Robert Knox's Blog, page 38

July 29, 2016

Civilization's Garden: We Are All Aleppo

[photo by anjci - http://www.flickr.com/photos/9899582@..., CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... ]Shakespeare's audience was likely to appreciate the geographical reference in the last sentence of Othello's powerful, horrible, final speech, as he acknowledges the horror of the act he has just committed in killing his innocent wife, after his mind was treacherously poisoned against her.

[photo by anjci - http://www.flickr.com/photos/9899582@..., CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... ]Shakespeare's audience was likely to appreciate the geographical reference in the last sentence of Othello's powerful, horrible, final speech, as he acknowledges the horror of the act he has just committed in killing his innocent wife, after his mind was treacherously poisoned against her."I have done your masters some services, he tells the Venetians, for whom he serves as commander and warrior -- though he is not a Venetian himself, but a Moor -- to report the whole truth of the crime he has committed "with no extenuation."Then he states:"And say besides, that in Aleppo once,

Where a malignant and a turban'd Turk

Beat a Venetian and traduc'd the state,

I took by the throat the circumcised dog,

And smote him thus." On that final "thus" he thrusts his sword into his own heart. Aleppo: An ancient city in Syria where Christians and "Turks" (meaning Muslims) once contended for control, during the time of the Crusades. Today that city is being wiped from the earth by the so-called President of Syria and his allies, the perfidious Russians, its people destroyed by cluster bombs dropped from the sky with the intention of killing whoever remains in the city. As the Western democracies who the county's freedom fighters were certain would come to their aid continue to sit on the sidelines and cluck their tongues. Today's newspaper reports that the so-called Syrian government (two words that make no sense together) has offered an amnesty corridor allowing people to leave Aleppo safely for other parts of the country controlled by the government. But the people there say 'What amnesty can we possibly expect when all the men in this place are 'wanted' by the government?' With a population of more than 2 million, Aleppo is (or was) Syria's largest city, and one of the largest in the Middle East. Historically, it was the third largest in the Ottoman Empire. But it's history goes back long before. According to the experts, Aleppo is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, showing signs of human settlement possibly back as far as the 6th millennium BC. The Old City of Aleppo is designated as a World Heritage Site -- once you say that about a place, any place, what else do you need to say about its value? Yet the same designation applied to another ancient Syrian city, Palmyra, whose irreplaceable historic monuments have already been destroyed by the war caused by the murderous gang that runs Syria today, though Palmyra's execution was carried out by the despicable terrorist gang known to us as ISIS, who took advantage of the war to add to the suffering of Syrians and Iraqis. A Silk Road trading center before the invasion of the Mongols, Aleppo became was a major point of contention during Middle Ages when the European crusaders sought to wrest it from the Muslim population. Crusaders besieged it in 1098 and in 1124, they failed to take it. Syrian Christians (a significant Christian population remains in Syria today), however, established their own quarter outside the city walls in 1420. The dictatorial Baathist Syrian government, which has ruled Syria since 1970 (with its capital in Damascus) has presided over decades of economic decline in Aleppo. Ironically, the decline may have helped to preserve the Old City of Aleppo, its medieval architecture and traditional heritage. Since 2012 that heritage has suffered series losses, souqs, mosques, and medieval buildings have been partially or wholly destroyed in fighting for the control of the city. Worse is happening today.

So how does Shakespeare's reference to Aleppo in Othello's about-to-self-slaughter speech help us understand the city's importance? Othello, as we are told repeatedly in the tragedy that bears his name, is a "black" Moor, that is to say a Muslim from Morocco. The Moors invaded Europe in the 8th century, conquering all of the Iberian peninsula and spreading into southern France before their advance was halted. This real significance of this incursion was that while most of Europe languished for a millennium in "Dark Ages" ignorance, cultural fragmentation, and disconnection from the classical civilization of the ancient Rome and Greece, cities in southern Spain became centers of culture, art and learning, because the Islamic Empire retained the learning and preserved that civilization's books and contributed to classical traditions of learning in fields such as mathematics, science, music and poetry. And, in the most important of Spain's medieval kingdoms did so in harmony with its Christian and Jewish population. Nevertheless, times change, and Othello became a mercenary soldier serving the Christian power of Venice, the most important rival to the empire now ruled by the Turkish-dominated Ottoman Empire -- hence Othello's to the "malignant Turk." Who interestingly is also called "a circumcised dog." (Should we think of Othello as a self-hating Muslim?) When Othello chose to throw in his lot with Venice, a late-Medieval and Renaissance Mediterranean power, Western civilization had been centered for millennia upon the Mediterranean coast of Europe, North Africa and what we now call the Middle East. Even at the time he wrote, Shakespeare's England was still a relatively insignificant island redoubt, a minor player in world affairs though it has managed to fend off the aggression of the Spanish Empire and the secede from the Roman church -- both of which were then strongly among major players. And as we trace the roots of Western Civilization further back in time, we see that everything goes back to the cities and settlements in places we now call Syria, Iraq, and Egypt. Agriculture, the essential basis for that bastion of civilization, began in Mesopotamia (Iraq), the first cities and codified legal systems were found in Babylon; religion, art, monumental architecture go back to Egypt and the other cities of the Middle East. Monotheism first appears in the Zoroastrianism of Persia, and took root in Palestine. The Greeks learned the alphabet from Byblos, a Phoenician city on the shore of what is now Lebanon. Quite possibly they also learned the seafaring and trading business which provided the economic foundation for their civilization from the sea-faring Phoenicians. And they they were much impressed by the dramatic careers of the gods of Egypt. The Romans learned from the Greeks, and from everybody else who came before. That's what they were good at -- along with imperial infrastructure building. The Romans planted cities, including a few in England. This is the cultural and intellectual ancestry of the West, our roots. These early nations provided the great fore-running monuments of our civilization, we are watching be destroyed. Othello, a Muslim, chose to serve a Christian power that fought and competed with Ottoman Islamic empire, helping to slow its westward expansion. Somehow the divisions of medieval Europe versus the Muslim "East" still bedevil us. We were still barbarians when they were learned, studying the Greeks and writing books, up to the time of the Renaissance, the recovery of classical learning, and the Enlightenment and rebirth of science in northern Europe. From that time on Europe learned fast and countries such as England and the US jumped to the head of the line and pranced as dominating characters on the world stage. But as civilized peoples, nations of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East all have the same roots. Everybody in the Western Civilization comes from the same source. And I can't understand how we can stand by, year after year, and see the treasures of that inheritance destroyed.

