R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 52

December 5, 2018

It's a Beautiful Day

San Francisco psychedelic folk-rock found a host in It's a Beautiful Day, primarily the vehicle of virtuoso violinist David LaFlamme. Beginning his musical education at age five, LaFlamme would early on serve as a soloist with the Utah Symphony; he was only 21 years old. After relocating to the Bay Area in late 1962, he immersed himself in the local underground music scene, jamming alongside Jerry Garcia and Janis Joplin. After a short-lived stint with a band he called Electric Chamber Orchestra, LaFlamme co-founded Dan Hicks & His Hot Licks before assembling It's a Beautiful Day in mid-1967.

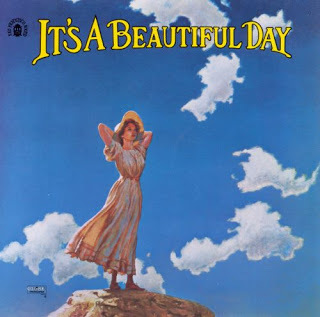

San Francisco psychedelic folk-rock found a host in It's a Beautiful Day, primarily the vehicle of virtuoso violinist David LaFlamme. Beginning his musical education at age five, LaFlamme would early on serve as a soloist with the Utah Symphony; he was only 21 years old. After relocating to the Bay Area in late 1962, he immersed himself in the local underground music scene, jamming alongside Jerry Garcia and Janis Joplin. After a short-lived stint with a band he called Electric Chamber Orchestra, LaFlamme co-founded Dan Hicks & His Hot Licks before assembling It's a Beautiful Day in mid-1967. The group, which included LaFlamme (Flute, Violin, Vocals), keyboardist wife Linda (Organ, Piano, Celeste, Harpsichord, Keyboards), vocalist Pattie Santos, guitarist Hal Wagenet, bassist Mitchell Holman, and drummer Val Fuentes, released its self-titled debut LP on Columbia in 1969, scoring their biggest "hit," so to speak, with the haunting FM radio staple "White Bird." Linda LaFlamme left It's a Beautiful Day soon after, going on to form Titus' Mother; keyboardist Fred Webb signed on for the follow-up, 1970's Marrying Maiden, while Holman exited prior to 1971's Choice Quality Stuff, recorded with new guitarist Bill Gregory and bassist Tom Fowler. In 1973, ongoing disputes over royalties forced LaFlamme out of the group he created – though, quite honestly, none of that really matters. All that matters is It's a Beautiful Day's one, nearly flawless psychedelic LP (note the use of "psychedelic" as a codicil to "flawless").

While the name remains one of the clunkiest in music (indeed the band's name may be the only complete sentence in rock), it was often cause for confusion: was it the name of a band, a song, a forecast, though it indeed gave a distinct impression of the middle earth kind of ethereal feel of the band’s music.

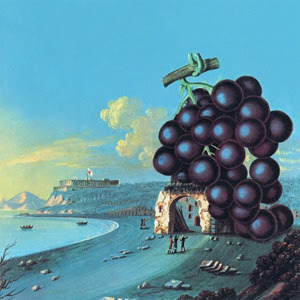

The artwork for Moby Grape's Wow had a similar feel.A short rundown: "White Bird," their most (read that as "only") famous track is one of the most beautiful melodies in rock, offering a strange sadness that opens with a pizzicato passage on the violin and harmonies that don't quite work (kind of like bad Renaissance). "Hot Summer Day" has a bit of an edge to it, though in a lilting minor key. "Wasted Union Blues" begins with a nasty little guitar in a psychedelic blues number about being strung out. "Girl with No Eyes," which may vie with "White Bird" for its lovely melody, is a paradoxical track about a poster on the wall with lyrics that may provide some insight to the band's psychedelia: "She's just a reflection of all the times I've been high." "Bombay Calling" is an instrumental with an Indian feel, building from a short catchy riff to a rock tune. "Bulgaria" is a mysteriously dark tract that's something like a religious rite of passage, and "Time Is" is an uptempo closer about time's relativity. The eponymous debut is far from an AM10, but still serves alongside psychedelic classics like Blue Cheer's Vincebus Eruptum or Moby Grape's Wow, and provided, like Zappa and the Mothers, an American taste of early progressive rock. "White Bird," of course (and the LPs cover art), is worth the price of admission, as is LaFlamme's flawless violin.

The artwork for Moby Grape's Wow had a similar feel.A short rundown: "White Bird," their most (read that as "only") famous track is one of the most beautiful melodies in rock, offering a strange sadness that opens with a pizzicato passage on the violin and harmonies that don't quite work (kind of like bad Renaissance). "Hot Summer Day" has a bit of an edge to it, though in a lilting minor key. "Wasted Union Blues" begins with a nasty little guitar in a psychedelic blues number about being strung out. "Girl with No Eyes," which may vie with "White Bird" for its lovely melody, is a paradoxical track about a poster on the wall with lyrics that may provide some insight to the band's psychedelia: "She's just a reflection of all the times I've been high." "Bombay Calling" is an instrumental with an Indian feel, building from a short catchy riff to a rock tune. "Bulgaria" is a mysteriously dark tract that's something like a religious rite of passage, and "Time Is" is an uptempo closer about time's relativity. The eponymous debut is far from an AM10, but still serves alongside psychedelic classics like Blue Cheer's Vincebus Eruptum or Moby Grape's Wow, and provided, like Zappa and the Mothers, an American taste of early progressive rock. "White Bird," of course (and the LPs cover art), is worth the price of admission, as is LaFlamme's flawless violin. The LPs cover is often more recognizable than what the album contains. It was painted by Kent Hollister (no information) who based his painting on "Woman on the Top of a Mountain," painted in 1912 by American artist Charles Courtney Curran.

The LPs cover is often more recognizable than what the album contains. It was painted by Kent Hollister (no information) who based his painting on "Woman on the Top of a Mountain," painted in 1912 by American artist Charles Courtney Curran.An aside uncharacteristic of AM, e.g. the small print: To throw in a bit of controversy if you've never heard the band (and most of you will note that these kinds of conspiracies are mostly poppycock), simply listen to Deep Purple's "Child in Time," which, to IABD fans, is better known as "Bombay Calling," which LaFlamme first started writing with Electric Chamber Orchestra (sometimes known as Orkustra) in 1965. Though the melodies are similar, no lawsuit or claims were ever made by LaFlamme, who was advised that Deep Purple’s version was dissimilar in more ways than it was similar and included extensive lyrics that become the track’s focal point. (More interesting if you’re looking for scandal, Orkustra member, Bobby Beausoleil, left the band to star in controversial filmmaker Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising before becoming involved in the Manson Family. He is now serving a life sentence in a psychiatric medical facility for the murder of Gary Hinman. Beausoleil would write "Political Piggy" on Hinman’s wall in his own blood.)

