R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 77

April 22, 2018

The Man Who Fell To Earth

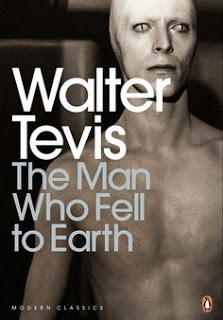

"Released the year before Spielberg and Lucas changed the genre and thus hippie sci-fi's last hurrah, this typically fragmented Nicholas Roeg production stars David Bowie in the role he was born (or perhaps reborn) to play — a distinguished visitor from another world." —J. Hoberman, The Village Voice (1976, 138 min, 35mm).

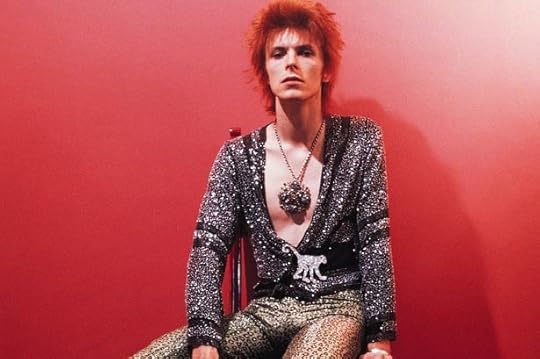

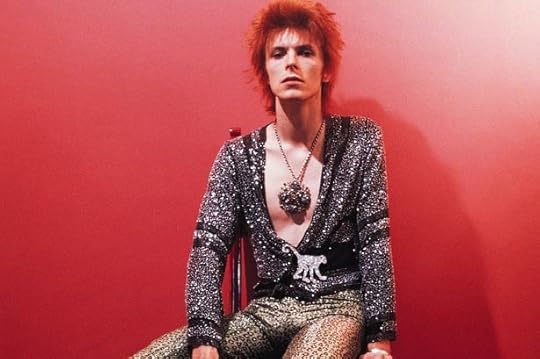

"Released the year before Spielberg and Lucas changed the genre and thus hippie sci-fi's last hurrah, this typically fragmented Nicholas Roeg production stars David Bowie in the role he was born (or perhaps reborn) to play — a distinguished visitor from another world." —J. Hoberman, The Village Voice (1976, 138 min, 35mm).David Bowie is no stranger to film. From Tony Scott's underrated vampire flick The Hunger to Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ (as Pontius Pilate), Bowie’s gaunt, skeletal physique, his otherworldly aura, indeed his alluring alien nature, was the perfect complement to Nicholas Roeg's real-deal alien in the trippy 1976 feature film The Man Who Fell to Earth. Roeg was compelled to cast Bowie as his leading extraterrestrial after watching him in Alan Yentob's way-out-there documentary, Cracked Actor, in which the singer truly resembles an alien life force more than any flesh-and-blood human being.

Roeg's hugely ambitious and imaginative film transforms a straightforward science fiction story (from the 1963 novel by Walter Tevis) into a rich kaleidoscope of contemporary America. Thomas Jerome Newton (Bowie), an alien whose understanding of our world is limited to monitoring TV stations, arrives on earth, builds the largest corporate empire in the U.S. to further his mission, and then becomes increasingly frustrated by human emotion and the surreality of [American] life. What follows is as much a love story as sci-fi. Newton becomes involved in an almost pulp-like romance with Mary Lou (Candy Clark), played out to the pop hits of middle America, which culminates in the man's "fall" from innocence. No other pop sci-fi novels (or films), with the exceptions of Stranger in a Strange Land, Childhood's End and Kurt Vonnegut's Sirens of Titan, truly explore the connection between what is speculative about the future and the pop culture in which we live.

Roeg's hugely ambitious and imaginative film transforms a straightforward science fiction story (from the 1963 novel by Walter Tevis) into a rich kaleidoscope of contemporary America. Thomas Jerome Newton (Bowie), an alien whose understanding of our world is limited to monitoring TV stations, arrives on earth, builds the largest corporate empire in the U.S. to further his mission, and then becomes increasingly frustrated by human emotion and the surreality of [American] life. What follows is as much a love story as sci-fi. Newton becomes involved in an almost pulp-like romance with Mary Lou (Candy Clark), played out to the pop hits of middle America, which culminates in the man's "fall" from innocence. No other pop sci-fi novels (or films), with the exceptions of Stranger in a Strange Land, Childhood's End and Kurt Vonnegut's Sirens of Titan, truly explore the connection between what is speculative about the future and the pop culture in which we live.  Ultimately revealing his alien form to Mary Lou, who is overwhelmed and terrified, the couple split. Betrayed by confidant, Dr. Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), Newton is imprisoned by the government in a luxury condo. Intermittent cut scenes show a wife and child slowly dying on Newton's home planet. By film's end, his family has perished and Newton is marooned on earth. We cried when Earth nearly killed E.T., but E.T., in contrast, made a friend and found his way home. In Roeg's space opera, Earth becomes the alien's home, but the result is a broken spirit. (Imagine Spielberg making something like that.) The Man Who Fell to Earth is a sci-fi Days of Wine and Roses for the art house crowd. The cinematography by Anthony B. Richmond looks fantastic and Bowie's androgynous screen presence is never less than fascinating.

Ultimately revealing his alien form to Mary Lou, who is overwhelmed and terrified, the couple split. Betrayed by confidant, Dr. Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), Newton is imprisoned by the government in a luxury condo. Intermittent cut scenes show a wife and child slowly dying on Newton's home planet. By film's end, his family has perished and Newton is marooned on earth. We cried when Earth nearly killed E.T., but E.T., in contrast, made a friend and found his way home. In Roeg's space opera, Earth becomes the alien's home, but the result is a broken spirit. (Imagine Spielberg making something like that.) The Man Who Fell to Earth is a sci-fi Days of Wine and Roses for the art house crowd. The cinematography by Anthony B. Richmond looks fantastic and Bowie's androgynous screen presence is never less than fascinating. To be sure, Bowie is top notch as Thomas Jerome Newton, but ironically, he was never consulted on the film's soundtrack. That honor went to another rock star, John Phillips, former leader of '60s folk troubadours the Mamas & the Papas, who hand-picked the OST from a selection of pop, classical and original compositions. It's a soundtrack that truly works, in the same way that Kubrick's 2001 soundtrack, as it appears in the film, is superior to the Alex North filmscore that Kubrick scrapped (imagine 2001 without "Also Sprach Zarathustra"). Who knows what Bowie would have chosen for incidental music, but interestingly, 1976 simultaneously gave us the Thin White Duke in Bowie's pseudo-masterpiece Station to Station. The LP's cover further convolutes the issue by featuring the alien in his spacecraft. Many made the obvious association, surprised when no Bowie music appears in the film. A wise choice on Roeg's part, Station to Station just didn't fit the Man Who Fell to Earth premise. We're left instead with an interesting if accidental, marketing ploy.