Published on July 29, 2016 16:07

July 24, 2016

The Garden of Verse: Mysteries in Plain Poetic Sight

There are many mysteries among the poems that delighted me in July's Verse-Virtual (http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...). Michael Minassian's poem "The Fortune Teller" reads like a deep parable with too many possible meanings for any of us to sort out simply. It features a Korean fortune teller, a finch who apparently understands Korean (and performs gymnastics in a cage), an angry exchange not simply or words but of roles, a mysterious neighbor, and a finale in which the poet carries a bird on his tongue. Well, doesn't he? You have to read it. In another poem, "Three Days After the Fourth of July," we meet a neighbor (the neighbor of the foretelling? I don't know) getting publicly drunk on his lawn. In a fitting gesture for a national holiday the poet's waving notebook becomes "a white flag,/

There are many mysteries among the poems that delighted me in July's Verse-Virtual (http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...). Michael Minassian's poem "The Fortune Teller" reads like a deep parable with too many possible meanings for any of us to sort out simply. It features a Korean fortune teller, a finch who apparently understands Korean (and performs gymnastics in a cage), an angry exchange not simply or words but of roles, a mysterious neighbor, and a finale in which the poet carries a bird on his tongue. Well, doesn't he? You have to read it. In another poem, "Three Days After the Fourth of July," we meet a neighbor (the neighbor of the foretelling? I don't know) getting publicly drunk on his lawn. In a fitting gesture for a national holiday the poet's waving notebook becomes "a white flag,/spreading across the wide continent." It all fits together, mysteriously, poetically, so.

"One Time," anaffecting poem by Susan Deer Cloud, tells of her mother, who grew up during the Great Depression and sought solace in the fields, the earth and the "black breathing" beyond. "She thought

she could ignore hunger,

forget her father’s claimtheir people were no different

than the extinct panthers."The poem's stunning last line suggests that 'her father's claim' may not be the whole story.

Joan Mazza writes of another mysterious guest in "Filamentous Algae," a new arrival in a local pond, following the sometime residence of lotus and bullfrogs and herons."Uninvited, you arrived in late spring. I spied

you from my office window, weaving mats

on the pond’s surface with your long hair."As the accompanying photo suggests, long hair this thick can be dangerous. The poem concludes with an unexpected change in frame of reference, from environmental to personal, that leaves us surprised and thoughtful.

Ryan Warren's "Wind Horses" captures a perhaps universal human feeling and makes us feel it, in our animal selves. Watching those wind horses drive though the frigid ocean, the poet writes:

"Oh, how the ancient

mammalian map

within me yearns so

to curl up tightly,

to wrap my long tail

around my wet nose

and sink down into

some dark winter cave.

I love this poem's descriptive imagery -- "Each cresting curl

streams a white mane..."; "The gauzy curtain

of rain undulates..." We will grow tired of witnessing the world.

Then we come to DeWitt Clinton's incredible series of contemporary adaptations of poems by Tu Fu. What a project! I like all of these efforts in the July Verse-Virtual. I find them naked, vulnerable, moving, witty, open and unsentimental. We're tempted to think of concretely descriptive, contemporary first-person poems as "confessional," but the confessional approach may be a mask, the adoption of a persona, the way Tu Fu adopts a face for certain poems. Maybe we should think of the "I" of these poems as a Tu Fu descendant. I love the titles of these poems, such as:"Hanging in Rope Sirsasana, and Later, Lying in Supta Baddha Konasana,

I Realize How Eager I am to open the Page to Find Tu Fu’s 'Visitors'” ... a poem in which, if I have the right one, Tu Fu subtly takes down the pretensions of an official visitor by emphasizing the spare homeliness of his own dwelling and way of life while employing the language of courtesy. Clinton's poem begins: "It’s been so long now, I wonder about all who

Come for tea, and why so few find their way..." And ends with the poem's speaker praising the quietness of his own nights, with no apparent irony:"Spies, lovers, medical examiners,

Aliens, all stop by to wish us a safe and dreamy night." Brilliant line; I think I've been there.

This is followed by "Sunday Afternoon, Northern HemisphereAfter Travelling 36 Miles Nowhere on a Stationary Bike

I Peer Out the Window and See Tu Fu

Sipping Wine, Composing 'Sunset'"

Tu Fu's poem, in its Kenneth Rexroth translation, consists of a mellow description of sights by a riverside and ends with the observation that one good, thick glass of wine can dispel all your worries. Clinton's poem, a minor key reply, ends with remembering those you have lost.

In "After Watching Another NCIS Episode, I Retreat to My Office To Read ' Pass the Night at General Headquarters' by Tu Fu," the speaker is a Vietnam veteran following the news of the war in Afghanistan. "Sometimes," he says,

"I wonder if I’ve ever left my post, still

Shouldering an old rusty M16, long out

Of ammo, stuck on Hill 477 in camouflage."All of these are beautiful, and leave us with mysteries to contemplate.

Published on July 24, 2016 14:20

July 21, 2016

The Garden of History: The Meaning of Populism

The correct term for the politics of the candidate the Republican Party has just nominated for president and for those who support him is not "Populist" as the press and media insist on calling it, but "nativist." Nativism is the belief that people born in a certain place -- that is, one's own country -- are somehow better than people born anywhere else. No evidence is offered. It's an article of faith. A belief that many hold onto tightly despite the evidence that lots of people born somewhere else and now living in the US (often after great risk to their own safety) are working harder and contributing more to society than they are. Have we stopped teaching the essence of our history in our schools? We are a nation of immigrants. Today we have a self-proclaimed billionaire (who refuses to release his tax filings) running as a representative of what the media routinely calls "Populism," but is really nativism, gingoism, xenophobia, and pure and simple racism. Here's the Wikipedia definition of Populism: "Populism is a political position which holds that the virtuous citizens are being mistreated by a small circle of elites, who can be overthrown if the people recognize the danger and work together. The elites are depicted as trampling in illegitimate fashion upon the rights, values, and voice of the legitimate people." For the words "virtuous citizens" in the definition above I would substitute "common people." The common man was a term of approval used especially during the first half of the 20th century for those harmed by what Teddy Roosevelt called the "malefactors of great wealth." The common man's enemy was the accumulation of great wealth and the consequent concentration of economic and political power in the hands of a few, to the detriment of the many. As for "elites," certainly in the American context we are not talking about pointy-headed intellectuals, ivory tower academics, entertainment celebrities or overpaid professional athletes. American Populists were talking about monopolies, big banks, Wall Street, and the politicians who served their interests -- rather than those of farmers and laborers. As for the "common man," consider the title of Aaron Copland's long-popular "Fanfare for the Common Man." A fanfare is the music used to signal the arrival of a monarch, or someone of great importance. Copland's title for his consciously American composition emphasizes that this is a country without monarchs, one that recognizes and celebrates the importance of the 'common man.' American presidents from the time of Jackson and Abraham Lincoln were born in log cabins. In this country it's a matter of both law and principle that the farmer and the factory worker (and the counter woman at Dunkin Donuts) remains the equal of the aristocrat or the trust-fund baby or the plutocrat. American political Populism was a largely a late 19th century agrarian movement begun by farmers, especially those living in the traditional Western farming states, who used the ballot box to seek a fairer deal from the institutions holding power over their livelihood through the concentrations of money and credit in the banks and investment houses of the big cities, mostly in the Northeast and a few cities elsewhere. Farmers and small business oweners wanted "more money" in circulation, loose money policies rather than tight, looser credit rules, and lower interest rates on their loans. Since they couldn't run their farms (or stores) without credit, they believed they were being exploited by the tight-money, high-interest policies of the big banks that controlled the money supply. Their natural allies were the factory workers who were underpaid and exploited by the wealthy companies that employed them. In this country at least, Populism was historically a left-wing, Progressive movement rather than a right-wing or conservative movement. The Wikipedia states: "In the United States populist movements have high prestige in the history books, for example, farmers' movements, New Dealreform movements, and the civil rights movement that were often called populist, by supporters and outsiders alike." In the European historical context, according to a historian cited by the Wik, the term Populist has been more often used to label nativist movements, some of which in the previous century turned to fascism. The trend to call nativist groups Populist

