R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 74

May 7, 2018

400 Years Ago - A Literary Lesson

If you remember your salad days, you're quoting Shakespeare; if something of yours has vanished into thin air, then you're quoting Shakespeare; if you refuse to budge an inch or play fast and loose, if you've been tongue-tied, a tower of strength, hoodwinked or in a pickle, then it's a foregone conclusion that you are (as good luck would have it) quoting Shakespeare. Indeed, even if you send me packing and wish I were dead, by Jove, O Lord, tut, tut and for goodness' sake, it is all one to me, for you are quoting Shakespeare. And you're not alone. 400 Years after Shakespeare's death (April 23, 1616) we quote directly, we paraphrase, we use the Bard's words out of context.

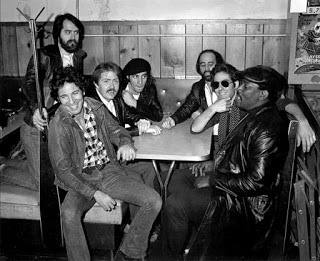

If you remember your salad days, you're quoting Shakespeare; if something of yours has vanished into thin air, then you're quoting Shakespeare; if you refuse to budge an inch or play fast and loose, if you've been tongue-tied, a tower of strength, hoodwinked or in a pickle, then it's a foregone conclusion that you are (as good luck would have it) quoting Shakespeare. Indeed, even if you send me packing and wish I were dead, by Jove, O Lord, tut, tut and for goodness' sake, it is all one to me, for you are quoting Shakespeare. And you're not alone. 400 Years after Shakespeare's death (April 23, 1616) we quote directly, we paraphrase, we use the Bard's words out of context. In 1965, Dylan took on Shakespeare with "Desolation Row:" "And in comes Romeo, he's moaning 'You belong to me I believe.'/ Ophelia, she's 'neath the window, for her I feel so afraid." Although the specific narrative doesn’t necessarily follow Shake's (mixing it up a bit), a plethora of characters that paint Dylan’s urban landscape are plucked straight from Liam (you know, we're on a familiar basis). Similarly, The Band’s "Ophelia," despite its bouncy, syncopated rhythm, has lyrics nearly as dark as those of Hamlet, drawing directly from the madness that Ophelia suffers, to portray, if melodramatically, a disconnected, out of touch young woman. Sting borrows directly from Shakespeare's Sonnet 130: "My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun," he sings in a torchy ballad. The album as well was titled Nothing Like the Sun. Morrissey flirted with the Bard (Morrissey liked to flirt with British Gods, most notably in "Cemet'ry Gates") in "You've Got Everything Now," which opens with a slight variation on a line from Much Ado About Nothing: "As merry as the days were long."

Sigh No More is the title of Mumford and Sons hugely popularly first album as well as the first song on that album. This too alludes to Much Ado About Nothing: "Serve God love me and mend, For man is a giddy thing, and One foot in sea and one on shore." Macbeth plays a role in "Roll Away Your Stone:" "Stars hide your fires/And these here are my desire" can be compared of course to "Stars, hide your fires,/Let not light see my black and deep desires."

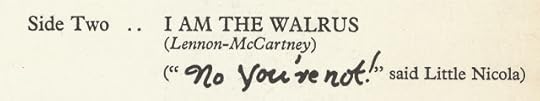

Sigh No More is the title of Mumford and Sons hugely popularly first album as well as the first song on that album. This too alludes to Much Ado About Nothing: "Serve God love me and mend, For man is a giddy thing, and One foot in sea and one on shore." Macbeth plays a role in "Roll Away Your Stone:" "Stars hide your fires/And these here are my desire" can be compared of course to "Stars, hide your fires,/Let not light see my black and deep desires."But it's not only through the lyrics that we recall our fave Elizabethan rock star. The Beatles so memorably plucked out a BBC soundbite from King Lear for "I Am the Walrus." With their all-encompassing cultural reach, you might think the Fab Four would've had more Shakespeare in their canon, but there was only this one, and it was a happy accident. While making a sound collage for "Walrus's" fade-out, Neil Aspinall switched on a radio in the studio and caught a broadcast of Lear. "Oh untimely death..." is one of the lines that pokes out, from Oswald's death scene. The complete lines run (thanks to Wikipedia, I am including the song timings): Oswald: (3:52) Slave, thou hast slain me. Villain, take my purse./ If ever thou wilt thrive,(4:02) bury my body,/ And give the (4:05) letters which thou find'st about me/ To (4:08) Edmund, Earl of Gloucester; (4:10) seek him out/ Upon the British party. O, (4:14) untimely Death!/ Edgar: (4:23) I know thee well: a (4:25) serviceable villain;/ As duteous to the (4:27) vices of thy mistress/ As badness would desire. Gloucester: What, is he dead?/ Edgar: (4:31) Sit you down father, rest you."

"Pack and get dressed/ Before your father hears us/ Before all hell breaks loose/ Breathe, keep breathing/ Don’t lose your nerve/ Breathe, keep breathing/ I can't do this alone"

Radiohead's "Exit Music" was inspired of course by Baz Luhrman's contemporary film remake, Romeo + Juliet, and Thom Torke wrote "Exit Music" for the closing credits. The result is a beautiful track that could end nearly any film. "I saw the Zeffirelli version when I was 13 and I cried my eyes out, because I couldn’t understand why, the morning after they shagged, they didn't just run away," Yorke has been quoted about the song. "The song is written for two people who should run away before all the bad stuff starts. A personal song." My Chemical Romance’s song "The Sharpest Lives" contains (yet another) reference to Romeo and Juliet : "Juliet loves the beat and the lust it commands/ drop the dagger and lather the blood on your hands, Romeo."

Radiohead's "Exit Music" was inspired of course by Baz Luhrman's contemporary film remake, Romeo + Juliet, and Thom Torke wrote "Exit Music" for the closing credits. The result is a beautiful track that could end nearly any film. "I saw the Zeffirelli version when I was 13 and I cried my eyes out, because I couldn’t understand why, the morning after they shagged, they didn't just run away," Yorke has been quoted about the song. "The song is written for two people who should run away before all the bad stuff starts. A personal song." My Chemical Romance’s song "The Sharpest Lives" contains (yet another) reference to Romeo and Juliet : "Juliet loves the beat and the lust it commands/ drop the dagger and lather the blood on your hands, Romeo."But everyone of course hates Shakespeare.

Published on May 07, 2018 05:48

Ode to Billie Joe - Bobby Gentry

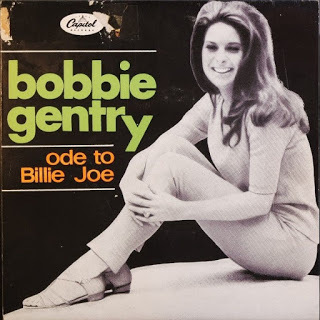

I've mentioned many times AM's obsession with finding some kind of connection between one post and the next, whether that connection is 1967 or literature or people Joni Mitchell slept with. I mentioned getting a 1961 Magnavox Collaro turntable, and so now every extra dollar goes towards vinyl. I suddenly have my own little connections that may not be as readily apparent as the ones you're used to. The other day, for instance, for $2.99 each, I got The Mason William Phonograph Record, a favorite when I was a kid ("Classical Gas"), Cat Stevens' Buddha and the Chocolate Box and Bobbie Gentry's Ode to Billie Joe, if only for the sentimental value. Turns out, the title track is classic Southern-American Gothic poetry that achieves its poetic value through subordination of event to situation. "Ode to Billie Joe" seems a simple narration of events, journalism-style: the narrator and Billie Joe throwing something off the bridge, Billie Joe jumping off the bridge, a pretty vivid picture. Yet the listener doesn't know what the pair are throwing off the bridge and we don't know why Billie Joe killed hisseff. What is revealed with utter clarity is the narrator's situation: she is spoken to and spoken about within the poem, but she herself is never allowed to speak; she is closely monitored (told to wipe her feet, interrogated for not eating, observed and reported on) but not recognized at all; she is kept in place by society, but is afforded no place in that society; on and on. In Aristotelian/English teacher terms, Bobbie Gentry's hit inverts the tragic focus on mythos for a lyric focus on ethos. It takes to heart Emily Dickinson's advice to "tell all the truth but tell it slant."

