Robert Knox's Blog, page 47

November 16, 2015

The Garden Of Humanity: On Being Paris

On Being Paris

On Being ParisEveryone is Paris,I as much as anyone. I'm that little bridge over the Seine fenced with all those locked-up hearts. But not everyone is Beirut,or Syria.Even I am not that part of the south suburbs of Beirut, where two bombs killed 43 (and counting).I had confused it with the Dahiyawhere we had once been treated to an Iftar meal after sundown in Ramadanin a home where the power went out, only briefly, on a very warm night in October,and where Israel's bombers destroyed blocks of apartments and small shopsin the summer of 2006. But no, Burj al-Barajneh, described in news reports as "a stronghold of the Shia Islamist" Hezbollah movement,

though in fact a neighborhood where people live and shop,

is near the Palestinian 'camps' (three generations and counting)of Sabra and Shatila where old men, women and children were slaughtered after the Israeli invasion of 1982.

They are not like us, the Shia of Lebanon, the Iraqis, the Syrianrefugees who live in the alleys of Beirut,the Palestinian refugees who once lived in 'camps' in Syria, and now live anywhere they can.Their lives are not so materially rich(though they wish they were),they do not get their ideas from media and follow breaking events on television (but of course they do)they do not gawp at photographs of the latest Paris fashions (but of course they do)They do not struggle to get their children enough years of school, in a good school,

even if taught in a tongue not spoken in their home,

for a shot at a prosperous future, as we would surely do if we were in their shoes(yet that is exactly what they do, and what we,the lucky ones, are not forced to).

Still, they are not like us, and some of them are refugees massing before the gates of Europe. And one of them (we are told)brought a gun to Paris.

Good. Tell us who to hate, So we will know where we are.Back in the same old hell.

Published on November 16, 2015 21:14

November 13, 2015

November's Garden: Quick Peeks at a Fading Grandeur

Sunset comes so early it's gone before I remember to look at it. On the way to the golf course there's a tiny pond just big enough for a quartet of ducks to spin around one another in circles. Go a couple hundred feet farther and the city skyline rises up above the November treeline. Back home, the Japanese 'red' maple delivers on its promise.

The sun slips away again, its patented standard time disappearing act, not bothering to tint a cloudless sky.The Spartina grass in the salt marsh across the road from the harbor gilds in the light of a low-angled sun.

The sun slips away again, its patented standard time disappearing act, not bothering to tint a cloudless sky.The Spartina grass in the salt marsh across the road from the harbor gilds in the light of a low-angled sun.

The leaves on the weeping cherry tree do their disappearing act, by stages. Some pale yellow, some bronze. Nabokov said there are a hundred shades of yellow. He must have been thinking of autumn.

The leaves on the weeping cherry tree do their disappearing act, by stages. Some pale yellow, some bronze. Nabokov said there are a hundred shades of yellow. He must have been thinking of autumn.

The last of the perennials, the spotted toad lilies, maked a belated appearance. Autumn, we hardly knew ye.

The last of the perennials, the spotted toad lilies, maked a belated appearance. Autumn, we hardly knew ye.

Published on November 13, 2015 21:01

November 10, 2015

The Garden of Voices: Poems About Veterans

Tomorrow, Veterans Day, is a holiday that began as a memorial to the millions who fought and sacrificed in World War I, called The Great War in its day, and then "The War to End All Wars," though of course it did not. The chosen date was Armistice Day, Nov. 11, because that was the date in 1918 when the armistice ending World War I was signed by the warring countries.

Since then we've had many more military veterans to recognize, and many more sacrifices, to acknowledge in the century that has followed that first Armistice Day.

We continue to recognize and honor veterans, as we should, even as we hope for no more wars. That's the note sounded by Firestone Feingold, the editor of the online literary journal Verse-Virtual, in his comment sent to the journal's contributors today:

"Well tomorrow is Veterans Day. Thank you to all who made it especially meaningful to me by contributing such dynamic and powerful poetry to this month's issue of Verse-Virtual. I wish everyone a good Veterans Day full of thanks to and remembrance of those who gave and yet give themselves to fight for us. May their kind of service no longer be needed by the peoples of the world — soon and forever."

Poems related to veterans is the optional theme for the journal's November issue (http://www.verse-virtual.com/). I picked out a few poems to mention here that I found especially effective.

Joseph Mills' poem "At the Veterans Hospital" blew me away. Responding to the idea that the world itself is only "virtual," a patient starts to cry. "...and when he places a hand on her new leg, she pushes it off, saying, This is not real. Her tone is hard to read, and he doesn’t know if she means the limb, the crying, the empathy, the room, the world."

This veteran's ambiguity, and one we have probably all felt, is beautifully expressed. The issue raised is beyond words, but this poem gives us some words to put the question. And I'm not sure what the answer is.

Mills's other poem "Service" is a slice of life report on a night "at the Legion." The poem concludes with an unassailable truth, both moving and blunt:

"We sit, surrounded by hungry veterans who served in Europe, the Pacific, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf. This is their reward for living when they did, going where they were told, and still being around. Cheap beer, piles of legs and breasts and wings, and family sitting across a table as wide as a battlefield."

Diana Rosen's poem "Father in his Swim Ensemble, Even Though He Doesn’t Swim" is full of rich detail, ironic as life. The poem tells us that the WWII veteran's gift for languages,

"(Yiddish segued to German) and a high school typing class kept him off the battlefield and inside the Captain’s office typing, filing, swallowing the bile that arose listening to 'those Jews, those Commies,' careless remarks made by the officer, oblivious to why they were both in the U.S. Army in Germany in 1943."

Rosen's poem "Old Age" offers a concretely observed, sympathetic but unsentimental recounting of the last routines of life for a man of "the man of a thousand Oys."

