Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 43

May 17, 2017

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for May 17, 2016

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) stephenhongsohn

stephenhongsohn

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for May 17, 2016

It’s Asian Pacific American Month! Last year, I attempted a review writing challenge that nearly broke me. But I’m going to try again. I’ve been a little smarter about it this time, because I banked some of the reviews already (but not all). In any case, as per usual, I’m hoping to be matched in my challenge by a total of 31 comments (from unique users) by May 31st. We didn’t quite reach that goal last year, but maybe we can this year. An original post by a user will count as “five comments,” so that’s a quick way to get those numbers up.

Challenge tally: me = 26 reviews; “you” = 6 comments (thanks Kai Cheang for his post and to eeoopark for a comment)… Come on folks! You can do it!

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

So this post focuses on books that are coming out of Penguin and Associated Imprints. I occasionally group these books together because they are all eligible to request under their CFIS program. Information for the CFIS program can be found here:

http://www.penguin.com/services-academic/cfis/

Anybody who teaches are eligible for five free exam copies per year; this service is perhaps the best exam copy service of all major publishers!

In this post, review of all Penguin titles (and Associated Imprints): Sarah Kuhn’s Heroine Complex (Daw Books, 2016); Sabaa Tahir’s A Torch Against the Night (Razorbill, 2016); Krys Lee’s How I Became A North Korean (Viking, 2016); Marina Budhos’s Watched (Wendy Lamb Books, 2016); Michelle Sagara’s Grave (2017); Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West (Riverhead, 2017); Katie Kitamura’s A Separation (Viking, 2017); Marie Lu’s The Midnight Star (G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers).

A Review of Sarah Kuhn’s Heroine Complex (Daw Books, 2016).

Well, I’ve been spending very long days revising critical writing, which is a kind of task that requires so much focus that the only thing I can manage to do after that, is to cozy up to a novel, potentially something more on the lighter side. After one such split infinitive filled day, I chose Sarah Kuhn’s Heroine Complex (Daw Books, 2016), which was precisely the right choice. At first, given the title and the cover, I thought the book was a young adult fiction, but about half way through, an explicit sex scene made it quite clear I was not in that territory. This novel is something more like a paranormal romance, but with a comic tone. Indeed, what sets this book apart from many others is Kuhn’s focus on the wit of its protagonist, Evie Tanaka, a mixed race Japanese American, who must learn to become something other than a sidekick to her best friend and superhero buddy known best by a superhero stage name: Aveda Jupiter. Evie is a firecracker: she drops joke-bombs constantly, referencing (questionable) popular culture like the television series 90210 (the original mind you) and songs like “Eternal Flame” by the Bangles. Evie even has the guts to call a song by The Backstreet Boys a power ballad. Yes, my friends. She’s got guts. Aveda, like Evie, is Asian American. Aveda’s “real name” is Annie Chang, which cracked me up, because I went to school with a girl named Annie Chang, who also happened to be Chinese American. Evie’s originally part of Aveda Jupiter’s superhero posse and entourage, folks who help with things like publicity (a lesbian named Lucy) and technological outreach (a handsome, nerdy, and super analytical guy named Nate and healing spells (Aveda Jupiter’s high school crush, a guy named Scott). Evie also has to find time to take care of her younger teenage sister Bea, especially because their absentee Dad is traipsing all across the world with his yogini Lara. The novel is set in San Francisco, and world building is required because a select number of individuals have developed minor superpowers. Scott, Aveda, and Evie all possess some magical might that has developed from portals that come from the Otherworld, a place that also includes demons. Once this portal opens, others begin to open up, and individuals like Aveda make it a point to become superheroes in order to stop the tide of demons who come through. With comic flair, Kuhn makes it so that these demons can only enter our world through imprinting on the first Earth object that they see. In the opening gambit of the novel, this first object is a cupcake (because we’re in a bakery), and these demons make it so that cupcakes have fangs and are trying to drain the life out of their human victims. When Aveda develops a serious leg injury and a serious zit outbreak, she encourages Evie to take on her persona in order to cover for her until she feels better, but once Evie becomes the substitute, other mayhem occurs. First, Evie’s powers become revealed to the world at large: she’s able to somehow invoke fire starting capabilities, though she does not know how to control her flame creating skills. Second, this new fire power makes Aveda gain lots of new followers on social media, so Aveda realizes that she has to keep Evie in her place until she can devise a plan to that would allow her to also develop fire powers once she gets back on her literal feet. But more trouble begins to brew when Evie notices a strange pattern in the way that the latest demons coming through the portal act: they seem to be more sentient, they seem to be more complex, as if they are evolving into something else. But I’ll leave the plotting here to discuss other things, like the fact that at first, I thought I was going to hate the romance plot element. Nate, the handsome, technological expert with the bod of a beefcake and who becomes Evie’s “orgasms-only” buddy begins to come off as something too good to be true. In other hands, this trope is hardwired into the paranormal romance. Indeed, the fact of the paranormal romance, especially in young adult fictions, is that this nerdy dude with the heart of gold and the body of gold is actually somehow destined for our not-so-ordinary extraordinary heroine, but Kuhn gives us lots of surprises in the concluding arc not only with Nate, but other characters as well. Even Aveda, who I found incredibly annoying, manages to find a measure of redemption because Kuhn knows how to generate some measure of charaterological development, thus moving this novel above and beyond many others in a similar genre and aimed for a similar audience. Only time will tell whether or not there will be a sequel, but signs suggest that there could be one, given the conclusion. Finally, I will say that as a once-upon-a-time reader of the X-Men comics, it is so refreshing to see a novel about superheroes written by an Asian American. It is truly a new era. When I was first reading those comics, you had the strangest storylines occasionally come up: for instance, there was a British mutant with purple hair named Betsy Braddock, who will later randomly get kidnapped, only to return to the X-Men team looking like an Asian ninja. You later find out that her psyche got swapped into another body or something like that and that she wasn’t really Asian in the first place, but the whole storyline was so bizarre: didn’t the other characters realize that just because the person who came back to the team had purple hair didn’t mean she was the same person? Didn’t they realize that she was Asian? LOL. I probably have some plot elements wrong, because it’s been literally two decades since I read that one, but I remember at that time I was so confused. Looking back on it, I wonder about whether or not that storyline might have been different if an Asian American writer was behind the helm. An Asian American artist may have been on staff around that time (Jim Lee), but I can’t remember. Fortunately, we’re in a new era, and comic books are being developed by writers and artists in tandem, many of whom are Asian American. Further still, we’re getting novels like the ones that Kuhn has written here in which we can see that Asian Americans are worthy of their own complicated, complex superhero plots, ready to save the world while defeating demons in the form of cupcakes. Yum.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/heroine-complex-sarah-kuhn/1122789420#productInfoTabs

A Review of Sabaa Tahir’s A Torch Against the Night (Razorbill, 2016).

