Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 47

May 23, 2016

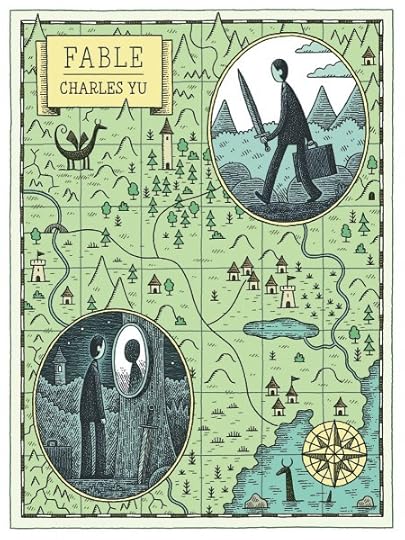

Two short stories by Charles Yu and Alyssa Wong

The two stories I read were Charles Yu's "Fable" in the New Yorker and Alyssa Wong's "Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers" in Nightmare. Both stories are in the realm of speculative/fantasy fiction, and both function on an allegorical register for how we conceive of people's every day life. Yu's story centers on a man trying to make sense of his life's trajectory (choosing a career, finding a wife, having a child to build a family, etc.), and Wong's story considers how a daughter learned to live and relate to others via what her mothers taught and showed her through her actions.

Illustration by Tom Gauld.

There are also a couple of great extras for Yu's story at the New Yorker: a brief interview on therapy and storytelling and an audio recording of Yu's reading of the story. "Fable" is like some of Yu's other fiction in its metacommentary on its own genre and on the way the narrative perspective often breaks the fourth wall of telling a story.

Illustration by Plunderpuss.

I found out about Wong's story because it won this year's Nebula Award for short story. And I found out about the award through another article about how women swept the awards this year--something especially significant in light of some of the crazy stuff happening in the sci-fi/fantasy world with the other major prize, the Hugo Award. I'm really excited to have found out about Alyssa Wong and will eagerly look up her other writing. "Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers" does something really interesting with Asian American experiences like feeling different from other Americans because of what you eat and creates a fantastical story with monstrous characters that nevertheless plumb the complexities of familial and social relationships that are significant to Asian Americans.

Asian American Literature Fans: Small Press Spotlight X 3 (Four Way, Unnamed Press, and Akashic)

May 23, 2016

Asian American Literature Fans: Small Press Spotlight X 3 (Four Way, Unnamed Press, and Akashic)

In this post, reviews of Rajiv Mohabir’s The Taxidermist’s Cut (2016) and C. Dale Young’s The Halo (2016); Avtar Singh’s Necropolis (Akashic 2016) and Ali Eteraz’s Native Believer (Akashic 2016); Janice Pariat’s Seahorse (Unnamed Press, 2016) and Esmé Weijun Wang’s The Border of Paradise (Unnamed Press, 2016).

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As part of my acknowledgement of this month, I am attempting to amass 31 reviews, so my rate would come out on average to a review a day in the month of May. Counting this post, I will be up to 13 reviews (if I have completed my addition properly). We’ll see if I’m able to complete this challenge, but as part of this initiative, I’m hoping that my efforts might be matched in some way by you: so if you’re a reader and lurker of AALF, I am encouraging you to make your own post or respond to one of the reviews. Would it be too much to ask for 31 comments and/or posts by readers and others? Probably, but the gauntlet has been thrown. LJ is open access, so you can create your own profile or you can post anonymously. I kindly encourage you to comment just to acknowledge your participation in AALF’s readership.

At last count, there were approximately 10 comments from unique users, and 2 reviews by Nadeen Kharputly, putting the community at 12! At the time of this posting, I have completed my 31 review challenge. You still have about 19 comments to go and one week remaining! Go team!

For more on APA Heritage Month, go here:

http://asianpacificheritage.gov/

*****

In this post, I am focusing on three smaller, independent publishers, whose books I have absolutely adored and who deserve way more recognition by readers in general and most certainly from critics, instructors, and scholars.

*****

Spotlight on Four Way Books, with reviews of Rajiv Mohabir’s The Taxidermist’s Cut (2016) and C. Dale Young’s The Halo (2016).

I’ll start out with Four Way Books, which boasts one of the most extensive catalogues that include minority poets. Four Way has been near and dear to my heart, as so many of the collections are grounded in the confessional lyric that first drew me to poetry. Some previous books we’ve already reviewed at Asian American literature fans such as Claire Kageyama-Ramakrishnan’s collections: Shadow Mountain (2008) and her follow up Bear, Diamonds, and Crane (2011). Four Way has also published works by other Asian American authors; we’ll be certain to roll out reviews of other works in the future.

For more on Four Way Books and their catalog, go here:

http://fourwaybooks.com/site/

A Review of C. Dale Young’s The Halo (Four Way Books, 2016).

Well, it’s been an amazing experience just taking some time to dive back into ready poetry. I don’t really understand why I stay away. One of the highlights of this time has definitely been C. Dale Young’s The Halo, which is his fourth collection (after Day Underneath the Day, The Second Person, and Torn). Young’s The Halo is probably his most structurally cohesive collection, both on the level of theme and of form. In this work, he makes great use of a particular poetic structure involving the quintain. I’m not quite sure if this use of the quintain has a specific formal name, as I’m not all that well versed in such things, but the quintain organizes every single poem that appears whether or not there is six stanzas (which is generally the case in most of the poems, giving off a sestina-like geometric structure) or less. The thematic element obviously comes from the title. In this case, Young uses a motif related to a young man’s experience and shame over his status as a human who has somehow sprouted wings. The question that Young never answers, much to our delight, is how to understand this particular issue: is it simply a metaphor for social difference? Is it actually related to the fact that this lyric figure has extra appendages that should allow him to levitate? There’s probably an element of both somewhere in there. On the one hand, you have a poem like “Annunciation,” which seems to suggest a more literal reading of the wings: “I learned to hide my wings almost immediately/ learned to tuck and bandage them down” (8). On the other, you have a poem like “After Crossing the Via Appia,” which gives us this gem: “Because my wings had already erupted from between my shoulder blades. Because I had coveted another man in that secret space in my own head, the lean shape of him, his water-drenched skin as he rose/ from the sea off Fort Lauderdale Beach” (30). Here, Young gives us the chance to connect the sprouting of angel wings and the monstrosity associated with it to queer desire, but this reading is later undercut when the lyric speaker does seem to have a chance to explore his feelings with another man, but discovers that this man does not have wings like he does, so to what then does this angelic form refer? Without answering this question, let us turn to the other issue at hand: the central lyric figure’s story becomes complicated when he is in a car accident and confined to a hospital bed, unsure of whether he is alive or dead. The narrative, or so it seems, is that he was run over by a drunk driver, and lucky to be alive at all. There is a surreal moment when he begins to think that the doctor he sees above him is actually himself sometime in the future, as is noted in the poem “Mind over Matter” when the speaker reveals: “The man standing over me was me” (18). The fissure between reality and fantasy, perception and objectivity is where this book really takes flight, if to pun only briefly: we want this lyric figure to spread his wings and to find a way embrace his winged self. A long-ish poem toward the end, “The Wolf,” involves the central lyric figure in a wrestling match with an actual angel, and so we’re taken back into strongly Biblical territory here. As this lyric Jacob discovers yet again that he is just a mere mortal, stuck with some corporeal abnormality that he wants to desperately to hide, we still want him to find his way in the world and out from the under the weight of his self-denigrations and his burdensome wingspan. What Young’s poetry reminds us is that though things might “get better,” the material effects of social oppression are inescapable and tragically destructive. Love, deep connections, passionate desires can all be all too temporary, so what do we hang onto but by (poetically) remaking our wounds and traumas into something we can live with, to keep us warm and cozy during those long stretches us darkness, to find a way to see what can’t be seen (but so often felt) in the intimate space between our shoulder blades.

Buy the Book Here:

http://fourwaybooks.com/site/halo/

A Review of Rajiv Mohabir’s The Taxidermist’s Cut (Four Way, 2016).

