilson, was using the studio as an instrument, stretching the ideas cycling through him. It was typical for a year that was less rich in its output than in its studio prep for '69, though Hendrix was so focused that, like the Beatles, he wasn't merely dragging his feet. Some of Jimi's most radio-friendly hits appear on Electric Ladyland ("All Along the Watchtower," "Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)," and "Crosstown Traffic"), if only on the new FM format, but on side 3, is found the album's jewel and centerpiece, "1983…(A Merman I Should Turn To Be)," a proto-prog epic on the art of walking away from the nonsense humanity inflicts upon itself, "not to die but to be reborn, away from the land so battered and torn." While "Watchtower" is the LP's one-two punch, "Merman" is a wild, left-field, Bolero-paced march where Hendrix overlaps the guitars and bass like a string section, affecting oceanic waves and surf, with Mitch Mitchell's oddly syncopated drumming as counterpoint, and the flute improvisations of Chris Wood (on loan from Traffic) offering a spacey ambiance. The 60s, of course, were a very different time. Today, young people are technology junkies. People are in love their phones, but here was a song written at a time when folks were pulling back from technology, rejecting the system, leaving corporate jobs to live on communes, trying to "get back to the land." Idealistically, working on a farm didn't mean driving a tractor, it meant grabbing a hoe, achieving self-sufficiency while living as nature intended.

And there was far more to it. April 1968, when the final version of "1983" was recorded (an acoustic demo version was recorded in March), was a tumultuous month for America. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination and the subsequent riots affected Hendrix deeply, and he dedicated an extended instrumental to King on April 6 at the Newark Symphony Hall.

Hurray

I awake from yesterday

Alive but the war is here to stay So my love Catherina and me Decide to take our last walk thru the noise to the sea Not to die but to be reborn Away from the lands so battered and torn Forever Oh say can you see it's really such a mess Every inch of earth is a fighting nest Giant pencil and lipstick-tube shaped things Continue to rain and cause screaming pain And the arctic stains from silver blue to bloody red As our feet find the sand And the sea is straight ahead

As "pencil and lipstick tube shaped things" (missiles) have made the surface unlivable, notably melting the "arctic" from "blue to bloody red," the only solution for the protagonist is to escape this dystopia, build machines to breathe underwater, become a "merman," and swim to the utopian Atlantis. The lyrics of the first verse hints at an allegorical subtext to the narrative, particularly the phrase, "alive but the war is here to stay," which in 1968 might refer to the Vietnam War, the domestic conflicts with the police, or both. Hendrix would later make an allusion to America's civil rights unrest as a "war" in an introduction to the song "Machine Gun" at a December 1970 concert, which he dedicated to "all the soldiers that are fighting in Chicago, and Milwaukee, and New York—oh yes, and all the soldiers fighting in Vietnam."

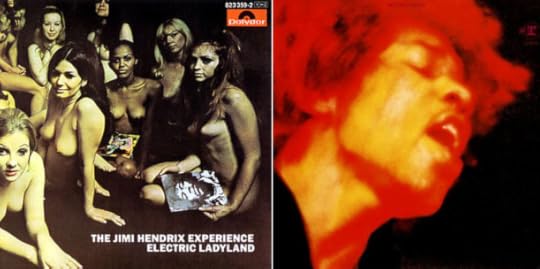

The second verse of "1983" begins with an allusion to "The Star Spangled Banner": "Oh, say can you see it's such really such a mess." This reference to the U.S. national anthem and following image of "giant pencil and lipstick-tube shaped things" that "rain and cause screaming pain" are particularly significant. Both this verse and the war episode — the guitar sound painting of bombs, missiles, and air raid sirens — make a similar statement. While Hendrix obfuscated any direct social context here, it is significant that he would provide "1983" as an example of social commentary; the narrative is about a war-torn world, and yet the track isn't simply anti-war; Hendrix shows a disgust with the world we'd built. Interestingly, Hendrix found this kind of dissatisfaction in his own corporate undertakings. The American version of the LP utilized an intense unauthorized photograph of Hendrix in black, red and yellow. Hendrix had expressly requested a Linda Eastman photo of the trio sitting on the Alice in Wonderland sculpture in New York's Central Park. While he commented that the label disregarded his wishes, it was the European cover that set him over the edge, a gatefold photo of 19 nude women by David Montgomery. He referred to it as the "naked lady" cover and called it "disrespectful."

