Dan Leo's Blog, page 33

April 27, 2019

"All Bob's Children"

Most career marines talk about opening up a bar when they retire from the Corps, but Bob knew that most of these guys wound up sitting in bars owned by somebody else for the rest of their lives until the cirrhosis retired them for good.

Bob was different. After twenty years in the Corps and serving everywhere from Veracruz to Belleau Wood and from Port au Prince to Shanghai, he retired at the age of thirty-eight and actually opened up a bar.

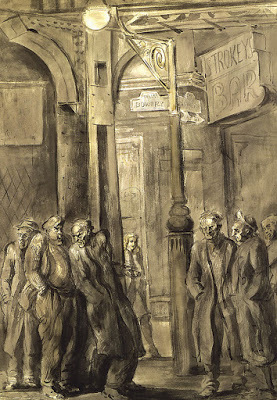

The year was 1930, the Depression had hit the real estate market hard, and so for a thousand bucks cash on the barrelhead Bob was able to pick up a speakeasy right off the corner of Bleecker and the Bowery, and the previous owner threw in the four-story building it sat in to boot. Bob got to work with hammer and nails and paint, and after two months, he opened the joint up for business, with his specialty being a strong dark bock beer he brewed himself in the basement.

At first the place didn’t have a name. It was just another speak with no sign out front, and people called it “the marine’s bar”, or “that new speak off Bleecker”, but after people got to know Bob they started calling it “Bob’s Bar”. When Prohibition was repealed and Bob finally opened up legally, there seemed no question but to call the place Bob’s Bowery Bar. For years there was still no sign, but then finally around 1950 Bob broke down and had a neon sign put in the front window:

BOB’S BOWERY BAR

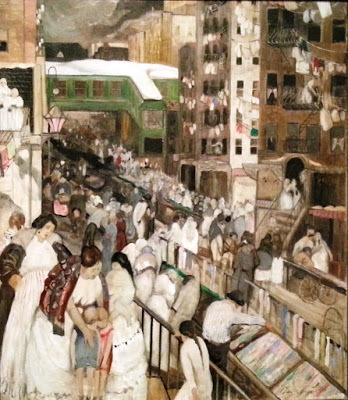

Bob’s was never a typical Bowery dive, because Bob was not a typical man. Sure, most of his clientèle were Bowery bums and layabouts, but you would also find poets and novelists, lots of hack pulp magazine writers, actors, musicians, academics, and people of professions unknown. Bob turned away no one who had the price of a glass of his famous basement-brewed bock. Negroes and Chinamen, Jews and Catholics, communists and right-wing zealots, Bob let anyone in, as long as they were eighteen years old and behaved themselves. Get out of line though, and Bob would rap his Marine Corps ring on the bar once. He never had to rap it more than once, because you either behaved or you were sitting on your ass on the sidewalk outside.

Bob’s physical strength was the stuff of legends, and nobody really knew how he stayed in such great shape, but all anyone did know was that he carried one of those fifty-gallon kegs of bock up from the basement on his shoulder and set it down behind the bar as gently as if it were a barrel made of thin air containing nothing but air. Maybe carrying those kegs up from the basement was how he stayed in shape, that and arm-wrestling, because Bob had a standing offer to buy a drink for any man who could beat him at arm-wrestling, right or left arm, it didn’t matter to Bob, and he had never lost once. Come to think of it, maybe another way Bob stayed in shape was throwing people out of the joint. It was nothing for Bob to knock out a two-hundred-and-fifty pound stevedore with one punch, then haul the bruiser up over one shoulder and carry him out and through the door where he would unceremoniously dump the poor lug on the sidewalk.

Bob was a bachelor, and a confirmed one.

“What would I do with a wife?” he asked. “What would a wife do with me?”

Nobody could answer those questions.

“But what about children?” said the Gerry “the Brain” Goldsmith one afternoon, even though the Brain had never had any children himself, and in fact was still a virgin at the age of forty-eight.

“What about children?” said Bob.

“Wouldn’t you like to have some?” said the Brain. “Some children to carry on the great Bob legacy?”

Bob stared at the Brain, and took out a Parodi. He lighted it up, and then and only then he spoke.

“Y’know, Brain, for a guy they call the Brain, you say some pretty asinine things sometimes.”

Everybody laughed, including the Brain, and Bob looked at them all.

The Brain, old mush-mouth Joe, Fat Angie the retired whore, George the Gimp, the old guy they called Wine, Tom the Bomb.

Over there at the four-top by the door were some of the poets: Scaramanga the leftist poet, Lucius the Harlem poet, Seamas the Irish poet, Hector the doomed young romantic poet.

At the round-top sat some of the show-biz regulars, killing the time before their evening shows: the actress Hyacinth Wilde, the actor Angus Strongbow, the playwright and director Artemis Boldwater, that up-and-coming canary Shirley de La Salle and the Hotel St Crispian’s bandleader Tony Winston…

Sitting by himself and quietly scribbling in a schoolboy copy book was goofy Pete Willingham, who had been surprisingly well-behaved after his last stay at Bellevue. Maybe that lady shrink Dr. Weinberg had done him some good after all, or maybe it was the fact that Pete had become a devout convert to Trotskyism as well as to Roman Catholicism. Who knew?

