Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 39

April 20, 2019

A Review of Julie Kagawa’s Shadow of the Fox (Harlequin Teen, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Julie Kagawa’s Shadow of the Fox (Harlequin Teen, 2018)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Ah, so, Julie Kagawa has graced us with a new series; the first installment is titled Shadow of the Fox (Harlequin Teen, 2018)! I’ve been so busy though that I’ve been writing reviews far past the time I actually finish the books. Generally, this approach is a bad one, as I forget some of the basics, so you’ll have to forgive me for some potential inaccuracies. In any case, here’s B&N with our basic description: “Every millennium, one age ends and another age dawns...and whoever holds the Scroll of a Thousand Prayers holds the power to call the great Kami Dragon from the sea and ask for any one wish. The time is near...and the missing pieces of the scroll will be sought throughout the land of Iwagoto. The holder of the first piece is a humble, unknown peasant girl with a dangerous secret. Demons have burned the temple Yumeko was raised in to the ground, killing everyone within, including the master who trained her to both use and hide her kitsune shapeshifting powers. Yumeko escapes with the temple’s greatest treasure—one part of the ancient scroll. Fate thrusts her into the path of a mysterious samurai, Kage Tatsumi of the Shadow Clan. Yumeko knows he seeks what she has...and is under orders to kill anything and anyone who stands between him and the scroll.”

So, this editorial description does give us the basic set up, but I’ll obviously have to provide some other spoilers, so I’m here giving you your requisite spoiler warning in case you want to turn away. What is left out of this context is that Yumeko is part kitsune, so she is also technically a type of demon, even if she is far from the kind that have burned the temple and killed everyone. Once Yumeko takes the scroll away for safekeeping she naturally links up to a person who also happens to be a demon hunter. Yes, my friends, Kage Tatsumi’s mission is to find the scroll (not realizing that Yumeko is the one carrying it), while also dispatching with any demons in his way. Readers will obviously see the predicament being telegraphed from ten thousand miles away, but nevertheless, the knowledge that we hold propels us forward, as we wait to see how the developing and inexorable romance will end up shaking out.

The other element in the story is that Tatsumi’s wields a sword that in and of itself holds a demon within it, so Tatsumi continually struggles to overcome the influence of that demon, while using that sword’s great power to get rid of anyone in the way of his quest. Once Tatsumi becomes Yumeko’s protector and escort to a temple where the scroll must be taken—and Tatsumi only thinks he’s taking her there, while not understanding that she is in possession of the scroll, and finally believing that he might find answers to where the scroll might be once he gets to that temple—they embark on a longer journey in which they encounter numerous demons and other figures hell bent on destroying them. Along the way, they also manage to pick up some comrades, including a Ronin named Okame, as well as Taiyo Daisuke, a nobleman who wants to duel Tatsumi to the death (but puts aside this battle until the escorting has been completed).

There’s a lot of wonderful action to make this young adult fiction stand out, but Kagawa’s biggest asset, at least from my readerly perspective, is the creative engagement with the many demons that pop up throughout. It is reminiscent in some ways of the other monster-type narratives that I’ve seen that make you wonder about the vast and complicated world of these mythical figures. Alongside the demons, there are many spirits that inhabit numerous objects, places, and things, so the speculative dynamics are quite rich. Kagawa is obviously drawing on Japanese culture, and this novel is perhaps the first of hers that so squarely engages her ethnic heritage. By the time the novel concludes, you can guess that there’s more mischief and mayhem to overcome, so you can expect more “demon-irific” installments.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

March 28, 2019

A Review of Henry Wei Leung’s Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric (Omnidawn Publishing, 2017)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Henry Wei Leung’s Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric (Omnidawn Publishing, 2017)

By Gnei Soraya Zarook

[image error]

I want to preface this review by admitting that I have only engaged with two texts that count as ‘poetry’ before encountering Henry Wei Leung’s Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric: Shailja Patel’s Migritude and Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. Thanks to a seminar two quarters ago on Law and Literature, I am now able to add two more works to that list: Craig Santos Perez’s from Unincorporated Territory and Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas. Of every other bit of poetry I was assigned in American Literature survey courses through my undergraduate career, I unfortunately have no recollection.