There is a similarity as well in Curran's clouds.

There is a similarity as well in Curran's clouds.

Published on December 05, 2018 04:45

December 2, 2018

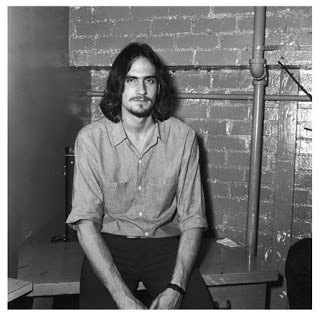

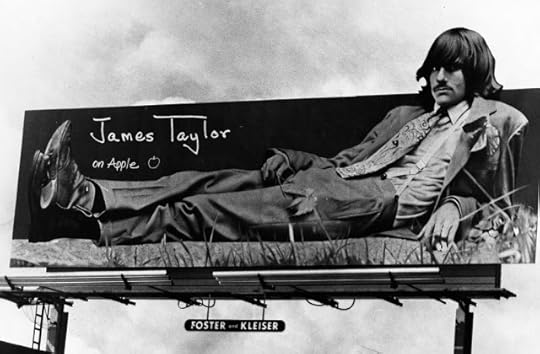

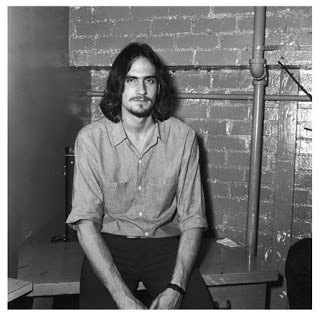

James Taylor - 50 Years Ago

For recovering addicts, moving to another locale to escape the confines of substance abuse is called a "geographic cure." That the case or dumb luck, James Taylor, battling an addiction to heroin, was probably looking for that geographic cure when he moved to London in 1968. The young singer-songwriter had a lot to prove. He'd come from a wealthy and talented family: his mother a classically trained soprano and his siblings – Livingston, Alex and Kate – were finding various degrees of success in popular music. At 15 he became friends with Danny "Kootch" Kortchmar and the two formed a band that would eventually become The Flying Machine. However, JT's musical progress was interrupted when, at 17, he committed himself to a mental hospital in Massachusetts for treatment of depression. When he was released, he said, "I got involved in 'junk.'"

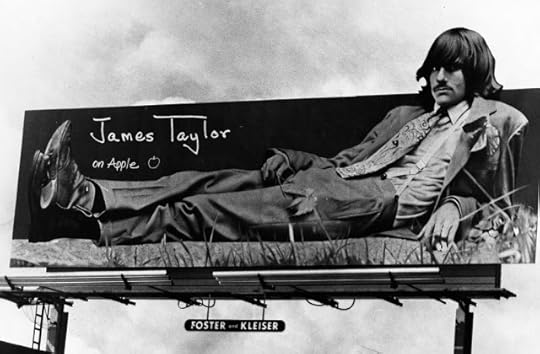

One of My Father's Billboards

One of My Father's Billboards

When he arrived in London, Taylor's friendship with Kootch was his ticket to ride to audition for Peter Asher, of Peter & Gordon fame. Asher was then an A&R rep for the fledgling Beatles record label, Apple. While the Beatles were still under contract to EMI and Capitol Records, Apple Records had big plans to sign other artists and James would become the first non-British act to be signed by Apple.

With Asher producing, the album was recorded from July to October 1968, at Trident Studios, the same time The Beatles were recording The White Album at EMI (Abbey Road). Paul McCartney played bass and her and George Harrison provided back-up vocals on the album's single, "Carolina In My Mind." For the song "Something in the Way She Moves," Taylor wanted to title the song "I Feel Fine," after a dominant line in the chorus. That title was taken, of course, by The Beatles. And everyone knows the first line to the George Harrison song, "Something," from The Beatles' Abbey Road ("Something" was also taken). So, "Thanks, James," said George, though who borrowed from whom is a mystery.

With Asher producing, the album was recorded from July to October 1968, at Trident Studios, the same time The Beatles were recording The White Album at EMI (Abbey Road). Paul McCartney played bass and her and George Harrison provided back-up vocals on the album's single, "Carolina In My Mind." For the song "Something in the Way She Moves," Taylor wanted to title the song "I Feel Fine," after a dominant line in the chorus. That title was taken, of course, by The Beatles. And everyone knows the first line to the George Harrison song, "Something," from The Beatles' Abbey Road ("Something" was also taken). So, "Thanks, James," said George, though who borrowed from whom is a mystery.

The critical reaction to James Taylor was positive, but the LP didn't sell, in part due to Taylor's hospitalization for drug addiction: "I kicked junk for about a half a year and then spent a while in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. I was clean. Then I started to take a lot of codeine. I went to Europe and started to take opium and then got into smack heavy for about nine months. I got into it real thick there. I came back to this country and kicked…"

Management changes at Apple were in the wind by the time of the LP's release. A bad guy, (Beatles' lore is seeded with bad guys) who'd ripped off The Rolling Stones would reappear in the Beatles inner sanctum, and Taylor's fate was sealed. Allen Klein had manipulated the band into signing over the copyrights of all Rolling Stones songs recorded before 1971. (A messy 17-year legal battle was won by Klein, which Keith Richards called "the price of an education.") In 1969, Allen Klein became Apple's president, based on his three-to-one support from the Beatles, Paul McCartney being the only group member to oppose his involvement. McCartney's subsequent withdrawal from Apple decision-making would give Klein free rein to purge the label of alleged antagonists. Peter Asher, the brother of Paul's at the time girlfriend, Jane, was let go, and Taylor followed him out the door.

Management changes at Apple were in the wind by the time of the LP's release. A bad guy, (Beatles' lore is seeded with bad guys) who'd ripped off The Rolling Stones would reappear in the Beatles inner sanctum, and Taylor's fate was sealed. Allen Klein had manipulated the band into signing over the copyrights of all Rolling Stones songs recorded before 1971. (A messy 17-year legal battle was won by Klein, which Keith Richards called "the price of an education.") In 1969, Allen Klein became Apple's president, based on his three-to-one support from the Beatles, Paul McCartney being the only group member to oppose his involvement. McCartney's subsequent withdrawal from Apple decision-making would give Klein free rein to purge the label of alleged antagonists. Peter Asher, the brother of Paul's at the time girlfriend, Jane, was let go, and Taylor followed him out the door.