Sabaa Tahir’s debut, An Ember in the Ashes, was my favorite young adult fiction I read last year purely based upon the entertainment factor. I was convinced that she’d have a difficult time replicating the success she had with that narrative. I’m glad I was definitively wrong. The sequel is just as exciting and plot-driven as the first, and with all the requisite genre necessities that come with the paranormal romance, so fans of this kind of reading will not be disappointed. Our favorites return from the original, especially our primary character: Elias, the melancholic Mask, and Laia, the Scholar who seeks to break her brother out of the maximum security prison known otherwise as Kauf. Elias and Laia are on the run from the Empire, trying to find a way to get to Kauf. They eventually meet up with Keenan, a Scholar working for the Rebellion, and Izzi, who had been working with Laia when Laia was functioning as an undercover “slave” for the Commandant (in the first book). The other major plotline involves Helene, who has become the Blood Shrike and is forced to do the dirty work of the newly crowned emperor and winner of the Trials (from the first book), Marcus. Helene’s quest is to bring back Elias and have him publicly executed. At every turn, her job seems to be made more difficult. Elias’s mother, the evil Commandant, is undermining her authority, while assigning a spy (named Harper) to work as part of her guard detail. Of course, Tahir knows her genre tropes: each character must have their own love triangle. While Elias and Keenan battle for Laia’s affections in one subtle way or another, Helene tries to figure out how she can avoid having to kill Elias, even if it means he gets to be with Laia. Oh, the torment! In any case, this novel is in many ways as bleak as the first one. Hordes of scholars are being butchered, and even the tribespeople, who sort of function as middlemen, cannot assume they are safe. Tahir also adds much more texture to the fictional world, as we discover crucial information about one of the primary evil, magical figures known as the Nightbringer and how he is connected to a spiritual plane that is presided over by the mysterious SoulCatcher. So, I definitely had to try to ration myself with this book, forcing myself to put it down every night, but on the third night, I gave up, and just read it to the finish. I especially appreciated how this book seems to function as a stand-alone. That is, there’s enough of a set-up, exposition, climax and resolution for me to feel as though this book wasn’t just a stepping-stone to a climactic final volume. Strangely enough, I always assumed this book would be a trilogy, though there were indications online that this series was supposed to be a Duology. Now, there are rumblings that this series is meant to have at least four books, and I’m not complaining at all, except for the 2018 anticipated release date of the next book. Two years? Ijustcant.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/a-torch-against-the-night-sabaa-tahir/1122653618

A Review of Krys Lee’s How I Became A North Korean (Viking, 2016).

So, Krys Lee moves out of the first publications club with her debut novel How I Became A North Korean (Viking, 2016). Lee is also author of the superbly melancholic collection Drifting House. The “I” of the title is perhaps the most intriguing element of this work, as it details another “form” of the passing narrative. Though we’ve typically reserved “passing” for racial registers, this novel offers a form based upon ethno-linguistic identifications. There are three narrators in this novel, involving alternating first person voices. As B&N tells it: “Yongju is an accomplished student from one of North Korea's most prominent families. Jangmi, on the other hand, has had to fend for herself since childhood, most recently by smuggling goods across the border. Then there is Danny, a Chinese-American teenager whose quirks and precocious intelligence have long made him an outcast in his California high school. These three disparate lives converge when they flee their homes, finding themselves in a small Chinese town just across the river from North Korea. As they fight to survive in a place where danger seems to close in on all sides, in the form of government informants, husbands, thieves, abductors, and even missionaries, they come to form a kind of adoptive family. But will Yongju, Jangmi and Danny find their way to the better lives they risked everything for?” Yongju and Jangmi are both North Koreans who are “forced” into harrowing crossings into China. Danny is actually an ethnic Korean, but part of a family who had lived in the border region of China (they are called “joseon-jok”). He and his father have moved the United States, but Danny’s mother still lives in the Chinese border region. The novel’s narrative threads move together once Danny travels back to China in the wake of what his father thinks is a failed suicide attempt. Once there he discovers that his mother is engaging in an extramarital affair. Confused and traumatized by this knowledge, Danny goes into a kind of hiding, where he meets up with North Korean teens, who are on the run from border patrol and any other entities. They eke out a meager living in the mountains, but for Danny, his becoming “North Korean” allows him a fraternity he never had. Jangmi eventually settles with them for a short time, before she leaves them behind (and stealing most of their important supplies). Jangmi’s storyline is perhaps the most tragic given that she is forced into various kinds of human trafficking. Yongju connects most with Jangmi in this way because his own little sister and mother are likely sent into human trafficking sectors. The concluding arc seems all three reunited under the auspices of a missionary group, but this time together is very strained. They see their time with the missionaries as just another form of imprisonment, and they eventually crack under their sequestration. The crux of this novel is clearly Danny’s presence, as he is the one who eventually is able to secure their release from missionary detention, but his narrative is quite exceptional. Indeed, Danny’s willingness and voluntary “passing” as a North Korean more largely suggests that freedom cannot be won without incredible luck and good fortune. The larger contexts with which the novel dovetails reminds us that there are not going to be entities that will function to secure one’s release under political asylum, which makes the eventual last page of the novel resound with a kind of Hollywood uplift. Fortunately, given all that these characters have gone through, we will want this brief moment of happiness for these characters. This novel would be very interesting to teach alongside something like Suki Kim’s Without You There is No Us, as these cultural productions present two very different sides of North Korean culture and contexts.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/how-i-became-a-north-korean-krys-lee/1123107416

A Review of Marina Budhos’s Watched (Wendy Lamb Books, 2016).

I have enjoyed reading Marina Budhos’s YA fictions in the past, so it was a treat to see that she had published a new work. In Watched, Marina Budhos fictionally depicts the plight of Muslim Americans/ South Asian Americans in the period following 9/11, especially under increased scrutiny by homeland intelligence agencies. Budhos, for those not entirely familiar, is the author of numerous works, including but not limited to The Professor of Light, Ask me No Questions, and Tell Us We’re Home. The official site provides us with this description of the work: “Naeem is far from the ‘model teen.’ Moving fast in his immigrant neighborhood in Queens is the only way he can outrun the eyes of his hardworking Bangladeshi parents and their gossipy neighbors. Even worse, they’re not the only ones watching. Cameras on poles. Mosques infiltrated. Everyone knows: Be careful what you say and who you say it to. Anyone might be a watcher. Naeem thinks he can charm his way through anything, until his mistakes catch up with him and the cops offer a dark deal. Naeem sees a way to be a hero—a protector—like the guys in his brother’s comic books. Yet what is a hero? What is a traitor? And where does Naeem belong? ” The basic premise is that Naeem is a troubled high school kid, who seems to be on the border of developing into a delinquent. His murky friendship with a peer named Ibrahim leads him to getting arrested for shoplifting, but once he is at the police station he is given an option: he can be charged for theft or he can work for the police as a kind of informant, spying upon any Muslim-related activities. Of course, Naeem doesn’t necessarily take that option immediately: he realizes what is being asked of him. He rightly feels as though he is betraying his own religious community by spying on them, placing them under surveillance and encroaching on their religious freedoms. At the same time, he doesn’t want to disappoint his hardworking parents, who run a small shop and are already on the edge of bankruptcy. When he sees a potential financial opportunity in this spy work, he reluctantly takes it on. For Naeem, home life is complicated by the fact that he is only ten years younger than his stepmother, the person who his father remarried after Naeem’s mother died (when Naeem was five). He’s struggling with school and discovers that he won’t be graduating with his high school class; he is forced to take summer school classes in order to catch up. So, when the police officers him offer a deal instead of being charged, being a “watcher” seems to be the best possible option. Budhos’s work is definitely one that could be taught and is part of a wonderful set of cultural productions that explore the complicated subject position of the Muslim American/ South Asian American in the period following 9/11. I would definitely pair this work alongside others, such as Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist and Ayad Akhtar’s Disgraced. Of course, intriguingly, Budhos also joins a rather large set of spy/ surveillance fictions that include Chang-rae Lee’s Native Speaker, Susan Choi’s Person of Interest, and Ha Jin’s A Map of Betrayal. I also very much appreciated that Budhos brings a kind of sophistication to the young adult genre that relies more upon character development than more of the formulaic plot elements such as the requisite teen romance.