Soft spoken and congenial, Hendrix was often bullied on a corporate level. He remained apolitical for the most part, but in "1983," Hendrix reared his head in a fury only surpassed by his discordant and pointed "Star Spangled Banner" at Woodstock.

Published on April 29, 2018 15:01

Miles From Nowhere - Hendrix

In the dawn's light we witnessed those who remained, the chemically disoriented throngs covered in dried mud. The knoll above the stage was scattered with people and garbage and muck. We retreated to the Hatfield’s and found our way inside. People were sleeping, Hatfield was making scrambled eggs, there was coffee and we ate. I needed food. I’d left my medication in the van. I felt weak and my face felt rubbery, but no one said a thing.

In the dawn's light we witnessed those who remained, the chemically disoriented throngs covered in dried mud. The knoll above the stage was scattered with people and garbage and muck. We retreated to the Hatfield’s and found our way inside. People were sleeping, Hatfield was making scrambled eggs, there was coffee and we ate. I needed food. I’d left my medication in the van. I felt weak and my face felt rubbery, but no one said a thing. I heard someone say, "Bethel's in the Bible, man. It's the place where Jacob envisioned a stairway to Heaven; the messengers of God going up it and down it." We curled up on an Indian blanket and fell asleep. "Up and down they tramped in the glory of God."

The music, like a dream soundtrack, was familiar, heavy and discordant. I opened my eyes. Farm Girl was drooling on my sleeve. "Come-on. Come-on." It was Hendrix. Jimi was playing "Foxy Lady." The time had come. My father told me all about the journey. He was a journeyman. But it was nice when you got there, when you arrived. Farm Girl and I slipped through the barrier that was now but an accordion of mangled wire mesh. The pyramid of storage boxes was in ruin, much of it poached or toppled, but the fences of Woodstock's DMZ were down and we ambled through the crowd unencumbered. There were throngs of people leaving. I was still perplexed. "Where are they going," I said. I found it disconcerting. "Why are they going?"

"It’s not about them," Farm Girl said, and then Jimi chimed in, "You can leave if you want to. We’re just jammin', that's all." Those who remained were huddled together, loosely, the band of brothers and sisters like the holocaust aftermath in a science fiction film. Hendrix played "Izabella" and "Gypsy Woman" and "Fire," and then the best; Hendrix and the band in radical improvisation, offbeat and discordant, a cacophony both jarring and harmonious.

"It’s not about them," Farm Girl said, and then Jimi chimed in, "You can leave if you want to. We’re just jammin', that's all." Those who remained were huddled together, loosely, the band of brothers and sisters like the holocaust aftermath in a science fiction film. Hendrix played "Izabella" and "Gypsy Woman" and "Fire," and then the best; Hendrix and the band in radical improvisation, offbeat and discordant, a cacophony both jarring and harmonious.I blocked it all out, the mud people, the stage, even Farm Girl or my father or Lori or my illness; it was all just Jimi, shining there before me in white leather fringe, his Stratocaster upside down and backwards. He was the alpha and the omega. He launched into the "Star Spangled Banner," his guitar so pure and piercing, its dissonance all the news one needed to comprehend the times, the war, the assassinations. He initiated the fire of guns, the bombs bursting in air, all within the confines of a white Fender guitar. It said far more about the timber of America than a hundred partisan tirades.

But I didn't care about protest and bombs. It was just the sonic possibilities of music. Jimi didn't pluck strings, he whacked them and thwacked them and let the amp's reverberation recirculate through the pickups in a loop of feedback, the guitar virtually playing itself.

