Exponent II's Blog, page 288

September 14, 2017

Support for our Sisters at FemWoc & FMH

It’s important to amplify this message of support for our sisters at FemWoc

Written as an editorial from our pals at FMH, it expresses the inherent problems of white male artists using the figure of a nude black woman for their financial gain. Please read.

http://www.feministmormonhousewives.org/2017/09/standing-with-african-american-mormon-women/

September 13, 2017

Persisters in Zion/Daughters of Exponent: a Medley

[image error]

Every year at the Exponent retreat I find myself belting it out at the talent show. Which is hilarious because I am no singer. But I have a strange gift that I trot out annually: I’m sort of a Mormon housewife version of Weird Al. Taking hymns and substituting wacky lyrics for reverent ones gives me deep, deep joy. Past songs have included “Come ye Husbands of the Ward” and “The Modesty Song.” This year Liz inspired me to take the oft sung YW/YM medley, “Sisters in Zion” and “Army of Helaman,” and give it a political twist. For dramatic effect, the Red Hot Mamas sang it through all the way, then divided and blended verses 3 and 4, singing the final chorus together. Of course there were props. There are always props. Be inspired to come up with your own.

As Persisters in Zion we’ll stand up to douche bags,

We’ll try to build bridges instead of huge walls.

And those who insist upon grabbing our kitties

Will find out that bravery does not come from balls.

Persisters in Zion are women of action–

Calling out haters and shouting the truth.

Let’s not hang with Nazis; let’s fight for the Dreamers

And show off our power in the voting booth!

We have been shown, like our mother Eve

To stand up boldly for what we believe.

We have been taught by first lady Michelle

That we should go high while they go to hell!

Oh we are here as daughters of Exponent.

Enlarging the circle of love.

And we will try to make this a safe place

To honor our Mother above.

September 10, 2017

Trump and His Anti-Family Policies: Hurting Mormon Families

Guest post by Chocolate Chip Biscuit

The latest news with Trump’s move to eliminate DACA is yet another step in Trump solidifying his anti-family policy position. Unfortunately, I am well familiar with his anti-family policy changes—because it has hurt my family. DACA hasn’t hut me, but it has hurt people you know. Another kind of his anti-family policies has hurt me. The one where the US won’t allow the spouse of an American any rights.

To be clear, I am an American, born and raised. I prefer Ranch dressing, peanut butter sandwiches, and soft chocolate chip cookies. My husband is Australian. He prefers no salad dressing, Vegemite sandwiches and biscuits as hard as rocks. Our children have preferences that reflect both cultures, and we are happy. We chose to live in Australia for a time as my husband had good employment and we wanted for me to be able to stay home with our children. Ya know. The Mormon thing.

As our children became school-aged, we decided that we would visit the US, re-connect with the American side of our family and delight in partaking of Idaho potatoes flooded with American cheese. Still employed but on leave of absence, my husband and I also planned to investigate schools and neighbourhoods with a mind that if all fit well for us, we would go about the process of moving to the US.

Even though he is my spouse and we have been married more than a handful of years, he still has to go about the migration process the same as any non-American. We had been through this before—first for me, when I migrated to Australia, and secondly for him, on the advice of an attorney as we were in the process of adopting, in case it made us look better on adoption papers. At that time, my husband was granted a 2-year residency visa (“green card”) which took the standard 8-12 month processing time and at a real financial cost. However, we did not need or use that visa. We’re Mormon– we looked good on paper anyway. So his American visa expired as an unused by-product.

We planned for a temporary visit to Utah this summer, meaning a tourist (ESTA) visa- the kind of visa that takes very little processing time, costs very little and is often an instantaneous turnaround when you travel on vacation to different countries. We were well aware that this kind of visa meant that my Australian husband would not be able to legally stay longer than three months. Thus, all of us—not just my husband– had tickets to return to Australia. The plan was to discover if Utah was a good fit for our family. If it was, then we would invest the time and money for a more permanent visa.

That was the plan. But the US would not let him enter. He was issued an ESTA visa when we purchased our tickets. But it was revoked without notice a few days before we were to leave. We discovered it had been revoked at the airport as we were checking in our bags. Nothing had changed on our side; he had still never been convicted of any crimes, he has never overstayed or broken the conditions of a tourist visa previously, we had return flights, and ongoing employment in Australia. We’re Mormons, for heaven’s sake!

[image error]And yet, he was considered untrustworthy. Why? Me. His wife. His eternal companion, signed and sealed at the St. George Temple in Utah. And our daughters. As Americans, my daughters and I make him look bad. Because he had a legal, permanent visa beforehand, he can no longer enter the US on vacation. I make it look like he is going to break laws to stay with me in the US rather than going through the proper process. My marriage and our family look like security threats to Trump’s immigration policies. My American nationality hurts my husband’s non-American visa application.

