Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 51

September 20, 2014

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for September 21, 2014

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for September 21, 2014

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide ranging and expansive terrain of Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews of: Bilal Tanweer’s The Scatter Here is Too Great (Harper, 2014); Farzana Doctor’s Six Metres of Pavement (Dundurn, 2011); Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp (University of Utah Press, 2014); Ed Lin’s Ghost Month (Soho Crime, 2014); Michael Cho’s Shoplifting (Pantheon, 2014).

A Review of Bilal Tanweer’s The Scatter Here is Too Great (Harper, 2014).

Bilal Tanweer’s ambitious and formally inventive debut The Scatter Here is Too Great follows a revolving cast of characters who are linked by one tragic event: a bomb blast in Karachi, Pakistan that leaves many injured and dead. The bomb blast is a red herring, though, and that fact is only made clear in the novel’s final sequence. Indeed, readers might be looking too much into the source of the blast, what caused it, and the motivations for its detonation, without realizing that we’re missing the point. Tanweer’s true protagonist in the city of Karachi, how it has been imagined and remade especially in light of terrorist discourse and the projection of Islamic Fundamentalism on countries in that region. Tanweer’s project, then, is to particularize experience and texturize how the city is interfaced and understood from a variety of different perspectives. Called a “novel in stories,” it follows a number of different characters, shifting narrative perspectives constantly (especially between first and second person). Each section of the novel seems to slightly advance the story, moving us closer and closer physically to the blast. One of the most important connections it seems is the place of the writer in this modernizing city. Indeed, one of the returning figures is a subeditor who is tasked with understanding how to interface with the many facets of Karachi and demystifying its representations. This character muses: “All these stories, I realized, were lost. Nobody was going to know that part of the city as anything but a place where a bomb went off. The bomb was going to become the story of this city. That’s how we lose the city—that’s how our knowledge of what the world is and how it functions is taken away from us—when what we know is blasted into rubble and what is created in its place bears no resemblance to what was and we are left strangers in a place we know, that we ought to have known. Suddenly, it struck me that that’s how my father experienced this city. How, when we walked this city, he was tracing paths from his memory to the present—from what this place had been to what it had become” (165). It would seem that the writer in all of his metafictional conceits is taking himself to task for this very same purpose, trying to create some sort of narrative that links time and place to the urban experience. The form of the novel itself is then part of the key to understanding Tanweer’s rhetoric: not everything will cohere, but the fragmentation is part of the complexity and the beauty of Karachi, a city that we understand is more than a bomb, more than Islamic fundamentalism, more than a site that has been determined to be a terrorist stronghold. I agree with other reviewers that the story can sometimes meander in ways that are distracting to readers, but Tanweer’s prose is so compelling, especially the philosophical renderings that appear in the opening and closing chapters that you’ll be lulled into Karachi’s representationally rich character configurations, including an ambulance driver undone by two figures who seem to represent the end of the world and two young lovers who seek to find a place to be alone in a city with too many eyes.

Buy the book here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Scatter-Here-Too-Great/dp/0062304410/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=undefined&sr=8-1&keywords=the+scatter+here+is+too+great

A Review of Farzana Doctor’s Six Metres of Pavement (Dundurn, 2011).

The great thing about the archive of “literatures penned by writers of Asian descent in English” (otherwise known as Asian Anglophone) is that the depth of its reach seems unending. There’s always a new writer that I find that I feel like I should have already heard of but haven’t, which brings me to Farzana Doctor, a queer Asian Canadian writer, who has published two novels. I review Six Metres of Pavement here, which is told in the third person perspective and primarily follows two characters: Ismail Boxwala, a Muslim Indo Canadian who is divorced, something that occurs in the wake of a tragic accident. He had left his infant daughter in his car while at work and Zubeida (nicknamed Zubi) dies from sun exposure. His wife, Rehana, attempts to assuage to the situation by suggesting they have another child, but Ismail suffers erectile dysfunction, no doubt related to his anxiety that he cannot possibly father another child, fearing that he may again be negligent. Celia Sousa has just moved into the neighborhood with his daughter Lydia and her son-in-law. Celia is in mourning; her mother and her husband Jose have both passed away recently, and she struggles to find a way out of her daily melancholy. It’s been about eighteen years since Zubi died when the novel opens, and Ismail struggles with a drinking habit. He falls into meaningless sexual dalliances with women at the local bar; he also strikes up a friendship and sexual relationship with a local there named Daphne, who ends up proclaiming her queerness and then joining an AA group. It is Daphne who encourages Ismail to take a creative writing class, and it is there that Ismail makes a strong friendship with a fellow classmate Fatima, even after he questions whether or not to stay enrolled (Daphne quickly drops out of the class leaving Ismail abandoned). It’s quite clear from the get-go that Doctor is setting up a romance plot between Ismail and Celia, and it takes too long to get there, but fortunately Doctor also provides us with an interesting friendship plot that occurs between Fatima and Ismail. Both Fatima and Ismail hail from similar ethnic backgrounds (though Fatima is a generation younger) and when Fatima is thrown out of the house, with no support for her livelihood, education, and other such things, she has to increasingly rely on Ismail’s help just to survive. Fatima, as we soon discover, is a feminist, an anticolonialist, steeped in academic rhetoric concerning social inequality, and most importantly for our understanding: she’s a lesbian. gasp To a certain extent, Doctor’s structure strangely enough replicates a heteronormative family unit, as at one point, it seems possible that Ismail will marry Celia, and that Fatima has become a kind of surrogate daughter (a kind of imperfect replacement for Zubi). Though the novel takes too long to set up the connection between Celia and Ismail—indeed, Doctor is a talented writer and it’s perfectly clear that both characters are traumatized, so we could have used some editing in the first 100 pages—the sociopolitical import of the novel is obvious, and the novel especially provides the kind of ending not usually fit for so many characters who exist on society’s fringes. Somehow, Doctor manages to provide us with a convincing ending where outcasts and pariahs do not necessarily succumb to violent deaths and premature termination from the plotting.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Six-Metres-Pavement-Farzana-Doctor/dp/1554887674/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408805340&sr=8-1&keywords=six+metres+of+pavement

A Review of Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp (University of Utah Press, 2014).

What an absolutely amazing book! There can be no other estimation for such an important document that is part of the long-standing recovery effort related to the Japanese American internment experience. Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp is a mixed-genre, creative nonfiction memoir that employs photographs, narrative, and watercolor paintings to represent and to give life to Havey’s experiences as a ten-year old who first must endure living at an assembly center and then in the harsh conditions of Colorado’s Amache internment camp. The narrative is straightforward enough and one that recalls other internment works (such as Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile, Mitsuye Yamada’s Desert Run, etc) in its depiction of the monotony, the psychic struggles, and the everyday desultory life of languishing in what is basically an inhospitable place. There are moments of pleasure and even happiness, which erupt in Havey’s narrative in unexpected places: the light of the sun when it hits a cold and barren landscape or the return of a father from long periods away (working outside of the internment camp in order to escape its confines and to provide for the family). In other moments, we constantly see how the internees make the most of meager circumstances, continuing to persevere despite their imprisonment. Again, it is the minor moments which surface as a brutal and stark reminder of indomitable spirits, such as the desire of Havey’s mother to continue polishing the pot-bellied stove, or the move to decorate the ramshackle interiors of the interment barracks. But, what makes Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp so dynamic and so indispensable is its visual catalog, one that includes photographs (indeed, as Havey notes, in the last year of the internment camp, a camera was able to be used by residents) and watercolor paintings that Havey created over time to represent her experiences. The watercolor paintings are notable in that they are far from directly representational: most have abstract and symbolic qualities that seem exactly appropriate as a kind of formal conceit that illuminates such a fragmenting and harrowing experience.

