Robert Knox's Blog, page 39

July 3, 2016

The Garden of History: Celebrating Independence Day with "Letters" from Dearest Friends

John Adams thought that Independence Day should be celebrated on July 2, not the traditional date given national holiday status, July 4. July Fourth marked the date on which the delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia signed The Declaration of Independence, the document that contains the famous words about the equality of all human beings Americans are justly proud of.

But July 2 was the date the delegates from the 13 colonies voted to declare independence from Great Britain, culminating a year-long fractious, often hopeless-seeming debate between those who advocated for the bold and dangerous step of complete separation from Britain and those who held back. The momentous July 2 vote unanimously approved a resolution to declare independence. July 2 was justly celebrated Saturday at the Adams National Historical Park by a performance of a new hour-long opera, "My Dearest Friend: The Letters of John and Abigail Adams" by Patricia Leonard. The words of the libretto, as Leonard states in the program notes, come from a correspondence of over a thousand letters maintained by America's first "power couple." That dramatic story of what took place on the July 2, 1776 at the Continental Congress is told in the historical musical "1776." Seeing it on stage or in the popular screen version is how most of us come to appreciate the role John Adams played in pushing delegates from the 13 very different colonies in a direction many did not wish to go. Because of the role John Adams played in bringing about the American Revolution, his status as a founding father and the second President of the subsequently formed United States of America, we have a National Park in Quincy. (For contrast, consider that there is no National Park presence at all in Plymouth, Mass.,"America's hometown," the site of the first successful English colony in North America, and the birthplace or that peculiarly American holiday Thanksgiving.) Many of us may also be acquainted with the influence that Abigail Adams had on her husband, and through him on some crucial Revolutionary period events given her status as a new nation's first feminist spokesman who had the ear of important national leader. Abigail's plea "Remember the ladies" is commonly cited, though the reasons for it are sometimes neglected. Abigail Adams is advocating that women be entitled to fundamental human rights such as the right to own property, that were denied to them under English law. Without these basic legal rights, women were subject to the tyranny or husbands and fathers. "Remember [she writes] all men would be tyrants if they could..." As these samples from the letters suggest, the correspondence between these two brilliant, articulate, devoted marriage partners is one of the literary treasures of American history. The opera's title is based on the salutation both partners often used in letters to one another, "My Dearest Friend." Given John's involvement in national affairs in a time before rapid transportation, the couple was more often apart than together for a 10-year period in the early part of their marriage. Leonard states that the music she wrote for the letters "evokes both patriotism, and the Adams's personal family sacrifices which were necessary for shaping a new America." To me Leonard's music sounded American, elevated, and deeply affecting, honoring both the emotions the two express for one another and the high drama of the national birth crises the couple frequently address in their letters. The score reminded me of the music of Aaron Copland, though that's the case with almost anything written on a big consciously American theme, and sometimes evoked a feel for the high romantic moments of Richard Rodgers-Americana musical theater ("Carousel," say). It also put me in mind of certain sung moments in the Episcopalian liturgy, which undoubtedly says more about me than the opera. The only fault I could find is that the hour-long two-voice opera was not long enough. I would suggest adding the time and place of the writing of each of the letters to the program distributed to the audience, which very usefully provided a full libretto. In an aria sung by John titled "I Wish Myself at Braintree" -- referring to his Massachusetts home in what is now Quincy -- he complains of his absence from family life, a constant theme, and abruptly announces "I must prepare for a journey to Philadelphia." The date would help make clear that he has been chosen to represent his state at the congress to decide his country's future. Abigail replies with a short, meaningful recitative in which she broods: Has any land ever regained its liberty "when once it was invaded, without bloodshed?" The words prove a dark foreshadowing of a difficult time for the separated couple, an especially frightening period for Abigail as a huge British fleet enters Boston harbor, the British attack Charlestown, setting the town on fire, and bring on the bloody battle of Bunker Hill. From their Quincy home Abigail and the children can see the fleet, see and smell the smoke from the burning town, and are unable to escape the noise of the thunderous cannon fire of battle. "The constant roar of the cannon is so distressing [she writes John]/ that we cannot eat, drink or sleep/ you cannot imagine how we live!" Abigail's graphic depiction of the embattled homefront in letters John shared with the delegates at the Continental Congress in far-away Philadelphia causes them to face up to the fact that Britain has already declared war on American militias. When the delegates do embrace independence on July 2, John writes that the day will be celebrated by succeeding generations "as the Day of Deliverance/ with pomp and parade/ with shows and games/ bells, bonfires and illuminations/ from one end of this continent to the other/ from this time forward ever more." I don't ordinary think of myself as the kind person who gets mushily sentimental and patriotic over Independence Day (regardless of which date we choose to celebrate) but, as "My Dearest Friend" shows me, that is exactly the kind of person I am.

Published on July 03, 2016 20:50

June 28, 2016

The Garden of the Longest Days

The meteorologist explained (or, rather, stated) that the period of the longest days, begun on June 20, were now at an end. But due to an astronomical peculiarity that I will never seek to understand the latest sunsets were taking place this week.

The meteorologist explained (or, rather, stated) that the period of the longest days, begun on June 20, were now at an end. But due to an astronomical peculiarity that I will never seek to understand the latest sunsets were taking place this week. Well, wherever you get those extra minutes, morning or evening, June in New England is a lovely month in which to enjoy them, and the last couple of weeks have been among the best I can remember.

When I tried to capture this rare conjunction of long days and dry air with my camera last week, the images my camera was producing were highly at odds from the light I was seeing with the naked eye. So much darkness leaning into the frame. Where was it coming from.

When I tried to capture this rare conjunction of long days and dry air with my camera last week, the images my camera was producing were highly at odds from the light I was seeing with the naked eye. So much darkness leaning into the frame. Where was it coming from. I am told the images I was creating were produced by what is called the Toy Camera Effect. So here are some photos taken (mostly) before I figured out what was happening and how to make it stop.

From the top, the following plants are featured in these pictures. First,a deep red-violet spirea in the foreground (the red more pronounced in real light than in the photo). This variety is called Anthony Waterer; I can find no explanation for the name. It grew large as soon as we planted it; we have to pull it back off the path every year. In the background, the yellow flowers are evening primrose. They have dominated for the last week or two, having colonized patches here and there all over the garden.

From the top, the following plants are featured in these pictures. First,a deep red-violet spirea in the foreground (the red more pronounced in real light than in the photo). This variety is called Anthony Waterer; I can find no explanation for the name. It grew large as soon as we planted it; we have to pull it back off the path every year. In the background, the yellow flowers are evening primrose. They have dominated for the last week or two, having colonized patches here and there all over the garden.  Second photo down features purple-blossomed spiderwort in the foreground. Again, this is the plant's moment. It lights up in the mornings mostly, spreads itself, grows everywhere (and gets yanked up unceremoniously by Anne, who is not a fan). I think it pairs nicely with all the yellow foliage of late June. We see it hear in front of a haze of Lady's Mantle blossoms, a lacy flower with a pale color that the 'toy' effect intensifies.

