Dan Leo's Blog, page 37

July 7, 2017

The Memoirs of Arnold Schnabel: “misbegotten”

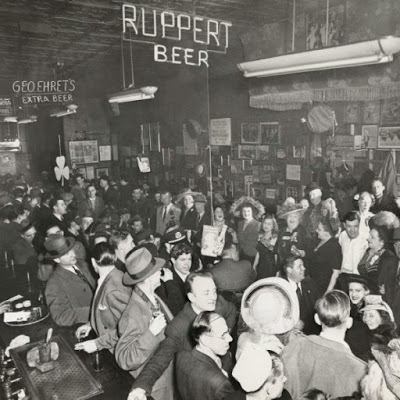

We last saw our hero Arnold Schnabel here in Bob’s Bowery Bar with his new acquaintance “Sid”, otherwise known as Siddhārtha Gautama, or, perhaps more popularly, as the Buddha..

(Kindly click here to read last week’s thrilling episode; if you would like to start at the very beginning of this Gold View Award™-winning 63-volume memoir you may go here to purchase Railroad Train to Heaven: Volume One of the Memoirs of Arnold Schnabel, available both as a Kindle™ e-book or a deluxe large-format softcover actual “book” printed on FSC certified, lead-free, acid-free, buffered paper made from wood-based pulp.)

“Looking for the perfect ‘beach read’ for your summer holidays? What better choice than Arnold Schnabel’s eminently readable and yet strangely profound chef-d'œuvre?” – Harold Bloom, in the Seventeen Literary Supplement.

“The zen way,” said Sid. He really had to rub it in. “What did I tell you? Maybe you ought to try it sometime. I mean, sure, you’re an enlightened chap, very much so, but if you really want to become enlightened you’ve pretty much got to get ‘hip’ as you Americans say to the zen way.”

“Sid.”

“Yes?”

“What did I tell you about how you don’t have to keep saying ‘as you Americans say’.”

“You said I didn’t have to keep saying it.”

“Yes.”

“And is there some point which you are circling your way toward?”

“Yes, my point is you don’t have to keep saying ‘as you Americans say’.”

“But I already know that.”

“Then why do you keep saying it?”

“Because the words rise up from somewhere deep in my brain and fly out of my mouth. Like little birds longing for the freedom of the open sky.”

“Well, can’t you stop them from flying out?”

“I suppose I could. Or I could try. Why?”

“Because it’s annoying.”

“Oh. Why did you not say so?”

“I guess I hoped that you would figure that out yourself.”

“’Hope’. Now there’s another useless concept, right up there with ‘wishing’.”

“Okay, fine,” I said. “You know what, Sid? It’s okay, you can say ‘as you Americans say’.”

“Oh, I know I can.”

“Sid,” I said, after a sigh that was also part grimace, part gulp of despair, “can I ask you a personal question?”

“Of course you can, old boy.”

“Are you consciously trying to be annoying, or does it just come naturally to you?”

“Wow. As you Americans say.”

“Oh, God,” I said.

“Which God?”

“Never mind,” I said.

“In your native slang,” he said, “and I hope you noticed my variation of the formula there –”

“Yeah, thanks, Sid.”

“In your hepcat lingo, ‘Dig it, daddy-o.’ I’ll tell you what, Ernest, if you like I can give you zen instruction.”

“No, thanks.”

“No?”

“No. I’ll take a pass, I think.”

“Oh, but my dear chap, do you know how many millions of human beings would leap at the chance to be instructed by none other than the one and only Siddhārtha Gautama, perhaps more popularly known as the Buddha?”

“A lot I’m sure.”

“Millions.”

“Okay.”

“So let me take you on as a student. It’ll do you good.”

“Again, no, but thanks for the offer, Sid.”

“I’ll give you a very favorable rate.”

“So you’re saying I would have to pay for this, uh, instruction.”

“Well, I have to earn a living, you know. But I’ll give you a really good deal, and after five, ten years of my personal tutelage you just watch, you think you’re enlightened now? Maybe fifteen years it will take, but still.”

“I don’t think so, Sid.”

“Wow, you’re serious.”

“Yes, sorry.”

“Wow, again, in your parlance.”

“Yeah, well –”

“You’re sure?”

“As sure as I’m standing here, Sid, not that I’m all that sure I’m standing here, but if I was sure, that’s how sure I would be.”

“Maybe after you think it over.”

“I don’t have to think it over.”

“After you sleep on it.”

“I could sleep on it a thousand years and my answer would be the same.”

“No?”

“No.”

“No, no wouldn’t be your answer, or no, no would be your answer.”

“No, my answer is no, and my answer would be no from here to eternity and back to the beginning of time. In any possible universe or state of reality my answer would still be no. Even if there was a universe in which the concept of no did not exist, my answer would still be no.”

“So no is your final answer.”

“Yes.”

“Wow. As you would say. Just – wow. But, oh, hey – I just like got it, man. This flash of insight. This very second. Whew.”

“Let’s find my friends, Sid.” Music had started up again, but my trained ear divined that it was the jukebox and not the living musicians. “Come on,” I said, “I’ll buy you a boilermaker.”

“I mean I just this very second got it.”

People were staggering out onto the dance floor again to dance and thrash and flop around to the music. The song was “Beat Me, Daddy, Eight To The Bar”.

“Just now,” said Sid. “It hit me.”

“Oh?” I said.

“Yes, my good chap. I like totally just got it.”

“Great.”

“Like that, all at once.”

I gave in.

“Okay, what did you just get, Sid?”

“You’ve surpassed me. Just, like, wow, is all I can say, I mean in your patois.”

“I’ve surpassed you.”

“Yes, daddy-o. I thought I was the really enlightened one, but, no, you are the really, really enlightened one. And once again, I just want to not only get on my knees before you but prostrate myself.”

“Don’t do that.”

“If you say so. But only if you say so. Because otherwise I’ll do it, and I don’t care how dirty and filthy this floor is. And me in my nice white suit, too. I’ll do it. Gladly.”

“Well, just don’t do it, okay?"

“In fact I wish this floor was even more filthy. More vomit, more human bodily fluids.”