Official Site (with purchasing information):

http://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/249905/watched-by-marina-budhos/9780553534184/

A Review of Michelle Sagara’s Grave (2017).

Michelle Sagara’s Grave finally concludes the Queen of the Dead series that began with Touch. I use the word “finally” because Sagara herself has stated that the final installment in this series was one of the most difficult books she ever wrote. She apparently went through many drafts and had thrown away multiple versions of the book. At some point a couple of years ago, I remember seeing listings of Grave on Amazon but there would never be a list date. I didn’t understand why until Sagara herself addressed the issue in her acknowledgments. The first in the series was published in 2012. With YA trilogies, it’s often typical for a series to complete in 3-4 years; there have even been cases where I have seen two from the same series published at opposite ends of the same year. In any case, the rapidity in the publishing cycle is in some sense necessary: readers are forgetful. I belabor my introduction because I was such a reader. When I cracked open Grave, I had practically forgotten all of the events in the series: all I could remember was that there was a main necromancer-figure who was constantly in danger of being killed. Emma, as I was reminded, had such powerful abilities that she rivaled the Queen of the Dead, who had been in a kind of underworld drawing on the energies of those who had passed and not allowing them to cross over into the afterlife. I didn’t remember that book two saw some tragic events. Emma’s best friend Allie is almost killed by a reanimated dead person (Merrick Longland); Allie’s brother is shot and left for dead; and her cadre is on the run, which includes her other friend Amy Snitman and others such as Eric (another reanimated dead person), Chase (a necromancer-hunter), Chase’s mentor Ernest, Emma’s brother Michael, among others. By this time, Emma has bound some dead to her, which include a former necromancer named Margaret. Obviously, this final installment leads us to the cataclysmic encounter between Emma and the Queen of the Dead, who we come to understand was once a kind of necromancer herself. As a child, Reyna, AKA Queen of the Dead, was trained to become a necromancer by her austere mother (later known as the magar); Reyna also has a little sister named Helmi. Reyna’s also in love with a boy named Eric (the same Eric who is helping Emma at the beginning of this novel). Reyna’s family is tortured and killed for being witches, but Reyna does not die and uses her power as a necromancer to exercise revenge and to reanimate all of her dead loved ones. In this process, she closes the door that allows the dead to cross over into the afterlife. She draws upon their power to create an underworld, a dead city, devoted to preserving her love for Eric, while continuing to draw upon the powers of the newly dead. She creates a Citadel built literally on the souls and energies of the dead who are trapped in its walls, its floors, and its supporting structures. So, Emma’s task is set before: destroy this Evil Queen. If there’s a problem with this particular novel, it’s just that there’s not much going on until that final battle. Basically, the scoobie gang all head down to the Citadel and have to wait around until the Evil Queen makes her appearance. In the meantime, Emma has to learn a couple of skills, like how to use necromantic circles that can protect who is situated inside, while also getting the blessing of the Evil Queen’s mother through the bestowal of a lantern that’s meant to draw the attention of the dead. Of course, Sagara’s point is not to keep the Evil Queen so evil; as the novel draws toward this inexorable battle, it becomes apparent that Reyna went into full Evil Queen mode because she wanted a place where she could be eternally connected with Eric and her family, who had been slaughtered. She was willing to enslave anybody who had died in order to preserve her very twisted version of love. The series might not be for everyone (after all, it’s pretty dark when you think about a city made out of the souls of the dead who aren’t able to cross over into the light) but if you’ve been faithful to the first two installments, the third is a must.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/314790/grave-by-michelle-sagara/9780756409074/

A Review of Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West (Riverhead, 2017).

So, Mohsin Hamid’s fourth novel, Exit West (Riverhead, 2017), has been one I’ve been saving for at the right time. I’m always impressed by Hamid’s verve as a fiction writer; none of his novels ever read the same. He always seems to be pushing himself in some way aesthetically and Exit West is no different. We’ll let Publishers Weekly provide us with some viewpoints first: “Hamid’s (The Reluctant Fundamentalist, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia) trim yet poignant fourth novel addresses similar themes as his previous work and presents a unique perspective on the global refugee crisis. In an unidentified country, young Saeed and burqa-wearing Nadia flee their home after Saeed’s mother is killed by a stray bullet and their city turns increasingly dangerous due to worsening violent clashes between the government and guerillas. The couple joins other migrants traveling to safer havens via carefully guarded doors. Through one door, they wind up in a crowded camp on the Greek Island of Mykonos. Through another, they secure a private room in an abandoned London mansion populated mostly by displaced Nigerians. A third door takes them to California’s Marin County. In each location, their relationship is by turns strengthened and tested by their struggle to find food, adequate shelter, and a sense of belonging among emigrant communities. Hamid’s storytelling is stripped down, and the book’s sweeping allegory is timely and resonant. Of particular importance is the contrast between the migrants’ tenuous daily reality and that of the privileged second- or third-generation native population who’d prefer their new alien neighbors to simply disappear.” This review does a great job of giving us the basics of the novel. What’s most interesting is Hamid’s strongest deviation from realist fiction through the metaphorical use of the “doorway.” The “safely guarded doors” clearly relate to the figurative experience of migration. As with Hamid’s last novel, the author seems less interested in specifics than in a fable-istic approach to storytelling. In this case, we’re never sure what country Saeed and Nadia are actually from, possibly some location in South Asia, West Asia or the Middle East. The benefit of this type of storytelling is that it’s obviously far more accessible to a wider audience, but at the same time, we also lose the specificity of context and history, especially concerning Saeed and Nadia’s home country. As an interesting analogue, Hamid does choose to name other locations that exist beyond the doorways, including the aforementioned Mykonos, London, and Marin County. It becomes evident, too, that the historical trajectory of the novel is further into the past than one might think, especially because it seems as though Nadia and Saeed arrive in Marin County before its become gentrified. As with Hamid’s many other novels, romance in this text, especially of the heterosexual variety, is incredibly complicated and pointed. Of the two, Nadia is definitely the more level-headed of the bunch; she is also definitely more jaded and closed off. Saeed is more idealistic, a dreamer that at first effectively balances the relationship through his quick smiles and hope for the future. Amid the exilic migrations, Nadia and Saeed attempt to maintain the purity of the feelings they developed in their home country when they were first courting each other, but over time, their connection seems to erode. Hamid’s characterization perhaps suggests that they were never meant to be together over the long haul, but one can’t help but wonder what chance their relationship ever had with all of these constant movements.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/exit-west-mohsin-hamid/1123912669#productInfoTabs

A Review of Katie Kitamura’s A Separation (Viking, 2017).

