Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 48

March 23, 2016

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for March 23 2016

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for March 23 2016

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews of: Kendare Blake’s Ungodly (TorTeen, 2015); Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air (Random House, 2016); Anne Opotowsky (Author) and Aya Morton’s (Illustrator) His Dream of Skyland (Walled City Trilogy, Part 1) (Gestalt Publishing, 2011); Quan Barry’s She Weeps Each Time You’re Born (Pantheon 2015).

A Review of Kendare Blake’s Ungodly (TorTeen, 2015).

The final installment of Kendare Blake’s Goddess War series appears here with Ungodly. We’ll use B&N’s website as always for our synopsis: “As ancient immortals are left reeling, a modern Athena and Hermes search the world for answers in Ungodly, the final Goddess War novel by Kendare Blake, the acclaimed author of Anna Dressed in Blood. For the Goddess of Wisdom, what Athena didn't know could fill a book. That's what Ares said. So she was wrong about some things. So the assault on Olympus left them beaten and scattered and possibly dead. So they have to fight the Fates themselves, who, it turns out, are the source of the gods' illness. And sure, Athena is stuck in the underworld, holding the body of the only hero she has ever loved. But Hermes is still topside, trying to power up Andie and Henry before he runs out of time and dies, or the Fates arrive to eat their faces. And Cassandra is up there somewhere too. On a quest for death. With the god of death. Just because things haven't gone exactly according to plan, it doesn't mean they've lost. They've only mostly lost. And there's a big difference.” As followers of this series already know: gods and heroes are reincarnated time and time again in Blake’s version of the storyworld. Cassandra takes top billing, as she is tasked to be the destroyer of gods. By the third book, Cassandra is angry because her paramour, Apollo, is killed. She is able to kill Hera at the end of the second book (and spoilers are forthcoming) but other antagonists still survive, including Ares and Aphrodite. The third book sees some alliances shift and the parties scattered. Athena must team up with Ares and Aphrodite in the Underworld, especially when Ares is able to use some quick wits to save Athena’s mortal love Odysseus. Hermes is hanging out with Henry (Hector) and Andie (Adromache), while they figure out how to defeat Achilles, who is now teamed up with the book’s major big bad The Three Fates (the Moirae). Finally, Cassandra and Calypso want to find out where Hades is, but first they have to travel to Los Angeles to find Thanatos, who will be sure to have useful information. This final installment is no doubt the strongest of all three books because Blake knows that she has to bring the storylines together. The first two suffered from the inevitable peaks and troughs that come with stretching out a plot over three books, but here, all paths must inevitably converge and then be highlighted in a climactic battle. Will Cassandra be able to kill all the gods? Will Henry defeat Achilles? Will Athena and Odysseus be able to find love beyond the underworld? Such questions can only be answered by reading this decadent conclusion. There are lines that will be sure to cause some cringes in the audience, but Blake’s narrator is quite self-aware of some of the ridiculousness going on, especially with references to movies like Flatliners. I give major kudos to Blake for exploring a different version of narrative perspective that deviates from the first person storytelling offered in the Girl of Nightmares series. Fans of Blake’s YA work will be pleased to know she’s already got something cooking that will be coming out of HarperTeen later this year. Though I didn’t find this series as strong as Blake’s debut duology, there’s enough mischief and mayhem to keep readers of the paranormal romance/ YA genre quite pleased and looking forward to Three Dark Crowns (which seems to be moving Blake in the direction of witchcraft).

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/ungodly-kendare-blake/1120919171

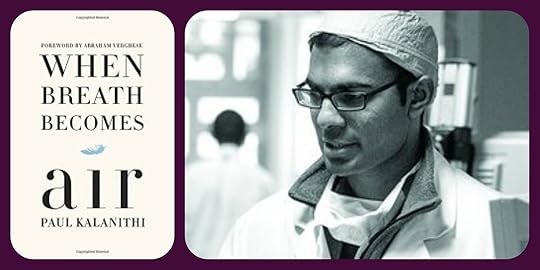

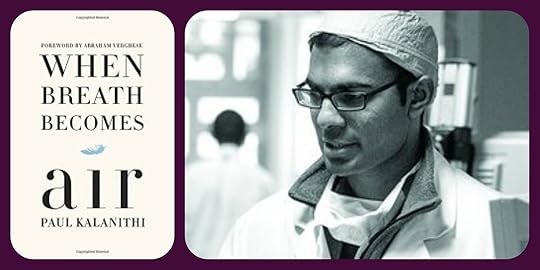

A Review of Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air (Random House, 2016).

So, I recall reading a piece in the New York Times written by Paul Kalanithi, which explored issues of death and dying. Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon, was diagnosed with metastatic stage 4B lung cancer, meaning that his cancer was terminal. For Kalanithi, it was a matter of time. I’ve been interested in Kalanithi’s memoir because it strikes very close to home. My mother was diagnosed with metastatic endometrial cancer that was also in stage 4B. My mother has already had bouts in which she was close to death (at least on three separate occasions that I can recall); she also had a complete hysterectomy, sustained challenging chemotherapy treatments that left her drained of energy and stamina. So, when I heard Kalanithi’s memoir was being published, I immediately wanted to review it. The memoir was published posthumously, and the epilogue (written by Kalanithi’s wife Lucy) reminds us that an individual who is dying can never quite complete their work in any sense. There is just not enough time, and of course, we never know the circumstances of the death unless someone else writes about it. Perhaps, what is most crucial about Kalanithi’s memoir is the issue that he brings up with respect to philosophy and the meaning of life, which seems to come down to something related to striving. That is, even while dying, even in our states of disintegration (as we age, find our bodies failing us, diseases that confound us, our memories that get more spotty), we still strive for something, find meaning in something, and thus make our lives meaningful in some particular way. For Kalanithi, this aspect of striving functions as the underlying current of cohesion that appears throughout the memoir. He details the struggles with physical therapy to regain the energy and the stamina necessary to stand in the operating room for many hours. He and his wife still plan to have a baby despite the fact of his prognosis. He continues to connect with his patients, and his colleagues, while developing a strong bond with his cancer physician. Throughout his waning days, perhaps what is most remarkable is Kalanithi’s spirit of curiosity that never dissipates despite whatever is thrown at him. The epilogue provided by Kalanithi’s wife Lucy is particularly compelling precisely because it details the final days of Kalanithi’s life; she further attempts to insert her own perspective on Kalanithi’s personality. Indeed, on some level, she seems concerned that readers may miss how funny and how humorous Kalanithi was, that somehow a part of him could be stripped from the narrative. Lucy’s mission to rectify some tonality in Kalanithi’s narrative is perhaps a larger issue related to memoirs in general: all that is left is some sort of partial, edited trace, but what a profound trace this is.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/when-breath-becomes-air-paul-kalanithi/1121955571

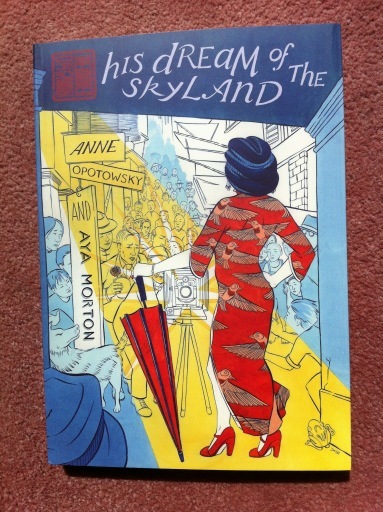

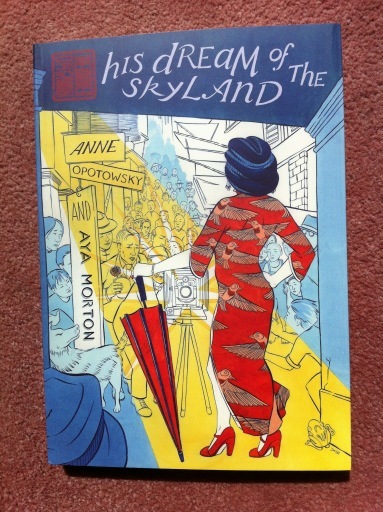

A Review of Anne Opotowsky (Author) and Aya Morton’s (Illustrator) His Dream of Skyland (Walled City Trilogy, Part 1) (Gestalt Publishing, 2011).

