Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 38

July 8, 2019

A Review of Ruvanee Pietersz Vilhauer’s The Water Diviner and Other Stories (U of Iowa Press 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Ruvanee Pietersz Vilhauer’s The Water Diviner and Other Stories (University of Iowa Press 2018)

By Gnei Soraya Zarook

I was pleasantly surprised by Ruvanee Pietersz Vilhauer’s The Water Diviner and Other Stories. I didn’t quite know what to do with this collection the first time around, and had to read it twice in order to be able to truly parse it out. Before I go any further, a short summary from the University of Iowa Press:

“In this thought-provoking collection, Sri Lankan immigrants grapple with events that challenge perspectives and alter lives. A volunteer faces memories of wartime violence when she meets a cantankerous old lady on a Meals on Wheels route. A lonely widow obsessed with an impending apocalypse meets an oddly inspiring man. A maidservant challenges class divisions when she becomes an American professor’s wife. An angry tenant fights suspicion when her landlord is burgled. Hardened inmates challenge a young jail psychiatrist’s competence. A father wonders whether to expose his young son’s bully at a basketball game. A student facing poverty courts a benefactor. And in the depths of an isolated Wyoming winter, a woman tries to resist a con artist. These and other tales explore the immigrant experience with a piercing authenticity.”

The fifteen stories in this collection are as varied and sweeping as the summary suggests. This variety is part of what I appreciate about this collection; I don’t think I had quite read so many recognizable characters in such unrecognizable circumstances. This collection definitely illustrated for me how rich and diverse a collection of stories about immigrants from Sri Lanka can be, seeing as there aren’t that many short story collections out there that depict such a thing.

The first story, “The Beauty Queen” starts off on familiar ground, with an adult narrator, Rupa, grappling with the guilt of an incident that happened while she was in school: being chosen over her friend Suja to carry their house banner at the annual school sports meet because she is fair-skinned while Suja is darker-skinned. What seems small and inconsequential takes on a deeper meaning as the story ruminates on how every day decisions amount to larger impacts. In this story, Rupa’s lack of making such decisions when they might have helped her friend Suja, continue to haunt her into adulthood.

I think this first story sets the tone for what this collection does so well, which is that it grapples with the ways in which circumstance can sometimes mean everything and nothing in shaping a person. The same ideas come through in another of my favorite stories, “Today is the Day,” where an elderly Tamil woman asks the Sinhalese woman delivering her Meals on Wheels meal to stay with her because she will die on this day and does not want to do so alone. This story comes back around to the questions that much of the collection ponders; namely, whose responsibility is it to account for decades of violence when such violence lingers in the present, and, moreover, what might such an accounting for look like?

These notions of circumstance and responsibility reappear in different ways throughout the collection, as characters often come face to face with new and difficult people, or new understandings of people they are already familiar with. Two of the most captivating stories that are great examples of such points of encounter are “The Rat Tree” and “Therapy,” and I’m wondering how much of Vilhauer’s background as a clinical associate professor of psychology is lending towards this nuance. Both stories feature therapists struggling to come to terms with who their patients are (or who they suspect them to be), and through this process, to come to terms with their own sense of self. Within these two stories as well is the question of responsibility to others, particularly when one occupies, however fleetingly, a position of power over others.

I was struck by Vilhauer’s ability to paint a range of different voices. I was completely enamoured with the narrator of “The Lepidopterist,” a neuroatypical child who grows up to be an accomplished lepidopterist. Similarly, the financially struggling students in “The Fellowship” and “Security” I found to be completely believable, if extremely unlikeable, in the choices they each make. “Hopper Day” and “Leisure” are incredible additions to the stories on maids/servants and their complicated positions within Sri Lankan families. “A Burglary on Quarry Lane,” “Here in This America,” “The Accident,” and “Hello, My Dear” bring up questions of immigration, assimilation, diaspora, race, and class.

One of the places I was left wanting more was at the end of “Sunny’s Last Game,” where the parents’ fears of their young son being bullied turn out to be unfounded. I'm not sure about how I would reconcile this ending with the racial slurs aimed at Sunny, and the general whiteness of the Brown School he attends. The title story, “The Water Diviner,” was endearing and left me wanting (to know) more also, although my failure as a reader is that I haven’t been able to pinpoint what it is I want exactly, even after two readings.