He falls asleep on a couch, wakes, nods off again, and the poem concludes with this metaphysical zinger:

"Slowly, he lifts his head awake, whispers, You think it’s easy to dream?"

Martin Willet's poem "How I Got To Vietnam" reports his experience as a medic in that tragic conflict, the simplicity and directness of the language lending weight to its powerful conclusion -- Should you read it here? (I don't know: is this a spoiler?):

After years of butchering on a farm,

seeing men lose hands to combines,

finding a deer shot

and dragging towards death,

it was not the blood or guts

or carrying trays with amputated arms or legs —

it was the cries for mommy

In her poem "Gulf War," Joyce Brown offers a succinct comment on the juxtaposition of news reporting and commerce that, for many of us, spoke to the heart the Gulf War. Here's an excerpt:

"We'll be back with more right after this:"

Chevrolet Caprice, Dodge Dynasty,

Dentu-foam and Chloraseptic Spray.

Pentagon officials praise

the "surgical strike...

But all that selling, and all that Pentagon PR, is not the whole story. The poem puts the event in focus with this last-line summation of the day's cost:

“and two pilots two pilots two pilots”

Poet Dick Allen's sums up the contradictions of the Vietnam Era in his poem "Veterans Day,"opening with the frank acknowledgment:

Once I hated you, your uniform, your name,

The way you hunched with buddies in an open truck.

You were the soldier shouting at the rain.

...and concluding with the enduring wider perspective that applies to so many of us:

Who can stop the rain?

We were young men in the days of Vietnam.

(Read the whole poems and many others on http://www.verse-virtual.com/current-...)

Published on November 10, 2015 21:02

November 9, 2015

That's Me All Over: An Interview Online

The literary journal 3288 Review published an interview with me online today.

The literary journal 3288 Review published an interview with me online today. The journal's editor, John Winkelman was generous with space and gave me a lot of scope to talk about "Suosso's Lane," my recently published "history/mystery" novel on the Sacco-Vanzetti case.

Here's an excerpt:

QUESTION: Can you give us some background on your novel? How and when did you decide to write a story based on Sacco and Vanzetti? Did it grow out of a general interest in that era, or did it grow from interest in the event itself?

ME: Timely question. Suosso’s Lane (https://www.web-e-books.com/index.php...), my story on the Plymouth, MA origins of the Sacco and Vanzetti case was, published recently as an ebook, with plans to eventually have it published in print.

The idea to write a story about the case developed from moving to Plymouth and then going to work or the community newspaper group that covered Plymouth and neighboring towns. I had learned about the case long ago, and continue to be mildly shocked that like other labor-oriented and progressive causes it has disappeared from common knowledge, had long lived in Massachusetts, but only after living in Plymouth for a few years did I learn that Bartolomeo Vanzetti was living in the town at the time of his arrest. Plymouth’s self-image is all about the 1620 Pilgrims, but the town, like much of the Northeast, became an industrial center after the Civil War, its factories luring immigrants from Europe. Vanzetti found his way to Plymouth in the early years of the 20th century and lived with an Italian family from his own region (the Piemonte) near a big factory in North Plymouth. The town takes no public notice of his existence or of the world-famous Sacco-Vanzetti affair. Because he was found guilty and executed? Because his anarchist views were wildly unpopular with Yankee Plymouth? In fact, the Massachusetts establishment hated everything about Sacco and Vanzetti – including their immigrant status – and aside from a flurry of interest during the Dukakis administration, no one has ever wanted to re-visit that century old judgment. And misjudgment.

An anniversary issue of the community paper I worked gave me the opportunity to research the local angle on Vanzetti’s story. A few years later a nonfiction anthology on 20th century Plymouth history enabled me to stretch that work into a magazine-length piece (“Trial of the Century: Local Amnesia”).

From conversations with my wife, Anne, I developed the idea of a ‘history mystery’ story centered on the efforts of a current day history teacher to dig up some lost piece of evidence that would establish Vanzetti’s innocence of the crime (a payroll robbery-murder) he was convicted of. But as I worked on the book, it became clear to me that I had to inhabit the person of Vanzetti and his circumstances more fully. There are scores of books about the case, examining the trial, the evidence, the legalities, but remarkably little on the record about Vanzetti the man, aside from the letters he wrote from prison. I do think that the issues of his time, a hundred years ago, have become our issues again. The exploitation of workers by a super-rich class – the robber barons of Gilded Age compared to today’s “One Percent”. The fear-borne prejudice against immigrants, or “others” – Southern and Eastern Europeans (Italians, Poles, Jews, etc.) were regarded as an inferior race. The use of the police, and secret police (“intelligence”), to protect the status quo. The FBI was invented to deal with Italian anarchists like Vanzetti and his “comrades.” Today the current head of the FBI tells us that criticism of the unjustified police killing of black men keeps police from doing their job.

So as I worked on Suosso’s Lane, the book came to feel increasingly relevant. One of its current-day characters is an African immigrant trying to keep from running afoul of the law. My Plymouth history teacher finds that one of his American Indian students is homeless, because of quarrels over a piece of property his family still owned. The real estate bubble of the early 21st century leads another of my contemporary characters to commit murder to protect a deal that will make him rich. (He’s unmasked by my nosy local reporter.) Do Americans care about anything today but money? The history teacher comes to feel that the demonization of the voices on the left – anarchists, socialists, populists – is one of the reasons that contemporary American society has lost its balance.

This is probably more than enough. But if anyone wants to hear more about me, the full interview is at http://www.3288review.com/2015/11/09/...

Published on November 09, 2015 21:19

That's Me All Over: Author Interview Online

The literary journal "3288 Review" published an interview with me online today.

http://www.3288review.com/2015/11/09/...

