Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 55

October 26, 2013

A Review of Najaf Mazari and Robert Hillman’s The Honey Thief (Viking Adult, 2013).

A Review of Najaf Mazari and Robert Hillman’s The Honey Thief (Viking Adult, 2013).

The first thing I thought about after finishing The Honey Thief was about its marketing: it is labeled as fiction. These stories, clearly passed down orally, have found new form in this co-written collection. Many have a historical and ethnographic edge to them and thus move this work into the realm of nonfiction. Certainly, the last story, “Thoughts on Growing and Eating,” offers up a more autobiographical account (from Mazari’s perspective) of the culture and the cuisine of those from his tribal background (the Hazara). The Hazara call the Afghan highlands their home; they have long suffered from factionalism and conflict among the tribes, as well as the extended wars and incursions incited by foreign powers (such as Russia and now the United States). The collection ends with a series of recipes. I’m not sure if this “recipe appendix” was necessary, even with the dynamic autobiographical perspective offered beforehand. Mazari and Hillman already have a wealth of stories and folktales to draw from, the most compelling of which is the extended story arc of the titular honey chief. In that story, a beekeeper by the name of Ahmad Hussein seeks a new apprentice and finds it in a young man by the name of Abbas. Abbas himself comes to learn the importance not only of beekeeping but also of storytelling. Abbas receives the lengthiest attention in the collection, as he returns at later points, especially in some of the most affecting pieces such as “The Richest Man in Afghanistan” and “The Russian.” Connecting most of the collection is the importance of understanding the Other, however that might be defined. In a land riven by war and violence, Mazari and Hillman’s message can certainly be rationalized not only through the searing impact of these lyrical stories, but also by the richness of a culture threatened with disappearance. My favorite story of the entire collection, “The Snow Leopard,” explores the unexpected friendship that arises between a Jewish man from English named Abraham—some sort of academic photographer—and Mohammed Hussein, a man from the Hazara tribe who takes on the duty of accompanying Abraham (called Dobara in Dari) while he seeks the famed snow leopard that can be found in the region. The entire story explores the futile efforts of these two over the course of many years. Abraham will occasionally return to England and then come back to the Hazarajat region only to fail to find the Snow Leopard. The whole point is of course the many relationships that Abraham will make over his quest and the surprise ending is especially fitting, given the fact that Abraham has come to understand the larger import of his travels. Other stories, such as the tragically sequenced “The Life of Abdul Khaliq” and “The Death of Abdul Khaliq” help dramatize the tribal warfare that takes the lives not of martyrs and family members associated with anyone deemed to be an insurgent. The Honey Thief helps bring up the question of the Western borderlands of Asian American literature and the place of writers like Mazari and Khaled Hosseini.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Honey-Thief...

The first thing I thought about after finishing The Honey Thief was about its marketing: it is labeled as fiction. These stories, clearly passed down orally, have found new form in this co-written collection. Many have a historical and ethnographic edge to them and thus move this work into the realm of nonfiction. Certainly, the last story, “Thoughts on Growing and Eating,” offers up a more autobiographical account (from Mazari’s perspective) of the culture and the cuisine of those from his tribal background (the Hazara). The Hazara call the Afghan highlands their home; they have long suffered from factionalism and conflict among the tribes, as well as the extended wars and incursions incited by foreign powers (such as Russia and now the United States). The collection ends with a series of recipes. I’m not sure if this “recipe appendix” was necessary, even with the dynamic autobiographical perspective offered beforehand. Mazari and Hillman already have a wealth of stories and folktales to draw from, the most compelling of which is the extended story arc of the titular honey chief. In that story, a beekeeper by the name of Ahmad Hussein seeks a new apprentice and finds it in a young man by the name of Abbas. Abbas himself comes to learn the importance not only of beekeeping but also of storytelling. Abbas receives the lengthiest attention in the collection, as he returns at later points, especially in some of the most affecting pieces such as “The Richest Man in Afghanistan” and “The Russian.” Connecting most of the collection is the importance of understanding the Other, however that might be defined. In a land riven by war and violence, Mazari and Hillman’s message can certainly be rationalized not only through the searing impact of these lyrical stories, but also by the richness of a culture threatened with disappearance. My favorite story of the entire collection, “The Snow Leopard,” explores the unexpected friendship that arises between a Jewish man from English named Abraham—some sort of academic photographer—and Mohammed Hussein, a man from the Hazara tribe who takes on the duty of accompanying Abraham (called Dobara in Dari) while he seeks the famed snow leopard that can be found in the region. The entire story explores the futile efforts of these two over the course of many years. Abraham will occasionally return to England and then come back to the Hazarajat region only to fail to find the Snow Leopard. The whole point is of course the many relationships that Abraham will make over his quest and the surprise ending is especially fitting, given the fact that Abraham has come to understand the larger import of his travels. Other stories, such as the tragically sequenced “The Life of Abdul Khaliq” and “The Death of Abdul Khaliq” help dramatize the tribal warfare that takes the lives not of martyrs and family members associated with anyone deemed to be an insurgent. The Honey Thief helps bring up the question of the Western borderlands of Asian American literature and the place of writers like Mazari and Khaled Hosseini.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Honey-Thief...

Published on October 26, 2013 17:37

October 19, 2013

Asian American characters in children's and young adult fiction?

I've been wondering about the presence of Asian American characters in children's and young adult fiction, particularly books not written by Asian American authors. Are any of you regular readers of children's and young adult fiction? There's so much of it out there, so I'm by no means widely read, but the selected books I've read for various reasons unrelated to my interests in writing by Asian Americans have at times surprised me with Asian American characters. Despite the fact that the world of children's and young adult literature remains largely centered on white characters (see my friend's edited collection of essays,

Diversity in Youth Literature

, for some discussions of multicultural representation in the literature), it also seems that there is a concerted effort by some authors to write characters of various racial and ethnic backgrounds into their stories. Although this kind of writing might be superficially multicultural (in the way Bennetton advertisements have been analyzed as simply plopping people of different races onto the page or screen), it is also striking in the way that there are more Asian American characters than I would've expected, especially more complex characters than typical in lots of mainstream television shows and movies.

Here are just a few examples from books I've read recently:Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell flips back and forth between the perspectives of the two title characters. Park is a mixed-race Korean American teen. This book came on my radar because teachers and librarians at a local suburban school district chose it as a summer reading book, and some conservative parents reacted badly against it and had it pulled and the author disinvited from visiting. However, St. Paul Public Library has organized some events around the book and a visit from the author, and they have also chosen the book as their Read Brave book for 2014 (a single book about difficult issues teens face that the library chooses to encourage teens and adults to read and discuss over the course of the year).Everlost by Neal Shusterman is the first book in the Skin Jackers trilogy about children who end up in limbo after sudden deaths. Again, of two main characters, Nick is a mixed-race Japanese American teen. Like in Park, Nick notes how important his Asian features and background are in the way people treat him. Both Rowell and Shusterman make a number of mentions of these characters' different eye shape (sometimes the mentions make me cringe), for example, but there is also a careful way that the authors work hard to show these teens as complex and fully-realized characters with an inner subjectivity.Every Day by David Levithan considers the perspectives of a few teens in the aftermath of 9/11. One of the characters is a Korean American boy who slept through the horrific events of that morning and feels disconnected in many ways from the terror that others in the city felt who were awake and worried throughout that day.The Geography Club by Brent Hartinger is one of the canonical books in LGBT YA fiction (David Levithan's work, especially Boy Meets Boy, is also part of that canon). Although the main character is a white, gay teenage boy, his good friend Min is a Chinese American, bisexual girl.From these examples and a handful of others, I could generalize to say that there is some attention to populating supporting characters in YA fiction with non-white characters and even foregrounding one if there are two main characters. Some of the first books I read for YA readers were LGBT fiction, and I noticed the presence of Asian American secondary characters (best friends) in that subgenre, wondering if Asian American characters presented a particular purpose in that vein. Anyways, I'm just wondering if others have noticed these minor Asian American characters in other youth fiction.....

