Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 57

July 3, 2013

John Yau and Thomas Nozkowski's Ing Grish

Ing Grish

(Saturnalia Books, 2005) is a book of poems by John Yau and artwork by Thomas Nozkowski. Yau's characteristic breadth of poetic experimentation and a self-referential and metacritical awareness of language and meaning are as usual present in the poems of this collection. The pairing of this poetry with Nozkowski's art is curious; it is definitely not the relationship of text-to-illustration but is a particular kind of juxtaposition that only barely puts the words and the visual art in conversation.

In the introduction to the book, Barry Schwabsky suggests that putting the work of this poet and visual artist together is in some ways simply an echo of how Yau builds an artistic community around himself, where people working in different media and with various perspectives on art come to associate with him and each other. But Schwabsky also suggests that both Yau and Nozkowski have an ability to exceed or frustrate expectations in their work. Furthermore, he writes that Nozkowski has a "fascination with the (possible arbitrary and contingent) associations that attach themselves to and modify any perception or memory," which points to an interest in the open-ended and constantly changing meanings of artworks. Schwabsky ultimately concludes, "What's at stake is a refusal of premature definition," and he notes that both Yau and Nozkowski share this intent on pushing for the disruption of too-easy-meaning.

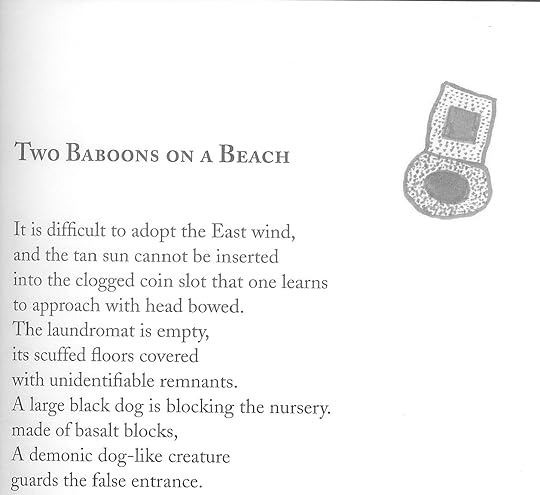

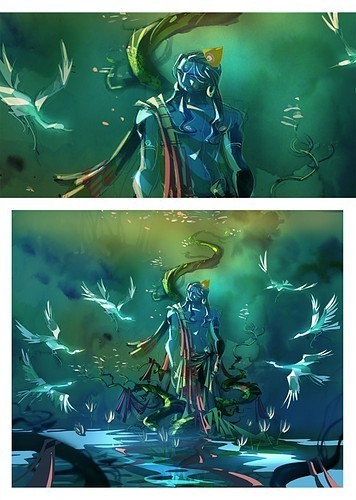

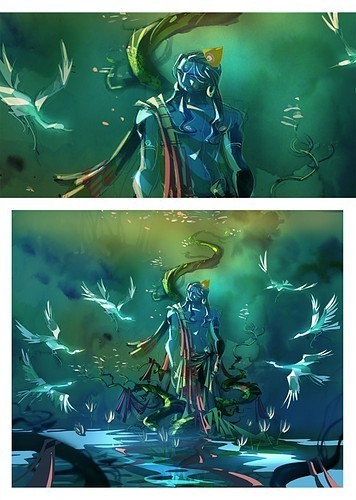

Small illustrations by Nozkowski, almost like cellular parts afloat in a cell, appear on some of the pages of Yau's poetry. The shapes are abstract but suggestive, sometimes absurdist in their connections (or lack of connection) to Yau's words. The beginning of "Two Baboons on a Beach" depicted above shows a shape composed of a square squished against a circle. The list of objects observed at the beginning of the poem seem similarly to be a smooshing together of dissimilar things.

At other points, full-color art by Nozkowski are the only things on the page.

In "Diaspora," the speaker of the poem reminisces:

The final poem in the book is the title poem, "Ing Grish," full of insightful comments about corrupting language and cultural critique.

Both the poems by Yau and the art by Nozkowski are thoughtfully enigmatic at times.

In the introduction to the book, Barry Schwabsky suggests that putting the work of this poet and visual artist together is in some ways simply an echo of how Yau builds an artistic community around himself, where people working in different media and with various perspectives on art come to associate with him and each other. But Schwabsky also suggests that both Yau and Nozkowski have an ability to exceed or frustrate expectations in their work. Furthermore, he writes that Nozkowski has a "fascination with the (possible arbitrary and contingent) associations that attach themselves to and modify any perception or memory," which points to an interest in the open-ended and constantly changing meanings of artworks. Schwabsky ultimately concludes, "What's at stake is a refusal of premature definition," and he notes that both Yau and Nozkowski share this intent on pushing for the disruption of too-easy-meaning.

Small illustrations by Nozkowski, almost like cellular parts afloat in a cell, appear on some of the pages of Yau's poetry. The shapes are abstract but suggestive, sometimes absurdist in their connections (or lack of connection) to Yau's words. The beginning of "Two Baboons on a Beach" depicted above shows a shape composed of a square squished against a circle. The list of objects observed at the beginning of the poem seem similarly to be a smooshing together of dissimilar things.

It depends upon your pronunciations

It depends on whether the emphasis

Is on phlegm or ish

As in

do you speak Flemish

At other points, full-color art by Nozkowski are the only things on the page.

In "Diaspora," the speaker of the poem reminisces:

Upside down, the wok looked like a flying saucer, so I carefully surrounded it with rows of plastic Indians and Cuban gueriillas dressed like American marines. The only problem was that none of them had beards. It was the Fifties but already I was on the wrong side.I like the oblique reference to the Cold War, sci-fi alien stories, and nationalism.

The final poem in the book is the title poem, "Ing Grish," full of insightful comments about corrupting language and cultural critique.

I do not know Ing Grish, but I will study it down to itsThe claims the speaker makes about not knowing language unfurl into commentary about cultural misunderstanding and judgements about people based on the languages they do or do not speak and the ways they speak languages (with accents or in pidgin forms).

black and broken bones.

Because I do not know Chinese I have been told that meansTo speak a language or not to speak a language because a claim for and against cultural identity, to be authentic or not.

I am not Chinese by a man who translates from the Spanish.

Both the poems by Yau and the art by Nozkowski are thoughtfully enigmatic at times.

Published on July 03, 2013 12:26

Bino A. Realuyo's The Gods We Worship Live Next Door

Bino A. Realuyo's

The Gods We Worship Live Next Door

(University of Utah Press, 2006) is a historically-oriented collection of poems, considering the layers of colonialism that have structured Filipino lives in the archipelago and the diaspora.

Realuyo's work echoes other Filipino American poets' thoughtful engagements with language, history, transnational movements, and identity. Many of Realuyo's poems in this collection include prefatory notes about the historical situation addressed. For example, "Consummatum Est (It is finished)" includes a headnote that reads, "U.S. military bases in the Philippines were officially closed in 1992. Departing American servicemen left behind more than 30,000 unacknowledged children born to Filipino girlfriends and bar girls." And the poem ends with a footnote that the title comes from the "alleged last words of Jose P. Rizal, a national hero of the Philippines before he was shot by a firing squad in 1896, two years before Spain surrendered to the U.S. to end the Spanish-American war." These notes are helpful for framing the poems themselves and offer important starting points for readers to understand the enfolding of historical events into poetic exploration.

The Gods We Worship Live Next Door contains six sections of poems. The first focuses on diaspora, the second on the Spanish colonial era (1565–1898), the third on the U.S. colonial era (1898–1946), the fourth on the Japanese colonial era during World War II (1942–1946, overlapping with U.S. rule), the fifth on witnessing, and the sixth on a long poem titled "The Gods We Worship Live Next Door," which is a phrase borrowed from a poem by Filipino American writer Bienvenido Santos.

The first poem in the collection, "Filipineza," begins with the note, "In the modern Greek dictionary, the word 'Filipiniza' means 'maid.'" The poem imagines the position of Filipino maids in the diaspora:

While the poems in the first four sections focus on diasporic and historical realities for Filipinos, the poems in the fifth section imagine the subjectivity of people in the contemporary Philippines, especially the interiority of people referenced in news stories (often sensational ones). "The Pepper-Eater," for instance, takes as a starting point a news item about the Guinness Book of World Record holder for most hot peppers eaten. The speaker of the poem is a champion pepper eater, where the act of eating hot peppers becomes a metaphor for a fiery engagement with life.

The long poem, "The Gods We Worship Live Next Door," takes an interesting approach to considering religious conflict and political strife in the Philippines, focusing on Islamist separatist groups engaging in guerrilla warfare in the Mindanao region and struggles with Communist forces. The poem seems brings Catholic imagery, especially of mother and child (Mary and Jesus), to bear on questions of war, neighborliness, religious difference, and nationalism. In particular, the poem considers the sexual violence men bring to bear on women during war and the effects of such oppressive acts and conditions on children as well. This poem bears witness to the horrible situation of war and the question of how God or gods allow such suffering.

Realuyo's work echoes other Filipino American poets' thoughtful engagements with language, history, transnational movements, and identity. Many of Realuyo's poems in this collection include prefatory notes about the historical situation addressed. For example, "Consummatum Est (It is finished)" includes a headnote that reads, "U.S. military bases in the Philippines were officially closed in 1992. Departing American servicemen left behind more than 30,000 unacknowledged children born to Filipino girlfriends and bar girls." And the poem ends with a footnote that the title comes from the "alleged last words of Jose P. Rizal, a national hero of the Philippines before he was shot by a firing squad in 1896, two years before Spain surrendered to the U.S. to end the Spanish-American war." These notes are helpful for framing the poems themselves and offer important starting points for readers to understand the enfolding of historical events into poetic exploration.

The Gods We Worship Live Next Door contains six sections of poems. The first focuses on diaspora, the second on the Spanish colonial era (1565–1898), the third on the U.S. colonial era (1898–1946), the fourth on the Japanese colonial era during World War II (1942–1946, overlapping with U.S. rule), the fifth on witnessing, and the sixth on a long poem titled "The Gods We Worship Live Next Door," which is a phrase borrowed from a poem by Filipino American writer Bienvenido Santos.

The first poem in the collection, "Filipineza," begins with the note, "In the modern Greek dictionary, the word 'Filipiniza' means 'maid.'" The poem imagines the position of Filipino maids in the diaspora:

If I became the brown woman mistakenThe speaker of the poem is a Filipina maid who has left family and home like millions of other Filipinos (mainly women) who work all over the world in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East to remit money to their families in the Philippines.

for a shadow, please tell your people I'm a tree.

The better to work here in a house full of faces I don't recognize.The poem turns on the figure of Elena, another Filipina maid who disappeared while she was working as an overseas maid. Elena is a cautionary figure for other Filipinas, as the speaker's mother warns her, and the speaker imagines that she had a child by her married employer and then went off into the foreign world to live a secret life, becoming "part myth, part mortal, part soap."

Shame is less a burden if spoken in the language of soap and stain.

My whole country cleans houses for food

While the poems in the first four sections focus on diasporic and historical realities for Filipinos, the poems in the fifth section imagine the subjectivity of people in the contemporary Philippines, especially the interiority of people referenced in news stories (often sensational ones). "The Pepper-Eater," for instance, takes as a starting point a news item about the Guinness Book of World Record holder for most hot peppers eaten. The speaker of the poem is a champion pepper eater, where the act of eating hot peppers becomes a metaphor for a fiery engagement with life.

Oh, this flavor, this life! If sweetness reveals the fruit,The intensity of peppers' heat resonates with the speaker's town's heat, with its "hot-tempered men, / exposed torsos all day, hungry for a night of peppery-itch."

our character hangs on the burning flesh of bulbous peppers.

The long poem, "The Gods We Worship Live Next Door," takes an interesting approach to considering religious conflict and political strife in the Philippines, focusing on Islamist separatist groups engaging in guerrilla warfare in the Mindanao region and struggles with Communist forces. The poem seems brings Catholic imagery, especially of mother and child (Mary and Jesus), to bear on questions of war, neighborliness, religious difference, and nationalism. In particular, the poem considers the sexual violence men bring to bear on women during war and the effects of such oppressive acts and conditions on children as well. This poem bears witness to the horrible situation of war and the question of how God or gods allow such suffering.

Published on July 03, 2013 08:45

July 1, 2013

Shin Yu Pai's AUX ARCS

Fresh off the presses today is Shin Yu Pai's latest poetry collection AUX ARCS (La Alameda Press, 2013).

The book takes its name from the Ozarks, a distinctive geological region in the American South, and a central theme throughout is the landscape, both geographical and social, of the South. Interestingly, the origins of the name Ozarks are uncertain. The term aux arcs serves as folk (faux) etymology, suggesting linguistic corruption of French and the messy intertwining of language, cultures, histories, and peoples that makes up the Americas. Pai's use of AUX ARCS as the title of the collection participates in this sort of genealogical excavation of naming and knowing.

Enchanted Rock, Llano Uplift, TX, digital photo, 2010.

AUX ARCS is both a textual and visual poetic collection, with photographs by the author dispersed throughout. Even before the first poem, just after the copyright page, is an image of broad land from the high vantage point of Enchanted Rock in Texas. The image is open and inviting. In the book, the photographs are not labeled, encouraging contemplation of what is in the image and how the image might connect with the ideas and words of the textual poems. A list at the back of the book provides the captions with location and other image information.

Skull & air conditioning unit, Lake Tawakoni, TX, mobile phone photo, 2006.

After the dedication page and before the first poem is a second photograph, one that signifies Texas with the skull of a Texas Longhorn steer mounted on the outside of a wooden structure next to the protruding backside of an air conditioning unit. The iconic image of the skull, reminiscent of a Wild West ethos and nostalgia, intriguingly sits jarringly next to an image of modernity and the fending off of excessive summer heat.

"Inner Space," the first poem of the collection, follows this image, bringing the speaker of the poem to "the cavern where / my Texan mate takes me to find / relief from heat." The relief of the cool interior space belies the speaker's thoughts of

A number of the poems deal explicitly with Asian American presences in the American South and with the jarring experience of racial bias in a region still thought of generally as one divided into (simply) black and white. "Main Street" witnesses white teenage boys who spit at the speaker of the poem as she exits the post office in town, caught in her thoughts of an academic world more supposedly more distanced from everyday gestures of racism. "Black and White and Red All Over" takes the image of "the boy with a scarlet dyed / mohawk" and his siblings/friends wearing "the red & white jerseys / emblazoned w/ wrathful ridge-/ backed peccaries" (a reference to the Arkansas Razorbacks), framing these boys as threatening with a reference to "their shaved heads" (possible skinheads?) and their clustering behavior. The poem ends with images of animals and the observation, "aware more than ever I am / scared witless by wildlife." It is not so much the dogs and cats and hantavirus she mentions that seem to truly terrify her, though, but the mentality of college sports fans.

A more playful poem, "Peabody Ducks," spreads words across the page in meandering fashion, exploring the famous ducks of The Peabody hotel in Memphis. The poem, however, also points to the somewhat unsavory history of ducks in the hotel. The first ducks there were live decoys (restrained or maimed to prevent their flight) used by duck hunters, who placed them in the hotel's fountain for fun. Pai's poem suggests that despite the domestication of ducks in this hotel space, they "hold true to their avian traits" and keep "one orb always open, / against predators."

Many of the poems also take food and the changing cultures of food as topics. "Hybrid Land," for instance, catalogs food products in a list:

Other poems in the collection relate aspects of Asian American history and culture, such as a poem about the "Iron Chink," a fish-cleaning machine made to displace Asian immigrant and Indigenous workers in the Pacific Northwest canneries. "On Seeing Roger Shimomura's Crossing the Delaware" offers a reflection on Shimomura's well-known revisionist painting and the cultural politics of morality, education, and history in U.S. schools.

Agora, Chicago, IL, digital photo, 2012.

There are many other wonderful poems in this collection. They range widely in geography, across the Americas and Asia. They touch on different topics, often examining the histories of things and places to shed light on contemporary circumstances and social relations. One section of poems focuses on animals, especially the control of them such as putting dogs down in shelters to control population ("Cull") or arranging them in museums as objects of knowledge ("Natural History").

Adapations, Iowa City, IA, digital photo, 2010.

I'd be remiss as a crazy dog person note to end with a few lines from "Working Dog, Do Not Pet," a thoughtful poem about the balance of domestication and wildness in dogs:

Order a copy from the wonderful Small Press Distribution.

The book takes its name from the Ozarks, a distinctive geological region in the American South, and a central theme throughout is the landscape, both geographical and social, of the South. Interestingly, the origins of the name Ozarks are uncertain. The term aux arcs serves as folk (faux) etymology, suggesting linguistic corruption of French and the messy intertwining of language, cultures, histories, and peoples that makes up the Americas. Pai's use of AUX ARCS as the title of the collection participates in this sort of genealogical excavation of naming and knowing.

Enchanted Rock, Llano Uplift, TX, digital photo, 2010.

AUX ARCS is both a textual and visual poetic collection, with photographs by the author dispersed throughout. Even before the first poem, just after the copyright page, is an image of broad land from the high vantage point of Enchanted Rock in Texas. The image is open and inviting. In the book, the photographs are not labeled, encouraging contemplation of what is in the image and how the image might connect with the ideas and words of the textual poems. A list at the back of the book provides the captions with location and other image information.

Skull & air conditioning unit, Lake Tawakoni, TX, mobile phone photo, 2006.

After the dedication page and before the first poem is a second photograph, one that signifies Texas with the skull of a Texas Longhorn steer mounted on the outside of a wooden structure next to the protruding backside of an air conditioning unit. The iconic image of the skull, reminiscent of a Wild West ethos and nostalgia, intriguingly sits jarringly next to an image of modernity and the fending off of excessive summer heat.

"Inner Space," the first poem of the collection, follows this image, bringing the speaker of the poem to "the cavern where / my Texan mate takes me to find / relief from heat." The relief of the cool interior space belies the speaker's thoughts of

the PermianThe references to a geologically distant past and extinct species that once roamed the region, coupled with the idea of the inner space as a retreat from the outside heat, echo the skull and air conditioner image. The past and the modern collide in both the poem and the image, and the apparition of death (in the Longhorn skull and in the memory of extinct creatures, knowable to modern scientists only in their excavated skeletons) lingers in the presence of the present.

floodwater maze that claimed

the lives of Ice Age species, mammoth

armadillo and sabre-toothed cat,

swamped in quicksand

A number of the poems deal explicitly with Asian American presences in the American South and with the jarring experience of racial bias in a region still thought of generally as one divided into (simply) black and white. "Main Street" witnesses white teenage boys who spit at the speaker of the poem as she exits the post office in town, caught in her thoughts of an academic world more supposedly more distanced from everyday gestures of racism. "Black and White and Red All Over" takes the image of "the boy with a scarlet dyed / mohawk" and his siblings/friends wearing "the red & white jerseys / emblazoned w/ wrathful ridge-/ backed peccaries" (a reference to the Arkansas Razorbacks), framing these boys as threatening with a reference to "their shaved heads" (possible skinheads?) and their clustering behavior. The poem ends with images of animals and the observation, "aware more than ever I am / scared witless by wildlife." It is not so much the dogs and cats and hantavirus she mentions that seem to truly terrify her, though, but the mentality of college sports fans.

A more playful poem, "Peabody Ducks," spreads words across the page in meandering fashion, exploring the famous ducks of The Peabody hotel in Memphis. The poem, however, also points to the somewhat unsavory history of ducks in the hotel. The first ducks there were live decoys (restrained or maimed to prevent their flight) used by duck hunters, who placed them in the hotel's fountain for fun. Pai's poem suggests that despite the domestication of ducks in this hotel space, they "hold true to their avian traits" and keep "one orb always open, / against predators."

Many of the poems also take food and the changing cultures of food as topics. "Hybrid Land," for instance, catalogs food products in a list:

recall Country Crock. The injunction to recall the products suggests both meanings of the word--either to remember these brands or to call it back due to defects. The next page of the poem turns on memories of more organic food practices:

recall Ocean Mist

recall Frontera

recall Nestle

I remember my mother peeling waxed skins from store-bought fruits.The poem contrasts the sterility of packaged products on the shelf and the messiness of growing fruits and vegetables.

I remember apples we grew — their skins dull, form misshapen.

I remember holes pecked by bird beaks scarring unripe peaches.

I remember the sweet stink of guavas rotting on the earth.

I remember pulling chives from the garden with my father.

Other poems in the collection relate aspects of Asian American history and culture, such as a poem about the "Iron Chink," a fish-cleaning machine made to displace Asian immigrant and Indigenous workers in the Pacific Northwest canneries. "On Seeing Roger Shimomura's Crossing the Delaware" offers a reflection on Shimomura's well-known revisionist painting and the cultural politics of morality, education, and history in U.S. schools.

Agora, Chicago, IL, digital photo, 2012.

There are many other wonderful poems in this collection. They range widely in geography, across the Americas and Asia. They touch on different topics, often examining the histories of things and places to shed light on contemporary circumstances and social relations. One section of poems focuses on animals, especially the control of them such as putting dogs down in shelters to control population ("Cull") or arranging them in museums as objects of knowledge ("Natural History").

Adapations, Iowa City, IA, digital photo, 2010.

I'd be remiss as a crazy dog person note to end with a few lines from "Working Dog, Do Not Pet," a thoughtful poem about the balance of domestication and wildness in dogs:

the cattle dogThis collection of poems is expansive in its reach and its observations. While most of the poems are short, lyric verses of just a page, they each and collectively sketch out perspectives of the world that are insightful, scratching below surface understandings and connecting complicated, hidden histories to physical, observable presences.

has no intimates

her duty is

to guard

to reach a hand

beyond the electric

safety fence might be

to have it bitten off

Order a copy from the wonderful Small Press Distribution.

Published on July 01, 2013 09:27

June 25, 2013

Asian American Literature Fans – Megapost for June 25, 2013

Asian American Literature Fans – Megapost for June 25, 2013

In this post, reviews of Nadeem Aslam’s The Blind Man’s Garden (Knopf, 2013), Oonya Kempadoo’s All Decent Animals (FSG, 2013), Alison Singh Gee’s Where the Peacocks Sing (St. Martin’s Press, 2003), Farhana Zia’s The Garden of my Imaan (Peachtree Publishers, 2013), Tao Lin’s Shoplifting from American Apparel (Melville House, 2009), Anis Shivani’s The Fifth Lash and Other Stories (C&R Press, 2012), Brenda Lin’s Wealth Ribbon: Taiwan Bound, America Bound (University of Indianapolis Press, 2004), Lavanya Sankaran’s The Hope Factory (The Dial Press, 2013).

A Review of Nadeem Aslam’s The Blind Man’s Garden (Knopf, 2013).

The Blind Man’s Garden is the kind of novel that makes you immediately wonder about the status of the creative writer as a researcher, historian, and ethnographer. The novel is set in Pakistan and Afghanistan and follows the lives of two sibling figures (Jeo and Mikal). Jeo is recently married, but decides to engage a humanitarian mission, offering his services as a medical doctor to those in war-torn Afghanistan. Jeo and Mikal are able to sneak into Afghanistan, but they are soon ambushed and separated. Jeo is killed, but Mikal’s fate is unknown. Back in Pakistan, Jeo’s wife, Naheed, is grieving, but it soon becomes apparent that she harbors a secret. Under pressure from her mother to remarry, Naheed actually remains steadfast in her belief that Mikal might still be alive. Indeed, Naheed had had a romance with him prior to marrying Jeo. Thus, in some ways, the novel turns into a love story amid a conflict-ridden and devastated landscape. In this sense, The Blind Man’s Garden evokes some of my favorite works to appear in the last couple of years, which include Tan Twan Eng’s The Garden of Evening Mists and Roma Tearne’s Mosquito. This novel is an incredibly ambitious work in that Aslam must balance different plot strands alongside providing readers—many of whom will not necessarily be familiar with the history and the culture of the Afghanistan and Pakistan—a sense of the social contexts in which all the characters are mired. Further still, the novel spotlights Aslam’s keen ability to pause a scene and dwell in the richness of description. In this sense, Aslam reveals that even the darkest fictional worlds possess some measure of beauty and hope. The novel is in some ways connected to the world of Aslam’s previous effort, The Wasted Vigil, as one character, David Town, returns. In this case, he is the interrogator assigned to extract information from Mikal. Though the novel occasionally flags as Aslam weaves must weave together the complexity offered by various historical, cultural, and aesthetic strands, The Blind Man’s Garden is an incredibly important work simply for its political considerations, gesturing to the continued and problematic nature of empire-building as it continues in the borderlands of the Middle East and South Asia. Certainly, this novel can be paired with a number of others recently published and reviewed here at Asian American Literature Fans such as Jamil Ahmad’s The Wandering Falcon and Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Blind-Mans-Garden-Nadeem-Aslam/dp/0307961710/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1370744841&sr=8-1&keywords=the+blind+man%27s+garden

A Review of Oonya Kempadoo’s All Decent Animals (FSG, 2013).

I’m been trying to break some bad habits and pick up some novels of writers who have been on my to-read list for much too long. Oonya Kempadoo’s first two novels have unfortunately been languishing on my bookshelves still (Tide Running and Buxton Spice), but her new novel gave me some extra motivation and I read it in a couple of sittings. Kempadoo, of mixed-background and who has lived in many areas of the world, creates a third novel that is at its core a kuntslerroman, a narrative concerning the development of the artist-figure. Our protagonist is Ata (short for Atalanta), an apt name insofar as Ata is a fiercely independent spirit, who follows her artistic beliefs far enough to the point where she attempts to make a career of it, especially as her work is connected to the festival of Carnival. The novel teems with a spatial register that is imbued with the vitality of a specific geographical setting—that of Trinidad. Ata is a graphic design and costume maker, who will later come to realize that her interests in creative production actually are far wider in scope. She engages in a love affair with man who is working for the French branch of the United Nations, a man by the name of Pierre, but as the narrative moves on, her close friend Fraser is diagnosed with end-stage AIDS. Thus, the novel shifts to the consideration of her life in the shadow of this man’s inevitable death. Kempadoo texturizes the narrative through temporal jumps and occasionally shifts the perspective to other characters and she employs a stream-of-consciousness technique that continually and dynamically refocuses the narrative. Kempadoo’s novel ultimately provides a fascinating lens into the lives of a core group of characters, especially as they collide with and are enmeshed in the social contexts of an island society attempting to keep pace with a global economy. The class stratification, the racial division and segregation, as well as artistic freedom, are all issues that strongly undergird the character trajectories and give weight and heft to Kempadoo’s third novel. Though the narrative does not always completely gel, Kempadoo’s artistic writing style makes the reading experience a luxurious one.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/All-Decent-Animals-Oonya-Kempadoo/dp/0374299714/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1371597163&sr=1-1&keywords=all+decent+animals

A Review of Alison Singh Gee’s Where the Peacocks Sing (St. Martin’s Press, 2003).

I was probably not in the right frame of mind to read Alison Singh Gee’s Where the Peacocks Sing, a memoir about the author’s exploration of her identity as well as her romantic relationship with an South Asian man named Ajay. The memoir begins with Gee’s consideration of her early career in journalism, where she is stationed in Hong Kong. This job gives her the opportunity to meet globally recognizable movie stars such as Jackie Chan and Gong Li and enables her to go out practically every night of the week. As a kind of celebrity nexus point, Gee is swept up in the social fervor and lives the high life, dating an affluent man, while rocking all the latest red carpet looks. But, there was something missing in Gee’s life, an aspect that did not become readily apparent until she began a correspondence with another journalist by the name of Ajay. As their relationship becomes more serious, Gee essentially shifts her life priorities, willing to give up her fast-paced life and consider what it would mean to be fully engaged in a romance with a South Asian man who attaches significant importance to his family roots. These family roots include a Palace located in India, which is in some state of disrepair. Gee gamely embarks on a quest to fully embrace the ethnic and provincial roots of her soon-to-be husband, which includes a trip to Mokimpur, but all is not immediately well. Gee struggles to fit in and to find a sense of kinship among Ajay’s closest relatives. Over time, though, Gee begins to acclimate to Ajay’s understanding of both India and his family and by the memoir’s conclusion, she sees that his family has become really an extended part of her own. When I started out the review by stating that I was probably not in the right frame of mind, I mean to say that reviews are necessarily influenced by our own personal states and I was sort of in a bad mood. Fortunately, Gee has an enterprising spirit and this style is fortunately infectious. Where the Peacocks Sing is written to imbue the reader with a sense of rebirth and hope and by the conclusion, I did indeed feel better. In terms of this community, Gee, who hails from a Chinese American background does reveal to us the difference between an ethnoracial U.S-based identity and a South Asian transnational one (through Ajay) and I believe that this memoir would make quite an interesting textual selection in terms of thinking about panethnicity as a paradigm for understanding Asian American racial formation. Undoubtedly, the text also speaks to the growing thematic of multiracial and multiethnic families in American literature.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Where-Peacocks-Sing-Palace-Prince/dp/0312378785/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366912817&sr=8-1&keywords=Alison+Singh+Gee

A Review of Farhana Zia’s The Garden of my Imaan (Peachtree Publishers, 2013).

So I’ve been in a bit of a work funk lately and have been escaping into books here and there. Farhana Zia’s The Garden of my Imaan has been sitting on my “to read” bookshelf, so I finally picked it up! Zia’s debut novel is told from the first person perspective of a fifth grader named Aliya, who happens to be Muslim and South Asian American (of Indian ancestry). The novel is targeted toward advanced elementary and middle-school aged children and its focus is to articulate the challenges of growing up as a religious minority. Indeed, Aliya struggles to balance the universal issues of schooling such as belonging and popularity with particular cultural values such as religious dress and customs. As part of a school project, she starts to write to Allah, as a way to convey conundrums that surface during her daily life. For instance, she finds it difficult to maintain her fasting during Ramadan. Further still, she seeks gain the kind of courage she sees in a new classmate from Morocco named Marwa who is absolutely unapologetic and fearless about her Muslim faith. Fortunately, Aliya has some good friends and reliable family members who keep her grounded and more confident. As with some of the youth-oriented fictions I’ve read, Zia’s aim is undoubtedly to shed like on cultural and religious traditions and communities that have been targeted in light of the heightened animosity that emerged after 9/11. Though the narrative itself is not necessarily the most dynamic or original, Zia’s political rhetoric is unequivocally admirable.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Garden-My-Imaan-Farhana-Zia/dp/1561456985/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1368997164&sr=8-1&keywords=Farhana+Zia

A Review of Tao Lin’s Shoplifting from American Apparel (Melville House, 2009).

It’s been awhile since I’ve read anything by Tao Lin. There’s a certain style that Lin has mastered that borders on the absurd and you can never quite figure out where a particular narrative will go. In Lin’s Shoplifting from American Apparel, a novella of sorts, our protagonist is Sam, a young Taiwanese American writer who moves through a series of relationships and is repeatedly arrested for shoplifting (hence the title). It would be hard to describe a specific plot beyond this statement, except to say that Lin’s novella also operates to document the ubiquity of social media, brand names, and other such ephemera in the contemporary moment (references to youtube, gchat, flickr, photobucket, myspace, Odwalla juice and Moby abound). Though Sam might seem to be a peculiar character, his ennui is mirrored by the many characters who crop up in his life, and the meandering narrative is more largely reflective of the meandering psychic space that is being represented. A representative passage perhaps can be found here: “A few days later he and Sheila were on a train to New York City. They drank from a large plastic bottle containing organic soymilk, energy drink, and green tea extract and wrote sex stories to sell to nerve.com for $500. Sheila’s sex story had chainsaws and Sam’s sex story had Ha Jin doing things in a bathroom at Emory University. Sheila said she felt excited to be in New York City soon. They talked about making their own energy drink company. They got off the train and stood [end of 12] waiting for another train. They climbed a wall and sat in sunlight facing the train tracks” (13). I obviously enjoy this passage for Lin’s irreverent nod to Asian American culture in his reference to Ha Jin, but if we want to take this work seriously for a moment, we can place it perhaps in the mode of the twentysomething-identity quest to be found in a time where humanistic inquiry and the creative life can seem to be superfluous. What meaning can such endeavors hold amongst the preponderance and speed of the internet culture, so while we think on this issue, we might as well pilfer a thing or two.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Shoplifting-American-Apparel-Contemporary-Novella/dp/1933633786/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1367445468&sr=8-1&keywords=shoplifting+from+american+apparel

A Review of Anis Shivani’s The Fifth Lash and Other Stories (C&R Press, 2012)

When I saw that Anis Shivani had put out another collection, I was curious to see how it would stack up against Anatolia and Other Stories, which was one of the most surprising reads for me in the last five years. The Fifth Lash and Other Stories is far more thematically unified in terms of an explicit connecting arc, as Shivani’s various stories involve characters typically of South Asian and/or Muslim backgrounds. But from there, Shivani showcases his storytelling versatility through narrative perspective, historical and geographical context and tonality. I’ll briefly focus on a handful to illustrate. The title story takes the narrative perspective of a close and former political advisor to Bhutto and the regime changes that occur in the Pakistani political realm. Here, Shivani’s story takes flight amid the behind-the-scenes drama as well as the shifting alliances that have made Pakistani politics one of the most turbulent in the recent decades. Both “Growing up Blind, in a Hotly Contested State” and “The House on Bahadur Shah Zafar Road” take on the topic of extramarital problematics. In the former story, a U.S.-based academic focused on Middle Eastern politics must come to the realization that his very low-key relationship with his wife is not the result of some common understanding, but a deliberate distancing on her part so that she can engage in an affair. The latter explores the “open secret” of a household servant named Zainab, who is fired due to the fact of indecorous state as an unmarried, pregnant woman. But her dismissal covers up the central issue: her pregnancy is likely the result of a long going affair with one of the family members. In “Alienation, Jihad, Burqa, Apostasy,” the transnational narrator comes full circle, first completely detaching himself from his Pakistani origin and later taking a prominent role in campus politics and reclaiming the importance of his heritage, only to question this shift in his priorities by the story’s end. And my favorite story, “Censor,” takes a fragmented and satirical look at the ways in which laws of propriety—even as outdated and outmoded as they can be—remain central to the regulation of South Asian culture. An eclectic collection full of darkly comic circumstances and complicated narrative perspectives.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Fifth-Lash-Other-Stories/dp/1936196042/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8&qid=1366691350&sr=8-4&keywords=anis+shivani

A Review of Brenda Lin’s Wealth Ribbon: Taiwan Bound, America Bound (University of Indianapolis Press, 2004).

I am reviewing Wealth Ribbon: Taiwan Bound, America Bound, which was already reviewed here by pylduck sometime ago.

http://asianamlitfans.livejournal.com/120496.html?nojs=1&mode=reply

I was encouraged to pick up this title because I’ve actually become part of an impromptu reading group concerning Taiwanese/ American culture and representation. It’s part of an ongoing effort related to the fact that a member of my family wants to get to know more about her heritage, so I’ve been involved in picking out the books and coming up with some questions for each meeting. One of our first book picks is Wealth Ribbon, which is a wonderful creative non-fiction concerning the complications of identity in a very transnational age. Lin would be the quintessential “flexible citizen,” defined by Aihwa Ong in her already classic book, as Lin grows up both in the United States and Taiwan. Her parents are part of a generation that was unsure whether or not Taiwan would survive and so they casted multiple nets of national affiliations, raising Lin as a young child in the U.S. Even when Lin later moves to Taiwan, she is enrolled in an American school, thereby ensuring a continued bilingual upbringing. She will later return to the United States, embark in an interracial relationship with a man named Billy, and then later return to Taiwan with Billy, with all the complications that come with traveling as an as-yet unmarried young woman. This memoir is particularly noteworthy for Lin’s ability to deftly weave together historical elements with a personal account of her family. There is a very strong matrilineal impulse to Lin’s work that makes this memoir one that could be easily paired alongside something like Kingston’s The Woman Warrior, Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, or Ng’s Bone.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Wealth-Ribbon-Taiwan-Bound-America/dp/0880938544/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1370299703&sr=8-1&keywords=brenda+lin+wealth+ribbon

A Review of Lavanya Sankaran’s The Hope Factory (The Dial Press, 2013)

Lavanya Sankaran’s debut novel The Hope Factory (The Dial Press, 2013) follows in the tradition of other South Asian writers seeking to explore the complicated nature of national modernization, especially as it relates to class collisions; the novel is reminiscent of Bharati Mukherjee’s Miss New India and Aravind Adiga’s Last Man in Tower in this regard. Sankaran is also author of the short story collection, The Red Carpet, which pylduck earlier reviewed here:

http://asianamlitfans.livejournal.com/133756.html

As with The Red Carpet, the majority of this story is set in Bangalore and mainly follows the perspective of two major characters: Anand and Kamala. Anand comes from the upper class, is a factory magnate, and is looking to expand his business. This process requires him to ask favors of various folks, who might be able to get him the land he needs. Anand is “married with children” and seems to be the picture of modern Indian success, but of course, Sankaran wants to complicate this characterization and we begin to see that there are cracks in his marriage and his kinship relationships that will challenge his own vision for economic growth. Then, there is Kamala, who exists on the other side of the class equation. Fortunately hired to work in Ananda’s house, Kamala is a fiercely independent woman who is seeking to keep her life in balance and especially looking to finance a better education for her gifted, but troubled young son Narayan. Sankaran’s novel exposes the incredibly wide gulf between the classes and the perilous challenges that they must face. When Sankaran finally places the two major characters in a more coherent plot trajectory, we begin to see how one life can be leveraged against another. Sankaran’s work appears most luminous in its critique of global capitalism, which reduces land and the lives who reside there to mere parcels of space to be reconfigured for profit.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Hope-Factory-A-Novel/dp/0385338198/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1368804142&sr=8-1&keywords=the+hope+factory

In this post, reviews of Nadeem Aslam’s The Blind Man’s Garden (Knopf, 2013), Oonya Kempadoo’s All Decent Animals (FSG, 2013), Alison Singh Gee’s Where the Peacocks Sing (St. Martin’s Press, 2003), Farhana Zia’s The Garden of my Imaan (Peachtree Publishers, 2013), Tao Lin’s Shoplifting from American Apparel (Melville House, 2009), Anis Shivani’s The Fifth Lash and Other Stories (C&R Press, 2012), Brenda Lin’s Wealth Ribbon: Taiwan Bound, America Bound (University of Indianapolis Press, 2004), Lavanya Sankaran’s The Hope Factory (The Dial Press, 2013).

A Review of Nadeem Aslam’s The Blind Man’s Garden (Knopf, 2013).

The Blind Man’s Garden is the kind of novel that makes you immediately wonder about the status of the creative writer as a researcher, historian, and ethnographer. The novel is set in Pakistan and Afghanistan and follows the lives of two sibling figures (Jeo and Mikal). Jeo is recently married, but decides to engage a humanitarian mission, offering his services as a medical doctor to those in war-torn Afghanistan. Jeo and Mikal are able to sneak into Afghanistan, but they are soon ambushed and separated. Jeo is killed, but Mikal’s fate is unknown. Back in Pakistan, Jeo’s wife, Naheed, is grieving, but it soon becomes apparent that she harbors a secret. Under pressure from her mother to remarry, Naheed actually remains steadfast in her belief that Mikal might still be alive. Indeed, Naheed had had a romance with him prior to marrying Jeo. Thus, in some ways, the novel turns into a love story amid a conflict-ridden and devastated landscape. In this sense, The Blind Man’s Garden evokes some of my favorite works to appear in the last couple of years, which include Tan Twan Eng’s The Garden of Evening Mists and Roma Tearne’s Mosquito. This novel is an incredibly ambitious work in that Aslam must balance different plot strands alongside providing readers—many of whom will not necessarily be familiar with the history and the culture of the Afghanistan and Pakistan—a sense of the social contexts in which all the characters are mired. Further still, the novel spotlights Aslam’s keen ability to pause a scene and dwell in the richness of description. In this sense, Aslam reveals that even the darkest fictional worlds possess some measure of beauty and hope. The novel is in some ways connected to the world of Aslam’s previous effort, The Wasted Vigil, as one character, David Town, returns. In this case, he is the interrogator assigned to extract information from Mikal. Though the novel occasionally flags as Aslam weaves must weave together the complexity offered by various historical, cultural, and aesthetic strands, The Blind Man’s Garden is an incredibly important work simply for its political considerations, gesturing to the continued and problematic nature of empire-building as it continues in the borderlands of the Middle East and South Asia. Certainly, this novel can be paired with a number of others recently published and reviewed here at Asian American Literature Fans such as Jamil Ahmad’s The Wandering Falcon and Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Blind-Mans-Garden-Nadeem-Aslam/dp/0307961710/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1370744841&sr=8-1&keywords=the+blind+man%27s+garden

A Review of Oonya Kempadoo’s All Decent Animals (FSG, 2013).

I’m been trying to break some bad habits and pick up some novels of writers who have been on my to-read list for much too long. Oonya Kempadoo’s first two novels have unfortunately been languishing on my bookshelves still (Tide Running and Buxton Spice), but her new novel gave me some extra motivation and I read it in a couple of sittings. Kempadoo, of mixed-background and who has lived in many areas of the world, creates a third novel that is at its core a kuntslerroman, a narrative concerning the development of the artist-figure. Our protagonist is Ata (short for Atalanta), an apt name insofar as Ata is a fiercely independent spirit, who follows her artistic beliefs far enough to the point where she attempts to make a career of it, especially as her work is connected to the festival of Carnival. The novel teems with a spatial register that is imbued with the vitality of a specific geographical setting—that of Trinidad. Ata is a graphic design and costume maker, who will later come to realize that her interests in creative production actually are far wider in scope. She engages in a love affair with man who is working for the French branch of the United Nations, a man by the name of Pierre, but as the narrative moves on, her close friend Fraser is diagnosed with end-stage AIDS. Thus, the novel shifts to the consideration of her life in the shadow of this man’s inevitable death. Kempadoo texturizes the narrative through temporal jumps and occasionally shifts the perspective to other characters and she employs a stream-of-consciousness technique that continually and dynamically refocuses the narrative. Kempadoo’s novel ultimately provides a fascinating lens into the lives of a core group of characters, especially as they collide with and are enmeshed in the social contexts of an island society attempting to keep pace with a global economy. The class stratification, the racial division and segregation, as well as artistic freedom, are all issues that strongly undergird the character trajectories and give weight and heft to Kempadoo’s third novel. Though the narrative does not always completely gel, Kempadoo’s artistic writing style makes the reading experience a luxurious one.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/All-Decent-Animals-Oonya-Kempadoo/dp/0374299714/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1371597163&sr=1-1&keywords=all+decent+animals

A Review of Alison Singh Gee’s Where the Peacocks Sing (St. Martin’s Press, 2003).

I was probably not in the right frame of mind to read Alison Singh Gee’s Where the Peacocks Sing, a memoir about the author’s exploration of her identity as well as her romantic relationship with an South Asian man named Ajay. The memoir begins with Gee’s consideration of her early career in journalism, where she is stationed in Hong Kong. This job gives her the opportunity to meet globally recognizable movie stars such as Jackie Chan and Gong Li and enables her to go out practically every night of the week. As a kind of celebrity nexus point, Gee is swept up in the social fervor and lives the high life, dating an affluent man, while rocking all the latest red carpet looks. But, there was something missing in Gee’s life, an aspect that did not become readily apparent until she began a correspondence with another journalist by the name of Ajay. As their relationship becomes more serious, Gee essentially shifts her life priorities, willing to give up her fast-paced life and consider what it would mean to be fully engaged in a romance with a South Asian man who attaches significant importance to his family roots. These family roots include a Palace located in India, which is in some state of disrepair. Gee gamely embarks on a quest to fully embrace the ethnic and provincial roots of her soon-to-be husband, which includes a trip to Mokimpur, but all is not immediately well. Gee struggles to fit in and to find a sense of kinship among Ajay’s closest relatives. Over time, though, Gee begins to acclimate to Ajay’s understanding of both India and his family and by the memoir’s conclusion, she sees that his family has become really an extended part of her own. When I started out the review by stating that I was probably not in the right frame of mind, I mean to say that reviews are necessarily influenced by our own personal states and I was sort of in a bad mood. Fortunately, Gee has an enterprising spirit and this style is fortunately infectious. Where the Peacocks Sing is written to imbue the reader with a sense of rebirth and hope and by the conclusion, I did indeed feel better. In terms of this community, Gee, who hails from a Chinese American background does reveal to us the difference between an ethnoracial U.S-based identity and a South Asian transnational one (through Ajay) and I believe that this memoir would make quite an interesting textual selection in terms of thinking about panethnicity as a paradigm for understanding Asian American racial formation. Undoubtedly, the text also speaks to the growing thematic of multiracial and multiethnic families in American literature.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Where-Peacocks-Sing-Palace-Prince/dp/0312378785/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366912817&sr=8-1&keywords=Alison+Singh+Gee

A Review of Farhana Zia’s The Garden of my Imaan (Peachtree Publishers, 2013).

So I’ve been in a bit of a work funk lately and have been escaping into books here and there. Farhana Zia’s The Garden of my Imaan has been sitting on my “to read” bookshelf, so I finally picked it up! Zia’s debut novel is told from the first person perspective of a fifth grader named Aliya, who happens to be Muslim and South Asian American (of Indian ancestry). The novel is targeted toward advanced elementary and middle-school aged children and its focus is to articulate the challenges of growing up as a religious minority. Indeed, Aliya struggles to balance the universal issues of schooling such as belonging and popularity with particular cultural values such as religious dress and customs. As part of a school project, she starts to write to Allah, as a way to convey conundrums that surface during her daily life. For instance, she finds it difficult to maintain her fasting during Ramadan. Further still, she seeks gain the kind of courage she sees in a new classmate from Morocco named Marwa who is absolutely unapologetic and fearless about her Muslim faith. Fortunately, Aliya has some good friends and reliable family members who keep her grounded and more confident. As with some of the youth-oriented fictions I’ve read, Zia’s aim is undoubtedly to shed like on cultural and religious traditions and communities that have been targeted in light of the heightened animosity that emerged after 9/11. Though the narrative itself is not necessarily the most dynamic or original, Zia’s political rhetoric is unequivocally admirable.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Garden-My-Imaan-Farhana-Zia/dp/1561456985/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1368997164&sr=8-1&keywords=Farhana+Zia

A Review of Tao Lin’s Shoplifting from American Apparel (Melville House, 2009).

It’s been awhile since I’ve read anything by Tao Lin. There’s a certain style that Lin has mastered that borders on the absurd and you can never quite figure out where a particular narrative will go. In Lin’s Shoplifting from American Apparel, a novella of sorts, our protagonist is Sam, a young Taiwanese American writer who moves through a series of relationships and is repeatedly arrested for shoplifting (hence the title). It would be hard to describe a specific plot beyond this statement, except to say that Lin’s novella also operates to document the ubiquity of social media, brand names, and other such ephemera in the contemporary moment (references to youtube, gchat, flickr, photobucket, myspace, Odwalla juice and Moby abound). Though Sam might seem to be a peculiar character, his ennui is mirrored by the many characters who crop up in his life, and the meandering narrative is more largely reflective of the meandering psychic space that is being represented. A representative passage perhaps can be found here: “A few days later he and Sheila were on a train to New York City. They drank from a large plastic bottle containing organic soymilk, energy drink, and green tea extract and wrote sex stories to sell to nerve.com for $500. Sheila’s sex story had chainsaws and Sam’s sex story had Ha Jin doing things in a bathroom at Emory University. Sheila said she felt excited to be in New York City soon. They talked about making their own energy drink company. They got off the train and stood [end of 12] waiting for another train. They climbed a wall and sat in sunlight facing the train tracks” (13). I obviously enjoy this passage for Lin’s irreverent nod to Asian American culture in his reference to Ha Jin, but if we want to take this work seriously for a moment, we can place it perhaps in the mode of the twentysomething-identity quest to be found in a time where humanistic inquiry and the creative life can seem to be superfluous. What meaning can such endeavors hold amongst the preponderance and speed of the internet culture, so while we think on this issue, we might as well pilfer a thing or two.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Shoplifting-American-Apparel-Contemporary-Novella/dp/1933633786/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1367445468&sr=8-1&keywords=shoplifting+from+american+apparel

A Review of Anis Shivani’s The Fifth Lash and Other Stories (C&R Press, 2012)

When I saw that Anis Shivani had put out another collection, I was curious to see how it would stack up against Anatolia and Other Stories, which was one of the most surprising reads for me in the last five years. The Fifth Lash and Other Stories is far more thematically unified in terms of an explicit connecting arc, as Shivani’s various stories involve characters typically of South Asian and/or Muslim backgrounds. But from there, Shivani showcases his storytelling versatility through narrative perspective, historical and geographical context and tonality. I’ll briefly focus on a handful to illustrate. The title story takes the narrative perspective of a close and former political advisor to Bhutto and the regime changes that occur in the Pakistani political realm. Here, Shivani’s story takes flight amid the behind-the-scenes drama as well as the shifting alliances that have made Pakistani politics one of the most turbulent in the recent decades. Both “Growing up Blind, in a Hotly Contested State” and “The House on Bahadur Shah Zafar Road” take on the topic of extramarital problematics. In the former story, a U.S.-based academic focused on Middle Eastern politics must come to the realization that his very low-key relationship with his wife is not the result of some common understanding, but a deliberate distancing on her part so that she can engage in an affair. The latter explores the “open secret” of a household servant named Zainab, who is fired due to the fact of indecorous state as an unmarried, pregnant woman. But her dismissal covers up the central issue: her pregnancy is likely the result of a long going affair with one of the family members. In “Alienation, Jihad, Burqa, Apostasy,” the transnational narrator comes full circle, first completely detaching himself from his Pakistani origin and later taking a prominent role in campus politics and reclaiming the importance of his heritage, only to question this shift in his priorities by the story’s end. And my favorite story, “Censor,” takes a fragmented and satirical look at the ways in which laws of propriety—even as outdated and outmoded as they can be—remain central to the regulation of South Asian culture. An eclectic collection full of darkly comic circumstances and complicated narrative perspectives.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Fifth-Lash-Other-Stories/dp/1936196042/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8&qid=1366691350&sr=8-4&keywords=anis+shivani

A Review of Brenda Lin’s Wealth Ribbon: Taiwan Bound, America Bound (University of Indianapolis Press, 2004).

I am reviewing Wealth Ribbon: Taiwan Bound, America Bound, which was already reviewed here by pylduck sometime ago.

http://asianamlitfans.livejournal.com/120496.html?nojs=1&mode=reply

I was encouraged to pick up this title because I’ve actually become part of an impromptu reading group concerning Taiwanese/ American culture and representation. It’s part of an ongoing effort related to the fact that a member of my family wants to get to know more about her heritage, so I’ve been involved in picking out the books and coming up with some questions for each meeting. One of our first book picks is Wealth Ribbon, which is a wonderful creative non-fiction concerning the complications of identity in a very transnational age. Lin would be the quintessential “flexible citizen,” defined by Aihwa Ong in her already classic book, as Lin grows up both in the United States and Taiwan. Her parents are part of a generation that was unsure whether or not Taiwan would survive and so they casted multiple nets of national affiliations, raising Lin as a young child in the U.S. Even when Lin later moves to Taiwan, she is enrolled in an American school, thereby ensuring a continued bilingual upbringing. She will later return to the United States, embark in an interracial relationship with a man named Billy, and then later return to Taiwan with Billy, with all the complications that come with traveling as an as-yet unmarried young woman. This memoir is particularly noteworthy for Lin’s ability to deftly weave together historical elements with a personal account of her family. There is a very strong matrilineal impulse to Lin’s work that makes this memoir one that could be easily paired alongside something like Kingston’s The Woman Warrior, Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, or Ng’s Bone.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Wealth-Ribbon-Taiwan-Bound-America/dp/0880938544/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1370299703&sr=8-1&keywords=brenda+lin+wealth+ribbon

A Review of Lavanya Sankaran’s The Hope Factory (The Dial Press, 2013)

Lavanya Sankaran’s debut novel The Hope Factory (The Dial Press, 2013) follows in the tradition of other South Asian writers seeking to explore the complicated nature of national modernization, especially as it relates to class collisions; the novel is reminiscent of Bharati Mukherjee’s Miss New India and Aravind Adiga’s Last Man in Tower in this regard. Sankaran is also author of the short story collection, The Red Carpet, which pylduck earlier reviewed here:

http://asianamlitfans.livejournal.com/133756.html

As with The Red Carpet, the majority of this story is set in Bangalore and mainly follows the perspective of two major characters: Anand and Kamala. Anand comes from the upper class, is a factory magnate, and is looking to expand his business. This process requires him to ask favors of various folks, who might be able to get him the land he needs. Anand is “married with children” and seems to be the picture of modern Indian success, but of course, Sankaran wants to complicate this characterization and we begin to see that there are cracks in his marriage and his kinship relationships that will challenge his own vision for economic growth. Then, there is Kamala, who exists on the other side of the class equation. Fortunately hired to work in Ananda’s house, Kamala is a fiercely independent woman who is seeking to keep her life in balance and especially looking to finance a better education for her gifted, but troubled young son Narayan. Sankaran’s novel exposes the incredibly wide gulf between the classes and the perilous challenges that they must face. When Sankaran finally places the two major characters in a more coherent plot trajectory, we begin to see how one life can be leveraged against another. Sankaran’s work appears most luminous in its critique of global capitalism, which reduces land and the lives who reside there to mere parcels of space to be reconfigured for profit.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Hope-Factory-A-Novel/dp/0385338198/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1368804142&sr=8-1&keywords=the+hope+factory

Published on June 25, 2013 18:01

June 14, 2013

Adaptation ARCs Giveaway!

Malinda Lo is running a fun promotional giveaway of three advance reading copies of her forthcoming novel Inheritance (sequel to Adaptation, reviewed on this site last fall by stephenhongsohn).

Published on June 14, 2013 12:06

June 9, 2013

Ruth Ozeki is Awesome Blossom!!!

I'm a little late to the game, but Ruth Ozeki is now one of my very favorite writers. If you haven't read her first two novels, My Year of Meats (Penguin 1998) and All Over Creation (Penguin 2003),

run out right now & get them

! I’m in the middle of her latest, A Tale for the Time Being (Viking 2013), which is also excellent. All three novels are quite different yet share thematic threads and concerns – food, the environment, and how we’re messing them and ourselves up very badly; fecundity and procreation; Buddhism and peace; and relations between people, particularly how geographical and physical proximity don’t necessary equal intimacy and identification, and vice versa. In other words, sometimes the people nearest to us are strangers, and sometimes we identify and connect with strangers half a world away.

I'm a little late to the game, but Ruth Ozeki is now one of my very favorite writers. If you haven't read her first two novels, My Year of Meats (Penguin 1998) and All Over Creation (Penguin 2003),

run out right now & get them

! I’m in the middle of her latest, A Tale for the Time Being (Viking 2013), which is also excellent. All three novels are quite different yet share thematic threads and concerns – food, the environment, and how we’re messing them and ourselves up very badly; fecundity and procreation; Buddhism and peace; and relations between people, particularly how geographical and physical proximity don’t necessary equal intimacy and identification, and vice versa. In other words, sometimes the people nearest to us are strangers, and sometimes we identify and connect with strangers half a world away.My Year of Meats follows the lives of Jane Takagi-Little, a mixed-race documentary filmmaker in the U.S., and Akiko Ueno, an abused housewife in Japan. Jane is shooting a documentary series titled My American Wife!, sponsored by the American “Beef Export and Trade Syndicate, or, simply, BEEF-EX” (9). The purpose of the show is to bring the “heartland of America into the homes of Japan,” and in the process sell beef to the Japanese; i.e. “Meat is the Message.” In the process, Jane clashes with her Japanese boss, Joichi “John” Ueno, who objects to her featuring families with adopted children, African Americans, working-class people, and – horror of horrors – a lesbian, vegetarian couple. And Jane learns about the horrific effects of synthetic hormones and other chemicals, which affect both animals and humans very badly for generations, as well as the inhumane conditions of producing meat (suffice it to say that I’m off meat for a while). Meanwhile, Akiko cannot get pregnant or keep food down (the two being related), but does appreciate the better of Jane’s shows. Things go extremely downhill for both Jane and Akiko, but I won't spoil it; this intro synopsis doesn’t do justice to the subtlety, complexity, and surprisingness of the novel.

