Mike Elliott's Blog

October 14, 2025

How to Remove Fiberglass from a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

For those of you new to this blog and have not heard me on this topic before, let me be as clear as I can be: To anyone thinking about applying fiberglass to a wood-canvas canoe, I say, “DON’T DO IT!” To anyone wanting to remove fiberglass from a wood-canvas canoe, the short answer is: HEAT.

Wood-canvas canoes are a product of a by-gone era; a time before planned obsolescence, when things were built with the long term interests of the consumer in mind. The whole idea of building a canoe with wood and canvas was to have a vessel that lives and breathes. These canoes work in the natural environment and are part of it. They are held together with tacks and screws — no glue. The wood flexes and moves with the water around it. When part of the canoe breaks or rots, it can be repaired or replaced with comparative ease because it is designed to be taken apart and rebuilt. As long as there are people who know how to restore canvas-covered canoes, they will live forever.

It has been about forty years since these canoes were the standard in the marketplace. Not only has the technology of wooden canoe repair faded into obscurity, but the mindset of both manufacturers and consumers has also changed. Synthetic materials are now generally seen as better — easier, tougher and longer lasting. The consumer has been convinced that the new materials can improve that which is outdated or at least maintain it quickly and easily.

When it comes right down to it, wooden canoes and fiberglass just don’t mix. Since the ribs and planking are held together with tacks, they flex and move naturally. Over the years, the tacks tend to work loose and eventually have to be either re-clinched or replaced. Conversely, fiberglass resin is rigid. Once applied, it tends to resist any movement. The combination of a flexible hull and a rigid outside layer results in cracked or delaminated resin. The tacks can also wear against the resin from the inside to the point where they come right through the resin. It can take several months or several decades, but at some point the canoe needs to be repaired and the fiberglass has to come off. It is then that the real problem comes to light. All of that synthetic resin has to be removed. It is a long, painstaking process that usually has you cursing the person that put the stuff on in the first place. The moral of the story is: Avoid applying fiberglass to the hull of a wood-canvas canoe. Learn how to re-canvas the canoe or find a professional to do it for you.

This leads us into the next question: How do you remove fiberglass from a wood-canvas canoe? All you require is a professional-grade heat-gun, a 2” putty knife, a pair of pliers, safety equipment (work gloves, safety glasses and a respirator mask) and lots of patience. The first step is to move the canoe into a well ventilated work space; preferably outdoors. Then start at an edge of the canoe and apply heat to the resin.

At this point it is important to note that fiberglass resins come in two basic types; polyester and epoxy. Polyester resins were the first to be developed. If your canoe had fiberglass applied to it in the 1970’s or earlier, you can bet that polyester resins were used. They tend to become brittle and deteriorate rapidly, so if the fiberglass on your canoe is delaminating it is most likely that you are dealing with a polyester resin. Fortunately, this makes the removal of the fiberglass relatively quick and easy. In many cases, the cloth can be ripped off by hand with very little need for heat. When I say rip, please be gentle. If you get carried away and pull at the fiberglass cloth too rapidly, you could end up tearing sizeable chunks of planking off the canoe as well (I speak from first-hand experience).

Epoxy resins hit the market in a big way in the 1980’s and are the standard today. They are applied by first mixing a hardener with a resin in a two-part formula. What results is a strong, tough plastic that bonds very well to wood. Unfortunately, this means that the removal process is arduous and painstaking.

As mentioned earlier, start at an edge of the canoe and apply heat to the resin. If you are dealing with epoxy resin, you will probably have to apply the heat for several minutes before the cloth begins to respond to your attempts to lift it with the putty knife. At some point, it does let go and the fiberglass cloth can be separated from the canoe. Then move a few centimeters and continue the process. Again, polyester resins let go fairly quickly. You will find that large sheets of cloth come off in fairly short order. I usually grab the cloth with a pair of pliers rather than with my hand. Even with work gloves on, the pliers prevent nasty encounters with heat and/or sharp edges of fiberglass (again, this is the voice of experience talking).

Once all of the fiberglass cloth is removed, return to the canoe hull with the heat gun and a putty knife. Apply heat to any patches of resin still stuck to the wood. Then, scrape the resin off. Be prepared to settle into hours of tedious work. It typically takes 15 to 20 hours to remove the fiberglass cloth and resin from a 16′ canoe.

Once you are back to the bare wood, the restoration is like that of any other wood-canvas canoe. So, enjoy the pleasures of life in the slow lane, stay away from fiberglass and celebrate the fact that you have a wood-canvas canoe.

Many people complement me on the great fiberglass job on my canoes. They are shocked to learn that the canoes are covered with painted canvas.

