Robert Knox's Blog, page 40

June 5, 2016

The Garden of the Sacred: Climbing with Alexander

We climbed the Sacred Way to the Oracle at Delphi. In Ancient Greece, Athenian generals asked the Delphic oracle how to defeat the invading Persians. "A wall of wood," they were told. They built a navy and defeated the invaders, keeping Greece free of control by the Persian Empire.

We climbed the Sacred Way to the Oracle at Delphi. In Ancient Greece, Athenian generals asked the Delphic oracle how to defeat the invading Persians. "A wall of wood," they were told. They built a navy and defeated the invaders, keeping Greece free of control by the Persian Empire.  King Oedipus sent messengers to ask the oracle for the cause of the plague devastating his kingdom and was told that the cause of the corruption was the king. From there, Oedipus's tragedy unfolds. Socrates asked the Oracle how to find wisdom, and was told "Know thyself." The Western philosophical tradition ensued.

King Oedipus sent messengers to ask the oracle for the cause of the plague devastating his kingdom and was told that the cause of the corruption was the king. From there, Oedipus's tragedy unfolds. Socrates asked the Oracle how to find wisdom, and was told "Know thyself." The Western philosophical tradition ensued.

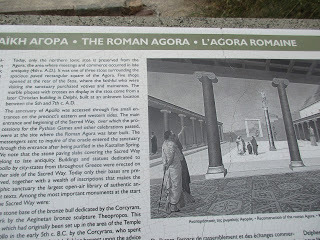

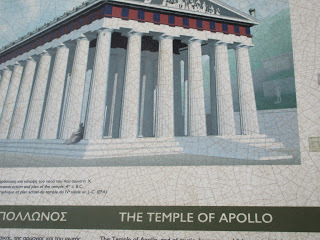

Alexander asked the Oracle whether he would achieve victory in a coming battle. When the priestess charged with interpreting the ravings (or babblings? drugged incoherence?) failed to produce a clear reply, he dragged her by her hair until she shouted, "You're relentless!" OK, Alexander (on the way to being 'Great') concluded, I've got my answer. We explored the remains of Delphi last week, viewing the site of the Temple of Apollo (top photo), the still viable theater in which the tragedies of Sophocles were performed, and then climbing up to the "stadium" where the athletic games were held. No Oracle or priestess takes questions at Delphi there any more. The rise of Christianity eventually put an end to the practice some time in the 5th century AD. Just as well; I wasn't sure what to ask. The Oracle at Delphi was in many ways the center of the ancient Greek world. Compared to the 'body' of monuments, sanctuaries, memorials, and 'gifts' erected at Delphi in its long-ago heyday, the remains are skeletal. Petitioners and visitors climbed to the site to query the Oracle, or spectate at the celebratory "Pythian Games," along a sometimes steep route called "The Sacred Way." Messengers sent by the powerful to make their inquiries -- almost any important decision of state was referred there at one time -- but also business opportunities, law suits, marriage decisions, and who to back in the 800-meter at next year's Olympics -- climbed the Sacred Way, along with the great names of the era we remember. Alexander. Socrates. Buildings and statues were erected along the way to honor, or placate, the God Apollo. In the cabinet of the gods, Delphi was in his department. Apollo had a large brief; he was the god of the sun, but also the god of music; and later was chosen to symbolize a cool, rational, orderly manner of thought. A tough man in a negotiation. His arrows put an end to frivolous suits. Of these ancient buildings only the stone footings remain along with various inscriptions valuable to scholars as 'authentic' texts of their period. The Roman stoa (a roofed colonnade) was added in somewhat later times to serve as a convenient market place for trade. Shops sold what we would call 'souvenirs' -- votives and momentoes. (Second image.) The home of the oracle was the Temple of Apollo, a huge rectangular structure the size of the Parthenon, of which only the columns on one of the shorter sides remain (fourth image, drawing). The Oracle -- the name given to the prophetess who was given hallucinatory herbs in order to see the future and produce some words of guidance, however vague, ambiguous or merely nonsensical -- was housed in a 'sacred' chamber at the room's far end. Here words were interpreted by priests.

Alexander asked the Oracle whether he would achieve victory in a coming battle. When the priestess charged with interpreting the ravings (or babblings? drugged incoherence?) failed to produce a clear reply, he dragged her by her hair until she shouted, "You're relentless!" OK, Alexander (on the way to being 'Great') concluded, I've got my answer. We explored the remains of Delphi last week, viewing the site of the Temple of Apollo (top photo), the still viable theater in which the tragedies of Sophocles were performed, and then climbing up to the "stadium" where the athletic games were held. No Oracle or priestess takes questions at Delphi there any more. The rise of Christianity eventually put an end to the practice some time in the 5th century AD. Just as well; I wasn't sure what to ask. The Oracle at Delphi was in many ways the center of the ancient Greek world. Compared to the 'body' of monuments, sanctuaries, memorials, and 'gifts' erected at Delphi in its long-ago heyday, the remains are skeletal. Petitioners and visitors climbed to the site to query the Oracle, or spectate at the celebratory "Pythian Games," along a sometimes steep route called "The Sacred Way." Messengers sent by the powerful to make their inquiries -- almost any important decision of state was referred there at one time -- but also business opportunities, law suits, marriage decisions, and who to back in the 800-meter at next year's Olympics -- climbed the Sacred Way, along with the great names of the era we remember. Alexander. Socrates. Buildings and statues were erected along the way to honor, or placate, the God Apollo. In the cabinet of the gods, Delphi was in his department. Apollo had a large brief; he was the god of the sun, but also the god of music; and later was chosen to symbolize a cool, rational, orderly manner of thought. A tough man in a negotiation. His arrows put an end to frivolous suits. Of these ancient buildings only the stone footings remain along with various inscriptions valuable to scholars as 'authentic' texts of their period. The Roman stoa (a roofed colonnade) was added in somewhat later times to serve as a convenient market place for trade. Shops sold what we would call 'souvenirs' -- votives and momentoes. (Second image.) The home of the oracle was the Temple of Apollo, a huge rectangular structure the size of the Parthenon, of which only the columns on one of the shorter sides remain (fourth image, drawing). The Oracle -- the name given to the prophetess who was given hallucinatory herbs in order to see the future and produce some words of guidance, however vague, ambiguous or merely nonsensical -- was housed in a 'sacred' chamber at the room's far end. Here words were interpreted by priests.

The Oracle's site, regarded as the 'center of the world,' was concretely symbolized by an elliptically shaped stone called the 'omphalos' (third image down). This site of the world navel was supposedly determined by Zeus's release of two eagles from opposite ends of the earth. Where they met was the center.