I think this confusion speaks to one of the problems I had reading this collection and writing this review: that I have so few references for short stories about immigrants from Sri Lanka that I am not adept at knowing what to do when I read one, especially one with characters who occupy such a wide cast of subject positions that feel unfamiliar because I’ve never encountered them in literature before (due to both my lack of reading knowledge and a lack of representation in general). For the fact that this collection fills in that gap with such varied characters that you come to care about so quickly, this is an important addition to literature about Sri Lankan immigrants that complicates ideas of home and abroad, insider and outsider, race and ethnicity, and violence and justice.

Buy the Book Here!

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

April 20, 2019

A Review of Zen Cho’s The True Queen (DAW 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Zen Cho’s The True Queen (DAW 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Zen Cho’s The True Queen (DAW 2019) was on my highly anticipated list due to Cho’s earlier publication Sorcerer to the Crown. The True Queen is not a direct sequel to Sorcerer to the Crown, though Prunella Wythe (formerly Prunella Gentleman) and other characters do return. We’ll let B&N give us some background at this point: “When sisters Muna and Sakti wake up on the peaceful beach of the island of Janda Baik, they can’t remember anything, except that they are bound as only sisters can be. They have been cursed by an unknown enchanter, and slowly Sakti starts to fade away. The only hope of saving her is to go to distant Britain, where the Sorceress Royal has established an academy to train women in magic. If Muna is to save her sister, she must learn to navigate high society, and trick the English magicians into believing she is a magical prodigy. As she's drawn into their intrigues, she must uncover the secrets of her past, and journey into a world with more magic than she had ever dreamed.”

So this particular novel focuses much more on the Malaysian side of the equation. When Sakti and Muna are traveling to Britain through a shortcut that requires them to move through the Fairy dimension, Sakti disappears. Once Muna arrives there, she realizes that she is essentially stuck there, without her mentor Mak Genggang, a highly powerful witch who was mentoring Sakti and Muna. One of the rules of Fairy is that it’s much harder to travel to that realm from the British side than it is on the Malaysian side, so Muna must use her allies in Britain to help devise a way to find Sakti. The other major storyline involves the Fairy Queen, who has lost a magical item known as the Virtu. The Virtu is essentially a kind of amulet that has been broken into two; it is essential for the Fairy Queen because she wants to consume it in order to take its power into her. The Fairy Queen is worried that there is an insurgency rising up against her and fears it may be stemming from sources in Britain.

The two plots collide once one of the Fairy Queen’s henchman (the Duke of the Navel of the Seas, I think his name was) arrives at the Sorceress Royal’s academy demanding the Virtu, otherwise killing everyone there. While Prunella and others work to appease the Duke, Muna and one of the other instructors (Henrietta Stapleton) have traveled to the Fairy dimension to save an imprisoned figure, who possesses information that may be crucial to figuring out the location of the Virtu and to dispelling the wrath of the Fairy Queen. I may have gotten some plot points imprecise for which I apologize, but frankly, I had a much harder time following this novel than the last one. I also have to put in some spoilers here because the novel starts really picking up toward the end.

The biggest mystery that the novel poses is the identities of Sakti and Muna; when they wash up on the beach on Janda Baik, they have no idea who they are and neither does the reader. Cho’s biggest trick in this novel (at least from my readerly perspective) is keeping us off the scent of who they actually are and why their powers are so different. At some point, given what Muna learns in the Fairy realms she begins to believe that Sakti is none other than the “true queen,” a serpent-figured fairy that is going to take back the throne from her sister, the current Fairy Queen, but what Muna and others eventually discover is that Sakti and Muna are not unlike the Virtu, as when the “true queen” was banished from the Fairy realms, she was also split into two. Muna became the “bodily” and “material” portion while Sakti was the “spiritual” and “magical” portion. Muna must eventually make a crucial decision about how to bring about the union of Sakti and Muna, with or without their ability to remain separate entities.

This concluding arc is where the novel was most richly engaged (at least from me), but I will say I was somewhat disappointed by Cho’s choice to move in this direction. Prunella was such a fun and comic character that I had hoped to read much more about her adventures. The last novel also leaves us with the question of how Prunella would be raising her familiars, which goes almost entirely untouched in this second work. Let’s hope she returns to Prunella’s time as the Sorceress Royal, so we can see how she deals with being her own “queen of the dragons.”