Well, gosh, I know I’ve been terribly behind on reading poetry and reviewing it as well. I always forget how much I’ve needed to read poetry, but it becomes apparent upon the first couple of pages of Rajiv Mohabir’s riveting, eclectic debut The Taxidermist’s Cut. Before I get started on reviewing, I wanted to first alert you to a great interview here:

http://www.connotationpress.com/hoppenthaler-s-congeries/july-2015/2600-rajiv-mohabir-poetry

At one point in this interview, Mohabir relates: “My dissertation will be a collection of poems that charts the historical journey of queer indentured laborers who traveled from India to Guyana as well as the personal: my own journey through cultural identities and surviving homophobias. I hope to put into conversation queer migration under Indian indenture (1838-1917), the whaling industry, and contemporary homophobic and racist violences.” This statement is an excellent way to consider the various forces at play in Mohabir’s collection, which draws on a complicated parental immigrant lineage on the one hand and the lyric speaker’s coming-to-terms with his queer/ racialized background on the other. There is a very interesting interlingual issue at work in this collection, and it made me wonder immediately about Mohabir’s background precisely because it reminded me so much of my own. Poetry comes into being for the child of immigrants often in association with a particular field of reference that is then placed alongside interlingual registers. As I was reading the Taxidermist’s Cut, I kept thinking about how his use of scientific language (especially in relation to plants and animals) and tropes connected to taxidermy in general fall in line with desire to categorize and classify every aspect of our lives down to our identities. What Mohabir so effectively deploys is a hybrid mixture of scientific language and discourses of identity that create a lyric amalgam that wonderfully renders the confusion arising in a queer racialized coming of age: the subject seeks power over his life through the process of naming, yet finds himself often stripped of any sense of security through the illicit nature of sexuality and the strangeness of his racial identity. Here are two of my favorite examples of this kind of “hybrid lyric”:

From “Carolina Wren”

On my mother’s porch, a mother

wren nested amongst Rhododendron roots.

Her eggs hatched into naked skins. I read,

Wrens reject their young if a boy should touch,

or be touched by, another boy but only after

I wrapped it in my fingers. Beginning

To fledge, mother smelled only a child’s

Foreign oils. She abandoned the baby chick (69).

These stanzas show us a really splendid example of lyric equivocation. Here, the lyric speaker is learning a lesson concerning the titular “Carolina wren,” but we’re unsure about how to deal with the italics that signal the “lesson.” On the one hand, the lyric speaker is learning about the problem of touching birds, as the “foreign oils” mark them for expulsion from the nest. On the other, this kind of lesson begins to accrue texture in relation to the development of his social difference: he is foreign in multiple senses of the word. These so-called “oils” of difference mark him perhaps as a figure who cannot be embraced by his family. But because of the ways that the italics are dropped into the poem, we wonder about what the “it” refers to: the indefinite antecedent might at first seem to suggest the boy’s handling of a bird, but given the racialized sexuality of the lyric speaker, the “it” takes on more metaphorical conceits concerning desire and yearning that track throughout the collection. Another wonderful example of the ways that these italics serve to complicate any reading practices appears in “Reference and Anatomy”:

There are many men’s fingertips up and down my own thighs. You ask me their names, so you can stuff them inside me. I smile, They’re all there,

frozen in thick sheets of lake ice, corpses

gossiping about exactly where and for how long

I’ve tongued each man—

You pluck nimbus feathers, to search for

the underlying structure as you position me—

You say anything I say to you is a fairytale” (83).

There’s an intriguing potpourri of mixed metaphors, as the lyric speaker seems to be engaging in an erotic encounter with another man, but the nature of this intercourse is complicated through the problem of naming (a thematic we saw in the previous poem). The “names” being referred to here seem connected to other men and their fingertips, which are somehow dead but animated enough to “gossip.” As with other poems in the collection, the lyric speaker is continually invoked in relation to his bird-like qualities—these “nimbus feathers”—but his social difference marks him as an oddity, something to be examined as spectacle perhaps rather than engaged as an object of beauty rather than a subject of desire. He is being plucked, then stuffed, then filled so as to be displayed, having been hunted perhaps and then transformed as a icon of successful predation: thus, the “fairytale” takes on a darker meaning here, as our lyric speaker finds himself remade into something perhaps both majestic and grotesque at the same time. The Taxidermist’s Cut is a collection that revels in making meaning out of poetic dissonances.

Buy the Book Here:

http://fourwaybooks.com/site/taxidermists-cut/

*****

Spotlight on Akashic Books with reviews of Avtar Singh’s Necropolis (Akashic 2016) and Ali Eteraz’s Native Believer (Akashic 2016)

Another wonderful indie/ smaller press is Akashic Books. They are perhaps most well known for their noir series, but they have also published a number of Asian American and Asian Anglophone author, including Nina Revoyr, Yongsoo Park, and Eric Gamalinda. For more on Akashic, go here:

http://www.akashicbooks.com/

A Review of Avtar Singh’s Necropolis (Akashic 2016).

Avtar Singh’s stateside debut is Necropolis, which is coming out of Akashic Books. This novel was definitely one of my anticipated reads for this year, partly because of the gruesome, but nonetheless intriguing plot description. We’ll let the official blurb over at Akashic briefly take it away from here: “Necropolis follows Sajan Dayal, a detective in pursuit of a serial (though nonlethal) collector of fingers. He encounters would-be vampires and werewolves, and a woman named Razia who may or may not be centuries old. Guided by Singh’s gorgeous and masterful writing, the novel peels back layers of a city in thrall to its past, hostage to its present, and bitterly divided as to its future. Delhi went from being an imperial capital to provincial backwater in a few centuries: the journey back to exploding commercial metropolis has been compressed into a few decades. Combining elements of crime, fantasy, and noir,Necropolis tackles the questions of origin, ownership, and class that such a revolution inevitably raises. The world of Delhi, the sweep of its history—its grandeur, grimness, and criminality—all of it comes alive in Necropolis.” The opening of the novel is superbly gothic, as it explores that aforementioned collector of fingers. Sajan Dayal is on the case, as well as some of his coworkers, including a younger investigator Smita and a faithful stalwart in a man named Kapoor. Dayal, also known as the DCP, discovers that the collector is somehow obsessed with a mysterious woman (the aforementioned Razia). Dayal and his coworkers employ Razia in order to locate the individual who is engaged in the finger severing. As we discover—and here is your spoiler warning—the serial finger collector is none other than some sort of otherworldly creature who is giving these body parts to Razia as a kind of tribute because Razia is apparently a vampire. The fact of Razia’s vampire-hood is something that the novel toys with constantly. Because Singh more or less creates a realist fictional world, the references to werewolves and vampires reconstruct New Delhi as a location that must be reconsidered from the vantage point of the supernatural. Thus, in this particular work, Singh pushes us to link the supernatural with global capitalism, creatures of the night with drug lords, life everlasting with the desire for the urban elite to retain control and power over the proletarian masses. The most compelling point for Singh is the character of New Delhi, a place that has become a strange amalgam of the ancient and the supermodern, a place that therefore is the perfect one to generate a speculative fiction and a noir-ish narrative. The pacing of the novel is unfortunately uneven because Singh uses Razia and the finger collector as more of a framing device. The middle chapters turn to individual cases that the DCP and his followers must investigate. The structure ends up mimicking the investigatory serial procedural—reminiscent indeed of shows you might watch such as Bones or Castle—in which there are individual mysteries, which are sometimes linked by a larger one. The opening is such a seductive one that when we’re forced to move away from Razia and her possible vampire background, these other plots can seem like diversions, even as they accrue an important texture for understanding the larger forces that Singh is grappling with concerning urban decay and decadence, poverty and exploitation, corruption and wealth accumulation. Despite these momentum bumps, the novel is a compelling one and certain to be a great addition to courses on detective fiction and noir, especially given its focus on a city that has not necessarily or traditionally been attached to mystery and mayhem. Singh is giving places like Los Angeles and San Francisco a run for their money in this re-envisioning of the urban noir.

For more on the book as well as a purchase link, go here:

http://www.akashicbooks.com/catalog/necropolis/

A Review of Ali Eteraz’s Native Believer (Akashic, 2016).

Before I get started on this review, I wanted to send a huge thanks to NKharput for her reviews of Ali Eteraz’s Native Believer and Ayad Akhtar’s The Who and the What!