“Okay, that’s enough, Sid.”

“Only if you say so.”

“Well, I’m saying so.”

“Hey, who’s the babe in your parlance?”

“What babe?”

“Coming up right behind you, my good bloke.”

I turned around.

It was Emily. Back for one more round, approaching with a wobbly but determined-looking stride. Almost directly behind her across the room at the bar I saw Julian, swiveled around on his stool and looking towards me, holding a cigarette and a glass in one hand, and with a big smile on his face. I saw that Emily wasn’t carrying that big heavy black purse of hers to clobber me with, so I had that much going for me.

“Who’s the looker?” said Sid.

“Her name is Emily,” I said. “She’s the heroine of the novel we’re in.”

“You must introduce me, old chap.”

“Sure, Sid,” I said, and I waited another second and then she was there.

“Hi, Porter,” she said. “Schmorter. Schlamozzel. Schlemiel.”

“Hi, Emily,” I said.

“Where have you been all night, lover?”

So she had forgotten about our last encounter, perhaps she had forgotten about our last several encounters. With any luck she would forget about this one by tomorrow.

“Oh, I’ve been making the rounds,” I said, the understatement of my lifetime.

“Who’s Mr. Moto here?”

“Oh, this is my friend, uh, Sid. Sid, I’d like you to meet Emily.”

“Very charmed, I’m sure,” said Sid. He bowed, and, picking up her right hand, which hung loose at her side, he kissed it. He let the hand drop, straightened up, smiled.

“Golly,” she said. “First time that’s ever happened to me. Kissed on the hand. And by a little Chinese fella.”

“In truth, Miss Emily,” said Sid. “I hail from the country known to men as Nepal, and more particularly from a lovely little valley called –”

“You,” said Emily, pointing her finger at me. “Avoiding me. What’s the matter, Porter? You mad ‘cause I’m out with Julian?”

“Excuse me,” said Sid, “but may I ask why you address Ernest as Porter? Is it one of your American nicknames, perhaps?”

“I call him Porter because that’s his name, Charlie Chan. Where’d you get this Ernest crap?”

Sid turned and looked up at me. I say looked up because he was very short, shorter even than Emily.

“I thought you said your name was Ernest,” he said.

“Actually I never said that, Sid. But you kept calling me Ernest and I got tired of correcting you.”

“So your name is Porter?”

“Well, in this world it is,” I said.

“What do you mean, in this world?” said Emily.

I saw no need or reason to dissemble with her any longer, and, after all, I suspected also that it didn’t matter a whole lot what I said to her, given her state of advanced drunkenness, or even otherwise.

“I come from another world,” I said. “A world called reality. I know you probably won’t believe this, but my real name is Arnold Schnabel, and I’m stuck in the universe of a novel called Ye Cannot Quench, written by a madwoman named Gertrude Evans. You, Emily, are the heroine of the novel. Porter Walker is one of the characters in this novel, and my consciousness has been transposed into his body.”

“Wow, you really are crazy, Porter.”

“That may well be, Emily.”

“But I love you anyway.”

Emily had removed the jacket of her grey summer suit, and her white blouse was limp with perspiration, her skin was glistening, her hair looked as if it had been rained on, and tendrils of it stuck to her cheeks and throat. I could see her brassiere clearly under the fabric of the blouse, and, perforce, what the brassiere just barely held in check. She exuded a not unpleasant odor of perfume, gin, and lust, and to my deep shame and disappointment with myself and the universe I felt a stirring down below. She was standing there staring at me. I was just standing there. I glanced down at Sid, and he was staring at Emily’s breasts.

“I wonder, Miss Emily,” he said, “if you would care to join us for a drink? Ernest and I were going to order boiler rooms.”

“What the hell is a boiler room, Fu Manchu?”

“He means boilermaker,” I said, before things could get out of hand.

“Boilermaker,” said Sid. “It is a small glass of whiskey, accompanied by a glass of –”

“I know what a boilermaker is,” she said. “I didn’t just get off the Greyhound from West Virginia.”

“Ah, West Virginia,” said Sid. “Way down south in the land of sorghum? No, that can’t be right. Way down south in the land of – tobacco?”

“Cotton, Sid,” I said.

“Yes! Cotton! Way down south in the land of cotton, old folks there be misbegotten, look away, look –”

“Where’d you find this guy?” Emily said to me.

“Ah! Now that is an interesting story, milady,” said Sid. “Perhaps we could find a table, and –”

“Tell you what, Porter,” said Emily, “let me go shake off Julian and get my purse and jacket, and you and me’ll blow this joint and head up to your pad. To tell the truth I’d like to use your shower. And after that, well, you’re a poet, use your imagination.”

“I should love to see your pad, Ernest,” said Sid. “Do you have anything to drink there?”

“Hey, listen, Number One Son,” said Emily. “What kind of girl do you think I am?”

The barroom floor had filled up with dancers again. “Beat Me Daddy” had finished and now another uptempo number was playing, one I was not familiar with, but it sounded like “Baby Let Me Bang Your Box”.

(Continued here, and so on, and on...)

Published on July 07, 2017 22:39

June 30, 2017

The Memoirs of Arnold Schnabel: “the zen way”

Let’s return to a certain rainy summer night in New York City and rejoin our hero Arnold Schnabel and his new friend “Sid” (aka Siddhārtha Gautama, aka the Buddha), here in the entrance area of Bob’s Bowery Bar...

(Please go here to read last week’s chapter; those who would like to return to the very beginning of this Gold View Award™-winning 58-volume memoir may click here to purchase Railroad Train to Heaven: Volume One of the Memoirs of Arnold Schnabel, either as a Kindle™ e-book or as a deluxe large-format softcover “book” printed on FSC certified, lead-free, acid-free, buffered paper made from wood-based pulp.)

“What consummate joy to sit on the beach of old Cape May, shielded from the sun’s potentially carcinogenic rays by the shade of an enormous umbrella, turning the pages (or scrolling their electronic equivalents) of Arnold Schnabel’s magnificent chef-d'œuvre!” – Harold Bloom, in The Family Circle Literary Supplement.