Second photo down features purple-blossomed spiderwort in the foreground. Again, this is the plant's moment. It lights up in the mornings mostly, spreads itself, grows everywhere (and gets yanked up unceremoniously by Anne, who is not a fan). I think it pairs nicely with all the yellow foliage of late June. We see it hear in front of a haze of Lady's Mantle blossoms, a lacy flower with a pale color that the 'toy' effect intensifies.  Third photo down shows red blossoming Coreopsis in the foreground, a scatter of cosmos around the low, dark-metal sundial, and in the background the red spikes of Astilbe.

Third photo down shows red blossoming Coreopsis in the foreground, a scatter of cosmos around the low, dark-metal sundial, and in the background the red spikes of Astilbe.The fourth photo focuses on the big yellow blossoms of Achillea (called yarrow). You can see some of that purple spiderwort in the background, hemmed in by the emphatic shade of the toy camera effect

The fifth photo features the light pink blossoms of a Penstemon (also called beardtongue; don't ask me why). The gray mass behind them is Artemisia, which spreads aggressively and gets pulled up a lot too.

The last photo shows good old red roses. This classic vine was on the property (I won't say 'growing') when we moved here. It looked dead, but some pruning and fertilizing brought it back amazingly.

The last photo shows good old red roses. This classic vine was on the property (I won't say 'growing') when we moved here. It looked dead, but some pruning and fertilizing brought it back amazingly. We will miss this June when it passes. The garden is thirsty already. When these best days of early summer come each year, I want to drag my feet to slow the circles down.

Published on June 28, 2016 21:54

June 25, 2016

The Garden of History: What Happened to the Ashes?

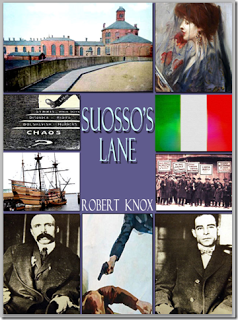

My thanks to Hingham Library for hosting us and "Suosso's Lane" last week -- as I wrote on Facebook after last Wednesday evening's program. Anne and I (as I also wrote) continue to be impressed by the number of people who to come our "Suosso's Lane" presentations because of their prior interest and knowledge of the Sacco-Vanzetti, "the case that refuses to die." And folks ask good questions, such as where were the defendants buried after the executions? I knew that Sacco and Vanzetti were cremated, but since I had forgotten the name of the cemetery, I wrote in that Facebook post, "Their bodies were cremated at the Crematorium in Boston's Forest Hills Cemetery. In both cases the ashes were returned to family in Italy." A day later I received this reply from Luigi Botta: "a part of the ashes of Sacco ended the widow; a part of both the Aldino Felicani Committee; the remainder, divided, families in Italy, in Villafalletto and in Torremaggiore." Surely a more complicated account. The statement that some of ashes of each man's remains were commingled and given to "the Aldino Felicani Committee" reminded me of something that I had read -- namely, that the ashes had given to the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee. That is surely what Mr. Botta is referring to, since Aldino Felicani was the head of that committee. But I also remembered learning recently that Felicani's Sacco-Vanzetti archive, consisting of records of the defense committee, letters, and other materials were donated by him to the Boston Public Library. I looked up what the library had to say about what it calls "The Aldino Felicani Sacco-Vanzetti Collection, 1915-1977." According to the library's three-page description of this collection, it includes the ashes of both defendants in the famous case. Aldino Felicani, a friend of both men, led the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee for the full seven years of its existence. Felicani turned down other requests for the defense committee's papers, including one from Harvard, because he wanted the collection to be stored in Boston, where he believed the case was centered. The defense committee's headquarters were located on Hanover Street, the main avenue in Boston's North End, a heavily Italian neighborhood at that time. ("Suosso's Lane" -- pardon the obligatory plug -- depicts a tense scene in the defense headquarters during the last weeks before the execution when the committee's lawyers sought desperately for some legal machinery to halt or delay the executions.) I have been told by people better able than I to know that the library's Aldino Felicani Sacco-Vanzetti Collection is the most valuable scholarly archive of information about the case. It seemed likely to me that the ashes had been divided; some portion went to the defendants' families and some to the committee. I decided to look for a neutral source. I found what appears to me a standard account of what took place in Boston after the two men were executed by electrocution at the Charlestown State Prison, including crowd estimates (made at the time by sources such as the Boston Globe) of the Sacco and Vanzetti funeral, often described as the largest ever public gathering in the city of Boston until the celebration for the Boston Red Sox World Series championship in 2004. The funeral was held at the Langone Funeral Home on Hanover Street in Boston, where "more than 10,000 mourners viewed Sacco and Vanzetti in open caskets over two days." (From Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacco_a...) On Sunday, Aug. 28, "a two-hour funeral procession bearing huge floral tributes moved through the city. Thousands of marchers took part in the procession, and over 200,000 came out to watch." Police would not allow the march to take its intended route past the State House and "at one point mourners and the police clashed." The Boston Globe termed these events "one of the most tremendous funerals of modern times." The funeral march was an eight mile hike to the cemetery, during which the marchers -- according to Francis Russell's "Tragedy at Dedham" -- were attacked more than once by "Red-hating" residents of the neighborhoods they marched through. This fact does not appear in the Wikipedia account. After "a brief eulogy," the bodies were cremated in Forest Hills Crematorium, one of the first such facilities in the city. The Wik account concludes: "Sacco's ashes were sent to Torremaggiore, the town of his birth, where they are interred at the base of a monument erected in 1998. Vanzetti's ashes were buried with his mother in Villafalletto." I'm thinking that all of these accounts are true: Some of Sacco's ashes were given to his wife, Rosina; some sent to his family in Italy. Some of Vanzetti's ashes were sent to his family in Villafalletto in the north of Italy. Some of each man's were commingled and given to the committee; this portion now presumably resides in the Boston Public Library. I am grateful to Mr. Botta for his comment and the information, though I fear I may not able to tell him so. In a clear case of "Facebook goes international," Mr. Botta works in Italian, at least all the information Google provides on him is in that language. And while his English, while not idiomatic, is better than my Italian, which is non-existent, we may not have enough words in common between us to go any further. Yet, as has been observed already, Sacco and Vanzetti is "the case that refuses to die."