We thought it was a mistake. Perhaps something simple that we or the travel agent filled out wrong. A miscommunication. An unticked box. A spelling error. So, I went ahead with my children, thinking that my husband would be on a plane the day after. But I was wrong. Very wrong. We fall into a new category of “presumptive visa violators.” This is a new Trump thing wherein he is presumed guilty and must prove his innocence. You see, he can’t be offered American privileges such as “innocent before being proven guilty” unless he is in the United States. Outside of the US, US policy doesn’t have to represent American values: so it doesn’t, especially under Mr. Trump.

While I was in the air managing my children on a long flight alone, my husband spent the majority of the day trying to track down what went wrong. He went to the US Consulate in Sydney, who told him to apply, then re-apply on the website, because they could not help him. But according to the website, he had done everything correctly. We discovered that while the State Department (SD) processes most visa applications, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) takes the lead on implementing laws. However, the DHS is not a foreign affairs agency of the US Government, so communication between the SD, DHS and the US Consulate is bound by the red tape of each others’ bylaws, which are sometimes in conflict—or in the case of DHS- is not a foreign affairs agency.

After exhaustive days and nights of applications and knocking on every immigration door available, he did not make the next flight, or the one after, or the one after that.

He waded through paperwork, confused as to why he could not obtain a visa, I contacted US-based immigration lawyers who simply said that he should apply for a green card. “But, he’s not going to work,” I would say, incredulously. “We are going to family reunions. We’re on vacation!” I was told that didn’t matter—that because of our marriage, he was considered presumptively guilty of overstaying a temporary visitor’s visa unless he could prove he did not plan on breaking immigration law in the future. It sounded ridiculous to us, but this was Trump policy: guilty until proven innocent. The confusion of the situation and the associated contrasting advice between the consulate and immigration was overwhelming. I hasten to add that we are university-educated, native English-speakers. I cannot fathom how difficult this would be for those who lack education, or worse, have a lesser command of American English.

Almost immediately upon my arrival in Utah, I was clandestinely contacted by other Americans in situations similar to my own. Families of mixed nationality, some part-Australian, some not. All part-American. Law-abiding, legally employed Americans who simply fell in love with someone of a different nationality. I did not meet their non-American spouses, but they all had similar stories: many were returned Mormon missionaries with clean records, all law-abiding individuals without a sniff of criminality in their background or future, yet they were refused entry to the US. I met the children who had not seen their non-American parents for months—the months since Trump had been in office. Wives who refused to post family updates on Facebook because they had been told that DHS agents could claim they were coded messages for illegal immigration. Husbands who refused to email or text wives because they had been told ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) agents would intercept them and manipulate the meaning into something that would harm visa applications. Americans living in the US, afraid to say anything because “Uncle Sam’s Big Brother” was watching them and would hurt their family.

This is not the America I know. This is not the America I love. To be fair, I lost count of the number of the American friends and strangers who embraced me and my children when our family was attacked by Mr. Trump. One friend loaned us a car. Others brought food, provided childcare, and even an inspired stranger paid for our tickets to the Heritage Village at the This is the Place Heritage Park. It was there at the Heritage Village Museum that my children had so much fun that we all forgot for a moment that our family was targeted by these new and confusing American policies. We supped on Brigham Young’s doughnuts, mined for sparkling stones, and felt at one with the Pioneers who were also forced to leave the US and create a home elsewhere because of political bias.

Gratefully, God’s hand reached out and protected us through friends and strangers. They cried with us, and as they did they said, “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. This policy is not American. I’m so sorry.”

[image error]

My daughters and I secured early returns to Australia. We decided that though Utah is a kind of home, living in the US was off the table: we did not want to risk being months or possibly even permanently separated while we waited and hoped for a visa that may or not be granted. But this is what it is like for ex-pat and mixed nationality families. There are narrow formulas and guidelines that define what a family is supposed to look like to the SD, DHS, ICE and immigration. When your family looks different- because of ethnicity, employment (or lack of employment), language, and even adoption, then your family has a target on its back.

And you know what? We still had it easy. Shock, emotional roller-coaster and sense of patriotic betrayal aside, we still had it easy compared to others. Our skin colour, Anglo-ethnicity, cultural background or religious affiliation did not class us in ways to cause outward bias and rejection. My husband had a job, our non-American home is not a war zone and our fellow church members of various political viewpoints welcomed us to return to and recover.

While we were in the US, I watched ICE raids on the news with fresh eyes—I saw the families separated, hearts broken, and injustices heaped upon children, marriages and families. Conservative friends offered letters of recommendation, thinking something so daft as a letter from a Trump voter could suddenly heal or change Trump’s anti-family policies. Some looked at me with questioning eyes, seeming to think we had some illegal skeletons in our closet. But we don’t. My husband doesn’t. His only fault is being married to an American.

September 6, 2017

Exponent II Writing Contest 2018

For this year’s writing contest, Exponent II wants to honor the women who have provided us with examples, advice, and experience. We are asking for submissions about spiritual foremothers.[image error]

Who is your spiritual foremother and how did she impact your life? You may choose a relative, a fictional character from literature, historical figure, a woman from scripture, a teacher, a friend, or a mentor. What guidance did she give you? How did she impact the decisions you made in your life? How do you see her reflected in who you have become?