The Oracle's site, regarded as the 'center of the world,' was concretely symbolized by an elliptically shaped stone called the 'omphalos' (third image down). This site of the world navel was supposedly determined by Zeus's release of two eagles from opposite ends of the earth. Where they met was the center. The site also includes a stone theater in the round, where the plays of Sophocles were performed (last photo; not, however, Sophocles). A small temple-like structure, called the Treasury of the Athenians is regarded as the best preserved building. The history here is important, since this monumental building carried the gifts from 5th century Athens to commemorate either the fall of a tyrant and the establishment of Athenian democracy, or the victory over the Persians at the battle of Marathon that made the city's self-government possible. Either way, ground zero for Ancient Greece. Located about a two and a half hour drive from Athens, Delphi was the heart of the birthplace of the Western civilization. Prophecy is not central to modern, or monotheistic religions. But it is revealing that the civilization that birthed philosophy (the 'love of wisdom'), theater, naturalistic art, and natural science, and self-government among its gifts to a rational, humanistic way of life -- rather than superstition and tyranny -- sought to connect at its deepest levels with some power beyond the mind of man. To divinity. The gods. An oracle.

Published on June 05, 2016 22:42

June 2, 2016

The Garden of the Holy Valley: The Monastery of St. Anthony

I'm posting some photos of the recently restored monastery of St. Anthony of Quzhaya I took when Anne and I toured the Qadisha or “Holy Valley” in the north of Lebanon. The mountain side site is visibly dramatic and includes the use cave-like openings in mountain sides for religious spaces (seen in the third and fifth photos down). Partly built into a mountain, the monastery boasts spectacular forest and valley vistas.

I'm posting some photos of the recently restored monastery of St. Anthony of Quzhaya I took when Anne and I toured the Qadisha or “Holy Valley” in the north of Lebanon. The mountain side site is visibly dramatic and includes the use cave-like openings in mountain sides for religious spaces (seen in the third and fifth photos down). Partly built into a mountain, the monastery boasts spectacular forest and valley vistas.

St. Anthony of Quzhaya is one of the oldest monasteries of the valley of Qadisha (located in the Mount Lebanon range in the northern part of the country), and several hermitages attached to it date back to the 12th century AD. Today visitors can tour these places, including a library, hermitage cave, and a cave-like museum that houses, among other treasures, a 16thcentury printing press that printed a Bible in the Syriac language to escape the notice of Ottoman authorities (second photo). We encountered this ancient black-metal printing press and a sample of its work in a alphabet using diacritic marks I’ve never seen before – not Hebrew, not Greek, so quite possibly Syriac -- on our tour.

St. Anthony of Quzhaya is one of the oldest monasteries of the valley of Qadisha (located in the Mount Lebanon range in the northern part of the country), and several hermitages attached to it date back to the 12th century AD. Today visitors can tour these places, including a library, hermitage cave, and a cave-like museum that houses, among other treasures, a 16thcentury printing press that printed a Bible in the Syriac language to escape the notice of Ottoman authorities (second photo). We encountered this ancient black-metal printing press and a sample of its work in a alphabet using diacritic marks I’ve never seen before – not Hebrew, not Greek, so quite possibly Syriac -- on our tour. We also found huge urns of amphora design, with big handles on each side for carrying, that looked to me like something from 1000 BC when that design was common throughout the Mediterranean. The wall caption, however, stated they date only from the 18th century AD. Some parts of the world change more slowly.

According to Internet sources, St. Anthony Qozhaya owns large properties in the Qadisha Valley, in Ain-Baqra and in Jedaydeh, and is one of the richest monasteries of the Maronite monastic order.

According to Internet sources, St. Anthony Qozhaya owns large properties in the Qadisha Valley, in Ain-Baqra and in Jedaydeh, and is one of the richest monasteries of the Maronite monastic order.

The Maronite Christian church remains an important force in Lebanon. In a sense it is the principal reason that Lebanon exists today as an independent country, separate from Syria, to which it was historically affixed by earlier rulers, including the Ottoman Empire and the Romans. When France acquired protection over this part of the Middle East following the defeat of Ottoman Turkey in World War I, it drew borders around the Maronite Christian population and created the state of Lebanon as a homeland for the Maronites. Coastal cities including Beirut were affixed to the new state to make it economically viable.

The Maronite Christian church remains an important force in Lebanon. In a sense it is the principal reason that Lebanon exists today as an independent country, separate from Syria, to which it was historically affixed by earlier rulers, including the Ottoman Empire and the Romans. When France acquired protection over this part of the Middle East following the defeat of Ottoman Turkey in World War I, it drew borders around the Maronite Christian population and created the state of Lebanon as a homeland for the Maronites. Coastal cities including Beirut were affixed to the new state to make it economically viable.

Published on June 02, 2016 10:17

May 31, 2016

The Garden of the Forest: Old and New Cedars of Lebanon

Among the most famous trees of the Old World, the Cedars of Lebanon were especially sought after for their sturdiness by King Solomon when he built a new high temple in Jerusalem. Altogether cedars of Lebanon have been used for building by 15 world cultures, our guide told us, when we visited the Cedar Preserve in the Qadisha Valley region of northern Lebanon, known officially as the Forest of the Cedars of God (Horsh Arz el-Rab). More than any other variety of cedar. There are two kinds of cedar trees. The ‘candle’ cedars, which grow tall and straight like candles, and ‘table’ cedars, which spread their branches out to both sides like a table. The difference is the candle cedars are competing with surrounding trees for sunlight. The cedars uncrowded by other trees have room to let their branches stretch out.

Lebanese cedar grows very slowly. The new ones planted by the national initiative to restore the cedars to the country’s deforested mountain areas are about a foot and half tall after ten years. But they also live a very long time. Our guide, trained by the preservation initiative, pointed out a tree to us that has been growing in its mountain home for some 1,800 years, beginning before the birth of Alexander the Great. (Though not before the early days of the Maronite Christian church. We saw a dead cedar in which one branch had been sculpted to resemble the crucified Christ). The age is determined by an unintrusive cell sampling technique. All the old trees in the preserve are numbered, their health monitored, and their information kept on file – they are trees with, botanically speaking, medical records.

Lebanese cedar grows very slowly. The new ones planted by the national initiative to restore the cedars to the country’s deforested mountain areas are about a foot and half tall after ten years. But they also live a very long time. Our guide, trained by the preservation initiative, pointed out a tree to us that has been growing in its mountain home for some 1,800 years, beginning before the birth of Alexander the Great. (Though not before the early days of the Maronite Christian church. We saw a dead cedar in which one branch had been sculpted to resemble the crucified Christ). The age is determined by an unintrusive cell sampling technique. All the old trees in the preserve are numbered, their health monitored, and their information kept on file – they are trees with, botanically speaking, medical records.

The trees reproduce by seeds protected by seed covers resembling pine cones. They take three years to mature, and you can chart their progress easily because they pass through different color stages from green to light beige to a much darker pine cone-color as they mature. We saw tiny seedlings beginning life among the much of the protected forest floor.