I've mentioned many times AM's obsession with finding some kind of connection between one post and the next, whether that connection is 1967 or literature or people Joni Mitchell slept with. I mentioned getting a 1961 Magnavox Collaro turntable, and so now every extra dollar goes towards vinyl. I suddenly have my own little connections that may not be as readily apparent as the ones you're used to. The other day, for instance, for $2.99 each, I got The Mason William Phonograph Record, a favorite when I was a kid ("Classical Gas"), Cat Stevens' Buddha and the Chocolate Box and Bobbie Gentry's Ode to Billie Joe, if only for the sentimental value. Turns out, the title track is classic Southern-American Gothic poetry that achieves its poetic value through subordination of event to situation. "Ode to Billie Joe" seems a simple narration of events, journalism-style: the narrator and Billie Joe throwing something off the bridge, Billie Joe jumping off the bridge, a pretty vivid picture. Yet the listener doesn't know what the pair are throwing off the bridge and we don't know why Billie Joe killed hisseff. What is revealed with utter clarity is the narrator's situation: she is spoken to and spoken about within the poem, but she herself is never allowed to speak; she is closely monitored (told to wipe her feet, interrogated for not eating, observed and reported on) but not recognized at all; she is kept in place by society, but is afforded no place in that society; on and on. In Aristotelian/English teacher terms, Bobbie Gentry's hit inverts the tragic focus on mythos for a lyric focus on ethos. It takes to heart Emily Dickinson's advice to "tell all the truth but tell it slant." Gentry has said that she doesn't know what Billy Jo (the spelling in the lyrics) and the girl threw off the Tallahatchie Bridge, which seems likely; it's also not clear, for example, that Margaret Mitchell knew any more about the future of Rhett and Scarlett than her readers. "Tomorrow is another day" tells us only that Scarlett isn't defeated and that all things are possible. There's a bit of Schrodinger's cat in there too. Gentry's allusions/illusions leave a number of possibilities open, none of them definitive. She has said that the lyrics focus on the cold, nonchalant way the girl's family discusses Billy Joe's suicide, and with this, Gentry captures the essence of small-town life and gossip. With the Vietnam War and anti-war protests dominating the news, the family turns its attention to something local that each of them knows something about. Papa says Billy Joe "never had a lick of sense," Brother says he talked to Billy Joe after church last Sunday night and ran into him at the sawmill, and Mama mentions that the new preacher saw a girl who looked a lot like her daughter with Billy Joe throwing something off the bridge. All of these references, and the casual ones to what seems to be a tragic suicide, are interspersed with "pass the biscuits, please" and "I'll have another piece of apple pie." Cheesy? No way; that’s poetry thar! – Sincerely, B. Gentry.

Gentry has said that she doesn't know what Billy Jo (the spelling in the lyrics) and the girl threw off the Tallahatchie Bridge, which seems likely; it's also not clear, for example, that Margaret Mitchell knew any more about the future of Rhett and Scarlett than her readers. "Tomorrow is another day" tells us only that Scarlett isn't defeated and that all things are possible. There's a bit of Schrodinger's cat in there too. Gentry's allusions/illusions leave a number of possibilities open, none of them definitive. She has said that the lyrics focus on the cold, nonchalant way the girl's family discusses Billy Joe's suicide, and with this, Gentry captures the essence of small-town life and gossip. With the Vietnam War and anti-war protests dominating the news, the family turns its attention to something local that each of them knows something about. Papa says Billy Joe "never had a lick of sense," Brother says he talked to Billy Joe after church last Sunday night and ran into him at the sawmill, and Mama mentions that the new preacher saw a girl who looked a lot like her daughter with Billy Joe throwing something off the bridge. All of these references, and the casual ones to what seems to be a tragic suicide, are interspersed with "pass the biscuits, please" and "I'll have another piece of apple pie." Cheesy? No way; that’s poetry thar! – Sincerely, B. Gentry. Gentry's lyrics unveil the underlying story. Brother says, "You know, it don’t seem right," indicating that Billy Joe didn't seem suicidal. Now there are two mysteries: What did he (and the girl) throw off the bridge, and why did he suddenly kill himself? Are the two events related? How? As well, the girl's identity does not seem to be part of the mystery. She is quiet during the conversation and doesn't even comment when Brother mentions a prank played on her, meanwhile her mother notices her lack of appetite. If she is the girl who was with Billie Joe (and come on, she is), she keeps it to herself and doesn't want anyone to know . Her family, consciously or unconsciously, adds to her feelings of grief and possibly her guilt.

Gentry's lyrics unveil the underlying story. Brother says, "You know, it don’t seem right," indicating that Billy Joe didn't seem suicidal. Now there are two mysteries: What did he (and the girl) throw off the bridge, and why did he suddenly kill himself? Are the two events related? How? As well, the girl's identity does not seem to be part of the mystery. She is quiet during the conversation and doesn't even comment when Brother mentions a prank played on her, meanwhile her mother notices her lack of appetite. If she is the girl who was with Billie Joe (and come on, she is), she keeps it to herself and doesn't want anyone to know . Her family, consciously or unconsciously, adds to her feelings of grief and possibly her guilt.What makes "Ode to Billie Joe" poetic is the spare but effective way in which the story is told. Nothing is stated, leaving much to be inferred. By the end, through only a few details, the listener (or reader) can see how the family might represent the decline of small-town farming America. With the father dead, Brother abandons the farm for his wife and their new store in town, and the mother and daughter are left with their grief for their respective losses. Gentry doesn't describe Choctaw Ridge or the Tallahatchie Bridge, but we don't need to know what they look like for them to serve as the song's emotional center. The rhythm of the names, combined with their repetition, sears them into our memories. Gentry once said the song was really about indifference, and was, as she described it "A study in unconscious cruelty." She went on to say, "Those questions are of secondary importance in my mind. The story of Billie Joe has two more interesting underlying themes. First, the illustration of a group of people's reactions to the life and death of Billie Joe, and its subsequent effect on their lives, is made. Second, the obvious gap between the girl and her mother is shown, when both women experience a common loss (first, Billie Joe and, later, Papa), and yet Mama and the girl are unable to recognize their mutual loss or share their grief."

"Ode to Billie Joe" was Gentry's debut single, recorded in 40 minutes on July 10 1967. Gentry accompanied herself on acoustic guitar and strings were added later. The original version of the song was 7 minutes, cut down to 4 and released it as a single. The song sold over 3 million copies and Gentry won 3 Grammy awards, including Best Artist, the first country artist to win the award. And for me, pretty good score for $2.99.

It was the third of June, another sleepy, dusty Delta day.

I was out choppin' cotton and my brother was balin' hay.

And at dinner time we stopped and we walked back to the house to eat.

And mama hollered at the back door, "Y'all remember to wipe your feet."

And then she said she got some news this mornin' from Choctaw Ridge

Today Billy Joe MacAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge.Papa said to mama as he passed around the black-eyed peas,

"Well, Billy Joe never had a lick of sense, pass the biscuits, please."

"There's five more acres in the lower forty I've got to plow."

Mama said it was shame about Billy Joe, anyhow.

Seems like nothin' ever comes to no good up on Choctaw Ridge,

And now Billy Joe MacAllister's jumped off the Tallahatchie BridgeAnd brother said he recollected when he and Tom and Billy Joe

Put a frog down my back at the Carroll County picture show.

And wasn't I talkin' to him after church last Sunday night?

"I'll have another piece of apple pie, you know it don't seem right.

I saw him at the sawmill yesterday on Choctaw Ridge,

And now you tell me Billy Joe's jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge."Mama said to me "Child, what's happened to your appetite?

I've been cookin' all morning and you haven't touched a single bite.

That nice young preacher, Brother Taylor, dropped by today,

Said he'd be pleased to have dinner on Sunday. Oh, by the way,

He said he saw a girl that looked a lot like you up on Choctaw Ridge

And she and Billy Joe was throwing somethin' off the Tallahatchie Bridge."

A year has come 'n' gone since we heard the news 'bout Billy Joe.

Brother married Becky Thompson, they bought a store in Tupelo.

There was a virus going 'round, papa caught it and he died last spring,

And now mama doesn't seem to wanna do much of anything.

And me, I spend a lot of time pickin' flowers up on Choctaw Ridge,

And drop them into the muddy water off the Tallahatchie Bridge.

Published on May 07, 2018 04:09

May 6, 2018

Eleanor Rigby

Despite the controversy regarding his Axis support and subsequent subversive broadcasts, Ezra Pound remains one of the most important figures in American and World Poetry. Indeed "Prufrock" and The Waste Land, Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man wouldn't exist without Pound, who, it was noted by Hemingway, only spent a fifth of his energies on his own writing; the rest devoted to writers, from Eliot to Robert Frost to artist Wyndham Lewis. Pound indeed would have been a champion of The Beatles. The poet is said to have "smiled lightly" when he first heard "ER" (Pound's smile came when introduced to The Beatles by Allen Ginsberg); of course he did: two lonely people, living in a church community, cannot connect or associated with their surroundings and those who inhabit them and end up living their lives alone and apart, one burying the other, a grim irony that would be funny if it weren't dreadful. Eleanor dies in church, buried along with her name. Even Ozymandias, despite the "lone and level sands stretch(ing) far away," has his name. In Eleanor Rigby's death we see the death of hope itself, the ultimate tragedy.