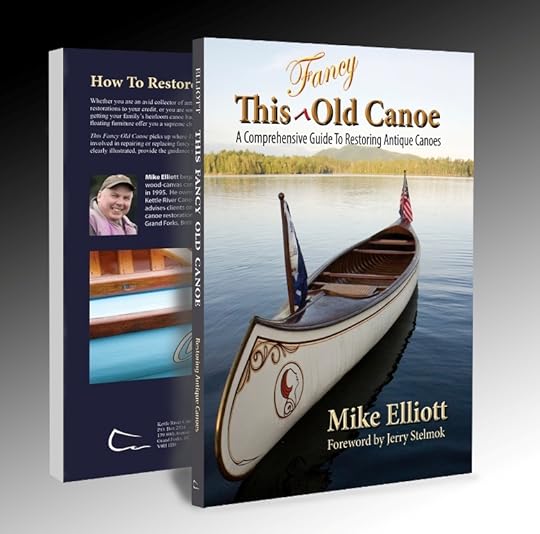

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

September 22, 2025

How To Make Highly Curved Stems for a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

During the restoration of a wood-canvas canoe, it is rare to have to replace the entire stem in the canoe. However, when faced with the restoration of a canoe which is more than 100 years old, a new stem (or two) is more than likely going to be part of the project.

I restored a J. H. Rushton Indian Girl canoe (c. 1905). Both stems had extensive rot and one was broken in two places. Rushton made his stems from a solid piece of rock elm. Since this wood is nearly extinct now (thanks to Dutch Elm Disease), I used straight-grained ash 1″ (25mm) thick (at the lumber yard this is referred to as 4/4 ̶ pronounced four-quarters).

The first step is to remove the stems from the canoe. I use both a tack remover and a Japanese concave cutter bonsai tool to remove the fasteners without doing too much damage to the ribs, planks and stems in the canoe.

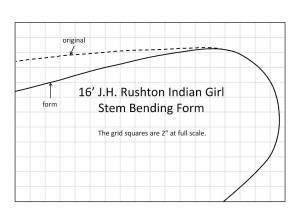

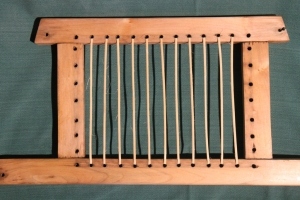

The next step is to create a bending form. Here, I present the dimensions of the bending form required for the Rushton Indian Girl.

It is comprised of three layers of 5/8″ (16mm) plywood. I ask my local building supply centre if they have any damaged sheets of plywood. I can get all of the wood I require for a fraction of the cost of full sheets of plywood. All three piece have the same curve but the centre piece of plywood has a longer base which clamps easily into a work-bench vice.

I start by placing the original stem on one piece of plywood and drawing the inside curve of the stem onto it.

I then keep the stem-top in the same location as the original while rotating the stem until the curve is about 3½” (9cm) greater than the original. The form shape is then drawn onto the plywood and is extended about 6″ (15cm) at both ends to accommodate the clamping system.

The form shape is cut with a saber saw or band saw. The first piece is then used as a template for the other two pieces. Once assembled, the form is sanded more or less square with a belt sander or an angle grinder set up with a 24-grit wood grinding disk. The final form is 1.875″ (48mm) wide.

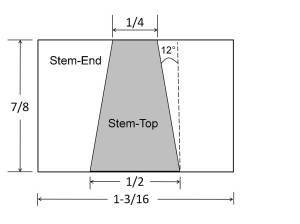

The base-end of the stem is 1.1875″ (30mm) wide and 0.875″ (22mm) thick. I bend a piece of ash which is 1¼” (32mm) wide and 1″ (25mm) thick. This allows me to shape an exact replica of the original.

The clamping system is attached to the bending form with enough space for the new wood and a backing strip. The new stem stock is soaked in water for four days, steamed for 60 minutes and bent onto the form where it remains for at least a week. When removed from the form, the new wood will spring-back slightly and ought to come to the same shape as the original (or close enough).

The original stem is much more than just the curve in its profile. It is tapered at the stem-end, angled to accept planking and notched to accept ribs. Draw the rough dimensions and contours onto the new stem (first with a pencil and then with a permanent ink pen).

Use a Japanese cross-cut saw or a dovetail saw to cut the sides of the rib notches at the correct angles and depths. Use a wood chisel and mallet to remove the bulk of the material in each notch.

Check the dimensions of each notch on the original and use the chisel to shave each new notch to the desired thickness.

Use an angle grinder set up with a 24-grit wood sanding disk to carve the desired angles and tapers into the new stem.

Work slowly and carefully with a random-orbital sander and 60-grit sandpaper (checking dimensions with calipers against the original) until the new stem is an exact replica of the original.

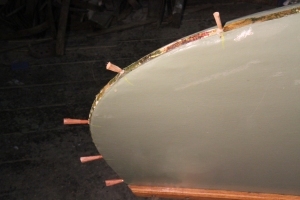

Turn the canoe upside down and use spring clamps to hold the new stem in place while you drill pilot holes for bronze ring nails to attach it to the ribs.

Use a cobblers hammer backed with a clinching iron to drive the ring nails tight.

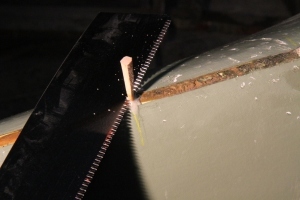

Turn the canoe right-side up and sight down the center line. Position the stem so it is lined up straight down the center line and clamp it in place. Pre-drill holes for 16mm brass canoe tacks and attach the new stem to the original planks.

Mark the height of the stem-top against the underside of the inwale ends.

Use a Japanese cross-cut saw to trim the stem-top to its desired height. I cut it a little long and use a random-orbital sander to achieve a snug fit.