We are[image error] not looking for sentimental tributes, but rather an awareness of how the women who have gone before us have influenced and shaped us. We hope to get a sense of the complexity of our foremothers and how connections to them last through time. Be specific in how your foremother impacted your character or decisions. The winner of the contest will give us a vivid picture of her foremother and develop readers’ interest in the relationship.

The winner of the contest will receive a one-week stay at

[image error]Anam Cara, the writers’ retreat in Ireland owned and operated by former Exponent II editor Sue Booth Forbes. More information about Anam Cara can be found at www.anamcararetreat.com.

Submissions must be between 700 – 2000 words and are due November 1, 2017. Exponent II only publishes work by women. Send submissions to exponentiieditor@gmail.com.

September 4, 2017

September Young Women Lesson: Why do we fast?

FOREWORD: There are some things to be aware of when teaching a lesson on fasting (especially with young women). Many LDS youth are growing up in societies that idolize female thinness and put an immense amount of pressure on women to obsess over and meticulously monitor and perfect their appearance, and it’s not a secret that Mormon culture (at least in some parts of the world) often adds to rather than works against this. With this context, and because the word “fasting” can be used to describe both a religious ritual and a fad diet (that’s especially big right now), I think there’s a very real danger in these kinds of discussions of equating self-inflicted hunger with holiness—sending the message that food as a general rule is something that dulls or diminishes a connection with God, and that our worthiness (especially as women) hinges on our ability to exercise extreme control over (rather than be mindful of and kind to) our bodies. Studies show, too, that while religious fasting can improve body image for people with low levels of “eating distress,” religious fasting can also “exacerbate or disguise eating disorder behaviors” and work as “a trigger for those at risk for or in the process of developing an eating disorder.” Please allow all of this to inform what you do and do not say in this lesson.

Beginning: What is the purpose of fasting ?

Start by posing the first question, the last two, or all three:

“What is the purpose of fasting? What are some good motivations to fast? What shouldn’t be our motivation to fast?”

Have them read the following scriptures to answer the question(s):

Alma 17:2-3 (fasting to increase ability to prophecy and receive revelation)

Esther 4:10-17 (fasting as a way to come together as a community in solidarity towards a higher goal; to call down increased divine help)

Isaiah 58:3-12 (fast with the purpose of more deliberately “approaching… God,” that we might gain greater clarity and strength to rid ourselves of ungodliness [“loose the bands of wickedness”] and to be more aware of and offer greater help those in need [“undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free… to deal thy bread to the hungry… and bring the poor that are cast out to thy house.”].

Alma 6:6 (fasting along with “mighty prayer” in behalf of others)

Helamen 3:35 (fasting to reacquaint ourselves with our values, recenter our lives around Christ, and make a more dedicated and concerted effort to make space for stillness and for the Spirit to dwell within us)

Fasting in other faith traditions

Ask the young women, “Are Mormons the only religion that encourages its members to fast?” (They’ll almost certainly say no). ,

Ask them for examples of religions that include fasting in their spiritual practices and what they know about the rules and traditions around fasting in these traditions (they will likely know some things about Muslims with Ramadan, Catholics with Lent, etc.). If it were me, I’d add a bit to what they already know and also throw in a few fast facts (pun intended) about how fasting is approached in traditions like the Baha’i faith, Hinduism, Judaism, and/or Protestant religions like Lutheranism. (If you are going to use the links I’ve provided to do this, maybe give a “this is from Wikipedia” disclaimer.) This shouldn’t take up a huge chunk of time.

Please note: only include this section if you can model talking about the beliefs and practices of other faiths with sincere respect and if you are willing to respond constructively to any disparaging comments that might be made about other faiths (I’ve never had a young woman say something unkind or inappropriate in these kinds of discussions, but I’m sure it can happen). The point here is not to mock or condemn different ways of fasting or to somehow prove that Mormonism’s way is “best.” Rather, the goal here is simply to remind the youth that Mormonism doesn’t exist in a vacuum; that people from all over the world (and not just other Christians) fast for many of the same reasons we do. The fact that Mormonism shares many values and practices with faith traditions from around the world (and not just other Christians) is an eye-opening, heart-softening, and connective thing to remind the youth of every so often.

When there needs to be an alternative to going without food

Ask the class, “Are there times when people should fast in ways that don’t include giving up food? What are some situations when fasting by giving up food and/or water might not be best?”

Possible answers:

When pregnant (not good for the baby) or breastfeeding (can lower milk supply)

When experiencing a health condition where fasting wouldn’t be safe (e.g., many doctors recommend that diabetics not fast)

When we are too young or not fully able to make the decision about whether or not we want to fast by giving up food

When someone has or is recovering from an eating disorder or experiences lots of anxiety around eating and/or body image (if this one isn’t mentioned, bring it up yourself. When I taught this lesson today, I went over most of the things I included in this lesson’s foreword.)

