Robert Knox's Blog, page 37

September 6, 2016

The Garden of the Earth: Waves at Wollaston Beach, Wind at Great Esker

The waters thrash at Wollaston Beach. We park in our usual place. In this, the safest, most pacific of harbors, the water is almost always flat. Little ripples after a strong blow, and occasionally in deepest, raw-throated winter, whitecaps comb the tops of the driving stream. That's peak action for Quincy Bay, a vast southside chamber of Boston Harbor. From here we can see the tip of Boston Light, the country's first lighthouse, only on occasion.

We have just come from a shoreline park in the neighboring town of Weymouth, called Great Esker Park. The strip of parkland lines the shore of estuarial body of water called the Weymouth Back River (photo left). On the other side of the river lies a complementary riverside park, this one is now contained within the town of Hingham, called Bare Cove Park. Weymouth's park however preserves the distinction of "Esker," the term for the geological formation that distinguishes it from all the other parks in the region, probably the state. The esker is defined as "a serpentine ridge of gravelly and sandy drift, believed to have been formed by streams under or in glacial ice." The "great Esker" of the park was formed 12,000 years ago. In geological time, that's only yesterday. But keep in mind that all of human civilization dates from the retreat of the glaciers in the last (or most recent) ice age. In Great Esker Park, the ridge winds around (and close along) the banks of the Back River facing generally south, and shortly encountering an open-water marsh on its north side. Here you can walk on a scrubby ridge-top trail -- yellow-brown, dirt-dry and sandy underfoot, trailside chest-high scrub oaks forming their acorns -- encountering neighbors such as the women walking and training their identical black labs. A young mother loping along after her preschooler through the thin trees toward the river bank. Three, and then four, identically dressed teenaged boys in black T's and jeans hanging out on the pavement, trying to talk away the September holiday afternoon with gaps of self-conscious silence rolling in, as they will. We were one of them. We roll past like an invisible cloud of silence through their anchored midst, since no one dares voice a word when an old person is within hearing. Potential "fox patches" everywhere (the vernacular pronunciation, that is, of 'faux pas.') I feel we could begin a network TV 'limited series' right there. Our America: everyone comes from a 'non-traditional' family unit. Single parent. Single parent of either sex, plus parent's boy or girl friend. Mom, Mom's mom, and baby. Maybe baby is now adolescent. People who raise dogs lovingly, lavish love on them, like children.

We have just come from a shoreline park in the neighboring town of Weymouth, called Great Esker Park. The strip of parkland lines the shore of estuarial body of water called the Weymouth Back River (photo left). On the other side of the river lies a complementary riverside park, this one is now contained within the town of Hingham, called Bare Cove Park. Weymouth's park however preserves the distinction of "Esker," the term for the geological formation that distinguishes it from all the other parks in the region, probably the state. The esker is defined as "a serpentine ridge of gravelly and sandy drift, believed to have been formed by streams under or in glacial ice." The "great Esker" of the park was formed 12,000 years ago. In geological time, that's only yesterday. But keep in mind that all of human civilization dates from the retreat of the glaciers in the last (or most recent) ice age. In Great Esker Park, the ridge winds around (and close along) the banks of the Back River facing generally south, and shortly encountering an open-water marsh on its north side. Here you can walk on a scrubby ridge-top trail -- yellow-brown, dirt-dry and sandy underfoot, trailside chest-high scrub oaks forming their acorns -- encountering neighbors such as the women walking and training their identical black labs. A young mother loping along after her preschooler through the thin trees toward the river bank. Three, and then four, identically dressed teenaged boys in black T's and jeans hanging out on the pavement, trying to talk away the September holiday afternoon with gaps of self-conscious silence rolling in, as they will. We were one of them. We roll past like an invisible cloud of silence through their anchored midst, since no one dares voice a word when an old person is within hearing. Potential "fox patches" everywhere (the vernacular pronunciation, that is, of 'faux pas.') I feel we could begin a network TV 'limited series' right there. Our America: everyone comes from a 'non-traditional' family unit. Single parent. Single parent of either sex, plus parent's boy or girl friend. Mom, Mom's mom, and baby. Maybe baby is now adolescent. People who raise dogs lovingly, lavish love on them, like children.

Beautiful loving dogs. Troublesome teens. So we walk until we get to the place where the tide from the estuarial river flows over a sandy barrier into the already swelling marsh. It looks like the trail continues up and down on the other side, but you have to walk through the water to get there. The day is cool, gray, excited by stalled tropical storm blow-off, and not exactly wading weather unless you're the hardy types in some other kind of TV show, or desperate like one of Dickens's escaped transportation prisoners. I know I'm not getting my sneakers soaked; I've pretty much passed that stage in life. We engage one of the dog owners. "The tide's high," she tells us, "so you can't get across." Ah yes, we have speculated on that circumstance. We're all very friendly and cheery about reaching this agreement. I think it's the wind, steady and excitable; but not fierce or freezing or uncomfortable, or in any way unpleasant. It pumps up people's moods. And you just have go a little ways inland to escape it. The calendar says it's still summer, it's Labor Day weekend, the traditional end of the easy season. You might still be able to sit outdoors for your picnic. (We have just done so the day before, everybody dressed for summer and feeling it's fall). But it's surely not a "beach day." Confession: the only time I have donned a bathing suit this summer was for an 'early season' June day in Greece, when we splashed about happily in the aqua water. Greece makes you do things that the Massachusetts shoreline (or anywhere else) hardly ever encourages. The nice lady with the black labs tells us that another trail leads to the paved road, where we began our venture and then quickly abandoned for the more adventuresome gallivant up on the ridge trail. The road will take us beyond the marsh where we can pick up the continuing trail along the river. We do all that, passing the black-clad boys, and enter an even more pronounced ridge walk that, I foretell, will go on and on. We take it just a little ways, before running out of adventure fuel. Besides, we have to go see the waves breaking on Wollaston Beach, where the waters thrash against the seawall. It's a rare sight in the reliably (tediously) flat water of Quincy Harbor. We park with our headlights facing the seawall, the punch of the ocean breaking into a thousand stings of chilly spray splashing on the car hoods, flecking with ocean chill our hands and clothes and hats and averted faces. Staining our windshields with the print of the sea.