I haven’t been reading as many graphic narratives as much lately, so it was a real pleasure to dig into the high quality pages (and high production values) found in Anne Opotowsky (Author) and Aya Morton’s (Illustrator) His Dream of Skyland, which is part of a trilogy. The first two have been published, and I will eventually be getting to the second installment, but let’s get a plot summary going of this particular work. We’ll let the World Comic Book Review take it away from here: “In 2011, the creative team of Anne Opotowsky and Aya Morton produced a thick volume entitled “his dream of skyland”. Set in 1950s colonial Hong Kong, the story follows the meandering adventures of the hapless Chinese postal worker, Song. Hopelessly in love with a bemused prostitute and with his bumbling father in jail, Song decides to try to deliver dead letters – correspondence with no proper address, sometimes sitting around in the post office for years, but capable of delivery with some detective work and a glimmer of proactively. Delivering dead letters seems to be an eccentric but harmless preoccupation, but in doing so Song brings both joy and sadness to their various recipients, and comes to navigate the notorious and legendary Walled City of Kowloon. It is a place that recognises no authority and which in the hands of the creative team is imbued with a shadowy personality. The Walled City is like a tiger with a full belly: watchful, and idly dangerous. A helpful and beautifully rendered glossary at the end of the volume assists readers not familiar with Cantonese culture nor British colonialism. It’s an engaging and skilful endeavour, and ideal for readers with an interest in Hong Kong history.” One element that this description doesn’t mention is the close relationship that Song holds with his mother, who is a kind of diviner and occultist. Their connection provides him the stability he needs, as he tries to make a life in the shadow of his father’s absence. His job sorting letters further gives him some fulfillment, and he sees the delivery of the dead letters as a challenge and perhaps a metaphor for the desire to find more meaning in his life. Perhaps what is most crucial (at least for me) in this review is the historical tapestry that Opotowsky and Morton bring to life. Though I do know some facts about Asian American history and even some diasporic Asian contexts, I didn’t know much about the walled city, a place that has been in existence for over a century and was the recent target of urban gentrification, but during the period that Opotowsky and Morton focus on, the Walled City is a true potpourri of squatters, gamblers, scrabblers, and itinerant populations. So Song’s investment is delivering these dead letters to this area might at first seen strange, but the Walled City seems to operate with its own set of rules and creates the perfect milieu for Song to engage unexpected relationships and even friendships. But the Walled City is filled with questionable dealings, and the graphic novel invokes issues related to human trafficking and child exploitation. Amid Song’s quest to deliver dead letters, he also begins to discover the potential dangers in developing a strong attachment to this strange, but no less dynamic part of the colony. Perhaps, the most notable element that brings this graphic narrative to such vivid life is Morton’s sweeping visuals that take up space on large pages and provide the right form for this kind of story, one that involves many colorful characters who deserve their own full pictorial space. This graphic novel makes you wish that more were published on such panoramic pages, as this work is the kind you can return to again and again to find more hidden in the margins of a panel.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.gestaltcomics.com/shelf/graphic-novels/his-dream-of-the-skyland-walled-city-book-1/

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/his-dream-of-the-skyland-anne-opotowsky/1111619897

A Review of Quan Barry’s She Weeps Each Time You’re Born (Pantheon 2015).

So, to be quite honest: I had trouble getting the momentum when reading this novel. To be sure, this problem is mostly related to my own reading habits, as I’ve gotten older and more distracted, and probably too used to the prose found in YA novels (no dig on YA novelists of course). Quan Barry’s debut novel She Weeps Each Time You’re Born stands tall alongside her four other poetry collections (some which have been reviewed here) and offers a rather luminous addition to the ever growing body of Vietnamese American literatures. Barry must have been channeling Faulkner and Ondaatje (or someone of a similar writing aesthetic), as there are many narrative perspective shifts, temporal shifts, poetic sequences, and longish sentences. The novel provides a very useful diagram to open that helps to remind us of the relational connections among the characters, some of whom are not biologically related to each other. Barry’s work is historically textured and set across Vietnam’s long colonial and postcolonial history. A grandmother (Thuan), her son (Tu), the son’s wife (Little Mother), and their child (Rabbit) are the main family, but their lives are torn apart by multiple wars. During fire bombing, Little Mother is killed, while Thuan suffers significant wounds, but Little Mother is still able to give birth (somehow if I read this section right) during this period. Thuan later succumbs to her injuries. It is during the period of refugee flight that this family hooks up with another: a grandmother (Huyen) and her granddaughter (Qui) are also on the move and attempting to survive. Qui is somehow able to nurse Rabbit, which provides Rabbit with the nutrition to survive. The second half of the novel involves a slight time jump: Rabbit is a young child; she is friends with another boy around her age named Son. They spend their times training cormorants, so that they can be sold to local fisherman to aid them in their work. This sequence is one of the most beautiful in the novel and continues to the slightly surrealistic elements, especially as Rabbit seems to have a special ability to speak to these water birds. But Rabbit and Son’s friendship ends prematurely after their families endure incredible hardships at sea. The novel is reminiscent on the plotting level of Hoa Pham’s The Other Shore because Rabbit eventually develops supernatural powers concerning the ability to see and to communicate with the dead in some way. This ability is cultivated by military forces who seek to use her skills to find mass graves; in this sense, the novel’s surrealistic quality is put to use to explore the legacy of war. As the novel moves toward the conclusion, Rabbit finds herself in a romantic relationship with a Russian soldier; here, Barry unveils one of the most compelling portions of the narrative, as Barry uses this relationship to revisit an earlier trauma of the narrative. To read the event from two different perspectives demonstrates how trauma actually functions on the level of a narrative aesthetic, as Rabbit comes to understand the gravity of the events at sea only from a latent perspective. If there is one major critique to be made of the novel, it remains on the level of its episodic nature, which occasionally undercuts the power of the incredible images and lyrical prose that so strongly supports the characters and their fictional world. A highly recommended read, and given the challenge of the prose itself, a work you’d want to revisit anyway.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/she-weeps-each-time-youre-born-quan-barry/1119480067?ean=9780307911773

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews of: Kendare Blake’s Ungodly (TorTeen, 2015); Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air (Random House, 2016); Anne Opotowsky (Author) and Aya Morton’s (Illustrator) His Dream of Skyland (Walled City Trilogy, Part 1) (Gestalt Publishing, 2011); Quan Barry’s She Weeps Each Time You’re Born (Pantheon 2015).

A Review of Kendare Blake’s Ungodly (TorTeen, 2015).

