Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 40

December 31, 2018

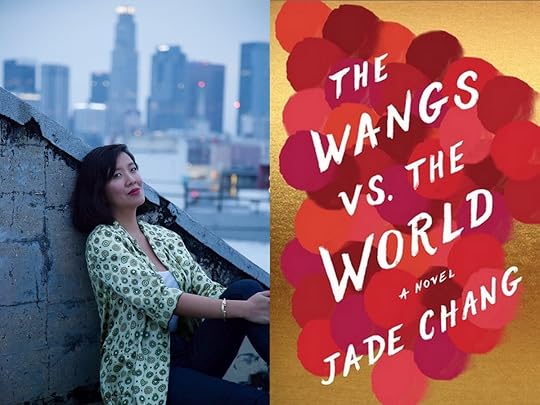

A Review of Jade Chang’s The Wangs vs. The World (Houghton Mifflin, 2016)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Jade Chang’s The Wangs vs. The World (Houghton Mifflin, 2016).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

For some reason or another, I stalled a number of times while starting this novel. I would read it, get stuck about forty or fifty pages in, then I would put it down. By the time I would pick up the novel again, I would have forgotten enough of the basic plot that I would have to start over. Part of the issue is that the novel is, by design, disjointed. The narrative perspective consistently changes among the different Wang family members. At one point, the narrative perspective even shifts to the family car. Indeed, the main formal element to note is that we have a road novel, and the Wang patriarch, Charles, is catalyzed to go on this road trip (along with his second wife Barbra) in order to pick up his younger two children (Grace, who is at a boarding school) and Andrew (who is at a university in Arizona) to head over to the eldest’s home (Saina, who lives in New York). Charles has lost the family fortune and is trying to galvanize the family by consolidating them in one place and time.

Here is a summary from Goodreads: “A hilarious debut novel about a wealthy but fractured Chinese immigrant family that had it all, only to lose every last cent - and about the road trip they take across America that binds them back together. Charles Wang is mad at America. A brash, lovable immigrant businessman who built a cosmetics empire and made a fortune, he’s just been ruined by the financial crisis. Now all Charles wants is to get his kids safely stowed away so that he can go to China and attempt to reclaim his family’s ancestral lands—and his pride. Charles pulls Andrew, his aspiring comedian son, and Grace, his style-obsessed daughter, out of schools he can no longer afford. Together with their stepmother, Barbra, they embark on a cross-country road trip from their foreclosed Bel-Air home to the upstate New York hideout of the eldest daughter, disgraced art world it-girl Saina. But with his son waylaid by a temptress in New Orleans, his wife ready to defect for a set of 1,000-thread-count sheets, and an epic smash-up in North Carolina, Charles may have to choose between the old world and the new, between keeping his family intact and finally fulfilling his dream of starting anew in China. Outrageously funny and full of charm, The Wangs vs. the World is an entirely fresh look at what it means to belong in America—and how going from glorious riches to (still name-brand) rags brings one family together in a way money never could.”

Chang’s third person narrator is a semi-distant one, in the sense that this figure is poking some fun at these characters along the way. The comic undertones of the novel make this particular work stand out amongst a number of other Asian American family novels. Chang’s work functions more in line with Gish Jen than Amy Tan, but the episodic and shifting narrative perspective occasionally creates some uneven-ness to the reading experience (at least from my position).

Saina’s backstory I found probably the most interesting, as she was an artist of some success and celebrity status, but then finds herself in a bit of a rut when the novel starts out. She’s also in a complicated love triangle. Andrew is another very interesting character: he’s interested in stand-up comedy, so there’s a meta-element at least in terms of the novel’s tonality. The relative privilege that these characters possess prior to Charles’s bankruptcy (once that coincides with the Great Recession) is also an aspect that can be polarizing: on the one hand, the lost family fortune certainly jumpstarts the plot, but on the other, you sometimes can’t help but sneer at some of the thoughts/ emotions/ and feelings provided for us through the focalizing perspective. Fortunately, Wang’s narrator is often times right there with us, making it clear that we’re sometimes meant to laugh alongside this storytelling entity.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Min Kym’s Gone: A Girl, a Violin, a Life Unstrung (Crown, 2017)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Min Kym’s Gone: A Girl, a Violin, a Life Unstrung (Crown, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

So before I started writing this review, I looked up Min Kym and listed to some of her exquisite performances online. What’s so interesting about Min Kym’s memoir Gone: A Girl, a Violin, a Life Unstrung (Crown, 2017) is that it explores the incredible attachment that the author possesses in relation to her musical instrument, a rare and almost priceless Stradivarius.