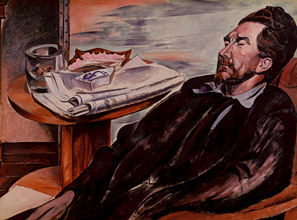

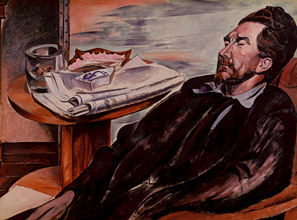

Despite the controversy regarding his Axis support and subsequent subversive broadcasts, Ezra Pound remains one of the most important figures in American and World Poetry. Indeed "Prufrock" and The Waste Land, Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man wouldn't exist without Pound, who, it was noted by Hemingway, only spent a fifth of his energies on his own writing; the rest devoted to writers, from Eliot to Robert Frost to artist Wyndham Lewis. Pound indeed would have been a champion of The Beatles. The poet is said to have "smiled lightly" when he first heard "ER" (Pound's smile came when introduced to The Beatles by Allen Ginsberg); of course he did: two lonely people, living in a church community, cannot connect or associated with their surroundings and those who inhabit them and end up living their lives alone and apart, one burying the other, a grim irony that would be funny if it weren't dreadful. Eleanor dies in church, buried along with her name. Even Ozymandias, despite the "lone and level sands stretch(ing) far away," has his name. In Eleanor Rigby's death we see the death of hope itself, the ultimate tragedy. Ezra Pound by Wyndham LewisThe story is typical of Paul with its two functioning, unrelated characters brought into ironic proximity in the final scene, as though it were a novel by Bronte, and a precursor to "Penny Lane." One can't help but sense the influence of John upon Paul's particular choices of detailed imagery and idiosyncratic turns of phrase. The song avoids sentimentality by keeping its distance from the subject, presenting the action like a film script: "Look at him working," and uses various tense to imply shift in perspective: Eleanor Rigby "died in the church" (past tense), while in the same scene, Father MacKenzie is "wiping the dirt from his hands" (present tense).

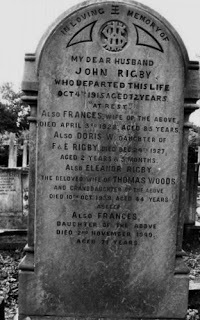

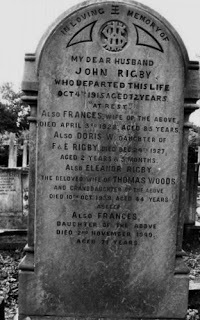

Ezra Pound by Wyndham LewisThe story is typical of Paul with its two functioning, unrelated characters brought into ironic proximity in the final scene, as though it were a novel by Bronte, and a precursor to "Penny Lane." One can't help but sense the influence of John upon Paul's particular choices of detailed imagery and idiosyncratic turns of phrase. The song avoids sentimentality by keeping its distance from the subject, presenting the action like a film script: "Look at him working," and uses various tense to imply shift in perspective: Eleanor Rigby "died in the church" (past tense), while in the same scene, Father MacKenzie is "wiping the dirt from his hands" (present tense).When Paul McCartney first wrote "ER" he had the music worked out before the lyrics, as he often did ("Yesterday," remember, started out as "Scrambled Eggs"). Paul often used placeholder lyrics that he'd subsequently abandon. To be specific, the original version began, "Ola Na Tungee/ Blowing his mind in the dark/ With a pipe full of clay/ No one can say." In other words, a guy with a quasi-Hindu name getting high, a far cry from the English Village equivalent to Desolation Street. Paul later picked the name Rigby from a wine and spirits shop in Bristol, and the name Eleanor in reference to the British actress, Eleanor Bron, who appeared in Help! The priest was originally named Father McCartney, but John's friend Pete Shotton warned that people would think he was talking about his own father. George reportedly contributed the line "Ah look at all the lonely people," while Ringo contributed the idea of having Father McKenzie darning his socks in the night. There are of course many course one may take analyzing the iconic single, and a day's worth of interesting research is in store for those who try. Ultimately, despite the subjective nature of the lyrics, Eleanor Rigby exists, at least in name; indeed at the cruelly young age of 44, Eleanor Rigby died in the same house where she had been born, was interred in the graveyard of St Peter's Church in Liverpool, and had her name added prominently on an increasingly crowded headstone. The story, its evolution and its ties to history are fascinating.

In 1964, the Beatles held the top 5 positions on Billboard's Hot 100. On April 4th of that year, "Can't Buy Me Love" was No. 1, followed by "Twist and Shout," "She Loves You," "I Wanna Hold Your Hand" and "Please Please Me." It was an accomplishment which can never be equaled, but from August 1966 through the end of 1967, the Beatles were at the top of the chart in a myriad of categories. In August '66, Rubber Soul was the No. 1 album, and would remain so for eight weeks, with the double A sided "Yellow Submarine/Elenor Rigby" at the top of the singles charts for four weeks. Between January 1967 and the end of the year, the Beatles remained at the top of the charts with the release of three additional LPs, Revolver and Sgt. Pepper, followed by the EP release worldwide and the full length LP as released by Capitol in the U.S. of Magical Mystery Tour. The singles release during this period were: "Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields" (which made it only to No. 2, based on The Monkees' "I'm a Believer"); "All You Need is Love" and "Hello Goodbye." Imagine four unparalleled LPs with two solid No. 1 singles in a little over a year, all from the same band!

Published on May 06, 2018 05:14

Rock Music as Poetry - Part 3 - Eleanor Rigby

Despite the controversy regarding his Axis support and subsequent subversive broadcasts, Ezra Pound remains one of the most important figures in American and World Poetry. Indeed "Prufrock" and The Waste Land, Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man wouldn't exist without Pound, who, it was noted by Hemingway, only spent a fifth of his energies on his own writing; the rest devoted to writers, from Eliot to Robert Frost to artist Wyndham Lewis. Pound indeed would have been a champion of The Beatles. The poet is said to have "smiled lightly" when he first heard "ER" (Pound's smile came when introduced to The Beatles by Allen Ginsberg); of course he did: two lonely people, living in a church community, cannot connect or associated with their surroundings and those who inhabit them and end up living their lives alone and apart, one burying the other, a grim irony that would be funny if it weren't dreadful. Eleanor dies in church, buried along with her name. Even Ozymandias, despite the "lone and level sands stretch(ing) far away," has his name. In Eleanor Rigby's death we see the death of hope itself, the ultimate tragedy.

Despite the controversy regarding his Axis support and subsequent subversive broadcasts, Ezra Pound remains one of the most important figures in American and World Poetry. Indeed "Prufrock" and The Waste Land, Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man wouldn't exist without Pound, who, it was noted by Hemingway, only spent a fifth of his energies on his own writing; the rest devoted to writers, from Eliot to Robert Frost to artist Wyndham Lewis. Pound indeed would have been a champion of The Beatles. The poet is said to have "smiled lightly" when he first heard "ER" (Pound's smile came when introduced to The Beatles by Allen Ginsberg); of course he did: two lonely people, living in a church community, cannot connect or associated with their surroundings and those who inhabit them and end up living their lives alone and apart, one burying the other, a grim irony that would be funny if it weren't dreadful. Eleanor dies in church, buried along with her name. Even Ozymandias, despite the "lone and level sands stretch(ing) far away," has his name. In Eleanor Rigby's death we see the death of hope itself, the ultimate tragedy. Ezra Pound by Wyndham LewisThe story is typical of Paul with its two functioning, unrelated characters brought into ironic proximity in the final scene, as though it were a novel by Bronte, and a precursor to "Penny Lane." One can't help but sense the influence of John upon Paul's particular choices of detailed imagery and idiosyncratic turns of phrase. The song avoids sentimentality by keeping its distance from the subject, presenting the action like a film script: "Look at him working," and uses various tense to imply shift in perspective: Eleanor Rigby "died in the church" (past tense), while in the same scene, Father MacKenzie is "wiping the dirt from his hands" (present tense).

