Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 52

August 15, 2014

Review: A Certain Exposure by Jolene Tan (Epigram Books, 2014)

Author: Jolene Tan

Publisher: Epigram Books

Publication Date: April 2014

[Before I proceed with this review, let me provide a categorical disclaimer: I’ve known Jolene for, wow, is it four years now? and have the highest respect for her work. Take this disclosure of potential prejudice for what you will. P.S.: I paid for my copy of the book, fair and square!]

Lawyer and activist Jolene Tan burst into the Singapore literary scene this year. Her first novel, A Certain Exposure follows twin brothers Brian and Andrew through the late 1980s and the 1990s, from their family apartment in a Singapore public housing estate to Andrew’s suicide in a Cambridge dorm room. The narrative jumps between their uneasy fraternity during the turbulence of high school, to Brian’s survivor’s guilt in the confines of lower-middle-class Chinese morality.

While she is a seasoned writer currently working in public relations, A Certain Exposure is Tan’s first major work of fiction, and this rawness is apparent in her prose, despite Jason Erik Lundberg’s editing.

Certain sentence formulations come across as clunky—her opening line, “Brian organised for the body to be flown back,” has become, among reviewers, a somewhat notorious example of this flaw. There is also a tendency, which I personally dislike, to over-explain the quintessentially Singaporean elements of the narrative, but Tan restrains this urge much better than many other Singaporean Anglophone writers. And although I was not too bothered by the frequent shifts between settings, the jumpy cuts between different points of view can be much more jarring, because each change comes with the need to introduce yet another bit player’s life story.

Nonetheless, these minor aesthetic weaknesses, in what is otherwise stolid prose, cannot detract from the importance of Tan’s contribution to Singaporean literature. A Certain Exposure is a measured attack on the dominant statal narratives that govern public life in Singapore, and Tan carefully takes apart critical national myths like racial harmony, meritocracy, and post-feminist gender equality.

Thematically, Tan’s novel re-treads the terrain of already-familiar criticism; but the book is ground-breaking in its refusal to pussyfoot around its subject matter. For example, unlike Lydia Kwa’s Pulse (first published in a limited print run in 2010 and re-released just last month), Tan does not wait till the novel’s final pages to implicate the criminality of gay identity as a reason for Andrew’s suicide. Nor does she, with coy delicacy, avoid the word rape—nor the implication of colourist misogyny—in the scene where a survivor of campus assault testifies to an unsympathetic school administrator.

Interestingly, the editor at Singapore’s leading literary magazine QLRS absolutely hated A Certain Exposure. Toh Hsien Min wrote in his review:

How many issues can a writer cram into one novel? Let's do a count: there's the racism issue, the elitism issue, the capitalism issue, the Christian issue, the teenage intimacy issue, the rape issue, the bullying issue, the misogynist issue and, for good measure, both the gay and lesbian issues. […] Overall, this makes the novel feel like an attempt to assert left-wing liberal credentials for the sake of being left-wing and liberal, not because of having anything urgent or original to say. “Sometimes people are their own worst enemies”, says one of the civil servants in an especially bad set piece. Indeed: this has gone beyond preaching to the converted to the point of preaching to inadvertently unconvert the converted — it made this Guardian reader feel a little queasy, only stopping from reaching for a copy of the Times of London by wondering if the novel is quintessentially Singaporean because of that Singaporean inability to get the chip off the shoulder.

Was it hard, lifting a hatchet that heavy to the novel? Tan’s novel is a killer debut, one that resounds urgently for the very reason, I suspect, that Toh despises it: the racism “issue,” the rape “issue,” the misogyny “issue,” the homophobia “issue” are all symptoms of deep-set and deeply denied systems of inequality in contemporary Singapore.

Fresh out of high school myself, I can attest to the fact that the events that Toh finds heavy-handed go on with as much unrelenting regularity in real life as in the novel. Tan herself, who attended Singapore’s top-tier Raffles schools before going on to Cambridge and Harvard, told The Straits Times’ Akshita Nanda: “There was a boy in school, everybody knew the rugby players had taken him into a toilet and pissed on him. Or this girl who everybody knew had had sex on a pool table, but it never occurred to me to think about what went on behind that knowledge.” Campus rape is no less a problem in Singaporean high schools than in USAmerican ones, and it is A Certain Exposure’s honesty that makes it difficult to read and difficult to put down.

Tan’s authorial decision to situate A Certain Exposure two decades in the past—during the very era of economic transformation—is a considered choice that forces the reader to interrogate how much Singapore has progressed in its journey “from Third World to First.” It loses nothing of its impact by its distance, even if the omniscient narrator’s occasional flash-forward asides feel forced.

All in all, A Certain Exposure is a powerful work of social realism—ask any queer, minority and/or woman between 18 and 25 who grew up here, and they’ll say how real it is—and a welcome addition to our still-limited Anglophone-novel canon.

Once you’re done with A Certain Exposure, pick up Balli Kaur Jaswal’s 2013 novel Inheritance, which examines the psychological and cultural sacrifices made by a middle-class Punjabi Sikh household in the industrialising Singapore of the 1970s through 1990s.

Buy the book online at: Epigram Books | Select Books | Books KinokuniyaAugust 14, 2014

Almost 1000 books reviewed!

August 11, 2014

Jean Kwok's Mambo in Chinatown

The novel sketches out an insular world for Charlie, one confined almost exclusively to Chinatown where she works as a dishwasher in the same restaurant where her father makes hand-drawn noodles. Kwok works through a number of common themes regarding cultural conflict and generational differences. At the heart of the novel is Charlie's move to a new job as a receptionist at a ballroom dance studio, something she keeps a secret from her father (she tells him she is working as a receptionist at a computer company instead). Although Charlie's mother was a professional dancer in China, Charlie does not believe that her father would allow her to work in a dance studio because he would think it is too Western and too dangerous for a Chinese girl.

As you might expect, Charlie goes on to find herself over the course of the novel, coming into her own self and her own body through the vehicle of dance. Along the way, she learns to carry herself more confidently but also to dress more revealingly and to wear makeup as befits her age. On top of all that, she falls in love with a white male dancing student, Ryan.

As much as the novel carves out binaries between East and West, it also sees confluences and similarities in some places. Charlie's experience with tai chi, for instance, allows her to understand ballroom dance more quickly than otherwise. Ryan's understanding of feng shui and the idea of spiritual balance is partially what endears him to Charlie since she sees that he is, in some ways, also a bit Chinese.

The other major narrative strand in the novel centers on Lisa, who has always been the smart one in the family. Although she has a chance to test for entrance into Hunter High School, a prestigious public school in the city, she also comes down with a mysterious, debilitating condition where she loses strength in her legs. Her father tries all sorts of Chinese medicine (his brother has a traditional medicine practice in Chinatown) and even witchcraft (they consult the Vision, an older woman who performs rituals and spouts prophecies). The novel pits these Chinese medical arts and spiritual beliefs against Western medicine throughout.

The audiobook version made me cringe a little with the performer/narrator Angela Lin's use of accented English for the older generation of Chinese immigrants, even when those characters were supposed to be speaking Chinese. I understand that there is a need to differentiate the dialogue of different characters, and as Arthur Chu recently put it (I came across his blog post while I was listening to Kwok's novel, in fact), the immigrant generation does speak often in heavily accented English. I do wonder how performers of audiobooks might aurally signal dialogue spoken in a foreign language (but written in English) without recourse to accented English...

As I listened to this novel, I also kept thinking that there was another second novel by an Asian American author, published sometime in the earlier 2000s, also set in New York City in the subcultural world of dancers, but I couldn't remember the author, title, or other details of the story. After searching through our librarything list of reviews, I was able to figure out that the book I was thinking of is Patricia Chao's Mambo Peligroso. These two novels might make an interesting pair to read together, particularly to consider how each negotiates interracial contact as well as the physicality/spirituality of dance.