Please go here for those reviews:

http://asianamlitfans.livejournal.com/182538.html

Ali Eteraz’s Native Believer is his fiery debut novel, which reminds me a bit of the work of Ayad Akhtar and Mohsin Hamid in its provocative consideration of what it means to be Muslim in the United States. Eteraz is author of at least two other major publications, including the memoir Children of Dust (reviewed here in AALF awhile back) and then the short story collection Falsipedies and Fibsiennes (Guernica Editions, 2014). As I was reading up on Eteraz’s updated bio, the amazon site reveals this kernel: “Recently, Eteraz received the 3 Quarks Daily Arts & Literature Prize judged by Mohsin Hamid, and served as a consultant to the artist Jenny Holzer on a permanent art installation in Qatar.” I can’t say I’m surprised by the fact that Hamid and Eteraz have made their connection given the many obvious thematic and tonal parallels between their fictional works. Native Believer opens up with a party thrown by the narrator (known as M), who is a non-practicing South Asian Muslim and his wife (Marie-Anne), who is Caucasian. This party is important for the narrator based upon his work in a public relations firm; he needs to show the right amount of social graces to help cement his place in a company that would allow him room to advance. But it is also during this party that a senior colleague notices something stowed up high on a bookshelf: it’s the Koran, something that his mother placed there before she passed away. While the narrator believes this moment to be a relatively meaningless interaction, there is a question as to the import of this moment when he finds out he is fired from his job soon after. Did his senior colleague find his copy of the Koran to be evidence of some unpatriotic impulse? While he mulls over this question, he wallows in the wake of his unemployment. Meanwhile, his wife is struggling with her own career advancement in a sales company. She ends up trying to throw side projects the narrator’s way, as a means to keep him busy and perhaps to offer him entry into a new line of work. As the narrator continues to look into other job positions and freelance work, he meets up with a variety of salty and complicated characters, including a Muslim firebrand named Ali Ansari and a former co-worker named Candace, with whom the narrator embarks on an affair. Eteraz is going for quite a bit of shock value in this work, and part of the point is to undermine what it means to be both Muslim and American and to challenge any reductive positioning of Islamic fundamentalism and secularism. Readers should be forewarned that there are a lot of scenes involving sex both in graphic and comic ways. The title is thus ironically invoked: our narrator is a “native believer” insofar as he’s American and understands that his distant religious background will ultimately cause others to consider him as part of a “residual supremacist” group that will bring the nation to ruin. The concluding arc makes us wonder about the primacy of the romance plot to this kind of narrative, which seems to making larger claims about what constitutes the “brown body” in the post-9/11 moment. Those readers who have been following this larger body of work will necessarily position this novel as part of a masculinist ethos that can be seen in the writings of the aforementioned Hamid, and others such as H.M. Naqvi and Ayad Akhtar. I’ve been wondering about the gendered phenomena that tend to polarize the cultural productions, and it would be interesting to consider works such as Naqvi’s Home Boy, Akhtar’s American Dervish, and Eteraz’s Native Believer in contrast to fictions such as Nafisa Haji’s The Writing on my Forehead and Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Queen of Dreams. Certainly, an incendiary novel; one wonders how it will be received in Muslim majority countries.

For another useful review, please go to Kirkus Reviews:

https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/ali-eteraz/native-believer/

Buy the book Here:

http://www.akashicbooks.com/catalog/native-believer/

*****

Spotlight on Unnamed Press with reviews of Janice Pariat’s Seahorse (Unnamed Press, 2016) and Esmé Weijun Wang’s The Border of Paradise (Unnamed Press, 2016).

Finally, one of the newest presses that I have been introduced to is Unnamed Press, which has put out two of the most surprising and wonderful reads for me this year, but they are also the publisher of many other Asian American and Asian Anglophone authors, including Ranbir Sidhu and Kristine Ong Muslim (I hope to review these in the future. For more on the offerings over at Unnamed Press, go here:

A Review of Janice Pariat’s Seahorse (Unnamed Press, 2016).

Wow, this novel was a real surprise for me. Janice Pariat’s debut novel Seahorse (she is also the author of a short story collection, which has not been published stateside and thus the subject of frustration for me as always) was the second book I read out of Unnamed Press. At this point, I’ll make the typical spoiler warning for those that do not want to hear more about the plot. To that end, we’ll let the official web page over at Unnamed Press do some plot work for us: “The seahorse is the only creature where the male is responsible for reproduction. Male seahorses bear their burdens, as does our protagonist Nem, a hero driven by his decades-long love for Nicholas, whom he met at a University in 1990s Delhi. Nem was not like his classmates, crowding around a TV set to watch music videos and talk about ‘doing it’; instead he opted for lonely walks around ruins. On one of these occasions he spied Nicholas, an enigmatic young professor from London, in the park with another male student. With surprising ease, Nem seduces the much sought-after professor. It is in the wake of this brief but steamy affair, when Nicholas returns to London and Nem tries to continue with his life, that the story truly begins. Nem graduates from university and becomes a successful art critic, but his memories of Nicholas dominate his existence. After an invitation to speak at a conference in London, Nem's obsession with Nicholas returns. Still single, Nem wonders if this will be the opportunity to reconnect with his old and influential lover. Instead, Nem is immediately swept up in London's cosmopolitan world, hobnobbing with the city's diverse artists and writers and enjoying the London club scene. Meanwhile, Nicholas artfully avoids any direct contact with Nem, instead orchestrating a series of clues that lead to Myra, a woman Nem had believed to be Nicholas's sister. Brought together by their love for Nicholas, Nem and Myra begin a friendship with surprising consequences.” So this summary provides a great deal of context for the story, but does leave out Pariat’s wonderfully poetic prose. She further employs first person narration to great effect, as she delves into Nem’s lovelorn melancholic subjectivity. The novel moves back and forth between two time periods. The diegetic present involves Nem’s time in London, trying to track down Nicholas. Instead of bumping into Nicholas, Nem bumps into Myra, who Nicholas discovers is not actually Nicholas’s sister, as she is first introduced to him in that capacity. In the diegetic past, Nem tell us about his quixotic involvement with Nicholas, which occurs mostly over a holiday period in India. Nem and Nicholas’s days revolve around lovemaking, wine and cheese consumption, and explorations on the topic of art, philosophy and the humanities. These sequences are some of the most poetic and elegant of the work and thus are pivotal in constituting why Nem would be driven to go to London in search of someone like Nicholas. In Myra, Nem ultimately finds a kindred spirit, someone torn asunder by love and affected by its incredible loss. The concluding sequence I found surprising, but Pariat is working within the confines of a complicated dynamic of desire that confounds any easy conceptions of gender and sexuality. The last two pages I especially found infuriating because of the way they are ambivalently staged and which possess a kind of non-sequitor-like quality that made me immediately want to grab someone who had already read the book to discuss what these pages meant. On the other hand, despite my gut reaction to the conclusion, it didn’t overturn my overall sentiment about this work, as it reminded me of many other novels that deal with obsession and love, even in the most complicated and thorniest of circumstances. Another recommended read.

For more information on the book, go here:

For a purchase link, go here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/seahorse-janice-pariat/1122089888

A Review of Esmé Weijun Wang’s The Border of Paradise (Unnamed Press, 2016).

So, I’ve been trying to do a better job of keeping track of small/ indie press offerings, and as part of that effort, I’m reviewing Esmé Weijun Wang’s intriguing and complex debut, The Border of Paradise. The official site over at Unnamed Press gives us this pithy description of the novel, but I am providing you with a spoiler warning here, so do not read further unless you want some major details revealed: “In booming postwar Brooklyn, the Nowak Piano Company is an American success story. There is just one problem: the Nowak’s only son, David. A handsome kid and shy like his mother, David struggles with neuroses. If not for his only friend, Marianne, David’s life would be intolerable. When David inherits the piano company at just 18 and Marianne breaks things off, David sells the company and travels around the world. In Taiwan, his life changes when he meets the daughter of a local madame — the sharp-tongued, intelligent Daisy. Returning to the United States, the couple (and newborn son) buy an isolated country house in Northern California’s Polk Valley. As David's health deteriorates, he has a brief affair with Marianne, producing a daughter. It’s Daisy's solution for the future of her two children, inspired by the old Chinese tradition of raising girls as sisterly wives for adoptive brothers, that exposes Daisy’s traumatic life, and the terrible inheritance her children must receive. Framed by two suicide attempts, The Border of Paradise is told from multiple perspectives, culminating in heartrending fashion as the young heirs to the Nowak fortune confront their past and their isolation.” The element that I found perhaps most fascinating about this novel was the use of alternating first person perspectives across a wide historical swathe. The novel first begins David and Daisy’s perspectives, but later shifts to their children: William and Gillian. Wang continues to complicate the narratorial equation by later adding the perspectives of Marianne and Marianne’s brother. After I finished the novel, I didn’t think of the work as being framed by suicide attempts exactly, especially because the conclusion is far more murkier than the description conveys, but the novel is an impressive and complicated depiction of mental illness as it tracks across generations. There is a point where I got a vaguely Faulknerian impression of this novel, as William and Gillian must live in a home that becomes gothically rendered. What’s perhaps most terrifying about the novel, and a true testament of Wang’s talent, is that you don’t necessarily see right away how deep the problems these characters possess actually run because they are so good at rationalizing all of the dysfunctionality going on around them. Wang makes an interesting choice in the last chapter to narrate it from the third person perspective, and I wondered what encouraged her to go in that direction since she so effectively used the first person throughout the rest of the novel. I especially found Marianne and Marianne’s brother’s characters to be vital to the impact of the novel because they clarify what a dire situation that William and Gillian eventually find themselves in. I wasn’t too keen on the title, though the novel is definitely one meriting multiple reads and certain to be an excellent choice for classroom discussions.

