Elizabeth Rusch's Blog, page 33

February 12, 2013

The Man

I was eight years old, it was 11:30 at night, and I was in bed spinning the radio dial trying to find a talk show. Radio talk shows were always lively and fun, extended bits of lighthearted talk with some music tossed in here and there, accompanied by the happy background clink of cocktail glasses. But instead of clever chatter I found a baseball game.

*

This caught my attention. It was late and the local teams (the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers) had all finished their games. This radio broadcast must be coming from someplace way out west, I thought. Like Pittsburg. Or maybe even Chicago.

*

The first thing I remember the announcer saying was: "...he's digging into the left side of the plate and settles into his familiar corkscrew batting stance...."

*

A corkscrew batting stance? Odd. I knew about strange batting stances, by the way. My friend, Bobby, from across the street, would choke up on the bat, then hunch over and lay the fat end of his bat on the dirt behind him in the batter's box. He wouldn't lift up the bat until the ball was sailing toward him. His way of hitting made me nervous, but, miraculously, he always seemed to make contact.

*

But this corkscrew stance? In professional baseball?

*

As I tried to picture this weird stance in my head, my father poked his head in my room and asked what I was listening to, so I told him about this batter's (I hadn't heard his name announced) weird stance. "That's probably Stan Musial," he said. "He's with the Cardinals and he's a very good baseball player." He was about to head downstairs to read his newspaper, when he turned to say something else. Now, it's important to know that my Dad was a diehard Yankee fan who could rattle off the names and stats of every Yankee great. Every so often he might drop in a nice mention of a Giant (Willie Mays, especially) or of a couple of Dodgers. But for him the Yankees were where baseball royalty ruled supreme. So it got my attention when he added, "Musial is one of the greatest players in baseball history. He's so good a hitter that he's known as 'The Man.' Stan 'The Man' Musial."

*

As my Dad went downstairs there was a distant cheer from my little plastic radio as Stan Musial rapped a pitch into right field for a double that scored a run. A perfectly timed moment in my life.

*

The next morning at breakfast I told my parents about the game and how this guy Stan Musial seemed to have won it single-handedly, with two hits and several great fielding plays. I said I wanted to know more about him.

*

Getting more information wasn't easy way back then. No internet connection to Amazon or Barnes & Noble; no finger tip computer buying of used books or magazines or whatever. But by the end of the day my Mom had managed to find a book about Musial (at the library) and my Dad came home with a magazine that had an article about him. Both with photographs that included his famous corkscrew batting stance. And his smile. He seemed like a thoroughly nice guy from what I read and the photos I studied. I was completely mesmerized by Musial, a non-Yankee and on top of that a National league player for the St. Louis Cardinals.

*

St. Louis? I looked up where St. Louis was. Then I read about the Cardinals, their history and who else was on the team with Musial. I even bagan to appreciate cardinals (the birds) and found some glorious colored pictures of them. In the weeks to follow my parents found other books and articles about Musial, all of which I gobbled up. Then I started reading about other great players of the time (Ted Williams and Willie Mays, for example) and even read the official major league baseball rule book. Don't ask me why because I don't remember wanting to read it, just that when it appeared on the kitchen table I grabbed it and read it cover to cover. I was probably the only eight-year-old who could get into a screaming argument over a disputed sandlot baseball play and cite and explain rules between cusses, comments on the other kids vision problems, and other insults.

*

Stan Musial's recent death had me thinking about this unusual (for me at the time) quest for information that clearly boardered on the obsessive. From Musial, to his baseball team and teammates, to a city and then on to other players and hundreds and hundreds of arcane rules. And birds! It was like a weed growing and expanding and taking up more and more terrain (in my mind, at least).

*

This began as a desire to know more about one of baseball's greatest ever players. But then I found myself hooked by the gathering of details and the way it shaped and informed my understanding of Musial and baseball. The more I learned the better I felt I knew Stan Musial.

*

The funny thing is that I now do research for my projects in much the same way. I begin with a topic that interests me and then start reading about it. I constantly ask myself if any readers -- kids who probably don't know much about whatever the subject is -- will be interested enough to pick up and read the book. The research monster grows and grows, taking up months and years of time, and often wandering off into lands that don't have much to do with the focus of the project. If I get bored with the project, I assume my readers will, too, and I give it up (something that, sigh, has happened all too frequently). But in most cases I press on with the research until I can 'see' the time and people and situations in my mind and, hopefully, will be able to transcribe these images onto the page so that readers can experience history as if they were actually there. And maybe be curious enough to carry on their own search for more information.

*

Stan Musial was 'The Man' who led me down this research path. When I heard that he had died I took a baseball from a dusty office shelf and put it on my desk. It was signed by Stan Musial in a steady, sure hand with "H of F 69" proudly written underneath It's the only autographed ball I have. I never met Stan Musial in person, but for some reason I feel as if I knew him very well.

*

This caught my attention. It was late and the local teams (the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers) had all finished their games. This radio broadcast must be coming from someplace way out west, I thought. Like Pittsburg. Or maybe even Chicago.

*

The first thing I remember the announcer saying was: "...he's digging into the left side of the plate and settles into his familiar corkscrew batting stance...."

*

A corkscrew batting stance? Odd. I knew about strange batting stances, by the way. My friend, Bobby, from across the street, would choke up on the bat, then hunch over and lay the fat end of his bat on the dirt behind him in the batter's box. He wouldn't lift up the bat until the ball was sailing toward him. His way of hitting made me nervous, but, miraculously, he always seemed to make contact.

*

But this corkscrew stance? In professional baseball?

*

As I tried to picture this weird stance in my head, my father poked his head in my room and asked what I was listening to, so I told him about this batter's (I hadn't heard his name announced) weird stance. "That's probably Stan Musial," he said. "He's with the Cardinals and he's a very good baseball player." He was about to head downstairs to read his newspaper, when he turned to say something else. Now, it's important to know that my Dad was a diehard Yankee fan who could rattle off the names and stats of every Yankee great. Every so often he might drop in a nice mention of a Giant (Willie Mays, especially) or of a couple of Dodgers. But for him the Yankees were where baseball royalty ruled supreme. So it got my attention when he added, "Musial is one of the greatest players in baseball history. He's so good a hitter that he's known as 'The Man.' Stan 'The Man' Musial."

*

As my Dad went downstairs there was a distant cheer from my little plastic radio as Stan Musial rapped a pitch into right field for a double that scored a run. A perfectly timed moment in my life.

*

The next morning at breakfast I told my parents about the game and how this guy Stan Musial seemed to have won it single-handedly, with two hits and several great fielding plays. I said I wanted to know more about him.

*

Getting more information wasn't easy way back then. No internet connection to Amazon or Barnes & Noble; no finger tip computer buying of used books or magazines or whatever. But by the end of the day my Mom had managed to find a book about Musial (at the library) and my Dad came home with a magazine that had an article about him. Both with photographs that included his famous corkscrew batting stance. And his smile. He seemed like a thoroughly nice guy from what I read and the photos I studied. I was completely mesmerized by Musial, a non-Yankee and on top of that a National league player for the St. Louis Cardinals.

*

St. Louis? I looked up where St. Louis was. Then I read about the Cardinals, their history and who else was on the team with Musial. I even bagan to appreciate cardinals (the birds) and found some glorious colored pictures of them. In the weeks to follow my parents found other books and articles about Musial, all of which I gobbled up. Then I started reading about other great players of the time (Ted Williams and Willie Mays, for example) and even read the official major league baseball rule book. Don't ask me why because I don't remember wanting to read it, just that when it appeared on the kitchen table I grabbed it and read it cover to cover. I was probably the only eight-year-old who could get into a screaming argument over a disputed sandlot baseball play and cite and explain rules between cusses, comments on the other kids vision problems, and other insults.

*

Stan Musial's recent death had me thinking about this unusual (for me at the time) quest for information that clearly boardered on the obsessive. From Musial, to his baseball team and teammates, to a city and then on to other players and hundreds and hundreds of arcane rules. And birds! It was like a weed growing and expanding and taking up more and more terrain (in my mind, at least).

*

This began as a desire to know more about one of baseball's greatest ever players. But then I found myself hooked by the gathering of details and the way it shaped and informed my understanding of Musial and baseball. The more I learned the better I felt I knew Stan Musial.

*

The funny thing is that I now do research for my projects in much the same way. I begin with a topic that interests me and then start reading about it. I constantly ask myself if any readers -- kids who probably don't know much about whatever the subject is -- will be interested enough to pick up and read the book. The research monster grows and grows, taking up months and years of time, and often wandering off into lands that don't have much to do with the focus of the project. If I get bored with the project, I assume my readers will, too, and I give it up (something that, sigh, has happened all too frequently). But in most cases I press on with the research until I can 'see' the time and people and situations in my mind and, hopefully, will be able to transcribe these images onto the page so that readers can experience history as if they were actually there. And maybe be curious enough to carry on their own search for more information.

*

Stan Musial was 'The Man' who led me down this research path. When I heard that he had died I took a baseball from a dusty office shelf and put it on my desk. It was signed by Stan Musial in a steady, sure hand with "H of F 69" proudly written underneath It's the only autographed ball I have. I never met Stan Musial in person, but for some reason I feel as if I knew him very well.

Published on February 12, 2013 00:30

February 11, 2013

Common Ground, Common Core

In 2004, my book Skyscraper was published. In 2010, it went out of print. I wrote a post about it, Skyscraper RIP, a eulogy for a book that was well received, but really because I loved the experience of researching and writing it.

In 2004, my book Skyscraper was published. In 2010, it went out of print. I wrote a post about it, Skyscraper RIP, a eulogy for a book that was well received, but really because I loved the experience of researching and writing it.Lazarus, you aren't the only one. I'm happy to say that Skyscraper is alive once more, in some classrooms at least. The story of its resurrection, however, is also the story of how some publishers and school systems will be handling Common Core.

Scholastic has published a series called Math Reads. Marilyn Burns, whose resume in teaching and designing math curricula seems impressive, headed a team of other teachers to create it. Here is a description of their product:

Math Reads is the NEW math and literature program from

Marilyn Burns. Designed to support the Common Core State Standards for

K–5, each grade-level collection of books brings math alive and serves

as a springboard for math instruction.

Each grade-level Math Reads program includes:

25 children’s literature titles (5 copies of each)

Lessons written by Marilyn Burns and Math Solutions authors

eBooks of select titles for interactive whiteboards

Math Solutions’ Math and Literature professional development book

If you look at the curriculum for Math Reads' 5th grade, you'll see Skyscraper has been included and is in some very good company, including Hottest, Coldest, Highest, Deepest by my I.N.K. colleague Steve Jenkins, Pennies for Elephants by a friend Lita Judge, Wilma Unlimited by the always good Kathleen Krull, and Mordicai Gerstein's The Man Who Walked Between the Towers, an extraordinary book I've blogged about before.

So this Math Reads series contains good fiction and nonfiction books (although only 5 copies of each per classroom), additional titles in eBook format, and lesson plans to use all these books to satisfy Common Core. Hopefully, teachers and students will be exposed to good literature they might not have ever seen. Hopefully it will spur a greater interest in reading as well as a better understanding of math. It will help overworked teachers adapt to the demands of Common Core quickly and, again hopefully, once they get their bearings, they will feel confident to use their own ideas and own favorite books to enrich their teaching. These are possible positive outcomes of this series--along with good profits for Scholastic.

It also seems to be a model we will see more and more as publishing and education fulfill both the needs and opportunities that Common Core has created in terms of nonfiction in the classroom. I'm not advocating for this model, I mentioned it to start a discussion of what other models and reactions we'll see. What we think about them. What we realistically hope to see. What we think are practical and will work.

What do you all think? I'm particularly interested in what all the teachers, librarians and other educators who read our blog have to say about the matter.

Published on February 11, 2013 02:00

February 5, 2013

Taking Note of Note-Taking

Ever notice people who scribble

constantly while attending a talk? I do

because I don’t take notes well. In fact, I hardly take notes at all. I find

note-taking gets in the way of attentive listening. I’m afraid I’ll miss something if I divert my

attention to writing something

down. Note-taking is a different activity than

actively listening. So when I interview an expert to learn about

his/her field for a project I’m working on, I bring along a tape recorder. The only notes I take are about specifics—the

spelling of a name, or a particular recommended reading, or a website I should

visit. Later, when I am synthesizing

material in my own writing, I can

always double check my memory about what I heard with the tape recorder. I have come to understand that my memory is

quite good. And, as a result, I’ve come to rely on it. If I’m worried about forgetting some of the

details after listening all day, I

write my notes in the evening.

It seems that Socrates also noticed this. He worried about the technology of his day,

the stylus, which allowed people to write in clay. He was afraid that “[Writing] destroys memory [and]

weakens the mind, relieving it of…work that makes it strong. [It] is an inhuman

thing.” In other words, if you could easily make notes (now carved in clay),

you no longer had to remember what you wrote down and so you could now forget

it. Listening

and writing are two different and,

perhaps, competing verbal activities. Modern research into multitasking indicates that we really

don’t do two or more things at once, but simply shift attention back and forth

from different tasks. But in college, we were all encouraged to take notes, not

only from lectures but from our readings as well.

For my first term paper when I was in

college, I learned from a graduate student that 3”x 5” note cards about the research were the order of the day and I

diligently wrote them. But, today, when

I’m reading to learn, I find it

disruptive to write notes. That’s why I

found Deb Heiligman’s post A Modest Proposal (for Doing Research with Kids)

from three years ago so memorable. When I’m

trying to grasp concepts the best way for me to learn is to read several different sources on the

same subject. It is only when you can articulate a concept in your own words

that you truly “own” it. So I also use Deb’s technique of only making a note

when something jumps out at me and I know that I’ll want to revisit it.

But doesn’t the act of writing also strengthen memory? The many times I forget to bring along the

grocery list I had recently created makes no difference at all in collecting every

item on that list into my shopping basket.

We authors are verbally articulate about the material in our books

because we’ve thought about it and written about it and, as a result, remember

it better. The many pundits who speak so well on news talk shows are

all excellent writers. Good speaking comes from having written and

practicing by engaging in substantive conversations.

The Common Core State Standards “…..require

that students systematically acquire knowledge in literature and other

disciplines through reading, writing,

speaking, and listening.” To become an articulate, educated person

requires interaction of all four of these activities, which I’ve bold-faced in

this post. I’m not sure where note-taking fits into this process. I have a hunch that it’s one of those highly

individualized quirks that everyone has to discover independently. In

other words, we each have to figure out what works best in our personal

acquisition of knowledge. This could be

a sub-text of the CCSS. Although becoming educated involves all four activities,

how you make it work for yourself can

be discovered only empirically. There is

no one right way, one size fits all. It

is this process of self-discovery that needs to be communicated to teachers and

students.

Published on February 05, 2013 21:30

February 4, 2013

MAKING HISTORY BOOKS THAT SHINE

I write a lot of books

about history because history’s cup runneth over with the best stories of all

time. So with an ocean of great tales to

choose from, picking something fabulous and delicious and unusual should be as easy

as pie, right? Well, guess what. It ain’t. Why not?

Some Restrictions Apply.

Restriction # 1:

Since publishers want to make a buck, they strongly

encourage children’s nonfiction authors to write about famous heroes and events

from American history, especially when these topics are covered in the school curriculum. That’s because the vast majority of

nonfiction books for kids are sold to schools. The heroes and events in history

books have already been covered a gazillion times, but (in my experience, at

least) whenever we authors suggest new topics that are off the beaten path, our

publishers Just Say No and we have to file for unemployment.

Possible solution that keeps us in

business and (we hope) keeps us from selling our souls at the same time:

Uncover something

entirely new about the same old same old.

Do we have to focus only upon

heroes and heroines? Who says that all

stories from history have to be uplifting?

They are not. So sometimes I cover

a period in history by sidetracking the good guys and writing about the bad guys

instead. (Surprise—kids actually love

that.) Sometimes I focus on just one

small part of a famous person’s story, especially if it has been overlooked. Sometimes--lots of times, actually--I use humor. Sometimes

I tell both sides of a story. And sometimes I tell the entire story via my artwork

or use the art to set a mood in ways that words alone can never do.

Restriction # 2:

In nonfiction, you can never EVER embellish the truth or

make anything up, so every single detail in every single book has to be accurate and

every single word your protagonists utter has to come straight from the horse’s

mouth. Them’s the rules, period. The problem is that this is a hard row to

hoe. It can take months or even years to ferret out the accurate material.

Possible Solution

that speeds up all that research and helps us retain our sanity:

Guess what. There is

no solution. I have written books of fiction

in two weeks or less, and they have sold as many or more copies than my nonfiction

books. You just have to love being the

detective who ferrets out the juicy details nobody else has found. You just have to get a kick out of traveling

around the world to find new material. You

just have to be the spy who gets a kick out of reading dead people’s private

letters and diaries. You just have to be a glutton for punishment. I highly recommend it.

Published on February 04, 2013 21:00

The End of the World

I’ve been reading — rereading, actually — Our Final Hour, a fascinating and depressing little book by Sir Martin Rees, a cosmologist and the British Astronomer Royal. The subtitle, A Scientist’s Warning: How Terror, Error, and Environmental Disaster Threaten Humankind’s Future in This Century on Earth and Beyond, pretty much says it all.

Rees believes that civilization has no more than a 50-50 chance of making it through this century, and he gives those who are so inclined an impressive list of things to obsess about. There are the usual suspects: nuclear war, asteroid impact, nearby supernova, massive volcanic eruption, pandemic, nanotechnology run amok, and evil computers. There’s also the highly unlikely but disheartening possibility that physicists fooling around with subatomic particles and high energies might accidentally unravel space-time itself. The upside of this particular scenario is that the destruction would propagate at the speed of light, so there wouldn’t be much time for regrets.

I don’t think I’m the only one intrigued by this sort of thing. The book was published, after all, and it’s just one title in what might be thought of as the apocalyptic non-fiction genre. These books are written for an adult audience, which raises a question: where are the dystopian non-fiction books for children?

In The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales , Bruno Bettelheim makes a convincing case for the therapeutic value of those gruesome Grimm Brother’s stories. The witches, evil stepmothers and monsters give young children a vehicle for acknowledging and externalizing their own dark impulses — feelings that they are just becoming aware of. Older children are certainly exposed to many of the catastrophic possibilities that Rees discusses, which might help to explain the popularity of YA dystopian fiction, much of which is as dark as any real-life scenario we could imagine. Personally, I would have appreciated some factual and unpatronizing information about the consequences of all-out nuclear war back in the duck-and-cover days, when we were advised to turn away from the windows and get under our desks when we saw the flash.

It’s interesting that children’s non-fiction doesn’t shy away from dreadful episodes in the past — plagues, wars, natural disasters and genocides get plenty of attention. Unless there are titles I’m overlooking (a definite possibility), I don’t see children’s non-fiction that speculates about really bad scenarios in the future. I did come across a frightening volume titled A Kid’s Guide to Understanding the End Times, by the authors of the Left Behind series, but I don’t think it qualifies as non-fiction (no link for this one — you’ll have to dig it up on your own). There are plenty of books that deal with serious social and environmental issues that lie ahead, but their tone tends towards “here’s what you can do to help fight global warming.” I don’t have anything against optimism and positive action, but if that asteroid we failed to detect does hit (giving us, Rees says, about three seconds warning), recycling won’t make much of a difference.

I’m speculating that it is reluctance on the part of the adult gatekeepers rather than a lack of interest on the part of young readers that explains the absence of these books. It makes a certain amount of sense — we are more comfortable learning about terrible things in the past, because the fact that we’re reading about them means we probably weren’t directly affected.

Now, here’s a segue I could only get away with in a blog (i.e., with no editor to point out what a stretch it is). I’ve been playing with a concept about what life might look like at some point in the distant future, and it’s occurred to me that — like attitudes toward Armageddon — opinions about evolution are not symmetrical with regard to time. (I couldn’t write a blog without some reference to this subject. Sort of like Gail Collins and that dog strapped to the roof, at least until last November). I have no real evidence for this observation, but here it is: if asked whether at least some living things might change over time and be different in the distant future, I think many of the 40-odd percent of Americans who deny that anything has evolved to this point would accept the premise. If it’s true, it offers the possibility of presenting an important scientific concept without the fear and loathing the subject normally inspires. Unless, of course, that asteroid makes the whole subject moot.

Published on February 04, 2013 01:00

January 31, 2013

A Day in the Life

Where did the time go? I wrote my first I.N.K. blog post five years ago this month. That makes this one of the steadiest jobs I've ever had. But what do I do with my time? In an effort to record some semblance of an answer for posterity, I present a chronicle of one recent day.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

8:20 a.m.:

Alarm goes off. Today is a sleep-in day. I usually get up about 7 a.m. to go to

the gym, but on Wednesdays I like to sleep late. I inadvertently sleep extra late

when I roll over and doze again.

9:00:

Finally get up. Feed the cats. Put on my computer.

9:15: Read

e-mails, Twitter, Facebook, I.N.K. (Nice post, Marfe.)

9:40: Go

over revised book contract for my biography of Sally Ride. We’ve been working

on this for three months (the contract, not the book), and it’s almost there.

E-mail my attorney with a few points that still need to be fixed.

9:55:

Breakfast (pineapple yogurt and iced tea), shower.

10:30:

Surprise! The morning mail has brought a jury duty notice. True to form,

they’ve scheduled my jury duty for the week I’ll be in California doing school

visits. Fortunately, my county makes it easy to request a postponement. I go to

their Web site and fill out the form.

10:45:

Skim books on tennis history for information on Alice Marble, the 1930s

champion who at one time taught the game to Sally Ride. I’ve had these books

for decades and feel a tug of nostalgia as I turn to the index and flip pages,

rather than typing words into search engines.

11:30:

Head to Staples to do some careful photocopying of archival Roller Derby

programs that I borrowed from the proprietor of the National Roller Derby Hall of Fame. No, Sally Ride never skated Roller Derby. This is for a picture book.

While I’m out, I decide to give myself a treat and buy a six-inch Subway

sandwich for lunch. I resist the urge to measure it to see if it really is six

inches long. (If you don’t get that reference, see here.)

12:15 p.m.:

Arrive home with my sandwich to find an e-mail with a revised contract. Check

it and find that a few changes still need to be made. E-mail my attorney.

12:45: Eat

lunch, watch a rerun of Flashpoint to

clear my head. Mourn the fact that this fine Canadian import ended its

first-run shows last week. Wash dishes. Clean litter box.

2:00:

Check e-mail and find that my book contract has been revised to perfection.

Hallelujah! Print out four copies and sign them. Then realize I’m not sure

whether to mail the package to my editor or the publisher’s attorney. Write e-mails.

Get answer. Address it to the attorney.

2:45:

Check the AT&T Archives Web site to see if they have posted any of the

archival films with bonus intros that I wrote last summer. And they have: War and the Telephone . I watch the

wonderful George Kupczak deliver the lines that I wrote about the operators who

ran AT&T’s World War II telephone centers at shipyards and military bases.

It’s my first filmed script.

3:00:

FINALLY start writing. Alice Marble, Sally Ride, tennis. Great stuff.

6:15: Feed

the cats. Make dinner (a Mexican concoction with cornbread, cheese, chorizos,

salsa, and guacamole). Check in on Brian Williams. Listen to him talk about

high winds and heavy rain that are approaching the Northeast. Decide to make

extra ice cubes, power up my cell phone, and save my work-in-progress on a

flash drive in case the electricity goes out. Wash dishes and clean the

litter box.

8:00:

Start this blog. Wish I could report that I did more actual writing today,

but this is nonfiction and I can't make things up. I did stay up till 12:30 last night working on my manuscript,

since I knew I could sleep late. When there's a deadline on the horizon, one day pretty much blends into the next.

9:00: Time

for a dose of Law & Order: SVU

and Top Chef. Crime. Competition.

Food. An excellent end to a writer’s day.

Published on January 31, 2013 21:30

Why Backmatter Matters

Recently Sandra Jordan I finished a non-fiction book The Mad Potter: George E. Ohr Eccentric Genius to be published in September, 2013. It is the story of an American maverick, an artist/ceramicist, whose body of work was hidden away in crates on his sons’ property in Biloxi, Mississippi, until he was rediscovered fifty years after his death in 1918. When we attended the ALA conference several years ago in New Orleans, we decided to visit the rebuilt Ohr-O’Keefe Museum in Biloxi. The buildings had been leveled by Katrina. It was designed by Frank Gehry, an architect, whose life and work we featured in our book Frank O. Gehry Outside In. We were somewhat familiar with George Ohr, now considered one of America’s greatest potters, but the hardhat tour in Biloxi convinced us that Ohr would be the subject of our next book. A flamboyant character, whose quirky, abstract pots didn’t fit in with conventional tastes, George always believed his work was “Unequaled, unrivaled and undisputed.” Sandra and I had a wonderful time researching and putting this book together, as we loved his art pottery and his wild personality. I will talk more about George as we get closer to pub date.

One of the biggest challenges we faced putting this book together was not only digging up vintage photographs of George and the South at the turn of the century, but also making sure that our young readers could place him in the context of his times. That, along with interviews and extensive research required numerous chapter notes, which is what I’d like to talk about today - the (sometimes dreaded) backmatter that all good non-fiction books must include: a bibliography, chapter notes, permissions for artworks and photographs, even a glossary or an index, and more, depending on the subject, the age group and the author’s decision about pertinent information that doesn’t work in the text. For example in Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring (with Sandra Jordan and illustrations by Brian Floca), we wrote short bios of Martha Graham, Isamu Noguchi and Aaron Copland for the back matter, as the collaboration on the dance was the subject of the book, which is non-fiction but not a biography.

Here are the questions we ask when we’re writing chapter notes:

1. If it is a quote, where did we get it? The source with page numbers. Document this immediately, so you’re not frantically trying to find it later. (Yes we have been guilty of the last minute scramble.)

2. If there are several sides to the story and telling them all in the text is unnecessary, which one do we use? e.g. Andy Warhol and Vincent Van Gogh: There were multiple versions of many episodes in their lives. We chose the versions from by best sources and/or seemed most believable to us. Put the other(s) in the chapter notes.

3. What is the form? We’ve discovered working with a number of different publishers that the forms for the footnotes and permissions vary from place to place, copy editor to copy editor. So we use the form from the last book we did with that publisher and let the copy editor do his/her job. Beware when the publisher farms it out to a temp, if the official copy editor is on sick leave or a vacation. When he/she returns to the office, the form can change drastically and much retyping by the author ensues.

4. What about a information that enhances the story but would be too much of an intrusion into the text? The back matter is a great place to add fuller historical/ anecdotal material that complicates the text or makes it longer than we wanted it to be. We try to balance, to add the extra information we want to share with readers, while not weighing down the backmatter and limitations of space. We love those extra glimpses and hope our readers, both children and adults, will too. Here is an example from The Mad Potter.

In the text we write about the Civil War and how it affected Biloxi, when George Ohr was a child. We did not take for granted that the young reader knows much about the Civil War. We added some historical facts in the chapter notes.

5. Finally do we list the sources of every scrap of information in the book? We use our own judgment on this but try very hard to give credit to primary and secondary sources, either from interviews or in a book or article. Facts, such as dates, names, places, and quoted material, are footnoted. And we always double check factual material.

“

One of the biggest challenges we faced putting this book together was not only digging up vintage photographs of George and the South at the turn of the century, but also making sure that our young readers could place him in the context of his times. That, along with interviews and extensive research required numerous chapter notes, which is what I’d like to talk about today - the (sometimes dreaded) backmatter that all good non-fiction books must include: a bibliography, chapter notes, permissions for artworks and photographs, even a glossary or an index, and more, depending on the subject, the age group and the author’s decision about pertinent information that doesn’t work in the text. For example in Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring (with Sandra Jordan and illustrations by Brian Floca), we wrote short bios of Martha Graham, Isamu Noguchi and Aaron Copland for the back matter, as the collaboration on the dance was the subject of the book, which is non-fiction but not a biography.

Here are the questions we ask when we’re writing chapter notes:

1. If it is a quote, where did we get it? The source with page numbers. Document this immediately, so you’re not frantically trying to find it later. (Yes we have been guilty of the last minute scramble.)

2. If there are several sides to the story and telling them all in the text is unnecessary, which one do we use? e.g. Andy Warhol and Vincent Van Gogh: There were multiple versions of many episodes in their lives. We chose the versions from by best sources and/or seemed most believable to us. Put the other(s) in the chapter notes.

3. What is the form? We’ve discovered working with a number of different publishers that the forms for the footnotes and permissions vary from place to place, copy editor to copy editor. So we use the form from the last book we did with that publisher and let the copy editor do his/her job. Beware when the publisher farms it out to a temp, if the official copy editor is on sick leave or a vacation. When he/she returns to the office, the form can change drastically and much retyping by the author ensues.

4. What about a information that enhances the story but would be too much of an intrusion into the text? The back matter is a great place to add fuller historical/ anecdotal material that complicates the text or makes it longer than we wanted it to be. We try to balance, to add the extra information we want to share with readers, while not weighing down the backmatter and limitations of space. We love those extra glimpses and hope our readers, both children and adults, will too. Here is an example from The Mad Potter.

In the text we write about the Civil War and how it affected Biloxi, when George Ohr was a child. We did not take for granted that the young reader knows much about the Civil War. We added some historical facts in the chapter notes.

5. Finally do we list the sources of every scrap of information in the book? We use our own judgment on this but try very hard to give credit to primary and secondary sources, either from interviews or in a book or article. Facts, such as dates, names, places, and quoted material, are footnoted. And we always double check factual material.

“

Published on January 31, 2013 00:30

January 30, 2013

Embracing--and Seeking--Structure

A

confession: As a writer, I love it when the structure of a project is

predetermined. I'm happiest when given a format, word counts, what Deb

Heiligman called "restrictions" in her terrific INK column last week.

Perhaps it has to do with cutting my teeth as a nonfiction writer at Time-Life

Books, back in the pre-Google days. Each volume of those fabulous series, on

subjects ranging from The Civil War to The Seafarers to Mysteries of the Unknown,

was thoroughly mapped out by a team of editors, researchers, photo editors, and

art directors before the other staff writers and I received our assignments for

it. The layout was pretty much set in concrete, and our job was to write copy

to fit. Heck, we didn’t even do our own research. There was a separate research

staff for that. They gave us thick packets of photocopied material, with relevant

sections already highlighted. If I needed more information for a photo essay or

a picture caption, I asked the researcher assigned to the piece to see what

else he/she could find. It was actually a pretty efficient system, and the

discipline and deadlines it imposed were great training. I still take pride in

the excellent quality of the books this team approach created. But I have to

say I was jealous of the researchers, who got to hang out in the Library of

Congress and other cool places while we writers stayed put at the office. I felt

like I was missing something, the thrill of the hunt perhaps.

After

I left Time-Life to freelance, I was hired to write several books—including one

called Wildflowers —for a children’s nonfiction series called My First Pocket

Guide. Now it was up to me to do the research, and I took to it like a fish to

water. The books had a fairly rigid format. Each book was to be 80 pages long

and feature about 35 specimens. There was one specimen per spread, and each

spread had to include a 2- to 3-sentence introductory text block, a “Where to

Find” map box, a “What to Look For” box listing size, color, behavior, and

“more,” and a Field Note containing a fun fact about the specimen. Each spread

also had to include a line drawing of the specimen, a full-color photograph of

it, and an illustration linked to the fun fact. Although I had to stick to the

format, it was up to me to decide which animals or bugs or wildflowers to

include in the book and how to organize them. I had to create structure within

the existing framework. (It occurs to me, by the way, that creating a similar

book could be a fun classroom writing activity. Each student could research one

specimen and then create a page for it using this format. The students could present

their finished pages to their classmates, and all the pages could be bound into

a book.)

My

newest book, Master George’s People,

took me a long time to write, in part because I struggled with structure for so

long. Other than a word count, I had no restrictions to help me out, no

comforting format to follow. I only knew that I wanted to tell two stories in

the book—the story of what life was like for George Washington’s slaves and the

story of how Washington’s attitude toward slavery changed over his lifetime. I

had to fight against letting Washington’s story overshadow the other. I finally

found my way in by returning to (this won’t surprise many of you) the primary

source material. Once I identified a pivotal scene for an opener—that of slave

children playing in Washington’s boxwood garden—the rest of the structure

seemed to spin out more or less logically, although I can't say the process went smoothly.

Although

I’m pleased with the final result, I can’t help feeling that I approached the

issue of structure backwards in this case, making things harder for myself than they had

to be. Next book, maybe even while I'm still researching it, I’m going to try tackling structure first. Maybe I'll sketch a diagram or "a looping doodle with guiding arrows and stick figures," a strategy discussed by John McPhee in his recent New Yorker article about structure. The idea, he writes, is to "build some form of blueprint before working it out in sentences and paragraphs." A blueprint, that's kind of like a format. And did I mention that I'm very comfortable with formats?

Published on January 30, 2013 02:00

January 29, 2013

A Bird’s Eye View of Teaching Persuasive Essay Writing

This summer, part of my job was helping some 4th

and 5th graders hone their skills at writing persuasive essays. This

essay form is often seen on standardized tests and is the style kids tend to hate

the most. The format must be strictly followed and the rules can be

intimidating. There must be five full paragraphs: Introduction, Reason 1,

Reason 2, Reason 3, and Conclusion. Yes, each essay must state three reasons

and you have to write a full paragraph elaborating on each reason.

Boy, kids really hate this. Can’t you hear the whining now

about how they can only think of two reasons? Even though the essays are

usually about “kid friendly” topics, they’re not the kind of subjects kinds

enjoy pondering, especially when faced with the pressure of writing five

paragraphs in 30 or 40 minutes. Honestly their feelings about whether there

should be vending machines in school or all students should wear uniforms is

usually rather limited and their fear about if they will have enough to write

seemingly never ending.

So instead of rote practicing, I used non fiction books to

get them thinking. After we talked

about the life experiences of a certain bird in New York City, my students had

a much better understanding of perspective and point of view. And once we put

those things together, their essays really started to flow.

I chose I.N.K. books about a bird named Pale Male, a hawk

who chose to build a nest on a swank 5th Avenue Apartment building

near Central Park in NYC. This was fascinating to city bird watchers because

Hawks were rare in the area but it became a full blown news story when the

ritzy apartment building removed the hawk’s nest because of the resulting mess

in front of the building and the constant peeking eyes of the bird watchers

with large telescopes in Central Park.

There are at least three good non fiction children’s books

that I know of about Pale Male. The story and illustrations are a great way to

introduce the concept of perspective. The hawks fly high above Central Park and

the buildings, giving them a perspective to search for their prey, see the

natural beauty of the city, and keep away from the crowds. In the trees or

lower on the ground, they can be vulnerable to large groups of crows or people

touching their nests. These books also open up a conversation about

perspective’s cousin, point of view: what did the hawks want and need, how did

the bird watchers want to help them, and how was this the same or different

from how the people living in the apartment building thought about birds

nesting there?

I ‘ve also found it effective to read two of these books and

compare and contrast. What points of the story did each writer focus on? What

were some details that were included by one writer but left out by the other?

Are there any facts that were absolutely necessary in order to tell the story?

These discussions translated easily and naturally to the

persuasive essay form. The kids began to understand that students will often

see an issue differently than a teacher or parent or the Principal based on

their point of view. They could expand their reasoning when seen from another

point of view and based on whom they were trying to convince. Is the letter to

a friend or relative? Lets talk about how you could have fun and do things

together. If the letter is to the Principal, you can focus on reasons such as

safety, health, learning, and community.

From my perspective,

using non fiction is tremendously effective in helping kids expand their own

way of seeing things and how others see things. This enables them to feel much

more confident about their reasoning and, ultimately, helps them express that

more naturally in their writing.

Published on January 29, 2013 03:00

January 28, 2013

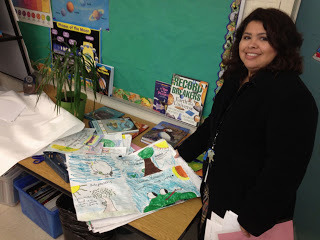

A School Where Science (and Non-Fiction) Rule

It’s hard to imagine a teacher prouder than Maria Martinez,

or second graders happier with what they're learning and how they're learning it in her classroom. The best part is that I

can say the same thing about the other teachers and students I met at

Sci-Tech Academy at Knights Landing, in California's Sacramento Valley. They are the Sci-Tech “Robots” at

this public charter school where the mascot is not a ferocious animal and the motto is

“Hands On—Minds On.”

In 2009, the Woodland Joint Unified School District closed Kings Landing's only school, Grafton Elementary. The rural community's population was under

1,000 and the district knew it could save $s by shutting the school door and sending students eleven miles to Woodland. It’s a scenario that has befallen rural communities and urban neighborhoods across the country, and usually the teachers and

residents sigh and bear it. But a cadre of dedicated teachers in the Woodland district,

including Ms. Martinez, came up with another plan. They would form a K-6 charter

school focusing on science and technology, and they would petition the district

to let them use the Grafton building. After just one

year in mothballs, Grafton Elementary was reopened as Science and Technology Academy at

Knights Landing. Local parents started enrolling their children as did others from

communities nearby, and still others from outside the district — even some from Davis, 20 back-road

miles away, an acutely eco- and education-minded small city boasting

blue-ribbon schools and a University of California campus with renowned science

programs.

My tip-off to something special

going on at Sci-Tech came during my first presentation to primary grade

students. I showed my book on animal camouflage, Where In the Wild? Camouflaged

Creatures Concealed… and Revealed. The word “camouflage” is often understood

by primary grade students but I’d never before met second graders who used the word

“adaptation” when describing it.

“We just finished a unit on animal

adaptations,” explained Ms. Martinez when we chatted later. The M.O. at

Sci-Tech is that science units define the entire curriculum. A unit on

adaptations means that students read a range of non-fiction books about ways

animals have evolved to meet the demands of their environment. “We do our reading to fit our science units, and everything

else comes out of that,” she explained. They explore the vocabulary they find

in their reading. Writing, discussions, further explorations ensue. Math gains

relevance by being tied to the science units.

Modern digital technology is important

in supporting the inquiry-based classroom at Sci-Tech, but not at the expense

of low-tech. Not only do print non-fiction books abound, but so do animals in

captivity — live ones, not virtual

pets on a smartphone. Every classroom has them. “The students learn what it

means, and what’s required, to take care of animals,” says sixth grade teacher Glen

Lusebrink, “and we also use the animals to get to other areas of the

curriculum.” His room has fish tanks populated by a variety of cichlid species.

“This one is from Africa,” he tells me, “and these are from South America.” So

we get out the maps, the globes, the books and we learn about Africa, we learn

about South America.

Because

of my presentation schedule, I did not get to see any classrooms in action, but

I learned about some of the action over lunch in the staff lounge. In all of the conversations, teachers were buzzed about their students' latest hands-on discoveries.

First graders had been sifting rocks into size gradations (there’s a math

lesson there along with the science) and Kindergarteners had just finished

distinguishing between water and identical-looking salt and sugar solutions by

testing various properties of the liquids, including taste. “Oh, I wish I’d

videotaped them,” said their teacher. “When they were tasting that salt

solution—you would have loved the looks on their faces.” And the impressions on

their minds.

Clearly,

the hands-on approach touted by the school’s motto is more than a marketing

phrase. And it is even more than an impassioned approach to science and the

rest of learning. For some students, it’s a matter of do or (academically) die.

“Our school makes learning possible for children who do not thrive in an environment

of seatwork and workbooks,” says Principal Barbara Herms who holds the view

that when hands and bodies are active, so are minds. “And our success is

showing.” I asked if she was referring to test scores. “Yes, that among other

things.” I’m heartened to know that test scores are up but I’m even happier to

know that here tests aren’t the only measure of student success.

Parents

are often the most vociferous critics of schools, so I looked up Sci-Tech Academy on www.greatschools.org and found five (out of five)

five-star reviews by parents. One will suffice: “All the teachers, staff,

parents and children are excited about learning! This school’s atmosphere is

all about helping each child reach their full potential. My children do not

even like missing one day of school.”

Need

I say more? Probably not, but I will anyway. A curriculum connected to close

readings of non-fiction texts sounds like it has the Common Core State

Standards written all over it. But Sci-Tech has been doing it since before

those four words were ever strung together.

Published on January 28, 2013 02:00