Elizabeth Rusch's Blog, page 35

January 10, 2013

Little Red Caboose

I’ve never been one of those writers who tuck their laptop

into their bag and then head off to a coffee shop to work every day. I’m too

attached to my ergonomically angled keyboard and the utter quiet of my office.

But every once in a while, I

need a change of scenery to get me into the right frame of mind. I need a place

that is not my office, and I need to pick up a pen.

When I’m stuck and I need to be playful—when the tone of

what I’m writing needs an element of play—sometimes it works best to leave

ergonomics and quiet behind.

I have a couple places near me that I like to work, and this

one is the most playful of all: a teahouse inside a little red caboose.

Technically, the entire teahouse is not in the caboose.

There’s a whole addition built out from the back side, with lots of tables and

chairs, a lovely outdoor courtyard, and about 50 kinds of tea. But to enter the

teahouse, you board the little red caboose. Just the idea of it makes me happy.

They also make an excellent masala chai with just the right amount of spice and

the right amount of sweet.

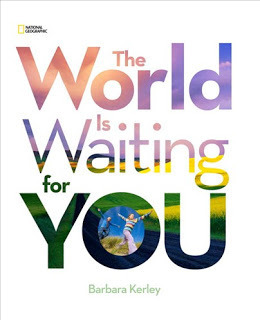

I went to the caboose last week, when I was working on a new

idea for the early concept books I do with National Geographic. The books

introduce simple ideas supported by fabulous photographs (not mine, of

course—the fabulous photographs that have made National Geographic famous.)

I’ve written about a variety of topics: water, families, peace, a day in the

life of school kids, and a new title out this spring encouraging kids to get

out and explore.

My goal with these titles is to have a clearly defined

concept expressed succinctly in an accessible tone. To express a big idea in a

kid-friendly way, with language that doesn’t take itself too seriously.

In other words, to be playful.

That kind of writing is best not done at a quiet computer.

That’s when it’s a good idea to head to a caboose.

Published on January 10, 2013 01:00

January 7, 2013

UNIMAGINABLE

Every single thing you take for granted can disappear in the

blink of an eye and be replaced by something unimaginable.

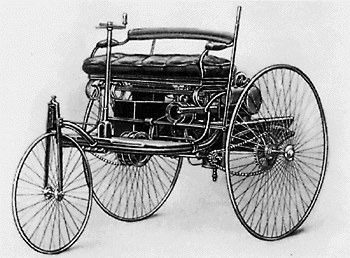

When my own grandparents were born, there were no telephones,

no refrigerators, no airplanes, and fewer than 25 automobiles on the planet. Talking

to people hundreds of miles was away was UNIMAGINABLE. Where they lived, transportation

without a horse and drinking fresh milk without a cow were unimaginable too.

By the time my parents were born, people were driving around

in Model T Fords. But everything from traffic lights, jet planes, and air

conditioners to color photography, microwave ovens, and polio vaccine was UNIMAGINABLE.

[image error]

When I was born, there was no such thing as power steering, rock

and roll, credit cards, or TV (where I lived, at least). Rockets to the moon, e-mail,

and gigantic full-color high-definition TVs with hundreds of channels were

absolutely UNIMAGINABLE.

When our kids were born, all the telephones were huge and

had a dial. There was no hint of a little cell phone you could carry to the top of Mt. Everest if you were so inclined (even though an

ancient comic strip detective named Dick Tracy used to wear a 2-way wrist radio). And what about GPS, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, iPads and blogs like this one? UNIMAGINABLE.

When my second granddaughter was born nine months ago, she

could take all of this technology for granted, and you can bet your boots that unimaginable

changes lie ahead. But let’s talk about

something else she sees every day--something that didn’t disappear and has stuck

around for centuries.

My granddaughter still owns real books; the delicious 3-D kind

filled with magic and beauty and color. Ever

since papyrus scrolls and animal skins made way for parchment and paper, countless

millions of us have loved reading books. A world without them seems UNIMAGINABLE.

[image error]

But in the blink of an eye, the unimaginable future of books

as we know them is on the march. High quality books made

out of paper are at risk; for the moment, e-books seem poised to outsell them, and

they can be sold ever so cheaply when the cost of paper, printing, binding, and glue is not

an issue.

Anything can happen. Right now, for example, digital picture book formats have to adjust to another company's tiny online display area instead of using delicious double page spreads. Otherwise the type is too small to read. Popular previously published picture books can't always manage that and will be lost. So illustrators and publishing venues will either have to find

new ways to get around the restrictions without losing quality and creativity, or the artists will have to abandon their years of work, throw in the towel, and find another way

to make a living.