Here are just a few examples from books I've read recently:Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell flips back and forth between the perspectives of the two title characters. Park is a mixed-race Korean American teen. This book came on my radar because teachers and librarians at a local suburban school district chose it as a summer reading book, and some conservative parents reacted badly against it and had it pulled and the author disinvited from visiting. However, St. Paul Public Library has organized some events around the book and a visit from the author, and they have also chosen the book as their Read Brave book for 2014 (a single book about difficult issues teens face that the library chooses to encourage teens and adults to read and discuss over the course of the year).Everlost by Neal Shusterman is the first book in the Skin Jackers trilogy about children who end up in limbo after sudden deaths. Again, of two main characters, Nick is a mixed-race Japanese American teen. Like in Park, Nick notes how important his Asian features and background are in the way people treat him. Both Rowell and Shusterman make a number of mentions of these characters' different eye shape (sometimes the mentions make me cringe), for example, but there is also a careful way that the authors work hard to show these teens as complex and fully-realized characters with an inner subjectivity.Every Day by David Levithan considers the perspectives of a few teens in the aftermath of 9/11. One of the characters is a Korean American boy who slept through the horrific events of that morning and feels disconnected in many ways from the terror that others in the city felt who were awake and worried throughout that day.The Geography Club by Brent Hartinger is one of the canonical books in LGBT YA fiction (David Levithan's work, especially Boy Meets Boy, is also part of that canon). Although the main character is a white, gay teenage boy, his good friend Min is a Chinese American, bisexual girl.From these examples and a handful of others, I could generalize to say that there is some attention to populating supporting characters in YA fiction with non-white characters and even foregrounding one if there are two main characters. Some of the first books I read for YA readers were LGBT fiction, and I noticed the presence of Asian American secondary characters (best friends) in that subgenre, wondering if Asian American characters presented a particular purpose in that vein. Anyways, I'm just wondering if others have noticed these minor Asian American characters in other youth fiction.....

Published on October 19, 2013 15:26

October 17, 2013

Lan Samantha Chang's All Is Forgotten, Nothing Is Lost

I had the most powerful deja vu while reading Lan Samantha Chang's All Is Forgotten, Nothing Is Lost (W. W. Norton, 2010)... the sense that I had read it before though I only "remembered" a few passages spread throughout the novel. One particular passage from the second part of the novel especially stood out: In it, two of the characters walk to the parking garage after a dinner. I either heard the author read from the book at some point or read an essay that analyzed it (maybe something by

sa_am

?). I'm pretty sure I didn't actually read the novel before because it wasn't in my Goodreads account.... My memory is so bad, though, so I might very well have read it and just not updated my list.

sa_am

?). I'm pretty sure I didn't actually read the novel before because it wasn't in my Goodreads account.... My memory is so bad, though, so I might very well have read it and just not updated my list.

This novel, as stephenhongsohn noted in an earlier post, deviates from Chang's earlier work that focused on Chinese American characters. The central characters in this novel are all ostensibly white or at least racially unmarked in ways that racial minority characters seldom are. (One of few and most distinct physical features described is a character's blue eyes.) The central figure is Roman, who at the beginning of the novel is a graduate creative writing student and poet. The novel unfolds in the three sections--the first takes place in the second and final year of graduate school for Roman; the second jumps ahead a decade or so when Roman has gone on to publish books poetry, win prestigious awards, marry and have a son, and gain tenure at a school in the Midwest where he has taught since his first book; and the third takes place yet another five or ten years later. The novel, then, traces Roman's poetic and personal life as it develops, flourishes, and recedes.

The novel is also very much about poetry, the poetic life, and the teaching of craft (creative writing). I remember when the novel came out a few years ago that there was a slew of articles about how the novel questions the workshop model of creative writing (and the proliferation of MFA programs in the last few decades). Chang is the director of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, one of the most prestigious programs in the country, and it makes a lot of sense that she would explore the idea of whether or not creative and poetic art can be taught.

The characters interestingly seem to sketch out a range of types of writers, with Roman being the one most objectively successful (books published, awards won, tenure gained, etc.) in a particular vein of the professional writer while his graduate school friend Bernard is a foil to his character, a more idealized, old-fashioned type of writer who abjures other work and lives in poverty, secretly working on his long poem but not publishing. Roman's wife, Lucy, was also a graduate school friend, and she mostly leaves behind her creative arts to raise their son. Perhaps the most compelling figure in the novel is the teacher in the first part, the poet Miranda, who is aloof and enigmatic, often devastating in her critiques of students' work in the workshop seminars. One of the moments I loved the most in the novel was when Roman, after having taught creative writing himself for over a decade, reflects on the different expectations students had when he was a student versus his own students. While he and his friends saw their professors as geniuses and all-powerful people (in the novel, he describes the relationship as one of humans to gods, where the students had to sacrifice things to the teachers to gain their whimsical favor), his own students feel entitled to praise of their work and felt that everyone should be published and gain accolades, regardless of any talent, genius, or insight in their work.

I'm curious how much people in the MFA world might still talk about this novel (if they did at all). It might make an interesting novel to read and discuss with creative writing students, who I assume have fairly romanticized ideas about themselves as writers.

sa_am

?). I'm pretty sure I didn't actually read the novel before because it wasn't in my Goodreads account.... My memory is so bad, though, so I might very well have read it and just not updated my list.

sa_am

?). I'm pretty sure I didn't actually read the novel before because it wasn't in my Goodreads account.... My memory is so bad, though, so I might very well have read it and just not updated my list.

This novel, as stephenhongsohn noted in an earlier post, deviates from Chang's earlier work that focused on Chinese American characters. The central characters in this novel are all ostensibly white or at least racially unmarked in ways that racial minority characters seldom are. (One of few and most distinct physical features described is a character's blue eyes.) The central figure is Roman, who at the beginning of the novel is a graduate creative writing student and poet. The novel unfolds in the three sections--the first takes place in the second and final year of graduate school for Roman; the second jumps ahead a decade or so when Roman has gone on to publish books poetry, win prestigious awards, marry and have a son, and gain tenure at a school in the Midwest where he has taught since his first book; and the third takes place yet another five or ten years later. The novel, then, traces Roman's poetic and personal life as it develops, flourishes, and recedes.

The novel is also very much about poetry, the poetic life, and the teaching of craft (creative writing). I remember when the novel came out a few years ago that there was a slew of articles about how the novel questions the workshop model of creative writing (and the proliferation of MFA programs in the last few decades). Chang is the director of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, one of the most prestigious programs in the country, and it makes a lot of sense that she would explore the idea of whether or not creative and poetic art can be taught.

The characters interestingly seem to sketch out a range of types of writers, with Roman being the one most objectively successful (books published, awards won, tenure gained, etc.) in a particular vein of the professional writer while his graduate school friend Bernard is a foil to his character, a more idealized, old-fashioned type of writer who abjures other work and lives in poverty, secretly working on his long poem but not publishing. Roman's wife, Lucy, was also a graduate school friend, and she mostly leaves behind her creative arts to raise their son. Perhaps the most compelling figure in the novel is the teacher in the first part, the poet Miranda, who is aloof and enigmatic, often devastating in her critiques of students' work in the workshop seminars. One of the moments I loved the most in the novel was when Roman, after having taught creative writing himself for over a decade, reflects on the different expectations students had when he was a student versus his own students. While he and his friends saw their professors as geniuses and all-powerful people (in the novel, he describes the relationship as one of humans to gods, where the students had to sacrifice things to the teachers to gain their whimsical favor), his own students feel entitled to praise of their work and felt that everyone should be published and gain accolades, regardless of any talent, genius, or insight in their work.

I'm curious how much people in the MFA world might still talk about this novel (if they did at all). It might make an interesting novel to read and discuss with creative writing students, who I assume have fairly romanticized ideas about themselves as writers.