To be sure, Bowie is top notch as Thomas Jerome Newton, but ironically, he was never consulted on the film's soundtrack. That honor went to another rock star, John Phillips, former leader of '60s folk troubadours the Mamas & the Papas, who hand-picked the OST from a selection of pop, classical and original compositions. It's a soundtrack that truly works, in the same way that Kubrick's 2001 soundtrack, as it appears in the film, is superior to the Alex North filmscore that Kubrick scrapped (imagine 2001 without "Also Sprach Zarathustra"). Who knows what Bowie would have chosen for incidental music, but interestingly, 1976 simultaneously gave us the Thin White Duke in Bowie's pseudo-masterpiece Station to Station. The LP's cover further convolutes the issue by featuring the alien in his spacecraft. Many made the obvious association, surprised when no Bowie music appears in the film. A wise choice on Roeg's part, Station to Station just didn't fit the Man Who Fell to Earth premise. We're left instead with an interesting if accidental, marketing ploy.The New York Times had praise for the film, if not high praise, stating, "There are quite a few science-fiction movies scheduled to come out in the next year or so. We shall be lucky if even one or two are as absorbing and as beautiful as The Man Who Fell to Earth." The Man Who Fell to Earth is poignant, heartbreaking, nostalgic and a great chaser to Bowie's latest ventures (new album out TOMORROW!). Lazarus, Bowie's off-Broadway smash, is the sequel to the alien's dilemma. Tickets for the limited run are sold out. In lieu, find the exquisite Blu-ray of the film and indulge yourself.

Published on April 22, 2018 04:26

April 21, 2018

Drive-in Saturday

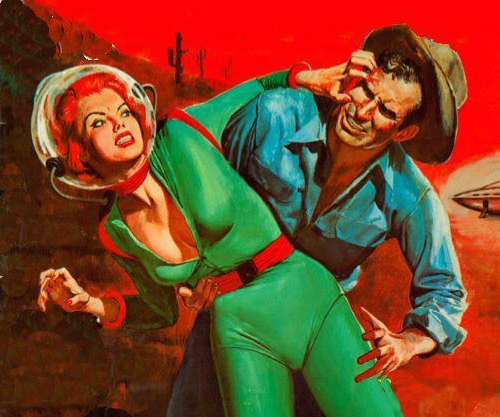

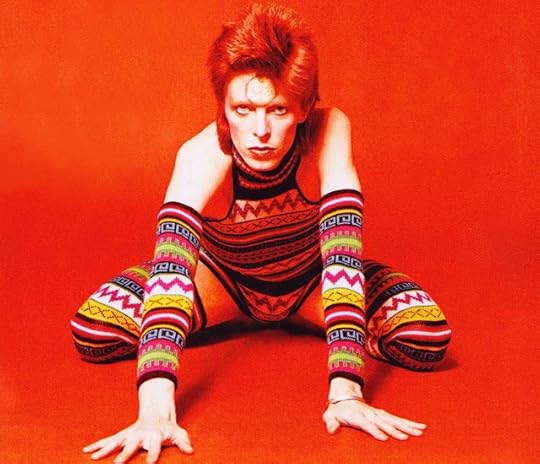

Bowie, throughout his career, would never venture far from the oddities of space and sci-fi. From the Man Who Sold the World to "Oh, You Pretty Things!" there was always a glimpse into another dimension. By Aladdin Sane, the B-Movie 50s had invaded 70s pop with odd misconception. In essence, the style and content of 70s Glam was rooted in rock stars as mutants from the future trying to "blend in" by assembling "authentic" versions of period clothing and getting it wrong. They had 50s shoulder pads and Elvis lamé suits (check), eyeliner and lipstick (so much for blending in); the lyrics drummed up the clichés of 30s gangster flicks, spaceships, motorbikes, aliens and jukeboxes. Indeed a new 50s were invented in the off-kilter 70s. American Graffiti was a box off smash; Elvis, Chuck Berry and Ricky Nelson topped the charts; The Rocky Horror Show opened at the Roxy and Grease on Broadway. The actual 1950s, in all their shadow, were elevated to Eden: a sparklingly innocent contrast to the weariness, grime and open sexuality of the early ’70s.

Bowie, throughout his career, would never venture far from the oddities of space and sci-fi. From the Man Who Sold the World to "Oh, You Pretty Things!" there was always a glimpse into another dimension. By Aladdin Sane, the B-Movie 50s had invaded 70s pop with odd misconception. In essence, the style and content of 70s Glam was rooted in rock stars as mutants from the future trying to "blend in" by assembling "authentic" versions of period clothing and getting it wrong. They had 50s shoulder pads and Elvis lamé suits (check), eyeliner and lipstick (so much for blending in); the lyrics drummed up the clichés of 30s gangster flicks, spaceships, motorbikes, aliens and jukeboxes. Indeed a new 50s were invented in the off-kilter 70s. American Graffiti was a box off smash; Elvis, Chuck Berry and Ricky Nelson topped the charts; The Rocky Horror Show opened at the Roxy and Grease on Broadway. The actual 1950s, in all their shadow, were elevated to Eden: a sparklingly innocent contrast to the weariness, grime and open sexuality of the early ’70s. "Drive-In Saturday" is Bowie's 50s-pop pastiche, though as typical with Bowie there's a twist: "Drive-In Saturday" is a 50s song celebrating the freedoms of the subsequent decade, with Mick Jagger and Twiggy serving as erotic household gods. The premise is that a post-apocalyptic civilization, through fear or reactions from fallout, has forgotten how to have sex, so the kids watch Rolling Stones promos and old films to see how it's done.