August 10, 2014

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for August 10, 2014

A Review of Monica Chiu’s Scrutinized! Surveillance in Asian North American Literature (University of Hawaii Press, 2014).

(unfortunately the highest rec pic I could find!)

It’s an absolutely wonderful time to be an Asian American cultural critic. The archive continues to grow at an exponential pace, as evidenced by Monica Chiu’s Scrutinized! Surveillance in Asian North American Literature, which focuses on books that have been published, for the most part, within the last decade. Her monograph follows in line with other studies such as Tina Chen’s Double Agency and Betsy Huang’s Contesting Genres in Contemporary Asian American Fiction in its exploration and investigation of Asian Americans, detection, spy tropes, anxiety and paranoia, especially in the post-9/11 moment. Perhaps, the most succinct crystallization of the project occurs on page 4, when Chiu writes: “While overtly racist acts such as exhibiting Asian subjects are confined to the past, Scrutinized! argues that current Asian North American novel’s fascination with mystery, detection, spying, tracking, and surveillance is a literary response to contemporary social agitation surrounding race…. Scrutiny of raced subjects privileges a dominant gaze that makes legible a kind of Asian North American subjectivity. Scrutinized! suggests that a history of surveillance has created Asian North American subjects (authors and their characters) who watch themselves being watched. Their categorization as inscrutable ironically reveals a national obsession over their visibility and fear about their perceived illegibility” (4). The primary textual works engaged in this study include: Don lee’s Country of Origin (chapter 2); Nina Revoyr’s Southland (chapter 3); Susan Choi’s Person of Interest (chapter 4); Suki Kim’s Interpreter (chapter 4); Kerri Sakamoto’s The Electrical Field (chapter 5); and Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist (chapter 6). Chiu picks an absolutely dynamic set of books, all of which I would consider to be ones that have the unique combination of aesthetic complexity, political texture, and entertainment value. Of these books, I have taught Southland, Interpreter, and The Reluctant Fundamentalist and they make for great classroom discussions. Chiu has had similar experiences; the openings of her chapters often invoke issues raised up when she has taught these books. Most impressive about this monograph is Chiu’s painstaking research. For instance, chapter 2 focuses on Orientalized spaces and pushed Chiu to contextualize her reading of Lee’s novel through the study of sexual subcultures, Asian and Asian North American ghettos, and the hospitality industry. In chapter 5 and in what I consider to be one of the most unique methodological approaches to criticism, Chiu’s analysis of Sakamoto’s novel is influenced by her study of Japanese Canadian internment photography, a visual archive that unveils and encrypts that kinds of traumas sustained by those who were incarcerated. Chiu’s work is also impressive in its mobilization of various hermeneutics and disciplinary models, including but not limited to psychoanalysis, trauma theory, and narratology. Certainly, a study that contributes to the ever-complicated contours of Asian North American racial formation and a book that could certainly be used as a companion in a course devoted to Asian North American detective fiction, which now boasts a rather impressive set of texts. Indeed, Chiu only has so much time to make her case, but it’s clear that her study could have been far longer, as she mentions the many other Asian North American writers who have worked in this genre (such as Dale Furutani, Naomi Hirahara, and I would add some newer writers like Steph Cha and A.X. Ahmad). As I have mentioned with other monographs coming of the University of Hawaii Press, let us hope this titles move into paperback!

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Scrutinized-Surveillance-American-Literature-Intersections/dp/0824838424/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1402715670&sr=8-1&keywords=Scrutinized%21

A Review of Crystal S. Anderson’s Beyond The Chinese Connection: Contemporary Afro-Asian Cultural Production (University Press of Mississippi, 2013)

Crystal S. Anderson’s brilliant monograph, Beyond The Chinese Connection: Contemporary Afro-Asian Cultural Production (University Press of Mississippi, 2013), is on the forefront of the growing trend devoted to comparative race studies and seeks to show the asymmetrical but interconnected ways that racial and ethnic representation appears in popular culture, print, film, and other such media. The book is rigorous and expansive in its scope and sweep. Individual chapters focus on critically acclaimed novels including Gunga Din Highway (Frank Chin) and Japanese by Spring (Ishmael Reed) as well as influential films (e.g. The Matrix trilogy). Beyond the Chinese Connection challenges traditional conceptions of race and ethnic studies, transnationalism, and sociopolitical rhetoric in its evocation of Afro-Asian connections. Taking Bruce Lee and his filmic oeuvre as a starting point, Anderson shows the textured interactions and interrelationships between African American and Asian/ American cultures and communities over half a century. Interrogating boundaries of ossifying disciplines and subfields, Anderson’s thesis superbly and precisely conveys how we must understand American cultural production through its hybrid influences and cross-cultural exchanges. Her monograph marks a more nuanced approach to American Studies and cultural studies that is both broadly impactful and socially conscious. Not surprisingly, her book received unqualified endorsements from two of the leading scholars in American Studies, the very senior professors Gary Y. Okihiro and Bill V. Mullen. At the core of Anderson’s argument is a continuum based upon two terms used through the book: cultural emulsion and cultural translation. Anderson shows that in some cases representations of Afro-Asian connections ultimately operate to distinguish racial and ethnic groups rather then presenting them as some sort of harmonious mixture, a separating effect called cultural emulsion (5). Other representations function with a kind of cross-cultural dialogue in which one culture or group is informed by or influenced productively by another, something that turns into cultural translation (5). Cultural productions fall somewhere along this continuum. Anderson reads three main thematics as the basis of her chapters: interethnic male friendships (chapter 2), ethnic imperialism (chapter 3), and interethnic conflict and solidarity (chapter 4), as the structural grounds upon which all of her analyses are made. Anderson thus convincingly shows how Bruce Lee and his films became one pivotal launching point for the next fifty years in Afro-Asian cultural representations. On a personal note, I found this monograph fun to read just on the basis of its panoramic sweep of literature and film; many of these cultural productions are more popularly embraced by a larger audience and will be sure to interest an accordingly wider readership.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Beyond-The-Chinese-Connection-Contemporary/dp/1617037559/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1403713104&sr=8-1&keywords=Crystal+S.+Anderson+Beyond

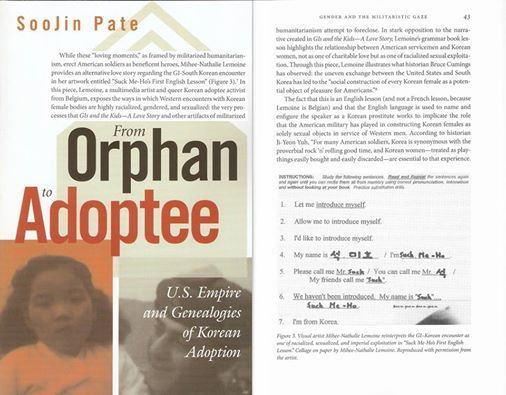

A Review of SooJin Pate’s From Orphan to Adoptee: U.S. Empire and Genealogies of Korean Adoption (University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