For more on the book go here:

For a purchase link, go here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-border-of-paradise-esme-weijun-wang/1122615831

*****

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

AALF is maintained by a number of professional academics and scholars, including Paul Lai (pylduck@gmail.com), who is the social media liaison and expert. Current, active as well previous reviewers have included (but are not necessarily limited to):

Sue J. Kim, Professor, University of Massachusetts, Lowell

Jennifer Ann Ho, Professor, UNC-Chapel Hill

Betsy Huang, Associate Professor, Clark University

Nadeen Kharputly, PhD Candidate, UC San Diego

Annabeth Leow, Coterminal MA Student, Stanford University

Asian American Literature Fans can also be found on other social networking sites such as:

Goodreads (with a bad heading because it is not Stephen Hong Sohn’s blog):

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/1612536.Stephen_Hong_Sohn/blog

Twitter:

https://twitter.com/asianamlitfans?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor

LibraryThing:

http://www.librarything.com/profile/asianamlitfans

Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/Asian-American-Literature-Fans-147257025397976/

May 22, 2016

On Muslim American fiction, secularism, and the burden of responsibility

I am perpetually confounded by the state of the Muslim American literary canon: it seems near impossible to find a Muslim American character who is simply unextraordinary. The canon is replete with violent, misogynist, and crude caricatures. I had so much hope for Native Believer: it begins with a protagonist who seems wholly unassuming. His relationship with his wife is endearing: when she’s stuck in the bathroom at their own party in need of a tampon, the narrator states, "but her issues are my issues too” in response to a guest who asks him if she’s dealing with a “women’s issue.” He wants more than anything to have children but they are unable (for reasons that complicate and shock over the course of the narrative). The prose is humorous and delightful.

But larger issues dramatically shift the storyline: the narrator's relationship with Islam, which was almost nonexistent before this particular moment, takes over when his boss fires him for not only owning a copy of the Koran but also placing the book higher than Nietzsche on the bookshelf, which the boss takes as a symbolic displacement of Western culture by Islamic extremism. In search of what it means to be a Muslim American (even while rejecting that identity), the narrator, known only as M. (but implied to be Muhammad) falls in with a young crowd called the Gay Commie Muzzies who are recklessly debauched, which shifts the notion of what it means to be a radical Muslim. He conducts an affair with an African American woman who, unlike many in the mid-twentieth century, converts to Islam in order to reject the burden of her parents' racial pride. He encounters a number of Muslim American State Department employees — of the sort who travel abroad to prove that Muslims are assimilated in the US. His search for Muslim Americans who can give him a sense of identity yields nothing but a diverse range of characters who feel crudely drawn. The narrator himself devolves into a vengeful monster by the end of the story. Disappointed as I am with the parade of vasty unlikeable caricatures, the author does illustrate the various ways in which it is possible to be a secular Muslim. I just wish the characterizations weren’t so extreme.

The Who and the What is an older work but raises some of the same questions as Eteraz with regard to the burden of portraying Muslims (secular or not). It is Ayad Akhtar's second play since the Pulitzer Prize-winning Disgraced. Like Disgraced, The Who and the What revolves around a debate about religion: a book about the Prophet Muhammad that is thought to be incendiary. Akhtar's works offer a fascinating lens into what it means to be a Muslim in America in the post-9/11 age: that includes a discussion of what it means to be a secular Muslim, which has yet to be a widely accepted notion by Muslims and non Muslims alike.

Now, Akhtar is the foremost voice in Muslim American drama today: in addition to garnering the Pulitzer, Disgraced was the most produced play in the 2015-2016 season, according to American Theatre. What kind of responsibility -- and, conversely, freedom -- comes with this distinction? This question is very unfairly posed to Muslim American artists of this age. It is also at the heart of The Who and the What: Zarina's book on the prophet -- a book that illuminates how his "contradictions only make him more human" -- is published at the expense of familial harmony. Some critics have wondered whether Akhtar published Disgraced at the expense of the Muslim American community, since his representations of the community are far from flattering. Which goes to say: how is literary or artistic production regulated in the hands of the Muslim American artist, especially in the post-9/11 era?

The Who and the What features an all-Muslim cast: the headstrong yet obedient Zarina, her sister Mahwish, who desperately wants to wed her longterm boyfriend (yet cannot do so until Zarina, her elder, is married), their father, Afzal, whose overcontrolling tendencies stem from the loss of the family matriarch, and Eli, a white Muslim convert that Afzal sets up with Zarina. The diversity of the cast illuminates all the different ways one can be Muslim. Unfortunately, it also presents caricatures that recall unfortunate stereotypes about controlling, misogynist, violent men. The play -- and his other works -- makes you wonder what on earth Akhtar, now vastly prominent as a playwright, is trying to do with his representations of Muslim American characters. But that question is one that unfairly burdens artists of color who are taken to be representatives of their communities. So how do we look past these base questions when examining the works of Muslim American writers? Akhtar has given us the opportunity to begin, at the very least.

May 17, 2016

Asian American Literature Fans – Press Spotlight: Visual Cultural Productions – May 18, 2016

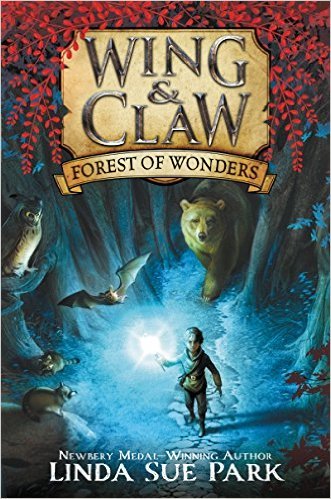

In this post, reviews of: Tiger in my Soup by Kashmira Sheth (writer) and Jeffrey Ebbeler (illustrator) (2013, hardcover, Peachtree Publishers); Sona and the Wedding Game by Kashmira Sheth (writer) and Yoshiko Jaeggi (illustrator) (2015, hardcover, Peachtree Publishers); Yumi Sakugawa’s I Think I Am in Friend Love With You (Adams Media, (2013); Yumi Sakugawa’s Your Illustrated Guide to Becoming One with the Universe (Adams Media, 2015); Yumi Sakugawa’s There is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons (Adams Media, 2016); Kazu Kibuishi’s Firelight (Amulet #7) (Scholastic Press, 2016); Gene Yang (author) and Mike Holmes’s (illustrator) Secret Coders (First Second 2015).

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As part of my acknowledgement of this month, I am attempting to amass 31 reviews, so my rate would come out on average to a review a day in the month of May. Counting this post, I will be up to 13 reviews (if I have completed my addition properly). We’ll see if I’m able to complete this challenge, but as part of this initiative, I’m hoping that my efforts might be matched in some way by you: so if you’re a reader and lurker of AALF, I am encouraging you to make your own post or respond to one of the reviews. Would it be too much to ask for 31 comments and/or posts by readers and others? Probably, but the gauntlet has been thrown. LJ is open access, so you can create your own profile or you can post anonymously. I kindly encourage you to comment just to acknowledge your participation in AALF’s readership.

For more on APA Heritage Month, go here:

http://asianpacificheritage.gov/

*****

This post is focused on visual cultural productions of numerous kinds, including children’s picture books, graphic novels, and illustrated guides. As with the previous post on young adult fiction, I tend to gravitate toward visual/ textual cultural productions when my mind needs a break from more traditional reading. I wanted to provide a mix of different kinds of visual cultural productions. I’ve definitely taken a break from reviewing children’s picture books, so I figured that I should include some here.