The journal's editor was generous space and gave me a lot of scope to talk about "Suosso's Lane."

Here's a sample:

QUESTION: Can you give us some background on your novel? How and when did you decide to write a story based on Sacco and Vanzetti? Did it grow out of a general interest in that era, or did it grow from interest in the event itself?

Robert Knox: Timely question. Suosso’s Lane (available here), my story on the Plymouth, MA origins of the Sacco and Vanzetti case was, published recently as an ebook, with plans to eventually have it published in print.

The idea to write a story about the case developed from moving to Plymouth and then going to work or the community newspaper group that covered Plymouth and neighboring towns. I had learned about the case long ago, and continue to be mildly shocked that like other labor-oriented and progressive causes it has disappeared from common knowledge, had long lived in Massachusetts, but only after living in Plymouth for a few years did I learn that Bartolomeo Vanzetti was living in the town at the time of his arrest. Plymouth’s self-image is all about the 1620 Pilgrims, but the town, like much of the Northeast, became an industrial center after the Civil War, its factories luring immigrants from Europe. Vanzetti found his way to Plymouth in the early years of the 20th century and lived with an Italian family from his own region (the Piemonte) near a big factory in North Plymouth. The town takes no public notice of his existence or of the world-famous Sacco-Vanzetti affair. Because he was found guilty and executed? Because his anarchist views were wildly unpopular with Yankee Plymouth? In fact, the Massachusetts establishment hated everything about Sacco and Vanzetti – including their immigrant status – and aside from a flurry of interest during the Dukakis administration, no one has ever wanted to re-visit that century old judgment. And misjudgment.

An anniversary issue of the community paper I worked gave me the opportunity to research the local angle on Vanzetti’s story. A few years later a nonfiction anthology on 20th century Plymouth history enabled me to stretch that work into a magazine-length piece (“Trial of the Century: Local Amnesia”).

From conversations with my wife, Anne, I developed the idea of a ‘history mystery’ story centered on the efforts of a current day history teacher to dig up some lost piece of evidence that would establish Vanzetti’s innocence of the crime (a payroll robbery-murder) he was convicted of. But as I worked on the book, it became clear to me that I had to inhabit the person of Vanzetti and his circumstances more fully. There are scores of books about the case, examining the trial, the evidence, the legalities, but remarkably little on the record about Vanzetti the man, aside from the letters he wrote from prison. I do think that the issues of his time, a hundred years ago, have become our issues again. The exploitation of workers by a super-rich class – the robber barons of Gilded Age compared to today’s “One Percent”. The fear-borne prejudice against immigrants, or “others” – Southern and Eastern Europeans (Italians, Poles, Jews, etc.) were regarded as an inferior race. The use of the police, and secret police (“intelligence”), to protect the status quo. The FBI was invented to deal with Italian anarchists like Vanzetti and his “comrades.” Today the current head of the FBI tells us that criticism of the unjustified police killing of black men keeps police from doing their job.

So as I worked on Suosso’s Lane, the book came to feel increasingly relevant. One of its current-day characters is an African immigrant trying to keep from running afoul of the law. My Plymouth history teacher finds that one of his American Indian students is homeless, because of quarrels over a piece of property his family still owned. The real estate bubble of the early 21st century leads another of my contemporary characters to commit murder to protect a deal that will make him rich. (He’s unmasked by my nosy local reporter.) Do Americans care about anything today but money? The history teacher comes to feel that the demonization of the voices on the left – anarchists, socialists, populists – is one of the reasons that contemporary American society has lost its balance.

Maybe a longer answer than you’re looking for. But the book’s been a pretty long journey for me.

[To see the entire interview, here's the link:

http://www.3288review.com/2015/11/09/...

http://www.3288review.com/2015/11/09/...

The journal's editor was generous space and gave me a lot of scope to talk about "Suosso's Lane."

Here's a sample:

QUESTION: Can you give us some background on your novel? How and when did you decide to write a story based on Sacco and Vanzetti? Did it grow out of a general interest in that era, or did it grow from interest in the event itself?

Robert Knox: Timely question. Suosso’s Lane (available here), my story on the Plymouth, MA origins of the Sacco and Vanzetti case was, published recently as an ebook, with plans to eventually have it published in print.

The idea to write a story about the case developed from moving to Plymouth and then going to work or the community newspaper group that covered Plymouth and neighboring towns. I had learned about the case long ago, and continue to be mildly shocked that like other labor-oriented and progressive causes it has disappeared from common knowledge, had long lived in Massachusetts, but only after living in Plymouth for a few years did I learn that Bartolomeo Vanzetti was living in the town at the time of his arrest. Plymouth’s self-image is all about the 1620 Pilgrims, but the town, like much of the Northeast, became an industrial center after the Civil War, its factories luring immigrants from Europe. Vanzetti found his way to Plymouth in the early years of the 20th century and lived with an Italian family from his own region (the Piemonte) near a big factory in North Plymouth. The town takes no public notice of his existence or of the world-famous Sacco-Vanzetti affair. Because he was found guilty and executed? Because his anarchist views were wildly unpopular with Yankee Plymouth? In fact, the Massachusetts establishment hated everything about Sacco and Vanzetti – including their immigrant status – and aside from a flurry of interest during the Dukakis administration, no one has ever wanted to re-visit that century old judgment. And misjudgment.

An anniversary issue of the community paper I worked gave me the opportunity to research the local angle on Vanzetti’s story. A few years later a nonfiction anthology on 20th century Plymouth history enabled me to stretch that work into a magazine-length piece (“Trial of the Century: Local Amnesia”).