Here’s a link to one of the watercolor paintings:

http://artistsofutah.org/15Bytes/index.php/lily-havey-reads-gasa-gasa-girl-goes-to-camp/

Havey often uses pastels (an effect to a certain extent of the watercolor approach), which ends up also functioning within a light scheme that comes off as ghostly. As these watercolors accompany the direct narrative of the internment, a multifaceted portrayal emerges that reminds us of the continued work that needs to be done in order to reconsider how this experience impacted so many Americans (Japanese in ethnicity and otherwise). Finally, I would like to remark on the production quality of this book: the pages used are the kinds found in art and painting studies, with a glossy finish. Certain to stand the test of time, one must pick up this essential and new addition to the canon of internment literatures.

Internment literatures based upon place:

Topaz: Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile; Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine

Minidoka: Mitsuye Yamada’s Camp Notes and Other Writings

Manzanar: Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s Farewell to Manzanar

Heart Mountain: Lee Ann Roripaugh’s Beyond Heart Mountain

Poston: Cynthia Kadohata’s Weedflower

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Gasa-Girl-Goes-Camp-Behind/dp/1607813432/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1410191557&sr=8-2&keywords=gasa+gasa+girl

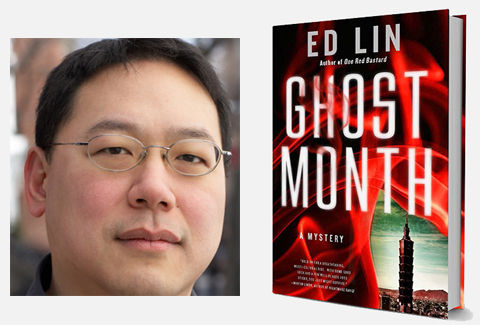

A Review of Ed Lin’s Ghost Month (Soho Crime, 2014).

So when I picked up Ed Lin’s Ghost Month, I automatically assumed it was another book in Lin’s Robert Chow’s detective series (which includes This is a Bust, One Red Bastard, and Snakes Can’t Run). Instead, we have another book entirely, which revolves around Jing-nan (aka Johnny), a twenty-ish character languishing in a life he never wanted (inheriting the debts of his father and running a stall out of Taipei’s famed Night Market) living in a country he doesn’t want (Taiwan). The opening of the novel begins inauspiciously enough with Jing-nan discovering that the love of his life Julia Huang has been murdered. Jing-nan hadn’t kept in touch with Julia because of a promise he made that he would only marry her if he had established himself in a career and with full preparedness for life as a married couple. When he must leave UCLA without finishing his degree and returns to Taiwan, but not soon after, his mother dies in a tragic accident and his father dies just three weeks later due to health issues. Needless to say, Jing-nan’s life is turned upside down. He takes on the family business, while realizing that must pay back the debt his father had accrued over time. Thus, his romance with Julia is effectively dead, and he never hears about Julia until the news that a betel-nut stand worker has been found killed. This betel-nut stand worker is none other than Julia Huang. For about one hundred pages of the novel, Lin employs Jing-nan as the perfect narrator to welcome a reader with little understanding of Taipei. Jing-nan carefully and meticulously lays out the density of the city, its cultural particularities, and more importantly, its underground and unofficial economies. Toward the ending of this longer than usual preamble to the noir-plotting, he visits Julia’s family as a mode of honoring her memory. They beseech Jing-nan to find out more about the mysterious circumstances of Julia’s death and though reluctant, Jing-nan agrees. On the way out of the house, he is accosted by a stranger who warns him not to investigate. Later on, this stranger reappears and makes the same warning and punctuates his threat with ominous promises of physical harm and death. Thus begins the noir-plot that readers might have been waiting for, but Lin is really balancing more than one narrative here. On one level, the novel is really a character study of Jing-nan, who simultaneously comes to tell us about the complicated historical and social texture of Taiwan, which includes tensions with aboriginal tribes, the continuing standoff with mainland China, as well as the national drive to modernize and to displace older forms of commerce and culture. On the other, Lin introduces the noir plot as a way to get at some of these social issues and to some extent, then, this mystery doesn’t function as seamlessly as other texts that stick more closely to formula structures. My assessment is no means a critique of Lin’s work, which is multifaceted and benefits from the trademark humor that we’ve come to expect in his writings, but rather to elucidate the varied workings of this novel. Though Jing-nan’s fidelity to solving Julia Huang’s murder can stretch the bounds of credulity, the novel succeeds primarily due to Lin’s construction of a flawed but intriguing noir anti-hero, and we can see this novel as the start of another series.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Ghost-Month-Ed-Lin/dp/1616953268/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1410801485&sr=8-1&keywords=ed+lin+ghost+month

A Review of Michael Cho’s Shoplifting (Pantheon, 2014).

In Shoplifting, Asian Canadian graphic novelist Michael Cho brings us a poignant, nuanced narrative of a young woman trying to figure out her path in life. Our protagonist is Corinna Park, who may or may not be Asian American (an issue I’ll come back to later). She works for an advertisement agency in New York City, but finds her job less than fulfilling. The narrative starts on a day when she’s in a boardroom meeting coming up with an advertising campaign for a perfume that will be marketed to 9 year old girls. She makes an off-color remark that gestures to the sense of ennui that she feels working in a company that is far from her passion. As an undergraduate, Corinna majored in English and thought that she’d one day write novels. Instead, she feels lonely, socially anxious, and generally finds her job desultory. This graphic novel is a coming-of-age that begins when Corinna is brought in by the head of the company and told to rethink why she is at the advertising agency. The title refers to an illicit habit that Corinna maintains whenever she is at the local grocery store. She manages to shoplift a magazine by inserting it in between the pages of a newspaper. She doesn’t provide a reason for why she does it; indeed, she doesn’t lack the money to buy the newspaper but it gives her a kind of thrill. The shoplifting is of course a larger metaphor for the fact that Corinna needs a jumpstart, some sort of obvious sign to move into a new occupation or life trajectory. Fortunately, the graphic novel provides a conflation of different events that lead Corinna to make a monumental decision. Cho’s art has a nice cartoon-style to it. The production design team also saw fit to use a four-toned color scheme system, where pink is mixed in with grays, blacks, and whites.

The use of pink to structure the color is an interesting one and gives the graphic narrative a kind of lighter feel to it than the content of the story would probably allow for on its own. Cho is particularly effective at rendering the alienation that can come with living in a metropolis: Corinna is often framed in scenes with a ton of other individuals, whether commuting by subway or at some sort of gathering. A particular favorite detail of mine was Cho’s focus on internet dating, a quagmire of hilariously bad profiles that Corinna must sift through when she gets home. But, perhaps, the most intriguing element is Cho’s choice to veil Corinna’s ethnic background. With a Korean surname, it would seem very possible that she’s Asian American, but there’s nothing contextually provided that would determine this with any sort of certitude. It brings to mind the question of how race gets represented in the visual register and how graphic novels present more avenues for cultural critics to attend to the complexities of racial formation. A wonderful work, the first I hope of many more by Cho. Certainly, a book I will adopt for future classroom courses on the graphic novel.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Shoplifter-Michael-Cho/dp/030791173X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1409183592&sr=8-1&keywords=michael+cho

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide ranging and expansive terrain of Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews of: Bilal Tanweer’s The Scatter Here is Too Great (Harper, 2014); Farzana Doctor’s Six Metres of Pavement (Dundurn, 2011); Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp (University of Utah Press, 2014); Ed Lin’s Ghost Month (Soho Crime, 2014); Michael Cho’s Shoplifting (Pantheon, 2014).

A Review of Bilal Tanweer’s The Scatter Here is Too Great (Harper, 2014).