The correct term for the politics of the candidate the Republican Party has just nominated for president and for those who support him is not "Populist" as the press and media insist on calling it, but "nativist." Nativism is the belief that people born in a certain place -- that is, one's own country -- are somehow better than people born anywhere else. No evidence is offered. It's an article of faith. A belief that many hold onto tightly despite the evidence that lots of people born somewhere else and now living in the US (often after great risk to their own safety) are working harder and contributing more to society than they are. Have we stopped teaching the essence of our history in our schools? We are a nation of immigrants. Today we have a self-proclaimed billionaire (who refuses to release his tax filings) running as a representative of what the media routinely calls "Populism," but is really nativism, gingoism, xenophobia, and pure and simple racism. Here's the Wikipedia definition of Populism: "Populism is a political position which holds that the virtuous citizens are being mistreated by a small circle of elites, who can be overthrown if the people recognize the danger and work together. The elites are depicted as trampling in illegitimate fashion upon the rights, values, and voice of the legitimate people." For the words "virtuous citizens" in the definition above I would substitute "common people." The common man was a term of approval used especially during the first half of the 20th century for those harmed by what Teddy Roosevelt called the "malefactors of great wealth." The common man's enemy was the accumulation of great wealth and the consequent concentration of economic and political power in the hands of a few, to the detriment of the many. As for "elites," certainly in the American context we are not talking about pointy-headed intellectuals, ivory tower academics, entertainment celebrities or overpaid professional athletes. American Populists were talking about monopolies, big banks, Wall Street, and the politicians who served their interests -- rather than those of farmers and laborers. As for the "common man," consider the title of Aaron Copland's long-popular "Fanfare for the Common Man." A fanfare is the music used to signal the arrival of a monarch, or someone of great importance. Copland's title for his consciously American composition emphasizes that this is a country without monarchs, one that recognizes and celebrates the importance of the 'common man.' American presidents from the time of Jackson and Abraham Lincoln were born in log cabins. In this country it's a matter of both law and principle that the farmer and the factory worker (and the counter woman at Dunkin Donuts) remains the equal of the aristocrat or the trust-fund baby or the plutocrat. American political Populism was a largely a late 19th century agrarian movement begun by farmers, especially those living in the traditional Western farming states, who used the ballot box to seek a fairer deal from the institutions holding power over their livelihood through the concentrations of money and credit in the banks and investment houses of the big cities, mostly in the Northeast and a few cities elsewhere. Farmers and small business oweners wanted "more money" in circulation, loose money policies rather than tight, looser credit rules, and lower interest rates on their loans. Since they couldn't run their farms (or stores) without credit, they believed they were being exploited by the tight-money, high-interest policies of the big banks that controlled the money supply. Their natural allies were the factory workers who were underpaid and exploited by the wealthy companies that employed them. In this country at least, Populism was historically a left-wing, Progressive movement rather than a right-wing or conservative movement. The Wikipedia states: "In the United States populist movements have high prestige in the history books, for example, farmers' movements, New Dealreform movements, and the civil rights movement that were often called populist, by supporters and outsiders alike." In the European historical context, according to a historian cited by the Wik, the term Populist has been more often used to label nativist movements, some of which in the previous century turned to fascism. The trend to call nativist groups Populist is appears to me to be a recent usage relied on to characterize the right-wing anti-immigrant parties that have won some support at the polls in France and Britain and other countries without calling them by a term that has 'anti-' or some other negative in it. That's a very weak basis for forgetting or ignoring what Populism has long meant in American politics -- the revolt of the exploited against the rich and the powerful. To be fair, American Populist movements were often sidetracked by social questions that saw them taking a backwards-looking or reactionary position. The "populist" Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan defended a literal understanding of the Bible against the evidence of science. Unfortunate, but it's hard to see why religious-based blindness should permanently tar a movement seeking to enable farmers and factory workers to make a decent living. Progressives had their blind spots as well. Woodrow Wilson's first term as president saw the passage of long-sought legislation to protect child labor and restrict monopolies, but also federal legislation to enshrine racially segregated practices. The scholarly, idealist Progressive Wilson was also, unfortunately, a nasty racist. The factor that seals the deal on what to term the policies (or, more accurately, prejudices) of the newly nominated Republican candidate is his pejorative comments on minorities and immigrants. The better terms for these irrational statements and self-indulgent rants are (I will say it again) nativism, gingoism, xenophobia, and pure and simple racism. The single most ignorant of these indulgences is the tendency to scapegoat immigrants. Everything being said by those who seek to build a wall, discriminate against certain religions, or close the doors on people from certain countries is exactly backwards: Shutting the door on immigrants is shutting the door on ourselves. Let me refer to a few sentences in a final paragraph of a remarkale piece of journalism that appeared in The New Yorker, recounting the life of the "founder" of an Afghan Muslim community in rural Wyoming (or all places) that now numbers a couple of thousand. The piece is titled "Citizen Khan: Behind a Muslim commnity in northern Wyoming lies one enterprising man -- and countless tamales." The article also told me something that I never knew: that America's exclusionary immigration laws (such as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act) left courts to decide who was "white" and therefore eligible for entry into the US and ultimately citizenship and who was not. The "Citizen Kahn" of the story (Zarif Khan) was denied citizenship by a court that ruled that he was from Asia and therefor not white; and decades later granted citizenship by another when the rules had changed.

Is this the America that the contemporary nativist movement wants to go back to?

Here's the link to the article: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/201... The sentences I wish to quote are these:

"Over and over, we forget what being American means. The radical premise of our nation is that one people can be made from many, yet in each new generation we find reasons to limit who those “many” can be—to wall off access to America, literally or figuratively. That impulse usually finds its roots in claims about who we used to be, but nativist nostalgia is a fantasy. We have always been a pluralist nation, with a past far richer and stranger than we choose to recall. Back when the streets of Sheridan [Wyo.] were still dirt and Zarif Khan was still young, the Muslim who made his living selling Mexican food in the Wild West would put up a tamale for stakes and race local cowboys barefoot down Main Street. History does not record who won."