My preface here is meant to do two things: (1) ask forgiveness in the mistakes you are likely to find as a result of my ignorance of the formal characteristics of poetry, which is limited to knowing what a stanza is, and (2) bring attention to the fact that the only works of poetry I have read have all been works that are not just poetry in the traditional layperson sense of the word; they are all poetry with an asterisk, prose poetry, poetry/prose, poetry/essay, and so on. But more than that, they are all seem to embody an ethics of protest, and thus they all make me feel things about the people and events that they are about.

Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric is no different, and so this review will focus mostly on how I have felt reading it, because that is the most that I can offer to this extraordinary text. I will let Omnidawn provide a more eloquent summary of what this work is than I am capable of: “Written in and of the protest encampments of one of the most sophisticated Occupy movements in recent history, Goddess of Democracy attempts to understand the disobedience and desperation implicated in a love for freedom. Part lyric, part autoethnography, part historical document, these poems orbit around the manifold erasures of the Umbrella protests in Hong Kong in 2014. Leung, who was in those protests while on a Fulbright grant, navigates the ethics of diasporic dis-identity, of outsiderness and passing, of privilege and the pretension of understanding, in these poems which ask: “what is / freedom when divorced from / from?”

Never quite knowing what to do with poetry on its own, I was hesitant at the first poem, “Preamble: Room for Cadavers,” but I was immediately arrested by the images and the focus on the body, and by the sense of love and care in phrases like the following:

I never thought we came apart like this,

like sheet, like blanket, pillow after pillow

unpeeled by morning, trace of warmth

where once a body swelled. (17)

The first section of the book, titled “Neither Donkey Nor Horse,” meditates on the Goddess of Democracy, the 33-foot paper mache statue built by university students during the 1989 Democracy Movement in Tiananmen Square. The status was destroyed by soldiers during the Tiananmen Massacre in June 1989. As I learned of this history, what is at stake in a work like this became clear, for I had previous knowledge of the Tiananmen Massacre, but none whatsoever of the Goddess of Democracy. And so it becomes fitting the many absences in the poem, the many spaces and redacted phrases, the words thrown across the page in what seems, at first, to be a random scatter. Thus I felt deeply implicated reading the following lines from “Disobedience,” which allowed me to pause and assess my intrusion into a text that asks questions of the failures of democracy and of memory:

I was not meant to survive.

So forgive my participation.

Forgive me my love for freedom

and for my foreign question: what is

freedom when divorced from

from? (20)

The poem’s narrator is a foreigner in the sense that they have lived overseas and have now returned to their country of origin and is part of a protest. Cathy Park Hong writes in the introduction to the book about these last three lines: “Leung doesn’t give us an accessible individualized account to pull at the American reader’s heartstrings but instead uses his first-hand insights to interrogate Western ideologies of democracy: ‘what is freedom when divorced from from?’ I agree; the book consistently remind the reader that it is written for a specific audience, and that the reader may not be that audience. This kind of refusal reminds me of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, a similar collection of prose poetry that archives the experiences of black women and people of color as they experience daily microaggressions. If you know or experience the instances that comprise the text, you resonate with it differently. Leung is speaking to someone in particular, and everyone else can listen in on this conversation.

Another of my favorite pieces was the one titled “BRIDGE IN” on page 29, which I was thrilled to find is a companion piece to “(Abridged Timeline: Hong Kong 2014)” on page 93. The title of the first piece comes from letters and words taken out of the second piece. The first piece is mostly blank, and is missing several events, so that it provides only a shattered, incomplete picture that is hardly a picture at all. Only once the reader has paid attention by reading through to the end are they allowed the complete timeline. And yet, the entire process is one of recognizing that when it comes to things such as timelines, there are no such things as clean ‘start’ and ‘end’ dates, and no such thing as ‘complete.’

As June, 4, 2019 approaches, marking thirty years since the Tiananmen Square Massacre, Leung’s work asks us to meditate on how complicated it is to remember violence, protest, sacrifice, and symbols of resistance, even ones that were taken down. In refusing a full picture and asking to what extent we can ethically recreate the loss, trauma, and victory of protest, one of the things Goddess of Democracy does so well is revel in the knowledge of precisely how much work the placement, absence, and presence of words can demand of us to respond, to question, to remember, and to occupy, long after a tangible protest seems 'over.'

Buy the Book Here!