Published on October 17, 2013 07:15

October 15, 2013

Asian American Literature Fans Megapost for October 15, 2013

Asian American Literature Fans Megapost for October 15, 2013

In this post reviews of: Gary Kamiya’s Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco (Bloomsbury USA, 2013) and Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City (Knopf, 2013); Ji-Li Jiang’s Red Kite, Blue Kite (illustrated by Greg Ruth) (Disney Hyperion, 2013); Leila Rasheed’s Cinders & Sapphires (Disney Hyperion, 2013); Jaspreet Singh’s Helium (Bloomsbury USA, 2013); Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland (Knopf, 2013); Nancy Yi Fan’s Swordbird (HarperCollins Children’s Division, 2007); Sherry Thomas’s The Burning Sky (Balzer & Bray, 2013); Malinda Lo’s Inheritance (Little Brown for Young Readers, 2013).

A Review of Gary Kamiya’s Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco (Bloomsbury USA, 2013) and Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City (Knopf, 2013)

At first, I was disappointed by the fact that Gary Kamiya’s part-memoir, part-history, part-cultural study—titled Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco—did not contain any photographs. I was sort of expecting it to, for whatever reason, and the only visuals that Kamiya’s creative nonfiction relies upon appear as sketches in the headings for each of the 49 chapters. But, I was soon won over by Kamiya’s relentlessly engaged narrative voice and how it comes to look into every nook and cranny to bring to life the City’s many textures and facets. Kamiya doesn’t stray from San Francisco’s long history and includes many citations from noted urban studies scholars and academics; when he discusses the mission system, for instance, it is with the heavy knowledge that the city is undoubtedly linked to the annihilation of American Indian populations. Other chapters are more whimsical in their topics; one focuses on the stairs located in Bernal Heights, another on the counterculture fervor that could be found at Baker Beach. The title is a fitting description of Kamiya’s ardor for the foggy City as rendered through 49 eclectic views.

Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City is certainly less tightly structured that Gary Kamiya’s work, but also stands as a kind of love letter to a city, rendered in part-memoir, part-history, part-cultural study that also does not contain any photographs. Here, I was less expectant of any pictures simply because the title did not seem to evoke that possibility. At the same time, for those who are expecting a more straightforward exploration of a man’s experiences living in one modernizing city, you will not exactly find that here. Chaudhuri is content with a more meditative style and you’ll find him ambling through the city, while providing detailed commentaries on the urbanscape’s historical and ethnographic backdrops. Whereas Kamiya’s creative nonfiction is more syncopated and kinetic, Chauduri’s depiction of Calcutta is more lush and descriptive. The occasionally meandering narrative is perfectly paralleled by the flaneur-esque quality of Chaudhuri’s urban movements. Chapters explore varied topics, including Calcutta’s colonial past, its cuisine (particularly its Chinese and Italian fare), its residents (a spirited chapter on a slightly eccentric upper crust couple known as the Mukherjees). At the heart of this tale is Chaudhuri’s understanding of the political radicalism that portended great things for the cities in its sixties and seventies, a youthful viewpoint that must evolve as Calcutta endures inevitable ebbs and flows.

Buy the Books Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Cool-Gray-City-Love-Francisco/dp/1608199606/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1376764393&sr=8-1&keywords=Gary+Kamiya

http://www.amazon.com/Calcutta-Years-City-Amit-Chaudhuri/dp/0307270246/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1379042292&sr=8-1&keywords=Amit+Chaudhuri

A Review of Ji-Li Jiang’s Red Kite, Blue Kite (illustrated by Greg Ruth) (Disney Hyperion, 2013).

I haven’t reviewed picture books in awhile, but the genre is always fun for me even as an adult reader for the simple fact of visually stunning drawings that always come with a textual narrative. It is, in some sense, a kind of comic book for me. Ji-Li Jiang is also author of a YA book entitled Red Scarf Girl: A Memoir of the Cultural Revolution. Like that memoir, Red Kite, Blue Kite takes its inspiration from the social context of the cultural revolution as well, but unlike the memoir-form, Jiang’s inspiration for this story is one based upon something told to her by a friend. As with other picture books that employ a strongly historical backdrop, Jiang provides a useful explanatory author’s note that engages some of her inspirations for the story. In this case, the story revolves around the family connection between a Chinese man, who is forced into hard labor during the cultural revolution, and his young son. Prior to the cultural revolution, they bond over flying kites; because they live in a crowded city, they must fly kites from rooftops. Later, when the young boy’s father is sent into hard labor, the kite becomes an emblem of their connection, which lasts until they are finally reunited. As with other picture books, closure is emphasized, but this particular story does not shy away from the darker undertones of the cultural revolution. The kites, given their colors (red and blue), seem to suggest a unification between east (communist) and west (capitalism). Young children may not fully understand the social contexts being invoked, but the larger themes will obviously resonate. Ruth has a nice semi-realistic style that works well with the narrative itself.

Buy the Book Here

http://www.amazon.com/Red-Kite-Blue-Ji-li-Jiang/dp/1423127536/ref=sr_1_8?ie=UTF8&qid=1372526774&sr=8-8&keywords=Ji+Li+Jiang

A Review of Leila Rasheed’s Cinders & Sapphires (Disney Hyperion, 2013).

I started reading Leila Rasheed’s Cinders & Sapphires during a particularly grueling time for me personally. It was just what I needed to get my mind out of a melancholic space. This novel is debut of the “At Somerton” series (with another slated for release in 2014) and focuses on an aristocratic family (the Averleys) who are suffering from financial woes during the early 20th century. For younger fans of Downton Abbey, this series is going to be the perfect venue to explore another variation on the mixture and the class between the elites and the domestics. The central perspective is given to Ava Averley, perhaps a slightly more modern-take on the Elizabeth Bennett-type; she believes in women’s suffrage, wants to study at Oxford and falls in love with a buddying young scholar named Ravi Sundaresan. Ravi, being of Indian ancestry, is of course not the ideal match for Ava, so she must keep this romantic intrigue a secret, but there are many other relationship complications to attend to. For instance, Ava’s father has remarried a woman by the name of Fiona, who hails from another upper crust family line (the Templetons). Ava has a new stepsister (the cruel Charlotte) and two stepbrothers (the queer William and the domestic-help loving Michael). Ava and her older sister Georgianna must deal with the new family dynamics, as they prepare to enter London society! Rasheed’s novel is a fun frolic and especially attuned to the political problematics of the period, with discussions concerning women’s liberation and postcolonial independence movements in India. For those who have enjoyed Y.S. Lee’s The Agency series out of Candlewick, this novel would be a natural and fitting reading choice.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Cinders-Sapphires-Somerton-Leila-Rasheed/dp/1423171179/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1373037233&sr=8-1&keywords=Cinders+and+Sapphires

A Review of Jaspreet Singh’s Helium (Bloomsbury USA, 2013).

Jaspreet Singh’s third publication Helium (after Chef and Seventeen Tomatoes: Tales from Kashmir) is all about narrative un/reliability that surrounds a particularly traumatic event. The story is narrated by an individual named Raj who is a professor at Cornell and who returns to India in order to deal with his past. He visits a woman named Nelly, a library archivist, who was once married to Raj’s former professor who was killed in 1984 during a mob protest conceived under retaliatory attacks against Sikhs after the assassination of Indira Gandhi (perpetrated apparently by her Sikh body guards). Raj was present during the attacks and there is the suggestion that he might have done more to protect his professor and perhaps to save his life. In the period following Indira Gandhi’s assassination, the government was necessarily imbricated and implicated in organized mobs against Sikhs; thus, Singh’s novel turns to this painful moment in time and one specific incident in order to explore the tangled nature of complicity and blame. Nelly’s own story is rife with tragedy: the death and disappearance of her own children, and then, the loss of her husband. Thus, Raj’s reunion with Nelly, even though Raj himself was a star student under that professor, is still a painful reminder of the past. Over the course of the novel, Singh makes sure to elaborate upon Raj’s flawed and multifaceted character, exploring Raj’s estranged relationship with his own family, and then the possibility that his own father may have been involved in the pogroms targeting Sikhs. Singh really makes wonderful use of first person narration, reveling in its impressionistic qualities. Interestingly enough, the novel is sort of constructed as a kind of collage, as there are photographs that appear periodically throughout the narrative. I’m not quite sure why they had to be included, but it does give off the sense that the narrative is a kind of fictionalized memoir or scrapbook and gives this work a unique texture. The use of this kind of reflective narrative voice is reminiscent of Kazuo Ishiguro and Chang-rae Lee.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Helium-A-Novel-Jaspreet-Singh/dp/1608199568/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1379791985&sr=8-1&keywords=Jaspreet+Singh

A Review of Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland (Knopf, 2013).

Well, I absolutely adored Unaccustomed Earth and so my expectations for Lahiri’s fourth effort, The Lowland, were perhaps unfairly high. Nevertheless, this novel is one of the best reads, at least in my opinion of 2013. After reading Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta, I had already learned a little bit about the Naxalites and the development of that particular political arena in Calcutta; the rise of the Naxalites appears in tandem with the rise of Communism as a larger global political platform, of course. Lahiri’s novel starts out with two boys, Subhash and Udayan, who grow up and take very different paths in life. Subhash decides to move to the United States to pursue a secondary degree, while Udayan gets caught up in the Naxalite fervor sweeping Calcutta. Udayan will eventually marry a woman named Gauri; she is pregnant with his child when he is killed for being involved in subversive activities. In the wake of Udayan’s death, Subhash returns to Calcutta; he decides that the best course of action is to marry Gauri, take her to the United States, and raise Gauri and Udayan’s child as his own. Gauri, perceiving this route as the only way to any sort of future, assents. By 100 pages in, Lahiri has already set in motion a number of different and complicated familial dynamics. Udayan’s death reverberates through the entire family of course; Subhash’s parents are destroyed by that event and when Subhash and Gauri leave India, there is nothing left for their parents. They slowly disintegrate. While Subhash vainly believes that Gauri will eventually love him, Gauri herself realizes that her love for Udayan was not enough, that Udayan’s political gamesmanship was as much of their relationship as anything else. Subhash will come to love the child, Bela, that he raises as though he were the actual father. Gauri, for her part, wants little to do with motherhood, and begins taking classes in philosophy at the local college. This latter arc leads to the fissures that will later define their American lives. Lahiri’s novel is carefully paced; even the most cataclysmic moments are weaved in with a kind of finesse that makes the reading experience unfold effortlessly. Soon, you’re well into the narrative and you’ll drift into these lives, enraptured by Lahiri’s ability to bring these characters to life.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Lowland-Jhumpa-Lahiri/dp/0307265749/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1379124547&sr=8-1&keywords=Jhumpa+Lahiri

A Review of Nancy Yi Fan’s Swordbird (HarperCollins Children’s Division, 2007).

Nancy Yi Fan’s Swordbird is part of a trilogy that also includes Sword Quest and Sword Mountain. I was interested in reading this title for the backstory. Apparently, the author was only ten when she began writing Swordbird and it was published when she was 14 years old. The novel was inspired by the events of 9/11 and the author’s intention to create a message promoting peace over violent conflict. The story revolves around the growing tensions among groups of woodland birds. The cardinals and the blue jays are involved in a misunderstanding that is leading to conflict between them. They do not realize that a third party is involved: Turnatt, who seekins to construct a malevolent fortress with the labor extracted from slavebirds, is the entity behind the madness and mischief. It is exceedingly impressive that a writer so young was able to create this story; Fan should be especially lauded for her creative use of names and the general structural framework of the story itself, which also includes excerpts from mystical and heretical texts. It is a speculative fiction in which birds can speak and the titular Swordbird may appear to enact swift justice in a method akin to a kind of Christ-figure. The narrative’s rhetoric concerning pacifism may come off a little bit too tidy for older readers, but I have no doubts the novel would engage its target audience (8-12 years old).

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Swordbird-Nancy-Yi-Fan/dp/0061131016/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1367594906&sr=8-2&keywords=Nancy+Yi+Fan

A Review of Sherry Thomas’s The Burning Sky (Balzer & Bray, 2013).

Sherry Thomas’s debut in the paranormal/ fantasy/ urban/ romance/ young adult fiction is The Burning Sky, which follows two main characters: Prince Titus and Iolanthe Seabourne. Thomas is also the author of a number of critically acclaimed romance novels that I have not read (Private Arrangements, Delicious etc). The Burning Sky is part of intended trilogy, apparently the chosen serial form for these kinds of works (and an academic paper probably waiting to happen: why must it be the trilogy besides the fact of making more money?). In the first installment, Iolanthe Seaborne ignores the grave warnings offered to her by her mentor, Master Haywood, an aging man who seems to have lost the support of his local community. Iolanthe decides to repair a light elixir that Haywood destroys in the hopes that she will still get to be a part of a marriage ceremony, but the only way to restore the elixir is to use lightning. Iolanthe being an elemental mage of the third order, common but not rare, is able to call forth lightning, but ends up producing a lightning bolt that almost kills her. This event also ends up calling the attentions of Prince Titus, a major figure in the kingdom of Atlantis, as well as the Inquisitor, a fearsome woman who is a sort of supernatural detective, seeking to root out any possible subversive influences that may be brewing in the region. Cast above the opening fray is someone called Bane, a malevolent mage who holds dominion over all. The production of lighting marks Iolanthe as a mage far more powerful than her third order; indeed we come to discover that Haywood knew all along that Iolanthe held such talents and that her talents would mark her for a perilous maturation. Once Prince Titus gets involved, he is able to whisk her away to another land: that of London, where she cross-dresses and passes as a young schoolmate (alias: Archer Fairfax) of Prince Titus. Indeed, there is but the slightest barrier between these worlds, but it is clear that no one on the human side really has much or any knowledge of this other more fantastical realm. Once the Inquisitor is in pursuit of Iolanthe, the novel moves to a narrative of pursuit. Thus, Prince Titus and Iolanthe must train in order to fend off the coming battle. Iolanthe eventually makes a blood oath (that she at first regrets) with the Prince so that she may eventually free Haywood, who is imprisoned, and part of the oath requires her to try to take down the aforementioned Bane, even if it might mean death for both of them. For his part, the Prince is driven to this quest by the visions of her mother, a powerful seer, who foretells his eventual downfall and early demise. Will the Prince be able to avoid this tragic fate? Will Iolanthe and the Prince come to work as allies rather than enemies? Thomas’s novel answers most questions and sets up some others by the thrilling conclusion. She weaves together some historical elements (set in India’s colonial period, thus not entirely abstracting real world contexts) with the fantasy genre (wyverns and dragons appear) to create a lush fictional world sure to captivate, especially for those looking for something on the more whimsical side.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Burning-Sky-Elemental-Trilogy/dp/0062207296/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1381160797&sr=8-1&keywords=the+burning+sky

A Review of Malinda Lo’s Inheritance (Little Brown for Young Readers, 2013).

Malinda Lo’s Inheritance completes the two book series (following Adaptation) involving Reese Holloway and David Li, as they must contend with the truth of their biological makeup (Lo is also author of Ash and Huntress). For those of you who are not yet spoiled and would like to remain unspoiled, do not read further from this point.