The final installment of Kendare Blake’s Goddess War series appears here with Ungodly. We’ll use B&N’s website as always for our synopsis: “As ancient immortals are left reeling, a modern Athena and Hermes search the world for answers in Ungodly, the final Goddess War novel by Kendare Blake, the acclaimed author of Anna Dressed in Blood. For the Goddess of Wisdom, what Athena didn't know could fill a book. That's what Ares said. So she was wrong about some things. So the assault on Olympus left them beaten and scattered and possibly dead. So they have to fight the Fates themselves, who, it turns out, are the source of the gods' illness. And sure, Athena is stuck in the underworld, holding the body of the only hero she has ever loved. But Hermes is still topside, trying to power up Andie and Henry before he runs out of time and dies, or the Fates arrive to eat their faces. And Cassandra is up there somewhere too. On a quest for death. With the god of death. Just because things haven't gone exactly according to plan, it doesn't mean they've lost. They've only mostly lost. And there's a big difference.” As followers of this series already know: gods and heroes are reincarnated time and time again in Blake’s version of the storyworld. Cassandra takes top billing, as she is tasked to be the destroyer of gods. By the third book, Cassandra is angry because her paramour, Apollo, is killed. She is able to kill Hera at the end of the second book (and spoilers are forthcoming) but other antagonists still survive, including Ares and Aphrodite. The third book sees some alliances shift and the parties scattered. Athena must team up with Ares and Aphrodite in the Underworld, especially when Ares is able to use some quick wits to save Athena’s mortal love Odysseus. Hermes is hanging out with Henry (Hector) and Andie (Adromache), while they figure out how to defeat Achilles, who is now teamed up with the book’s major big bad The Three Fates (the Moirae). Finally, Cassandra and Calypso want to find out where Hades is, but first they have to travel to Los Angeles to find Thanatos, who will be sure to have useful information. This final installment is no doubt the strongest of all three books because Blake knows that she has to bring the storylines together. The first two suffered from the inevitable peaks and troughs that come with stretching out a plot over three books, but here, all paths must inevitably converge and then be highlighted in a climactic battle. Will Cassandra be able to kill all the gods? Will Henry defeat Achilles? Will Athena and Odysseus be able to find love beyond the underworld? Such questions can only be answered by reading this decadent conclusion. There are lines that will be sure to cause some cringes in the audience, but Blake’s narrator is quite self-aware of some of the ridiculousness going on, especially with references to movies like Flatliners. I give major kudos to Blake for exploring a different version of narrative perspective that deviates from the first person storytelling offered in the Girl of Nightmares series. Fans of Blake’s YA work will be pleased to know she’s already got something cooking that will be coming out of HarperTeen later this year. Though I didn’t find this series as strong as Blake’s debut duology, there’s enough mischief and mayhem to keep readers of the paranormal romance/ YA genre quite pleased and looking forward to Three Dark Crowns (which seems to be moving Blake in the direction of witchcraft).

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/ungodly-kendare-blake/1120919171

A Review of Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air (Random House, 2016).

So, I recall reading a piece in the New York Times written by Paul Kalanithi, which explored issues of death and dying. Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon, was diagnosed with metastatic stage 4B lung cancer, meaning that his cancer was terminal. For Kalanithi, it was a matter of time. I’ve been interested in Kalanithi’s memoir because it strikes very close to home. My mother was diagnosed with metastatic endometrial cancer that was also in stage 4B. My mother has already had bouts in which she was close to death (at least on three separate occasions that I can recall); she also had a complete hysterectomy, sustained challenging chemotherapy treatments that left her drained of energy and stamina. So, when I heard Kalanithi’s memoir was being published, I immediately wanted to review it. The memoir was published posthumously, and the epilogue (written by Kalanithi’s wife Lucy) reminds us that an individual who is dying can never quite complete their work in any sense. There is just not enough time, and of course, we never know the circumstances of the death unless someone else writes about it. Perhaps, what is most crucial about Kalanithi’s memoir is the issue that he brings up with respect to philosophy and the meaning of life, which seems to come down to something related to striving. That is, even while dying, even in our states of disintegration (as we age, find our bodies failing us, diseases that confound us, our memories that get more spotty), we still strive for something, find meaning in something, and thus make our lives meaningful in some particular way. For Kalanithi, this aspect of striving functions as the underlying current of cohesion that appears throughout the memoir. He details the struggles with physical therapy to regain the energy and the stamina necessary to stand in the operating room for many hours. He and his wife still plan to have a baby despite the fact of his prognosis. He continues to connect with his patients, and his colleagues, while developing a strong bond with his cancer physician. Throughout his waning days, perhaps what is most remarkable is Kalanithi’s spirit of curiosity that never dissipates despite whatever is thrown at him. The epilogue provided by Kalanithi’s wife Lucy is particularly compelling precisely because it details the final days of Kalanithi’s life; she further attempts to insert her own perspective on Kalanithi’s personality. Indeed, on some level, she seems concerned that readers may miss how funny and how humorous Kalanithi was, that somehow a part of him could be stripped from the narrative. Lucy’s mission to rectify some tonality in Kalanithi’s narrative is perhaps a larger issue related to memoirs in general: all that is left is some sort of partial, edited trace, but what a profound trace this is.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/when-breath-becomes-air-paul-kalanithi/1121955571

A Review of Anne Opotowsky (Author) and Aya Morton’s (Illustrator) His Dream of Skyland (Walled City Trilogy, Part 1) (Gestalt Publishing, 2011).

I haven’t been reading as many graphic narratives as much lately, so it was a real pleasure to dig into the high quality pages (and high production values) found in Anne Opotowsky (Author) and Aya Morton’s (Illustrator) His Dream of Skyland, which is part of a trilogy. The first two have been published, and I will eventually be getting to the second installment, but let’s get a plot summary going of this particular work. We’ll let the World Comic Book Review take it away from here: “In 2011, the creative team of Anne Opotowsky and Aya Morton produced a thick volume entitled “his dream of skyland”. Set in 1950s colonial Hong Kong, the story follows the meandering adventures of the hapless Chinese postal worker, Song. Hopelessly in love with a bemused prostitute and with his bumbling father in jail, Song decides to try to deliver dead letters – correspondence with no proper address, sometimes sitting around in the post office for years, but capable of delivery with some detective work and a glimmer of proactively. Delivering dead letters seems to be an eccentric but harmless preoccupation, but in doing so Song brings both joy and sadness to their various recipients, and comes to navigate the notorious and legendary Walled City of Kowloon. It is a place that recognises no authority and which in the hands of the creative team is imbued with a shadowy personality. The Walled City is like a tiger with a full belly: watchful, and idly dangerous. A helpful and beautifully rendered glossary at the end of the volume assists readers not familiar with Cantonese culture nor British colonialism. It’s an engaging and skilful endeavour, and ideal for readers with an interest in Hong Kong history.” One element that this description doesn’t mention is the close relationship that Song holds with his mother, who is a kind of diviner and occultist. Their connection provides him the stability he needs, as he tries to make a life in the shadow of his father’s absence. His job sorting letters further gives him some fulfillment, and he sees the delivery of the dead letters as a challenge and perhaps a metaphor for the desire to find more meaning in his life. Perhaps what is most crucial (at least for me) in this review is the historical tapestry that Opotowsky and Morton bring to life. Though I do know some facts about Asian American history and even some diasporic Asian contexts, I didn’t know much about the walled city, a place that has been in existence for over a century and was the recent target of urban gentrification, but during the period that Opotowsky and Morton focus on, the Walled City is a true potpourri of squatters, gamblers, scrabblers, and itinerant populations. So Song’s investment is delivering these dead letters to this area might at first seen strange, but the Walled City seems to operate with its own set of rules and creates the perfect milieu for Song to engage unexpected relationships and even friendships. But the Walled City is filled with questionable dealings, and the graphic novel invokes issues related to human trafficking and child exploitation. Amid Song’s quest to deliver dead letters, he also begins to discover the potential dangers in developing a strong attachment to this strange, but no less dynamic part of the colony. Perhaps, the most notable element that brings this graphic narrative to such vivid life is Morton’s sweeping visuals that take up space on large pages and provide the right form for this kind of story, one that involves many colorful characters who deserve their own full pictorial space. This graphic novel makes you wish that more were published on such panoramic pages, as this work is the kind you can return to again and again to find more hidden in the margins of a panel.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.gestaltcomics.com/shelf/graphic-novels/his-dream-of-the-skyland-walled-city-book-1/

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/his-dream-of-the-skyland-anne-opotowsky/1111619897

A Review of Quan Barry’s She Weeps Each Time You’re Born (Pantheon 2015).