Here is a summary from B&N: “Her first violin was tiny, harsh, factory-made; her first piece was ‘Twinkle Twinkle, Little Star.’ But from the very beginning, Min Kym knew that music was the element in which she could swim and dive and soar. At seven years old, she was a prodigy, the youngest ever student at the famed Purcell School. At eleven, she won her first international prize; at eighteen, violinist great Ruggiero Ricci called her ‘the most talented violinist I’ve ever taught.’ And at twenty-one, she found ‘the one,’ the violin she would play as a soloist: a rare 1696 Stradivarius. Her career took off. She recorded the Brahms concerto and a world tour was planned. Then, in a London café, her violin was stolen. She felt as though she had lost her soulmate, and with it her sense of who she was. Overnight she became unable to play or function, stunned into silence. In this lucid and transfixing memoir, Kym reckons with the space left by her violin’s absence. She sees with new eyes her past as a child prodigy, with its isolation and crushing expectations; her combustible relationships with teachers and with a domineering boyfriend; and her navigation of two very different worlds, her traditional Korean family and her music. And in the stark yet clarifying light of her loss, she rediscovers her voice and herself.”

For Min, her particular Stradivarius allows her to find her most original and daring “violin voice,” if we might call it that. Prior to financing the purchase of Kym’s Stradivarius, the author details her upbringing as a violin prodigy, learning from gifted but equally temperamental instructors. Once Kym is connected with her Strad, her violin life truly reaches an acme. But, the memoir is hurtling toward a darker moment. When Kym is traveling, her violin is stolen, her life becomes “unstrung” as she describes it in the memoir’s subtitle.

For Kym, losing the violin is losing a part of herself, so she naturally becomes mired in a kind of depression, desperately hoping that she will be reunited with the instrument and perhaps that lost part of herself. Over time, she realizes that the theft of her violin may not be resolved, so she attempts to carve out other potential pathways in her career and in her life. She even buys a different Stradivarius, though she ultimately knows that this replacement is not the right violin for her. Eventually, the violin is recovered, but because of a complicated set of circumstances involving insurance and her own lack of funds, she cannot purchase the violin back. She is forced to see her beloved “self” be sold at auction. Kym’s memoir is particularly affecting because we can see how much melancholy exists but at this difficult locus of loss; she manages to make clear the unique bond between musicians and their instruments.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

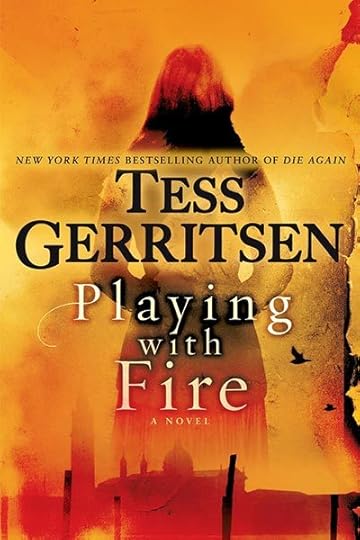

A Review of Tess Gerritsen’s Playing with Fire (Ballantine Books, 2015)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Tess Gerritsen’s Playing with Fire (Ballantine Books, 2015).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

So, once upon a time I did have a physical copy of this book, but I actually lost it. Within the last year, I was able to get a hold of an audiobook version, and I decided that it would be a great way to get “work” done, while on walks or in the car. I once tried to engage in this practice. Sometime, when I was still working up at Stanford, I decided to listen to White Tiger all the way down the 5, when I was sometimes traveling between Mountain View and Southern California. By the time I got home, I realized I had only really comprehended about 75% of what I had listened to and that I needed to read it again. Thus, you can imagine I was a little concerned that the same fate would befall me this time around.

Let’s let B&N give us some context: “In a shadowy antiques shop in Rome, violinist Julia Ansdell happens upon a curious piece of music—the Incendio waltz—and is immediately entranced by its unusual composition. Full of passion, torment, and chilling beauty, and seemingly unknown to the world, the waltz, its mournful minor key, its feverish arpeggios, appear to dance with a strange life of their own. Julia is determined to master the complex work and make its melody heard. Back home in Boston, from the moment Julia’s bow moves across the strings, drawing the waltz’s fiery notes into the air, something strange is stirred—and Julia’s world comes under threat. The music has a terrifying and inexplicable effect on her young daughter, who seems violently transformed. Convinced that the hypnotic strains of Incendio are weaving a malevolent spell, Julia sets out to discover the man and the meaning behind the score. Her quest beckons Julia to the ancient city of Venice, where she uncovers a dark, decades-old secret involving a dangerously powerful family that will stop at nothing to keep Julia from bringing the truth to light.”

What’s perhaps most interesting to me about this work is that Tess Gerritsen not only wrote this novel, but composed a piece that is meant to be Incendio. I didn’t realize it as I was listening to the audiobook, but the violin piece that I was hearing was likely the version that Gerritsen herself composed. I had no idea she was that multi-talented. For some reason, this time around I had no trouble getting immersed in this audiobook. I’m not really sure about the difference, but I do believe it has something to do with the fact that I wasn’t driving while listening to this narrative: I was mostly walking around with an earpiece.

In any case, what the description doesn’t tell you is there are, based upon my aural recall, two narrative discourses. Julia Ansdell gets a first person narrative voice and then there’s a third person narrative voice that shifts us into the past, back to pre-WWII Italy. In this period, Lorenzo Todesco is getting to know Laura Balboni, as both are talented musicians. But, you know we’re in troubled waters if we’re in pre-WWII Italy. Plus, we eventually discover that Lorenzo is Jewish, and you immediately get that sinking feeling that things will not end well. The narratives don’t really start colliding until Julia begins to feel like she is going crazy and that she must travel to Italy herself to figure out what the mystery is behind Incendio.