I was SUPER DUPER excited about this novel because I am a huge fan of Katie Kitamura’s second novel, Gone to the Forest, which still (at least to my knowledge) has not received any critical attention. I had a really polarized reaction to this work, somewhat like my experience reading both Jung Yun’s Shelter and Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s Harmless Like You. In this specific case, I immediately found the story compelling in its complex characterization of the issues at hand, but also found the characters themselves to be so dreadful that I found them difficult to want to read about. The titular separation is narrated from the perspective of an unnamed narrator, who travels to Greece to find her husband (named Christopher). Presumably, she’s gone there to ask for an official divorce, so that she can take her own relationship to the next level, with a man named Yvan (who once was a friend of her husband’s). Christopher is in Greece because he’s researching a book that will be based upon mourning rituals. The narrator travels to the hotel where Christopher is staying; the flight is set up by Christopher’s own mother Isabella, who has been asking the narrator about what Christopher is up to. Above all, the narrator wishes for discretion, so she tells Isabella nothing about the separation, but travels to Greece at her behest, and finally arrives in Gerolimenas, a coastal village that has seen better days. The hotel is full of intriguing characters, including the receptionist, who seems to have had a romantic dalliance with Christopher, who in turn we discover is sort of a lothario. Christopher is at first nowhere to be found, so the narrator creates a kind of unofficial disguise (and cover) for herself and decides to stay a couple of days until he shows up. She expects he’s just gone to another part of the island while researching for the book. And here, I suppose I should provide a spoiler warning, because the novel hinges around another revelation that requires the narrator to reconsider her relationship not only to her husband but to her live-in lover Yvan. In some ways, once the novel moves into the second half, I began wondering about the allegorical nature of this work. The narrator, we discover, is a translator. She spends much of her perspective often musing about other characters, their motivations, even making up whole narratives concerning their lives that cannot always be substantiated. Her mode of speculation is in some sense a mirroring of the challenges she finds in translation, the leap between what is known and what can be reformulated through language. We begin to understand how little power she has over her husband, the circumstances of his disappearance, and ultimately, the unraveling of their marriage, even as she commands the central narrative space. She’s not what I would consider to be an unreliable narrator, but there’s still something aloof about her, a distance that makes it difficult to empathize with her, even as her observations about her life, about the Greek village and its inhabitants, about her in-laws get ever more pointed and achingly on-target. The novel leaves the readers suspended in the inadequacies of our terminologies related to rupture, especially as they become connected to our social norms and our desire to maintain a specific image of ourselves in relation to others. As the narrator must confront the fact that her separation will never be, in many ways, ever truly finalized, this state of limbo does not always make for the most compelling narrative resolution. We already know that what we know is ever-always partial, and Kitamura’s brilliantly accurate narrative stylings can sometimes echo with too much reverb in this landscape, a fictional world filled with subtly violent mirrors, one nuanced distortion piling atop another.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/a-separation-katie-kitamura/1123839503?ean=9780399576102

A Review of Marie Lu’s The Midnight Star (G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers).

Marie Lu’s The Midnight Star is the conclusion to The Young Elites trilogy, which has been a sort of X-Men meets Italian-ish social contexts. We’ll let the folks over at B&N provide a little bit of context for us: “Adelina Amouteru is done suffering. She’s turned her back on those who have betrayed her and achieved the ultimate revenge: victory. Her reign as the White Wolf has been a triumphant one, but with each conquest her cruelty only grows. The darkness within her has begun to spiral out of control, threatening to destroy all she's gained. When a new danger appears, Adelina’s forced to revisit old wounds, putting not only herself at risk, but every Elite. In order to preserve her empire, Adelina and her Roses must join the Daggers on a perilous quest—though this uneasy alliance may prove to be the real danger.” So, the alliances of the prior book remain: Adelina is primarily working with Magiano, as she takes over new territories and lands. She’s taking a Machiavellian approach to her rule, which is tempered by Magiano’s suggestions that she provide the occasional gesture of kindness. Meanwhile, the elites are dying, and one of the first to show serious signs of sickness is none other than Adelina’s sister Violetta, who by this time, has holed up with Raffaele and the other Daggers. Raffaele surmises that all of the young elites and those who have been marked by the blood fever are evidence that there is a divine impurity ruining the world. In order to prevent the destruction of all that they know, they must journey to the land of the Gods in order to give back their powers, but this quest requires Adelina and the other Daggers to put aside their rivalries and mistrust. They even must align themselves with mortal enemies such as Teren Santoro, while traveling far to gain the support of Maeve Corrigan, the Queen of the Beldain. As Raffaele suggests, they must find enough young elites with a variety of magical orientations in order to gain entry into the Underworld. Without the help of those like Santoro, they will have no chance. Lu’s conclusion is certainly emotionally powerful. I couldn’t help tearing up when the final pages occurred, though I was a bit underwhelmed by a common narrative conceit that I’ve been seeing in many young adult paranormal fictions. I won’t spoil what that is, but suffice it to say that such storylines ultimately tug on the heartstrings in such a way as to feel a little bit manipulative. The other element that seemed a little bit of a letdown was the resurrection of Enzo, which ends up being more of a plot device than anything substantial. Given the kind of romantic triangle Lu so painstakingly plotted in the first two books, this development was certainly anticlimactic. In any case, fans of Lu will be delighted to discover that she already has a new title in development called War Cross, which is tentatively set to be published in 2017 and is apparently about teenage bounty hunters. Color me intrigued.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-midnight-star-marie-lu/1123274331

comments

comments

May 12, 2017

Asian American Literature Fans Megareview for May 13 2017

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) stephenhongsohn

stephenhongsohn

Asian American Literature Fans Megareview for May 13 2017

It’s Asian Pacific American Month! Last year, I attempted a review writing challenge that nearly broke me. But I’m going to try again. I’ve been a little smarter about it this time, because I banked some of the reviews already (but not all). In any case, as per usual, I’m hoping to be matched in my challenge by a total of 31 comments (from unique users) by May 31st. We didn’t quite reach that goal last year, but maybe we can this year. An original post by a user will count as “five comments,” so that’s a quick way to get those numbers up.

Challenge tally: me = 18 reviews; “you” = 6 comments (thanks Kai Cheang for his post and to eeoopark for a comment)

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews of Curtis C. Chen’s Waypoint Kangaroo (St. Martin’s Press, 2016); Wesley Chu’s Time Siege (Tor, 2016); Wesley Chu’s The Rise of Io (Angry Robot, 2016); Yoon Ha Lee’s Ninefox Gambit (Solaris, 2016); Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (Pantheon, 2016); Monstress: Volume 1 by Marjorie Liu (writer) and Sana Takeda (illustrator) (Image Comics, 2016)

A Review of Curtis C. Chen’s Waypoint Kangaroo (St. Martin’s Press, 2016).