Share this quote by President Joseph F. Smith:

“Many are subject to weakness, others are delicate in health, and others have nursing babies; of such it should not be required to fast. Neither should parents compel their little children to fast… Better to teach them the principle, and let them observe It when they are old enough to choose intelligently” (Gospel Doctrine, p. 244).

(I recommend emphasizing the part that says we ought to choose for ourselves whether/how to fast and remind them that it’s none of our business how/whether others do.)

Quickly review the purposes of religious fasting, and then ask them what some alternatives might be for those who shouldn’t fast by giving up food.

Possible answers:

-Temporarily remove distractions like gaming and social media apps from your device and instead using your phone to listen to more inspirational music, spend more time reading scriptures or other uplifting poems or prose, etc.

-Spend the time making a concerted effort to be aware of and ask for strength to overcome bad habits (e.g., making unkind mental judgments about people, not practicing good listening skills with family members, etc.)

Important Elements of a Proper Fast

Prayer

While not eating doesn’t necessarily need to be part of a proper fast, there are important elements that need to be present in our fast in order to take advantage of the purpose of fasting.

Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin taught, “Without prayer, fasting is not complete fasting… If we want our fasting to be more than just going without eating, we must lift our hearts, our minds, and our voices in communion with our Heavenly Father. Fasting, coupled with mighty prayer, is powerful. It can fill our minds with the revelations of the Spirit. It can strengthen us against times of temptation.”

Ask, “Why do you think prayer is such an important part of fasting?”

Providing temporal help for those in need

Elder L. Tom Perry taught that of all the purposes of fasting, the first is that “it provides assistance to the needy through the contribution of fast offerings, consisting of the value of meals from which we abstain.”

What do fast offerings in our church go towards?

Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin taught, “Fast offerings are used for one purpose only: to bless the lives of those in need. Every dollar given to the bishop as a fast offering goes to assist the poor” (April 2001 General Conference).

Elder Eyring taught, “Part of your fast offering and mine this month will be used to help someone, somewhere, whose relief the Lord will feel as if it were His own” (April 2015 General Conference).

Remind them that while they probably don’t pay fast offerings right now as teens, Isaiah taught that fasting with the intent to serve others is an important part of fasting: to “undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free… to deal thy bread to the hungry… and bring the poor that are cast out to thy house” (quoting Isaiah 58 again).

When we fast for something that doesn’t “come true”

When I taught this lesson yesterday, one of my young women made a comment that led me to add this section to my lesson. With what seemed to be some disappointment and confusion, she remarked that she knows that God “is supposed to hear us better when we fast” (rather than just pray), but that she has fasted for things that haven’t “come true.” Responding to this kind of observation obviously isn’t comfortable, but I think it’s an important topic to start to address more honestly and openly with the youth.

If you need to introduce the topic, I would start with a question with an obvious answer, like “When we fast for something specific, like a loved one’s return to health, is there a guarantee attached that everything we ask for will happen?” (They’ll almost certainly say no.)

At this point, I’m hesitant to give a one-size-fits-all recommendation for how to proceed, so I’ll just summarize what my response was today to the young woman in my class; take it for what it’s worth.

First, I tried to validate her concerns. I told her that I’ve also said lots of prayers and participated in many fasts where I asked God for something that didn’t “come true.” That it can be tough to realize as we get older that prayer isn’t as clear-cut as we may have believed it to be as kids (and that realizing this isn’t good or bad—just a sign that we’re growing up.)

I also assured her that unanswered prayers don’t mean that we didn’t pray or fast “right,” that what we wanted was evil, that we weren’t being faithful or “good” enough at the time to receive the answer we wanted, or that God doesn’t hear us. I told her that there’s a lot I don’t know or understand about prayer and God and how God hears and works with us, but that I don’t think a loving God would be more willing to give guidance and support to those who fast than he is to those who have just prayed for something, just like he isn’t somehow more willing to hear prayers that use “thee” and “thine” than he is to hear prayers that use everyday language, etc. I told her that I think that fasting is more for us—an opportunity for us to make a more dedicated and concerted effort to make space for prayer, sincere reflection, and Grace to enter our hearts; to feel gratitude for all of the good in our lives and to turn our attention to the needs of others and how we can be more aware of, kind to, and helpful towards other people.

I haven’t had enough time or mental energy to reflect much on how I could have improved that response (although I think responding with more questions rather than just straight talking at them would have been good), but there it is.

Conclusion: End by briefly bearing testimony of a principle you taught that is especially meaningful to you, giving them a few minutes to think about and make plan to make fasting more personally meaningful for them in the future, and/or expressing your love for and confidence in them.

September 3, 2017

Youth, Bishop’s Interviews, and Self-Exploration: Shepherding Our Youth to a Healthy Sexuality

by Anonymous

by Anonymous

My oldest child is less than one year away from going into Young Men’s. I’m concerned about the interviews with the bishop that will be forthcoming.

My worry is that the bishop will ask him about masturbation. I don’t know if my son has done it or if he will be doing it in his teen years, but I lean towards viewing the practice as a natural part of human development. Not that I want him to be doing it five times a day. And I definitely don’t want him looking at porn. But my intuition is that it’s normal and not unhealthy for a teen to have some sense of how his/her body works sexually.