Bilal Tanweer’s ambitious and formally inventive debut The Scatter Here is Too Great follows a revolving cast of characters who are linked by one tragic event: a bomb blast in Karachi, Pakistan that leaves many injured and dead. The bomb blast is a red herring, though, and that fact is only made clear in the novel’s final sequence. Indeed, readers might be looking too much into the source of the blast, what caused it, and the motivations for its detonation, without realizing that we’re missing the point. Tanweer’s true protagonist in the city of Karachi, how it has been imagined and remade especially in light of terrorist discourse and the projection of Islamic Fundamentalism on countries in that region. Tanweer’s project, then, is to particularize experience and texturize how the city is interfaced and understood from a variety of different perspectives. Called a “novel in stories,” it follows a number of different characters, shifting narrative perspectives constantly (especially between first and second person). Each section of the novel seems to slightly advance the story, moving us closer and closer physically to the blast. One of the most important connections it seems is the place of the writer in this modernizing city. Indeed, one of the returning figures is a subeditor who is tasked with understanding how to interface with the many facets of Karachi and demystifying its representations. This character muses: “All these stories, I realized, were lost. Nobody was going to know that part of the city as anything but a place where a bomb went off. The bomb was going to become the story of this city. That’s how we lose the city—that’s how our knowledge of what the world is and how it functions is taken away from us—when what we know is blasted into rubble and what is created in its place bears no resemblance to what was and we are left strangers in a place we know, that we ought to have known. Suddenly, it struck me that that’s how my father experienced this city. How, when we walked this city, he was tracing paths from his memory to the present—from what this place had been to what it had become” (165). It would seem that the writer in all of his metafictional conceits is taking himself to task for this very same purpose, trying to create some sort of narrative that links time and place to the urban experience. The form of the novel itself is then part of the key to understanding Tanweer’s rhetoric: not everything will cohere, but the fragmentation is part of the complexity and the beauty of Karachi, a city that we understand is more than a bomb, more than Islamic fundamentalism, more than a site that has been determined to be a terrorist stronghold. I agree with other reviewers that the story can sometimes meander in ways that are distracting to readers, but Tanweer’s prose is so compelling, especially the philosophical renderings that appear in the opening and closing chapters that you’ll be lulled into Karachi’s representationally rich character configurations, including an ambulance driver undone by two figures who seem to represent the end of the world and two young lovers who seek to find a place to be alone in a city with too many eyes.

Buy the book here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Scatter-Here-Too-Great/dp/0062304410/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=undefined&sr=8-1&keywords=the+scatter+here+is+too+great

A Review of Farzana Doctor’s Six Metres of Pavement (Dundurn, 2011).

The great thing about the archive of “literatures penned by writers of Asian descent in English” (otherwise known as Asian Anglophone) is that the depth of its reach seems unending. There’s always a new writer that I find that I feel like I should have already heard of but haven’t, which brings me to Farzana Doctor, a queer Asian Canadian writer, who has published two novels. I review Six Metres of Pavement here, which is told in the third person perspective and primarily follows two characters: Ismail Boxwala, a Muslim Indo Canadian who is divorced, something that occurs in the wake of a tragic accident. He had left his infant daughter in his car while at work and Zubeida (nicknamed Zubi) dies from sun exposure. His wife, Rehana, attempts to assuage to the situation by suggesting they have another child, but Ismail suffers erectile dysfunction, no doubt related to his anxiety that he cannot possibly father another child, fearing that he may again be negligent. Celia Sousa has just moved into the neighborhood with his daughter Lydia and her son-in-law. Celia is in mourning; her mother and her husband Jose have both passed away recently, and she struggles to find a way out of her daily melancholy. It’s been about eighteen years since Zubi died when the novel opens, and Ismail struggles with a drinking habit. He falls into meaningless sexual dalliances with women at the local bar; he also strikes up a friendship and sexual relationship with a local there named Daphne, who ends up proclaiming her queerness and then joining an AA group. It is Daphne who encourages Ismail to take a creative writing class, and it is there that Ismail makes a strong friendship with a fellow classmate Fatima, even after he questions whether or not to stay enrolled (Daphne quickly drops out of the class leaving Ismail abandoned). It’s quite clear from the get-go that Doctor is setting up a romance plot between Ismail and Celia, and it takes too long to get there, but fortunately Doctor also provides us with an interesting friendship plot that occurs between Fatima and Ismail. Both Fatima and Ismail hail from similar ethnic backgrounds (though Fatima is a generation younger) and when Fatima is thrown out of the house, with no support for her livelihood, education, and other such things, she has to increasingly rely on Ismail’s help just to survive. Fatima, as we soon discover, is a feminist, an anticolonialist, steeped in academic rhetoric concerning social inequality, and most importantly for our understanding: she’s a lesbian. gasp To a certain extent, Doctor’s structure strangely enough replicates a heteronormative family unit, as at one point, it seems possible that Ismail will marry Celia, and that Fatima has become a kind of surrogate daughter (a kind of imperfect replacement for Zubi). Though the novel takes too long to set up the connection between Celia and Ismail—indeed, Doctor is a talented writer and it’s perfectly clear that both characters are traumatized, so we could have used some editing in the first 100 pages—the sociopolitical import of the novel is obvious, and the novel especially provides the kind of ending not usually fit for so many characters who exist on society’s fringes. Somehow, Doctor manages to provide us with a convincing ending where outcasts and pariahs do not necessarily succumb to violent deaths and premature termination from the plotting.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Six-Metres-Pavement-Farzana-Doctor/dp/1554887674/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408805340&sr=8-1&keywords=six+metres+of+pavement

A Review of Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp (University of Utah Press, 2014).

What an absolutely amazing book! There can be no other estimation for such an important document that is part of the long-standing recovery effort related to the Japanese American internment experience. Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp is a mixed-genre, creative nonfiction memoir that employs photographs, narrative, and watercolor paintings to represent and to give life to Havey’s experiences as a ten-year old who first must endure living at an assembly center and then in the harsh conditions of Colorado’s Amache internment camp. The narrative is straightforward enough and one that recalls other internment works (such as Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile, Mitsuye Yamada’s Desert Run, etc) in its depiction of the monotony, the psychic struggles, and the everyday desultory life of languishing in what is basically an inhospitable place. There are moments of pleasure and even happiness, which erupt in Havey’s narrative in unexpected places: the light of the sun when it hits a cold and barren landscape or the return of a father from long periods away (working outside of the internment camp in order to escape its confines and to provide for the family). In other moments, we constantly see how the internees make the most of meager circumstances, continuing to persevere despite their imprisonment. Again, it is the minor moments which surface as a brutal and stark reminder of indomitable spirits, such as the desire of Havey’s mother to continue polishing the pot-bellied stove, or the move to decorate the ramshackle interiors of the interment barracks. But, what makes Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp so dynamic and so indispensable is its visual catalog, one that includes photographs (indeed, as Havey notes, in the last year of the internment camp, a camera was able to be used by residents) and watercolor paintings that Havey created over time to represent her experiences. The watercolor paintings are notable in that they are far from directly representational: most have abstract and symbolic qualities that seem exactly appropriate as a kind of formal conceit that illuminates such a fragmenting and harrowing experience.

Here’s a link to one of the watercolor paintings:

http://artistsofutah.org/15Bytes/index.php/lily-havey-reads-gasa-gasa-girl-goes-to-camp/

Havey often uses pastels (an effect to a certain extent of the watercolor approach), which ends up also functioning within a light scheme that comes off as ghostly. As these watercolors accompany the direct narrative of the internment, a multifaceted portrayal emerges that reminds us of the continued work that needs to be done in order to reconsider how this experience impacted so many Americans (Japanese in ethnicity and otherwise). Finally, I would like to remark on the production quality of this book: the pages used are the kinds found in art and painting studies, with a glossy finish. Certain to stand the test of time, one must pick up this essential and new addition to the canon of internment literatures.

Internment literatures based upon place:

Topaz: Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile; Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine

Minidoka: Mitsuye Yamada’s Camp Notes and Other Writings

Manzanar: Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s Farewell to Manzanar

Heart Mountain: Lee Ann Roripaugh’s Beyond Heart Mountain

Poston: Cynthia Kadohata’s Weedflower

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Gasa-Girl-Goes-Camp-Behind/dp/1607813432/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1410191557&sr=8-2&keywords=gasa+gasa+girl

A Review of Ed Lin’s Ghost Month (Soho Crime, 2014).