The trees reproduce by seeds protected by seed covers resembling pine cones. They take three years to mature, and you can chart their progress easily because they pass through different color stages from green to light beige to a much darker pine cone-color as they mature. We saw tiny seedlings beginning life among the much of the protected forest floor.

We followed our guide from the top of the preserve down a carefully maintained path of switchbacks, admiring old and highly individualized cedars, until our path crossed a roadway, where we exited for lunch. As we left the outdoor restaurant, we could see ranks of young trees digging their roots into the flanks of the Mount Lebanon range.

We followed our guide from the top of the preserve down a carefully maintained path of switchbacks, admiring old and highly individualized cedars, until our path crossed a roadway, where we exited for lunch. As we left the outdoor restaurant, we could see ranks of young trees digging their roots into the flanks of the Mount Lebanon range.

Published on May 31, 2016 07:27

May 28, 2016

The Garden of Literary History: Visiting the Khalil Gibran Museum

Last week we visited the Khalil Gibran Museum in Bsharri, Lebanon, 120 kilometers from Beirut in the Mt. Lebanon range, a site dedicated to the Lebanese artist, writer and author of a classic work of popular wisdom literature, "The Prophet." The book offers quotable perspectives on big subjects such as his oft-cited pronouncement on children:

"Your children are not your children.

"Your children are not your children.They are the sons and daughters of Life's longing for itself…"

The museum is situated with a view of the Qadisha Valley, regarded by many as the most beautiful natural area in Lebanon. To get there we took part in a small bus tour with three Lebanese sisters and an Egyptian woman.

The museum is situated with a view of the Qadisha Valley, regarded by many as the most beautiful natural area in Lebanon. To get there we took part in a small bus tour with three Lebanese sisters and an Egyptian woman.

We don’t usually go places on paid public tours, but this one proved a great way to get someplace we wouldn’t have managed to get to on our own. We had an excellent Lebanese driver (no mean accomplishment; no tourist is eager to take on driving in Lebanon) and a superb guide as well. Since our fellow passengers were native Arabic speakers, our guide (let’s call him George) devoted himself about 80 percent of the time to that tongue, but was scrupulous in giving us all the tour information in English. It was important to me that we had somebody in charge who both knew what he was doing and was comfortable telling us what we needed to know in the only language I function in. The Lebanese tend to be both personable and polite, so it was no surprise George did very well by us. The other tourists were competent in English as well and good company. We went to see the Qadisha Valley region, regarded as perhaps the most beautiful spot in a country with lots of attractive mountain scenery. It’s a deeply cut valley winding around what appears – from the top – to be a very narrow stream, a mere glint of light in the viewfinder of my camera. One dirt road in to the valley bottom; many spots reached only by footpaths. Our tour (as we knew beforehand) stayed on top, taking us through the hills to the good places to look down on the scenery. We stopped in tiny picturesque Bcharre, where our driver picked ripe cherries (photo) from roadside trees; later he found us all fat, red roses. The valley was a hiding place for the locals, predominantly Maronite Christians, to get away from invaders or local enemies, George told us. He cited the example of the local Christians hiding here from the Mameluke enemies, rulers of this part of the Islamic empire during the period of Crusades. My suspicion is that the invasion by European Christian Crusaders (still called ‘the Franks’ in the Arab world) might have emboldened the Maronites to revolt against their Muslim rulers, provoking the wrath of the Mamelukes. The valley is a natural fortress; it’s hard to get an army down there. To escape from smaller parties the Lebanese climbed up hillsides to caves, then cut their rope ladders. No one was likely to pursue them any further.

We don’t usually go places on paid public tours, but this one proved a great way to get someplace we wouldn’t have managed to get to on our own. We had an excellent Lebanese driver (no mean accomplishment; no tourist is eager to take on driving in Lebanon) and a superb guide as well. Since our fellow passengers were native Arabic speakers, our guide (let’s call him George) devoted himself about 80 percent of the time to that tongue, but was scrupulous in giving us all the tour information in English. It was important to me that we had somebody in charge who both knew what he was doing and was comfortable telling us what we needed to know in the only language I function in. The Lebanese tend to be both personable and polite, so it was no surprise George did very well by us. The other tourists were competent in English as well and good company. We went to see the Qadisha Valley region, regarded as perhaps the most beautiful spot in a country with lots of attractive mountain scenery. It’s a deeply cut valley winding around what appears – from the top – to be a very narrow stream, a mere glint of light in the viewfinder of my camera. One dirt road in to the valley bottom; many spots reached only by footpaths. Our tour (as we knew beforehand) stayed on top, taking us through the hills to the good places to look down on the scenery. We stopped in tiny picturesque Bcharre, where our driver picked ripe cherries (photo) from roadside trees; later he found us all fat, red roses. The valley was a hiding place for the locals, predominantly Maronite Christians, to get away from invaders or local enemies, George told us. He cited the example of the local Christians hiding here from the Mameluke enemies, rulers of this part of the Islamic empire during the period of Crusades. My suspicion is that the invasion by European Christian Crusaders (still called ‘the Franks’ in the Arab world) might have emboldened the Maronites to revolt against their Muslim rulers, provoking the wrath of the Mamelukes. The valley is a natural fortress; it’s hard to get an army down there. To escape from smaller parties the Lebanese climbed up hillsides to caves, then cut their rope ladders. No one was likely to pursue them any further.

Our tour had three major stops: the Khalil Gibran Museum, the Cedars Reserve, and the St. Anthony Monastery. Gibran, taken to America by his mother as a child, studied art in the US and Europe. His work centered on the human figure in symbolic poses representing his own personal-mystical philosophy of human life – observers have noted the resemblance between his work and that of the prophetic art of William Blake – and he did not exhibit it publicly. After his death those looking after his legacy bought the property as a museum for his artwork and a resting place for his tomb. We took photos of the museum's exterior and views from one of the beautiful natural situations imaginable; no photos were permitted inside. We also visited the Cedars Preserver where the oldest Cedars of Lebanon are protected, studied, numbered and otherwise glorified, a site where the country is seeking to restore the cedar forests that once blanketed hillsides in this region. We saw the oldest of these trees, once reported to be 1,800 years old. The last stop was an even more dramatic site, the recently restored monastery of St. Anthony of Quzhaya, consisting of stone buildings built into the mountain side, with caves turned into places of worship. Today visitors can tour these places, including a library, hermitage cave, and a cave-like museum that houses a 16th century printing press that printed a Bible in the Syriac language to escape the notice of Ottoman authorities. I’ll post some images of this site and the Cedar Reserve in a later posting.