On to the reviews:

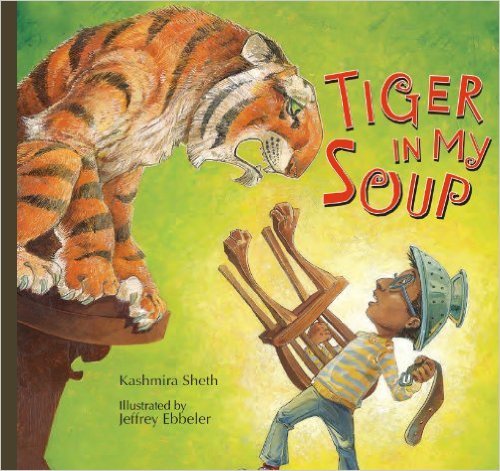

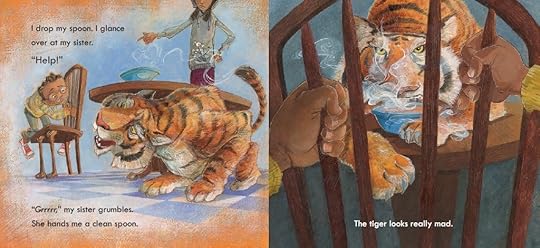

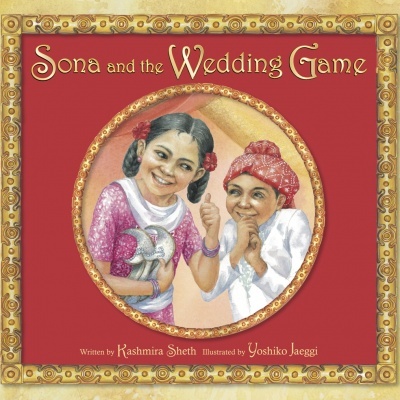

A Review of Tiger in my Soup by Kashmira Sheth (writer) and Jeffrey Ebbeler (illustrator) (2013, hardcover, Peachtree Publishers) and a review of Sona and the Wedding Game by Kashmira Sheth (writer) and Yoshiko Jaeggi (illustrator) (2015, hardcover, Peachtree Publishers)

So, I haven’t reviewed children’s picture books in awhile, and I wanted to catch up on a couple coming out of Peachtree Publishers. The first is Tiger in my Soup, which is penned by Kashmira Sheth and illustrated by Jeffrey Ebbeler. The back cover provides a useful and pithy plot summary: “Sometimes it’s impossible to get your big sister to read your favorite book to you. But if you’re really creative and use your imagination, you might just get what you want. Take care, though, not to go too far. Once you conjure up a tiger, there’s no telling where it might lead.”

The story relies upon the imaginative depictions offered by Jeffrey Ebbeler, which provides the right balance of menace and entertainment. What is interesting about this story for readers of AALF is the fact that the characters seem to be ethnically marked, but are not definitively determined to be so, either through dialogue or textual information. I wondered about the reasoning for this kind of depiction, and the rationale behind it. In any case, on the brief plotting level, the book does a wonderful job considering how a child’s imagination might run wild, to the point that tigers seem to come to life. For the target readers, such a whimsical world of fantasy run gleefully amok will certainly be amusing.

Buy the Book Here:

http://peachtree-online.com/index.php/book/tiger-in-my-soup.html

Whereas Tiger in my Soup was not so specific about ethnic or cultural contexts, Sona and the Wedding Game goes in the exact opposite direction. The inside cover of the hardcover edition provides us with some useful background information: “Sona has been given an important job for her big sister’s wedding: she has tot steal the groom’s shoes. She’s never attended a wedding before, so she’s unfamiliar with this Indian tradition – as well as many of the other magical experiences that will occur before and during the special event. But with the assistance of her know-it-all cousin Vishal, Sona finds a way to steal the shoes and get a very special reward.” Sheth has her work cut out for her because she needs to be able to render the story legible to young readers, while also maintaining ethnographic accuracy. Part of the success is reliant upon Jaeggi’s artistic style, which is far more realist in its approach than the more cartoon-ish drawings that Ebbeler appropriately provides for Tiger in my Soup. But Sheth also has to rely on more text and a detailed author’s note to give parents more information, which may be important to relay given questions that may come up during the reading experience. Again, it’s really amazing to see these kinds of picture books available these days; I can’t recall having access to such books when I was a young child.

Buy the Book Here:

http://peachtree-online.com/index.php/book/sona-and-the-wedding-game.html

A Review of Yumi Sakugawa’s I Think I Am in Friend Love With You (Adams Media, (2013); Your Illustrated Guide to Becoming One with the Universe (Adams Media, 2015); and There is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons (Adams Media, 2016).

I absolutely adored I Think I Am in Friend Love with You for the simply reason that the English language is so terrible about finding a way to move beyond the binaries of friend and lover, acquaintance and family member. I have often found my friendships to be as deep and as meaningful as any other connection I have made; love is certainly part of that equation, but not necessarily a romantic love. Thus, I really found Yumi Sakugawa’s I Think I Am in Friend Love With You to explore this strange liminal space of the “friend love.” As with Sakugawa’s other works, I am always reminded of Spirited Away, as Sakugawa typically uses anthropomorphic blob-like cartoons, which nevertheless seem appropriate because she’s always exploring feelings and emotions. I have to believe that many of us are in “friend love” or at least have strong platonic relationships that might be better categorized as something akin to family, but again, we have yet to develop the kind of language to mark precisely these connections. As a final note, I did end up reading selections of this piece to a person who I consider to be a “friend love,” and it was an entertaining experience.

Your Illustrated Guide to Becoming One with the Universe is another publication that offers more philosophical musings that are accompanied by visuals that tend to be cartoon-like. I found this particular work to be probably the most mystical in its orientation. It tends to suggest that there is some larger energy force at work that we can all tune into, if we only give ourselves enough attention to the world around us. I don’t know if I necessarily agree with this premise, but I have read some other works on mindfulness, especially as it relates to meditation, and I did find Sakugawa’s points to parallel these others. In this sense, her work attends to the necessity of slowing down and taking pleasure in finer moments when one can. Thus, this mindfulness enables to one to finding the path to becoming one with the universe. The various exercises that Sakugawa suggests that readers engage in seem a little far out for me, but I appreciated the unique perspective being offered here.

So, I was compelled to write up a short review of There is No Right Way to Medidate: And Other Lessons just because I do engage some meditation primarily through yoga. Though many are skeptical of yoga (especially at first) due to orientalist appropriations, which I can understand, I have found the practice of yoga to be beneficial for two primary reasons: the focus on the breath AND the time that I have to devote to stretching (and I am still extremely inflexible after 6 years of regular practice, going around 3 times a week, sometimes more). Yumi Sakugawa’s There is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons takes as its topic the focus of meditation but explores this issue through a visual form that is reminiscent of Lynda Barry’s work (especially the “demons” visual project that Barry engaged). So much of meditation is about moving beyond your thoughts, which tend to be negative. Sakugawa draws this “negative energy” as a kind of black cloud monster who comes and feeds off of what Sianne Ngai might call “ugly feelings.” Meditation in whatever form lets you get away from your thoughts, so you can just be one with the breath. It’s difficult; I can’t ever meditate for more than a handful of minutes at a given time, but when it’s working, I feel so much better and so much more centered. What Sakugawa’s work adds to this kind of practice is a visual schema to understand why it is you need to meditate and injects a little bit of humor into encouraging us all to be a little bit more mindful, so that we can go about our day with less emotional and psychic baggage. A fun and cute production from Adams Media.

Buy the Books Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/i-think-i-am-in-friend-love-with-you-yumi-sakugawa/1117074320?ean=9781440573026

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/your-illustrated-guide-to-becoming-one-with-the-universe-yumi-sakugawa/1119640547?ean=9781440582639

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/there-is-no-right-way-to-meditate-yumi-sakugawa/1122472599

A Review of Kazu Kibuishi’s Firelight (Amulet #7) (Scholastic Press, 2016).