Quality might suffer in other ways too. Anyone can publish a book online without being

vetted by discriminating professional editors and art directors who know the

difference between first-rate writing and junk.

Readers could drown in an overwhelming deluge of garbage. How will the cream rise to the top? And how will the professional authors and

illustrators make a living if all their hard work is sold

for pennies (assuming that their readers can even find it)?

Publishers seem to be up in the air about how to stay profitable,

and you can be sure they are considering all the options as they get steamrollered

by Amazon and bought up by conglomerates.

Professional authors and illustrators will do well to consider all of their

options too. There's always a way. And the evolving changes and surprising results will be UNIMAGINABLE.

So

carry on, watch your backs, and stay tuned.

Published on January 07, 2013 21:00

Exactly!

It’s been a while since my last I.N.K. blog posting — 675 days, or 16,192 hours, to be (too) exact. And that’s what I want to write about: meaningless precision. Also referred to as false precision or fake precision, this is a logical/mathematical fallacy that, once noticed, is encountered frequently.

Overly precise figures are often used to lend questionable data and unproven (or simply bogus) concepts an aura of credibility or scientific validity. Real scientists, as it turns out, are careful not to use figures that are more precise than their data justifies.

Examples of meaningless precision are easy to find. Sources of nutritional information are always a good bet. An online recipe (the first I looked at, in this context) called for, among other things, one small eggplant and eight slices of bread. It actually sounds pretty tasty — here’s the link: http://www.eatingwell.com/recipes/eggplant_panini.html. I learned that each serving of this dish contains 659 mg of sodium and 353 mg of potassium, quantities apparently unaffected by my definition of “small” or the thickness of my bread slices. I don’t doubt that the intentions of the recipe’s author were good, even if these figures are impossibly specific.

I’m less sanguine about a spam email I recently received informing me that I could make $12,587 a month working from home. Or the label of a homeopathic remedy for the flu known as Oscillococcinum. Starting out as a tincture of duck heart and liver (don’t ask me), this preparation has been diluted to one part duck to 10400 parts water. At this concentration, one would have to ingest a quantity of Oscillococcinum many times greater than the mass of the universe to be assured of swallowing a single molecule of that unfortunate fowl.

Pointing out this kind of absurdity isn’t particularly clever or original, but it does have something to do with writing children’s nonfiction, and I’ll get to that in a moment.

But first: normal human body temperature. It is, as most people know, 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. Except that it’s not. It’s more like 98.2. Carl Wunderlich, a 19th century physician (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Reinhold_August_Wunderlich), measured healthy body temperatures of 36.5 to 37.5 degrees Centigrade. This range was rounded, quite sensibly, to 370 C, which converts to 98.60 F. The rest is history.

This example is getting close to home, because it illustrates a problem that I confront when writing about the size of things. A recent book included a pangolin, a kind of armored anteater. Pangolins live in Africa, and according to the website of the African Wildlife Foundation (http://www.awf.org/content/wildlife/detail/pangolin) they range in length from 27 to 42 inches. I always include the metric equivalent of imperial units, since most of the rest of the world measures things metrically, and I'd like to give the U.S. a nudge, however small, in that direction. To include a range in both units makes for text that is discouragingly full of numbers — the pangolin is 27 inches to 42 inches (69 centimeters to 107 centimeters) in length — so I usually choose a figure in the middle of the range, in this case 36 inches — three feet. It’s not quite in the middle, but it does have the advantage of sounding rounded off and not too precise. The trouble arises when the metric conversion — 36 inches to 91 centimeters — is made. The metric figure is too precise. It implies that pangolins are not variable in length, but exactly 91 centimeters long. I could round off the metric units, but that would yield a too-precise imperial unit figure. Or I could write “36 inches (about 90 centimeters),” except that those “abouts” get annoying when there are dozens of creatures described. Or I could use a rounded off metric figure that would not be an accurate conversion. But, to quote Richard Nixon, that would be wrong.

I recognize that this issue doesn’t rank highly on the list of problems facing humanity. Still, it bugs me. I share it with I.N.K. readers in hopes that someone will suggest a workaround. Or maybe just to get it off my chest.

Published on January 07, 2013 00:00

January 3, 2013

Do Book-Apps Have Authors?

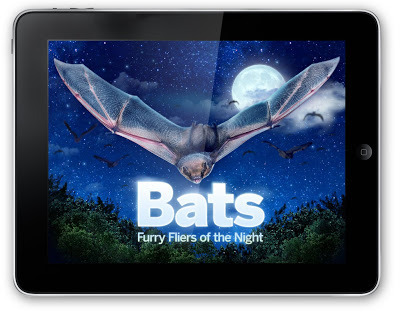

As we welcome the New Year, I've asked a former colleague to shed some light on a new medium. Mary Kay Carson was an editor on Scholastic’s science

magazines back in the early 1990s, when I was editorial director. She’s spent

much of the time since then as an independent author of more than 30 nonfiction

books about science and nature. She’s also written a book-app, which was just named a one of the finalists for the 2012 Cybils. She chronicles the process of writing that app here. Enjoy, and have a great 2013.