Our tour had three major stops: the Khalil Gibran Museum, the Cedars Reserve, and the St. Anthony Monastery. Gibran, taken to America by his mother as a child, studied art in the US and Europe. His work centered on the human figure in symbolic poses representing his own personal-mystical philosophy of human life – observers have noted the resemblance between his work and that of the prophetic art of William Blake – and he did not exhibit it publicly. After his death those looking after his legacy bought the property as a museum for his artwork and a resting place for his tomb. We took photos of the museum's exterior and views from one of the beautiful natural situations imaginable; no photos were permitted inside. We also visited the Cedars Preserver where the oldest Cedars of Lebanon are protected, studied, numbered and otherwise glorified, a site where the country is seeking to restore the cedar forests that once blanketed hillsides in this region. We saw the oldest of these trees, once reported to be 1,800 years old. The last stop was an even more dramatic site, the recently restored monastery of St. Anthony of Quzhaya, consisting of stone buildings built into the mountain side, with caves turned into places of worship. Today visitors can tour these places, including a library, hermitage cave, and a cave-like museum that houses a 16th century printing press that printed a Bible in the Syriac language to escape the notice of Ottoman authorities. I’ll post some images of this site and the Cedar Reserve in a later posting.

Published on May 28, 2016 15:23

The Garden of Literary History: Visiting the Kahlil Gibran Museum

Last week we visited the Kahlil Gibran Museum in Bsharri, Lebanon, 120 kilometers from Beirut in the Mt. Lebanon range, a site dedicated to the Lebanese artist, writer and author of a classic work of popular wisdom literature, "The Prophet." The book offers quotable perspectives on big subjects such as his oft-cited pronouncement on children:

"Your children are not your children.

"Your children are not your children.They are the sons and daughters of Life's longing for itself…"

The museum is situated with a view of the Qadisha Valley, regarded by many as the most beautiful natural area in Lebanon. To get there we took part in a small bus tour with three Lebanese sisters and an Egyptian woman.

The museum is situated with a view of the Qadisha Valley, regarded by many as the most beautiful natural area in Lebanon. To get there we took part in a small bus tour with three Lebanese sisters and an Egyptian woman.

We don’t usually go places on paid public tours, but this one proved a great way to get someplace we wouldn’t have managed to get to on our own. We had an excellent Lebanese driver (no mean accomplishment; no tourist is eager to take on driving in Lebanon) and a superb guide as well. Since our fellow passengers were native Arabic speakers, our guide (let’s call him George) devoted himself about 80 percent of the time to that tongue, but was scrupulous in giving us all the tour information in English. It was important to me that we had somebody in charge who both knew what he was doing and was comfortable telling us what we needed to know in the only language I function in. The Lebanese tend to be both personable and polite, so it was no surprise George did very well by us. The other tourists were competent in English as well and good company. We went to see the Qadisha Valley region, regarded as perhaps the most beautiful spot in a country with lots of attractive mountain scenery. It’s a deeply cut valley winding around what appears – from the top – to be a very narrow stream, a mere glint of light in the viewfinder of my camera. One dirt road in to the valley bottom; many spots reached only by footpaths. Our tour (as we knew beforehand) stayed on top, taking us through the hills to the good places to look down on the scenery. We stopped in tiny picturesque Bcharre, where our driver picked ripe cherries (photo) from roadside trees; later he found us all fat, red roses. The valley was a hiding place for the locals, predominantly Maronite Christians, to get away from invaders or local enemies, George told us. He cited the example of the local Christians hiding here from the Mameluke enemies, rulers of this part of the Islamic empire during the period of Crusades. My suspicion is that the invasion by European Christian Crusaders (still called ‘the Franks’ in the Arab world) might have emboldened the Maronites to revolt against their Muslim rulers, provoking the wrath of the Mamelukes. The valley is a natural fortress; it’s hard to get an army down there. To escape from smaller parties the Lebanese climbed up hillsides to caves, then cut their rope ladders. No one was likely to pursue them any further.

We don’t usually go places on paid public tours, but this one proved a great way to get someplace we wouldn’t have managed to get to on our own. We had an excellent Lebanese driver (no mean accomplishment; no tourist is eager to take on driving in Lebanon) and a superb guide as well. Since our fellow passengers were native Arabic speakers, our guide (let’s call him George) devoted himself about 80 percent of the time to that tongue, but was scrupulous in giving us all the tour information in English. It was important to me that we had somebody in charge who both knew what he was doing and was comfortable telling us what we needed to know in the only language I function in. The Lebanese tend to be both personable and polite, so it was no surprise George did very well by us. The other tourists were competent in English as well and good company. We went to see the Qadisha Valley region, regarded as perhaps the most beautiful spot in a country with lots of attractive mountain scenery. It’s a deeply cut valley winding around what appears – from the top – to be a very narrow stream, a mere glint of light in the viewfinder of my camera. One dirt road in to the valley bottom; many spots reached only by footpaths. Our tour (as we knew beforehand) stayed on top, taking us through the hills to the good places to look down on the scenery. We stopped in tiny picturesque Bcharre, where our driver picked ripe cherries (photo) from roadside trees; later he found us all fat, red roses. The valley was a hiding place for the locals, predominantly Maronite Christians, to get away from invaders or local enemies, George told us. He cited the example of the local Christians hiding here from the Mameluke enemies, rulers of this part of the Islamic empire during the period of Crusades. My suspicion is that the invasion by European Christian Crusaders (still called ‘the Franks’ in the Arab world) might have emboldened the Maronites to revolt against their Muslim rulers, provoking the wrath of the Mamelukes. The valley is a natural fortress; it’s hard to get an army down there. To escape from smaller parties the Lebanese climbed up hillsides to caves, then cut their rope ladders. No one was likely to pursue them any further.

Our tour had three major stops: the Kahlil Gibran Museum, the Cedars Reserve, and the St. Anthony Monastery. Gibran, taken to America by his mother as a child, studied art in the US and Europe. His work centered on the human figure in symbolic poses representing his own personal-mystical philosophy of human life – observers have noted the resemblance between his work and that of the prophetic art of William Blake – and he did not exhibit it publicly. After his death those looking after his legacy bought the property as a museum for his artwork and a resting place for his tomb. We took photos of the museum's exterior and views from one of the beautiful natural situations imaginable; no photos were permitted inside. We also visited the Cedars Preserver where the oldest Cedars of Lebanon are protected, studied, numbered and otherwise glorified, a site where the country is seeking to restore the cedar forests that once blanketed hillsides in this region. We saw the oldest of these trees, once reported to be 1,800 years old. The last stop was an even more dramatic site, the recently restored monastery of St. Anthony of Quzhaya, consisting of stone buildings built into the mountain side, with caves turned into places of worship. Today visitors can tour these places, including a library, hermitage cave, and a cave-like museum that houses a 16th century printing press that printed a Bible in the Syriac language to escape the notice of Ottoman authorities. I’ll post some images of this site and the Cedar Reserve in a later posting.