SooJin Pate’s From Orphan to Adoptee: U.S. Empire and Genealogies of Korean Adoption is an astute and wide-ranging study. It intervenes in the work of orphan/ adoptee studies by focusing on a transnational process by which bodies shift in their meaning and signification, especially in the context of war and global capital. Prior studies in relation to orphans and adoptees have typically focused on the domestic U.S. context; Pate’s work provides the bridge between what she calls militarized humanism and the construction of the social orphan, who is ultimately a figure imbued with social death. Particularly important to Pate’s overall argument is the distinction between orphan and adoptee, two terms that get elided. The production of the term Korean orphan is most salient within the U.S.-Korean conflict context, a figure who emerges through America’s empirical designs. The Korean orphan is not necessarily or actually an orphan as Pate explains, precisely because so many children were separated from parents and were routed into orphanages only because they could not or were not reunited with family members. The orphan eventually evolves into an adoptee by the process of a kind of American pacification process: the orphan must be checked for health, must be presented in the proper way to Americans, and must ultimately be a kind of tabula rasa that can be rescripted as the assimilable American citizen. Only then can the orphan become an adoptee. Once an adoptee, Pate’s work shifts to the process by which the adoptee appears as part of a problematic kinship system in which his or her Korean past is disavowed. Here, Pate takes a nod from David L. Eng’s work in which he links adoptees to queer theory in relation to kinship. Pate’s point in this final chapter—and perhaps one of her strongest—is that the adoptee cannot have two mothers or two families in the official scripted version of the story. At the same time, engaging analyses of adoptee narratives—for instance, Jane Jeong Trenka’s outstanding the Language of Blood—shows how adoptees can resist the restructuring of kinship into a white heteronormative form. The reading here could have been strengthened with a more extended look at Trenka’s follow-up Fugitive Visions (though Pate does refer to it in her conclusion) which does complicate the nature of the adoptee’s attempts to reconstruct a semblance of family. Pate’s work is wide-ranging, highly compelling and certainly an incisive addition to American studies, transnational studies, and orphan/adoptee studies.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/From-Orphan-Adoptee-Genealogies-Incorporated/dp/0816683077/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1404938825&sr=8-1&keywords=Soojin+pate

A Review of Joseph Jonghyun Jeon’s Racial Things, Racial Forms: Objecthood in Avant-Garde Asian American Poetry (University of Iowa Press, 2012).

I read Joseph Jonghyun Jeon’s brilliant monograph Racial Things, Racial Forms: Objecthood in Avant-Garde Asian American Poetry awhile back but it’s taken me some time to write up anything on it. This work is part of the Asian American new formalisms wave that has been particularly robust in the poetry arena, especially with works by Steven Yao, Xiaojing Zhou, Josephine-Nock Hee Park, and Timothy Yu. Jeon’s work is in some sense a natural extension of Yu’s monograph on its focus on the avant-garde, but takes its own unique and exciting direction, especially with respect to poets and poems that do not necessarily depict race in more direct or transparent ways. This issue is perhaps most critical in avant-garde poetry due to formal experimentation and highly fragmented style; there is no narrative and often no explicit social contexts from which to draw a “racialized” reading. Jeon’s introduction, for instance, makes clear that art and poetry must not only be read with respect to lyrical content but for the conditions and contexts in which art and poetry is produced. This approach clarifies how race moves outside a particular poem or lyric but can still necessarily influence its creation and how process that must be taken into account in critical reading practices. Further still, Jeon is highly invested in forms of comparison and for Jeon, “objecthood” or thinginess in Asian American avant-garde poetry is a way to get at the issue of racial representation and how it can be encrypted or alternatively represented in lyric. He goes about comprehensively and commandingly backing up his claims in his luminous readings of various Asian American avant-garde poets and their respective creative works; these include chapters and analyses devoted to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Myung Mi Kim, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Cathyong and John Yau. Though, by now, those within the field are well familiar with these names, the brilliance of Jeon’s work is in how he can interpret lyric through this hermeneutic of “object” analysis, thus reinvigorating how we see and understand avant-garde poetry. Rather than conveying a postrace aesthetic, these lyrics, poems, and associated collections continue to mine the fertile terrain of social inequality, oppression, and power dynamics in ways that are intricate, multipronged, and certainly sophisticated. Perhaps, my favorite chapter was the one that focused on Berssenbrugge: Jeon opens with a highly provocative conceit concerning the use of “tails” in Berssenbrugge’s collaborative work. The “tail” becomes a signifier not only of an excess, but also aberrance and oddity, a feature which gets elliptically connected to racial difference. One of the most interesting features of this chapter is the material nature of poetry collections; as Jeon points out, the paper stock used in one of the poetry collaborations came from Nepal, showing us the more encrypted ways by which ethnicity emerges. Later, still, Jeon takes the chapter in a wholly surprising direction with the X-ray, mining Berssenbrugge’s interest in science, one that certainly calls attention to the metaphysical nature of her poetry. The X-ray, as Jeon directs us to “see,” becomes an apparatus for Berssenbrugge to introduce discourses related to visuality: transparency, color, what can and cannot be found underneath the surface of things. Again, here, the technology of the x-ray is itself a circuitous mode by which to introduce racial discourses. Readings of bodies and organs appear more largely in Jeon’s analyses through which issues of labor, capital, and colonialism are consistently invoked. Perhaps, most importantly, Jeon’s effortless readings give us so many ways to enjoy the work of Asian American poetry and remind us of the field’s infinite interpretive variances. A must-read for any poetry fan, Asian American cultural critic, and devotee of inspiring literary analysis.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Racial-Things-Forms-Objecthood-Avant-Garde/dp/160938086X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1405352858&sr=8-1&keywords=racial+things+racial+forms

A Review of Wendy Law-Yone’s A Daughter’s Memoir of Burma (Columbia University Press, 2014).

I was thrilled when I saw that Wendy Law-Yone had published a new novel a couple of years back called the Road to Wanting. Unfortunately, that book was not published in the United States. But, Law-Yone also saw fit to follow suit quite quickly with her newest publication, A Daughter’s Memoir of Burma, which is available stateside through Columbia University Press. This rigorously researched hybrid work—part biography, part autobiography, part history—is a project that Law-Yone took on as a kind of promise to her father, who had amassed an archive of papers and documents that could be used later to recreate a narrative concerning his life and his work. Law-Yone eventually heeded this call, which is this publication. As Law-Yone effectively points out, her father’s life is a useful jumping off point to discuss not only an extraordinary personal and family history, but also a larger national and independence narrative. Indeed, Law-Yone’s father ran a very prominent newspaper in Burma called The Nation, which emerged not soon after the country gained independence and had survived the ravages of World War II. Law-Yone’s family certainly struggled in the period prior to Burma’s independence, but they saw a short period of prosperity once the newspaper took off and eventually gained a loyal readership. But, readers can obviously expect a change of events, especially because of the country’s long military governance, one that saw the reduction in civil liberties, the imprisonment of dissidents, and the massacre of revolutionaries. Not surprisingly, Law-Yone’s father is eventually arrested, his work for the newspaper considered subversive. Law-Yone herself eventually is able to escape the country through a marriage with a writer. Law-Yone’s father will eventually be freed and Law-Yone’s entirely family will eventually exist in exile, with most living either in another country in Asia or in the United States. Even while in exile, Law-Yone’s father continues to dream of revolution, trying to rally rebel groups primarily stationed in Thailand. With little funding and little international support, the exiles and the dissidents find it difficult to produce any real results and Burma continues to be ruled by a violent military junta. Law-Yone herself must deal with a disintegrating divorce, internal tensions in the family (especially over her brother Alban’s struggle with schizophrenia), even while maintaining a career that sees the publication of two acclaimed novels (The Coffin Tree and Irrawaddy Tango) and raising three children (one the product of her husband’s prior marriage). The conclusion is a fascinating look at Law-Yone’s archival research, one that is able to track both her maternal and paternal grandfathers’ origins, the former being a British national and the latter a Chinese merchant. Throughout Law-Yone exerts a respectful and almost hagiographic view of her parents, who clearly lived extraordinary lives. If there is a critique to be made of the book, it is that the narrative occasionally flags due to the generally flattened tone that occasionally surfaces because Law-Yone sticks to a very detailed script, one that must have been painstaking to create and to outline. To be sure, Law-Yone could not consistently generate a dynamic narrative because there are so many tasks to complete: her father’s biography, her family’s exile, her own coming-of-age, and the struggle of a country to find a more democratic rule. The continuing dearth of publications in the United States penned by those of Burmese descent makes Law-Yone’s work quite pivotal in its depiction of an obscured social history.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Daughters-Memoir-Burma-Wendy-Law-Yone/dp/0231169361/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1407531883&sr=8-1&keywords=wendy+law-yone

August 5, 2014

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for August 5, 2014.