So, admittedly, I started this novel about two or three times. I generally do not have difficulty reading first person fiction, so I was a little bit surprised. I think the false starts have to do more with genre rather than the narrative discourse in this case. I have noticed that I’m having trouble reading science fiction lately due to the world building aspects that seem confusing. Because I tend not to read book descriptions before starting them, I only have a baseline understanding of what I might be getting into based upon a title and a cover. In this case, the opening melded real world referents and places (such as the Kazakhstani border) with fantastic elements (such as space travel and pocket universes). For my small, single planet bound brain, these hybridities were difficult to process. But I digress. Here’s a description for us from B&N: “Kangaroo isn’t your typical spy. Sure, he has extensive agency training, access to bleeding-edge technology, and a ready supply of clever (to him) quips and retorts. But what sets him apart is ‘the pocket.’ It’s a portal that opens into an empty, seemingly infinite, parallel universe, and Kangaroo is the only person in the world who can use it. But he's pretty sure the agency only keeps him around to exploit his superpower. After he bungles yet another mission, Kangaroo gets sent away on a mandatory ‘vacation:’ an interplanetary cruise to Mars. While he tries to make the most of his exile, two passengers are found dead, and Kangaroo has to risk blowing his cover. It turns out he isn’t the only spy on the ship–and he’s just starting to unravel a massive conspiracy which threatens the entire Solar System. Now, Kangaroo has to stop a disaster which would shatter the delicate peace that’s existed between Earth and Mars ever since the brutal Martian Independence War. A new interplanetary conflict would be devastating for both sides. Millions of lives are at stake.” I’m sort of glad I didn’t read this summary because it has a lot of spoilers. You don’t even get to the cruise ship storyline until about page 40 or so, and even then, a dead body doesn’t appear until about page 75, but once that dead body appears, you know the narrative momentum is going to shift because you’re in it to find out what the hell is going on. I appreciate first person detective fiction because you’re restricted to the lens of the storyteller, who is often is as confused as you are. Everybody could be a possible suspect, and on a cruise ship of thousands, there’s a lot of potential suspects. Complicating matters is the fact that so many aboard seem to be ex-military personnel including the ship’s captain and his main advisor, a tough character known as Jemison. Also, Kangaroo likes to make his life complicated by trying to maintain a romance (with another cruise staff member named Ellie) in the middle of murder on the high interplanetary cruise ship seas. The original murder plot itself is confusing: an old man and his wife are found dead. The prime suspect is their son, a man named David, who might have been on anti-psychotic medication at the time. The problem is that David’s medication was swapped out with another, leading everyone to believe that he may have been framed. Additionally, David’s father, one of the deceased, was found to have a unique technology implanted in his body, one constructed from radioactive material that ended up exposing the entire cruise ship to carcinogens. So, the task for Chen as the writer is set: to resolve this mystery and somehow also make sure that all of the cruise ship individuals most exposed to the radiation receive treatment, despite their relative isolation in space. The novel’s definitely a page turner, and a welcome addition to the ever-growing canon of Asian American speculative fiction. Somewhere early on, it’s clear that Kangaroo is of some sort of ethnic background, but I’m not sure which. He does describe himself as “brown” at some point, but we do know that he has a kind of surrogate father figure, so it’s unclear to me whether or not this background will be developed at a later time, perhaps in a future installment. I could have also missed this information entirely, because, as I admitted earlier in the reading process, I had trouble in the initial sections, and I could have glossed over this information during that bumpier road. A take it or leave it element to this novel is Chen’s characterization: Kangaroo is definitely a comic figure, who likes to drop jokes at every opportunity. He’s also unapologetically heterosexual in a way that can get annoying, if you’re not prepared for that kind of constant objectification. But, that being said, I’m absolutely all aboard any other interplanetary fiasco with Kangaroo at the helm. After all, we have to find out what other things he’ll be able to contain in his nifty little pocket universe, a contraption I wouldn’t mind having myself to stow my ever unfortunately growing library. Must. Go. Digital. But. Ijustcant.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/waypoint-kangaroo-curtis-c-chen/1122537806

A Review of Wesley Chu’s Time Siege (Tor, 2016)

I’m here to review Wesley Chu’s Time Siege. So, I was super duper excited for this sequel to Wesley Chu’s Time Salvager, but because it’s a sequel, I need to say right off the bat that there will be a zillion spoilers. I saved it for a night after a lot of revisions, and I was duly rewarded. For whatever reason, I always have a little bit of trouble getting into Chu’s third person narrative perspectives. He tends to use a shifting third, often without much warning that we’re moving to a different focalizer. One chapter might begin with a character’s viewpoint that hasn’t yet been introduced in the novel, so you’re a little bit confused, but once you remember that Chu writes in this way, you begin to settle in. The other problem with sequels is that you have to sort of remember what happened in the first book: Elise Kim and James, our protagonist rogue ChronMan, are now on the run, hiding out with the Elfreth, a tribe, who have subsisted on a post-apocalyptic Earth. Two corporation-like entities (Valta and ChronoCom) are working in tandem to get rid of them because Elise Kim is now what is considered a “temporal anomaly,” and must be stamped out because the longer she is in existence, the longer she permanently alters existing timelines. Elise Kim was saved in the previous novel by James on one of his time jump missions for ChronoCom. Once he engages in this activity, he is considered expendable. In any case, the problems for Elise, James, and the Elfreth are numerous. They are running out of supplies and resources. Most critical is that James’s sister Sasha seems to be dying of something that looks like consumption. Recall that James’s sister was supposed to be dead, but James saves her as well, since if he’s going to be violating Time Laws, why not violate a couple more in order to do other things like alter the course of his personal history. But after a certain point: because James has jumped so many times on salvaging missions, he cannot jump any more in time due to the possibility that he will die. So James, along with the Mother of Time, Grace Priestly, hatch a plan to recruit another ChronMan and use that ChronMan to kidnap a doctor. This plan is elaborate and filled with many obstacles. While Grace and James flounder on this particular mission, Elise is back on Earth herding the Elfreth to the Mist Isle, once known as Manhattan. The problem is that the Co-op team (uniting the forces of Valta and ChronoCom) are still hunting them, so they are constantly moving, constantly tired, and constantly losing more of their battles. Elise begins to realize that they need to stand their ground somewhere, and no other location seems better than with a tribe called the Flatirons, who inhabit a large, disintegrating skyscraper. Elise fortunately is making alliances, as she leads the Elfreth to a possible and more sustainable future, but the leading entity behind the Co-op team is merciless. This character, Secretariate Kuo, is merciless and probably Chu’s best creation in this novel precisely because Kuo has just enough of a background to make you understand why she is so rigid in her philosophy. She truly believes in neoliberal capitalism as a kind of religious ideology and finds any socialist type community formation to be ill-destined. It’s easy to hate Kuo, and therefore, it’s far easier to root for Elise, making this novel’s good vs. bad paradigm a comfortable prospect. Sure, there are times when you think Elise is just too good to be true. Even James, who begins to succumb to drinking habits we’d thought he’d kicked, seems to think Elise is something above him. There’s a sequence involving Elise saving some young children that cements her hagiographic status, so you might blanch a little bit at this kind of saintly characterological figure, but this world is so particularly dark, you occasionally want to believe Elise could exist. And, more to the point, Chu’s plotting is effective: Elise shouldn’t exist in that time and place anyway because she is a temporal anomaly. In some ways, then, it makes sense that her values are so different: she hasn’t had to live in a time and place in which one is just scraping by to survive. You can’t help but wonder if the solution to some of our problems could only occur if we transported someone hundreds of years from a different era to look at the issues anew and to consider other approaches. But I digress. James, in this novel, is more of a broken man. It’s hard to see the anti-hero from the previous novel have such a retrogressive arc, but Chu is obviously playing the long game. As with any second book in what is likely a trilogy: we end on a maddening cliffhanger. Currently, there is no listing for the third book, so let’s hope that it comes sooner rather than later!

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/time-siege-wesley-chu/1122537737

A Review of Wesley Chu’s The Rise of Io (Angry Robot, 2016).

This book is one of the ones I read over the course of several weeks. Usually, I read a novel in one or two sittings, but because the last month has been one of the busiest of my work life ever, I haven’t been able to read at all. The sad thing is that I try to read about three new works a week, just because I usually just enjoy that as a kind of hobby, but there has been absolutely no time, with grading, some family complications, and traveling all thrown in there. Fortunately, this novel has a lot interesting plot elements, the primary of which is related to the world building aspects of this more hard core sci-work. I didn’t actually realize that The Rise of Io is a spin-off of Chu’s earlier Tao series, which I haven’t read due to the fact that it’s only come out in mass market paperback stock paper. Later, I saw that the series was reissued by Turtleback in hardcover, but this reissue actually retained the mass market paper stock, of the high acidic variety (despite the fact that the cover was indeed in hardback but without the traditional dust cover). In any case, that series outlines the basis of the world-building for The Rise of Io, in which there is an alien war being waged between a species of beings that have crash landed on Earth. These beings, called the Quasing, have split into two factions: the Prophus and the Genjix. The Quasing are a race of beings that are sort of like the Trill (of the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine variety), as they require a host and unify their consciousness with a separate being. The Rise of Io takes on this basic premise and follows the titular Io, a Quasing, who has to shift her consciousness into a new host body, when her current host, Emily, is killed during combat. This new host, Ella Patel, who lives in a sort of glorified slum (called Crate Town) in the remains of what is the country of India—we are sort of in a post-apocalyptic environment—is not exactly down with being unified with a Quasing. She reluctantly starts training, so she can better serve the Prophus, as they fight their battles against the Genjix. Much of the entertainment value comes from the constant bickering between Ella and Io, but Chu has a more complex plotting that also involves a Genjix figure named Shura. Shura’s been sent to India to help plot out the destruction of the Prophus, partly through the development of specific political connections. Shura’s a fantastic antagonist precisely because she’s so brutal, and we know eventually that Shura and Ella/ Io are going to meet at the diegetic level. As Chu moves us toward this inevitable clash, other characters start to emerge as central figures, including the Quasing known as Tao, who was the center of Chu’s original series. Apparently, The Rise of Io is the first in a new trilogy, and I’ll be delighted to see where it goes. Chu does leave a major surprise revelation in the latter arc of the story, one that I should have seen coming, but didn’t, and was ultimately floored by, especially because it created a type of narrative problem that I don’t think I’ve ever seen before. If that tantalizing line doesn’t get you to pick up the work, then not much else will.