Our tour had three major stops: the Kahlil Gibran Museum, the Cedars Reserve, and the St. Anthony Monastery. Gibran, taken to America by his mother as a child, studied art in the US and Europe. His work centered on the human figure in symbolic poses representing his own personal-mystical philosophy of human life – observers have noted the resemblance between his work and that of the prophetic art of William Blake – and he did not exhibit it publicly. After his death those looking after his legacy bought the property as a museum for his artwork and a resting place for his tomb. We took photos of the museum's exterior and views from one of the beautiful natural situations imaginable; no photos were permitted inside. We also visited the Cedars Preserver where the oldest Cedars of Lebanon are protected, studied, numbered and otherwise glorified, a site where the country is seeking to restore the cedar forests that once blanketed hillsides in this region. We saw the oldest of these trees, once reported to be 1,800 years old. The last stop was an even more dramatic site, the recently restored monastery of St. Anthony of Quzhaya, consisting of stone buildings built into the mountain side, with caves turned into places of worship. Today visitors can tour these places, including a library, hermitage cave, and a cave-like museum that houses a 16th century printing press that printed a Bible in the Syriac language to escape the notice of Ottoman authorities. I’ll post some images of this site and the Cedar Reserve in a later posting.

Published on May 28, 2016 15:23

May 26, 2016

The Garden of the Seasons: Parting With the Plants

Now that the warm spring weather has come, drawing mature growth from the plants I associate with the end of May, I’m really worried that time will go by too fast and we’ll miss too much. For the first time since our move to Quincy and the beginning our perennial garden there, Anne and I have gone away on vacation during the heart of the growing season in the northeastern part of the United States. Other years we’ve taken vacation trips that remove us from home for a week or two in late winter or early spring. We’ve gone to Lebanon, where Sonya lives, in February, March, early April two years ago, and on our first trip in October, when it felt like summer there but not oppressively (not far from July in Massachusetts). So this time is different. We left last Friday on the day the first of the clematis blooms opened (top photo), just enough to reveal its pointed-star shape. We have two plants of this viney climber that gives the front of the house a small town rural look in late May.

Now that the warm spring weather has come, drawing mature growth from the plants I associate with the end of May, I’m really worried that time will go by too fast and we’ll miss too much. For the first time since our move to Quincy and the beginning our perennial garden there, Anne and I have gone away on vacation during the heart of the growing season in the northeastern part of the United States. Other years we’ve taken vacation trips that remove us from home for a week or two in late winter or early spring. We’ve gone to Lebanon, where Sonya lives, in February, March, early April two years ago, and on our first trip in October, when it felt like summer there but not oppressively (not far from July in Massachusetts). So this time is different. We left last Friday on the day the first of the clematis blooms opened (top photo), just enough to reveal its pointed-star shape. We have two plants of this viney climber that gives the front of the house a small town rural look in late May.

The tightly rolled iris blossoms (photo at left) in the back garden were just about to unfurl themselves as well. (They've bloomed by now: oh dear, I'm missing it.) One was just beginning the blooming process when I caught it on camera Friday afternoon. People aren’t blue on this planet, but I’ll confess to finding a resemblance in the bud’s mis-en-scene profile to Boston Celtics guard Marcus Smart. The poppies, crammed into a portion of the front garden are beginning to take over all available space (second photo down). They must like growing thickly; the other option I’ve known from this variety, Icelandic poppies, is not to grow at all, so I’m glad it’s chosen to proliferate in its erratic long-necked style. We see lots of poppies, same color, about the tenth of the size growing close to the ground in Lebanon’s hills.

The tightly rolled iris blossoms (photo at left) in the back garden were just about to unfurl themselves as well. (They've bloomed by now: oh dear, I'm missing it.) One was just beginning the blooming process when I caught it on camera Friday afternoon. People aren’t blue on this planet, but I’ll confess to finding a resemblance in the bud’s mis-en-scene profile to Boston Celtics guard Marcus Smart. The poppies, crammed into a portion of the front garden are beginning to take over all available space (second photo down). They must like growing thickly; the other option I’ve known from this variety, Icelandic poppies, is not to grow at all, so I’m glad it’s chosen to proliferate in its erratic long-necked style. We see lots of poppies, same color, about the tenth of the size growing close to the ground in Lebanon’s hills.

The general impression of fullness is what I like perhaps most of all from the late spring perennial garden. The greenery is large enough to show its style, and all the shapes and sizes and multi-varied approaches to growing in green plant photosynthesis style begin to crowd abundantly together. It’s a texture; always changing, always different. Always worth looking at as one of earth’s various and seemingly limitless ways of covering itself. And we all go around humming Louis Armstrong’s immortal line “what a beautiful world it is.” What happens next, even last year, spring of 2015, when I was going absolutely nowhere (we had been gifted with some much needed late winter days in Florida), I realize I was still worried about time passing too fast to properly appreciate everything that goes on in this special season. I’m posting here (below) the poem that I wrote then. As for the garden I left behind in Massachusetts for two weeks of the best of the growing season, it will just have to take care of itself.

The general impression of fullness is what I like perhaps most of all from the late spring perennial garden. The greenery is large enough to show its style, and all the shapes and sizes and multi-varied approaches to growing in green plant photosynthesis style begin to crowd abundantly together. It’s a texture; always changing, always different. Always worth looking at as one of earth’s various and seemingly limitless ways of covering itself. And we all go around humming Louis Armstrong’s immortal line “what a beautiful world it is.” What happens next, even last year, spring of 2015, when I was going absolutely nowhere (we had been gifted with some much needed late winter days in Florida), I realize I was still worried about time passing too fast to properly appreciate everything that goes on in this special season. I’m posting here (below) the poem that I wrote then. As for the garden I left behind in Massachusetts for two weeks of the best of the growing season, it will just have to take care of itself. Hungry Summer

I feel about the birds on the cherry tree

tearing off its blinding white blossoms

As I do about the easy spring days

of early May when earth simmers up

the year's first soothing seventies

Now that spring has finally put a bare foot down

I fear the beast of summer, the swish of its heavy legs

And those large happy jaws chewing through

days of children by the shore

their voices the eerie cries of disappearing angels

Published on May 26, 2016 08:41

May 19, 2016

The Garden of May: A Setting for the 'Immortality Ode

The best of poets have always philosophized over flowers. Spring, perhaps the month of May especially, is as good a time as any to consider the mysteries of birth, time, and decay.

Where do we come from? And the equally fundamental question: Why is there something rather than nothing?

William Wordsworth, perhaps the greatest of the English Romantic poets, also known as a poet of Nature par excellence, considered these questions in his celebrated Immortality Ode (full title: "Ode: Intimations of Immortality").

Like the works of Shakespeare, the poem is full of phrases that step out of their original context to find a life of their own in common language (sometimes in an ironic fashion). Ever hear, or read, "trailing clouds of glory"? Here's the sentence in which it appears in the Ode. We are born into this world, the poet says,

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy.