All Over Creation is set in Idaho, potato country, and it’s all about generation, both in sense of families as well as of creation. Yumi Fuller returns with her three children (different fathers) to Liberty Falls, where her Japanese mother is suffering from dementia and her white father is dying of cancer. It’s the first time she’s returned since she was 15, when she ran away after an affair with a teacher (not good). Her neighbor and former best friend, Cass Quinn, is now married and a potato farmer, and she has been trying unsuccessfully to conceive. Amidst the awkward family reunion, the Seeds of Resistance, a group of environmental activists protesting genetic engineering in crops, show up. Trust me, it’s not as crazy as it sounds; Ozeki is always subtle, fair, gentle, believable. And she makes potatoes and the politics of genetic modification fascinating.

Despite their topics, neither novel is ever preachy or didactic. A large part of this, I think, comes from Ozeki’s sure touch with characters – everyone is as complex and as part-good/part-bad as real people are. Not that realism is a requisite for good writing, but Ozeki is just really good at capturing how well meaning yet messed up most of us are.

A Tale for the Time Being is more formally experimental than the previous two novels, but they also tie together characters from far corners and explore how our degradation of the environment also degrades us. It was previously reviewed by obongo on March 12, 2013.

Buy Ozeki's books here: http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=sr_nr_p_lbr_one_browse-bin_0?rh=n%3A283155%2Ck%3Aruth+ozeki%2Cp_lbr_one_browse-bin%3ARuth+L.+Ozeki&keywords=ruth+ozeki&ie=UTF8&qid=1370786553&rnid=2272759011

Published on June 09, 2013 07:03

May 31, 2013

Asian American Literature Fans Megapost for May 31 2013

Asian American Literature Fans Megapost for May 31 2013

In this post, reviews of: Gish Jen’s Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self (Harvard University Press, 2013); Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority: Asian American Literature and Everyday Life (Oxford University Press, 2013); A Review of Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs (University of Hawaii Press, 2011); Tosca Lee’s Demon: A Memoir (B&H Books, 2010); Andrew Fukuda’s The Prey (St. Martin’s Press, 2013); Susan Kim and Laurence Klavan’s Wasteland (HarperTeen 2013); Eddie Huang’s Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir (Spiegel and Grau, 2013); Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Oleander Girl (Simon & Schuster, 2013).

A Review of Gish Jen’s Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self (Harvard University Press, 2013).

Gish Jen was selected to be guest lecturer of the distinguished Massey lectures in 2012; the product of this lectureship is Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self. This lecture series once also invited Maxine Hong Kingston and her work, To be the Poet (2000), resulted from that period. It is always a treat to read about a writer’s level of thinking that goes into the creative process. Of course, Jen and her marketers wisely chose a controversial title, bringing to mind the already infamous book, The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, by Amy Chua. Frankly, Jen’s lectures have actually very little to do with Asian parenting per se, but more closely track a rough differentiation in Eastern and Western modes of thinking and of creative production. Jen distinguishes between an independent—more Western—thinking and an interdependent—more Eastern—thinking; I use the word “more” quite deliberately, as Jen herself acknowledges the murkiness and the essentialization she must engage in order to conceive of this general binary. The point of Jen’s lectures seems to be an articulation of a kind of hybridity that she herself explores in her cultural productions; certainly there is the importance of the figure, or the character, but equally so is the context or the great frame of social relations in which the character finds herself enmeshed and often entangled. Jen is not out to say one mode is better or more enlightened than the other, but this sort of meditation is also an opportunity to get a better sense of her own trajectory as a writer, how she relates to her parents, and how even her parents might relate to their ancestors. The first lecture spends a great deal of time exploring Jen’s father’s life and his way of speaking about himself, which is ultimately a way of speaking around himself. By the last of the three lectures, Jen firmly roots her exploration of independence and interdependence from interpretations of her own fiction. It is an absolute treat to see this kind of exploration here and it makes me crave more of these kinds of publications—where writers are given an opportunity to explain some of the intentionality in their work and to engage in cultural analysis.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Tiger-Writing-Interdependent-Lectures-Civilization/dp/0674072839/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1363915326&sr=8-1&keywords=tiger+writing

A Review of Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority: Asian American Literature and Everyday Life (Oxford University Press, 2013); A Review of Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs (University of Hawaii Press, 2011)

There is certainly a risk in writing a book on the everyday, given its potential association with the banal, and yet Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority focuses on that very subject in her enterprising study of Asian American literature in relation what we might call “all things quotidian.” For those engaged in Asian American cultural studies, Lee’s archive is certainly not new or novel. In this respect, we might even call her selections part of the “everyday” of Asian Americanist critique, with chapters focused on Carlos Bulosan and Younghill Kang (chapter 1), Mine Okubo and Hisaye Yamamoto (chapter 2), Jade Snow Wong and Maxine Hong Kingston (chapter 3), Joy Kogawa, Nora Okja Keller, Ha Jin, and Lan Samantha Chang (chapter 4), Chang-rae Lee (chapter 5), and Frank Chin and Lois-Ann Yamanaka (chapter 6). At the same time, Lee’s approach shows the dynamic nature of common practices, familial object and experiences, revealing how Asian Americans have a necessarily vexed relationship to the everyday, in part mediated by the complicated nature and contours of racial formation. In this way, Lee helps us to rethink these canonical works and provides innovative readings in the process. Readings of the everyday within Asian American literature consequently makes for a lush and transformative scholarly study. My personal favorite chapter is the second, which focuses on the “uncanny” nature of the Japanese American internment experience in relation to the ways that internees attempted to reconstruct familiar environments even within the confines of what was a form of a prison. Thus, the familiar becomes slightly off-kilter, out of focus, and finally uncanny, as it becomes increasingly evident that the everyday cannot seamlessly be replicated in such inhospitable environments as the ones depicted in the aforementioned Okubo and Yamamoto. If there is a limit to Lee’s work, it is one common to most monographs: there simply is not enough time or space to cover all the possible works one might or possibly could. Indeed, her very short reading of Lahiri’s fiction in the conclusion makes us thirst for more.

The “racial formalism” phase of Asian American cultural critique continues with Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs, which forms a sort of second volume and companion to her earlier book, Begin Here: Reading Asian North American Autobiographies of Childhood. The shift from autobiography to memoir is deliberate precisely because, as Davis reveals, the memoirs she reads employ a collective standpoint (rather than the autobiographical self) of the family to deploy the narrative involved in life-writing. Of course, as with so many texts rooted in Asian ethnic contexts, these family stories are consistently a way to convey a larger tapestry. Davis contends: “The relational model of auto/biographical identity, I argue, functions on two levels in family memoirs: first, within the tet itself, as the author draws upon the stories of family members to complete her own, and, second, because these texts very consciously interpellate an audience. Asian American family memoirs manifestly present the individual author’s self as discursively constituted, as issues of literary traditions, immigrant history, identity politics, and cultural contingencies participate in the construction of the text” (11). As with Begin Here and Davis’s other book on the short story cycle, her knowledge of a given subfield is far-reading and visionary. She is one of the literary critics I can always go to get recommendations on books I have not even heard of and to expand the archive known more broadly as Asian American literature and culture. Indeed, most of the works she explores have not been reviewed here on Asian American literature fans and further still, most have not received much critical or literary attention elsewhere; these primary texts include: Jael Silliman’s Jewish Portraits, Indian Frames, Bruce Edward Hall’s Tea that Burns, and Mira Kamdar’s Motiba’s Tattoos. As with many other books in cultural criticism, Davis’s monograph remains in the hardcover form, but that should not deter anyone from requesting the title be added to a local university library.

Buy the Books Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Modern-Minority-American-Literature-Everyday/dp/0199915830/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1362341383&sr=8-1&keywords=modern+minority

http://www.amazon.com/Relative-Histories-Mediating-History-American/dp/0824834585/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1370056063&sr=8-1&keywords=relative+histories+rocio+davis

A Review of Tosca Lee’s Demon: A Memoir (B&H Books, 2010).

[image error]