Well, I absolutely adore Kazu Kibuishi’s Amulet series, but I am seriously beginning to wonder about whether or not we will ever see its ending. Perhaps, it shouldn’t have one, but the conclusion to Amulet #7 makes us realize that there could be many, many more installments to go before we see what happens to Emily and Navin, and their adventures in this fantastic world of mechanized droids, talking animals, dark elves, and stonekeepers. The very sparse overview over at B&N gives us this description: “Emily, Trellis, and Vigo visit Algos Island, where they can access and enter lost memories. They're hoping to uncover the events of Trellis's mysterious childhood -- knowledge they can use against the Elf King. What they discover is a dark secret that changes everything. Meanwhile, the Voice of Emily's Amulet is getting stronger, and threatens to overtake her completely.” I don’t really know if there is really a “dark secret that changes everything.” Pretty much everything we’ve been worrying about is taking effect and our central question remains the same: will Emily be able to control the power inherent in the stone or is she a pawn in some larger game. While B&N’s description focuses on Trellis’s childhood, in some ways, this particular installment is far more about Emily’s childhood and her melancholic attachment to her father. This connection is the one that we fear may turn Emily to the darkside. But the plot description completely fails to mention Navin’s subplot wherein he and his merry band of adventurers are working to reunite with the Resistance. An entertaining sequence involves Navin and his allies toiling in a skyship restaurant, but that’s merely dressing on the larger issue involving Navin and his quest to repel the forces of darkness alongside his mother and other faithful allies. As much as I am a fan of Kibuishi’s work, his tremendous output, and his regular installments, I do hope that the longer arc of this work will find a more original resolution. I’m already seeing it move toward that common “masterplot” I’ve seen in other comic books in which a good person becomes bad, who then must be defeated by someone the formerly good person loved (such as a brother in this case). The question in such plots is whether or not the formerly good person will end up living after the final cataclysmic battle, so I hope Kibuishi pulls the rug from out of under our readerly feet. He’s already staged a number of surprises, especially with the dark elves, so keep those twists and turns coming.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/firelight-kazu-kibuishi/1122377201

A Review of Gene Yang (author) and Mike Holmes’s (illustrator) Secret Coders (First Second 2015).

So, somehow I missed this publication when it originally came out, but Gene Yang is back, this time with Mike Holmes at the illustration helm with Secret Coders (First Second 2015). Our trusty summary over at B&N will get this review started: “Welcome to Stately Academy, a school which is just crawling with mysteries to be solved! The founder of the school left many clues and puzzles to challenge his enterprising students. Using their wits and their growing prowess with coding, Hopper and her friend Eni are going to solve the mystery of Stately Academy no matter what it takes! From graphic novel superstar (and high school computer programming teacher) Gene Luen Yang comes a wildly entertaining new series that combines logic puzzles and basic programming instruction with a page-turning mystery plot!” The biographical note that the summary provides is important in part because Yang’s point is to use this graphic novel as a method to teach readers about the basics of coding, especially in relation to binary code. Hopper arrives at Stately Academy as the proverbial new student who is looking to make friends. Though she has interests in basketball and seems to be relatively socially grounded, she finds it difficult to make new friends, which makes it all the more fortuitous when she strikes up a connection with Eni, the local basketball star. But, as they get to now each other, a central mystery emerges from the school’s supply closet/ tool shed (which is locked). After finding a way in, they come upon a programmable turtle, which is set to clean the grounds using a particular sequence of instructions, but these instructions can also cause strange birds (with multiple eyes) to attack. If this plot device seems bizarre, then you must be forewarned: there is something amiss at this school, as it is filled with electronic animals and robots as well as sallow looking people coming out of the principal’s office. Yang adds another interesting element into the plot by unveiling the fact that Hopper, who is drawn with racially ambiguous features, is the daughter of the Chinese language instructor, Mrs. Hu. To be sure, we are not given information about whether or not she is the biological offspring of Mrs. Hu, but Yang is clearly having some fun with the complicated issue of representing race in graphic form. Holmes’s illustrations pair well with Yang’s scribing efforts. For adult readers, Secret Coders might come off a bit frustrating, as the narrative is so short. This brevity is no doubt due to the fact that this work is being broken up into multiple installments, and this first portion naturally ends on a cliffhanger. Stay tuned, so shall we all.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/secret-coders-gene-luen-yang/1120506611

*****

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

AALF is maintained by a number of professional academics and scholars, including Paul Lai (pylduck@gmail.com), who is the social media liaison and expert. Current, active as well previous reviewers have included (but are not necessarily limited to):

Sue J. Kim, Professor, University of Massachusetts, Lowell

Jennifer Ann Ho, Professor, UNC-Chapel Hill

Betsy Huang, Associate Professor, Clark University

Nadeen Kharputly, PhD Candidate, UC San Diego

Annabeth Leow, Coterminal MA Student, Stanford University

Asian American Literature Fans can also be found on other social networking sites such as:

Goodreads (with a bad heading because it is not Stephen Hong Sohn’s blog):

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/1612536.Stephen_Hong_Sohn/blog

Twitter:

https://twitter.com/asianamlitfans?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor

LibraryThing:

http://www.librarything.com/profile/asianamlitfans

Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/Asian-American-Literature-Fans-147257025397976/

May 14, 2016

Asian American Literature Fans – Spotlight on the Second Books Club – May 15, 2016

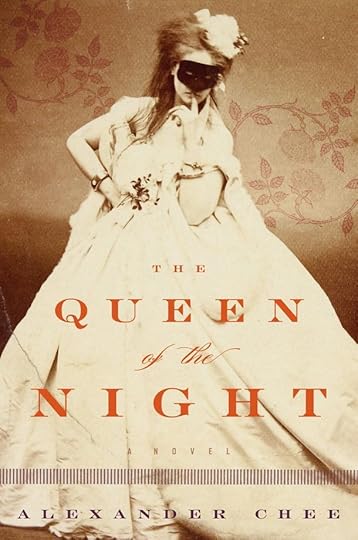

In this post, reviews of: Zoë S. Roy’s Butterfly Tears (Inanna 2009); Janice Y.K. Lee’s The Expatriates (Viking 2016); Ken Liu’s The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories (Saga Press, 2016); Shawna Yang Ryan’s Green Island (Knopf, 2016); Alexander Chee’s Queen of the Night (Houghton Mifflin, 2016); Brian Ascalon Roley’s The Last Mistress of Jose Rizal: Stories (Curbstone Books, 2016).

Mary 14, 2016

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As part of my acknowledgement of this month, I am attempting to amass 31 reviews, so my rate would come out on average to a review a day in the month of May. Counting this post, I will be up to 13 reviews (if I have completed my addition properly). We’ll see if I’m able to complete this challenge, but as part of this initiative, I’m hoping that my efforts might be matched in some way by you: so if you’re a reader and lurker of AALF, I am encouraging you to make your own post or respond to one of the reviews. Would it be too much to ask for 31 comments and/or posts by readers and others? Probably, but the gauntlet has been thrown. LJ is open access, so you can create your own profile or you can post anonymously. I kindly encourage you to comment just to acknowledge your participation in AALF’s readership.

At last count, excluding the comments made by Pylduck; five unique users have responded with comments. Latest APA Heritage Month Tally:

Me = 19 reviews; You = 5 comments! A much better stat! Keep it up! Let’s hope you guys can match the 31 posts/ comments =). I’m totally behind you!

For more on APA Heritage Month, go here:

http://asianpacificheritage.gov/

*****

This post focuses on an author’s second major full-length publication (at least according to my preliminary research). I apologize if any of these writers are mislabeled according to this category. I often use this category in general because I have been waiting a long time (impatiently HAHA) for a book to come out. Two writers on this list (Brian Ascalon Roley and Alexander Chee) are favorites of mine for their first books, so it is with only the highest pleasure that I review their subsequent publications. I’m still waiting on le thi diem thuy to publish the “second novel we are all looking for,” but that’s neither here nor there. If anyone does know the status of le’s future work, please do comment, because I’ve love to know what’s going on there. But, enough babble… on to the reviews!

A Review of Zoë S. Roy’s Butterfly Tears (Inanna 2009).