So, to be quite honest: I had trouble getting the momentum when reading this novel. To be sure, this problem is mostly related to my own reading habits, as I’ve gotten older and more distracted, and probably too used to the prose found in YA novels (no dig on YA novelists of course). Quan Barry’s debut novel She Weeps Each Time You’re Born stands tall alongside her four other poetry collections (some which have been reviewed here) and offers a rather luminous addition to the ever growing body of Vietnamese American literatures. Barry must have been channeling Faulkner and Ondaatje (or someone of a similar writing aesthetic), as there are many narrative perspective shifts, temporal shifts, poetic sequences, and longish sentences. The novel provides a very useful diagram to open that helps to remind us of the relational connections among the characters, some of whom are not biologically related to each other. Barry’s work is historically textured and set across Vietnam’s long colonial and postcolonial history. A grandmother (Thuan), her son (Tu), the son’s wife (Little Mother), and their child (Rabbit) are the main family, but their lives are torn apart by multiple wars. During fire bombing, Little Mother is killed, while Thuan suffers significant wounds, but Little Mother is still able to give birth (somehow if I read this section right) during this period. Thuan later succumbs to her injuries. It is during the period of refugee flight that this family hooks up with another: a grandmother (Huyen) and her granddaughter (Qui) are also on the move and attempting to survive. Qui is somehow able to nurse Rabbit, which provides Rabbit with the nutrition to survive. The second half of the novel involves a slight time jump: Rabbit is a young child; she is friends with another boy around her age named Son. They spend their times training cormorants, so that they can be sold to local fisherman to aid them in their work. This sequence is one of the most beautiful in the novel and continues to the slightly surrealistic elements, especially as Rabbit seems to have a special ability to speak to these water birds. But Rabbit and Son’s friendship ends prematurely after their families endure incredible hardships at sea. The novel is reminiscent on the plotting level of Hoa Pham’s The Other Shore because Rabbit eventually develops supernatural powers concerning the ability to see and to communicate with the dead in some way. This ability is cultivated by military forces who seek to use her skills to find mass graves; in this sense, the novel’s surrealistic quality is put to use to explore the legacy of war. As the novel moves toward the conclusion, Rabbit finds herself in a romantic relationship with a Russian soldier; here, Barry unveils one of the most compelling portions of the narrative, as Barry uses this relationship to revisit an earlier trauma of the narrative. To read the event from two different perspectives demonstrates how trauma actually functions on the level of a narrative aesthetic, as Rabbit comes to understand the gravity of the events at sea only from a latent perspective. If there is one major critique to be made of the novel, it remains on the level of its episodic nature, which occasionally undercuts the power of the incredible images and lyrical prose that so strongly supports the characters and their fictional world. A highly recommended read, and given the challenge of the prose itself, a work you’d want to revisit anyway.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/she-weeps-each-time-youre-born-quan-barry/1119480067?ean=9780307911773

Published on March 23, 2016 19:01

March 13, 2016

Ken Liu's The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories

I apparently have a soft spot for works of literature with the word menagerie in the title; the play The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams has been one of my favorites since I first read it in high school. Add to that play my love for Ken Liu's short story, "The Paper Menagerie," which you can read in full for free at i09. I happily read through Liu's collection of short stories just published, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories (Saga Press, 2016), and enjoyed the range of fantasy and science fiction stories that demonstrate Liu's unique yoking of those genres with historically and racially astute narratives.

Read the story but prepare to weep! It is an astoundingly moving short story that exemplifies Liu's imagination and ability to yoke together the fabulist mentality of fantasy/science fiction genres with a deeply emotional awareness of the lived experiences of racialization in the United States. There's something extraordinary about the fragility embodied in the paper tiger, the zhezhi created by the protagonist's mother as expressions of her love and her past. As my friend stephenhongsohn

pointed out regarding this story, racial melancholia is the worst! The story truly captures the loss attendant upon immigrant families that is passed intergenerationally through both the disconnection from a home country and the experiences of racist antagonism in the new homeland. I love the magic of the paper tiger and other creatures, a set of toys that comes alive with the mother's breath. Yet, these are toys not understood nor appreciated by the white American boys in the protagonist's neighborhood, and as such, they became markers of the shame that he feels at being different and not-quite-American--things to be rejected and hidden along with Chinese language in favor of things like factory-made Star Wars toys and English language.

stephenhongsohn

pointed out regarding this story, racial melancholia is the worst! The story truly captures the loss attendant upon immigrant families that is passed intergenerationally through both the disconnection from a home country and the experiences of racist antagonism in the new homeland. I love the magic of the paper tiger and other creatures, a set of toys that comes alive with the mother's breath. Yet, these are toys not understood nor appreciated by the white American boys in the protagonist's neighborhood, and as such, they became markers of the shame that he feels at being different and not-quite-American--things to be rejected and hidden along with Chinese language in favor of things like factory-made Star Wars toys and English language.

The other stories in this collection are similarly thought-provoking and often heartbreaking as well. Some of the stories are thought experiments, taking up a scientific concept and spinning it into fictions of worlds beyond our current experiences. The opening story, "The Bookmaking Habits of Select Species," for instance, considers what it means to record experiences in written form and takes as a form some brief descriptions of how various species "write" and archive experiences. As a result, the story questions what it means to have intelligence and to separate thought from physicality.

The stories I liked the most take on a fantastical or science fictional mode while weaving in Asian/American experiences. I also especially appreciated Liu's attention to the historical and linguistic specificity of Taiwanese experiences, with a complicated grappling with Japanese colonialism, Chinese politics, and a yearning to understand the silences in familial stories. In this respect, "The Literomancer" is especially moving. It centers on a white American girl who moves with her parents to Taiwan during the Cold War. The father works for the US government in some capacity as someone intent on ferreting out Communist spies with the Taiwanese Nationalist government. The girl befriends a boy her age and his grandfather. The grandfather practices literomancy, the magic of prophesying through words, particularly in reading the chacters of Chinese words for deeper meaning. The story is tragic, much like "The Paper Menagerie" is, with childhood innocence destroyed upon the reefs of grown up political hostilities, and the girl becomes part of a betrayal that she cannot possibly understand.

Amont the other stories that I really loved, "A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel" and "The Man Who Ended History: A Documentary" stood out for their grappling with our sense of historical truth, understanding, and forgiveness. "A Brief History" is an alternate history story in which, instead of entering a second world war, Japan and the United States embark on a trans-Pacific, undersea tunnel to connect Asia and North America. The resulting decade of work stimulates the Depression era economy and diverts inter-country aggression towards this shifting configuration of global trade. Of course, this alternate history echoes the work of Chinese railroad workers who helped build the transcontinental railroad on North American soil in the 1800s.

"The Man Who Ended History," similarly, engages with the difficulties of mid-20th century world politics but from a science fictional perspective in which a husband-wife team of historian-experimental physicist discover a way for individuals to experience historical moments but in the process always destroy those moments from further experience. The Chinese American husband, an historian, becomes obsessed with redressing the atrocities of Unit 731, a secret laboratory/horror chamber during World War II in which the Japanese Imperial Army experimented on Chinese and other prisoners and civilians to test the limits of physical pain and endurance as well as to explore possible biological weaponry. The Japanese American wife, the experimental physicist, provides the means for him to send relatives of victims of Unit 731 to the past to experience what really happened. The story takes the form of a documentary film and offers varying perspectives on what it means to remember a historical event, to apologize for atrocities of the past, to be accountable as governments that did or did not exist in the same way at different moments in time, and ultimately to remember while moving forward in time.

These stories are all remarkable, beautifully written and provocative in their subject matter.