Beautiful loving dogs. Troublesome teens. So we walk until we get to the place where the tide from the estuarial river flows over a sandy barrier into the already swelling marsh. It looks like the trail continues up and down on the other side, but you have to walk through the water to get there. The day is cool, gray, excited by stalled tropical storm blow-off, and not exactly wading weather unless you're the hardy types in some other kind of TV show, or desperate like one of Dickens's escaped transportation prisoners. I know I'm not getting my sneakers soaked; I've pretty much passed that stage in life. We engage one of the dog owners. "The tide's high," she tells us, "so you can't get across." Ah yes, we have speculated on that circumstance. We're all very friendly and cheery about reaching this agreement. I think it's the wind, steady and excitable; but not fierce or freezing or uncomfortable, or in any way unpleasant. It pumps up people's moods. And you just have go a little ways inland to escape it. The calendar says it's still summer, it's Labor Day weekend, the traditional end of the easy season. You might still be able to sit outdoors for your picnic. (We have just done so the day before, everybody dressed for summer and feeling it's fall). But it's surely not a "beach day." Confession: the only time I have donned a bathing suit this summer was for an 'early season' June day in Greece, when we splashed about happily in the aqua water. Greece makes you do things that the Massachusetts shoreline (or anywhere else) hardly ever encourages. The nice lady with the black labs tells us that another trail leads to the paved road, where we began our venture and then quickly abandoned for the more adventuresome gallivant up on the ridge trail. The road will take us beyond the marsh where we can pick up the continuing trail along the river. We do all that, passing the black-clad boys, and enter an even more pronounced ridge walk that, I foretell, will go on and on. We take it just a little ways, before running out of adventure fuel. Besides, we have to go see the waves breaking on Wollaston Beach, where the waters thrash against the seawall. It's a rare sight in the reliably (tediously) flat water of Quincy Harbor. We park with our headlights facing the seawall, the punch of the ocean breaking into a thousand stings of chilly spray splashing on the car hoods, flecking with ocean chill our hands and clothes and hats and averted faces. Staining our windshields with the print of the sea.

Published on September 06, 2016 21:09

September 5, 2016

Garden of the Seasons: The Pleasures of September

We can use our own judgment to decide whether summer is over. By the definition their industry uses, the meteorological science people claim it is. They divide the seasons by the whole month method, so autumn for them begins on Sept. 1. Summer began its three-month run June 1. Winter begins on Dec. 1. The astronomical calendar, following the movements of the sun more exactly, extends the three-month run of summer out to Sept. 22, when the sun's apogee is directly above the equator.

Whichever season we assign it to, to me the first days of September ring in a change. Now you always hear the crickets at full voice when you venture out at twilight. You get a cool day, and probably a couple of rainy days too at the month's beginning. (Still waiting.) In September I go around the house closing windows first thing after getting out of bed. I work on remembering where I put the long sleeves; the 'wind-breaker'; socks. Wonder why the flip-flops are still hanging around next to the front door. And even though it's been years and years since I've had any personal connection to the academic calendar, I'm certain I still feel a change in the air when the neighborhood turns another page on the calendar. I stand outside my house in the hours before noon and listen hard. What is that sound? Is it silence?

Whichever season we assign it to, to me the first days of September ring in a change. Now you always hear the crickets at full voice when you venture out at twilight. You get a cool day, and probably a couple of rainy days too at the month's beginning. (Still waiting.) In September I go around the house closing windows first thing after getting out of bed. I work on remembering where I put the long sleeves; the 'wind-breaker'; socks. Wonder why the flip-flops are still hanging around next to the front door. And even though it's been years and years since I've had any personal connection to the academic calendar, I'm certain I still feel a change in the air when the neighborhood turns another page on the calendar. I stand outside my house in the hours before noon and listen hard. What is that sound? Is it silence?

Some segment of the neighborhood's population has been significantly emptied. People who live next to schools have a different opinion. The silence has many causes. Landscaping electronics continue this month, but at a reduced frequency. People are motivated to keep their lawns trimmed for 'summer.' After summer vacation, that impulse dwindles. But whether September is really still summer or not, it offers many of the same pleasures we gobble up in the 'vacation month' of August. Our son, who lives in a Midwestern city where the humidity lingers, reminds us when he visits that August is a beautiful time in New England. If you're not a commercial farmer, August is the easiest month of the year to do whatever you please; or nothing, if that's what pleases. Lots of sunlight; but as a rule little humidity. Guess what, September comes right behind it.

Some segment of the neighborhood's population has been significantly emptied. People who live next to schools have a different opinion. The silence has many causes. Landscaping electronics continue this month, but at a reduced frequency. People are motivated to keep their lawns trimmed for 'summer.' After summer vacation, that impulse dwindles. But whether September is really still summer or not, it offers many of the same pleasures we gobble up in the 'vacation month' of August. Our son, who lives in a Midwestern city where the humidity lingers, reminds us when he visits that August is a beautiful time in New England. If you're not a commercial farmer, August is the easiest month of the year to do whatever you please; or nothing, if that's what pleases. Lots of sunlight; but as a rule little humidity. Guess what, September comes right behind it.

Garden lovers have no trouble finding something to keep the flame going. The first weeks of September offers the last happy-go-lucky days for late summer standbys. Sweet William (second photo). Tall phlox (photo at left). Cosmos. Zinnias. Cone flowers and Rudbeckia (both seen in third photo down). The morning glory are still climbing. The PG hydrangea (fifth photo), in this year-after last year's rescue-transplant, gives us one beautiful, enduring bloom.

Garden lovers have no trouble finding something to keep the flame going. The first weeks of September offers the last happy-go-lucky days for late summer standbys. Sweet William (second photo). Tall phlox (photo at left). Cosmos. Zinnias. Cone flowers and Rudbeckia (both seen in third photo down). The morning glory are still climbing. The PG hydrangea (fifth photo), in this year-after last year's rescue-transplant, gives us one beautiful, enduring bloom.

The butterfly bush (Buddleia: top photo, with butterfly), during the last two years at least, is peaking. Our red-flowering Coreopsis is on a second bloom (sixth photo). Potted annuals are going great guns. A perennial called "Blue boas," or Agastache, has continued flowering from mid-summer on. The blue balloon flowers has some second blossoms. A few day lilies as well.

The butterfly bush (Buddleia: top photo, with butterfly), during the last two years at least, is peaking. Our red-flowering Coreopsis is on a second bloom (sixth photo). Potted annuals are going great guns. A perennial called "Blue boas," or Agastache, has continued flowering from mid-summer on. The blue balloon flowers has some second blossoms. A few day lilies as well.

With so many plants still flowering, I find satisfaction in cutting back the plants have flowered, done their thing, had their moment in the sun, and now are wilting. Removing some layers of mid-summer lush allows the remaining color peaks to shine. Besides, it's a lot less work than undertaking the significant transplanting I put off every year.September's too good not to enjoy it while it lasts.