Attach the rest of the planking to complete the job.

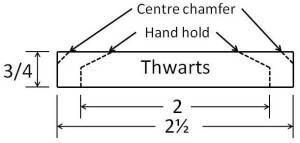

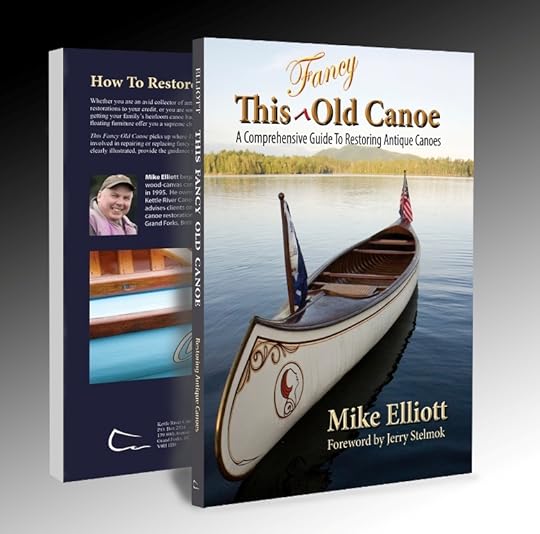

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring Antique Canoes.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

August 11, 2025

How to Install a Keel on a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Speaking strictly in terms of form and function, canoes and keels don’t belong together. Canoes are designed to sideslip easily in large, rapid rivers in order to avoid various obstacles along the way. However, wood-canvas canoes have often been part of the family for decades. In this context, they must also be seen through the lens of family history and tradition. Many wood-canvas canoes were built with a keel installed and that is the way the owner wants it to remain. For this reason, I have no problem installing a keel on a wood-canvas canoe.

Most keels were removed at the beginning of the restoration project and are being re-installed. Therefore, the first step is to clean it and remove old paint and bedding compound. This is usually a two-step process. I start with an angle grinder set up with a 24-grit sanding disk. This cuts through the worst of the old material and gets down to the original wood. Care must be taken in order to remove only the old paint and bedding compound. Finish the job with a random-orbital sander set up with 80-grit sandpaper. This removes any marks made by the grinder and creates a smooth surface for new bedding compound and paint.

Having just spent a lot of time and effort creating a waterproof canvas cover, it seems a little strange to then poke a dozen or more holes through the bottom of the canoe. It is essential, therefore, to use a bedding compound that seals the keel to the canoe, creates a waterproof barrier and stays flexible for decades.

Having tried a variety of products, I have returned to the old school. Dolfinite 2005N Natural Bedding Compound is a linseed oil-based compound with the consistency of peanut butter. It is the same as the bedding compounds used a century ago. Unlike more modern compounds (such as 3M 5200 or Interlux 214) it stays flexible for the life of the canvas (several decades), seals well, accepts paint well and yet allows the keel to be removed from the canvas if necessary some years down the line.

Most canoes use 1” (25 mm) #6 flat head silicon bronze screws combined with brass finish washers. Begin by driving one screw into each end of the canoe. Turn the canoe on its edge to allow access to the bottom of the canoe inside and out at the same time. This is where it is useful to have the canoe set up on two canoe cradles.

With one screw at each end, move to the outside of the canoe and line up each screw with the original holes in the keel. Use a permanent-ink marker to show the position of the keel on the canvas. Then mark the location of the screw where it comes through the canvas and mark the location of the screw hole on the side of the keel to facilitate attachment later.

Apply bedding compound generously to the keel with a putty knife. Any excess will be cleaned up later. For now, it is more important to ensure a good seal along the entire length of the keel. Then, open the original screw-holes at each end to make it easier to find them.

Not everyone has my “wingspan” – 79” (200 cm) from finger-tip to finger-tip – so not everyone can hold the keel in place with one hand and drive the screw with the other at the same time. Installing a keel is normally a two-person job. Get someone to line up the original holes in the keel with the screws coming through on the outside of the canoe while you drive the screws from the inside. Sometimes, the original holes in the keel have been stripped. In this case, use larger diameter 1” (25 mm) #8 screws to secure the keel. If the keel has warped a little, you may need 1¼” (32 mm) screws to draw it tight to the canoe. In this situation, especially with Chestnut and Peterborough shoe keels (3/8” thick), the screws may go right through the keel and poke out on the outer surface. That will be dealt with later.

Once both ends are attached, check to make sure that the keel is properly lined up with the center of the canoe. Once aligned, drive the rest of the screws along its full length. Usually, it is necessary to apply some pressure on the keel in order for the screws to catch properly. Sometimes, I need to get under seats to drive the screws. This is where a flexible drill extension comes in very handy. Most of the time however, I have removed the seats to refinish or weave new cane, so access to all of the screw holes along the canoe’s centerline is not a problem.

Remove excess bedding compound from the edges of the keel and apply more to areas that are not completely sealed. Remove any bedding compound stuck to the canvas using medium steel wool soaked in lacquer thinner. Use a file to take care of any screw tips poking through the keel. Finally, let the bedding compound cure for a few days before applying paint.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

August 4, 2025

How to Repair Loose Stem Bands on a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Wood-canvas canoes are works of art. However, in Canada, they are also working boats. They help their owners navigate large, rapid rivers on a regular basis. In the course of these journeys, the stem bands will knock against rocks. After a while, the canoe will begin to leak as water seeps in through the screw holes. I restored a canoe for a client a few years ago and now he brought it back to the shop for a little repair work.