I recently learned from LDS therapist Dr. Jennifer Finlayson-Fife, in fact, that girls who self-explored and understood how arousal happened – and who viewed their sexuality as their own and not their future husband’s – were more likely to have healthier and happier sex lives once they were married. As she says, what we want to do as parents is to shepherd our kids into having healthy, committed, loving partnerships someday. Things that are likely to not lead to that – like porn use – should be discouraged. Also discouraged should be messages that associate sexuality with dirtiness, shame, badness, etc., since people who have internalized those messages often have a difficult time embracing their sexuality in marriage.

I’m not sure if self-exploration among adolescent boys is correlated with a future healthy partnered sex life, but I think some curiosity and self-exploration is fine, and I hate the idea of my child being eaten up by feelings of guilt or shame because of it. I also am deeply uncomfortable with the idea that my child might feel he has to have a humiliating talk about something so personal and so private with a man who is virtually a stranger. The whole setup raises red flags for me.

So I’m in the midst of mapping out strategies for how to deal with this situation when the time comes. I’m thinking this will be my plan of attack:

Talk to the bishop privately and ask him about his interview practices. What wording does he use when he asks about the law of chastity? Does he ask youth about masturbation? If so, I will ask him to not ask my son about that. If the bishop insists on asking that question, I’ll suggest that my son tell him, “My mom has told me that I do not need to discuss that with you.”

Talk to my son and tell him that I believe the law of chastity to be referring to two people engaging in sexual acts – not self-exploration.

Talk to my son about how he feels doing these interviews. Does he want to be interviewed? Would he like a parent to be there? I’m happy to accompany him – and happy to talk to the bishop beforehand about what exactly he’ll be asking so he’ll go in knowing what to expect.

With my daughter, I plan to be in the room during interviews. It’s uncomfortable to think of stranger men talking to my son about chastity stuff, but even more red flags come up for me when I think of my teenage daughter being exposed to questions about sex from a forty-year-old man behind a closed door.

I’m hoping these precautions will help protect my kids from unnecessary guilt and intrusion into their personal lives. To be clear, I’m pretty confident that our bishop is an upstanding and non-creepy guy. But the very setup, which I know in times past has involved direct questions about masturbation, seems very problematic. I’d like my children to learn in their youth that there are boundaries they should feel free to draw with their church leaders — and that there are issues that they should determine the morality of for themselves.

What have been your experiences with this issue? Are you concerned about bishops talking to youth about this? Why or why not?

August 30, 2017

Don’t Tell Me I Don’t Understand the Priesthood

Sad Clown Girl by Cris Motta

Last week’s lesson in Relief Society was on the Priesthood — always a real favorite for an all-women organization. I was already struggling because Phred had gotten a head start on what is turning into a multi-day “I won’t nap but I WILL fuss and scream” binge. So by the third hour of church I was feeling pretty done. But I wanted to give it a fair shake, and interact with adults.

The teacher opened the lesson by sharing that she had had many friends in the “Ordain Women” movement and that she had struggled with many questions and difficulties relating to the priesthood — I appreciated this vulnerability. She said that her answer was that in time when she went to the temple those questions would be resolved, and they were. I’m afraid that if I say “I’m happy for her” it’ll sound petulant and insincere. But I’ve also had a total of 15 minutes this entire day not engaged in child care of a fairly draining nature so crossness is where I am, with no reflection on the poor teacher. She then invited the class to share experiences or feelings relating to the priesthood, and many did so. Again, I appreciate this approach to teaching that allows for many people to offer their own opinions.

The thing is, there seems to be only one approved opinion. This is no surprise to me of course, I’ve been LDS my whole life and I’m nothing if not aware of the party line. I thought about sharing my point of view. I even raised my hand. But after hearing comment after comment that slowly wore me down when I’m already exhausted and frail I just didn’t have it in me to be the only one saying what I have to say. I looked around the room and thought, “I don’t think anyone in this room wants to hear this, and I don’t feel strong enough to say it.” So I took the excuse of my fussy cross baby and quietly walked out. Perhaps I missed a lesson that really would have met my needs. But sitting on the lawn with my baby felt like the safer choice. However, I keep stewing and unless I write I won’t be able to siphon off the feelings of anger.

Here is what I perceived to be the gist of the comments and the perspective of my sisters: The priesthood is wonderful (many examples of blessings etc.). Women (“educated” women singled out) who want the priesthood or have a problem with male-only ordination don’t understand. The truth is that men and women both hold the priesthood. Or maybe it’s that both men and women have to ask another man if they want a blessing, men don’t bless themselves, so really it’s the same for men and women. Having a man who holds the priesthood in the home, even if he is a 12-year-old boy, is wonderful and important.

Here’s my deal. I’m educated, and male-only ordination causes me pain, and I’m not ignorant or unable to understand or unfamiliar with the Temple. The Temple brings peace on this issue to a lot of women. It makes things worse for me. My feelings and experience with this are valid and are not a product of my inability to understand truth.