Ezra Pound by Wyndham LewisThe story is typical of Paul with its two functioning, unrelated characters brought into ironic proximity in the final scene, as though it were a novel by Bronte, and a precursor to "Penny Lane." One can't help but sense the influence of John upon Paul's particular choices of detailed imagery and idiosyncratic turns of phrase. The song avoids sentimentality by keeping its distance from the subject, presenting the action like a film script: "Look at him working," and uses various tense to imply shift in perspective: Eleanor Rigby "died in the church" (past tense), while in the same scene, Father MacKenzie is "wiping the dirt from his hands" (present tense).When Paul McCartney first wrote "ER" he had the music worked out before the lyrics, as he often did ("Yesterday," remember, started out as "Scrambled Eggs"). Paul often used placeholder lyrics that he'd subsequently abandon. To be specific, the original version began, "Ola Na Tungee/ Blowing his mind in the dark/ With a pipe full of clay/ No one can say." In other words, a guy with a quasi-Hindu name getting high, a far cry from the English Village equivalent to Desolation Street. Paul later picked the name Rigby from a wine and spirits shop in Bristol, and the name Eleanor in reference to the British actress, Eleanor Bron, who appeared in Help! The priest was originally named Father McCartney, but John's friend Pete Shotton warned that people would think he was talking about his own father. George reportedly contributed the line "Ah look at all the lonely people," while Ringo contributed the idea of having Father McKenzie darning his socks in the night. There are of course many course one may take analyzing the iconic single, and a day's worth of interesting research is in store for those who try. Ultimately, despite the subjective nature of the lyrics, Eleanor Rigby exists, at least in name; indeed at the cruelly young age of 44, Eleanor Rigby died in the same house where she had been born, was interred in the graveyard of St Peter's Church in Liverpool, and had her name added prominently on an increasingly crowded headstone. The story, its evolution and its ties to history are fascinating.

In 1964, the Beatles held the top 5 positions on Billboard's Hot 100. On April 4th of that year, "Can't Buy Me Love" was No. 1, followed by "Twist and Shout," "She Loves You," "I Wanna Hold Your Hand" and "Please Please Me." It was an accomplishment which can never be equaled, but from August 1966 through the end of 1967, the Beatles were at the top of the chart in a myriad of categories. In August '66, Rubber Soul was the No. 1 album, and would remain so for eight weeks, with the double A sided "Yellow Submarine/Elenor Rigby" at the top of the singles charts for four weeks. Between January 1967 and the end of the year, the Beatles remained at the top of the charts with the release of three additional LPs, Revolver and Sgt. Pepper, followed by the EP release worldwide and the full length LP as released by Capitol in the U.S. of Magical Mystery Tour. The singles release during this period were: "Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields" (which made it only to No. 2, based on The Monkees' "I'm a Believer"); "All You Need is Love" and "Hello Goodbye." Imagine four unparalleled LPs with two solid No. 1 singles in a little over a year, all from the same band!

Published on May 06, 2018 05:14

Music and Poetry

We settle into a seat on a train, at times forgetting the destination, enjoying the ride of its own accord. The train is its own world, even as it moves with purpose; if the train broke down, we'd be annoyed - the purpose of the train slips our minds only fleetingly - yet it allows us in its mesmerizing clickity-clack to forget the reason for the journey and to simply enjoy the experience. Expression is like this, too. We talk for a reason, and yet we also just enjoy talking. Poetry then is reticent expressiveness; it combines the enjoyable and the purposeful aspects of the train ride; at times rambling on, clickity-clackiting; at times direct and purposeful. As AM continues its little sabbatical on poetry, we've contemplated a myriad of songs, seeking out the journey, whether or not there is a destination. For this little aside (expect more over the next few days), we've constricted the poetry, with some exception, to 1968. The poetry of a song like Leslie Gore's "It’s My Party," therefore, pure Emily Brönte btw, doesn't make the cut, nor does The Stones' "Ruby Tuesday" or Rod Stewart's "Maggie Mae."

1968 features prominently in the music-as-poetry construct, a time which, artistically, happily, resembles the Romantic era: sensual and intellectual, though not overly so, and, because indulgence was miraculously tempered by a certain unstated restraint, popular. In the last post, we touched on the debate between poetry and lyrics: while music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry, poetry is its own music, condemning it to be naked, without music, forever. I don't know which I feel sorrier for. Some will say the two can never be reconciled. Madness and torture! Why do they exist, never to meet! Poetry and music! Divided heart! Divided mind! Poor, divided mankind! (Dramatic, huh?)

Oh, poppycock, of course, they do; they meet and have an illicit affair, and if an especially beautiful melody accompanies the words of a particular lyric, making the words even more lovely, do we assume the words are responsible or has the music inspired the words?

For the research here, and because Leslie Gore didn't qualify, I found myself in realism-mode, the Brönte factor, and in its simplicity and constructive realism, adding in a dose of repetition to make Mark Twain proud, I chose McCartney's aforementioned "Why Don’t We Do It In the Road."

Love it or hate it, celebrate it or be embarrassed by it, "Why Don't We Do It In The Road?" showed that the Fab Four were more than peace, love and flowers (or is the song the essence of the hippie trinity?). Some might call it bold (particularly from McCartney), yet something like this had to be expected, especially on an album with a plain white cover, as if something subversive was inside. After the furor caused by John's "We're bigger than Jesus" statement, and the banned songs by the BBC due to drug references, not to mention John and Yoko's full frontal on the cover of Two Virgins, why not compose a song about the most absurdly taboo subject imaginable and see how many feathers could be ruffled?

"The idea behind 'Why Don't We Do It In The Road' came from something I'd seen in Rishikesh," Paul explained. "I was up on the flat roof meditating and I'd seen a troupe of monkeys walking along in the jungle and a male just hopped on to the back of this female and gave her one, as they say in the vernacular. Within two or three seconds he hopped off again, and looked around as if to say, 'It wasn't me,' and she looked around as if there had been some mild disturbance but thought, 'Huh, I must have imagined it,' and she wandered off.

"And I thought, 'Bloody hell, that puts it all into a cocked hat.' That's how simple the act of procreation is, this bloody monkey just hopping on and hopping off. There is an urge, they do it, and it's done with. And it's that simple. We have horrendous problems with it, and yet animals don't.” While Paul’s account makes it simply rudimentary, it also takes out the romance. Frankly, doesn't the song express our basic instincts, not just in a physical manner, indeed in this respect we’re like animals, but in an obliquely human way as well: "WDWDIITR" is all about the romance of lust. How Byronic is that?

So, back to the train. Monkeys just do it in the road. We take our time. We get on a train. We sit together and chat, forget about the ride, forget about the destination; it's all, at least for now, about the journey. And yet, in the nuance of the encounter, you contemplate her smile, the fullness of her breasts, his scruffy cool, and in your mind you just want to push him/her up against... Those thoughts wind through your mind, come and go, the question building, insistent, louder and louder. First, it's a question; then it's a plea:

Why don't we do it in the road?No one will be watching us

Why don't we do it in the road?

Published on May 06, 2018 04:18

May 5, 2018

When Mary Climbed In...

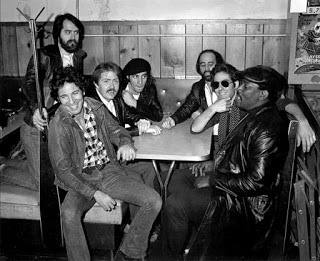

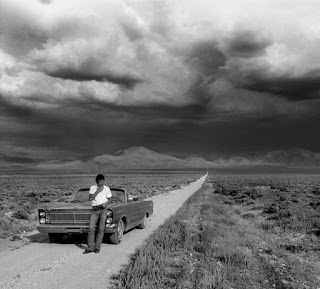

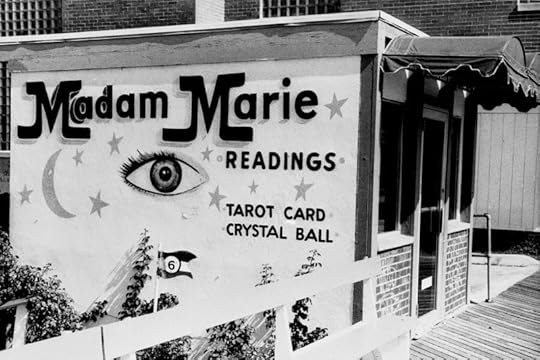

Bruce Springsteen's "Thunder Road" isn't just a song you listen to – it's one you watch in your mind — a sonic piece of cinema the budding songwriter produced, wrote and directed to show in the theater of your imagination. It even takes its name from a 1958 Arthur Ripley crime drama, Thunder Road – a drive-in vehicle for Robert Mitchum. Comparing Springsteen to pioneer filmmaker John Ford, Drive-By Truckers singer, "Tramp" Patterson Hood described the song as Springsteen's Stagecoach, in that it "announced his artistic arrival; that he's the 'real deal'."

As the needle falls onto the LP's A-side, the dreamy tickle of pianist Roy Bittan's ivories chime in contrast to the yearning howl of a harmonica that sounds like the creak of a screen door in slow motion.

As the tempo quickens to a bouncy lilt, the harmonica exits the scene and we meet our nameless narrator and Mary, who for the time being suffices as his Juliet. (She's not a beauty but, hey, she's all right.) This is how Springsteen lets us know that it's not about love but about the refuge of the road, about the romance of a two-lane highway to anywhere.