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

March 26, 2019

Anuradha Bhagwati at UC Riverside: April 15, 2019

December 31, 2018

A Review of Karen Tei Yamashita’s Letters to Memory (Coffee House Press, 2017)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Karen Tei Yamashita’s Letters to Memory (Coffee House Press, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

While I was still living in the Bay Area, I would occasionally have the wonderful luck of hanging out with Karen Tei Yamashita. I had been hearing tidbits of Yamashita’s newest project and had been excited to hear about its progress, and here we are! In any case, what a treat to be reading this particular work, which is Yamashita’s most recent foray in creative nonfiction.

The official page over at the ever-groovy Coffee House Press gives us this pithy overview: “Letters to Memory is an excursion through the Japanese internment using archival materials from the Yamashita family as well as a series of epistolary conversations with composite characters representing a range of academic specialties. Historians, anthropologists, classicists—their disciplines, and Yamashita’s engagement with them, are a way for her to explore various aspects of the internment and to expand its meaning beyond her family, and our borders, to ideas of debt, forgiveness, civil rights, orientalism, and community.”

It’s been awhile since she’s really engaged in this kind of writing, and I’ve forgotten how playful Yamashita can be when blurring the lines between what is imagined and what actually happened. What Yamashita works with is the problem of the archive: things are always missing, because a basement will get flooded destroying valuable documents, letters will be lost, memories get fuzzy, and official files will get redacted. Yamashita is well aware of this predicament and constantly employs conditionals throughout Letters, saying things like, “it could have” or “might be” or “would have been” in order to offer possible motivations, possible outcomes and possible consequences. At the same time, Yamashita has some obvious firm grounding under her, employing anchor points and events in her family’s history and how that history intertwines with larger national and transnational forces occurring throughout the 20th century.

Notably, Yamashita’s Letters adds to the sansei internment corpus, elaborating upon the ways her family became impacted by that event. One of the more intriguing particularities of this addition is its exploration of religious and spiritual discourses that kept the Yamashita family together. Out of this strain of representational inquiry, Yamashita paints a rich picture of her father, who pursues his spiritual projects with a fervor that certainly inspires and illuminates. The production level of Letters is wonderful, with appropriately placed visuals, documents, and photographs appearing throughout. But what always stamps the narrative stylings of a Yamashita publication is that witty narrative discourse, one that reminds us that we’re moving through a whimsical landscape full of texture and nuance. An absolutely effulgent journey into the always contested past of the (extended) family.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Sunjeeva Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways (Knopf, 2016)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Sunjeeva Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways (Knopf, 2016).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Short-listed for the Man Booker Prize, Sunjeeva Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways is his first stateside publication, though he is also author of Ours are the Streets, which I promptly looked for as a used copy in the hopes that I can get a copy of this work. The Year of the Runaways is a perfectly apt title for a book that focuses on four South Asians who come to England, all under very different circumstances, but all in ways that suggest they are “runaways.”

To discuss their trajectories, one necessarily has to spoil some of the information, but before we get to this work, let us allow B&N to do give us all some editorial context: “Three young men, and one unforgettable woman, come together in a journey from India to England, where they hope to begin something new—to support their families; to build their futures; to show their worth; to escape the past. They have almost no idea what awaits them. In a dilapidated shared house in Sheffield, Tarlochan, a former rickshaw driver, will say nothing about his life in Bihar. Avtar and Randeep are middle-class boys whose families are slowly sinking into financial ruin, bound together by Avtar’s secret. Randeep, in turn, has a visa wife across town, whose cupboards are full of her husband’s clothes in case the immigration agents surprise her with a visit. She is Narinder, and her story is the most surprising of them all. The Year of the Runaways unfolds over the course of one shattering year in which the destinies of these four characters become irreversibly entwined, a year in which they are forced to rely on one another in ways they never could have foreseen, and in which their hopes of breaking free of the past are decimated by the punishing realities of immigrant life. A novel of extraordinary ambition and authority, about what it means and what it costs to make a new life—about the capaciousness of the human spirit, and the resurrection of tenderness and humanity in the face of unspeakable suffering.”