My thanks to Hingham Library for hosting us and "Suosso's Lane" last week -- as I wrote on Facebook after last Wednesday evening's program. Anne and I (as I also wrote) continue to be impressed by the number of people who to come our "Suosso's Lane" presentations because of their prior interest and knowledge of the Sacco-Vanzetti, "the case that refuses to die." And folks ask good questions, such as where were the defendants buried after the executions? I knew that Sacco and Vanzetti were cremated, but since I had forgotten the name of the cemetery, I wrote in that Facebook post, "Their bodies were cremated at the Crematorium in Boston's Forest Hills Cemetery. In both cases the ashes were returned to family in Italy." A day later I received this reply from Luigi Botta: "a part of the ashes of Sacco ended the widow; a part of both the Aldino Felicani Committee; the remainder, divided, families in Italy, in Villafalletto and in Torremaggiore." Surely a more complicated account. The statement that some of ashes of each man's remains were commingled and given to "the Aldino Felicani Committee" reminded me of something that I had read -- namely, that the ashes had given to the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee. That is surely what Mr. Botta is referring to, since Aldino Felicani was the head of that committee. But I also remembered learning recently that Felicani's Sacco-Vanzetti archive, consisting of records of the defense committee, letters, and other materials were donated by him to the Boston Public Library. I looked up what the library had to say about what it calls "The Aldino Felicani Sacco-Vanzetti Collection, 1915-1977." According to the library's three-page description of this collection, it includes the ashes of both defendants in the famous case. Aldino Felicani, a friend of both men, led the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee for the full seven years of its existence. Felicani turned down other requests for the defense committee's papers, including one from Harvard, because he wanted the collection to be stored in Boston, where he believed the case was centered. The defense committee's headquarters were located on Hanover Street, the main avenue in Boston's North End, a heavily Italian neighborhood at that time. ("Suosso's Lane" -- pardon the obligatory plug -- depicts a tense scene in the defense headquarters during the last weeks before the execution when the committee's lawyers sought desperately for some legal machinery to halt or delay the executions.) I have been told by people better able than I to know that the library's Aldino Felicani Sacco-Vanzetti Collection is the most valuable scholarly archive of information about the case. It seemed likely to me that the ashes had been divided; some portion went to the defendants' families and some to the committee. I decided to look for a neutral source. I found what appears to me a standard account of what took place in Boston after the two men were executed by electrocution at the Charlestown State Prison, including crowd estimates (made at the time by sources such as the Boston Globe) of the Sacco and Vanzetti funeral, often described as the largest ever public gathering in the city of Boston until the celebration for the Boston Red Sox World Series championship in 2004. The funeral was held at the Langone Funeral Home on Hanover Street in Boston, where "more than 10,000 mourners viewed Sacco and Vanzetti in open caskets over two days." (From Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacco_a...) On Sunday, Aug. 28, "a two-hour funeral procession bearing huge floral tributes moved through the city. Thousands of marchers took part in the procession, and over 200,000 came out to watch." Police would not allow the march to take its intended route past the State House and "at one point mourners and the police clashed." The Boston Globe termed these events "one of the most tremendous funerals of modern times." The funeral march was an eight mile hike to the cemetery, during which the marchers -- according to Francis Russell's "Tragedy at Dedham" -- were attacked more than once by "Red-hating" residents of the neighborhoods they marched through. This fact does not appear in the Wikipedia account. After "a brief eulogy," the bodies were cremated in Forest Hills Crematorium, one of the first such facilities in the city. The Wik account concludes: "Sacco's ashes were sent to Torremaggiore, the town of his birth, where they are interred at the base of a monument erected in 1998. Vanzetti's ashes were buried with his mother in Villafalletto." I'm thinking that all of these accounts are true: Some of Sacco's ashes were given to his wife, Rosina; some sent to his family in Italy. Some of Vanzetti's ashes were sent to his family in Villafalletto in the north of Italy. Some of each man's were commingled and given to the committee; this portion now presumably resides in the Boston Public Library. I am grateful to Mr. Botta for his comment and the information, though I fear I may not able to tell him so. In a clear case of "Facebook goes international," Mr. Botta works in Italian, at least all the information Google provides on him is in that language. And while his English, while not idiomatic, is better than my Italian, which is non-existent, we may not have enough words in common between us to go any further. Yet, as has been observed already, Sacco and Vanzetti is "the case that refuses to die."

Published on June 25, 2016 17:39

June 21, 2016

Garden of Verse: Poems of Memory and Places, Recollections and Losses

So many beautiful poems, arresting lines and images in the June 2016 edition of Verse-Virtual. Among the poems that got to me Joyce Brown's "Cultivation," calls to me by the title alone because garden poems are so ripe with metaphorical potential. And, as in this poem, personification is a natural gesture. "The poor beets didn’t have a chance," Brown begins. "Neither did my gentle bean and pepper plants." I know just how she feels. Some plants kept trespassing on the space that 'belong' to others. "I’m at a loss with vegetable aggression," the poet writes. (So am I.) We can't deal with it, but we know nature will. Nature also takes its course, and we know how things will end: "Winter will kill the garden anyway..." Winter -- yet another natural subject for more poems. With its own box of metaphors.

A poem about a place, Thomas Erickson's "St. Augustine" picks out the sticking-point details to make a convincing whole of the parts.

"Everything is the oldest here—

the oldest house, the oldest mission,

the oldest park where they walk past

the bromeliads and seashell geegaws

for sale on the site of the oldest slave market

in North America." I've been to this earliest of settlements, so florid and diverse (and such a contrast to the wintry-survivalist religious Pilgrim narrative of the Northeast). The place teems with old history and new green growth, and something in between like those "bromeliads," plants that grow on other plants with no direct contact with soil. The word itself sounds like a metaphor for human culture. And "St. Augustine" the poem puts us in the place, with its stark history and beautiful setting.

Two moving poems from Alan Walowitz, one with a title that says so much, "The Anatomy of Longing." A similarly thought-provoking, mystically creepy is line attributed to a doctor, "Medicine has no name for this," which by itself could be the father of many poems. "No Use," a poem about preserving memories when memory fails, takes us by specific routes to difficult places, like the poet's attempt to stimulate an older relative's memories of a shared past by studying a map: "on a map we try to navigate

the bus routes through Queens

and the neighborhoods we’d pass

on our way to the city..." Everything in the shared, recollected world is meaningful, the poem suggests, but not so much when you can't remember it.