Read the story but prepare to weep! It is an astoundingly moving short story that exemplifies Liu's imagination and ability to yoke together the fabulist mentality of fantasy/science fiction genres with a deeply emotional awareness of the lived experiences of racialization in the United States. There's something extraordinary about the fragility embodied in the paper tiger, the zhezhi created by the protagonist's mother as expressions of her love and her past. As my friend

stephenhongsohn

pointed out regarding this story, racial melancholia is the worst! The story truly captures the loss attendant upon immigrant families that is passed intergenerationally through both the disconnection from a home country and the experiences of racist antagonism in the new homeland. I love the magic of the paper tiger and other creatures, a set of toys that comes alive with the mother's breath. Yet, these are toys not understood nor appreciated by the white American boys in the protagonist's neighborhood, and as such, they became markers of the shame that he feels at being different and not-quite-American--things to be rejected and hidden along with Chinese language in favor of things like factory-made Star Wars toys and English language.

stephenhongsohn

pointed out regarding this story, racial melancholia is the worst! The story truly captures the loss attendant upon immigrant families that is passed intergenerationally through both the disconnection from a home country and the experiences of racist antagonism in the new homeland. I love the magic of the paper tiger and other creatures, a set of toys that comes alive with the mother's breath. Yet, these are toys not understood nor appreciated by the white American boys in the protagonist's neighborhood, and as such, they became markers of the shame that he feels at being different and not-quite-American--things to be rejected and hidden along with Chinese language in favor of things like factory-made Star Wars toys and English language.The other stories in this collection are similarly thought-provoking and often heartbreaking as well. Some of the stories are thought experiments, taking up a scientific concept and spinning it into fictions of worlds beyond our current experiences. The opening story, "The Bookmaking Habits of Select Species," for instance, considers what it means to record experiences in written form and takes as a form some brief descriptions of how various species "write" and archive experiences. As a result, the story questions what it means to have intelligence and to separate thought from physicality.

The stories I liked the most take on a fantastical or science fictional mode while weaving in Asian/American experiences. I also especially appreciated Liu's attention to the historical and linguistic specificity of Taiwanese experiences, with a complicated grappling with Japanese colonialism, Chinese politics, and a yearning to understand the silences in familial stories. In this respect, "The Literomancer" is especially moving. It centers on a white American girl who moves with her parents to Taiwan during the Cold War. The father works for the US government in some capacity as someone intent on ferreting out Communist spies with the Taiwanese Nationalist government. The girl befriends a boy her age and his grandfather. The grandfather practices literomancy, the magic of prophesying through words, particularly in reading the chacters of Chinese words for deeper meaning. The story is tragic, much like "The Paper Menagerie" is, with childhood innocence destroyed upon the reefs of grown up political hostilities, and the girl becomes part of a betrayal that she cannot possibly understand.

Amont the other stories that I really loved, "A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel" and "The Man Who Ended History: A Documentary" stood out for their grappling with our sense of historical truth, understanding, and forgiveness. "A Brief History" is an alternate history story in which, instead of entering a second world war, Japan and the United States embark on a trans-Pacific, undersea tunnel to connect Asia and North America. The resulting decade of work stimulates the Depression era economy and diverts inter-country aggression towards this shifting configuration of global trade. Of course, this alternate history echoes the work of Chinese railroad workers who helped build the transcontinental railroad on North American soil in the 1800s.

"The Man Who Ended History," similarly, engages with the difficulties of mid-20th century world politics but from a science fictional perspective in which a husband-wife team of historian-experimental physicist discover a way for individuals to experience historical moments but in the process always destroy those moments from further experience. The Chinese American husband, an historian, becomes obsessed with redressing the atrocities of Unit 731, a secret laboratory/horror chamber during World War II in which the Japanese Imperial Army experimented on Chinese and other prisoners and civilians to test the limits of physical pain and endurance as well as to explore possible biological weaponry. The Japanese American wife, the experimental physicist, provides the means for him to send relatives of victims of Unit 731 to the past to experience what really happened. The story takes the form of a documentary film and offers varying perspectives on what it means to remember a historical event, to apologize for atrocities of the past, to be accountable as governments that did or did not exist in the same way at different moments in time, and ultimately to remember while moving forward in time.

These stories are all remarkable, beautifully written and provocative in their subject matter.

Published on March 13, 2016 12:23

March 7, 2016

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for March 7, 2016

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for March 7, 2016

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews for Sunil Yapa’s Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist (Little, Brown and Company, 2016); Christie Hsiao’s Journey to Rainbow Island (BenBella Books, 2013); Emiko Jean’s We’ll Never Be Apart (Houghton Mifflin Young Adult, 2016); Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens (William Morrow, 2015).

A Review of Sunil Yapa’s Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist (Little, Brown and Company, 2016).

Sunil Yapa’s debut novel Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist is an intriguing study in the fictionalization of a major event: the 1999 WTO protests. We’ll let B&N provide the useful synopsis here: “On a rainy, cold day in November, young Victor—a nomadic, scrappy teenager who's run away from home—sets out to join the throng of WTO demonstrators determined to shut down the city. With the proceeds, he plans to buy a plane ticket and leave Seattle forever, but it quickly becomes clear that the history-making 50,000 anti-globalization protestors—from anarchists to environmentalists to teamsters—are testing the patience of the police, and what started out as a peaceful protest is threatening to erupt into violence. Over the course of one life-altering afternoon, the fates of seven people will change forever: foremost among them police Chief Bishop, the estranged father Victor hasn't seen in three years, two protesters struggling to stay true to their non-violent principles as the day descends into chaos, two police officers in the street, and the coolly elegant financial minister from Sri Lanka whose life, as well as his country's fate, hinges on getting through the angry crowd, out of jail, and to his meeting with the President of the United States. When Chief Bishop reluctantly unleashes tear gas on the unsuspecting crowd, it seems his hopes for reconciliation with his son, as well as the future of his city, are in serious peril.” Though Victor does ostensibly seem to be the protagonist of this work, Yapa splits the perspective amongst these seven characters, who do include the aforementioned Chief Bishop, two other police officers (Timothy Park and Julia), two protesters (John Henry and King), Charles Wickramsinghe (the “elegant financial minister from Sri Lanka”). The fates of these seven characters eventually collide in a manner not dissimilar to something we might see in a Robert Altman movie. Victor, for instance, is pulled into the protests, even though he seems to be mostly ambivalent about them. King and John Henry, we discover, are lovers, though King is harboring a dark secret regarding her past, which limits her effectiveness in the protests. Chief Bishop (along with his fellow police officers) attempts to maintain order over his city, something that becomes increasingly difficult as the protests escalate in their scope and rhetoric. The actual diplomatic work being conducted by Charles Wickramsinghe is structured through intermissions, as he attempts to rally the support to gain Sri Lanka’s entrance into the World Trade Organization. Yapa is particularly deft in his use of analepses, effectively using flashbacks and shifts back in time to unveil the psychological shape of the main characters. Victor, in particular, comes off as a well-rounded figure seeking to find fulfillment, having struggled with a complicated upbringing involving migration and adoption. Yapa’s work is certainly provocative in its exploration of activism, racial discord, protest cultures, and police brutality, more so because Yapa is intent in twining the political with the personal. The narrative can sometimes sag because of this dynamic and the conclusion might strike some as too philosophically broad, but Yapa’s work is certainly fresh in its unique narrative conceit, as it employs a shifting third and second person narration to reveal the complicated interior lives of these seven characters. Further still, this work intrigues me, especially in its kaleidoscopic storytelling depictions, as the seven narrative perspectives all come from characters of varied ethnoracial backgrounds. Had this novel been published earlier, I might have written about it in my first book, which by the way, just passed its two year birthday (shout out to myself). Finally, readers of Asian American literature will no doubt find productive comparisons between this novel and Yamashita’s Tropic of Orange, not only on the level of its seven primary characters, but its association around a climactic event (an apocalyptic freeway event in Los Angeles downtown vs. the WTO riots).