Janet the waitress chatted with some other regulars seated by the door with a pitcher of bock. The four rumdums at the table were happy just to look at her, and who wouldn’t be?

“Who needs children?” said Bob, as if to no one and everyone.

For some reason the crowd at the bar stopped laughing and talking, and they all looked at Bob.

Everyone here, all of them, these were all Bob’s children.

– All Bob’s Children, by Horace P. Sternwall, a Demotic Books “paperback original”, 1954; out of print.

Published on April 27, 2019 08:25

April 25, 2019

"The Ballad of Barton Browne"

Barton Browne prided himself on being a “health nut”, and so you can well imagine his disappointment when one evening his car ran off the road in a “frequent accident area” and smashed into a pine tree.

What had once been a well-kept figure of a young man was now a mass of broken and fractured bones, and it was six months before he left the hospital, and even then it was with a walking stick, and a severe limp.

Barton had taken out an excellent insurance plan, and he figured that if he invested his money wisely he would never have to work again, which was just as well, because his physical condition would never have allowed him to return to his job as a door-to-door vacuum-cleaner salesman. He had excelled at his work, winning “Salesman of the Year” bonuses five out of the past seven years, and his former employers appreciated his service sufficiently to grant him a modest pension for life, even though they were not obliged to do so.

Barton decided to use his pension money for living expenses, and his insurance money he invested in an array of blue-chip stocks. His Lower East Side apartment was on the first floor, and so he had no demanding reason to move into an elevator building.

He got to know his neighborhood, limping around with his malacca walking stick. Before the accident his plan was to live here only until he had saved up the money for one of those new homes in the suburbs. This imaginary home – one of the fashionable “ranch” styles – was always meant in Barton’s dreams to be shared with a wife; a wife, in baseball terms, “to be named later”. But who would ever marry a cripple, a broken man who could barely hobble around with his cane, who could not even lift a telephone book with one hand? No, Barton resigned himself to a long retirement of celibacy.

But he could look. And look he did, at the girls and women he saw in the street, on the bus and in the parks, and on the silver screen in the movies.

Barton had never been much of a drinker, and he still wasn’t, but he had taken to stopping into a tavern at Bleecker and the Bowery called Bob’s Bowery Bar.

The eponymous proprietor brewed his own bock beer in the basement of his establishment, and Barton was so taken by the novelty of this old-fashioned practice that he made the house bock his regular tipple.

He would sit at the bar nursing the dark, not-quite-cold, barely carbonated but rich and full-flavored beer, and out of the corner of his eye he would admire the waitress, Janet.

He was not alone in this admiration. All the bums in this bar (and to be honest, most of them really did seem to be bums), all of them worshipped Janet, an auburn-haired, strong-looking Irish girl who took care of her kid brother and sister, her parents having died some years before, of cancer (the mother) and alcoholism (the father).

Very gradually, over the course of dozens of slow afternoons, Barton became “friendly” with Janet, in that way that “regulars” in a bar or café become friendly with the staff.

When Barton came into to the bar, usually at around 4pm, he would say hello to Janet.

“Good afternoon, Janet. How are you today?”

“Not bad, Barton, how are you today?”

“Could be worse, Janet!”

“You said it, pal.”

And that was about as far as their friendship went, but it meant a lot to Barton, just saying hello to this beautiful and brave young woman.

He knew their friendship would never go any further, but what they had was good enough for him, and all in all he felt he had made the right decision that fateful evening when he was driving home after another long day of selling vacuum cleaners, when, on a moment’s impulse, he had yanked his steering wheel hard to the right and smashed his car into that pine tree.

– The Ballad of Barton Browne, and Other Tales of Modern Life, by Horace P. Sternwall; a Pyramid Books “paperback original”, 1954; out of print.

Published on April 25, 2019 07:44

April 24, 2019

"The Burnt-Out Detectives Group"

“My name is Joe, and I am a burnt-out detective.”

“Hi, Joe,” said a dozen gruff voices.

“Hello, Joe.”

“Welcome, Joe.”

“Testify, my brother Joe,” said Luke, the Negro detective.

“Greetings, Joe,” said Bradley, the stout intellectual detective who liked to quote Shakespeare.

I paused before continuing, staring out through that thick cloud of cigarette smoke at all these other detectives in this church basement in a poor neighborhood, a neighborhood from the mean streets and alleys of which I had myself crawled out of, so many years ago. Or had I ever really left?

“This is my first time here,” I said. “So I hope you will bear with me.”

“We’re with you, man.”

“We’ve all been where you are, Joe.”

“Take your time, Joe.”

“We feel you, brother.”

“I guess,” I said, “like all you guys, I have seen too much. Done too much.”

“Word.”