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Yoon Ha Lee’s Dragon Pearl (Disney Hyperion/ Rick Riordan Presents 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Yoon Ha Lee’s Dragon Pearl (Disney Hyperion/ Rick Riordan Presents 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I recently taught the short story “The Battle of Candle Arc” in my graduate course on Asian American speculative fiction, so I’ve been in a Yoon Ha Lee frame of mind. Intriguingly, Lee has moved into the YA terrain with Dragon Pearl (Disney Hyperion/ Rick Riordan Presents 2019). Let’s let B&N give us some information about this title: “Rick Riordan Presents Yoon Ha Lee's space opera about thirteen-year-old Min, who comes from a long line of fox spirits. But you'd never know it by looking at her. To keep the family safe, Min's mother insists that none of them use any fox-magic, such as Charm or shape-shifting. They must appear human at all times. Min feels hemmed in by the household rules and resents the endless chores, the cousins who crowd her, and the aunties who judge her. She would like nothing more than to escape Jinju, her neglected, dust-ridden, and impoverished planet. She's counting the days until she can follow her older brother, Jun, into the Space Forces and see more of the Thousand Worlds. When word arrives that Jun is suspected of leaving his post to go in search of the Dragon Pearl, Min knows that something is wrong. Jun would never desert his battle cruiser, even for a mystical object rumored to have tremendous power. She decides to run away to find him and clear his name. Min's quest will have her meeting gamblers, pirates, and vengeful ghosts. It will involve deception, lies, and sabotage. She will be forced to use more fox-magic than ever before, and to rely on all of her cleverness and bravery. The outcome may not be what she had hoped, but it has the potential to exceed her wildest dreams. This sci-fi adventure with the underpinnings of Korean mythology will transport you to a world far beyond your imagination.”

The fox has been all over the place with my reading, especially since I just finished Julie Kagawa’s Shadow of the Fox. Apparently, Lee has stated that Dragon Pearl is a stand-alone, though the conclusion did seem to gesture to possible future adventures. In any case, Min eventually goes off on her journey to find out what happened to Jun, but that path takes her on a ship that gets attacked. In that attack, Min is wounded. It is during her recovery that she realizes that the best chance to find out what happened to Jun is to impersonate Jang, a cadet who had been killed during that attack. Jang’s ghost assents to Min taking on his form, but the challenge is apparent: Min must get along with Jang’s former friends (two supernaturals, who are cadets who are also shapeshifters: a dragon and a goblin), while also trying to acculturate quickly to military communities. Eventually, Min gets the hang of Jang’s life, while also managing to find out more information about Jun and his apparent military desertion. It becomes evident that the captain of the ship (a supernatural whose original form is a tiger) knows more than he is letting on not only about the all-powerful dragon pearl, but also about how Jun may have been involved in the retrieval of this dangerous artifact.

The YA fiction shows Lee’s ability to master multiple genres, as he delves into the teenage realm. Especially coming off the very complicated fictional worlds offered up in the Raven Stratagem series, I can’t help but be impressed by Lee’s adaptability. Part of the success of this work is Lee’s choice to use the first person perspective, which is absolutely the right one given the highly subjective nature of Min’s observations. I’ve also been impressed by Lee’s ability to consider the political dimensions of something like a fox subjectivity, which becomes a convenient metaphor by which characters face modes of disempowerment due to their status as beings that are socially different. In this way, this YA fiction is necessarily one that can be brought into the classroom. Finally, Lee’s judicious and textured use of Korean culture (as it is allegorically embedded) makes this particular fictional world especially rich, one that will no doubt please fans of the YA genre and those seeking “diverse” voices in the representational terrains.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of T Kira Madden’s Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls (Bloomsbury USA, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of T Kira Madden’s Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls (Bloomsbury USA, 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I read this memoir around the same time as Anuradha Bhagwati’s Unbecoming, which seemed to me a fitting to read together. Both memoirs deal with the complications of growing up. I’ll let B&N take it away from here: “Acclaimed literary essayist T Kira Madden's raw and redemptive debut memoir is about coming of age and reckoning with desire as a queer, biracial teenager amidst the fierce contradictions of Boca Raton, Florida, a place where she found cult-like privilege, shocking racial disparities, rampant white-collar crime, and powerfully destructive standards of beauty hiding in plain sight. As a child, Madden lived a life of extravagance, from her exclusive private school to her equestrian trophies and designer shoe-brand name. But under the surface was a wild instability. The only child of parents continually battling drug and alcohol addictions, Madden confronted her environment alone. Facing a culture of assault and objectification, she found lifelines in the desperately loving friendships of fatherless girls. With unflinching honesty and lyrical prose, spanning from 1960s Hawai’i to the present-day struggle of a young woman mourning the loss of a father while unearthing truths that reframe her reality, Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls is equal parts eulogy and love letter. It's a story about trauma and forgiveness, about families of blood and affinity, both lost and found, unmade and rebuilt, crooked and beautiful.”