Shattering is a pretty good description for that year; all characters are pretty tragic in their own ways, and I found parts of this novel fairly depressing. There’s quite a bit of cultural knowledge that one may unfortunately lack before reading this work. I found myself struggling with certain terminologies. For instance, I didn’t know that the term chamar was used to describe the caste that has been more familiarly known as the “untouchables.” During one of India’s many religious riots, Tarlochan and his family are brutally and horrifically targeted. Tarlochan, aka Tochi, leaves for India in the wake of this tragedy. For his part, Avtar wants to be able to provide for his family, while also properly courting a wife. His romantic object is none other than the sister of Randeep, who himself is struggling because his father is suffering from a mental illness that has destabilized their financial situation. For Avtar to get the funds to travel to England, he sells his kidney on the black market, while Randeep is able to negotiate his way to England via a sham VISA marriage.

Narinder’s story concerns guilt that stems from the death that might have been avoided had she agreed to help a friend. The novel ultimately hinges on Narinder’s presence: she is the glue that ends up bringing all four characters, however disparate in their interests, together. Her depiction is in part what really lifts Sahota’s story to a different register, but it is Narinder’s philosophical and spiritual beliefs that are put to the test in the course of this difficult, but luminous novel. While some of the narrative threads no doubt dovetail with common immigrant tropes, Sahota’s depictions and sure-footed focus on the existential and material reasons behind transnational movements make this novel rise above so many similar ones. Readers are motivated to consider Narinder’s motives as both naïve, yet touching, and Sahota’s epilogue, though rushed, serves to show us that her purpose and quest, however flawed, somehow still manages to succeed. Sahota thus provides a measure of closure without settling it in a maudlin, unrealistic way. Characters survive and perhaps even succeed, but often at great cost.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

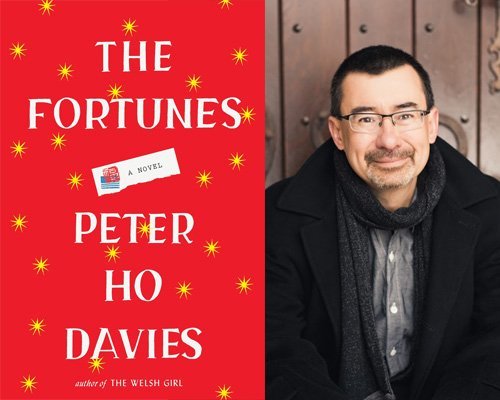

A Review of Peter Ho Davies’s The Fortunes (Houghton Mifflin, 2016)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Peter Ho Davies’s The Fortunes (Houghton Mifflin, 2016).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

This publication was one of my biggest anticipated reads for 2016, as Peter Ho Davies’s third work, The Welsh Girl, was one of my faves. Davies is also author of two wonderful short story collections (The Ugliest House in the World and Equal Love). Here is a short summary from B&N: “Sly, funny, intelligent, and artfully structured, The Fortunes recasts American history through the lives of Chinese Americans and reimagines the multigenerational novel through the fractures of immigrant family experience. Inhabiting four lives—a railroad baron’s valet who unwittingly ignites an explosion in Chinese labor; Hollywood’s first Chinese movie star; a hate-crime victim whose death mobilizes the Asian American community; and a biracial writer visiting China for an adoption—this novel captures and capsizes over a century of our history, showing that even as family bonds are denied and broken, a community can survive—as much through love as blood. Building fact into fiction, spinning fiction around fact, Davies uses each of these stories—three inspired by real historical characters—to examine the process of becoming not only Chinese American, but American.”

As I relayed my reading experience to my sisters, they both told me that I was probably the one person that this publication was NOT written for, precisely because Davies uses Asian American figures for the basis of four different narrative sections, which makes up this polyvocal work. The first section is devoted to a Chinese railroad laborer, the second to Anna May Wong, the third to a friend of Vincent Chin, and finally, the last based upon the writer—Asian American, biracial, father to an adoptee, or otherwise—himself.

Though modeled on “real” people, this work is largely a philosophical meditation on what it means to be Asian American at different points in history and how these moments are telescoped through varying challenges related to success and upward mobility. As a trained Asian Americanist in literature and culture, this novel treads a lot of similar ground concerning what I teach in the classroom, so there was a kind of ennui I did feel, which is why my sisters pointed out that I probably was the most “un” ideal reader for this work. At the same time, I completely understand the value of Davies’s approach, especially when the author treads meta-representational ground in the fourth section: what is the burden of identity when it comes to telling stories? In this sense, we can say that Davies has made his intervention with respect to what it means to be an Asian American writer, which is perhaps more complicated for the author who can also be defined as the mixed race writer.