My earlier review of Adaptation did not reveal the major plot point involving the fact that our protagonists were brought back from the brink of death due to the intervention of an alien species known as the Imria. Fusing human DNA with alien DNA, the Imria were able to also introduce new capabilities within Reese and David that ultimately presented the possibility of new evolutionary pathways. In any case, this novel treads similar ground in relation to many of the alien invasion storylines in other works: are the aliens friends or foe? Lo’s unique intervention appears to be in exploring how alien-ness becomes a useful trope to play off against racial and sexual difference. As we come to discover, Reese is not entirely over her feelings for Amber, the Imrian who seemed to betrayed her at the first novel’s conclusion. At the same time, Reese is dating David, so her emotions for Amber present her with a romantic conundrum. Who should Reese date? Complicating matters is the fact that Reese and David have both developed super-powers related to a kind of communal telepathic and empathic consciousness: that is, they are able to discern the feelings of one another in a way that seems akin to the Vulcan mind meld. Thus, David intimately understands that Reese is conflicted, a fact which creates considerable romantic tension and sustains the central romance triange. Lo’s world-building requires her to give much background to the Imrians, who do have many unique characteristics. For instance, they fully embrace various forms of polyamory and further still, offer much more gender fluidity in their culture. Lo’s point here is obviously related to the possibilities that alien species provide her as an imaginary community that scripts more inclusive social formations. The novel seems occasionally weighed down by the need to draw out the romantic tension, but a very action-packed finish brings Inheritance back on track. The Imrians as a species are fascinating enough that you can’t help but have hoped for a third novel that explored alien terrains and human-Imrian diplomatic relationships. Let’s hope that Lo eventually returns to this storyline in order to make it into the trilogy is already so prevalent as the chosen serial form of young adult fictions.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Inheritance-Malinda-Lo/dp/0316198005/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1381790226&sr=8-1&keywords=inheritance+lo

In this post reviews of: Gary Kamiya’s Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco (Bloomsbury USA, 2013) and Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City (Knopf, 2013); Ji-Li Jiang’s Red Kite, Blue Kite (illustrated by Greg Ruth) (Disney Hyperion, 2013); Leila Rasheed’s Cinders & Sapphires (Disney Hyperion, 2013); Jaspreet Singh’s Helium (Bloomsbury USA, 2013); Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland (Knopf, 2013); Nancy Yi Fan’s Swordbird (HarperCollins Children’s Division, 2007); Sherry Thomas’s The Burning Sky (Balzer & Bray, 2013); Malinda Lo’s Inheritance (Little Brown for Young Readers, 2013).

A Review of Gary Kamiya’s Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco (Bloomsbury USA, 2013) and Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City (Knopf, 2013)

At first, I was disappointed by the fact that Gary Kamiya’s part-memoir, part-history, part-cultural study—titled Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco—did not contain any photographs. I was sort of expecting it to, for whatever reason, and the only visuals that Kamiya’s creative nonfiction relies upon appear as sketches in the headings for each of the 49 chapters. But, I was soon won over by Kamiya’s relentlessly engaged narrative voice and how it comes to look into every nook and cranny to bring to life the City’s many textures and facets. Kamiya doesn’t stray from San Francisco’s long history and includes many citations from noted urban studies scholars and academics; when he discusses the mission system, for instance, it is with the heavy knowledge that the city is undoubtedly linked to the annihilation of American Indian populations. Other chapters are more whimsical in their topics; one focuses on the stairs located in Bernal Heights, another on the counterculture fervor that could be found at Baker Beach. The title is a fitting description of Kamiya’s ardor for the foggy City as rendered through 49 eclectic views.

Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City is certainly less tightly structured that Gary Kamiya’s work, but also stands as a kind of love letter to a city, rendered in part-memoir, part-history, part-cultural study that also does not contain any photographs. Here, I was less expectant of any pictures simply because the title did not seem to evoke that possibility. At the same time, for those who are expecting a more straightforward exploration of a man’s experiences living in one modernizing city, you will not exactly find that here. Chaudhuri is content with a more meditative style and you’ll find him ambling through the city, while providing detailed commentaries on the urbanscape’s historical and ethnographic backdrops. Whereas Kamiya’s creative nonfiction is more syncopated and kinetic, Chauduri’s depiction of Calcutta is more lush and descriptive. The occasionally meandering narrative is perfectly paralleled by the flaneur-esque quality of Chaudhuri’s urban movements. Chapters explore varied topics, including Calcutta’s colonial past, its cuisine (particularly its Chinese and Italian fare), its residents (a spirited chapter on a slightly eccentric upper crust couple known as the Mukherjees). At the heart of this tale is Chaudhuri’s understanding of the political radicalism that portended great things for the cities in its sixties and seventies, a youthful viewpoint that must evolve as Calcutta endures inevitable ebbs and flows.

Buy the Books Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Cool-Gray-City-Love-Francisco/dp/1608199606/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1376764393&sr=8-1&keywords=Gary+Kamiya

http://www.amazon.com/Calcutta-Years-City-Amit-Chaudhuri/dp/0307270246/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1379042292&sr=8-1&keywords=Amit+Chaudhuri

A Review of Ji-Li Jiang’s Red Kite, Blue Kite (illustrated by Greg Ruth) (Disney Hyperion, 2013).

I haven’t reviewed picture books in awhile, but the genre is always fun for me even as an adult reader for the simple fact of visually stunning drawings that always come with a textual narrative. It is, in some sense, a kind of comic book for me. Ji-Li Jiang is also author of a YA book entitled Red Scarf Girl: A Memoir of the Cultural Revolution. Like that memoir, Red Kite, Blue Kite takes its inspiration from the social context of the cultural revolution as well, but unlike the memoir-form, Jiang’s inspiration for this story is one based upon something told to her by a friend. As with other picture books that employ a strongly historical backdrop, Jiang provides a useful explanatory author’s note that engages some of her inspirations for the story. In this case, the story revolves around the family connection between a Chinese man, who is forced into hard labor during the cultural revolution, and his young son. Prior to the cultural revolution, they bond over flying kites; because they live in a crowded city, they must fly kites from rooftops. Later, when the young boy’s father is sent into hard labor, the kite becomes an emblem of their connection, which lasts until they are finally reunited. As with other picture books, closure is emphasized, but this particular story does not shy away from the darker undertones of the cultural revolution. The kites, given their colors (red and blue), seem to suggest a unification between east (communist) and west (capitalism). Young children may not fully understand the social contexts being invoked, but the larger themes will obviously resonate. Ruth has a nice semi-realistic style that works well with the narrative itself.

Buy the Book Here

http://www.amazon.com/Red-Kite-Blue-Ji-li-Jiang/dp/1423127536/ref=sr_1_8?ie=UTF8&qid=1372526774&sr=8-8&keywords=Ji+Li+Jiang

A Review of Leila Rasheed’s Cinders & Sapphires (Disney Hyperion, 2013).

I started reading Leila Rasheed’s Cinders & Sapphires during a particularly grueling time for me personally. It was just what I needed to get my mind out of a melancholic space. This novel is debut of the “At Somerton” series (with another slated for release in 2014) and focuses on an aristocratic family (the Averleys) who are suffering from financial woes during the early 20th century. For younger fans of Downton Abbey, this series is going to be the perfect venue to explore another variation on the mixture and the class between the elites and the domestics. The central perspective is given to Ava Averley, perhaps a slightly more modern-take on the Elizabeth Bennett-type; she believes in women’s suffrage, wants to study at Oxford and falls in love with a buddying young scholar named Ravi Sundaresan. Ravi, being of Indian ancestry, is of course not the ideal match for Ava, so she must keep this romantic intrigue a secret, but there are many other relationship complications to attend to. For instance, Ava’s father has remarried a woman by the name of Fiona, who hails from another upper crust family line (the Templetons). Ava has a new stepsister (the cruel Charlotte) and two stepbrothers (the queer William and the domestic-help loving Michael). Ava and her older sister Georgianna must deal with the new family dynamics, as they prepare to enter London society! Rasheed’s novel is a fun frolic and especially attuned to the political problematics of the period, with discussions concerning women’s liberation and postcolonial independence movements in India. For those who have enjoyed Y.S. Lee’s The Agency series out of Candlewick, this novel would be a natural and fitting reading choice.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Cinders-Sapphires-Somerton-Leila-Rasheed/dp/1423171179/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1373037233&sr=8-1&keywords=Cinders+and+Sapphires

A Review of Jaspreet Singh’s Helium (Bloomsbury USA, 2013).