It felt as if we had been standing out here in this entrance area for hours, it felt as if I had spent half my life engaged in frustrating conversations in this entrance area, but now at last we went through the open doorway into that packed, hot, cacophonous barroom.(Continued here...)

The drunken, shouting and laughing people were still dancing, or, if not exactly dancing, then thrashing about to the music of the combo stationed off to the far right, I could just see the smoke-shrouded heads of the musicians above the crowd, including one who looked like my old acquaintance Gabriel – at least he had the same kind of porkpie hat that Gabriel wore – and a Negro lady singing into a microphone:Give me your thunder stick, babySid and I were just inside the doorway, barely over the threshold, but already that churning thrashing hot mass of drunken humanity throbbed inches away from us, threatening to push us bodily back outside. Sid yanked on my arm and shouted up into my ear:

‘cause I wants to feel that lightning bolt.

Shove it into my socket, daddy

and give me a great big jolt…

“Do you know what I could really go for?”

“No,” I said, or rather shouted, we both had to shout to be heard.

“I mean,” yelled Sid, “I really shouldn’t, but you know what I could really go for?”

“I have no idea.”

“I’ll tell you what.”

“Great,” I said.

“A boiler room.”

“A what?”

“Boiler room?”

“I don’t know what you’re saying, Sid.”

“Boiling pot?”

“What?”

“Perhaps I have the name wrong. It’s a small glass filled with whiskey of some sort, accompanied by a glass of beer, preferably draft beer.”

“You mean a boilermaker.”

“Oh. Boilermaker. Why is it called a boilermaker?”

“I have no idea. Come on, we’ll get you a boilermaker.”

“It’s terribly crowded here, isn’t it?’

“You noticed that.”

“How could I help but – oh, ha ha – I suspect that that barbed little riposte was an instance of the much-vaunted American sense of humor, was it not?”

“Yes, Sid.”

“Where are your friends?”

“They’re in a booth off to the right there.”

“I see no booth.”

“That’s because it’s so crowded, but, believe me, it’s there. Or at least it was there the last time I was here.”

“You’re sure?”

“Yes,” I said. “In fact I can see it from here. I see my friend Ben’s head, or his boat captain’s cap, anyway.”

“You’re lucky you’re tall. It’s not easy being short.”

“Being short might actually be an advantage for you in here.”

“In what sense, may I ask?”

“If you get knocked over by one of these drunks you won’t have so far to fall.”

“Ha ha. That was another one of your little American jeux d’esprit, was it not.”

“A jeux de what?”

“Jeu d’esprit. It’s French for like a clever verbal sally in the tradition of the Oscars Wilde or Levant or your own lasso-twirling sage of the sagebrush, Mr. William Rogers.”

“Okay,” I said, moving along, “here’s what we should do, Sid. Just let me go first, trying to shove and fight my way through this mob –”

“Did you say fight?”

“I did, but I only meant it in a broad sense.”

“I am afraid I cannot condone fighting in any sense.”

“Okay, let’s just say some pushing and shoving then.”

“'Pushing and shoving', oh dear.”

“It can’t be helped, Sid. To be honest I may have to use an elbow also.”

“An elbow? You mean actually striking someone with your elbow?”

“Only if I have to. I may just use it as a defensive measure, to prevent someone from thrashing against me.”

“Must we really resort to violence?”

“Do you know any other way to get through this mob?”

“In fact I do, my dear chap.”

He said nothing else, and I knew I had to do my part to get him to say whatever it was he had to say, as much as I hated to do it, as much as I didn’t really care what he had to say.

“What way, Sid.”

“You don’t know?”

“Oh, for Christ’s sake –”

“Hey, be cool, in your patois, daddy-o! I’ll tell you.”

“Good. Shoot.”

“Does that mean you want me to go ahead and say it? Shoot?”

“Yes. Please say it, Sid.”

“The zen way,” he said.

“The zen way.”

“You heard me right.”

“And what is the zen way?”

“An enlightened chap like you. I think you know the answer to that.”

“If I had known the answer I wouldn’t be asking you, Sid.”

“Now that was spoken like a true guru!”

“Come on,” I said. “I’ll go first, and you just sort of stay in my wake. Maybe you should reach under the tail of my jacket and hang onto my belt. Just be careful, because if I get knocked backwards I might knock you over and you could get hurt, especially if I land on top of you.”

“Life is pain.”

“Yeah, Okay. But, look, Sid, keep your eyes open, I recommend continually glancing to the right and left, just in case there’s an attack from the side.”

“A flanking movement.”

“You might also get hit from the rear, so keep your shoulders slightly hunched, and your head down, like a boxer.”

“Like the great Marciano!”

“If you do get knocked down try to get up as best you can and as fast as you can. The last thing you want is people kicking you and trampling on you.”

“So you don’t recommend curling up in a protective fetal position?”

“No. If you do you might well never get up again.”

“What if I am not able to get up?”

“I’ll try to help you.”

“What if you are knocked down as well?”

“Then it’s every man for himself. Try to crawl toward the door and safety.”

“What if I cannot tell where the door is?”

“Just keep crawling then. Eventually you might reach safety. This is where your short stature might come in handy. You present a smaller target than a big man, and also you can try to crawl between people’s legs, like a cat or some other small animal.”

“Fair play to me, old bean. But what about you, if you are knocked down?”

“It won’t be so easy for me, because I’m bigger and there’s more of me to kick and trample, but I’ll just have to do the best I can and hope for the best.”

“I’m not afraid.”

“Swell.”

“You seem afraid.”

“I am afraid.”

“There is nothing to fear because all this is an illusion.”

“That’s good to know, Sid, but, look, let go of my arm.”

“Must I?”

“Yes, I’ll need both arms to shove people out of the way, maybe give them an elbow if I have to.”

“That is totally not a zen approach.”

“I don’t care, as long as it works. And listen, you have an umbrella, don’t be afraid to use it. Keep it held high and pointed up, so you can bring it down hard and quick if need be.”

“You mean strike someone with it?”

“I doesn’t have to be super hard. Just enough to try to get them to back off.”

“Might I make a suggestion?”

“Sure.”