“Yes.”

“Yes, and yes.”

“Hear, hear!” said Bradley.

“And yet,” I went on, “I have done too little. Far too little.”

“Been there, Joe.”

“Been there, done that, Joe.”

“Done too little, Joe.”

“Always too little.”

“Always.”

“I have tried,” I said. “To do right. Like one of those knights of old I guess you might say. What did they call them?”

“Knights errant,” called Bradley, who was a nice guy, but he did like to show off his knowledge.

“Right,” I said. “Like a modern-day knight errant. But what has almost twenty years in this profession got me? A world-weariness that I carry around with me like a hundred pound sack of potatoes, and a three-pack a day habit of these –”

I held up the stub of the Philip Morris Commander I had been smoking, and dropped it to the floor. I stubbed it out with my worn brown brogans, which needed a shine, badly.

I reached into my suit coat (off the rack, Macy’s) and brought out a pint of Old Crow.

“And a pint-a-day habit of this stuff,” I said.

“Join the club, Joe.”

“Same here.”

“Me too, Joe.”

“Only one pint?”

I put the pint, which was only one-third full, back in my suit-coat pocket.

“I had a wife,” I said. “Once.”

“Only one?”

“Let him talk.”

“Yeah, you’ll get your turn, Burt.”

“Sorry,” said Burt. “I was out of line. I’m always out of line.”

I let them settle down, took out my cigarettes, shook one out. Lighted it with a hotel match.

“Do I even have to mention the adolescent daughter?” I said. “A daughter I don’t know how to be a father to?”

Nobody said anything, and I suspected I had really struck a chord this time, and that every one of these guys had daughters they didn’t know how to be a father to.

I went on, and, six cigarettes and a half-hour later, I felt as if I had said enough, more than enough, and yet not nearly enough. For this time.

“So I guess that’s all I got to say for now,” I said. “And I want to thank you guys for listening.”

Everybody clapped, and I went back to the semi-circle of folding chairs and sat down. The guys on either side of me patted me on the back.

“Thank you, Joe, for sharing,” said the thin man. “Who would like to speak next?”

A beat-up looking guy in his fifties raised his hand, and he shuffled up to the podium with his paper cup of coffee and his cigarette.

“My name is Jack,” said the beat-up guy. “I am a burnt-out detective.”

“Hi, Jack” said a dozen rough voices, the voices of men who had seen too much, done too much, and yet who had done far too little.

“Hello, Jack.”

“Hey, Jack.”

“Testify, my brother Jack.”

“Greetings, Jack,” said Bradley.

“Hello, Jack,” I said.

The Burnt-Out Detectives Group, by Horace P. Sternwall, an Ace Books “double”, published in tandem with Diary of a Hop Head, by Herman P. Sherman (Horace P. Sternwall), 1954; out of print.

Published on April 24, 2019 09:11

April 22, 2019

“Pete Willingham’s Conversion"

“Bless me, father, for I have sinned. A lot.”

“And how long has it been since your last confession, my son?”

The priest sounded Irish, which seemed like a good thing to Pete Willingham. The Irish priests in movies always seemed real kindly-like, like Barry Fitzgerald in Going My Way. He was glad he hadn’t got an Italian or a Polack priest, or God forbid a Kraut priest –

“My son?”

“Yeah, father?”

“I asked you how long it’s been since your last confession.”

“Well, that’s a little embarrassing, father. Can we like skip over that part?”

“You can tell me, my son. Thirty-three years a priest, believe me, I’ve heard pretty much everything.”

“Okay, you asked for it, father. I ain’t never been to confession before.”

“Oh.”

“Maybe you never heard that before.”

“Well, I hear it every year when children make their first confession, but I will admit I’ve rarely heard it from grown-up people, except of course in the case of converts. So am I to take it that you are indeed a recent convert to the Church.”

“Yeah.”

“And have you received instruction?”

“I got that little picture book, the St. Joseph’s Baltimore Catechism?”

“I see. But have you gone to a priest to receive instruction in the laws of the Church.”

“No. That I ain’t done. But I studied the catechism. Most of it. Ask me a question. Ask me who made me.”

“I don’t think this is quite the place or time for catechism study, my son.”

“God made me. I was right, right, father?”

“Yes, you were. May I ask you why you have decided to convert to Catholicism?”

“Because of this, father. What we’re doing here.”

“Confession, you mean?”

“That’s right, father. I need somebody to talk to. Can I tell you why?”

“Well, I’m sure there are other people out there in the pews waiting to make their own confessions –”

“I’ll make it quick, father.”

“Okay, my son. Go ahead, but try to be concise.”

“I just got out of the looney bin, six months at Bellevue. Three months at Riker’s before that. And before you ask, the charges were drunk and disorderly, public mischief, and incitement to riot. I told you I had plenty to confess.”

“Yes, you did.”

“So they let me out finally, and I went back to my regular stop, Bob’s Bowery Bar? That was where my last drunk and disorderly happened. You know the joint?”

