Mike Elliott's Blog, page 4

September 23, 2024

How to Repair a Long-Framed Veneer Deck in an Antique Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Note: If you happen to be a master cabinet-maker who repairs Chippendale furniture for fun, this project will be pretty straightforward. For the rest of us, it is a supreme challenge. Many of my adventures in repairing fancy canoes employ a trial-and error methodology. In this project, I used the error-and-error method. As I take you through the process, I describe some of the pitfalls I encountered. I hope this helps you avoid some of them.

***********************

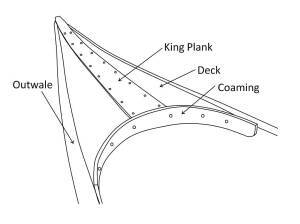

Long decks are found in both wood-canvas canoes and all-wood canoes. They are comprised of a number of components. Most often, the deck itself is two pieces butted together down the centre-line. The king plank covers this joint while the coaming covers the end grain of the deck and king plank.

These decks were made in one of two ways. The first method, already described in a previous blog article, is to pre-bend solid wood for the deck to fit the graceful curves in the ends of the canoe.

The second method is to build a frame at each end and cover it with thin veneers (usually two pieces of mahogany). The king plank covers the joint between the deck veneers while the coaming covers the frame as well as the end-grain of the deck veneers and king plank.

Some companies built the frame directly into the structure of the canoe and installed the veneers afterwards.

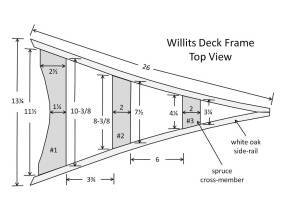

I repaired the stern deck in a 1948 Willits Brothers canoe. In their shop, they installed the framed deck after it was fully assembled.

The first step is to remove the deck from the canoe. Start by removing the coaming. It is held in place with six #8 brass flat-head wood screws. Set it aside to be re-installed near the end of the repair process.

The king plank is attached with ¾” (19 mm) 18-gauge brass escutcheon pins. They are dubbed (bent over) at the back of the deck. Ease them out by working a putty knife between the king plank and the deck. Then, wedge a small pry bar between the putty knife and the deck.

Working gently along the length of the king plank, gradually work it free from the deck as the brass pins straighten.

The deck veneers are attached with ¾” (19 mm) #6 brass flat-head wood screws (under the king plank) and ¾” (19 mm) 18-gauge brass escutcheon pins driven into the white oak deck frame along the outer edge. Use the same method to lift the veneers off the frame. Some of the brass pins will probably pull through the veneer and remain in the oak frame. Remove them with a pair of bonsai concave cutters.

With the frame exposed, it is clear that the white oak side rails in this frame are rotted at the ends.

The outwales are attached to the deck by means of several #8 brass flat-head wood screws. Remove them to expose the hull. The main body of the outwales are attached to the hull from the inside with ¾” (19 mm) 16-gauge copper canoe nails. Remove a few of these with a pair of bonsai concave cutters to provide full access to the canoe hull in the region where the frame is attached to the hull.

Clamp a pair of vice grips to a hack saw blade to create a strong handle. Work the blade between the deck frame and the hull of the canoe to cut through a number of ¾” (19 mm) 16-gauge copper canoe nails used to attach the frame to the canoe.

Remove the frame from the canoe.

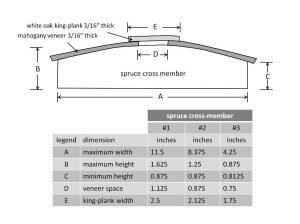

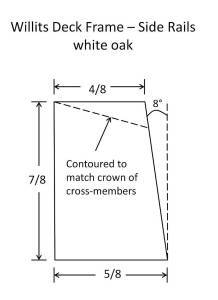

The side rails of the frame are white oak while the cross members are spruce. This particular frame requires new side rails.

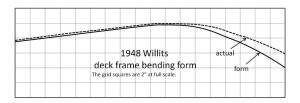

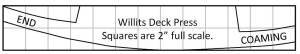

New white oak stock is cut wide enough to create both rails from a single piece once it is bent to the correct shape. A bending form is created that is 3″ (76 mm) wide.

The oak stock is soaked for three days, steamed for 60 minutes and bent onto the form without a backing strip. Let the wood dry for a week.

Once removed from the bending form, saw the new stock into two pieces on the table saw and cut to rough dimensions. The left and right frame rails are mirror images of each other. Be sure to label them to avoid errors further on in the process. Line up the new pieces with the original rails and mark them out for later fitting.

Remove the original rail on one side and install the new piece.

Align a straight edge down the centre-line of the frame and mark the end of the new piece.

Use a dovetail saw or Japanese crosscut saw to cut just outside the line.

Remove the original rail on the other side. Dry-fit the new piece and mark the angle for the end of the frame. Cut on the outside of the line, dry-fit the new piece and make adjustments until the rails fit together properly at the end. Install the second rail and secure them together at the end with a ¾” 16-gauge bronze ring nail.

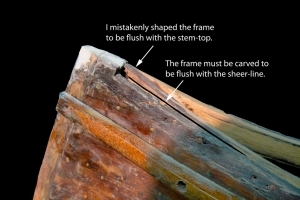

Dry-fit the deck frame in the canoe and hold it in place with several spring clamps. Trim the end to fit and carve the final shape of the side rails until they are flush with the sheer-line of the canoe. This step is critical to the final fit of the deck. In a solid-wood deck, the shape can be fine-tuned after it is installed. In a veneer deck, the frame must be shaped precisely before anything else is done.

I found this out the hard way. The first time I dry-fit the frame, I shaped the end to be flush with the stem-top. This was about 3/16″ (5 mm) higher than the sheer-line of the hull.

When I went to install the finished deck, the assembled end rose above the stem-top and did not fit properly. I had no choice but to take the entire thing apart and carve the frame to be flush with the sheer-line.

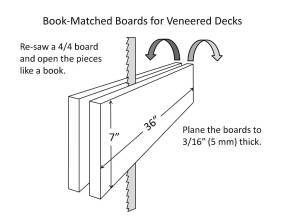

The Willits brothers book-matched their veneers for the decks. They re-sawed a 4/4 (1″ or 25 mm thick) board on a band saw and opened the pieces like a book. The veneers were planed to 3/16″ (5 mm) thick.

Use a mahogany board 7″ (18 cm) wide and 36″ (91 cm) long. Once the boards are re-sawn and planed, use the original veneers as templates. Mark out oversized pieces and cut them to rough shape. Be sure to cut well outside the lines. You want to have lots of room for fitting and trimming to final size.