Published on July 21, 2016 11:51

July 17, 2016

Learning from History

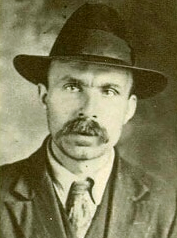

I'll be speaking on my novel "Suosso's Lane" and reading a few excerpts at the Paul Pratt Memorial Library in Cohasset, MA, next Saturday, July 23. With terrorist attacks, attempted coups, and right-wing targeting of immigrant groups, 2016 is growing remarkably similar to the year 1920 when Nicola Sacco and Plymouth resident Bartolomeo Vanzetti were arrested in a climate of violence and political repression.

I'll be speaking on my novel "Suosso's Lane" and reading a few excerpts at the Paul Pratt Memorial Library in Cohasset, MA, next Saturday, July 23. With terrorist attacks, attempted coups, and right-wing targeting of immigrant groups, 2016 is growing remarkably similar to the year 1920 when Nicola Sacco and Plymouth resident Bartolomeo Vanzetti were arrested in a climate of violence and political repression.In 1920 America was reeling from the effects of World War I, inflation, unemployment, increased crime, bootlegging violence and a bombing campaign that shocked and terrorized the nation even though casualties were few. Anarchists, a left-wing revolutionary group persecuted by the government for its opposition to American participation in the war, were blamed for the bombs. And many of America's anarchists were European immigrants.The federal government responded by targeting immigrants in massive round-ups, detainments, and deportation orders -- most of these later declared illegal -- in a campaign of repression called the Red Scare.

In this climate of fear and unease, a daring daylight payroll robbery in the quiet Massachusetts town of Braintree, accompanied by the killing of two payroll officials, shocked the public and was front-page news. Witnesses thought the criminals looked like immigrants from southern Europe. Maybe Italians. A local police chief theorized that the criminals were anarchists, because an Italian anarchist was renting a house in his town of Bridgewater and the car used in the holdup has been abandoned two miles away in the woods in Bridgewater. That was all he had to go on, but Sacco and Vanzetti, both Italian immigrants, and both anarchists, were charged with the crime when they were caught one night leaving the town of Bridgewater.

In a time of troubles when ordinary citizens worry about their safety, societies have a tendency to turn on members of "outsider" groups and suspect they're the cause of criminal acts. In the 2016 presidential election campaign, we've already seen a leading candidate make sweeping attacks on national and religious minorities. Should all Mexicans or Muslims be presumed to be the enemies of America's public safety? Can you imagine a time when people of Italian descent were looked at that way?

The events recounted in "Susosso's Lane," while they took place a long time ago, raise questions that are still with us. Do we learn from the past? Can we? Just maybe it helps to remember what happened long ago in 1920's America.

Here's the press release from the Cohasset library:

"Robert Knox, author of Suosso’s Lane, will give a book talk on Saturday, July 23, 2016 at the Paul Pratt Memorial Library, 35 Ripley Road, Cohasset 2:00-3:00 pm. The book is based on the scandalously unjust trial and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti for a murder most people believe they did not commit, the international cause-celebre of the 1920’s, Knox’s novel follows the search for evidence of Vanzetti’s innocence lost for decades to a government sanctioned frame-up.

"Free. All are welcome. Call the library for more information at 781-383-1348."

Published on July 17, 2016 10:54

July 16, 2016

Garden of Literature: Kate Atkinson's 'When Will there Be Good News?" is the Best Book I've Heard...

... in quite some time.

... in quite some time. Ah, the British voice. They sure know how to speak the language. Actually, of course there are a lot of languages spoken over there on the other side of the pond that all go by the name of "English." The characters in Kate Atkinson's novels speak most of them.

I'm thinking of the book that I just finished -- I can't say "reading" -- but "hearing" on a set of a dozen discs that may be the best medium for enjoying this quality in her writing. The book ("When Will there Be Good News?") is a read by a British actor -- I don't have his name here -- able to slip from one lingo, tonality, patois, regional or national intonation to the next without any audible stress or strain.

Maybe everything is simply funnier or more apt when you're hearing the words the way they are supposed to be spoken.

What makes for brilliant characters in a work of fiction?

Is it that they have their own voice? And exactly a voice that suits their role in the fictional community they're part of?

Listening to this book read to me as I drove the car, rather frequently inventing a reason to hop into the car purely for the pleasure of hearing it, I would welcome the turn of the narrative from one central character to another and think, 'oh good, we're back to so-and-so. After a while it occurred to me that I was thrilled to return to the trials and tribulations of every single one of these characters. I didn't have a favorite. They were all my favorites. It was like getting the latest update from a half a dozen great storytellers -- every day! One after another.

Atkinson is a purveyor of what I'm starting to call "ensemble fiction." Her books don't have a 'main character.' They have a clutch (what Vonnegut called a 'karass') of main characters, each the hero of his or her own story, predicament, crisis, point of view on life, and sole possessor of her own 'voice.' Inevitably these characters cross paths, but seldom in predictable ways. We wait for these intersections; we don't always see them coming.

These crossings don't necessarily resolve the action, solve the big problem, etc., but they intensify it. And not all the problems are resolved. Our lonely male private detective goes on being a lonely detective. Our obsessed female police detective anticipates leaving her 'perfect' husband, but it doesn't happen in these pages -- maybe in some other fictional universe (i.e. another book).

"Good News" begins with the starkest of beginnings, a conventional nuclear family grouping (mother and three young children) attacked and murdered by a deranged stranger on a lonely country road -- except for "the one who got away." A child named Joanna will always be 'the one who got away,' the narrator tells us.

We live in the era of crime stories. In fiction, both pulp and high-toned, in film, press reportage, daily news flashes on TV, and the countless dramatic series we all watch on networks or Netflix. Truman Capote's ground-breaking study of the hideous criminal act of violence randomly visited on 'ordinary people,' (titled "In Cold Blood") -- a daring literary choice 50 years ago -- seems a humdrum plot premise today.

It's odd to think of top-drawer literary fiction writers routinely choosing to write "crime fiction," as Atkinson does, until I realize that crime fiction, an outgrowth of the traditional 'mystery' or 'detective story' genres, is increasingly the method of choice for exploring normal, everyday life for ordinary people in contemporary society. That is to say, what Atkinson is doing is exactly what "literary" fiction has long purported to do. Or realistic fiction. Or "serious" fiction intended to address social 'problems' or issues or conditions.

Atkinson's fascination with survivors of terrible, random-seeming tragedies possibly mirrors the return of the ancient conundrum of fate. How do the survivors deal with it? How do any of us deal with the fact that somebody else 'gets it,' while we walk away unharmed. It's metaphysical rubber-necking.

A quick look at the characters, and a few plot premises, illustrates this point. Insofar as it's Joanna's book, this is a story about what it's like to be a survivor.

"Everybody's dead," laments Reggie, a young-looking sixteen, Scottish and alone in the world, aside from her hooligan brother, who is himself a harbinger of violence. She's also, as Atkinson allows somewhere in this book, "a force of nature."

To Reggie's lament, offered in her bright, false-enthusiastic Scots soprano, Atkinson's war-horse PI Jackson Brodie stoutly replies, "I'm not." That's largely because when Brodie was flattened by a literal train wreck, Reggie in her doughty juvenile do-the-right-thing innocence went searching through the victims until she found someone with a hint of a pulse able to benefit from her improvised resuscitation.

After the accidental death of her mother, and faced with living on her own, Reggie works as a 'mother's helper' for the medical doctor who the reader eventually realizes is the grown-up version of Joanna, the "one who got away" and now grounds her reason to live in the creation of her own family. When Brodie appears, he's already the victim of a crime he doesn't yet know about. But Brodie is also a survivor of the random, senseless criminal sort of tragedy since his sister was the victim of a rape-murder in her teens. One of Atkinson's lessons about contemporary life (though this was no doubt always the case) is you never forget this kind of loss. You never 'get past it.' You're not a cripple; you 'go on,' as her characters say, but they always carry the weight. The writer's ability to make us understand the role of this weight in human beings' inner lives is part of the book's special value. It's the kind of thing we read books for. Then there's the police detective Louise, who apparently has popped up before in a book I haven't read yet, because she and Brodie have crossed paths in the past. Louise survived a different sort of loss, the absence of anything resembling an 'ordinary' childhood because her mother was a dysfunctional alcoholic. Louise, much to her own surprise, has a problem-free husband, but her own darker, fiercer sensibility keeps him at arm's length. And, as one of those police detectives who never leave the job at the office, she's obsessed with the perpetrators -- and the victims -- of terrible violence committed on helpless victims, whether they are completely random or all in the family.

But their voices -- that's what keeps you glued to every word in this book. Keeps you replaying the segment of the disc where you might have a missed a single reply or caustic flourish of musing, or allusion to some bit of English nursery rhyme or grade school poetry, or line of Shakespeare, because the light changed suddenly or some idiot cut you off.

Several ranges lower than Reggie's tweety Scottish, Brodie sounds like a common man of the North, no soft, clever upper-class Southron presumptions. Yet his soldier-policeman-PI straight-forward man of duty appropriation of the common tongue is laced with a streak of self-questioning a railway wide and ornamented with a collection of verses he was forced to memorize in an oppressive working-class childhood by his hard-assed teachers. A remarkable percentage of the poetic allusions here come from him.

Louise is from the North as well, and the way her hard-scrabble vision of the human predicament influences her speech is react to developments as if all news is 'likely bad.' Along with her absolute inability to soften her world-view to be 'nice' or get along. Along, also, with a complementary willingness to lie like a rug if it advances an investigation.

Joanna, the full-on loving Mom and devoted baby worshiper, is the one who takes the common sense route of making the best of things, seeing the ray of sunshine in the wintry storm in a plain unpretentiously sensible sound-of-today voice. She has also apparently absorbed all the English nursery rhymes and children's books in the English canon (or, perhaps, Atkinson has) and drops in their wisdom or apt illustrations lightly, as if to oil the surface of the planet's daily rounds.

I can go on, as we say these days. But without spoilers, it's fair to say that all of these characters cross paths in completely engrossing, satisfying ways. And such fun to hear them narrate or even, perhaps, may we say 'sing' their own separate parts of the world's business exactly in key.

Published on July 16, 2016 20:50

Garden of Literature: Kate Atkinson's 'When Will there Be Good News?" is the Best Book I've Heard,,,

In quite some time.

Ah, the British voice. They sure know how to speak the language.

Actually, of course there are a lot of languages spoken over there on the other side of the pond that all go by the name of "English."

The characters in Kate Atkinson's novels speak most of them.

I'm thinking the book that I just finished -- I can;t say 'reading' -- but hearing on a set of a dozen discs may be the best exemplar of this highly enjoyable quality in her writing. The book ( 'When Will there Be Good News?") is a read by a British actor -- I don't have his name here -- able to slip from one lingo, tonality, patois, regional or national intonation to the next without any audible stress or strain. Maybe everything is simply funnier or more apt when you're hearing the words the way they are supposed to be spoken.

What makes for brilliant characters in a work of fiction?

Is it that they have their own voice?

Listening to this book read to me as I drove the car, rather freqyently inventing a reason to hop into the car purely for the pleasure of hearing it, I would welocme the turn of the narrative from one central character to another and thoink, oh good, we're back to so-and-so. After a while it occurred to me that I was thrilled to return to the tgrials and tribuations of each of these characters. It was like getting the latest update from a half a dozen great storytellers -- every day!

ATkinson is a purveyor of what I'm starting to call "ensemble fiction." Her books don't have a 'main character.' They have a clutch (what Vonnegut called a karass?) of main characters, each the hero of his or her own story, predicament, crisis, point of view on life, adnd 'voice.' Inevitably these characters cross paths, but seldom in predictable ways. We wait for these intersections; we don't always see them coming.

These crossings dopn't necessarily resolve the action, solve the problem, etc., but they intensify it. And not all the problems are resolved. Our lonely male private detective goes on being a lonely detective. Our obsessed female police detective anticipaes leaveing her perfect husband, but it doesnt happen here -- maybe in some other fictional universe (i.e. another book).

"Good News" begins with the starkest of beginnings, a normal family (mother and three young children) is murdered by a deranged stranger on a lonely country road -- except for "the one who gets away." She'll always be 'the one who got away,' the narrator tells us.

We live in the era of crime stories. In fiction, both pulp and high-toned, in film, press reportage, daily news flashes on TV, and the countless dramatic series we all watch on networks or Netflix. Truman Capote's ground-breaking study of the hideous criminal act of violence randomly visited on 'ordinary people' -- a daring literary choice 50 years ago -- seems a humdrum choice of subject today.

It's hard for me to think of top-drawer literary fiction writers routinely choosing to write "crime fiction," as Atkinson does, until I realize that crime fiction, an outgrowth of the traditional 'mystery' or 'detective story' genres is increasingly the method of choice for exploring normal, everyday life for ordinary people in contemporary society.

Atkinson's fascination with survivors of terrible, random-seeming tragedies possibly mirrors the return of the ancient conundrum of fate. How do the survivors deal with it? How do any of us deal with the fact that somebody else 'gets it,' while we walk away unharmed. It's metaphysical rubber-necking.

"Everybody's dead," laments Reggie, sixteen, Scottish, alone in the world aside from her hooligan brother, who is himself a harbinger of violence. She's also, as Atkinson allows somewhere in this book, "a force of nature."

To Reggie's lament, in her near-cheerful Scots

To Reggie's lament, in her vibrant false-cheerful Scots lingo, Jackson Brodie stroutly replies, "I'm not." That's largely because when Brodie was flattened by a literal train-wreck, Reggie in her juvenile do-the-right-thing innocence, went searching through the victims until she found someone able to benefit from her resuscitation.

But their voices. Brodie is a common man of the North, but his soldier-policeman-PI straight-forward man of duty appropriation of the common tongue is laced with a streak of self-questioning a railway wide and ornamented with a collection of verses he was forced to memorize in an oppressive working-class childhood by his teachers.

Louise

Dr. xxx.

We all wish to die in bed with our loved ones around us -- or something like that -- and we all know that it doesn't necessarily happen that way for everyone.

Ah, the British voice. They sure know how to speak the language.

Actually, of course there are a lot of languages spoken over there on the other side of the pond that all go by the name of "English."

The characters in Kate Atkinson's novels speak most of them.

I'm thinking the book that I just finished -- I can;t say 'reading' -- but hearing on a set of a dozen discs may be the best exemplar of this highly enjoyable quality in her writing. The book ( 'When Will there Be Good News?") is a read by a British actor -- I don't have his name here -- able to slip from one lingo, tonality, patois, regional or national intonation to the next without any audible stress or strain. Maybe everything is simply funnier or more apt when you're hearing the words the way they are supposed to be spoken.

What makes for brilliant characters in a work of fiction?

Is it that they have their own voice?

Listening to this book read to me as I drove the car, rather freqyently inventing a reason to hop into the car purely for the pleasure of hearing it, I would welocme the turn of the narrative from one central character to another and thoink, oh good, we're back to so-and-so. After a while it occurred to me that I was thrilled to return to the tgrials and tribuations of each of these characters. It was like getting the latest update from a half a dozen great storytellers -- every day!

ATkinson is a purveyor of what I'm starting to call "ensemble fiction." Her books don't have a 'main character.' They have a clutch (what Vonnegut called a karass?) of main characters, each the hero of his or her own story, predicament, crisis, point of view on life, adnd 'voice.' Inevitably these characters cross paths, but seldom in predictable ways. We wait for these intersections; we don't always see them coming.

These crossings dopn't necessarily resolve the action, solve the problem, etc., but they intensify it. And not all the problems are resolved. Our lonely male private detective goes on being a lonely detective. Our obsessed female police detective anticipaes leaveing her perfect husband, but it doesnt happen here -- maybe in some other fictional universe (i.e. another book).

"Good News" begins with the starkest of beginnings, a normal family (mother and three young children) is murdered by a deranged stranger on a lonely country road -- except for "the one who gets away." She'll always be 'the one who got away,' the narrator tells us.

We live in the era of crime stories. In fiction, both pulp and high-toned, in film, press reportage, daily news flashes on TV, and the countless dramatic series we all watch on networks or Netflix. Truman Capote's ground-breaking study of the hideous criminal act of violence randomly visited on 'ordinary people' -- a daring literary choice 50 years ago -- seems a humdrum choice of subject today.

It's hard for me to think of top-drawer literary fiction writers routinely choosing to write "crime fiction," as Atkinson does, until I realize that crime fiction, an outgrowth of the traditional 'mystery' or 'detective story' genres is increasingly the method of choice for exploring normal, everyday life for ordinary people in contemporary society.

Atkinson's fascination with survivors of terrible, random-seeming tragedies possibly mirrors the return of the ancient conundrum of fate. How do the survivors deal with it? How do any of us deal with the fact that somebody else 'gets it,' while we walk away unharmed. It's metaphysical rubber-necking.

"Everybody's dead," laments Reggie, sixteen, Scottish, alone in the world aside from her hooligan brother, who is himself a harbinger of violence. She's also, as Atkinson allows somewhere in this book, "a force of nature."

To Reggie's lament, in her near-cheerful Scots

To Reggie's lament, in her vibrant false-cheerful Scots lingo, Jackson Brodie stroutly replies, "I'm not." That's largely because when Brodie was flattened by a literal train-wreck, Reggie in her juvenile do-the-right-thing innocence, went searching through the victims until she found someone able to benefit from her resuscitation.

But their voices. Brodie is a common man of the North, but his soldier-policeman-PI straight-forward man of duty appropriation of the common tongue is laced with a streak of self-questioning a railway wide and ornamented with a collection of verses he was forced to memorize in an oppressive working-class childhood by his teachers.

Louise

Dr. xxx.

We all wish to die in bed with our loved ones around us -- or something like that -- and we all know that it doesn't necessarily happen that way for everyone.

Published on July 16, 2016 20:50

July 13, 2016

The Garden of Verse: Songs of an Ancient Land With a Strong Pulse

My poems about Greece are up on Verse-Virtual.com, the online journal that publishes a big batch of new poems every month. Greece is both a country with an ancient civilization and, judging by our recent visit, a population that refuses to grow old. Hence the phenomenon of bearded, well-fleshed motorcyclists that we encountered on busy thoroughfares throughout the country. It's not just "Ancient Greece" we encounter on our visit, but a very lively contemporary society. The prevalence of active graybeards on bikes put me in mind of a famous fist line from one of W. B. Yeats's most celebrated poems: "This is no country for old men." This sentence is probably best known today as the title of a film by the Coen brothers that won a best picture Oscar in 2007. That film was based on a novel by Cormac McCarthy, who of course borrowed from Yeats's poem for his title. The poem we're all borrowing from is "Sailing to Byzantium." a work gleaming with brilliant, enduring phrases. The poet's notion of old men is represented this way in the second stanza:

My poems about Greece are up on Verse-Virtual.com, the online journal that publishes a big batch of new poems every month. Greece is both a country with an ancient civilization and, judging by our recent visit, a population that refuses to grow old. Hence the phenomenon of bearded, well-fleshed motorcyclists that we encountered on busy thoroughfares throughout the country. It's not just "Ancient Greece" we encounter on our visit, but a very lively contemporary society. The prevalence of active graybeards on bikes put me in mind of a famous fist line from one of W. B. Yeats's most celebrated poems: "This is no country for old men." This sentence is probably best known today as the title of a film by the Coen brothers that won a best picture Oscar in 2007. That film was based on a novel by Cormac McCarthy, who of course borrowed from Yeats's poem for his title. The poem we're all borrowing from is "Sailing to Byzantium." a work gleaming with brilliant, enduring phrases. The poet's notion of old men is represented this way in the second stanza: An aged man is but a paltry thing, A tattered coat upon a stick, unless Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing For every tatter in its mortal dress,...

Wow. Both great language and good advice. I can testify that in our recent visit to Greece, despite the country's serious economic woes in recent years, we saw no one resembling "a tattered coat upon a stick." Maybe that description befits the European Union in the wake of England's withdrawal vote. But, again, we saw few signs of senescence amid the perfect weather, perfect light, and pale blue and turquoise-green water surrounding the shores like a benediction from a better behaved god than any appearing in the tales of the ancient Olympians. Or in the courteous and capable people we met there. Greece may no longer be the center of the Western world, but tourists can visit the site where they once thought that center both originated and held: the world navel at Delphi. Byzantium, of course, is Greece, as it once was -- not the Hellenic Golden Age Greece that produced the Acropolis, democracy, theater, and the notion of applying reason to investigate natural phenomena. But Greece in the first millennium of the Christian era. When the Roman emperor Constantine, who embraced Christianity as the empire's official religion, decided to escape the barbarian threat by heading east, he chose Byzantium to build his new capital, which he called Constantinople, and which the world now knows as Istanbul. Istanbul today is the capital of Turkey, but for a thousand years it was the capital of a Greek-speaking empire and the center of the Orthodox Christian religion, worshiped in Greek.The arts and thought of that Byzantine civilization, its gold work, jewelry, tiled mosaics, sought after immortal forms and timeless truths. These are what the mind of the "old man" of the poem's first line longs for: "gather me [the poem's speaker asks from Byzantium] Into the artifice of eternity." There's a lot more to "Sailing to Byzantium," a densely beautiful construct of four stanzas of eight lines each, including the poem's insuperable characterization of mortal time itself, when the speaker compares himself to a bird who would sing "Of what is past, or passing, or to come." You really cannot write a better line that sings itself. And after all this necessary homage to Yeats, my appropriation of his poem's famous first line to a poem of five lines seems a very slight affair, which it is. It's a poor thing, but my own. Nevertheless, it sums up my salute to Greece's vitality. Modern Greece is not Byzantium, where the goldsmiths labor to "keep a drowsy emperor awake." In fact it's full of life.

Old Men

After watching bearded, pony-tailed, pot-bellied motorcyclists dart into mid-morning Athens traffic,

I think of Yeats' verdict on Ireland, "This is no country for old men."

They should come to Greece.

(Here's a link: http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-k...)

Published on July 13, 2016 22:21

July 9, 2016

The Garden of July: Perennials Stand Tall

It's time for our mid-summer perennials to lift up their banners and show their colors.

It's time for our mid-summer perennials to lift up their banners and show their colors. I generally think of this time of year as daylily season. The native orange-blossoming daylily (top photo) is strong, reliable, spreads, makes babies and are so common along country roads they're called "ditch lilies." They stand behind most of my photos of July, backing up whatever else I decide to focus on.

What are those those blue-bell shaped flowers (second photo down) called that grow almost everywhere? I never knew their name and I don't remember planting them, but they grow almost persistently as daylilies, including in place (such as graveled surfaces) where almost else does. And they last for weeks.

What are those those blue-bell shaped flowers (second photo down) called that grow almost everywhere? I never knew their name and I don't remember planting them, but they grow almost persistently as daylilies, including in place (such as graveled surfaces) where almost else does. And they last for weeks.  The third photo down puts the white-flowering Astilbe in the foreground and the red-flowering Coreopsis in the back. The red Coreopsis are placed in the foreground in the fourth photo down. You can see their yellow centers. Yellow is the more common flower color for this plant, but the red color in this variety is strong and provides a good contrast to all the green foliage and and yellow blossoms.

The third photo down puts the white-flowering Astilbe in the foreground and the red-flowering Coreopsis in the back. The red Coreopsis are placed in the foreground in the fourth photo down. You can see their yellow centers. Yellow is the more common flower color for this plant, but the red color in this variety is strong and provides a good contrast to all the green foliage and and yellow blossoms. Rose Campion, dark-pink blossoms against gray foliage are pictured next. The background is Lady's Mantle, with its milky yellow foliage.

The plant with dark purple-brown leaves and yellow flowers is called yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris). It grows aggressively. I love the contrast of its dark foliage to all the lighter shades of summer, but it's facing a major thinning this year before it "out competes" all its neighbors into non-existence.

The plant with dark purple-brown leaves and yellow flowers is called yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris). It grows aggressively. I love the contrast of its dark foliage to all the lighter shades of summer, but it's facing a major thinning this year before it "out competes" all its neighbors into non-existence.  The next photo down places the yellow loosestrife against the orange daylilies. Then more daylilies, seen from a perspective parallel to the back garden fence.

The next photo down places the yellow loosestrife against the orange daylilies. Then more daylilies, seen from a perspective parallel to the back garden fence. The second to last photo focuses on a different variety of daylily, the Stella d'Oro (Star of Gold). This plant grows only half as tall as the other daylilies, so its buttery yellow flowers appear proportionately larger.

The last photo down places the white Shasta daisies in front of some big red blossoms. The Shasta daisies growing in various gatherings in the front and side gardens. Here they set off the brilliant deep red of a hibiscus called the Mandeville Rose, an annual.

One of the many qualities I like about the month of July: It fills up your eyes.

One of the many qualities I like about the month of July: It fills up your eyes.

Published on July 09, 2016 22:29

July 7, 2016

The Garden of Verse: A Poet's Brain, A Starving Child, the Universal Longing for a Really Big Hit

Among the many notable poems in July's Verse-Virtual John Allman's urbane postmortem on a bizarre historical-poetic footnote, "On the Removal of Whitman's Brain," tapped me on the shoulder and commanded attention. According to Allman's note on his poem, "During the attempt to remove Whitman’s brain for storage in a jar," somebody dropped the goods: "it must have rolled

Among the many notable poems in July's Verse-Virtual John Allman's urbane postmortem on a bizarre historical-poetic footnote, "On the Removal of Whitman's Brain," tapped me on the shoulder and commanded attention. According to Allman's note on his poem, "During the attempt to remove Whitman’s brain for storage in a jar," somebody dropped the goods: "it must have rolledwhen it hit the floor...it must have formed like a

flower about its clipped medulla, gone flatas a nebula seen edge-on.."

I'm not sure why Whitman's brain was being removed to put in a jar, but they did things like that back then. The poem's allusions to Whitman's oeuvre and its Whitmanic reaching for big images and exalted ideas made me long to hear more. The poem's stylish language, phrases such as "his hump

of metric custard measured by trembling fingers,"

heighten the effect, like a filter passed over a photographic image.

In Sharon Auberle's affecting poem on the death of a friend, "On the Last Leaf Falling from the Gingko Tree," the leaf becomes an emblem of life, of life's last transformation, and an image of its endurance. These wonderful words for that transformation,"that day I didn't see how for just a moment

you turned into light..."

precede the poem's unsentimental but satisfying conclusion. I won't quote it here but you can find it at http://www.verse-virtual.com/sharon-a...

The poem that totally knocks me out is Robert Wexelblatt's "Last Night's News" with its combination of beautiful writing and terrible message. Three six-line stanzas, including some rhyming couplets and repeating lines, particularly the line "A starving child on the news last night"(with some variants), fit together like a song. It's a poem that both writes about its subject and about the act of making poetry, or any sort of art. Here's an excerpt (though every part of this poem is quotable):

"Someone yanked off her knitted cap so you

could see the brittle hair and, even more,

what hunger does and someone else’s war..."

The craft of the poetry makes a reader feel quite certain that something good has happened. And yet the poem tells us, uncompromisingly, that neither the writing, nor the reading (nor quite possibly even the TV report) will do the starving child, and so many like her, any good.

Among the poems about being young, Kenneth Pobo's "A Tommy James and the Shondells Childhood" will likely stay with me for a good long while. It captures the hopeless yearning of an American adolescence at a particular point in time. I suspect the same thing happens today (in some appropriately contemporary, no doubt digital form) that happened back then, when the poem's speaker followed the progress up the charts of a Tommy James and Shondells' hit.

"Songs

postered my ears while I slept, left

footprints on my eyelids."

Music is different in different decades, and the hip-hopsters who replace Tommy may be equally forgettable over the long run, but young psyches will still be longing for something really big and meaningful to happen. (What will happen, if they're lucky, is time.) Still, the poem's conclusion has the ring of the universal:

"we waited

for the next hit that would change our lives

forever, the one that never came."

Poems, like 'hits,' may not change our lives forever, but they make us feel alive.

Verse-Virtual is certainly alive.

This note comes from editor Firestone Feingberg:

"Statistics from Google Analytics show that for the month of June 2016 V-V had 21,698 page views, 3,092 sessions, and 1,611 unique users."

Published on July 07, 2016 21:33

July 6, 2016

The Garden of History: Memories of Life on Suosso's Lane from "Anarchist Voices"

What kind of person was Bartolomeo Vanzetti? According to the people who knew him, he was kind, courteous (especially to women), loved children; he was a talker, a dreamer ("he should have been a poet," a friend said), a bachelor (the woman in his life would remain his mother), self-educated, a letter-writer, a reader who carried his books with him everywhere, a public speaker at anarchist meetings. My sense of Vanzetti as a human being, the basis for the 'character' I created for him in my novel "Suosso's Lane" was heavily influenced by what I could learn from those who lived with him, and knew him, and in some cases loved him, before the Sacco-Vanzetti case turned him into a public figure. Their recollections of Vanzetti and testimony to his character are found in oral histories and books on the case such as Francis Russell's "Tragedy in Dedham." Chief among those who knew him in Plymouth are the members of the family he lived with, the Brini family of Suosso's Lane in North Plymouth. The richest source for their memories, and for other contemporaries of Vanzetti, is "Anarchist Voices: an Oral History of Anarchism in America," by historian Paul Avrich, published in 1995. The book includes interviews with of the Brini children, Beltrando and Lefevre. They were children when Vanzetti came to live with them, though advanced in age when they were interviewed for Avrich's "Oral History."

What kind of person was Bartolomeo Vanzetti? According to the people who knew him, he was kind, courteous (especially to women), loved children; he was a talker, a dreamer ("he should have been a poet," a friend said), a bachelor (the woman in his life would remain his mother), self-educated, a letter-writer, a reader who carried his books with him everywhere, a public speaker at anarchist meetings. My sense of Vanzetti as a human being, the basis for the 'character' I created for him in my novel "Suosso's Lane" was heavily influenced by what I could learn from those who lived with him, and knew him, and in some cases loved him, before the Sacco-Vanzetti case turned him into a public figure. Their recollections of Vanzetti and testimony to his character are found in oral histories and books on the case such as Francis Russell's "Tragedy in Dedham." Chief among those who knew him in Plymouth are the members of the family he lived with, the Brini family of Suosso's Lane in North Plymouth. The richest source for their memories, and for other contemporaries of Vanzetti, is "Anarchist Voices: an Oral History of Anarchism in America," by historian Paul Avrich, published in 1995. The book includes interviews with of the Brini children, Beltrando and Lefevre. They were children when Vanzetti came to live with them, though advanced in age when they were interviewed for Avrich's "Oral History."Beltrando Brini, who states that Vanzetti regarded him as his "spiritual son," was six years old when Vanzetti came to stay for a night. His parents owned a house and took in wayfarers. "Vanzetti came for a day," Beltrando recalled, "...and stayed for four years."

Here is some more of what Beltrando says in the interview for "Anarchist Voices." Beltrando's father, Vincenzo, worked for the Plymouth Cordage Company, the world's largest ropemaker. His highly demanding job was to take bales of sisal and feed them into a machine. His mother, Alphonsina, worked at Puritan Mills as a "specker," picking out threads from woven textiles. When someone needed a place to stay people would be told "go to the Brinis." "The Italians were despised by the Yankees, who treated them as second-rate citizens," Beltrando states, "as the Negroes were treated in the South." Vanzetti "treated us with love and respect... He loved nature, flowers, the sea with the same unadulterated love." His influence was lifelong, Beltrando states. Vanzetti's talk and actions "established values and virtues that have stayed with me all of my life." Since the boy's bedroom was next to the kitchen he would listen to his father and Vanzetti talked "about what anarchists talked about... the relative merits of syndicalism, individualism and communism. And I can still recall their conversations." Vanzetti had "no love affairs, no women friends," Beltrando states. Also: "He had no sense of money, no interest in it." As for his weaknesses, Vanzetti "believed in the perfectibility of human nature," Beltrando states. "...That was his blind spot." These are a boy's memories. Beltrando was still a young teenager when Vanzetti was taken from him, forever, by the arrest that began the famous case and his long imprisonment. An adult may have remembered him differently, but it's my experience that how people behave toward children tells us a lot about them -- about their heart and, as Beltrando says, their "values." Beltrando's older sister, Lefevre (called Faye) has an even more idealized image of Vanzetti, whom she "loved" like a family member: "To know him was to love him."

Some memories of his role in the life of the household: Vanzetti would take the children "to gather mayflowers and violets, blackberries and raspberries." They "picked up coal on the railroad tracks." Even the neighbors, "devout, conservative" people, thought well of Vanzetti.

When government agents came to the Brini house to see a letter Vanzetti had sent them from Mexico, Faye hid it from them, knowing that the agents did not mean him well even though it was only afterwards that she learned that Vanzetti had gone to Mexico "to escape the draft."

She loved him, Faye tells her interviewer, and missed his presence in her household once he was gone.

"I missed him, making his bed and taking care of his clothes...He was so gentle, so good. He helped people, not hurt them."

She also shared her feelings about the famous trial in which she testified for the defense. "I hated Katzmann [the prosecutor]. He bullied me." She recalls that she was at home on the day of the Braintree crime (April 15, 1920) because her mother was convalescing after an operation. That was how she met the salesman Rosen whom Vanzetti brought to the house to speak to Alphonsina, his cloth expert.

"It was a Friday. And Vanzetti had fish for us that day."

Lefevre's memories of being bullied in the courtroom by the aggressive Katzmann make their way into my treatment of the Sacco-Vanzetti trial in "Suosso's Lane." So does Vanzetti's sharing of his love of nature with the children, his neglect of money, his generosity even to those he did not know well, his escorting of the children to the Cordage Workers' Library to share his love of learning. The day Vanzetti arrives at the Brini home on Suosso's Lane, the newcomer pays a kind attention to a distraught little boy in a scene I have wholly invented.

Invented, yes, but in the spirit of Beltrando and Lefevre's memories of a gentle, compassionate soul who loved people and believed the world could be a better place. That's how stories happen. They grow from clues that lead the way to some essential truth, like bread crumbs dropped by children.

Published on July 06, 2016 20:28