As she gets deeper into this mystery, Lorenzo’s narrative gets darker and darker, and ever more darker. I found the sections involving Lorenzo and Laura to be, in some ways, far more compelling than anything going on with Julia Ansdell’s life. If there is any critique to be made, I wanted a stronger connection between Ansdell and Lorenzo, more than the fact that both are musicians. The personal conflicts that mire Julia, especially the one involving the history of mental illness in her family, while exerting a kind of narrative weight, fall incredibly flat against the journey that Lorenzo must make. His arc, which does provocatively bolster the title of his violin composition, absolutely overshadows anything related to Julia. In any case, fans of Gerritsen should be pleased, as she gives them (and herself) a break from the Rizzoli & Isles series to spread her wings in other directions.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

December 28, 2018

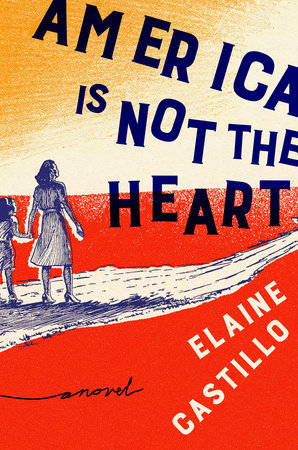

A Review of Elaine Castillo's America is Not the Heart (Viking, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) nancyhcarranza

nancyhcarranza

A Review of Elaine Castillo's America is Not the Heart (Viking, 2018)

By Nancy H. Carranza

My parents grew up during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, roaming the streets unsupervised when schools were shut down and their parents sent to labor camps. My in-laws fled the Salvadoran Civil War, with family members fighting on both sides. Now both my parents and my in-laws shop at Costco, watch Star Wars movies, and enjoy In-and-Out Burgers. For many immigrants, the question in the cover jacket of Elaine Castillo’s debut novel, America is Not the Heart (2018), touches upon a shared truth that unites their disparate and diverse histories and experiences: “How many lives fit in a lifetime?”

The publisher’s summary of the novel answers this question as such:

“When Hero De Vera arrives in America--haunted by the political upheaval in the Philippines and disowned by her parents--she's already on her third. Her uncle gives her a fresh start in the Bay Area, and he doesn't ask about her past. His younger wife knows enough about the might and secrecy of the De Vera family to keep her head down. But their daughter--the first American-born daughter in the family--can't resist asking Hero about her damaged hands.”

Part of the extraordinary poignancy of this novel is the way in which it weaves together the personal and the political, the multiple worlds inhabited by immigrants and their families. In doing so, the novel combines two popular subgenres of so-called “immigrant fiction”—the domestic narrative and the political epic, without lapsing into the clichés of either. For example, the misunderstandings and tension between Hero and Paz, her aunt-in-law, are not so much generational or even cultural, but resulting from class differences and linguistic barriers between Filipino dialects. And even though Hero spent a decade of her life as part of the New People’s Army, an actual Communist guerrilla force that has operated in the Philippines for the past 50 years, very little narration is devoted to justifying her beliefs and actions; rather than Marxist lectures, we get memories of genuine comradery and secret sexual escapades. Only near the end of the novel does Hero reveal (in fact, allow herself to remember) the very real violence and danger that engulfed her and many of her comrades.

Just as the novel transcends generic conventions of family and politics, it also complicates one of the most common premises of “immigrant fiction”—the transformation of its immigrant protagonist as she/he assimilates into or rebels against dominant (read: White) American society. America is Not the Heart breaks this mold in two ways: 1) Hero is not necessarily the “hero” of the story, and 2) the America that Hero discovers is a mostly lower middle-class, immigrant society.

Even though the majority of the novel’s third-person narration is told from the point-of-view of Hero, the novel’s prologue tells the story of Paz through a second-person “you” narration that immediately forms a connection between the reader and Paz. Later in the novel, the third-person narration is again interrupted through a “you” narration, this time from the point-of-view of Rosalyn, Hero’s friend-turned-lover. These narrative false starts and disruptions challenge the model of the singular immigrant protagonist and gesture towards the novel’s ambition to tell a more collective story. Furthermore, one of the main plot developments surrounds Paz and Uncle Pol’s marriage and their daughter, Roni, a domestic drama that relegates Hero to somewhere between sidekick and spectator.

I also found the novel’s bold disregard of dominant American society both surprising and refreshing. With a title that seems to explicitly counter Carlos Bulosan’s classic semi-autobiographical novel, America is in the Heart (1946), Castillo’s novel doesn’t so much refute Bulosan’s America as redefine it. Bulosan’s novel is primarily concerned with Filipino migrant workers’ struggles against racism and oppression, arguing that the ideals of America—freedom, democracy, upward mobility—should not be the exclusive property of Whites, but rather belonging to all its inhabitants. Racism, systemic oppression, and the aftermath of American overseas imperialism still lurk in the background of Castillo’s 1990s Bay Area, but intra-ethnic colorism and classism more obviously impact the everyday relations between characters. In the lower-middle class neighborhood of Milpitas, as Rosalyn observes, there are virtually no white people, mostly Asians and Latinos who tend to stay in their respective ethnic communities (with the exception a mixed-race character like Jaime, a “Mexipino”).