It’s interesting that they introduce Madden as an essayist, as I was listening to a podcast with Madden in which she states that this work is a hybrid essay/memoir type work. I’ve begun wondering what really is the difference between essays and memoir, and the only thing I’ve really come up with is the question of length and of content. The essay can be on any particular subject, but is fairly short in length, while the memoir is typically a longer form, focused on the subjectivity of one’s memories and experiences. Because Madden’s work is so episodic in structure and non-chronological in layout, the essay moniker seems appropriate, while the individual parts accrue larger cohesion as a whole, thus leading us to understand it as a memoir. Madden admits in that podcast as a kind of side joke that we shouldn’t tell the publisher that she’s billed it herself as an essay-memoir, perhaps as a node that the work doesn’t achieve market legibility by being listed in this way, but I am digressing away from the content.

The description does a very good job of giving us the particulars here, but the title is itself a little bit misleading: “fatherless” is seen at least at that point in the memoir as something that is more metaphorical for Madden, whose father (and actually both parents) aren’t always very physically or psychically present for her. Madden’s teenage years are largely spent finding alternative communities beyond the home, but without much supervision, she experiences a violent sexual assault and must contend with a series of complicated relationships throughout this period. But despite the “fatherless” title, this essay-memoir collection is also about Madden’s extreme and fierce love for her mother and father, and how this collection is as much a tribute to her parents as it is about finding her way in a sometimes parent-less world.

The concluding chapters are particularly affecting. Readers are slowly prepped for Madden’s eventual reveal that her father has died, and that’s she’s trying to negotiate a life without him. When the term “fatherless” becomes literal through death, Madden’s work takes on a highly affective, elegiac tonality that is perfectly luminescent. Never hagiographic in its depictions, the essay-memoir leads us to understand Madden’s father and mother as fully enfigured individuals, especially flawed but nevertheless cherished and with the ability to cherish when they managed to be fully present. Rumor has it that Madden is working on a novel (that had taken a backseat during a period of time when Madden was in mourning), and I’ll be first in line for that book!

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Sorboni Banerjee’s Hide with Me (Razorbill, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Sorboni Banerjee’s Hide with Me (Razorbill, 2018)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I didn’t reach much context for this novel before starting it, so I was perhaps more surprised than usual about what was going on. I also had just finished watching Bird Box, which was a thriller, so I suppose I was in the right mode for this kind of work. I had to make myself stop the novel because it was late, which tells me that this work, Sorboni Banerjee’s Hide with Me (Razorbill, 2018), is immensely readable.

That being said, there will no doubt be critiques of the central romance plot, but before I get into the details, let’s let B&N complete some of the set up for us, as per routine: “In the dying cornfields of his family's farm, seventeen-year-old Cade finds a girl broken and bleeding. She has one request: hide me. Tucked away in an abandoned barn on the edge of the farm, the mysterious Jane Doe starts to heal and details of her past begin to surface. A foster kid looking for a way out, Jane got caught up in the wrong crowd and barely escaped with her life. Cade has a difficult past of his own. He's been trapped in the border town of Tanner, Texas, his whole life. His dad is a drunk. His mom is gone. Money is running out. Cade is focused on one thing, a football scholarship—his only chance. Cade and Jane spend their nights in the barn planning their escapes, and their days with Cade's friends: sweet, artistic Mateo and his determined sister Jojo who vows to be president one day. But it's not that easy to disappear. Just across the border in a city in Mexico lies the life Jane desperately wants to leave behind—a past filled with drugs and danger, information she never wanted, and a cartel boss who is watching her every move. Jane Doe's past is far from over, and the secret she holds could kill them all.”