It’s not an accident, too, that this publication comes on the heels of The Welsh Girl, which explored vastly different cultural, ethnic, and racial contexts, and was a novel that I considered when writing my first book. Not surprisingly, I don’t see much (or any) criticism on The Welsh Girl from Asian Americanist critics, though its exploration of labor, class, and ethnic difference certainly dovetail with thematic preoccupations of the field. What makes a writer legible, what makes his work a success, how does one achieve “fortune” as an Asian American more broadly and as an artist?

If there is a section that I unequivocally recommend, it is definitely the first of the four. It is there that Davies gets a chance to showcase his regionalist eye, one that I saw on full display in The Welsh Girl, and reveals a writer attuned to epic descriptions of the landscape. You get a sense of the awe and the immensity of the “frontier,” as the protagonist from that section travels by train to a labor camp. This opening section is perhaps also the most deliberately plotted in a more realist sense and the reportage that follows in the Anna May Wong portion feels much less hefty. To a certain degree, this change in approach is necessitated by Davies’s point: Wong’s life and career are always a little bit skewed by media and by the publicity machine. The writer himself is of course inculcated in this distortion, which is certainly a reason for relaying a punctuated and fragmented narrative in this second arc.

The section from the perspective of Vincent Chin’s friend was also a welcome shift in terms of viewpoint that allowed Davies a chance to reconsider this traumatic moment. The final section I appreciated simply for the ways that Davies could play with his own background in the construction of a character. As the work moves back to China, The Fortunes comes full circle, establishing a fitting close to an ambitious, if admittedly uneven, fourth publication.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Jenny Han’s Always and Forever, Lara Jean (Simon and Schuster for Young Readers, 2017)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Jenny Han’s Always and Forever, Lara Jean (Simon and Schuster for Young Readers, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I’m reviewing Jenny Han’s Always and Forever, Lara Jean (Simon and Schuster for Young Readers, 2017), which is the final installment from the series that began with To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and continued with P.S. I Still Love You.

B&N provides us, as always, with a pithy description: “Lara Jean’s letter-writing days aren’t over in this surprise follow-up to the New York Times bestselling To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and P.S. I Still Love You. Lara Jean is having the best senior year a girl could ever hope for. She is head over heels in love with her boyfriend, Peter; her dad’s finally getting remarried to their next door neighbor, Ms. Rothschild; and Margot’s coming home for the summer just in time for the wedding. But change is looming on the horizon. And while Lara Jean is having fun and keeping busy helping plan her father’s wedding, she can’t ignore the big life decisions she has to make. Most pressingly, where she wants to go to college and what that means for her relationship with Peter. She watched her sister Margot go through these growing pains. Now Lara Jean's the one who'll be graduating high school and leaving for college and leaving her family—and possibly the boy she loves—behind. When your heart and your head are saying two different things, which one should you listen to?”

A simultaneous strength and weakness of this particular work is that it diverges from the formula of previous installments: Lara Jean isn’t fighting to figure out which guy is the right one for her. Romantic tension and the triangle are effectively absent in this particular work. Instead, romantic issues derive out of whether or not Lara Jean and Peter are going to stay together because of their divergent college decisions. Peter gets into University of Virginia on an athletic scholarship for lacrosse. Lara Jean does not get in, effectively eliminating their plans to continue dating, while they are enrolled at the same school.

Fortunately, Lara Jean gets into the College of William & Mary. Though it’s not exactly next door, the distance is prohibitively far, and things get messy once Lara Jean gets accepted into University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill (off the waitlist). Ranked higher than the College of William & Mary, an impromptu trip to the university (with her bestie Chris) convinces her that the school is the right choice for her. At the same time, this college choice would move her further away from Peter, leading to yet more problems between them. The other major plotline is given to Lara Jean’s father, who has fallen in love with the neighbor across the street, Ms. Rothschild (aka Trina). They’re getting married, which is perfectly wonderful according to Lara Jean’s perspective (and her little sister Kitty’s), but their older sister (Margot), who is still across the Atlantic in Europe and now dating a new guy, isn’t so taken with Ms. Rothschild. So, there’s another issue about family unity in the face of a considerable change.