"Drive-In Saturday" is Bowie's 50s-pop pastiche, though as typical with Bowie there's a twist: "Drive-In Saturday" is a 50s song celebrating the freedoms of the subsequent decade, with Mick Jagger and Twiggy serving as erotic household gods. The premise is that a post-apocalyptic civilization, through fear or reactions from fallout, has forgotten how to have sex, so the kids watch Rolling Stones promos and old films to see how it's done.It's the first Bowie song to reflect the challenge of Roxy Music, whose first LP (and hit single "Virginia Plain") had come out in the summer of '72. The phased synthesizer lines owe a debt to Brian Eno's squiggles and groans, while Bowie's approach to the material — parodic, subversive, yet done entirely straight-faced — is similar to Bryan Ferry's fractured takes on country-western ("If There Is Something") and torch songs ("Chance Meeting"). We don't often acknowledge Roxy as a Bowie influence, often mistakenly mixing it up.

Bowie wrote "Drive-In Saturday" during a train ride from Seattle to Phoenix in early November 1972. He was unable to sleep and, looking out the window at night while the train was somewhere in the desert, saw a row of nearly 20 enormous silver domes off in the distance, moonlight dancing on their roofs. It intrigued him: what were they? Government post-nuclear-war prep facilities? Secret laboratories?

As with "Oh! You Pretty Things," Bowie"s sci-fi narrative is a cover for a more basic human predicament—how kids, who typically have no idea about sex, have to improvise and fake their way through it, often using film stars and pop music as cues and instructional guides. The idea of groups of teenagers in cars, watching erotic films at a drive-in, as if attending church, is one of Bowie's more melancholy and haunting images. As much as the past can be warped to serve the present's needs, it is equally toxic.

Let me put my arms around your head (dum-do-wah)Gee, it's hot, let's go to bedDon't forget to turn on the lightDon't laugh Babe, it'll be alright (dum-do-wah)

Pour me out another phone (dum-do-wah)I'll ring and see if your friends are homePerhaps the strange ones in the domeCan lend us a book we can read up alone

And try to get it on like once before,When people stared in Jagger's eyes and scored,Like the video films we saw

His name was always BuddyAnd he'd shrug and ask to stayShe'd sigh like Twig the Wonder KidAnd turn her face away.She's uncertain if she likes himBut she knows she really loves himIt's a crash course for the raversIt's a drive-in Saturday.

Published on April 21, 2018 05:43

April 20, 2018

Check Out Calif.

So many of you follow my daily musings on rock music, and while AM prides itself in embracing great music from every era, there's a tendency to focus on the classic era of rock that roughly begins with "Satisfaction" and ends with Prog. Punk starts a new era with The Sex Pistols as a catalyst and culminating with The Clash and Joy Division. With the exception of Weezer and Radiohead, we tend to kinda skip the 90s. The whole emo thing kept us motivated in the naughts and today, thankfully, there are bands like Lord Huron and Rainbow Kitten Surprise. Here's the video I'm obsessed with at the moment.

Over the past three years, AM has had more than half a million unique hits. I've shared with you fictional passages from my novels Jay and the Americans - which is available on Amazon and for your Kindle (read it for free on Kindle Unlimited) - and Miles From Nowhere, a novel about Woodstock, scheduled for publication later this year. Miles takes place nearly 50 years ago with a time frame that begins in July 1969 and ends in October that same year.

The sequel to Miles From Nowhere is my current work, Calif. I'm on page 162. The action takes place from 1969 and throughout the classic rock era. The music within its pages ranges from Cat Stevens to CSN, from Joni Mitchell to the Grateful Dead. Music essentially becomes a character in the novel.

The other day I had this brainstorm to share the writing of Calif., all its bruises and misspellings, as a way for the reader to experience the writing process and my racing thoughts. In it I'll intersperse chapters from the novel as I write and revise them and toss in my whims and frustrations. It's a bit of an experiment that I don't think has been tried before. The tentative cover art for Calif. is the masthead for this new blog based on a line-drawing I created, of which I hope you approve. When something sucks or makes no sense, let me know. I'm thrilled about the first line, by the way, so don't even try it.

This same post is just a click away. When you get there, scroll down for Chapter 1. In the morning I'll post Chapter 2 and keep it up each day until you catch up to where I'm at. If you play along, it will almost be like a Write Your Own Adventure Story!

I love the places that I've never been.

Over the past three years, AM has had more than half a million unique hits. I've shared with you fictional passages from my novels Jay and the Americans - which is available on Amazon and for your Kindle (read it for free on Kindle Unlimited) - and Miles From Nowhere, a novel about Woodstock, scheduled for publication later this year. Miles takes place nearly 50 years ago with a time frame that begins in July 1969 and ends in October that same year.

The sequel to Miles From Nowhere is my current work, Calif. I'm on page 162. The action takes place from 1969 and throughout the classic rock era. The music within its pages ranges from Cat Stevens to CSN, from Joni Mitchell to the Grateful Dead. Music essentially becomes a character in the novel.

The other day I had this brainstorm to share the writing of Calif., all its bruises and misspellings, as a way for the reader to experience the writing process and my racing thoughts. In it I'll intersperse chapters from the novel as I write and revise them and toss in my whims and frustrations. It's a bit of an experiment that I don't think has been tried before. The tentative cover art for Calif. is the masthead for this new blog based on a line-drawing I created, of which I hope you approve. When something sucks or makes no sense, let me know. I'm thrilled about the first line, by the way, so don't even try it.

This same post is just a click away. When you get there, scroll down for Chapter 1. In the morning I'll post Chapter 2 and keep it up each day until you catch up to where I'm at. If you play along, it will almost be like a Write Your Own Adventure Story!

I love the places that I've never been.

Published on April 20, 2018 17:32

Happy 4-20!

Published on April 20, 2018 16:20

I'm on this sci-fi kick... Five Years

Our focus a week or so back was the ten pinnacle moments in rock's history. The last post in the series asked that you, the reader, create your own moment - what moment instilled in you a lifelong love of rock 'n' roll.