The request “hide me” is accurate to the book, so readers will immediately notice that the title differs in that major respect. The title caters to the romance plot element that is the grounding point of the narrative. The other major plot point—related to the secret involving Jane Doe and you’re getting your requisite spoiler warning here, so look away while you can—makes this young adult fiction an intriguing addition to the narconarrative. You see: Jane’s on the run from drug dealers in Mexico; her boyfriend, Raff, had been caught up in drug turf wars, and now she is guilty by association. A notorious drug dealer nicknamed the Wolf Club is looking for Jane because she might have some information about a rival’s drug smuggling tunnel, one that allows drugs to flow freely into the United States. But, this context isn’t revealed until further on in the novel. The first half is really about Jane trying to figure out what to do once she begins to heal up from some pretty serious injuries. Without any money and with only Cade and Mateo as true allies, Jane thinks that it might be better to stick around the agricultural town of Tanner until she can safe enough money to head off to Maine. At the same time, she realizes that her presence there might endanger others, so she’s constantly stressed out when a news reports suggests that there are drug-related crimes going on in the area.

The part of the narrative that I think will divide readers is the connection that Cade and Jane have for each other. Cade, for instance, obviously idealizes what he has with Jane to the point where he holds onto Jane in a way that arguably exacerbates the dangers that both characters and their friends will face. The “love at all costs” teen romance will necessarily test those readers who are a bit more logically minded and who would have obviously recommended that Jane ditch Cade and get the hell out of Tanner, as soon as she felt well enough to, but Banerjee’s work will unite all audiences in terms of its momentum. That is, despite how you might feel about the romance and the ramifications of their connection for all in the Tanner community, you will not turn away.

The other element to note is that Banerjee is able to generate such narrative propulsion through the use of clipped alternating perspectives. Chapters are short, with one usually given to us from Cade’s perspective, then the next from Jane’s. Occasionally, the narrative will break to the Wolf Cub, aka the drug cartel leader, which reminds us that someone is coming for Jane and that we’re in for an explosive conclusion!

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of R.F. Kuang’s The Poppy War (Harper Voyager, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of R.F. Kuang’s The Poppy War (Harper Voyager, 2018)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Somewhere along the way, I managed to receive an ARC of this title, which was coupled with a very unique pre-release publicity campaign. In this case, a pressed flower approximating the poppy was provided as a bookmark! In any case, this clever touch was perhaps a sign of how certain the publisher was that R.F. Kuang’s The Poppy War (Harper Voyager, 2018) would be a literary success.

On the face of its female heroine alone, Kuang’s The Poppy War is an elaborate and epic achievement, but I was still a little bit torn on this work, which takes its time and ultimately accrues a body count higher than arguably any that I’ve read in the last decade or so. Those who don’t want a little bit of horror and war thrown in with their speculative fiction should likely want to avoid this work, especially in a later sequence involving a city that is ravaged by an enemy army (called the Federation). In any case, the basic gist of this novel is the story of a young woman named Rin who achieves ascendance in the military even though she comes from a poor background. The entrance exams are not meant for someone like her, though she manages a way to scheme herself into sitting for it and actually does so well on it that she is one of the very few from her village to receive admittance into a military academy located at Sinegard. Once there, she has to take training very seriously, otherwise, she may drop out.

What this novel makes clear is that someone like her must continually jump over hurdles that others do not and that there is no safety net for her. What fuels her rise in the academy is her desperate desire not to be forced back to a life of servitude and oppression. Rin eventually shows an innate talent for a branch of military training known as Lore. A wily and eccentric leader named Jiang takes interest in her and allows her to develop shamanistic abilities that link her with the gods. In this particular novel, the poppy is absolutely vital to shamanistic training because one must be able to use the plant to get into the altered state necessary to enter into a sort of communion with the gods. Rin certainly shows an inclination to reach the gods, but it’s only ever provisional.

Later, when her shamanistic ability accidentally unfolds at a time when all hope seems lost for her and her fellow military officers, she is transferred to a different branch of the military called the Cike, which are an elite group of assassins who operate under the directive of the Empress, who is the leader under which Rin and her fellow officers are united in supporting in order to defeat the evil machinations of the Federation. I suppose I should pause to provide the requisite spoiler warning because I’ve already revealed quite a lot about the plot, so stop reading here is you don’t want to know more.