In this post, reviews of Lisa See’s China Dolls (Random House, 2014); Evonne Tsang’s I Love Him to Pieces (My Boyfriend is a Monster); illustrated by Janina Gorrisen (Graphic Universe, 2011); Mukul Deva’s Weapon of Vengeance (Tor Forge, 2014); Hoa Pham’s The Other Shore (Seizure, 2014); Samrat Upadhyay’s The City Son (Soho, 2014).

A Review of Lisa See’s China Dolls (Random House, 2014).

Lisa See branches out somewhat in her latest offering China Dolls, which takes on the pre-World War II American context from the perspective of three young Asian American women who are seeking fortune and fame in the performance arts. The setting is San Francisco California and we have three narrators: there is Grace, the very Americanized runaway from Plain City, Ohio, looking for a fresh start in life after running away from harsh physical abuse from her father; there is Helen, the seemingly filial daughter of a very Confucian Chinese American immigrant family; and lastly, there is Ruby, the sensual and popular Japanese American masquerading as a Chinese American. All three are looking to get hired in Chinatown. Helen and Grace are able to land jobs, but Ruby’s ethnic passing is occasionally unmasked and she must work elsewhere. Ruby’s job leads her to work for the Golden Gate International Exposition, but her occupation requires her to be in various stages of undress. All three begin to experience various difficulties in family life, romances, and most of all their friendships with each other. First, Grace falls in love with a military man named Joe, failing to realize that he has been carrying on with Ruby. When Grace and Helen walk in on Ruby and Joe mid-coitus, Grace runs away from Chinatown to try to start a new life as a performer in Los Angeles. Helen ends up trying to find her and works with her to start up a kind of three person performance group with a man named Eddie, otherwise nicknamed the Chinese Fred Astaire. Ruby, for her part, achieves minor fame in San Francisco’s Chinatown as Princess Tai, while Helen, Eddie, and Grace struggle to make ends meet. Helen eventually becomes pregnant in an ill-advised affair with one of her employers and the three eventually return to San Francisco to work at the very same location that they first started at. As the novel goes on, the three must inevitably tarry with the historical milieu of World War II, which includes the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the internment of Japanese Americans, as well as the recruitment of Asian American men into the military. See is up for the challenge of twining together history with these three character trajectories and the plotting itself never flags. Though See has typically focused the construction of protagonists around Chinese and Chinese American characters, her use of a cross-ethnic perspective is an interesting choice that brings to mind the complicated positionality of Asian American panethnicity in the pre-World War II period. Fans of See’s fictional productions will see much in line with the feminist impulses of previous works, as she continues to mine the fragile alliances that women create amongst a patriarchal, sexist world. Late stage revelations in the narrative create an interesting and jarring reconfiguration of these three female characters and their tenuous friendships. The novel also functions with a kind of meta-marketing Orientalist conceit. The title itself might draw in those seeking an entertaining story of Oriental ladies who dance and perform, but as the novel shows, these three characters are well aware of the roles they must play and do what they can to exert agency within and beyond Orientalist paradigms.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/China-Dolls-Novel-Lisa-See/dp/081299289X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1403390234&sr=8-1&keywords=lisa+see+china+dolls

A Review of Evonne Tsang’s I Love Him to Pieces (My Boyfriend is a Monster); illustrated by Janina Gorrisen (Graphic Universe, 2011).

In I Love Him to Pieces, Evonne Tsang has penned an entertaining story of an unlikely couple—Dicey Bell and Jack Chen—who must work together to survive a zombie apocalypse. Janina Gorrisen takes on illustrating duties and helps flesh out—see what I did there—the narrative through her engaging visuals. Though Dicey is a jock and Jack is a nerd, they still find an attraction to each other, but even as their romance begins to bloom, the story shifts to focus on an outbreak of a dangerous fungus that has turned people into zombies. Thus, Dicey and Jack must find their way to a motel, while Jack uses his connections to get the CDC to help break them out of the city. Jack’s parents are important researchers and scientists and thus are able to provide Jack with a measure of security when the outbreak shows no signs of abating. Dicey’s family is an issue though and Jack must do what he can to find a way to bring them all to safety. The CDC and government agents finally arrive to whisk Dicey and Jack out of the city, but they run into zombie-trouble and many of the agents are either shot dead or infected. Jack himself suffers a bite from a zombie, but with the help from one agent, he is given experimental pills that may help him stave off a transformation. Though the narrative is obviously not that different from the many other zombie outbreak stories that are out there, the romance and chemistry between Dicey and Jack can’t be denied. They’re an odd couple that works and so you’re rooting for them to find a way to still be together, even as it becomes evident that Jack may be succumbing to the infection. The one element that I thought could have really improved the graphic novel would have been the inclusion of some other color palettes. Certainly, it would have cost quite a bit more in production to have had a graphic novel in full color but I kept thinking that the black and white tones could have been offset in energy through the tactical use of a third bright color. Since the zombies are always seeking for a bite to eat, the color red might have been a good choice to give the pages some more pizazz. The graphic novel does include some useful extras, including a hilarious “faux” interview at the conclusion and the artist’s note for the inspiration for the main characters (why they look the way they do). A fun, flesh-eating frolic through a zombie-infested land in which a fledgling romance is put into obvious peril!

Buy the Book HERE:

http://www.amazon.com/Love-Him-Pieces-Boyfriend-Monster/dp/076137079X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1404886605&sr=8-1&keywords=evonne+tsang

A Review of Mukul Deva’s Weapon of Vengeance (Tor Forge, 2014).

For some reason, when I began this book, I thought it was in the mystery genre (the dangers of not reading book jacket covers), but Mukul Deva’s Weapon of Vengeance is more like an action-thriller, one that could certainly see a big screen adaptation (with probabe revisions to its highly naturalistic ending). Deva’s third person narrative perspective primarily toggles between two main characters: Ruby Gill, a British national of half-Indian, half-Palestinian background who is a sort of double agent for MI6, which is a British military intelligence organization, and then her father, Ravinder Gill, with whom Ruby is estranged. Ravinder has just been promoted to a position to head the anti-terrorism task force that must oversee the successful inauguration of the Israeli-Palestinian peace summit being held in New Delhi. As a child, Ravinder and Ruby’s mother Rehana divorced and Ruby was raised to think that Ravinder had abandoned them. Ruby’s mission is to disrupt the Israeli-Palestinian peace summit by assassinating some of those in attendance. To help her out, she has teamed up with a former acquaintance, Mark, who is looking to help secure a set of guns that will enable them to carry out their terrorist attacks. Deva is interested in some sort of Oedipal/ Electra-complex relation here: Ruby realizes that she might have to kill her own father in order to carry out her plan. Ruby attends to her conflicted feelings by reminding herself of promises she has made her mother, but her internal struggle reveals a schizoid subjectivity: there is the daughter who seeks rapprochement with her father and there is the terrorist who seeks to kill anyone involved with upholding the safety of the summit (such as her father). Caught between these poles, Deva has created a naturalistic plot in the sense that it is clear that only one can survive. Will it be Ravinder and those seeking to protect the delegates for the summit, or will Ruby be able to carry out her brutal plan of vengeance? To answer this question, you’ll obviously have to pick up this book yourself, but another big sell for the novel is Deva’s own background as an a former member of the military. There is an author’s note that goes on to detail that many of the contextual references are based upon his knowledge of security and management of terrorism and hostage-type situations. It is clear from the kind of detail offered in this novel that Deva seeks to immerse the reader in an authentically constructed fictional world. Weapon of Vengeance is a fast-paced and intense action-thriller, certain to engage readers of others in this genre, such as Dan Brown or Tom Clancy.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Weapon-Vengeance-Mukul-Deva/dp/0765337711/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1405177821&sr=8-1&keywords=mukul+deva

A Review of Hoa Pham’s The Other Shore (Seizure, 2014).