Dick Allen's poem "Two Cranes" connects sightings of two great, splashy, picturesque birds, outsize celebrity visitors -- dwarfing New England's smaller-scaled avian population -- to the American writers Hart Crane and Stephen Crane. "Hart Crane was most surely

a Great Egret Heron, given to low croaking calls and sudden flights

across Thrushwood Lake at dawn or dusk, although

like Stephen, mateless." The poem ends with a beautiful line (I won't spoil it here) connecting these spectacular water birds to the writers' more dangerous love of the watery element. Robert Wexelblatt's "Self-denial" is a marvelous poem that puts me in a chilly mood right at the start: "His thermostat is set at 58." Thought is dressed in telling garments here, like the subject of this poetic meditation. I love this image: "In the void of his closet, one blue suit,

a relic of prehistoric weddings,

hangs like a traitor executed long

ago." We've all probably encountered a figure like this somewhere, so zen and giving-up-everything that he doesn't quite exist any more. Maybe we are our foibles. "Two Children on the Seaside Rocks" by Penny Harter is a poem about a painting that preserves a time and its truth, somehow both momentary and lasting. The particulars of images, unique living moments, the poem tells us, live in our memories and imaginations:"The rocks striated brown shot through with moss,

the weathered boathouse and dock at low tide,

the hazy garments blowing on the clothes line

strung between two trees behind the outhouse—..." The poem does to the painting what the act of creating works of visual art does to its subject.. as the poem itself shows us in this marvelous image:"catching time in a sieve, netting the light..."

Maybe some poems do this too. See http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

Published on June 21, 2016 09:40

June 20, 2016

First Day of Summer: Fiddling Around the Edges

Having absented myself for two weeks of the rapid-growth period in late May and early June, it's now clear that I will never catch up this summer to what the forces of nature and the Darwinian energies of green plant life have offered up this year. I'm just trimming around the edges.

Having absented myself for two weeks of the rapid-growth period in late May and early June, it's now clear that I will never catch up this summer to what the forces of nature and the Darwinian energies of green plant life have offered up this year. I'm just trimming around the edges.  I can't remember a year when the perennials -- and the weeds (perennial, all right, in their own way) -- have covered every inch of ground devoted to planting space so quickly and then started in on the so-called paths, the dedicated people space that in theory allows us to walk around and look at what's growing. And even the pavement, where a semi-centimeter of space between stones or bricks has become living room for opportunistic seeds and roots.

I can't remember a year when the perennials -- and the weeds (perennial, all right, in their own way) -- have covered every inch of ground devoted to planting space so quickly and then started in on the so-called paths, the dedicated people space that in theory allows us to walk around and look at what's growing. And even the pavement, where a semi-centimeter of space between stones or bricks has become living room for opportunistic seeds and roots.

Maybe it's the bounce-back effect of a mild year following a cold year. The winter of two years back (2014-15) stayed cold so long that green growth started a full month later than usual. Last winter was considerably milder. Spring started sooner and every plant that grows in Quincy threw itself into a mad race to get there first. Weeds worked hard to stay a step ahead of the tall-growing perennials. Between the two of them, I'm worried about the little guys. The low-growing ground-covers and small-leafed spring bloomers that add variety to the plant mix and deserve a place in the sun. The Mazus, chased away by the long snow last year, faced a tough fight trying to regain some lost ground this year. Thyme plants and other Steppables that I planted a decade ago are facing a crunch. They're like the local saving and loan, the mom and pop grocery, trying to keep going when the big banks and national chains come to town.

Maybe it's the bounce-back effect of a mild year following a cold year. The winter of two years back (2014-15) stayed cold so long that green growth started a full month later than usual. Last winter was considerably milder. Spring started sooner and every plant that grows in Quincy threw itself into a mad race to get there first. Weeds worked hard to stay a step ahead of the tall-growing perennials. Between the two of them, I'm worried about the little guys. The low-growing ground-covers and small-leafed spring bloomers that add variety to the plant mix and deserve a place in the sun. The Mazus, chased away by the long snow last year, faced a tough fight trying to regain some lost ground this year. Thyme plants and other Steppables that I planted a decade ago are facing a crunch. They're like the local saving and loan, the mom and pop grocery, trying to keep going when the big banks and national chains come to town.

More striking still than the tyranny of the large over the small are the encroachments of ever-expanding plant colonies on the paths I labored to secure a few years back, when I still some big flat rocks to work with, plus the pieces of mal-adapted roof slates we stole from a dumpster around the same time.

More striking still than the tyranny of the large over the small are the encroachments of ever-expanding plant colonies on the paths I labored to secure a few years back, when I still some big flat rocks to work with, plus the pieces of mal-adapted roof slates we stole from a dumpster around the same time.

Prominent among the expanders is a tall grassy plant sold perhaps as an 'ornamental grass,' when 'rapacious conqueror' might be a better name. (It's sold as northern sea oats.) I introduced it into some spots a few years ago under the impression that I needed something with roots to hold down some bare ground, hard to even imagine the need for this now. The plant takes everything you give it, and then it takes what you gave its neighbors. It's closing over a path now that I once topped with gravel. I used gravel a sort of decorative topping, icing on a footpath. But if you don't put your stone down thick as a brick, plants such as this one will summon dirt (don't ask me how) to cover your gravel, turn it into mush, and sink their roots into the resulting slurry.

Prominent among the expanders is a tall grassy plant sold perhaps as an 'ornamental grass,' when 'rapacious conqueror' might be a better name. (It's sold as northern sea oats.) I introduced it into some spots a few years ago under the impression that I needed something with roots to hold down some bare ground, hard to even imagine the need for this now. The plant takes everything you give it, and then it takes what you gave its neighbors. It's closing over a path now that I once topped with gravel. I used gravel a sort of decorative topping, icing on a footpath. But if you don't put your stone down thick as a brick, plants such as this one will summon dirt (don't ask me how) to cover your gravel, turn it into mush, and sink their roots into the resulting slurry.

Then we come to the tall rapacious "loosestrife" -- that I believe to be Lysimachia vulgaris, though 'strife' sounds right and I have let it loose -- that is consuming the middle of the perennial garden. It took a hunk of footpath there last year. If I don't make it stop this year, there may soon be an ocean of long-stemmed reddish-purplish wilders choking our brave green continent from sea to sea.

Then we come to the tall rapacious "loosestrife" -- that I believe to be Lysimachia vulgaris, though 'strife' sounds right and I have let it loose -- that is consuming the middle of the perennial garden. It took a hunk of footpath there last year. If I don't make it stop this year, there may soon be an ocean of long-stemmed reddish-purplish wilders choking our brave green continent from sea to sea.