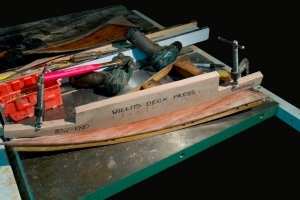

Make a veneer press jig with 4/4 hardwood.

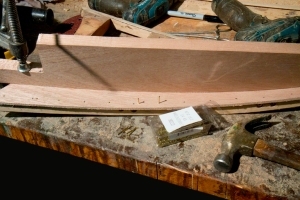

Soak the veneers for at least four hours. Take one of them and pour boiling water over it. Press the veneer into place and use the veneer jig (locked in place with a couple of C-clamps) to act as another pair of hands while you secure the veneer with fasteners. Be sure the veneer extends at least 1″ (25 mm) past the outside edge of the frame.

Drill pilot holes in the spruce cross members #2 and #3.

Attach the veneer with ¾” (19 mm) #6 bronze flat-head wood screws close to the edge nearest the centre-line.

Reposition the veneer jig to allow full access to the outer edge of the deck. Drill pilot holes through the veneer and into the frame rail at 1½” (38 mm) intervals.

Use a small, flat-head tack hammer to drive ¾” (19 mm) 18-gauge brass escutcheon pins into the veneer. I started with my regular canoe tack hammer which has a large, domed face. I switched over to the small, flat-faced hammer after mis-hitting several pins and bending them. The Willits brothers countersunk these pins and filled the holes with wood putty. I opted to skip this step after my counter-sink slipped and split the veneer (not once, not twice, but three times before I tore off the veneer and started again). This process offers no end of challenges, the least of which being the fact that the drill bit is 3/64″ (1.2 mm) diameter and the holes are drilled free-hand. If you are anything like me, you will need at least one more drill bit than you have on-hand (I used six drill bits to attach six veneers and two king planks).

If your fingers are as big and clumsy as mine, use a pair of forceps to hold the pin while you hammer.

Once the veneers are attached, dry-fit the deck. Mark the end of the veneer so the deck fits back into its original position. Trim the ends of the veneer and dry-fit the deck again. If you have done everything right so far, the top of the veneer will be flush with the stem-top.

Mark the outside edge of the canoe hull on the underside of the veneer. Remove the deck and carefully shape the veneer to just outside the line. Repeat the process of dry-fitting, marking and shaping until the veneer fits precisely.

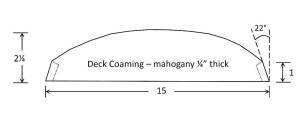

Use a random-orbital sander to shape the end-grain veneer until the coaming fits precisely. This too, is a slow process of shaping and dry-fitting the coaming in small, careful steps. The veneer is extremely delicate and prone to breaking (especially at the corners). I switched to a fine rasp as I got closer to the final fit.

Sand the veneer by hand from 120-grit to 220-grit. Wet the veneer surface and let it dry. This will raise the grain. Sand by hand from 320-grit to 600-grit. Use a tack cloth to remove lingering dust once the sanding is complete.

Stain the veneer to match the original wood in the canoe.

Prepare a piece of white oak for the king plank. Sand it to 600-grit and stain the wood to match the original. Seal all of the frame components with shellac (2-pound cut using lacquer thinner instead of methyl hydrate). Then apply a coat of spar varnish (thinned 12% with paint thinner). Allow the varnish to dry for a couple of days before proceeding to the next step. Press the king plank into place and use the veneer jig to hold it in place while you secure it with escutcheon pins.

Drill pilot holes and hammer escutcheon pins at 2″ (50 mm) intervals.

Use a clinching iron to dub the pins at the back of the deck.

Dry-fit the deck in the canoe. If you have done everything right so far, the king plank sits snugly on top of the stem-end.

Attach the coaming to the deck with ¾” (19 mm) #6 bronze flat-head wood screws.

Install the completed deck and secure it with ¾” (19 mm) 16-gauge copper canoe nails.

Re-attach the outwales with #8 bronze flat-head wood screws. Spray the screws with a little WD-40 to reduce heat build-up as they are driven in. Hot screws are more likely to break off as they are driven tight.

Use a Japanese cross-cut saw to trim the king plank flush with the outer edge of the stem.

Smooth the corners of the king plank at the end with a rasp.

All’s well that ends well.

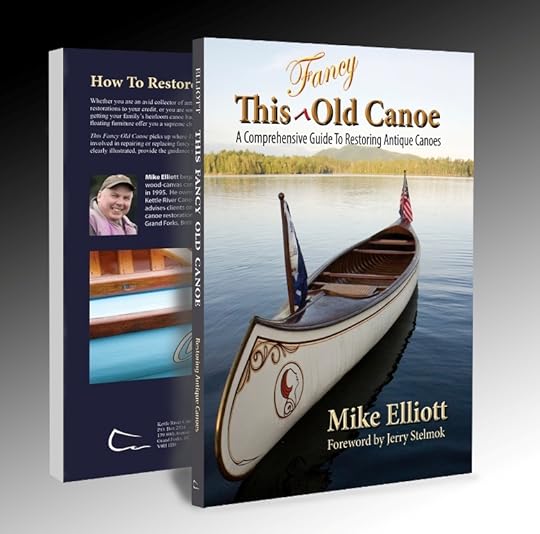

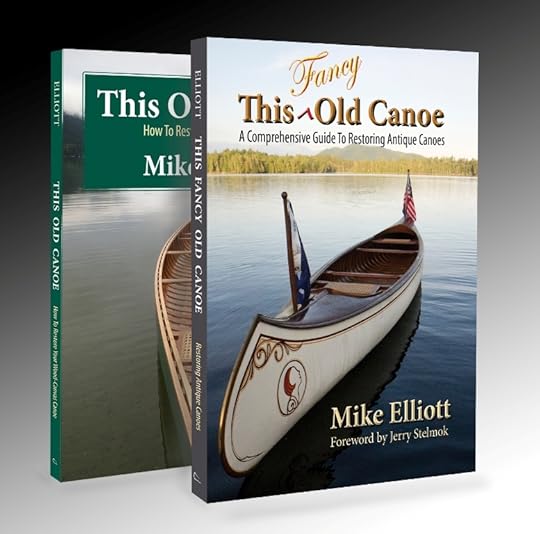

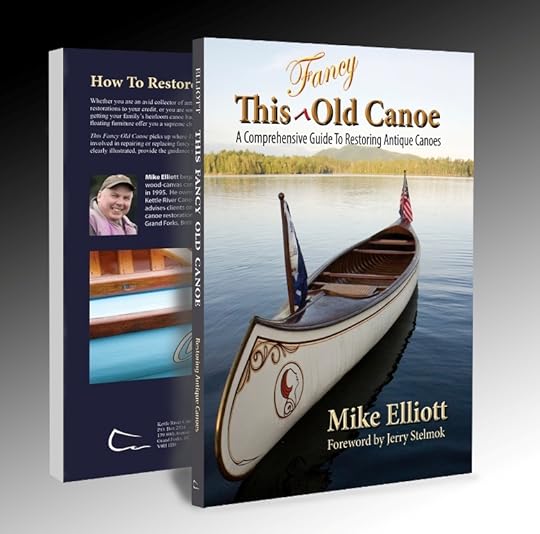

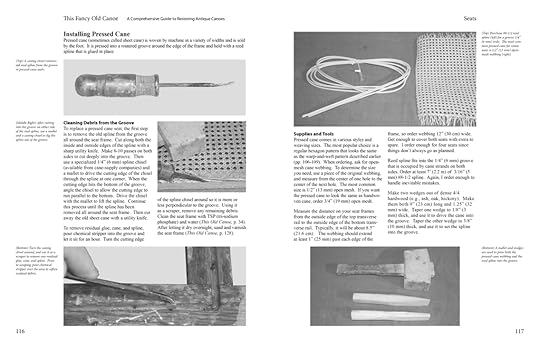

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring Antique Canoes.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

September 17, 2024

Jerry Stelmok Introduces This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide To Restoring Antique Canoes

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

The foreword to This Fancy Old Canoe is written by Jerry Stelmok. Here is his introduction to the book.

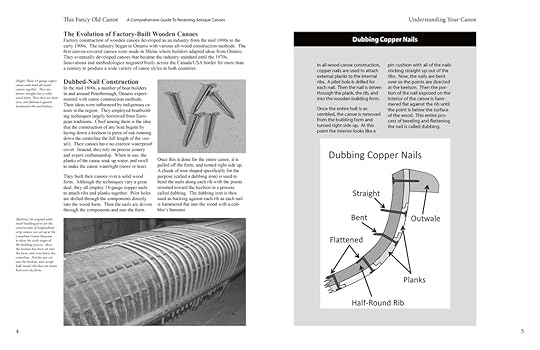

In this, Mike Elliott’s second book on canoe restoration, he uses his first book, This Old Canoe, which treats the more commonly encountered types of canoe damage and repair — broken and rotted ribs, planking, gunwales, need for recanvassing, and such — as a springboard to address some of the less common and often more challenging afflictions found in certain antique (and I’ll use Mike’s appropriate term) fancy canoes.

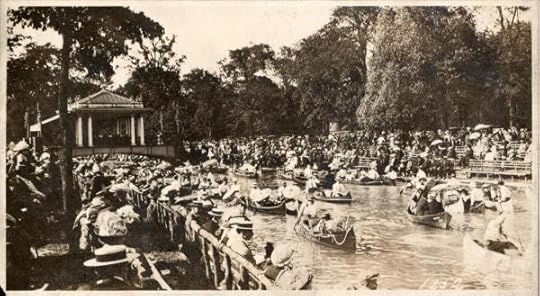

In the late nineteenth and early third of the twentieth centuries, recreational canoeing became very popular. Not just to explore the backcountry but as a social phenomenon giving rise to large-scale urban canoe clubs and liveries. On a Sunday afternoon on rivers such as the Charles in Boston, and the Detroit’s Belle Isle section, hundreds of canoes might be packed cheek by jowl ferrying sociable paddlers decked out in their finest outfits. These flotillas blossomed not only because they were fun and a chance to show off canoes, but also because they were one of the few acceptable activities where a fellow could be accompanied by his special girl unchaperoned — aside from the thousand or so other canoeists in proximity.

As an expression of this high-visibility exposure, the canoeing public began demanding finer, more strikingly adorned canoe models with more “flare.” Not merely fancy paint jobs, but higher, more romantic sheer lines, long decks leading to open cockpits with coamings, pennant holders, etc.

The builders responded. From the 1890s through the 1930s, with great skill and attention to detail, they employed extreme steam-bending of gunwales, stems and decks, to achieve the desired romantic flavor. Among these builders were Robertson, Brodbeck, and Arnold, in the Boston region. In Maine, they included Williams and Heckman in Kennebunk, Morris in Veazie, and Old Town in Old Town.

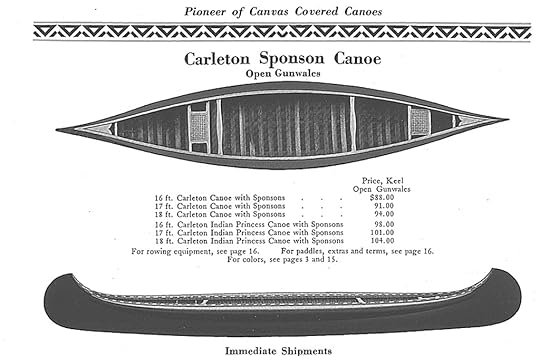

To make the canoes practically capsize proof, hollow air chambers termed sponsons were installed beneath the gunwales on some models.

All these extraordinary features present challenges that require innovative restoration procedures when they turn up as broken, dry rotted, or missing components in antique canoes to be repaired.

Mike breaks down these issues into various categories. With detailed instructions and clear photographs, he describes how to go about fixing the problems at hand.

It has been said that there’s more than one way to skin a cat. I’ve never skinned a cat, and never plan to. I like cats, although maybe not as much as I do dogs. The point is that, in my years of experience, I don’t necessarily employ the same techniques as Mike does for each task. Nor does the fellow down the road from me, Rollin Thurlow, who has been at canoe building/restoration as long as I have. He has also developed his own skills and methods. (But then, our town of Atkinson, Maine, is just possibly unique in that it has a full-time canoe shop for every 150 residents.) The late great Jack McGreivey of New York, considered by many of us to be the Dean of canoe restoration, had developed his own methods of tackling these challenges, too. Simply put, there is no single correct solution to address these often-complex issues. Mike freely points this out. His own methods are straight-forward and offer directions that, with care and some skill, should lead to success.

An important section of the book that I find very interesting is the restoration and repair of the various all-wood canoes manufactured in the Peterborough-Lakefield region of Ontario. Builders such as Herald and Stephenson, as early as the 1860s, made many types. These differ from the wood and canvas canoes in that their wooden hulls had to be perfectly watertight without a waterproof skin. I have very little knowledge about restoring such canoes, but I have always been impressed with their artisanship and the obvious challenges they present. Mike takes on a few of these himself and widens the book’s scope with excellent contributions from Sam Browning in the UK, who shares his experience restoring these impressive watercraft. Such is the value of the internet in all its forms when it is employed as it was initially intended — for sharing information.

Of course, numerous posts on the various apps and services these days offer advice. Some are excellent and some are sketchy. Some that are dependable are the Forums on the website of the Wooden Canoe Heritage Association (forums.wcha.org).

Still, when confronted with an exquisite courting canoe in need of major restoration; or just a more ordinary canoe that has issues with those unwieldy sponsons, you will find nothing quite as accessible and reassuring as a credible book on your bench. That is why This Fancy Old Canoe can be your best place to start.

Jerry Stelmok

Atkinson, Maine

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring Antique Canoes.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

September 9, 2024

New Book Available! This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring Antique Canoes

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

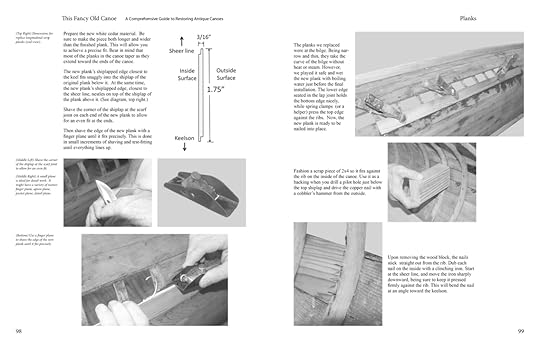

This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring Antique Canoes picks up where This Old Canoe: How to Restore Your Wood-Canvas Canoe left off. Whether you are an avid collector of antique canoes or you have limited woodworking experience and just want to get your family’s heirloom canoe back on the water, the two books work together to provide the techniques necessary to achieve success in your canoe-restoration adventure.

Repairing antique canoes can be a supreme challenge because their artisans built them with beauty and longevity in mind. Using over 400 photos and more than 100 plans and illustrations, This Fancy Old Canoe is designed to simplify the restoration process, guide you through it, and provide a measure of clarity to these complex tasks.

The book covers every aspect you may encounter in fancy old canoes, including:

identifying your canoe and understanding its constructionreplacing and weaving cane seatsreverse engineering highly curved endsremoving and installing pocketed inwales, wide outwales, and sponsons (air chambers attached to the sides of the canoe)repairing sailing rigs and floor systemsapplying fancy hand-painted designssourcing materialsa guide to the Old Town Canoe Company and their wood-canvas canoesdiagrams and specifications for component parts of the Old Town Otca

Many antique canoes, built in the Peterborough region of Ontario, Canada, are all-wood construction. They do not have a canvas cover. Instead, they rely on precise joinery to create a water-tight hull. This Fancy Old Canoe describes how to repair and replace every component in these elegant examples of floating art.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring Antique Canoes.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

September 5, 2024

A Restorers’ Guide to a Chestnut Bobs Special Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

The blogs I do on the specifications of canoe components for various types of canvas-covered canoes seem to be quite popular. Apparently, I am the only one out there taking the time to write about this stuff and share it with others online. This time around, I am presenting a restorers’ guide to the Bobs Special from the Chestnut Canoe Company.

This canoe was one of two lightweight pleasure canoes built by Chestnut (the other was an 11’ solo canoe called the Featherweight that weighed about 38 pounds). Before I talk about the canoe, I’d like to clarify the name. According to Roger MacGregor in his book When the Chestnut was in Flower, Henry and William Chestnut were real history buffs. The telegraph code for the 15’ 50-Lb. Special was BOBS and made reference to Lord Frederick Roberts, a major figure during the Second Boer War in South Africa. Over the years, as this wide, light-weight canoe became more difficult to keep under the weight limit of 50 lbs. (the average weight was 58 pounds while the carrying capacity was 700 pounds), they changed the name. I have seen a variety of Chestnut catalogues call it Bob’s Special, Bob Special and Bobs Special. So, take your pick.

If you happen to have a Bobs or have been lucky enough to come across one in need of some TLC, you will notice what a sweet little canoe this is. It paddles like a dream which is surprising for a canoe that is 37” (94 cm) wide. Its bottom has a shallow-arch that reduces the waterline width when paddled with a light load. There is a fair amount of rocker in the ends which adds to its maneuverability. At the same time, it is not difficult to stand up in a Bobs – making it ideal for fly-fishing or general recreational paddling for a less experienced paddler.

One little note here: I am listing all of the dimensions in inches. I apologize to all of you who are working in metric. The canoes were built with imperial measurements originally, so I find it easier and more accurate to stick with this measurement scale.

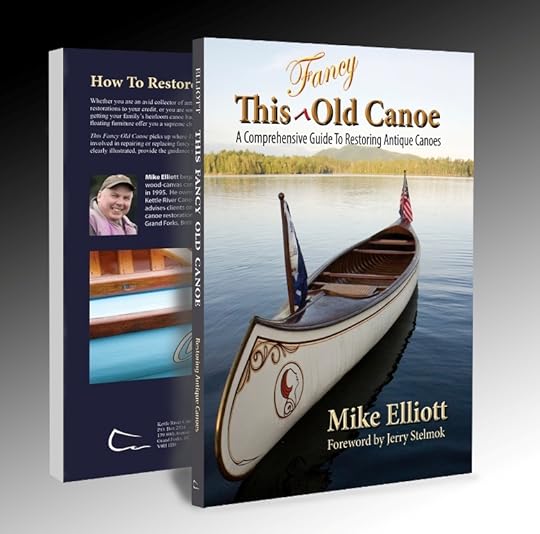

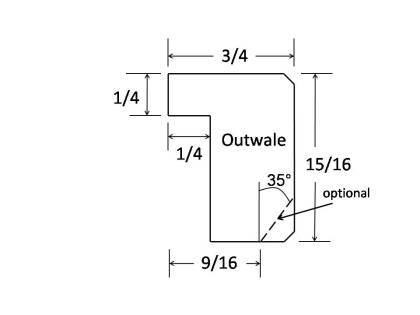

Inwales –The inwale is a length of White Ash or Douglas Fir 15/16” high with the edge grain visible on the top surface. It is fashioned to fit the tumblehome present on most Chestnut canoes. Therefore, the top surface is 9/16” wide while the bottom width is 11/16”. The last 18” or so at each end is tapered down to about ½” wide (top and bottom) along the sides of the decks. All of the transverse components (centre thwart and seats) are attached to the inwales with 10-24 (3/16”) galvanized steel carriage bolts. I replace these with 10-24 silicon-bronze carriage bolts.

The gunwales (both inwales and outwales) are pre-bent about 18” from the ends. If you are replacing these components, the wood will have to be soaked for 3 days, heated by pouring boiling water over them and bent onto custom-built forms in order to get a proper fit.

