Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 58

May 31, 2013

Asian American Literature Fans Megapost for May 31 2013

Asian American Literature Fans Megapost for May 31 2013

In this post, reviews of: Gish Jen’s Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self (Harvard University Press, 2013); Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority: Asian American Literature and Everyday Life (Oxford University Press, 2013); A Review of Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs (University of Hawaii Press, 2011); Tosca Lee’s Demon: A Memoir (B&H Books, 2010); Andrew Fukuda’s The Prey (St. Martin’s Press, 2013); Susan Kim and Laurence Klavan’s Wasteland (HarperTeen 2013); Eddie Huang’s Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir (Spiegel and Grau, 2013); Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Oleander Girl (Simon & Schuster, 2013).

A Review of Gish Jen’s Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self (Harvard University Press, 2013).

Gish Jen was selected to be guest lecturer of the distinguished Massey lectures in 2012; the product of this lectureship is Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self. This lecture series once also invited Maxine Hong Kingston and her work, To be the Poet (2000), resulted from that period. It is always a treat to read about a writer’s level of thinking that goes into the creative process. Of course, Jen and her marketers wisely chose a controversial title, bringing to mind the already infamous book, The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, by Amy Chua. Frankly, Jen’s lectures have actually very little to do with Asian parenting per se, but more closely track a rough differentiation in Eastern and Western modes of thinking and of creative production. Jen distinguishes between an independent—more Western—thinking and an interdependent—more Eastern—thinking; I use the word “more” quite deliberately, as Jen herself acknowledges the murkiness and the essentialization she must engage in order to conceive of this general binary. The point of Jen’s lectures seems to be an articulation of a kind of hybridity that she herself explores in her cultural productions; certainly there is the importance of the figure, or the character, but equally so is the context or the great frame of social relations in which the character finds herself enmeshed and often entangled. Jen is not out to say one mode is better or more enlightened than the other, but this sort of meditation is also an opportunity to get a better sense of her own trajectory as a writer, how she relates to her parents, and how even her parents might relate to their ancestors. The first lecture spends a great deal of time exploring Jen’s father’s life and his way of speaking about himself, which is ultimately a way of speaking around himself. By the last of the three lectures, Jen firmly roots her exploration of independence and interdependence from interpretations of her own fiction. It is an absolute treat to see this kind of exploration here and it makes me crave more of these kinds of publications—where writers are given an opportunity to explain some of the intentionality in their work and to engage in cultural analysis.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Tiger-Writing-Interdependent-Lectures-Civilization/dp/0674072839/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1363915326&sr=8-1&keywords=tiger+writing

A Review of Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority: Asian American Literature and Everyday Life (Oxford University Press, 2013); A Review of Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs (University of Hawaii Press, 2011)

There is certainly a risk in writing a book on the everyday, given its potential association with the banal, and yet Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority focuses on that very subject in her enterprising study of Asian American literature in relation what we might call “all things quotidian.” For those engaged in Asian American cultural studies, Lee’s archive is certainly not new or novel. In this respect, we might even call her selections part of the “everyday” of Asian Americanist critique, with chapters focused on Carlos Bulosan and Younghill Kang (chapter 1), Mine Okubo and Hisaye Yamamoto (chapter 2), Jade Snow Wong and Maxine Hong Kingston (chapter 3), Joy Kogawa, Nora Okja Keller, Ha Jin, and Lan Samantha Chang (chapter 4), Chang-rae Lee (chapter 5), and Frank Chin and Lois-Ann Yamanaka (chapter 6). At the same time, Lee’s approach shows the dynamic nature of common practices, familial object and experiences, revealing how Asian Americans have a necessarily vexed relationship to the everyday, in part mediated by the complicated nature and contours of racial formation. In this way, Lee helps us to rethink these canonical works and provides innovative readings in the process. Readings of the everyday within Asian American literature consequently makes for a lush and transformative scholarly study. My personal favorite chapter is the second, which focuses on the “uncanny” nature of the Japanese American internment experience in relation to the ways that internees attempted to reconstruct familiar environments even within the confines of what was a form of a prison. Thus, the familiar becomes slightly off-kilter, out of focus, and finally uncanny, as it becomes increasingly evident that the everyday cannot seamlessly be replicated in such inhospitable environments as the ones depicted in the aforementioned Okubo and Yamamoto. If there is a limit to Lee’s work, it is one common to most monographs: there simply is not enough time or space to cover all the possible works one might or possibly could. Indeed, her very short reading of Lahiri’s fiction in the conclusion makes us thirst for more.

The “racial formalism” phase of Asian American cultural critique continues with Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs, which forms a sort of second volume and companion to her earlier book, Begin Here: Reading Asian North American Autobiographies of Childhood. The shift from autobiography to memoir is deliberate precisely because, as Davis reveals, the memoirs she reads employ a collective standpoint (rather than the autobiographical self) of the family to deploy the narrative involved in life-writing. Of course, as with so many texts rooted in Asian ethnic contexts, these family stories are consistently a way to convey a larger tapestry. Davis contends: “The relational model of auto/biographical identity, I argue, functions on two levels in family memoirs: first, within the tet itself, as the author draws upon the stories of family members to complete her own, and, second, because these texts very consciously interpellate an audience. Asian American family memoirs manifestly present the individual author’s self as discursively constituted, as issues of literary traditions, immigrant history, identity politics, and cultural contingencies participate in the construction of the text” (11). As with Begin Here and Davis’s other book on the short story cycle, her knowledge of a given subfield is far-reading and visionary. She is one of the literary critics I can always go to get recommendations on books I have not even heard of and to expand the archive known more broadly as Asian American literature and culture. Indeed, most of the works she explores have not been reviewed here on Asian American literature fans and further still, most have not received much critical or literary attention elsewhere; these primary texts include: Jael Silliman’s Jewish Portraits, Indian Frames, Bruce Edward Hall’s Tea that Burns, and Mira Kamdar’s Motiba’s Tattoos. As with many other books in cultural criticism, Davis’s monograph remains in the hardcover form, but that should not deter anyone from requesting the title be added to a local university library.

Buy the Books Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Modern-Minority-American-Literature-Everyday/dp/0199915830/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1362341383&sr=8-1&keywords=modern+minority

http://www.amazon.com/Relative-Histories-Mediating-History-American/dp/0824834585/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1370056063&sr=8-1&keywords=relative+histories+rocio+davis

A Review of Tosca Lee’s Demon: A Memoir (B&H Books, 2010).

[image error]

I’ve been dealing with an apocalyptic respiratory illness for the last three days; my primary ailment is a brutal sore throat that is making it difficult to sleep at night. Nevertheless, the byproduct of staying in bed more often is that you get to read more books, as sickness-induced insomnia becomes your frequent bed partner. Tosca Lee’s Demon: A Memoir was a book that called out to me for the simple fact of its title. The story is a clever metafiction that seeks to explore the motivations behind why demons would want to torture humans so much. Our narrator is a man named Clay, who also happens to be an editor and who is still reeling from his divorce. One day he happens to bump into Lucian, a demon, who pushes him to tell Lucian’s tale about the Fall. Clay, at first completely horrified by his association with a demon, later comes to realize that this demonic story might actually serve to be a marketable narrative, one that could be consumed a reading public hungry for the spiritual and the supernatural. Lucian is drawn to be an obvious trickster figure; he assumes the guises of a number of different people and Clay is continually caught off guard when he appears. Once he does appear, Lucian provides Clay with another bit of the story of Lucifer’s fall from God’s grace and God’s shift in attention from these fallen angels to humans, who are continually referred to by Lucian as the “clay people.” As Lucian eventually details his story, readers also realize that Clay is revealing more and more about himself: the fallout from his divorce from Audrey, his connections to his coworkers, and his desire to find a sense of personal fulfillment. Tosca Lee provides some extra source material at the book’s conclusion which helps fill in some of the gaps left in by philosophically unclosed ending, but I tended to read this narrative far more metaphorically in relation to the process of writing itself and the demon being a kind of symbol of writing difficulties and blockages. Further still, there is an entire section devoted to Lee’s reconsideration of Biblical passages in her reconstruction of Lucian’s story. Certainly, Lee is able to effectively render the jealousy and the astonishment of the fallen angels over the many ways that the clay people are embraced and redeemed by God. At the same time, Lucian’s appearance as a kind of character who holds the reigns over Clay’s ability to write a manuscript seems to be more largely suggestive of that Higher Power, which plagues writers everywhere as they attempt to find a resolution to their stories and to their research projects.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Demon-A-Memoir-Tosca-Lee/dp/1433668807/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8&qid=1365876892&sr=8-4&keywords=tosca+lee

A Review of Andrew Fukuda’s The Prey (St. Martin’s Press, 2013).