James Taylor is a tour de force in one respect: it is pure, unadulterated James at 19 years of age. While Mud Slide Slim and Gorilla, show the artist in his prime, and Hourglass displays the incredible maturity of life experience, this is young James, the hangin' around with Joni and Mama Cass James, the Laurel Canyoner who had to get away from L.A., city of the fallen angels.

One of My Father's Billboards

One of My Father's BillboardsWhen he arrived in London, Taylor's friendship with Kootch was his ticket to ride to audition for Peter Asher, of Peter & Gordon fame. Asher was then an A&R rep for the fledgling Beatles record label, Apple. While the Beatles were still under contract to EMI and Capitol Records, Apple Records had big plans to sign other artists and James would become the first non-British act to be signed by Apple.

With Asher producing, the album was recorded from July to October 1968, at Trident Studios, the same time The Beatles were recording The White Album at EMI (Abbey Road). Paul McCartney played bass and her and George Harrison provided back-up vocals on the album's single, "Carolina In My Mind." For the song "Something in the Way She Moves," Taylor wanted to title the song "I Feel Fine," after a dominant line in the chorus. That title was taken, of course, by The Beatles. And everyone knows the first line to the George Harrison song, "Something," from The Beatles' Abbey Road ("Something" was also taken). So, "Thanks, James," said George, though who borrowed from whom is a mystery.

With Asher producing, the album was recorded from July to October 1968, at Trident Studios, the same time The Beatles were recording The White Album at EMI (Abbey Road). Paul McCartney played bass and her and George Harrison provided back-up vocals on the album's single, "Carolina In My Mind." For the song "Something in the Way She Moves," Taylor wanted to title the song "I Feel Fine," after a dominant line in the chorus. That title was taken, of course, by The Beatles. And everyone knows the first line to the George Harrison song, "Something," from The Beatles' Abbey Road ("Something" was also taken). So, "Thanks, James," said George, though who borrowed from whom is a mystery.The critical reaction to James Taylor was positive, but the LP didn't sell, in part due to Taylor's hospitalization for drug addiction: "I kicked junk for about a half a year and then spent a while in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. I was clean. Then I started to take a lot of codeine. I went to Europe and started to take opium and then got into smack heavy for about nine months. I got into it real thick there. I came back to this country and kicked…"

Management changes at Apple were in the wind by the time of the LP's release. A bad guy, (Beatles' lore is seeded with bad guys) who'd ripped off The Rolling Stones would reappear in the Beatles inner sanctum, and Taylor's fate was sealed. Allen Klein had manipulated the band into signing over the copyrights of all Rolling Stones songs recorded before 1971. (A messy 17-year legal battle was won by Klein, which Keith Richards called "the price of an education.") In 1969, Allen Klein became Apple's president, based on his three-to-one support from the Beatles, Paul McCartney being the only group member to oppose his involvement. McCartney's subsequent withdrawal from Apple decision-making would give Klein free rein to purge the label of alleged antagonists. Peter Asher, the brother of Paul's at the time girlfriend, Jane, was let go, and Taylor followed him out the door.

Management changes at Apple were in the wind by the time of the LP's release. A bad guy, (Beatles' lore is seeded with bad guys) who'd ripped off The Rolling Stones would reappear in the Beatles inner sanctum, and Taylor's fate was sealed. Allen Klein had manipulated the band into signing over the copyrights of all Rolling Stones songs recorded before 1971. (A messy 17-year legal battle was won by Klein, which Keith Richards called "the price of an education.") In 1969, Allen Klein became Apple's president, based on his three-to-one support from the Beatles, Paul McCartney being the only group member to oppose his involvement. McCartney's subsequent withdrawal from Apple decision-making would give Klein free rein to purge the label of alleged antagonists. Peter Asher, the brother of Paul's at the time girlfriend, Jane, was let go, and Taylor followed him out the door.James Taylor is a tour de force in one respect: it is pure, unadulterated James at 19 years of age. While Mud Slide Slim and Gorilla, show the artist in his prime, and Hourglass displays the incredible maturity of life experience, this is young James, the hangin' around with Joni and Mama Cass James, the Laurel Canyoner who had to get away from L.A., city of the fallen angels.

Published on December 02, 2018 06:35

December 1, 2018

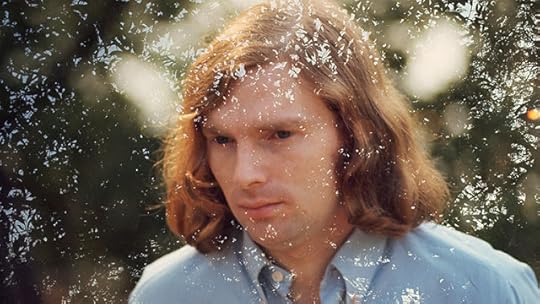

That's When Van Morrison Walked Through the Door

The big Irishman looked like someone who could get pissed off really quick, but I don’t know, I didn’t talk to him. Chadwick said he was a pretty normal guy, he just drank too much.

The big Irishman looked like someone who could get pissed off really quick, but I don’t know, I didn’t talk to him. Chadwick said he was a pretty normal guy, he just drank too much. His set was a collection of tight, radio-friendly soul with a cracker-jack, spot-on band. He did songs I wouldn’t call hits, but I’d heard them on the radio: “Moondance” and “Domino” and “Brown-Eyed Girl.” The best song was a killer track called “Into the Mystic.” “Born before the wind,” he sang, “oh so younger than the sun.” Then he sailed his “bonny boat” into this sublime metaphysical harbor. It was pretty Irish, let me tell you.

The set was top-notch, and although it didn’t resonate with me the way that Cat Stevens or Neil Young did, I’d remember that night for the rest of my life, mostly because of the scar I’d wear over my eye. It was tiny, but a battle scar nonetheless. I’m kind of proud of it.

It was during a lengthy jam that a beer bottle flew from out of the audience. It careened rather harmlessly off an amp and onto the floor, but the guitar player flew into the audience. I figure he saw who threw it and his Irish temper and the alcohol got to him. The two of them faced off until the guitarist caught him with an elbow, and down the guy went. It would have ended there, but people intervene, it’s what they do, and a brawny guy who looked like a troll with a big head and big hands smacked the guitarist in the face and laid him flat. Then it was Van’s turn; he was bigger than everybody and soon there was a regular drunken brawl.

It was then I got hit in the forehead with a Coors bottle; there was shit flying everywhere. When the police came, there were guys slugging it out on the sidewalk, a real moondance, and a marvelous night for it. There were half a dozen cop cars and twice as many brawlers in handcuffs when it was over. I saw Van Morrison and the band hightail it out the back.