Outwales – The outwales are also made of White Ash or Douglas Fir. Depending on when the canoe was built, the outwales may have a chamfered edge on the bottom of the outside surface. Water often gets trapped under the outwales and results in rot on the inside surface of the originals because they assembled the canoe first and then applied paint and varnish. Consequently, the inside surfaces of the outwales are bare wood. Therefore, I usually end up replacing this component. Prior to installation, I seal the wood on all surfaces with a couple of coats of spar varnish. Unlike the original builders, I do all of the painting and varnishing first and then assemble the canoe.

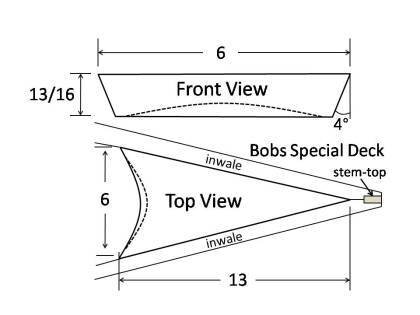

Decks – The decks the Bobs Special were made of hardwood – usually maple, white ash or white oak. Sometimes, they used mahogany to help reduce the overall weight. By the time you start restoring your canoe, the decks are often rotted along with the stem-tops and inwale-ends. They are attached to the inwales with six 1¾” #8 bronze wood screws. As with the outwales, I help prevent future rot by sealing the decks on all surfaces with a couple of coats of spar varnish. The deck extends about 18” into the canoe from the end.

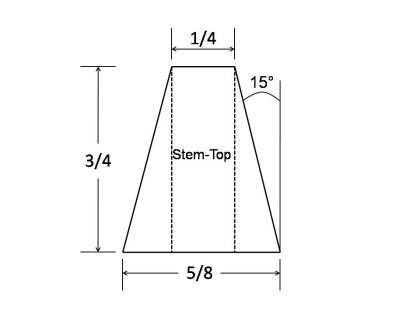

Stem-Top – You will rarely if ever have to replace the entire stem. However, I rarely see an original stem-top that is not partially or completely rotted away. Because the top 6” or so of the stem is straight, you can usually make the repair without having to pre-bend the wood to fit the original stem-profile.

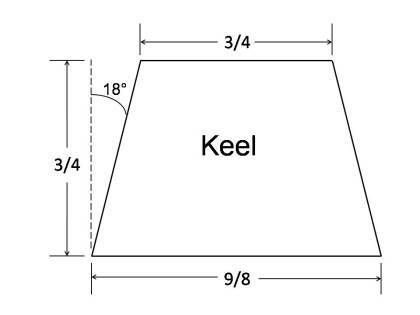

Keel – The Bob Special had a regular (tapered) keel installed. Use a piece of hardwood (the original was ash) and taper each end to 3/8” wide. The overall length is about 13’. It will accept the brass stem-band which is 3/8” wide.

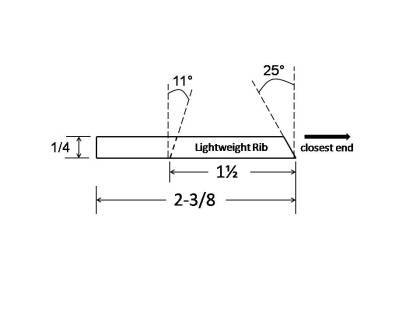

Ribs – The Bobs Special was constructed with so-called “regular” ribs (2-3/8” wide) that were ¼” thick instead of the normal 3/8”. They create a light-weight canoe but are not as robust as the regular ribs. You will probably encounter several broken ribs in your canoe restoration.

The edges of the ribs are chamfered in most Bobs Specials. Replicate the angles found in your canoe. Often, the edge closest to the centre of the canoe has tapered ends (11° chamfer) while the edge closest to one end of the canoe is chamfered about 25°.

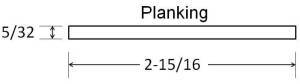

Planking – The planking in Chestnut Canoes was made of either Eastern White Cedar or Western Red Cedar. Although the planks started out at 5/32” thick, you will probably be shaving replacement planks down to match the original planks. Again, this results in a lighter, less robust canoe. You will probably encounter many broken planks in your canoe.

Seats – The seat frames are made of ¾” ash, oak or maple that is 1½” wide. Both seats are suspended under the inwales with 10-24 carriage bolts and held in position with 5/8” hardwood dowel. The rear stern seat dowels are 1¾” long while the front dowels are ¾” long. All of the bow seat dowels are ¾” long. The forward edge of the bow seat is about 51½” from the bow-end of the canoe while the forward edge of the stern seat is about 39½” from the stern-end of the canoe.

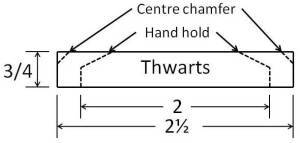

Centre Thwart – The thwart is made of ¾” ash that is 2½” wide. It tapers from the centre to create handle grips on either side that are 2” wide. They were attached directly under the inwales with galvanized steel 10-24 carriage bolts. As with every component in the canoe, I seal the entire thwart with a couple of coats of spar varnish prior to installation and replace the original galvanized steel bolts with silicon bronze bolts.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

September 4, 2024

How to Remove Fiberglass from a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

For those of you new to this blog and have not heard me on this topic before, let me be as clear as I can be: To anyone thinking about applying fiberglass to a wood-canvas canoe, I say, “DON’T DO IT!” To anyone wanting to remove fiberglass from a wood-canvas canoe, the short answer is: HEAT.

Wood-canvas canoes are a product of a by-gone era; a time before planned obsolescence — when things were built with the long term interests of the consumer in mind. The whole idea of building a canoe with wood and canvas was to have a vessel that lives and breathes. These canoes work in the natural environment and are part of it. They are held together with tacks and screws – no glue. The wood flexes and moves with the water around it. When part of the canoe breaks or rots, it can be repaired or replaced with comparative ease because it is designed to be taken apart and rebuilt. As long as there are people who know how to restore canvas-covered canoes, they will live forever.

It has been about forty years since these canoes were the standard in the marketplace. Not only has the technology of wooden canoe repair faded into obscurity, but the mindset of both manufacturers and consumers has also changed. Synthetic materials are now generally seen as better – easier, tougher and longer lasting. The consumer has been convinced that the new materials can improve that which is outdated or at least maintain it quickly and easily.