While this may sound like ungrateful complaining, the aesthetic wildman inside me enjoys contemplating the overgrowth, the abundance, the brilliant symphonic mess of many plants seeking a place in the sun, merging their shapes, colors and flowers into a great dance of the plant kingdom as if evolution itself threw the seeds of generations upon the ground and said, 'OK, guys, go at it." And actually, maybe that's what happened. In the photos posted here we have, from top down:

While this may sound like ungrateful complaining, the aesthetic wildman inside me enjoys contemplating the overgrowth, the abundance, the brilliant symphonic mess of many plants seeking a place in the sun, merging their shapes, colors and flowers into a great dance of the plant kingdom as if evolution itself threw the seeds of generations upon the ground and said, 'OK, guys, go at it." And actually, maybe that's what happened. In the photos posted here we have, from top down: garden geranium in the foreground;

a blue medium height phlox in foreground, low campanula in the background;

blue ansonia;

baptisia;

pink coral bell flowers in the foreground, campanula in the background;

pink lamium (dead nettles) in the foreground, goat's beard in the background;

stalks of purple sage in the background, a light yellow lady's mantle flowering below;

and the yellow flowers of achillea (or yarrow) rising above the vinca and pachysandra.

... anyway here are some photos.

Published on June 20, 2016 21:38

June 19, 2016

The Garden of History: Memorial Plaque Needs a Place in the Sun

At two public programs on "Susso's Lane" last week participants at the Crane Library in Quincy and the Center for Active Living in Plymouth shared their reasons for having an enduring interest in the case of Sacco and Vanzetti, Italian immigrants executed in 1927 largely because of their radical political beliefs. One man in Quincy told me he had read all the books he could find on the subject and still remained open to be convinced one way or another on the issue of their guilt.

At two public programs on "Susso's Lane" last week participants at the Crane Library in Quincy and the Center for Active Living in Plymouth shared their reasons for having an enduring interest in the case of Sacco and Vanzetti, Italian immigrants executed in 1927 largely because of their radical political beliefs. One man in Quincy told me he had read all the books he could find on the subject and still remained open to be convinced one way or another on the issue of their guilt. In Plymouth a woman told me the story that came down to her from her mother. Her mother told her a relative (an aunt, I believe) who lived in the North Plymouth had fish delivered to her home by Vanzetti on the day of the crime for which he was accused. Vanzetti was making a living selling fish from a pushcart in 1920. Her relative wanted to testify to this face in court, but she spoke only Italian, and Sacco and Vanzetti's defense attorneys told her her testimony would be without value if she could not give it in English.

No courtroom interpreters in those days. Not much concern for the presumption of innocence either when the defendants are made to sit inside a metal cage in the courtroom.

Another person at the Quincy talk told me that the lower level of the Dedham, Mass. courthouse (where the trial was held) houses a photo of Sacco and Vanzetti sitting inside the cage in the courtroom — along with a third person. Who was the third person? he asked me.

I didn’t know. I’ll try to find out. There’s always something new to learn when it comes to the Sacco-Vanzetti case. Several historians have called it “the case that will never die.”

Historian Robert D'Attilio attended the Quincy library and spoke during the question period on the proposal made by a group he is part of -- The Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Society -- to install a memorial Sacco-Vanzetti plaque plaque (created almost 90 years ago by a famous sculptor) in a fitting public place.

D'Attilio left us with a handout titled "Working Paper for the Installation of the Borglum Sacco Vanzetti Plaque in the North End in Boston."

Here are some facts from this paper. The two men were executed in Boston in the electric chair at Charlestown State Prison on Aug. 23, 1927. Their funeral took place on a Sunday, Aug. 28, from Langone's Funeral Home in the North End, a largely Italian neighborhood. "According to newspaper accounts," the paper states, "it attracted more than 200,000 people, the largest public gathering in Boston in the 20th century." Many mourners marched the 8.5 miles to the Forest Hills Cemetery, where the two were cremated.

The executions did not put the case to rest. Books, articles, essays, poems, dramas, films, and other works centering on the case were produced in the years afterward, and some keep coming. Novels, even (can you imagine that?). The entire legal transcript, six volumes, were published and remain available. The working paper states, "The Sacco Vanzetti case became indelibly known as the 'Case That Will Not Die.'"

A volume of the letters that Sacco and Vanzetti wrote from prison were also published a year after their death. These letters moved readers all over the world, and that volume is still in print in a Penguin Books edition.

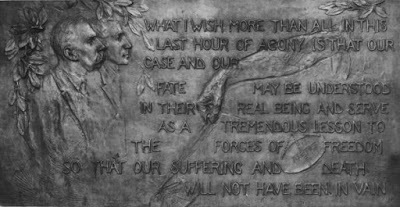

Words from Vanzetti's last letter were included on a memorial plaque. The defense committee and Felix Frankfurter, who had written widely on the case and would become a Supreme Court justice, approached famous memorial sculptor Gutzon Borglum, the man responsible for the Mount Rushmore presidential memorial, with the idea of a memorial plaque.

Borglum incorporated these words from Vanzetti's last letter (written to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana) into his design: "What I wish more than all in this last hour of agony is that our case and our fate may be understood in their real being and serve as a tremendous lesson to the forces of freedom so that our suffering and death will not have been in vain."

He created a plaster model in 1928; the bronze plaque was cast a year later. Borglum's plaque was offered to the state governor and the Boston mayor repeatedly over the years and refused by the authorities, with an umbrage that implied that Sacco and Vanzetti were common criminals and murderers. After the bronze plaque was rejected in 1957 it disappeared, and was probably destroyed. The plaster cast was displayed in the Community Church in Copley Square in 1971 and then donated to the Boston Public Library as part of a scholarly collection relating to the case, where it has been kept on the library's 3rd floor, a poor placement for a piece of public art.

In 1977, the 50th anniversary of the execution, Gov. Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation stating that the two men had been unfairly tried and that no stigma should be attached to their names. An attempt was made to rebuke the governor in the state Senate, testifying to the enduring unwillingness by many in state government to accept that the trial was flawed and unfair.

On the 70th anniversary, in 1997, Mayor Thomas Menino and acting Gov. Paul Cellucci "formally" accepted the plaster plaque at the library for the city and state. But the plaque remains to this day upstairs in the library.

The Sacco-Vanzetti Commemorative Society, formed in 2006, seeks to connect the case "under its real aspect and being" -- to quote from Vanzetti's last letter -- and "to draw connections between the struggles of Sacco and Vanzetti and similar struggles today. "

Because of the importance of the Sacco-Vanzetti case to the Boston Italian-American community, the committee believes that the best site for permanent public display of the memorial plaque at the head of Hanover Street on the Greenway "at the precise spot where the funeral of Sacco and Vanzetti passed."

The group seeks the support of the community, according to the working paper, to respond to "Vanzetti's final words: 'I wish and hope you will lend your faculties in inserting our tragedy in the history under its real aspect and being.'"

Published on June 19, 2016 19:46

June 18, 2016

The Garden of Verse: Poems that Keep Getting Deeper

Poems by Tom Montag in the June issue Verse-Virtual, the online poetry journal I've been part of for a year and a half now, remind me that some poet's work just gets deeper and deeper.

Poems by Tom Montag in the June issue Verse-Virtual, the online poetry journal I've been part of for a year and a half now, remind me that some poet's work just gets deeper and deeper. A Wisconsin native who refers to himself as a farm boy in his essays, Tom Montag regularly publishes poems in Verse-Virtual celebrating the essential mysteries of the world we live in. What do we have, all of us, in common? We have day, night. We have sunlight, sky. Darkness, night, the stars. We have as companions, as sharers of this world, this planet -- as has become increasingly clear to me in recent years; I have a window open right now to keep an ear attuned to them -- the birds. Winter is the season in which we see birds at our feeder but do not often hear their voices. Spring is the season when their excited voices wake us a dawn. If you're like me, you go back to sleep. If you're like Tom Montag, you're up at your desk when the birds begin. What else? If we have pets, generally dogs or cats, we know we share the world with mammals. Since the death of our last cat, I confess the most prominent fellow mammal in my life is the urban/suburban squirrel, not the most neighborly of connections. People who have lived on farms have a far wider knowledge of animals who do not walk on two legs. I know we share the earth with the beasts of the field, but I walk warily past the klatches of cows I encounter on the public right of way in the north of England, or cutting across some farmer's field in rural Massachusetts, pretending we are all friends. We all share the vast kingdom of the green plants, the life forms that ultimately feed us and give us. I tell myself that my flowers are now my pets, and I collect them greedily. And we all, if we are truly alive, share love. Mortality, of course; that goes without saying. But the love, that sometimes needs saying. For all these reasons, Tom Montag's poems have long spoken to me as poems about the essence of our condition, as human beings here on earth. And the more of them I am exposed to, the more likely they are to snag on something inside of me and stay there. In the June issue of Verse-Virtual, I found Tom's poems sinking deeper and deeper. The title and first sentence alone of his poem, "Only the Few" -- "Only the few mysteries/ I am drawn to." -- has basically prompted my reflections above. What I am calling a sentence is actually a sentence fragment. It invites the reader to ask yourself 'What about the mysteries the poet is drawn to? Am I drawn to them too?' Is the poet saying those are the only topics to write poems about? Or the only sources of his inspiration? The poem appears to name those mysteries, but it's the pacing of the lines, the phrases, that enables us to discover that they're our mysteries too: "the way the darkness carves out/ the evening ..." When I get to the lines "Somewhere silence. Somewhere/ the call of the red-tail..." I am totally drawn in. Yes. Yes, I think, "the house closing in," that's exactly it. And then a perfect last line reaching for the stars. Read the whole poem, and his others, on Verse-Virtual at http://www.verse-virtual.com/tom-mont.... I feel something very similar about the poem "A Bird," that begins "out a corner of the eye,

lost, then, in leaves and sky." It happens all the time, maybe every day, and is still as the poem says, a miracle. Who are these creatures flying around, with hearts that beat like our own? The poem gives us precisely the right words for this experience: "A loveliness we can't speak/ and we walk on." The reader knows the ineffable instant the poet is referring to, but now we've been given words for it. And again, in the poem "The Dead Leave Us." That's a phrase that can end right there; or it can go somewhere. When the poet writes "The dead leave us/ their shadows" we think, 'Yes, that's it. That's what we feel.' We've had that sensation. But now, here are the words. These poems do what poems, perhaps alone of all human utterance or actions can do: stamp meanings precisely on our hearts. Find Tom Montag's poems and other wonderful poems on Verse-Virtual.com

Published on June 18, 2016 10:29

June 14, 2016

The Garden of History: The Biggest, Saddest Gathering in Boston

Historian Robert Robert D'Attilio tells this story. In the era of newsreels shown before the features in movie theaters everywhere, and a couple years before the first "talkie," newsreel footage was taken of the Boston funeral of Sacco and Vanzetti.

Historian Robert Robert D'Attilio tells this story. In the era of newsreels shown before the features in movie theaters everywhere, and a couple years before the first "talkie," newsreel footage was taken of the Boston funeral of Sacco and Vanzetti.But what happened to that footage?

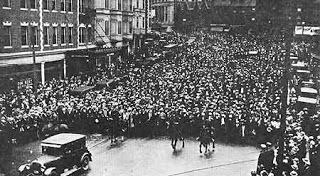

After their execution at Charlestown State Prison on Aug. 23, 1927, a funeral for Sacco and Vanzetti was held at Langone's Funeral Home on Hanover Street in Boston's North End. With the bodies on view, an estimated 100,000 people passed by the bodies. The funeral march to the Forest Hills Crematory was judged the largest public gathering the city had ever seen. Many black and white photographs show the extent of the funeral gathering (such as those above).

On Sunday, Aug 28, 1927, according to a Wikipedia posting

(http://dictionary.sensagent.com/Sacco...)

"a two-hour funeral procession bearing huge floral tributes moved through the city. Police blocked the route, which passed the State House, and at one point mourners and the police clashed." After a brief eulogy at the Forest Hills Cemetery, the bodies were cremated. "The Boston Globe called it "one of the most tremendous funerals of modern times."

Lots of newsreel footage was taken as well, but almost none of it exists today. The reason is an interesting example of government censorship. Though no official records exists of this action, the US government, probably through the FBI, passed the word to Hollywood to destroy all footage of the funeral. The government did not want the American people to see the long lines of mourners following the funeral cortege for Sacco and Vanzetti. They did not want the story kept alive. Speaking at a program for "Suosso's Lane," my novel based on the famous case, at Thomas Crane Library in Quincy Tuesday evening, D'Attilio called the newsreel's suppression "the first film burning in history." "All Hollywood newsreels on Sacco and Vanzetti are ordered destroyed by Will Hayes, movie czar," D'Attilio writes in his chronology of the Sacco-Vanzetti case. Hayes, who gave his name to the infamous Hollywood censorship code, became President of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America in 1922. But a few minutes of film survived somewhere, and surfaced decades later. The Sacco-Vanzetti Commemorative Society plans to screen it in the near future somewhere.

D'Attilio also spoke of the society's campaign to place the memorial plaque in a public setting. The favored place would be in North Square in Boston's North End, near the site of the funeral and the funeral march. D'Attilio also said that a historical plate has already been placed by the city at 256 Hanover St., marking the address of the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee office. The Quincy library program drew an attentive crowd. From the quality of the comments and questions, a number of people knew and cared about the case.

To answer a question that came up at a previous "Suosso's Lane" program, that I was unable to answer at the time, Sacco's ashes are located in Torremaggiore, Italy, the town of his birth, at the base of a monument erected in 1998. Vanzetti's ashes were buried with his mother in his home town of Villafalletto.