But I didn't care about protest and bombs. It was just the sonic possibilities of music. Jimi didn't pluck strings, he whacked them and thwacked them and let the amp's reverberation recirculate through the pickups in a loop of feedback, the guitar virtually playing itself.He played "Purple Haze" and "Hey Joe" and I burst into tears. I sat on the muddy knoll and cried; great tears of sorrow and of joy coursing through me simultaneously. I pulled my knees up and rested my head and that was that. Woodstock was over. I sat for a very long time.

The residue of acid and emotion flew from me suddenly, like a demon exorcised. I looked up and I was alone on Yasgur's Farm. Farm Girl was gone, there was no one on stage, the faithful retraced their steps back to their cars and their homes. I was adrift in a sea of garbage and swill.

And then I saw Farm Girl. In that magic bag of hers, she'd found another outfit, bell-bottomed dungarees and a halter top. She looked fresh and clean somehow and I was filthy like a pig in a sty. She took my mud-crusted mitt in hers and pulled me to my feet. She said, "I'm leaving with the Hatfields," or whatever their name was.

"Oh. You are," I said.

"I am. I have to get home. My family's waiting for me. They worry."

"'Kay."

"I enjoyed our time together. Really. You're a real nice guy." What do you say to that, "Thanks"? What was I going to do, cry out, No, wait, don't go? Of course not. Our parting was inevitable. It just would have been nice to have a little lunch or something, share a meal.

"It was nice." She smiled. "Prettiest smile."

"Hardly." She laughed. "Big ol' space in my teeth. Should of had braces."

"Don't."

"Can't afford it anyway."

"Don't." She hugged me and I kissed her and she walked down the knoll. She didn't turn back. Hatfield was meticulously loading a big bolt of green canvas onto the bed of a truck. He put up the tailgate and the truck pulled away. The little boy saw me up the hill and he waved. So did Hatfield. They got in an orange and white Econoline panel truck. I would have thought a wagon with two black mules. Mrs. Hatfield and Farm Girl got in the other side and they fell in line, the caravan slowly pulling onto the highway. I wasn't feeling sorry for myself, I'd been over that for a long time, but the song in my head was "Fool On the Hill."

It dawned on me that I didn't have any shoes. I watched as the Econoline sat at the intersection, its blinker on. And then it was gone. I walked down the hill and through the trenches. I crossed over the planks and the downed fence to where the tent had been. There was a cardboard box. In it were my shoes and a sandwich and a guitar pick. Maybe it was Jimi's. Maybe it was Hatfield's. Didn't matter. It was nice to have shoes and a sandwich and a souvenir.

- From the upcoming novel Miles from Nowhere

Published on April 29, 2018 15:01

Are You Experienced? - Hendrix - Part 2

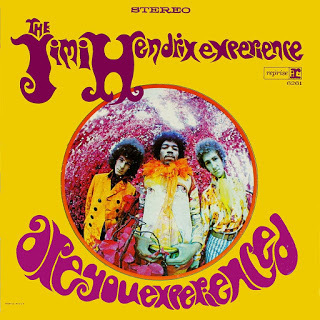

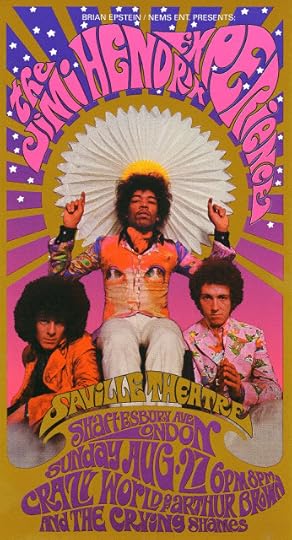

Jimi Hendrix' Are You Experienced, credited to his three-piece outfit, The Jimi Hendrix Experience (with Mitch Mitchell on drums and Noel Redding on bass), turned the music world on edge when released in May '67. Fusing rock, psychedelia and blues, the LP [re]invented the role of the electric guitar as a lead instrument, and pushed the limits of the power-trio, essentially eclipsing Cream at its own game.