The screws holding the bow stem band to the hull had worked loose and the seal had broken between the hull and the stem band.

I started by removing the stem band. Some of the screws had been worn down to the point where a screwdriver was no longer effective. A cats-paw pry bar and a mallet popped the stem band off in short order. The stem band was set aside to be installed later.

The location of every screw hole was marked with a grease pencil.

Small pegs were whittled from a scrap piece of cedar. The pegs were dunked in water, coated with polyurethane glue and tapped into the screw holes with a mallet. The glue was allowed to cure overnight.

Each of the cedar pegs was cut flush with a Japanese cross-cut saw.

The entire painted surface of the canvas was sanded with 120-grit paper on a random-orbital sander. Most of the bottom was scuffed and/or gouged by encountered with rocks. The sanding smoothed out the surface and prepped it for a fresh coat of paint.

The stem band was installed with new bronze screws (in this case, ¾”- #4 flat-head, slotted screws). It was sealed with Dolfinite marine bedding compound and allowed to set overnight.

The outwales were masked with tape before a fresh coat of oil-based alkyd enamel paint (thinned 12% with paint thinner) was applied with a disposable foam brush.

The masking tape was removed about an hour after the paint was applied. Any paint that ended up on the outwales was removed with a little paint thinner on a clean rag.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

July 28, 2025

How To Build Cradles (Display Stands) for Wood-Canvas Canoes

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Once you’ve got your canoe out of the shed for the season, you’ll need some way of supporting it off the ground when it is not on the water. I can still hear my father saying, in no uncertain terms, “The bottom of this canoe touches two things: air and water”. One of the most convenient support systems is a pair of canoe cradles.

They are quick and simple to build and can be stored easily when not in use. They are also essential tools when repairing or refurbishing your canoe.

For the cradles I build, each one consists of two vertical struts, two base struts, two horizontal brace struts, two sling clamps and a cradle sling. All you need to build a pair of cradles are:

4 – 8’ 2×4’s (spruce) to make the struts;A bunch of 2½” deck screws to hold the whole thing together and;2 strips of material 3½” wide for the slings (I use pieces of carpet or scraps of canvas leftover from a canoe project). I have seen some people use 3/8” rope for the slings.As far as dimensions are concerned, I find a stable design that still holds the canoe off the ground at a comfortable height have vertical and horizontal struts that are 26” long. The base struts are 24” long and are oriented parallel to the centerline of the canoe to create stable “feet” for the cradle. The sling material is about 50” long. The clamps are just scrap pieces used to hold the sling material to the vertical struts. These can be about 6” long – whatever you end up with.

To build a cradle, start by creating the two sides. They each consist of a base strut attached to the end of a vertical strut to form a T-shape.

Next, the 28” bottom brace strut is attached between the two sides and the 28” upper brace strut is positioned somewhere in the middle of the vertical strut.

I take a minute to round-off the inside corners of the vertical struts. Otherwise, the sling material wears out quickly and has to be replaced frequently. I use an angle grinder to round the corners, but the same job can be done with a rasp and a little elbow-grease.

Construction of the cradle is completed by attaching the sling by means of the clamps. The whole process takes the better part of an hour for both cradles. If you want to pretty them up a bit, the struts can be rounded off and sanded smooth.

Any cradles that are going to spend a lot of time outside are finished with an opaque oil-based stain to protect the wood.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

July 22, 2025

How To Assemble a Repair Kit for a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

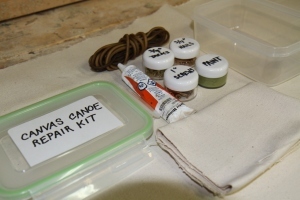

As I was completing the restoration of an 18′ Chestnut Prospector Vee-Stern canoe for a client, he asked me to create a wood-canvas canoe field repair kit for him. He lives in Whitehorse and plans to use the canoe on hunting trips in the Yukon. A few basic supplies along with a hammer, a screwdriver and the ubiquitous roll of duct tape are all you need to hold your canoe together until you get out of the bush and back to civilization.

The kit fits into a small food container (900 ml or 30.4 fluid ounces) and consists of the following items:

a piece of #10 (14.5 ounce) canvas 12″x12″ (30 cm x 30 cm)10′ (3 meters) of 3/16″ rawhide lacing (babiche)a tube of waterproof glue (Ambroid glue is no longer available but you can use a polyurethane glue — such as Gorilla Glue — instead)30 – 3/4″ (19 mm) brass canoe tacks20 – 3/4″ (19 mm) silicon bronze 14-gauge ring nails12 – 1″ #8 silicon bronze flat-head square-drive wood screwsa small container of alkyd enamel paintYou also need to pack a clinching iron (auto-body dolly) in order to clinch the tacks when the time comes to use them. Most of the supplies are self-explanatory except for the babiche. It is very useful for lashing a broken thwart back together or holding a make-shift thwart (tree branch) in place. Soak the babiche for about 6 hours, do your lashing and let it dry overnight. The babiche will tighten and hold anything without fail.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