So, this was the second book I finished during a stint while I was sick. This novel got me through a particularly bad part of my illness and part of it is simply attributable to the fact that Andrew Fukuda’s novel, The Prey, has such a smart concept built into it that even when the plotting might stall or our suspension of disbelief might waver, we still want to know how the various mysteries will be revealed. In Fukuda’s debut, The Hunt, he set up the basic guidelines to a world in which humans are called hepers and have been basically wiped out. The few that remain are in hiding, passing among the vampire-like beings who suspect that more hepers may indeed be out there. The second novel sees Fukuda opening up the story so that we get a better sense of the vampire-like beings and the possibility that more hepers have survived. With that in mind, I issue my “spoiler” warning here and continue.

In The Prey, Gene, along with the humans who had been housed in the dome from book 1 (Sissy, Epap, David, Jacob, and Ben), are still attempting to flee from the vampire-like beings, who are tracking them. Using a boat, they are able to escape by crossing over a waterfall; after some days traveling, they come upon a cabin and are soon spotted by a young girl, who happens to be human. This girl Claire asks them if they have the Origin; they are confused, but later Claire takes them to a small village community filled with humans—a place called the Mission—where they believe they might have been saved. Of course, we are not surprised when all is not as it seems. There is a strict division in gender roles and women are not often allowed to mingle with the men; the elders and Krugman—the so-called leaders—reek of conspiracy and it is not long before Sissy and Gene team up to find out about the secrets that are hidden in the Mission’s history. Fukuda uses this novel to link this fantastical narrative to a realist referents and there is some sense that Sissy and Gene have come to a place that is a post-apocalyptic version of our own world, now having been repopulated and having survived the accidental creation of the duskers, otherwise known as super soldiers and the term for our vampire-like beings. But, even as Sissy and Gene are set to move from the rural outpost to a place called Civilization, they realize that there are still unanswered questions and their pursuit of these questions allows Fukuda to stage a rather bloody ending in which some of our favorite human characters may not survive. As with many other supernatural trilogies being published, we come to discover that our seemingly normal protagonist, Gene, is more of a hero than we ever realized. Fukuda concludes with a cliffhanger ending that will make you immediately wish book 3 was already published. Fortunately, we won’t have to wait too long as it has a November 2013 listing.

Buy the Book here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Prey-Hunt-Andrew-Fukuda/dp/1250005116/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366081743&sr=8-1&keywords=the+prey

A Review of Susan Kim and Laurence Klavan’s Wasteland (HarperTeen 2013).

So, this book was the third one I read during what I am calling my 2013 plague period. Susan Kim and Laurence Klavan have already collaborated together on a set of graphic novels and this novel is their debut for the young adult paranormal urban fantasy romance fiction genre. Not surprisingly, Wasteland is planned as a trilogy. The novel is set in some postapocalyptic future in a landscape reminiscent of MadMax or Cherry2000. By this, I mean to say, water and food are scarce. The sun beats down mercilessly, and there are roving bands of baddies. People die by the time they are 19. Esther is 15. You do the math. If you thought it was rough being in the Logan’s Run world, well, Kim and Klavan have taken that up by 11 annual notches. Early on, our hero, Esther, is going about playing in the “wasteland” that is Prin, the town in which she and a few hardy others have decided to settled. She has a little friend named Skar, who is actually a creature called a Variant, beings who are born hermaphroditic, are roughly humanoid, and are generally hated and distrusted by humans. The feelings are mutual from the Variant side, so Esther and Skar’s friendship is already a kind of transgressive relationship. Because there are so few resources, townspeople are forced to work in groups to engage in various acts such as gleaning and harvesting. These acts are getting more difficult because the Variants, for whatever reason, have been staging more attacks against humans. Prin’s leader is a feckless man by the name of Rafe; he bows at the heels of another figure, Levi, who is the actual figurehead (and despot) of the entire region. Levi lives in a compound known as the Source, plays by his own rules, and apparently possesses a cache of goods that he exchanges with Prin’s townsfolk at exorbitant rates. Esther has one sister named Sarah, who reads and is generally a do-gooder. Finally, Esther has one friend in Joseph who lives in another remote part of town by himself with ten cats; he’s an eccentric, so his contact with anyone is pretty much limited to Esther. The novel starts moving toward its ending arc when Caleb comes into town, looking for vengeance. His wife was murdered and his child abducted by a group of variants; he believes that by tracking down the person who sold the variants a type of accelerant that he will be able to enact his own retribution. Of course, we soon discover that Levi is wrapped up in all of this chaos. He’s been pitting the Variants and the Humans against each other, to direct attention away from his true goal: finding a source of water beneath Prin. Kim and Klavan’s first book in the series is quite bleak, though they do manage to provide a conclusion that gives some of its major characters a reprieve. Yet, when Esther leaves readers with the sentiments that she is unsure how much longer anyone can stay in Prin, we realize that the sequel is already in the works.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Wasteland-Trilogy-Susan-Kim/dp/006211851X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366172293&sr=8-1&keywords=Laurence+Klavan+Susan+Kim

A Review of Eddie Huang’s Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir (Spiegel and Grau, 2013)

Eddie Huang’s Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir was the fourth book I read during what I am calling my 2013 plague period. I wasn’t entirely prepared for the “narrative” voice in this work, which is sort of a mix of slang and Huang’s comedic take at his own upbringing and his movement into the world of restaurant cuisine. He is the proprietor of a restaurant called Baohaus (a fun punning of those lovely Bao bun type dishes):

http://www.baohausnyc.com/menu.html

Take a gander at that menu and you can see that Huang streamlines in order to focus on the essentials. In any case, Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir does provide us with a unique comic narrative of acculturation. Eddie begins his tale with an obvious love of food and draws himself out to be a kind of anti-model minority figure, invested in African American popular culture and football. Eddie grows up primarily in a Southern state, Florida, where his father tries his luck at an American-type restaurant. He is raised alongside his two brothers, Emery and Evan, with the spirit of his mother’s desire for them to achieve economic stability. Indeed, it is his mother’s desire for financial success that is a looming presence in Eddie’s life. As the memoir continues, Eddie comes of age, which involves, among other things: taking English classes in college, selling weed, getting busted for selling weed, traveling to Taiwan on a language and culture program, attending school in Pittsburgh, getting a law degree, selling more weed for awhile, going on a reality television cooking competition, and then finally deciding to open up a restaurant. Though Huang’s memoir is humorous, the underlying impulse about what it means to be an ethnic minority in America is clear, especially as focused through his desire to find personal and professional fulfillment. This memoir is certainly one that could be paired well with a more traditional memoir, such as Jade Snow Wong’s Fifth Chinese Daughter. And I am certainly going to add this book to my teachable texts list.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Fresh-Off-Boat-A-Memoir/dp/0679644881/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366215680&sr=8-1&keywords=Eddie+Huang

A Review of Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Oleander Girl (Simon & Schuster, 2013).

Of the Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni works I’ve had the chance to read, Oleander Girl, her latest, is definitely my favorite. Divakaruni is the author of numerous publications, including but not limited to Arranged Marriage: Stories (1995); The Mistress of Spices (1997), Sister of my Heart (1999). For me, Oleander Girl rises to the top based upon the surprise reveal given about two thirds of the way through. But, I am getting ahead of myself. Oleander Girl is the story of Korobi Roy, who is raised by her grandparents, Sarojini and Bimal. She is engaged to be married to a young man of affluent background name Rajat Bose. Though Korobi is herself of a more modest, upper middle-class background, Rajat falls madly in love with her and makes it clear that Korobi is the woman for him. As the date for the wedding draws close, Korobi and her grandfather get in a verbal spat over what she is wearing. Before Korobi is able to reconcile with him, he dies from an acute heart attack. Grief stricken and wracked with guilt, Korobi finds herself completely unmoored and seeking direction. It is during this period that Korobi discovers the true story behind her parentage. Her mother Anu Roy traveled to the United States to attend college and had fallen in love with an American, someone out of caste and out of class. This marriage obviously was not supported by Anu’s parents (Korobi’s grandparents) and resulted in considerable strain among the family members at large. When Anu falls pregnant, a momentary rapprochement occurs and she is allowed to visit her parents; during that period, there is a tragic accident and Anu is killed. Because she was so late into the pregnancy, doctors are able to save Korobi. Bimal—who is a lawyer—is able to stage it to make it seem as if Korobi has died, thus effectively cutting of Korobi’s father from claiming her. After Korobi learns of the truth behind what happened to her mother and her father, she realizes she cannot yet marry Rajat and embarks on a hasty trip to America, with the goal of finding her biological father. Enlisting help from new found friends—Desai and Vic—Korobi is relentless in her quest, even as her relationship to Rajat suffers under the strain of their physical separation. Rajat begins to wonder whether or not he is truly in love with Korobi and begins to entertain and to welcome the attentions of an old flame named Sonia. Complicating matters is that the Rajat’s family is facing financial crises within their business dealings. Sarojini, too, must consider what to do with the family’s limited finances and whether or not she must sell the home. There are many plot strands to cover in this novel and Divakaruni is always game to engage them and to tidy them up in the end. The novel is told from alternating first (in Korobi’s perspective) and third person perspectives (following a number of different characters, including Rajat, Mrs. Bose, Sarojini, among others). There is a Victorian courtship impulse to this novel and it ends exactly as you might expect, but Divakuni’s late stage surprise is what raises this novel to another level. Oleander Girl is as much about race relations in America as it is about the modern Indian woman who is struggling to find her independence. A truly transnational fictional work.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Oleander-Girl-Chitra-Banerjee-Divakaruni/dp/1451695659/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366435488&sr=8-1&keywords=oleander+girl

In this post, reviews of: Gish Jen’s Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self (Harvard University Press, 2013); Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority: Asian American Literature and Everyday Life (Oxford University Press, 2013); A Review of Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs (University of Hawaii Press, 2011); Tosca Lee’s Demon: A Memoir (B&H Books, 2010); Andrew Fukuda’s The Prey (St. Martin’s Press, 2013); Susan Kim and Laurence Klavan’s Wasteland (HarperTeen 2013); Eddie Huang’s Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir (Spiegel and Grau, 2013); Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Oleander Girl (Simon & Schuster, 2013).

A Review of Gish Jen’s Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self (Harvard University Press, 2013).

Gish Jen was selected to be guest lecturer of the distinguished Massey lectures in 2012; the product of this lectureship is Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and The Interdependent Self. This lecture series once also invited Maxine Hong Kingston and her work, To be the Poet (2000), resulted from that period. It is always a treat to read about a writer’s level of thinking that goes into the creative process. Of course, Jen and her marketers wisely chose a controversial title, bringing to mind the already infamous book, The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, by Amy Chua. Frankly, Jen’s lectures have actually very little to do with Asian parenting per se, but more closely track a rough differentiation in Eastern and Western modes of thinking and of creative production. Jen distinguishes between an independent—more Western—thinking and an interdependent—more Eastern—thinking; I use the word “more” quite deliberately, as Jen herself acknowledges the murkiness and the essentialization she must engage in order to conceive of this general binary. The point of Jen’s lectures seems to be an articulation of a kind of hybridity that she herself explores in her cultural productions; certainly there is the importance of the figure, or the character, but equally so is the context or the great frame of social relations in which the character finds herself enmeshed and often entangled. Jen is not out to say one mode is better or more enlightened than the other, but this sort of meditation is also an opportunity to get a better sense of her own trajectory as a writer, how she relates to her parents, and how even her parents might relate to their ancestors. The first lecture spends a great deal of time exploring Jen’s father’s life and his way of speaking about himself, which is ultimately a way of speaking around himself. By the last of the three lectures, Jen firmly roots her exploration of independence and interdependence from interpretations of her own fiction. It is an absolute treat to see this kind of exploration here and it makes me crave more of these kinds of publications—where writers are given an opportunity to explain some of the intentionality in their work and to engage in cultural analysis.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Tiger-Writing-Interdependent-Lectures-Civilization/dp/0674072839/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1363915326&sr=8-1&keywords=tiger+writing

A Review of Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority: Asian American Literature and Everyday Life (Oxford University Press, 2013); A Review of Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs (University of Hawaii Press, 2011)

There is certainly a risk in writing a book on the everyday, given its potential association with the banal, and yet Yoon Sun Lee’s Modern Minority focuses on that very subject in her enterprising study of Asian American literature in relation what we might call “all things quotidian.” For those engaged in Asian American cultural studies, Lee’s archive is certainly not new or novel. In this respect, we might even call her selections part of the “everyday” of Asian Americanist critique, with chapters focused on Carlos Bulosan and Younghill Kang (chapter 1), Mine Okubo and Hisaye Yamamoto (chapter 2), Jade Snow Wong and Maxine Hong Kingston (chapter 3), Joy Kogawa, Nora Okja Keller, Ha Jin, and Lan Samantha Chang (chapter 4), Chang-rae Lee (chapter 5), and Frank Chin and Lois-Ann Yamanaka (chapter 6). At the same time, Lee’s approach shows the dynamic nature of common practices, familial object and experiences, revealing how Asian Americans have a necessarily vexed relationship to the everyday, in part mediated by the complicated nature and contours of racial formation. In this way, Lee helps us to rethink these canonical works and provides innovative readings in the process. Readings of the everyday within Asian American literature consequently makes for a lush and transformative scholarly study. My personal favorite chapter is the second, which focuses on the “uncanny” nature of the Japanese American internment experience in relation to the ways that internees attempted to reconstruct familiar environments even within the confines of what was a form of a prison. Thus, the familiar becomes slightly off-kilter, out of focus, and finally uncanny, as it becomes increasingly evident that the everyday cannot seamlessly be replicated in such inhospitable environments as the ones depicted in the aforementioned Okubo and Yamamoto. If there is a limit to Lee’s work, it is one common to most monographs: there simply is not enough time or space to cover all the possible works one might or possibly could. Indeed, her very short reading of Lahiri’s fiction in the conclusion makes us thirst for more.

The “racial formalism” phase of Asian American cultural critique continues with Rocío G. Davis’s Relative Histories: Mediating History in Asian American Family Memoirs, which forms a sort of second volume and companion to her earlier book, Begin Here: Reading Asian North American Autobiographies of Childhood. The shift from autobiography to memoir is deliberate precisely because, as Davis reveals, the memoirs she reads employ a collective standpoint (rather than the autobiographical self) of the family to deploy the narrative involved in life-writing. Of course, as with so many texts rooted in Asian ethnic contexts, these family stories are consistently a way to convey a larger tapestry. Davis contends: “The relational model of auto/biographical identity, I argue, functions on two levels in family memoirs: first, within the tet itself, as the author draws upon the stories of family members to complete her own, and, second, because these texts very consciously interpellate an audience. Asian American family memoirs manifestly present the individual author’s self as discursively constituted, as issues of literary traditions, immigrant history, identity politics, and cultural contingencies participate in the construction of the text” (11). As with Begin Here and Davis’s other book on the short story cycle, her knowledge of a given subfield is far-reading and visionary. She is one of the literary critics I can always go to get recommendations on books I have not even heard of and to expand the archive known more broadly as Asian American literature and culture. Indeed, most of the works she explores have not been reviewed here on Asian American literature fans and further still, most have not received much critical or literary attention elsewhere; these primary texts include: Jael Silliman’s Jewish Portraits, Indian Frames, Bruce Edward Hall’s Tea that Burns, and Mira Kamdar’s Motiba’s Tattoos. As with many other books in cultural criticism, Davis’s monograph remains in the hardcover form, but that should not deter anyone from requesting the title be added to a local university library.

Buy the Books Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Modern-Minority-American-Literature-Everyday/dp/0199915830/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1362341383&sr=8-1&keywords=modern+minority

http://www.amazon.com/Relative-Histories-Mediating-History-American/dp/0824834585/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1370056063&sr=8-1&keywords=relative+histories+rocio+davis

A Review of Tosca Lee’s Demon: A Memoir (B&H Books, 2010).

[image error]

I’ve been dealing with an apocalyptic respiratory illness for the last three days; my primary ailment is a brutal sore throat that is making it difficult to sleep at night. Nevertheless, the byproduct of staying in bed more often is that you get to read more books, as sickness-induced insomnia becomes your frequent bed partner. Tosca Lee’s Demon: A Memoir was a book that called out to me for the simple fact of its title. The story is a clever metafiction that seeks to explore the motivations behind why demons would want to torture humans so much. Our narrator is a man named Clay, who also happens to be an editor and who is still reeling from his divorce. One day he happens to bump into Lucian, a demon, who pushes him to tell Lucian’s tale about the Fall. Clay, at first completely horrified by his association with a demon, later comes to realize that this demonic story might actually serve to be a marketable narrative, one that could be consumed a reading public hungry for the spiritual and the supernatural. Lucian is drawn to be an obvious trickster figure; he assumes the guises of a number of different people and Clay is continually caught off guard when he appears. Once he does appear, Lucian provides Clay with another bit of the story of Lucifer’s fall from God’s grace and God’s shift in attention from these fallen angels to humans, who are continually referred to by Lucian as the “clay people.” As Lucian eventually details his story, readers also realize that Clay is revealing more and more about himself: the fallout from his divorce from Audrey, his connections to his coworkers, and his desire to find a sense of personal fulfillment. Tosca Lee provides some extra source material at the book’s conclusion which helps fill in some of the gaps left in by philosophically unclosed ending, but I tended to read this narrative far more metaphorically in relation to the process of writing itself and the demon being a kind of symbol of writing difficulties and blockages. Further still, there is an entire section devoted to Lee’s reconsideration of Biblical passages in her reconstruction of Lucian’s story. Certainly, Lee is able to effectively render the jealousy and the astonishment of the fallen angels over the many ways that the clay people are embraced and redeemed by God. At the same time, Lucian’s appearance as a kind of character who holds the reigns over Clay’s ability to write a manuscript seems to be more largely suggestive of that Higher Power, which plagues writers everywhere as they attempt to find a resolution to their stories and to their research projects.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Demon-A-Memoir-Tosca-Lee/dp/1433668807/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8&qid=1365876892&sr=8-4&keywords=tosca+lee

A Review of Andrew Fukuda’s The Prey (St. Martin’s Press, 2013).

So, this was the second book I finished during a stint while I was sick. This novel got me through a particularly bad part of my illness and part of it is simply attributable to the fact that Andrew Fukuda’s novel, The Prey, has such a smart concept built into it that even when the plotting might stall or our suspension of disbelief might waver, we still want to know how the various mysteries will be revealed. In Fukuda’s debut, The Hunt, he set up the basic guidelines to a world in which humans are called hepers and have been basically wiped out. The few that remain are in hiding, passing among the vampire-like beings who suspect that more hepers may indeed be out there. The second novel sees Fukuda opening up the story so that we get a better sense of the vampire-like beings and the possibility that more hepers have survived. With that in mind, I issue my “spoiler” warning here and continue.

In The Prey, Gene, along with the humans who had been housed in the dome from book 1 (Sissy, Epap, David, Jacob, and Ben), are still attempting to flee from the vampire-like beings, who are tracking them. Using a boat, they are able to escape by crossing over a waterfall; after some days traveling, they come upon a cabin and are soon spotted by a young girl, who happens to be human. This girl Claire asks them if they have the Origin; they are confused, but later Claire takes them to a small village community filled with humans—a place called the Mission—where they believe they might have been saved. Of course, we are not surprised when all is not as it seems. There is a strict division in gender roles and women are not often allowed to mingle with the men; the elders and Krugman—the so-called leaders—reek of conspiracy and it is not long before Sissy and Gene team up to find out about the secrets that are hidden in the Mission’s history. Fukuda uses this novel to link this fantastical narrative to a realist referents and there is some sense that Sissy and Gene have come to a place that is a post-apocalyptic version of our own world, now having been repopulated and having survived the accidental creation of the duskers, otherwise known as super soldiers and the term for our vampire-like beings. But, even as Sissy and Gene are set to move from the rural outpost to a place called Civilization, they realize that there are still unanswered questions and their pursuit of these questions allows Fukuda to stage a rather bloody ending in which some of our favorite human characters may not survive. As with many other supernatural trilogies being published, we come to discover that our seemingly normal protagonist, Gene, is more of a hero than we ever realized. Fukuda concludes with a cliffhanger ending that will make you immediately wish book 3 was already published. Fortunately, we won’t have to wait too long as it has a November 2013 listing.

Buy the Book here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Prey-Hunt-Andrew-Fukuda/dp/1250005116/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366081743&sr=8-1&keywords=the+prey

A Review of Susan Kim and Laurence Klavan’s Wasteland (HarperTeen 2013).

So, this book was the third one I read during what I am calling my 2013 plague period. Susan Kim and Laurence Klavan have already collaborated together on a set of graphic novels and this novel is their debut for the young adult paranormal urban fantasy romance fiction genre. Not surprisingly, Wasteland is planned as a trilogy. The novel is set in some postapocalyptic future in a landscape reminiscent of MadMax or Cherry2000. By this, I mean to say, water and food are scarce. The sun beats down mercilessly, and there are roving bands of baddies. People die by the time they are 19. Esther is 15. You do the math. If you thought it was rough being in the Logan’s Run world, well, Kim and Klavan have taken that up by 11 annual notches. Early on, our hero, Esther, is going about playing in the “wasteland” that is Prin, the town in which she and a few hardy others have decided to settled. She has a little friend named Skar, who is actually a creature called a Variant, beings who are born hermaphroditic, are roughly humanoid, and are generally hated and distrusted by humans. The feelings are mutual from the Variant side, so Esther and Skar’s friendship is already a kind of transgressive relationship. Because there are so few resources, townspeople are forced to work in groups to engage in various acts such as gleaning and harvesting. These acts are getting more difficult because the Variants, for whatever reason, have been staging more attacks against humans. Prin’s leader is a feckless man by the name of Rafe; he bows at the heels of another figure, Levi, who is the actual figurehead (and despot) of the entire region. Levi lives in a compound known as the Source, plays by his own rules, and apparently possesses a cache of goods that he exchanges with Prin’s townsfolk at exorbitant rates. Esther has one sister named Sarah, who reads and is generally a do-gooder. Finally, Esther has one friend in Joseph who lives in another remote part of town by himself with ten cats; he’s an eccentric, so his contact with anyone is pretty much limited to Esther. The novel starts moving toward its ending arc when Caleb comes into town, looking for vengeance. His wife was murdered and his child abducted by a group of variants; he believes that by tracking down the person who sold the variants a type of accelerant that he will be able to enact his own retribution. Of course, we soon discover that Levi is wrapped up in all of this chaos. He’s been pitting the Variants and the Humans against each other, to direct attention away from his true goal: finding a source of water beneath Prin. Kim and Klavan’s first book in the series is quite bleak, though they do manage to provide a conclusion that gives some of its major characters a reprieve. Yet, when Esther leaves readers with the sentiments that she is unsure how much longer anyone can stay in Prin, we realize that the sequel is already in the works.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Wasteland-Trilogy-Susan-Kim/dp/006211851X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366172293&sr=8-1&keywords=Laurence+Klavan+Susan+Kim

A Review of Eddie Huang’s Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir (Spiegel and Grau, 2013)