Let’s just hope it doesn’t cut into the schedule for Chu’s Time Salvager series, as I am totally dying for the next installment there, as well. To change course a little bit, I’ve been so impressed by the recent sci-fi-ish works that I’ve been reading by Asian American writers and works such as this one are encouraging me to expand my course offerings beyond titles like Stories of Your Life and Others/ How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, which have become some of my more common mainstays.

Buy the Book Here:

http://angryrobotbooks.com/books/the-rise-of-io-by-wesley-chu/

A Review of Yoon Ha Lee’s Ninefox Gambit (Solaris, 2016)

So, first off: I tend to want to write up a short review of everything I read, which always involves a bit of a plot summary (as those who have been following Asianamlitfans have obviously seen). I always let some website give us the basics and then move from there. The B&N summary gives us this description: “To win an impossible war Captain Kel Cheris must awaken an ancient weapon and a despised traitor general. Captain Kel Cheris of the hexarchate is disgraced for using unconventional methods in a battle against heretics. Kel Command gives her the opportunity to redeem herself by retaking the Fortress of Scattered Needles, a star fortress that has recently been captured by heretics. Cheris's career isn't the only thing at stake. If the fortress falls, the hexarchate itself might be next. Cheris's best hope is to ally with the undead tactician Shuos Jedao. The good news is that Jedao has never lost a battle, and he may be the only one who can figure out how to successfully besiege the fortress. The bad news is that Jedao went mad in his first life and massacred two armies, one of them his own. As the siege wears on, Cheris must decide how far she can trust Jedao—because she might be his next victim.” What this plot summary doesn’t do for us is to give us some of the world building rules. Yoon Ha Lee has already done some writing on this fictional world; stories such as “Ghostweight” and “The Battle of Candle Arc” from his earlier collection show us how integral mathematics, geometries, and gaming are to this particular fictional terrain. Also, Kel Cheris’s use of Shuos Jedao as the “secret weapon” involves a kind of ghost anchoring in which his “undead character” is attached to Cheris as a kind of shadow. Thus, much of the narrative would seem as though Cheris is talking to herself. I had some trouble actually getting through the first 25 to 50 pages due to the massive amount of unique world building terms that Lee employs, but once you get dialed into the language and the vocabulary, things start to move along quite well. It becomes clear the further the narrative moves along that Cheris and Jedao don’t know the rules of this particular “game” if we might call warfare and siege a game. Part of the problem is that the hexarchate has given Cheris and Jedao very little information in terms of what is going on with the rebellion within the Fortress of Scattered Needles. Second, Jedao himself may have ulterior motives for his own approach to take back the Fortress. Another key detail relates to the fact that the rebellion is trying to shift the hexarchate’s geometries to a seven-faction system instead of six. They are trying to revive the Liosz faction, which was part of an early heretical rebellion that was suppressed. What readers eventually discover is that the Liosz faction is actually trying to implement a new ruling system based upon democracy rather than the current form, which is based on a rough oligarchy. In any case, I should probably stop here because I’ll be giving away too many spoilers. There is one especially interesting narrative device that occurs in the final hundred pages that makes this a very compelling read for me, especially as someone interested in form and aesthetics. Other than that, I don’t get the opportunity to read many space operas by Asian America writers, so I had a lot of fun reading this work. To be sure, I think it does take time to get into the vocabulary of this particular fictional world, but once you’re in, you have no problem following this rabbit hole all the way down. Fortunately, for fans of Yoon Ha Lee, a sequel is in the works (in a series called The Machineries of Empire) and is slated to appear later this year.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/ninefox-gambit-yoon-ha-lee/1122858496

A Review of Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (Pantheon, 2016).

So, as always, I am excited to review any graphic narrative. Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye definitely surprised me because it didn’t conform to any standard storyline or plot. We’ll let B&N provide us with our requisite plot summary and overview: “Meet Charlie Chan Hock Chye. Now in his early 70s, Chan has been making comics in his native Singapore since 1954, when he was a boy of 16. As he looks back on his career over five decades, we see his stories unfold before us in a dazzling array of art styles and forms, their development mirroring the evolution in the political and social landscape of his homeland and of the comic book medium itself. With The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye Sonny Liew has drawn together a myriad of genres to create a thoroughly ingenious and engaging work, where the line between truth and construct may sometimes be blurred, but where the story told is always enthralling, bringing us on a uniquely moving, funny, and thought-provoking journey through the life of an artist and the history of a nation.” What Liew has done is create a sort of fictionalized auto/biography of the titular Charlie Chan Hock Chye. Through Chye’s career, Liew is able to weave in key events in Singaporean and Malaysian histories, especially showing us how these events compounded and complicated Chye’s development as an artist and as a writer. There is thus a high meta-graphic impulse, as the production of cartoons and comics are understood alongside the construction and creation of an independent, postcolonial nation-state. Most important for Liew, then, is the ways that comics, cartoons, and graphic narratives can present political critiques of particular nation-state policies and discourses. I kept thinking about why Liew would have wanted to create this kind of graphic narrative, instead of another that would, say, simply detail the construction of the Singaporean nation-state without recourse to a meta-artistic point-of-view, but what Liew’s work effectively reminds us is that superheroes, speculative registers and artifacts are often merely different tools that an artist and writer might use for political purposes, especially in cultural contexts in which free speech can be policed or even suppressed. The complexity of Liew’s work make this particular graphic narrative perhaps a little bit more challenging to read, but certainly also marks it as one that I will adopt in future courses. The art, as always (and as shown in Liew’s other work such as Malinky Robot) is first rate, and the story of the friendship between the titular Charlie Chan Hock Chye and Bertrand Wong firmly grounds this cultural production.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-art-of-charlie-chan-hock-chye-sonny-liew/1122088101

A Review of Monstress: Volume 1 by Marjorie Liu (writer) and Sana Takeda (illustrator) (Image Comics, 2016)