“Can we at least try it the zen way?”

“The zen way.”

“The way of zen, yes.”

“Sure,” I said. “Give it a try. And when it doesn’t work we’ll just plunge into the mob and shove and push our way through.”

“O, as you Americans say, kay.”

“What?”

“Okay.”

“Oh.”

“That is the term, is it not? Okay?”

“Yes, but, look, Sid, it’s okay if you just say okay. You don’t have to keep saying ‘as you Americans say’.”

“But it is as you Americans say.”

“Okay, never mind. Go ahead and do your zen thing.”

“My pleasure, old boy.”

He took his arm from mine, gazing into the mob, or seeming to. He looked as if he were taking the lay of the land. But instead of plunging into the mob right away, he hooked his umbrella over his left forearm, took out his cigarette case, put a cigarette in his mouth, put the case away, took out his Tiger brand matches, lighted up his cigarette. He waved the match out, tossed it to the floor, dropped the matchbox back into his pocket. He slowly exhaled smoke and then looked up at me.

“Are you ready, Ernest?”

“I’ve been ready, Sid.”

“That’s the spirit, old chap. Readiness. Readiness for anything the universe has to offer.”

He looked out into that throbbing crowd again.

I waited, but he just stood there, smoking his cigarette. I suppose I only waited half a minute, but it seemed longer.

“Sid,” I said, shouted, “what are we waiting for?”

“Nothing,” he said, shouted back.

“Well, why are we still standing here?”

“Because we’re utilizing, my dear chap, the zen approach.”

“This is the zen approach.”

“How quick you are.”

“The zen approach is that we’re just standing here.”

“Precisely.”

“But how is this getting us where we want to go?”

“How do you know this is not where you want to go?”

“I’m pretty sure where I want to go is not just standing here near the doorway of this bar.”

“Pretty sure.”

“Okay, absolutely sure.”

“Absolutely?”

“Yes, I’m absolutely sure I don’t want to just stand here all night.”

“No one said we’re going to stand here all night.”

“Well, how long are we going to stand here?”

“For as long as it takes.”

“That could be hours.”

“What is time?”

“I have no idea, but I don’t want to just stand here for hours.”

“Want. 'Want'. You know I had hoped that you were developed enough to get beyond the concept of want.”

“You were wrong, then, Sid.”

“My dear fellow, perhaps you should smoke some more reefer?”

“I don’t want to smoke some more reefer. I want to get through this crowd to my friends.”

“I had hoped that I was your friend.”

“Maybe you are, Sid. But I still want to see my other friends sometime tonight.”

“Oh, I’m sure you’ll see them some time tonight. The bar must close, eventually, must it not?”

“Yes, but that could be hours from now –”

“Again, ‘hours’. The web of time. You will never achieve even a modicum of peace until you free yourself from time’s web.”

“Thanks for the tip, Sid.”

“I give it to you freely.”

I stood there, feeling the noise and the heat, breathing in the smoke and the thick effluvia of liquor and beer, of sweat and cheap perfume, not that I would know cheap from expensive perfume, but I assumed it was the cheap kind, and once again I became aware of various injuries and pains on and in my current corporeal host, notably from my knees and head and face and elbows, but elsewhere also.

The drunken people thrashed and shouted and laughed and screamed, occasionally an arm or a leg would glance against me or even outright hit me, but what was one more blow, or a dozen blows, at this point?

Sid just stood there by my side, to my right, smoking his cigarette. He had moved the crook of his umbrella from his forearm to his left hand, and he leaned lightly on the umbrella, his face tilted slightly to one side under the rim of his straw boater, a little smile on his face.

“Okay, Sid,” I said, at last, “I can’t take this anymore. You can stand here if you want to, but I’m diving in.”

“As you wish, my friend, although I do wish that you would rise above the very concept of wishing.”

“But you just wished something yourself.”

“I never said I was perfect, old boy.”

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll see you later, maybe.”

“I would wish you luck, but you know how I feel about wishing.”

“Yes,” I said.

I took a deep breath of that foul air, preparatory to plunging into that mass of drunken humanity, when suddenly the music stopped.

“Thank you, ladies and gentlemen,” said the Negro lady’s amplified voice. “We’re gonna take a brief break, but we’ll be back as soon as we have wet our collective whistles. So drink up, people, because the more you drink the better we sound!”

Just like that the crowd of people stopped dancing and thrashing. There was a smattering of applause and a few hoots, and the mob dissolved as the drunks made their way back to the bar and the tables, to the rest rooms, somewhere.

“Do you see, Ernest?” said Sid. “The zen method worked!”

I could not deny it.

Published on June 30, 2017 22:59

June 23, 2017

The Memoirs of Arnold Schnabel: “My friend Sid”

Let’s rejoin our hero Arnold Schnabel and his new friend “Sid” (aka Siddhārtha Gautama, aka the Buddha) on this rainy summer night, here in the entrance area of Bob’s Bowery Bar...

(Kindly click here to read last week’s thrilling adventure; if you would like to return to the very beginning of this Gold View Award™-winning 63-volume epic you may click here to order Railroad Train to Heaven: Volume One of the Memoirs of Arnold Schnabel, available either as a Kindle™ e-book or as an old-fashioned softcover “book” printed on FSC certified, lead-free, acid-free, buffered paper made from wood-based pulp.)

“Ah, summer! And what better way to pass the day than sitting on the shady porch of our quaint Victorian ‘cottage’ in Cape May and reading a few hundred pages or so of Arnold Schnabel’s enormous (and enormously rewarding) chef-d'œuvre!” – Harold Bloom, in the Cape May Pennysaver Literary Supplement.

I didn’t know what to say to that remark, and so I said nothing, which of course is not always the case with me, to say nothing when I have nothing to say, in fact I would estimate that 99% of what I’ve said in my life has been said despite having nothing to say, and perhaps this very sentence is an example.

“A huge admirer,” repeated Sid.

“Uh,” said I, it was the best I could manage at the time.

“And I shall be ever so delighted to meet him. Do you think he’d like to meet me?”

“Oh, sure,” I said.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, sure, he’d like to meet you.”

“Yes, but the way you said it.”