From conversations with my wife, Anne, I developed the idea of a ‘history mystery’ story centered on the efforts of a current day history teacher to dig up some lost piece of evidence that would establish Vanzetti’s innocence of the crime (a payroll robbery-murder) he was convicted of. But as I worked on the book, it became clear to me that I had to inhabit the person of Vanzetti and his circumstances more fully. There are scores of books about the case, examining the trial, the evidence, the legalities, but remarkably little on the record about Vanzetti the man, aside from the letters he wrote from prison. I do think that the issues of his time, a hundred years ago, have become our issues again. The exploitation of workers by a super-rich class – the robber barons of Gilded Age compared to today’s “One Percent”. The fear-borne prejudice against immigrants, or “others” – Southern and Eastern Europeans (Italians, Poles, Jews, etc.) were regarded as an inferior race. The use of the police, and secret police (“intelligence”), to protect the status quo. The FBI was invented to deal with Italian anarchists like Vanzetti and his “comrades.” Today the current head of the FBI tells us that criticism of the unjustified police killing of black men keeps police from doing their job.

So as I worked on Suosso’s Lane, the book came to feel increasingly relevant. One of its current-day characters is an African immigrant trying to keep from running afoul of the law. My Plymouth history teacher finds that one of his American Indian students is homeless, because of quarrels over a piece of property his family still owned. The real estate bubble of the early 21st century leads another of my contemporary characters to commit murder to protect a deal that will make him rich. (He’s unmasked by my nosy local reporter.) Do Americans care about anything today but money? The history teacher comes to feel that the demonization of the voices on the left – anarchists, socialists, populists – is one of the reasons that contemporary American society has lost its balance.

Maybe a longer answer than you’re looking for. But the book’s been a pretty long journey for me.

[To see the entire interview, here's the link:

http://www.3288review.com/2015/11/09/...

Published on November 09, 2015 21:16

•

Tags:

anarchism, historical-fiction, plymouth, sacco-vanzetti

November 3, 2015

Into the Deep: Autumn's Garden in a Colorful Last Phase

It's November and the sun is going down. Not just setting earlier, but hanging lower in the sky all day, even at its noontime height. The decline of the sun in its apparent southward progression has come close to the halfway mark between the equipoise of the Sept. 22, the beginning of autumn, to its low point, the winter solstice on Dec. 22. So even on the mild, gloriously sunny fall days we're enjoying this week, the rays of the sun reach us as a much deeper (or more acute) angle than they do in summer.

The interesting thing to me -- and while it seems a charmingly aesthetic coincidence to me there is probably some deep geophysical reason for it -- is that these deeply slanted rays from the southward-descending sun serve to accentuate the colors of autumn. It's as if there's more red and gold -- a deeper color -- in the sun's light this time of year. Clearly we see more gold, and yellow, and orange and red in the earth's biological surface -- in our climate, the northern temperate zone -- in autumn than at any other time of year.

The dark full, mature, dark (maybe even a little oppressively) greens of late summer -- the quiet August greenwood, the September lawns that greet returning students on the first days of school -- have an air of calm, but slightly weary satisfaction. They have fought their battles, won their ground. There's nothing left to green up. Those late summer woodlands are low on bright colors, and almost slumberous in mood. Birds and other animals are feeding up for seasonal transformation to come, the stresses of migrations, or the deep retreats of winter, but they're eating quietly now.

The dark full, mature, dark (maybe even a little oppressively) greens of late summer -- the quiet August greenwood, the September lawns that greet returning students on the first days of school -- have an air of calm, but slightly weary satisfaction. They have fought their battles, won their ground. There's nothing left to green up. Those late summer woodlands are low on bright colors, and almost slumberous in mood. Birds and other animals are feeding up for seasonal transformation to come, the stresses of migrations, or the deep retreats of winter, but they're eating quietly now.

There's still plenty of green landscape on earth's surface even now, in the first footholds of November. Lawns are green, in some cases greener than have been for months because mid and late summer often stress grass, and in some cases they're spotted with the fallen leaves that, to my eye, give them more interest. The evergreens are ever as they were, though some are showing brown spots from the now-annual summer dry period (not technically a drought, but effectively one). But the deciduous tree have mostly turned. The perennials in our flower gardens have colored up, though their blossoms in almost all cases are long past. The primrose, a low scrubby, prolific plant that blooms yellow in June, turn their leaves crimson in October. The leaves of a knee-high flowering perennial called "balloon flowers" turn yellow as cheese. It's the early bloomers, first half the season, that seem to provide the most of this low fall foliage. Some of our late bloomers are still trying to bloom: a white-flowering anemone; some annuals; some mums. The Montauk daisy is interestingly caught in the middle. It's white, October-blooming flowers still hang on the stem, though they're drying and brown-spotting their petals. But the leaves, particularly on the low stems, are already turning yellow. And the beautiful, rusty, bronze and copper tones of weeping cherry tree hover over the back garden's center, like a temple to the color palette of autumn (second photo down). The lace-cap hydrangea in the front garden does something similar, offering a whole little forest's worth of variety in a shrub-sized canopy (last photo).

There's still plenty of green landscape on earth's surface even now, in the first footholds of November. Lawns are green, in some cases greener than have been for months because mid and late summer often stress grass, and in some cases they're spotted with the fallen leaves that, to my eye, give them more interest. The evergreens are ever as they were, though some are showing brown spots from the now-annual summer dry period (not technically a drought, but effectively one). But the deciduous tree have mostly turned. The perennials in our flower gardens have colored up, though their blossoms in almost all cases are long past. The primrose, a low scrubby, prolific plant that blooms yellow in June, turn their leaves crimson in October. The leaves of a knee-high flowering perennial called "balloon flowers" turn yellow as cheese. It's the early bloomers, first half the season, that seem to provide the most of this low fall foliage. Some of our late bloomers are still trying to bloom: a white-flowering anemone; some annuals; some mums. The Montauk daisy is interestingly caught in the middle. It's white, October-blooming flowers still hang on the stem, though they're drying and brown-spotting their petals. But the leaves, particularly on the low stems, are already turning yellow. And the beautiful, rusty, bronze and copper tones of weeping cherry tree hover over the back garden's center, like a temple to the color palette of autumn (second photo down). The lace-cap hydrangea in the front garden does something similar, offering a whole little forest's worth of variety in a shrub-sized canopy (last photo).

And, this week, the crown prince of autumn's color-creation, at least for intensity, is the Japanese maple, still a shrub, limited in size (having adjusted to itself to the amount of sun and water it gets from us, no longer pining for more), but not in the expression of its deep, dark, reddening heart (seen in both the top and third photo down). It's the declining sun that singes the foliage of these plants, firing them into autumn colors, as every day takes further into the deep.

And, this week, the crown prince of autumn's color-creation, at least for intensity, is the Japanese maple, still a shrub, limited in size (having adjusted to itself to the amount of sun and water it gets from us, no longer pining for more), but not in the expression of its deep, dark, reddening heart (seen in both the top and third photo down). It's the declining sun that singes the foliage of these plants, firing them into autumn colors, as every day takes further into the deep.

Published on November 03, 2015 20:14

November 1, 2015

Veterans-related Poems in November Verse-Virtual: The Garden of Remembrance

With Veterans Day on the horizon, Verse-Virtual editor Firestone Feingold gave poets the option of contributing poems pertaining to the veteran experience in the November issue of Verse-Virtual.com, the online poetry journal.

With Veterans Day on the horizon, Verse-Virtual editor Firestone Feingold gave poets the option of contributing poems pertaining to the veteran experience in the November issue of Verse-Virtual.com, the online poetry journal. Feingold's introductory notes highlight a poem contributed by Bill Glose, a veteran of the Iraq War. The poem, entitled "Soldiering On," deals with the epic challenge in 21st century combat experience (and maybe always) of what to do with that experience once you come back home. Glose's poem, written in sonnet form -- 14 lines, fixed meter and rhyme scheme -- doesn't slight the scope of the challenge, epitomized by a strong image when the poet wonders whether he can ever expect "the ice within my bones to melt anew."

But the poem comes to a hopeful conclusion in its final three lines:

Disarmed, I gulped blue air and felt alive.

Headlong at life I charged and wasn’t scared

to drop my shield and let my heart be bared.

In an introductory note Glose says he found release from that "ice" of bottled-up emotion by writing about his experiences. He states: "The first poems and essays seared like glowing skewers, but as I poured more of my heart onto the page a strange thing happened...I felt the catharsis of release. And so I kept going until I had a drawer full of them." (For the full story see http://www.verse-virtual.com/editors-...)

I'm not a veteran. My father (Alva J. Knox, 1921-2003) was and so were his three brothers, all serving during World War II, as did millions of other men and women of his generation. My connection to the veterans experience comes through him and my appreciation of the generation of Americans who struggled and sacrificed during a world war and succeeded not only in defeating the forces of hate but in making a better world both for themselves and for all of us who came after.

So my contribution to the veterans theme is a group of three poems, grouped under the title "Three Poems for My Father, And All The Rest."

Here's the first of those three poems:

A Row of Stones: Calverton National Cemetery

It looks like all the rest

slotted in this final postwar census, this straight-line campground of eternity,

a parking lot for identical souls

a computer punch card, names in the phonebook,

the roll call for hereafter,

the Levittown of the life to come

It looks, almost, like the line-up of all the local men,

stretching from here to God,

who once were young on any given day

Dress them in Army green

and lay them down in straight lines without number

on the battleground where future always conquers past

in an age we thought would never end

His gravestone looks... like all the others,

laid to rest exactingly in lines identical and perfectly straight,

the Army way, the regimental way of passage,

this permanent occupation of a grassy plain 'out East' on the island

where he planted his back-home, postwar fortunate flag

never to wander, really, plowing the highways on the city commute

never to leave the good ol' USA

and never, he said, to stand in line again

(I won't tell him if you don't)

They made it home, those who lie beneath these stones

facing straight ahead,

comrades to left and right, messmates, men of a generation

who did not fall in wintry France

nor plunge to doom from the infinite Pacific sky

but passed in cooler times,

doing their bit for the world that came after,

the world that they made safe for us

I number his grave goods, now the hour's long past,

bowling league trophies, pool hall cue

German rifle (Mauser, maybe) shot from the hands

of an enemy patrol in the Nice Triangle,

barkeep paraphernalia, little mixer sticks,

cut glass bowls for lemon twists

barbeque apron, cotton hat and silly stenciled T-shirt

"Who invited all these tacky people?"

paintbrush, hammer, handsaw,

pen and pencil, adding machine

Space, I wonder, in the final straight-line muster

for an old Dodge Dart, most enduring companion of the road,

the ashtray almost always full

http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-c...

Published on November 01, 2015 14:24

October 29, 2015

Autumn Looks: Fallen Leaves Make a Garden Everywhere

One of the best moments in autumn is when a big flotilla of leaves falls from some tall, handsome, colorful trees on your block, neighborhood, or especially right in front of your house, spreading their still vibrant colors all over your pavement.

Those leaves will dry out, and the color will fail until all the fallen leaves appear uniformly 'brown, old, dead' or any number of unattractive appellations. But that time is not today.

Those leaves will dry out, and the color will fail until all the fallen leaves appear uniformly 'brown, old, dead' or any number of unattractive appellations. But that time is not today.

When the leaves come down it's time to look at them. All over town they're creating compositions, textures, ephemeral works of color shape, patterns, and mixtures of all these elements on the canvas of earth's surfaces. Those surfaces in densely populated ares are generally hard, impervious. But for a week or two, they'll appeal to the senses.

When the leaves come down it's time to look at them. All over town they're creating compositions, textures, ephemeral works of color shape, patterns, and mixtures of all these elements on the canvas of earth's surfaces. Those surfaces in densely populated ares are generally hard, impervious. But for a week or two, they'll appeal to the senses.

Artists try to achieve some of the same effects in museums -- ephemeral, changing, disappearing -- with light machines, timers, filters, varieties of shadow and light, and natural materials that fade over time. But nature, the tilt of the earth, the apparent revolution of the sun spinning sine curves through the years, does it every year and all the time. Autumn is one its more stunning effects.

Artists try to achieve some of the same effects in museums -- ephemeral, changing, disappearing -- with light machines, timers, filters, varieties of shadow and light, and natural materials that fade over time. But nature, the tilt of the earth, the apparent revolution of the sun spinning sine curves through the years, does it every year and all the time. Autumn is one its more stunning effects.

The same effect, a stunning transformation of the look of surfaces, this sublime cultivation of appearances, is duplicated in the trees. And while many leaves are on the ground, still many more remain in the trees. It's a good time to look at them.

The same effect, a stunning transformation of the look of surfaces, this sublime cultivation of appearances, is duplicated in the trees. And while many leaves are on the ground, still many more remain in the trees. It's a good time to look at them. We won't have these color transformations to drink in much longer.

Published on October 29, 2015 22:00

October 23, 2015

My Novel on the Sacco-Vanzetti case, "Suosso's Lane," published!

Great news! It's like spring in October! My long-awaited (at least by me) novel on the Plymouth roots of the Sacco and Vanzetti case, titled "Suosso's Lane," has been published! The ebook edition of "Suosso's Lane" is now available online from the publisher, Web-e-Books. You can find it at www.web-e-books.com.

Great news! It's like spring in October! My long-awaited (at least by me) novel on the Plymouth roots of the Sacco and Vanzetti case, titled "Suosso's Lane," has been published! The ebook edition of "Suosso's Lane" is now available online from the publisher, Web-e-Books. You can find it at www.web-e-books.com.If you like to read books online, or are willing to give it a try, you can purchase it for $7.95. Print copies of the book are not ready yet. I'll have to produce them. I'm posting two releases from Web-e-Books below: The Media Release that describes the book (and, yes, offers a few words about the author's credentials). And the publisher's "easy purchasing instructions" on buying the ebook from its website, www.web-e-books.com

*** Media Release *** Suosso’s Lane , by American Novelist Robert Knox Released on Web-e-Books®The Innocence of an Executed Immigrant Sought at old Plymouth Home Quincy, Massachusetts, USA– Suosso’s Lane, fiction by American author Robert Knox, is being released on Web-e-Books® in support of world-wide, cross-platform distribution of his socially relevant novel on the inequitable treatment of early 20th-century immigrants. Based on the scandalously unjust trial and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti for a murder they did not commit, the international cause-celebre of the 1920s, Knox's novel follows the search for evidence of Vanzetti's innocence lost for decades to a government sanctioned frame-up.The Tri-Screen Connection, LLC, publisher and distributor of the exclusive e-book, is providing the technology platform and online shopping website for Suosso’s Lane.In the Story In Suosso’s Lane, journalist and creative writer Robert Knox revisits the history of Plymouth, Massachusetts, "America’s hometown," at a time when immigrant factory workers struggled to make their way in an America of long hours and low wages. The book traces the circumstances that led to the notorious trial and widely protested executions of Nicola Sacco and Plymouth dweller Bartolomeo Vanzetti, targeted by local authorities for their radical beliefs and framed for a factory payroll robbery and the shooting deaths of two security guards. A newly edited novel, Suosso’s Lane dials back the clock to revisit the flawed trial of Italian immigrant Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a believer in "the beautiful idea" of a classless society in which all would work for the common good. A sober-minded laborer, Vanzetti suffers from the exploitive treatment of industrial workers in the early decades of the twentieth century. Outraged by the greed and injustice that mar his idealistic hopes for the "New World," he joins other anarchists in promoting strikes and preaching revolution. In 1920, Vanzetti and his comrade Nicola Sacco are nabbed by police looking for radicals and subsequently convicted of committing a spectacular daylight robbery and murder. After seven years in prison, even as millions of workers and intellectuals around the world rally to their cause, the two men are executed. Seventy years later, when a young history teacher moves into Vanzetti’s old house in Plymouth, Massachusetts, he learns of a letter that might prove Vanzetti’s innocence. His attempt to uncover the truth is hindered by obstacles set by a local conspiracy theorist, the daughter of Vanzetti’s lover, a shady developer, and the eruption of a fire during his search of an old Plymouth factory.Web-e-Books ® AvailabilitySuosso’s Lane is viewable in licensed Web-e-Books® format available from The Tri-Screen Connection and is compatible with virtually all Internet browser-capable desktop, laptop, tablet, e-reader, mobile smart phone, or similarly equipped devices running Apple®, Windows®, Android®, and Linux operating systems.http://www.web-e-books.com/index.php#load?type=book&product=suossoPriced at US $7.95 – read on-line or offline, no download or installation required.About The Tri-Screen ConnectionThe Tri-Screen Connection represents a launch pad for broad adoption of new-media communications services, including digital content and publishing. Our publishing strategy is to satisfy the market for exclusive contemporary and select classic literature of excellence that provides reflective insight to a wide range of human experiences. Explore more at:

www.web-e-books.com

****

To purchase Suosso’s Lane on Web-e-Books.com, follow these steps:1. Open a web-browser on your PC, Mac, tablet, or smartphone.2. Enter www.web-e-books.com and find the e-book entitled Suosso’s Lane, by author Robert Knox.