“I think I’ve walked by there –”

“Good joint. So as soon as I got out of Bellevue, I went back to Bob’s, and I did what they told us to do in group.”

“Group?”

“Group therapy, father. They told us when we got out we should apologize to everybody we ever hurt. It’s part of what they call ‘the Program’.”

“I see.”

So I apologized to Bob the owner and all the other regulars, and I asked Bob if he would let me come in again. And he heard me out, and finally he said yeah, but I gotta keep a lid on it. No giving my opinions all the time, no butting into people’s conversations and arguing and shouting. In other words, keep my trap shut.”

“I see.”

“And it’s hard, father. It’s real hard keeping my trap shut. Back in the hospital I got to see this lady psychiatrist, Dr. Weinberg? And her I could talk to. I been seeing her off and on for years now, each time I get pinched for public nuisance or reckless endangerment or something, the judge keeps sending me back to Dr. Blanche. That’s her first name. Blanche. Weinberg. Jewish lady, but real nice. But here’s the thing, father, now I’m out on the street again, and if I wanted to talk to Dr. Blanche I’d have to pay her, unless of course I screw up again and the judge sends me back to her. But I ain’t got the money to pay her, father. I wish I did, but I don’t. So now I got no one to talk to. So I decided to become a Catholic so I could go to confession and have someone to talk to. So here I am. You want to hear my sins?”

The priest said nothing, and Pete waited. Pete was patient. You learned how to be patient in jail, and in the psycho ward, and on the streets.

After a minute the priest spoke.

“I’m going to ask you to come see me at the rectory, and to begin instruction in our faith.”

“Good. When you want me to come?”

“What’s a good time for you, my son?”

“I’m between jobs right now, father, so my calendar is completely clear.”

“Come to the rectory today then, let’s say four in the afternoon. Ring the bell, and tell the girl you have an appointment with Father Molloy.”

“I’ll be there, father. With bells on. You want to hear my sins now, or you want to wait till later? Reason I ask is it might take a while. I mean it might take a long while. Hours. Many hours, father.”

Pete Willingham’s Conversion, and Further Tales of the Bowery, by Horace P. Sternwall; a Pyramid Books “paperback original”, 1954; out of print.

Published on April 22, 2019 09:45

April 20, 2019

"Nobody Cares What You Think"

After Pete Willingham had served his latest three months at Riker’s, this time followed by a good six months in the psycho ward at Bellevue, the first thing he did when he got out on probation was to head over to Bob’s Bowery Bar.

It was about ten in the morning on a fresh April day, and the joint was not quite three-quarters full. Pete didn’t dilly-dally around but went right up to the bar, where Bob stood staring at him.

“Okay, Bob, before you throw me out I just want to say that as part of my program I am supposed to apologize to anybody I hurt in my life. So I want to apologize, for all them times I got out of hand, all them times you had to throw me out. And I deserved it. Even that last time when you threw me out and told me never to darken your door again. So I apologize.”

Bob didn’t say anything, but he took out one of those Parodis he smoked, and lighted it up. He tossed the match in an ashtray. Everybody in the bar was quiet.

“And all you other guys, too,” said Pete. “And, yes, you ladies. I want to apologize to all of ya.”

None of the guys and none of the women who were there said anything. They were probably taking their cues from Bob.

“So,” said Pete, “that being said, I want to ask you, Bob, to give me one last chance. Because I love this place. Ever since I come to the city from Wheeler’s Corners this place been like a second home to me. No, strike that, like a first home, ‘cause I ain’t got no other home.”

Actually he had a family and their home back in Wheeler’s Corners, a family that would probably take him back, albeit not with open arms or great enthusiasm, but Pete didn’t go into all that.

Bob took a draw on his Parodi, then spoke.

“I’ll give you one more chance, Pete. But listen to me now because I’m going to give it to you straight. Nobody cares what you think, Pete. About anything.”

“Wow,” said Pete.

“Nobody wants to hear your opinions. About anything.”

“Okay,” said Pete.

“And nobody wants you butting into their conversations so you can tell them what you think. Nobody cares, Pete. If you can accept this, you can stop in here sometimes, on a provisional basis.”

“Wow, thanks, Bob,” said Pete.

“But the moment I hear you raising your voice to anyone to tell them what you ‘think’, the flag comes down, and you are out of here.”

“Okay, Bob, I can do that. No loud voice.”

“Also none of that high-pitched wheedling stage-whisper voice.”

“I think I know what you mean. So I can talk, but just in normal tones.”

“And no gratuitous opinions. Nobody wants to hear your crap. If they do, they will ask you, but if I were you I wouldn’t hold my breath.”

“Okay,” said Pete.

“All right, sit down, and the first one’s on me. The usual bock?”

“The usual, Bob, thanks,” said Pete, and he settled up on a bar stool.

The people in the bar resumed their conversations. Bob gave Pete a mug of the house bock. The crisis was passed.