“I didn’t mean anything by it,” I said, realizing that just because he realized he had a tendency to come on too strong didn’t of course mean he was likely to do anything about it.

“It sounded as if you were saying, ‘Oh, sure, he would like to meet you.’”

“That’s what I said.”

“Yes, but in a way that, oh, sure, he would like to meet anybody.”

“Well, I think he is that way,” I said. “Much more than me, that’s for sure.”

“Yes, but we’re not talking about you. We’re talking about Jesus Christ. The son of what I believe you Americans call ‘the chap upstairs’.”

“I realize that, uh, Sid,” I had almost addressed him as Mr. Buddha again, but caught myself in time.

“If you don’t think he would like to meet me I wish you would just say so.”

“Sid, I just told you I think he would like to meet you.”

“You really think so?”

“Yes, I really think so,” I said.

“Well, okay, then.”

“Let’s go in,” I said.

“Wait.” He put his hand on my arm. He had put his cigarette in his lips so that he could do this unencumbered, since he still had his umbrella hanging from his other arm. “Correct me if I’m wrong.”

“Okay,” I said.

“What you’re saying is he wouldn’t mind meeting me because he wouldn’t mind meeting anyone.”

“Yes,” I said.

“But not, you know, because.”

I knew he wanted me to say “Because of what?” but I just couldn’t bring myself to say that, my little revenge I suppose for his being so annoying.

“Because of the obvious,” he said.

Again I gave him no relief. I’m not proud of the way I was behaving, but I’m trying to be truthful in this chronicle.

“The obvious being,” he finally continued, realizing what a mean human being I was being, “because I am no other than Siddhārtha Gautama, perhaps better known as the Buddha.”

I sighed, this was I believe my ten thousandth sigh of this longest day in history, at least my own personal history.

“I don’t really understand what you’re getting at, Sid.”

“I mean,” he said, “one would think he would be delighted to meet me, he and I being in the same shall we say general line of work you see –”

“Oh, I get it now. Yeah, I’m sure he’ll be delighted to meet you, Sid.”

“You’re really sure?”

“Pretty sure.”

“Pretty sure.”

“Yeah –”

“’Pretty sure’. Okay. Wow.”

“I mean I can’t say for absolutely sure, Sid, but –"

“But you’re pretty sure.”

“Yeah.”

He still had his hand on my arm, gripping it uncomfortably tightly, and it was all I could do not to shake him off, or try to, try to shake him off and toss him out into the downpour and make my escape into the bar.

“I think I get it,” he said.

“Good,” I said.

“Oh, I get it.”

“Uh –”

“You’re fairly sure –”

Oh Christ, I thought, very loudly, in my brain.

“Somewhat sure.”

“Oh, Christ,” I said, aloud this time.

“Pretty sure,” he said, “provided that I don’t, in your parlance, ‘come on too strong’.”

“Yes,” I said, flatly, because, now that he mentioned it, that was probably what I had meant, more or less, although maybe not more, more likely less.

“Well, my dear sir, I have already assured you I will do my best not to, as you say, come on too – oh, dear. Oh my goodness. I just realized. I have been coming on too strong again, haven’t I?”

I didn’t say anything, again. I didn’t have to say anything.

“Okay. Look, Arnold – I can call you that, right?”

“Sure.”

“Arnold, look, if I get out of hand again, I want you to slap me. Okay? And hard. I mean, really give me a strawmaker as you Yankees say?”

“I’m not going to slap you, Sid.”

“Okay, fine, but give me a nudge. Or, like, step on my foot, clear your throat – or, maybe you could fake a coughing fit?”

“Okay,” I said.

“You promise?”

“I promise. Can we go in now.”

“Certainly.”

He took his hand off my arm, took the cigarette from his lips and tapped off the ash, which I noticed tumbled down to land on the scuffed uppers of both of my work shoes. I made a move to turn and head through the doorway into the bar, but he quickly stuck the cigarette back in his mouth and grabbed my arm again.

“But wait,” he said.

“Now what, Sid?”

“What’s he like?” he said, in almost a whisper, as if anyone was listening.

“You mean Jesus,” I said, loud and clear.

“Yes! Who else are we talking about?”

“He’s –” I paused, possessed by one of those occasional urges to tell the truth that sometimes descend upon me, “probably not quite what you would expect.”

“But he’s still perfect, right?”

“I can only assume so,” I said.

“Assume. You are so modest. Come, come, my good fellow – he’s the son of God! Of course he’s perfect. How could he not be perfect?”

“He likes to drink,” I said.

“Nothing wrong with a drink now and then.”

“He likes to drink a lot.”

“Oh. You mean he likes it a lot, or he drinks a lot.”

“Both,” I said. “To tell the truth he was pretty drunk when I last saw him.”

“Really. Well, maybe, just maybe when the son of God gets drunk it’s all part of his perfection. I mean, can we judge him the way we would judge an ordinary human, or one of the lesser gods?”

“The what?”

“Lesser gods.”

“Lesser gods?”

“Or any other gods.”

“Other gods?”

He stared up at me through the thick lenses of his glasses.

“Am I to believe you don’t know about the other gods?”

“As a Catholic I was brought up to believe there was only one God.”

“Oh, right. And yet your so-called ‘one God’ if I am not mistaken is really three gods, isn’t he?”

“Well, not exactly –”

He took his hand off my arm, made a fist, and then stick out his index finger.

“Father,” he said.

Then he stuck out his forefinger, which had a gold ring with a tiny little Buddha made out of jewels on it.

“Son.”

Next he popped out his ring finger, which had another gold ring on it, this one with a little crosslegged lady made out of jewels on it.

“Holy ghost,” he said.

He took his cigarette out of his mouth, and breathed smoke up into my face.

“Three gods,” he said. “Not one. Correct me if my maths is wrong.”

“Okay, Sid,” I said, I have no idea why, “but, you see, according to the doctrine of the Trinity, they’re really just, uh, you know –”

“What about the Sun God?”

“Who?”

“The Sun God. God of the Sun. The big yellow thing in the sky during the daytime? Sun God.”

“There’s a Sun God?”