June 29, 2025

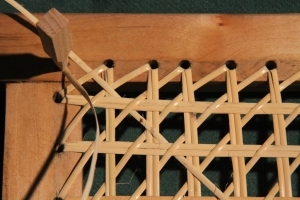

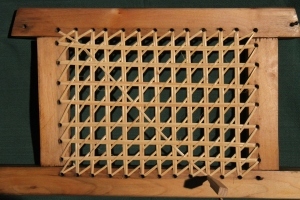

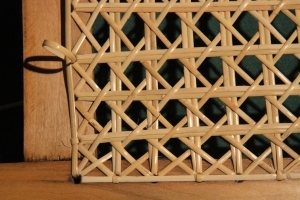

Weaving Pattern for Cane Seats in Peterborough Canoe Company All-Wood Canoes

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

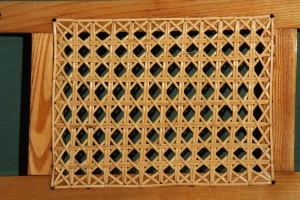

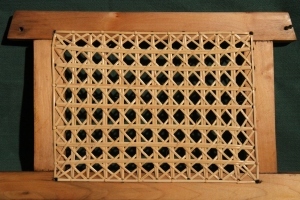

In my book, This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood-Canvas Canoe, I describe how to weave natural cane (rattan) in Chestnut canoe seats. However, most canoe builders used their own weaving pattern for their canoe seats.

The Peterborough Canoe Company (1879 – 1961) installed hand-woven cane seats in many of their wood-canvas canoes as well as many of their all-wood canoes. The pattern they used in their all-wood canoes is similar to the six-stage “quick” pattern used by the Chestnut Canoe Company (1897 – 1978). Only the sixth stage in the pattern is different. In the Chestnut pattern, both diagonal weaving stages (fifth and sixth stages) weave under the vertical strands and over the horizontal strands. In the Peterborough pattern, the sixth stage weaves over the vertical strands and under the horizontal strands.

In my book, I describe the full process of preparing the seat frames, preparing the cane and handling the cane during the weaving process. Here I will present the basic look of each stage and give details for the sixth stage only for the Peterborough pattern.

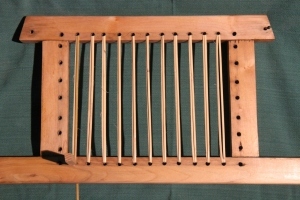

First Stage ̶ Vertical strands

Second Stage ̶ Vertical strands arranged beside the strands of the first stage

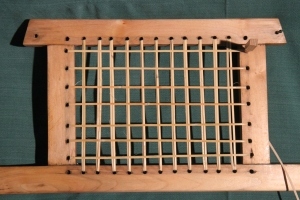

Third Stage ̶ Horizontal strands

Fourth Stage ̶ Horizontal strands arranged beside the strands of the third stage

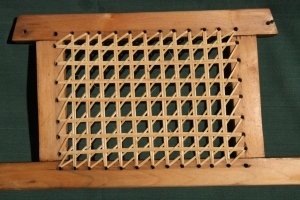

Fifth stage – Diagonal strand woven under the vertical strands and over the horizontal strands

Sixth stage – Begin the pattern in the empty corner on the transverse rail of the seat. Feed one end of the cane strand through the corner hole from the top-side to the under-side. Secure the strand-end in the usual manner. Secure the strand in the corner hole with a caning peg on the top-side.

Trim the working-end of the cane strand to create a sharp point. This makes weaving easier. Make sure the shiny side of the strand faces up and is not twisted. Start the weaving pattern by going under the diagonal strand next to the corner hole on the transverse rail of the seat. Then, weave over the first set of vertical strands in the pattern and under the first horizontal strands. Continue in this way (over the second set of vertical strands and under the second horizontal strands) until you reach the opposite transverse rail.

Make sure you weave under the diagonal strand on the transverse rail before threading the strand down through the hole. Pull the strand snug (but not tight) and secure the strand with a caning peg.

Continue with this pattern for each diagonal strand as you work toward the empty corner in the bottom transverse rail of the seat frame. As usual, the corner hole has two strands since it is both a hole along the transverse rail and the side rail. The strand going into the corner hole as part of the transverse rail strands weaves under the final diagonal strand before entering the hole. The second strand from the corner hole begins by weaving over the diagonal strand, then under the first set of horizontal strands and over the first set of vertical strands. Continue in the way until you reach the top transverse rail of the seat frame.

I rarely weave the Peterborough pattern. Consequently, I have to check and re-check my work constantly. I work slowly and carefully to ensure that my mistakes are made as quickly as possible.

Complete the sixth weaving stage at the corners of the seat. Make sure the strand weaves under the diagonal strand from the transverse rail and over the diagonal strand from the side rail.