Eddie Huang’s Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir was the fourth book I read during what I am calling my 2013 plague period. I wasn’t entirely prepared for the “narrative” voice in this work, which is sort of a mix of slang and Huang’s comedic take at his own upbringing and his movement into the world of restaurant cuisine. He is the proprietor of a restaurant called Baohaus (a fun punning of those lovely Bao bun type dishes):

http://www.baohausnyc.com/menu.html

Take a gander at that menu and you can see that Huang streamlines in order to focus on the essentials. In any case, Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir does provide us with a unique comic narrative of acculturation. Eddie begins his tale with an obvious love of food and draws himself out to be a kind of anti-model minority figure, invested in African American popular culture and football. Eddie grows up primarily in a Southern state, Florida, where his father tries his luck at an American-type restaurant. He is raised alongside his two brothers, Emery and Evan, with the spirit of his mother’s desire for them to achieve economic stability. Indeed, it is his mother’s desire for financial success that is a looming presence in Eddie’s life. As the memoir continues, Eddie comes of age, which involves, among other things: taking English classes in college, selling weed, getting busted for selling weed, traveling to Taiwan on a language and culture program, attending school in Pittsburgh, getting a law degree, selling more weed for awhile, going on a reality television cooking competition, and then finally deciding to open up a restaurant. Though Huang’s memoir is humorous, the underlying impulse about what it means to be an ethnic minority in America is clear, especially as focused through his desire to find personal and professional fulfillment. This memoir is certainly one that could be paired well with a more traditional memoir, such as Jade Snow Wong’s Fifth Chinese Daughter. And I am certainly going to add this book to my teachable texts list.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Fresh-Off-Boat-A-Memoir/dp/0679644881/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366215680&sr=8-1&keywords=Eddie+Huang

A Review of Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Oleander Girl (Simon & Schuster, 2013).

Of the Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni works I’ve had the chance to read, Oleander Girl, her latest, is definitely my favorite. Divakaruni is the author of numerous publications, including but not limited to Arranged Marriage: Stories (1995); The Mistress of Spices (1997), Sister of my Heart (1999). For me, Oleander Girl rises to the top based upon the surprise reveal given about two thirds of the way through. But, I am getting ahead of myself. Oleander Girl is the story of Korobi Roy, who is raised by her grandparents, Sarojini and Bimal. She is engaged to be married to a young man of affluent background name Rajat Bose. Though Korobi is herself of a more modest, upper middle-class background, Rajat falls madly in love with her and makes it clear that Korobi is the woman for him. As the date for the wedding draws close, Korobi and her grandfather get in a verbal spat over what she is wearing. Before Korobi is able to reconcile with him, he dies from an acute heart attack. Grief stricken and wracked with guilt, Korobi finds herself completely unmoored and seeking direction. It is during this period that Korobi discovers the true story behind her parentage. Her mother Anu Roy traveled to the United States to attend college and had fallen in love with an American, someone out of caste and out of class. This marriage obviously was not supported by Anu’s parents (Korobi’s grandparents) and resulted in considerable strain among the family members at large. When Anu falls pregnant, a momentary rapprochement occurs and she is allowed to visit her parents; during that period, there is a tragic accident and Anu is killed. Because she was so late into the pregnancy, doctors are able to save Korobi. Bimal—who is a lawyer—is able to stage it to make it seem as if Korobi has died, thus effectively cutting of Korobi’s father from claiming her. After Korobi learns of the truth behind what happened to her mother and her father, she realizes she cannot yet marry Rajat and embarks on a hasty trip to America, with the goal of finding her biological father. Enlisting help from new found friends—Desai and Vic—Korobi is relentless in her quest, even as her relationship to Rajat suffers under the strain of their physical separation. Rajat begins to wonder whether or not he is truly in love with Korobi and begins to entertain and to welcome the attentions of an old flame named Sonia. Complicating matters is that the Rajat’s family is facing financial crises within their business dealings. Sarojini, too, must consider what to do with the family’s limited finances and whether or not she must sell the home. There are many plot strands to cover in this novel and Divakaruni is always game to engage them and to tidy them up in the end. The novel is told from alternating first (in Korobi’s perspective) and third person perspectives (following a number of different characters, including Rajat, Mrs. Bose, Sarojini, among others). There is a Victorian courtship impulse to this novel and it ends exactly as you might expect, but Divakuni’s late stage surprise is what raises this novel to another level. Oleander Girl is as much about race relations in America as it is about the modern Indian woman who is struggling to find her independence. A truly transnational fictional work.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Oleander-Girl-Chitra-Banerjee-Divakaruni/dp/1451695659/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1366435488&sr=8-1&keywords=oleander+girl

Published on May 31, 2013 20:34

May 1, 2013

Asian American Literature Megapost for May 1 2013

Asian American Literature Megapost for May 1 2013

In this MYSTERY THEMED post reviews of: Steph Cha’s Follow Her Home (Minotaur Books, 2013); Tess Gerritsen’s Last to Die (Ballantine Books, 2012); .S. Lee’s, The Agency 1: A Spy in the House (Candlewick Press, 2010); The Agency 2: The Body at the Tower (Candlewick Press, 2010); The Agency 3: The Traitor in the Tunnel (Candlewick Press, 2012).

A Review of Steph Cha’s Follow Her Home (Minotaur Books, 2013).

Steph Cha’s debut novel Follow Her Home reveals a writer keenly aware and inspired by the subgenre of American noir fiction. With repeated references to Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep, we know we are moving into a seedy underworld that is best set in a city like Los Angeles. Cha’s narrator is the indefatigable Juniper Song, a twenty-something who in her spare time can apparently moonlight as an unofficial investigator. A request from a close friend named Luke—who hails from a very upper crust background—requires Song to follow a young Korean American woman named Lori Lim, who may or may not be involved in an affair with Luke’s father, the business magnate known as William Cook. We are not surprised when we begin to discover that the mystery surrounding Lori is bigger and messier than Song could ever realize. Indeed, Song will soon be intimidated into keeping silent regarding everything she might have seen regarding Lori; a dead body found in the trunk of her car also alerts her to the fact that the shadowy figures involved in Lori’s life are not to be trifled with. Of course, Song is not about to back down; she enlists the friend of a former flame turned legal expert, Diego, and begins to find out what she can about Lori, in the hopes that she can protect herself and her family. Cha uses a very effective doubled narrative here that moves Song back into the past; we begin to see that Song’s interest in Lori is not merely related to this mystery. Indeed, Lori in some ways reminds Song of her connection to her younger sister, Iris. In that particular subplot, Song realizes that she does not know as much about her sister as she had thought and her efforts to find out more about Iris’s romantic history leads to a very climactic reveal late in the narrative that provides the main story arc more texture. As with any noir, motivations and first impressions are never directly transparent and many of the characters introduced know much more than they are willing at first to admit. As the body count begins to pile up, Song realizes that the stakes of this investigation have moved into a register where she knows she must see this mystery to its end, else she herself may be the next one to be found dead. Cha’s debut novel would fit very well into any American detective fiction course and would especially pair well with Walter Mosley, in her exploration of race, ethnicity, and the urban metropolis known as Los Angeles. The novel would also serve as a kind of effective contrast with another novel I love, Suk Kim’s Interpreter, in the exploration of the Korean American woman turned unofficial detective.

For another glowing review of this title please do see this link:

http://www.latimes.com/features/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-steph-cha-20130407,0,3256154.story

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Follow-Her-Home-Steph-Cha/dp/1250009626/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1365353857&sr=8-1&keywords=Steph+Cha

A Review of Tess Gerritsen’s Last to Die (Ballantine Books, 2012).