We can't help but feel like voyeurs as Bruce projects his vision of Mary dancing across a porch on the movie screen of our mind's eye, or as we watch the couple's automotive chariot – their burned out Chevrolet vanish into the sunset. The couple takes their destiny into their own hands because their town's full of losers, and they're pulling out to win. By the time they do, we're not watching, but riding along with them. It's rock's answer to the best American poets; it's Whitman for the common man and indeed the greatest example of American poetry in the 2nd half of the 20th Century. It's easy to read into it, but is it really that deep? "Thunder Road" is simply a song about getting the hell out - out of school, out of town, out of your parents' house; it's about freedom. Springsteen's masterpiece is a universal theme in a culturally specific setting. Could have been your hometown instead.

We can't help but feel like voyeurs as Bruce projects his vision of Mary dancing across a porch on the movie screen of our mind's eye, or as we watch the couple's automotive chariot – their burned out Chevrolet vanish into the sunset. The couple takes their destiny into their own hands because their town's full of losers, and they're pulling out to win. By the time they do, we're not watching, but riding along with them. It's rock's answer to the best American poets; it's Whitman for the common man and indeed the greatest example of American poetry in the 2nd half of the 20th Century. It's easy to read into it, but is it really that deep? "Thunder Road" is simply a song about getting the hell out - out of school, out of town, out of your parents' house; it's about freedom. Springsteen's masterpiece is a universal theme in a culturally specific setting. Could have been your hometown instead.

As the needle falls onto the LP's A-side, the dreamy tickle of pianist Roy Bittan's ivories chime in contrast to the yearning howl of a harmonica that sounds like the creak of a screen door in slow motion.

As the tempo quickens to a bouncy lilt, the harmonica exits the scene and we meet our nameless narrator and Mary, who for the time being suffices as his Juliet. (She's not a beauty but, hey, she's all right.) This is how Springsteen lets us know that it's not about love but about the refuge of the road, about the romance of a two-lane highway to anywhere.

We can't help but feel like voyeurs as Bruce projects his vision of Mary dancing across a porch on the movie screen of our mind's eye, or as we watch the couple's automotive chariot – their burned out Chevrolet vanish into the sunset. The couple takes their destiny into their own hands because their town's full of losers, and they're pulling out to win. By the time they do, we're not watching, but riding along with them. It's rock's answer to the best American poets; it's Whitman for the common man and indeed the greatest example of American poetry in the 2nd half of the 20th Century. It's easy to read into it, but is it really that deep? "Thunder Road" is simply a song about getting the hell out - out of school, out of town, out of your parents' house; it's about freedom. Springsteen's masterpiece is a universal theme in a culturally specific setting. Could have been your hometown instead.

We can't help but feel like voyeurs as Bruce projects his vision of Mary dancing across a porch on the movie screen of our mind's eye, or as we watch the couple's automotive chariot – their burned out Chevrolet vanish into the sunset. The couple takes their destiny into their own hands because their town's full of losers, and they're pulling out to win. By the time they do, we're not watching, but riding along with them. It's rock's answer to the best American poets; it's Whitman for the common man and indeed the greatest example of American poetry in the 2nd half of the 20th Century. It's easy to read into it, but is it really that deep? "Thunder Road" is simply a song about getting the hell out - out of school, out of town, out of your parents' house; it's about freedom. Springsteen's masterpiece is a universal theme in a culturally specific setting. Could have been your hometown instead.

Published on May 05, 2018 04:25

May 4, 2018

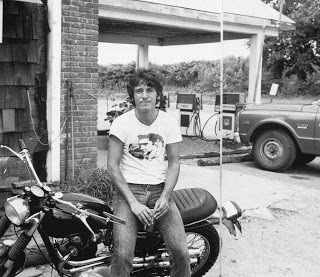

1982 - Nebraska

Asbury Park was the young and dumb and full of cum LP of Springsteen's youth, and Born to Run, while a masterpiece ("Thunder Road" the equivalent of Whitman in its ability to capture youth in America) was simply Bruce perfecting what was already Bruce, but on Nebraska, Springsteen isn't the singer/songwriter growing up, but all grown up. Nebraska's themes are nihilistic, dark, and consistent. It opens with a song about a ruthless, disaffected murderer, 1950s' serial killer Charles Starkweather from first-person perspective and his teenage lover. Powerful lyrics pervade "Atlantic City" that rival Dylan: "Well now everything dies baby that's a fact/ But maybe everything that dies someday comes back./ Put your makeup on, fix your hair up pretty/ And meet me tonight in Atlantic City." Funny where we think we'll find solutions. Each track thereafter is told from the perspective of someone who's done or is doing something wrong for some reason or the another. No answers. And Bruce weaves the stories matter of factly, as though we're just unlucky, all just playing the cards we're dealt: "Now judge, judge, I got debts no honest man could pay/ The bank was holding my mortgage, they taking my house away./ Now I ain't saying that makes me an innocent man,/ But it was more and all this that put that gun in my hand."

Asbury Park was the young and dumb and full of cum LP of Springsteen's youth, and Born to Run, while a masterpiece ("Thunder Road" the equivalent of Whitman in its ability to capture youth in America) was simply Bruce perfecting what was already Bruce, but on Nebraska, Springsteen isn't the singer/songwriter growing up, but all grown up. Nebraska's themes are nihilistic, dark, and consistent. It opens with a song about a ruthless, disaffected murderer, 1950s' serial killer Charles Starkweather from first-person perspective and his teenage lover. Powerful lyrics pervade "Atlantic City" that rival Dylan: "Well now everything dies baby that's a fact/ But maybe everything that dies someday comes back./ Put your makeup on, fix your hair up pretty/ And meet me tonight in Atlantic City." Funny where we think we'll find solutions. Each track thereafter is told from the perspective of someone who's done or is doing something wrong for some reason or the another. No answers. And Bruce weaves the stories matter of factly, as though we're just unlucky, all just playing the cards we're dealt: "Now judge, judge, I got debts no honest man could pay/ The bank was holding my mortgage, they taking my house away./ Now I ain't saying that makes me an innocent man,/ But it was more and all this that put that gun in my hand."Poignant as shit.

"Highway Patrolman" is from the perspective of a cop who claims to always have done an honest job. His brother gets in trouble with the law and in a high-speed chase, the cop lets him get away. "A man turns his back on his family, he just ain't no good" clashes dead away with his duty and he does the only thing he really could have. He puts the reasons to catch his brother on one side of the scale, the reasons to let him go on the other, no choice in how important each reason is - how much weight they have. It's a story of Biblical proportions. We don't judge our brother. Heartbreaking. The LPs closer, "Reason to Believe" is The Boss with BS. Life's a bitch and then you die: "Struck me kinda funny, yeah it's funny sir to me/ how at the end of every hard-earned day people find some reason to believe."

"Highway Patrolman" is from the perspective of a cop who claims to always have done an honest job. His brother gets in trouble with the law and in a high-speed chase, the cop lets him get away. "A man turns his back on his family, he just ain't no good" clashes dead away with his duty and he does the only thing he really could have. He puts the reasons to catch his brother on one side of the scale, the reasons to let him go on the other, no choice in how important each reason is - how much weight they have. It's a story of Biblical proportions. We don't judge our brother. Heartbreaking. The LPs closer, "Reason to Believe" is The Boss with BS. Life's a bitch and then you die: "Struck me kinda funny, yeah it's funny sir to me/ how at the end of every hard-earned day people find some reason to believe."Springsteen sings in black and white on an LP that's far from accessible, yet there's a singer/songwriter feel to Nebraska that very few albums match. The stripped down quality of the music, combined with the darkness of the music, puts one in the same frame of mind as Neil Young's "Tonight's The Night" or The Velvet Underground, call it music noir. The characters, situations, and emotions displayed here are those that we don't like to encounter, but far more common than those that make us feel good. That's dangerous territory, for someone like Springsteen, whose live shows are everyone's favorite party, yelling "Bruce, Bruce, Bruce." Nobody doing that here. Nebraska is the catalyst for every singer-songwriter since, from Ben Gibbard to Iron and Wine to Sun Kil Moon, but it's no party.

Published on May 04, 2018 04:04

May 3, 2018

Greetings From Asbury Park

There are scattered few who recognize genius just like that (finger snap). Imagine hearing the 9th for the first time back in '24 (1824) in Vienna's Theater am Kärntnertor, and recognizing its significance, its brilliance, its scope. Or more so, imagine having that same insight at the 1st Symphony instead. Who was paying attention? Then imagine hearing Greetings From Asbury Park at the Stone Pony, the young Springsteen spitting out words in poetic torrents, erroneously compared to Dylan in the same manner in which Beethoven was compared to Mozart. I wonder if I would have had the insight. Or, like Berlioz would I have intimated "This is admirably crafted music, clear, alert, but lacking in strong personality, cold and sometimes rather small-minded."