The poem appears to say that when a new "soul" is born into this life, it carries some initial remembrance of the eternal realm from which the child came. That remembrance, or "glory," trails some ways through our childhood on imperfect earth, this realm of growth and decline, birth and death: "...he beholds the light, and whence it flows,/ He sees it in his joy."

Which (to me) glances at that sense new parents sometimes have of the otherworldly aura of a newborn. What are those eyes looking at that we cannot see? For Wordsworth, it's that special connection with the higher realm from which we are "thrown" at birth that cements a young child's oneness with nature. In this poem, the poet conjoins his 'religion of nature' -- his belief in nature as the source of human goodness -- with the orthodox Christian faith that was the be and end all of religion in his society. Not to believe in this orthodoxy was to be damned as an atheist, the charge Shelley and other English "free thinkers" would face. Wordsworth bows openly to orthodoxy in his reference to God as "our home." But the poem's assertion of the that infantile apprehension of the holy, of "heaven" lying about one, is pure Romantic. It's akin to Rousseau's belief that children are born not in sin, but in purity -- anathema to the religious in his own country. To Wordsworth, those God-given 'clouds of glory' empower the child's love for the physical world, the unself-consciousness embrace of nature often noted in very young children. Rolling in the grass, playing in the mud, carrying bugs around in a pocket, delighting in the presence of animals. The heavenly "light" the child beholds in nature, the poem continues, transforms him into "Nature's priest." In those early years of mortal existence, Wordsworth writes, he "still is Nature's priest/ And by the vision splendid/ Is on his way attended..." The Immortality Ode is Wordsworth's fullest statement of reconciliation between his belief in goodness of nature and the facts of life. Those infantile heavenly clouds dissipate in the full light of day -- the mortal, material world that Wordsworth says in a much quoted phrase from another poem "is too much with us" as we grow into our mature lives. We're no longer one with nature, no longer its devoted priest, as the demands of 'real life' rub their daily erasures over the magic of the wonder years. And yet, and here is the poem's great and moving attempt to reconcile transcendent belief and sad experience, as the poet wrestles with the Romantic problem of mortal life -- how to accept that youthful "light" (vigor, hope, optimism) grows progressively dim as we mature and age and suffer losses. In short, if what Wordsworth has told us about the human state in the early part of this poem (and the best of his other poems) is true, then life inevitably goes downhill. The ode turns then to what we might call 'the consolations of philosophy.' (A phrase not invented by Wordsworth, or Shakespeare, but by a Saxon forebear named Boethius.) When -- and this is where I began this consideration, with the special appreciation of May as the most transformational, generative, birth-happy month -- the Immortality Ode stages the reconciliation of mortal man with the inevitable loss of exaltation and ecstasy (whether spiritual or poetic or simply 'natural'), he chooses May for his epiphany. "Then sing, ye birds," the poet writes, invoking the spirits of the season, then adds bounding lambs, and the music of the "tabor" to summon those those able to perceive through the "heart" (that most poetic organ):

Then sing, ye birds, sing, sing a joyous song! And let the young lambs bound As to the tabor's sound! We in thought will join your throng, Ye that pipe and ye that play, Ye that through your hearts to-day Feel the gladness of May!

(And indeed the month of May has been unusually birdful around these parts. We've had a mockingbird camp out for half-days at a time. The cardinal and the other songbirds have been spring-singing steadily, and some little creature chirped for days on end in the tree or the telephone line above the driveway, seldom taking wing for more a half dozen feet.. though I suspect the burden of his song might be something like "I am so lost." ) In what would later be called the confessional mode, Wordsworth then speaks in the first person to acknowledge the "lost" radiance even a fulltime poet must acknowledge as mortal's fate.

What though the radiance which was once so bright Be now for ever taken from my sight, Though nothing can bring back the hour Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower;

How about "splendor in the grass"? Have you heard that one; the title of a book (and soon after a major movie) that 60 years ago made bold to treat the sex motive in human conduct. As for the absence of "glory in the flower," don't take this too much to heart, as we will see.

We will grieve not, rather find Strength in what remains behind; In the primal sympathy Which having been must ever be; In the soothing thoughts that spring Out of human suffering; In the faith that looks through death,

The consolation appears to lie in improved morals, plus some wisdom. We find "strength in what remains behind," in sympathy, in the hard to buy notion that "soothing thoughts" that spring from suffering are a source of strenght, and in a faith stronger than death.

And then, at the end, if all else fails -- to pierce the shell we necessarily thicken around ourselves to defend against "human suffering" and, I suspect, the growing awareness of oncoming death ... there are flowers.

However tepid some of these prior consolations may appear to us, the last stanza pays for all. After the tone of these rationalizations ("which having been must ever be"), what bursts forth is tried and true lover's love song.Wisdom colors the poet's vision, but an aging, studied, lived passion is even more passionate, these lines tell us, even more life-affirming. How about that little phrase "too deep for tears"? Heard that one? Here it is, fully earned. And you can't miss the blossom in this final vision:

And O ye Fountains, Meadows, Hills, and Groves,

Forebode not any severing of our loves!

Yet in my heart of hearts I feel your might;

I only have relinquish'd one delight 195 To live beneath your more habitual sway.

I love the brooks which down their channels fret,

Even more than when I tripp'd lightly as they;

The innocent brightness of a new-born Day

Is lovely yet; 200 The clouds that gather round the setting sun

Do take a sober colouring from an eye

That hath kept watch o'er man's mortality;

Another race hath been, and other palms are won.

Thanks to the human heart by which we live, 205 Thanks to its tenderness, its joys, and fears,

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.

Published on May 19, 2016 22:30

May 17, 2016

The Garden of Verse: More Poems Blooming, So Quickly in May

As the month advances I discover more poetic flowers blooming in the May's Verse-Virtual.com, the online poetry journal:

As the month advances I discover more poetic flowers blooming in the May's Verse-Virtual.com, the online poetry journal:The poetry of great truths in J.C. Elkin's moving and formally appealing poem "Keening for Eve" found in lines such as:"...if progress can ever describe modern deaths as acceptable third world reality.

Caesar, Robespierre, Frankenstein’s Shelley lost moms. Stonewall Jackson, too.

And half a million more this year will die in every locality." Mary Shelley's mother, Mary Wollstonecraft (just to mention one such death), was probably the first successful professional author in the English language, and certainly one of the first feminists, her early death an incredible loss. Elkin's poem "Almost Fledglings" about two baby birds blown from their nest draws on the truth that we feel the little tragedies that cross our path just as we do the big ones -- and sometimes even more deeply.. "...one is white as an angel, skim milk shades drawn over eyes. The other, purpling,

inflates – deflates, an avian respirator." Beautiful writing puts a face on an ordinary disaster.