Hoa Pham’s slim, but dense novella comes out of an Australian publishing house called Seizure. You can find out more about this press here:

http://seizureonline.com/

Interestingly enough, it seems as though the press is primarily run by volunteers and it’s clear that these individuals seek to publish books that push the boundaries of given genres and topics. In Pham’s The Other Store, the protagonist Kim Nguyen is a 16 year old Vietnamese girl who almost drowns. Though she survives, that event also bestows upon Kim particular gifts: she can now read minds and she can also speak to the dead. Once others get wind of her talents, Kim inspires both fear and avarice. Her father immediately wants to put her to work to gain more money, while a Communist party government employee hires her to help identify the remains found in mass graves. This individual also purportedly also possesses psychic powers, and they travel to different parts of Vietnam to go about their business. This process is challenging for Kim: she must confront dead ghosts whose families are still seeking their remains and clues about their fates. Additionally, the ghosts often have their own demands for recognition, and soon, news of her power reaches other spirit and human populations. Further still, once Kim identifies the remains, there are political ramifications. For instance, if the remains are identified as coming from a Vietnamese individual from the South, their remains may not necessarily be forwarded to their families, since they are linked to non-Communist governmental entities. Kim eventually realizes that she cannot escape the reach of the Communist party. A chance encounter with an overseas Vietnamese teenage boy (just one year older and also a psychic) makes her realize that she may be able to leave to America under the auspices of a short trip, while truly seeking asylum. Reverberations of the Viet Nam War appear all over this particular text, but it never surfaces directly, and this fiction presents another case of the shifting generational representations emerging from writers in this period. Pham’s novella is both an assured depiction of a character struggling to follow her Buddhist precepts while under the watchful eye of government power. Certainly, we might read this novel as a critique of nation-state formation following the war, especially with respect of corruption and continued violence directed toward particular communities who might be seen as subversive to the nation-state’s interests. Though ghostliness is a trope not necessarily new to Asian diasporic narratives (see Janie Chang’s Three Souls or Sandi Tan’s The Black Isle for recent examples reviewed here), Pham’s novella presents this spectrality from a dynamic direction, offering us a view of Vietnam from a post-war perspective. A surrealistic, lyrical and understated novel that shows us the lasting ramifications of the Vietnam War.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Other-Shore-Hoa-Pham/dp/1922057967/ref=tmm_pap_title_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1405782369&sr=8-1

A Review of Samrat Upadhyay’s The City Son (Soho, 2014).

Samrat Upadhyay’s follow-up to Buddha’s Orphans is the strange and disconcerting novel The City Son. Narrated from a shifting third person perspective, the novel (set in Nepal) follows a set of main characters wound together through tortured family dynamics. In this way, the plot reminds me very much of the work of Akhil Sharma in Family Life or Da Chen in The Last Empress, both novels which explore sexual assault and exploitation across generational divides. In this case, a wife, Didi, discovers her husband, Masterji, who is living in the city, has taken on a mistress (Aspara). Aspara has a son, Tarun, through Masterji, and Didi is determined to meet Tarun, to find out more about this little boy, but immediately readers are set off by the interest that Didi has in Tarun. She dotes on him, as if this child were her own, making him special dishes and certainly attempting to undermine the hold that Aspara has on Tarun. It is soon apparent that given Didi’s slightly elevated social position that she can offer Tarun things that Aspara cannot. Even when Aspara’s connection to a rich business magnate, Mahesh Uncle, offers her and her son a way out of their social positions, Didi’s emotional and affectual hold on Tarun has been firmly established. At this point, the novel takes a very dark turn: Didi begins an illicit love affair with this young boy, something that is carried over into adulthood. At that point, Tarun’s proxie father, Mahesh Uncle, is able to set up a suitable arranged marriage with a beautiful young woman, Rukma, who has a past of her own (involving a love affair with a man who ends up getting engaged and then marries another woman). Tarun and Rukma’s marriage is not surprisingly rocky from the start and Didi, with her incredible focus on Tarun, continues to exert a problematic pall over Tarun’s life in all ways. As with Chen’s The Last Empress, the novel leaves quite a lot of interpretive room in terms of how to situate this relationship in a larger social context. It becomes evident that one of the sources of tension appears in the social arrangements in Nepal that leave women in disempowered positions. Indeed, by the novel’s conclusion it is apparent Masterji’s original “sin” is one in which his own social position is never finally challenged, though the reverberations of his extramarital affair affect so many others, including his own sons, one of whom becomes a drug addict and the other whose disaffecting nature comes to be undermined by the eventual revelation of Didi’s relationship with Tarun. Thus, we might return to the novel’s title, “the city son,” to think about the ways that the movement toward urbanization creates ripples in traditional Nepalese family systems and metonymically shows the complicated trajectory for a country’s modernization process. Fortunately, even given the dark topic, Upadhyay’s sparkling prose renders this plot in a luminous light that grants grace to these damaged characters.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-City-Son-Samrat-Upadhyay/dp/1616953810/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1406818850&sr=8-1&keywords=samrat+upadhyay

August 3, 2014

A Review of G.B. Tran’s Vietnamerica (Villard, 2011)

GB Tran’s much-acclaimed Vietnamerica, a graphic memoir of his family’s history in Vietnam and the U.S., was published in early 2011, but I just got around to reading it, so I’m going to talk about it now. In addition to winning many awards, it has been much reviewed, including here (April 28, 2011), the

Although the story is bookended and filtered through the perspective of the American-born GB, his parents, and to a much lesser extent his siblings, most of the forward narrative drive takes place in Vietnam. Within this text, the U.S. is a place of remembering and reflection, while action – war, marriage, migration, even building one’s own house – takes place in a remembered Vietnam. It’s not a typical adjusting-to-life-in-America/generational conflict story, although these things are briefly alluded to. Like Maus, which it’s often compared to, the text is much more about excavating the traumas of the past that shape the present.

Vietnamerica is also visually intriguing. As other readers have noted, the pictures of people are very unstable; characters look different from page to page, perhaps highlighting the sense of uncertainty of memory. Tran makes full use of the space on and between the pages, particularly to convey senses of time. For instance, in two sections depicting imprisonment for long periods of time (Tran’s father in police custody; his father’s friend, Do, in a labor camp), the page’s panels depicting the monotonous horror are repeated in increasingly smaller size in the bottom, right-hand corner, in an infinite regression of fear, exhaustion, and violence. In another section towards the end, GB is learning about past events from family and friends. The events from the past are depicted in the panels on the bottom third of the verso (left) page and through the recto (right) page. GB’s question appears in the bottom right-hand corner of the recto page, which trails to the top of the next verso page, which takes us to the “present,” or the time and place of the telling. I also love the plays on communist Vietminh propaganda posters; I have a weird fascination with communist art.