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/your-heart-is-a-muscle-the-size-of-a-fist-sunil-yapa/1121865205

A Review of Emiko Jean’s We’ll Never Be Apart (Houghton Mifflin Young Adult, 2016).

Emiko Jean’s We’ll Never Apart starts with an intriguing premise: an emotionally disturbed young teenager named Cellie starts a fire. In the process, it seems as though she will be ending possibly her own life, her sister’s life (Alice Monroe), and her sister’s boyfriend’s life (Jason). After this prologue, the narrative perspective shifts to Alice (and remains there for most of the novel), and we’re left in the wake of that fire. Alice doesn’t remember everything that happened that night. All she knows is that she tried to escape from a mental health facility with her foster brother Jason, but their eventual path to freedom is thwarted by the mentally unhinged Cellie, who arrives at precisely the worst time. From this point forward, Alice is stuck back in the mental facility (in/appropriately called Savage Isle, located it seems somewhere in California), navigating life in the C ward, where she’s able to filter in with other patients like herself. She makes friends with her new roomie Amelia, while developing a potential romantic interest with another troubled teen named Chase Ward (if you’re seeing the play on “chase” and “ward” in relation to finding out the truth in the mental facility, you’ll start to see that this novel tries a little bit too hard at times). At the same time, Alice eventually discovers that Jason was killed in the fire, which leads her to believe that Cellie is still alive and probably being held in the D ward, the isolation area in which the most damaged and deranged patients are kept in padded rooms. Alice hatches a plan, using Chase’s assistance, to find a way to get into D ward, so she might have the chance to kill Cellie, before Cellie would ostensibly kill her. Due to heightened security measures, though, Alice cannot get to D ward right away, so the novel gives us other things to worry about. For instance, Alice starts to write in a journal, as suggested to her by her therapist. The journal is a critical narrative device that gives us the painful backstory of Alice and her sister Cellie: how they were sent into foster care only after they were found living alone with the deceased corpse of their grandfather. It is in the foster care system that Alice and Cellie meet Jason; Alice and Jason will eventually develop a romantic interest in each other, which will cause Cellie to develop a sense of jealousy that will ultimately, or so Alice thinks, turn homicidal. First time author Emiko Jean takes a big gamble on employing an unreliable narrative perspective precisely because we’re already made to be suspicious. Readers like myself already figured out the central conceit undergirding the narrative soon after it began, and I simply hoped that I would be wrong. Because of this possibility, some readers will definitely be disappointed on the level of plot exposition at the conclusion, but the larger social context that Jean brings up is of course important: the necessity of proper care (both mental and physical) for youth in the foster care system. It is evident that the novel’s main intervention in terms of its critique of social inequalities remains the ways in which we let youth potentially rot in a system in which their lives are ultimately dependent upon the capricious care of adults.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/well-never-be-apart-emiko-jean/1120874784

A Review of Christie Hsiao’s Journey to Rainbow Island (BenBella Books, 2013)

So, I often alternate in between “adult” more serious reading and middle grade/ YA material, and I recently settled on Christie Hsiao’s Journey to Rainbow Island (BenBella Books). This title was one I chanced upon while browsing online bookstores and their offerings. In any case, Hsiao’s debut employs the more traditional fantasy conceits in order to build a storyworld involving a young girl on a quest to save her home, the titular Rainbow Island. After a dark sorcerer revives a long dead obisidigon through evil magics, Yu-Ning must take up her own destiny as a Darq Render to defeat the growing danger. As per usual, we’ll let the folks over at B&N take over with the rest of the plot: “Yu-ning thinks her perfect life on Rainbow Island will never end—until a nasty dragon called the Obsidigon returns from beyond the grave. Now her beloved island is in flames, her best friend has been kidnapped, and the island’s Sacred Crystals have been stolen. To make matters worse, she must venture into the dark corners of the world to uncover secrets best ignored, find a weapon thought long destroyed, and recapture seven sacred stones—without being burned to a crisp by a very angry dragon. With the help of her master teacher, Metatron, Yu-ning embarks on a dangerous journey to overcome not only the darkness attacking her home, but also the scars of sadness that mark her own heart. And while most people just see a normal kid, Metatron—and a few other unlikely allies—pledge their lives to the dark-eyed little girl with a magic bow and a crooked grin.” Yu-ning’s journey involves having to find a bow (called the Lightcaster) and its magical arrows in order to defeat the sorcerer and the obsidigon. She must travel to various islands and locations, challenge smaller villains and antagonists—such as a sweatshop boss and a taskmaster teacher—in order to navigate her perilous tasks. Throughout, Hsiao’s point is very clear: Yu-ning must use the power of love and light to defeat all enemies. For some, this message will obviously come off as trite and perhaps too simplistic, especially since the novel does dovetail with larger problematics of global capitalism and human trafficking even in allegorized forms. Further still, Yu-ning’s can-do attitude never flags, which marks her as a perhaps too-static heroine, one that never flags in her belief that good will always defeat evil. Certainly, the novel’s target audience will be pleased: the plot continually conjures up another challenge to Yu-ning, and Hsiao is especially willing to explore fantastic conceits that will delight young readers, such as talking animals, special magic items, and technological marvels. There are also some very striking visuals (more realist in their quality) included, which contrast significantly with the fantasy style of the narrative. Interestingly enough, Hsiao also seems to be intent on leaving the ethnicities of her characters unmarked, even as there are some obvious nods to an East Asian centric heritage of some of the places and figures. These layerings do make the world more textured, but some readers will no doubt overlook such intentionalities. Hsiao leaves the novel open for a sequel, but as of this time, there is no word on whether or not Yu-ning will have to face sorcerers, dark creatures, and obsidigons any time soon. For the time being, then, she and her allies can rest easy in the idyllic and love-filled place called Rainbow Island.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/journey-to-rainbow-island-christie-hsiao/1114591405

A Review of Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens (William Morrow, 2015)

Here, I am reviewing Tony Tulathimutte’s debut novel Private Citizens. So, this book is going to provoke a deep response in the reader in one way or another. The polarizing nature of this novel is because it is tonally mutable: it’s definitely satirical at times, but at others, you get a much more of a romantic, courtship narrative in which you see Tulathimutte working with characters who are trying to connect with each other in the turbulent period after undergraduate school. We’ll let the plot summary over at B&N do some work for us: “From a brilliant new literary talent comes a sweeping comic portrait of privilege, ambition, and friendship in millennial San Francisco. With the social acuity of Adelle Waldman and the murderous wit of Martin Amis, Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens is a brainy, irreverent debut—This Side of Paradise for a new era. Capturing the anxious, self-aware mood of young college grads in the aughts, Private Citizens embraces the contradictions of our new century: call it a loving satire. A gleefully rude comedy of manners. Middlemarch for Millennials. The novel's four whip-smart narrators—idealistic Cory, Internet-lurking Will, awkward Henrik, and vicious Linda—are torn between fixing the world and cannibalizing it. In boisterous prose that ricochets between humor and pain, the four estranged friends stagger through the Bay Area’s maze of tech startups, protestors, gentrifiers, karaoke bars, house parties, and cultish self-help seminars, washing up in each other’s lives once again. A wise and searching depiction of a generation grappling with privilege and finding grace in failure, Private Citizens is as expansively intelligent as it is full of heart.” I’m tempted to review the language in this review, but I’ll avoid that task and just explain that the novel is grounded in those four characters. Cory is the progressive liberal of the bunch who has joined a start up with a more humanistic view of the future. Will is the Asian American of the bunch, perhaps the character modeled somewhat autobiographically after the writer. He is Thai, he’s short, he’s a bit angry, and he’s in a relationship with the very beautiful, wheelchair bound Vanya. Henrik is the scholar of the bunch, or so he was, until he drops out of graduate school, then struggles to find his footing Then, there’s Linda: she is a hot mess. She couch surfs, manipulates men to do things for her, and generally scrabbles her way through life. The narrative sees all four of them return to San Francisco a number of years after they graduated from Stanford. They’re not as close as they once were, and this novel explores why their paths have diverged, and of course, why those paths will eventually again converge. But the narrative is perhaps secondary to Tulathimutte’s incredibly engaging third person storyteller, who often undercuts the characters to mock them. There is both a benefit and a drawback to this kind of narrator. On the one hand, the narrator does make the work considerably humorous, but, on the other, you wonder sometimes about whether you can find an emotional center at all. It’s easy to hate every single one of the main characters given the way that the narrator is able to critique them with such stylistic verve, but the later stages of the book give way to other discursive modes. For instance, the introduction of first person journaling begins to chip away at this narrator, suggesting that there isn’t some postmodern hipsterish millennial tech bubble core to each of these characters, and that they wish to move beyond desultory relationships, for something better, even if it’s never quite possessed and always a little bit and only a dream.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/private-citizens-tony-tulathimutte/1121953916