David Chorlton's poem "Lyric Botany" imagining "the namers of flowers" is a thorough pleasure, with its elegant allusions to an imaginary etymology. The poem's language is a joy: "Their work

is to cross-breed language

so that beavertail lives in earth

as it does in water,plant alliteration

or roadsides with the brittlebush,

and experiment with consonants

until fleabane and madrone grow

from the alphabet's old loam."

His poem "Nyctophobia" (an "irrational fear of night" a new word for me) gives us the poetry of the horror film. The elegance of the language here has the quality of a guilty pleasure as we sense a shudder of truth in the poem's description of 'the mechanical night': "even the mechanical night

is a low hum

along the freeways, broken

by emergencies,

spinning lights

and insomnia running out

of control."

The entire beautifully packaged group of DeWitt Clinton's poems illustrates the available range of working on a theme such as flowers, or gardens, or spring. Along with their perfectly chosen illustrations and title allusions to the poems of Su Tung Po the group captures the wonder of an everyday world it's easy to lose sight of. The poem titled "In a Waiting Room Overlooking the Lake, I See a Bouquet of May Flowers, and Read Su Tung P’o’s 'Begonias'" seems to me to capture the eternal flicker in the temporal flow as the poet recalls bringing home a yellow hibiscus and leaving in wrapped in a plastic bag to protect against frost."Alone on the porch next to the snow

The entire beautifully packaged group of DeWitt Clinton's poems illustrates the available range of working on a theme such as flowers, or gardens, or spring. Along with their perfectly chosen illustrations and title allusions to the poems of Su Tung Po the group captures the wonder of an everyday world it's easy to lose sight of. The poem titled "In a Waiting Room Overlooking the Lake, I See a Bouquet of May Flowers, and Read Su Tung P’o’s 'Begonias'" seems to me to capture the eternal flicker in the temporal flow as the poet recalls bringing home a yellow hibiscus and leaving in wrapped in a plastic bag to protect against frost."Alone on the porch next to the snowShovel, rusting table and chairs,

the raccoons pause before the light

surprises them with blooms and eyes." The image of the summer-bloomer next to the snow shovel is practically a poem in itself. (And I admit being partial to the mention of this flower since I still have the yellow hibiscus I bought last year, keeping inside all winter and still hesitating over when it will be safe enough to put outdoors again.) Clinton's poem" After a Long Run Along the Lakefront,I Try to Nap with Lu Yu’s “Phoenix Hairpins” speaks to this eternal longing as well. "Daylilies have opened in our village

Soothing what I can’t do myself.

I’d like to be here

When there’s no more time

To let this ink seep into something

That you might want

As something precious, forever."

I love Barbara Crooker's personifications of flowers. Don't we all do this sometimes? See others -- or ourselves? -- in plants and other elements of nature, despite having been taught that anthropomorphizing was some sort of sin against reason. "The Hour of Peonies," a praise song for this showy favorite of gardeners, embraces the sensuality of this flower, comparing them to Renoir's fleshy bathers: "And so are these flowers,

an exuberance of cream, pink, raspberry, not a shrinking violet among them.

They splurge, they don’t hold back, they spend it all." I like the other poems in this group too, as I also like their subjects. The big costume-party iris, a ballet in a flower, rising from a plant that works all year to give us one week of beautiful performance: "and sometimes we awaken [the poem notes]

from the dull green stalk of habit." And this inspired description of a dianthus: "My mother comes back as a dianthus,

only this time, she’s happy, smelling like cloves,

fringed and candy-striped with a ring of deep rose

that bleeds into the outer petals." And of the Rosa Multiflora: "Now they ramble unchecked, grow in waste areas, weeds, pests, nuisances.

In June, thousands and thousands of white blossoms light

my back path." I share this experience of the wild rose. I can't get rid of them; and then I don't want to. That's spring for you, too. It's beautiful because it keeps moving, but why does it have to move so fast?

Published on May 17, 2016 20:30

May 16, 2016

The Garden of Experience: Libraries and Book Clubs

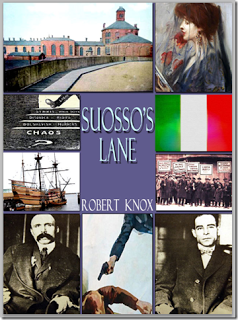

My thanks to Carver Library, and librarian Amy Shepherdson, for hosting "Suosso's Lane" and me on a beautiful Saturday afternoon. We had a lively question and answer session after I finally finished talking.

My thanks to Carver Library, and librarian Amy Shepherdson, for hosting "Suosso's Lane" and me on a beautiful Saturday afternoon. We had a lively question and answer session after I finally finished talking. And I met a couple of folks who had strong family memories of life on Suosso's Lane or elsewhere in the North Plymouth neighborhood.

One person told me about living across from the Amerigo Vespucci Hall on Suosso's Lane. This Italian-American clubhouse had a low a profile when I lived in Plymouth, but back in the day (Vanzetti's day) it housed the 1916 strike meeting when charismatic Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani came to address the Plymouth Cordage Company strikers.

As an American place name, the Vespucci Hall retains its status because of its connection to Vanzetti. If you Google it, you find Beltrando Brini's marvelous oral history recollection of Vanzetti and his family (from the book "Anarchist Voices") in which he states:

As an American place name, the Vespucci Hall retains its status because of its connection to Vanzetti. If you Google it, you find Beltrando Brini's marvelous oral history recollection of Vanzetti and his family (from the book "Anarchist Voices") in which he states: "There was also a social hall on Suosso's Lane, the Amerigo Vespucci Hall, but that was for the general community, not for the anarchists."

(Just for you information, Google's second mention of the Suosso's Lane Vespucci Hall comes from an earlier post in this blog.)

I want to say thanks also to the "men's" book club in Plymouth that invited me to sit in at their meeting last weekend to discuss "Suosso's Lane" (and fed me). I was very flattered that a group that tends toward serious nonfiction chose my novel -- 'historical fiction' as one of the members referred to it (the terms 'mystery' and 'potboiler' also came up) -- as its book for discussion.

Their questions were penetrating. "Do you also write poetry?" one of the group's good doctors asked.

Bing! Bing! Bing! A little birdie comes down with an envelope, and cash is awarded.

Other questions: Did I have a role model for the character of Lavinia? No, I just knew I wanted her to be very smart, very articulate, and the proto-feminist of her era, which is to say a suffragist. Someone who could stand up to Vanzetti on intellectual grounds, while brushing off the snubs of her own old-line Plymouth community.

Members also shared with me their personal acquaintance with the Sacco-Vanzetti case, mostly dating from older family members -- the left-leaning intellectuals of earlier generations. How is it that members of earlier generations could proudly call themselves adherents to the socialist workers party or progressive labor or even the American Communist Party -- but since mid-20th century America it has not respectable and in fact materially dangerous to acknowledge any of these connections -- or even these once widely-shared beliefs?