Vietnamerica seems like it would be very teachable. I’d love to hear about your experiences with it in the classroom!

July 30, 2014

A Review of Carlos Bulosan’s The Cry and the Dedication (Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1995)

The Cry and the Dedication is Carlos Bulosan’s unfinished manuscript about socialist guerilla fighters in the Philippines in the 1940s and 1950s. Poet, novelist, and essayist Bulosan is best known for America Is in the Heart (1946), his semi-autobiographical story of Filipino American migrant farm workers on the West Coast. Cry and the Dedication has many of the same stylistic traits – particularly the soaring utopian rhetoric undercut by the depiction of harsh realities – but it is more definitely politically radical in its outlook than America.

The narrative centers on seven guerilla fighters (6 men and 1 woman) as they make their way across the countryside; each person represents different social classes – urban, rural, peasant, city worker, petit bourgeois, etc. They are headed to the city, where an ally from the U.S. will provide one million pesos for the resistance movement. As they progress, they pass through each person’s hometown, where almost invariably they encounter tragedy and/or betrayal. As E. San Juan notes in the introduction, these homecomings-that-are-not-homecomings suggest the impossibility of any kind of easy return home; at the same time, the seven also encounter glimpses of hope and possibility. Of the seven, arguably the two key characters are Dante and Hassim. Dante, who is 35 years old (just like the narrator-protagonist of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy), has lived part of his life in the U.S. and has returned to join the guerilla fighters and document their history. Hassim is the very young but wise leader of this group, a self-taught former factory worker in the city. The fates of these characters are very significant, as the introduction notes.

The great Marxist literary critic E. San Juan, Jr., provides the introduction that begins by describing his discovery of the manuscript amid Bulosan’s papers in the University of Washington archives. The introduction also provides historical and theoretical context for the novel, which is very helpful; Bulosan imagined the manuscript as part of a four-novel series about Philippine history. Unfortunately, Bulosan died young (age 42) from tuberculosis, so this final magnum opus was never realized.

Celeste Ng's Everything I Never Told You

This statement captures a moment prior to a horrible knowing, a moment still immersed in familiar feelings and relations among the family members. Lydia, the second child of three, has been the gravitational center of the family, bearing the brunt of her parents differing expectations and therefore becoming the only child who really received full attention in the family.

The novel churns through the aftermath of Lydia's death, with each parent struggling to make sense of the tragedy and what it means for their expectations of life (as lived through Lydia). Marilyn, the mother, particularly feels the loss since she invested so heavily in Lydia as a chance to recapture her dreams of becoming a doctor--a childhood plan derailed in her junior year at Radcliffe College when she became pregnant with her oldest son, Nathan (called Nath). She is a white woman from Virgina whose interest in science and being a doctor put her at odds with the prevailing ideas of women's work at the time, a contrast sharpened by the fact the her mother was her local school's home economics teacher and an adamant supporter of the idea that girls must learn to be good housewives. James Lee, the father, meanwhile, is a Chinese American professor of American history (specializing in cowboys) whose need to be just like white Americans leads him to feel shame at seeing his mixed-race son growing up like he did, never quite an insider in their Midwestern community in a small college town.

Nath, in the meantime, has been the supportive older brother to Lydia, understanding the terrible burden that Lydia faces as the only child who seems to matter to the parents. Of the three children, he seems to experience the most difficulties as a mixed-race Asian and white child in their all-white town, something his father disdains in him. And Hannah, the youngest daughter, is the forgotten member of the family who sees and hears much though rarely interacts with her parents or siblings.

In addition to these family members, the other key figure is their neighbor Jack, a suspicious neighbor in Nath's class who had been spending time with Lydia in the months before her death. Jack bears the brunt of Nath's anger in the aftermath of his sister's death, and he is convinced Jack is responsible for it.

This novel is a careful working through of the desires of each family member, particularly the parents and the two older children, in light of lifelong frustrations. James cannot get over being Chinese and different from other Americans. Marilyn cannot forget her dreams of becoming a doctor. Nath wants some approval from his parents, who only see Lydia. And Lydia, poor Lydia, understands that embodying her parents' expectations (to be friends with everyone for her father and to become a doctor for her mother) is the only thing that keeps their delicate family together. The narrative structure is full of flashbacks with the various characters, particularly the parents. In the present time frame, the story also proceeds forward from the day of Lydia's death through the police investigation and through the end of the school year for Nath.

This story treads familiar ground in terms of Asian American experiences in small towns as well as feminist concerns regarding women's work. I'm trying to think of other novels where there has been a Chinese American male character who so thoroughly internalizes a sense of racial self-hatred but can't think of any off the top of my head. The tragic mulatta narrative is present here, of course, with the death of a mixed-race characters as the center of the story. And there is another familiar narrative that emerges later in the novel that provides even more texture to the story, but I don't want to spoil it for people!

All in all, this novel is a welcome addition to the body of Asian American literature. It is particularly great for providing some reflections on 1950s experiences (James Lee as a graduate student in history at Harvard and Marilyn as a woman in the sciences) and the 1970s (Nath's obsession with space travel in the years after the first moon landing, for instance). It certainly fits in with other books that explore the complicated dynamics of family relationships.

July 22, 2014

A Review of Gene Luen Yang & Sonny Liew’s The Shadow Hero (First Second, 2014)

I just read Gene Luen Yang and Sonny Liew’s The Shadow Hero, their imagining of the origin story of the Green Turtle, the 1940s Asian American comic book hero (invented by cartoonist Chu Hing). They locate the Green Turtle’s origins firmly in Asian American history, with Hank, our hero-to-be, the son of immigrants and growing up in 1930s Chinatown while working in his father’s grocery store. It’s also a classic superhero origin story, with primal scenes of violence and hurt that will shape the hero’s quest in later life, but with an Asian Americanist take – a wry awareness of racial formations and racist stereotypes. Basically, Shadow Hero is awesome and you should all run out and read it immediately.

I just read Gene Luen Yang and Sonny Liew’s The Shadow Hero, their imagining of the origin story of the Green Turtle, the 1940s Asian American comic book hero (invented by cartoonist Chu Hing). They locate the Green Turtle’s origins firmly in Asian American history, with Hank, our hero-to-be, the son of immigrants and growing up in 1930s Chinatown while working in his father’s grocery store. It’s also a classic superhero origin story, with primal scenes of violence and hurt that will shape the hero’s quest in later life, but with an Asian Americanist take – a wry awareness of racial formations and racist stereotypes. Basically, Shadow Hero is awesome and you should all run out and read it immediately.An extra-special touch is the section at the end that provides the publication history of the original 1944 Green Turtle comic, including the publisher’s unwillingness to make the hero Asian American and cartoonist Hing’s subversion of that decision. Also included is a reproduction of the entire first Green Turtle adventure, from Blazing Comics #1, which is fascinating and complicated on a number of levels.

Gene Luen Yang is the much-acclaimed author of American Born Chinese (reviewed 2011-02-10), Level Up (reviewed 2011-11-26), Boxers and Saints (reviewed 2013-09-21), and other works. Sonny Liew is a comic artist based in Singapore who is known for Malinky Robot and My Faith in Frankie.

The Shadow Hero was originally published as monthly e-issues, with original cover art for each issue, and the full graphic novel was published earlier this month. There’s also a book trailer here (as well as links to buy the book): http://geneyang.com/the-shadow-hero.

July 21, 2014

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for July 21st, 2014

Questions/ concerns/ comments? Please e-mail me at ssohnucr@gmail.com . With apologies as always for factual inaccuracies, grammar and spelling mistakes, etc.