In the spring of 2011 a

book developer/packager that I’d previously worked for contacted me about

writing a book-app. (At that point, we were calling it an m-book, as in “multimedia-book,” as opposed to an e-book.) The book packager was starting up a new all-digital division

called Bookerella and wanted a nonfiction kids “title” for its launch. Like so many start-up

and new media ventures, payment was a promised slice of future profits. Writing

on spec is not something I can afford to do much of, so I agreed to the gig

with the stipulation that the subject be familiar, which is how the book-app

ended up featuring bats. Houghton Mifflin had recently published my Scientists

in the Field book, The Bat Scientists , so I was up on all things batty.

In truth, I had no clear idea of what the final product would be

like. I thought it might be an e-book with video, zoom-able images, and maybe a

map with pop-out labels—something like Al Gore’s Our Choice . This format

seems to me like a natural evolution of nonfiction illustration. If you’ve ever

written a book with only black-and-white photos or two-tone illustrations, you

know how constraining it can be. And even color photos still sometimes leave me

with that same old frustration of wishing that my reader could see what I

see—bats swirling up out of a cave, video of geysers on Saturn’s moon

Enceladus, the squeal of a happy rhino. Aren’t e-books or book-apps just the

next step in illustration?

Content Provider, SME, or Author?

I wrote up text for eight

spreads of basic bat info for the book-app—what bats are, what they eat, where

they live, echolocation, etc.—in a somewhat picture-bookish narrative style. (It’s nearly night. The sky is darkening.

Look up! What is flying overhead? ...) I also specked some image samples

for each spread and offered some possible multimedia ideas. From then on my hat

as a writer pretty much stayed on its hook. My role switched to SME (subject

matter expert). The designers would telephone conference and throw out ideas for

“experiences” like an interactive of echolocating bats hunting bugs with sounds

effects, and I would say science Nazi things, like: “You can’t hear ultrasonic

sounds, that’s what ultra sonic means.” This continued through reviews of

sketches and sample builds of experiences.

Whatever vague notion I’d originally had of what a book-app can be

was greatly underestimated! This one ended up with a spinning wheel that

highlighted featured bats and their foods, scenes of different habitats where

kids look for roosting bats in caves or under bridges, and other sophisticated interactive

features. Bookerella built it on an iPad-native gaming platform so it takes

advantage of the tablet’s bells and whistles. For example, the final chapter

features a bat flying high above the landscape and you get to steer the bat by

tilting the iPad, like driving in a racecar app. Once images and experiences

were finalized, I did do some caption and label writing, but my primary role

again switched—this time to fact-fixer and bat species checker.

Bats! Furry Fliers of the

Night was released in early 2012. It received some

nice reviews, garnered a

bit of acclaim, and was adapted and installed into the Memphis Zoo’s bat

exhibit. But the book-app hasn’t made a profit, and I don’t expect a check

anytime soon—if ever. Why not? I’m no expert, but people don’t like to pay for online

content and apps. It’s all free, right? Bats!

was priced at $4.99 initially, then dropped to $2.99, and is now offered for

free at iTunes in a teaser version of two chapters. Sophisticated

book-apps aren’t cheap to produce, and software developers and techies are

where most of the money goes—not writers. It’s sort of like making a movie. How

much of a multi-million dollar blockbuster’s budget goes to the scriptwriter?

Content is important, but relatively cheap in the scheme of things. What our

role as nonfiction authors, writers, and content providers is in the new media

age is evolving as the media evolve. Here’s hoping there’s a place for us!

Published on January 03, 2013 21:30

January 1, 2013

Bubbling Up Through the Slush

Happy 2013 everyone!

My New Year has started well with the promise of a multi-book

contract. With a real publishing company! One that will pay me! The past three years of

struggle and shrinkage in the publishing industry started me thinking about

books and about the digitizing of everything.

We will come out of this, but things will be different.

In

Inthe process of writing the proposal for my new series, I needed to refresh my

memory of the gas laws, some classic settled science. I first studied them many decades ago and

still have my college textbook: Foundations of Modern Physical Science by

Gerald Holton and Duane H. D. Roller, copyright 1958. It is a brilliant book that combines history

of science with breakthrough laws that define physics and chemistry. You can see that it has been well used. But I’m in today’s mode of at-your-fingertips

research, so I Googled “the gas laws”

and received a wealth of material, which I browsed through, looking for a

clear, succinct treatment. I happened

upon an ebook written by a high school chemistry teacher. It was lively, light-hearted and easy to

understand. Clearly the author

grasped the concepts and knew how to get them across. His words had “voice.” Then I read a sentence that jarred me. He was discussing carbon dioxide and

mentioned that yeast produced it. So

far, so good. Then he said that yeast

was an animal. That’s just plain

wrong! I read no further. The talented teacher/author had not had his

book vetted, or perhaps even edited.

This is not unusual for much of the fare available on the web. Hordes of

wannabe authors have embraced the new leveled digital playing field. If you can type on a computer, you can be a

published author.

Our culture has traditionally embraced published authors in

the same manner it esteems professional athletes. To be a pro means you have survived a rigorous

competitive winnowing process. For authors it involves an initial acceptance by editorial gatekeepers only to be admitted into

a new, higher-level game where their work is measured publicly by critics and

award-bestowing committees. Stories of

rejection slips chronicle every writer’s journey to the promised land of seeing

words in print. I remember when I

received the galleys (old word for “proofs”) for my first to-be-published book

after five failures. I must have stared

at the words “by Vicki Cobb” in a bold-faced Roman font for hours. It was so professional; so formally different

from the Courier typeface of my typewriter. It had a sense of permanence and

importance. It was meant to last.

(Carved in print?) And best of all, I had earned it!

Back in the day, if you wanted payment as an author, the

first hurdle was to get to an editor. It

helped to have an agent. So wannabes

sent in unsolicited manuscripts to agents and to publishers where they were

relegated to something called “the slush pile.”

Not a very encouraging title! Many

publishers hired “readers,” English

majors fresh out of college, to cut their editorial teeth by reading the slush

pile. It didn’t take long for them to

realize that most unsolicited submissions were not worth even a modicum of the

work needed to salvage something the public would buy. But every once in a while someone discovered

a diamond-in-the-rough and a best-seller actually emerged from the slush pile,

keeping alive the hopes of all the wannabes.

How has the digitization of everything changed the game? Now

everyone gets to read the slush pile! Oh,

where are the gatekeepers when you need them?

Just the other day, I was told the story of a local minister who has

just published four story-books for children through Amazon’s self-publishing

program. (Why does everyone think they

can write a children’s book? Cuz they tell

the story to their own kids, who like them?)

I politely said, “Good for him!

How are sales?” “Well, he just

started. He’s learning Facebook.” The game for today’s self-published authors is to develop an online readership, one beyond friends and family, that will

make a “real” publisher sit up and take notice.

So take, heart, publishers.

There is a role yet for you to play. Yes, you need our talent and

creativity. But we need your editorial

and design support and the rigorous vetting process you put us through, something unknown to all those digital “authors” out there. And together, we need to forge a stronger,

more inventive partnership to promote our collaborative efforts so that they bubble quickly to the surface,

well above the melting slush.

Published on January 01, 2013 21:30

December 20, 2012

YEAR-END ACCOUNTS

Person

of the year, event of the year, book of the year, movie of the year – it’s that

time again. Though my tax-woman will soon want my income/expense statements,

only I need a literary balance sheet.

A few years ago I began writing goals at the beginning of each month, printed them, and

taped them to my printer. That

scrap of paper staring at me motivated me to do what I said I

would do.

The

other day I revisited that file and saw that my last entry was September

2011, when I wrote down goals for the coming year. Measuring years from

September is a habit this student/teacher apparently hasn’t broken yet.

As

2012 nears its end, here’s my balance sheet. It illustrates the ups and downs,

twists and turns, detours and dead ends of this writer’s life.

GOALS FOR 2012, from 2011

Project

#1 – My editor wanted a revision of a picture book biography.

Progress:

I did two (or was it three?) rewrites and then she rejected the project, asking for a

new approach to the subject. My disappointment led me to ignore the

whole thing until…. a couple of days ago. I want to tackle this one in 2013.

Project

#2 – A big biographical project (over three years old now.)

Progress:

I worked on this intermittently, revising old chapters and writing a couple of

new ones. Almost ready to submit.

Projects

#3 & 4 Resurrect an old novel and a YA biography.

Progress:

Still interred.

Project

#5 Proposal for a book about rock and roll

Progress: Abandoned when I learned there was no

budget for photos and lyrics permissions.

Project

#6: Biography of a neglected female subject

Progress:

none, but I’m still interested

THE BOTTOM LINE: not as bad

as it first appears

OK,

I only worked on two of those six projects, but ….

Project

#7 My sojourn in London brought forth a new biographical subject which I

researched there, wrote at home, and submitted.

Progress:

Fingers metaphorically crossed.

Project

#8 I completed the photo research for a new edition of The Wind at Work last year (more than enough for the book.) When my

editor made the final choices *all* I had to do was get high res scans and

permissions. What I thought would be a few days’ work turned into weeks.

Progress:

DONE

Project

#9 Raise your hand if your research on one book led to another one. I thought

so. Work on project #2 (above) led to #9, a picture book biography.

Progress:

First draft completed, research ongoing.

FINAL ACCOUNT

Progress

on four projects.

Motivated

to revisit one more.

Some

possibles for next year

I’ve

got ten days left in 2012 to come up with goals for 2013. One of those will be

the revival of my monthly list of goals.

But

looking at what I did and didn’t do this year, I see some of what it takes to

keep at this writing gig.

•

openness to new opportunities

•

discipline to finish projects when inspiration might be waning

•

flexibility to reconsider everything

•

willingness to let go when the spirit – or the publisher – doesn’t feel moved

HAPPY

NEW YEAR ONE AND ALL!

Published on December 20, 2012 21:30

December 19, 2012

Humbled by Questions

I was going to write about outlining today -- a discussion of how, for me, what we teach about writing doesn’t address how I write. But this I.N.K. blog, which sometimes can seem like a chain of unrelated, individually-crafted essays, is really a conversation about writing and the world we write about. In the face of reading Cheryl Harness’ and Deborah Heiligman’s eloquent and heartfelt Monday and Tuesday blog posts about Sandy Hook Elementary School, I feel that jumping off into an entirely different area isn’t going to work for me.

Sandy Hook is five miles from my house. Just about halfway in between is Newtown’s Ferris Acres Creamery, a paradise of green meadows, cows and ice cream where I (along with the rest of the neighborhood) spend way too much time. Half the fun is the people watching -- babies and puppies and “kids with the jitters in their legs and those wide, wide open stares,” in the beautiful words of Joni Mitchell. Parents and grandparents and people on motorcycles... You get the idea, and you know where I’m going with this: what happened, happened to those people I see at the Creamery, and in the library, and at the comic book store and movie theater. While I feel unequal to the task of figuring out what to say, I know that when you’re grieving just having someone say they don’t know what to say is a balm, so consider it said.

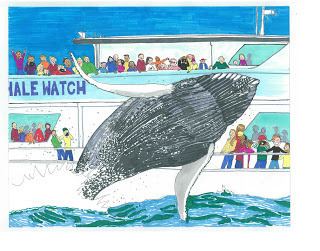

This past September, I went on a whale watch, shadowing Joanne Jarzobski, a Cape Cod high school biology teacher and naturalist. Joanne is the person at the front of the whale watch boat on the microphone who tells you whether the shadow in the water is a humpback or a finback or what. She’s the first to spot a spout or a fin or a fluke, indicates where whale watchers should look (one o’clock? five o’clock?) to get a glimpse, and is usually able to provide a whale’s identity and even a little biography, employing an internal database (as well as an external one) of identifying features.

The veteran of more than 1,600 whale watches, Joanne draws on her own experiences and those of a network of other naturalists in sharing and spreading understanding of animals that live mostly out of human view. I have a sense that she is never completely back on shore; part of Joanne is always out at sea, and her imagination takes her under the sea. When I talk to her, check her Facebook page, check a fact for the book I’m writing about her, I see that Joanne is often right about the whales -- and often surprised, too.

Even those with the most knowledge, it seems, are subject to wonderment about what is actually going. on. When I ask Joanne why a whale follows the boat or jumps out of the water or hangs around one spot in the ocean or migrates a thousand miles south, she often shrugs. Like the biologists who spend their lives studying whales, she recognizes the limits of human knowledge about whales. We may know more than we’ve ever known, but that’s still not saying much.

Yes, we know that whales’ ears -- and behavior -- appear to be affected by loud noises from ship engines and sonar booms in the sea. We know where some of the whales go over the course of the year -- but not where they all go, nor all of the reasons why they migrate. We know that different pods of orca have different feeding practices, comparable to the different ways families cook their Thanksgiving turkeys. But what scientists are seeing -- and naturalists are interpreting -- and writers and illustrators try to convey -- is only part of the story.

This isn’t what you’d call a profound or original observation on my part. Consider the proverbial tip of the iceberg that is only mildly indicative of what lies beneath. Consider the blind men who examine the elephant and extrapolate that it is, alternately, ropy like its tail or stumpy like its legs or floppy like its ears. My message gets at what the essence of science writing is for me: how complex and deep and inaccessible and humbling the world is. How continually I feel like I know nothing. How difficult it is to talk about something enormously misunderstood or under-understood. How you wind up talking about questions, not giving answers.

It’s science, but it’s also life. How many of us this week have pored over the reports from Newtown, Connecticut, trying to divine the dark mystery, the great why, the answer to the questions that seems to lie invisibly between the photographs of people crying, descriptions of the local Christmas tree lighting, quotes from the neighbor or the cousin or the friend? At the same time that we criticize the media for intruding on this stricken, grieving community, we cannot ignore and even seem to need their stories and pictures. How else can we try to understand the enormity of life, other than by the glimpses they provide?

So we writers follow people or events or ideas around, trying to explain, humbled by our subjects, obsessed with the questions, and aware that we’re not the only ones trying to answer them.

Published on December 19, 2012 03:00

December 18, 2012

If Not Now, When?

I had a different post written. About ethics in nonfiction. I'd like to publish that post some day. I'm sure I will. But not today.

Because as much as we debate and discuss what is the best way for our children to learn, the best way for us to write for children, what constitutes nonfiction, how angry it makes me when people play fast and loose with the facts, all of that is moot if unstable people are able to have easy access to guns.

What good is it to create books for children, to teach them, to care so much, if people in power are too cowardly and bull-headed, too self-interested about their own political futures and too caught up in rhetoric, to legislate wisely to protect children? To protect all of us?

I don't have the words to talk about the calamity in Newtown, CT, in a way that will make the (mostly) men in power change the laws in this country. I don't have the perfect way of describing how angry I feel about the fact that it is really difficult for many mentally ill people to get good treatment and really easy for people in most states in our nation to get guns. Guns not for hunting, or killing the odd rabid raccoon on your land, but guns for murdering people.

People I've been writing with and talking with since Friday understand legislation better than I do. They understand guns and gun laws and gerrymandering and all the reasons why there is more regulation in automobile safety (which is of course a good thing to have) than in the purchase of guns. They understand that in some states it takes a month to get a gun while in a neighboring state you can walk into Walmart and buy one. (I really like what Nicholas Kristoff had to say the other day in "Do We Have the Courage To Stop This?")

There is no reason why there should be so many guns in this country--250,000,000 plus. There is no reason why there are so many guns that are easily concealable. Guns that you don't have to reload so you can murder people in movie theaters and children coloring at their first-grade tables. There is no reason. Don't give me the right to bear arms. Don't give me the argument that you want to defend yourself. A gun in your home is more likely to kill you or someone you love than an intruder. Don't give me that.

Give me a country like most of the other civilized countries in the world where people recognize that guns kill innocent people. Give me a country where we put health and safety first, where we put love first, where we put children first. (I really like what Gail Collins had to say about finding the best in our country again in "Looking for America." )

I did a school visit in Newtown, CT, in April, 2010. Not at Sandy Hook, but at the Catholic school a mile and a half away, St. Rose of Lima. It was a good day, really nice people, though there were a couple of snafus (on my part), funny things that happened that I liked to tell people about afterwards. Now all I can think about is those kids I met, their lovely parents and teachers, and how they've been touched by unspeakable tragedy.

So many people I know are one degree away from this tragedy.

But aren't we all?

There's a Mr. Rogers quote that's been making the rounds. Have you seen it? Here it is, from this site, in case you haven't:

"When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, "Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping." To this day, especially in times of "disaster," I remember my mother's words and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers – so many caring people in this world."

Let's be those helpers, folks. Let's demand better gun legislation. Let's demand that it be REALLY HARD to get access to guns. Let's demand that the kinds of guns that are created only to murder people are BANNED. Let's demand EASY access to health care, including mental health care. Let's talk about other ways that we can make our country safe for children, for all of us. Let's work together to tell the grown-ups what children already know: guns are bad. And: grown-ups are supposed to protect children. Are supposed to be ABLE to protect children.

Let's be those people that children look at and say, Those are the helpers. Those are the caring people in the world.

If not now, when?

Because as much as we debate and discuss what is the best way for our children to learn, the best way for us to write for children, what constitutes nonfiction, how angry it makes me when people play fast and loose with the facts, all of that is moot if unstable people are able to have easy access to guns.

What good is it to create books for children, to teach them, to care so much, if people in power are too cowardly and bull-headed, too self-interested about their own political futures and too caught up in rhetoric, to legislate wisely to protect children? To protect all of us?

I don't have the words to talk about the calamity in Newtown, CT, in a way that will make the (mostly) men in power change the laws in this country. I don't have the perfect way of describing how angry I feel about the fact that it is really difficult for many mentally ill people to get good treatment and really easy for people in most states in our nation to get guns. Guns not for hunting, or killing the odd rabid raccoon on your land, but guns for murdering people.

People I've been writing with and talking with since Friday understand legislation better than I do. They understand guns and gun laws and gerrymandering and all the reasons why there is more regulation in automobile safety (which is of course a good thing to have) than in the purchase of guns. They understand that in some states it takes a month to get a gun while in a neighboring state you can walk into Walmart and buy one. (I really like what Nicholas Kristoff had to say the other day in "Do We Have the Courage To Stop This?")

There is no reason why there should be so many guns in this country--250,000,000 plus. There is no reason why there are so many guns that are easily concealable. Guns that you don't have to reload so you can murder people in movie theaters and children coloring at their first-grade tables. There is no reason. Don't give me the right to bear arms. Don't give me the argument that you want to defend yourself. A gun in your home is more likely to kill you or someone you love than an intruder. Don't give me that.

Give me a country like most of the other civilized countries in the world where people recognize that guns kill innocent people. Give me a country where we put health and safety first, where we put love first, where we put children first. (I really like what Gail Collins had to say about finding the best in our country again in "Looking for America." )

I did a school visit in Newtown, CT, in April, 2010. Not at Sandy Hook, but at the Catholic school a mile and a half away, St. Rose of Lima. It was a good day, really nice people, though there were a couple of snafus (on my part), funny things that happened that I liked to tell people about afterwards. Now all I can think about is those kids I met, their lovely parents and teachers, and how they've been touched by unspeakable tragedy.

So many people I know are one degree away from this tragedy.

But aren't we all?

There's a Mr. Rogers quote that's been making the rounds. Have you seen it? Here it is, from this site, in case you haven't:

"When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, "Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping." To this day, especially in times of "disaster," I remember my mother's words and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers – so many caring people in this world."

Let's be those helpers, folks. Let's demand better gun legislation. Let's demand that it be REALLY HARD to get access to guns. Let's demand that the kinds of guns that are created only to murder people are BANNED. Let's demand EASY access to health care, including mental health care. Let's talk about other ways that we can make our country safe for children, for all of us. Let's work together to tell the grown-ups what children already know: guns are bad. And: grown-ups are supposed to protect children. Are supposed to be ABLE to protect children.

Let's be those people that children look at and say, Those are the helpers. Those are the caring people in the world.

If not now, when?

Published on December 18, 2012 01:30

December 17, 2012

Patch, patch, patch.

So, those of you who happen to be friends of mine, Facebook-wise, know that I post the words of any notable someone who'd chanced to have been been born that day in history. It gives me the chance to find out a bit about one of my fellow humans who entered the world's stage on, perhaps, a day like today - and, as a bonus, some insight or heartening quip to copy down in my little book, the existence of which, along with its fellows will probably inspire some lifting of eyebrows among those who'll go through my belongings someday after I get my ticket punched. ['Man oh man, Aunt Cheryl needed to get out more.'] For the record, the chemist Humphry Davy was born in Cornwall, on the 17th of December, 1778. He, most notably, appears to have detected the felicitous effects of nitrous oxide, a.k.a. laughing gas. Anyway, what did Humphry have to say? For one thing: "The most important of my discoveries have been suggested to me by my failures."

Humphry Davy -

cool cravat, no?

The thing is, this past Saturday, while listening to the dreadful, unfolding news from Connecticut, about a man-boy who sought to right the wrongs of his life by ending it, along with those of his mother and, as a demented bonus, little children, all gaga with the holiday season, and those who spent their days teaching and guiding them, I came across these words of playwright, Maxwell Anderson, born 15 Dec. 1888 – one of his works was adapting a novel into the play > wonderfully creepy 1956 film, The Bad Seed - how's that for appropriate? How is it that that quiet child was, in fact, a heartless killer, sans conscience and empathy? – but I digress. As a matter of fact, I could use some laughing gas right about now.... Maxwell Anderson: "If you practice an art, be proud of it and make it proud of you. It may break your heart, but it will fill your heart before it breaks it. It will make you a person in your own right."

And that long-gone playwright's words got me to thinking about the art we practice, that of examining, delving into real events, real people, and explaining them. Illuminating them. The proper pride we feel, at times, in getting to do this for a living. In knowing that kids will find, in our books, a little more about their world, about the people who have gone before.

And how is it that we could make our art proud of us? By making certain that we're reporting the facts. The genuine words and actions. By writing, showing, telling about them in a way that is juicy and engaging. Heck, by pulling back the curtain and revealing a STORY that's cool, vivid, and real. Suspenseful. On which lives and nations hung in the balance.