or, enter the page link below to go directly to the title:

http://www.web-e-books.com/index.php#load?type=book&product=suosso

3. Click on “Add to Cart” at the bottom of the book description.

4. Click “Cart” at top of screen:

5. Click “Proceed to Checkout”6. Set-up new user account by entering user selected login name and password (write these down for your future reference), and provide e-mail address, then click “Save and Continue”7. Enter Billing Information, and Click Same to quickly populate Shipping information, then click “Save and Continue”8. Review Order Summary and Click “Save and Continue”9. Enter your credit card information, then Click “COMPLETE PURCHASE”10. An Order Summary (Receipt) will show next, and automatically be forwarded to the user account’s e-mail as entered in their account set-up. Click on the link provided in this Order Summary for access to the Suosso’s Lane e-book. It will look like this: http://suosso.web-e- books.com/

Sign-in with the login name and password entered in the account set-up process. Begin reading. (We suggest savingthe link above as a favorite in your browserfor quick futureaccess.Otherwise, login from the start page on www.web-e-books.com and click-on Read My Titles (a drop down), then click “read now” next to the title, Suosso’s Lane).

Published on October 23, 2015 08:30

October 22, 2015

The Garden of the Greats: Philip Larken

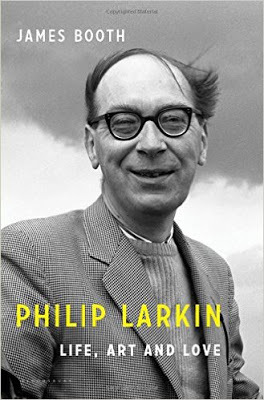

Autumn once more. I walk in the marshes, thinking of Philip Larkin. A superbly intense poetic practice that wrings a multi-leveled precision from every line, every word. A life's work of dense, virtuosic, deeply thought out, brief lyrics. A laser technique applied within an intentionally narrow range. His dates are 1922 to 1985, but don't look to his poems to find out what Larkin thought of World War II. Or the Cold War. On the evidence of his poems Philip Larkin did not think about the Cold War. Or about his exemption from military service in the early forties (poor vision) when the mere continued existence of his country was in doubt. If it ever bothered him, he didn't write about it.

Autumn once more. I walk in the marshes, thinking of Philip Larkin. A superbly intense poetic practice that wrings a multi-leveled precision from every line, every word. A life's work of dense, virtuosic, deeply thought out, brief lyrics. A laser technique applied within an intentionally narrow range. His dates are 1922 to 1985, but don't look to his poems to find out what Larkin thought of World War II. Or the Cold War. On the evidence of his poems Philip Larkin did not think about the Cold War. Or about his exemption from military service in the early forties (poor vision) when the mere continued existence of his country was in doubt. If it ever bothered him, he didn't write about it. His topics were the universals, or a particular set of them. According to biographer Jame Booth -- "Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love" (2014) -- he chose an artistic path while still a young: to live the common life and "write out of his own life." Not as a novelist, recreating a time and a place, telling an engaging story, but as a scientist of the heart, examining the heart and the psyche's deepest emotions. "The novel is about other people," Larkin wrote in a letter. "Poetry is about yourself." A poem is an emotion, he replied once when asked to provide his own definition,presented in as compact and compelling a way as can be done. I love this definition, though I know my own approach to poetry is nothing like it and I could not approach Larkin's standard if I tried. I'm not a perfectionist. I think Larkin was. Just as interesting is Booth's big-picture summary of his poetic career. Larkin had two major subjects, Booth writes, that divide his career neatly between younger and older periods. The younger Larkin's subject was marriage: why, that is, this well-worn two-by-two passage through adulthood remained for him the path not taken. He liked women; he wanted sex. He either chose for the reasons best expressed in some of his own 'younger' period poems to stay apart from the ordinary condition of breeding adults; or was simply incapable of entering it. I am inclined to think that Larkin concluded that only the more radical solitude of the unmarried state would enable him, or maybe force him, to write his best, most deeply felt work. (Though he never exalted the 'exceptional' state of the artist the way some of the aesthetes or a significant poet like Rilke, say, did.) The other explanation is that he suffered from some sense of a disqualifying, exiling wound. This is the poet, after all, famous for writing "They fuck you, your mum and dad. They may not mean to, but they do." As Booth's book shows, Larkin was particularly loyal to both his parents. The care and attention he showed his widowed mother through frequent visits and an endless string of chatty, attentive letters puts most other sons to shame, especially since being with Mum appears to have been more obligation than pleasure. It was an obligation he paid with good grace. His relationship to his father, a prince in the realm of accountants, not poets (and an admirer of Hitler), involved an eccentric sense of duplication. Larkin told people that he would die in his sixty-third year, because his father had. And then, astonishingly, he did die in the same year; and of the same disease. Hence, the single, obsessive theme of the second half of Larkin's poetic career: death. English poetry, it sometimes seems to me, is all about time. However good things are, we can't escape the final sorrow of our condition. However poorly things may be going, we always know they will end.