In this post, reviews of Alex Tizon’s Big Little Man: In Search of my Asian Self (Houghton Mifflin, 2014); Kalyan Ray’s No Country (Simon & Schuster, 2014); Kim Moritsugu’s The Oakdale Dinner Club (Dundurn, 2014); Franny Choi’s Floating, Brilliant, Gone (Write Bloody Publishing, 2014) with illustrations by Jess Chen; and Hieu M. Nguyen’s This Way to the Sugar (Write Bloody Publishing, 2014).

A Review of Alex Tizon’s Big Little Man: In Search of my Asian Self (Houghton Mifflin, 2014).

For those unaware of issues related to Asian American men and masculinityd, Alex Tizon’s Big Little Man will certainly be a revelation. In line with the searing memoirs of David Mura (Turning Japanese and Where the Body Meets Memory), Alex Tizon explores the challenges of growing up as an Asian American man, one who must contend with prevailing stereotypes concerning submissiveness, lack of desirability, nerdiness, and other such related issues. Tizon’s journalistic background emerges at the forefront of this book, especially as numerous facts and issues appear in relation to Asian American history and gender issues. At the same time, what really grounds this work is the personal story behind Tizon’s own upbringing, especially in the ways that his mother and father adjusted or did not adjust to living in America. Tizon’s foregrounds how his mother, as an Asian American woman, was able to deal with the acculturation process better due to the fact that her gender allotted her certain advantages. On the other hand, Tizon’s father finds himself lacking and begins to register this lack in his slow and undignified disintegration. Ultimately his parents end up getting divorced. Tizon brings up a controversial point concerning the bifurcation of racial formation for Asian American men and women. According to Tizon, Asian American women, who are ultimately hypersexualized, but yet still desirable, are able to negotiate the challenges of social marginality in ways that Asian American men, who register as nonsexual entities, cannot. The danger in Tizon’s position is that it does not fully engage the ways in which hypersexualization and supposed desirability of Asian American women still stands as oppressive, dangerous, and problematic in its construction (see Celine Shimizu’s The Hypersexuality of Race for more on this issue, for instance). Nevertheless, Tizon’s points concerning Asian American manhood are right on the mark; his knowledge of popular culture reveals that white supremacy remains embedded in the construction of the filmic and televisual imaginary. Given the four decades that have passed since Frank Chin and his fellow editors screamed Aiiieeeee, it’s amazing how little things seem to have changed for Asian American men and whether or not there will ever be a bona fide A-list Asian American actor to emerge on the Hollywood scene (certainly, there have been some successes such as Sessue Hayakawa, James Shigeta, Jason Scott Lee, and John Cho, but few would argue that these figures achieved true mainstream recognition).

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Big-Little-Man-Search-Asian/dp/0547450486/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1402086648&sr=1-1&keywords=alex+tizon

A Review of Kalyan Ray’s No Country (Simon & Schuster, 2014).

(best image I could find)

Kalyan Ray’s No Country (his second novel after Eastwords, which is only available through Penguin India… my long-standing gripe against publication rights and the limits it affords the transnationally-driven bookworm) is truly an epic novel, the kind of which you do not see quite often in this age of twitter, short facebook updates, and lightning fast news clips. Clocking in at over 500 pages, Ray is able to maintain momentum through key perspective shifts that together create a transnational tapestry of a dispersed set of families. The novel open with a mystery: a South Asian American woman’s parents have been found murdered. The novel then moves back into the 19th century to Ireland where we learn of the star-crossed love affair between Brigid and Padraig Aherne. The narration alternates in this section primarily among three characters: Padraig; Brendan McCarthaigh (Padraig’s best friend); then Padraig’s daughter with Brigid, Maeve). Early on in the novel, Padraig and Brigid are separated. Padraig’s investment in politics results in an accidental death and he is forced to assume the identity of someone else, someone bound for India. Back in Ireland, Brigid dies in childbirth; her daughter Maeve survives. While Padraig attempts to find a way to get eventually back to Ireland, Brendan narrates about the Irish potato famine and how he, along with a schoolteacher and Maeve, are ultimately forced to flee to find a better life and settle somewhere in the New World. The boat upon which Brendan travels strikes an iceberg and is lost at sea, though Brendan and Maeve do survive (the schoolteacher does not). Later, when Padraig investigates what happened to his lover Brigid, he discovers upon return to Ireland that Brigid is dead, that his mother died in the midst of financial distress, and that many that he knew perished during the famine or vacated the area. Padraig also discovers that the ship Brendan and Maeve were on was lost at sea and he assumes they perished. Thus begins the major bifurcated narratives: a family in India, where Padraig marries an Indian woman and a family in the United States, where Brendan becomes a surrogate father to Maeve who ends up marrying a Polish Jew and bears a daughter named Bibi. From here, the novel continually moves forward in time, jumping between continents and narrators. By the time the novel concludes, readers are feverish for some sort of reunification between the two families, but the twining together of these disparate family trees finally occurs in such a way that it might surprise readers. Others may find the resolution unfulfilling for the simple reason that there is so much holding these families apart, there is a desire for some sort of measured and sustained conclusion/ unification that never quite arrives. The novel is obviously rigorously researched, as evidenced by the detailed notes that conclude this work, but the emotional heart seems apparent to appear in the earliest sections; it is Padraig, Brendan, and Maeve who seem to get the most storytelling time and you’re thinking back to them always as you move forward. Ray’s work is most contextually compelling on the level of its reconsideration of race and kinship: it elucidates the transnational nature of the 19th century, especially through the movement of goods and labor in the era of colonialism. In this sense, the novel has much in line with Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies and even Toni Morrison’s A Mercy, which sees the boat and the experience of the passage in its varied forms as a rupture point in which new relationalities must emerge, however traumatic or unexpected in their constructions.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/No-Country-Novel-Kalyan-Ray/dp/1451635990/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1403019656&sr=8-1&keywords=kalyan+ray

A Review of Kim Moritsugu’s The Oakdale Dinner Club (Dundurn, 2014).

There’s something deliciously wicked about Kim Moritsugu’s The Oakdale Dinner Club, a kind of answer we might say to the pleasant, sentimentalized versions of other clubs and social formations started by women (such as the Jane Austen Dinner Club or the one depicted in Darien Gee’s Friendship Bread). Indeed, Moritsugu, an (Asian) Canadian writer, has mastered a kind of snarky internal narrative voice that generates dark comic moments throughout her newest publication (we’ve reviewed some of her titles here, such as The Restoration of Emily and The Glenwood Treasure). Set in an exclusive Canadian suburb called Oakdale, the novel follows the lives of a group of colorful characters. Most of the narrative attention is focused on Mary Ann, a woman who is undergoing something of a midlife crisis, as her husband Bob has a wandering eye, and she yearns to get even by having an affair of her own. She whittles down the candidates to three individuals: Drew, her IT coworker; Tom, her staid, but pleasantly handsome work associate; and Sam Orenstein, the husband of a popular and beautiful Oakdale socialite named Hallie. Mary Ann’s partner-in-crime is Alice Maeda, a mixed race Japanese Canadian who is a free spirit of sorts. An anthropologist by profession, Alice has moved back to Oakdale to raise her four-year-old daughter, Lavinia, the product of one of her numerous and ephemeral love affairs. Mary Ann hatches the idea of the Oakdale dinner club, inviting a set of participants that are more or less well-known for their abilities to cook or for their interest in things culinary. Of course, the Oakdale dinner club will also include the three men with whom Mary Ann is considering for her extramarital affair. Alice’s own storyline takes a romantic turn when she bumps into an old high school friend, Jake Stewart. Though Jake has aged—he has become bald—Alice realizes that she still harbors an interest in him and decides to pursue getting to know him better. Other important, but more minor characters in this novel include Sarah, Mary Ann’s mother, who at some point got divorced but never remarried and Danielle Pringle, a more working-class mother who feels out of place in the very upscale neighborhood of Oakdale. Moritsugu does a wonderful job of weaving the stories together. With its biting humor and sarcastic wit, Moritsugu’s work makes for a fast-paced, decadent, and entertaining read. Though I figured I would start reading the novel and finish it the next day, I stayed up to read it all in one sitting, wondering about how Mary Ann’s pursuit of extramarital interests would end up and how the Oakdale Dinner Club would turn out. The conclusion also sees a handful of recipes that make the novel more interactive than I would have guessed.