But then, how can this art of nonfiction break our hearts? Oh, that's easy: Finding a life, a chapter in the life of the world, with which or with whom you've fallen in love, for which no skittish editor is willing to gamble. 'No, too obscure.' 'No, I can't quite wrap my head around this concept.' 'No, I couldn't convince the marketing people. How about....?'

But look at what this person DID!

But look at how amazing this person, this time, this event was!

But look at what could have happened!

But, in the end, look what and/or who we learned. And in doing so, our lives were enriched, in the ever-onward bumble towards a book that would sell, that would, that might give us another season of employment. And there it is: that which makes us people in our own right. The learning. The discovering that fills our patched-up human hearts, in this here vale of tears.

Published on December 17, 2012 05:00

December 14, 2012

Cover Story

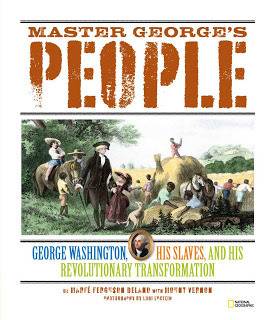

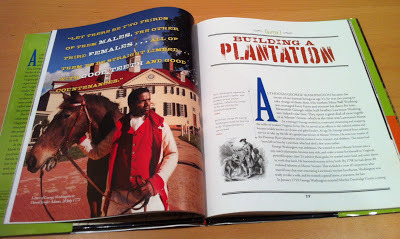

It was nearly five years from proposal to publication, but now I'm finally holding Master George's People in my hot little hands. To say I'm pleased with how it turned out is an understatement—I'm over the moon! Lori Epstein's stunning photographs are a big reason why. So is the beautiful, powerful design created by National Geographic's Jim Hiscott. Both were true collaborators on this project. Back in June, I wrote in INK about our photo shoot with Lori at Mount Vernon, George Washington's Virginia plantation. Today I asked Jim if he would share with us his process of designing the book.

What look and feel were you striving for with the cover?

Jim: The initial design construct, at least in regard to the typography, came from the idea of broadsides used for the search and capture of runaway slaves, utilizing a blocky and distressed typography. In fact in the title, "Master George's People," there are two different styles that work in concert with each other, one an extended serif font and the other a condensed stencil style. The counterpoint to this is the use of a more elegant and refined condensed serif display font for the subtitle and the large cap indents that launch each chapter. The use of the distressed rules on the cover and the interior was another reference to newspapers and a graphic approach of the period.

How about the inside of the book? The little decorative doodads at the end of the picture captions have a colonial feel to me. Were you aiming to create a sense of period with this and other design elements?

Jim: The overall design tenet I always use, no matter the style, is to create contrasts between things, elements, no matter what they may be, as a way to create energy, impact, and tension. For this book I wanted to reflect the contrast between these two worlds—that of George Washington and the refined manners of the day compared to the life of slaves. Hard/soft if you will. And by using color on the cover as well as on the inside, it was a way to be respectful of the NGKids brand while also trying to create a look that was respectful of two periods of time—present day and the Colonial period. This all helped to give the book a certain dynamic that allowed me to present it in a strong, elegant, and sophisticated manner that hopefully feels contemporary as well.

What were the challenges of designing a book illustrated with so many different kinds of images, from archival illustrations to historical documents to reenactment photography? (By the way, the photo above was taken by yours truly and does NOT do justice to the real thing.)

Jim: I know this kind of thing always causes some trepidation from the editorial side of a project. However, I look at having to rely on a diversity of visual images/styles to flesh out a visual story as an asset. Given the challenges of finding images to represent different points of the story, to me, only makes it visually richer, especially when they are framed with the use of photography of reenactments. When you speak of HISTORY many people aren't going to think of it as very interesting. I want to try to create a visual package that helps make the book engaging on one level so it is appealing for the reader to then get absorbed into the story. It also helps to have a captivating manuscript.

Why thank you, Jim. Is there anything else you'd like to share about designing Master George's People?

Jim: I loved working on this book. It was a true pleasure to be able to try and package it in a way that was respectful of the period and the story, while trying to make it visually appealing to today's readers, and to create a sophisticated book that kids would want to read, as if something really special had been created especially for them. Yes, it is a very serious topic, but that doesn't mean it can't be presented in an attractive and sophisticated way that is clean, fresh, and hopefully not so trendy as to become dated. You want a design that has as long a shelf life as possible.

Many thanks to Jim for giving us a glimpse into his creative process. And my personal thanks to him for helping me tell the story of George Washington and the people he held in bondage.

Left to right: Jennifer Emmett (my wonderful editor), me, Jim Hiscott (art director and designer) and Hillary Moloney (illustrations assistant) at Mount Vernon. Missing is photographer Lori Epstein. She's behind the lens!

Published on December 14, 2012 01:00