To say the least, there was a bit more cleanup than usual. The bartender bandaged my head. She said I’d probably need stitches, but I declined, and as she bandaged me up, I got a pretty nice glance down her top. Chadwick would have been proud; you know, in the face of adversity and all.

Despite the fracas, there wasn’t anything really in the way of damage, just broken bottles and a real mess. It took us most of the night to get things back to Chadwick’s specs. He said, “Now you got somethin’ to write about.”

R.J. Stowell, the author of Jay and the Americans, has a new novel on its way that celebrates the Woodstock era. Miles From Nowhere is scheduled for publication in February 2019, just in time for Woodstock's 50th anniversary in July. R.J. is working on the gallies as we speak and also writing the novel's follow-up, Calif. Today's post was a clip from that novel.

Published on December 01, 2018 06:43

November 30, 2018

Blowin' Your Mind on TB Sheets - Van Morrison and the Astral Weeks

I was never a Van Morrison fan. I should be, it only fits, but oddly, the first single I ever bought with my own money was Them's "Here Comes the Night." I was under the impression when I went to the record store with my Grandmother that I was after The Rolling Stones. (I was like five, what do you want?) While it remained in the stack of singles on my 45 turntable as a part of my go-to collection, I subsequently proceeded to forget about it, only rediscovering the tune with Bowie's frightening cover on 1973's Pin-ups LP.

I was never a Van Morrison fan. I should be, it only fits, but oddly, the first single I ever bought with my own money was Them's "Here Comes the Night." I was under the impression when I went to the record store with my Grandmother that I was after The Rolling Stones. (I was like five, what do you want?) While it remained in the stack of singles on my 45 turntable as a part of my go-to collection, I subsequently proceeded to forget about it, only rediscovering the tune with Bowie's frightening cover on 1973's Pin-ups LP. My brother bought Morrison's debut LP, Blowin' Your Mind, and unlike the brunt of his collection, I played Side One once and put it back on the shelf. He'd storm into my room looking for The Moody Blues, The Mothers, even Switched On Bach, but never once did he have to seek out Blowin' Your Mind. (Interestingly, Van Morrison doesn't consider this LP among his canon of music; Bert Berns, the LPs producer, released it without Morrison's consent or input.) I found it the other day in the budget section of a record shop, and I figure now that maybe the six year old me was wrong, at least to a degree. Still not a "Brown-eyed Girl" fan (nor do I take to "Domino," Morrison’s biggest hit), the remainder of Side One is stellar insightful blues with unmatched session players who wouldn't play second fiddle to The Wrecking Crew (Eric Gale, Al Gorgoni, and Hugh McCracken lay down what are quite possibly the best rhythm guitar tracks ever! Russ Savakus played bass, Paul Griffin played piano, and Gary Chester, drums. Those heavenly back-up singers were The Sweet Inspirations, made up of Myrna Smith, Estelle Brown, Sylvia Shemwell, and Cissy Houston, mother of Whitney and Dionne Warwick's aunt.

My brother bought Morrison's debut LP, Blowin' Your Mind, and unlike the brunt of his collection, I played Side One once and put it back on the shelf. He'd storm into my room looking for The Moody Blues, The Mothers, even Switched On Bach, but never once did he have to seek out Blowin' Your Mind. (Interestingly, Van Morrison doesn't consider this LP among his canon of music; Bert Berns, the LPs producer, released it without Morrison's consent or input.) I found it the other day in the budget section of a record shop, and I figure now that maybe the six year old me was wrong, at least to a degree. Still not a "Brown-eyed Girl" fan (nor do I take to "Domino," Morrison’s biggest hit), the remainder of Side One is stellar insightful blues with unmatched session players who wouldn't play second fiddle to The Wrecking Crew (Eric Gale, Al Gorgoni, and Hugh McCracken lay down what are quite possibly the best rhythm guitar tracks ever! Russ Savakus played bass, Paul Griffin played piano, and Gary Chester, drums. Those heavenly back-up singers were The Sweet Inspirations, made up of Myrna Smith, Estelle Brown, Sylvia Shemwell, and Cissy Houston, mother of Whitney and Dionne Warwick's aunt.In particular is the epic "TB Sheets." It's the tale of a man stuck in the room of a dying friend "And I can almost smell your TB Sheets," he sings, and sniffs the air "on your sick-bed." At more than nine-and-a-half minutes, it is a song that doesn't so much play as ooze, that winds you up in a feverish, Otis Redding-style delirium, with a groggy-sounding organ, a raving harmonica and a tambourine that sounds like a rattlesnake. Lester Bangs (you know I'm not much of a fan) said, "In TB Sheets, his last extended narrative before making Astral Weeks, Van Morrison watched a girl he loved die of tuberculosis. The song was claustrophobic, suffocating, monstrously powerful 'innuendos, inadequacies, an' foreign bodies'."

On symbolism, the unparalleled Irish poet, William Butler Yeats said, "The purpose of rhythm, it has always seemed to me … is to prolong the moment of contemplation … by hushing it with an alluring monotony." (Hold on to that notion...)

On symbolism, the unparalleled Irish poet, William Butler Yeats said, "The purpose of rhythm, it has always seemed to me … is to prolong the moment of contemplation … by hushing it with an alluring monotony." (Hold on to that notion...)I'm thinking back to my youth, sneaking into my brother's room to snag Blowin' Your Mind. It was the fall of 1967, a rainy day in L.A., and two songs into Side One an eerie dirge about death and disease spun cheerlessly on the hi-fi. "T.B. Sheets" was hypnotic blues sung from the point of view of a young man spooked by his lover wasting away from tuberculosis. Modern in sound, it looked backward for content, mining a centuries-old motif that by the mid-60s was fading from historical reality – the dying loved one, stricken with incurable, infectious disease, and the accompanying bedside vigil (today we'd merely look back to the AIDS pandemic).

This it did with harrowing intensity. Countless songs, books, and films tell of lovers parted by premature death and the attendant sorrow of partners left behind, but "T.B. Sheets" stands out for its oppressive ambiance and the inner turmoil of its anguished yet unheroic protagonist. Dying lover narratives often portray surviving partners as heartbroken paragons, steadfast and true, but Morrison’s narrator is all too shamefully human: unable to cope with his lover's illness and approaching death, he comforts himself with false promises and abandons her. Woah.

"Now listen, Julie baby

It ain’t natural for you to cry in the midnight

It ain’t natural for you to cry way in the midnight through

Into the wee small hours long before the break of dawn

Oh Lord"

Pretty Yeatsean, eh?