I have been through hell bringing my children to earth. I have paid a terribly high price in physical hardship and suffering. My mental and emotional health are in tatters and it’s getting worse, not better. I walked this horrible road largely alone because nobody could carry any of this burden for me. And I am not allowed to give my child a name and a blessing. I’m not even allowed to stand in the circle, to hold my baby while my husband blesses him in front of our congregation. When Pip was blessed, the Bishop, though not invited to join the circle as a particular friend, just did so as a matter of course. He could casually get up and elbow in, but I sat back on our pew. The only way I was able to cope with this awful exclusion with Pip was to tell myself that I simply do not care about baby blessings. Indifference became the defense mechanism I needed in order to face the fact that the church sees priesthood and motherhood as equivalent. I tearfully told Chris on the way home from church that I’d be very glad to swap — he can vomit and vomit and vomit and then be up all night while a child gnaws on his nipples. I’ll do the snuggling and naming and blessing part if they’re so interchangeable and equivalent.

I will do the lion’s share of rearing my sons in the Gospel. I say the most prayers with them. I am the one reading scripture stories and explaining about Jesus. I’m the one singing primary songs and teaching them to our sons. This is not an aspersion on my husband, nor is it an avowal of my “role” — I am home. This ends up being something I’m doing more. But I will not be allowed to baptize my sons. I won’t be allowed to give the Gift of the Holy Ghost. But it goes further — I’m not allowed to be a witness. I’m not allowed to stand in the circle. I’m not even allowed to conduct the meeting.

And so it will go on and on and on. At no point in my son’s lives will I have any relevant role in any ordinance. If I had daughters I could possibly help them in the Temple. But as a mother of sons I will not be allowed to sit by them, or talk to them, or instruct them in any way. I will not sit at my husband’s side, co-witness of the wedding.

To me it seems of a piece with pregnancy — I’m good enough to do all the endless heartbreaking soul-crushing work of preparing the way, but at every crowning moment and milestone I am to sit invisible and silent on the sidelines.

It feels really fantastic.

So don’t tell me that I don’t understand, or that men and women share the same access to the privileges of the priesthood, or if I just thought about ordinances I’d feel a lot better. I understand all too well. My access is not equal. And thinking about ordinances makes me feel really, really, really sad.

August 29, 2017

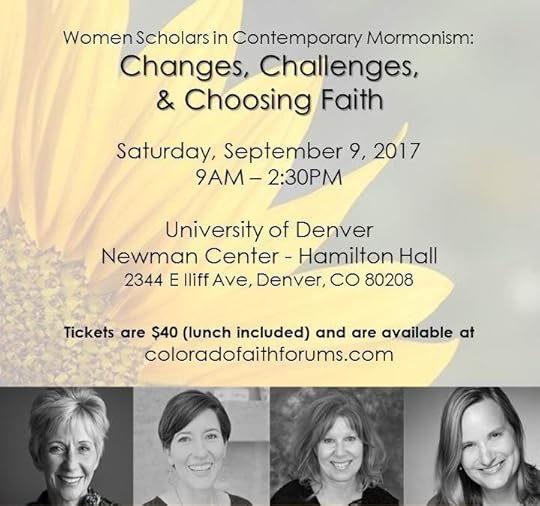

Colorado Faith Forum: Women Scholars in Contemporary Mormonism

I am thrilled to announce the Colorado Faith Forum’s first annual symposium on September 9, 2017. This year’s event will be featuring some of our preeminent Mormon scholars, discussing Changes, Challenges, and Choosing Faith in contemporary Mormonism. I have included the biographies for the panel below. This will be an amazing event–I have had the opportunity of hearing all of these women speak and have found them all to be engaging and inspiring. If you live in Colorado or want to take a quick trip to our beautiful Centennial State, tickets are still available and can be purchased here.

The mission of Colorado Faith Forums is to promote thoughtful and faithful discussion of Mormon topics through various outlets, including an annual symposium and periodic forums. They seek learning, dialogue, and analysis of any issues concerning Mormon religious belief and culture. They welcome a broad range of ideas and attitudes on these topics while maintaining a goal of promoting faith and constructive dialogue and avoiding negativity or animosity. Colorado Faith Forums believes that the organic development of such forums for study and discussion, encompassing a variety of perspectives and opinions, can lead to opportunities for increased understanding, knowledge, and discipleship.

On a personal note, it has been so encouraging to watch Colorado Faith Forums create a space for thoughtful people and conversation. I have had the opportunity to attend two of their events, one with Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and the other with Claudia and Richard Bushman. I found both evenings to be intellectually and spiritually broadening.

I hope many of you will be able to experience this as well.