So, I’ve been reading through Zoë S. Roy’s Butterfly Tears, which is a short story collection. Roy is already the author of a third publication, but Butterfly Tears happens to be her second, so I am including it as part of this larger review post. I was immediately drawn to this work because of its focus on a general theme concerning Chinese women who are struggling with changing cultural values in light of modernization, especially in the period following the Cultural Revolution. The stories further show transnational verve, as characters travel from China to the United States or to Canada. The diasporic character of these migrations adds an extra level of instability to the lives of these female principles. Much of the stories involve star-crossed romances. In terms of literary taxonomies, Butterfly Tears is an intriguing example of a truly transnational and Asian North American work, as stories are set primarily in three countries: China, Canada, and/or the United States. The opening and title story, “Butterfly Tears” involves a protagonist (and Chinese migrant) named Sunni who realizes that her marriage to her husband may be on the rocks. Roy effectively uses analeptic intercuts to show us how moments in the past bring the diegetic present into better light: we see how young Sunni (growing up in China) reacts to the life story of Crazy Wen, a musician whose own romance was prematurely terminated. The fable of Crazy Wen allows Sunni to reconsider her adult life through a new perspective. Though Sunni is devastated when she discovers her husband’s infidelity, she understands that she cannot simply give up: she must keep herself together because other people rely on her and, for instance, she still needs to be a responsible parent. The third story, “Yearning,” is notable for the fact that it would become the basis of Roy’s next publication, Calls Across the Pacific. One of my favorite stories was “Balloons,” which offers Roy the opportunity to explore familial reunions amid the context of internet technologies. I especially was drawn to this piece because it was longer than many of the other stories and the characters have lengthier developmental arcs. The main character here, Suyun, eventually connects with a relative over the internet and realizes that her father’s brother may actually be alive. I found this story to be additionally intriguing because Roy employs a number of different discursive techniques to tell the tale, most notably the use of embedded letters and e-mails. “Twin Rivers” was also another standout for me, but also one of the most depressing stories, as the title character Jiang suffers from a disability that limits the use of one leg. As she adapts to life in Canada, she becomes the subject of a problematic romance with a man who is already married, leading her down a destructive path of obsessive behavior. Here, Roy works within the frame of the limited life options and paths for Chinese women even in the context of transnational migration. In “A Mandarin Duck,” Roy varies the theme of strained romantic relationships by exploring how a woman Huidi (with a son named Wade) attempts to make a new life in the shadow of an abusive relationship. And I’ll end with “Fortune-telling,” which seems to suggest the possibility of a same sex romance between its principle characters, but never fully explores this line of queer desire. If there is a critique to be made of some of the stories, it’s that I sometimes simply wanted to read further into a character’s life, but that’s the frustration of this form: you can’t always get much more than a brief, punctuated glimpse. The staccato cadences of Roy’s collection still finds a general adherence through the themes of Chinese female life paths and thus it might be better to regard Butterfly Tears as a loosely linked story cycle. Roy’s collection certainly can be taught alongside a number of others, and I especially see that this work would resonate alongside others with strong Chinese diasporic and transnational sentiments; these include Yiyun Li’s Gold Boy, Emerald Girl, Ha Jin’s A Good Fall, and Xu Xi’s Access.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/butterfly-tears-zoe-roy/1014900328?ean=9780978223373

A Review of Janice Y.K. Lee’s The Expatriates (Viking 2016).

As a note, I always make a quick comment before any Penguin title to plug their CFIS program which gives qualified instructors 5 free exam copies per year. Because of this policy, I have been easily able to add new books to my courses routinely. The CFIS staff are wonderfully responsive and Penguin has the best exam copy hands down of any of the major presses. W.W. Norton is probably just behind.

For more on CFIS, go here:

http://www.penguin.com/services-academic/cfis/

While dealing with the flu this past winter, I read Janice Y.K. Lee’s The Expatriates, perhaps one of the perfect novels to have when you have a lot of time in bed. The plot is totally immersive and is certain to be picked up by book clubs, especially ones seeking female driven plots concerning motherhood. We’ll let B&N (as always) provide the basic scaffolding of the novel’s contents: “Mercy, a young Korean American and recent Columbia graduate, is adrift, undone by a terrible incident in her recent past. Hilary, a wealthy housewife, is haunted by her struggle to have a child, something she believes could save her foundering marriage. Meanwhile, Margaret, once a happily married mother of three, questions her maternal identity in the wake of a shattering loss. As each woman struggles with her own demons, their lives collide in ways that have irreversible consequences for them all. Atmospheric, moving, and utterly compelling, The Expatriates confirms Lee as an exceptional talent and one of our keenest observers of women’s inner lives.” The “expatriate” aspect of these three characters is that they have all moved to Hong Kong. Hilary Starr (not racially marked) and Margaret Reade (1/4 Korean) are wives of serious businessmen. Hilary and her husband David have been struggling to have a baby for eight years, and they are contemplating adopting a child who is of part Chinese part Indian (South Asian) background, but Hillary’s narrative is perhaps the least compelling and the least threaded of the three primary characters. Margaret Reade hires Mercy Cho to be the family’s babysitter. At that point, Mercy is pretty much moving from one job to another, so the possibility of stable finances draws her in to the orbit of the Reade’s. Mercy travels with the family to Seoul; Margaret immediately realizes that Mercy is not the best babysitter, but passes off her paranoia as being an overprotective parent. But (and spoilers forthcoming here) her intuition seems to be correct, as one day she, Mercy, and the three kids are in a market area and lose sight of the youngest (named G) for just a couple of seconds. G is gone, and much of the narrative is cast in the pall of his absence. Margaret (and her family) is trying to recover, while Mercy is trying to forget this past. Their lives begin to creep slowly back toward each other, but in the most subtest ways. Hillary’s husband David ends up having an affair, but engages this relationship with none other than Mercy. What Mercy does not know is that Hillary’s husband and Margaret’s husband work in similar business circles, which sets the stage for encounter in which all three characters will finally meet in the same physical space at Margaret’s husband’s fiftieth birthday party. Even with all the immense privilege that Margaret and Hillary do possess, Lee manages that rare feat of plumbing their psychic interiorities so deeply (through third person narration no less) that we still find them engaging and sympathetic characters, but the real coup is Lee’s portrayal of Mercy Cho: an incredibly flawed woman without a real understanding of American upward mobility and romantic courtship, who understands that she is without cultural capital even as she wields a rarefied educational pedigree. As Mercy creates one drama to the next, you begin to see that much of her circumstances appear not simply because of some character deficiency but the radically different class trajectories that the three main characters engage as the titular expatriates. It is in this sense that Lee’s novel provides its most crucial interventions concerning this particular character, who is in need of the most narrative attention in the end, and which Lee crucially provides as the most essential bridging apparatus to bring the narrative to its appropriate and somewhat uplifting conclusion. As with Lee’s previous effort (the epic war novel The Piano Teacher, and there is a fair amount of piano playing in this recent novel as well), there is a cinematic quality to the writing that makes one expect that this is the kind of work that may be optioned for motion picture adaptation. The question would really be about the issue of casting, as two lead roles would need to be awarded to Asian American actresses. I could see Mercy being played by someone like Jamie Chung or Arden Cho, but Margaret Reade would likely need to be mixed race and in her forties, so that role might be harder to cast, maybe someone like Julia Nickson.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-expatriates-janice-y-k-lee/1121772908

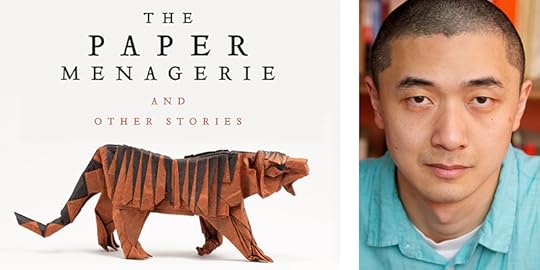

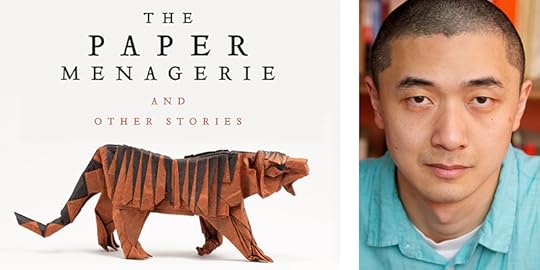

A Review of Ken Liu’s The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories (Saga Press, 2016).