The answer in practical, historical terms, of course, is McCarthyism and is proscription of 'Communist' ideas (for instance, atheism). But McCarthyism is sixty-five years old (ready to sit in a rocker and collect Social Security), so can't we finally get past this mental straitjacket fitted over the American political mind?

Other questions. My 21st century character Mill -- was he based on myself. Oh no, I hope not... But yeah, there's something to that idea. I have a guy increasingly obsessed with the Vanzetti story, his time in America, his particular 'once upon a time in America...'

(Digression warning: Myths, legends, and folk tales all happen in "the past." We romanticize the past; it's the place we go to 'romanticize.' We're more likely to be afraid of the future. If we have a place in the culture for "Angels in America," why can't we have a place, intellectually at least, for "Anarchists in America"?)

So, yes, as a reporter and then just as a reader before I started writing a book based on the Vanzetti experience, I did grow increasingly fascinated by the vivid history of his life and times.

And I'm flattered, and happy, that others have found something to engage their attention and provide some storytelling pleasure in the book that derives my own attraction to a largely forgotten piece of local, and American, history.

Published on May 16, 2016 13:17

May 12, 2016

The Garden of Local News: 'Why I Wrote This Book'

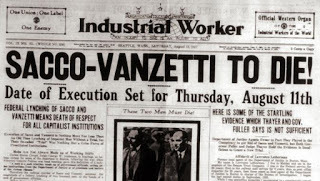

When I speak at libraries about "Suosso's Lane," I begin with a brief introduction connecting the novel to the infamous Sacco and Vanzetti case. (I'll be speaking at Carver Public Library, 2 Meadowbrook Way, Carver MA this Saturday, May 14, 1 p.m.)

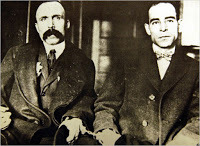

When I speak at libraries about "Suosso's Lane," I begin with a brief introduction connecting the novel to the infamous Sacco and Vanzetti case. (I'll be speaking at Carver Public Library, 2 Meadowbrook Way, Carver MA this Saturday, May 14, 1 p.m.)  To explain the origins of the case I read my account in “Suosso’s Lane” of the 1920 crime for which the two men, Italian immigrants and professed anarchists, were found guilty and later executed. The crime was sensational daylight robbery of a shoe factory payroll and the murder of two payroll officers planned and executed in the

To explain the origins of the case I read my account in “Suosso’s Lane” of the 1920 crime for which the two men, Italian immigrants and professed anarchists, were found guilty and later executed. The crime was sensational daylight robbery of a shoe factory payroll and the murder of two payroll officers planned and executed in theway as a professional criminal gang would do it. The chief of the Massachusetts state police said as much to the prosecution after Sacco and Vanzetti were charged with the crime. You've got the wrong guys, he said. The state prosecutors responded by removing him from the case and putting it into the hands of a small town police chief whose theory that anarchists were responsible for the robbery led to the arrests.

Next, I address the question that readers almost ask an author: Why did you write this book? A good question, requiring a somewhat lengthy answer. After an outrageously biased trial in 1921 Sacco and Vanzetti, both of whom had witnesses from their own immigrant community placing them elsewhere on the day of the crime — “the Italians?” the state's governor would later say, “you can't believe them” — were convicted of murder. Their defense raised money to pay for legal challenges, delaying their execution until 1927. By that time the case had become an international cause celebre. In Europe, everyone from Albert Einstein to the Pope signed petitions demanding a new trial or a pardon or the outright release of Sacco and Vanzetti. Their cause was taken up by worker movements worldwide and demonstrations in their behalf were held literally all over the world. American justice was widely condemned because of this case.

I was aware of the Sacco-Vanzetti case in general terms when I moved to Plymouth MA, home of the Pilgrims, and began work as an editor and reporter for a community newspaper called the Old Colony Memorial. But I did not know that Bartolomeo Vanzetti lived in Plymouth at the time of his arrest. Plymouth is very conscious of its Pilgrim history, there are statues and memorials and plaques throughout the old town center, but it pays no attention whatsoever to one of the principals in the Trial of the Century 100 years ago.

As a reporter I knew that the Sacco-Vanzetti case had been a big deal everywhere and that many nonfiction books have been written about it. But ‘Vanzetti in Plymouth’ is the local angle — and I was a local reporter. Working on a local history project for my newspaper, I looked into what was known about Vanzetti’s life in Plymouth by scanning through microfilmed editions of my own paper and other newspapers in the Plymouth library. (I do love libraries; I wouldn’t be speaking about this book if it wasn’t for libraries).

I also read the most influential books on the case. As I learned more I grew to believe that the story of Vanzetti’s life in Plymouth — he spent five years there — offered a multi-faceted opening into a bigger story of what life was like for the industrial working class in Plymouth, and the rest of America, a century ago, a story that later generations are forgetting. It's a story that raises raising enduring issues in American society and politics, such as immigration, the negative stereotyping of national (or ethnic and religious) groups as undesirable others, bias in the criminal justice system, and the growing gap between rich and poor.

“Suosso’s Lane,” named for the street in North Plymouth where Vanzetti lived in an immigrant neighborhood of mostly factory workers, dramatizes Vanzetti’s life in America, his outrage over the injustices he saw inflicted upon the working poor, and his growing commitment to the revolutionary anarchist cause. But the novel goes beyond recreating the historical past to connect Vanzetti’s story, and his world, to our own world by also telling a 21st century story (also set in Plymouth) of people dealing today with many of the same issues. Despised "outsider" immigrant groups. An economic system that shuts the door to the “American dream” by exploiting the working poor. The centralization of political and monetary power in the hands of a few.

The main characters in the contemporary story are Mill Becker, a young history teacher in his first real academic job, who moves with his wife into the house on Suosso’s Lane where Vanzetti once lived. A nosy local reporter named Mo Jeter (whose working life, by the way, is a lot more “adventurous” than mine ever was), who is investigating a real cold case, the 60-year-old suspicious death of a Plymouth policeman. How can this death connect to Sacco-Vanzetti case? Well, that’s what fiction is for.

And finally Ike Murisi, a ‘new immigrant’ who works at a big box store (I’m not allowed to name for legal reasons) and discovers parallels to Vanzetti’s story in his own life. While Ike takes low-paying service job to cobble together a living for himself and his wife, the criminal justice system complicates his life, and self-serving politicians seek only to make things harder for people like him.

“Suosso’s Lane” is a big book. A frankly ambitious novel. It took me years to bring it to publication and I couldn’t be happier to see it finally in print. It’s now available as both an ebook and a paperback from the publisher, Web-e-Books.com.

Published on May 12, 2016 10:11