Eventually, Rin comes to realize that she’s a Speerly, which is a race of beings known for its shamanistic abilities. Most of the Speerlies were wiped out, especially as the Federation began to experiment upon them to figure out why exactly they had such peculiar, awe-inspiring abilities. But the knowledge that Rin is a Speerly also coincides with the practical devastation of the military and her allies, along with civilian cities that she must comb through in order to find what survivors may remain. It is apparent that though there is a cost to commune with the gods, Rin is willing to pay this price for vengeance. This novel leaves us at the point where Rin has given herself over to the gods in exchange for the power that they will give her. The second novel no doubt will involve Rin’s quest for revenge, as she seeks to wipe the Federation out off the map. I’m no reader of modern Chinese history, but Kuang definitely allegorized much of Chinese history for this story basing Rin’s culture and peoples upon the Chinese. Such veiled references make this work fall under the genre of silkpunk, which I believe Ken Liu coined, especially in relation to works such as his Grace of Kings series in which China is not necessarily directly mentioned but nevertheless indirectly invoked.

In the case of Kuang’s novel, the devastation wrought by the Federation is of course the metaphorical representation or the analogic depiction of the Japanese imperial enterprise. There is a sequence meant to be Kuang’s version of the Nanjing/Nanking massacre. It is as gruesome as you might expect to be, so there is a trigger warning that must be issued. That sequence is particularly dark for anyone who has any baseline knowledge of that period of time, and it makes you wonder about the political nature of speculative fiction and what we must do not to take a novel like this one purely as some mode of entertainment. In any case, Kuang’s novel comes at absolutely the right time in this golden age of Asian North American speculative fiction written by women, as this novel adds to such notable works as Peng Shepherd’s Book of M, Ling Ma’s Severance, Rachel Heng’s Suicide Club, Thea Lim’s Ocean of Minutes, among others, that show us how much there is still to read and to cherish.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Patti Kim’s I’m Ok (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Patti Kim’s I’m Ok (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2018)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Wow, it’s been a busy quarter, but I’ve managed to sneak in the occasional reading. I picked up this one because I was very excited by Patti Kim’s next publication. I remember being absolutely floored by Kim’s A Cab Called Reliable, a very slim narrative that yet packed a very big punch. I’m Ok takes a slightly different tack through its focus on middle grade readers. When I first read the title, I actually had misread it, thinking that it was something like “I’m Okay.” The cover shows someone roller skating, and the image seems to suggest that the main character has fallen. This image is perhaps why I misread it. Being of Korean background, I later quickly understood that Ok is actually the name of the protagonist. Growing up, I recall two brothers who had the last name of Ok, so there was already that kind of baseline familiarity with this surname.

In any case, B&N provides a basic scaffolding of the plot: “Ok Lee knows it’s his responsibility to help pay the bills. With his father gone and his mother working three jobs and still barely making ends meet, there’s really no other choice. If only he could win the cash prize at the school talent contest! But he can’t sing or dance, and has no magic up his sleeves, so he tries the next best thing: a hair braiding business. It’s too bad the girls at school can’t pay him much, and he’s being befriended against his will by Mickey McDonald, an unusual girl with a larger-than-life personality. Then there’s Asa Banks, the most popular boy in their grade, who’s got it out for Ok. But when the pushy deacon at their Korean church starts wooing Ok’s mom, it’s the last straw. Ok has to come up with an exit strategy—fast.”

This description does give us one of the key, intriguing details of Ok’s desire to make money: he takes advantage of a unique skill: braiding! I am reminded of the fact that, as a kid, I was absolutely enthralled by the variations I saw in braiding, so I immediately took a liking to this resourceful Ok, who would use any skill necessary to help out his mother. The problem that the novel sets up is Ok’s feelings of abandonment. His father’s death leaves not only a huge hole in his life, but also makes him wary of his mother’s growing attention to the deacon. Ok’s desire to ensure that he will be able to live a life without his mother, who seems to be drifting away from him (at least from his perception) leads him to fundraise for a tent that will allow him to live in a location that holds great personal meaning to him.

The uplifting thing about this novel is the deft way that Kim is able to develop the side characters: both Mickey and Asa turn out to be very different than how they are painted in their first scenes with Ok. In this sense, Kim grants Ok a larger berth for the community that the readers know he needs even if he himself has not yet realized it. In this way, you’re rooting for Ok to find a way out of his predicament and to reconsider his approach to all the people in his life, if only to face the possibility that there may be a brighter future than he ever expected. As I’ve read further into the children’s literature genres, I’ve been especially happy with books like this one because I don’t recall ever reading about a single Korean American character. It’s certainly a new age, and we’re lucky that Kim has contributed such a spritely addition to the growing pantheon of children’s Asian American literatures!