I’ve been reading this phenomenal collection piecemeal. For everyone who has seen this book, you will know why: it’s over 400 pages with numerous stories collected. Nevertheless, I’ll focus mostly on a specific set of the stories. In my first foray, I rocked the first four or so of the stories, and the two that were absolutely fascinating to me were “The Perfect Match” and “Good Hunting.” “The Perfect Match” is a quirky love story in which characters believe their lives are tied to the endurance of a specific object. The protagonist, a young woman working a desultory office job, finds herself realizing that she’s crushing on a coworker. Her object is “ice,” and she lives in fear that an ice cube, which represents her life, will melt, unless she has a freezer always nearby. Even when she goes out to clubs or on social occasions, she needs to bring an ice cube with her and will go out of her way to find a place where it will be cared for in the proper freezing temperature. In her office, she stows the ice in a freezer near her desk. But when her coworker comes into her life, a man who everyone is attracted to, she nevertheless feels that she has a unique connection, one certainly cemented by their mutual love of literature and poetry. She eventually discovers that his object is salt: the very thing that makes it harder to freeze, but we understand that these objects are primarily metaphors. She needs to “warm up” her life, even at the cost of losing her “ice cube.” When the “ice cube” melts down after her moment with the coworker, she thinks she is going to die. The story then cuts to a letter penned by a close friend who tells her that she thought she, too, would die when her object ran out, which was in her case, a pack of cigarettes. When the pack ran out, she realized: she still had the box, and that she was not yet dead, and that she used the cigarettes as a false resource for living her life, that somehow these cigarettes would make her live her life to the fullest, when she could be doing that whenever she wanted. This letter is of course something that the protagonist now knows, too: that she must live, even if it means the possibility of being on the edge, losing something comfortable, living a life in security. Better to be devastated by life and love than to live in the hovel of a home without anyone else around you. When I read “Good Hunting,” (the fourth story or so), I knew I was in trouble: could any of the stories following this one be as good? LOL. In “Good Hunting,” which immediately made me think of Good Will Hunting (but I digress), our protagonists are respectively a demon hunter and a fox demon. They meet each other as youngsters, but the demon hunter and fox demon both discover that they are not really at odds with each other. The fox demon isn’t a being that needs to be vanquished and the demon hunter isn’t someone who is so intent on predation and killing. Instead, they strike up a unique friendship, but one that is coming under duress due to increasing modernization: railroads are being developed, automata are taking on the jobs of human workers, and people believe in magic and mischief a little bit less. The demon hunter doesn’t have demons to hunt anymore; the demons seem to be disappearing, but we discover that they may not be disappearing so much as they are being transformed. The fox demon, as we discover, is having a more and more difficult time turning into her true form as fox. Eventually, she is completely unable to change into her fox form; this fate is of course twinned by the fact that the fictional world is becoming ever more advanced in its technology and efficiency. But the fox demon’s human form does put her at some risk: she is particularly attractive and thus a target for men who might be up to no good. The conclusion sees the demon hunter take a new job, developing automata and technology for a corporation. The fox-demon, on the other hand, is severely assaulted by a man who subjects her to an incredibly twisted mode of body modification, as her appendages are changed into chrome machinery parts. Liu’s critique here is reminiscent of J.G. Ballard’s Crash, especially in the ways that humans become functionalized to the extent that we cannot distinguish where the human ends and the machine begins, so much so the hybridity of human and machine exists as the fulcrum of a dangerous sexual fetish. But, Liu has one more wonderful plot trick up his sleeve: the demon hunter uses his power of technological innovation to provide the fox demon with the ability to transform back into the fox form, but this time with the help of his technological know-how. The end sees her go off into the distance in this fox/ chrome hybrid form. “The Literomancer” follows the travail of a young girl named Lily, who must travel to Taiwan with her family (in the post KMT takeover period). Her father has a new job position out that way; Lily does not want to be there and suffers from bullying in school, but she establishes a friendship with an older man and his adoptive son. The older man possesses a talent based upon reading the fortunes through an analysis of Chinese calligraphy. Lily begins to see how this talent might also be used in terms of her understanding of English, but the story takes a very dark turn when Lily’s explanation of her friendship with this diviner is discovered by her father. Here, we again see the historical past effect considerable influence on a domestic plot. The “Simulacrum” reminded me of a number of different A.I. type stories. In this case, a man develops a kind of software that allows a person to re-experience particular events (reminiscent of that virtual reality moment in Minority Report when Tom Cruise’s character longs to remember his long departed son), but this software of course can be used in a variety of ways. When the daughter of the developer discovers him employing the technology as a way to access previous sexcapades (even though it is a source of marital tension), the daughter loses all faith in her father’s sense of morality. The story ends with the daughter’s mother dying but imploring her to give her father a chance: that her father’s actions in that one particular moment of using the simulacrum cannot be how she thinks of him forever. This story is one ultimately about forgiveness and the belief that people can change. After my concern about the status of other stories after reading “Good Hunting,” my fears especially abated after reading “The Regular,” which is an intriguing detective type plot involving an investigator and a serial killer. “The Regular” refers to the serial killer, who has been picking his targets based upon high-end escorts who have technology implanted in their eyes (here we have shades of Blade Runner for sure) that allows them to record any of their sexual encounters with customers. It’s a safety measure that sex workers can use so that customers know that their actions can be turned against them in case an encounter goes wrong. But, the titular regular and serial killer realizes he can use this technology as a mode by which to effect forms of political change, as he can blackmail high ranking officials and diplomats based upon what he finds in the ocular recording implants. Thus, he targets these escorts precisely because of the value of the information that might hold. The investigator is charged to find out about the death of a Chinese American call girl, one who reminds the investigator of her daughter Ruth who was killed at a moment in time when the investigator chose not to follow the instincts of a device called the Regulator, which provides all users with enhanced powers of perception. The Regulator is an intriguing form of technology that renders the user a kind of cyborg, and the investigator exploits its powers (even at her biological detriment) in her search for the killer. Though I didn’t necessarily think Liu needed to psychologize the investigator as someone compelled in this search because of its connection to her own daughter, the story was particularly enthralling. Another highlight. In the back half of the collection, the stories I enjoyed the most were “The Paper Menagerie,” “The Waves,” “A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel,” and “The Man who Ended History: A Documentary.” I can understand why “The Paper Menagerie” was selected as the title story (and it won numerous awards): it follows a mixed-race child’s disintegrating relationship to his mother. The story begins with him having a very strong and loving relationship with her mother based upon a magical connection to origami: she is able to make origami animals that come to life and play with them. As they get older though, their connection starts to falter under the duress of racial melancholia. The young child begins to realize his mother is “foreign,” and that he, too, is being marked as “different.” He wants his mother to speak to him in English. We’re not surprised that soon the animals stop coming to life. Later, his mother will die from a disease at an early age, leaving behind a letter the son cannot read because, of course, he completely disregarded the need to learn Chinese. “The Waves” was one of my favorite stories, as it explored the evolution of humans to different forms, but how perhaps the cycle of life form changes that humans would undergo would be cyclical. “A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel” reminds me of something that might have been written as a kind of addenda to The Man in the High Castle, as the fictional world is set in a counterfactual timeline in which the Japanese Imperial power continued to rise in its power. The final story in the collection, “The Man who Ended History: A Documentary,” immediately brought to mind a story from Ted Chiang’s Story of your Life and Others (and later, this connection was affirmed as Liu did acknowledge the inspirational relationship) in terms of its form (and even the title). The content, though, was focused on the Nanjing massacre and thus uses Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking as the basis of a time travel storyline in which scientists discover the technology that will allow them to move observe and even to experience key historical events. This technology thus has the capacity to “end history” in the sense that one can be at any time and any place, but Liu seems way more interested in relaying the need to remember in whatever flawed guise that occurs, so that we do not become somehow disaffected to the atrocities occurring now, later, or those well into the past. Indeed, Liu seems well aware of the possibility of memory to be biased, but that such faults in our ability to retain the specifics of a given event do not make them somehow unreliable or untrue. Though I have spent most of my time recounting the stories in terms of their plot, I have to say that I find Liu’s command of the hard SF tropes to be compelling and do hope that he follows his current series with a work that might be set in space or in fictional world filled with robots or aliens. I would give yourself a lot of time to work through these wonderful stories; I definitely plan to adopt this book in future courses with the caveat that I know I’ll have to excerpt it. It will definitely pair quite well with Ted Chiang’s Story of your Life and Others.

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-paper-menagerie-and-other-stories-ken-liu/1121191040

A Review of Shawna Yang Ryan’s Green Island (Knopf, 2016).