“What about the God of Thunder?”

“Okay,” I said.

“God of the forest, or I should say gods of the forest –”

“All right –”

“Do I have to go on, enumerating hundreds more gods?”

“No,” I said.

“Bacchus, God of wine. Chandra, the reefer god.”

“Okay.”

“Not to mention gods that even I don’t know about.”

“Uh-huh.”

“I forget that, enlightened as you are, you are still a human being, aren’t you?”

“Presumably,” I said.

“’Presumably.’ Ha ha. You kill me. ‘Presumably.’”

He took a drag of his cigarette, tapped the ash, which tumbled down to my shoes again.

“Unless,” he said. “Unless. Unless.”

“Okay, unless what,” I said, it was either that or scream.

“Unless you yourself are a god.”

“I don’t think so,” I said.

“You don’t think so, but maybe that’s just because you don’t know.”

“Hey, maybe we should go in now.”

I made a move to turn, but he quickly put his cigarette back in his mouth and grabbed hold of my arm again

“Y’know,” he said, “a lot of people think I’m a god.”

“Really? Y’know, we should go in, because come to think of it, I’m really hungry, I haven’t eaten since –"

“I once fasted for two weeks. Try to beat that.”

“I don’t think so, but, look, I am pretty hungry, and I’d like to order some food, and if we go in too late the kitchen might be closed.”

“Just because I started a religion with millions of followers, a lot of westerners think that makes me a god.”

“I think they have a late-night menu, but I’m not sure just how late they serve.”

“I’m the Buddha, but I’m not a god.”

“Okay, well –”

“Like Mohammed, same deal with him. Millions of adherents to the religion he started, but he’s not a god either. Allah is the God.”

“Okay, I wasn’t quite clear on that. So –”

“Your friend Jesus, though,” he said. “Wow, not only a God, but the son of God. That’s what you Americans call a double threat. Like Babe Ruth was not only a great batsman but an excellent bowler as well.”

“Can we go in now?”

“Sure,” he said. “I’m dying to go in.”

He took his hand off my arm, but just as quickly grabbed it again, and his grip was strong for such a little fellow, my forearm was actually getting sore from him gripping it so hard and for so long.

“Now what?” I said.

“How do I address him? Dear lord? Master? Divinity?”

“Just call him Josh.”

“Josh?”

“Yes,” I said. “He likes to be called Josh now, because he wants to be a human being instead of God.”

“Really? But he’s still the son of God, right?”

“I don’t think he wants to be the son of God anymore either.”

“Oh, I get it. You’re – I think the term is – fucking with me.”

“No."

“An instance of the much-vaunted American sense of humor perchance?”

“No.”

“You’re telling me he doesn’t want to be God or the son of God anymore. At all.”

“Right. He just wants to be a regular human being.”

“In your parlance again: wow.”

“I know. It’s kind of strange.”

“Strange is not the word. It’s – in your American argot – kind of fucked up.”

“Well, maybe so, but –”

“So I should address him as Joshua?”

“Just Josh.”

“’Josh’.”

“Yes.”

“Okay. All right. And, look, when you introduce us, maybe you should just introduce me as ‘Sid’, okay?”

“Sure.”

“Like, ‘Josh, I should like to introduce you to my friend Sid.’”

“Okay.”

“I don’t want to come on too strong.”

“Good idea,” I said. “Could you let go of my arm now?”

“Oh, yes, of course,” he said, and he removed his vice-like grip from my forearm.

With my other hand I massaged the inflamed area of my arm.

“Okay, let’s go in,” I said.

“Certainly,” he said.

He took a drag from his cigarette, which was smoked down to its last half-inch. He blew the smoke up into my face. You didn’t really have to smoke your own cigarettes with him standing there. He flicked the butt out into the unabated downpour where its tiny fire was immediately extinguished and the less tiny tube of tobacco and paper was flushed away into the gutter, to the sewer, to the Atlantic Ocean.

“I must say I’m getting thirsty,” he said, with a smile, and slipping his arm in mine. “This dreadfully humid heat. Are you thirsty?”

“Yes,” I said, although I wasn’t thirsty for water.

(Continued here, provided this world is still here...)

Published on June 23, 2017 23:59

June 16, 2017

The Memoirs of Arnold Schnabel: “Navy Cut”

We last saw our hero Arnold Schnabel in the entranceway of Bob’s Bowery Bar, accompanied by his new acquaintance the Buddha, who has assumed the form of a “small Oriental-looking man” in a white suit and a straw boater hat...

(Please go here to read last week’s exciting episode; if you would like to begin at the very beginning of this Gold View Award™-winning 57-volume epic you may click here to order Railroad Train to Heaven: Volume One of the Memoirs of Arnold Schnabel, available both as a Kindle™ e-book or as palpable “book” printed on FSC certified, lead-free, acid-free, buffered paper made from wood-based pulp.)

“Now that the first volume of Arnold Schnabel’s chef-d'œuvre is at last available for purchase, is there really any question as to what book should be number one on any book lover's list of ‘summer beach reads’?” – Harold Bloom, in the Reader’s Digest ‘Summer Fun’ Supplement.

“Very well done, my friend – very well done indeed!”

The little man smiled broadly, revealing perfectly white and gleaming teeth, and he looked past me into the entrance of the bar.

“My, this does look a jolly place! I can’t tell you how long it’s been since I’ve been in a tavern or an alehouse – are we going in?”

“Well, I was intending to go in, yes,” I said.

“And get a little – as you Americans say – ‘load on’?”

“Well,” I said, “I’m afraid that’s what usually happens in these places, but actually I’m hoping to find some friends of mine.”

“You have friends?”

“Believe it or not, yes.”

“Ha ha, no offense, old bean.”

“That’s okay,” I said. “In fact, there was a time when I had no friends.”

“You do strike me as the loner type. The brooding poet in his garret, that sort of thing. Not that there’s anything wrong with being a brooding poet in a garret.”

Little did he know that I actually did sleep in a small attic room, which I think is the same thing as a garret.