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Nicole Chung’s All You Can Ever Know (Catapult, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Nicole Chung’s All You Can Ever Know (Catapult, 2018)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

So, this memoir has been getting rave reviews! Here’s an example from Publishers Weekly: “In her stunning memoir, freelance writer Chung tracks the story of her own adoption, from when she was born premature and spent months on life support to the decision, while pregnant with her first child, to search for her birth family. Growing up the only person of color in an all-white family and neighborhood in a small Oregon town five hours outside of Portland, Chung felt out of place. She kept a tally of other Asians she saw but could go years without seeing anyone she didn’t recognize. She knew very little about her birth parents—only the same story she was told again and again by her adoptive parents: “Your birth parents had just moved here from Korea. They thought they wouldn’t be able to give you the life you deserved.” Decades later, Chung, with the help of a “search angel,” an intermediary who helps unite adoptive families, decided to track them down, hoping to at least get her family medical history, but what she found was a story far more complicated than she imagined. Chung’s writing is vibrant and provocative as she explores her complicated feelings about her transracial adoption (which she “loved and hated in equal measure”) and the importance of knowing where one comes from.”

Already, this review gives us enough context to know that this memoir deviates from some of the other previously published versions, which often focus on the transnational contexts that derived out of the Korean War and helped to engender decades of adoptions. In this case, Chung is adopted from a Korean immigrant family living in the United States. Though the adoption is closed, Chung eventually discovers that she can get some information about her birth family. The detail of the “search angel” provided up in the review is an interesting one because Chung does admit some level of discomfort over the intermediary that can literally profit off the adoptee’s search for her birth family.

What I appreciated about this memoir was Chung’s deft handling of the complicated family dynamics that she must navigate. By the time she has reunited with her biological sister, the complications of what happened between her biological father, mother, and her siblings makes it difficult to figure out her own path back into their lives. Fortunately, Chung’s adoptive parents are quite open to her search, which provides her enough space to find out exactly how she would like to proceed. Perhaps, the most heartwarming element of this novel is the siblinghood that she is able to develop, a trajectory that Chung makes clear she could never have predicated. It is this poignancy that truly makes this memoir so unexpectedly uplifting.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

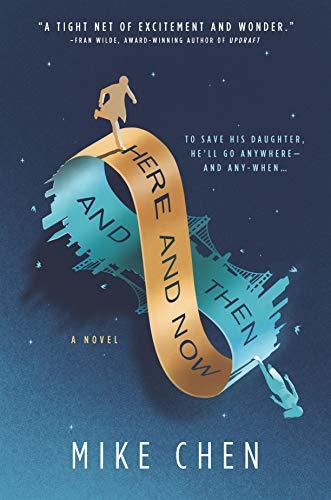

A Review of Mike Chen’s Here and Now and Then (Mira, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Mike Chen’s Here and Now and Then (Mira, 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

This title is one of my guilty pleasure reads for 2019 simply because it deploys one of my favorite narrative conceits: time travel!! As soon as I saw that there was a time travel element to this book, I picked it out and read it. I finished it in one sitting. Definitely binge-reading worthy from that perspective.

In any case, here’s B&N with some background for us: “Kin Stewart is an everyday family man: working in IT, trying to keep the spark in his marriage, struggling to connect with his teenage daughter, Miranda. But his current life is a far cry from his previous career…as a time-traveling secret agent from 2142. Stranded in suburban San Francisco since the 1990s after a botched mission, Kin has kept his past hidden from everyone around him, despite the increasing blackouts and memory loss affecting his time-traveler’s brain. Until one afternoon, his ‘rescue’ team arrives—eighteen years too late. Their mission: return Kin to 2142, where he’s only been gone weeks, not years, and where another family is waiting for him. A family he can’t remember. Torn between two lives, Kin is desperate for a way to stay connected to both. But when his best efforts threaten to destroy the agency and even history itself, his daughter’s very existence is at risk. It’ll take one final trip across time to save Miranda—even if it means breaking all the rules of time travel in the process. A uniquely emotional genre-bending debut, Here and Now and Then captures the perfect balance of heart, playfulness, and imagination, offering an intimate glimpse into the crevices of a father’s heart and its capacity to stretch across both space and time to protect the people that mean the most.”