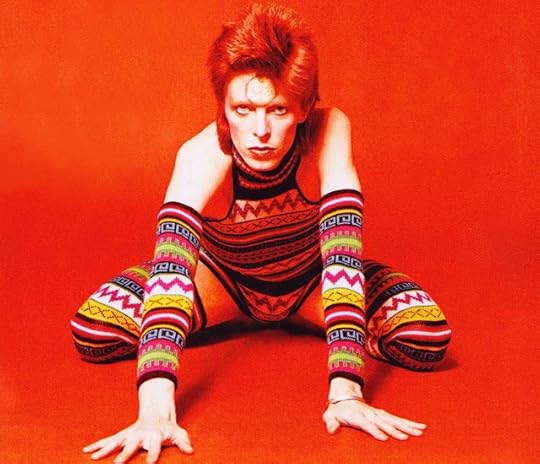

For this writer, Ziggy Stardust was the reason I do this today and why, for me, music is more than incidental. And while there is music that I appreciate more, even Bowie that I appreciate more (Hunky Dory, Diamond Dogs), Ziggy is the catalyst of my rapture. It's difficult to pinpoint why my choice wasn't Sgt. Pepper or The Monkees' Headquarters (or for that matter Bobby Vinton's Greatest Hits when I was five years old); these were the essential albums of my youth. I will venture to say that it was with Ziggy that I became introspective about music; that I began to analyze songs like this:

Of all Bowie’s dystopic and apocalyptic songs, "Five Years" is the most explicitly unsettling. One of the positive criticisms I get in my fiction (Yeah, yeah, Jay and the Americans) is that it's more about what is left unsaid; that it's all about the in-betweens. And so, we don't know why five years is all we've got, only that the planet has received a terminal prognosis and has to get its affairs in order. Ziggy's limited warning keeps his perspective on the street, on the masses who, having got the news, unravel. And yet there's an odd relief in the refrain of the track as if the misery-laden struggles of the mankind are finally over, indeed there is near celebration.

That Jubilation echoes "Memories of a Free Festival" from Space Oddity. While that song is a reflection of a Bowie performance at the Beckenham Arts Lab Free Festival on the day that his father died, there is a dystopian angst associated with it that alter the lyrics in a Five Years kind of way: "The sun machine is coming down and we’re gonna have a party."

In "Five Years," Bowie tapped into a current of pessimism and resignation that would define 1970s Britain in novels, films, music and real life. The Flower Power optimism in the 60stransmogrified into a 70s funk of hippie disillusionment amidst population bomb ecological nihilism - oh, oh, mercy, mercy me...

Bowie's tome mimicked a dystopian poem from 1967, Roger McGough's "At Lunchtime - A Love Story:

The buspeople, and there were many of them,

were shockedandsurprised and amused and annoyed, but when the

word got around that the world was coming to an end at

lunchtime, they put their pride in their pockets with their bustickets and

madelove one with the other.

The poem is set on a bus whose riders, learning the world will end at lunchtime, start having random sex. Watch it, a facsimile anyway, or read it here.

In "Five Years" the world has similarly turned upside-down. A "newsguy," forever emotionless and divorced from the everyday calamities of the world, openly weeps as he announces the impending catastrophe. Upon hearing the news, a policeman kneels to kiss the feet of a priest; we only had, after all, "five years left to cry in."

The inspiration underlying this philosophy had come from a dream Bowie had had in which he witnessed the reversal of the earth's electromagnetic field somewhere around the year 1977. For this reason, David refused to fly anywhere.

Assorted reactions to the impending disaster are observed and related humble narrator. Ziggy relates the plight of those around him: the fat-skinny, fall-short, nobody-somebody black soldier queer people. And yet, like in McGough's poem, the end, being nigh, brings a feeling of great optimism of what could and should be done. Bowie’s narrator makes his way through the desolate streets chronicling whatever he sees and only despairs when he remembers a friend (a former lover?) in an ice-cream shop, a moment of insignificance made unbearably poignant.

Consider the historical context of a world facing the real possibility of a nuclear apocalypse, and the tale of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars begins to sound far less absurd. A suspenseful yet celebratory tone permeates the song, as though he and his band, the Spiders, had resigned themselves to their fate. The implication is that we should too. It's coming, they seem to proclaim, so why not enjoy it?

For this writer, Ziggy Stardust was the reason I do this today and why, for me, music is more than incidental. And while there is music that I appreciate more, even Bowie that I appreciate more (Hunky Dory, Diamond Dogs), Ziggy is the catalyst of my rapture. It's difficult to pinpoint why my choice wasn't Sgt. Pepper or The Monkees' Headquarters (or for that matter Bobby Vinton's Greatest Hits when I was five years old); these were the essential albums of my youth. I will venture to say that it was with Ziggy that I became introspective about music; that I began to analyze songs like this:

Of all Bowie’s dystopic and apocalyptic songs, "Five Years" is the most explicitly unsettling. One of the positive criticisms I get in my fiction (Yeah, yeah, Jay and the Americans) is that it's more about what is left unsaid; that it's all about the in-betweens. And so, we don't know why five years is all we've got, only that the planet has received a terminal prognosis and has to get its affairs in order. Ziggy's limited warning keeps his perspective on the street, on the masses who, having got the news, unravel. And yet there's an odd relief in the refrain of the track as if the misery-laden struggles of the mankind are finally over, indeed there is near celebration.

That Jubilation echoes "Memories of a Free Festival" from Space Oddity. While that song is a reflection of a Bowie performance at the Beckenham Arts Lab Free Festival on the day that his father died, there is a dystopian angst associated with it that alter the lyrics in a Five Years kind of way: "The sun machine is coming down and we’re gonna have a party."

In "Five Years," Bowie tapped into a current of pessimism and resignation that would define 1970s Britain in novels, films, music and real life. The Flower Power optimism in the 60stransmogrified into a 70s funk of hippie disillusionment amidst population bomb ecological nihilism - oh, oh, mercy, mercy me...

Bowie's tome mimicked a dystopian poem from 1967, Roger McGough's "At Lunchtime - A Love Story:

The buspeople, and there were many of them,

were shockedandsurprised and amused and annoyed, but when the

word got around that the world was coming to an end at

lunchtime, they put their pride in their pockets with their bustickets and

madelove one with the other.

The poem is set on a bus whose riders, learning the world will end at lunchtime, start having random sex. Watch it, a facsimile anyway, or read it here.

In "Five Years" the world has similarly turned upside-down. A "newsguy," forever emotionless and divorced from the everyday calamities of the world, openly weeps as he announces the impending catastrophe. Upon hearing the news, a policeman kneels to kiss the feet of a priest; we only had, after all, "five years left to cry in."

The inspiration underlying this philosophy had come from a dream Bowie had had in which he witnessed the reversal of the earth's electromagnetic field somewhere around the year 1977. For this reason, David refused to fly anywhere.

Assorted reactions to the impending disaster are observed and related humble narrator. Ziggy relates the plight of those around him: the fat-skinny, fall-short, nobody-somebody black soldier queer people. And yet, like in McGough's poem, the end, being nigh, brings a feeling of great optimism of what could and should be done. Bowie’s narrator makes his way through the desolate streets chronicling whatever he sees and only despairs when he remembers a friend (a former lover?) in an ice-cream shop, a moment of insignificance made unbearably poignant.

Consider the historical context of a world facing the real possibility of a nuclear apocalypse, and the tale of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars begins to sound far less absurd. A suspenseful yet celebratory tone permeates the song, as though he and his band, the Spiders, had resigned themselves to their fate. The implication is that we should too. It's coming, they seem to proclaim, so why not enjoy it?

Published on April 20, 2018 03:26

April 19, 2018

Bicycle Day

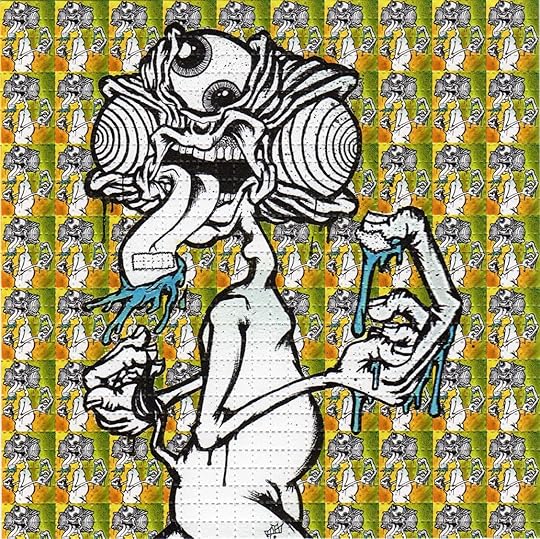

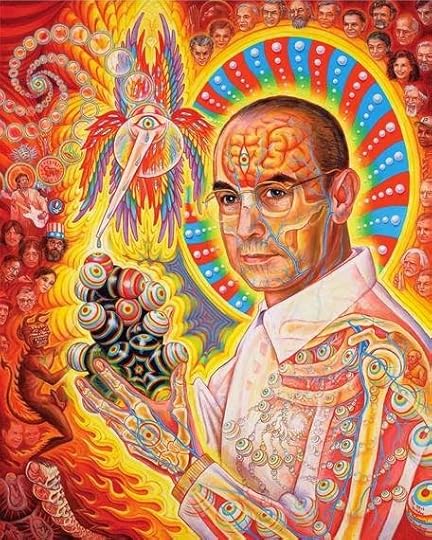

Though LSD was first synthesized in 1938, it was not until 1943 that the first human LSD trip was recorded. Albert Hofmann, a chemist at Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland, had synthesized several derivatives of ergot, a fungus found on rye, in search of a new stimulant pharmaceutical to induce childbirth. After accidentally absorbing a small amount of his 25th derivative during synthesis, Hofmann noticed some strange effects, and felt:

Though LSD was first synthesized in 1938, it was not until 1943 that the first human LSD trip was recorded. Albert Hofmann, a chemist at Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland, had synthesized several derivatives of ergot, a fungus found on rye, in search of a new stimulant pharmaceutical to induce childbirth. After accidentally absorbing a small amount of his 25th derivative during synthesis, Hofmann noticed some strange effects, and felt:"… affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away."

Three days later, on April 19th 1943, Hofmann decided to intentionally ingest 0.25 milligrams of his LSD-25 to confirm the true effects of the new drug. He believed this tiny amount to be a threshold dose, but soon realized he had underestimated the potency of his discovery. Within an hour, Hofmann was experiencing the radical mental perception shifts of humanity’s first acid trip. Since wartime restrictions prevented the use of motor vehicles, he asked his lab assistant to escort him home by bicycle, and hence the date became known as "Bicycle Day." Once home on his couch and assured by his physician that he was not fatally poisoned, Hofmann began to enjoy his "trip":

Three days later, on April 19th 1943, Hofmann decided to intentionally ingest 0.25 milligrams of his LSD-25 to confirm the true effects of the new drug. He believed this tiny amount to be a threshold dose, but soon realized he had underestimated the potency of his discovery. Within an hour, Hofmann was experiencing the radical mental perception shifts of humanity’s first acid trip. Since wartime restrictions prevented the use of motor vehicles, he asked his lab assistant to escort him home by bicycle, and hence the date became known as "Bicycle Day." Once home on his couch and assured by his physician that he was not fatally poisoned, Hofmann began to enjoy his "trip":"… little by little I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colors and plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes. Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged in on me, alternating, variegated, opening and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, exploding in colored fountains, rearranging and hybridizing themselves in constant flux…"

After his bicycle day experience, Hofmann realized he had made a remarkable discovery. He saw incredible potential in LSD for use in psychotherapy, but because of its "intense and introspective nature," he never imagined LSD would have popular appeal. Little did he know that this new drug would go on to become a major catalyst in the development of the 1960s counter-culture, with the Haight-Ashbury as its ground zero. From the 1960s onward, the San Francisco Bay Area came to be known to the growing global psychedelic community as the "acid triangle," where the majority of the world's LSD supply was produced and distributed. [Hofmann often commented that he wished he had never synthesized the chemical compound, and AM by no means endorses the use of illicit substances. This article merely provides a historical context.]

After his bicycle day experience, Hofmann realized he had made a remarkable discovery. He saw incredible potential in LSD for use in psychotherapy, but because of its "intense and introspective nature," he never imagined LSD would have popular appeal. Little did he know that this new drug would go on to become a major catalyst in the development of the 1960s counter-culture, with the Haight-Ashbury as its ground zero. From the 1960s onward, the San Francisco Bay Area came to be known to the growing global psychedelic community as the "acid triangle," where the majority of the world's LSD supply was produced and distributed. [Hofmann often commented that he wished he had never synthesized the chemical compound, and AM by no means endorses the use of illicit substances. This article merely provides a historical context.]

Published on April 19, 2018 16:22

April 19, 1968

1968. I was 7. Based on the dysfunction of my family life (please read Jay and the Americans on Kindle Unlimited for free! – oh, and leave a review on Amazon), my 7th B-Day was overlooked. We were supposed to take the bus to see Dr. Doolittle in Hollywood; instead, my grandmother gave me an LP, Anthony Newley Sings the Songs From Dr. Doolittle and my mother made excuses. Funny, Newley's odd vibrato and phrasing (which I would mimic to my mother's chagrin), would be the basis for my love for Bowie, who I am positive also took a cue from Newley. (I digress, but I guess even 50 years later I still harbor resentment, it seems.)

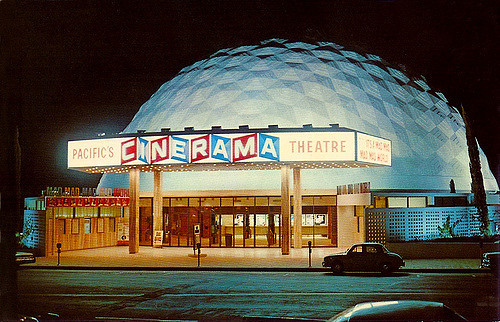

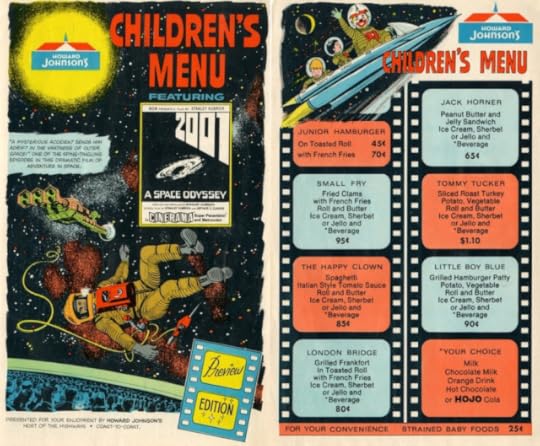

1968. I was 7. Based on the dysfunction of my family life (please read Jay and the Americans on Kindle Unlimited for free! – oh, and leave a review on Amazon), my 7th B-Day was overlooked. We were supposed to take the bus to see Dr. Doolittle in Hollywood; instead, my grandmother gave me an LP, Anthony Newley Sings the Songs From Dr. Doolittle and my mother made excuses. Funny, Newley's odd vibrato and phrasing (which I would mimic to my mother's chagrin), would be the basis for my love for Bowie, who I am positive also took a cue from Newley. (I digress, but I guess even 50 years later I still harbor resentment, it seems.) My estranged father got me nothing, but then, months later during one of my parents' relentless eight-day reconciliations, he took me to the Cinerama Dome to see 2001.The tickets were $6. Cinerama was an early IMAX-like format in specialized theaters. Its screens were taller and considerably wider than normal. 2001 was filmed in Super Panavision with an exclusive surround sound. He got me the souvenir program that mimicked the widescreen format. I'd only learned about it because, when they were together, we always ate at the Howard Johnson's on Sundays; my father enjoyed the all you can eat fried clam strips. The children's menu this go-round was the 2001 edition.

My estranged father got me nothing, but then, months later during one of my parents' relentless eight-day reconciliations, he took me to the Cinerama Dome to see 2001.The tickets were $6. Cinerama was an early IMAX-like format in specialized theaters. Its screens were taller and considerably wider than normal. 2001 was filmed in Super Panavision with an exclusive surround sound. He got me the souvenir program that mimicked the widescreen format. I'd only learned about it because, when they were together, we always ate at the Howard Johnson's on Sundays; my father enjoyed the all you can eat fried clam strips. The children's menu this go-round was the 2001 edition.Before then, science fiction cinema was largely limited to B-Movies and the occasional sci-fi epic like This Island Earth or the spectacular Forbidden Planet, a spacy version of Shakespeare's The Tempest. Those early science fiction features were big hits; still, science fiction was for kids. Then came Kubrick, Clarke and 2001.

The Cinerama Dome was like a spaceship; the theater drenched in gold, the screen wrapping 180⁰. It couldn't have been a better day. (Screw Dr. Doolittle.) The theater went dark, the gold velvet screen still closed, and the strains of Ligeti’s Atmospheres slowly built. The curtain opened and then, the most dramatic opening sequence in film, "Also Sprach Zarathustra" in the background, and I could have wet myself. I'm sure for the first 25 minutes or so, you know, the monkey thing, my father had Rock Hudson's impression, only buying in with Dr. Heywood Floyd’s arrival on the space station. By intermission, my father, too, was hooked. He gasped as the curtains closed and said, "HAL was reading their lips." I was 7; I don’t know that I really got the connection.

I had no idea what I was seeing but knew it was very different. No ray guns or bug-eyed monsters? It was a strange new world by the time people built spaceships—apes became people and we conquered the environment with the aid of a big black box, but at what cost? And by intermission, the machinery people built to conquer that environment was ready to fight back! Woah, that's a lot for a 7-year old to process! As a child who grew up with Gemini missions and space walks (I had a poster of Ed White on my wall), 2001 was up there with Tomorrowland. 2001 has been a part of my life now, for 50 years; though I now watch it snuggled up on the couch in Blu Ray, and with the advent of the internet's secrets, I'll occasionally sync up Pink Floyd's Echoes and the Star Gate sequence; high, of course.

I had no idea what I was seeing but knew it was very different. No ray guns or bug-eyed monsters? It was a strange new world by the time people built spaceships—apes became people and we conquered the environment with the aid of a big black box, but at what cost? And by intermission, the machinery people built to conquer that environment was ready to fight back! Woah, that's a lot for a 7-year old to process! As a child who grew up with Gemini missions and space walks (I had a poster of Ed White on my wall), 2001 was up there with Tomorrowland. 2001 has been a part of my life now, for 50 years; though I now watch it snuggled up on the couch in Blu Ray, and with the advent of the internet's secrets, I'll occasionally sync up Pink Floyd's Echoes and the Star Gate sequence; high, of course.We all know that when you cue up The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon (1973) and play them together? You get something magical. Or, to be more precise, you get Dark Side of the Rainbow. One could believe that Floyd wrote Dark Side as a stealth Wizard of Oz soundtrack - something the band firmly denies. But bury one rumor, and another emerges. Two years before producing Meddle, featuring the 23-minute 'Echoes,' Pink Floyd worked on the More film soundtrack, utilizing film synchronization equipment. From there the rumors blossomed, with Roger Waters being misquoted as saying the band was offered the opportunity to provide the soundtrack (they had, in fact, turned down an offer to feature the "Atom Heart Mother" suite in Kubrick's Clockwork Orange). Whether or not the rumors have validity, there is an undeniable beauty when watching the combination of Kubrick's intricate multiverse coupled with the spacey psychedelia of Pink Floyd. The mashup is vibrant and unified. The emotional tone of the music and the images work in harmony; the movie and the music feed into and expand the sense of mystery and unknowability that each explores independently. Go ahead, you know you want to.

Published on April 19, 2018 03:35

April 18, 2018

Howard Johnson's on the Space Station - 2001

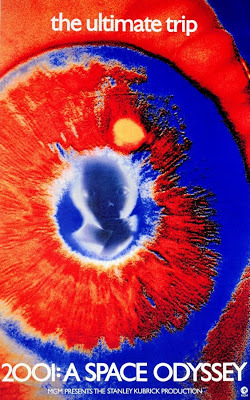

Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece, of course - and one of the films that stands shoulder to shoulder with Citizen Kane, Vertigo, On the Waterfront and Casablanca - 2001, A Space Odyssey was released on April 3, 1968, 50 years ago. Like the anniversary of Sgt. Pepper and the golden era of rock music, the release of 2001 changed filmmaking forever. Despite the fanfare and the number of best lists the film receives, the movie isn't for everyone. Keep in mind, there isn't a single line in the film until a stewardess speaks aboard Dr. Heywood Floyd's shuttlecraft at the 25:38 mark (unless you count the grunts and growls of the australopithecines), and there is no dialogue for the final 23 minutes of the Star Gate sequence. It is reported that 241 people walked out of the initial viewing including actor Rock Hudson who said, "Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?" Interest in the film began to grow when inspired teens and hippies alike realized that LSD and the Star Gate went hand-in-hand. MGM even had designs on killing the screenings and cutting their losses. Since then, of course, the film has become the most iconic of space operas and the one film that explains everything in the universe (Terrence Malick's Tree of Life tries as well, but not as successfully).