So I ended up teaching this comic-based work, which has been compiled into a first volume, for my fall course on Trauma Theory. I’ve been interested in the relative lack of consideration between trauma theory and speculative-type fictions. Part of the obvious issue is that trauma theory is referential. That is, it deals with things that actually do occur to actual human beings. Speculative fiction, as we know, can be strongly disarticulated from our “reality.” In this sense, Monstress by Marjorie Liu (writer) and Sana Takeda (illustrator) (Image Comics, 2016) presents a great test case concerning whether or not trauma theory or psychoanalytic theory can be put together in any productive way. Why use our brains to consider whether or not a fictional world that is based upon a completely different typology of humanoid species would be something we should consider as a site of inquiry for a study of trauma or the unconscious? Monstress is a fictional world based upon five different groupings: humans, arcanics, the ancients, the gods, and the cat-peoples. Over time, the ancients and humans somehow crossbred creating arcanics. Arcanics and humans eventually did not get along, which leads us to the current incendiary situation that opens up the graphic novel. Humans have a suborder, a community of witches, that seems to be part of the ruling class. The ancients also have their own ruling community known as the Dark Court. When the graphic novel opens, our protagonist, an Arcanic named Maika Halfwolf has been collared; she’s basically become some sort of human slave. She’s been brought into the human-populated capital and into a residence housing some witches. What we don’t know is why she allowed herself to be captured, but eventually we discover that these witches have information she desires: she wants to know more about what happened to her mother, who had been on a mission of her own when Maika was just a young child. The opening arc generates more questions than answers: it seems as though Maika has some sort of “god” living inside of her, one that comes out of the portion of her amputated arm. This “god” basically sucks the life force out of other individuals, turning them into husks. The basis of the plot is essentially Maika’s search to figure out what exactly she is, how her mother and others were involved in the development of mystical arts, and how Maika will manage to survive given the fact that she’s killed a number of humans. Maika does develop some key allies, including a very young Arcanic, who seems to be a hybrid mixture of human and fox (named Kippa), and then, a cat-being, who reminds us of the equivocating ways of the feline figure from Alice in Wonderland. Why I find this work compelling enough to teach is the question of racializing metaphors here: the enslavement and oppression of the Arcanics allows us an opportunity to consider what happens when social difference emerges in the context of a speculative fiction. How do we understand trauma, violence, and brutality in these imaginary registers? The figure of Maika is an intriguing one: she seems to function as an anti-hero. As the figure the readers are supposedly most connected with, she nevertheless does some questionable things: for instance, “accidentally” eating another young Arcanic due to the fact that she does not yet understand what being she is harboring inside of her. She also ends up killing a number of guards and other figures in order to carry out her mission: do the ends justify the means in her case, especially given the fact that she seems to advocating more largely for the Arcanics, who have been oppressed as a people? Should we consider this book as an analogy for racial oppression in our world? These are the questions I engaged in my class. I also wanted students to consider the import of the “visual” in this work: how does it function to help or to complicate our understandings of trauma and of the unconscious that might be at work? What is especially interesting this regard is that the “god” who seems to exist inside of Maika sometimes acts as a kind of conscience, however conflicted in its appearance. Does the visual realm allow us into a typology of the “psyche,” so to speak? An intriguing work and one I hope will continue to provoke a deep discussion.

(here is Kippa, the adorbs)

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/monstress-volume-1-marjorie-liu/1123808341

comments

comments

May 3, 2017

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for May 3, 2017

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) stephenhongsohn

stephenhongsohn

Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for May 3, 2017

It’s Asian Pacific American Month! Last year, I attempted a review writing challenge that nearly broke me. But I’m going to try again. I’ve been a little smarter about it this time, because I banked some of the reviews already (but not all). In any case, as per usual, I’m hoping to be matched in my challenge by a total of 31 comments (from unique users) by May 31st. We didn’t quite reach that goal last year, but maybe we can this year. An original post by a user will count as “five comments,” so that’s a quick way to get those numbers up.

Challenge tally: me = 12 reviews; “you” = 5 comments (thanks Kai Cheang for his post)

AALF uses “maximal ideological inclusiveness” to define Asian American literature. Thus, we review any writers working in the English language of Asian descent. We also review titles related to Asian American contexts without regard to authorial descent. We also consider titles in translation pending their relationship to America, broadly defined. Our point is precisely to cast the widest net possible.

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide-ranging and expansive terrain of Asian American and Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

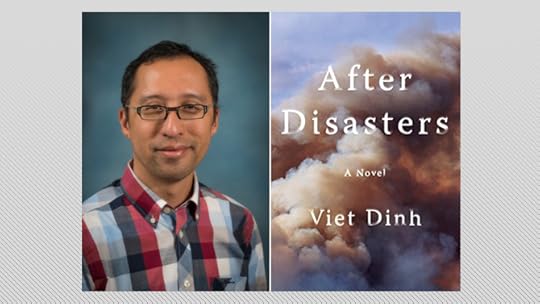

In this post, reviews of Viet Dinh’s After Disasters (Little A, 2016); Tiffany Tsao’s The Oddfits (AmazonCrossing, 2016); Evelyn Skye’s The Crown’s Game (HarperCollins, 2016); Amy Zhang’s This is Where the World Ends (Greenwillow Books, 2016); Kendare Blake’s Three Dark Crowns (HarperTeen, 2016); Linda Sue Park’s Cavern of Secrets (HarperCollins, 2017).

A Review of Viet Dinh’s After Disasters (Little A, 2016).

Viet Dinh’s debut After Disasters is yet another work coming out of Amazon’s publishing sector. Again, I’ve been consistently impressed by the production level qualities and the writing in general. Despite my ambivalent feelings about the company’s tactics overall in terms of publishing monopolies and pricing issues, their publishing imprints might be proving to be beneficial in one way: allowing new releases in book publishing. These days I often like to joke that my discipline is going the way of the dinosaur, so any entity that does put out more books rather than less seems to exist in the plus-side column. But I digress: the review here is for Viet Dinh’s After Disasters (Little A, 2016), which focuses on a set of individuals connected to and dealing with a catastrophic earthquake in India. Here is B&N with a pithy description for us: “Beautifully and hauntingly written, After Disasters is told through the eyes of four people in the wake of a life-shattering earthquake in India. An intricate story of love and loss weaves together the emotional and intimate narratives of Ted, a pharmaceutical salesman turned member of the Disaster Assistance Response Team; his colleague Piotr, who still carries with him the scars of the Bosnia conflict; Andy, a young firefighter eager to prove his worth; and Dev, a doctor on the ground racing against time and dwindling resources. Through time and place, hope and tragedy, love and lust, these four men put their lives at risk in a country where danger lurks everywhere. O. Henry Prize–winning author Viet Dinh takes us on a moving and evocative journey through an India set with smoky funeral pyres, winding rivers that hold prayers and the deceased, and the rubble of Gujarat, a crumbling place wavering between life and death. As the four men fight to impose order on an increasingly chaotic city, where looting and threats of violence become more severe, they realize the first lives they save might be their own.” What’s interesting about this description is that it fails to mention the sexualities of three of main characters: Ted, Dev, and Andy are all queer, at least in some sense of the word and engage in same-sex relationships in one form or another. I add this additional element because the disaster relief narrative, while obviously the central aspect of the novel, is also scaffolded by the fact that Ted and Dev once knew each other in a previous circumstance. Ted was once employed as part of a marketing team for an AIDS/ HIV pharmaceutical company; he meets Dev while at a conference, where they strike up a transitory relationship. Dev is married you see, and, to complicate matters further, when Dev discovers that Ted’s company has made it impossible to sell an AIDS/ HIV drug at a cheap price in India, Dev takes his ire out on Ted, leaving that relationship not surprisingly in shambles. Fast forward about a decade and the earthquake occurs. Ted’s in a new job as part of DART, a disaster assistance relief team, which brings him together with others, including the aforementioned Andy. Once in India, Ted’s world collides again with Dev’s, but the circumstances are of course much different, and they must set aside their past in order to deal with the gruesome, yet crucial work of disease relief and medical assistance. Dinh skillfully juxtaposes broken relationships with a catastrophic event, showing us how one issue is not divorced from the other. Such a comparative approach might have led to a profane mode of narration, but Dinh avoids allowing the romantic tensions to obscure all else precisely because the peril in their work is to confront death in all of its unexpected and graphic forms. One of the most difficult sequences becomes the moment that Andy and part of his firefighting team are forced to leave behind a dog that has been trapped in the rubble because this life is deemed expendable. They cannot put the time and effort in for this particular entity, when they can choose to put their time and energy somewhere else. Such difficult choices are the groundwork of this novel, so when a small mercy appears, however ephemeral we can expect it to be, at the conclusion: you’re relieved that there can be a lifeboat amongst so much rupture. Another novel that I thought I would start reading at 11 a.m. and just stop an hour later. Entirely wrong. Sleep time = 2:40 a.m. You are forewarned.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/after-disasters-viet-dinh/1122771988?ean=9781477849989

(does anyone see the slight irony in the posting link here?)