So when I picked up Ed Lin’s Ghost Month, I automatically assumed it was another book in Lin’s Robert Chow’s detective series (which includes This is a Bust, One Red Bastard, and Snakes Can’t Run). Instead, we have another book entirely, which revolves around Jing-nan (aka Johnny), a twenty-ish character languishing in a life he never wanted (inheriting the debts of his father and running a stall out of Taipei’s famed Night Market) living in a country he doesn’t want (Taiwan). The opening of the novel begins inauspiciously enough with Jing-nan discovering that the love of his life Julia Huang has been murdered. Jing-nan hadn’t kept in touch with Julia because of a promise he made that he would only marry her if he had established himself in a career and with full preparedness for life as a married couple. When he must leave UCLA without finishing his degree and returns to Taiwan, but not soon after, his mother dies in a tragic accident and his father dies just three weeks later due to health issues. Needless to say, Jing-nan’s life is turned upside down. He takes on the family business, while realizing that must pay back the debt his father had accrued over time. Thus, his romance with Julia is effectively dead, and he never hears about Julia until the news that a betel-nut stand worker has been found killed. This betel-nut stand worker is none other than Julia Huang. For about one hundred pages of the novel, Lin employs Jing-nan as the perfect narrator to welcome a reader with little understanding of Taipei. Jing-nan carefully and meticulously lays out the density of the city, its cultural particularities, and more importantly, its underground and unofficial economies. Toward the ending of this longer than usual preamble to the noir-plotting, he visits Julia’s family as a mode of honoring her memory. They beseech Jing-nan to find out more about the mysterious circumstances of Julia’s death and though reluctant, Jing-nan agrees. On the way out of the house, he is accosted by a stranger who warns him not to investigate. Later on, this stranger reappears and makes the same warning and punctuates his threat with ominous promises of physical harm and death. Thus begins the noir-plot that readers might have been waiting for, but Lin is really balancing more than one narrative here. On one level, the novel is really a character study of Jing-nan, who simultaneously comes to tell us about the complicated historical and social texture of Taiwan, which includes tensions with aboriginal tribes, the continuing standoff with mainland China, as well as the national drive to modernize and to displace older forms of commerce and culture. On the other, Lin introduces the noir plot as a way to get at some of these social issues and to some extent, then, this mystery doesn’t function as seamlessly as other texts that stick more closely to formula structures. My assessment is no means a critique of Lin’s work, which is multifaceted and benefits from the trademark humor that we’ve come to expect in his writings, but rather to elucidate the varied workings of this novel. Though Jing-nan’s fidelity to solving Julia Huang’s murder can stretch the bounds of credulity, the novel succeeds primarily due to Lin’s construction of a flawed but intriguing noir anti-hero, and we can see this novel as the start of another series.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Ghost-Month-Ed-Lin/dp/1616953268/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1410801485&sr=8-1&keywords=ed+lin+ghost+month

A Review of Michael Cho’s Shoplifting (Pantheon, 2014).

In Shoplifting, Asian Canadian graphic novelist Michael Cho brings us a poignant, nuanced narrative of a young woman trying to figure out her path in life. Our protagonist is Corinna Park, who may or may not be Asian American (an issue I’ll come back to later). She works for an advertisement agency in New York City, but finds her job less than fulfilling. The narrative starts on a day when she’s in a boardroom meeting coming up with an advertising campaign for a perfume that will be marketed to 9 year old girls. She makes an off-color remark that gestures to the sense of ennui that she feels working in a company that is far from her passion. As an undergraduate, Corinna majored in English and thought that she’d one day write novels. Instead, she feels lonely, socially anxious, and generally finds her job desultory. This graphic novel is a coming-of-age that begins when Corinna is brought in by the head of the company and told to rethink why she is at the advertising agency. The title refers to an illicit habit that Corinna maintains whenever she is at the local grocery store. She manages to shoplift a magazine by inserting it in between the pages of a newspaper. She doesn’t provide a reason for why she does it; indeed, she doesn’t lack the money to buy the newspaper but it gives her a kind of thrill. The shoplifting is of course a larger metaphor for the fact that Corinna needs a jumpstart, some sort of obvious sign to move into a new occupation or life trajectory. Fortunately, the graphic novel provides a conflation of different events that lead Corinna to make a monumental decision. Cho’s art has a nice cartoon-style to it. The production design team also saw fit to use a four-toned color scheme system, where pink is mixed in with grays, blacks, and whites.

The use of pink to structure the color is an interesting one and gives the graphic narrative a kind of lighter feel to it than the content of the story would probably allow for on its own. Cho is particularly effective at rendering the alienation that can come with living in a metropolis: Corinna is often framed in scenes with a ton of other individuals, whether commuting by subway or at some sort of gathering. A particular favorite detail of mine was Cho’s focus on internet dating, a quagmire of hilariously bad profiles that Corinna must sift through when she gets home. But, perhaps, the most intriguing element is Cho’s choice to veil Corinna’s ethnic background. With a Korean surname, it would seem very possible that she’s Asian American, but there’s nothing contextually provided that would determine this with any sort of certitude. It brings to mind the question of how race gets represented in the visual register and how graphic novels present more avenues for cultural critics to attend to the complexities of racial formation. A wonderful work, the first I hope of many more by Cho. Certainly, a book I will adopt for future classroom courses on the graphic novel.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Shoplifter-Michael-Cho/dp/030791173X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1409183592&sr=8-1&keywords=michael+cho

Published on September 20, 2014 17:43

September 16, 2014

Asian American Literature Fans - Megareview for September 16 2014 Amazon Imprints

Asian American Literature Fans - Megareview for September 16 2014 Amazon Imprints

A Review of Kirstin Chen’s Soy Sauce for Beginners (New Harvest, 2014).

I’ve slowly been working through Amazon’s publishing list, which brings me to Kirstin Chen’s Soy Sauce for Beginners, which is definitely on the lighter side of Asian American literature. It will be sure to fulfill the needs and desires of those who are especially interested in romance and courtship plots. In this case, we have a transnational Singaporean culinary twist as our protagonist, Gretchen Lin, travels back to her homeland in order to take a temporary job working in the family company. Her father and her uncle both run a soy sauce business that has been operating for almost three generations, but Gretchen’s arrival is not necessarily a felicitous time for everyone. Gretchen’s marriage is over, while her mother is suffering from health complications that require her to be on daily dialysis. Not helping matters is the fact that her mother continues to drink heavily. The soy sauce business is also in a state of transition. Gretchen’s cousin Cal has just been fired, after he attempted to shift the focus of the company to cheaper, mass-produced, trendier products, a move that ultimately backfired when it was discovered that these items were tainted and caused food poisoning. Thus, Gretchen’s father and uncle want to push the company back in the direction of its artisanal roots. Gretchen also happens to be working for the company at the same time as her best college friend, Frankie; she managed to get Frankie a business consulting position. With her best friend in tow—two single ladies as it were—we know that there are romance troubles certain to appear on the horizon. So the stage is set: will Gretchen (and Frankie) find love in Singapore? Will the business get back on track? Will Gretchen’s mother get sober? These are the issues at play in the novel. For those in Asian American Studies, what will be of further interest is the question of class privilege and modernization, especially in postcolonial context. Here, Gretchen never has to worry about where her next meal is coming from. Indeed, she is the daughter of a successful business magnate. In some sense, when she returns to Singapore, without a husband or a child and with no clear career path (she’s gotten an MA in musical education, but does not know she is going to do with this degree), she still has a tremendous safety net. The issue here is whether or not such a story ultimately provides a useful apparatus to explore the problems and tensions that have traditionally energized the field: elements such as social inequality and racial formation. Despite its more airy plotline, Chen obviously shows a gift for the construction of a lively protagonist, one which you can’t help root for, even if it already seems a given that she’ll find her way somehow. And the conclusion is, I think, one that moves beyond mere romance sentiment and moves this debut outside of some of the more stereotypical endings in which the protagonist’s success is so often levied on her successful pairing with a male partner (with money, good lucks, and a sense of humor to boot)! =)

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Soy-Sauce-Beginners-Kirstin-Chen/dp/0544114396/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&sr=&qid

A Review of Lori M. Lee’s Gates of Thread and Stone (Skyscape, 2014).