The problem of this work is that the issues do not always generate enough narrative momentum. Yes, Lara Jean might worry about how to perfect a cookie recipe or whether or not she’s going to lose her virginity with Peter at Beachweek, but nothing ever seems really in peril or at stake. Even the general spats between Peter and Lara Jean continually resolve through texting, as one character or another is quick to apologize and declare undying love the very next day. There is an interesting moment when Lara Jean, referring to something that Peter says, realizes that Peter’s unflagging devotion is only something that a teenage boy could say: it made me wonder, just for a sliver of a second, whether this book seemed to be a retrospective.

Indeed, that moment made me think that the gravity of this work might have been heftier had it been told in this fashion, with a slightly older and warier Lara Jean, looking wistfully back at a past that had gone into myth, because that's what this novel reads mostly like: a period of almost-perfect potentiality when all seems possible; nothing seems out of reach. Without the realistic tinge that this more reflective retrospective voice provides us, the novel, even with its occasional dilemmas, seems just a little too crystalline: we’re waiting for that anvil to drop. Given Lara Jean’s bubbly perspective, I have no doubts that whatever mess that she might have found herself in had this novel gone the distance, she would have clawed her way out, baking her way to a fresh, perhaps more nuanced perspective about life, love, and post-teenage devotion.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Jennifer Kwon Dobbs’s Interrogation Room (White Pine Press, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Jennifer Kwon Dobbs’s Interrogation Room (White Pine Press, 2018).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Rejoice! Jennifer Kwon Dobbs has brought us another elegantly crafted and exquisitely arresting poetry collection: Interrogation Room (White Pine Press, 2018). A master at something I can best describe as an avant-garde, interlingual, confessional poetics, Kwon Dobbs traverses a wide geographical and historical swathe in this collection that shuttles us primarily between the tense relationship between the United States and Korea (both North and South, prior to and after the main years of the Korean Conflict).

We’ll let B&N give us some more background: “In Interrogation Room, Jennifer Kwon Dobbs’s second collection, poems that restore redacted speech and traverse forbidden borders suture together divided bodies, geographies, and kinships to confront the unending Korean War’s legacies of forced distances and militarized silences. Kwon Dobbs powerfully entwines uneasy, tentative reconciliations among South Korea’s relatives in the North, her birth family in the South, and the transnational diaspora to which she belongs to resist the war’s deprivations of language and imagination.”

I appreciated the phrase “restore redacted speech” precisely because so many of these poems riff off of existing cultural productions. There’s a poetic palimpsestic process at work, with Kwon Dobbs able to revise and transform existing discourses of militarization, trauma, and subjection. One of the best and most poignant examples is “Reading Keith Wilson’s ‘The Girl,”” which reuses snippets from the lines of the aforementioned Wilson poem in order to give a more prominent context and voice to the titular Korean girl. As Kwon Dobbs opens the poem, the lyric speaker tells us: “I’ve thought about tone/ how white space stages” (53) what will come to be understood as a violent period of time, “Korea 1953” (31). Immediately, the time and place remind us that we’re at war, so that the girl’s objectification is made evident as something produced out of tremendous duress.

But Kwon Dobbs is suspicious of this lyrical sympathy as it is one that not simply brings this girl into representational being, but also silences her. A moment in Wilson’s original Korean War poem relates how the girl writes some Korean words, which are not understood. For Kwon Dobbs, this moment exists as a violent mode of erasure, something the lyric speaker denotes as a process in which “he scratched out/ the foreign words/ coaxed from the men’s creased hems” (32). The lyric speaker’s final utterance: “It had to be a girl” is an invocation of the ways in which representation elides the material violence faced by females during wartime. Sympathy only does so much, the lyric speaker reminds us, so the “tone” must take us elsewhere, to a sense of anger and to this revision which casts a dark gaze over the military personnel who partake of the imperiled lives of women in war zones.

Another excellent example of the riffing process that Kwon Dobbs engages in occurs in “A Forest in Jeju, South Korea,” which is a poem written for Jane Jin Kaisen. Kaisen ends up directing a documentary based upon the 1948 Cheju (Jeju) island massacre; this film is the inspiration for Kwon Dobbs’s lyrics, which transform the jeopardy of islanders into textual form: “He hides under brown/ improvised/ from neighbors’ corpses,/ conceals/ his baby sister inside/ a cow’s gutted stomach” (20). The grotesque imagery here focuses on the layers of subterfuge at work in this moment. While this figure is forced into hiding for his very survival, that moment is of course also further encrypted by US military forces and their accounts of the massacre itself.