“Pound for pound,” said the Brain, to Pete’s right, speaking to that guy who wrote the cowboy poems, Howard Paul Studebaker, “the best baseball player ever was Ty Cobb, the Georgia Peach.”

Ty Cobb? thought Pete. That was outrageous. No way was Cobb a greater player than Babe Ruth, the Sultan of Swat, and he was just about to butt in and say so, when he saw Bob staring at him, almost like he had bribed the Brain to make such an outrageously false statement.

Pete made a fist of his left hand, and stuck his first knuckle between his teeth. He stared down into his untouched bock.

This was hard.

This was going to be very hard, maybe the hardest thing he had ever tried to do in his life.

Then the guy on his left – it was that movie director guy who liked to go slumming down here, Larry Winchester – said to the guy on his left, that actor guy, Angus Strongbow:

“Here’s what I consider the twenty-five best films ever made. The General. The Kid. Citizen Kane. Rules of the Game –”

And on he went with his boring list of so-called classics. Where were the Hoplaong Cassidy movies? What about Gene Autry and Roy Rogers? How about Ted Healy, or even better, Wheeler & Woolsey? What about every single Joe E. Brown movie?

Pete started to say something, but then he saw Bob, staring holes into Pete’s poor soul.

Pete took his knuckles away from his teeth, lifted his mug of bock and drained it all in one go.

And people wondered why he drank.

– Nobody Cares What You Think, and Other Tales of the Bowery, by Horace P. Sternwall, a Proletarian Books “paperback original”, 1954; out of print.

Published on April 20, 2019 08:03

April 18, 2019

"The First Job"

Tonight was the night.

The night when Billy Baskins would officially begin his career as an elegant international assassin. The Marie dame had told him that her husband Jerry was taking her to Bob’s Bowery Bar that night for dinner and drinks for her birthday, and that Jerry would get roaring drunk the way he always got when he went to Bob’s. When they left the bar, which probably wouldn’t be until Bob cut Jerry off, they would turn left on the way to their trap up the block, and all Billy had to do was wait in the alley next to Bob’s and then do the deed. It would look like a robbery, and that’s what Marie would tell the cops. Besides the fifty bucks Marie had promised Billy, she told him he could keep whatever money Jerry had left in his wallet, if he had anything left.

Billy got to Bob’s early, and, sure enough, after a while Marie came in, with her husband, or at least Billy assumed he was her husband. He was a big guy, and a loud guy. Billy didn’t mind that he was loud so much, but the big part gave him pause, because Billy didn’t have a gun. He would really have to find a gun for his next job, but right now all he had was his old pen knife, and the more he thought about it, the more he thought the pen knife might not do. He would have to find some other way to bump off the guy. Well, nobody ever said being an assassin was going to be easy. He would just have to find a way.

Billy was drinking the house bock, but he took it easy. He didn’t want to get too drunk, not for his first “hit”. He was sitting on the other side of the corner down at the end of the bar, where he could keep an eye on Marie and Jerry, who sat about midway at the bar. Marie and Jerry drank, and laughed, they ate. It looked like they were going for the Wednesday night two-for-one hot dog special. Marie ate four of the dogs, her husband Jerry must have eaten a dozen of them before he was through. Billy got hungry, so he had a couple of the dogs himself.

The hours went by. Marie and Jerry drank, and laughed. They sure didn’t look like a couple that didn’t get along, but, who knows, thought Billy. People were weird. They were weird back home in Wheeler’s Corners and they were weird here in the big city.

When would Marie and Jerry leave? Despite himself, and despite the fact that he tried to pace himself, Billy realized he was getting drunk. Finally, he nodded off, and he was awakened by Bob rapping that Marine Corps ring of his on the bar top.

“Hey, buddy. Wake up.”

Billy started awake.

“Wha?”

“I said wake up and go home, pal. This is not a hotel.”

Billy looked down the bar. Marie and Jerry were still there, thank God.

“Sorry!” he said to Bob. He glanced down at the change in front of him, separated two quarters and shoved them toward Bob, and pocketed the remainder.

“Wow, two whole quarters,” said Bob. “Thanks, big spender.”

“You’re welcome,” said Billy, with his small-town politeness, and he quickly climbed off his bar stool and staggered out.

He turned left outside the bar, and there was the dark alley. Now he just needed to find something to bump off Marie’s husband with. He rooted around in the darkness, and he found quite a few empty beer and wine bottles, but he figured he needed something more lethal, and finally he found a pile of rubble with some bricks in it, and he picked out a nice one. This would do, this would do just fine. He went back to the entrance of the alleyway and waited. He got sleepy again, so he sat down with his back against the wall, with the brick on his lap. Fortunately, this was the Bowery, and there was nothing unusual about a man sitting in an alleyway.

He would just rest his eyes for a minute.

Suddenly he started awake again. It was those voices, the loud, laughing voices of Marie and Jerry!

Billy shook his head the way a dog does when it wakes up, and he pulled himself to his feet. The voices got louder. He had the brick in his hand. He heard the voices, the laughter, getting louder, coming closer to the entrance to the alleyway.