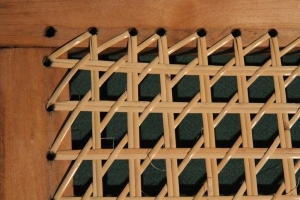

Complete the seat weaving with the usual “couching” to cover the holes in the seat frame. The couching is held in place with loops of cane in every second hole around the seat frame.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring Antique Canoes.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

May 13, 2025

How To Buy or Sell a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Frequently, I get an email from someone who is looking to sell their wood-canvas canoe. Typically, they tell me, “The canoe has been stored under cover for the last twenty years and is in excellent shape. What would be a reasonable price to ask for my canoe?” Conversely, a person is considering the purchase of an old canoe and wants my opinion on whether or not the asking price is a reasonable one. In both cases, the best I can do is refer them to what I see on classified ads offering other wood-canvas canoes for sale.

I guess the simplest answer is: “It is worth whatever someone is willing to pay.” I have a hard time seeing these canoes as commodities. That is why I am in the business of repairing and restoring wood-canvas canoes. My clients tend to value their canoe based on a set of criteria far removed from monetary concerns. That said, wood-canvas canoes are bought and sold. Most of them are at least thirty years old and range in condition from pristine to ‘ready for the burn pile’. So, let’s look at the market and what tends to be ‘the going rate’.

Fully restored wood-canvas canoes tend to be listed in classified ads in a range from about $3,500 to $7,000. Bear in mind that a brand new 16′ Old Town Otca canoe – made by hand on the original building form – currently sells for $6,000 – $6,700 USD (about $8,200 – $9,200 CAD). Serviceable canoes that need some work tend to be offered somewhere in the neighbourhood of $1,500 to $2,500. Canoes requiring a full restoration can be picked up for $50 to $500 (and sometimes you can get the canoe because you are willing to cart it away).

When people ask for my opinion on a specific canoe, I base my answer on what a professional canoe restoration shop would charge to bring it back to ‘like new’ condition. Almost any ‘original canoe in mint condition’ will require a new canvas. Unfortunately, the original canvas will only last about forty years (Oh, how I long for a return to the days before planned obsolescence). If the work is done by a professional canoe restorer, you are looking at spending about $2,000 to $3,000 after you have bought the canoe (all of these prices are in Canadian dollars). If the canoe ‘needs a little work’, be prepared to pay for a full restoration which could cost in the range of $3,500 to $5,500. And if it is a ‘basket-case’, the bill could far exceed what you would get for it if you ever decided to sell it (not unlike the cost of renovating an old house). So, when you see a fully restored canoe listed in a classified ad for $4,500, they are probably just trying to recoup the cost of the restoration.

About seventeen years ago, I bought an original Greenwood Canoe for $900. The bulk of the woodwork was in excellent condition and the interior varnish was still in very good condition. The canvas was original (about forty years old) and although it was not rotting, it needed to be replaced. Greenwood canoes are well-known to wood-canvas canoe enthusiasts in British Columbia. Bill Greenwood built canoes in Richmond, BC from the mid 1930’s to 1975. His workmanship was unequalled not to mention all of the Philippine mahogany (lauan) used in components such as gunwales, decks and thwarts. Anyone who knows these canoes bows their head in reverence whenever they speak of Bill Greenwood and his canoes.

In my shop, I brought the canoe back to life. The original mahogany outwales were shot, so I replaced them with exact copies. I added a couple of coats of varnish to the woodwork and painted the new canvas the dark green that was typical for Greenwood canoes.

The next spring, I replaced the original slat seats with mahogany-framed hand-woven cane seats in the style of Greenwood canoes. I removed the bow-quarter thwart, installed a mahogany carrying yoke and moved the stern-quarter thwart to a position halfway between the stern seat and the centre yoke. I had no intentions of selling this canoe and, at that time, I had not seen a restored canoe sell for more than $2,500. So, when anyone asked me how much I wanted for it, I told them, “The canoe is all yours for $4,500.” In 2008, someone fell in love with my canoe and handed me a check.

Ten years ago, I finished restoring a 16′ Chestnut Prospector for myself. I replaced the original solid-wood slat seats with hand-woven cane seats replicating the Chestnut style of cane seats. I then painted the canvas the original light green colour and installed copies of the original Chestnut deck and hull decals. These days, I rarely see a fully restored canoe selling for more than $5,000. If anyone asks me what I want for it, I will say, “$10,000 — but it’s not for sale.”

If you are selling, it is possible to get the price you are looking for. Just be prepared to wait a long time for that ‘special someone’ to come along. If you are buying, be prepared to factor in the cost of a full restoration once you have purchased the canoe.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

April 28, 2025

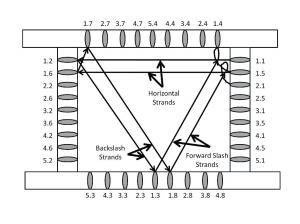

How To Weave Rawhide (Babiche) Seats for “Huron” Wood-Canvas Canoes

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

If the seats in your canoe are laced with rawhide similar to that in old snowshoes, chances are you own a “Huron” canoe – the generic name for canoes built in Huron Village (renamed Wendake in 1986). The “babiche” is likely to last longer than the canoe, but at some point you may need to lace the seat frames with new rawhide.