Jimi Hendrix' Are You Experienced, credited to his three-piece outfit, The Jimi Hendrix Experience (with Mitch Mitchell on drums and Noel Redding on bass), turned the music world on edge when released in May '67. Fusing rock, psychedelia and blues, the LP [re]invented the role of the electric guitar as a lead instrument, and pushed the limits of the power-trio, essentially eclipsing Cream at its own game. Yet U.K. and U.S. fans were offered different experiences, as the album was issued in two different editions, typical of American releases at the time, capitalizing on the hits that were left off The U.K. version. The U.K. release contained three songs not on the U.S. LP: "Red House," "Remember," and "Can You See Me." The U.S. release instead included the first three British A-side singles, "Hey Joe", "Purple Haze", and "The Wind Cries Mary."

For the U.K. edition, Hendrix & Co. were photographed by famed rock photographer Bruce Fleming, who captured the guitar god wearing a cape and standing over his group like the Prince of Darkness. It was, according to the photographer, not his favorite photo from the shoot, and the artwork, oddly listed the album's title twice without mentioning the band’s name. All in all, the U.K. cover was a pale comparison to the American release.

For the U.K. edition, Hendrix & Co. were photographed by famed rock photographer Bruce Fleming, who captured the guitar god wearing a cape and standing over his group like the Prince of Darkness. It was, according to the photographer, not his favorite photo from the shoot, and the artwork, oddly listed the album's title twice without mentioning the band’s name. All in all, the U.K. cover was a pale comparison to the American release.Hendrix himself was dissatisfied, and requested that a new shoot be set up for the U.S. sleeve. The group's eye-catching, alien look was better served by Karl Ferris' photo of the trio, taken at London’s Kew Gardens. Redding's and Mitchell's hairdos were teased into afros that matched Hendrix' own, while the reverse-color and fish-eye lens effects used for the shoot gave the band an otherworldly look while complementing the shockingly new music within. With evocative bubble lettering typical of the times and a striking yellow wrapper, the sound and image combined to become something which, once experienced, was left indelible.

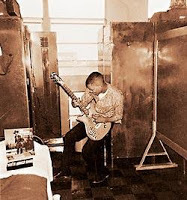

On the recording of the LP, Recording Engineer Eddie Kramer said, "By January 1967, when we started work on Are You Experienced?, Jimi Hendrix had already had a run of successful singles in the UK with 'Hey Joe,' 'Purple Haze' and 'The Wind Cries Mary.' A lot of that work, as well as some other tracks, had been recorded at De Lane Lea Studios in London, but Jimi and the Experience had to get out of there because there was a bank above the studio and they couldn't play loud. But they'd heard about Olympic Studios, where I was a staff engineer. It had just opened up and the Jimi Hendrix Experience were really one of Olympic's first clients. It was brand-new and it was the hippest recording studio in the U.K., if not all the world. The Helios mixing console we had was like nothing else around.

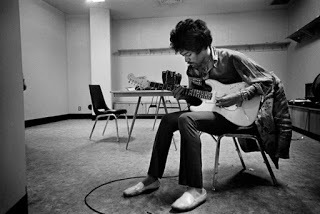

"Jimi was very shy when he first came into the studio. He just sat quietly in the corner and waited for the amps to arrive. He didn't say much until the amps were situated and the drums set up. Then he plugged in and we were off to the races! The sheer volume set me back a bit. But that's what you deal with as an engineer.

“We took the original tapes that they'd recorded elsewhere and overdubbed, fixed and tweaked what had been done previously. Then we just kept on recording and adding more tracks. Jimi was writing material with his producer and manager, Chas Chandler. He was living in Chas' apartment in London and they'd stay up all night working on lyrics, chords and the rest of that. And they'd come into the studio with a completely written song.

Kramer went on to address the title song: "There are a lot of backwards tape tracks on that one — drums, bass and guitar. We cut basic tracks and then flipped the tape over. At the end of the session, I made Jimi a copy of the backwards tracks. He went home and rehearsed himself all night to figure out what the guitar was going to do. He came in the next day, said, 'OK, roll the tape from this point. ...' And he knew from the downbeat precisely what the guitar was going to sound like and what the melody was going to be. He was playing the melody in real time, but he'd figured out how it was going to sound backwards. He was brilliant that way."

It's the American release that has become the iconic version of the LP, and retrospectively the British release indeed pales. The inclusion of the three monster hits accentuates the album, whereas the original release fails to invigorate the listener on the same level. Indeed, where the U.S. version is an AM10, the British release falters with an Absolute Magnitude score of 8. Some would call the U.S. edition a compilation along the lines of The Beatles' Hey Jude, instead the iconic version of Are Your Experienced is the whole package, literally and figuratively; an LP that puts it into the top ten in a year when that truly meant something.

Published on April 29, 2018 14:02

Spanish Castle Magic - Hendrix - Part 1

Rock's history is sketchy at times even in L.A., New York or London. Sketchier still when one ventures into those little towns that were feeders into the rock, blues or country hubs. L.A. is the heart of American music, sharing the bill with London as the recording capital of the world. But few musicians are actually from Los Angeles. Joni Mitchell "couldn't let go of L.A.," but she'd come to the City of [the Fallen] Angels by way of Saskatchewan. Chili Pepper Anthony Keidis is from Michigan; Glenn Frey from New York; Adam Duritz from Baltimore. Each of these artists exude L.A., but California was, and is, merely the destination, not the journey.

Rock's history is sketchy at times even in L.A., New York or London. Sketchier still when one ventures into those little towns that were feeders into the rock, blues or country hubs. L.A. is the heart of American music, sharing the bill with London as the recording capital of the world. But few musicians are actually from Los Angeles. Joni Mitchell "couldn't let go of L.A.," but she'd come to the City of [the Fallen] Angels by way of Saskatchewan. Chili Pepper Anthony Keidis is from Michigan; Glenn Frey from New York; Adam Duritz from Baltimore. Each of these artists exude L.A., but California was, and is, merely the destination, not the journey.  Rather than head to L.A., Jimi Hendrix would make it all the way to London, and yet his roots are enmeshed in a myriad of locales from Nashville to New Jersey (and yes, even Los Angeles). Hendrix though, would spend his formative years in and around Seattle, and the Jet City would provide that spark few recognized before he got to London.

Rather than head to L.A., Jimi Hendrix would make it all the way to London, and yet his roots are enmeshed in a myriad of locales from Nashville to New Jersey (and yes, even Los Angeles). Hendrix though, would spend his formative years in and around Seattle, and the Jet City would provide that spark few recognized before he got to London. Hendrix's first electric guitar was an inexpensive Supro Ozark model his father gave him in 1959. Supro was the brand name for the Valco company, that also produced products for Montgomery Ward under the Airline brand and for Sears using the Silvertone name. Hendrix would play that Ozark in his very first gig, at Seattle's Temple de Hirsch Synagogue in 1960. When the Supro was stolen, Jimi bought a Silvertone 3021 from the Sodo, Washington Sears that he named Betty Jean. It was Betty Jean that Jimi carried throughout his early years in Seattle (after which he'd have a stint in the service before touring with The Isley Brothers in 1964).

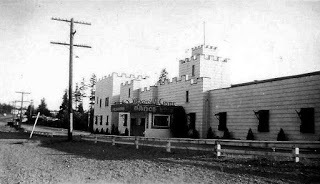

Spanish Castle Roadhouse - Circa 1955In his teens, Jimi's favorite haunt was outside the city limits at The Spanish Castle. A roadhouse built in the 1930s outside town to avoid the city's restrictive liquor laws, The Spanish Castle was a big band era venue that evolved over the years and in the rock era had a lineup that included Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis, Conway Twitty, The Beach Boys, Paul Revere and the Raiders and, later, Hendrix himself. Jimi's first pseudo-gig was a bit of an accident. The Statics blew two amps with Jimi in the audience. Always with his guitar and amp in his "ride," Jimi lent an amp to guitarist to Zach Static (Hoppenrath), and ended up on rhythm guitar. Hendrix would go on to play The Spanish Castle on several occasions. According to Radio KISW, Hendrix was quoted as saying, "The bass player in the band had this beat up car and it would break down every other block on the way there and back." Hence the line, "Takes 'bout half a day to get there,: from "Spanish Castle Magic" from the Axis LP.

Spanish Castle Roadhouse - Circa 1955In his teens, Jimi's favorite haunt was outside the city limits at The Spanish Castle. A roadhouse built in the 1930s outside town to avoid the city's restrictive liquor laws, The Spanish Castle was a big band era venue that evolved over the years and in the rock era had a lineup that included Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis, Conway Twitty, The Beach Boys, Paul Revere and the Raiders and, later, Hendrix himself. Jimi's first pseudo-gig was a bit of an accident. The Statics blew two amps with Jimi in the audience. Always with his guitar and amp in his "ride," Jimi lent an amp to guitarist to Zach Static (Hoppenrath), and ended up on rhythm guitar. Hendrix would go on to play The Spanish Castle on several occasions. According to Radio KISW, Hendrix was quoted as saying, "The bass player in the band had this beat up car and it would break down every other block on the way there and back." Hence the line, "Takes 'bout half a day to get there,: from "Spanish Castle Magic" from the Axis LP. Hendrix' career was a slow rise, from his gigs in the army to his amateur night win at the Apollo, of which he said, "I went to New York and and won first place in the Apollo amateur contest, you know, $25," which led to his short tenure with the Isleys.

Hendrix' career was a slow rise, from his gigs in the army to his amateur night win at the Apollo, of which he said, "I went to New York and and won first place in the Apollo amateur contest, you know, $25," which led to his short tenure with the Isleys. In 1966, Hendrix was playing small clubs in Greenwich Village, particularly Cafe Wha?, as a part of Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. The Animals were big in the U.K. at the time and had had eight U.S. Top 40 hits between August 1964 and June 1966, so when Animals' bassist Bryan 'Chas' Chandler checked out Hendrix live on the advice of Keith Richards’ girlfriend Linda Keith, Hendrix was prepared to listen. The Animals were playing in Central Park, although on the verge of splitting up, and Chas Chandler, already planning his next move, suggested to Hendrix that he relocate to the U.K. (Chandler was in the process of becoming a rock impresario.

Chandler said: "I remember thinking, this cat's wild enough to upset more people than Jagger! When he did Hey Joe, a number I was planning to record as my first independent venture, that clinched it." Hendrix did decide to make the big move and on September 23rd 1966 along with Chas Chandler, formed the Jimi Hendrix Experience in London starting with bassist Noel Redding. Redding was chosen because Hendrix liked his attitude towards music and his "Afro" hairstyle.

Chandler said: "I remember thinking, this cat's wild enough to upset more people than Jagger! When he did Hey Joe, a number I was planning to record as my first independent venture, that clinched it." Hendrix did decide to make the big move and on September 23rd 1966 along with Chas Chandler, formed the Jimi Hendrix Experience in London starting with bassist Noel Redding. Redding was chosen because Hendrix liked his attitude towards music and his "Afro" hairstyle.Then came drummer Mitch Mitchell, a session drummer who'd worked with The Pretty Things, Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, and briefly The Who, while they were looking for a replacement for Doug Sandom: The Who's eventual choice, of course, Keith Moon. Following along the lines of Cream, the power trio, The Jimi Hendrix Experience was born.

Published on April 29, 2018 06:55