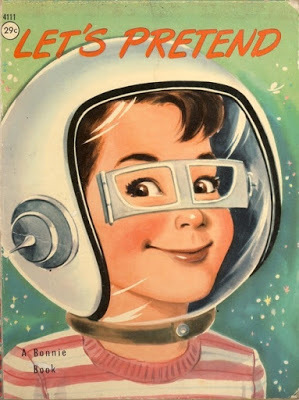

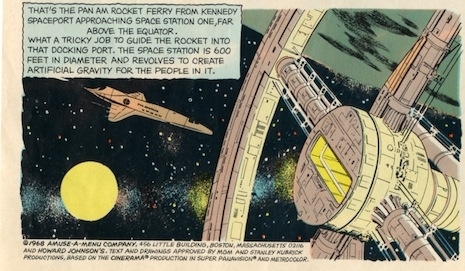

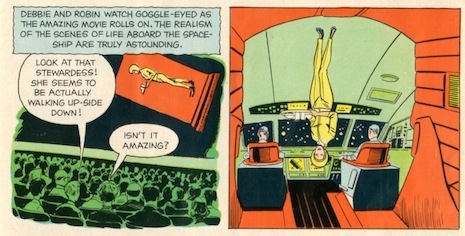

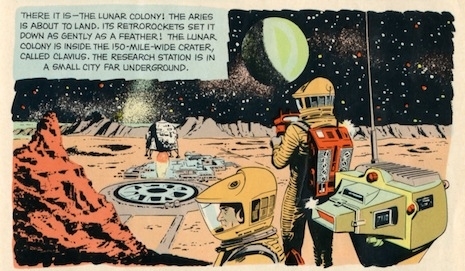

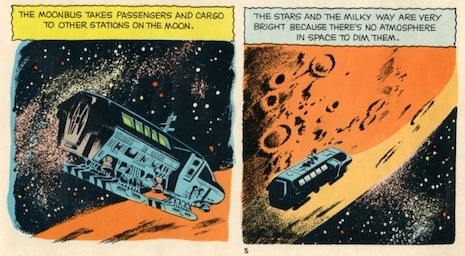

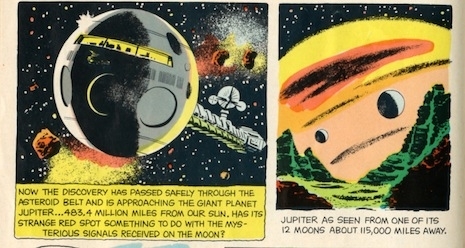

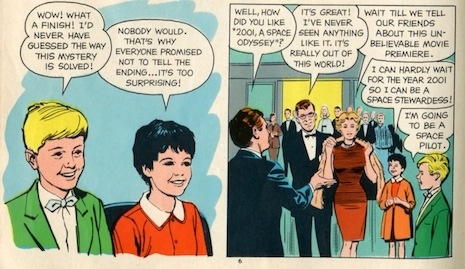

Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece, of course - and one of the films that stands shoulder to shoulder with Citizen Kane, Vertigo, On the Waterfront and Casablanca - 2001, A Space Odyssey was released on April 3, 1968, 50 years ago. Like the anniversary of Sgt. Pepper and the golden era of rock music, the release of 2001 changed filmmaking forever. Despite the fanfare and the number of best lists the film receives, the movie isn't for everyone. Keep in mind, there isn't a single line in the film until a stewardess speaks aboard Dr. Heywood Floyd's shuttlecraft at the 25:38 mark (unless you count the grunts and growls of the australopithecines), and there is no dialogue for the final 23 minutes of the Star Gate sequence. It is reported that 241 people walked out of the initial viewing including actor Rock Hudson who said, "Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?" Interest in the film began to grow when inspired teens and hippies alike realized that LSD and the Star Gate went hand-in-hand. MGM even had designs on killing the screenings and cutting their losses. Since then, of course, the film has become the most iconic of space operas and the one film that explains everything in the universe (Terrence Malick's Tree of Life tries as well, but not as successfully). Only the most observant of Kubrick apostles will remember the Howard Johnson's reference in the landmark film, but it's right there at the 30-minute mark. Dr. Heywood Floyd, played with purposeful blandness by William Sylvester, finds himself in a veritable barrage of product placement following the legendary Johann Strauss "Blue Danube" slam cut from the apes' bone-toss to the graceful, silent spacecraft (one of the most dynamic pieces of filmmaking ever conceived - and certainly the greatest time shift). Dr. Floyd is flying on a Pan Am shuttle, and on the space station, walks through a Hilton hotel lobby, places a call to his wife and daughter using a Bell Picturephone (and pays for the call with his American Express), and yes, walks by the "Howard Johnson's Earthlight Room."As the beneficiary of a truly special promotional opportunity, Howard Johnson's did their part, releasing a combined comic book/children's menu depicting a visit to the premiere of the movie by two youngsters: "Debbie and Robin Go to a Movie Premiere with Their Parents." Neat-O! The comic focuses on the Tommorowland feel conveyed in the middle parts of the movie, glosses over the ending and ignores one of the film's most important aspects outright (the apes of the opening sequence). But note that the comic's synopsis does not gloss over Hal's murders. 60s kids were good with murder.

Only the most observant of Kubrick apostles will remember the Howard Johnson's reference in the landmark film, but it's right there at the 30-minute mark. Dr. Heywood Floyd, played with purposeful blandness by William Sylvester, finds himself in a veritable barrage of product placement following the legendary Johann Strauss "Blue Danube" slam cut from the apes' bone-toss to the graceful, silent spacecraft (one of the most dynamic pieces of filmmaking ever conceived - and certainly the greatest time shift). Dr. Floyd is flying on a Pan Am shuttle, and on the space station, walks through a Hilton hotel lobby, places a call to his wife and daughter using a Bell Picturephone (and pays for the call with his American Express), and yes, walks by the "Howard Johnson's Earthlight Room."As the beneficiary of a truly special promotional opportunity, Howard Johnson's did their part, releasing a combined comic book/children's menu depicting a visit to the premiere of the movie by two youngsters: "Debbie and Robin Go to a Movie Premiere with Their Parents." Neat-O! The comic focuses on the Tommorowland feel conveyed in the middle parts of the movie, glosses over the ending and ignores one of the film's most important aspects outright (the apes of the opening sequence). But note that the comic's synopsis does not gloss over Hal's murders. 60s kids were good with murder.

Published on April 18, 2018 03:39

April 17, 2018

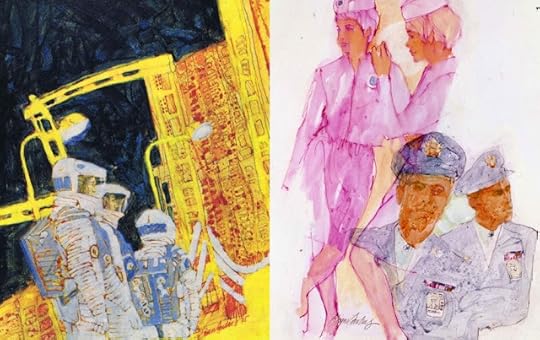

1966 Concept Paintings, 2001, A Space Odyssey

Published on April 17, 2018 17:37

2001, A Space Odyssey - Kubrick and North

A Temp Track is a piece of music used while a film is in production. It serves as a bit of a placeholder; think "Scrambled Egg," the words McCartney used when writing what would become "Yesterday." A film score's composer is more likely to write the score once the initial cinematography is complete. For 2001, A Space Odyssey, the Temp Score was essentially what we find today on the LP version of the iconic film. Certainly, the strains of The Blue Danube, György Ligeti's Lux Aeterna, and the Gayane Ballet are as familiar to the film's fans as John Williams' work is to Star Wars, but nowhere is an opening scene's music more integral to a film than Also Sprach Zarathustra. Who is not enamored as Dr. Floyd's shuttlecraft delicately dances around the spinning wheeled space station to the Strauss waltz.

Indeed, cinematic history would have been very different had Stanley Kubrick gone ahead with his original composer Alex North’s score for 2001. With all the admiration for the film's themes and technical audacity, its musical scoring tends to come last on the list, yet Kubrick gave just as much thought to this aspect of his film. In March 1966, MGM became concerned about 2001's progress and Kubrick put together a showreel of footage to the ad hoc temp score of classical recordings. The studio bosses were delighted with the results and Kubrick brilliantly abandoned North's score.

That said, North's score is a brilliant 40-minute film score masterwork and is now available from Varese Sarabande. While Stanley Kubrick held Alex North in high regard, but ultimately chose to take his film in a different musical direction, and while that may have been disappointing for Alex, it was a decision that helped make 2001 an ageless experience, grounded in the work of Strauss, A. Khatchaturian, and Gyorgy Ligeti. Alex North, however as his long and storied career demonstrates, is a composer of the highest quality regard and didn't take the news well. North had no idea that his score had been tossed until he showed up for a screening of the film. Alex believed, up until his dying day, that his score was the ideal accompaniment to Kubrick's images and that his work had been grossly undervalued.

We can only look at the pieces in hindsight, however. To this writer, here on the 50th anniversary of the film, there is no doubt the power and elegance of the film and its quintessential score. Watch the video with North's score taking the place of Zarathustra, and there is no comparison. But listen instead to North's version and discover a film score that rivals those of Tiompkin, Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Newman.

Published on April 17, 2018 13:41