Though the novel doesn’t claim to represent a singular “Filipino American experience,” its expansive cast of characters seem to purposefully represent a diversity of dialects, socio-economic classes, sexualities, religious beliefs, and political backgrounds. Occasionally the novel lapses into an almost “ethnic tour guide” mode, as it describes various Filipino foods, music, and traditions in extreme detail. Though I found Castillo’s high realism overbearing at times (do I really need to know that Hero, upon returning home, carefully put the plate of leftovers onto the floor by the door, took off her shoes, picked up the plate, and then placed it on the kitchen table, all before having a conversation with another character?), what this fixation with the small, ostensibly mundane details of everyday life does is ground Castillo’s “America” in the concrete people and places of everyday life. Castillo does not stop at telling us that America is not “the heart,” but goes on to paint a vivid portrait of what America is: the urban strip mall with its family-owned ethnic restaurants, beauty shops, and video rental stores; house parties and car rides around the Bay; microwavable frozen pizzas, queer romances, and women who work themselves to the bone. Castillo’s America is not an elusive ideal that seems ever out of grasp, but the lived reality of its immigrant communities, an America that can be experienced, inhabited, and claimed, regardless of one’s country of origin or legal status.

Buy the book here.

comments

comments

September 26, 2018

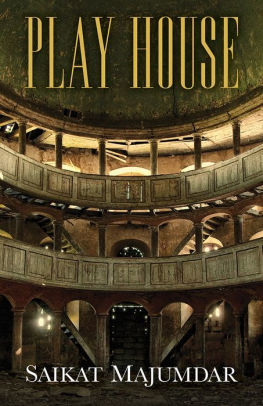

A Review of Saikat Majumdar’s Play House (Permanent Press, 2017)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) xiomara

xiomara

A Review of Saikat Majumdar’s Play House (Permanent Press, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

So I had waited on the U.S. release to review Saikat Majumdar’s superbly, dark-tinted second novel Play House (Permanent Press, 2017), because it was previously already published in India under the name The Firebird (Hatchette India, 2015). I eventually acquired both copies, possibly expecting that these editions were distinct, but the only significant change is in the title. I can see why Majumdar (also author of one previous novel Silverfish and the magisterial and brilliantly idiosyncratic Prose of the World) chose to retitle it for the U.S. edition, as the original title doesn’t encapsulate the broader expanse of the novel, which involves the theatrical culture of 1980s Calcutta. The novel is primarily told through the perspective of a young (and later adolescent) boy named Ori. We’ll let B&N provide us with some more critical information:

“For ten-year-old Ori, his mother's life as a theatre actress holds as much fascination as it does fear. Approaching adolescence in an unstable home, he is haunted by her nightly stage appearances, and the suspicion and resentment her profession evokes in people around her, at home and among their neighbors. Increasingly consumed by an obsessive hatred of the stage, Ori is irrevocably drawn into a pattern of behavior that can only have catastrophic consequences. Political bullies, actors and actresses, hairdressers, set boys and backstage crew make up the world of Play House, a haunting exploration of a young boy stumbling into adulthood far ahead of his years. This is the first US edition of one of the most widely read and acclaimed recent Indian works of literary fiction.”

Ori’s mother Garima obviously struggles to gain a foothold as a theatre actress amid oppressive cultural and geographical contexts, which can position female artists as glorified prostitutes or sex workers. Ori and Garima’s extended family members are additionally troubled by her profession. One ally the two do find is Shruti, Ori’s cousin and Garima’s niece, a young teenager who is one of Ori’s closest companions throughout the novel. The problem with the familial context is that Ori’s father is in some form of health decline and cannot engage in any childcare. His mother, being the sole breadwinner and arduously wedded to her career as a theater actress, cannot necessarily be relied upon to oversee him, especially because she is committed to her craft (meaning that she occasionally must travel for work, perform during odd hours, etc). Majumdar is navigating tricky waters here: his portrayal doesn’t cast Garima as categorically neglectful or unnecessarily selfish, but she is ultimately subject to a cultural ethos in which her manner of work is seen as subversive and excessive. But Majumdar’s depiction of the theater industry does not see producers or actors as purveyors of some artistic truth: indeed, they, too, are caught up in the potential forces and forms of corruption, all of which continually return us back to the subjugation of women outside of and within artistic realms. These dual gendered circumscriptions are perhaps what makes this novel so tragic: we desperately desire that Ori/ Garima find a way to move beyond these suffocating circumstances, but perhaps this impasse is part of the naturalistic point. Ori’s very tenuous existence is always mirroring and refracting the tenuousness of his mother’s career aspirations. If motherhood and professionalism are seen as non-synchronous paths, the unyielding and ominous resolution that eventually unfolds certainly makes sense. Perhaps, what is most compelling about Majumdar’s multi-texted work is its evocation of the third person narrator, one who closely follows the interiorities of the novel’s characters. Readers are hamstrung (in the best way possible) by the narrative perspective because we’re led to see this strange and beguiling world through the eyes of this young boy (at least primarily) and to see how naively he understands his mother’s profession (at first). Over time, though, Ori’s developmental trajectory begins to reveal a subtly tactical impulse that generates an appropriately dour pall over the final pages. I read this novel in one sitting precisely because of this narrative perspective: we want to see how Ori will end up and find out what he will do once he decides to become an agent of potential change, despite how limited his power may be. On another note—and here’s where I reveal a little bit of my own autobiographical investments in this work—it’s interesting to consider this novel from the perspective of Asian Americanist critique. On the one hand, the narrative itself remains largely contained by its urban borders (in Calcutta), but I have firsthand knowledge that the author has spent many years in the United States. His positionality as a transnational writer makes this work a little bit more difficult to categorize, and I believe it would be limiting to label this work solely as a postcolonial Anglophone text. In any case, let us give thanks to the publication gods that there is a U.S. release of this title, so that you can treat yourself by reading it! =)