This description does a very good job of the set up: you can see the problem. Once Kin goes “back to the future,” he attempts to integrate into his old life, but realizes that he can’t stop thinking about the wife and daughter he left beyond. The speculative dimensions of this fictional world offer Kin some useful tools: for instance, because time traveling problems have occurred in the past, there are some treatments to reverse some of the aging that Kin has experienced. Nevertheless, he’s much older than his fiancé at this point, and he begins to wonder if he even loves her anymore after what, for him, is so much time away. Here’s where I provide your requisite spoiler warning: look away now, unless you want to find out about the plot!

So, what Kin does is finds a loophole so he can communicate with his daughter back in time. When he discovers that she comes to a premature death (due in part because of what she thinks is Kin’s abandonment of her), he decides to try to communicate with her prior to that point and alter the course of her life. Though he successfully does so, he also inadvertently enables her to have the opportunity to publish materials that will later make it clear that time traveling is even possible at a far earlier point in history. This change in events makes her a temporal anomaly, one that the agency Kin works for would attempt to blot out, which means that Kin’s daughter’s life is at stake!

Though some of the elements of the novel seemed rushed (for instance, though set in SF, I got no sense of the city’s vast and diverse population at all), the conclusion does have a couple of key twists and turns that make it very satisfying. There is a moment that reminded me very much of Tuck Everlasting, one of my favorite books from when I was a kid. Here and Now and Then’s strong conclusion makes it again my favorite guilty pleasure read for 2019. Recommended for any fans of the young adult paranormal genre.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Arsenal Pulp)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Arsenal Pulp, 2018)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

So I read Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Arsenal Pulp, 2018) not long after I read two other creative nonfictional works (those were Anuradha Bhagwati’s stunning Unbecoming and T Kira Madden’s equally stunning Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls). These three works seem to resonate alongside each other in their exploration of issues related to marginalization, women’s subjectivities, and the need for strong communities that exist often beyond or beside the heteronuclear family.

Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Care Work reads as a hybrid work of memoir, essays, and academic inquiries into the conception and the deployment of carework not only for disability-based communities but also for “able” allies, for lack of better terminology. One of the most striking aspects of this collection comes from the conception of “mutual aid,” which is perhaps one foundational characteristic of “disability justice.” For people to create cohesive and lasting communities founded upon collective carework, there must be “mutual aid,” a sense that one individual does not necessarily benefit more than the other in the process of supporting someone else.

Piepzna-Samarasinha distinguishes “mutual aid” from “charity” or even something like a “gift economy,” which may presuppose some sort of power dynamic between the carer and the caree. In this case, everyone is supposed to be caring for each other in a dynamic form of equilibrium. One of the most intriguing sections of Piepzna-Samarasinha’s work appears when it explores the concept of what an ally can do to support “disability justice” paradigms and projects. One such example comes when Elisha Lim (who I know as a graphic novelist) decided to boycott any party or event that did not provide proper access for the disabled. This boycott necessarily created controversy because many institutions and organizations who needed the support of the QTBIPOC (queer trans black indigenous people of color) community stated that they could not always guarantee equal access given their limited funds and resources. But, as Piepzna-Samarasinha makes clear, such rationale ultimately fails to engage and to cultivate a stronger, more inclusive form of activism, the root of what is needed for “disability justice” to take flight not only for those who identify as within the community but also from those without. This collection also makes clear that whatever minor capital comes with marginal identities, this form of difference can be usurped and even commandeered for other causes. In this sense, Piepzna-Samarasinha’s collection makes it evident that ally-ship requires a deep vigilance that properly acknowledges the need for collective care and collective access.

From a more personal perspective, this set of essays made me think about what constitutes academic or scholarly writing. At some point, Piepzna-Samarasinha identifies her voice as one that is not necessarily academic, but I couldn’t help but thinking why not? Care Work provides a conceptual apparatus and a practical set of guidelines for understanding what disability justice is and what it can be when properly mobilized. In this sense, the work is both applicable and rigorous and certainly should be cited in the future for anyone seeking to make an intervention into disability studies, activism, and its intersections with other forms of social difference! An important, socially conscious work of deep thinking and activist praxis! As per usual, Arsenal Pulp is at the forefront of publishing innovative work from minority communities; it’s certainly one of my favorite presses out there. Piepzna-Samarasinha also shares that Care Work was rejected by numerous publishers, and it was finally Arsenal Pulp that came to the rescue. I am not surprised in the slightest that the press saw what is an essential, groundbreaking, and visionary work.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments