Robert Knox's Blog, page 42

April 12, 2016

The Garden of What We Know: Thin Grounds for Sacco's 'Guilt'

For thirty years anybody who knew anything about the Sacco and Vanzetti case contended that the two were innocent of the crime they were accused of and executed for -- the April 15, 1920 daylight robbery of a Braintree shoe factory payroll and the murder of two payroll officials. Then, in the anti-Communist Cold War fifties and sixties, the reaction set in. In fact, some theorists alleged, despite all that bleeding heart liberal sentiment to the contrary, the two Italian anarchists were actually guilty of these cold-blooded killings. Or, the more widely shared assertion, Sacco was guilty, though Vanzetti was not. Revisionist theories that appear to undermine settled, conventional views always win some converts. But after closely analyzing everything that Italian radical spokesman Carlo Tresca said or might have said about the Sacco-Vanzetti case over the course of 30 years, historian Nunzio Pernicone in his essay "Carlo Tresca and the Sacco-Vanzetti Case," published in "The Journal of American History," concluded that arguing for the guilt of Sacco on the basis of Tresca's unsubstantiated one-sentence remark in the early 1940s amounts to "a serious misuse of the historian's craft." Why is this important? Because the revisionist theory that Sacco and Vanzetti were not innocent after all, and were not the sort of peaceful "philosophical anarchists" many supporters made them out to be, has been based almost entirely on what Tresca reportedly said to the American one-time socialist Max Eastman. A 'half-point' must be granted here. Sacco and Vanzetti were not simply "theoretical" believers in the political, social and economic philosophy of anarchy, which calls for the abolition of the state, the church, and all forms of institutional authority. They believed in taking action as well. They supported strikes, but not labor unions, believing that workers (and everyone else) should be free to form voluntary cooperatives to support one another's subsistence. Further, anarchists who were part of the same Italian-speaking network as Sacco and Vanzetti mailed and planted bombs to government officials and major capitalists in the year preceding their arrest. In fact, the widespread belief of native-born Americans that these two Italian-speaking radicals were just the sort of people seeking to promote revolution by planting bombs is probably the reason a jury of white, English-speaking, native-born men so quickly convicted them of the Braintree crime on evidence that was far from convincing. Almost nobody today -- or at any time in the almost century-long reconsideration of the case -- defends the notion that Sacco and Vanzetti received a fair trial. Historian Paul Avrich sums it up this way: "The trial, occurring in the wake of the Red Scare, took place in an atmosphere of intense hostility towards the defendants. The district attorney conducted a highly unscrupulous prosecution, coaching and badgering witnesses, withholding exculpatory evidence from the defense, and perhaps even tampering with physical evidence. ... He played on the emotions of the jurors, arousing their deepest prejudices against the accused. ...The judge in the case likewise revealed his bias... He made remarks that bristled with animosity toward the defendants [including] "Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day?" When a verdict of guilty was returned, many believed that the men had been convicted because of their foreign birth and radical beliefs, not on solid evidence of criminal guilt." However, despite the trial's inadequacies, a number of voices in articles and books have maintained that one or both of the defendants were guilty -- as if the prosecution, despite lacking evidence pointing in their direction, had somehow stumbled on to the right men to charge with a heinous, high-profile, outrageous crime.... exactly the type of crime both the police and the public really like to see solved. Carlo Tresca, an Italian-American newspaper editor, orator, and labor organizer who played a prominent part in the Industrial Workers of the World, often served as the go-to guy for Italian radicals accused of crimes -- such as speaking out against American participation in World War I or the draft, actions that in 1917-18 constituted crimes. But although Tresca himself was Italian by birth and familiar with the Italian speakers who were members of the radical left, including anarchists, it does not follow that Tresca was intimate with members of these groups, knew their secrets, or held their trust. Anarchists who followed the teachings of theoretician and orator Luigi Galleani -- a network that included Sacco and Vanzetti -- may have sought Tresca's public support when needed, but they did not trust him or regard him as a true comrade. In fact Galleani's disdain for Tresca and his pro-union views was pronounced, and in the two decades that followed Galleani's deportation to Italy, his followers' attacks on Tresca and those whose ideology differed from the own grew increasingly bitter. After examining this history, Nunzio Pernicone concludes that believing that Carlo Tresca was likely to know some "inside story" about the crime at the origin of the Sacco-Vanzetti case amounts to a confession of ignorance of the anarchist and Italian left-wing movement. Tresca was at one time a member of the Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee "and frequently spoke in their defense at rallies [in New York City, where he was based] and in articles." At these rallies he declared without the slightest hesitation or doubt that Sacco and Vanzetti were entirely innocent of the crime they were charged with. This remained his position throughout the 7-year case and the following years. Pernicone then examines the theory of Francis Russell, and those who follow him that Sacco took part in the Braintree crime. Russell, who initially wrote an extensive study of the case back in the 50s, concluding at its end (along with almost everyone else who examined it) that Sacco and Vanzetti were not guilty. Russell then changed his mind, in an article and then an entire second book (ludicrously titled "Sacco and Vanzetti: The Case Resolved"), based largely on rumor and suspicion. The initial suspicion comes from a statement by Upton Sinclair, who researched the case for his novel about it, "Boston." After talking to the Brini family, with whom Vanzetti lived in Plymouth, and finding them wholly open to his intentions, he was surprised by the cool reception given him by Sacco's widow, Rosina Sacco, who was not eager to speak to him. Personally, I can think of dozens of reasons why Rosina, an Italian speaking woman with two children who suffered the trauma of losing her husband to a miscarriage of justice, would not wish to review her tragedy yet again with an American reporter. Frankly, she may not have known who Sinclair was. Nevertheless, Sinclair's impression that Sacco's widow had something to hide apparently drove him to other suspicions.

For thirty years anybody who knew anything about the Sacco and Vanzetti case contended that the two were innocent of the crime they were accused of and executed for -- the April 15, 1920 daylight robbery of a Braintree shoe factory payroll and the murder of two payroll officials. Then, in the anti-Communist Cold War fifties and sixties, the reaction set in. In fact, some theorists alleged, despite all that bleeding heart liberal sentiment to the contrary, the two Italian anarchists were actually guilty of these cold-blooded killings. Or, the more widely shared assertion, Sacco was guilty, though Vanzetti was not. Revisionist theories that appear to undermine settled, conventional views always win some converts. But after closely analyzing everything that Italian radical spokesman Carlo Tresca said or might have said about the Sacco-Vanzetti case over the course of 30 years, historian Nunzio Pernicone in his essay "Carlo Tresca and the Sacco-Vanzetti Case," published in "The Journal of American History," concluded that arguing for the guilt of Sacco on the basis of Tresca's unsubstantiated one-sentence remark in the early 1940s amounts to "a serious misuse of the historian's craft." Why is this important? Because the revisionist theory that Sacco and Vanzetti were not innocent after all, and were not the sort of peaceful "philosophical anarchists" many supporters made them out to be, has been based almost entirely on what Tresca reportedly said to the American one-time socialist Max Eastman. A 'half-point' must be granted here. Sacco and Vanzetti were not simply "theoretical" believers in the political, social and economic philosophy of anarchy, which calls for the abolition of the state, the church, and all forms of institutional authority. They believed in taking action as well. They supported strikes, but not labor unions, believing that workers (and everyone else) should be free to form voluntary cooperatives to support one another's subsistence. Further, anarchists who were part of the same Italian-speaking network as Sacco and Vanzetti mailed and planted bombs to government officials and major capitalists in the year preceding their arrest. In fact, the widespread belief of native-born Americans that these two Italian-speaking radicals were just the sort of people seeking to promote revolution by planting bombs is probably the reason a jury of white, English-speaking, native-born men so quickly convicted them of the Braintree crime on evidence that was far from convincing. Almost nobody today -- or at any time in the almost century-long reconsideration of the case -- defends the notion that Sacco and Vanzetti received a fair trial. Historian Paul Avrich sums it up this way: "The trial, occurring in the wake of the Red Scare, took place in an atmosphere of intense hostility towards the defendants. The district attorney conducted a highly unscrupulous prosecution, coaching and badgering witnesses, withholding exculpatory evidence from the defense, and perhaps even tampering with physical evidence. ... He played on the emotions of the jurors, arousing their deepest prejudices against the accused. ...The judge in the case likewise revealed his bias... He made remarks that bristled with animosity toward the defendants [including] "Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day?" When a verdict of guilty was returned, many believed that the men had been convicted because of their foreign birth and radical beliefs, not on solid evidence of criminal guilt." However, despite the trial's inadequacies, a number of voices in articles and books have maintained that one or both of the defendants were guilty -- as if the prosecution, despite lacking evidence pointing in their direction, had somehow stumbled on to the right men to charge with a heinous, high-profile, outrageous crime.... exactly the type of crime both the police and the public really like to see solved. Carlo Tresca, an Italian-American newspaper editor, orator, and labor organizer who played a prominent part in the Industrial Workers of the World, often served as the go-to guy for Italian radicals accused of crimes -- such as speaking out against American participation in World War I or the draft, actions that in 1917-18 constituted crimes. But although Tresca himself was Italian by birth and familiar with the Italian speakers who were members of the radical left, including anarchists, it does not follow that Tresca was intimate with members of these groups, knew their secrets, or held their trust. Anarchists who followed the teachings of theoretician and orator Luigi Galleani -- a network that included Sacco and Vanzetti -- may have sought Tresca's public support when needed, but they did not trust him or regard him as a true comrade. In fact Galleani's disdain for Tresca and his pro-union views was pronounced, and in the two decades that followed Galleani's deportation to Italy, his followers' attacks on Tresca and those whose ideology differed from the own grew increasingly bitter. After examining this history, Nunzio Pernicone concludes that believing that Carlo Tresca was likely to know some "inside story" about the crime at the origin of the Sacco-Vanzetti case amounts to a confession of ignorance of the anarchist and Italian left-wing movement. Tresca was at one time a member of the Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee "and frequently spoke in their defense at rallies [in New York City, where he was based] and in articles." At these rallies he declared without the slightest hesitation or doubt that Sacco and Vanzetti were entirely innocent of the crime they were charged with. This remained his position throughout the 7-year case and the following years. Pernicone then examines the theory of Francis Russell, and those who follow him that Sacco took part in the Braintree crime. Russell, who initially wrote an extensive study of the case back in the 50s, concluding at its end (along with almost everyone else who examined it) that Sacco and Vanzetti were not guilty. Russell then changed his mind, in an article and then an entire second book (ludicrously titled "Sacco and Vanzetti: The Case Resolved"), based largely on rumor and suspicion. The initial suspicion comes from a statement by Upton Sinclair, who researched the case for his novel about it, "Boston." After talking to the Brini family, with whom Vanzetti lived in Plymouth, and finding them wholly open to his intentions, he was surprised by the cool reception given him by Sacco's widow, Rosina Sacco, who was not eager to speak to him. Personally, I can think of dozens of reasons why Rosina, an Italian speaking woman with two children who suffered the trauma of losing her husband to a miscarriage of justice, would not wish to review her tragedy yet again with an American reporter. Frankly, she may not have known who Sinclair was. Nevertheless, Sinclair's impression that Sacco's widow had something to hide apparently drove him to other suspicions. The single publicly stated claim that Sacco was guilty of the Braintree crime comes from Max Eastman's report that Tresca told him, "Sacco was guilty, Vanzetti innocent." Eastman was a radical in the early decades of the 20th century who moved to the right during the Stalinist period. Like other socialists, he was dismayed by what the USSR had turned socialism into. After analyzing how little Tresca actually said to Eastman, Pernicone concludes that Russell "greatly exaggerated and misunderstood" Tresca's importance to Italian anarchists, assuming incorrectly that Tresca became the godfather of the Italian anarchist movement after Galleani's deportation. Given Galleani's "condescension and disapproval" of Tresca, Pernicone state, it is "unthinkable" that his followers would choose Tresca for a leader after Galleani's removal. Again, after analyzing the attitudes of anarchists toward stealing money for revolutionary purposes, Pernicone concludes that anarchists were loathe to commit acts that could not be distinguished from those of ordinary criminality. Pernicone writes that it is "inconceivable that Tresca would have inside knowledge" of an anarchist plot to rob a factory payroll for money. Examining the reliability of Tresca's claim of Sacco's guilt, Pernicone states that Tresca's close associate and partner in publishing ventures Luiggi Quintiliano asserted that Tresca did not believe that Sacco was guilty during the case or the immediate years after. Quintiliano himself visited Sacco in prison, who told him bluntly, "Continue to assert our complete innocence."

But somewhere in the years to follow, Pernicone concludes, Tresca told at least two people something different. His own focus had changed from defending radicals to combating Italian fascists in America for leadership of the Italian community. In fact Tresca's murder in1943 is sometimes attributed to his fascist enemies. Why would Tresca, who had widely asserted Sacco and Vanzetti's were innocent in the 20s and thirties, change his view and tell Eastman that Sacco was guilty? Since no new "first-hand information" was available, and no evidence came to light to explain his change of mind, Pernicone attributes the change in his view to the impact of the deep personal attacks on him by the anarchists of the Galleani faction. Slandering one of theirs, that is, was a way of getting back at them. And, finally, Pernicone offers this assessment of Tresca's personality: "He had a great need to be in the spotlight."

[Here's the link for Pernicone's article: http://www.umass.edu/legal/Benavides/...]

Published on April 12, 2016 20:51

April 10, 2016

The Garden of Theater: For Tom Stoppard 'Arcadia' is Close to Perfect

In the play "Arcadia," written in 1993 by the cleverest, if not simply the best of contemporary playwrights, Tom Stoppard has his characters more than once mouth a famous classical tag: "Et in Arcadia ego..." A phrase translated, by general consent, as "Even in Arcadia I," which sounds harmless enough. In a play so full of allusions to both the world of mathematics and science, as well as to literature (and for that matter to landscape gardening), it's hard to fasten on any one such reference as containing the work's ultimate meaning. But this one stopped me, because my background is literature, rather than science or math. And even in the world of literature, while I'm not terribly fond of the principal figure Stoppard's contemporary characters are fighting over -- Lord Byron -- I'm troubled that I can't quite recall the point of this classical allusion. I knew it was Virgil, but my high school Latin sequence stopped before we got to Virgil (after our teacher, hopeless at controlling a classroom, was fired for coaching some students through the Regents exam), and so may familiarity with the great poet of the Roman world is patchy at best. I'll come back to this point -- "Arcadia" is after all the name of the play -- but first, if you have never seen this play, you have a chance to do through May 1 at the Central Square Theater in Cambridge, MA. And I would strongly recommend it. It's an intellectual mystery, or series of interlocking riddles, set both in early 19th century and the contemporary day. Let me draw on the program notes by director Lee Mikeska Gardner, to sketch a few of the play's rich and complex outlines. Arcadia is "the grandmother of what we call Science Plays, weaving human foibles and passions between the lines of math and science and philosophy, not to mention literature and art," Gardner tells us. In short, almost everything that matters. If you can follow the explanation provided by one of the play's genius characters (there's a pack of them) of the importance of "iterated algorithms," so much the better. If not, it's good to bring along a PhD in mathematics, as my wife and I were fortunate to do Saturday night, to explain it during intermission. The play posits that another of the play's 19th century geniuses (a barely adolescent girl) intuits this possibility, but can't work out a "proof" since progress in this direction required the invention (as a 20th century math whiz tells us) of the electric calculator. All right, so much for the Newtonian universe, the law of irreversible heat loss, and the consequent likelihood of entropy (the end of everything) in a closed system universe. (For further elucidation of these points your Google is as good,or better, than mine.) But, as Gardner happily points out, there is so more to contemplate. For instance, tutor Septimus Hodge -- near enough to genius to appreciate his young charge's mathematical insights -- astonishingly moving justification of the March of Time. Weep not over the burning of the Alexandrian library, and the subsequent loss of scores of Greek tragedies, and who knows how much Aristotle, he tells the girl (and us) because what we have lost is bound to come back in some other form. Instead, cherish what we have. What we don't have -- to plunge us into the contemporary story, set in the same old English estate where our 19th century figures quarrel over adultery, poetry, landscape architecture (and, on occasion, Newton's deterministic universe) -- is any proof that George Gordon Lord Byron ever visited this great old English estate and there fought a duel, killing a minor English poet after tupping his wife. We do have a contemporary scholar who is studying the plans to alter an already Romantic English Garden to bring it line with currently fashionable (and even more bizarre) notions, such as building a "hermitage" along with spotting the landscape with various ersatz "ruins." This female scholar ultimate confesses that she hates the whole "wild, Romantic garden" movement that, as she sees it, destroyed the more natural harmony of the Enlightenment plan for a balanced, reasonable "natural" landscape better suited to contemplating the golden mean. These two opposing present-day scholars, both mining the same period for discoveries to make their name -- the spokesman for the Byronic notion of poetic genius, and the spokesman for "reason" and balance (and for the women seduced and abandoned by Byron) -- battle things out in brilliantly comic fashion. Nobody has more words than Stoppard. And he doesn't spare any of them in this multi-layered, intellectually challenging (and engaging) feast of language, ideas, human types, and their typical foibles. So why is the play called "Arcadia"? Arcadia, I find, is an actual piece of terrestrial geography "celebrated as an unspoiled, harmonious wilderness." Virgil writes of it, at least glancingly, in one of his major works know as the "Eclogues." Since everything in Roman culture goes back to the Greeks, "eclogue" refers to the Greek word for a perfect rustic place. And Arcadia, the epitome of all such places, is actually a region in the Greek Peloponnese. (More on this some other time.) So possibly "Arcadia" would be your naturally beautiful landscape if nobody had 'artistic' or 'cultural' designs to improve it with fashionable alterations (think McMansions). Ah, but the phrase "Et in Arcadia ego..." as it appears in Virgil's eclogue is written on the funeral monument to the shepherd Daphnis, who is himself the perfect human epitome of this perfectly harmonious natural place. These words appear to be a eulogy to an admirable figure lost too soon. And because they are written on a tombstone, it us supposed that the "ego" ("I") stands for death (though the word 'death' does not appear in the poem). Remember, these words warn (in the interpretation given them by later ages), that even in the most perfect and beautiful of places, death still rules our fate. This phrase can be applied in so many ways to the Stoppard's play that the head spins. If the deterministic Newtonian universe, plus the law of irreversible heat loss, means that everything in the universe will run down in the end... then death is everybody's fate. It's the answer to all the play's questions. Human progress? Byron? The design of your garden? What they all mean in the end is not very much. And yet, though as I confessed in the beginning I am no Virgil scholar, I do know that Virgil's great works celebrate Rome. The "Aeneid" celebrates Rome's birth from the ashes of fallen Troy. The Eclogues themselves, I understand, move to a prediction of a golden age of empire ushered in by Octavius (favored by Jove) who rules as the emperor Caesar Augustus. Yes, "even in Arcadia." But the meaning may be that since we can all foresee our end of days, isn't it time for us to be getting on with things that matter?

Published on April 10, 2016 22:02

April 7, 2016

The Garden of Verse: Poems That Speak Their Name

The "optional theme" for the April edition of Verse-Virtual is 'poetry.' Not all of these poems set out to address that theme, but they all get there, if only by being themselves.

The "optional theme" for the April edition of Verse-Virtual is 'poetry.' Not all of these poems set out to address that theme, but they all get there, if only by being themselves. I don't remember which Eastern European country the eminent poet Charles Simic is from, but Kate Sontag's poem "National Poetry Month with Charles Simic" captures the mood of disquieting difference readers notice in his verse, an unsettling quality this poem neatly pinpoints as "news from some other universe." Simic's disturbing "childhood accent" turns our own native tongue "mundane as cornfields," Sontag writes. Her poem's final, beautifully stitched together stanza captures the paradox of chilling truths we need to hear in the lines:"I could almost kiss each of your books for/ containing such sustaining nightmares".

Lenny DellaRocca's poem "Somewhere Downhill" reads like a prophecy to me, the sort where the tricksy prophets give you some words but leave plenty of room for interpretation. And I do like the words here, such as these lines giving shape to some ephemeral crossing of destinies: "I will be a father in these hills.

Her black eyes will keep me in her years."

I also like DellaRocca's poem "A Distance of Summer," which captures some part of the true Long Island experience: "The distance between us

filled with towns." As someone who grew up in that flat land, I know you can find distances between point X and point Y wholly lacking in forests, lakes, or mountains. But you will never find a distance without towns.

I admired Robert Wexelblatt's "Today's Poem" because it seems to me that most days could be the "today" of this poem. Contributing to the issue's theme of the nature of 'poetry,' the verse posits a poet who strolls through a garden pretending to be Japanese. He wishes to see the peonies as the classical poet Basho would or to say something "unexpected" about the appearance of Fujiyama rising over the horizon. That sudden mountain, I suggest, is the "suchness" of existence. Even poets run out of ways to evoke wonder and the miraculous, but we still need to take a good look. Wonder is all around us in so many of these April poems that tell us about 'poetry' while also telling us about something else. W.W. Lantry shows us "Strawberries," particularly in these lines where the verbs roll off the tongue, suggesting the way strawberry plants grow and spread in the spring: "...but in their fields sprawlacross the mounds of earth, where tendrils spin,stretch, clutch, until they root and start to swell." Strawberry plants are alive in the spring. We hope our poems are too. Sometimes poetry is the temple of pure invention. Sonia Greenfield's "Celebrity Stalking" is a witty role reversal that sends screen stars stalking poets to "ask about pentameter," as the poem puts it, or solicit "sexstinas (sic)". Similarly inventive, her poem "Ode on a Floppy Disc" leaves us with a perfectly horrifying apocalyptic image at the end of this "ode" to all the poems that do not exist -- for example, "The poem,

maybe the loveliest written,

too arresting to speak."-- by asking us to contemplate "That poem about the house

fire, cracking its hot whip

against the hard-drive,

literally taking it all.” Please, anything but that.

And in a poem tellingly titled "I Shouldn't Even Write This," maybe some part of this creation's invention is up to us. We know there's something we're not being told, but we feel its fire ("that rage/

those words are mine") nevertheless.

Firestone Feinberg's "Poetry's Fork" is a solid stab at the issue's optional theme, landing a direct hit at its target, as the poem's language illustrates its sense: "When you hear rhymes, especially in metered lines,

they distract you like chimes,"

Leading us to a conclusion, both allusive and concise, that suggests some fair-minded judge's decision: "So the matter is.

Divergent roads never merge.

Walk another way."

David Chorlton's "Poetry in a Political Year" suggests that poetry is a lonely voice of eloquence, sweet reason and style lost in the hard-sell clamor for attention in a time of wall-to-wall campaign rhetoric. He writes: "The Electoral College doesn’t pay attention

to line breaks and even when Lincoln

was elected didn’t recite

anything that rhymed." Caught up in the current atmosphere, I might have said the electoral college has no standards, sets an absurdly low bar for admission, and accepts members utterly lacking in qualifications: Throw the bums out! How much more poetic to bring up Lincoln and point out the absence of rhyme.

Laura Kaminiski's "night iris" illustrates the theme of "Patience" by describing a vigil spent watching each bud of a paintbrush iris unfold, waiting for every last petal: "to loosen slightly,

take a deeper drink

stretch as if it is

a new-formed

wing, then swing

free of its still-tucked-in

kin. and then the next."

We might say nature is a kind of poetry too.

Published on April 07, 2016 20:27

April 5, 2016

The Garden of History: The Still Homeless Memorial for Sacco and Vanzetti

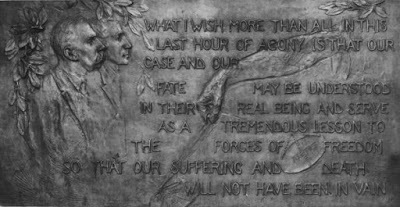

In 1928 Gutzon Borglum took time out from turning the face of a South Dakota mountain into the Mount Rushmore National Memorial, bearing the faces of great American leaders, to create a 7-foot long low-relief sculpture depicting two famous faces of contemporary America, Sacco and Vanzetti, along with a quotation from Vanzetti's last words. The famous sculptor intended to give this work to the City of Boston for public display.

In 1928 Gutzon Borglum took time out from turning the face of a South Dakota mountain into the Mount Rushmore National Memorial, bearing the faces of great American leaders, to create a 7-foot long low-relief sculpture depicting two famous faces of contemporary America, Sacco and Vanzetti, along with a quotation from Vanzetti's last words. The famous sculptor intended to give this work to the City of Boston for public display. The site of the two Italian immigrants' execution just the year before (Aug. 23, 1927), Boston was in no mood to accept such a gift in 1928. Attempts were then made to present the sculpture to city officials in 1937, 1947 and 1957 to Boston mayors or a Massachusetts governor without success.

On the 20th anniversary of the executions (1947), some famous names -- try Eleanor Roosevelt and Albert Einstein -- wrote a public statement demanding that the state publicly display the Borglum sculpture. But no one tells the state of Massachusetts that 'you were wrong in 1927 and you are still wrong today.' The demand was ignored.

In 1977 Governor Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation that cleared the names of Sacco and Vanzetti from guilt on the ground that they had not received a fair trial.

In 1997, 70 years after the executions, the gift of the sculpture was officially accepted by Mayor Thomas Menino and Governor Paul Cellucci. The sculpture depicts the two men's faces in profile along with a quotation from Vanzetti's last letter. Although Borglum had cast the work in bronze, the bronze had disappeared, and only a plaster cast of the work remained. Plans were made then to cast the sculpture in bronze and display it in a suitable public space.

Somehow, nothing happened, and Borglum's sculpture remains behind doors in a back room of the Boston Public Library.

In 2014, the Boston Globe's Richard Kreitner wrote a story pointing out that despite occasional gestures "the Boston area has done its best to forget the whole affair." His story points out that the execution site, the old Charlestown state prison, is now the Bunker Hill Community College. The old Norfolk County Jail in Dedham, where both men were imprisoned at times, has been converted into luxury condominiums.

And, most bizarrely of all, Borglum's sculpted memorial of two victims of societal prejudice has been stashed "on the third floor of the Boston Public Library, down a series of corridors and through several rooms, behind a door that, one out-of-town visitor was recently saddened and surprised to find, is locked on weekends." A Boston organization called the Sacco-Vanzetti Memorial Committee (http://saccoandvanzetti.org/) continues to push for "daylighting" the sculpture in some public outdoor setting. A committee member, Robert D'Attilio, said that a recent offer of a home for the sculpture came from the town of Dedham.

Boston, where the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee headquartered a seven-year effort to raise funds for the defense in the lengthy case, and where an estimated 200,000 people took part in a funeral march for the executed men, still seems to me to be right and proper home for a public memorial for Sacco and Vanzetti.

Published on April 05, 2016 21:03

April 3, 2016

National Poetry Month: The Garden of Helpful Advisories

It may not be dinner table talk in most of America, but the poetry community gets its knickers in a twist this time of year over the official designation of April as Poetry Month. April is no doubt officially other things too, such as "Back to the Backyard Garden Month" (depending on your latitude), but now that the digital world connects all lives, those who write poetry feel not only encouraged, but positively peer-pressured to step up their game when April rolls around. The drumbeat begins in March, with exclamatory announcements such as "It’s not too late to make a plan for poetry month!" from Poets.org. (I never realized that poets are such planners.) This advisory continues:

It may not be dinner table talk in most of America, but the poetry community gets its knickers in a twist this time of year over the official designation of April as Poetry Month. April is no doubt officially other things too, such as "Back to the Backyard Garden Month" (depending on your latitude), but now that the digital world connects all lives, those who write poetry feel not only encouraged, but positively peer-pressured to step up their game when April rolls around. The drumbeat begins in March, with exclamatory announcements such as "It’s not too late to make a plan for poetry month!" from Poets.org. (I never realized that poets are such planners.) This advisory continues:"Whether you want to sign up to write a poem a day or unofficially just plan to crank out some poetry in April, there are plenty of prompts and resources to keep you going strong all month. And that’s not all that’s going on either....

“National Poetry Month is the largest literary celebration in the world, with tens of millions of readers, students, K-12 teachers, librarians, booksellers, literary events curators, publishers, bloggers, and, of course, poets marking poetry’s important place in our culture and our lives.”

Among the many things you can do in April is find daily stimulus by checking into the "prompts" offered by seemingly countless sources. A "prompt" says either 'write a poem about such-and-such' or 'write a poem in such-a-such a way, or from such and such a source, or inspiration,' some of them completely and wholly random.

New to the online poetry world, it took me up to last year to learn that almost everybody (at least occasionally) was working from prompts. Just a couple of examples. Here's a prompt from a mainstream publication WRITERS DIGEST, which (like so many other sources) promises to give you a new one every day for the 30 days of officially poetic April:

"4/1. For today’s prompt, write a foolish poem. It’s April Fool’s Day, after all. Let’s loosen up today with a poem in which we’re fools, others are fools, or there’s some kind of prank or tomfoolery happening. Fool around with it a while."

And here, a different sort of approach to the prompt,is the offering from the high official body for National Poetry Month, http://www.napowrimo.net/ . The first day's instruction was:

"Today, I challenge you to write a lune. This is a sort of English-language haiku. While the haiku is a three-line poem with a 5-7-5 syllable count, the lune is a three-line poem with a 5-3-5 syllable count. There’s also a variant based on word-count, instead of syllable count, where the poem still has three lines, but the first line has five words, the second line has three words, and the third line has five words again. Either kind will do, and you can write a one-lune poem, or write a poem consisting of multiple stanzas of lunes. Happy writing!" They're starting us out with an easy one here. Haikus, for example, are popular because it is not difficult to find enough English words to produce three lines with a 5-7-5 syllable count, e.g.: The challenge lies less in counting nature's wonders than ready fingers

So a 5-3-5 "lune" is a relatively quick launch. Working a poem "with multiple stanzas" proves more of a challenge. I began with: Visiting roses

You always

Give a little blood

I'm still not satisfied with my progress through the next four stanzas, especially as I bent the rules by, on occasion, continuing the syntax of my line-three offerings into the following stanza. So I'll call this a work-in-progress, yet another "form" of poetry practitioners are all too familiar with.

When I looked for April 2 prompts I was offered "write a he-said, she-said poem" -- nah, too likely to fall into stereotypes (though, I suppose, if you made it really funny...) -- or "write a family portrait" working from an actual family photograph. Again, this seemed like something that's done all the time. So, I tried a family portrait that compares each family member to some kind of plant or plants. A family garden? Once again, I'm not ready to share the results.

This brings us to April 3, when, wakened at 6 a.m. by the rather substantial rattle of over-sized snow "flakes" on the window panes, not a sound I'm eager to hear when my hyacinths are blooming and the cherry tree is pushing out its white buds... I am suddenly sent back to the previously encountered (and rejected) prompt for April 1. Since it's April Fools Day (the source suggested), write a poem about fools or foolishness. Foolish weather! = Foolish me! Here's the result:

The Foolish Month

And the snow came downlike laughing madness,some kind of jokeworked up by the season, this heavy-handed season,too warm to snow (seventies last week)yet here it is, in April,foolish April,the month for fools

Snow falls upon the new green growth,sodding green leaves up like sopping paper bags, twists of litter blown from trash day, like remaindersof a life that one could sleep through,and usually did,but lately can not

April, foolish April,taking handfuls of the sky,wadding them up like cotton balls, making a light-show behind the blindered window,an electrical storm of shiny, furry particles,white goat's hair torn from a cotton plant,laundry fuzz,shooting your ammunition sideways, laser-like, the wind driven foolishby a foolish month

Once I slept these sparkled hoursNow they root in my foolish mind

[Some links, for those who are interested, or dare:] http://www.napowrimo.net/

https://www.facebook.com/30dpc/timeli...

http://trishhopkinson.com/2016/03/29/...

http://www.foundpoetryreview.com/blog...

Published on April 03, 2016 09:45

March 31, 2016

First Days of Spring: Promises of Emergence on the Eve of Folly

Let's start somewhere. Crocuses are winter flowers. We want to see them in early sick-of-winter March, if not February. You don't see them if the snow cover is heavy. If it's light, or just a dusting, they pop right up through it. We had one of those semi-serious March snows a few weeks ago. It was melting away by sundown on the same day it fell. The next day one final crocus emerged, so I took its photo and put it here.

I have no name for these little blue guys who pop up in the last days of March amid last year's uncleared brown leaves and the green vines of the vinca. I simply call them star flowers. (second photo).

I have no name for these little blue guys who pop up in the last days of March amid last year's uncleared brown leaves and the green vines of the vinca. I simply call them star flowers. (second photo).

These pink-tinted Lenten roses, so named obviously because that's the time of year they start new growth and show their color, are also known as examples of hellebores (third and fourth photos down). If Lent starts in February, in most climes you'll these blossoms then.

These pink-tinted Lenten roses, so named obviously because that's the time of year they start new growth and show their color, are also known as examples of hellebores (third and fourth photos down). If Lent starts in February, in most climes you'll these blossoms then.

Hyacinths (below) are one of my favorite bulbs. They make a good show and they'll bloom reliably for years, even without any special attention. The flowers of the vinca minor (right) love the first sunny days of March. They're not put off by a lot of dead leaves, broken stems, fallen branches twigs, acorns, the predations of squirrels. In some woodland areas they'll carpet the forest floor, thick as a medieval tapestry with an elaborate pattern. They're an allegory for growth, persistence, annual renewal. A daffodil or two arrives in the herb garden, stealing a march on the edibles. I don't remember putting it there. Someone should interview the squirrels.

Hyacinths (below) are one of my favorite bulbs. They make a good show and they'll bloom reliably for years, even without any special attention. The flowers of the vinca minor (right) love the first sunny days of March. They're not put off by a lot of dead leaves, broken stems, fallen branches twigs, acorns, the predations of squirrels. In some woodland areas they'll carpet the forest floor, thick as a medieval tapestry with an elaborate pattern. They're an allegory for growth, persistence, annual renewal. A daffodil or two arrives in the herb garden, stealing a march on the edibles. I don't remember putting it there. Someone should interview the squirrels.

Three prominent perennials in the next photo. Lower left is the speedwell. Center, closer to the bricks is one of the varieties of Campanula (little bells) I've planted in recent years. This one shows up for business every year. To its right the purple-leafed coral bells, which fare so well in partial sun. The definition of this back garden is partial sun.

Three prominent perennials in the next photo. Lower left is the speedwell. Center, closer to the bricks is one of the varieties of Campanula (little bells) I've planted in recent years. This one shows up for business every year. To its right the purple-leafed coral bells, which fare so well in partial sun. The definition of this back garden is partial sun.

A couple of primroses, one with red blossom opening. Can't remember if this variety is the so-called English or so-called Japanese primrose. It's probably fighting for space, water and nutrients from a crowd of neighbors all of which will ultimately o'ertop it. But in April it will win the local beauty contest.

A couple of primroses, one with red blossom opening. Can't remember if this variety is the so-called English or so-called Japanese primrose. It's probably fighting for space, water and nutrients from a crowd of neighbors all of which will ultimately o'ertop it. But in April it will win the local beauty contest.

The columbine. Again, an early bloomer. I'm happy to see its leaves looking so vibrant. I'll try to remember to cut down everything around it for a month or two to give this plant enough light to shine in early May when its wild-woodsy blossoms show and grow.

The columbine. Again, an early bloomer. I'm happy to see its leaves looking so vibrant. I'll try to remember to cut down everything around it for a month or two to give this plant enough light to shine in early May when its wild-woodsy blossoms show and grow.

Published on March 31, 2016 21:45

March 29, 2016

Middle-Eastern Intrigue Comes to Connecticut: The Unwilling Pawn by Vaughn Keller

A convincing and gripping read, with engaging characters, a well-developed plot, and insight into the international forces that place a visiting student from Turkey in danger from religious fanatics, "The Unwilling Pawn" by Vaughn Keller has a lot going for it. A midlife career change has vaulted our hero, Frank Kelly, a widower with two young adult children, into the security business when his company takes on the job with big international implications. The cloistered, immature son of a major Turkish political player has come to study law in a university just outside of New Haven. But radical backers of a movement to turn Turkey into a so-called Islamic republic are threatening the boy's safety as a means to put pressure on his father, a supporter of a strongly secular Turkish state. Among his book's strengths are Keller's realistic portrayals of the Kelly family dynamics as Frank Kelly's children try to keep their 'old man' out of trouble, while getting as deeply involved as they can. A cast of sympathetic characters enrich a closely narrated procedural thriller as Kelly's security team plays cat and mouse with a shadowy terror-team whose moves can only be guessed at . When expert assistance on political and religious currents in contemporary Turkey are provided by an intriguing woman with an unusual past (no spoilers!), Frank's life becomes still more interesting. But despite the good interpersonal vibes, when their Turkish playboy unwisely slips his leash and exposes himself to his enemies, we're plunged into a fast-paced, high-risk race to save a life and prevent an international crisis. After finishing this book, I'm looking forward to the future adventures of savvy security specialist Frank Kelly and company.

A personal note: For this reader, the greater New Haven setting, extending to the quiet woods of Sleeping Giant Park, setting brought back nostalgic memories.

A personal note: For this reader, the greater New Haven setting, extending to the quiet woods of Sleeping Giant Park, setting brought back nostalgic memories.

Published on March 29, 2016 13:38

March 27, 2016

The Garden of Philosophy: Finding Truth (and Inspiration) With Your Feet

Apparently, it says here, if I wish to have creative thoughts, and then go write them down, I'd better get back to walking. In a piece on the openculture.com website, Josh Jones writes that a body of thought in both the Western and Eastern traditions suggests that mindfulness, freedom from routine thought patterns, and what Nietzsche termed "all truly great thoughts" are generated by walking. (Here's the link to the complete piece:

Apparently, it says here, if I wish to have creative thoughts, and then go write them down, I'd better get back to walking. In a piece on the openculture.com website, Josh Jones writes that a body of thought in both the Western and Eastern traditions suggests that mindfulness, freedom from routine thought patterns, and what Nietzsche termed "all truly great thoughts" are generated by walking. (Here's the link to the complete piece: http://www.openculture.com/2015/07/ho...) "Many a poet and teacher has preferred the ambulatory method," Jones writes, to produce the meditative tradition's goal of mindfulness. Aristotle's school in ancient Athens was given the name "peripatetic" because (legend has it) he preferred walking while delivering lectures on, say, physical science, metaphysics, politics, ethics, poetics, cosmology and all those other subjects on which his teachings were long considered the last word until about the time of, say, Galileo. Of course, all that talking while walking might have made it a little hard on students trying to take notes. Our main sources for Aristotle's philosophy are (in fact) believed to be students' lecture notes.

Among other thinking-walkers, Nietzsche is quoted as saying that walking is “the best way to go more slowly than any other method that has ever been found.” Other candidates for the school of walking: Thoreau (who walked straight from Concord to Cape Cod, stopping in Plymouth where he almost drowned trying to walk across Duxbury Bay at low tide), the poet Rimbaud, the noble-savage philosopher Rousseau, the clockwork philosopher Immanuel Kant, who left his house at exactly the same moment every day for the identical stroll. Another take on creative walkers comes from a book titled "Wanderlust: A History of Walking" by Rebecca Solnit, who examined the role of walking in the lives of real and fictional persons such as the poet Wordsworth who hiked all over England and Scotland (sometimes accompanied by fellow 'Romantic' poet Coleridge), Jane Austen's fascinating independent thinker Elizabeth Bennett, and the 20th century zen-influenced American poet Gary Snyder. Ah, if only the legs were as young as they once were. Solitary walking in natural or 'wild' spaces was in fact the only sure release from the miserable, negative thought patterns that visited me in certain difficult, unhappy periods of ill spent youth. The best place for a walk was the most remote place one could reach. Since I was living in New England, remote was at best a relative term, but getting lost in a stretch of woods where you were unlikely to run into anyone at all for a good piece of time, released whatever agitated spirits, happy or sad, that needed to get out. I'm making this sounds more therapeutic, I know, than creative, but for me these solitary exercises in locomotion were where the poems and the stories got started. The desk time would come later. You needed to release the pent-up spirits first. You need to get the mind and the body (the mind-body, perhaps) going. My walks are way more modest these later days. I live in a city. I initiate a nature walk by starting the car. Increasingly a creature of habit (Immanuel Kant's 6 p.m. outings don't seem so pathetic to me any more), I drive the few minutes to a salt marsh graced with a hillock and some tame woods, and maintained by the city just enough to keep a "nature walk" footpath open. The footpath through the marsh is a short walk through a place impossible to get lost in. Sometimes I run into another human, almost always accompanied by a dog. But for a little while I'm breathing air sluiced by the elements. Sky, water, vegetation, decay, renewal. Sometimes I meet a hawk. Occasionally a great blue heron pops up out of nowhere. At the end of it I drove home and go back to whatever I was doing. But I am always a little different -- a little aired out, pumped up, cleaned out, mentally re-set from the outdoor experience. What's good for the body is good for the mind. Recently I've been coming back, slowly, from a surgery that proved more complicated than anticipated. The weather's been a typically raw, unstable, changeable, teasing March; promising something, delivering less. It almost always feels too cold to go for a walk. But I have to get myself going again. It's time to go back to those walks.

Published on March 27, 2016 20:55

March 26, 2016

The Garden of Verse: Statues, Long Nights, Lilacs and Matthew

Among my favorite poems in the March issue of Verse-Virtual.com, the online poetry journal that publishes a new issue every month... A set piece poem for a set piece work of art that somehow humanizes and makes the "The Mendelssohn Statue in Leipzig," a project slow in developing in postwar German after the Nazis destroyed an earlier statue to the great 19th century composer, endearing and laudable despite its tortured origins. I've never been to Leipzig, or Germany, but I feel I've received a history lesson and a cultural one after reading Robert Wexelblatt's poem. The composer Felix Mendelssohn was the grandson of the great Jewish thinker Moses Mendelssohn.The poem teaches us of Felix's fathers anguished feelings over his decision to convert to Christianity and later change the family surname to something less Jewish.

Its poem's description of the statue is charmingly ambivalent:

A lyre-bearing muse, looking like a

foot-sore tourist, rests on the steps below

the Master. On one side a pair of angels

scrape a violin, blow a flute; on the other,

a brace of cherubs work through a vocal score....

This thing looks echt Victorian

though it’s not yet a decade old.

I admit to finding Felix a romantic figure, a better behaved Mozart perhaps who got jazzed up by places like Scotland. The poem sums him up better:

His gaze

is fixed. He could be looking back to the beloved

Bach or forward to a quasi-Jewish Mahler.

I feel learning the history of the dilatory replacement of the statue tells me something too about the culture that produced both the composer and this final reckoning. By the poem's end I find myself caring about the statue, wishing to know even more about the Mendelssohn family, and sure that if I ever go to this city I would look for this somewhat tortured recognition of a famous local son.

A poem with a more directly religious theme, Laura Kaminski's "Confirmation: poem ending with Matt. 18:4 KJV" says things about religious belief that I've always meant to say, and says them beautifully:

All the complexities of creeds seem to me like sieves,

fine mesh strung to strain out heresy and apostasy,

wires stretched like prison bars to keep out questions

and their askers. And I've been challenged: do I not

strive to earn a place within the heavens? But how can

an infant pay the rent on such a lofty crib? What must

an infant do to earn a meal? I can only say that I am

racked with hunger, wail in poems, cry in silence

for the remembered sweetness, for a taste of the Beloved.

The absurdities of orthodoxy are "strained out" here in such fitting imagery. How would "an infant" -- or, for that matter, any solitary soul -- decide how to earn a spot in heaven? Are we not more likely to do as the poem puts it, "cry in silence/for the remembered sweetness, for a taste of the Beloved"? "Confirmation" ends with the citation from Matthew, affirming as godly the stance of whoever "shall humble himself as this little child..."

That feels right to me as well. Doctrine matters not a whit. The heart is all.

In keeping with my admiration for (or vulnerability to) deeply felt poems, I responded to Michael Minassian's "On The Maryland Coast," a poem that captures an experience many of us can no doubt relate to. The poem recalls an evening spent with that rarely encountered ideal other, talking about writing and reading one another's latest poems:

you were so intense, your face a map

not too different from my own story.

Sometimes we do see ourselves in another person; and perhaps we remember those moments forever.

I also admired the poet's sharply written "The Postcard on Reverse," a poem that describes time as "a group of islands/ & the wooden skeleton/ of a wrecked steamboat" and offers a picture of the stained glass windows of a cathedral

when lit by the sun/

like a row of teeth, sharpened."

Pretty pictures, the poem suggests, sometimes cover up a multitude of sins. Tom Montag's series of poems about 'elemental' conditions (to borrow from the title of one of these, "These Elementals") ring particularly true to me following a period of much waking during the darker watches of the night followed by long waits for dawn. At the end of "Day, Breaking," his poem offers this reward:

What we get is another

fragile day holy with

promise of farther light.

In a similar vein, I appreciated these lines lines from "Elementals":

We are not what we think we are.

The stars know that. All night they tell us

all things come again to nothing.

Lastly in a poem called "Lilacs" that begins

O, let the lilacs

come like a dream,

the poet offers this just-right observation:Not their color but

the frank scent of them...

Strong words in these poems, for strong emotions.

Kathleen Brewin Lewis's poem "Re-turning," also touched a nerve. It's a poem about beach memories, probably we all have them, and I found a particular moment evoked strongly and irresistibly in the line "the sand liquescent dribbling through our fingers." The poem's evocation of such moments is so right that I was both surprised and completely satisfied to be asked to imagine it last line: "the sea flings sheets upon the shore."

See all these poems and others at

http://www.verse-virtual.com/current-...

Published on March 26, 2016 15:14

March 22, 2016

The Garden of Old Friends: Big Night for "Suosso's Lane" in Plymouth

Plymouth Public Library gave me and "Suosso's Lane" a big hand up a week ago when folks packed the library's meeting room for my program on the book. Lots of folks I haven't seen for years -- some of them remembering me from my days working for the Old Colony Memorial; others remembering Anne and me from our years living in Plymouth and asking after Sonya and Saul -- showed up for my talk spiced with a few excerpts. Many came up to say hi afterwards.

Plymouth Public Library gave me and "Suosso's Lane" a big hand up a week ago when folks packed the library's meeting room for my program on the book. Lots of folks I haven't seen for years -- some of them remembering me from my days working for the Old Colony Memorial; others remembering Anne and me from our years living in Plymouth and asking after Sonya and Saul -- showed up for my talk spiced with a few excerpts. Many came up to say hi afterwards. I spoke on stumbling on Vanzetti's history in North Plymouth, looking up the local newspaper coverage of the world-famous Sacco-Vanzetti case (not much) in the library's reference room. And being shown by the late Lee Regan, the library's crackerjack reference librarian, where the library kept its books on the case in its local history collection. After taking questions, we gave away a few of the not-for-sale copies through a bookmark lottery. Anne gave a power-point demonstration on how to buy the book from the publisher's website: www.web-e-books.com/index.php#load?ty... Folks ate up all the Italian cookies and pastries we brought. Had we anticipated the size of the crowd better, I would have brought more. Library staff also took event photos, a couple of which I've posted here. All and all, a great night. To top it off, the next day "Suosso's Lane" received a new review from a fellow writer. Robert Wexelblatt is the author of the recently published short story collection "Heiberg's Twitch" and two other story collections. He's also a widely published poet and a Boston University professor. Here's the review: "The book is exemplary in so many respects: for the keenness of its informed historical imagination, an inventive structure in two periods separated by 80 years, for conveying a vivid sense of place, managing storytelling that is both intimate and epic with the invented story as involving and moving as the well-retold historical tale of injustice. It’s a mystery; it’s a love story; it’s a family story; it’s a young person’s story and an old one’s too. Romance, arson, murder, Plymouth, Boston, economic history, political intrigue, real-estate shenanigans. Points of view in great variety, from children to aging widows, young college instructors to a Ghanaian immigrant. It’s an ethically sensitive story that slights neither cynicism nor idealism. And it’s so well written – prose, but prose from a poet." -- Robert Wexelblatt.

Talk about good writing! Thank you, Wex.

Published on March 22, 2016 19:58