I was saving this book to read for a point where I needed something a little bit more plot-driven to consume my time and on a trip to visit some family, it provided some much needed frivolity. Last to Die is the latest installment in Tess Gerritsen’s long running and very popular Rizzoli & Isles series, which has been adapted into a television serial. The premise is spooky enough. It seems as though there are children being targeted repeatedly, so much so that any family they are connected with—first biological, then later adoptive—are killed off. Thus, the three main children in this novel have all suffered family massacres not once, but twice. Gerritsen adds yet another interesting element into the equation by uniting these three characters at a special school, The Evensong Boarding School, for children who have been subjected to major traumas. The school, located in Maine, and away from the Boston locale that grounds the series itself, is the perfect venue for this mystery plot to begin taking on other interesting textures. For those who are knowledgeable about the series, the fact that the Evensong Boarding School is run by the Mephisto Society is already potential cause for concern. Further still, once the school psychologist is found dead, having jumped from a high building and under suspicious circumstances, it becomes clear that that all is not well at the school. Gerritsen also uses enigmatic intercuts that ramp up the tension in the plotting—a narrative device I recall from Silent Girl, the last novel in the series. Readers are pushed to make sense of that narrative against the main plotting and the connections don’t become clear until late into the mystery. Gerritsen also manages to balance the detective plot against the personal trials of its two female protagonists, who are struggling still to rebuild their friendship due to past events. Rizzoli’s parents in particular are the subject of considerable romantic complications, so that subplot gives readers much needed space to breathe, especially because the body count begins to pile up. Even animals are sacrificed in ritualistic killings. Fans of the series and of the mystery genre should be more than happy with this offering.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Last-Die-Rizzoli-Isles-Novel/dp/0345515633/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1367339453&sr=8-1&keywords=Tess+Gerritsen

A Review of Y.S. Lee’s, The Agency 1: A Spy in the House (Candlewick Press, 2010); The Agency 2: The Body at the Tower (Candlewick Press, 2010); The Agency 3: The Traitor in the Tunnel (Candlewick Press, 2012).

In Y.S. Lee’s deliciously fun The Agency series, our heroine is Mary Quinn, a young girl of a questionable background who is saved at the beginning of the novel by the mysterious Agency, who is sort of devoted to the recovery and reformulation of a women’s lives. The Agency is set in the Victorian era and the writer, Y.S. Lee, is no stranger to this period. As our faithful amazon webpage tells us: “Y. S. Lee has a PhD in Victorian literature and culture and says her research inspired her to write A SPY IN THE HOUSE, ‘a totally unrealistic, completely fictitious antidote to the fate that would otherwise swallow a girl like Mary Quinn.’ Y. S. Lee lives in Ontario, Canada.” In this respect, the “agency” enables girls like Mary Quinn a second chance because she lives on the margins of society as a petty thief. The Agency allows Mary to develop other skills, but there’s still limited options: should be become a wife, a governess, or servant; the other unsavory options being bandied about include becoming a prostitute or mistress. So, Lee creates an alternative job trajectory for Mary in this counterfactual, “totally unrealistic,” but nevertheless super fun speculative fiction wherein Mary can become a spy and report upon a particular household as a companion to the daughter of the prime suspect: a one Mr. Thorold, who may or may not be involved with the theft of priceless Indian subcontinent artifacts. At this point, it’s important to pause to say that one of the Lee’s great strengths in the strongly transnational and postcolonial tinge to her collection. Goods and services are being shipped all over the world in the novel, linking the Victorian era London to different nodal points for colonial capitalistic investments. Lee, of course, wants to make sure that even if there isn’t a tried and true marriage plot or courtship plot afloat, that there could be an alternative romance plot as Mary must deal with James Easton, a man who is researching the Thorold’s business dealings to find out whether or not they are as upstanding as they purport to be. James is a worthy counterpart to Mary insofar as he immediately notices how different she is. Her difference is, of course, another aspect that Lee plays with in one of the big surprises mid-way through the novel, which I will refuse to spoil for you. Suffice it to say that Lee’s first book in the Agency is that rare young adult work with a historical texture, a fantasy register, a detective fiction, and a courtship/romance all rolled into one.

[image error]

In the second book in the series, we found our heroine Mary Quinn, going under very deep cover, but this time as a young boy (renamed as Mark Quinn), working at a building site. She’s been dispatched to discover more details concerning the suspicious circumstances of a worker who was found dead, having fallen from the titular tower. Though Mary is game for this job, her overseers at the Agency are wary that such a duty might have psychological ramifications. You see: before Mary was saved and reformed by the Agency, she lived on the streets as a petty thief and hoodlum; she was able to survive in part, often relying upon disguises and passing as a man. Her elders wonder if such a job might trigger unsavory past experiences that could compromise her surveillance activities. Despite this warning, Mary decides that she can do the job, even requesting that she take residence at a working class type facility wherein she would not have the comforts or even the advantages of decent food. Mary’s work is at first not too difficult; she is able to get a job through Harkness, the site engineer, and begins working for the various people below him, which include the imposing and rather spiteful, Keenan, as well as his colleague, Reid. Of course, this series would not be complete with its central romance and fortunately, Lee sees fit to have James Easton, from book 1, return from his travels in India. He’s hired by Harkness to begin an independent assessment of the building site that would be conducted in order to clear him or any of his employees from wrongdoing in the death of Wick. When Mary—as Mark—accidentally bumps into him, James is one of the few to see so easily through the disguise, but he chooses not to break her cover. Indeed, this sequel sees James Easton willing to engage yet another partnership with Mary, presumably of course because of his strong feelings for her. There are of course the occasional issues related to Mary’s complicated identity background, which adds yet another wrinkle to the many dilemmas that arise in the course of the plotting. Lee’s narrative here occasionally flags as it attempts to retain tension throughout, but overall, the book is a spirited, if counterfactual look at an undercover women’s agency during the Victorian era.

In the latest installment, The Traitor in the Tunnel, Mary Quinn is actually undercover in Buckingham Palace! She is dispatched by the Agency in order to find out about a thief that may be pilfering precious items from the royal household. Of course, Lee is never intent to keep the first mystery the only one and soon other issues arise. Most importantly, the Prince of Wales is caught up in a murder scandal in which a close friend might have been killed in an opium den. Interestingly enough, the accused murdered actually may have ties to Mary herself, which ends up complicating and stretching out Mary’s own investments in her sleuthing. I am deliberately being cagey about the potential connection between Mary and the murderer precisely because I’ve attempted to keep a major plot point unspoiled that is revealed from the first book. Finally, Mary’s romance-nemesis, James Easton, returns yet again, as he is contracted to help with the building of a sewer system below London. As Mary soon discovers, the sewer and its connection to Buckingham Palace is a matter of national security. Fans of mystery and of YA historical will again be delighted by this title. Lee clearly has fun with her characters in this spirited third in the series. Fortunately, there are apparently plans for a fourth to appear sometime soon!

Buy the Books Here

http://www.amazon.com/The-Agency-House-Y-S-Lee/dp/076365289X/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1359052764&sr=8-2&keywords=Y.S.+Lee

http://www.amazon.com/The-Agency-Body-Tower/dp/0763656437/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1361139912&sr=8-3&keywords=Y.S.+Lee

http://www.amazon.com/The-Agency-Traitor-Tunnel/dp/0763663441/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1367416563&sr=8-1&keywords=Y.S.+Lee

In this MYSTERY THEMED post reviews of: Steph Cha’s Follow Her Home (Minotaur Books, 2013); Tess Gerritsen’s Last to Die (Ballantine Books, 2012); .S. Lee’s, The Agency 1: A Spy in the House (Candlewick Press, 2010); The Agency 2: The Body at the Tower (Candlewick Press, 2010); The Agency 3: The Traitor in the Tunnel (Candlewick Press, 2012).

A Review of Steph Cha’s Follow Her Home (Minotaur Books, 2013).

Steph Cha’s debut novel Follow Her Home reveals a writer keenly aware and inspired by the subgenre of American noir fiction. With repeated references to Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep, we know we are moving into a seedy underworld that is best set in a city like Los Angeles. Cha’s narrator is the indefatigable Juniper Song, a twenty-something who in her spare time can apparently moonlight as an unofficial investigator. A request from a close friend named Luke—who hails from a very upper crust background—requires Song to follow a young Korean American woman named Lori Lim, who may or may not be involved in an affair with Luke’s father, the business magnate known as William Cook. We are not surprised when we begin to discover that the mystery surrounding Lori is bigger and messier than Song could ever realize. Indeed, Song will soon be intimidated into keeping silent regarding everything she might have seen regarding Lori; a dead body found in the trunk of her car also alerts her to the fact that the shadowy figures involved in Lori’s life are not to be trifled with. Of course, Song is not about to back down; she enlists the friend of a former flame turned legal expert, Diego, and begins to find out what she can about Lori, in the hopes that she can protect herself and her family. Cha uses a very effective doubled narrative here that moves Song back into the past; we begin to see that Song’s interest in Lori is not merely related to this mystery. Indeed, Lori in some ways reminds Song of her connection to her younger sister, Iris. In that particular subplot, Song realizes that she does not know as much about her sister as she had thought and her efforts to find out more about Iris’s romantic history leads to a very climactic reveal late in the narrative that provides the main story arc more texture. As with any noir, motivations and first impressions are never directly transparent and many of the characters introduced know much more than they are willing at first to admit. As the body count begins to pile up, Song realizes that the stakes of this investigation have moved into a register where she knows she must see this mystery to its end, else she herself may be the next one to be found dead. Cha’s debut novel would fit very well into any American detective fiction course and would especially pair well with Walter Mosley, in her exploration of race, ethnicity, and the urban metropolis known as Los Angeles. The novel would also serve as a kind of effective contrast with another novel I love, Suk Kim’s Interpreter, in the exploration of the Korean American woman turned unofficial detective.