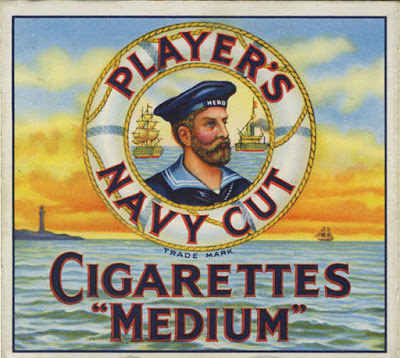

He had hooked the bamboo crook of his umbrella over his left forearm, and now he reached into the right side pocket of his suit coat, brought out a golden jewel-encrusted cigarette case, held it out to me and clicked it open.

“Player’s Navy Cut?”

I raised my hand to take one, but stopped myself.

“Go on,” he said. “Take one, I’ve got plenty as you see.”

“Well, I know this will sound hard to believe,” I said, “but I’ve given up smoking.”

“You have?” he said. “My goodness, I hope you won’t take offense if I should humbly ask why, in the name of all the gods, if I may be so bold as to pretend to speak for them?”

“Why did I quit smoking?”

“In the proverbial nutshell, yes, why would you possibly want to quit so pleasurable an activity as smoking?”

“Well, okay, the immediate cause for my, uh, quitting was that yesterday morning – although it feels like nine years ago – I woke up coughing my lungs out, just as I usually did, which was the opposite of pleasurable, then or ever, and I was tired of it. The other reason was that I didn’t want to die of cancer. Or emphysema. Or both.”

“So you’re that invested in your corporeal existence?”

“Yes,” I said. “Also, I dislike pain.”

“Okay. I get that. Far be it from me to judge. But you don’t mind if I smoke?”

“Not at all,” I said.

“Or.” He cocked his head. “Or, we could fire up a marijuana cigarette. A ‘reefer’ in your parlance.”

“Um, uh –”

“Come, come, dear sir, I know you appreciate the sacred weed. You certainly held your own with Wiggly Jones, ‘the little hippie lad’, and that’s saying something!”

“Well, yeah, but –”

“The reefer-smoking equivalent of ‘going the distance’ with the great Jack Dempsey!”

“Heh heh –”

“Hold on.”

He snapped shut the cigarette case, dropped it back into the side pocket of his suit coat, then reached into its inside pocket and brought out a Player’s Navy Cut cigarette tin.

“Call me pretentious, but I like to keep my Navy Cuts in my nice Cartier case, but I find that these Player’s tins are excellent for carrying tubes of the sacred herb.”

He clicked the tin open, and there must have been at least a dozen fat and obviously hand-rolled cigarettes in it.

“I know what you’re thinking,” he said, “why not just keep them in my Cartier with the regular cigarettes? And I’ll tell you why, because if I see a flatfoot or what looks like a plainclothes bull about to brace me and shake me down I can quick just toss the Player’s tin of sacred smokeables down the nearest sewer, which I would hate to do with my nice Cartier case, I don’t even want to tell you how much they would charge over the counter for it, not that I had to pay retail, but still.”

It occurred to me that he really didn’t need to smoke any reefer, but I said nothing.

“So what do you say we fire one of these little ecstasy-sticks up?” he said.

“Listen,” I said, “Mr. Buddha –”

“Hey. Ernest.”

“Arnold,” I said, I don’t know why I bothered.

“Arnold,” he said. “What did I tell you about this ‘Mr. Buddha’ business? Call me Sid. I mean if you prefer to be more formal you can call me Siddhārtha – Siddhārtha Gautama is my full name, not that I expect you to remember that – but, look, I like to think we can be friends, so, please, call me Sid.”

“Okay, Sid –”

“Yes, Ernest?”

“Uh –”

“Just jesting,” he said. “Arnold. I remember your last name, too. Arnold Sch-, Scha-, Schu–”

“Schnabel,” I said.

“Schnabel?” he said.

“Yes,” I said, probably in a way that my favorite authors would describe as “wearily”.

“’Arnold Schnabel.’ Good, I’ll remember it now.”

He took out one of the handrolled cigarettes and put it in his lips. He snapped the tin shut, slipped it back into his inside pocket, then reached into his side pocket again and brought out a box of Tiger brand matches. He slid it open, took out a match, struck it on the side of the box, and lighted himself up. He tossed the match out into the rain, it sizzled out and was dashed to the sidewalk to be washed away into the gutter and then into a sewer and finally out to the ocean where it would drift forlornly till the end of time. He dropped the matches back into his pocket and then, holding in the smoke, his eyes bulging behind his round glasses, the Buddha proffered the reefer to me.

“Listen, uh, Mister –” his thin eyebrows popped up, so I immediately corrected myself, “I mean, Sid, maybe it’s not such a great idea to smoke that in public –”

He exhaled marijuana smoke up into my face.

“Arnold,” he said, with a small smile, “just take a look around at where you are.”

“I don’t have to look around, I know where we are.”

“Do you see any policemen around here? Do you think they’re out walking their beat in this torrential downpour? And, yes, I know, maybe a patrol car might cruise by, but even if it did, what are they going to see? Just two chaps taking the fresh air outside of a taproom, sharing a convivial cigarette. And as for the good people inside the taproom – just cast an eye.”

Involuntarily I turned and looked through the doorway at that crowd of drunken, dancing, shouting people, with the music blaring over them through the thick swirling smoke, a lady’s voice singing,Roll another muggles, daddy,“You see what I mean?” said the Buddha, or Sid, as I suppose I should get used to calling him, “You think anyone in there cares? Now come on, you’re wasting the precious weed.”

roll it up thick and tight.

Now fire that muggles up, big daddy,

‘cause we gonna get real high tonight…

I suppose I’d like to be able to say I took the reefer just to shut him up, and this was true as far as it went, but I also took it because I wanted to, indeed I even felt I needed to. At any rate I took the reefer.

“Thanks,” I said.

“It’s me who should be thanking you,” said Sid.

“For what?” I said, taking a series of quick inhalations like the expert I was apparently becoming.

“For what?” said Sid. “Why, for enabling me to assume the corporeal form of a human being again!”

“I did that?” I croaked, in a constricted voice, as I was still in the process of “toking”.