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Xiomara Forbez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don't hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Xiomara Forbez, PhD Candidate in Critical Dance Studies, at xforb001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Dickson Lam’s Paper Sons (Autumn House Press, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) xiomara

xiomara

A Review of Dickson Lam’s Paper Sons (Autumn House Press, 2018).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Well, for anybody who is interested in Asian American studies, a title like Paper Sons is going to land squarely in their wheelhouse. At the same time, Dickson Lam’s creative nonfiction work (and debut) Paper Sons doesn’t necessarily draw from a personal account of having been a titular fictive genealogical child. Rather, Lam comes to understand his place as a Chinese American through a complicated trajectory. We get a crystalline view of his impoverished childhood and, later, through his concerted efforts to reform his life, we get a stronger sense of his cultural history. The official website provides this overview:

“Dickson Lam’s Paper Sons combines memoir and cultural history, the quest for an absent father and the struggle for social justice, naming traditions in graffiti and in Chinese culture. Violence marks the story at every turn—from Mao to Malcolm X, from the projects in San Francisco to the lynching of Asians during the California Gold Rush. After one of his former students at the June Jordan School of Equity is gunned down on a street corner, Lam is compelled to tell a mosaic of stories. What does it take, in this social context, to become a person who respects himself and holds hope for those coming up through a culture of exclusion and violence? Lam writes with a depth of hard-won understandings both political and psychological. This is an important book, beautifully crafted, rich in poetic image and juxtapositions, that offers insight and compassion for a nation struggling to make sense of its immigrant nature. I congratulate Dickson Lam on this fine work.”

This description provides a very useful condensation of the text, which is largely structured through vignettes and doesn’t have a standard chronology. The work opens up with a compelling and tragic account of Lam’s experiences as an instructor at June Jordan School of Equity. The death of Lam’s former student is the occasion not only to think about the complicated challenges of teaching, but also to ponder his own bumpy road toward becoming a teacher, one littered with misadventures, buses (and graffiti), and family dysfunction. Here, I should provide a spoiler alert because one of the most critical narrative throughlines is Lam’s rocky relationship with his father. Indeed, the fraying between father and son occurs very early on, especially as Lam’s father moves to Minnesota in search of better job opportunities, but which not surprisingly begins to create marital strain. It also becomes evident that Lam must reconcile his melancholic attachment to his father with the violence that Lam’s father perpetrated on his sister. So toward the work’s conclusion Lam admits, “For my part, I’m not done yet with Bah Ba. Probably never will be. In writing this book, I’d hoped to be freed from my father, that I’d exhausted my obsession with him, but our bond has only strengthened. He’ll remain a permanent character in my story. We’ve become pieces on a board game that will never end” (232). What is intriguing about this perspective is that he begins to position his own father as part of a genealogy of the chess games that have obsessed him in his adulthood. He begins to see his life as one that, though seeming unchangeable, could at least be entertained in other iterations through the imagination. And this alternative timeline is where he leaves us, with a sense of other possibilities, the kinds which, no doubt, inspire his teaching and drive him to advocate for students who come from backgrounds not so unlike his own. In this way, I found this particular memoir to possess an organic grittiness that was lacking from Michelle Kuo’s Reading with Patrick. In that particular work, it was evident that Kuo’s transitory teaching gig and similarly unstable teaching program would undo the inroads she had made as an instructor. In Paper Sons, we see an instructor who is trying to reorient the chess pieces, to create games with better outcomes, and to prepare a future path with more avenues not only for himself but for others. Kuo’s participation in the so-called system of educational games is unlike Lam’s: Lam situates himself as part of the game itself, thus drawing upon a very personal motivation that strikes the fire and stokes it to burn throughout this memoir. The other intriguing element of Lam’s Paper Sons is the importance of black culture and history on Asian American identity. Here, Lam clarifies that this connection is not so much appropriative, as it is informed by an alignment of a class-based community that moves across racial lines. This interracial perspective is one again that I thought separated itself from Kuo’s, which seemed more distant. Ultimately, a compelling work!