Seat frames for “Huron” canoes are constructed of birch or maple and assembled with mortise and tenon joints that are very rough and loose. No glue is used in the joinery, so the rawhide lacing is the only thing holding the frames together. As with all of the other components in a canoe, I prefer to apply finish to the frames before I lace them. The bow seat requires about 65’ (20 meters) of 3/16” (5 mm) rawhide lace while the stern seat requires about 50’ (15 meters). The lacing is usually shipped in a long tube and is as hard as a rock. It has to be soaked for several (at least 6) hours before it can be used to lace the seats. I use the bath tub at home and add a little borax to the water to help loosen the rawhide and make it easier to manipulate. It will take a few hours to lace a seat, so keep a large bowl of water nearby in order to soak the rawhide repeatedly as you work. Handling rawhide lace for several hours can be hard on the hands and the borax can really dry out your skin. Use a hand lotion both before and after lacing a seat to help avoid damage to your skin.

The lacing pattern I describe is the most common one found in canoe seats. It is by no means the only one. The process can be applied to all the other patterns. However, some are more complicated than others. The stern seat has 36 anchor points – 9 on each of the 4 frame rails. The bow seat is wider than the stern seat. Therefore, it usually has 11 anchor-points on each of the frame rails. In order to make this fit, the anchor-points on the side rails are placed very close together. This will provide enough room for one more complete repetition of the pattern.

The only tool I use is a sharp pocket knife. It trims the lacing and cuts small slits in the ends of pieces for joining. The entire pattern is laced using just a few basic knots and joins. The starting anchor join at 1.1 is made by threading the lace through a small slit in the end of the first lace in the pattern. Throughout the lacing pattern, pull the rawhide firmly but not tight. As the rawhide dries, it becomes very tight.

All of the remaining anchor points are tied using a larks-head knot. To perform this knot, you start by passing the lace over the frame. Wrap around to come up on the “outer” side of the lace and pass over the strand that was just made. Bring the lace back under the frame, then around to finally pass back over the frame and under the lace “bridge” to form the knot. In this case, a picture is worth a thousand words, so use the photo as your guide.

Anchor-points 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4 form a triangle pattern on the frame. As you go from 1.3 to create the anchor-point at 1.4, pass the strand under the horizontal. The strand then passes over the horizontal and under the diagonal “forward slash” ( / ) strand before tying off at anchor point 1.5. All subsequent weaving in the fourth strand follows this pattern.

The fifth strand of the pattern passes over the forward slash strand and under the “backslash” ( \ ) strand before tying off at anchor point 1.6. All of the subsequent weaving in the fifth strand follows this pattern.

The sixth strand weaves over the “backslash” strand and under the horizontal strand before tying off at anchor point 1.7. All of the subsequent weaving in the sixth strand follows this pattern.

The seventh strand passes over the horizontal strands and under the “forward slash” strand before tying off at anchor point 1.8. All subsequent weaving in the seventh strand follows this pattern.

The eighth strand does not have any weaving, but it finishes by passing over both the fourth and the fifth strands at the fifth anchor-point in that repetition of the pattern. It wraps under the strands and then up and over itself before forming the first anchor-point in the next repetition of the pattern.

From now on the pattern is repeated with one addition. After forming the second anchor-point in the pattern and before weaving the second strand, stabilize it by passing over both the fifth and seventh strands of the previous set, then come up and over itself. The second strand requires no weaving.

The seat is woven with progressively more and more weaving required as each set of the pattern is performed.

At some point, usually two or three times in a given seat, you come to the end of a piece of rawhide lace. To continue weaving, join the next lace to the previous one. The joins are made by cutting a small slit in each end. The end of the old strand is passed through the slit in the new strand. The entire new strand is then fed through the slit in the end of the old strand to create a secure join. I like to locate the joins so they lie on the underside of the frame.

Once you have completed the lacing pattern, the last larks-head knot is tied at the final anchor-point and the rawhide is knotted with one or two half-hitches.

Allow the rawhide to dry for a couple of days. Then apply a mixture of two parts boiled linseed oil and one part turpentine. Let the oil mixture dry for at least a week. The seat will be finished with spar varnish (thinned 12% with painter thinner/mineral spirits).

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

April 21, 2025

A Restorers’ Guide to the Chestnut Pal (16′ Wood-Canvas Pleasure Canoe)

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

If you are preparing to restore your wood-canvas canoe – especially in Canada – you are often looking at a canoe built by the Chestnut Canoe Company based in New Brunswick from 1897 to 1978. Of the many models produced over the years, the 16′ Pleasure Canoe was one of their best sellers. It had a variety of names and the hull shape changed as well over the course of eighty years. However, this canoe is most commonly referred to as the Chestnut Pal.

The dimensions of the components that make up the Pal are often the same as those found in many other Chestnut (and Peterborough) canoe models – including the famous Chestnut Prospector. As a result, if you have these dimensions, you can use them to restore about thirty different canoe models. So, here is a restorer’s guide to the Chestnut Pal.

This Chestnut pleasure canoe is from around 1952. The telegraph code was Ajax. It was 16′ LOA and had a 34″ beam.

The 16’ Pleasure Canoe from the Chestnut Canoe Company had a number of incarnations over the years. From the early 1900’s until 1953 it had a 34” beam, its ribs were 1.5” wide and was called the Ajax. Then the beam was widened to 36” and it was called either the Pal (1954 – 1978) or the Deer (1965 – 1978). Through the later years, the ribs were either 1.5” wide or 2-3/8” wide.