There are scattered few who recognize genius just like that (finger snap). Imagine hearing the 9th for the first time back in '24 (1824) in Vienna's Theater am Kärntnertor, and recognizing its significance, its brilliance, its scope. Or more so, imagine having that same insight at the 1st Symphony instead. Who was paying attention? Then imagine hearing Greetings From Asbury Park at the Stone Pony, the young Springsteen spitting out words in poetic torrents, erroneously compared to Dylan in the same manner in which Beethoven was compared to Mozart. I wonder if I would have had the insight. Or, like Berlioz would I have intimated "This is admirably crafted music, clear, alert, but lacking in strong personality, cold and sometimes rather small-minded."  I want to erase all of this; the pretentiousness of comparing Springsteen to Beethoven seems silly and uncool, though Ludwig Van was a rock star in his day, indeed The Boss.

I want to erase all of this; the pretentiousness of comparing Springsteen to Beethoven seems silly and uncool, though Ludwig Van was a rock star in his day, indeed The Boss.Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., (AM8) announced a considerable new talent and though he wouldn't shake the "new Bob Dylan" till Born to Run, his lyrical detail certainly had a different feel from Dylan's 60s triumphs. Take the fab opener "Blinded by the Light," a wonderfully surreal tale brimming with unusual imagery and snappy rhyming schemes; this highly innovative rocker was a brave choice as the opening gambit, but showed Springsteen's unshakable confidence in his lyrics even at this early stage of his career. Perhaps a lesser man would have kicked off with the delightfully catchy "Does This Bus Stop at 82nd Street?" Vaguely reminiscent of The Band at their best, this irresistible two minute pop nugget sported some fine lyrics: "Queen of diamonds, ace of spades, newly discovered lovers of the everglades, they take out a full page ad in the trades to announce their arrival" – yet it was the jaunty tune that really caught the imagination.

If these tracks had encapsulated the best of Springsteen's lighthearted wordplay, then the edgier side of the muse surfaces in “Growin’ Up,” which saw the tentative onset of many key Springsteen themes. His desire to become a leather clad street hero is obvious from the outset and the rebellion scattered throughout only underlines this aim. However it's the line "I swear I found the key to the universe in the engine of an old parked car" that first establishes the car as vital element in Bruce's lyrical armory. Overall the track skilfully reflects both the bold ambition and tense uncertainty of youth, managing to sound as though there's still a fair amount of self-doubt behind the seemingly confident statements. In contrast, the outstanding street anthem "It's Hard to be a Saint in the City" oozes gritty experience, yet despite the slick swag the tension is maintained by snippets of danger and drama throughout.

If these tracks had encapsulated the best of Springsteen's lighthearted wordplay, then the edgier side of the muse surfaces in “Growin’ Up,” which saw the tentative onset of many key Springsteen themes. His desire to become a leather clad street hero is obvious from the outset and the rebellion scattered throughout only underlines this aim. However it's the line "I swear I found the key to the universe in the engine of an old parked car" that first establishes the car as vital element in Bruce's lyrical armory. Overall the track skilfully reflects both the bold ambition and tense uncertainty of youth, managing to sound as though there's still a fair amount of self-doubt behind the seemingly confident statements. In contrast, the outstanding street anthem "It's Hard to be a Saint in the City" oozes gritty experience, yet despite the slick swag the tension is maintained by snippets of danger and drama throughout. "Lost in the Flood" was another street-based gem. This time the arrangement was more understated allowing the lyrics to take centre stage. What could have been a simple tale of cars and guns is elevated to epic status through its immaculate detail. The opening verse sees the ragamuffin gunner returning home to a religiously bankrupt town – "they’re breaking beams and crosses with a spastic's reeling perfection, nuns run bald through Vatican halls pregnant, pleading immaculate conception" from which Jimmy the Saint tries to escape through frequent drag racing. Unfortunately over-confidence leads to his dramatic demise in a hurricane – "and there’s nothing left but some blood where the body fell, that is nothing left that you could sell, just junk all across the horizon, a real highwayman's farewell." Finally the town's frustrations erupt into a gun-fight which results in death and injury – "and Bronx’s best apostle stands with his hand on his own hardware, everything stops, you hear five quick shots, the cops come up for air." One of Springsteen's most downbeat and violent songs of the period, "Lost in the Flood" was another track surprisingly compared with Dylan, though more for its fine construction than its graphic content.

Less disturbing were the unexpectedly tender strains of "Spirit in the Night." Rather than use nighttime as a backdrop to tough street-life, the track tapped into the mystical beauty of the night. Ultimately Crazy Janey and our narrator fall in love under the near-magical spell of the gypsy angels down by near Greasy Lake. An odd love song that has more in common with A Midsummer Night’s Dream than Springsteen's usual bedfellows. Greetings from Asbury Park is Springsteen's most interesting album (alongside Nebraska and Tom Joad.), providing a fascinating glimpse of Bruce in the pre-Boss years. No, not the "best" album, but clearly Greetings is the album that most contained the poet, or conversely set him free.

Less disturbing were the unexpectedly tender strains of "Spirit in the Night." Rather than use nighttime as a backdrop to tough street-life, the track tapped into the mystical beauty of the night. Ultimately Crazy Janey and our narrator fall in love under the near-magical spell of the gypsy angels down by near Greasy Lake. An odd love song that has more in common with A Midsummer Night’s Dream than Springsteen's usual bedfellows. Greetings from Asbury Park is Springsteen's most interesting album (alongside Nebraska and Tom Joad.), providing a fascinating glimpse of Bruce in the pre-Boss years. No, not the "best" album, but clearly Greetings is the album that most contained the poet, or conversely set him free.

Published on May 03, 2018 17:42

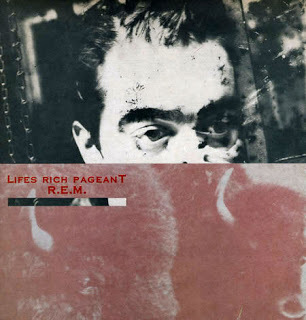

REM and Springsteen

AM isn't shy about rating rock music as poetry, as the past couple posts show. There are those, indeed, who associate themselves more with poets more than musicians; first and foremost, Dylan. Robbie Robertson said, "I learned early on with Bob that the people he hung around with were not musicians. They were poets, like Allen Ginsberg. When we were in Europe, there’d be poets coming out of the woodwork. His writing came directly out of a tremendous poetic influence, a license to write in images that weren't in the Tin Pan Alley tradition or typically rock 'n' roll, either." Last year, the Nobel Prize committee agreed, raising Dylan's literary status far above his music.

Over time, the Tin Pan Alley set has gained in reputation as well; how could they not with lyricists like Cole Porter wielding words like a magic wand: "Let me live 'neath your spell/ You do that voodoo that you do so well." Ira Gershwin, who, unlike Porter, only wrote lyrics, exemplified the five essential points of poetry: words; wide-ranging subject matter; imagery; symbolism; and sound effects (alliteration, meter and a myriad of elements that the average listener dismisses as secondary to rhyme. In this, we understand why rap's gangsta days seem so trivial, even comical, while hip-hop in 2018 wins the Pulitzer Prize). Here's an example from Gershwin: "There is somebody I'm longing to see,/ I hope that she/ turns out to be,/ Someone to watch over me" – incredible rhyme, wonderful interpolation of sounds, fabulous meter.

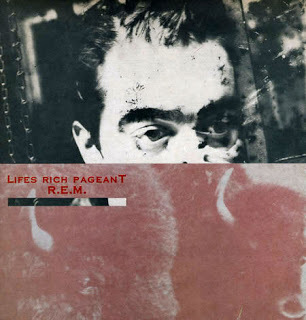

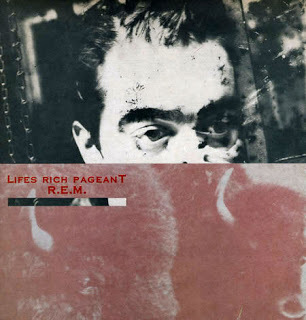

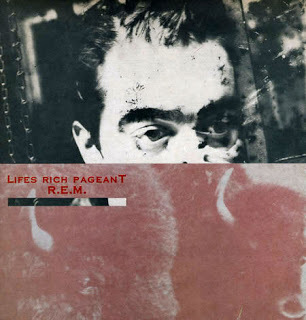

Despite the image of loud guitars, pounding drums and incomprehensible vocals, great rock music starts with lyrics. The other elements of rock music shape themselves around the words, extending and strengthening them. People sometimes argue that the words in rock songs can't be all that important, because they are often so hard to decipher or even to hear. Yet there is a holographic quality to great art, in that the message of a piece is embedded in the whole of the work. Take REM, for instance (or in the extreme, Cocteau Twins). The lyrics at times are incomprehensible. "Swan Swan H" contains remarkable lyrics that no one (not even the rain) can fully understand.