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don't hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Xiomara Forbez, PhD Candidate in Critical Dance Studies, at xforb001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

September 25, 2018

A Review of Jeanette M. Ng’s Under the Pendulum Sun (Angry Robot, 2017)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) xiomara

xiomara

A Review of Jeanette M. Ng’s Under the Pendulum Sun (Angry Robot, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Well, Jeanette M. Ng’s Under the Pendulum Sun (Angry Robot, 2017) has, at least for me, one of the more intriguing premises for new reads I’ve encountered this year. This rather anemic description over at B&N doesn’t give too much away:

“Catherine Helstone’s brother, Laon, has disappeared in Arcadia, legendary land of the magical fae. Desperate for news of him, she makes the perilous journey, but once there, she finds herself alone and isolated in the sinister house of Gethsemane. At last there comes news: her beloved brother is riding to be reunited with her soon – but the Queen of the Fae and her insane court are hard on his heels.”

I suppose this summary does a strong enough job of giving us the basics, but there are a couple of key individuals that Catherine Helstone meets, while living at Gethsemane. First, she arrives there alongside a changeling named Ariel Davenport. Ariel is gregarious and seemingly always hungry. They are attended to by a kind of butler, a gnome named Mr. Benjamin. Mr. Benjamin is key to this story because the reason why Laon is in Arcadia in the first place is that he is there to proselytize. Yes, he is seeking to establish Christianity in the land of the Fae. Finally, there is a mysterious manager to the house, a female fae named the Salamander, who occasionally makes her presence known, but otherwise sticks to the shadows. Ng adds some mystery into the equation because there was a previous missionary sent out to Arcadia (a man by the name of Roche) who disappears and whose whereabouts are unknown. While Catherine waits for Laon to arrive, she gets into some mischief leafing through Roche’s old journals, finding out that he was trying to discern fairy language, something he believed was called Enochian. His attitude was that he would be able to convert more fae if he could speak with them in a common language. In any case, Laon eventually returns, but his arrival only brings more questions: why is he so cold to Catherine? And what about all of the strange goings-on at Gethsemane, including the fact that she once bumped into a strange, seemingly mad woman in black? If you’re feeling shades of Jane Eyre, you’re not wrong at all, because Ng is obviously playing with a lot of these more gothic tropes. But, here is where I pause—and I am providing you with my spoiler warning here, so do not read on at this point unless you want to know all of the tricks that Ng has up her sleeve—because Ng stages at least two surprises in the back half of the book. The first is one that she telegraphs with too much information: Laon and Catherine are apparently in love with each other. The second is that Catherine discovers that she’s actually a changeling, a fact which seems to make it more acceptable (at least from what it seemed like in the text) that they were embarking in an incestuous relationship with each other. The “final” twist that Ng provides us is the fairylands may be some sort of variation on hell and that the fairies exist to create dilemmas for humans that ultimately lead them into sin. In this particular case, Catherine’s arrival into the land of the fae tempts Laon to the point where he gives in to his lust. Catherine thus becomes a pawn in a larger “game” in which the fae can cause Laon and Catherine’s collective fall. Finally, Catherine’s revelation that she is a changeling is discovered to be false. Indeed, when Ariel Davenport tells Catherine to kill her (instead of allowing Queen Mab to do so during a hunt), it’s because Ariel Davenport was led to believe that Catherine was a changeling, exactly so that Catherine would end up killing her and leading all the characters down their path of ruin. Queen Mab thus becomes the architect of many characters’ downfalls, but the conclusion sees Catherine and Laon realize that, though they have now sinned, their quests are ever more important. Why not try to do what they came there to do, they ask themselves, despite the fact that they may indeed be in hell. The novel is compelling and something more akin to a novel of ideas than a speculative fiction in many ways. But Ng takes a little bit too much time to get us to the “meat” of the matter. Indeed, Catherine isn’t left with much to do until Ariel mistakenly tells her that’s she’s a changeling and must murder Ariel (as a kind of mercy killing). From that point forward, the pacing finally moves at the speed it should have. Otherwise, Ng’s incredibly gifted at world-building. Gethsemane and the fairylands are otherworldly, simultaneously beautiful and menacing, with creatures and entities fit for Alex Garland’s filmic adaptation of Annihilation from the Southern Reach trilogy.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Xiomara Forbez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don't hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Xiomara Forbez, PhD Candidate in Critical Dance Studies, at xforb001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Jon Pineda’s Let’s No One Get Hurt (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) xiomara

xiomara

A Review of Jon Pineda’s Let’s No One Get Hurt (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018).

by Stephen Hong Sohn

It’s always a moment of celebration when a poet delves further into narrative territory. There’s something incandescent about a poet’s prose, even if the words don’t necessarily meld into a coherent, flowing plot; one is always adrift in a beautiful current of language. Such is the case with Jon Pineda’s latest fictional offering Let’s No One Get Hurt (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018). Pineda is also author of a number of poetry collections (Plyduck reviewed Birthmark this-a-way); the devastating memoir Sleep in Me (earlier reviewed on AALF also by Pylduck); and the novel Apology. So let’s let B&N take it away:

“With the cinematic and terrifying beauty of the American South humming behind each line, Jon Pineda’s Let’s No One Get Hurt is a coming-of-age story set equally between real-world issues of race and socioeconomics, and a magical, Huck Finn-esque universe of community and exploration. Fifteen-year-old Pearl is squatting in an abandoned boathouse with her father, a disgraced college professor, and two other grown men, deep in the swamps of the American South. All four live on the fringe, scavenging what they can—catfish, lumber, scraps for their ailing dog. Despite the isolation, Pearl feels at home with her makeshift family: the three men care for Pearl and teach her what they know of the world. Mason Boyd, aka “Main Boy,” is from a nearby affluent neighborhood where he and his raucous friends ride around in tricked-out golf carts, shoot their fathers’ shotguns, and aspire to make Internet pranking videos. While Pearl is out scavenging in the woods, she meets Main Boy, who eventually reveals that his father has purchased the property on which Pearl and the others are squatting. With all the power in Main Boy’s hands, a very unbalanced relationship forms between the two kids, culminating in a devastating scene of violence and humiliation.”

I appreciate this description, as there is a very Carrie-like scene that occurs in this novel. Fortunately, the ragtag alternative kinship that Pearl and her father have made (with two friends, Dox and Fritters) provides her with much needed support. The emotional heart of this novel is actually in the problem of Pearl’s relationship with her mother, who by the point the novel opens, had been institutionalized for suicide. Though the mother presumably recovers, she never actually returns to the family. She doesn’t finish her dissertation, while Pearl’s father, a college professor who somehow has lost tenure (not sure exactly what happened there) has become an alcoholic, lost his aforementioned job, and is basically squatting on land. Pearl allows us into this complicated and checkered past, giving us a strong indication as to why she and her father are just trying to make ends meet. They literally live off the land, so when any emergencies come up, they present real issues for the foursome. At one point, when Pearl’s father suffers some sort of injury, the car needed to retrieve him from the hospital breaks down. Thus Pearl and Fritter (I think it was; and excuse me if this plot point is incorrect, as I’ve been sometimes slow to write up my reviews following the completion of a novel) have to make their way to that location via raft. These scenes are the ones that most evoke the comparisons to Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, at least revised for the 21st century. What is always evident in this novel is Pearl’s indomitable spirit: she is wise enough to understand that her value is beyond her earnings. Pineda’s luminous prose will always keep you as buoyed as ever, even when the novel itself does not necessarily contain cataclysmic plot elements or some deliberately crafted mystery. Readers may precisely criticize this work for its more dream-like qualities, but this aspect is perhaps a trademark of Pineda’s entire oeuvre, a style in which he excels and which, I believe, is absolutely ideal with the southern gothic mode through which the narrative propels itself ever forward.

Buy the book here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Xiomara Forbez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don't hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Xiomara Forbez, PhD Candidate in Critical Dance Studies, at xforb001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

September 24, 2018

A Review of Rahna Reiko Rizzuto’s Shadow Child (Grand Central Publishing, 2018).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) xiomara

xiomara

A Review of Rahna Reiko Rizzuto’s Shadow Child (Grand Central Publishing, 2018).

by Stephen Hong Sohn

I remember e-mailing Rahna Reiko Rizzuto after having read her wonderful memoir, Hiroshima in the Morning (reviewed on AALF), because I was wondering what else she had cooking. Rizzuto had replied in part by stating that she was still working on a novel, which was actually why she originally had traveled to Japan to conduct research. Well, that novel she’d been working on is now here: Shadow Child (Grand Central Publishing, 2018). B&N provides us with this sense of the book’s content:

“Twin sisters Hana and Kei grew up in a tiny Hawaiian town in the 1950s and 1960s, so close they shared the same nickname. Raised in dreamlike isolation by their loving but unstable mother, they were fatherless, mixed-race, and utterly inseparable, devoted to one another. But when their cherished threesome with Mama is broken, and then further shattered by a violent, nearly fatal betrayal that neither young woman can forgive, it seems their bond may be severed forever--until, six years later, Kei arrives on Hana's lonely Manhattan doorstep with a secret that will change everything. Told in interwoven narratives that glide seamlessly between the gritty streets of New York, the lush and dangerous landscape of Hawaii, and the horrors of the Japanese internment camps and the bombing of Hiroshima, Shadow Child is set against an epic sweep of history. Volcanos, tsunamis, abandonment, racism, and war form the urgent, unforgettable backdrop of this intimate, evocative, and deeply moving story of motherhood, sisterhood, and second chances.”