Participant Bios:

Fiona Givens was born in Nairobi, educated in British convent schools, and converted to the LDS church in Frankfurt. She graduated summa cum laude/phi beta kappa from the University of Richmond with degrees in French and German, then earned an M.A. in European History while co-raising the last of her six children. Fiona was director of the French Language program at Patrick Henry High School, in Ashland, Virginia. Besides education, she has worked in translation services, as a lobbyist, and as communications director of a non-profit. She has published in Exponent II, Sunstone, LDS Living, Journal of Mormon History and Dialogue. Fiona is also a frequent speaker on podcasts and at conferences from Time out for Women to Sunstone. A longtime collaborator in the books of her husband, Terryl Givens, she is the co-author of The God Who Weeps: How Mormonism Makes Sense of Life and Crucible of Doubt: Reflections on the Quest for Faith.

Neylan McBaine is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Mormon Women Project, a digital library of hundreds of fascinating interviews with LDS women from around the world. Her newest book Women at Church, explores possibilities for increased female participation in LDS administration. She is the author of a collection of personal essays, How to be a Twenty-First Century Pioneer Woman, and the editor of Sisters Abroad: Interviews from the Mormon Women Project. She has been published in Newsweek, Washington Post and Dialogue. She is the founder and CEO of The Seneca Council, is a graduate of Yale in English Literature, and lives with her husband and three daughters in Salt Lake City.

Margaret Blair Young has written six novels and two short story collections and teaches creative writing at BYU. With her co-author, Darius Gray, she has been researching and writing about race issues in the LDS Church and about black Mormon pioneers since 1998. She also writes academically about African American history in the western United States. She has scripted and co-produced three documentaries and is now working on her first feature film, titled “Companions.” The film is set in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Margaret is involved in a number of projects, primarily focused on education and peace building. Her journey as a writer and filmmaker has been much easier than her journey as a mother, though she treasures the many ways parenthood has stretched her, and is in some awe of her children. She and Bruce Young have two sons and two daughters, and four grandchildren.

Jana Riess is the author of many books, including Flunking Sainthood: Breaking the Sabbath, Forgetting to Pray, and Still Loving My Neighbor and The Twible: All the Chapters of the Bible in 140 Characters or Less . . . Now with 68% More Humor! She has recently conducted a national survey of four generations of current and former Latter-day Saints, which will be discussed in depth in the forthcoming book The Next Mormons: The Rising Generation of Latter-day Saints in America. She has a PhD in American religious history from Columbia University and lives in Cincinnati, OH, where she serves as a counselor in the Relief Society presidency.

August 28, 2017

Death and Ritual in Mormonism

I recently watched a fascinating Ted Talk by Kelli Swayze entitled, “Life that Doesn’t End with Death.” She talks about her husband’s home culture in Tana Toraja, Indonesia, and how, in the Torajan culture, physical cessation of life is not the same as death. Rather than quickly burying or cremating a body after death, the dead bodies of their loved ones are preserved, placed in their ancestral home, and symbolically fed and cared for. They’re treated as continuing members of the family, even being included in pictures and family events, up until the time when the family can marshal the resources to have a burial ceremony with the entire community (which sometimes doesn’t happen until years after the person has physically died). To quote Kelli Swazey, “Torajans socially recognize and culturally express what many of us feel to be true despite the widespread acceptance of the biomedical definition of death, and that is that our relationships with other humans, their impact on our social reality, doesn’t cease with the termination of the physical processes of the body, that there’s a period of transition as the relationship between the living and the dead is transformed but not ended.”

[image error]

I’ve been thinking about death a lot recently. My dad died a couple of months ago, and as I’ve been processing the experience, I’ve been particularly grateful for the rituals that Mormons have surrounding death. Family members gathered from across the country. We had both a viewing at the funeral home and a funeral at the church. Several members of my family and my parents’ ward helped dress my dad in his temple clothes prior to burial. We had a family prayer immediately preceding the funeral before closing his coffin for the final time. And, in one of my favorite rituals, the Relief Society inundated us with food, both before and after the funeral service. People were bringing by meals and snacks and casseroles to put in the freezer to eat a later date when cooking would just feel too overwhelming. In a particularly touching gesture, one member of my parents’ ward headed up a collection of toys, coloring books, games, and snacks for my dad’s grandchildren (including my children) to enjoy during the often long (and, to kids, super boring) hours of the whole affair. We buried my dad in a cemetery near other deceased relatives, and had people say a few words of comfort and recall some memories before dedicating the grave and lowering his coffin into it.

It was so comforting to have rituals that felt familiar during this time of grief and despair. I knew what to expect, and I felt surrounded by love and comfort (and food) (seriously, there was so much food). It felt like a social affair and in some ways, it validated my grief at the loss of my dad’s life to see so many people show up to communally mourn. In some ways, having so many people be present with us made my tremendous grief feel appropriate: yes, this man was important and his life was worth celebrating and his loss was worth grieving.

Since then, though, I’ve felt a yearning for rituals surrounding mourning. The entire death/burial process felt like a blur – the whole death-to-burial period took less than ten days. And after that, we were left to privately mourn. The flowers sent by well-wishers wilted. The family members and friends returned home. Life just kept moving on, but I felt like the warm blanket that ritual had provided before was removed, and I was left to grieve in ways that felt uncertain and vulnerable. How am I supposed to do this?? Am I crying too much? Too little? How much should I talk about him? Does it make others uncomfortable when I mention it? How do I go about integrating this tremendous loss into my life?