Swan, swan, hummingbird

Swan, swan, hummingbird

Hurrah we are all free now

What noisy cats are we

Girl and dog he bore his cross

A long low time ago people talk to me

Johnny Reb what's the price of fans

Forty a piece or three for one dollar?

Hey captain don't you want to buy

Some bone chains and toothpicks?

Poignancy in the guise of gibberish. Oh, don't think that I’ll sit here and decipher its meaning as a whole; remember that it's words + meter + subject matter + symbolism +… The song represents confusion, particularly of a young man growing up in the South with grand stories of Johnny Reb's heroics, a conflict enmeshed in a young man's southern outlook. We grow up with our heroes and down, crashing, they come.

The tune's incredible rhetoric and pace make for glorious poetry. Thoughts negating thoughts, words cut short like great filmmaking in which dialogue, you know, like real life, overlaps, is filled with cutoffs and incomplete sentences – it can indeed be disconcerting. The song defies clarity, even though such confusion is commonplace in our real speech.

Dylan avoided such an avant-garde approach to concentrate on subject, initially writing protest songs about political and social issues, but then transitioning to very personal subjects. Once he demonstrated the possibilities, others followed. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's Déjà vu is the perfect example. On this one collection we find songs about passing wisdom from one generation to the next ("Teach Your Children"), the importance of nonconformity ("Almost Cut My Hair"), the inability to escape one's past ("Helpless"), the nature of the emerging counter-culture ("Woodstock"), an almost suicidal expression of despair ("4 + 20") and simple domesticity ("Our House"), elements that make the primary mode of appreciation for the art form more akin to poetry. Words are used to encapsulate, preserve and amplify a particular experience, sensation, thought or feeling. In the space of a few verses and a chorus, just enough is said to convey the intended meaning.

The perfect example of rock poetry as storytelling is found in Bruce Springsteen's earliest work and again, in a song that could be considered the ultimate in storytelling, "The River." Springsteen's sister Ginny became pregnant at age 18 and quickly married her child's father, Mickey Shave, who took a construction job to support his family. "They had to struggle very hard back in the late Seventies like so many people are doing today," Springsteen said. He turned their story into his most moving working-class lament, a slow, sparse ballad with a mournful harmonica that sounds a bit like a funeral dirge. "Every bit of it was true," Ginny told Springsteen biographer Peter Ames Carlin. "And here I am, completely exposed. I didn't like it at first – but now it's my favorite song." Those words may sum up rock lyrics as poetry: "completely exposed."

Then I got Mary pregnant

And man that was all she wrote

And for my nineteenth birthday

I got a union card and a wedding coat

We went down to the courthouse

And the judge put it all to rest

No wedding day smiles, no walk down the aisle

No flowers, no wedding dress

Funny, all the dreams of "Born to Run" are shattered in those lyrics. They're not, by any means, as beautiful as "Born to Run" – or maybe they are but they're stripped of their fancy. They are sad instead of hopeful, the end, rather than the beginning, there are no dreams, only memories of that short-lived time down by the river. Ho-hum.

Over the next few posts we will explore rock music as poetry, from Springsteen to Prefab Sprout, from Joni to Graham, from Paul Simon to T.S. Eliot.

Over time, the Tin Pan Alley set has gained in reputation as well; how could they not with lyricists like Cole Porter wielding words like a magic wand: "Let me live 'neath your spell/ You do that voodoo that you do so well." Ira Gershwin, who, unlike Porter, only wrote lyrics, exemplified the five essential points of poetry: words; wide-ranging subject matter; imagery; symbolism; and sound effects (alliteration, meter and a myriad of elements that the average listener dismisses as secondary to rhyme. In this, we understand why rap's gangsta days seem so trivial, even comical, while hip-hop in 2018 wins the Pulitzer Prize). Here's an example from Gershwin: "There is somebody I'm longing to see,/ I hope that she/ turns out to be,/ Someone to watch over me" – incredible rhyme, wonderful interpolation of sounds, fabulous meter.

Despite the image of loud guitars, pounding drums and incomprehensible vocals, great rock music starts with lyrics. The other elements of rock music shape themselves around the words, extending and strengthening them. People sometimes argue that the words in rock songs can't be all that important, because they are often so hard to decipher or even to hear. Yet there is a holographic quality to great art, in that the message of a piece is embedded in the whole of the work. Take REM, for instance (or in the extreme, Cocteau Twins). The lyrics at times are incomprehensible. "Swan Swan H" contains remarkable lyrics that no one (not even the rain) can fully understand.

Swan, swan, hummingbird

Swan, swan, hummingbirdHurrah we are all free now

What noisy cats are we

Girl and dog he bore his cross

A long low time ago people talk to me

Johnny Reb what's the price of fans

Forty a piece or three for one dollar?

Hey captain don't you want to buy

Some bone chains and toothpicks?

Poignancy in the guise of gibberish. Oh, don't think that I’ll sit here and decipher its meaning as a whole; remember that it's words + meter + subject matter + symbolism +… The song represents confusion, particularly of a young man growing up in the South with grand stories of Johnny Reb's heroics, a conflict enmeshed in a young man's southern outlook. We grow up with our heroes and down, crashing, they come.

The tune's incredible rhetoric and pace make for glorious poetry. Thoughts negating thoughts, words cut short like great filmmaking in which dialogue, you know, like real life, overlaps, is filled with cutoffs and incomplete sentences – it can indeed be disconcerting. The song defies clarity, even though such confusion is commonplace in our real speech.

Dylan avoided such an avant-garde approach to concentrate on subject, initially writing protest songs about political and social issues, but then transitioning to very personal subjects. Once he demonstrated the possibilities, others followed. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's Déjà vu is the perfect example. On this one collection we find songs about passing wisdom from one generation to the next ("Teach Your Children"), the importance of nonconformity ("Almost Cut My Hair"), the inability to escape one's past ("Helpless"), the nature of the emerging counter-culture ("Woodstock"), an almost suicidal expression of despair ("4 + 20") and simple domesticity ("Our House"), elements that make the primary mode of appreciation for the art form more akin to poetry. Words are used to encapsulate, preserve and amplify a particular experience, sensation, thought or feeling. In the space of a few verses and a chorus, just enough is said to convey the intended meaning.

The perfect example of rock poetry as storytelling is found in Bruce Springsteen's earliest work and again, in a song that could be considered the ultimate in storytelling, "The River." Springsteen's sister Ginny became pregnant at age 18 and quickly married her child's father, Mickey Shave, who took a construction job to support his family. "They had to struggle very hard back in the late Seventies like so many people are doing today," Springsteen said. He turned their story into his most moving working-class lament, a slow, sparse ballad with a mournful harmonica that sounds a bit like a funeral dirge. "Every bit of it was true," Ginny told Springsteen biographer Peter Ames Carlin. "And here I am, completely exposed. I didn't like it at first – but now it's my favorite song." Those words may sum up rock lyrics as poetry: "completely exposed."

Then I got Mary pregnant

And man that was all she wrote

And for my nineteenth birthday

I got a union card and a wedding coat

We went down to the courthouse

And the judge put it all to rest

No wedding day smiles, no walk down the aisle

No flowers, no wedding dress

Funny, all the dreams of "Born to Run" are shattered in those lyrics. They're not, by any means, as beautiful as "Born to Run" – or maybe they are but they're stripped of their fancy. They are sad instead of hopeful, the end, rather than the beginning, there are no dreams, only memories of that short-lived time down by the river. Ho-hum.

Over the next few posts we will explore rock music as poetry, from Springsteen to Prefab Sprout, from Joni to Graham, from Paul Simon to T.S. Eliot.

Published on May 03, 2018 06:00

Rock Music as Poetry - Part 2 - REM and Springsteen

AM isn't shy about rating rock music as poetry, as the past couple posts show. There are those, indeed, who associate themselves more with poets more than musicians; first and foremost, Dylan. Robbie Robertson said, "I learned early on with Bob that the people he hung around with were not musicians. They were poets, like Allen Ginsberg. When we were in Europe, there’d be poets coming out of the woodwork. His writing came directly out of a tremendous poetic influence, a license to write in images that weren't in the Tin Pan Alley tradition or typically rock 'n' roll, either." Last year, the Nobel Prize committee agreed, raising Dylan's literary status far above his music.