One little note here: I am listing all of the dimensions in inches. I apologize to all of you who are working in metric. The canoes were built with imperial measurements originally, so I find it easier and more accurate to stick with this measurement scale.

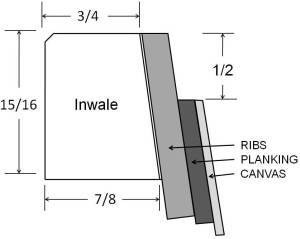

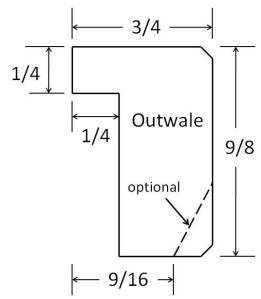

Inwales –The inwale is a length of ash 15/16” high. It is fashioned to fit the tumblehome present on most Chestnut canoes. Therefore, the top surface is ¾” wide while the bottom width is 7/8”. The last 15” or so at each end is tapered down to about 5/8” wide along the sides of the decks. All of the transverse components (thwarts and seats) are attached to the inwales with 10-24 (3/16”) galvanized steel carriage bolts. I replace these with 10-24 silicon-bronze carriage bolts.

Outwales – The outwales are also made of Ash. Depending on when the canoe was built, the outwales may have a chamfered edge on the bottom of the outside surface. Water often gets trapped under the outwales and results in rot on the inside surface. Therefore, I usually end up replacing this component and I make sure I seal all of the surfaces with shellac and varnish before installing the outwales. The sheer-line of Chestnut and Peterborough Pleasure Canoes turns up sharply about 18” from the end. As a result, it is necessary to soak, heat and pre-bend new inwales and outwales over custom-built forms to make the ash fit the upswept sheer-line.

It is also worth noting that both the inwales and outwales were very often made by joining two pieces together with a 9″ scarf joint to create the full length Ash required. Apparently, it was difficult to get full length Ash even in the 1960′s.

Decks – The decks were made of hardwood – usually maple, ash or oak. By the time you start restoring your canoe, the decks are often rotted along with the stem tops and inwale ends. They are attached to the inwales with six 2” #8 bronze wood screws. The deck extends about 15” into the canoe from the end.

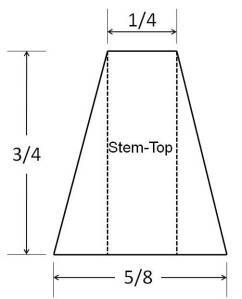

Stem-Top – You will rarely if ever have to replace the entire stem. However, I rarely see an original stem-top that is not partially or completely rotted away. Because the top 6” or so of the stem is straight, you can usually make the repair without having to pre-bend the wood to fit the original stem-profile.

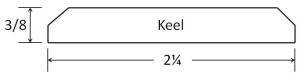

Keel – If you want to keep the shoe keel as part of the canoe, it is a simple piece to make. Use a piece of hardwood (the original was ash) and taper each end to 3/8” wide. The overall length is about 14’. It will accept the brass stem-band which is 3/8” wide.

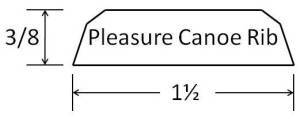

Ribs – The Chestnut Pleasure Canoes were constructed with either the regular 2-3/8″ wide ribs or the narrow 1½” wide ribs. Both of these rib types are 3/8″ thick.

The edges of the narrow ribs are chamfered 18° on both sides with the top corners rounded off slightly. The edge of the regular rib closest to the centre of the canoe has tapered ends (11° chamfer) while the edge closest to one end of the canoe is chamfered about 30°. The chamfer angles varied over the years, so you will have to use the original ribs in your canoe as templates. There are 2” spaces between the regular ribs and 1½″ spaces between the narrow ribs.

Planking – The planking in Chestnut Canoes was made of either Eastern White Cedar or Western Red Cedar. They started out being 5/32″ thick, but were often sanded down from there. I often have to pass new planking through the thickness planer to match the thickness of the original planks.

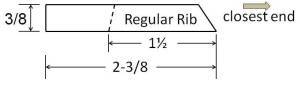

Seats – The seat frames are made of ¾” hardwood (ash, oak or maple) 1½” wide and hand-woven cane (rattan) seats. Both seats are suspended under the inwales with 10-24 carriage bolts and held in position with 5/8” hardwood dowel. The rear stern seat dowels are 1¾” long while the front dowels are ¾” long. All of the bow seat dowels are ¾” long. Again, this varied over the years. When installing seats, I tend to use 1¾” spacers for the bow seat. The stern spacers are then 1¾” and 2¾”. This adds a noticeable degree of stability to the canoe. The forward edge of the bow seat is 58” from the bow end of the canoe while the forward edge of the stern seat is 38½” from the stern-end of the canoe.

Thwarts – The thwarts are made of ¾” hardwood (ash, oak or maple) that is 2½” wide. They taper from the centre to create hand-grips on either side that are 2” wide. They were attached directly under the inwales with galvanized steel 10-24 carriage bolts. Usually, the original carriage bolts are corroded and must be replaced. I use 2″ 10/24 silicon bronze carriage bolts. The stern-quarter thwart is positioned 67” from the stern end of the canoe while the centre thwart is positioned 96” from both ends.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.