For another glowing review of this title please do see this link:

http://www.latimes.com/features/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-steph-cha-20130407,0,3256154.story

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Follow-Her-Home-Steph-Cha/dp/1250009626/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1365353857&sr=8-1&keywords=Steph+Cha

A Review of Tess Gerritsen’s Last to Die (Ballantine Books, 2012).

I was saving this book to read for a point where I needed something a little bit more plot-driven to consume my time and on a trip to visit some family, it provided some much needed frivolity. Last to Die is the latest installment in Tess Gerritsen’s long running and very popular Rizzoli & Isles series, which has been adapted into a television serial. The premise is spooky enough. It seems as though there are children being targeted repeatedly, so much so that any family they are connected with—first biological, then later adoptive—are killed off. Thus, the three main children in this novel have all suffered family massacres not once, but twice. Gerritsen adds yet another interesting element into the equation by uniting these three characters at a special school, The Evensong Boarding School, for children who have been subjected to major traumas. The school, located in Maine, and away from the Boston locale that grounds the series itself, is the perfect venue for this mystery plot to begin taking on other interesting textures. For those who are knowledgeable about the series, the fact that the Evensong Boarding School is run by the Mephisto Society is already potential cause for concern. Further still, once the school psychologist is found dead, having jumped from a high building and under suspicious circumstances, it becomes clear that that all is not well at the school. Gerritsen also uses enigmatic intercuts that ramp up the tension in the plotting—a narrative device I recall from Silent Girl, the last novel in the series. Readers are pushed to make sense of that narrative against the main plotting and the connections don’t become clear until late into the mystery. Gerritsen also manages to balance the detective plot against the personal trials of its two female protagonists, who are struggling still to rebuild their friendship due to past events. Rizzoli’s parents in particular are the subject of considerable romantic complications, so that subplot gives readers much needed space to breathe, especially because the body count begins to pile up. Even animals are sacrificed in ritualistic killings. Fans of the series and of the mystery genre should be more than happy with this offering.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Last-Die-Rizzoli-Isles-Novel/dp/0345515633/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1367339453&sr=8-1&keywords=Tess+Gerritsen

A Review of Y.S. Lee’s, The Agency 1: A Spy in the House (Candlewick Press, 2010); The Agency 2: The Body at the Tower (Candlewick Press, 2010); The Agency 3: The Traitor in the Tunnel (Candlewick Press, 2012).

In Y.S. Lee’s deliciously fun The Agency series, our heroine is Mary Quinn, a young girl of a questionable background who is saved at the beginning of the novel by the mysterious Agency, who is sort of devoted to the recovery and reformulation of a women’s lives. The Agency is set in the Victorian era and the writer, Y.S. Lee, is no stranger to this period. As our faithful amazon webpage tells us: “Y. S. Lee has a PhD in Victorian literature and culture and says her research inspired her to write A SPY IN THE HOUSE, ‘a totally unrealistic, completely fictitious antidote to the fate that would otherwise swallow a girl like Mary Quinn.’ Y. S. Lee lives in Ontario, Canada.” In this respect, the “agency” enables girls like Mary Quinn a second chance because she lives on the margins of society as a petty thief. The Agency allows Mary to develop other skills, but there’s still limited options: should be become a wife, a governess, or servant; the other unsavory options being bandied about include becoming a prostitute or mistress. So, Lee creates an alternative job trajectory for Mary in this counterfactual, “totally unrealistic,” but nevertheless super fun speculative fiction wherein Mary can become a spy and report upon a particular household as a companion to the daughter of the prime suspect: a one Mr. Thorold, who may or may not be involved with the theft of priceless Indian subcontinent artifacts. At this point, it’s important to pause to say that one of the Lee’s great strengths in the strongly transnational and postcolonial tinge to her collection. Goods and services are being shipped all over the world in the novel, linking the Victorian era London to different nodal points for colonial capitalistic investments. Lee, of course, wants to make sure that even if there isn’t a tried and true marriage plot or courtship plot afloat, that there could be an alternative romance plot as Mary must deal with James Easton, a man who is researching the Thorold’s business dealings to find out whether or not they are as upstanding as they purport to be. James is a worthy counterpart to Mary insofar as he immediately notices how different she is. Her difference is, of course, another aspect that Lee plays with in one of the big surprises mid-way through the novel, which I will refuse to spoil for you. Suffice it to say that Lee’s first book in the Agency is that rare young adult work with a historical texture, a fantasy register, a detective fiction, and a courtship/romance all rolled into one.

[image error]

In the second book in the series, we found our heroine Mary Quinn, going under very deep cover, but this time as a young boy (renamed as Mark Quinn), working at a building site. She’s been dispatched to discover more details concerning the suspicious circumstances of a worker who was found dead, having fallen from the titular tower. Though Mary is game for this job, her overseers at the Agency are wary that such a duty might have psychological ramifications. You see: before Mary was saved and reformed by the Agency, she lived on the streets as a petty thief and hoodlum; she was able to survive in part, often relying upon disguises and passing as a man. Her elders wonder if such a job might trigger unsavory past experiences that could compromise her surveillance activities. Despite this warning, Mary decides that she can do the job, even requesting that she take residence at a working class type facility wherein she would not have the comforts or even the advantages of decent food. Mary’s work is at first not too difficult; she is able to get a job through Harkness, the site engineer, and begins working for the various people below him, which include the imposing and rather spiteful, Keenan, as well as his colleague, Reid. Of course, this series would not be complete with its central romance and fortunately, Lee sees fit to have James Easton, from book 1, return from his travels in India. He’s hired by Harkness to begin an independent assessment of the building site that would be conducted in order to clear him or any of his employees from wrongdoing in the death of Wick. When Mary—as Mark—accidentally bumps into him, James is one of the few to see so easily through the disguise, but he chooses not to break her cover. Indeed, this sequel sees James Easton willing to engage yet another partnership with Mary, presumably of course because of his strong feelings for her. There are of course the occasional issues related to Mary’s complicated identity background, which adds yet another wrinkle to the many dilemmas that arise in the course of the plotting. Lee’s narrative here occasionally flags as it attempts to retain tension throughout, but overall, the book is a spirited, if counterfactual look at an undercover women’s agency during the Victorian era.

In the latest installment, The Traitor in the Tunnel, Mary Quinn is actually undercover in Buckingham Palace! She is dispatched by the Agency in order to find out about a thief that may be pilfering precious items from the royal household. Of course, Lee is never intent to keep the first mystery the only one and soon other issues arise. Most importantly, the Prince of Wales is caught up in a murder scandal in which a close friend might have been killed in an opium den. Interestingly enough, the accused murdered actually may have ties to Mary herself, which ends up complicating and stretching out Mary’s own investments in her sleuthing. I am deliberately being cagey about the potential connection between Mary and the murderer precisely because I’ve attempted to keep a major plot point unspoiled that is revealed from the first book. Finally, Mary’s romance-nemesis, James Easton, returns yet again, as he is contracted to help with the building of a sewer system below London. As Mary soon discovers, the sewer and its connection to Buckingham Palace is a matter of national security. Fans of mystery and of YA historical will again be delighted by this title. Lee clearly has fun with her characters in this spirited third in the series. Fortunately, there are apparently plans for a fourth to appear sometime soon!