Published on June 14, 2016 22:20

June 12, 2016

The Garden of Earthly Beauty: Two Islands in Greece

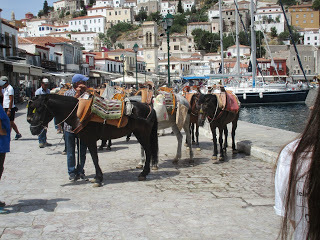

If your luggage is too heavy to carry up to your room -- or pension, or house -- on the island of Hedra, the gem of the Saronic Gulf, you hire a donkey. You will not be able to take a taxi or even a motorcycle (or a tourist bus or even a minivan) because "all wheeled vehicles" are banned from Hedra. The resulting island ambience is a unique blend of beauty and pre-industrial silence.

If your luggage is too heavy to carry up to your room -- or pension, or house -- on the island of Hedra, the gem of the Saronic Gulf, you hire a donkey. You will not be able to take a taxi or even a motorcycle (or a tourist bus or even a minivan) because "all wheeled vehicles" are banned from Hedra. The resulting island ambience is a unique blend of beauty and pre-industrial silence.

Many places in Greece are beautiful. Many are also peaceful. Set in the sunny blue water of the Aegean off of the ancient region known as the Peloponnese, Hedra is beautiful, peaceful and also quiet. It's a rare place, with enough international draw that people like Leonard Cohen keep a house there.

Many places in Greece are beautiful. Many are also peaceful. Set in the sunny blue water of the Aegean off of the ancient region known as the Peloponnese, Hedra is beautiful, peaceful and also quiet. It's a rare place, with enough international draw that people like Leonard Cohen keep a house there.

To get there we took the ferry from the port of Tolo, a two and a half hour cruise through the Saronic Gulf with islands and mainland hillsides in view the whole way, passing the isle of Spetses (where we would also visit on the return trip). The cruise ship was comfortable and roomy, the sun-worshipers sat on the top deck. We sat on the main deck and tried to take pictures of the dolphins who lept and dove behind the ship on two occasions. Mostly I simply got the splash, though one effort (as you see in the second photo down) captured a bit of tail.

To get there we took the ferry from the port of Tolo, a two and a half hour cruise through the Saronic Gulf with islands and mainland hillsides in view the whole way, passing the isle of Spetses (where we would also visit on the return trip). The cruise ship was comfortable and roomy, the sun-worshipers sat on the top deck. We sat on the main deck and tried to take pictures of the dolphins who lept and dove behind the ship on two occasions. Mostly I simply got the splash, though one effort (as you see in the second photo down) captured a bit of tail.

The island features a photogenic port, white-walled houses with orange tiled roofs, rows of yachts and fishing boats, a steep geographic profile rising straight up from the shore, storefronts and houses built so close to the shoreline you have to assume there's hardly ever the fear of marine encroachment those of us who live by the Atlantic learn to call "storm surge." Despite the close-at-hand presence of all this ocean, the air is dry, the sunlight crystalline but soft, the insect life pleasingly absent, and the flowers bright and long-lasting. In this part of Greece, you always eat outdoors. Ship-building (according to the travel guides) in the 18th century led to the island's growth and development. Hedra was one the Greek Islands that played a significant role in the Greek independence struggle in the early 19th century, as did Spetses. Admiral Andreas Miaoulis commanded a Greek fleet when the island contributed 130 ships to a blockade effort during the war of independence from the Ottoman Empire, 1821-1829. The island of Spetses, while also very beautiful, is not so quiet. As if taking advantage of a pent-up demand for internal combustion engines caused by Hedra's proscription of motorized vehicles, the chief 'tourist" activity here appears to be riding motor cycles along the broad shoreline road and threading them through the narrow twisting lanes, where the four of us traipsed both to escape from their noise and to admire the very white-walled villas with their walled-in gardens of fruitfiul trees and flowering trees, one of these packed with an almond, olive and orange tree all finding enough sunshine to go around. The great historical figure in Spetses is the 19th century sailor Laskarina Bouboulina, to whom both a museum and a substantial statue are dedicated. Her biography (recounted in online sources) was truly that of a swashbuckling heroine. She was born in a prison in Constantinople of a captive revolutionary father, built a fortune in maritime trade, raised a Greek flag she designed herself (on a ship she named, with a sure sense of nation pride, the Agamemnon), and joined forces with fleets from other islands in the revolt against the Turks. Here's a link to the full wikipedia account:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laskari... Sailing to the Greek isles, these two at least, was a long but satisfying day. Odysseus, we know, had a full ten years of this stuff, with adventures for which the term "epic" was invented. We were happy to get back to our tourist apartment with time for a little nap before a superb dinner (prepared by somebody else).

The island features a photogenic port, white-walled houses with orange tiled roofs, rows of yachts and fishing boats, a steep geographic profile rising straight up from the shore, storefronts and houses built so close to the shoreline you have to assume there's hardly ever the fear of marine encroachment those of us who live by the Atlantic learn to call "storm surge." Despite the close-at-hand presence of all this ocean, the air is dry, the sunlight crystalline but soft, the insect life pleasingly absent, and the flowers bright and long-lasting. In this part of Greece, you always eat outdoors. Ship-building (according to the travel guides) in the 18th century led to the island's growth and development. Hedra was one the Greek Islands that played a significant role in the Greek independence struggle in the early 19th century, as did Spetses. Admiral Andreas Miaoulis commanded a Greek fleet when the island contributed 130 ships to a blockade effort during the war of independence from the Ottoman Empire, 1821-1829. The island of Spetses, while also very beautiful, is not so quiet. As if taking advantage of a pent-up demand for internal combustion engines caused by Hedra's proscription of motorized vehicles, the chief 'tourist" activity here appears to be riding motor cycles along the broad shoreline road and threading them through the narrow twisting lanes, where the four of us traipsed both to escape from their noise and to admire the very white-walled villas with their walled-in gardens of fruitfiul trees and flowering trees, one of these packed with an almond, olive and orange tree all finding enough sunshine to go around. The great historical figure in Spetses is the 19th century sailor Laskarina Bouboulina, to whom both a museum and a substantial statue are dedicated. Her biography (recounted in online sources) was truly that of a swashbuckling heroine. She was born in a prison in Constantinople of a captive revolutionary father, built a fortune in maritime trade, raised a Greek flag she designed herself (on a ship she named, with a sure sense of nation pride, the Agamemnon), and joined forces with fleets from other islands in the revolt against the Turks. Here's a link to the full wikipedia account:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laskari... Sailing to the Greek isles, these two at least, was a long but satisfying day. Odysseus, we know, had a full ten years of this stuff, with adventures for which the term "epic" was invented. We were happy to get back to our tourist apartment with time for a little nap before a superb dinner (prepared by somebody else).