“You certainly did, old chap. I told you you were enlightened, did I not?”

“Yes,” I said, finally letting out a great cloud of smoke from my lungs. “But I didn’t know –”

“Yes?”

“Didn’t know I had these sorts of –”

“Powers?”

“Yeah.”

“Supernatural powers.”

“Right.”

I was staring at the reefer. It seemed unusually strong in its effect, and I was compos mentis enough to formulate the thought that I probably shouldn’t smoke any more of it.

“One powerfully enlightened being,” said Sid, “that’s what you are, my friend.”

“Uh.”

“What?”

“I don’t feel very enlightened,” I said, “I feel more like the opposite –”

Sid took the reefer from my fingers.

“There you go,” he said. “Not only enlightened, but humble, too!”

“Well, if you were me you would be humble, too.”

“Spoken like a true guru of the old school!”

He drew on the reefer, he had his own method, a few very deep, very slow draws. He took his time, and then exhaled another cloud of smoke in the direction of my face.

“You know something, Arnold, If I didn’t want to get the knees of my trousers wet and soiled I would verily kneel before you in obeisance.”

“No need for that,” I said.

“So modest,” he said. “I wish all enlightened people were so humble and modest. But you know how it is. Chaps get a little enlightened, assume guru-hood, and then next thing you know they get a swollen head. Don’t let that happen to you, Arnold.”

He pointed the lit end of the reefer at me.

“I doubt it will,” I said.

“Unless,” he said, “– and I’m not saying this would happen, but still it’s something any guru needs to watch out for – unless you start becoming proud of your very modesty.”

“Oh. Uh –”

“Or –” he took another smaller slow draw on the reefer, paused and then took another; at last he exhaled and resumed his sentence – “and I’ve seen this happen, more times than I would like to say – unless you start getting all full of yourself once you have all sorts of students and followers hanging on your every word of wisdom –”

“I don’t see that happening,” I said.

“Getting full of yourself?”

“Having students and followers,” I said. “And since I’ll never have students and followers I won’t be able to get full of myself about it.”

“Well, all I can say, Arnold, is, just, as you Americans say, like, wow.”

“Heh heh,” I said.

“You laugh.”

“Almost mirthlessly, though,” I said.

“But why are you laughing, albeit almost mirthlessly.”

“Never mind.”

“You think I’m joking.”

“Well, no –”

“Someday,” he said, “just you wait, there they’ll be, your students, disciples, sitting all around you, hanging on your every word, your every slight change of facial expression, or the tiniest gesture with a finger –”

He held up his left hand and made a microscopically small gesture with his little finger, which I noticed had a fancy gold ring on it.

“See? Like that,” he said. “Just the tiniest wiggle.”

He tinily wiggled the finger again.

“Ha ha,” I said.

“Seriously. I’m not joking,” he said.

“I’m sorry,” I said, “and besides, I think that reefer is really strong.”

“Of course it is. Grown on the southern slopes of a certain verdant valley of my native Nepal. A little slice of heaven we like to call Shangri-La. Have some more.”

“No thanks,” I said. “I think I’d better not.”

“Save it for later.”

He pinched the light out of the end of the reefer with his finger and thumb.

“Here, stick it in your pocket.”

He held up the reefer. I took it and stuck it in my shirt pocket. I had sunk pretty low, I realize that.

“Excellent,” said Sid, “now let’s get in there and get that aforementioned load on, shall we?”

“Wait, hold on, Sid,” I said. “I have to tell you something.”

“Great. Unmuzzle your wisdom, as your bawdy bard once wrote.”

“I’m not going in here just to get a load on.”

“No? Then whatever for?”

“I just want to say goodbye to my friends I told you about. And then I want to try to return to the real world.”

“All right,” he said, after just a moment’s pause.

He took his cigarette case out again, clicked it open, offered its contents to me. I shook my head, he shrugged, took out a cigarette and put it in his lips.

“Sure,” he said. “Whatever.”

He clicked the case shut, dropped it back in his suit coat pocket, brought out the box of matches again.

“I’d like to meet these friends of yours,” he said.

He took out a match, struck it, lighted up his cigarette, exhaled a great slow cloud of smoke up into my face. Again he flicked the match out into the downpour where it was extinguished and washed away to follow its fellow on an endless voyage into oblivion.

“I mean,” said Sid, he took the cigarette from his lips, holding it between his thumb and forefinger, looking at it, and then at me, “if you don’t mind introducing me –”

“Sure, I don’t mind,” I said.

“Do you think I’ll like them?”

“Uh, yeah – one old guy is kind of crusty –”

“I love crusty old men!”

“Well, I guess you’ll like him, then.”

“But will your friends like me?”

“I, uh –”

“What? You don’t think they will?”

“I don’t know –”

“You don’t know?”

“I mean I’m not sure.”

“Wow, that’s harsh.”

“I’m just trying to be honest, Sid.”

“As you should be. But wow. Am I that unlikable?”

“No, not really –”

“But I am a little.”

“Uh –”

“A little unlikable.”

“Not unlikable so much,” I said, “but –” and I would never have said this normally, but, again, that reefer had been very strong – “you come on a little strong, Sid.”

“Wow.”

“I’m sorry.”

“No, it’s true,” he said. “Can I tell you something?”

“Sure.”

“Do you know why I was just a cigarette lighter before you helped me assume a human corporeal host again?”

“Uh, no.”

“Because of my tendency to come on too strong. That’s why.”

He took a drag on the cigarette, looked out at the rain, and then back at me.

“I fucked myself. And one fine day I woke up and found that I was a cheap mass-produced table lighter. Well, not super cheap, I was produced at the Ronson factory in Newark, at least I wasn’t some Soviet-made knock-off, but, still. Anyway, I will do my best not to come on too strong with your buddies. And I mean that.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I said. “They’re not perfect either. Except, well –”

“Except what?”

“Well, one of them might be perfect.”

“My goodness, a super guru. What’s his name?”

“Well, he’s Jesus Christ,” I said.

“The Jesus Christ.”

“Yes.”

“I am a huge admirer,” he said.

(Continued here, in this same time and space...)

Published on June 16, 2017 23:25