When it comes right down to it, wooden canoes and fiberglass just don’t mix. Since the ribs and planking are held together with tacks, they flex and move naturally. Over the years, the tacks tend to work loose and eventually have to be either re-clinched or replaced. Conversely, fiberglass resin is rigid. Once applied, it tends to resist any movement. The combination of a flexible hull and a rigid outside layer results in cracked or delaminated resin. The tacks can also wear against the resin from the inside to the point where they come right through the resin. It can take several months or several decades, but at some point the canoe needs to be repaired and the fiberglass has to come off. It is then that the real problem comes to light. All of that synthetic resin has to be removed. It is a long, painstaking process that usually has you cursing the person that put the stuff on in the first place. The moral of the story is: Avoid applying fiberglass to the hull of a wood-canvas canoe. Learn how to re-canvas the canoe or find a professional to do it for you.

This leads us into the next question: How do you remove fiberglass from a wood-canvas canoe? All you require is a professional-grade heat-gun, a 2” putty knife, a pair of pliers, safety equipment (work gloves, safety glasses and a respirator mask) and lots of patience. The first step is to move the canoe into a well ventilated work space – preferably outdoors. Then start at an edge of the canoe and apply heat to the resin.

At this point it is important to note that fiberglass resins come in two basic types – polyester and epoxy. Polyester resins were the first to be developed. If your canoe had fiberglass applied to it in the 1970’s or earlier, you can bet that polyester resins were used. They tend to become brittle and deteriorate rapidly, so if the fiberglass on your canoe is delaminating it is most likely that you are dealing with a polyester resin. Fortunately, this makes the removal of the fiberglass relatively quick and easy. In many cases, the cloth can be ripped off by hand with very little need for heat. When I say rip, please be gentle. If you get carried away and pull at the fiberglass cloth too rapidly, you could end up tearing sizeable chunks of planking off the canoe as well (I speak from first-hand experience).

Epoxy resins hit the market in a big way in the 1980’s and are the standard today. They are applied by first mixing a hardener with a resin in a two-part formula. What results is a strong, tough plastic that bonds very well to wood. Unfortunately, this means that the removal process is arduous and painstaking.

As mentioned earlier, start at an edge of the canoe and apply heat to the resin. If you are dealing with epoxy resin, you will probably have to apply the heat for several minutes before the cloth begins to respond to your attempts to lift it with the putty knife. At some point, it does let go and the fiberglass cloth can be separated from the canoe. Then move a few centimeters and continue the process. Again, polyester resins let go fairly quickly. You will find that large sheets of cloth come off in fairly short order. I usually grab the cloth with a pair of pliers rather than with my hand. Even with work gloves on, the pliers prevent nasty encounters with heat and/or sharp edges of fiberglass (again, this is the voice of experience talking).

Once all of the fiberglass cloth is removed, return to the canoe hull with the heat gun and a putty knife. Apply heat to any patches of resin still stuck to the wood. Then, scrape the resin off. Be prepared to settle into hours of tedious work. It typically takes 15 to 20 hours to remove the fiberglass cloth and resin from a 16′ canoe.

Once you are back to the bare wood, the restoration is like that of any other wood-canvas canoe. So, enjoy the pleasures of life in the slow lane, stay away from fiberglass and celebrate the fact that you have a wood-canvas canoe.

Many people complement me on the great fiberglass job on my canoes. They are shocked to learn that the canoes are covered with painted canvas.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

September 3, 2024

How To Make Highly Curved Stems for a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

During the restoration of a wood-canvas canoe, it is rare to have to replace the entire stem in the canoe. However, when faced with the restoration of a canoe which is more than 100 years old, a new stem (or two) is more than likely going to be part of the project.

I restored a J. H. Rushton Indian Girl canoe (c. 1905). Both stems had extensive rot and one was broken in two places. Rushton made his stems from a solid piece of rock elm. Since this wood is nearly extinct now (thanks to Dutch Elm Disease), I used straight-grained ash 1″ (25mm) thick (at the lumber yard this is referred to as 4/4 ̶ pronounced four-quarters).

The first step is to remove the stems from the canoe. I use both a tack remover and a Japanese concave cutter bonsai tool to remove the fasteners without doing too much damage to the ribs, planks and stems in the canoe.

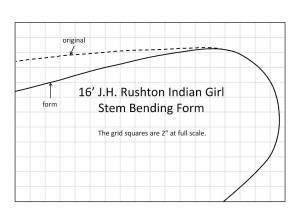

The next step is to create a bending form. Here, I present the dimensions of the bending form required for the Rushton Indian Girl.

It is comprised of three layers of 5/8″ (16mm) plywood. I ask my local building supply centre if they have any damaged sheets of plywood. I can get all of the wood I require for a fraction of the cost of full sheets of plywood. All three piece have the same curve but the centre piece of plywood has a longer base which clamps easily into a work-bench vice.

I start by placing the original stem on one piece of plywood and drawing the inside curve of the stem onto it.

I then keep the stem-top in the same location as the original while rotating the stem until the curve is about 3½” (9cm) greater than the original. The form shape is then drawn onto the plywood and is extended about 6″ (15cm) at both ends to accommodate the clamping system.

The form shape is cut with a saber saw or band saw. The first piece is then used as a template for the other two pieces. Once assembled, the form is sanded more or less square with a belt sander or an angle grinder set up with a 24-grit wood grinding disk. The final form is 1.875″ (48mm) wide.

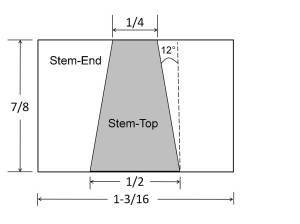

The base-end of the stem is 1.1875″ (30mm) wide and 0.875″ (22mm) thick. I bend a piece of ash which is 1¼” (32mm) wide and 1″ (25mm) thick. This allows me to shape an exact replica of the original.

The clamping system is attached to the bending form with enough space for the new wood and a backing strip. The new stem stock is soaked in water for four days, steamed for 60 minutes and bent onto the form where it remains for at least a week. When removed from the form, the new wood will spring-back slightly and ought to come to the same shape as the original (or close enough).

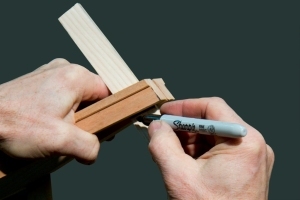

The original stem is much more than just the curve in its profile. It is tapered at the stem-end, angled to accept planking and notched to accept ribs. Draw the rough dimensions and contours onto the new stem (first with a pencil and then with a permanent ink pen).

Use a Japanese cross-cut saw or a dovetail saw to cut the sides of the rib notches at the correct angles and depths. Use a wood chisel and mallet to remove the bulk of the material in each notch.

Check the dimensions of each notch on the original and use the chisel to shave each new notch to the desired thickness.