(does the cover have an Asian girl on it? does it matter? who knows?!)

Lori M. Lee’s debut novel Gates of Thread and Stone comes out of an amazon.com publishing imprint called Skyscape, which is focused on young adult cultural productions. Though I was wary about reviewing titles from this imprint, it’s quite clear that amazon is very serious about this venture, especially because the production value and editing in these works are of top-notch, big five publishing variety. With the recent spat between Hatchette Books and Amazon going on, let’s hope that there is a way for big and small presses to continue to thrive, to make some sort of reasonable profit, and for innovative work to continue to be produced. Lee’s debut is part of an intended series that will involve its first person protagonist, Kai, who is a teenager with the ability to bend time. Yes, she can manipulate time in such a way as to slow things down and then defend herself better in fights and escape dangerous situations. Kai lives in a city called Ninurta, a kind of throwback to the Medieval era and certainly inspired by fantasy fiction. Ninurta is segregated according to class. Those of the highest backgrounds eventually get to settle in the White Court, which is highly fortified and guarded by special humans who have their minds wiped and are called sentinels. When the novel opens, Kai subsists as a messenger, trying to make extra credits in order to survive. Her surrogate brother Reev works at a local bar. When Reev disappears, Kai decides that she is going to find him and teams up with Avan, a man who runs a local store. There are rumors of a malevolent figure called the Black Rider, who is kidnapping individuals in the city for unknown reasons, but as Kai and Reev find out, they will have to travel beyond Ninurta’s borders, through the harsh Outlands, across a forest, and into the void, to find out whether or not the Black Rider is involved in Reev’s disappearance. These places beyond Ninurta’s fortified walls all harbor deadly gargoyles. With the help of a traveling device called a gray, Avan and Kai are just able to make it to the Void and come upon a settlement in the desert in which the Black Rider can be found, but the Black Rider ends up being someone else entirely and shifts the novel into a new register in which myth, deities, and super-beings come to be unveiled. Lee takes some time to world build in this novel and fortunately, it’s so complex that readers have a lot to digest. At the same time, Lee sticks to the tried and true formula that fans of the genre will recognize: the not-so-normal heroine, who discovers that she possesses some unique power or ancestry, that will eventually get her into trouble and also move her into the path of a romantic foil. The late stage shift and plot reveals are a dicey gamble and it remains to be seen whether or not Lee can sustain the level of intrigue in the second book, especially given the fact that so much of the first novel was predicated on how little readers and Kai understood the social structure and power dynamics that undergird Ninurta. A solid debut!

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Gates-Thread-Stone/dp/1477847200/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1407962511&sr=8-1&keywords=gates+of+thread+and+stone

A Review of Andrew Xia Fukuda’s Crossing (Skyscape, 2010).

Billed as a young adult novel, Andrew Xia Fukuda’s debut Crossing was one of the first books to come out of amazon.com as a publishing house. The editing and production values of the book are of the highest quality, as evidenced by this engrossing narrative, one that will certainly cause readers to either “love” or “hate” the climactic conclusion. The novel is told from the first person perspective of a high school student named Xing, who grows up in Ashland, New York, a semi-rural town. He is one of two students of Asian descent in the entire high school, the other being Naomi Lee, his very close friend. Perhaps, we’re not too surprised to discover that Xing experiences bullying from some of his classmates; he’s an outsider and knows it, but the novel also throws in another interesting element into the equation when students start disappearing. Their bodies are typically found later in frozen lakes or in bits and pieces, and it’s apparent there is a serial killer on the loose. While these events wreak havoc on the high school, Xing has other complications to deal with, including a less-than-stellar home life and the possibility that he is going to sing in a school musical production. Fortunately or unfortunately, there are other social outcasts at Slackenville High, including a new student named Jan Blair, who boasts the very same name of the antagonist from The Blair Witch Project. When Jan is introduced, students start name-calling right away (in this sense, the high school-ers seem far more petulant than I ever remembered from personal experience, but hey, I guess I dodged a bullet) and it does not help that Jan is unkempt, pale, with stringy hair and a funky fashion style. Jan has been relegated to the netherworld of high school, a place that Xing knows all too well. You can expect that Jan and Xing are thus on a collision course in the novel, with Jan hoping for a romantic affiliation with Xing, but Xing begins to develop romantic feelings for Naomi. These various entanglements come to a head by the novel’s conclusion, and Fukuda has an obvious sense of where the novel must go. Though the novel can come off as heavy-handed, Fukuda’s success is in revealing how a social monster might be created rather than just birthed. A definitely engrossing debut novel for Fukuda; let’s hope he returns to exploring these ethnic and racial themes in his follow-up To The Hunt trilogy.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Crossing-Andrew-Xia-Fukuda/dp/1935597035/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408518658&sr=8-1&keywords=andrew+xia+fukuda

A Review of Susan Ee’s Angelfall (Skyscape, 2012); World After (Skyscape, 2013).

It’s the apocalypse in a way you might have not expected in Susan Ee’s debut, Angelfall, which turns conceptions of angels on their heads. In this novel, our protagonist and storyteller is Penryn Young, the requisite teenager that appears in these paranormal young adult fictions. She has one younger sister, Paige, (about seven years old) who suffered an accident as an infant and is now wheelchair bound. She has been raised under the spotty care of her schizophrenic mother. When angels descend on earth to wreak havoc upon the human populace across the globe, anarchy rains. People have abandoned their homes and are looking to go to less populated places. Penryn and her family hail from Silicon Valley, so their best choice is to head into the local hills. Things go south quite quickly when Penryn and her family end up interrupting a fight among angels. For whatever reason, Penryn assists the one angel who seems to be getting sacrificed; indeed, his wings are cut off, but in the process of drawing attention to herself, another angel takes off with Paige, flying away. Though Penryn has a dislike of all angels, she decides she must help nurse the wounded angel back to health if she is to have any chance to find her sister. The angel is named Raffe, and soon, they are traveling northward, with Penryn having convinced Raffe to take her to a place called the aerie, which may have some answers about Paige’s whereabouts. Raffe’s goal is of course to get his wings surgically reattached, and he is convinced that someone may be able to help him at the aerie. Of course, traveling in a post-apocalyptic world is no bowl of cherries and Penryn and Raffe have to deal with cannibals, roving bands of thieves and gangsters, and militia type men intent on resisting the angels. For the first half of the novel, Penryn and Raffe’s connection is obviously tenuous, with each showing an apparent dislike of each other, but as things go on, they follow the credo of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” and this approach allows them a fragile alliance that helps them to survive various obstacles. As the novel approaches its climax, the dynamic duo reaches the aerie, a place where angels and humans are congregating in San Francisco. Once there, it becomes clear the angels are set up in factions and that there is dissension among the ranks. It is also possible that Paige might be in one of these rooms, being held against her will. The conclusion is a thrilling, action-packed sequence that nicely sets up a sequel: is Paige alive? Will Raffe get his wings surgically reattached? And whatever happen to Penryn’s schizophrenic mother who disappears not long after Raffe and Penryn decide to travel northward together? All such questions can be answered when you read this book! As with other books in the paranormal young adult fiction genre, the question of race seems to be completely avoided. Most of this novel is set in Northern California, certainly a very diverse place, but there is—from what I can recall—never a mention of any racial or ethnic difference at any point in this text. Is Penryn white? Does it matter? These are questions I’ve been thinking about a lot, especially as Asian American writers have increasingly delved into popular genres in which race apparently doesn’t have to factor at all. Beyond these issues that I always think about, the novel is superbly entertaining with all of the requisite things you’d want in this genre, including the plucky, indefatigable heroine who somehow gets herself involved in some sort of supernatural storyline in which a guy, who may or may not be a possible romantic partner, plays a major part.

Apparently, according to GoodReads, the Penryn and the End of Days series is going to be at least five novels, which is sort of strange given the penchant for trilogies dominating the young adult market right now, but it gives us of course a lot to look forward to. In World After, the second installment, we see Penryn being separated from Raffe after the explosive events of the last novel. Penryn is also finally reunited with Paige, but—and there are spoilers forthcoming, so I would stop reading now if you don’t want to be spoiled—Paige is a little bit different at this point, having been subjected to some sort of experimentation that has altered her bite and her taste in food. Penryn also managed to get back in touch with her mother, so there is a sort of familial reunion. Not surprisingly and given the continued tensions occurring in the angelic realm, we know that this reunion will not last for long. Added into the mix is a woman named Clara, who Penryn had inadvertently saved in the last novel. Clara has prematurely aged, as her life force was being slowly sucked out of her by creatures who seem to be experiments gone terribly wrong: monstrosities with stinger tales and grasshopper like bodies who function to do the dirty work of fallen angels. These scorpion-like creatures can also fly, and the events from the conclusion of the last novel show us that they can be unleashed upon the world. When Penryn and her group of survivors are attacked by a band of these creatures, she is separated from Paige. Thus, Penryn, her mother, and Clara travel to Alcatraz in the hopes of finding her. By this point, the novel’s storyline concerning Paige grows a little thin, and readers might be wondering about Raffe and when he may or may not be reunited with Penryn. The repartee between Penryn and Raffe was certainly one of the highlights of the first book and the second takes too long for these figures to find their way back to each other. Surely, Ee does tantalize the possibility of their connection. For instance, Penryn is now owner to the sword that was once most faithful to Raffe, and Penryn is subjected to visions that allow her to understand that Raffe’s distant behavior was in fact a kind of cover to his true feelings. Ee does provide some intriguing future prospects for the series, especially given the genetic manipulation of species, something that moves this book more firmly into the area of biotechnology and issues related to assisted reproductive technologies. Here, it seems as though one of the rogue angels has a plan to reintroduce Armageddon on earth, and it definitely involves creating the perfect genetically modified specimens. It would seem that if we’re reading any political allegory into the novel, it appears with respect to this issue of genetics and who gets to play god when it comes to the future of Earth. Though it takes quite awhile before Raffe makes a substantive appearance in book 2, fans should be pleased that he’s still around and that there still seems to be an inkling of potential romance between the two characters, even if the relationship is supposedly forbidden. Indeed, Raffe has told Penryn that angels who fell in love with “daughters of Men” created offspring that were essentially demons. The conclusion to World After sees an interesting new shift in relation to power and destruction and we’ll look forward to seeing how the series continues to unfold.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Angelfall-Penryn-End-Days-Book/dp/0761463275/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408746317&sr=8-1&keywords=angelfall

http://www.amazon.com/World-After-Penryn-Days-Book/dp/147781728X/ref=tmm_pap_title_0

A Review of Kirstin Chen’s Soy Sauce for Beginners (New Harvest, 2014).

I’ve slowly been working through Amazon’s publishing list, which brings me to Kirstin Chen’s Soy Sauce for Beginners, which is definitely on the lighter side of Asian American literature. It will be sure to fulfill the needs and desires of those who are especially interested in romance and courtship plots. In this case, we have a transnational Singaporean culinary twist as our protagonist, Gretchen Lin, travels back to her homeland in order to take a temporary job working in the family company. Her father and her uncle both run a soy sauce business that has been operating for almost three generations, but Gretchen’s arrival is not necessarily a felicitous time for everyone. Gretchen’s marriage is over, while her mother is suffering from health complications that require her to be on daily dialysis. Not helping matters is the fact that her mother continues to drink heavily. The soy sauce business is also in a state of transition. Gretchen’s cousin Cal has just been fired, after he attempted to shift the focus of the company to cheaper, mass-produced, trendier products, a move that ultimately backfired when it was discovered that these items were tainted and caused food poisoning. Thus, Gretchen’s father and uncle want to push the company back in the direction of its artisanal roots. Gretchen also happens to be working for the company at the same time as her best college friend, Frankie; she managed to get Frankie a business consulting position. With her best friend in tow—two single ladies as it were—we know that there are romance troubles certain to appear on the horizon. So the stage is set: will Gretchen (and Frankie) find love in Singapore? Will the business get back on track? Will Gretchen’s mother get sober? These are the issues at play in the novel. For those in Asian American Studies, what will be of further interest is the question of class privilege and modernization, especially in postcolonial context. Here, Gretchen never has to worry about where her next meal is coming from. Indeed, she is the daughter of a successful business magnate. In some sense, when she returns to Singapore, without a husband or a child and with no clear career path (she’s gotten an MA in musical education, but does not know she is going to do with this degree), she still has a tremendous safety net. The issue here is whether or not such a story ultimately provides a useful apparatus to explore the problems and tensions that have traditionally energized the field: elements such as social inequality and racial formation. Despite its more airy plotline, Chen obviously shows a gift for the construction of a lively protagonist, one which you can’t help root for, even if it already seems a given that she’ll find her way somehow. And the conclusion is, I think, one that moves beyond mere romance sentiment and moves this debut outside of some of the more stereotypical endings in which the protagonist’s success is so often levied on her successful pairing with a male partner (with money, good lucks, and a sense of humor to boot)! =)

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Soy-Sauce-Beginners-Kirstin-Chen/dp/0544114396/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&sr=&qid

A Review of Lori M. Lee’s Gates of Thread and Stone (Skyscape, 2014).

(does the cover have an Asian girl on it? does it matter? who knows?!)

Lori M. Lee’s debut novel Gates of Thread and Stone comes out of an amazon.com publishing imprint called Skyscape, which is focused on young adult cultural productions. Though I was wary about reviewing titles from this imprint, it’s quite clear that amazon is very serious about this venture, especially because the production value and editing in these works are of top-notch, big five publishing variety. With the recent spat between Hatchette Books and Amazon going on, let’s hope that there is a way for big and small presses to continue to thrive, to make some sort of reasonable profit, and for innovative work to continue to be produced. Lee’s debut is part of an intended series that will involve its first person protagonist, Kai, who is a teenager with the ability to bend time. Yes, she can manipulate time in such a way as to slow things down and then defend herself better in fights and escape dangerous situations. Kai lives in a city called Ninurta, a kind of throwback to the Medieval era and certainly inspired by fantasy fiction. Ninurta is segregated according to class. Those of the highest backgrounds eventually get to settle in the White Court, which is highly fortified and guarded by special humans who have their minds wiped and are called sentinels. When the novel opens, Kai subsists as a messenger, trying to make extra credits in order to survive. Her surrogate brother Reev works at a local bar. When Reev disappears, Kai decides that she is going to find him and teams up with Avan, a man who runs a local store. There are rumors of a malevolent figure called the Black Rider, who is kidnapping individuals in the city for unknown reasons, but as Kai and Reev find out, they will have to travel beyond Ninurta’s borders, through the harsh Outlands, across a forest, and into the void, to find out whether or not the Black Rider is involved in Reev’s disappearance. These places beyond Ninurta’s fortified walls all harbor deadly gargoyles. With the help of a traveling device called a gray, Avan and Kai are just able to make it to the Void and come upon a settlement in the desert in which the Black Rider can be found, but the Black Rider ends up being someone else entirely and shifts the novel into a new register in which myth, deities, and super-beings come to be unveiled. Lee takes some time to world build in this novel and fortunately, it’s so complex that readers have a lot to digest. At the same time, Lee sticks to the tried and true formula that fans of the genre will recognize: the not-so-normal heroine, who discovers that she possesses some unique power or ancestry, that will eventually get her into trouble and also move her into the path of a romantic foil. The late stage shift and plot reveals are a dicey gamble and it remains to be seen whether or not Lee can sustain the level of intrigue in the second book, especially given the fact that so much of the first novel was predicated on how little readers and Kai understood the social structure and power dynamics that undergird Ninurta. A solid debut!

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Gates-Thread-Stone/dp/1477847200/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1407962511&sr=8-1&keywords=gates+of+thread+and+stone

A Review of Andrew Xia Fukuda’s Crossing (Skyscape, 2010).

Billed as a young adult novel, Andrew Xia Fukuda’s debut Crossing was one of the first books to come out of amazon.com as a publishing house. The editing and production values of the book are of the highest quality, as evidenced by this engrossing narrative, one that will certainly cause readers to either “love” or “hate” the climactic conclusion. The novel is told from the first person perspective of a high school student named Xing, who grows up in Ashland, New York, a semi-rural town. He is one of two students of Asian descent in the entire high school, the other being Naomi Lee, his very close friend. Perhaps, we’re not too surprised to discover that Xing experiences bullying from some of his classmates; he’s an outsider and knows it, but the novel also throws in another interesting element into the equation when students start disappearing. Their bodies are typically found later in frozen lakes or in bits and pieces, and it’s apparent there is a serial killer on the loose. While these events wreak havoc on the high school, Xing has other complications to deal with, including a less-than-stellar home life and the possibility that he is going to sing in a school musical production. Fortunately or unfortunately, there are other social outcasts at Slackenville High, including a new student named Jan Blair, who boasts the very same name of the antagonist from The Blair Witch Project. When Jan is introduced, students start name-calling right away (in this sense, the high school-ers seem far more petulant than I ever remembered from personal experience, but hey, I guess I dodged a bullet) and it does not help that Jan is unkempt, pale, with stringy hair and a funky fashion style. Jan has been relegated to the netherworld of high school, a place that Xing knows all too well. You can expect that Jan and Xing are thus on a collision course in the novel, with Jan hoping for a romantic affiliation with Xing, but Xing begins to develop romantic feelings for Naomi. These various entanglements come to a head by the novel’s conclusion, and Fukuda has an obvious sense of where the novel must go. Though the novel can come off as heavy-handed, Fukuda’s success is in revealing how a social monster might be created rather than just birthed. A definitely engrossing debut novel for Fukuda; let’s hope he returns to exploring these ethnic and racial themes in his follow-up To The Hunt trilogy.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Crossing-Andrew-Xia-Fukuda/dp/1935597035/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408518658&sr=8-1&keywords=andrew+xia+fukuda

A Review of Susan Ee’s Angelfall (Skyscape, 2012); World After (Skyscape, 2013).

It’s the apocalypse in a way you might have not expected in Susan Ee’s debut, Angelfall, which turns conceptions of angels on their heads. In this novel, our protagonist and storyteller is Penryn Young, the requisite teenager that appears in these paranormal young adult fictions. She has one younger sister, Paige, (about seven years old) who suffered an accident as an infant and is now wheelchair bound. She has been raised under the spotty care of her schizophrenic mother. When angels descend on earth to wreak havoc upon the human populace across the globe, anarchy rains. People have abandoned their homes and are looking to go to less populated places. Penryn and her family hail from Silicon Valley, so their best choice is to head into the local hills. Things go south quite quickly when Penryn and her family end up interrupting a fight among angels. For whatever reason, Penryn assists the one angel who seems to be getting sacrificed; indeed, his wings are cut off, but in the process of drawing attention to herself, another angel takes off with Paige, flying away. Though Penryn has a dislike of all angels, she decides she must help nurse the wounded angel back to health if she is to have any chance to find her sister. The angel is named Raffe, and soon, they are traveling northward, with Penryn having convinced Raffe to take her to a place called the aerie, which may have some answers about Paige’s whereabouts. Raffe’s goal is of course to get his wings surgically reattached, and he is convinced that someone may be able to help him at the aerie. Of course, traveling in a post-apocalyptic world is no bowl of cherries and Penryn and Raffe have to deal with cannibals, roving bands of thieves and gangsters, and militia type men intent on resisting the angels. For the first half of the novel, Penryn and Raffe’s connection is obviously tenuous, with each showing an apparent dislike of each other, but as things go on, they follow the credo of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” and this approach allows them a fragile alliance that helps them to survive various obstacles. As the novel approaches its climax, the dynamic duo reaches the aerie, a place where angels and humans are congregating in San Francisco. Once there, it becomes clear the angels are set up in factions and that there is dissension among the ranks. It is also possible that Paige might be in one of these rooms, being held against her will. The conclusion is a thrilling, action-packed sequence that nicely sets up a sequel: is Paige alive? Will Raffe get his wings surgically reattached? And whatever happen to Penryn’s schizophrenic mother who disappears not long after Raffe and Penryn decide to travel northward together? All such questions can be answered when you read this book! As with other books in the paranormal young adult fiction genre, the question of race seems to be completely avoided. Most of this novel is set in Northern California, certainly a very diverse place, but there is—from what I can recall—never a mention of any racial or ethnic difference at any point in this text. Is Penryn white? Does it matter? These are questions I’ve been thinking about a lot, especially as Asian American writers have increasingly delved into popular genres in which race apparently doesn’t have to factor at all. Beyond these issues that I always think about, the novel is superbly entertaining with all of the requisite things you’d want in this genre, including the plucky, indefatigable heroine who somehow gets herself involved in some sort of supernatural storyline in which a guy, who may or may not be a possible romantic partner, plays a major part.

Apparently, according to GoodReads, the Penryn and the End of Days series is going to be at least five novels, which is sort of strange given the penchant for trilogies dominating the young adult market right now, but it gives us of course a lot to look forward to. In World After, the second installment, we see Penryn being separated from Raffe after the explosive events of the last novel. Penryn is also finally reunited with Paige, but—and there are spoilers forthcoming, so I would stop reading now if you don’t want to be spoiled—Paige is a little bit different at this point, having been subjected to some sort of experimentation that has altered her bite and her taste in food. Penryn also managed to get back in touch with her mother, so there is a sort of familial reunion. Not surprisingly and given the continued tensions occurring in the angelic realm, we know that this reunion will not last for long. Added into the mix is a woman named Clara, who Penryn had inadvertently saved in the last novel. Clara has prematurely aged, as her life force was being slowly sucked out of her by creatures who seem to be experiments gone terribly wrong: monstrosities with stinger tales and grasshopper like bodies who function to do the dirty work of fallen angels. These scorpion-like creatures can also fly, and the events from the conclusion of the last novel show us that they can be unleashed upon the world. When Penryn and her group of survivors are attacked by a band of these creatures, she is separated from Paige. Thus, Penryn, her mother, and Clara travel to Alcatraz in the hopes of finding her. By this point, the novel’s storyline concerning Paige grows a little thin, and readers might be wondering about Raffe and when he may or may not be reunited with Penryn. The repartee between Penryn and Raffe was certainly one of the highlights of the first book and the second takes too long for these figures to find their way back to each other. Surely, Ee does tantalize the possibility of their connection. For instance, Penryn is now owner to the sword that was once most faithful to Raffe, and Penryn is subjected to visions that allow her to understand that Raffe’s distant behavior was in fact a kind of cover to his true feelings. Ee does provide some intriguing future prospects for the series, especially given the genetic manipulation of species, something that moves this book more firmly into the area of biotechnology and issues related to assisted reproductive technologies. Here, it seems as though one of the rogue angels has a plan to reintroduce Armageddon on earth, and it definitely involves creating the perfect genetically modified specimens. It would seem that if we’re reading any political allegory into the novel, it appears with respect to this issue of genetics and who gets to play god when it comes to the future of Earth. Though it takes quite awhile before Raffe makes a substantive appearance in book 2, fans should be pleased that he’s still around and that there still seems to be an inkling of potential romance between the two characters, even if the relationship is supposedly forbidden. Indeed, Raffe has told Penryn that angels who fell in love with “daughters of Men” created offspring that were essentially demons. The conclusion to World After sees an interesting new shift in relation to power and destruction and we’ll look forward to seeing how the series continues to unfold.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Angelfall-Penryn-End-Days-Book/dp/0761463275/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408746317&sr=8-1&keywords=angelfall

http://www.amazon.com/World-After-Penryn-Days-Book/dp/147781728X/ref=tmm_pap_title_0

Published on September 16, 2014 14:07

September 12, 2014

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for September 12, 2014

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for September 12, 2014

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide ranging and expansive terrain of Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews of Steph Cha’s Beware Beware (Minotaur Books, 2014); Lan Cao’s The Lotus and the Storm (Viking Adult, 2014); Tania Malik’s Three Bargains (WW Norton, 2014); Tom Cho’s Look Who’s Morphing (Arsenal Pulp, 2014); A Cut-Like Wound (Bitter Lemon Press, 2014).

A Review of Steph Cha’s Beware Beware (Minotaur Books, 2014).

Again, I failed to hold off on reading a book that I was saving for a rainy day. This time it was Steph Cha’s Beware Beware, which is the follow-up to Follow Her Home. In Follow her Home (reviewed earlier here), Cha created a wonderful noir-ish heroine with Juniper Song, who falls into an unofficial investigation, which ends up getting increasingly complicated, so much so that the body count includes one of her closest friends. In Beware Beware, Song has gone more official; she’s an intern now working with an actual investigatory team, which includes her boss Chaz and another supervisor Arturo. Song is finally put on her own case, which involves her scoping out a woman’s boyfriend to see if he is cheating on her, and if he is into dealing drugs. The woman, Daphne Freamon, a semi-famous painter who is African American, simply wants more information about what her boyfriend, Jamie Landon, does with all of his time, especially when he seems to disappear for days. As Song discovers, Jamie doesn’t do much but hang out with an aging, but still well-known Hollywood movie star named Joe Tilley. But when Joe Tilley is discovered by Jamie with his wrists slashed after a night of hard partying and Song is the first person to come upon the crime scene after being alerted to the goings-on by Daphne, the novel shifts into high gear. Did Jamie kill Joe, perhaps in a drug-fueled haze? If not Jamie, who would have the motive? Could it be Joe’s son from an earlier marriage? Could it be an ex-wife? Song is up for the challenge to investigate and indeed is hired by Daphne to look into the possibility that Jamie may have been set up. Cha adds a very important subplot early on involving the daughter of one of the murderer’s from her debut. Indeed, Song has moved in with Lori, the young Korean American woman who Song had “followed” home in the first part of the series. Lori’s life has turned around and she even has a promising new Korean boyfriend named Isaac, but her connection with her uncle Taejin creates more complications. Indeed, after visiting him at his auto shop, she bumps into a Korean thug Winfred, and Taejin cautions her to treat this man very nicely. Of course, Winfred becomes more menacing. As Lori maintains a fragile line between flirtation and friendship, thing soon things escalate. As the central plot involving the murder resolves, both Song and her boss Chaz realize the improbability of the scenario that eventually plays out, but even as the mystery plot seems both complicated and hardly feasible (with so much premeditation that your head may be swimming), Cha’s handle on the core genre element of detection is top-notch. Indeed, you are effectively pulled into this labyrinthine narrative precisely because of the desire to know. The threads all do resolve in one way or another and the noir-ish ending shows us how murky the line between heroes and villains can be. Cha continues to draw upon the rich Los Angeles noir tradition. Last time I mentioned Walter Mosley and I couldn’t help but think about the femme fatale in that plot, Daphne Monet, who seems to have certain parallels to Daphne Freamon in Cha’s novel. I also really enjoyed Cha’s movement more firmly into the Hollywood film industry here, which allows Cha to delve into some different spaces than the last novel, which focused more Korean ethnic subcultures. Another winning installment in the Juniper Song series, and we’ll hope for many more.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Beware-Juniper-Song-Mystery-Mysteries/dp/1250049016/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408030966&sr=8-1&keywords=steph+cha

A Review of Lan Cao’s The Lotus and the Storm (Viking Adult, 2014).

Lan Cao leaves the first novelist’s club (the ones remaining that I keep wondering about are Brian Ascalon Roley and le thi diem thuy, both writers that I hope have something still cooking) with The Lotus and the Storm, a war epic in line with the work of Tan Twan Eng and Roma Tearne, especially with respect to its sweep, scope, and pathos. Given the ever-growing body of literature devoted to representations of the Vietnam War, Cao continues to delve into the psychic aftermath for those who still continue to suffer in the wake of a country’s long history with foreign rulers, invasions, and occupations. The story is primarily told between two alternating narrators: there is Mai, who in 1963, is just a young girl, who is growing up in the very long shadow of war and foreign occupation; and then there is Minh, Mai’s father, who is a colonel in the South Vietnamese army. The French have left the country with their tails behind them, while the Americans are rolling in and increasing their presence. The president, Diem Bien Phu, has just been overthrown by a military coup, which has not been supported by Minh. Minh is able to escape from the fallout of his dissension with the support of a close friend, Phong, but the realization that his country is moving in a direction that portends its eventual downfall leaves Minh with a bitter sense of what the future will bring. Their lives are completely thrown into disarray when Mai’s sister Khanh is killed by a stray bullet. Mai goes mute, while Minh and his wife Quy eventually grow apart. The situation in the country continues to deteriorate, while Cao puts to effective use the tense period of the Tet Offensive to show how badly things are going for the South Vietnamese and the American military. The story of Mai and Minh during the war appears to alternate to the present moment in which Minh lives in Virginia and is being taking care of by Mrs. An, a woman who has come to be a part of Minh’s extended family. Mrs. An and Minh are part of a hui, a rotating money club, which has come to some disagreement over the ways that funds are being used and handled. Mrs. An in particular is having trouble with her monthly payments, which becomes a source of contention between Minh and Mai, who is a grown adult, but still suffering from what might be called psychotic breaks linked backed to the war. Perhaps, the most effective and original element of Cao’s novel is a kind of surprise narrative move (something that reminded me of Truong’s Bitter in the Mouth) about halfway through the novel that discursively shows us exactly what kind of state Mai is still in as an adult and how there are still so many things that these narrators are not telling us. The withholding by these narrators does create some momentum issues, especially because it takes quite a bit of time before we start to see what is going on underneath these characters and how unstable the psychic landscape has been for them both. Cao’s novel is impressive in its panoramic descriptive force, but the novel will ultimately require patience, especially in the first 100 pages. There are numerous late-stage revelations that make the reading experience quite an emotional rollercoaster and by the time you make it to page 300, you’ll be reading the final hundred or so pages at a lightning speed, trying to figure out how the novel will resolve its many loose ends. To be sure, Cao doesn’t wrap everything up too neatly, but a surprise appearance in the final forty pages is an interesting and perhaps debatable choice, especially with how that particular plot plays out. As the narrative accrues its many textures, the eventual result is a novel with an outstanding representational intervention in the links between the individual and the social, trauma and its aftermath, Vietnam and America. A must-read for fans of American and Asian American literature, war epics, and those interested in representations of psychic instability!

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Lotus-Storm-A-Novel/dp/0670016926/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408118982&sr=8-1&keywords=the+lotus+and+the+storm

A Review of Tania Malik’s Three Bargains (WW Norton, 2014).