It was now or never. Billy raised the brick high and as the man and woman staggered arm in arm past the corner of the alley Billy brought the brick down as hard as he could.

And he smashed the skull of poor drunk Marie. “What the hell?” said the big guy, Jerry, Marie’s husband, staring drunkenly down at Marie’s crumpled body.

What could Billy do? One thing he had learned from his magazine stories was that a professional assassin always completes his contracts, so he raised the brick again and brought it down on the big man’s head.

Billy walked away, as quickly as he could without running, and it wasn’t until he reached the corner of the block that he remembered to drop the brick.

His first job, and he wouldn’t make a dime from it, but at least he had gotten his feet wet. Next time he would try to do better.

– The Last of the Elegant International Assassins, by Horace P. Sternwall, a Midway Books “paperback original”, 1952; one printing, never republished.

Published on April 18, 2019 10:12

April 16, 2019

"Nobody's Perfect"

Everybody’s got to croak sometime, and after sixty-three years of drinking, smoking, eating, whoring, roaring, sleeping and dreaming and doing it all again, finally cirrhosis of the liver took Michael J. “Mickey” Finn one cold day in the charity ward of Bellevue Hospital.

Much to his surprise he found himself at the bottom of the hill at the top of which stood God’s house.

“Well, here goes nothing, Mickey,” he said to himself. “Let’s get this over with.”

He walked up the winding brick path and up onto the porch where St. Peter sat at a little table with his great leather ledger.

“Name?”

“Michael Joseph Finn, but me friends call me Mickey. Call me Mickey, St. Peter.”

“Just one moment, Mr. Finn.”

St. Peter took his time, lighting his pipe with a kitchen match, and slowly paging through the enormous ledger.

“Nice day, ain’t it?” said Mickey. “Cool, but not too cool, like jacket weather.”

St. Peter wore an old, colorless canvas jacket. Looking down at himself, Mickey was glad to see he was wearing his favorite old grey flannel suit, Brooks Brothers, bought at the Goodwill for five bucks in 1937. It had been several sizes too large for him at the time, but with his diet of bock beer and hot dogs he had grown into it over the years.

“Now some people like hot weather,” said Mickey. “Some people like cold weather. Me, I like this kinda weather. Just a little brisk. Like fall, or early spring.”

“Oh, boy,” said St. Peter.

“What?”

“Jesus Christ,” said St. Peter.

“What, are you reading about me in there?”

“Are you kidding me?”

“You sure you got the right Michael Joseph Finn? It might be some other guy’s life you’re looking at there.”

“Never held a steady job.”

“Hey, St. Peter, you try working one of those stupid jobs all day. Suck the life right out of you.”

“Fathered four children by four different mothers.”

“Excuse me, Peter, but man to man, hey, it takes two to tango, you know what I mean? Those four broads all knew what they was in for. I never claimed to be no Ronald Colman.”

“What does that even mean?”

“Ronald Colman – like, you know, noble like. Maybe I shoulda said Leslie Howard. Me, I was always more like the Erroll Flynn type, y’know?”

“Unbelievable.”

“What? What’s unbelievable?”

“The sheer number of hours of your life you spent drinking in bars, particularly this ‘Bob’s Bowery Bar’.”

“Yeah, that was my regular stop, I’ll admit, ever since back when it was a speak. Good joint. And that Bob, he runs a taut ship, y’know? Anybody causes any trouble, you’re out on your ear.”

“So this was your life. Drinking. Smoking. Working as little as possible. Avoiding responsibilities.”

“Hey, I never said I was perfect.”

St. Peter sighed, shook his head.

“I can’t even look at this anymore,” he said, and he closed the book. He drew on his pipe, but it had gone out. He tapped the dead ashes into a big glass ashtray.

“Hey, St. Peter, can I just say a few words in my own defense?”

St. Peter sighed again, but said nothing. He began to refill his pipe from a worn old leather pouch.

“Okay,” said Mickey. “I’m gonna take that as a yes. Number one, I never killed nobody. Number two, I never hurt nobody. Number three, whenever I had a few bucks to spare, I would give it to one of them dames that I knocked up and tell her to buy the kid a toy or something. Number four – well, I guess there ain’t no number four. All I got to say is nobody’s perfect and I never said I was. And if that’s a crime, well, okay, do what you gotta do.”

St. Peter lighted his pipe with a kitchen match, and looked out over heaven and all creation.

Mickey was led through a series of large rooms and long corridors and finally into a barroom not unlike Bob’s Bowery Bar.

“Sit anywhere you like,” said the docent, “and a server will be right with you.”

Over at one end of the long bar, Mickey saw some of the late-departed old gang from Bob’s: old mushmouth Joe, Gerry “The Brain” Goldsmith, Fat Angie the retired whore, George the Gimp, the old guy they called Wine, Tom the Bomb. He squeezed in between old Joe and Gerry.

“You?” said Gerry. “This joint is going downhill.”