Use an angle grinder set up with a 24-grit wood sanding disk to carve the desired angles and tapers into the new stem.

Work slowly and carefully with a random-orbital sander and 60-grit sandpaper (checking dimensions with calipers against the original) until the new stem is an exact replica of the original.

Turn the canoe upside down and use spring clamps to hold the new stem in place while you drill pilot holes for bronze ring nails to attach it to the ribs.

Use a cobblers hammer backed with a clinching iron to drive the ring nails tight.

Turn the canoe right-side up and sight down the center line. Position the stem so it is lined up straight down the center line and clamp it in place. Pre-drill holes for 16mm brass canoe tacks and attach the new stem to the original planks.

Mark the height of the stem-top against the underside of the inwale ends.

Use a Japanese cross-cut saw to trim the stem-top to its desired height. I cut it a little long and use a random-orbital sander to achieve a snug fit.

Attach the rest of the planking to complete the job.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

September 2, 2024

How to Paint a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Once the canoe has been canvassed, the filler has been applied and the keel and stem bands have been installed, it is ready for paint. Here are five secrets for a professional paint job:

Tip #1 – Paint First, Then Assemble – Fifty years ago, the canoe builders in the factories were in production mode. To save time and space, they installed the outwales before applying varnish and paint. However, this caused two problems in the years to follow. First, the canvas under the outwales is not protected with paint. Second, the inside surface of the outwales is bare, unprotected wood. Over years of use, water can become trapped under the outwales. This moist environment can be ideal for growing the fungi that cause rot.

Two things can happen: a) the canvas can rot under the outwales causing the canvas to detach from the canoe and; b) the outwales can rot from the inside out.

To avoid these problems, paint the canvas and varnish the outwales (being sure to seal all of the surfaces) before the outwales are installed. Some builders go so far as to apply varnish along the cut edge of canvas before the outwales are installed.

Tip #2 – Sanding, Sanding and More Sanding – Generally speaking, the more you sand, the smoother the final finish. Also, the more meticulous you are about sanding, the better the end results. Before starting to paint the filled canvas, sand the filler with 120-grit sandpaper. I use a random-orbital sander for this job.

Any tacks in the canoe hull that are not flush to the hull will show up as you sand. It is essential to stop sanding immediately and re-clinch the tack to avoid creating a nice, round, tack-sized hole in the canvas.

For all practical purposes, oil-based alkyd enamel paint is essentially heavily pigmented varnish. Both are handled in exactly the same way except that while the surface of varnish is scratched with steel-wool between coats, the paint surface is scratched with wet sandpaper. I use 120-grit wet sandpaper between the first and second coats of paint. I then use 220-grit wet sandpaper between the second and third coats and, if I decide to apply four coats of paint, I use 320-grit wet sandpaper between the third and fourth coats. As always, be sure to clean the surfaces well before applying the finish. Remove sanding dust with a brush or vacuum. Then, remove remaining dust with a tack cloth.

Tip #3 – A Little Thinner – Some articles about oil-based paints and varnishes would have you believe that avoiding streaks and bubbles in the final finish is one of life’s great challenges. In fact, there is no great mystery to it. Thin the paint (or varnish) about 12% with mineral spirits (paint thinner) before using it. The thinned paint will self-level once it is applied. The additional solvent also allows the paint to dry before sags and drips develop. For a canoe, any alkyd enamel works well and provides a tough, flexible finish. Recent changes to federal regulations in Canada make it difficult, if not impossible, to buy oil-based alkyd enamel. Just go to your local hardware store and pick up a gallon of oil-based alkyd enamel “rust paint” (Rustoleum, Tremclad or any store-brand). The label will say “For Metal Use Only”. I’m sure they just forgot to include “Canvas-Covered Canoe” in the label. I would gladly use a water-based paint for the canvas, but at this point, oil-based alkyd enamel is the only paint that works.

Tip #4 – Tip It, Then Leave It – As with any paint, you must maintain a “wet edge” while applying it to a large surface. Therefore, it is important to work in small sections of the canoe. Apply the paint quickly and vigorously to get complete coverage. Don’t worry about streaks or bubbles. Just make sure the paint covers the area without using too much. I use a high-quality natural bristle brush to apply the first and second coats.

I use a disposable foam brush to apply the third (and, if you so choose, the fourth) coat of paint. Once you have applied paint to a small section of the canoe, hold the brush at a 45° angle to the surface and lightly touch the brush to the wet surface. Move the brush quickly over the surface to “tip” the finish. Do this first vertically from top to bottom and then horizontally. After the section is painted and tipped in two directions, move to the next section. Continue in this way until you have done the entire canoe. Check to make sure there is no excess paint dripping anywhere – especially at the ends. Then, go away and leave it alone for 48 hours.

Tip #5 – Protect Your Work – Are we done yet? Well, that depends on whether or not you want to protect that beautiful new finish. Once I have applied the final coat of paint and allowed it to dry for two days, I apply a coat of carnauba wax (pronounced car-NOO-bah) obtained at the local auto supply shop.

Follow the directions and use lots of muscle (or a good buffing wheel). If you’ve never tried it, waxing the canoe is worth it just for the experience of shooting effortlessly through the water. It’s like waxing a surfboard – the results are amazing. Also, the paint is protected from minor scuffs and scratches. Any oil-based finish takes several months to cure completely, so the wax helps protect it in the early months of use.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

September 1, 2024

How to Install a Keel on a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Speaking strictly in terms of form and function, canoes and keels don’t belong together. Canoes are designed to sideslip easily in large, rapid rivers in order to avoid various obstacles along the way. However, wood-canvas canoes have often been part of the family for decades. In this context, they must also be seen through the lens of family history and tradition. Many wood-canvas canoes were built with a keel installed and that is the way the owner wants it to remain. For this reason, I have no problem re-installing a keel in a wood-canvas canoe.

Most keels were removed at the beginning of the restoration project and are being re-installed. Therefore, the first step is to clean it and remove old paint and bedding compound. This is usually a two-step process. I start with an angle grinder set up with a 24-grit sanding disk. This cuts through the worst of the old material and gets down to the original wood. Care must be taken in order to remove only the old paint and bedding compound. Finish the job with a random-orbital sander set up with 80-grit sandpaper. This removes any marks made by the grinder and creates a smooth surface for new bedding compound and paint.

Having just spent a lot of time and effort creating a waterproof canvas cover, it seems a little strange to then poke a dozen or more holes through the bottom of the canoe. It is essential, therefore, to use a bedding compound that seals the keel to the canoe, creates a waterproof barrier and stays flexible for decades.