I think this is why Swazey’s Ted Talk profoundly moved me. I don’t know that I necessarily want to go the route of the Torajans and have my dad’s preserved body hanging out in my living room, but I do wish that we had better rituals surrounding the transition period (from relating to the deceased as a person who’s living to relating to the deceased as a person who’s an ancestor) that the Torajans honor. Even though my dad was on hospice at the end of his life, and death was expected, it felt so sudden to go from him being an active and involved person in my life to being dead. I admit craving some sort of action or ritual that I could perform to help me sort out my relationship with him once he had passed away. My dad was a lifelong member of the church and completed all of his temple ordinances while he was alive, but I admit longing for a temple ordinance that I could perform on his behalf to somehow cement our relationship to one another, even if that was already ceremonially completed when my parents were sealed and I was born in the covenant.

So I’m left to create my own rituals of grief, as many in Western cultures are left to do. For his funeral, we put together a slideshow of pictures from throughout his life, and I look at them when I want to feel connected. On his birthday, I’ll probably make my dad’s favorite foods and watch his favorite movie. I’m sure I’ll mark the anniversary of his death in some way. But after watching Swayze’s Ted Talk, I’m giving myself a little bit more latitude in grieving this particular transition period from relating to my dad as a living being towards relating to him as an ancestor.

What do you think about our rituals in Mormonism surrounding death and grieving? Do you have any particular rituals surrounding grief or loss that have been helpful to you?

August 26, 2017

On White Man’s Burden

In the aftermath of recent happenings in Charlottesville, I’ve been sad and feeling powerless. I’m wrestling with my whiteness and what it means about my responsibility as a citizen of planet earth. In this area, how do we mourn with those that mourn and comfort those in need of comfort? How do we deal with the invisible privilege we inherit? I read Paul Reeve’s book Religion of a Different Color a few months ago and issues of race and Mormonism have stuck with me. My thoughts wander, exploring issues that got us to this point in the first place, and especially how it applies in the LDS tradition.

Although I believe white supremacy is not the dominant worldview of white westerners today, racist attitudes still persist into our modern culture, particularly in how western (white) people continue to relate to people of color. One thing I’ve been particularly been thinking about is the historic benevolent imperialism of western (white) peoples. In history class, I learned that this was called “white man’s burden”; a duty to bring education and ‘civilization’ to the (non-white) colonies. At the time, I didn’t question the assumption that it was okay to ‘improve’ the condition of others even by erasing a huge part of their way of life. The implication was that white people were in a sense ‘saviors’ for colored people. This also made out other races to be childish, needing our guidance, teaching, and leadership (being somehow incapable of self-government). And although I was disgusted when I recognized that white people had eventually used this philanthropic racism to dominate people of color and extort their resources, I was able to separate myself from that. I, personally, had never done that. I didn’t see clearly how the appeal to a morality of helping others had been used to justify stealing their land, their trees, their oil, etc. Imperialism had (and continues to have) some detestable consequences, up to and including forced slavery and cultural and actual genocide. But Mormon colonialism echoed the problems of American and British colonialism.

Sad as it is, this national crisis has also led me to thoughts of how the church has its own manifestation of ‘white man’s burden’. My assumption is that this is a reflection of culture rather than the revealed pattern of the gods. The Mormon mandate is to bring gospel and its culture to all the world, which in its restored form is a modified form of western (white) culture, rather than a true unique culture. The priesthood ‘white man’s burden’ was to teach, convert, baptize, and ultimately preside in every land. The authoritative hierarchical system expects submission and loyalty. Until the last few decades, priesthood was literally a white man’s burden, restricted by race. Now, although ostensibly equal in the priesthood, people of color are still underrepresented in our leadership, particularly at the general level. The higher the level of authority, the fewer people of color are found. Many times local congregations are presided over by white Americans who happen to be living in the area, rather than by local members. White western Mormon culture is the church’s preferred version of Mormonism, the opinions of white Mormon priesthood holders who have held certain callings carry more influence in decisions about how the church operates locally than the people who have spent their entire life there. In the same way that ‘white man’s burden’ led to abuses politically in times past, the church has at times gone beyond the scope of service and subjugated people of color, even without intending to. My musings have only led to more and more questions (and yes, I specifically took off my feminist hat; ignoring for now how women fit in this messy picture).

Does our mandate to take the gospel to all the world make it okay to inject ourselves and assimilate native cultures in our proselytizing efforts? To what extent are we guilty of smothering other beautiful traditions in an attempt to create a semblance of uniformity across the world? To what extent does our understanding of the history of Native peoples as presented by the Book of Mormon influence the way we see them and interact with them? (Do we expect people of color to become ‘white and delightsome’?) How strongly do the emphases of current church leadership messages echo issues that are inherently white or American political issues? What blessings are we as a church missing out on by taking over and speaking over people of color to remake them in our image? And what institutional repentance is necessary for our past racial sins?