With so many plants still flowering, I find satisfaction in cutting back the plants have flowered, done their thing, had their moment in the sun, and now are wilting. Removing some layers of mid-summer lush allows the remaining color peaks to shine. Besides, it's a lot less work than undertaking the significant transplanting I put off every year.September's too good not to enjoy it while it lasts.

Published on September 05, 2016 20:55

September 3, 2016

The Garden of History: From 1927 to 2000

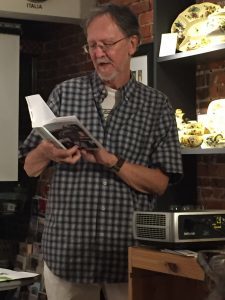

Boston's North End, an Italian-American neighborhood for a hundred years, has an attractive new book store, I AM. The store hosted a program that included long-suppressed film footage of the Sacco-Vanzetti funeral march, a reading from the published letters of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and my presentation on "Suosso's Lane."

Boston's North End, an Italian-American neighborhood for a hundred years, has an attractive new book store, I AM. The store hosted a program that included long-suppressed film footage of the Sacco-Vanzetti funeral march, a reading from the published letters of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and my presentation on "Suosso's Lane."The movie newsreel film footage, taken of the Aug. 27, 1927 funeral march following the unjust executions of the two Italian immigrants, was suppressed by the American government, which told movie distributors to destroy the prints. The funeral march drew an estimated 200,000 people, the largest public gathering in Boston until recent times. The government sought to discourage all future attention to the Sacco-Vanzetti case, which damaged American prestige abroad. In recent years some damaged footage was discovered and restored. Historian Robert D'Attilio showed the footage and commented on the heavy police presence at the start of the march from downtown Boston. An attempt to re-route the march from certain streets failed.

David Rothauser, who produced a film entitled the "The Diary of Sacco and Vanzetti," then read two letters from Nicola Sacco during his imprisonment, including a final letter to his son, Dante. He also read a celebrated statement by Bartolomeo Vanzetti from the last days of his life in which he calls the ordeal of his and Sacco's suffering a "triumph" for educating society on the need for greater justice. The writings of Sacco and Vanzetti remain in publication in a Penguin paperback.

I spoke on, and read a few brief excerpts from, "Suosso's Lane," my novel based on Vanzetti's life in Plymouth, Mass., and the relationship between his times and our own. Here's an excerpt from my talk:

But the world does not end in 1927, with the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. History in America, as everywhere else, goes on.

In my novel "Suosso's Lane," the details of the case are seen and discussed from perspective in the year 2000. We are in a new millennium when a young couple moves into a certain house on Suosso's Lane because the rent is manageable and the husband has his first real college teaching job close by. My characters discover that North Plymouth still has some of the characteristics of its working-class immigrant origins -- more affordable housing there than in most regional communities, more working class families and working poor. My young academic (I name him Mill Becker), a history teacher who has yet to find his true subject, learns to his surprise that a key figure in an internationally famous case in which the bigotry and the shortcomings of American justice scandalized the world, lived in apple-pie, Thanksgiving story, squeaky-WASP Plymouth at the time of his arrest.

Mill's interest is piqued. He looks for people to talk to. He looks into the historical conditions that produced the infamously flawed and prejudiced trial that convicted two men of murder without substantive evidence, but because of their political beliefs, the national mood of fear of radical violence or Communist revolution, and because of a widely held prejudice of the time against people of their national origin. To get an idea of how 'typical' native-born American regarded them, for 'Italians' substitute Muslims, Mexican criminals, or 'illegals' in today's partisan political discourse. In the course of his research Mill also discovers the existence of pre-World War I America, a time in history when lectures on free love by the anarchist Emma Goldman were widely attended throughout America, when almost a million votes were cast for the Prairie Socialist Eugene V. Debs (in the presidential election of 1912), when the ruling class faced challenges from both left and center, from the anarchist guru Luigi Galleani and the anti-monopolist Theodore Roosevelt; when an array of left-wing movements and theories (and some right-wing ones) challenged the status quo, ranging from the Farmer-Worker parties in Minnesota and other states, to the racist Jim Crow movement of the former Confederacy. Also a time when other major issues and causes were passionately debated: women's suffrage. Temperance, an idea that addressed the symptoms of poverty but not the cause. (Think "drugs," and substitute 'the evil of drink.') It led to Prohibition.

It's a period of American life that that our own times appear to have largely forgotten, a time of relatively unfettered radical agitation that came to an end with the Red Scare.

Published on September 03, 2016 20:43

September 1, 2016

Garden of Verse: Two Poems from Lebanon

Two poems published last month in Verse-Virtual.com date from our recent, early summer visit to Lebanon. Both have their origin in our persistent wanderings in Beirut, both a magical and a very real city. Over a dozen years we've seen the evidence of the damage from the city's war years diminish, the luxury hotel towers go up, and, more recently, a growing concern that the traditional architecture of the Arab Mediterranean city -- Arab style houses, Ottoman buildings: ornate balconies, iron gates, tall windows, open stairwells, courtyards, rooftop gardens -- is giving way to new buildings that lack the charm but raise the rent. It's easier and more profitable to build a new building with modern infrastructure than preserve and restore the beauty of the old. Western cities have been fighting this battle for years. Now it comes to old cities in developing countries that attract investment. Anne and I have been taking walks on our own in Beirut on the last few visits. Given Smartphone technology we're probably past the point of having to stop high school kids who study English to ask for directions back to our daughter's neighborhood. Probably; hopefully. Plenty of the old is still around. Wood and stone have long memories. Some moments find you and stop you cold. No one has found a reason yet to knock down a piece of wooden wall in the photo above. Here's the poem:

Two poems published last month in Verse-Virtual.com date from our recent, early summer visit to Lebanon. Both have their origin in our persistent wanderings in Beirut, both a magical and a very real city. Over a dozen years we've seen the evidence of the damage from the city's war years diminish, the luxury hotel towers go up, and, more recently, a growing concern that the traditional architecture of the Arab Mediterranean city -- Arab style houses, Ottoman buildings: ornate balconies, iron gates, tall windows, open stairwells, courtyards, rooftop gardens -- is giving way to new buildings that lack the charm but raise the rent. It's easier and more profitable to build a new building with modern infrastructure than preserve and restore the beauty of the old. Western cities have been fighting this battle for years. Now it comes to old cities in developing countries that attract investment. Anne and I have been taking walks on our own in Beirut on the last few visits. Given Smartphone technology we're probably past the point of having to stop high school kids who study English to ask for directions back to our daughter's neighborhood. Probably; hopefully. Plenty of the old is still around. Wood and stone have long memories. Some moments find you and stop you cold. No one has found a reason yet to knock down a piece of wooden wall in the photo above. Here's the poem: Old Wooden Doors

(after a photo taken on a side street in Beirut)

What faces do we see

in the bone mirrors of long-ago trees?

A long-closed portal

to an unknowable life,

lost decades before like the city that was,

hidden beneath the mask

of an ancient plague called simply "the war."

No war now.

Merely the routine clamor

of the mind-fogging traffic.

This wall of doors has taken the veil

Patient as the ages, it watched a city crumble,

reclaim its pieces

burred with time like furred candy,

make up its face again

smile and grimace in the lightweight days of not yet summer,

a day that lets the caged bird sing

from the balcony.

Two years ago on a previous visit we were surprised to find women sitting on the sidewalks of a busy commercial district begging, with their children beside them. Well, of course, after three years of devastating civil war an estimated one million Syrian refugees were trying to survive in neighboring Lebanon, a country the size of Connecticut with its one big city. What did I expect? I wrote a poem called "Sidewalk Madonnas," that was published in a few places, and a commentary that the Globe put on its digital edition. Unhappily, poems don't stop humanitarian disasters. Last summer, two more cataclysmic years later, things are that much worse for the war's displaced persons. You can no longer hand a low-denomination Lebanese Lira note to a black-clad woman and go unmolested on your way. This poem describes that experience.

I Flee Them Now

I flee them now,

the feral beggars of the Syrian Catastrophe,

that fiery execution and slow-burn decomposition of a nation

in which the New World Order

dumbly colludes, rubbing its two-faced chin

Why should they not run me down,

strip me of value, market my flesh and bones,

render my trace elements useful in the end?

I do no good for them now

my tongue dumb, my outrage numb,

my well-intended prayers for peace of no account

when what's required is salvation on-the-ground

Robbed of their childhood,

denuded of home, country, kinship, future,

stranded in a world of strangers,

why not fling their hungers at the impotent bystanders

whose bellies are full,

whose tongues fail to shake the palaces of power

whose fortunate existences mock their stolen lives?

I have no country to give them.

(These poems and many others can be found at Verse-Virtual.com. Here's a direct link:

http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-k... )

Published on September 01, 2016 21:46

August 28, 2016

The Garden of History: Eighty-nine Years After the Executions

Last week's annual commemoration of the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti -- for being anarchists, Italians, for being in the wrong place when the state wanted to make an arrest; for having their names on a government list of subversives -- seems to me a good occasion for looking backward, and forward, and all around us today for important social and political currents in American society. Today many Americans are saying that America is changing too fast. And that people who were born here, who’ve lived here all their lives, who believe that they "built this country," are being left behind. Jobs are being shipped overseas, the industries that made their communities prosperous are drying up. In some parts of our country cities and towns are turning into ghost towns. People like “us” (and when Americans say "us" they most often mean native-born white people) aren’t doing better than previous generations, they’re doing worse, and in some cases they're barely hanging on economically to their place in the social ladder. They’re looking for somebody to blame for their declining circumstances. There are some obvious candidates, such as (number one) corporate wealth and domination of government. And, two, closely related, the increasingly steep gap between the super-rich and everybody else. Instead, however,we're seeing the rise of demagoguery as a major party candidate seeks to scapegoat immigrants, religious minorities, and nationals from certain countries who seek work and opportunity in the US, some of them without papers. That's today. But what were things like back in Bartolomeo Vanzetti's day? Vanzetti came to America in 1908. It was not an unusual choice. Between 1880 and 1920 an estimated 4 million Italians entered the US; many other immigrants, mostly from southern and eastern Europe, came to the US at the same time. Vanzetti left his home in the Piemonte region after the death of his beloved mother; and after nearly dying himself from the effects of over-work in the unhealthy atmosphere of pastry-making factories. What did Vanzetti find in the America, the new world, the land of freedom and opportunity. He found many poor, exploited laboring people. And a few very rich who owned most everything and dominated a government that had no interest in improving the lives of ordinary people. The material well-being of ordinary Americans was not a subject government need concern itself with.

Like many others who arrived here without family or friends in this country, Vanzetti found a place at the bottom rungs of the social ladder. He worked at the laboring jobs typically available to immigrants in NYC and surrounding areas for several years, sometimes sleeping in doorways.

When I began thinking about writing a book about Vanzetti's life in America, I asked myself what kind of man was Vanzetti? Here are some of my answers.

An exploited child laborer – sent off by his father at age 13 to work in factories as an apprentice pastry maker. A man who loved children, who regarded himself according to Beltrando Brini, a child of five when Vanzetti became a boarder in his family's household, as his "spiritual father." A man who exhibited great kindness and courtesy to women. A man for whom the model human being, the most important person in his life, was his mother, the woman who nursed him back to health when he was sent home from a factory with a lung disease, pleurisy, from which he was not expected to recover.

And yet this man does not marry, does not court. As Beltrando Brini insisted many years later in a book of oral histories: "Vanzetti did not have affairs." And a man who despite his radical political beliefs was widely respected within a community of socially conservative people, more likely (as daughter Lefevre Brini recalled in the same book) to be observant Catholics than anarchists.

Yet this is the man who, with his fellow anarchist Nicola Sacco, was charged with the cold-blooded murder of two factory payroll officials in the course of robbing a payroll that the families of hundreds of shoe factory workers depended on. They were convicted by a so-called jury of their peers -- all white men of old New England stock, Protestants, old-fashioned views. A jury systematically purged of any members who were critical of the government, admitted they read books, or in any way struck the prosecution as too "intellectual." People who read books might be sympathetic to some of the criticisms of society made by anarchists.

As Vanzetti would say to the court before his sentencing. "I am suffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical; I have suffered because I was an Italian, and indeed I am an Italian..."

Why was being an Italian held against him? Because in an era of heightened fears of social disorder, crime, and unemployment, ordinary unsophisticated Americans had been taught by their leaders, by newspapers, and by the same ownership class that benefited from cheap immigrant labor that Italians belonged to an inferior "race" that could never be trusted to understand democracy or become good citizens. President Calvin Coolidge said as much when he signed a law sharply curtailing immigration from Italy.

Laughable, ridiculous -- shameful! -- to recall that Americans could believe such scurrilous nonsense.

But they did. And what does this past say about the future? When we hear whole classes of people -- whole nationalities and religious faiths -- denounced as dangers to our national well being. Called threats to our security, criminals, drug traffickers.

Might not similar injustices take place in the American future envisioned by the demagogues who seek votes and power by the same old appeal to the lowest emotions -- racial stereotyping, scapegoating, what today we call "profiling"?

In my novel "Suosso's Lane," a young academic, a history teacher who has yet to find his true subject, moves to North Plymouth, to the street where Bartolomeo Vanzetti found lodging with the Brini family.... and learns to his surprise that a key figure in an internationally famous case in which the bigotry and the shortcomings in American justice scandalized the world, was living in apple-pie, Thanksgiving story, squeaky-WASP Plymouth at the time of his arrest. His story, the internationally infamous Sacco-Vanzetti case, the trial of the century, is a telling chapter in national history that Massachusetts and, I would say, American society as a whole, chose to forget. Why? How?

My answer is that the Plutocracy, and the political establishment it controlled, changed the story. The threat to justice and security came not from the abuses and inherent flaws of monopoly capitalism, but from an outside power: international Communism, the Soviet Union, Red China. Just as laws passed during WWI banned criticism of America's participation of the war, the draft; then banned Anarchist literature, or being an anarchist. Or a "radical' such as Vanzetti confessed himself to be in his final speech before the court.

Wealth and power told the nation to forget. The nation complied.

"Suosso's Lane" tells an old story, but also a new immigrant story about a man from Africa who asks himself whether he should go on working for a big-box retailer (situated where Plymouth Cordage factory building once stood), a job he hates, or join the sub-rosa effort to organize a union of retail workers. If he gets caught, he'll be fired; he may be deported.

And my young historian, after studying the forgotten period of the Sacco-Vanzetti case, concludes that America was in some respects a better and more hopeful place way back then, when ordinary Americans were free to talk about, study, and attend lectures or meetings that offered fundamental critiques of the American system -- its inherently anti-democratic, anti-egalitarian capitalist economic system, paired with its theoretically open free-election system of choosing leaders. Before the American corporate and political establishment succeeded in demonizing the left.

Published on August 28, 2016 22:00

August 25, 2016

The Garden of the Seasons: Late Summer in Berkshire County

One thing that western Massachusetts has a lot of, that we don't have so much of in the eastern part of the state, is space. And when that space is covered by hills and trees and bodies of inland water and lots of green growing organic life, the result can be very attractive. When we go to the Berkshires we tend to do a lot of walking among the green stuff. Many walking paths thread through the region's forests; many thousands of acres to walk through, many views -- looking up, or looking down -- and many little local mini-ecosystems along the way to keep the experience fresh. We have favorite walks that we have traveled time again. But just as the Zen aphorism tells us you cannot step into the same river twice, you can't walk the same trail either. It's always different; or maybe we are. That's probably the point. The Beartown State Forest, the state of Massachusetts tells us, offers an extensive trail network ranging over 15,000 acres. I don't think we've seen a high percentage acres. We mostly stick to what the state's Department of Conservation and Recreation describes as the "1.5 mile Benedict Pond Loop Trail, a must in any season."

We did the loop last week. A ranger took our seven dollar parking fee and advised us that a sign near a bench at scenic point on the lakefront warns people to stay away from the beehive. We found the bench, but saw no bees. Plenty of dragon flies however cruised and darted over the lake surface, including some brightly colored red ones. A number of them had paired up and were clearly quite attached to each other as they cruised about. One of them, still stag, took a breather on my shirt (see second photo) working up the energy to get back into the game.

We did the loop last week. A ranger took our seven dollar parking fee and advised us that a sign near a bench at scenic point on the lakefront warns people to stay away from the beehive. We found the bench, but saw no bees. Plenty of dragon flies however cruised and darted over the lake surface, including some brightly colored red ones. A number of them had paired up and were clearly quite attached to each other as they cruised about. One of them, still stag, took a breather on my shirt (see second photo) working up the energy to get back into the game.

We saw evidence of beaver activity, some very gnawed trees, still standing but chewed down to about fifty percent of their diameter at the bite area before, it appeared, the creatures gave up. We saw a beaver lodge built on the lake quite close to the shore. I was puzzled by the location: no place to do any damming and probably too close to the human presence along the trail to be comfortable. Maybe that's why the lodge seemed abandoned.

We saw evidence of beaver activity, some very gnawed trees, still standing but chewed down to about fifty percent of their diameter at the bite area before, it appeared, the creatures gave up. We saw a beaver lodge built on the lake quite close to the shore. I was puzzled by the location: no place to do any damming and probably too close to the human presence along the trail to be comfortable. Maybe that's why the lodge seemed abandoned.

We saw a covey of ducks landing with the huge heavy splash and glide that reminds one of a of seaplane landing. Heard occasional bird cries above in the trees, and spied the silhouette of a turtle sunning on a log far out on the pond on the surface of a log (third photo). Some fish came close to the shore to loiter beneath logs in the bronze or brownish water. But the most beautiful natural sight was probably the lake surface itself, as it reflected the high clouds and blue sky in a beautiful late summer New England day (top photo).

We saw a covey of ducks landing with the huge heavy splash and glide that reminds one of a of seaplane landing. Heard occasional bird cries above in the trees, and spied the silhouette of a turtle sunning on a log far out on the pond on the surface of a log (third photo). Some fish came close to the shore to loiter beneath logs in the bronze or brownish water. But the most beautiful natural sight was probably the lake surface itself, as it reflected the high clouds and blue sky in a beautiful late summer New England day (top photo).

We also saw interesting views in the Tyringham Cobble (photos above and at left), a site the Trustees of Reservations (its owner) describes as "one of the few places in New England where you can stand on a major thrust fault." The cobble, a word for a stony formation, is part of one of the oldest geologic formations in New England. The Trustees use words such as "Ordovician marble rocks" and "Precambrian gneisses" to describe its make-up, terms that translate approximately to "really, really old."

We also saw interesting views in the Tyringham Cobble (photos above and at left), a site the Trustees of Reservations (its owner) describes as "one of the few places in New England where you can stand on a major thrust fault." The cobble, a word for a stony formation, is part of one of the oldest geologic formations in New England. The Trustees use words such as "Ordovician marble rocks" and "Precambrian gneisses" to describe its make-up, terms that translate approximately to "really, really old."

We revisited an incredibly time-sculpted rock whose profile has earned it the name "Rabbit Rock." We call it "Fiver," after one of the principal characters in a family favorite childhood (and adult) fantasy book, "Watership Down." You can tell that we think revisiting a loved site is a lot like visiting an old friend. Especially when you have names for the rocks.

We revisited an incredibly time-sculpted rock whose profile has earned it the name "Rabbit Rock." We call it "Fiver," after one of the principal characters in a family favorite childhood (and adult) fantasy book, "Watership Down." You can tell that we think revisiting a loved site is a lot like visiting an old friend. Especially when you have names for the rocks.

Published on August 25, 2016 20:40

August 24, 2016

Gardens of Verse: Poems about Unspeakable Subjects

I had a professor, and a very good one, who once spoke about "the poetry of the ineffable."

I had a professor, and a very good one, who once spoke about "the poetry of the ineffable."That's a word for what's all around us but cannot be easily named or defined, if at all.

Common as the air we breathe, but just as hard to see. The feeling of being home again after a period away. Recognizing a voice on the telephone before a single word is understood. The last dribbly bits of consciousness before we sleep. The little twitch of nerves that tells you it's time to get up. Life, love, the universe.

The ineffable, by its standard definition, means "incapable of being expressed or described in words."

And yet here they are, poets -- going at it in the August edition of Verse-Virtual. (http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...)

You can say it's part of the job.

Tom Montag's poem "Speak, Tree" brings me right up against the moment when I stare at a tree, or a line of them, against a blue sky, something I do a lot, particularly in summer. Is there a term for this activity? I don't think so. The poem begins:

Speak, tree, of all

you've seen, your whole

life holding sky.

I've never thought of that relationship ("holding sky") between trees and sky, in quite that way. And when we contemplate trees against sky are we doing what this poem suggests: asking the tree to share its wisdom with us? There's no common word or expression for that relationship, either. But now we have a poem for it.

Tom's poem "In the Margin" also approaches experience for which we do not commonly have words: The gap, or distance, or connection, between "here" and "there," and between "new, now" and "old." How do we get from one to the other? His poem offers us a way to think about the problem (or is the solution?) in its wonderfully concluding phrase: "this leap between.

Penny Harter's poem "Deja Vu" seems to me about an equally unknowable quality, the what-ness of existence, to which the poem keeps throwing lifelines of meaning. In a stanza about "the future," already compared to the "neighboring field" or something waiting "around the next bend," she writes :

What has already happened there wraps itself firmly

around our flesh like a rope hauling a climber up

the slippery scrabble of a nameless mountainside.

The present isn't any easier than the future to grasp in our minds. In what appears to be a related poem about time -- "Just Now," one of those good old ineffables -- the poet depicts some of the sensations of an instant of time as

washing through the wall into a ghostly form

whose half-life I cannot catch in my net.

I don't know how many removes this array of imagery takes us from the 'thing in itself,' but the poem's imagery -- the half-life of a ghostly form washing through a wall -- gives us a good idea of what we're up against when we try to catch hold of the present.

"The Swimmer" by Donna Hilbert is a vividly poetic reminiscence that mingles some enduring mental snapshots of what sounds to me like early adolescence just the way her characters, after swimming in the rich kids' pools, mix experimental sauces for magical ends:

we dipped crackers

in mustard, Worcestershire,

any liquid found in their kitchen

went into our sauce,

an extra-strength potion.

We dipped, ate, were transformed

into amazing girls...

We have no words, certainly no completely rational explanation, for how we change from what we were to what we have become. Perhaps some little bit of what we were survives the transformation.

The problematic idea of time runs through David Graham's poem "Most of the Time We Live Through The Night" -- an intriguing title borrowed from Robert Bly.

Most of the time Sunday has

little to tell Saturday night, and almost nothing

Monday morning needs to hear

A second poem, titled "No Recent Activity," suggests that while 'most of the time' we make it through our nights, we won't make it through all of them. This poem addresses another of these hard to put into words subjects, in large measure because we choose not to talk about i... as Keats did in a poem titled "When I have fears that I may cease to be."

And this poem does to:

It's all air eventually, That's exactly

what we hate and deny every breathing day.

You don't need to stroll the cemetery

to feel earth's friction rub against you.

Great image. Ah, there's the rub.

The submerged subjects in Robert Wexelblatt's "The Entanglers" appear to me to be love, desire and inspiration. The poem's speakers are the mythical Sirens, who at one point complain about the kind of guy too wrapped up his self-involvement to be allured. Some guys you just can’t reach; duty hardens

their souls or music is just a cage to

them or they can’t get into voices that

are nude, cool, humid, smooth, round, inveigling

with words beneath words, sound under sound,

who never go beyond sandy shallows

to the bottom of green forgetfulness.

Possibly, their complaining about a bad lyricist. If these guys can't get into voices that are "nude, cool, humid, smooth, round, inveigling

with words beneath words," I probably wouldn't like their songs either. If "Euterpe" (the title of Wex's second poem) is, as I understand, the muse described as "the giver of delight," I definitely want her around. But, once again, where did the time go? The flow and tacking of the poem's final phrases

...or guess with what

sore regret you would yearn ever after

to behold once more her illegible smile. is a fine cruise brought gracefully to shore.

Published on August 24, 2016 13:15

August 11, 2016

Garden of Seasonal Favorites: 'Twelfth Night' at the Mount

Have you heard you ever heard this favorite quote: “Come and kiss me sweet and twenty/Youth’s a stuff will not endure.”Have you heard “If music be the food of love/Play on…” ?Or: “I will be revenged on the whole pack of you!”Or: “… and the rain it raineth every day.”Or: “'Better a witty fool than a foolish wit" The first of these is from Shakespeare’s comedy “Twelfth Night.” The second is from “Twelfth Night.” And the third, and the fourth, and … you get the picture. Or how about:"Some are born great, some achieve greatness, some have greatness thrust upon them.”Or, possibly my favorite: "Dost thou think that because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?'"

Have you heard you ever heard this favorite quote: “Come and kiss me sweet and twenty/Youth’s a stuff will not endure.”Have you heard “If music be the food of love/Play on…” ?Or: “I will be revenged on the whole pack of you!”Or: “… and the rain it raineth every day.”Or: “'Better a witty fool than a foolish wit" The first of these is from Shakespeare’s comedy “Twelfth Night.” The second is from “Twelfth Night.” And the third, and the fourth, and … you get the picture. Or how about:"Some are born great, some achieve greatness, some have greatness thrust upon them.”Or, possibly my favorite: "Dost thou think that because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?'"All of these are from “Twelfth Night,” possibly the richest of Shakespeare’s romantic comedies. Seeing the play a week ago performed by a troupe from the Teaching Program of Shakespeare & Company outdoors at the Mount, the company’s former haunt, a sylvan setting on the Edith Wharton estate in the Berkshire woods was like paying a visit to an old friend. A particular companionable and witty friend, who has a good story to tell. Even though it’s the same story each time, you never tire of hearing it. Or in this case, of watching it on the stage played by people who love what they're doing. The play is a tale built around a number of Shakespeare’s favorite plot devices. A storm at sea, a case of mistaken identity, twins (justifying the previous as an occasion for comedy), cross-dressing so that the heroine can play a man’s role in her tale, and multiple marriages at the end. Its main characters include classic Elizabethan (and Renaissance) types. A ‘cruel mistress’ who refuses the love of a perfectly adequate suitor. A narcissistic, self-involved royal suitor with a grievance – not far, say, from Hamlet – who has the luck to be situated in comedy rather than tragedy. Orsino has woman troubles, but no one has killed his father or polluted his realm. He holds languorous court in the play’s near opening (many productions skip-wreck at the start), indulging his love-sickness with the command to the court musician to feed his languor: “If music be the food of love, play on.” A few more self-referential observations later he’s tired of it. Enter Caesario, which is to say the shipwrecked Viola, dressed as a slender young man – “I am all the daughters of my father’s house” he/she will say a few scenes later – to whom Orsino takes an immediate liking. A certain amount of guy-affection takes place between them, shoulder slapping and the like, inherently comic under the circumstances and rather slap-sticked in this one. Orsino dispatches Caesario to be his go-between with the Lady Olivia, who's drowning her own self-indulgent neurosis expressed as prolonged grieving for the death of her brother. We take her widow’s weeds and veiled face as signs of her unwillingness, as we would put it today, to ‘engage’ with the world. Like Orsino she has servants to do her living for her. One of these is Malvolio, who will be tricked into believing that he is about to have “greatness thrust upon him.” He does a bit of clichéd thrusting to give the audience the point. Another is Feste, one of Shakespeare’s most appealing clowns (or court fools), who wittily proves that Olivia in her grief-hangover is more “fool” than he is. So you’re still suffering for your brother? he asks; then asserts “I believe he is hell.” “I know he is in heaven!” she retorts angrily. Then surely, the fool replies, there is no reason to grieve for a loved one who is now in a better place.Having scored this unarguable point, Feste triumphantly echoes his lady’s earlier command: “Take away the fool.” The licensed fools of Shakespeare’s courts are the voice of the commoner allowed to needle nobility. The role is an egalitarian gesture to the sentiments of ordinary folk, including the groundlings who paid a penny to watch a play standing below the stage in The Globe. The best bargain in popular entertainment ever offered. The fool, in his role as entertainer, is also a musician. The production we saw by the education program actors, some eight or so players who engineered quick-change acts barely off stage so smoothly it took me a while to realize what was going on, gave Feste a guitar, plugged in a mike, and turned him into a popular entertainer offering pop-song versions of the play’s classic ditties. Shakespeare’s theater encompassed song and dance. Today’s classic revival theater uses the same devices in contemporary ways to engage the senses enliven the action and allow comedy and enchantment to stretch beyond the spoken word. Shakespeare & Company pioneered this approach 30 years ago. For years we saw the fruits of their labors staged on the lawn and wooded backdrop of the grounds of the Mount, taking full advantage of moonlight and darkness to serve as a fairy-land of Midsummer Night's Dream. When the 'rude mechanicals' convened for rehearsal, they arrived in a contractor's pick-up truck. It’s highly satisfying to see how easily these classic works of an Elizabethan theater accommodate modern styles and trickery. The new "Education Program" production at the Mount employed every vaudevillean schtick in the book, sight gags, foolish tumbles and falls from unearned grace. Plugged-in Feste rises above the fray with his sad-happy "so it goes” commentaries in verse-song on the way of the world. He’s not talking about the weather when he sings “Heigh-ho, the wind and the rain… And the rain it raineth every day.” Or the across-the-classes wisdom-warning come-on of “Come and kiss me sweet and twenty Youth’s a stuff will not endure…” The play's social comedy also offers us a war of the lifestyles contest between Olivia’s “be drunken always" frat boy brother Antonio and Shakespeare’s portrait of a Puritan abstainer Malvolio. Malvolio is both the deserved object of his enemies' take-down and the victim of a prank that gets out of hand and goes too far, weaving a thread of darkness into the play's comic resolution. Yet most of us take the side of the irresponsible Antonio when he responds to Malvolio's smug preachiness with the rebuttal: “Just because thou art virtuous do you think there shall be no more cakes and ale?” Almost everybody who hears that exchange is voting for cakes and ales. And I'm voting for "Twelfth Night," a play with more wit than foolishness, where most of those plot twists turn out right in the end.

Published on August 11, 2016 20:36

August 8, 2016

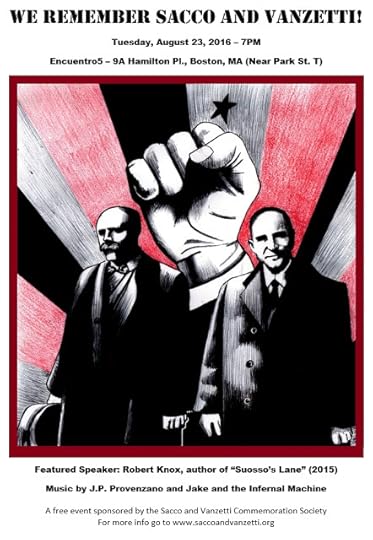

Garden of Commemoration: Every Year in Boston

Looking backward, looking forward. Both directions giving the same signals. The execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, whose real-life journeys of commitment and tragic ends are the basis for my fictional account in "Suosso's Lane," took place 89 years ago on Aug. 23. Each year The Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Society recognizes this date with an event in Boston. This year the group, which defines its goal as the preservation of "the memory of Sacco and Vanzetti's struggle to radically change society," has invited me and the musicians J.P. Provenzano and Jake and the Infernal Machine to take part at a commemorative event held every year on that date. "We want to educate our neighbors about Massachusetts' radical history, and draw connections between the struggles of Sacco and Vanzetti and similar struggles today," the Society states on its webpage. "We stand against the death penalty and political persecution as well as the persecution and scapegoating of immigrants." For some years the Society has organized marches and outdoor rallies on the date. This year it has chosen to hold an indoor event in downtown Boston, at Encuentro5, a non-governmental organization that describes itself as "a space for progressive movement building in the heart of Boston." The address is 9A Hamilton Place; a location close to the Park Street MBTA Station. The event begin at 7 p.m. The group's website is http://saccoandvanzetti.org/ Historian Robert D'Atillio will lead off the program by providing some background on the case and an introduction to the program. "We hope that you continue to support this timeless cause for justice and make plans to attend the event and bring friends to it," the Society states. A few years back a speaker at this event, Dorotea Manuela, an activist for workers' rights and Boston's immigrant communities, pointedly made the connection between the anti-immigrant background of the Sacco-Vanzetti case and the contemporary uproar and governmental crackdown against so-called "illegal" aliens. "(...) How strangely reminiscent are today's events," she said. "Arabs, Latinas, Haitians and Caribbeans are kidnapped from their streets and confined in secret prisons where they rot without hearing or trial. We do not even need the sham trials of Sacco and Vanzetti.

"In addition, our xenophobes in Congress and the press announce that yesterday's Italians are today's Latino, Haitian and Caribbean immigrants. They come here, we are told, to draw our resources, to burden our schools, to overwhelm our services and to collect welfare. Paradoxically these 'lazy immigrants' are taking all of our jobs." I wonder what Ms. Manuela would have to say about the current political climate in this year of Trumpery and the noxious 2016 election campaign in which the candidate of one of our two 'major' parties spouts ignorant bigotry in lieu of political policy or proposals. In fact, I find it hard to see how I can anything that doesn't repeat the burden of Ms. Manuela's pointed comments on the connection between the sham trial in 1921 that condemned two men who held 'dangerous' ideas about social and political change and spoke in heavy accents, the contemporary defamation of 'Mexicans' and Muslims who come from "terrorist nations." Perhaps I'll simply give up trying to say anything original and quote the elegant voices on this subject such as Ms. Manuela and New Yorker writer Kathryn Schulz, who have made these points already. Nah, just fooling. I expect I will try to say a little something about story-telling, as well as the case's continuing relevance. But I expect I will refer to the Ms. Schulz's recent piece by "Citizen Khan," which describes how one "enterprising man," an Afghani Muslim, planted an immigrant community in northern Wyoming. She concludes her story this way: "Over and over, we forget what being American means. The radical premise of our nation is that one people can be made from many, yet in each new generation we find reasons to limit who those “many” can be—to wall off access to America, literally or figuratively. That impulse usually finds its roots in claims about who we used to be, but nativist nostalgia is a fantasy. We have always been a pluralist nation, with a past far richer and stranger than we choose to recall." Hope to see you there.

http://saccoandvanzetti.org/sn_displa...

Published on August 08, 2016 21:42

August 1, 2016

Garden of the Wild: The Bear Facts

[photo from www.bearsoftheworld.net]

[photo from www.bearsoftheworld.net]Here's another oft-quoted citation from the seeming infinitude of such phrases in the works of Wm Shaxspeare. Perhaps the most singular stage direction in the history of legitimate theater: "Exit pursued by a bear."

Things do not end well for the by no means villainous character who exits (though not fast enough), so pursued. He was a court official, a bureaucrat, in the play "The Winter's Tale," who did the business that a tyrannous monarch (his royal mind self-poisoned with jealousy) bid him do. The bear was probably not aware of any of this background when he took after poor Antigonus, seeing in him merely dinner on the courtly hoof. I was not thinking of this, or any literary allusion, when I caught sight of the hefty, thick-limbed, black-furred dog-like creature a hundred feet or so down the lakeside path that Anne and I were walking, a path we have walked many times before. We were intending to keep walking it a few minutes more until we came to one of our favorite "family" spots. One sees what one expects to see, a domestic creature. Then comes the 'check-that, actually' moment that rapidly succeeds the 'big dog' false identification. The brain does a quick double-take. Uh, no, not dog -- bear. So one says, on this occasion, addressing one's spouse, "There's a bear on the path." Calmly. She replies, always a quick one, "There's a bear on the path?" Question: What is the first thing that happens when you spot a bear on the path? Answer: The first thing that happens is you stop worrying about the mosquitoes. I take a step backwards. Then another one. It is totally clear to me, though I am determined not to look,certainly not to stare, that the bear has seen us too. And at essentially the same moment I spotted him. He has just this moment heard our steps, or caught our scent. Or, picked up the vibe that some creature is looking at him, and so lifted his head in the sway of the same self-protective urge that set me to moonwalking back down the trail. Anne has turned by now, not wasting any further time on conversation, and is walking with some briskness back down the path in the direction we came from. I follow her lead, realizing I am now turning my back to the bear even though I have read in authoritative accounts that you're not supposed to run away from a bear. It just provokes them. But we're not 'running away,' I tell myself, we are simply walking away in a calm, steady manner, as if having decided independently, with no reference to any woodland creature whatsoever, that it is high time to return to the manor house and dress for dinner. Do I hear my superego calling? Then, spontaneously, to keep up the pretense of casual retreat, we both begin singing nonsense songs about a bear. "Oh, the bear went over the mountain, oh the bear went down to the lake The bear went back to the parking lot, it was a big mistake." Or words to that effect. Words that clearly, and repeatedly, include mention of a bear. As if, for some reason, we are unable to think of anything else but 'bear.' I wonder why that could be? Is there some supersititous logic in singing the word 'bear' in our nonsense lays. An unconscious belief that if we domesticate the creature in our silly song, he will remain a figure of folklore, who lives in harmless propinquity to our careless rhymes. Perhaps much like the bear who appears by chance in the midst of "Blueberries for Sal," that doughtly children's book, and departs harmlessly once some confusion over which child/cub belongs to which mother is straightened out. We tame our fears with silliness. "What's the bear doing?" Anne asks after we have walked some way and sung a silly piece back down the path. "Is he following us?" I have put this possibility out of my mind. I am not hearing any sound to indicate some creature, domestic or wild, is coming down the path behind us. My reply, therefore, is accurate if not enlightening. "I don't know. I haven't turned to look once." I'm aware of the old blues singer's advice, "Don't look back, something may be gaining on you." Not comforting, somehow. Anne turns to look back. "I don't see him. It doesn't look like the bear's following us." I have some other thoughts over the next twenty minutes or so. Are there sticks or branches at our feet on the woodlands floor thick enough and strong enough to serve as a weapon? As a rule, I know, fallen branches are rotten-soft. How about rocks? How likely is it that I'll find one the right size for throwing? How likely that a bear would be dissuaded by a thrown stone? The closer we get to the parking area where we've left our car, the more confident, if not completely relaxed, I grown that the bear is in no way interested in us. It seems unlikely that we will bump into him again by chance. We do stop once on our retreat -- I mean 'return '-- to the car -- to take a look at the large owl who has dropped onto a branch a mere half a dozen feet from our path. But that's another story.

Published on August 01, 2016 22:15