Having tried a variety of products, I have returned to the old school. Dolfinite 2005N Natural Bedding Compound is a linseed oil-based compound with the consistency of peanut butter. It is the same as the bedding compounds used a century ago. Unlike more modern compounds (such as 3M 5200 or Interlux 214) it stays flexible for the life of the canvas (several decades), seals well, accepts paint well and yet allows the keel to be removed from the canvas if necessary some years down the line.

Most canoes use 1” (25 mm) #6 flat head silicon bronze screws combined with brass finish washers. Begin by driving one screw into each end of the canoe. Turn the canoe on its edge to allow access to the bottom of the canoe inside and out at the same time. This is where it is useful to have the canoe set up on two canoe cradles.

With one screw at each end, move to the outside of the canoe and line up each screw with the original holes in the keel. Use a permanent-ink marker to show the position of the keel on the canvas. Then mark the location of the screw where it comes through the canvas and mark the location of the screw hole on the side of the keel to facilitate attachment later.

Apply bedding compound generously to the keel with a putty knife. Any excess will be cleaned up later. For now, it is more important to ensure a good seal along the entire length of the keel. Then, open the original screw-holes at each end to make it easier to find them.

Not everyone has my “wingspan” – 79” (200 cm) from finger-tip to finger-tip – so not everyone can hold the keel in place with one hand and drive the screw with the other at the same time. Installing a keel is normally a two-person job. Get someone to line up the original holes in the keel with the screws coming through on the outside of the canoe while you drive the screws from the inside. Sometimes, the original holes in the keel have been stripped. In this case, use larger diameter 1” (25 mm) #8 screws to secure the keel. If the keel has warped a little, you may need 1¼” (32 mm) screws to draw it tight to the canoe. In this situation, especially with Chestnut and Peterborough shoe keels (3/8” thick), the screws may go right through the keel and poke out on the outer surface. That will be dealt with later.

Once both ends are attached, check to make sure that the keel is properly lined up with the center of the canoe. Once aligned, drive the rest of the screws along its full length. Usually, it is necessary to apply some pressure on the keel in order for the screws to catch properly. Sometimes, I need to get under seats to drive the screws. This is where a flexible drill extension comes in very handy. Most of the time however, I have removed the seats to refinish or re-cane them, so access to all of the screw-holes along the canoe’s centerline is not a problem.

Remove excess bedding compound from the edges of the keel and apply more to areas that are not completely sealed. Remove any bedding compound stuck to the canvas using medium steel wool soaked in lacquer thinner. Use a file to take care of any screw-tips poking through the keel. Finally, let the bedding compound cure for a few days before applying paint.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

August 29, 2024

How to Repair Loose Stem-Bands in a Wood-Canvas Canoe

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Wood-canvas canoes are works of art. However, in Canada, they are also working boats. They help their owners navigate large, rapid rivers on a regular basis. In the course of these journeys, the stem-bands will knock against rocks. After a while, the canoe will begin to leak as water seeps in through the screw-holes. I restored a canoe for a client a few years ago and now he brought it back to the shop for a little repair work.

The screws holding the bow stem-band to the hull had worked loose and the seal had broken between the hull and the stem-band.

I started by removing the stem-band. Some of the screws had been worn down to the point where a screwdriver was no longer effective. A cats-paw pry-bar and a mallet popped the stem-band off in short order. The stem-band was set aside to be re-installed later.

The location of every screw-hole was marked with a grease-pencil.

Small pegs were whittled from a scrap piece of cedar. The pegs were dunked in water, coated with polyurethane glue and tapped into the screw-holes with a mallet. The glue was allowed to cure overnight.

Each of the cedar pegs was cut flush with a Japanese cross-cut saw.

The entire painted surface of the canvas was sanded with 120-grit paper on a random-orbital sander. Most of the bottom was scuffed and/or gouged by encountered with rocks. The sanding smoothed out the surface and prepped it for a fresh coat of paint.

The stem-band was re-installed with new bronze screws (in this case, ¾”- #4 flat-head, slotted screws). It was sealed with Dolfinite marine bedding compound and allowed to set overnight.

The outwales were masked with tape before a fresh coat of oil-based alkyd enamel paint (thinned 12% with paint thinner) was applied with a disposable foam brush.

The masking tape was removed about an hour after the paint was applied. Any paint that ended up on the outwales was removed with a little paint thinner on a clean rag.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.

August 27, 2024

How To Build Cradles (Display Stands) for Wood-Canvas Canoes

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

email: artisan@canoeshop.ca

Once you’ve got your canoe out of the shed for the season, you’ll need some way of supporting it off the ground when it is not on the water. I can still hear my father saying, in no uncertain terms, “The bottom of this canoe touches two things: air and water”. One of the most convenient support systems is a pair of canoe cradles.

They are quick and simple to build and can be stored easily when not in use. They are also essential tools when repairing or refurbishing your canoe.

For the cradles I build, each one consists of two vertical struts, two base struts, two horizontal brace struts, two sling clamps and a cradle sling. All you need to build a pair of cradles are:

4 – 8’ 2×4’s (spruce) to make the struts;A bunch of 2½” deck screws to hold the whole thing together and;2 strips of material 3½” wide for the slings (I use pieces of carpet or scraps of canvas leftover from a canoe project). I have seen some people use 3/8” rope for the slings.As far as dimensions are concerned, I find a stable design that still holds the canoe off the ground at a comfortable height have vertical and horizontal struts that are 28” long. The base struts are 24” long and are oriented parallel to the centerline of the canoe to create stable “feet” for the cradle. The sling material is about 50” long. The clamps are just scrap pieces used to hold the sling material to the vertical struts. These can be about 6” long – whatever you end up with.

To build a cradle, start by creating the two sides. They each consist of a base strut attached to the end of a vertical strut to form a T-shape.

Next, the 28” bottom brace strut is attached between the two sides and the 28” upper brace strut is positioned somewhere in the middle of the vertical strut.

I take a minute to round-off the inside corners of the vertical struts. Otherwise, the sling material wears out quickly and has to be replaced frequently. I use an angle grinder to round the corners, but the same job can be done with a rasp and a little elbow-grease.

Construction of the cradle is completed by attaching the sling by means of the clamps. The whole process takes the better part of an hour for both cradles. If you want to pretty them up a bit, the struts can be rounded off and sanded smooth.

Any cradles that are going to spend a lot of time outside are finished with an opaque oil-based stain to protect the wood.

All of this (and much more) is described in my book – This Old Canoe: How To Restore Your Wood Canvas Canoe.

If you live in Canada, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the USA, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

If you live in the UK, CLICK HERE to buy the book.

Si vous habitez en France, CLIQUEZ ICI acheter le livre.