Buy the Book here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Oakdale-Dinner-Club-Moritsugu/dp/1459709551/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1403971800&sr=8-1&keywords=kim+moritsugu

A Review of Franny Choi’s Floating, Brilliant, Gone (Write Bloody Publishing, 2014) with illustrations by Jess Chen; A Review of Hieu M. Nguyen’s This Way to the Sugar (Write Bloody Publishing, 2014).

I’ve been reading a couple of titles out of the independent press out of Austin, Texas, with a witty name called Write Bloody Publishing (indeed, it almost seems a requirement these days for the indie press to have a funky, interesting name). More information about the press can be found here and I hope to get to review some others in time from that same press:

http://writebloody.com/

Franny Choi’s Floating, Brilliant, Gone is a collection that is part of an emergence of Asian American poetic writings which are directly influenced by previous Asian American cultural producers. By making this statement, I mean to say that Choi’s collection begins with an epigraph from one of my favorite novels ever: Alexander Chee’s Edinburgh. The quotation Choi picks is one directly related to loss, and it is one that will structure and influence the many poems that will appear afterword. Though Choi’s lyrics are particularly affecting, she’s got a clear knack for word play and doesn’t stray away from avant-garde impulses, especially with the layout of words on the page and different visual constructs. The illustrations provided by Jess Chen are a nice touch and create a gothic ambience to the darkly playful lyrics. I’ve focused on a couple below that I think are most illustrative of Choi’s ability to engage in lyric wordplay and politicism:

In “Kimchi,” Choi employs some ethnic food imagery as an extended metaphor to engage the problematic tension in one Korean American family:

My parents’ love for each other

was pickled in the brine of 1980,

spent two decades fermenting

in an air-tight promise.

Their occasional salt caught

a slow fever, began to taste like

a buried secret. They choked

in each other’s vinegar, dug for pockets

of fresh-cut love, once green and whole,

now a shrunken head, floating.

Every night, she pulls it, messy and

barehanded, out of the jar, slices it

into slivers, and we all swallow,

smiling through the acrid burden

kicking in our throats (26).

I love the melancholic sentiment here: the experience of loss and degradation found in a food, one that used to signify something else entirely. The idea of this marital union as undergoing a kind of pickling process is, I think, just a fun and sardonic way of approaching this issue. In “To the Man who Shouted ‘I like Pork Fried Rice’ at Me on the Street,” readers can see Choi’s gift for a kind of sonic coherence, the dynamics of flow from one line to another.

so call me

pork: curly-tailed obscenity

been playing in the mud. dirty meat.

worms in your stomach. give you

a fever. dead meat. butchered girl

chopped up & cradled in Styrofoam

for you – candid cannibal.

want me bite-sized

no eyes to clog your throat (38)

The repetition of the “c” generates an alliterativeeaffect, particularly a kind of piquant sound that generates more aggression in the tonality of this passage. I find the phrase “candid cannibal,” both poignant and caustic, this idea that the lyric speaker can be consumed as an ethnic Other, but that she is ultimately undigestible to this racist figure. In “Gentrifier,” Choi’s lyric speaker observes the changes going on in a neighborhood, not all of which can be commended:

the new grocery sells real cheese, edging out

the plastic bodega substitute, the new neighbors

know how to feed their children, treat themselves

to oysters sometimes, other times, to brunch, finally,

some good pastrami around these parts, new café

on broadway, new trees in the sidewalk, everyone

can breathe a little easier, neighborhood association

throws a block party, builds a dog park right

at the middle of the baseball field, crime watch listserv

snaps photos of suspicious natives, how’d all these ghosts

get into my yard? cop on speed dial, arrange flowers

as the radio croons orders, rubber on tar,

skin on steel, an army of macbook pros guarding

its French presses, revival pioneers, meanwhile,

white college grads curse their racist neighbors,

get drunk at olneyville warehouse punk shows,

ride their bikes on the right side of the road, say west end

like a badge, while folks on the other side of cranston street

shake their heads and laugh. interrogation lamps

burning down their stoops, banks gutting their houses (50).

The strength here is in the common images of gentrification that are refigured in unexpected ways: the personification of the Macbook pros, the class pretensions that appear in improved cuisine choices, how elegance and etiquette can be found in words and phrases. The interior monologue signaled by the italics is a nice touch, giving this poem an extra edge of acerbic humor. Choi’s Floating, Brilliant, Gone is anything but absent; it is a collection with a commanding presence, certainly full of buoyancy and luminosity.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Floating-Brilliant-Gone-Franny-Choi/dp/1938912438/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1404423340&sr=8-1&keywords=Franny+Choi

Hieu M. Nguyen’s poetry collection This Way to the Sugar seems to suggest a sort of culinary theme to the book, but it’s more of a false tell. There are certainly references to food and to sugar, but Nguyen’s lyrics are largely concerned with the bodily and the corporeal. The autobiographical tinge of these lyrics give it a kind of intimacy not unlike Franny Choi’s work in the previously reviewed Floating, Brilliant, Gone. Here, there are some issues with acculturation and assimilation that do come up, especially as the generational divide between Vietnamese immigrants and their children brings about certain tensions (in poems like “Tater Tot Hotdish” and “Buffet Etiquette”). In other poems, Nguyen’s lyric speakers will bravely and gamely take on feelings related to budding queer sexualities in a variety of ways: pretending to take on internet identities in one case (“A/S/L”), and meeting for anonymous sexual encounters at a hotel room in another (“Christmas Eve, 17”). In one of the most poignant poems, “Stubborn Inheritance,” the lyric speaker describes the aftermath of his coming out process to his mother:

It look my mother eight years

to accept me for being gay. For eight years I sat

and watched my house burn. I watched her save the baby

photos but leave the baby—I know I should be grateful

that she came around at all. That she forgave me.

I’ve been told that it’s not her fault. It is how she was

raised. I’ve been told that it’s our family’s old way

of thinking. I’ve been told to forgive this

stubborn inheritance, this thing that has lived

inside her, and her mother, and her mother’s father—

I’ve been told that once you’ve been stabbed, it is better to leave

the blade inside the body—removing the dagger will only open

the wound further. Forgiveness will bleed you think” (65-66).

The confessional quality of these lines is characteristic of Nguyen’s approach toward lyric construction. Never shying away from the messy, the mury, the surfeit that always comes with charged encounters, familial ruptures, sexual dalliances, This Way to the Sugar is irresistibly direct. Even in a case like “Stubborn Inheritance,” where it seems as if the rift between son and mother must be preserved, the collection ends with a wistful, melancholic sentiment in the poem, “Nostophobia”:

Grief like sugar

boiling on a tongue. I am terrified

of no longer being a son,

to have to attend a funeral

without her [71].

By this point, we understand that the way to the sugar is riven with loss and trauma and the always difficult process of maturation. In the more than capable lyrics hands of Hieu Nguyen, we will delight in the collection’s bittersweet flavors.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/This-Sugar-Hieu-Minh-Nguyen/dp/1938912446/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1405997451&sr=8-1&keywords=this+way+to+the+sugar