Published on June 12, 2016 21:40

June 9, 2016

The Garden of History: A Hundred Years Ago in America

A century ago, 1916, Americans re-elected Woodrow Wilson, regarded as a progressive Democrat, for a second term as President. In his first term he pushed some significant legislation through Congress: a graduated income tax; the anti-monopolistic Federal Trade Commission; a law prohibiting child labor; and another law that established the 8-hour day for railroad workers.

A century ago, 1916, Americans re-elected Woodrow Wilson, regarded as a progressive Democrat, for a second term as President. In his first term he pushed some significant legislation through Congress: a graduated income tax; the anti-monopolistic Federal Trade Commission; a law prohibiting child labor; and another law that established the 8-hour day for railroad workers. This last achievement had been a goal of the American labor movement for 40 years, an aim taken up on the American example by the international labor movement. Eight hours for railroad workers created an important precedent for establishing a standard for all fulltime workers that still applies in many American workplaces. The prohibition of child labor was a goal that social reformers had urged for a century.

Wilson also followed Theodore Roosevelt's example in asserting the right and duty of American Presidents to act in the interests of the American people, even when no "strict interpretation" of the Constitution gave his office that power. But though he had pledged to keep American out of World War I, a year after election (1917) he asked Congress to declare war against Germany, following persistent attacks on American shipping.

But while Wilson's Progressive agenda would ultimately improve working conditions, American factory workers 100 years ago were finding it increasing hard to feed their families.

1916 was the year that workers at the Plymouth Cordage Company, the world's leading ropemaker, went on strike for higher pay. At the time, according to the revered Boston historian Samuel Elliot Morison, Cordage male workers earned $9 a week (women earned less). Morrison also pointed out that "the Plymouth worker of 1894 to 1900 with $8.10 a week had much better real wages" than his counterpart in 1916. Real wages for American industrial workers had been declining for 15 years, a condition made much worse after 1914 as wartime demand in Europe for American goods inflated consumer prices, while wages failed to keep up.

Bartolomeo Vanzetti, one of two defendants in the famous Sacco-Vanzetti case, and the central figure in my novel "Suosso's Lane," took part in 1916 Plymouth Cordage strike although he had stopped working for the company and worked instead as a "pick and shovel" laborer. After he had nearly died from working in a pastry factory in his teens, Vanzetti believed that outdoor work was healthier than working inside a factory.

But the North Plymouth family he lived with, and the entire North Plymouth immigrant community he was a part of for five years, depended largely on the Plymouth Cordage Company for its sustenance. A committed anarchist who believed in both the abolition of the state and the capitalist economic system, Vanzetti envisioned strikes as necessary steps toward the recognition that workers should cooperatively own and run the factories and all other enterprises that depended upon their labor. So antagonistic was he to established authority structures that he and other anarchists of his stripe also opposed the creation of labor unions, seeing them as a new layer of "official" oppression.

In an account of his life written while in jail, Vanzetti described his role in the Cordage strike:

"This company is one of the great money powers of this nation. The town of Plymouth is its feudal tenure. Of all the local men took a prominent part in the strike, I was the only one who did not yield or betray the workers... [and] I was the only one who instead of being compensated was blacklisted by the company, and subjected to a long, vain, and useless police vigilance..."

Not surprisingly Morrison, an establishment figure who wrote a book about the company in 1950 ("The Ropemakers of Plymouth"), has a different, more circumstantial view of the strike. Despite his own calculation of how poorly workers were being paid (about 16.6 cents an hour), Morrison writes that ownership had no idea that wage dissatisfaction would lead workers to take action: "Then suddenly, wihtout warning, a strike exploded in the Plymouth plant Jan. 17, 1916."

Since there was no Cordage union and would be none for decades, the strike developed, he states, when "A self-constituted committee, the membership of which was never disclosed [including] some employees and some who were not .. went to workers homes during a general strike the next day and making threats."

These are events that I dramatize in "Suosso's Lane." I'm not sure about the 'making threats' piece of the account by a historian who tended to get his information from ownership, but I tried to imagine how a group of increasingly hungry, winter-strained factory workers began to think about and then plan a general strike at a large industrial site.

Here's an excerpt from a scene in "Suosso's Lane" that leads toward the drastic decision to go on strike:

"In Italia," Benno said, his words simmering with passion, "in the North, there is a war with Austria for a mountain. A mountain of ice and snow! Two years now the mountain consumes the men. Thousands on thousands!"

"Si," said Joe, ordinarily a harried-looking man, one of the fathers whom Vanzetti suspected of joining the gathering less for the pleasure of the talk and the heat than to get away for a while from the complaints of his younger children. Now his thin features twisted. "But no matter how many die, the armies keep taking more from their homes and families. It is the armies who are buying up flour and oil and beans and macaroni."

Benno looked angrily about him. "And this means that we must pay twice as much for such needful things!”

Others raised their voices in shared outrage.

Vanzetti lifted his head. When the outrage ran its course, he pounced.

“If the food costs twice as much to buy, does it not follow that the factory must pay its workers twice as much?” he asked. He looked from face to face, holding the glance of any man who would return his own.

“Can a man or a woman eat half as much and still do the same amount of work making the rope?”

No one expected the factory to double their wages. Such a thing was unheard of. Still, it was important to reason correctly. They must see their complaint is just, he thought. It was a step. One must establish the true facts, before one bargained. Of course, he did not even believe in the bargain. Still, again, it was a step.

“Do I not speak simple truth?”

No one disagreed. Yet no one rushed in to support a calculation that might point in a direction not yet made clear.

"It is the rich men who make the war. It is the war that raises the prices. Now we must pay the cost of the rich men's war. Can this be endured?"

Enough, he told himself. You cannot drive people to a place where they do not wish to go.

"No," someone said.

He was not sure who. One of those standing by the stove, perhaps. But the single word raised the tension in the room, an air of half dread, half anticipation like the moment before the yanking off of a bandage or the pulling up of a scab. A good thing, he thought, a needed thing. Though surely painful.

"Everyone knows Vanzetti," he said. "I do not have the wife, the children. I work with the pick and the shovel. I do not work in the factory like the other men in this room. But if the workers demand what they are entitled too, I will support them every day. Someone must go to the other cities, to tell the story of this place. To raise the donations for the strike fund."

Benno returned his look. And the man Joe. Some of the others stared off. Some of these squatting against the wall in the same room looked up at him in confusion.

"I promise this will be done." The averted faces held out against hope. "By me."

"A strike?" someone said, after these words. "You urge the strike?"

I will be talking about "Suosso's Lane" and reading some excerpts from the book on Tuesday, June 14, at the Crane Library in Quincy.

Published on June 09, 2016 19:23