A Review of Tiffany Tsao’s The Oddfits (AmazonCrossing, 2016).

Tiffany Tsao’s young adult debut novel The Oddfits comes out of its ever-growing original publications sector. The premise is as strange as the title suggests: a young European boy, with blonde hair and blue eyes, is raised in Singapore. He’s not surprisingly marked as an outsider, but for reasons that extend beyond his racial difference. The opening of the novel is made more mysterious, as it focuses on a man who disappears for decades, only to return to Singapore as abruptly as he originally left. This man ends up opening an ice cream shop, which does very well. It is there that he strikes up a friendship with the young boy, who we discover is named Murgatroyd Floyd. With a name like that, you can expect that he is going to suffer further humiliation (and as we discover, his parents indeed intended this nominal ostracization to be the case). On one particular day, the man ends up taking Murgatroyd into the ice cream shop’s freezer, which apparently is magical because it extends far and wide and holds far more ice cream flavors than the man actually sells. But this sense of wonder is shortlived, because the old man will end up dying not too long after this event. Further still, readers are left wondering about why the old man found his young boy to be so important and why the young boy needed to be recruited for something called “the quest.” What is this quest, we wonder? The novel then fast-forwards into the future: Murgatroyd has survived in Singapore, though his life is far from ideal. He is christened with a Chinese-sounding name, Schwet Foo, and works as a waiter at a local restaurant under a tyrannical employer. He has managed to make one best friend. Amid this milieu, another strange visitor emerges named Ann, who, as we discover, comes from the same realm that the ice cream shop owner did. Then, there is this question of “the quest” again, but what is the quest and why is Murgatroyd so perfect for this particular venture? I won’t spoil much more of this plot, because it’s original enough for me to encourage you to read it. Tsao does wonderful work with dynamic world-building here, though sometimes she is a little bit TOO successful at marking Murgatroyd’s social difference. Indeed, it becomes well apparent that there are many people who actively dislike him, so much so that the various ways in which Murgatroyd is made to feel an Other becomes frustrating. Exacerbating matters is the fact that Murgatroyd still feels an incredible sense of responsibility to these various individuals, who seem to make his life more difficult than he is willing to realize. Nevertheless, Tsao eventually gets us to where we need to go, all the while leaving us with a conclusion that sets up a very open-ended sequel to take place. Indeed, by the last pages, we’re still wondering about how Murgatroyd’s quest will actually unfold, though not necessarily disappointed that we don’t have much more information about all the new places he may be exploring. On a different level entirely, Tsao does some intriguing work in terms of Singaporean depictions: there are key moments which are very much invested in the contemporary social contexts of this city/ nation-state, so I continue to see how writers are twining together the political with generic (by which I mean genre). Of the recent spate of Singaporean texts I’ve been engaging in my distance reading group, this one was certainly the most surprising! Definitely looking forward to the sequel, which already has a listing on goodreads.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-oddfits-tiffany-tsao/1122567614

(I disagree with the lone 3 star rating I saw as I linked it).

A Review of Evelyn Skye’s The Crown’s Game (HarperCollins, 2016).

So, I read Evenly Skye’s debut young adult fiction (in the paranormal romance subgenre) right after Tiffany Tsao’s The Oddfits; I completed reading both of these in the same night, so I guess I was in a young adult binge reading mode. We’ll let B&N provide some background for us, as per usual: “Vika Andreyev can summon the snow and turn ash into gold. Nikolai Karimov can see through walls and conjure bridges out of thin air. They are enchanters—the only two in Russia—and with the Ottoman Empire and the Kazakhs threatening, the tsar needs a powerful enchanter by his side. And so he initiates the Crown’s Game, a duel of magical skill. The victor becomes the Imperial Enchanter and the tsar’s most respected adviser. The defeated is sentenced to death. Raised on tiny Ovchinin Island her whole life, Vika is eager for the chance to show off her talent in the grand capital of Saint Petersburg. But can she kill another enchanter—even when his magic calls to her like nothing else ever has? For Nikolai, an orphan, the Crown’s Game is the chance of a lifetime. But his deadly opponent is a force to be reckoned with—beautiful, whip-smart, imaginative—and he can’t stop thinking about her. And when Pasha, Nikolai’s best friend and heir to the throne, also starts to fall for the mysterious enchantress, Nikolai must defeat the girl they both love . . . or be killed himself. As long-buried secrets emerge, threatening the future of the empire, it becomes dangerously clear—the Crown’s Game is not one to lose.” Fortunately, I did NOT read any of these plotting details before I started because it would have put me in a foul mood. As soon as I discovered that there was a game involved, I kept thinking about Katniss Everdeen and things like the quarter quell. Certainly, Skye’s premise is not exactly the same, but a duel to the death involving a paranormal fictional world was a little bit too close for my comfort. Nevertheless, Skye’s fictional world was immersive on the level of her commitment to this premise, and she creates a number of perfect romance triangles, including the central three figures in the editorial description. There were times when I had to roll my eyes because of the inevitable moments in which characters were seen to be fawning in desire over each other, even as they were apparently trying to kill each other, but you sort of have to go with it anytime you’re going to go with the the paranormal romance. The game does have some rules: each enchanter has about five turns to impress the tsar, but complications immediately arise because there’s a side plot involving Nikolai’s mother: she somehow has returned from the dead, and seems to be intent on killing the tsar in order to enact some sort of revenge (the likes of which we’re not sure). What was most compelling to me in terms of this particular fictional world was the research that had to go into it: Skye was evidently a fan of 19th century Russia and used as historical figures as the guides for the main royal family, but deviated with some details (such as the names and genders of particular characters). Additionally, it is clear that Skye is at least attempting to some sort of alternative history, so that the contemporary historical trajectory of Russia has little or not bearing on how we understand the plot. Issues of race (both figuratively and metaphorically speaking) are not entirely evacuated in this fictional world, as both Nikolai and Vika have complicated ancestries. Nikolai is at least part Kazakh, while Vika may be the daughter of a nymph, though we’re unsure. Thus, these markers of social difference are of course important to their class trajectory as well. Both Nikolai and Vika are considered to be commoners, far outside the lineage of the royalty that are the most powerful. Certainly, the success of Skye’s work is reliant upon the chemistry of the two lead characters: we want them to find a way to survive the crown’s game together and perhaps even have their happily ever after. In this way, the novel generates its momentum, and the conclusion sets us up for a wide-open plot, especially because Skye wraps up the most primary plot points in this work, something that I highly appreciated.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-crowns-game-evelyn-skye/1122566658

A Review of Amy Zhang’s This is Where the World Ends (Greenwillow Books, 2016).