Thus, Kwon Dobbs’s lyrics are always exposing us to a wider, more textured understanding of the violent encounters produced by war. The urgency in these lyrics is always made ever more palpable by the clipped quality of Kwon Dobbs’s lines: never maudlin or overwrought, Kwon Dobbs keys us squarely into the quietly miraculous nature by which so many have managed to endure under the catastrophic designs of empire.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Rahul Mehta’s No Other World (Harper, 2017)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Rahul Mehta’s No Other World (Harper, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

This novel was definitely one of the most anticipated releases of 2017; Rahul Mehta’s first publication, a collection called Quarantine, is one that I’ve taught a number of times in my classes. Mehta’s debut novel No Other World is an impressive work, one that spans cultures and continents, while also conveying the complicated lives of South Asian migrants.

Let’s have B&N provide a summary: “From the author of the prize-winning collection Quarantine, an insightful, compelling debut novel set in rural America and India in the 1980s and ’90s, part coming-of-age story about a gay Indian American boy, part family saga about an immigrant family’s struggles to find a sense of belonging, identity, and hope. In a rural community in Western New York, twelve-year-old Kiran Shah, the American-born son of Indian immigrants, longingly observes his prototypically American neighbors, the Bells. He attends school with Kelly Bell, but he’s powerfully drawn—in a way he does not yet understand—to her charismatic father, Chris. Kiran’s yearnings echo his parents’ bewilderment as they try to adjust to a new world. His father, Nishit Shah, a successful doctor, is haunted by thoughts of the brother he left behind. His mother, Shanti, struggles to accept a life with a man she did not choose—her marriage to Nishit was arranged—and her growing attachment to an American man. Kiran is close to his older sister, Preeti—until an unexpected threat and an unfathomable betrayal drive a wedge between them that will reverberate through their lives. As he leaves childhood behind, Kiran finds himself perpetually on the outside—as an Indian American torn between two cultures and as a gay man in a homophobic society. In the wake of an emotional breakdown, he travels to India, where he forms an intense bond with a teenage hijra, a member of India’s ancient transgender community. With her help, Kiran begins to pull together the pieces of his broken past. Sweeping and emotionally complex, No Other World is a haunting meditation on love, belonging, and forgiveness that explores the line between our responsibilities to our families and to ourselves, the difficult choices we make, and the painful cost of claiming our true selves.”

Mehta chooses a shifting third person point-of-view, primarily following the married couple, Nishit and Shanti, and their two children, Kiran and Preeti. The opening of the novel sees Kiran obsessively watching his neighbor’s house. As we discover, Kiran is desperately seeking a glimpse of the father living in that house, an All-American type upstate New Yorker named Chris Bell. Mehta patiently unfurls the complicated narrative, revealing that Kiran’s desire to see Chris Bell is wrapped up in the complicated dynamics of his mother’s never-quite-consummated love affair with Chris Bell as well as his own growing pains. The first third of the novel tracks this particular South Asian family as it adjusts as well as it can to small town dynamics.

The second shifts perspectives slightly to Kiran’s cousin Bharat, who comes to the United States due to a prophetic warning offered by a seer. This particular section tracks Bharat’s disenchantment with the United States, especially as he develops a severe allergic reaction that seems to mirror his feelings for this alien landscape. For his part, Kiran does little to help Bharat acclimate and instead becomes mired in his own dilemmas.

The third section of the novel shifts to India. It is at this point that readers discover Kiran is queer and that he is suffering from a serious depression. His parents’ unconditional love drives them to encourage Kiran to travel to India, where he can further explore his roots. Kiran’s parents believe that such a trip will allow him to gain greater perspective on his family and perhaps offer him a mental salve that will help enable him to battle his depression. Mehta’s novel is most successful in its ability to weave in so many disparate points-of-view. The kaleidoscopic perspectives generated provide a multifaceted rendering of the South Asian immigrant experience. Perhaps, most importantly, the novel serves to show us a queer Asian American character, who is able to navigate his struggles and achieve a sense of equanimity by the novel’s conclusion.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