Buy the Books Here

http://www.amazon.com/The-Agency-House-Y-S-Lee/dp/076365289X/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1359052764&sr=8-2&keywords=Y.S.+Lee

http://www.amazon.com/The-Agency-Body-Tower/dp/0763656437/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1361139912&sr=8-3&keywords=Y.S.+Lee

http://www.amazon.com/The-Agency-Traitor-Tunnel/dp/0763663441/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1367416563&sr=8-1&keywords=Y.S.+Lee

Published on May 01, 2013 16:47

April 21, 2013

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for April 21, 2013

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for April 21, 2013

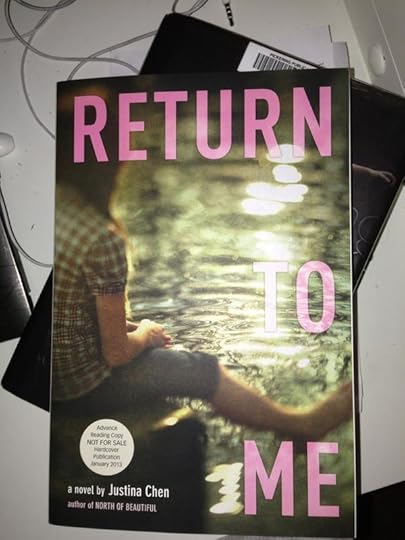

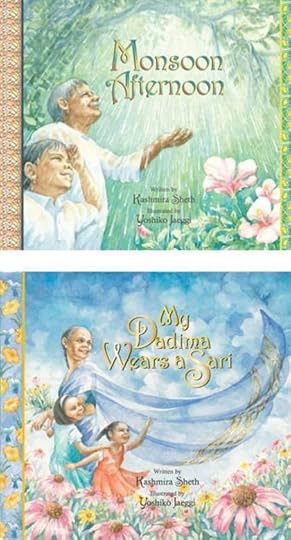

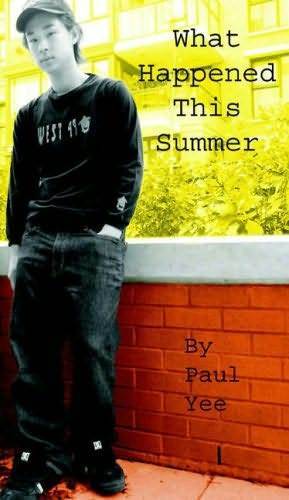

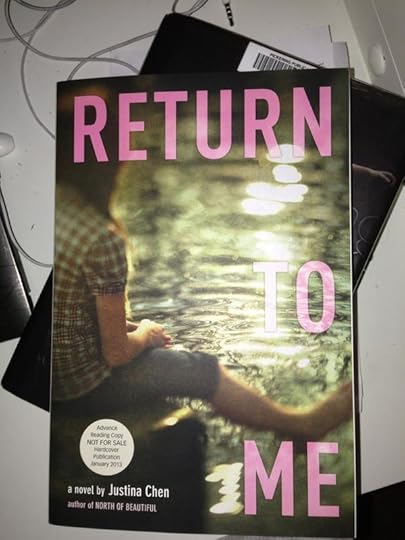

In this post, reviews of Kashmira Sheth’s My Dadima Wears a Sari (illustrated by Yoshiko Jaeggi) (Peachtree Publishers, 2007) and Kashmira Sheth’s Monsoon Afternoon (illustrated by Yoshiko Jaeggi (Peachtree Publishers, 2008); Paul Yee’s What Happened This Summer (Tradewind Books, 2006); Elsie Chapman’s Dualed (Random House Books for Young Readers, 2013); and Justina Chen Headley’s Return to Me (Little Brown Books for Young Readers, 2013).

A Review of Kashmira Sheth’s My Dadima Wears a Sari (illustrated by Yoshiko Jaeggi) (Peachtree Publishers, 2007) and Monsoon Afternoon (illustrated by Yoshiko Jaeggi (Peachtree Publishers, 2008).

It’s been awhile since I reviewed any children’s picture books and I recently had a chance to read the gorgeously illustrated and spirited narratives found in the collaborative publications produced by Yoshiko Jaeggi and Kashmira Sheth out of Peachtree Publishers. Sheth has already been reviewed on Asian American literature fans; please see, for instance, pylduck’s post on Sheth’s (and Pearce’s) most recent offering:

http://asianamlitfans.livejournal.com/141128.html

The picture book form is reliant upon a delicate balance between text and illustration. Jaeggi’s work in both books is absolutely exquisite; it seems as though the pictures have been produced in watercolor, giving both books a kind of dream-like quality that is perhaps perfect for the youthful reader. My Dadima Wears a Sari gives Sheth an opportunity to explore the cross-cultural and transnational dynamics of the titular piece of clothing. Here, the more Americanized young children, presumably of South Asian descent, receive a lesson from their “dadima” (a Gujarati term for grandmother) about the nature and personal history of her saris. As with other books that explore race and ethnicity, these children’s narratives are instructional in their approach, giving young readers the chance to understand what might be to them a foreign culture, but at the same time, Sheth and Jaeggi’s work will appeal to ethnically specific populations as well, who might be dealing with youth undergoing acculturation. This particular book also has a fun addition at the end, showing young readers how a sari can be worn. Whereas My Dadima Wears a Sari takes place the United States, Monsoon Afternoon is set in India. In that story, a young boy asks various members of his family to go outside and play, but everyone seems to be busy except for his grandfather, otherwise known as “dadaji.” The narrative thus reveals their bonding time on the arrival of the monsoon season. Here, the pedagogical conceit appears in the guise of the difference in weather patterns and Sheth does take time to explain the importance of the monsoon to her personal life in an author’s note the surfaces at the conclusion of this picture book.

Buy the Books Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Monsoon-Afternoon-Kashmira-Sheth/dp/1561454559/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8&qid=1364148646&sr=8-4&keywords=kashmira+sheth

http://www.amazon.com/Dadima-Wears-Sari-Kashmira-Sheth/dp/1561453927/ref=sr_1_7?ie=UTF8&qid=1364148646&sr=8-7&keywords=kashmira+sheth

A Review of Paul Yee’s What Happened This Summer (Tradewind Books, 2006).

We reviewed a number of Paul Yee titles on Asian American literature fans, including some of his children’s books and a handful of his young adult titles. Plyduck’s latest review of a Paul Yee title was Ghost Train, posted here:

http://asianamlitfans.livejournal.com/152518.html

What Happened This Summer is part of Yee’s work in the young adult genre; this publication is a curious one insofar as it is not listed as a collection of short stories or a novel per se, though it seems to be marketed as a general fictional work (set primarily in and around Vancouver, Canada). Since characters do recur across the stories, it seems best described as a story cycle or sequence. Because all of the stories are told in the first person perspective and most from the viewpoint of a Chinese Canadian youth, there is a kind of repetitive quality to the work that can detract from the important political contexts that Yee aims to convey. Indeed, the strength of What Happened This Summer is the thematic focus on generational ruptures between parents and their children, the lack of community building among immigrant youth, and the general malaise facing individuals as they struggle to acculturate to a new land and place. Yee is deft at weaving in particular historical and social contexts, including histories of Chinese migration, the continuing tensions among Hong Kong, Taiwan and China, the rise of China as a global economic power, and the ever-present lens of suspicion cast upon Asian immigrants due to emerging viruses from that region (like SARS). The strongest stories show Yee’s attentive consideration of form: one story employs the journal format and enhances the distinctiveness of its teenage narrator. In another, the narrator is studying for the TOEFL exam and finds himself struggling with the proper use of articles and Yee draws attention to the terrain of language as a kind of minefield, especially as certain words become bolded. For those looking for a grittier depiction of Chinese Canadian teenagers, Yee’s What Happened This Summer is certainly a good choice.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/What-Happened-this-Summer-Paul/dp/1896580882/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1363157361&sr=8-1&keywords=what+happened+this+summer

A Review of Elsie Chapman’s Dualed (Random House Books for Young Readers, 2013).