Jaspreet Singh’s third publication Helium (after Chef and Seventeen Tomatoes: Tales from Kashmir) is all about narrative un/reliability that surrounds a particularly traumatic event. The story is narrated by an individual named Raj who is a professor at Cornell and who returns to India in order to deal with his past. He visits a woman named Nelly, a library archivist, who was once married to Raj’s former professor who was killed in 1984 during a mob protest conceived under retaliatory attacks against Sikhs after the assassination of Indira Gandhi (perpetrated apparently by her Sikh body guards). Raj was present during the attacks and there is the suggestion that he might have done more to protect his professor and perhaps to save his life. In the period following Indira Gandhi’s assassination, the government was necessarily imbricated and implicated in organized mobs against Sikhs; thus, Singh’s novel turns to this painful moment in time and one specific incident in order to explore the tangled nature of complicity and blame. Nelly’s own story is rife with tragedy: the death and disappearance of her own children, and then, the loss of her husband. Thus, Raj’s reunion with Nelly, even though Raj himself was a star student under that professor, is still a painful reminder of the past. Over the course of the novel, Singh makes sure to elaborate upon Raj’s flawed and multifaceted character, exploring Raj’s estranged relationship with his own family, and then the possibility that his own father may have been involved in the pogroms targeting Sikhs. Singh really makes wonderful use of first person narration, reveling in its impressionistic qualities. Interestingly enough, the novel is sort of constructed as a kind of collage, as there are photographs that appear periodically throughout the narrative. I’m not quite sure why they had to be included, but it does give off the sense that the narrative is a kind of fictionalized memoir or scrapbook and gives this work a unique texture. The use of this kind of reflective narrative voice is reminiscent of Kazuo Ishiguro and Chang-rae Lee.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Helium-A-Novel-Jaspreet-Singh/dp/1608199568/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1379791985&sr=8-1&keywords=Jaspreet+Singh

A Review of Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland (Knopf, 2013).

Well, I absolutely adored Unaccustomed Earth and so my expectations for Lahiri’s fourth effort, The Lowland, were perhaps unfairly high. Nevertheless, this novel is one of the best reads, at least in my opinion of 2013. After reading Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta, I had already learned a little bit about the Naxalites and the development of that particular political arena in Calcutta; the rise of the Naxalites appears in tandem with the rise of Communism as a larger global political platform, of course. Lahiri’s novel starts out with two boys, Subhash and Udayan, who grow up and take very different paths in life. Subhash decides to move to the United States to pursue a secondary degree, while Udayan gets caught up in the Naxalite fervor sweeping Calcutta. Udayan will eventually marry a woman named Gauri; she is pregnant with his child when he is killed for being involved in subversive activities. In the wake of Udayan’s death, Subhash returns to Calcutta; he decides that the best course of action is to marry Gauri, take her to the United States, and raise Gauri and Udayan’s child as his own. Gauri, perceiving this route as the only way to any sort of future, assents. By 100 pages in, Lahiri has already set in motion a number of different and complicated familial dynamics. Udayan’s death reverberates through the entire family of course; Subhash’s parents are destroyed by that event and when Subhash and Gauri leave India, there is nothing left for their parents. They slowly disintegrate. While Subhash vainly believes that Gauri will eventually love him, Gauri herself realizes that her love for Udayan was not enough, that Udayan’s political gamesmanship was as much of their relationship as anything else. Subhash will come to love the child, Bela, that he raises as though he were the actual father. Gauri, for her part, wants little to do with motherhood, and begins taking classes in philosophy at the local college. This latter arc leads to the fissures that will later define their American lives. Lahiri’s novel is carefully paced; even the most cataclysmic moments are weaved in with a kind of finesse that makes the reading experience unfold effortlessly. Soon, you’re well into the narrative and you’ll drift into these lives, enraptured by Lahiri’s ability to bring these characters to life.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Lowland-Jhumpa-Lahiri/dp/0307265749/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1379124547&sr=8-1&keywords=Jhumpa+Lahiri

A Review of Nancy Yi Fan’s Swordbird (HarperCollins Children’s Division, 2007).

Nancy Yi Fan’s Swordbird is part of a trilogy that also includes Sword Quest and Sword Mountain. I was interested in reading this title for the backstory. Apparently, the author was only ten when she began writing Swordbird and it was published when she was 14 years old. The novel was inspired by the events of 9/11 and the author’s intention to create a message promoting peace over violent conflict. The story revolves around the growing tensions among groups of woodland birds. The cardinals and the blue jays are involved in a misunderstanding that is leading to conflict between them. They do not realize that a third party is involved: Turnatt, who seekins to construct a malevolent fortress with the labor extracted from slavebirds, is the entity behind the madness and mischief. It is exceedingly impressive that a writer so young was able to create this story; Fan should be especially lauded for her creative use of names and the general structural framework of the story itself, which also includes excerpts from mystical and heretical texts. It is a speculative fiction in which birds can speak and the titular Swordbird may appear to enact swift justice in a method akin to a kind of Christ-figure. The narrative’s rhetoric concerning pacifism may come off a little bit too tidy for older readers, but I have no doubts the novel would engage its target audience (8-12 years old).

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Swordbird-Nancy-Yi-Fan/dp/0061131016/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1367594906&sr=8-2&keywords=Nancy+Yi+Fan

A Review of Sherry Thomas’s The Burning Sky (Balzer & Bray, 2013).

Sherry Thomas’s debut in the paranormal/ fantasy/ urban/ romance/ young adult fiction is The Burning Sky, which follows two main characters: Prince Titus and Iolanthe Seabourne. Thomas is also the author of a number of critically acclaimed romance novels that I have not read (Private Arrangements, Delicious etc). The Burning Sky is part of intended trilogy, apparently the chosen serial form for these kinds of works (and an academic paper probably waiting to happen: why must it be the trilogy besides the fact of making more money?). In the first installment, Iolanthe Seaborne ignores the grave warnings offered to her by her mentor, Master Haywood, an aging man who seems to have lost the support of his local community. Iolanthe decides to repair a light elixir that Haywood destroys in the hopes that she will still get to be a part of a marriage ceremony, but the only way to restore the elixir is to use lightning. Iolanthe being an elemental mage of the third order, common but not rare, is able to call forth lightning, but ends up producing a lightning bolt that almost kills her. This event also ends up calling the attentions of Prince Titus, a major figure in the kingdom of Atlantis, as well as the Inquisitor, a fearsome woman who is a sort of supernatural detective, seeking to root out any possible subversive influences that may be brewing in the region. Cast above the opening fray is someone called Bane, a malevolent mage who holds dominion over all. The production of lighting marks Iolanthe as a mage far more powerful than her third order; indeed we come to discover that Haywood knew all along that Iolanthe held such talents and that her talents would mark her for a perilous maturation. Once Prince Titus gets involved, he is able to whisk her away to another land: that of London, where she cross-dresses and passes as a young schoolmate (alias: Archer Fairfax) of Prince Titus. Indeed, there is but the slightest barrier between these worlds, but it is clear that no one on the human side really has much or any knowledge of this other more fantastical realm. Once the Inquisitor is in pursuit of Iolanthe, the novel moves to a narrative of pursuit. Thus, Prince Titus and Iolanthe must train in order to fend off the coming battle. Iolanthe eventually makes a blood oath (that she at first regrets) with the Prince so that she may eventually free Haywood, who is imprisoned, and part of the oath requires her to try to take down the aforementioned Bane, even if it might mean death for both of them. For his part, the Prince is driven to this quest by the visions of her mother, a powerful seer, who foretells his eventual downfall and early demise. Will the Prince be able to avoid this tragic fate? Will Iolanthe and the Prince come to work as allies rather than enemies? Thomas’s novel answers most questions and sets up some others by the thrilling conclusion. She weaves together some historical elements (set in India’s colonial period, thus not entirely abstracting real world contexts) with the fantasy genre (wyverns and dragons appear) to create a lush fictional world sure to captivate, especially for those looking for something on the more whimsical side.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Burning-Sky-Elemental-Trilogy/dp/0062207296/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1381160797&sr=8-1&keywords=the+burning+sky

A Review of Malinda Lo’s Inheritance (Little Brown for Young Readers, 2013).

Malinda Lo’s Inheritance completes the two book series (following Adaptation) involving Reese Holloway and David Li, as they must contend with the truth of their biological makeup (Lo is also author of Ash and Huntress). For those of you who are not yet spoiled and would like to remain unspoiled, do not read further from this point.

My earlier review of Adaptation did not reveal the major plot point involving the fact that our protagonists were brought back from the brink of death due to the intervention of an alien species known as the Imria. Fusing human DNA with alien DNA, the Imria were able to also introduce new capabilities within Reese and David that ultimately presented the possibility of new evolutionary pathways. In any case, this novel treads similar ground in relation to many of the alien invasion storylines in other works: are the aliens friends or foe? Lo’s unique intervention appears to be in exploring how alien-ness becomes a useful trope to play off against racial and sexual difference. As we come to discover, Reese is not entirely over her feelings for Amber, the Imrian who seemed to betrayed her at the first novel’s conclusion. At the same time, Reese is dating David, so her emotions for Amber present her with a romantic conundrum. Who should Reese date? Complicating matters is the fact that Reese and David have both developed super-powers related to a kind of communal telepathic and empathic consciousness: that is, they are able to discern the feelings of one another in a way that seems akin to the Vulcan mind meld. Thus, David intimately understands that Reese is conflicted, a fact which creates considerable romantic tension and sustains the central romance triange. Lo’s world-building requires her to give much background to the Imrians, who do have many unique characteristics. For instance, they fully embrace various forms of polyamory and further still, offer much more gender fluidity in their culture. Lo’s point here is obviously related to the possibilities that alien species provide her as an imaginary community that scripts more inclusive social formations. The novel seems occasionally weighed down by the need to draw out the romantic tension, but a very action-packed finish brings Inheritance back on track. The Imrians as a species are fascinating enough that you can’t help but have hoped for a third novel that explored alien terrains and human-Imrian diplomatic relationships. Let’s hope that Lo eventually returns to this storyline in order to make it into the trilogy is already so prevalent as the chosen serial form of young adult fictions.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Inheritance-Malinda-Lo/dp/0316198005/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1381790226&sr=8-1&keywords=inheritance+lo

Published on October 15, 2013 23:17

September 28, 2013

Jon Pineda's Birthmark

Accidentally posed this to my personal journal instead of here....

I finally got around to reading Jon Pineda's debut collection of poems Birthmark (Crab Orchard Review & Southern Illinois University Press, 2004) after reading his second collection The Translator's Diary , his memoir Sleep in Me , and a young adult novel Apology . Birthmark was published as part of the Crab Orchard Poetry Series.

Thematically, the poems in this collection focus often on the father–son relationship, examining childhood memories in light of a later estrangement. A few poems mention the sister injured and forever changed in a car accident, and other poems touch on experiences of being a new father to an infant. One thing I found interesting in this collection was that some poems are in the third person point of view though seemingly still working with the poet's direct experience. This estrangement seems necessary and important, contrasting with other poems in the first person point of view. For example, a section of the poem, "Memory in the Shape of a Swimming Lesson," begins:

I finally got around to reading Jon Pineda's debut collection of poems Birthmark (Crab Orchard Review & Southern Illinois University Press, 2004) after reading his second collection The Translator's Diary , his memoir Sleep in Me , and a young adult novel Apology . Birthmark was published as part of the Crab Orchard Poetry Series.

Thematically, the poems in this collection focus often on the father–son relationship, examining childhood memories in light of a later estrangement. A few poems mention the sister injured and forever changed in a car accident, and other poems touch on experiences of being a new father to an infant. One thing I found interesting in this collection was that some poems are in the third person point of view though seemingly still working with the poet's direct experience. This estrangement seems necessary and important, contrasting with other poems in the first person point of view. For example, a section of the poem, "Memory in the Shape of a Swimming Lesson," begins:

The boy understands the word mestizo. It means "half-breed,"The poem continues a couple of lines later,

not full Filipino. It is a word they use at parties

& touch his hair. They speak to him in Tagalog. He knows

it is the language his father speaks on the phone, or under his breath

when he is angry. . . .

It will mark his life. Years later, when the father leaves the family,The distancing of the speaker of the poem in time and in point of view suggests both an inability to address certain issues directly and the possibility of seeing individual experience as something belonging to others as well.

the boy forgets these words. They become, like the edge of the pool,

something he struggles to reach.

Published on September 28, 2013 12:14

September 21, 2013

Gene Luen Yang's Boxers & Saints

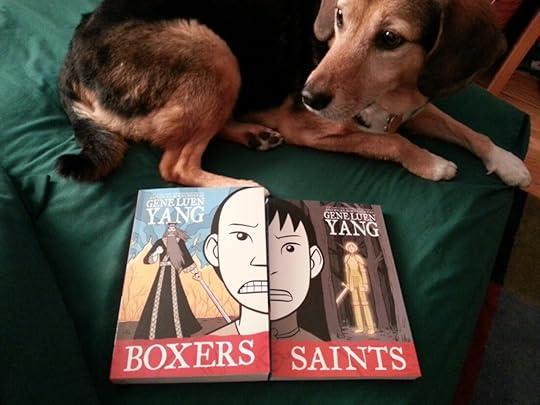

This week, the National Book Foundation announced that Gene Luen Yang's two-volume graphic novel Boxers & Saints (First Second Books, 2013) has made their National Book Awards longlist for Young People's Literature.

Obligatory side-by-side picture of the two volumes.

We've reviewed a handful of Yang's graphic novels and collaborations here at asianamlitfans (see our review catalog for a list of links), and I'm excited to say that these latest books are as funny, touching, thoughtful, and informative as some of his earlier work. I'd been eagerly awaiting a new graphic novel that is both written and illustrated by Yang since he'd worked with a few illustrators for his last few publications. (I seem to recall hearing him say at somewhere that it takes him a very long time to do his own illustrations, so he happily collaborates with others on that aspect of his creative work.) I really love his illustrations in their simplicity yet precise details.

The first volume, Boxers, is the more substantial one, and it takes the perspective of Little Bao, a boy who loves Chinese opera and grows up to lead the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist, a group of Chinese people who fight against imperialist and missionary forces in China. Boxers is historical fiction, an imaginative (even magical realist) telling of the Boxer Rebellion, which involved groups of Chinese people who fought against foreign influences in a particularly bloody chapter of modern Chinese history. In Boxers, Little Bao grows up and sees how Christian missionaries with their Chinese converts trample on villagers, taking food and lives with impunity. He learns kung fu from a man, Red Lantern, who passes through his town. When Red Lantern goes off with a small group of men to fight foreigners, Little Bao tries to follow but is instead sent by Red Lantern to learn more from Master Big Belly, including how to channel a god in his fighting. He passes this skill on to his brothers and others in his village.

The story takes Little Bao through the countryside and some Christian strongholds all the way to Peking where the Chinese Empress holds little real power against the foreign diplomats. There is a romance plot for Little Bao along the way, and Yang raises some interesting questions about the corruption of Christian missionaries and the Chinese Christians as well as the pernicious influence of power-hungry European dignitaries. Yang does not hold back in painting foreigners in a very negative light, sticking with Little Bao's perspective closely throughout the volume. One thing that is interesting is how frequently Yang uses epithets for white men (foreign devils, hairy ones, etc.) as well as for Chinese Christians (secondary devils).

The second volume, Saints, turns to the perspective of a secondary character, Vibiana, who shows up briefly a couple of times in Boxers. Vibiana is the self-chosen name of a girl who grew up the only surviving child in a family, and the grief of her grandfather and parents over the loss of their previous children lead them to treat her poorly. Indeed, they don't even give her a name but simply call her Four-Girl in reference to the fact that she is the fourth child and to the Chinese superstition that the number four is a bad luck number because the word is a homonym for death. Four-Girl finds escape in the house of an acupuncturist who turns out to be Chinese Christian. She starts visiting him to listen to his Bible stories, first just to escape her errands and the abuse she suffered at home as well as to eat his wife's cookies. But eventually, she sees that Christianity offers her a chance to be reborn and to live with different values. The magical realist part of her story comes with her visions of Joan of Arc, and they both share a sense of being called by God to fight for Christianity as women in patriarchal worlds.

These volumes are amazing, and I hope Yang wins the National Book Award for them! The narratives in these books are multilayered, connecting historical events to individual lives, romance, coming of age stories, Chinese myths, and a healthy dose of humor. I'm sure people will have plenty to say about these books in the coming years, and these texts will provide much content for classrooms to explore, from the historical events to the Chinese myths. While the books do not really have any content set in the United States, they are the perspective of an Asian American on Chinese history. In particular, I find it interesting that Yang, who is Catholic, has turned to this particular historical moment to explore the tensions of Chinese and Christian identities.

Obligatory side-by-side picture of the two volumes.

We've reviewed a handful of Yang's graphic novels and collaborations here at asianamlitfans (see our review catalog for a list of links), and I'm excited to say that these latest books are as funny, touching, thoughtful, and informative as some of his earlier work. I'd been eagerly awaiting a new graphic novel that is both written and illustrated by Yang since he'd worked with a few illustrators for his last few publications. (I seem to recall hearing him say at somewhere that it takes him a very long time to do his own illustrations, so he happily collaborates with others on that aspect of his creative work.) I really love his illustrations in their simplicity yet precise details.

The first volume, Boxers, is the more substantial one, and it takes the perspective of Little Bao, a boy who loves Chinese opera and grows up to lead the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist, a group of Chinese people who fight against imperialist and missionary forces in China. Boxers is historical fiction, an imaginative (even magical realist) telling of the Boxer Rebellion, which involved groups of Chinese people who fought against foreign influences in a particularly bloody chapter of modern Chinese history. In Boxers, Little Bao grows up and sees how Christian missionaries with their Chinese converts trample on villagers, taking food and lives with impunity. He learns kung fu from a man, Red Lantern, who passes through his town. When Red Lantern goes off with a small group of men to fight foreigners, Little Bao tries to follow but is instead sent by Red Lantern to learn more from Master Big Belly, including how to channel a god in his fighting. He passes this skill on to his brothers and others in his village.

The story takes Little Bao through the countryside and some Christian strongholds all the way to Peking where the Chinese Empress holds little real power against the foreign diplomats. There is a romance plot for Little Bao along the way, and Yang raises some interesting questions about the corruption of Christian missionaries and the Chinese Christians as well as the pernicious influence of power-hungry European dignitaries. Yang does not hold back in painting foreigners in a very negative light, sticking with Little Bao's perspective closely throughout the volume. One thing that is interesting is how frequently Yang uses epithets for white men (foreign devils, hairy ones, etc.) as well as for Chinese Christians (secondary devils).

The second volume, Saints, turns to the perspective of a secondary character, Vibiana, who shows up briefly a couple of times in Boxers. Vibiana is the self-chosen name of a girl who grew up the only surviving child in a family, and the grief of her grandfather and parents over the loss of their previous children lead them to treat her poorly. Indeed, they don't even give her a name but simply call her Four-Girl in reference to the fact that she is the fourth child and to the Chinese superstition that the number four is a bad luck number because the word is a homonym for death. Four-Girl finds escape in the house of an acupuncturist who turns out to be Chinese Christian. She starts visiting him to listen to his Bible stories, first just to escape her errands and the abuse she suffered at home as well as to eat his wife's cookies. But eventually, she sees that Christianity offers her a chance to be reborn and to live with different values. The magical realist part of her story comes with her visions of Joan of Arc, and they both share a sense of being called by God to fight for Christianity as women in patriarchal worlds.

These volumes are amazing, and I hope Yang wins the National Book Award for them! The narratives in these books are multilayered, connecting historical events to individual lives, romance, coming of age stories, Chinese myths, and a healthy dose of humor. I'm sure people will have plenty to say about these books in the coming years, and these texts will provide much content for classrooms to explore, from the historical events to the Chinese myths. While the books do not really have any content set in the United States, they are the perspective of an Asian American on Chinese history. In particular, I find it interesting that Yang, who is Catholic, has turned to this particular historical moment to explore the tensions of Chinese and Christian identities.

Published on September 21, 2013 05:40

September 15, 2013

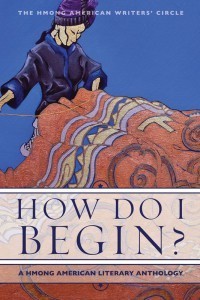

How Do I Begin? A Hmong American Literary Anthology

The Hmong American Writers' Circle, a group based in Fresno, California, pulled together some wonderful poems, short stories, creative nonfiction, and visual art for How Do I Begin? A Hmong American Literary Anthology (Heyday Books, 2011). The book features work by Hmong American writers as well as by a couple of other writers whose experiences have intertwined their lives with those of Hmong communities in the United States. There are a few writers whose work also appeared in the anthology Bamboo Among the Oaks: Contemporary Writing by Hmong Americans (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002).

The book has a stunning cover image adapted from a painting by Seexeng Lee titled "Hmong Woman Sewing a Paj Ntaub," and a full-color insert in the middle of the book includes a couple more images by the artist as well as a selection of paintings and photographs by Boon Ma Yang and Mary Yang.

Before each writer's work, there appears a short autobiographical statement and a photograph of the author. The statement provides the author's perspective on how being Hmong American impacts his or her writing. The responses the authors provides ranges from comments about ethnic identity being mostly incidental to ethnic identity infusing everything. Taken as a whole, the collection of statements provides some interesting material for considering the perennial question of what it means to be an ethnic writer while also addressing the specificity of Hmong American identity. One of the most thoughtful statements, in my mind, is May Lee-Yang's paragraph in which she notes that she writes for "Hmong Americans who are bilingual" rather than a general audience because: "This shift from creating a world where I exist to re-contextualizing my world for non-Hmong people is, I think, indicative of an underlying attempt to shift the paradigm of power."

In an introduction to the volume, Burlee Vang, founder of the Hmong American Writers' Circle, chronicles his own journey as a writer as well as the origins of the Hmong American Writers' Circle in Fresno. He explains how important it was for him and other Hmong American writers to find each other and to establish their presence in the community.

Some of the poems and stories touch on the history of Hmong refugees fleeing Southeast Asia to arrive in the United States. Many of the writings are more from a younger generation, though--not the perspective of refugees themselves but rather their children who either were born in the United States or were too young to remember much of the refugee camps or life in Southeast Asia (primarily Laos or Thailand). A number of the pieces in the collection seem to deal with gender roles in Hmong families, with both men and women writing about the expectations placed upon women--mothers, daughters, and daughters-in-law--to act and serve men in particular ways. There is, however, throughout the writings a strong sense of the importance of family and relationships. The piece that stands out for me is a short nonfiction essay by Ying Thao, whose autobiographical statement is the only one that identifies a Hmong GLBT perspective. Thao's essay explores the silences and difficulties of a relationship with an older brother who explicitly rejected him when he came out to his family.

Incidentally, I really love this anthology's publisher, Heyday Books, which is a small press based in Berkeley that specializes in books about California. I have in mind a collection of essays about multiethnic, transnational histories at the nexus of Contra Costa County (where I grew up) that, if I ever write them, I may send to them in the future for possible publication.

The book has a stunning cover image adapted from a painting by Seexeng Lee titled "Hmong Woman Sewing a Paj Ntaub," and a full-color insert in the middle of the book includes a couple more images by the artist as well as a selection of paintings and photographs by Boon Ma Yang and Mary Yang.

Before each writer's work, there appears a short autobiographical statement and a photograph of the author. The statement provides the author's perspective on how being Hmong American impacts his or her writing. The responses the authors provides ranges from comments about ethnic identity being mostly incidental to ethnic identity infusing everything. Taken as a whole, the collection of statements provides some interesting material for considering the perennial question of what it means to be an ethnic writer while also addressing the specificity of Hmong American identity. One of the most thoughtful statements, in my mind, is May Lee-Yang's paragraph in which she notes that she writes for "Hmong Americans who are bilingual" rather than a general audience because: "This shift from creating a world where I exist to re-contextualizing my world for non-Hmong people is, I think, indicative of an underlying attempt to shift the paradigm of power."

In an introduction to the volume, Burlee Vang, founder of the Hmong American Writers' Circle, chronicles his own journey as a writer as well as the origins of the Hmong American Writers' Circle in Fresno. He explains how important it was for him and other Hmong American writers to find each other and to establish their presence in the community.