Tucked halfway through an LP that opened with the jaunty "Brown-Eyed Girl" – one of the era's sunniest songs and a hit single the previous spring – "T.B. Sheets" no doubt shocked listeners expecting an album's worth of "Sha-la-la, la-la, la-la, la-la, l'la-te-da." Harrowing and hopeless, the song's stark realism rested uneasily next to groovier fare in the season of Sgt. Pepper. Only the Doors’ gloomy debut and the little-noticed (at the time) Velvet Underground & Nico were on a similar wavelength. I find myself a little like Lester Bangs here; I was wrong.

With a debut that rivaled the songwriting of Bob Dylan, one would think the next offering would simply produce itself. It did not. Contractural disputes with Bang Records following the label's founder's death barred Morrison from entering the studio, though he was still under contract, and that conflict kept club and venue owners from booking the band. Crazy that we almost didn't get Astral Weeks.

My wife and I only recently returned home from Ireland. Imagine a day trip on a bus to the Giant's Causeway and then deep into the real Ireland. After an eye-opening tour of "The Troubles" that was immensely disturbing and downright frightening, you head off to the gorgeous northern coast. It's a nice, sunny, cool afternoon. We stopped off at a pub in an out-of-the-way town for a late, leisurely lunch. There's a stage in the corner with no one playing, but in the background is Astral Weeks. We're lulled into a tranquil mood by the beautiful, soulful, melodious songs like we'd never heard them before. The songs aren't "polished" in the usual sense, and sound almost improvised; the lyrics vague and abstract. Lunch over, you climb back on the bus and head home. The moment is over but the effect leaves an ethereal, warm memory and a happy glow from the beautiful moment in time and space you've just witnessed.

Sentimental? You bet. Astral Weeks was released 50 years ago today, but my wife and I rediscovered it like it was brand new.

Published on November 30, 2018 05:46

November 29, 2018

Can't get enough of AM? - How About AM Radio?

AM has been going strong now for more than four years. Thanks to our loyal readers, we've been able to present modern music in a positive format that allows us to wallow in the history of rock music from the mid-60s to today. We're taking another step now by bringing AM to the radio. Check us out at

Daybreak USA

where twice per week you can catch our five-minute broadcast as a part of Daybreak with Rodd and Rae. The new radio segment will highlight the 50th anniversaries of the music we love. 50 years ago we wore fringed leather jackets or go-go boots made for walkin' and it was the time and the season for loving. Stereotypes aside (not that we don't relish in our stereotypes), join us each week to relive 1968 and AM on the Radio.

AM has been going strong now for more than four years. Thanks to our loyal readers, we've been able to present modern music in a positive format that allows us to wallow in the history of rock music from the mid-60s to today. We're taking another step now by bringing AM to the radio. Check us out at

Daybreak USA

where twice per week you can catch our five-minute broadcast as a part of Daybreak with Rodd and Rae. The new radio segment will highlight the 50th anniversaries of the music we love. 50 years ago we wore fringed leather jackets or go-go boots made for walkin' and it was the time and the season for loving. Stereotypes aside (not that we don't relish in our stereotypes), join us each week to relive 1968 and AM on the Radio.

Published on November 29, 2018 15:08

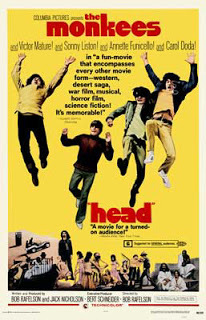

Rock Cinema - Head

The genesis of Head, the only theatrical production by The Monkees, was a lost weekend in 1968 when The Monkees, Bob Rafelson and B-movie actor Jack Nicholson, turned on a tape recorder and took turns tossing ideas about. The ill-fated film got off on the wrong foot from the first day of filming on February 11, 1968, including a rock-bottom budget of $750,000.

The genesis of Head, the only theatrical production by The Monkees, was a lost weekend in 1968 when The Monkees, Bob Rafelson and B-movie actor Jack Nicholson, turned on a tape recorder and took turns tossing ideas about. The ill-fated film got off on the wrong foot from the first day of filming on February 11, 1968, including a rock-bottom budget of $750,000.The cast was hellishly eclectic and included Annette Funicello, boxer Sonny Liston, Frank Zappa, a teen-aged Terri Garr and the Radio City Rockettes. Veteran actor Victor Mature signed on after reading the script: "All I know is, it made me laugh." Mature's character in Head was "the Big Victor," a jab at RCA Victor, the distributor for Colgems which owned and aired the TV show. Even Jack Nicholson and Dennis Hopper made brief cameos.

The film had no opening credits but opens with what could be considered an early music video, the Goffin-King penned "Porpoise Song." The film quickly morphs from there into what many describe as something resembling an "acid trip;" the basic premise of which was the Monkees unmaking their clean-cut TV images. In one scene, the Monkees walk into the studio commissary and a cattle stampede rushes out. In real life, many performers disliked The Monkees and would deliberately walk out of the studio commissary when the boys entered.

In many scenes, only three Monkees appear on screen, a reference to "see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil." A few Beatles references are thrown in, as well. In one scene, Ringo Starr is mentioned. In another, Peter Tork whistles "Strawberry Fields Forever" as he walks into the restroom.

In many scenes, only three Monkees appear on screen, a reference to "see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil." A few Beatles references are thrown in, as well. In one scene, Ringo Starr is mentioned. In another, Peter Tork whistles "Strawberry Fields Forever" as he walks into the restroom. Even some of the end credits of Head boggle the mind, which were printed backward as the "reversed" cast, i.e. Srebmahc Yrret as Oreh (Terry Chambers as Hero) and Revaew Adnil as Yraterces Revol (Linda Weaver as Lover Secretary).

Toward the end of production, Jack Nicholson was at the studio where he encountered Mike Nesmith working on the Head soundtrack. Jack asked if he could help, and to his surprise, Nesmith turned the whole thing over to Nicholson, saying "I just want to go home." Production wrapped on May 21, 1968, and a disastrous preview took place in Los Angeles, causing the filmmakers to cut the one hour 50 minute film to just 86 minutes.