This description does give us a strong sense of the stakes, but without too much specificity. The novel actually opens with a crime: Hana arrives at her apartment realizing her place has been vandalized. She discovers her twin sister Kei is in her bathroom passed out and unconscious. This event moves the novel forward, as readers try to figure out why the two sisters are so estranged, why Hana has left for New York City and has basically disavowed her family. Rizzuto is patient in allowing the novel to unfold, and we discover that Hana and Kei’s mother (Lillie) has a number of secrets, including the fact that she was interned, then later deported to Japan with her then-kibei husband Donald and their son Toshie. But it is not the best time, not surprisingly to go to Japan: Lillie is soon drafted to translate for the Japanese military, while Donald goes into hiding to avoid being conscripted and takes Toshie with him. Though fortunately Lillie is out of Hiroshima when it is bombed, one of her best friends (named Hanako) is not so lucky. Lillie also is unable to locate her husband or her son. During the occupation period, Lillie realizes that her best chance to get back to the United States is to take the identity of someone else, so she uses this method to get to Hawai‘i to make a fresh start. Though her new life allows her a critical reset, complications arise as Hana and Kei grow up. Kei ends up surviving a traumatic event: a tidal wave that sweeps through the area. This moment is the starting point of a fissure between the twins: Hana’s much more introverted and artistic, while Kei is more outgoing and immediately latches onto the cool crowd. The novel moves inexorably toward the cataclysmic rupture point that causes the two to separate so drastically from each other. In the diegetic present, Hana is coming to the realization that Kei’s unconscious state may be more serious and indeed Kei slips into a coma. During this period, Hana discovers that her mother had another child and likely another life entirely. She also comes to grips with the possibility that she did not fully understand what had occurred to her in her teens, when she felt disavowed by both her mother and her sister. What the novel is moving toward is a possible rapprochement between the sisters, though I have to admit I was a little bit confused about the events that involving both Kei and Hana at the conclusion. Indeed, Rizzuto uses a mixture of narrative perspectives, including third, second, and first person that is both bewildering, but necessarily appropriate to the logic of the story. Hana’s not entirely reliable, nor is Kei, who in her unconscious state, must come to terms with her responsibility toward her sister. And finally, the third person narrative, perhaps the least complicated of the viewpoints, moves through a different historical register that leaves a number of plotting events largely unclosed. Nevertheless, Rizzuto’s word finds its strongest ground in the unshakeable obsession that the sisters have with each other, which moves the reader toward that possible reconciliation.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Xiomara Forbez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don't hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Xiomara Forbez, PhD Candidate in Critical Dance Studies at xforb001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

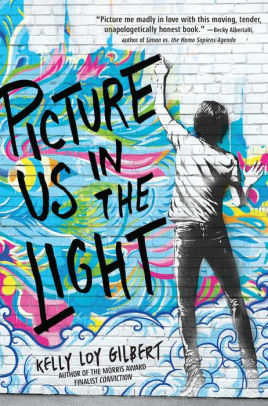

A Review of Kelly Loy Gilbert’s Picture us in The Light (Disney Hyperion, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) xiomara

xiomara

A Review of Kelly Loy Gilbert’s Picture us in The Light (Disney Hyperion, 2018).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I have been a big fan of Kelly Loy Gilbert since reading Conviction, which was definitely one of the YA reads that had more weight and heft to it. Gilbert continues the tradition of writing socially conscious YA with her next publication, Picture us in The Light (Disney Hyperion, 2018). We’ll let B&N take it from here to give us context:

“Danny Cheng has always known his parents have secrets. But when he discovers a taped-up box in his father's closet filled with old letters and a file on a powerful Silicon Valley family, he realizes there's much more to his family's past than he ever imagined. Danny has been an artist for as long as he can remember and it seems his path is set, with a scholarship to RISD and his family's blessing to pursue the career he's always dreamed of. Still, contemplating a future without his best friend, Harry Wong, by his side makes Danny feel a panic he can barely put into words. Harry and Danny's lives are deeply intertwined and as they approach the one-year anniversary of a tragedy that shook their friend group to its core, Danny can't stop asking himself if Harry is truly in love with his girlfriend, Regina Chan. When Danny digs deeper into his parents' past, he uncovers a secret that disturbs the foundations of his family history and the carefully constructed facade his parents have maintained begins to crumble. With everything he loves in danger of being stripped away, Danny must face the ghosts of the past in order to build a future that belongs to him.”

So, let’s preface my review of the book first with a spoiler alert, because this novel is, in some sense, a coming to conscious realization. A pause here to remind you: do not read forward unless you want critical details of the plot to be revealed. Much like Benjamin Alire Saenz’s Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, this novel chooses to make the protagonist one who (at least) partially withholds his own sense of affection for his best friend. It becomes apparent (with subtle cues offered by Gilbert) that Danny harbors romantic feelings for Harry, even if he won’t admit it, either in his internal monologue or direct speech. Eventually, and patiently, Gilbert leads us to see how Danny faces this fact. It would have been amazing to have read a book like this one in high school, and I truly hope that it gets adopted at that level, as it will provide young queers of color the opportunity to see themselves reflected (in all of their complicated ways) in the fictional world. The other major plotting issue involves the secret of Danny’s parents, who, as we discover, may be on the lam. Danny had always assumed that his sister was dead, but, in fact, she ends up getting accidentally routed into an adoption agency. She eventually ends up in the United States. Though Danny’s parents track her down, their biological daughter has made a new life with a new family, all of whom are not necessarily keen on any sort of reunion. In any case, this intricate backstory continually causes interruptions to Danny’s aspirations of becoming an artist, and this novel is as much about familial dynamics as it is a coming-of-age for Danny in relation to his sexuality. The ending is especially understated but fully appropriate for this thoughtful and mature outing by Gilbert.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Editor: Xiomara Forbez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don't hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Xiomara Forbez, PhD Candidate in Critical Dance Studies, at xforb001@ucr.edu

comments

comments