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews for Sunil Yapa’s Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist (Little, Brown and Company, 2016); Christie Hsiao’s Journey to Rainbow Island (BenBella Books, 2013); Emiko Jean’s We’ll Never Be Apart (Houghton Mifflin Young Adult, 2016); Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens (William Morrow, 2015).

A Review of Sunil Yapa’s Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist (Little, Brown and Company, 2016).

Sunil Yapa’s debut novel Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist is an intriguing study in the fictionalization of a major event: the 1999 WTO protests. We’ll let B&N provide the useful synopsis here: “On a rainy, cold day in November, young Victor—a nomadic, scrappy teenager who's run away from home—sets out to join the throng of WTO demonstrators determined to shut down the city. With the proceeds, he plans to buy a plane ticket and leave Seattle forever, but it quickly becomes clear that the history-making 50,000 anti-globalization protestors—from anarchists to environmentalists to teamsters—are testing the patience of the police, and what started out as a peaceful protest is threatening to erupt into violence. Over the course of one life-altering afternoon, the fates of seven people will change forever: foremost among them police Chief Bishop, the estranged father Victor hasn't seen in three years, two protesters struggling to stay true to their non-violent principles as the day descends into chaos, two police officers in the street, and the coolly elegant financial minister from Sri Lanka whose life, as well as his country's fate, hinges on getting through the angry crowd, out of jail, and to his meeting with the President of the United States. When Chief Bishop reluctantly unleashes tear gas on the unsuspecting crowd, it seems his hopes for reconciliation with his son, as well as the future of his city, are in serious peril.” Though Victor does ostensibly seem to be the protagonist of this work, Yapa splits the perspective amongst these seven characters, who do include the aforementioned Chief Bishop, two other police officers (Timothy Park and Julia), two protesters (John Henry and King), Charles Wickramsinghe (the “elegant financial minister from Sri Lanka”). The fates of these seven characters eventually collide in a manner not dissimilar to something we might see in a Robert Altman movie. Victor, for instance, is pulled into the protests, even though he seems to be mostly ambivalent about them. King and John Henry, we discover, are lovers, though King is harboring a dark secret regarding her past, which limits her effectiveness in the protests. Chief Bishop (along with his fellow police officers) attempts to maintain order over his city, something that becomes increasingly difficult as the protests escalate in their scope and rhetoric. The actual diplomatic work being conducted by Charles Wickramsinghe is structured through intermissions, as he attempts to rally the support to gain Sri Lanka’s entrance into the World Trade Organization. Yapa is particularly deft in his use of analepses, effectively using flashbacks and shifts back in time to unveil the psychological shape of the main characters. Victor, in particular, comes off as a well-rounded figure seeking to find fulfillment, having struggled with a complicated upbringing involving migration and adoption. Yapa’s work is certainly provocative in its exploration of activism, racial discord, protest cultures, and police brutality, more so because Yapa is intent in twining the political with the personal. The narrative can sometimes sag because of this dynamic and the conclusion might strike some as too philosophically broad, but Yapa’s work is certainly fresh in its unique narrative conceit, as it employs a shifting third and second person narration to reveal the complicated interior lives of these seven characters. Further still, this work intrigues me, especially in its kaleidoscopic storytelling depictions, as the seven narrative perspectives all come from characters of varied ethnoracial backgrounds. Had this novel been published earlier, I might have written about it in my first book, which by the way, just passed its two year birthday (shout out to myself). Finally, readers of Asian American literature will no doubt find productive comparisons between this novel and Yamashita’s Tropic of Orange, not only on the level of its seven primary characters, but its association around a climactic event (an apocalyptic freeway event in Los Angeles downtown vs. the WTO riots).

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/your-heart-is-a-muscle-the-size-of-a-fist-sunil-yapa/1121865205

A Review of Emiko Jean’s We’ll Never Be Apart (Houghton Mifflin Young Adult, 2016).

Emiko Jean’s We’ll Never Apart starts with an intriguing premise: an emotionally disturbed young teenager named Cellie starts a fire. In the process, it seems as though she will be ending possibly her own life, her sister’s life (Alice Monroe), and her sister’s boyfriend’s life (Jason). After this prologue, the narrative perspective shifts to Alice (and remains there for most of the novel), and we’re left in the wake of that fire. Alice doesn’t remember everything that happened that night. All she knows is that she tried to escape from a mental health facility with her foster brother Jason, but their eventual path to freedom is thwarted by the mentally unhinged Cellie, who arrives at precisely the worst time. From this point forward, Alice is stuck back in the mental facility (in/appropriately called Savage Isle, located it seems somewhere in California), navigating life in the C ward, where she’s able to filter in with other patients like herself. She makes friends with her new roomie Amelia, while developing a potential romantic interest with another troubled teen named Chase Ward (if you’re seeing the play on “chase” and “ward” in relation to finding out the truth in the mental facility, you’ll start to see that this novel tries a little bit too hard at times). At the same time, Alice eventually discovers that Jason was killed in the fire, which leads her to believe that Cellie is still alive and probably being held in the D ward, the isolation area in which the most damaged and deranged patients are kept in padded rooms. Alice hatches a plan, using Chase’s assistance, to find a way to get into D ward, so she might have the chance to kill Cellie, before Cellie would ostensibly kill her. Due to heightened security measures, though, Alice cannot get to D ward right away, so the novel gives us other things to worry about. For instance, Alice starts to write in a journal, as suggested to her by her therapist. The journal is a critical narrative device that gives us the painful backstory of Alice and her sister Cellie: how they were sent into foster care only after they were found living alone with the deceased corpse of their grandfather. It is in the foster care system that Alice and Cellie meet Jason; Alice and Jason will eventually develop a romantic interest in each other, which will cause Cellie to develop a sense of jealousy that will ultimately, or so Alice thinks, turn homicidal. First time author Emiko Jean takes a big gamble on employing an unreliable narrative perspective precisely because we’re already made to be suspicious. Readers like myself already figured out the central conceit undergirding the narrative soon after it began, and I simply hoped that I would be wrong. Because of this possibility, some readers will definitely be disappointed on the level of plot exposition at the conclusion, but the larger social context that Jean brings up is of course important: the necessity of proper care (both mental and physical) for youth in the foster care system. It is evident that the novel’s main intervention in terms of its critique of social inequalities remains the ways in which we let youth potentially rot in a system in which their lives are ultimately dependent upon the capricious care of adults.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/well-never-be-apart-emiko-jean/1120874784

A Review of Christie Hsiao’s Journey to Rainbow Island (BenBella Books, 2013)