Toward the end of production, Jack Nicholson was at the studio where he encountered Mike Nesmith working on the Head soundtrack. Jack asked if he could help, and to his surprise, Nesmith turned the whole thing over to Nicholson, saying "I just want to go home." Production wrapped on May 21, 1968, and a disastrous preview took place in Los Angeles, causing the filmmakers to cut the one hour 50 minute film to just 86 minutes. The World Premiere occurred Wednesday, November 6, 1968 in Manhattan; a gala was held at Columbia Pictures Studio on West 54th Street attended by The Monkees, Janis Ian, Andy Warhol, Boyce and Hart, Carole Bayer, Bert Schneider, Bob Rafelson and Peter Fonda. An invitation-only debut of Head in Los Angeles took place at 8:30pm, Tuesday, November 19, 1968 at The Vogue Theater on Hollywood Blvd., attended by The Monkees, Phyllis Nesmith, Samantha Juste, Cass Elliot and Denny Doherty of The Mamas And The Papas, Boyce and Hart, Dennis Hopper, actor Sonny Tufts, comedy troupe The Committee, Tina Louise, and supporting Head cast members Frank Zappa, Sonny Liston and Annette Funicello. The film was a tremendous box office flop by most standards until it's below budget costs are calculated into the mix.

While A Hard Day's Night hovers within the 100 best films ever made, Head doesn't begin to capture the latent talents of the studio-created boy band, yet retrospectively the film has gained a deserved cult following, is immensely watchable in bits and pieces and caps a Monkee career lauded by everyone from Rivers Cuomo to Billy Corgan, from Piers Morgan to Ringo Starr.

Published on November 29, 2018 05:47

November 26, 2018

Cactus Tree - Joni Mitchell

For several years I worked in a mental health facility. My job as a caseworker and therapist exposed me in a clinical way to the female psyche. Out of that, I was able to write one of my first (as yet unpublished) novels, Unblinking. Written from a troubled woman's point of view, many an agent has asked why I was the most qualified writer for the job.

For several years I worked in a mental health facility. My job as a caseworker and therapist exposed me in a clinical way to the female psyche. Out of that, I was able to write one of my first (as yet unpublished) novels, Unblinking. Written from a troubled woman's point of view, many an agent has asked why I was the most qualified writer for the job. Aside from my experience in the mental health field, much of the little I understand of the female psyche I learned from Joni Mitchell. Though Joni's words aren't emblematic of womanhood, her focus is profoundly female. Her debut LP from 1968, Song to a Seagull, illustrates that voice from a youthful perspective, and while Joni would go on to far finer moments, particularly beginning with Ladies of the Canyon, Songs shows a woman of heart and mind with time on her hands, contemplating the world around her. The LP's, last track, "Cactus Tree," exemplifies that perspective in a way that breaks downs my testosterone-laden perspective.

"Cactus Tree" is a catalog of the singer's ex-lovers. She's new to the city, untethered and liberated, exploiting to the fullest the sexual freedom newly available to the fairer sex circa 1968. The imagery is hippie throughout, the schooners and beads and flowers and harbors. Her endless list of lovers brags of hippie promiscuity. For the first three verses, Joni presents her relationship through the eyes of men who hope to possess her, while she values freedom over commitment.

In verse four, Joni openly "loves them all;" each night, a new good time. Is is love? For the moment. Here Joni's prowess as a writer blossoms as she sings, "She has brought them to her senses" – not their senses – and "They have laughed inside her laughter" revealing that it's all good fun; don’t take it too seriously. "She will love them when she sees them," until she moves on. That kind of honest contradiction has always intrigued me. A line from Prefab Sprout comes to mind: "He swore he'd never leave her; he meant it till he did." Yet this was March 1968—the very dawn of the sexual revolution. Women did not have sex outside marriage, certainly not with innumerable partners, and they certainly didn’t talk about it.

In verse four, Joni openly "loves them all;" each night, a new good time. Is is love? For the moment. Here Joni's prowess as a writer blossoms as she sings, "She has brought them to her senses" – not their senses – and "They have laughed inside her laughter" revealing that it's all good fun; don’t take it too seriously. "She will love them when she sees them," until she moves on. That kind of honest contradiction has always intrigued me. A line from Prefab Sprout comes to mind: "He swore he'd never leave her; he meant it till he did." Yet this was March 1968—the very dawn of the sexual revolution. Women did not have sex outside marriage, certainly not with innumerable partners, and they certainly didn’t talk about it. Joni sings it all with a catch in her voice – second thoughts? Regrets? Despite my experience and insight, I don't know; I'm in too deep. I cannot truly fathom a woman's mind. While I created the psyche of my character in Unblinking, can I really understand her at all?Ultimately, "She only means to please them." Am I reading it wrong; reading too much into it: a man's ultimate goal is to achieve pleasure; a woman’s to give it? It's hardwired into our brains and our psyches and our genitalia, and yet "Her heart is full and hollow like a cactus tree." Who knows if a cactus tree really is full and hollow? Go ask a botanist, but who cares? Joni knows, and all I can do is pretend to.

Published on November 26, 2018 04:06

November 25, 2018

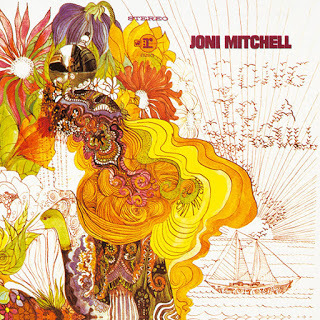

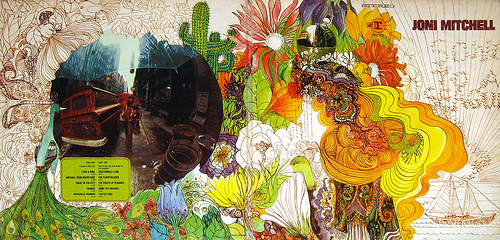

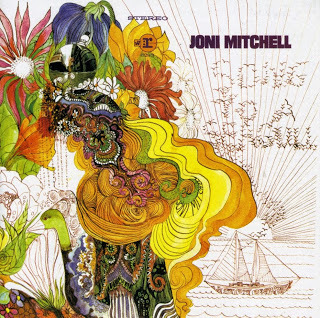

Song To a Seagull - Joni Mitchell

Somehow, David Crosby and Joni Mitchell , along with Elliot Roberts, who Mitchell initially referred to as "Mr. 10 Percent," were able to secure a recording contract that gave the Mitchell complete artistic control (even including the album cover), unheard of at the time, particularly for an unknown. Crosby would go on to be Joni's one and only producer, but his hands-off style was just what Joni was seeking. Crosby's approach was to keep the "rock" out of the production, to keep it a purely folk venture. With that in mind there are only two musicians on the LP, Mitchell and bassist Stephen Stills. The LP has ten songs with two unique sections, "I Came to the City" and "Out of the City and Down to the Seaside."