It's not a rationalist turn of mind to see life this way, at least in Larkin's case. It's a deeply emotional one. He's outraged that death is always in the rear-view mirror. The "early" poems included by editor Anthony Thwaite in "Philip Larkin: Collected Poems" exude a certain formal feeling, to borrow a phrase from Emily Dickinson, the betrayal of a young man with an anxious mind being hard on himself. In these poems he's a face in a crowd, but not part of it. He's the recording angel, or perhaps the surgeon, exposing its inner workings, the hard logic of human life. Later, when he comes into his own suffering, the distance from the crowd is not a pose, and his voice is wholly convincing, often indulging in a black humor funnier than Beckett. No bohemian, never a radical, rebel or outwardly nonconformist, Larkin seeks a profession after graduation and plays the game of life by the ordinary rules. A librarian, he rises in the profession, becomes the boss. He likes "the old England" in a time of change, but is forced to be part of the changes, overseeing the construction of a new library for a growing University in a backward province, Hull, famously described as "on the road to nowhere in particular." He liked it, Booth writes, for that reason. But he refuses the essential conventional commitment, marriage, and the daily invovlement with another human being it entals. He sought sex, but sex was difficult because it tended to draw you into intimacy, and then into commitment, and commitment drew you to marriage. A lifelong bachelor, he liked pornography. He was a hit with his friends' wives. He was a different 'Philip' to everyone who knew him, complaining about one friend to another. Courteous, respectful, hard-working, a good boss, middle-class. He rode his bicycle and visited old churches long after everyone else drove a car. When, after a biking accident, he learned how to drive, the loss of this form of regular exercise may have cost him his only way of keeping healthy. He liked to drink. On certain subjects, the subjects he put his stamp on -- the inevitability of disappointment, for example: nothing ever really lives up to our hopes and expectations, does it? -- it's hard for me to believe that anyone has ever written anything as good. For instance, "Next, Please":

It's not a rationalist turn of mind to see life this way, at least in Larkin's case. It's a deeply emotional one. He's outraged that death is always in the rear-view mirror. The "early" poems included by editor Anthony Thwaite in "Philip Larkin: Collected Poems" exude a certain formal feeling, to borrow a phrase from Emily Dickinson, the betrayal of a young man with an anxious mind being hard on himself. In these poems he's a face in a crowd, but not part of it. He's the recording angel, or perhaps the surgeon, exposing its inner workings, the hard logic of human life. Later, when he comes into his own suffering, the distance from the crowd is not a pose, and his voice is wholly convincing, often indulging in a black humor funnier than Beckett. No bohemian, never a radical, rebel or outwardly nonconformist, Larkin seeks a profession after graduation and plays the game of life by the ordinary rules. A librarian, he rises in the profession, becomes the boss. He likes "the old England" in a time of change, but is forced to be part of the changes, overseeing the construction of a new library for a growing University in a backward province, Hull, famously described as "on the road to nowhere in particular." He liked it, Booth writes, for that reason. But he refuses the essential conventional commitment, marriage, and the daily invovlement with another human being it entals. He sought sex, but sex was difficult because it tended to draw you into intimacy, and then into commitment, and commitment drew you to marriage. A lifelong bachelor, he liked pornography. He was a hit with his friends' wives. He was a different 'Philip' to everyone who knew him, complaining about one friend to another. Courteous, respectful, hard-working, a good boss, middle-class. He rode his bicycle and visited old churches long after everyone else drove a car. When, after a biking accident, he learned how to drive, the loss of this form of regular exercise may have cost him his only way of keeping healthy. He liked to drink. On certain subjects, the subjects he put his stamp on -- the inevitability of disappointment, for example: nothing ever really lives up to our hopes and expectations, does it? -- it's hard for me to believe that anyone has ever written anything as good. For instance, "Next, Please":Always too eager for the future, wePick up bad habits of expectancy. Something is always approaching; every dayTill then we say,

Watching from a bluff the tiny, clear,Sparkling armada of promises draw near.How slow they are! And how much time they waste, Refusing to make haste!

Yet still they leave us holding wretched stalksOf disappointment, for, though nothng balksEach big approach, leaning with brasswork prinked, Each rope distinct,

Flagged, and the figurehead with golden titsArching our way, it never anchors; it'sNo sooner present than it turns to past.Right to the last

We think each one will heave to and unload All good into our lives, all we are owedFor waiting so devoutly and so long.But we are wrong:

Only one ship is seeking us, a black-Sailed unfamiliar, towing at her backA huge and birdless silence. In her wakeNo waters breed or break. When still not thirty, he wrote the poem above and some others that define the existential questions of the human conditon, as Larkin saw it. On the necessity of 'forsaking all others' in the married state, he wrote the scathingly ironical (and hypothetical) "To My Wife," summing up in 14 matchless lines how a universe of choice sinks to a singularity. An excerpt:

Matchless Potential! but unlimitedOnly so long as I elected nothing...No future now. I and you now, alone.

So for your face I have exchanged all faces...Now you become my boredom and my failure,Another way of suffering...

Larkin's personal solution, as he said himself, was no solution at all. A boredom of solitude rather than with 'my wife'; alcohol, pornography, and a complex of relationships enduring long enough (and sometimes overlapping) that it's hard to call them affairs. Relationships, as we would say today. And he did produce the poems. The age-old, widely shared dissatisfaction with our human inability to appreciate the present (until it's past) shows up again in his rigorously honest poems. In "The March Past," a sudden, brief procession of music and flags takes the spectator out of himself, but when, as the poem says, the "music drooped" all that remained was

... a blindAstonishing remorse for things now eneded That of themselves were rich and splendid(But unsupported broke, and were not mended)...

And then, the final recourse, the choice of his life's true path, he addresses in "Best Society." ... Once moreUncontradicting solitudeSupports me on its giant palmAnd like a sea-anemoneOr simple snail, there cautiouslyUnfolds, emerges, what I am.

And what he is, at base, despite all the poems and all the days, and all the choices and all the regrets, is a being always looking over his shoulder for the approach of that "black-sailed" ship "towing at her back/ A huge and birdless silence."

Published on October 22, 2015 22:23