“Ha ha,” said Mickey.

What did he care? He had made the grade. By the skin of his teeth, but he had made it.

He ordered a bock.

– Nobody’s Perfect, and Other Stories of the Forgotten Man and Woman, by Horace P. Sternwall; a Pyramid Books “paperback original”, 1954; out of print.

Published on April 16, 2019 11:17

April 15, 2019

"Our Lady of Sorrows"

Wendell admired the silent and solitary dark-haired girl in Bob’s Bowery Bar for an entire summer and autumn and the beginning of winter before he almost got up the nerve to say a word to her.

She stood out like a sore thumb amidst the dregs of humanity that made up the rest of the clientèle of the bar. No, that was a poor image; everyone else in the place was a sore thumb, and she was the one perfect thumb: another poor image, but, alas, Wendell could summon up nothing better. It was this difficulty in casting the tumultuous chaos of actual life into words which made the writing of Wendell’s epic poem such an impossible task.

She wasn’t there every night, and Wendell knew she wasn’t because he himself was there every night. He would come home from his dreary job at Amalgamated Public Relations, he would work on his poem for an hour, and then, exhausted, he would grab a book or a magazine and stagger down the four flights of stairs and then around the corner to Bob’s where he always ordered the same thing, a glass of the house bock beer that Bob brewed in the basement. The bock was rich and dark, full of the flavors of an eternal rainy day in early winter, barely carbonated, and tasted just as good after you had nursed it half an hour and it had gone completely flat.

When the dark-haired beauty did come in, she always sat alone, at the bar, and she always read a book, or a magazine or paper. She wore glasses to read, and sometimes she took them off, rubbed her eyes, looked about her with an impassive expression, then replaced the glasses on her nose and resumed her reading. Wendell couldn’t be sure, but it looked as if her regular drink also was the house bock.

One evening Wendell dared to ask the waitress Janet about the mysterious young woman.

“What do you want to know?” said Janet.

“What do you know about her?”

“Are you in love with her?”

“How can I be in love with her if I’ve never spoken to her?”

“All I know is her name is Lisa, she always sits alone and reads a book, she doesn’t talk to anybody, and if anyone tries to bother her, Bob just raps that Marine Corps ring of his on the bar top and tells them to leave the lady alone. He don’t want to lose the one classy female regular he’s got, y’know?”

“Would Bob tell me to leave her alone if I tried to talk to her?”

“Not if you’re not a jerk about it. Give it a try, Wendell.”

“You really think I should?”

“What do you have to lose, except maybe your pride if she tells you to leave her the hell alone?”

It was another two weeks before he got up the nerve, or almost got up the nerve.

It just so happened that when he came into the bar that evening the only empty bar stool was directly to the left of the beautiful young woman.

As usual, she was reading. It was Daniel Deronda, by George Eliot.

Here was an opening. He could ask her about Daniel Deronda, a book which, by the way, he had never read. But first he had to prepare himself. How to phrase his opening line? How’s your book? No, that was lame. There must be a better way. He had been so tired that he had forgotten to bring a book or magazine or newspaper with him, and he felt horribly exposed. He could never understand how people could go into a bar with nothing to read, just staring at the rows of bottles behind the bar, or into the mirror on the wall above the bottles, staring into one’s own lugubrious and pathetic face…

“No book tonight?”

She had spoken. She had spoken to him.

“Uh, no,” said Wendell. “I was so tired tonight that I forgot to bring something to read, and I was just thinking about how I can’t understand how people can sit in bars without anything to, you know –”

“Read.”

“Yes,” he said.

“I’ve noticed that every time I’ve seen you in here you’ve had your nose buried in a book or a magazine.”

“Yes,” he said, “heh heh. I like to read.”

“Me too. I live with three noisy girls who do nothing but chatter and play the radio or the record player, so I come here to read in peace.”

“Well, I have no roommates, but I come here anyway, just to get out of my apartment.”

The ice had been broken.

Wendell was an unobservant Presbyterian and Lisa a fallen-away Catholic, but for her mother’s sake they were married, the following June, at Our Lady of Sorrows over on Pitt Street.

– Our Lady of Sorrows, and Other Tales of Bob’s Bowery Bar, by Horace P. Sternwall, a Demotic Press paperback original, 1954; out of print.

Published on April 15, 2019 10:16

April 13, 2019

"MacGregors"

Millie had gotten fired from another job, and as usual it was because of a man. This job had been as “editorial assistant” for a leftist weekly called The Rosa Luxembourg Review. It didn’t take long for Millie to find out what the editor really wanted her to assist him with, and this time she got so mad that when he tried to pull her down on his lap she slugged him with the little bust of Karl Marx he kept on his desk.

“And you call yourself a Communist,” she said, as he sat there in his swivel chair, holding a handkerchief to his bleeding head and crying.

“How many times have I told you,” he said between sobs, “I am a Trotskyite, not a Communist.”

“Well, you’re a disgrace to Leon Trotsky and to leftists everywhere.”

“And you’re a dyke.”

“I’ve heard that one before, from other chumps who thought they were God’s gift. I want a whole month’s severance pay, and I want it now, and in cash.”

“What I should do is call the cops and have you arrested for assault and battery.”

“What I should do is call your wife and tell her what a swine you are.”

“I’ll write you a check for two weeks’ severance pay.”

“You will give me cash for a month’s severance pay. That’s a hundred bucks.”

“Millie, I don’t keep that kind of cash in the office. What do you think this is? Forbes? Here, I’ll write you a check for a hundred right now.”

“And then put a stop on it as soon as I’m out of the office?”

“But, Miss Murphy, I’m telling you I don’t have a hundred dollars in cash in this office.”

“How much do you have in your wallet?”

“Oh, Jesus.”

He took out his wallet. He was still sniffling, still holding his handkerchief to his bleeding head. He laid the wallet on his desk.

“Here, you’re welcome to whatever is in there, now please take it and go.”

She picked up the wallet, opened it, took out the cash that was in it.

“Twelve bucks? You must be kidding me.”

“I edit a leftist literary weekly. How much money do you think I make?”

“I don’t know, how big is the allowance your parents give you?”

“I don’t get an allowance from my parents.” (Actually it was a trust fund.)

“Then how do you afford to live in a townhouse in Sutton Place?”

“It’s a duplex, not a townhouse, and my wife’s parents gave it to us.”

“Your wife’s capitalist pig parents?”

“Look, please, Millie, take the twelve dollars, and I’ll write you a check for a hundred and I won’t report you to the police and you won’t call my wife and we’ll call it even. I’ll even give you a letter of recommendation. Miss Murphy, are you listening to me?’

She was looking over at his golf bag in the corner.

“Nice set of clubs,” she said, putting the twelve dollars up her sleeve. “What do you go around in?”

“Well, it depends on the course, but – what are you doing?”

She went over to the clubs.

“MacGregors. What did you pay for these?”

“They were a birthday gift from my wife last month, and I’m sure I don’t know – wait, what the – Millie –”

She hoisted the bag onto her shoulder.

“Now we’ll call it even,” she said, and she walked out the door with the golf clubs.

His wife would kill him. How would he ever explain the missing clubs? Wait, he could say he left them in the back seat of his car while he was having lunch, and he forgot to lock the car door, and someone had stolen them. That’s what he would say. But she would still kill him.

– “MacGregors”, from Tales of a Working Gal, by Harriet Pierce Stonebrake (Horace P. Sternwall); The Working Woman’s Press, 1941; out of print.

Published on April 13, 2019 07:59

April 12, 2019

"The Toll"

Janet was resting her dogs up on the arm of the couch and reading one of the leftover movie magazines that Doc Schwartz down at the drug store always saved for her when Bub and Bubbles came in the door, and Bub had a bloody nose.

“Now what?”

“It was them boys on the corner,” said Bubbles. “They said we had to pay them a nickel each every time we walked past the corner from now on, and Bub said we didn’t have no nickels, and even if we did we still wouldn’t give ‘em nothin’.”

“Didn’t have ‘any’ nickels,” said Janet, “and ‘wouldn’t give them anything’.”

“That’s what I said,” said Bubbles.

Janet put down the Photoplay and swung her legs to the floor.

“Get my apron, Bubbles. I got to go to work. Bub, you go in and wash your face off, and then you both come with me.”

A few minutes later the three of them walked down to the corner of the Bowery and Bleecker. A half-dozen young boys in t-shirts and blue jeans were slouching there.

“Which one of you tough guys punched my kid brother in the nose?”

“It was me,” said the kid named Tommy. “What’re you gonna do about it?”

“Come here, Tommy,” said Janet, “I want to talk to you.”

The kid came closer, all cocky. Janet stood there with both her hands in the pockets of her waitress apron.

“So you like to beat up little kids half your size, huh?”

“This is our corner. Anybody walks by this corner gotta pay the toll.”

“Okay, here’s your toll.”

So quick that nobody saw it coming her right fist came out of her pocket with the brass knuckles and hit Tommy square in the nose. He sat down on the pavement, holding his hands over his nose with the blood pouring down, and he was sobbing.

“Anybody else want to collect the toll?” said Janet.

Nobody said a word, and Tommy continued to sob.

“Anybody touches my brother or sister again, I come back here with a gun,” she said.

Nobody said anything, Tommy sobbed.

Janet turned around and walked away, and Bub and Bubbles went with her. Outside Bob’s Bowery Bar she said, “There’s tuna macaroni salad in the icebox, and put the leftovers back in the icebox when you’re done and wash your dirty dishes.”

“Hey, Janet,” said Bubbles, “you ain’t got no gun, do ya?”

“I don’t have ‘any’ gun,” she said. “But those little schlimazels don’t know that.”

– The Toll, and Other Tales of the Underclass, by Horace P. Sternwall, the Working Person’s Press, 1951; first edition.

Published on April 12, 2019 11:07