Over time, the Tin Pan Alley set has gained in reputation as well; how could they not with lyricists like Cole Porter wielding words like a magic wand: "Let me live 'neath your spell/ You do that voodoo that you do so well." Ira Gershwin, who, unlike Porter, only wrote lyrics, exemplified the five essential points of poetry: words; wide-ranging subject matter; imagery; symbolism; and sound effects (alliteration, meter and a myriad of elements that the average listener dismisses as secondary to rhyme. In this, we understand why rap's gangsta days seem so trivial, even comical, while hip-hop in 2018 wins the Pulitzer Prize). Here's an example from Gershwin: "There is somebody I'm longing to see,/ I hope that she/ turns out to be,/ Someone to watch over me" – incredible rhyme, wonderful interpolation of sounds, fabulous meter.

Despite the image of loud guitars, pounding drums and incomprehensible vocals, great rock music starts with lyrics. The other elements of rock music shape themselves around the words, extending and strengthening them. People sometimes argue that the words in rock songs can't be all that important, because they are often so hard to decipher or even to hear. Yet there is a holographic quality to great art, in that the message of a piece is embedded in the whole of the work. Take REM, for instance (or in the extreme, Cocteau Twins). The lyrics at times are incomprehensible. "Swan Swan H" contains remarkable lyrics that no one (not even the rain) can fully understand.

Swan, swan, hummingbird

Swan, swan, hummingbird

Hurrah we are all free now

What noisy cats are we

Girl and dog he bore his cross

A long low time ago people talk to me

Johnny Reb what's the price of fans

Forty a piece or three for one dollar?

Hey captain don't you want to buy

Some bone chains and toothpicks?

Poignancy in the guise of gibberish. Oh, don't think that I’ll sit here and decipher its meaning as a whole; remember that it's words + meter + subject matter + symbolism +… The song represents confusion, particularly of a young man growing up in the South with grand stories of Johnny Reb's heroics, a conflict enmeshed in a young man's southern outlook. We grow up with our heroes and down, crashing, they come.

The tune's incredible rhetoric and pace make for glorious poetry. Thoughts negating thoughts, words cut short like great filmmaking in which dialogue, you know, like real life, overlaps, is filled with cutoffs and incomplete sentences – it can indeed be disconcerting. The song defies clarity, even though such confusion is commonplace in our real speech.

Dylan avoided such an avant-garde approach to concentrate on subject, initially writing protest songs about political and social issues, but then transitioning to very personal subjects. Once he demonstrated the possibilities, others followed. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's Déjà vu is the perfect example. On this one collection we find songs about passing wisdom from one generation to the next ("Teach Your Children"), the importance of nonconformity ("Almost Cut My Hair"), the inability to escape one's past ("Helpless"), the nature of the emerging counter-culture ("Woodstock"), an almost suicidal expression of despair ("4 + 20") and simple domesticity ("Our House"), elements that make the primary mode of appreciation for the art form more akin to poetry. Words are used to encapsulate, preserve and amplify a particular experience, sensation, thought or feeling. In the space of a few verses and a chorus, just enough is said to convey the intended meaning.

The perfect example of rock poetry as storytelling is found in Bruce Springsteen's earliest work and again, in a song that could be considered the ultimate in storytelling, "The River." Springsteen's sister Ginny became pregnant at age 18 and quickly married her child's father, Mickey Shave, who took a construction job to support his family. "They had to struggle very hard back in the late Seventies like so many people are doing today," Springsteen said. He turned their story into his most moving working-class lament, a slow, sparse ballad with a mournful harmonica that sounds a bit like a funeral dirge. "Every bit of it was true," Ginny told Springsteen biographer Peter Ames Carlin. "And here I am, completely exposed. I didn't like it at first – but now it's my favorite song." Those words may sum up rock lyrics as poetry: "completely exposed."

Then I got Mary pregnant

And man that was all she wrote

And for my nineteenth birthday

I got a union card and a wedding coat

We went down to the courthouse

And the judge put it all to rest

No wedding day smiles, no walk down the aisle

No flowers, no wedding dress

Funny, all the dreams of "Born to Run" are shattered in those lyrics. They're not, by any means, as beautiful as "Born to Run" – or maybe they are but they're stripped of their fancy. They are sad instead of hopeful, the end, rather than the beginning, there are no dreams, only memories of that short-lived time down by the river. Ho-hum.

Over the next few posts we will explore rock music as poetry, from Springsteen to Prefab Sprout, from Joni to Graham, from Paul Simon to T.S. Eliot.

Over time, the Tin Pan Alley set has gained in reputation as well; how could they not with lyricists like Cole Porter wielding words like a magic wand: "Let me live 'neath your spell/ You do that voodoo that you do so well." Ira Gershwin, who, unlike Porter, only wrote lyrics, exemplified the five essential points of poetry: words; wide-ranging subject matter; imagery; symbolism; and sound effects (alliteration, meter and a myriad of elements that the average listener dismisses as secondary to rhyme. In this, we understand why rap's gangsta days seem so trivial, even comical, while hip-hop in 2018 wins the Pulitzer Prize). Here's an example from Gershwin: "There is somebody I'm longing to see,/ I hope that she/ turns out to be,/ Someone to watch over me" – incredible rhyme, wonderful interpolation of sounds, fabulous meter.

Despite the image of loud guitars, pounding drums and incomprehensible vocals, great rock music starts with lyrics. The other elements of rock music shape themselves around the words, extending and strengthening them. People sometimes argue that the words in rock songs can't be all that important, because they are often so hard to decipher or even to hear. Yet there is a holographic quality to great art, in that the message of a piece is embedded in the whole of the work. Take REM, for instance (or in the extreme, Cocteau Twins). The lyrics at times are incomprehensible. "Swan Swan H" contains remarkable lyrics that no one (not even the rain) can fully understand.

Swan, swan, hummingbird

Swan, swan, hummingbirdHurrah we are all free now

What noisy cats are we

Girl and dog he bore his cross

A long low time ago people talk to me

Johnny Reb what's the price of fans

Forty a piece or three for one dollar?

Hey captain don't you want to buy

Some bone chains and toothpicks?

Poignancy in the guise of gibberish. Oh, don't think that I’ll sit here and decipher its meaning as a whole; remember that it's words + meter + subject matter + symbolism +… The song represents confusion, particularly of a young man growing up in the South with grand stories of Johnny Reb's heroics, a conflict enmeshed in a young man's southern outlook. We grow up with our heroes and down, crashing, they come.

The tune's incredible rhetoric and pace make for glorious poetry. Thoughts negating thoughts, words cut short like great filmmaking in which dialogue, you know, like real life, overlaps, is filled with cutoffs and incomplete sentences – it can indeed be disconcerting. The song defies clarity, even though such confusion is commonplace in our real speech.

Dylan avoided such an avant-garde approach to concentrate on subject, initially writing protest songs about political and social issues, but then transitioning to very personal subjects. Once he demonstrated the possibilities, others followed. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's Déjà vu is the perfect example. On this one collection we find songs about passing wisdom from one generation to the next ("Teach Your Children"), the importance of nonconformity ("Almost Cut My Hair"), the inability to escape one's past ("Helpless"), the nature of the emerging counter-culture ("Woodstock"), an almost suicidal expression of despair ("4 + 20") and simple domesticity ("Our House"), elements that make the primary mode of appreciation for the art form more akin to poetry. Words are used to encapsulate, preserve and amplify a particular experience, sensation, thought or feeling. In the space of a few verses and a chorus, just enough is said to convey the intended meaning.

The perfect example of rock poetry as storytelling is found in Bruce Springsteen's earliest work and again, in a song that could be considered the ultimate in storytelling, "The River." Springsteen's sister Ginny became pregnant at age 18 and quickly married her child's father, Mickey Shave, who took a construction job to support his family. "They had to struggle very hard back in the late Seventies like so many people are doing today," Springsteen said. He turned their story into his most moving working-class lament, a slow, sparse ballad with a mournful harmonica that sounds a bit like a funeral dirge. "Every bit of it was true," Ginny told Springsteen biographer Peter Ames Carlin. "And here I am, completely exposed. I didn't like it at first – but now it's my favorite song." Those words may sum up rock lyrics as poetry: "completely exposed."

Then I got Mary pregnant

And man that was all she wrote

And for my nineteenth birthday

I got a union card and a wedding coat

We went down to the courthouse

And the judge put it all to rest

No wedding day smiles, no walk down the aisle

No flowers, no wedding dress

Funny, all the dreams of "Born to Run" are shattered in those lyrics. They're not, by any means, as beautiful as "Born to Run" – or maybe they are but they're stripped of their fancy. They are sad instead of hopeful, the end, rather than the beginning, there are no dreams, only memories of that short-lived time down by the river. Ho-hum.

Over the next few posts we will explore rock music as poetry, from Springsteen to Prefab Sprout, from Joni to Graham, from Paul Simon to T.S. Eliot.

Published on May 03, 2018 06:00