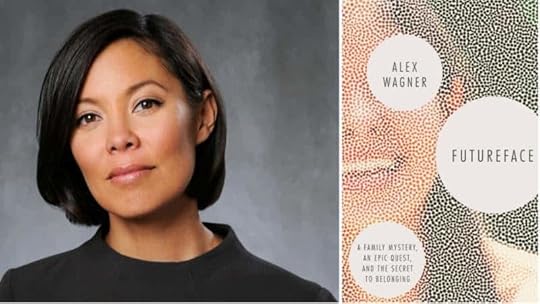

A Review of Alex Wagner’s Futureface: A Family Mystery, an Epic Quest, and the Secret to Belonging

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Alex Wagner’s Futureface: A Family Mystery, an Epic Quest, and the Secret to Belonging (OneWorld, 2018).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Lately, the only thing I ever turn on in my car is NPR. The radio station once held an interview with Alex Wagner, who was discussing her mixed genre publication Future Face: A Family Mystery, an Epic Quest, and the Secret to Belonging (OneWorld, 2018).

B&N gives us this description of the title: “Alex Wagner has always been fascinated by stories of exile and migration. Her father’s ancestors immigrated to the United States from Ireland and Luxembourg. Her mother fled Rangoon in the 1960s, escaping Burma’s military dictatorship. In her professional life, Wagner reported from the Arizona-Mexico border, where agents, drones, cameras, and military hardware guarded the line between two nations. She listened to debates about whether the United States should be a melting pot or a salad bowl. She knew that moving from one land to another—and the accompanying recombination of individual and tribal identities—was the story of America. And she was happy that her own mixed-race ancestry and late twentieth-century education had taught her that identity is mutable and meaningless, a thing we make rather than a thing we are. When a cousin’s offhand comment threw a mystery into her personal story–introducing the possibility of an exciting new twist in her already complex family history—Wagner was suddenly awakened to her own deep hunger to be something, to belong, to have an identity that mattered, a tribe of her own. Intoxicated by the possibility, she became determined to investigate her genealogy. So she set off on a quest to find the truth about her family history. The journey takes Wagner from Burma to Luxembourg, from ruined colonial capitals with records written on banana leaves to Mormon databases and high-tech genetic labs. As she gets closer to solving the mystery of her own ancestry, she begins to grapple with a deeper question: Does it matter? Is our enduring obsession with blood and land, race and identity, worth all the trouble it’s caused us? The answers can be found in this deeply personal account of her search for belonging, a meditation on the things that define us as insiders and outsiders and make us think in terms of “us” and “them.” In this time of conflict over who we are as a country, when so much emphasis is placed on ethnic, religious, and national divisions, Futureface constructs a narrative where we all belong.”

So, this description does a pretty comprehensive job of setting up the basic premise of the work. I call it mixed-genre because it’s a little bit of: auto/biography, historical/cultural studies, and certainly takes some inspiration in style from Wagner’s journalistic background. I’ll also introduce a spoiler warning here, as I think it’s quite critical to discuss the “mystery of” Wagner’s “own ancestry,” which revolves around family lore detailing the possibility of a hidden Jewish background. While proving this genealogical background serves to catalyze Wagner’s quest, her pursuit takes her in unexpected directions. Indeed, she discovers that one of her ancestors may have traveled to the United States under an assumed name and that his name is exactly the same as a person who turns out to be a non-biologically related father. Wagner is determined figure out why these two figures were so closely connected despite having no blood relation and uses many experts and resources at her disposal to find out what she can.

On either side of her family tree, Wagner does come to one major realization: that ancestry is the stuff of myth and legend. By uncovering the contexts around her genealogy, Wagner realizes that she must look past a hagiographic perspective to engage more fully the mysteries of one’s family roots. The concluding chapters take on an interesting subject matter, as Wagner seeks to establish some quantifiable data concerning her family tree. She takes a number of DNA tests that have now become popularized and enable an individual to get a basic percentage of certain backgrounds that one possesses. The problem, as Wagner discovers, is that these tests are not all the same and give different baseline results, which gives her pause to wonder whether or not they are all that accurate.

Another element that I found fascinating about this study is that Wagner’s investigations into the procedures used to determine basic DNA groupings ultimately relies upon some ossified notions of sample populations. But, what is perhaps most notable about this publication is that Wagner’s work adds to what I consider to be one of the smaller subsets of Asian American literature: Burmese American literature. At this time, I only know of a handful of writers (such as Wendy Law-Yone, Charmaine Craig) in this area, so any new publication from this particular ethnic group is a welcome one!

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

comments

comments