Somehow, David Crosby and Joni Mitchell , along with Elliot Roberts, who Mitchell initially referred to as "Mr. 10 Percent," were able to secure a recording contract that gave the Mitchell complete artistic control (even including the album cover), unheard of at the time, particularly for an unknown. Crosby would go on to be Joni's one and only producer, but his hands-off style was just what Joni was seeking. Crosby's approach was to keep the "rock" out of the production, to keep it a purely folk venture. With that in mind there are only two musicians on the LP, Mitchell and bassist Stephen Stills. The LP has ten songs with two unique sections, "I Came to the City" and "Out of the City and Down to the Seaside."Joni would tour extensively in 1968 to support the LP and continued to profit from several other artists recording her songs. With her financial success, Joni bought her first home in Laurel Canyon.

The album was well received, though many were put off by the intimacy apparent, an intimacy that to the album's supporters was over the top. Gerry Garcia once said that the Grateful Dead's music was like licorice; that not everyone liked licorice, but those that do, really like licorice. Such was the case with Seagull. Melody Maker's Karl Dallas said of Joni, "Talking to Joni Mitchell about her songs is rather like talking to someone you just met about the most intimate secrets of her life."

The first side of the LP is the "city" side: life in the city, love in the city, dark secrets in the city. The lyrical picture painted isn't one of total despair, in fact, it's multi-sided, but it's definitely bleaker than whatever ensues. The minimalism of the LP’s first side is gorgeous in retrospect, bold in its simplicity, and deceiving. "Night In The City" is the only fully-produced tracks on the album, where Joni is joined by Steve Stills on bass and layers her vocals across the top like a rich sauce. The most fascinating part, though, is the overdub of her own vocal harmonies - the chirping "Night in the CIIITY, night in the CIIITY, looks PRETTY to me" is mesmerizing.

The first side of the LP is the "city" side: life in the city, love in the city, dark secrets in the city. The lyrical picture painted isn't one of total despair, in fact, it's multi-sided, but it's definitely bleaker than whatever ensues. The minimalism of the LP’s first side is gorgeous in retrospect, bold in its simplicity, and deceiving. "Night In The City" is the only fully-produced tracks on the album, where Joni is joined by Steve Stills on bass and layers her vocals across the top like a rich sauce. The most fascinating part, though, is the overdub of her own vocal harmonies - the chirping "Night in the CIIITY, night in the CIIITY, looks PRETTY to me" is mesmerizing. Side two is a blend of imagery and sea shanties with sailing ships, pirates, seagulls, and oceanic longing. "The Pirate Of Penance" and "Song To A Seagull" are really striking; the former a fully-written drama unto itself, once again showcasing Joni's miraculous "duetting with herself", and the latter boasting a certain "majesty of olde" as the lyrics suggest: "My dreams with the seagulls fly, out of reach, out of cry." "Cactus Tree" is for many the LP's star, building on Dylanish lyrics that micic "A Hard Rain". Crosby’s first impressions of Joni aren't lost on the listener.

Note the Error in the Original Release - The LP's Title is Cut Off

Note the Error in the Original Release - The LP's Title is Cut OffWhat was to follow was better and justifiably more successful, but Song To A Seagull has that rarest of things - a level of purity and sincerity in its lyrics and execution that makes it absolutely timeless. So much so that the most successful track (by this writer's estimation), "Night in the City," ends up as an almost uncomfortable distraction from the spellbinding simplicity of what surrounds it. Songs to a Seagull is a seriously under-rated and beautiful LP.

Published on November 25, 2018 04:59

November 24, 2018

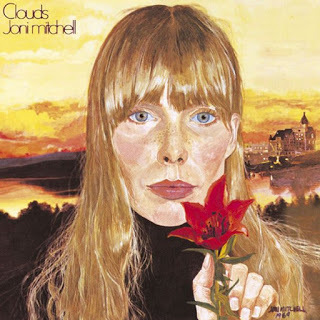

Song to a Seagull and Clouds

Recorded in the midst of the Vietnam War and surrounded by sweeping social changes, Joni Mitchell's 1968 underrated debut, Song to a Seagull (AM7), is an elegant and timeless microcosm. The songs are captivating and complex, drawing the listener into a misty and melancholic realm that fills the cracks between genres: a unique artistry that blends the heartfelt simplicity of folk, the rhythmic, youthful allure of rock and the expansive, detail-mindedness of classical. (Later she would incorporate the improvisational, bonds-loosened feel of jazz as well, not yet.) The sound of the recording is atmospheric and for the most part the music broods, yet Joni is the ultimate storyteller and the characters are portrayed with a strong sense of reality: songs about common relationships, people we may have met, emotions we too may feel or thoughts we may have once pondered. We know straightaway that this is no average songwriter. Joni draws attention to certain lines in circumspect unfamiliar ways. In "Sisotowbell Lane" she takes the melody from the second to the last line of the verse and repeats it on the second to the last line of the chorus: simple complexity. The lyrics are similar, she holds a note on the verse and cuts off one from the chorus. This clipped note sets up for the last line of the chorus. The projected imagery expands from colorful to so vibrantly tactile you can touch it.

Recorded in the midst of the Vietnam War and surrounded by sweeping social changes, Joni Mitchell's 1968 underrated debut, Song to a Seagull (AM7), is an elegant and timeless microcosm. The songs are captivating and complex, drawing the listener into a misty and melancholic realm that fills the cracks between genres: a unique artistry that blends the heartfelt simplicity of folk, the rhythmic, youthful allure of rock and the expansive, detail-mindedness of classical. (Later she would incorporate the improvisational, bonds-loosened feel of jazz as well, not yet.) The sound of the recording is atmospheric and for the most part the music broods, yet Joni is the ultimate storyteller and the characters are portrayed with a strong sense of reality: songs about common relationships, people we may have met, emotions we too may feel or thoughts we may have once pondered. We know straightaway that this is no average songwriter. Joni draws attention to certain lines in circumspect unfamiliar ways. In "Sisotowbell Lane" she takes the melody from the second to the last line of the verse and repeats it on the second to the last line of the chorus: simple complexity. The lyrics are similar, she holds a note on the verse and cuts off one from the chorus. This clipped note sets up for the last line of the chorus. The projected imagery expands from colorful to so vibrantly tactile you can touch it. The album reveals a master at work; not the work of an novice, these aren't the lyrics of a beginner, a flower child or a sophomoric "student" of art, but the uncommon work of a true artist. It's cerebral, beautiful, thought provoking and mature - free of any pretense. Blue, Court and Spark, the jazz albums are Joni’s shining moments, but Song to a Seagull is quietly brooding magic, Joni's marriage of the earthy and the celestial (captured beautifully in David Crosby understated production). Most important is the imagery apparent within the groves; one can see her there in Laurel Canyon at the piano, David Crosby sitting on the couch behind her, Graham Nash at the dining table scribbling the lyrics to "Our House," the smell of eucalyptus in the air.