So, I often alternate in between “adult” more serious reading and middle grade/ YA material, and I recently settled on Christie Hsiao’s Journey to Rainbow Island (BenBella Books). This title was one I chanced upon while browsing online bookstores and their offerings. In any case, Hsiao’s debut employs the more traditional fantasy conceits in order to build a storyworld involving a young girl on a quest to save her home, the titular Rainbow Island. After a dark sorcerer revives a long dead obisidigon through evil magics, Yu-Ning must take up her own destiny as a Darq Render to defeat the growing danger. As per usual, we’ll let the folks over at B&N take over with the rest of the plot: “Yu-ning thinks her perfect life on Rainbow Island will never end—until a nasty dragon called the Obsidigon returns from beyond the grave. Now her beloved island is in flames, her best friend has been kidnapped, and the island’s Sacred Crystals have been stolen. To make matters worse, she must venture into the dark corners of the world to uncover secrets best ignored, find a weapon thought long destroyed, and recapture seven sacred stones—without being burned to a crisp by a very angry dragon. With the help of her master teacher, Metatron, Yu-ning embarks on a dangerous journey to overcome not only the darkness attacking her home, but also the scars of sadness that mark her own heart. And while most people just see a normal kid, Metatron—and a few other unlikely allies—pledge their lives to the dark-eyed little girl with a magic bow and a crooked grin.” Yu-ning’s journey involves having to find a bow (called the Lightcaster) and its magical arrows in order to defeat the sorcerer and the obsidigon. She must travel to various islands and locations, challenge smaller villains and antagonists—such as a sweatshop boss and a taskmaster teacher—in order to navigate her perilous tasks. Throughout, Hsiao’s point is very clear: Yu-ning must use the power of love and light to defeat all enemies. For some, this message will obviously come off as trite and perhaps too simplistic, especially since the novel does dovetail with larger problematics of global capitalism and human trafficking even in allegorized forms. Further still, Yu-ning’s can-do attitude never flags, which marks her as a perhaps too-static heroine, one that never flags in her belief that good will always defeat evil. Certainly, the novel’s target audience will be pleased: the plot continually conjures up another challenge to Yu-ning, and Hsiao is especially willing to explore fantastic conceits that will delight young readers, such as talking animals, special magic items, and technological marvels. There are also some very striking visuals (more realist in their quality) included, which contrast significantly with the fantasy style of the narrative. Interestingly enough, Hsiao also seems to be intent on leaving the ethnicities of her characters unmarked, even as there are some obvious nods to an East Asian centric heritage of some of the places and figures. These layerings do make the world more textured, but some readers will no doubt overlook such intentionalities. Hsiao leaves the novel open for a sequel, but as of this time, there is no word on whether or not Yu-ning will have to face sorcerers, dark creatures, and obsidigons any time soon. For the time being, then, she and her allies can rest easy in the idyllic and love-filled place called Rainbow Island.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/journey-to-rainbow-island-christie-hsiao/1114591405

A Review of Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens (William Morrow, 2015)

Here, I am reviewing Tony Tulathimutte’s debut novel Private Citizens. So, this book is going to provoke a deep response in the reader in one way or another. The polarizing nature of this novel is because it is tonally mutable: it’s definitely satirical at times, but at others, you get a much more of a romantic, courtship narrative in which you see Tulathimutte working with characters who are trying to connect with each other in the turbulent period after undergraduate school. We’ll let the plot summary over at B&N do some work for us: “From a brilliant new literary talent comes a sweeping comic portrait of privilege, ambition, and friendship in millennial San Francisco. With the social acuity of Adelle Waldman and the murderous wit of Martin Amis, Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens is a brainy, irreverent debut—This Side of Paradise for a new era. Capturing the anxious, self-aware mood of young college grads in the aughts, Private Citizens embraces the contradictions of our new century: call it a loving satire. A gleefully rude comedy of manners. Middlemarch for Millennials. The novel's four whip-smart narrators—idealistic Cory, Internet-lurking Will, awkward Henrik, and vicious Linda—are torn between fixing the world and cannibalizing it. In boisterous prose that ricochets between humor and pain, the four estranged friends stagger through the Bay Area’s maze of tech startups, protestors, gentrifiers, karaoke bars, house parties, and cultish self-help seminars, washing up in each other’s lives once again. A wise and searching depiction of a generation grappling with privilege and finding grace in failure, Private Citizens is as expansively intelligent as it is full of heart.” I’m tempted to review the language in this review, but I’ll avoid that task and just explain that the novel is grounded in those four characters. Cory is the progressive liberal of the bunch who has joined a start up with a more humanistic view of the future. Will is the Asian American of the bunch, perhaps the character modeled somewhat autobiographically after the writer. He is Thai, he’s short, he’s a bit angry, and he’s in a relationship with the very beautiful, wheelchair bound Vanya. Henrik is the scholar of the bunch, or so he was, until he drops out of graduate school, then struggles to find his footing Then, there’s Linda: she is a hot mess. She couch surfs, manipulates men to do things for her, and generally scrabbles her way through life. The narrative sees all four of them return to San Francisco a number of years after they graduated from Stanford. They’re not as close as they once were, and this novel explores why their paths have diverged, and of course, why those paths will eventually again converge. But the narrative is perhaps secondary to Tulathimutte’s incredibly engaging third person storyteller, who often undercuts the characters to mock them. There is both a benefit and a drawback to this kind of narrator. On the one hand, the narrator does make the work considerably humorous, but, on the other, you wonder sometimes about whether you can find an emotional center at all. It’s easy to hate every single one of the main characters given the way that the narrator is able to critique them with such stylistic verve, but the later stages of the book give way to other discursive modes. For instance, the introduction of first person journaling begins to chip away at this narrator, suggesting that there isn’t some postmodern hipsterish millennial tech bubble core to each of these characters, and that they wish to move beyond desultory relationships, for something better, even if it’s never quite possessed and always a little bit and only a dream.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/private-citizens-tony-tulathimutte/1121953916

Published on March 07, 2016 14:44

March 5, 2016

Jhumpa Lahiri's In Other Words (and reflections on international writing)

Jhumpa Lahiri's In Other Words (Knopf, 2016; translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein) is a fascinating, brief series of essays about the author's embrace of Italian as a language for reading and writing after her decades of master storytelling in English. The translation in English appears in the first half of the book with the original Italian in the second half.

A review in The New York Times tends to point out the clunkiness of the prose and Lahiri's own acknowledgement that this writing is nothing like her English-language prose, but for me, what is utterly beautiful about this book is Lahiri's self-conscious exploration of language as a medium for thinking and living, especially when she deliberately displaces herself into a foreign language that is neither her parents' native language (Bengali) spoken at home nor the language of a country in which she grew up (English). She chooses Italian in part because of her background studying Italian language and literature but also because of her experiences visiting Italy a few times in early adulthood. These visits crystallized for her the power of language and identity and shook loose the experiences many Asian Americans have in the United States when their appearance leads others to expect certain kinds of words and accents to come from their mouths.

I love Lahiri's determination to read and write only in Italian while she lives for a few years in Italy with her family. This decision alienates her from the language that is most comfortable for her but also demands that she stretch her thinking and her ability to articulate her ideas in words.

There are two pieces in the collection that are more like (fictional) short stories than essays, and they operate in a sort of dream-like tone. I don't know if it is the influence of Italian literature or something else that leads her to write stories that are functionally quite distinct from her realist, spare prose in English. She herself comments that there is also something interesting about the autobiographical impulse when she writes in English versus in Italian. As an Asian American writer, she is read by most people as imbuing her fiction with autobiographical facts or perspectives, even as she insists that her fiction is created characters and worlds; but in Italian, she turns staunchly towards the autobiographical I, stripping away even the veneer of fiction in most of the essays to embrace the memoir form.

Lahiri's book is about an American writing in Italian and about an Asian American embracing a foreign language that is not what is expected of her as a mother tongue. There is a lot about translation between languages in the book, especially about the impossibility of full translations that capture nuances of a language's literary history. What is fascinating to me is that at the end of the day, we will probably still read this book as one by an American writer, even though it had to be translated from the original Italian. What does that mean for our conception of national language and of translation?