The album reveals a master at work; not the work of an novice, these aren't the lyrics of a beginner, a flower child or a sophomoric "student" of art, but the uncommon work of a true artist. It's cerebral, beautiful, thought provoking and mature - free of any pretense. Blue, Court and Spark, the jazz albums are Joni’s shining moments, but Song to a Seagull is quietly brooding magic, Joni's marriage of the earthy and the celestial (captured beautifully in David Crosby understated production). Most important is the imagery apparent within the groves; one can see her there in Laurel Canyon at the piano, David Crosby sitting on the couch behind her, Graham Nash at the dining table scribbling the lyrics to "Our House," the smell of eucalyptus in the air. Song to a Seagull was released March 1, 1968, with production beginning sometime after August 1967, when Joni met David Crosby. Joni's second LP, Clouds (AM7) would not be released until May 1969, a long span for the era, offering her the luxury of time that many new artists weren't granted (standard contracts called for two LPs per year). Among Clouds' ten tracks were her own versions of songs already covered by other artists, including "Chelsea Morning," "Tin Angel," and "Both Sides Now."

Song to a Seagull was released March 1, 1968, with production beginning sometime after August 1967, when Joni met David Crosby. Joni's second LP, Clouds (AM7) would not be released until May 1969, a long span for the era, offering her the luxury of time that many new artists weren't granted (standard contracts called for two LPs per year). Among Clouds' ten tracks were her own versions of songs already covered by other artists, including "Chelsea Morning," "Tin Angel," and "Both Sides Now.""Both Sides Now," written more than a year before it ran up the charts for Judy Collins in 1968, was inspired by Saul Bellow's Henderson the Rain King on a jetliner; in particular, a passage where the main character is traveling by plane looking out over the clouds. The novel includes the line, "we are the first generation to see the clouds from both sides."

Joni's metaphor alluded to how children see clouds from the ground below, concocting fanciful and innocent images, then, as adults find nothing in them but inclement weather – indeed, both sides, the innocence, the trials and tribulations, the judgments of, let’s call it "the moon and the stars." Joni just didn't understand life or love at all. She was 21. Probably still doesn’t.

Other songs on the Clouds LP, mostly written in late 1967 and early '68, deal with love, lovers, unrequited love, the uncertainty of love, you get the point, in tracks like "I Don’t Know Where I Stand," "Tin Angel," "That Song About the Midway," and "The Gallery." But Clouds also includes "The Fiddle and The Drum," a song that compares America during the Vietnam War to a bitter friend, and "I Think I Understand, which is about with mental illness.

In 1969, Joni Mitchell’s Clouds rose to No. 22 on the Canadian chart and No. 31 on the Billboard 200. Mitchell produced all the songs on the album (except for one), played acoustic guitar and keyboards, and was joined by Stephen Stills on bass guitar for just one track. Clouds brought Joni Mitchell a Grammy Award for Best Folk Performance. On Clouds, as well as Song To A Seagull we encounter a woman in a tug of war between innocence and experience. Joni's painterly influence on her compositions is in full evidence on both early LPs, from the Rembrandt browns of "Tin Angel" to the bright golds and yellows of "Chelsea Morning." The experience of innocence: as difficult a concept as the child being father to the man.

Published on November 24, 2018 05:04

November 22, 2018

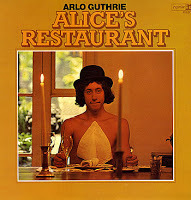

You Can Get Anything You Want...Happy Thanksgiving!

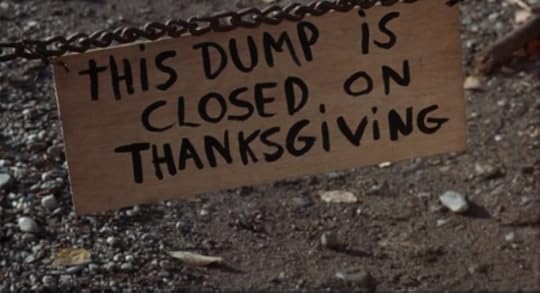

Recorded in 1967, Arlo Guthrie's "Alice's Restaurant," the 18- minute counterculture anthem recounts the storyteller's real-life encounter with the law on Thanksgiving Day 1965. As the song unfolds, we hear all about how a hippie-bating police officer by the name of William "Obie" Obanhein arrested Arlo for littering. (Cultural footnote: Obie previously posed for several Norman Rockwell paintings, including the well-known painting, "The Runaway," that graced a 1958 cover of The Saturday Evening Post.) In fairly short order, Arlo pleads guilty to a misdemeanor charge, pays a $25 fine, and cleans up the trash.

Recorded in 1967, Arlo Guthrie's "Alice's Restaurant," the 18- minute counterculture anthem recounts the storyteller's real-life encounter with the law on Thanksgiving Day 1965. As the song unfolds, we hear all about how a hippie-bating police officer by the name of William "Obie" Obanhein arrested Arlo for littering. (Cultural footnote: Obie previously posed for several Norman Rockwell paintings, including the well-known painting, "The Runaway," that graced a 1958 cover of The Saturday Evening Post.) In fairly short order, Arlo pleads guilty to a misdemeanor charge, pays a $25 fine, and cleans up the trash.  But the story isn't over. Not by a long shot. Later, when Arlo (son of American icon Woody Guthrie) gets called up for the draft, the petty crime ironically becomes a basis for disqualifying him from military service in the Vietnam War.

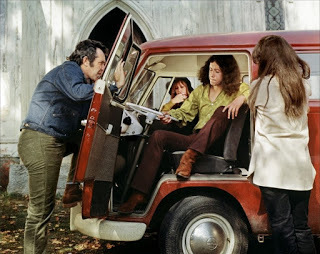

But the story isn't over. Not by a long shot. Later, when Arlo (son of American icon Woody Guthrie) gets called up for the draft, the petty crime ironically becomes a basis for disqualifying him from military service in the Vietnam War. Guthrie recounts this with some bitterness as the song builds into a satirical protest against the war: "I’m sittin' here on the Group W bench 'cause you want to know if I'm moral enough to join the Army, burn women, kids, houses and villages after bein' a litterbug." And then we're back to the cheery chorus again: "You can get anything you want, at Alice's Restaurant." Who would have thought that a Thanksgiving tradition was born. The song would later become the inspiration for the 1969 cult classic film of the same name.

Published on November 22, 2018 08:20